Abstract

A new viral disease named COVID-19 has recently turned into a pandemic. Compared to a common viral pneumonia it may evolve in an atypical way, causing the rapid death of the patient. For over two centuries, autopsy has been recognized as a fundamental diagnostic technique, particularly for new or little-known diseases. To date, it is often considered obsolete giving the inadequacy to provide samples of a quality appropriate to the sophisticated diagnostic techniques available today. This is probably one of the reasons why during this pandemic autopsies were often requested only in few cases, late and discouraged, if not prohibited, by more than one nation. This is in contrast with our firm conviction: to understand the unknown we must look at it directly and with our own eyes. This has led us to implement an autopsy procedure that allows the beginning of the autopsy shortly after death (within 1–2 h) and its rapid execution, also including sampling for ultrastructural and molecular investigations. In our experience, the tissue sample collected for diagnosis and research were of quality similar to biopsy or surgical resections. This procedure was performed ensuring staff and environmental safety. We want to propose our experience, our main qualitative results and a few general considerations, hoping that they can be an incentive to use autopsy with a new procedure adjusted to match the diagnostic challenges of the third millennium.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Early performed autopsy, Autopsy, Samples

Highlights

-

•

Early performed autopsy (within 1-2 hour from death) provides tissue samples for diagnosis and research of quality similar to biopsy or surgical resections.

-

•

Early samples collection reduces post-mortem artifacts, thus preventing the wrong interpretation of the morphological pictures observed.

-

•

Precise autopsy planning prevents risks for the staff.

1. Introduction

The autopsy has played an essential role in the classification and definition of the etiology and pathogenesis of diseases for over two centuries, since the pivotal work “De sedibus et causis morborum per anatomen indagatis” of G.B. Morgagni (Venezia, 1761). This role is still relevant, given the periodic appearance of new nosological entities and the resulting need to understand their characteristics, consequences on the human body and possible pharmacological treatment. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that new viral diseases and consequent epidemics will continue to appear with relevant consequences for public health. When a new infectious and diffusive disease appears the autopsy provides, other than the usual clinical and scientific data, crucial epidemiological information useful for the proper planning of hygiene and public health programs and contributes also to the correct address of health care expenditure. The autopsy ascertains the cause of death both in hospitalized patients and in people who died without medical assistance, transported to hospital or in a morgue. Last, but not least, the autopsy is a valid aid for training and education of clinicians themselves [[1], [2], [3]]. In recent months we have witnessed the emergency of a new global threat, the SARS-CoV-2, which produced a new disease (COVID-19) that quickly turned into a pandemic. Its epidemiology, pathogenesis and, therefore, therapeutic possibilities are still little known [4]. In the current pandemic scenario of SARS-CoV-2, the autopsy appears to be a crucial tool to clarify the virus target cells in human, the frameworks of organ damage and the biological mechanisms that lead to death or allow the patient to heal. The autopsy execution on a patient who died of SARS-CoV-2 meets two conflicting needs. First, the high infectivity and dangerousness of the virus that requires the adoption of rigorous but time-consuming methods to guarantee the safety of the personnel carrying out the investigation and to prevent the spread of the virus outside the autopsy room. On the other hand, the need to carry out the autopsy as soon as possible after death and to perform it quickly, in order to have as little tissue damage as possible from post-mortem degenerative phenomena [5]. The quality of the samples is essential for diagnostic and research activities, necessary to improve the standard of health care [[6], [7], [8]]. The practical challenge with the SARS-Cov-2 emergency led us to significantly change our operational autopsy protocol, to obtain qualitative technical results that go beyond the limits of this disease and that can be useful in a much wider range of situations. This article reports our modus operandi and the main qualitative results obtained and discusses the findings and the horizons of autopsy in the third millennium.

2. Methods

2.1. Aims of the autopsy

We performed ten autopsies on SARS-CoV-2 positive patients.

The major aims that guided us are the following: 1. minimize the risks for the personnel who performed the autopsy; 2. reduce the probability of spreading the virus into the environment through leakage of unfiltered air from the anatomical and surrounding rooms or through blood or other biological liquids; 3. obtain samples for diagnosis and research of quality similar to biopsy or surgical samples; 4. make a concrete operative contribution for doctors who followed the patients in the hospitalization wards; 5. give precise informations on causes of death to the relatives of the deceased.

2.2. Operating protocol for early performed autopsy (EPA)

The regulatory references framework in which we developed and applied our protocol was issued by the Italian Government's Ministry of Health and by the Governor of the Lombardy Region [9,10]. Our hospital is equipped with a Complex Unit (CU) of Infectious Diseases. The autopsy room and the arrival/sampling/inclusion areas of the biological samples of the C.U. of Pathological Anatomy are designed with a safety level three (BSL3, according to CDC) [11].

2.2.1. Method of ascertaining death

The patient's cardiac death is immediately confirmed by continuous electrocardiographic monitoring that verifies the constant absence of cardiac activity for no less than 20 min [12].

