Significance

Although much current research highlights differences between political partisans, our research provides evidence that strong partisan biases in meta-perceptions are largely symmetrical for Democrats and Republicans. This suggests that biased meta-perceptions are a consequence of shared psychology rather than merely a consequence of divergent ideological convictions. Meta-perceptions represent evaluations that are distinct from perceptions at a core psychological level: While negative perceptions, such as dehumanization, can be thought of as offensive or reprehensible, meta-perceptions are inferences about what others think and can, therefore, be false. The theoretical distinctions between perceptions and meta-perceptions suggest that practical approaches to reducing negative meta-perceptions may be distinct from those that aim to reduce negative perceptions.

Keywords: political polarization, meta-perceptions, dehumanization, prejudice, ideological polarization

Abstract

People’s actions toward a competitive outgroup can be motivated not only by their perceptions of the outgroup, but also by how they think the outgroup perceives the ingroup (i.e., meta-perceptions). Here, we examine the prevalence, accuracy, and consequences of meta-perceptions among American political partisans. Using a representative sample (n = 1,056) and a longitudinal convenience sample (n = 2,707), we find that Democrats and Republicans equally dislike and dehumanize each other but think that the levels of prejudice and dehumanization held by the outgroup party are approximately twice as strong as actually reported by a representative sample of Democrats and Republicans. Overestimations of negative meta-perceptions were consistent across samples over time and between demographic subgroups but were modulated by political ideology: More strongly liberal Democrats and more strongly conservative Republicans were particularly prone to exaggerate meta-perceptions. Finally, we show that meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization are independently associated with the desire for social distance from members of the outgroup party and support for policies that harm the country and flout democratic norms to favor the ingroup political party. This research demonstrates that partisan meta-perceptions are subject to a strong negativity bias with Democrats and Republicans agreeing that the shadow of partisanship is much larger than it actually is, which fosters mutual intergroup hostility.

Disagreement is an integral component of a healthy democracy, but some forms of polarization may be toxic to democracy (1). What might lead people to support a style of governance that goes beyond advocacy of partisan social issues to threaten the fabric of society? One possibility lies in the shadow of political polarization (2). Recent polling data show that nearly 69% of Democrats and Republicans believe that Americans are greatly divided on their most important values (3), and both Democrats’ and Republicans’ levels of affective prejudice toward the other side are at a 40-y high (4, 5). However, is the shadow of partisanship as large as Americans believe it to be? Previous research suggests that it might not be (6–11). For example, research in political psychology reveals that the perceived extremity of outgroup positions on social issues is reliably exaggerated: When people are asked to report how the average partisan outgroup member stands on a social issue, both Democrats and Republicans predict that the outgroup holds views that are more extreme and, therefore, more divergent from their own than they are in reality (8–11). This false polarization bias has been demonstrated over time and across a range of social issues (9); however, it remains unclear if a similar negativity bias is at play for perceptions that go beyond ideology, such as the degree to which partisans assume that the other political party dislikes and dehumanizes their own party (i.e., meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization). In the current research, we investigated the prevalence, accuracy, and consequences of meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization between political partisans in the United States.

The potential for meta-perceptions to sow political discord is supported by past research showing that ethnic and religious groups think that outgroup perceptions of the ingroup are more negative than those actually held by the outgroup (12–14), and that these exaggerated meta-perceptions are associated with support for intergroup aggression (15–17). For example, Kteily and colleagues (15, 17) examined the consequences of perceiving that the ingroup is disliked (i.e., meta-prejudice) and dehumanized (i.e., meta-dehumanization) by a competitive outgroup. Across a range of contexts and toward a number of target groups, these studies found that meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization are strong, independent, and complementary predictors of support for aggression toward the other side.

Therefore, both meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization are subject to a strong negativity bias: We think that other groups have more hostile attitudes and intentions than they do in reality (16, 17). Particularly, given American political partisans accessibility to the assessments of their own group by the other in a partisan media environment (18), we predicted that meta-perceptions would also be present and relevant between political partisans. If political meta-perceptions are subject to the same negativity bias present for ethnic and religious groups, then Americans may overestimate the levels of political animus. In addition, since meta-perceptions tend to drive negative perceptions of the other group (15), these negative meta-perceptions could become self-fulfilling by increasing negative perceptions of each side toward the other.

In the current research, we explore the possibility that negative perceptions thought to be held by the other political party are as follows: 1) perceived to be stronger than they are in reality, and 2) associated with intergroup hostility. We suggest that, although intergroup prejudice and dehumanization are significant and consequential, the degree of prejudice and dehumanization believed to be held by the outgroup may be exaggerated, which could then lead to greater intergroup hostility. To determine the strength and accuracy of negative meta-perceptions, in Study 1 we collected a representative sample of Democrats and Republicans and compared actual perceptions held by each group to the meta-perceptions each group inferred that the other holds toward them. To determine the persistence and consequences of negative meta-perceptions, in Study 2 we used a two-wave study to examine how consistent meta-perceptions are over time and how strongly meta-perceptions are associated with outcomes assessed 3 mo later.

Study 1

In a preregistered study (https://osf.io/hnq7j/) (19), we examined perceptions and meta-perceptions in a nationally representative sample of Democrats and Republicans. The primary goal was to determine the accuracy of meta-prejudice (i.e., the amount of affective prejudice thought to be held by the political outgroup toward the political ingroup) and meta-dehumanization (i.e., the extent to which the political outgroup is thought to dehumanize the political ingroup) (15). We also examined the relevance of these meta-perceptions to political outcomes. We focused on two intergroup outcomes in the current study: First, we assessed desire for social distance from members of the political outgroup, which has been demonstrated previously to impede partisan unity (4). Second, we aimed to capture desire for governance strategies that go beyond partisanship to include support for illegal or immoral behaviors that may fray democracy. To do this, we developed a measure of “outgroup spite”: support for policies and behaviors that help the ingroup political party but at the expense of the country and in contravention of democratic norms (for example, infringing on the Second Amendment [i.e., ensuring free speech] by shutting down liberal/conservative news outlets, illegally gerrymandering voting districts).

Results

See Table 1 for variable means (M's), standard deviations (SD's), and intercorrelations.

Table 1.

