Abstract

Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) continues to be an important pathogen inflicting encephalitis in adults and children globally that entails high morbidity and mortality. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are the keys to minimize potential sequelae of the disease. Although HSV encephalitis-1(HSVE-1) is well recognized for its radiographic manifestation of temporal lobe involvement owing to its pathogenesis, radiographic features of HSVE-2 are less uniform. Lumbar puncture with HSV PCR testing is the gold standard for diagnosis. However, when lumbar puncture is not immediately obtainable, consideration of HSVE should be entertained in compatible clinical setting even in the absence of characteristic radiographic finding. We report a case of type 2 HSVE with atypical radiographic manifestation involving bilateral basal ganglia.

Keywords: HSV-2, Encephalitis, MRI

Introduction

Encephalitis is an inflammation of the brain parenchyma accompanied by neurologic dysfunction which can be a result of an infectious or a noninfectious etiology [1]. Infections constitute about 50 % of the identifiable cases of encephalitis [2]. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) has been identified as one of the most common culprits for viral encephalitis in adult and is accountable for about 90 % of the cases of HSVE seen in adults and children [3]. On the other hand, HSV-2 causes 80 % of the cases of HSVE seen in neonates but is an uncommon cause during post neonatal period accounting only for 10 % of HSVE cases with a predilection to affect immunocompromised patients [4,5]. HSVE -1 has been most consistently associated radiographically with temporal lobe involvement while the neuroradiologic manifestations of HSVE-2 are much less uniform [6].

Case presentation

A 49-year-old wheelchair-bound female with a history of progressive multiple sclerosis remotely treated with natalizumab with the last dose given in 2011 presented to the intensive care unit with prolonged encephalopathy and breakthrough seizures for continuous electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring. Her vital signs on presentation were notable for hypothermia, hypotension, tachycardia as well as tachypnea with hypoxia requiring mechanical ventilation. Laboratory studies revealed an elevated white blood cell count of 21,400/uL, hemoglobin of 10.0 g/dL, and platelet count of 511,000/uL. Urine toxicology screen was unrevealing.

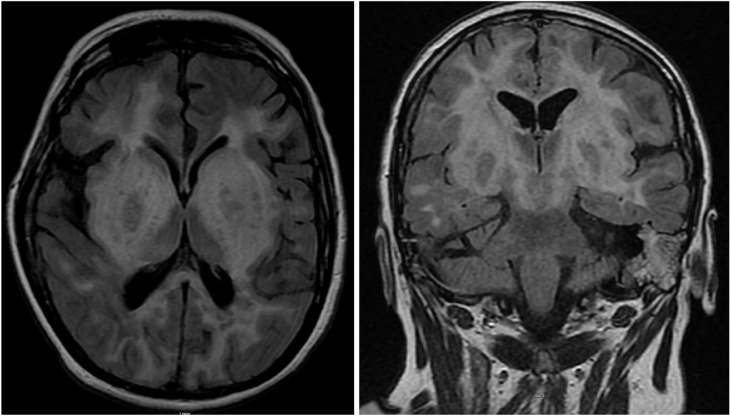

Encephalopathy was initially thought to be of a toxic metabolic cause secondary to sepsis due to pneumonia diagnosed by imaging. Thus, the patient was started on cefepime and vancomycin; continuous EEG monitoring was done but did not show any seizure activity and her antiepileptic medication dosing was adjusted. However, patient’s mental status remained unchanged and therefore, MRI brain with contrast followed by lumbar puncture (LP) was pursued. MRI showed symmetric marked edema involving the bilateral basal ganglia with mass effect on lateral ventricles (Figs. 1 and 2). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis demonstrated lymphocytic pleocytosis 95 cells/uL, low CSF glucose of 29 mg/dL and high protein of 103.1 mg/dL consistent with viral encephalitis. Due to remote history of natalizumab treatment, JC virus testing was sent in addition to other viral studies, which returned as negative. However, final viral PCR result was positive for herpes encephalitis type 2 with 19980 viral copies. The patient was started on treatment with intravenous acyclovir with subsequent improvement in mental status and was eventually discharged to a rehabilitation center.

Figs. 1 and 2.

MRI brain with contrast showing marked edema as well as enhancement in the bilateral basal ganglia, frontal, parietal, occipital lobes and brainstem.

Discussion

Both HSV-1 and HSV-2 are double-stranded DNA viruses that belong to the Herpesviridae family. Herpes simplex viruses are well recognized for their pathogenicity of causing encephalitis. The mechanism by which HSV accesses the CNS in humans remains elucidated and an area of debate. Some studies proposed that the most likely routes include retrograde transport through the olfactory or trigeminal nerves with the virus spreading to the contralateral temporal lobe via the anterior commissure [7]. This theory is deemed somewhat plausible considering the preferential involvement of the frontal as well as temporal lobe in HSVE [8].

Clinical manifestations of HSVE are variable but most commonly presentations are fever, headache, altered mental status, nausea, vomiting as well as neurological deficits including receptive aphasia, hemiparesis as well as seizures. Status epilepticus is an uncommon manifestation but a dreaded consequence. Meningeal signs are not typical of patients with HSV-1 but are more frequent in patients with HSV-2 infections. In fact, meningeal signs maybe the only presenting symptoms in patients with HSV-2E [6].