This procedure is almost never done in Italy; it is preferred to wait at least 16 h after the presumed death when the first putrefactive skin spots appear. If the patient died outside the hospital but was still transported to the hospital emergency room, the EPA protocol is applied only if it has passed less than 1 h since the presumed death. Our protocol sets that an EPA, complete of samples for electron microscopy and molecular investigations on RNA and proteins, must start within 3 h from the presumed patient's death. In our experience the effects of postmortem processes that arise after this time prevent a sufficient diagnostic quality for these types of examinations. When it is not possible to do an EPA, the autopsy is still carried out but only routine histological, immunohistochemical and molecular investigations on DNA are performed.

2.2.2. Before the autopsy

After the instrumental ascertainment of death, the patient is transferred to the autopsy room. While authorization procedures for the autopsy are in progress, the doctor in charge of the deceased patient and the director of Pathological Anatomy discuss the clinical aspects of the case and any question that the autopsy must answer. The goal of this type of autopsy is not only the recognition of the cause of death or of pathologies already described in medical literature, but also the understanding of the etiopathogenetic mechanisms of this new disease and the confirmation of the adequacy of the therapies in use.

This is made possible by the correlation between organ and cellular pathological findings and clinical aspects (symptoms, signs, laboratory and instrumental data). The EPA is a procedure that needs to be meticulously planned before it begins, particularly if it is performed on a patient with a potential high risk of infectivity. Nothing should be left to chance and, once the staff has entered the autopsy room, there must be no unforeseen incidents. The staff that performed the autopsy must be trained and tightly-knit to be able to make decisions quickly and to adapt their work to the needs of each specific case. In addition, the organs that need sampling also for special investigations must be planned first since these procedures lengthen the autopsy time.

2.2.3. The autopsy room

According to the rules of the CDC, “Autopsies on decedents known or suspected to be COVID-19 cases should be conducted in Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIRs)”. These types of rooms must be “at a negative pressure to surrounding areas”, with a “a minimum of 6 air changes per hour (ACH) for existing structures and 12 ACH for renovated or new structures” and “have air exhausted directly outside or through a high efficiency particulate aerosol (HEPA) filter” [11].

The WHO's guidelines firmly suggest Biosafety Level 3 (BSL 3) for autopsies performed on patients died for SARS-CoV-2 [13,14].

An autopsy room of BSL 3 must be organized as a surgical room: it must have two differentiated paths, one for entrance (“dirty” one) and one for exit (“clean” one). It must be equipped with adequate instruments and clothing checked and guaranteed. In addition, effective cleaning and sanitization of both the instruments, the sector tables and the areas used must be constantly planned. Personnel working in the room must have adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) [14] and tools that can guarantee a fast surgical act. A modern autopsy cannot be performed with old and blunt instruments. In the room, during the autopsy, there must be abundant availability of alcohol at 62–71 volumes to sanitize instruments and surfaces [15], 10% buffered formalin, five containers for formalin fixed samples (three medium-size for organs of the right hemibody, left hemibody and median axis, two big-size for brain and heart taken in full), four numbered containers with glutaraldehyde for electron microscopy samples, numbered containers with 70% alcohol solution for samples for extraction of DNA, numbered containers with RNAlater solution for samples for extraction of RNA and proteins and a transport bag to convey the containers with the samples outside the autopsy room. Any type of freezing in isopentane/nitrogen liquid must be performed inside the autopsy room only if a dedicated freezer at −40 °C/−80 °C is not available. Cell culture should be avoided in the absence of biohazard hoods for high biological risk.

2.2.4. The technical execution of EPA

The autopsy staff must be composed of at least two subjects, maximum three (Table 1 ): the first operator (the “dirty” one), the second operator (the “clean” one) and, possibly, a technician. In our case the dirty operator has always been a doctor specialized in autopsies. The technician must not replace the first operator in the evisceration and sampling of the organs because these maneuvers are essential for the correct medical diagnosis: the diagnosis is macroscopic and inspective (look, touch, smell), before histological or molecular.

Table 1.

Flowchart of EPA technical execution.

Autopsy staff

|

External inspection of the body

|

Scalp incision and opening of the skull

|

Evisceration of the brain

|

“Y” cut of the skin and subcutaneous planes for the examination of neck and trunk cavities and viscera

|

Opening of the rib cage

|

Opening of the pericardial sac

|

Opening in situ of the right chambers of the heart

|

Opening in situ of the left chambers of the heart

|

Eviscerate the heart

|

Removal of the lungs by cutting them from the hilum

|

Individual evisceration, weighing, sampling and examination of:

|

| Opening of the epiploon's back cavity |

In situ inspection and sampling of:

|

En bloc evisceration, sampling and examination of:

|

Mobilization, inspection and in situ sampling of:

|

The body of the patient must be positioned completely inside the sector table to prevent blood or biological liquids from leaking onto the floor. In particular, it must be taken care that the head is not at the edge of the table (often overdrawn and not aspirated) to prevent the dripping of blood from the incision of the scalp, thus producing small drops that splash in the environment. To minimize the dispersion of blood and biological fluids, it is essential to always operate in the area of the autopsy table: the viscera removed from the body must be placed either on the iron section table, placed above the patient's thighs, or in a large tray with high steel edges resting on the patient's legs, during weighing, macroscopic examination and sampling of the viscera.