Study 1 descriptive statistics and variable intercorrelations for a representative sample of Democrats (A) and Republicans (B)

| A. Democrats | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1. Prejudice | — | |||||

| 2. Dehumanization | 0.57*** | — | ||||

| 3. Meta-prejudice | 0.25*** | 0.10* | — | |||

| 4. Meta-dehumanization | 0.29*** | 0.21*** | 0.58*** | — | ||

| 5. Social distancing | 0.38*** | 0.28*** | 0.20*** | 0.21*** | — | |

| 6. Outgroup spite | 0.20*** | 0.17*** | −0.16*** | −0.03 | 0.28*** | — |

| M's | 45.13 | 21.75 | 66.14 | 55.48 | 43.20 | 2.84 |

| SD's | 35.03 | 34.37 | 33.71 | 34.06 | 29.04 | 1.46 |

| B. Republicans | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1. Prejudice | — | |||||

| 2. Dehumanization | 0.62*** | — | ||||

| 3. Meta-prejudice | 0.25*** | 0.15** | — | |||

| 4. Meta-dehumanization | 0.31*** | 0.29*** | 0.58*** | — | ||

| 5. Social distancing | 0.37*** | 0.21*** | 0.09* | 0.13** | — | |

| 6. Outgroup spite | 0.34*** | 0.31*** | −0.04 | 0.10* | 0.42*** | — |

| M's | 42.19 | 22.28 | 70.56 | 59.37 | 40.04 | 2.88 |

| SD's | 37.15 | 34.05 | 29.10 | 34.68 | 26.46 | 1.44 |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

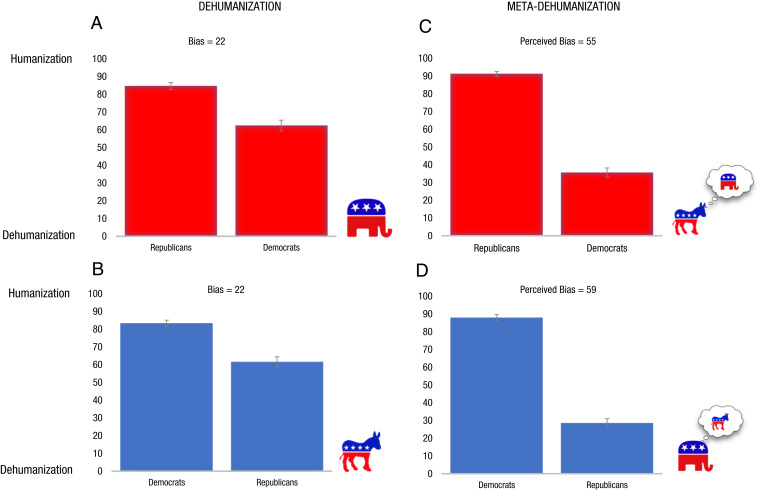

The primary goal of Study 1 was to determine the strength, prevalence, and accuracy of meta-perceptions. To do this, we first established ground truth levels of prejudice and dehumanization reported by the representative sample of Democrats and Republicans. Consistent with past research among ethnic and religious groups (20), Republicans felt colder toward Democrats (M = 34.55 and SD = 29.02) than toward Republicans (M = 76.74 and SD = 22.83; t[463] = 24.47, P < 0.001, and d = 1.62) and denied humanity to Democrats (M = 62.36 and SD = 35.70) more than to Republicans (M = 84.64 and SD = 21.35; t[461] = 14.06, P < 0.001, and d = 0.76); at the same time, Democrats felt colder toward Republicans (M = 32.82 and SD = 27.69) than toward Democrats (M = 77.95 and SD = 21.68; t[577] = 30.97, P < 0.001, and d = 1.81) and denied humanity to Republicans (M = 61.56 and SD = 34.19) more than to Democrats (M = 83.31 and SD = 21.89; t[580] = 15.26, P < 0.001, and d = 0.76) (see Fig. 1 for dehumanization and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 for prejudice). Democrats and Republicans did not differ from each other on expressed levels of warmth and humanity toward ingroup versus outgroup: prejudice (t[1,040] = 1.31, P = 0.191, and d = 0.08) or dehumanization (t[1,041] = −0.25, P = 0.804, and d = 0.02).

Fig. 1.

Study 1 dehumanization and meta-dehumanization reported by a representative sample of political partisans. Donkey = Democrats; elephant = Republicans; red bars = responses/perceived responses by Republicans; blue bars = responses/perceived responses by Democrats. (A and B) Humanity ratings of both target groups reported by Republicans (A) and Democrats (B), and ingroup–outgroup bias (i.e., dehumanization); (C and D) levels of humanity each group thought the other would report toward both target groups and the perceived bias (i.e., meta-dehumanization): how Democrats thought Republicans would respond (C), and how Republicans thought Democrats would respond (D). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Next, we examined meta-perceptions across both groups. As predicted, Democrats thought that Republicans felt colder toward Democrats (M = 21.99 and SD = 22.89) than toward Republicans (M = 88.13 and SD = 22.17; t[581] = 47.32, P < 0.001, and d = 2.94) and thought that Republicans denied humanity to Democrats (M = 35.60 and SD = 29.71) more than to Republicans (M = 91.07 and SD = 18.89; t[575] = 39.11, P < 0.001, and d = 2.23). Responses were similar for Republicans, who thought that Democrats felt colder toward Republicans (M = 14.29 and SD = 17.85) than toward Democrats (M = 84.85 and SD = 22.27; t[465] = 52.33, P < 0.001, and d = 3.50) and thought that Democrats denied humanity to Republicans (M = 28.47 and SD = 29.64) more than to Democrats (M = 87.85 and SD = 21.95; t[459] = 36.72, P < 0.001, and d = 2.28) (see Fig. 1 for meta-dehumanization and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 for meta-prejudice). Democrats and Republicans did not differ from each other on levels of meta-dehumanization (t[1,034] = −1.82, P = 0.070, and d = 0.11), but Republicans thought they were disliked by Democrats slightly more than Democrats thought they were disliked by Republicans (t[1,045] = −2.24, P = 0.025, and d = 0.14).

To gain insight into the types of people who may be more or less susceptible to negative meta-perceptions, we calculated mean levels of meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization by demographic subgroups (SI Appendix, Table S4), and we conducted follow-up analyses across the demographic variables we collected (race, gender, age, education, region, and strength of party identification) and across liberal–conservative political ideology. Although we found that some subgroups harbored slightly higher or lower levels of meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization, given the number of subgroups analyzed and the lack of replication across studies, these results could be spurious. By contrast, strength of liberal–conservative political ideology was significantly correlated with both meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization among Democrats (meta-prejudice: r = −0.18 and P < 0.001; meta-dehumanization: r = −0.14 and P = 0.001) and Republicans (meta-prejudice: r = 0.22 and P < 0.001; meta-dehumanization: r = 0.30 and P < 0.001).