In the setting of a suspected encephalitis, a thorough history and physical exam are pertinent in prompt diagnosis. CSF examination usually reveals lymphocytic pleocytosis, increased CSF protein as well as normal CSF glucose. Positivity of HSV PCR in CSF is a gold standard for the diagnosis of HSVE but MRI findings are regarded significantly for assisting in the diagnosis [9].

HSVE-1 usually presents as areas of hyperintense signal on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences indicative of inflammatory edema in the medial temporal, inferior frontal, as well as insular regions [6,10]. One the other hand, neuroradiologic manifestations of HSV-2 infection are much less uniform with immunocompetent patients showing mild edema in a similar distribution to HSV-1 infection [6]. However, MRI changes in immunocompromised patients are inconsistent and may be more extensive, atypical or even entirely absent [11].

Natalizumab, an agent that contains humanized neutralizing IgG4κ monoclonal antibodies, is currently approved for the treatment of Multiple Sclerosis patients with more active disease that place a high value on effectiveness and are less worried about safety.

CSF studies performed comparing natalizumab treated MS patients with untreated controls demonstrated a significant decrease in lymphocyte subsets including CD4+ and CD8 + T cells, increasing the risk of opportunistic infections [12]. Few cases published in literature report HSVE-2 in patients that received natalizumab however none of them mentions a consistent or similar pattern to the one seen in our patient on imaging.

Finally, HSVE continues to confer high morbidity and mortality with overall mortality over 70 % and only 2.5 % of patients fully recovered [13]. Therefore, prompt diagnosis and initiation of treatment with intravenous acyclovir are key to reduce neurologic sequelae among survivors and reduces mortality.

Conclusion

Lumbar puncture with CSF analysis and PCR remains the gold standard for diagnosis of HSV encephalitis. Advanced imaging modality with MRI has been increasingly used to aid with diagnosis. While HSVE-1 has been associated with necrotizing encephalitis with predilection of frontal and temporal lobe involvement, radiographic features of HSVE-2 are less uniform especially in immunocompromised cohorts. In the era of increasing use of immunologic therapy, possibility of HSVE-2 with atypical radiographic manifestation should be considered and prompt empirical Acyclovir may be warranted to decrease morbidity and mortality.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and

accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Funding

Funding information is not applicable.

Authors contribution

LFY and CEM were part of the primary team taking care of the patient and contributed in writing this article. FD and RM reviewed the literature and contributed in writing the manuscript. BT is the attending physician who supervised this manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Venkatesan A., Tunkel A.R., Bloch K.C. Case definitions, diagnostic algorithms, and priorities in encephalitis: consensus statement of the international encephalitis consortium. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1114–1128. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venkatesan A. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute encephalitis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015;28:277–282. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steiner I., Benninger F. Update on herpes virus infections of the nervous system. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13:414. doi: 10.1007/s11910-013-0414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aurelius E., Johansson B., Sköldenberg B., Forsgren M. Encephalitis in immunocompetent patients due to herpes simplex virus type 1 or 2 as determined by type‐specific polymerase chain reaction and antibody assays of cerebrospinal fluid. J Med Virol. 1993;39:179–186. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890390302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennett C., Cleator G.M., Klapper P.E. HSV‐1 and HSV‐2 in herpes simplex encephalitis: a study of sixty‐four cases in the United Kingdom. J Med Virol. 1997;53:1–3. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199709)53:1<1::aid-jmv1>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh T.D., Fugate J.E., Hocker S., Wijdicks E.F., Aksamit A.J., Rabinstein A.A. Predictors of outcome in HSV encephalitis. J Neurol. 2016;263:277–289. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7960-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennische E., Eriksson C.E., Lange S., Trybala E., Bergström T. The anterior commissure is a pathway for contralateral spread of herpes simplex virus type 1 after olfactory tract infection. J Neurovirol. 2015;21:129–147. doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller S., Mateen F.J., Aksamit A.J. Herpes simplex virus 2 meningitis: a retrospective cohort study. J Neurovirol. 2013;19:166–171. doi: 10.1007/s13365-013-0158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steiner I., Schmutzhard E., Sellner J., Chaudhuri A., Kennedy P.G.E. EFNS‐ENS guidelines for the use of PCR technology for the diagnosis of infections of the nervous system. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:1278–1291. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradshaw M.J., Venkatesan A. Herpes simplex virus-1 encephalitis in adults: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Neurotherapeutics. 2016;13(3):493–508. doi: 10.1007/s13311-016-0433-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan I.L., McArthur J.C., Venkatesan A., Nath A. Atypical manifestations and poor outcome of herpes simplex encephalitis in the immunocompromised. Neurology. 2012;79:2125–2132. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182752ceb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stüve O., Marra C.M., Jerome K.R. Immune surveillance in multiple sclerosis patients treated with natalizumab. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:743–747. doi: 10.1002/ana.20858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pirasath S., Selvaratnam G., Pradeepan J. Herpes simplex encephalitis mimicking as cerebral infarction. J Clin Case Rep. 2016;6:2. [Google Scholar]