The autopsy begins with a careful external inspection of the body. The length of the body and its state of nutrition must be detected, as the condition of the skin; any skin lesions and, in particular, those likely to be related to SARS-CoV-2 infection, should be sampled [16]. The scalp incision is made with a single cut from one mastoid process to the other, passing through vertex. The skull opening must be immediately suspended if there is a smell of bone dust in the environment: this means that the suction is not effective and that the risk of environmental contamination is unacceptable.

The evisceration of the brain, cerebellum and brainstem has to maintain their anatomical continuity. The block is weighed and samples are immediately taken for electron microscopy and for molecular investigations. After sampling for special surveys (Fig. 1 .A–C) the brain is immediately placed suspended inside the container with formalin, to prevent it from deforming by touching the bottom (Fig. 1.D–F). If there are no specific indications, the structures of the inner ear, located inside the petrous rock of the temporal bone, and the eyes are not removed, as the dura mater corresponding to the base and cranial vault. The “Y” cut is preferred by us to the longitudinal one conducted from the chin to the pubis for the examination of the viscera of neck and trunk. The examination and evisceration of neck and trunk organs is performed with a mixture of techniques, also on the basis of the specific clinical questions of each individual case (Table 2 ). After the brain examination, heart and lungs are the organs most frequently evaluated and extensively sampled. A swab for molecular detection (PCR) of SARS-CoV-2 is carried out, inserting the swab in large intraparenchymal bronchi or directly into the lung parenchyma. When there is clinical evidence of cardiac arrhythmias or sudden death, the heart is opened, dissected only in its lower third and fully placed in formalin to allow the study of its conduction system [17]. Cavities or blood vessels must be inspected for thrombus or clots that must be taken and measured. The next step is the evisceration and examination of liver and gallbladder in a single block; the liver parenchyma should be examined macroscopically with particular attention to the characteristics of the blood vessels contained in it. Then spleen, kidneys and adrenal glands are individually eviscerated, mobilizing the segments of the gastrointestinal tract that cover them, incising the retroperitoneal soft tissues that surround some of them and dissecting the hilar structures. These organs should also be examined macroscopically, measured and weighed. The epiploon cavity is opened and the pancreas is inspected: in the absence of focal lesions a full-thickness section of the body, approximately 5 cm in length, is removed, internally examined and sampled. In males, gonads are removed by herniating them in the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal by traction on the spermatic cord. It is advisable to always carry out samples for electron microscopy and molecular investigations of brain, heart (right and left ventricle, interventricular septum and emerging tract of the aorta and pulmonary artery), lungs, liver (right and left lobe), spleen, kidneys, skeletal muscles (2–3 different muscles), blood and bone marrow (from the first-second rib). All of this in addition to samples for histology and immunohistochemistry. If possible, examine also gonads and pancreas. Once the samples on the main parenchymatous organs have been obtained, the autopsy is completed by gutting in a single block the tongue in continuity with the viscera of the neck and the posterior mediastinum. Also these viscera must be carefully examined macroscopically, opening the hollow ones and sampling them for histological and immunohistochemical examinations. Two obstructive ligatures are performed, immediately after the Treitz ligament and about 1 cm from the ileocecal valve, to remove the small intestine by cutting it at the base of the mesentery; the intestine must be manually inspected along its entire length and, in the absence of focal lesions (which must be sampled for histological examination), two–three sections of a few centimeters are removed and fixed in formalin; in order to avoid the dispersion of feces, the section of the intestinal segments must be carried out by cutting the bowel between two adjacent ligatures for each section point. The large intestine is then mobilized by detaching it from the abdominal wall but without removing it. The course of ureters, bladder and, in females, uterus are inspected. If there are no focal lesions, they can be sampled in situ for histological and immunohistochemical analysis, but it is advisable not to open the bladder to avoid the spread of urine. If prostate samples must be performed, the bladder has to be opened and emptied by aspirating the content. After these procedures, the abdominal tract of the aorta and the large retroperitoneal vessels are inspected. Finally, the stomach is opened in situ to examine, and possibly sample, the mucous surface.