Next, to examine the accuracy of intergroup meta-perceptions, we compared meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization inferred by each group to the actual ground truth levels of prejudice and dehumanization expressed by the representative sample of the other group. Overall, Democrats overestimated the levels of prejudice and dehumanization that Republicans harbor toward Democrats: Democrat meta-prejudice versus Republican actual prejudice (Mdiff = 23.95; t[1,044] = 10.91, P < 0.001, and d = 0.68) with 79% of Democrats numerically overestimating how much prejudice Republicans actually expressed toward Democrats; Democrat meta-dehumanization versus Republican actual dehumanization (Mdiff = 33.20; t[1,036] = 15.61, P < 0.001, and d = 0.97) with 79% of Democrats numerically overestimating how much Republicans actually dehumanize Democrats. In fact, Democrats’ estimates of dehumanization held by the average Republican were higher than levels of dehumanization expressed even by those who identified as strong Republicans (Mdiff = 19.95; t[704] = 5.90, P < 0.001, and d = 0.55), and Democrats’ estimates of Republicans’ prejudice were equivalent to levels of prejudice expressed by strong Republicans (Mdiff = 2.49; t[711] = 0.77, P = 0.441, and d = 0.08).

Republicans similarly overestimated Democrats’ levels of prejudice and dehumanization: Republican meta-prejudice versus how much prejudice Democrats actually expressed (Mdiff = 25.43; t[1,042] = 12.56, P < 0.001, and d = 0.79) with 81% of Republicans numerically overestimating the amount of prejudice actually reported by Democrats; Republican meta-dehumanization versus how much Democrats actually dehumanize Republicans (Mdiff = 37.62; t[1,039] = 17.47, P < 0.001, and d = 1.09) with 82% of Republicans numerically overestimating how much Democrats’ actually dehumanize Republicans. Again, Republicans’ estimates of prejudice and dehumanization expressed by the average Democrat were significantly higher than prejudice and dehumanization expressed even by the most strongly identified Democrats (prejudice: Mdiff = 14.42; t[656] = 5.29, P < 0.001, and d = 0.43; dehumanization: Mdiff = 30.24; t[653] = 10.01, P < 0.001, and d = 0.85).

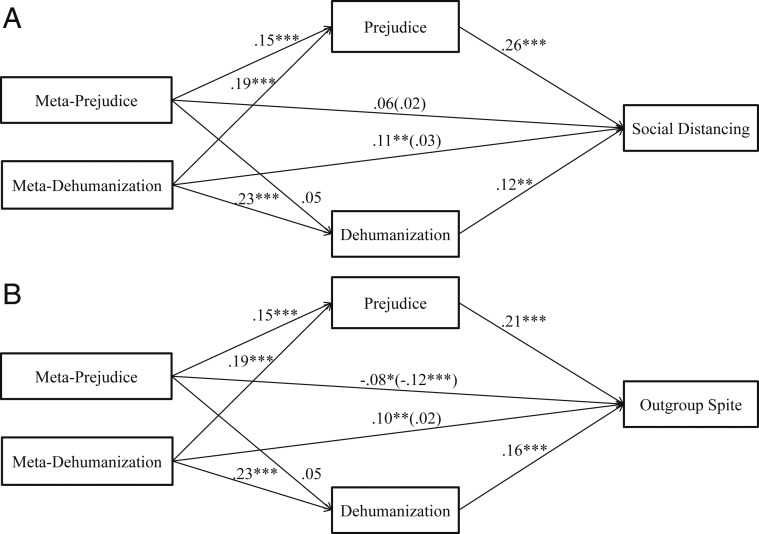

Our final set of analyses examined whether and how strongly meta-perceptions predicted the outcome measures. Previous research found that part of the association between feeling dehumanized and aggressive outcomes was indirect and mediated via dehumanization and prejudice (15, 17). That is, across a range of cultural contexts and target groups, part of the reason why those who feel dehumanized by an outgroup endorse hostile actions toward that outgroup is because they more strongly dislike and dehumanize the outgroup, in turn. We examined the same process here among American partisans using Hayes’ (2018) PROCESS macro (Model 4) with 5,000 bootstrap resamples (21). Consistent with previous research (15, 17), we found significant indirect effects from meta-dehumanization to both outcome measures via dehumanization and prejudice (Table 2). A full path model revealed that meta-dehumanization was significantly associated with both dehumanization and prejudice, while meta-prejudice was only significantly associated with prejudice (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Standardized total, direct, and indirect effects of meta-dehumanization on social distancing and outgroup spite via dehumanization and prejudice in Study 1, controlling for meta-prejudice

| Social distancing | Outgroup spite | |

| Indirect effect (dehumanization) | 0.03 [0.01, 0.05] | 0.04 [0.02, 0.06] |

| Indirect effect (prejudice) | 0.05 [0.03, 0.08] | 0.04 [0.02, 0.07] |

| Direct effect | 0.03 [−0.04, 0.10] | 0.02 [−0.05, 0.09] |

| Total effect | 0.11 [0.04, 0.18] | 0.10 [0.03, 0.17] |

Brackets represent 95% confidence intervals.

Fig. 2.

Study 1 path model examining perceptions among American participants, showing the link between feeling dehumanized and disliked by the other political party (meta-dehumanization and meta-prejudice) and supporting (A) social distancing and (B) outgroup spite via dehumanization of and prejudice toward the outgroup political party; standardized coefficients; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

We also preregistered an assessment of the accuracy and consequences of ideological perceptions about border security, a key political issue in the 2016 presidential elections and 2018 midterm elections (22). Although we found that ideological perceptions were inaccurate (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Table S3) and sometimes significantly associated with outcomes (SI Appendix, Table S2), these results did not fundamentally extend previous research on false polarization bias, beyond replicating those previous results. The ideological meta-perceptions were also difficult to compare directly to intergroup meta-perceptions since the constructs are distinct: Perceived ideological polarization is determined by perceived evaluations of the ingroup and the outgroup, whereas meta-perceptions are determined only by perceived evaluation of the ingroup and the outgroup by the outgroup. We report all results for ideological polarization, including comparisons between intergroup meta-perceptions and ideological misperceptions, in the SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Tables S2–S4.

Study 2

In Study 1, we used a representative sample to determine the prevalence and accuracy of meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization. In Study 2, we focused on the consequences of these meta-perceptions. We assessed perceptions, meta-perceptions, and outcome measures at two time points among a sample of Democrats and Republicans, which allowed us to examine the stability of meta-perceptions and whether meta-perceptions at Wave 1 predict outcomes over time. Wave 1 data were collected in early November 2018 right before the US midterm elections, and Wave 2 data were collected nearly 3 mo later, in late January 2019.

Results

See Table 3 for variable means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations.

Table 3.

Study 2 descriptive statistics and variable intercorrelations for a sample of Democrats (A) and Republicans (B) assessed at two waves

| A. Democrats | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1. Prejudice | 0.68*** | 0.54*** | 0.35*** | 0.33*** | 0.37*** | 0.37*** |

| 2. Dehumanization | 0.49*** | 0.59*** | 0.24*** | 0.40*** | 0.37*** | 0.33*** |

| 3. Meta-prejudice | 0.37*** | 0.21*** | 0.53*** | 0.52*** | 0.12*** | 0.09*** |

| 4. Meta-dehumanization | 0.27*** | 0.39*** | 0.50*** | 0.57*** | 0.21*** | 0.20*** |

| 5. Social distancing | 0.36*** | 0.34*** | 0.15*** | 0.23*** | 0.75*** | 0.47*** |

| 6. Outgroup spite | 0.31*** | 0.36*** | 0.15*** | 0.26*** | 0.47*** | 0.78*** |

| Wave 1 M's | 42.01 | 18.36 | 69.01 | 47.26 | 39.00 | 3.73 |

| Wave 1 SD's | 34.66 | 30.00 | 31.11 | 35.66 | 30.01 | 1.30 |

| Wave 2 M's | 40.73 | 18.19 | 66.81 | 44.89 | 38.94 | 3.60 |

| Wave 2 SD's | 33.39 | 28.99 | 29.64 | 33.90 | 29.93 | 1.30 |

| B. Republicans | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1. Prejudice | 0.69*** | 0.56*** | 0.37*** | 0.37*** | 0.43*** | 0.45*** |

| 2. Dehumanization | 0.61*** | 0.68*** | 0.20*** | 0.38*** | 0.41*** | 0.47*** |

| 3. Meta-prejudice | 0.37*** | 0.25*** | 0.60*** | 0.56*** | 0.12*** | 0.10** |

| 4. Meta-dehumanization | 0.40*** | 0.42*** | 0.54*** | 0.59*** | 0.23*** | 0.23*** |

| 5. Social distancing | 0.45*** | 0.47*** | 0.20*** | 0.31*** | 0.75*** | 0.55*** |

| 6. Outgroup spite | 0.49*** | 0.47*** | 0.15*** | 0.29*** | 0.52*** | 0.78*** |

| Wave 1 M's | 35.98 | 17.73 | 67.59 | 48.93 | 32.00 | 3.35 |

| Wave 1 SD's | 36.07 | 30.78 | 32.60 | 37.33 | 28.85 | 1.35 |

| Wave 2 M's | 38.21 | 18.42 | 68.32 | 50.61 | 33.48 | 3.39 |

| Wave 2 SD's | 34.85 | 29.90 | 32.81 | 36.11 | 29.40 | 1.41 |

Above the diagonal line in italics = Wave 1, below the diagonal line = Wave 2, and on the diagonal line in bold = Wave 1 correlation with the same Wave 2 variable; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

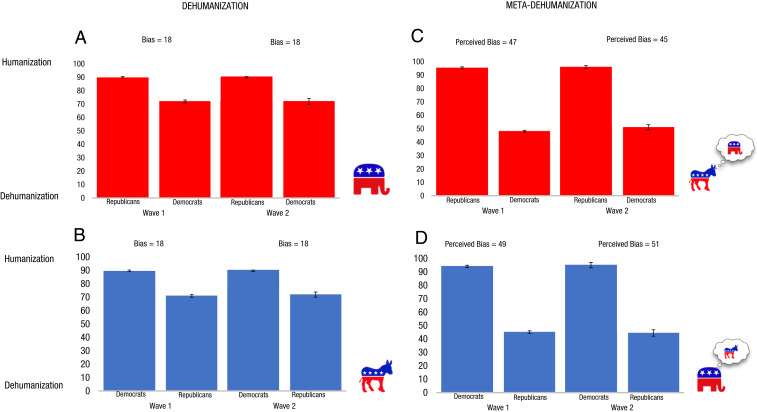

As in Study 1, Republicans expressed significant levels of prejudice and dehumanization: At each wave, Republicans felt colder toward Democrats (MWave1 = 38.56 and SDWave1 = 30.60; MWave2 = 37.50 and SDWave2 = 30.52) than toward Republicans (MWave1 = 74.54 and SDWave1 = 24.22; MWave2 = 75.71 and SDWave2 = 22.98; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 1.30) and denied humanity to Democrats (MWave1 = 71.90 and SDWave1 = 33.08; MWave2 = 71.94 and SDWave2 = 32.82) more than to Republicans (MWave1 = 89.63 and SDWave1 = 18.38; MWave2 = 90.36 and SDWave2 = 16.49; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 0.66); at the same time, in both waves, Democrats felt colder toward Republicans (MWave1 = 32.18 and SDWave1 = 29.17; MWave2 = 33.34 and SDWave2 = 29.38) than toward Democrats (MWave1 = 74.19 and SDWave1 = 22.87; MWave2 = 74.07 and SDWave2 = 22.57; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 1.55) and denied humanity to Republicans (MWave1 = 70.95 and SDWave1 = 33.43; MWave2 = 71.92 and SDWave2 = 33.42) more than to Democrats (MWave1 = 89.31 and SDWave1 = 18.27; MWave2 = 90.11 and SDWave2 = 16.99; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 0.68) (see Fig. 3 for dehumanization and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 for prejudice). Overall, levels of prejudice and dehumanization were similar for Democrats and Republicans (P's > 0.111 and d's ≤ 0.07) with the exception of prejudice scores in Wave 1, which were slightly higher among Democrats than Republicans (P < 0.001 and d = 0.17).

Fig. 3.