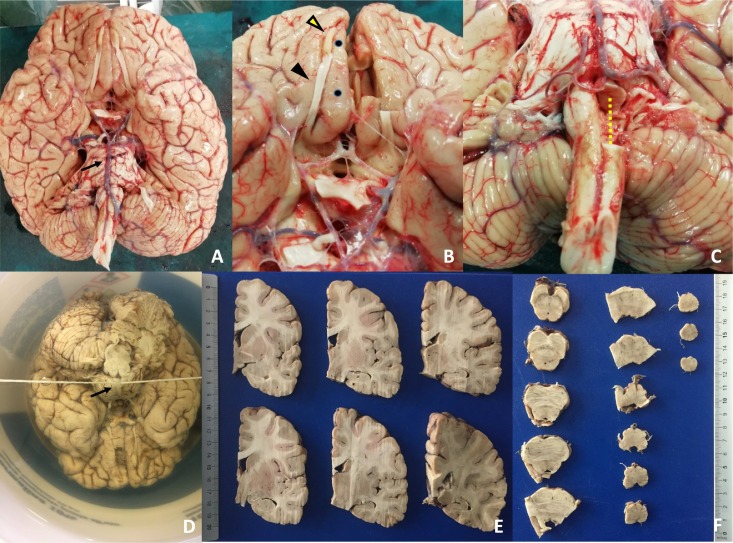

Fig. 1.

Brain from autopsies performed on patients died for SARS-Cov-2.

A. Inferior view of the brain, immediately after evisceration and weighing. The arrow indicates the basilar artery leaning over the pons. Its preservation is important for the correct fixation in formalin of the entire block consisting of the cerebrum, brainstem (midbrain, pons, medulla oblongata) and cerebellum (see figure D). B–C. Examples of areas sampled for ultrastructural examinations and molecular tests. The samples are taken only on one side so to use the contralateral for histological and immunohistochemical comparison. In B the yellow arrowhead indicates the olfactory bulb, the black arrowhead the olfactory tract and the two black points the gyrus rectus of the frontal lobe; the contralateral structures were removed and their fragments were fixed both in glutaraldehyde, in alcohol 70° and in RNAlater. In C the dotted yellow line highlights half of the medulla oblongata removed for special samples. D. Fixation of the brain suspended by immersion in formalin passing a thin rope under the basilar artery and knotting its ends at the joints of the handle of the container. The formalin has to be changed on the 2nd, 4th, 6th, 13th and 20th day; on the fourth day a full-thickness frontal section of the cerebrum is performed immediately at the front of the optical chiasma to facilitate the entrance of the formalin into the lateral ventricles. E–F. On the 27th day the brain (E), brainstem (F) and cerebellum are examined macroscopically and sampled for histological examination. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 2.

Autopsy techniques.

|

Virchow technique (removal of the viscera one by one) for: Lungs, spleen, kidneys, adrenals and gonads. |

|

Rokitansky's technique (opening and examination in situ of viscera and apparatus) for: Heart (before removing it), thorax large blood vessels, stomach, epiploon's cavity and pancreas, duodenum, large bowel, ureters, prostate, bladder and the retroperitoneal large blood vessel. |

|

Ghon technique (evisceration en bloc) for: Brain, tongue, organs of the neck and posterior mediastinum, liver and gallbladder, small bowel. |

| Letulle's evisceration technique (evisceration en masse) not performed to minimize the leak of blood, feces and biological fluids from the body |

Special notes:

|

3. Results

In our experience the rigorous application of the protocol described for the execution of complete autopsies did not produce accidents or negative consequences on the staff. To date, there have not been any case of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the staff assigned to the autopsy activity (detected with real-time PCR on nasopharingeal swab, serological tests for specific antibodies for SARS-CoV-2 and clinical evaluation). The instrumental assessment of cardiac death in patients allowed the rapid execution of the autopsy and the collection of samples for histopathological, ultrastructural and biomolecular tests. We thus obtained visceral samples of the highest quality, comparable to those of biopsy and surgical resections (Fig. 2, Fig. 4 .A–C). The comparison with the autopsy samples collected after 16 or more hours clearly demonstrates how the latter are affected by marked post-mortem artifacts, which can distort the correct interpretation of the morphological pictures observed. In addition, immunohistochemical tests on autopsy samples taken within 1–2 h from death are more reliable, which is particularly important when these tests are used to describe a new pathologic entity such as COVID-19 (Fig. 3 ). Immunohistochemistry, like biomolecular investigations performed on autopsy tissue samples, allows also to detect the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 in the body, detailing its distribution in single cell types (Fig. 4 .D). The rapid collection of samples for ultrastructural examinations gives the possibility to define, with a high degree of certainty, the damaging action of the pathology in progress differentiating it from post-mortem tissue and cellular changes (Fig. 5 ).

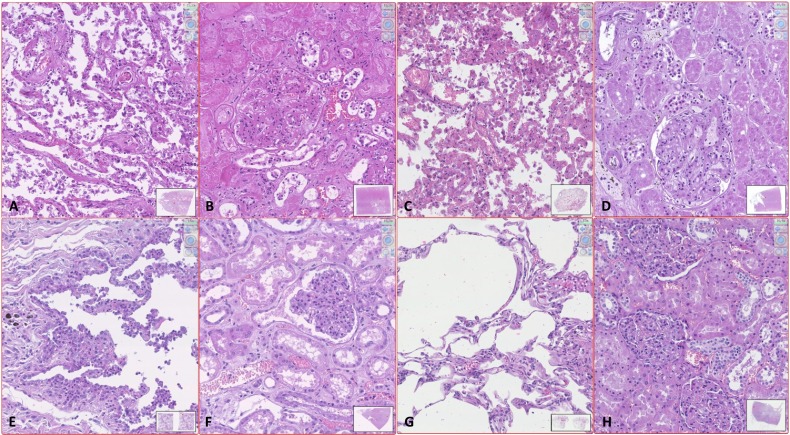

Fig. 2.