Study 2 dehumanization and meta-dehumanization reported by a sample of political partisans at two waves. Donkey = Democrats; elephant = Republicans; red bars = responses/perceived responses by Republicans; blue bars = responses/perceived responses by Democrats. (A and B) Humanity ratings of both target groups reported by Republicans (A) and Democrats (B) and ingroup–outgroup bias (i.e., dehumanization); (C and D) levels of humanity each group thought the other would report toward both target groups and the perceived bias (i.e., meta-dehumanization): how Democrats thought Republicans would respond (C), and how Republicans thought Democrats would respond (D). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Next, we examined meta-perceptions. Again consistent with Study 1, Democrats thought that Republicans felt colder toward Democrats (MWave1 = 23.34 and SDWave1 = 23.38; MWave2 = 25.11 and SDWave2 = 23.12) than toward Republicans (MWave1 = 92.35 and SDWave1 = 16.56; MWave2 = 91.93 and SDWave2 = 16.47; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 3.33) and denied humanity to Democrats (MWave1 = 48.02 and SDWave1 = 33.74; MWave2 = 51.03 and SDWave2 = 32.95) more than to Republicans (MWave1 = 95.28 and SDWave1 = 13.90; MWave2 = 95.92 and SDWave2 = 12.54; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 1.80). Similarly, Republicans thought that Democrats felt colder toward Republicans (MWave1 = 23.43 and SDWave1 = 24.80; MWave2 = 24.01 and SDWave2 = 25.08) than toward Democrats (MWave1 = 91.01 and SDWave1 = 17.23; MWave2 = 92.33 and SDWave2 = 15.95; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 3.16) and thought that Democrats denied humanity to Republicans (MWave1 = 45.16 and SDWave1 = 35.00; MWave2 = 44.44 and SDWave2 = 34.30) more than to Democrats (MWave1 = 94.09 and SDWave1 = 15.07; MWave2 = 95.05 and SDWave2 = 13.14; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 1.82) (see Fig. 3 for meta-dehumanization and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 for meta-prejudice). Democrats and Republicans did not differ from each other on levels of meta-prejudice (P's > 0.250 and d's ≥ 0.04) or meta-dehumanization (P = 0.237 and d = 0.05) except in Wave 2 where Republicans reported slightly higher levels of meta-dehumanization than Democrats (P < 0.001 and d = 0.16).

As in Study 1, we analyzed meta-perceptions across demographic subgroups (see SI Appendix, Table S4 for details). As in Study 1, meta-perceptions were largely consistent across demographic subgroups but were significantly correlated with levels of liberal–conservative political ideology for Democrats (meta-prejudice: Wave 1: r = −0.28 and P < 0.001, Wave 2: r = −0.23 and P < 0.001; meta-dehumanization: Wave 1: r = −0.18 and P < 0.001, Wave 2: r = −0.15 and P < 0.001) and Republicans (meta-prejudice: Wave 1: r = 0.17 and P < 0.001, Wave 2: r = 0.11 and P = 0.003; meta-dehumanization: Wave 1: r = 0.13 and P < 0.001, Wave 2: r = 0.14 and P < 0.001).

Intergroup meta-perceptions were exaggerated as in Study 1 by similarly high proportions of Democrats and Republicans (SI Appendix, Table S3). Democrats overestimated mean levels of prejudice and dehumanization that Republicans harbor toward Democrats: Democrat meta-prejudice versus Republican actual prejudice (MdiffWave1 = 33.03 and MdiffWave2 = 28.60; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 0.88) with, at least, 84% of Democrats at each wave numerically overestimating the amount of prejudice Republicans felt toward Democrats; Democrat meta-dehumanization versus Republican actual dehumanization (MdiffWave1 = 29.52 and MdiffWave2 = 26.47; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 0.88) with, at least, 71% of Democrats at each wave numerically overestimating the amount that Republicans deny humanity to Democrats. As in Study 1, Democrats’ estimates of prejudice and dehumanization by the average Republican were significantly higher than levels of prejudice and dehumanization expressed even by those who identified as strong Republicans at both waves (prejudice: MdiffWave1 = 13.91; MdiffWave2 = 8.52; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 0.27; dehumanization: MdiffWave1 = 17.14; MdiffWave2 = 15.72; P's < 0.001 and d's≥ 0.46).

Republicans similarly overestimated Democrats’ levels of prejudice and dehumanization. Republican meta-prejudice versus Democrat actual prejudice (MdiffWave1 = 25.57 and MdiffWave2 = 27.59; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 0.76) with, at least, 79% of Republicans at each wave numerically overestimating prejudice; Republican meta-dehumanization versus Democrat actual dehumanization (MdiffWave1 = 30.57 and MdiffWave2 = 32.42; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 0.90) with, at least, 71% of Republicans at each wave numerically overestimating amount of dehumanization held by Democrats. In both waves, Republicans’ estimates of prejudice and dehumanization expressed by the average Democrat were significantly higher than prejudice and dehumanization expressed even by the most strongly identified Democrats (prejudice: MdiffWave1 = 7.09; MdiffWave2 = 10.18; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 0.21; dehumanization: MdiffWave1 = 21.54; MdiffWave2 = 23.74; P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 0.59).

For Democrats and Republicans, meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization were also greater than the ground truth levels of prejudice and dehumanization reported by the representative sample of Democrats and Republicans in Study 1 (P's < 0.001 and d's ≥ 0.66).

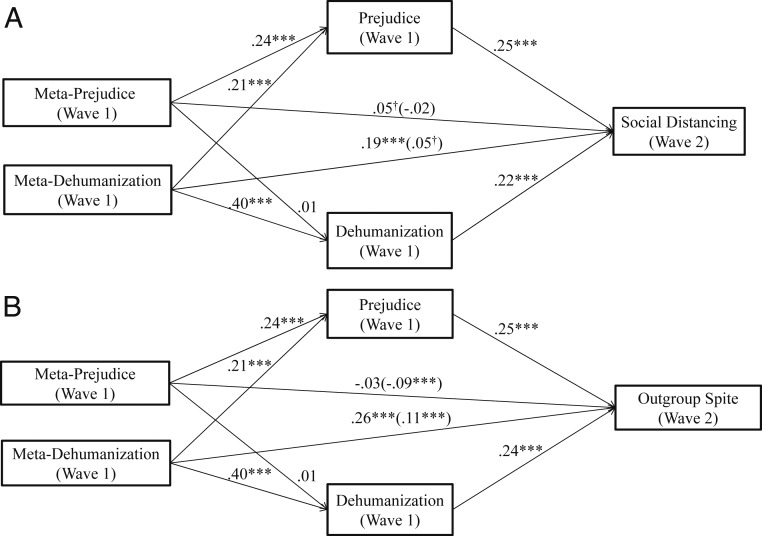

Finally, we determined how well intergroup meta-perceptions predicted outcomes. To take advantage of the two waves of Study 2, we examined whether meta-dehumanization measured at Wave 1 and the hostile outcome measures of outgroup social distancing and outgroup spite, both measured at Wave 2, were mediated by dehumanization and prejudice, both measured at Wave 1 (controlling for meta-prejudice measured at Wave 1). Analyses were conducted using Hayes’ (2018) PROCESS macro (Model 4) with 5,000 bootstrap resamples (21). Consistent with Study 1, as well as previous research (15, 17), we again found significant indirect effects from meta-dehumanization to the outcome measures via dehumanization and prejudice across our two outcome measures of social distancing and outgroup spite (Table 4). As in Study 1, meta-dehumanization was again significantly associated with both dehumanization and prejudice, while meta-prejudice was only significantly associated with prejudice (Fig. 4). All significant results remained significant when controlling for Wave 1 outcome measures.

Table 4.

Standardized total, direct, and indirect effects of meta-dehumanization on social distancing and outgroup spite via dehumanization and prejudice in Study 2, controlling for meta-prejudice

| Social distancing | Outgroup spite | |

| Indirect effect (dehumanization) | 0.09 [0.06, 0.11] | 0.10 [0.07, 0.12] |

| Indirect effect (prejudice) | 0.05 [0.04, 0.07] | 0.05 [0.04, 0.07] |

| Direct effect | 0.05 [−0.002, 0.10] | 0.11 [0.06, 0.16] |

| Total effect | 0.19 [0.14, 0.24] | 0.26 [0.20, 0.31] |

Brackets represent 95% confidence intervals.

Fig. 4.

Study 2 path model examining perceptions among American political partisans, showing the link between feeling dehumanized by the other political party assessed in Wave 1, and supporting (A) social distancing and (B) outgroup spite both assessed in Wave 2 via dehumanization of and prejudice toward the other political party both assessed in Wave 1; standardized coefficients; †P < 0.10; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

As in Study 1, we also assessed ideological polarization, here, across three ideological issues (borders, gun control, and police culpability for shooting a black civilian), which we report in the SI Appendix, Tables S3–S5-S6 and Figs. S4–S6.

General Discussion

Across two studies involving both representative and longitudinal samples, we found that Democrats and Republicans demonstrate a consistent and persistent bias in how much prejudice and dehumanization they express toward their political outgroup. Yet, despite these significant levels of prejudice and dehumanization, the amount of prejudice and dehumanization that each group thinks the other group harbors toward their own group is far greater: Across both studies, and over both waves of Study 2, Democrats and Republicans assumed that the levels of prejudice and dehumanization held by the other side (i.e., meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization) were 50–300% higher than what was actually expressed by a representative sample of outgroup political partisans. This research, therefore, reveals a very strong and persistent negativity bias in partisan meta-perceptions, which is consistent with the negativity bias in meta-perceptions observed between ethnic and religious groups (23).

One surprising aspect of the current results was the strength of the meta-perceptions negativity bias. The fact that estimates of meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization were even greater than the levels of prejudice and dehumanization reported by the most strongly identified partisans argues against the interpretation that people are merely attributing the views of the most partisan outgroup members to the outgroup as a whole. However, it is possible that meta-perceptions are driven not by the most identified outgroup members, but by the most outspoken, abrasive, or sensationalist members of the other group. Alternatively, or in addition, negative meta-perceptions could be driven by perceptions about outgroup composition (24), political and cultural elites (25), and/or through partisan media (26).

In addition to demonstrating the extent of partisan meta-perceptions, this research shows that meta-perceptions, particularly meta-dehumanization, are associated with politically relevant outcomes, mostly through their effects on prejudice and dehumanization. The indirect effects of meta-prejudice/meta-dehumanization on aggressive outcomes through prejudice/dehumanization parallels work with ethnic and religious groups (15, 17). The fact that intergroup meta-perceptions are associated with outcomes over time lends support to the idea that meta-perceptions may play a causal role in driving political polarization and discord by convincing both sides that the ideological divide is wider than it is in reality.

In the current research, we used a gestalt measure of dehumanization. This measure allowed us to efficiently assess and directly compare dehumanization by one group with meta-dehumanization inferred by the other group. However, this measure fails to distinguish between the different ways in which target groups might be dehumanized—for instance, animalistic versus mechanistic dehumanization (27) or blatant dehumanization characterized by denying the mind (28) versus blatant dehumanization that endows savagery (29). Therefore, although we show here that Democrats and Republicans dehumanize each other to similar degrees, we were not able to determine if they dehumanize each other in similar ways.

The fact that perceptions of political outgroups and behavioral intentions toward them are associated with meta-perceptions suggests that interventions that safeguard against or correct meta-perceptions may provide an indirect way of reducing partisan animus. Since meta-perceptions are exaggerated, this process would require people to update their meta-perceptions to match reality, which may be an easier “sell” than asking participants to identify with or like the outgroup more than they do currently. Previous research in the intergroup literature provides evidence that this approach can work (15). For example, correcting negative meta-perceptions that are believed to be harbored by Muslims against Americans effectively reduces dehumanization of Muslims (15). In fact, recent research provides evidence that correcting ideological polarization between political partisans effectively reduces negative intergroup outcomes (30). Since the current research suggests that intergroup meta-perceptions may be more potent predictors of negative intergroup outcomes than ideological meta-perceptions, interventions that correct intergroup meta-perceptions may be even stronger than those that target ideological meta-perceptions. Given the strong role of dehumanization in fostering intergroup aggression (15), exploring approaches that correct meta-dehumanization, in particular, may help mitigate toxic polarization that threatens bipartisanship and democratic norms.

Conclusion

Across a representative sample and a longitudinal sample, we find that Americans are clearly polarized by their dislike, dehumanization, and disagreement with the other party. However, the degree to which both parties think the other side dislikes and dehumanizes their own group is dramatically overestimated, which is associated with support not only for social distance from outgroup members, but also for spiteful partisan behaviors that promote the ingroup party at the expense of the country. Thus, a preference for spiteful and exclusionary governance is rooted in the shared illusion that American political partisans dislike, dehumanize, and disagree with each other more than they do in reality.