Standard quality of histology in early performed autopsy (EPA) versus late autopsy (LA) or surgical samples (SS).

A–D. Autopsy performed more than 24 h after death: examples of histological samples of patients SARS-CoV-2 positive (A and B) and patients SARS-CoV-2 negative (C and D). In both cases the lungs (A and C) have numerous pneumocytes inside the alveolar cavities and the alveolar septa are widely disepithelized; without immunohistochemical staining it is difficult to distinguish intraalveolar pneumocytes from macrophages and to differentiate type 1 from type 2 pneumocytes. The renal parenchyma (B and D) also shows an unsatisfactory morphological detail that makes it difficult to distinguish the damage consequent to the present pathologies from postmortem degeneration. The glomeruli are collapsed and difficult to read. The proximal tubules present loss of the nuclear basophilia and swollen cytoplasm with ill-defined limits; the distal tubules show widespread intraluminal disepithelization of the epithelium. E–F. Autopsy performed 2 h after death on patients SARS-CoV-2 positive. The pulmonary picture (E) appears markedly different from image A: the pneumocytes are widely adherent to the alveolar wall and swollen, in particular those of type 2; the capillaries in the septa are often dilated and the intraluminal erythrocytes are well preserved. The histological quality is comparable to that of the lung SS in image G. The morphological quality of the renal sample of EPA is also comparable to that of the renal SS (H), while it differs significantly from the quality of sample D from LA. In image F the tubular epithelia are not detached from the wall and the nuclei are well recognizable, the blood cells are well conserved and the glomerulus is not collapsed. G–H. SS of lung (G) and kidney (H). (Digital histological slide; Nanozoomer S360, Hamamatsu; in the box at the bottom right of each image it is indicated the area of the sample highlighted in the image; the magnification of the image is indicated in the upper right corner.)

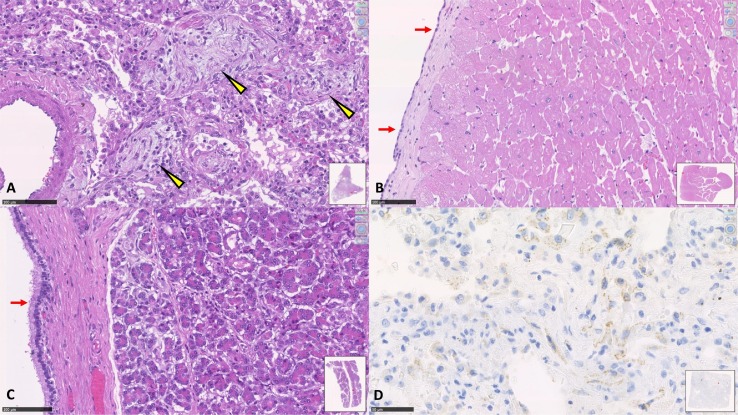

Fig. 4.

Standard quality of histological and immunohistochemical samples in SARS-CoV-2 EPA. A. Lung. The arrowheads highlight the areas of initial fibrosis within the pulmonary alveoli (DAD -diffuse alveolar damage-in advanced stage). B. Myocardium. The arrows show the excellent conservation of the epicardial mesothelial cells, histological picture of absolute rarity in autoptic samples performed after 24 or more hours from death. C. Pancreas. The histological detail appears very clear both in the acinar component and in the epithelium of the Wirsung's duct (arrows). D. Lung. Positivity of numerous cells to immunohistochemical staining for SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor. Positivity is granular in the cell cytoplasm. (SARS-CoV/SARS-CoV-2 spike Ab [1A9]; 1:50; Genetex International). (Digital histological slide; Nanozoomer S360, Hamamatsu; in the box at the bottom right of each image it is indicated the area of the sample highlighted in the image; the magnification of the image is indicated in the upper right corner.)

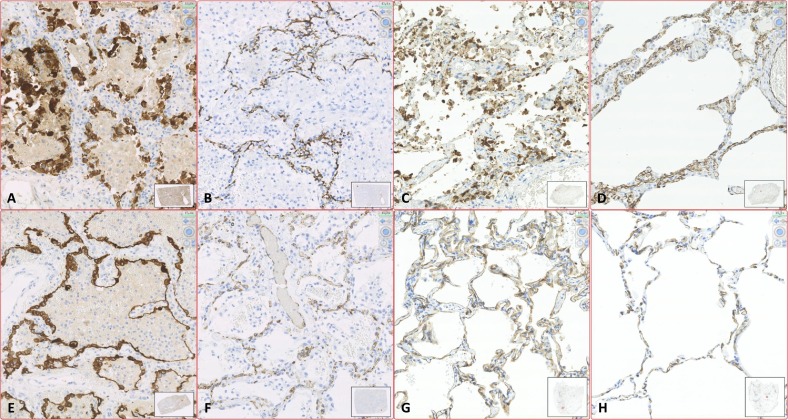

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical expression in lung of CK7 and CD34 in EPA versus LA or SS.

A–B. SARS-CoV-2 LA. The expression of CK7 (A) is still diffused and intense in the alveolar epithelium, but pneumocytes are often crowded in little unreadable aggregates, detached from the alveolar walls and poorly differentiable between type 1 and type 2. Numerous cellular debris are also stained affecting the legibility of the slide. Expression of CD34 in lung (B) allows the detection of numerous intraseptal vessels which are collapsed, difficult to distinguish and irregularly distributed, leaving doubt as to whether all this is an expression of the current illness or postmortem involution. C–D. Non SARS-CoV-2 LA. The number and characteristics of CK7-labelled epithelial cells are different from the sample shown in figure A; however, even this sample seems difficult to interpret given the extended detachment of pneumocytes, the variability in the intensity of cells positivity and the presence of colored cell debris. The expression of CD34 in the endothelium (D) allows a better morphological detail of the intraseptal vascular component. The capillaries are less collapsed than image B. E–F. SARS-CoV-2 EPA. The optimal preservation of the histological characteristics of the samples allows appreciating the histopathological features. In E the CK7 staining shows that the type 2 pneumocytes are widely magnified, clearly distinguishable from those of type 1 and minimally detached from the alveolar walls; the observed pattern is clearly different from image A, compared with those observable in surgical sample of patient not affected by SARS-Cov-2 (see image G). In F the CD34 staining shows the real distribution of the capillaries inside the alveolar septa which are still colonized by blood. G–H. CK7 (G) and CD34 (H) staining in SS of lung. (Digital histological slide; Nanozoomer S360, Hamamatsu; in the box at the bottom right of each image it is indicated the area of the sample highlighted in the image; the magnification of the image is indicated in the upper right corner.)

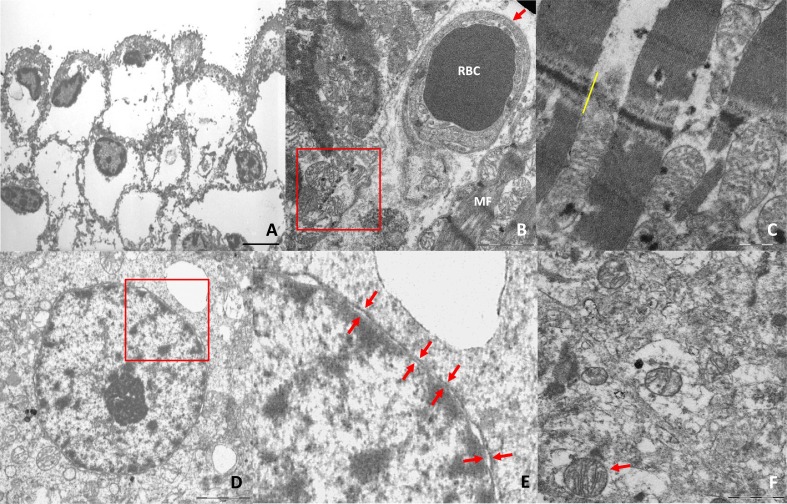

Fig. 5.

Standard quality of electron microscopy in EPA versus LA.

A. Skin fixed in glutaraldehyde from autopsy on subject without cutaneous pathologies, performed 10 h after death. The cellular morphological detail of the epidermis is seriously deteriorated due to the ongoing postmortem phenomena. It is observed a widespread displacement of the cytoplasm, with impossibility to recognize the organelles contained in it (not SARS-CoV-2 autopsy sample, archive; image kindly provided by Dr.ssa Martinelli C. – Dipartimento di Scienze della Salute, Università degli Studi di Milano). B–F. Quality of samples for electron microscopy on SARS-Cov-2 autopsy, performed 1–2 h after death. Images B and C show the characteristics of myocardium and a capillary (B) included in it. The ultrastructural alterations are clearly highlighted for the excellent preservation of tissues, demonstrated by the morphological detail of the mitochondria and A-bands of the myocells. The D–F images show that an autopsy conducted shortly after death ensures an excellent quality of morphological detail in the brain. This reinforces the possibility of distinguishing between postmortem degenerative and pathological alterations. (A: epidermis; bar: 5 μm. B: right ventricle myocardium; red arrow: blood capillary; RBC: red blood cell; MF: myofibrils; in the red box three well preserved mitochondria; bar: 2 μm. C: left ventricular myocardium; yellow bar: intercalary disc; numerous well-preserved mitochondria between the myofibrils; bar: 1 μm. D: Cortical neuron's nucleus in the gyrus rectus of the frontal lobe; the red box highlights the magnified area in E; bar: 3 μm. E: detail of the previous image: the arrows show the excellent conservation of the double envelop of the neuronal nuclear membrane. F: cytoplasm of a glial cell of the gyrus rectus of the frontal lobe; the arrow shows a well preserved mitochondria in the context of widespread cytoplasmic alterations.) (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