Study 1

Materials and Methods.

Participants.

A power analysis indicated that 105 participants per group would be required to detect a medium effect (d = 0.5) at an α of 0.95. Samples of 651 participants per group would be required to detect a small effect size (d = 0.2). To detect small–medium effects, we collected, at least, 500 Democrat participants and 500 Republican participants. We recruited 1,265 participants to complete the study through the nonpartisan research organization NORC at the University of Chicago; 212 participants failed an attention check question embedded in the survey (“Please select 5 for this question”), resulting in a final sample of 1,056 participants (584 Democrats and 472 Republicans), which was representative in terms of age (Mage = 47.54 y, SDage = 16.71 y), gender (54% female and 46% male), race (66% White, 15% Black, 15% Latinx, 2% Asian, and 2% Other), and region (regional breakdown: 18% Northeast, 22% Midwest, 38% South, and 22% West). (For additional details on sampling and demographic benchmarks used for weighting, see SI Appendix, Table S1). We use weighted values in all Study 1 analyses. Participants were compensated $2.00 for their time.

Measures and Procedure.

Prior to the start of the both studies, all participants were informed that this study was being conducted by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. They were told that the purpose of the study is to identify attitudes about social issues, that their participation in the study is completely voluntary, and that no identifying information (other than demographics) would be collected. All participants provided informed consent. Study procedures and protocols were approved by the University of Pennsylvania IRB prior to the start of the studies.

Demographics.

Participants first reported their race, age, gender, regional location, education, political ideology (liberal–conservative), and political affiliation (as strong Democrat, strong Republican, moderate Democrat, moderate Republican, lean Democrat, lean Republican, or do not lean/independent/none). We consider Democrats all those who indicated strong, moderate, or lean Democrat and Republicans all those who indicated strong, moderate, or lean Republican.

Prejudice.

We assessed prejudice with feeling thermometers (31). Participants rated how warm they felt toward each target group, using a sliding scale anchored at very cold/unfavorable (0) and very warm/favorable (100). Target groups included Democrats, Republicans, and filler groups (Americans, undocumented migrants, and Europeans). Presentation order of target groups was randomized within and across participants. As in Kteily et al. (2015) (32), we created a difference score (ingroup–outgroup) with higher scores indicating greater affective prejudice toward the outgroup.

Dehumanization.

We assessed dehumanization with the “Ascent of (Hu)Man” scale (32). Participants rated how “evolved and civilized” they considered each target group to be using a sliding scale spanning the Ascent of (Hu)Man image, ranging from the leftmost unevolved/uncivilized image (0) to the rightmost evolved/civilized image (100). Target groups were the same as used for the prejudice measure, and presentation order was again randomized. As with the prejudice measure, we assessed dehumanization as a difference score (ingroup–outgroup).

Meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization.

We modeled these measures after the prejudice and dehumanization measures. For each question, participants indicated how their political outgroup would rate Democrats and Republicans (and the other filler groups) on the feeling thermometer and Ascent of (Hu)Man scales. As with prejudice and dehumanization, we defined meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization as difference scores (how the outgroup was perceived to rate the outgroup versus ingroup).

Across individuals, presentation order of prejudice and dehumanization were randomized, order of meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization were randomized, and presentation order of the perception and meta-perception questions were randomized.

Social distancing.

To assess the degree to which partisans desire to remain separate from outgroup members, we used a measure based on the Bogardus (1947) social distance scale (33): Participants indicated how comfortable they would feel if their doctor, child’s teacher, or child’s best friend was a member of their political outgroup using a sliding scale ranging from not at all (0) to very (100). We reverse scored results and averaged responses together to obtain a measure of desired social distance from the outgroup (α's: Democrats = 0.95 and Republicans = 0.91).

Outgroup spite.

We assessed outgroup spite by determining participants’ willingness to harm the country or subvert Democratic norms in order to harm the outgroup political party with the following items: “I think [Democrats/Republicans] should do everything they can to hurt the [Republican/Democrat] Party, even if it is at the short-term expense of the country,” “I think [Democrats/Republicans] should do everything in their power within the law to make it as difficult as possible for [Trump to run the government effectively/Democrats to take part in governing the country],” “[Democrats/Republicans] should redraw districts to maximize their potential to win more seats in federal elections, even if it may be technically illegal,” “If [Democrats/Republicans] gain control of all branches of government in 2020, they should use the Federal Communications Commission to heavily restrict or shut down [Fox News/MSNBC] to stop the spread of fake news,” and “It’s OK to sacrifice US economic prosperity in the short term in order to hurt [Republicans’/Democrats’] chances in future elections.” We randomized presentation order for each participant and across participants. Participants responded using a Likert scale anchored at strongly disagree (1) and strongly agree (7) (α's: Democrats = 0.83 and Republicans = 0.81).

We also included in Study 1 questions to assess perceived ideological polarization, which we evaluate in the SI Appendix and a few exploratory items that were beyond the scope of the current research and, therefore, excluded from the following analyses.

Data Availability

All materials and data can be found at Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/hnq7j/ (19).

Study 2

Materials and Methods.

Participants.

We used the same power analysis criteria as in Study 1 and increased our sample size to account for potential attrition between Waves 1 and 2. We recruited 2,780 participants at Wave 1 from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Seventy-three participants failed the attention check question (“Please select 5 for this question”), leaving a final sample of 2,707 participants (1,579 Democrats and 1,128 Republicans). Of the 2,707 Wave 1 participants, 2,051 completed Wave 2 (74% retention). [Attrition (R2 = 0.03) was not predicted by political affiliation (P = 0.878), ethnicity (P = 0.879), or gender (P = 0.052) but was predicted by age (P < 0.001): younger participants were more likely to drop out of the study between Wave 1 and Wave 2.] One hundred and forty-two Wave 2 participants failed the Wave 2 attention check question (“Please select 5 for this question”), leaving 1,909 participants (1,115 Democrats and 794 Republicans) in the final Wave 2 sample (77% White, 8% Black, 6% Latinx, 6% Asian, and 3% Other; 53% female and 47% male; Mage = 39.89 y, SDage = 12.23 y; regional breakdown: 17% Northeast, 21% Midwest, 39% South, and 23% West). Although this sample was not nationally representative, it was similar to the benchmark data used for Study 1. (See SI Appendix, Table S1 for study demographic details compared to benchmarks). Participants were compensated $1.50 per wave for their time.