General guidance on how to perform an autopsy on a patient suspected or infected with SARS-CoV-2 have been recently published [11]; some autopsy studies on patients with this disease reported the observed histopathological patterns, in particular affecting the lung [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. In light of these indications, it seems useful to underline some practical aspects concerning the execution of autopsies in the countries where this virus is still widely spread and often undiagnosed. It is essential to consider as “potentially positive” also the patients not diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2, because maybe asymptomatic or not included in health surveillance programs: autopsy on these subjects must be performed with the protocol described for patients definitely infected. All autopsies should always be considered “potentially at risk of contagiousness”. In each hospital a specific operating protocol that allows to quickly ascertain the patient's death must be planned out so that the autopsy can be performed rapidly without waiting for the appearance of explicit putrefactive phenomena, which is the normal procedure in Italy [8]. The study of tissues markedly modified by postmortem biological phenomena can allow us to contemplate death but not the causes and the mechanisms that produced it. In our experience the histopathological and ultrastructural frameworks that emerge from an autopsy performed within 1–2 h after death differ significantly from those that we observed in an autopsy performed many hours or days after death and which have been presented in multiple autopsy studies on SARS-CoV-2 [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. The autopsy must be carried out quickly and planned before executing it, adapting its performance and methodology to the specific items of each case. These must be defined by the previous interview between the doctors and the pathologist. The maneuvers useful for macroscopically examining and sampling the organs identified as the main target in every single autopsy, will be privileged. This type of autopsy is not the occasion for elegant anatomical dissections, nor for the application of traditional teaching methods on evisceration procedures. It is essential to do it early and well, aiming for the planned goals, which may change from case to case. During the collection of material for ultrastructural, molecular or other tests, it is important to be aware that not all viscera can be sampled quickly, because the autopsy has its own procedure time and the more special samples are taken, the more time will increase. Before starting the autopsy, the evisceration and sampling sequence must be planned (especially when it is necessary to take tissue for electron microscopy) and be aware that the organs sampled after 1 h from the beginning of the autopsy will only be able to provide samples for histology and immunohistochemistry. In our experience the patients who undergo autopsy within few hours of death, bleed much more and the incision of very congested vessels can produce relevant blood splatters than in an autopsy performed after 24 h or more. In addition, patients hospitalized in intensive care for SARS-CoV-2 can be anticoagulated, a condition that increases the leakage of blood. During the autopsy the blood must absolutely not be dispersed in the environment surrounding the sector table. For this reason, the body must be positioned completely inside the sector table and the mobilization of large visceral masses outside the body should be avoided: Letulle's technique (evisceration en masse) therefore does not appear adequate. Blood, urine and other biological liquids must remain inside the body or aspirated by a vacuum pump in a container that can be sanitized after the autopsy. The commonly recommended use of rags or sponges to collect blood is totally inadequate and dangerous. Given the multiple clinical findings of neurological symptoms in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 [22,23], it appears indispensable to perform the evisceration and examination of the brain and brainstem, for the completeness of the autopsy and for the very few morphological data available today on the central nervous system. Our experience shows that the use of a valid circular saw with dust extraction system, combined with adequate PPE, does not put operators at risk and allows the doctor to obtain valid tissue samples. Given the importance of time, it seems useless to waste it performing the swabs for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in the usual locations for the living, when abundant material can be collected by inserting the swab directly into the lung parenchyma.

To date we are conducting further investigations on the samples obtained from early performed autopsies in order to evaluate the organ damage, particularly on SNC, heart and lung.

5. Conclusions

At the beginning of the third millennium, it is anachronistic to engage with the challenges of our discipline with the tools available to Morgagni, Malpighi, Vesalio or Virchow, when we have new and powerful weapons at our disposal. The limited possibilities to apply modern investigation technologies to tissues severely damaged by post mortem degenerative phenomena, has led many clinicians and pathologists to believe that autopsies are obsolete although, theoretically, they may be the most complete diagnostic tool. At present the autopsy should be performed quickly after the instrumental assessment of cardiac death, to ensure that the quality of tissues examined is similar to that of biopsy or surgical samples performed on the living. The forensic autopsy is the one with the most problems because of its rapid execution is often hampered by the need to perform it in front of the consultants of the parties involved. Since it is in everyone's interest to have well-preserved tissue samples available for valid histopathological, biochemical, molecular or toxicological analyses, a possible solution could be to video-transmit or video-record the stages of the autopsy that take place at the autopsy table and that, once carried out, are not repeatable. In our opinion the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic provides two major lessons. The first is that in all the areas where the virus is still circulating, even if not epidemic, autopsies must be considered at high risk of infectivity. This should prompt to increase the number of BSL 3 autopsy rooms in order to satisfy the needs of the territories. The second lesson is that rapid autopsies for health purposes appears mandatory in every day practice, even when it is not necessary to understand the etiology and pathogenesis of a new pathology. Rapid autopsies guarantee optimal tissues to apply the most sophisticated diagnostic methodologies. This supports the classic holistic autopsy examinations, which aims not only to define the cause of death but also, and perhaps above all, to reconstruct the pathological history and style of the patient's life. In conclusion even today the autopsy does not lose its etymological meaning, crucial for the correct progress of knowledge: “see with your own eyes” (from the ancient Greek “autòs” – same and “opsis” – sight). This is the fundamental part of the scientific method (observe - make a hypothesis - verify the hypothesis) masterfully described by Galileo Galilei, and the first step of every medical thought process.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the technical staff of the laboratories of histopathology, immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy of our Complex Unit, for their human and professional commitment that has never failed in this difficult moment. To: Falappa Federica, Nostro Tiziana, Pagliari Claudia, Pucci Sonia, Santoro Jessica, Soldano Giorgia Rita.

References

- 1.Bove K.E., Iery C. The role of the autopsy in medical malpractice cases, I: a review of 99 appeals court decisions. Autopsy Committee, College of American Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126(9):1023–1031. doi: 10.1043/0003-9985(2002)126. Sep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petros K., Wittekind C. Autopsy-a procedure of medical history? Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2014;109(2):115–120. doi: 10.1007/s00063-013-0214-6. [Epub 2013 Feb 17] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittekind C., Gradistanac T. Post-mortem examination as a quality improvement instrument. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(39):653–658. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cascella M., Rajnik M., Cuomo A. Features, evaluation and treatment coronavirus (Covid-19). Statpearls: treasure island. 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554776 [PubMed]

- 5.Istituto Superiore di Sanità Recommendations to perform autopsies in patients with sars-cov-2 infection. ISS Working Group on causes of death assessment covid-19. 2020. https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/0/Rapporto+ISS+COVID-19+n.+6_2020+autopsie.pdf/004df480-4222-6f44-bfee-0ef8b91c108a?t=1587106915706 ii, 7 p. rapporti iss covid-19 n. 6/2020 (in italian)

- 6.Stan A.D., Ghose S., Gao X.M. Human postmortem tissue: what quality markers matter? Brain Res. 2006;1123(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srinivasan M., Sedmak D., Jewell S. Effect of fixatives and tissue processing on the content and integrity of nucleic acids. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(6):1961–1971. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64472-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Start R.D., Cross S.S., Smith J.H. Assessment of specimen fixation in a surgical pathology service. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45(6):546–547. doi: 10.1136/jcp.45.6.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministero della Salute Circ. 2 maggio 2020, prot. n. 15280 - indicazioni emergenziali connesse ad epidemia covid-19 riguardanti il settore funebre, cimiteriale e di cremazione. http://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2020&codLeg=73965&parte=1%20&serie=null

- 10.Protocollo G120200015945. Emergenza covid-19. circolare ministero salute n. 11285 del 1.4.2020 e ordinanza del capo dipartimento di protezione civile n. 655 del 25 marzo 2020. attività funebre, cimiteriale e cremazioni. https://www.serviziterritoriali-asstmilano.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Nota-Regionale-prot-15945.pdf

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Collection and submission of postmortem specimens from deceased persons with known or suspected COVID-19. Interim guidance. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-postmortem-specimens.html

- 12.Gazzetta Ufficiale Serie Generale n.5 del 08-01-1994. Legge 29 dicembre 1993, n. 578, contenente: “Norme per l'accertamento e la certificazione di morte”. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1994/01/08/094G0004/sg

- 13.World Health Organization WHO post-outbreak biosafety guidelines for handling of SARS-CoV specimens and cultures. 2003. https://www.who.int/csr/sars/biosafety2003_12_18/en/

- 14.Li L., Gu J., Shi X. Biosafety level 3 laboratory for autopsies of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: principles, practices, and prospects. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:815–82110. doi: 10.1086/432720. [doi:1086/432720] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henwood A.F. Coronavirus disinfection in histopathology. J Histotechnol. 2020 doi: 10.1080/01478885.2020.1734718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sachdeva M., Gianotti R., Shah M. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.04.011. published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 29. S0923-1811(20)30149-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matturri L., Ottaviani G., Ramos S.G., Rossi L. Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): a study of cardiac conduction system. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2000;9(3):137–145. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(00)00035-1. May-Jun. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaller T., Hirschbühl K., Burkhardt K. Postmortem examination of patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8907. Published online May 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ackermann M., Verleden S.E., Kuehnel M. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. published online ahead of print, 2020 May 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wichmann D., Sperhake J.P., Lütgehetmann M. Autopsy findings and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barton Lisa M., Duval Eric J., Stroberg Edana, Ghosh Subha, Mukhopadhyay Sanjay. COVID-19 autopsies, Oklahoma, USA. Am J Clin Pathol. June 2020;153(6) doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mao L., Jin H., Wang M. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. April 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calcagno N., Colombo E., Maranzano A. Rising evidence for neurological involvement in COVID-19 pandemic. Neurol Sci. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04447-w. published online ahead of print, 2020 May 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]