Measures and Procedure.

Demographics (Wave 1 only).

Participants answered the same demographic questions as in Study 1, and political affiliation was computed as in Study 1.

Perceptions and meta-perceptions.

We measured and computed prejudice, dehumanization, meta-prejudice, and meta-dehumanization as in Study 1.

Social distancing.

We assessed social distancing as in Study 1 (α's: Democrats: W1/W2 = 0.94/0.95 and Republicans: W1/W2 = 0.93/0.93).

Outgroup spite.

We assessed outgroup spite as in Study 1, but with a slightly modified set of six questions, which included two reverse-coded (R) items about support for bipartisanship: "I think the [Democrats/Republicans] should do everything they can to hurt the [Republican/Democrat] party, even if it is at the short-term expense of the country," "I think the [Democrats/Republicans] should [attempt to block Trump’s nominees for government by any means necessary/push through Trump’s nominees without any regard for Democrats’ objections]," "I think the [Democrats/Republicans] should do everything in their power within the law to make it as difficult as possible for [Trump to run the government effectively/Democrats to take part in governing the country]," “The [Republican/Democrat] party has proven that it does not deserve the good faith support of the [Democrats/Republicans] in any way,” “I support the [Democrats/Republicans] working with their [Republican/Democrat] counterparts in a bipartisan way (R),” and “I think the [Democrats/Republicans] should reason with and negotiate with the [Republicans/Democrats] to get things done (R)” (α's: Democrats: W1/W2 = 0.81/0.83 and Republicans: W1/W2 = 0.83/0.87).

As in Study 1, we also included in Study 2 questions to assess perceived ideological polarization (here, across three issues) (SI Appendix, Tables S3–S5) and exploratory items that were beyond the scope of the current research and, therefore, excluded from the analyses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jake Parelman, Roman Gallardo, and Julia Schetelig for their help with data collection and coding.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: All materials and data can be found at Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/hnq7j/.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2001263117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Svolik M., Polarization versus democracy. J. Democracy 30, 20–32 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore-Berg S. L., Hameiri B., Bruneau E., The prime psychological suspects of toxic political polarization. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci., 10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.05.001 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monmouth University , Americans feel divided on core values. https://www.monmouth.edu/polling-institute/reports/monmouthpoll_us_101419/. Assessed 3 January 2020.

- 4.Iyengar S., Lelkes Y., Levendusky M., Malhotra N., Westwood S., The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyengar S., Sood G., Lelkes Y., Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Q. 76, 405–431 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers J. R., Melnyk D., Why do I hate thee? Conflict misperceptions and intergroup mistrust. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 32, 1295–1311 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levendusky M., Malhotra N., (Mis)perceptions of partisan polarization in the American public. Public Opin. Q. 80, 378–391 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson R. J., Keltner D., Ward A., Ross L., Actual versus assumed differences in construal: “Naïve realism” in intergroup perception and conflict. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 68, 404–417 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westfall J., Van Boven L., Chambers J. R., Judd C. M., Perceiving political polarization in the United States: Party identity strength and attitude extremity exacerbate the perceived partisan divide. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 145–158 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambers J. R., Baron R. S., Inman M. L., Misperceptions in intergroup conflict. Disagreeing about what we disagree about. Psychol. Sci. 17, 38–45 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherman D. K., Nelson L. D., Ross L. D., Naïve realism and affirmative action: Adversaries are more similar than they think. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 25, 275–290 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vorauer J. D., Hunter A. J., Main K. J., Roy S. A., Meta-stereotype activation: Evidence from indirect measures for specific evaluative concerns experienced by members of dominant groups in intergroup interaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78, 690–707 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vorauer J. D., Main K. J., O’Connell G. B., How do individuals expect to be viewed by members of lower status groups? Content and implications of meta-stereotypes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75, 917–937 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kteily N., Bruneau E., Darker demons of our nature: The need to (re)focus attention on blatant forms of dehumanization. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 26, 487–494 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kteily N., Hodson G., Bruneau E., They see us as less than human: Metadehumanization predicts intergroup conflict via reciprocal dehumanization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 110, 343–370 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Brien T. C., Leidner B., Tropp L. R., Are they for us or against us? How intergroup metaperceptions shape foreign policy attitudes. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 21, 941–961 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kteily N., Bruneau E., Backlash: The politics and real-world consequences of minority group dehumanization. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 43, 87–104 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levendusky M., Malhotra N., Does media coverage of partisan polarization affect political attitudes? Polit. Commun. 33, 283–301 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore-Berg S. L., Ankori-Karlinsky L.-O., Hameiri B., Bruneau E., Exaggerated meta-perceptions predict intergroup hostility between American political partisans. Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/hnq7j/. Deposited 8 January 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Bruneau E., Kteily N., The enemy as animal: Symmetric dehumanization during asymmetric warefare. PLoS One 12, e0181422 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes A. F., An Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, (Guilford Press, ed. 2, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradner E., Merica D., Trump’s family separation policy has Republicans starting to panic about 2018. CNN Politics. https://www.cnn.com/2018/06/18/politics/family-separations-2018-midterms-republicans-trump/index.html. Accessed 18 June 2018.

- 23.Frey F. E., Tropp L. R., Being seen as individuals versus as group members: Extending research on metaperception to intergroup contexts. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 10, 265–280 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahler D. J., Sood G., The parties in our heads: Misperceptions about party composition and their consequences. J. Polit. 80, 964–981 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banda K. K., Cluverius J., Elite polarization, party extremity, and affective polarization. Elect. Stud. 56, 90–101 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bail C. A. et al., Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 9216–9221 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haslam N., Dehumanization: An integrative review. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 10, 252–264 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray H. M., Gray K., Wegner D. M., Dimensions of mind perception. Science 315, 619 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith D. L., Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others, (St. Martin’s Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lees J., Cikara M., Inaccurate group meta-perceptions drive negative out-group attributions in competitive contexts. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 279–286 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haddock G., Zanna M. P., Esses V. M., Assessing the structure of prejudicial attitudes: The case of attitudes toward homosexuals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 65, 1105–1118 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kteily N., Bruneau E., Waytz A., Cotterill S., The ascent of man: Theoretical and empirical evidence for blatant dehumanization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 109, 901–931 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bogardus E. S., Measurement of personal-group relations. Sociometry 10, 306–311 (1947). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All materials and data can be found at Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/hnq7j/ (19).