Abstract

Prior pandemics and current news stories suggest that a “second pandemic” of potentially devastating mental health consequences will follow the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the changing contextual demands associated with the pandemic for many people, the mental health consequences of COVID-19 are likely to include exposure to a range of moral dilemmas. Such dilemmas may set the stage for the development of moral distress and moral injury in a broad range of contexts from the ER to the grocery store. In the current paper we offer an approach to responding to moral dilemmas presented by COVID-19. We propose a contextual behavioral model of moral injury that is relevant to those experiencing moral pain associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on this model, we offer two different approaches to intervening on COVID-19-related moral dilemmas. First, we propose the use of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Moral Injury (ACT-MI) among individuals suffering from moral injury. Second, to intervene on moral dilemmas at the level of the group, we propose the use of the Prosocial intervention. We offer case examples describing ACT-MI and Prosocial to highlight how these interventions might be applied to moral-dilemma-related concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic and discuss implications for future research.

Highlights

-

•

CBS can be applied to COVID-19-related moral distress and moral injury.

-

•

ACT-MI may be used to intervene on COVID-19-related moral distress and injury.

-

•

Prosocial may help groups respond to moral dilemmas and could prevent moral injury.

The full psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is yet unknown. However, if literature published following prior pandemics (e.g., H1N1) and epidemics (e.g., Ebola) (Hossain, Sultana, & Purohit, 2020; Mak, Chu, Pan, Yiu, & Chan, 2009) are any kind of harbinger for what is to come, COVID-19 will create a “second pandemic” – one that includes mental health consequences ranging from depression to anxiety to PTSD and other negative outcomes. Indeed, Hossain et al. (2020) learned from their review that these types of mental health problems were experienced by individuals undergoing quarantine and isolation, a common safety precaution for COVID-19. Provision of mental health services is likely to increase as COVID-19 continues to motivate drastic changes in lifestyle, increasing the risk for those who are already vulnerable.

In the current paper we aim to provide a framework for responding to moral dilemmas in the context of COVID-19. First, we briefly review the relevant literature on moral dilemmas and mental health, describing the research on both moral distress and moral injury. Next, we provide a contextual behavioral model of moral injury that is relevant to those experiencing moral pain in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on this model, we propose approaching treatment and prevention of COVID-19-related moral injury with contextual behavioral science (CBS). At the level of intervening on individual suffering, we propose using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Moral Injury to facilitate moral healing (ACT-MI; Farnsworth, Borges, Drescher, & Walser, 2020). At the level of intervening on suffering within small groups, we propose the use of Prosocial (Atkins, Wilson, & Hayes, 2019) as an application of moral healing and as a moral injury prevention strategy during COVID-19. Case examples describing ACT-MI and Prosocial are offered to highlight how these interventions might be applied. Finally, we discuss implications for future research.

1. Moral dilemmas during COVID-19

Morally challenging dilemmas can range in nature and be experienced at both the group and individual level. For instance, group level dilemmas might include conflicts between political or social priorities, such as governments feeling pressured to reopen quarantined economies even in the face of rising death tolls. Moreover, decisions to reopen do not equally impact all citizens. Some groups are more likely to be harmed by COVID-19. For families with jobs where telework is an option and with financial stability, the biggest challenge of staying home to protect one's family might be working productively with no childcare. However, for low income workers living in multi-generational homes, all the available choices may be fraught with actual risk to life for self or others. Working in an “essential” job may result in COVID-19 exposure which may be even more dangerous for older family members at home. Working in a job with no sick leave may result in sick individuals choosing to go to work and expose others, in order to be able to feed their own families. The risks of these choices are even more elevated when families have no health insurance and must choose between seeking care or providing for family needs. Specifically, racial and ethnic minority groups have been found to be disproportionately affected by COVID-19 due to significant social inequities including living conditions, work circumstances, and lower access to health care (CDC, 2020 June 4). The impact of preventing mass casualties versus mass economic fallout reflect competing priorities that prompt questions about what is ethical, proper, or decent.

Moral dilemmas at the individual level also occur and may include decisions about protecting oneself over others. These dilemmas can affect individuals (e.g., “What do I need to do to feed my family?") but also have social implications. An alarming example of this kind of morally taxing situation involves a known Internet and television personality, Alex Jones, angrily and vividly talking “about how he will make sure his daughters don't starve … by eating his neighbors” (Cohen, 2020 May 2).

In this case, the claim involves protecting one's family, viewed by many as morally correct. The consequences of Jones' on air behavior are unknown, however, we do have evidence that emotional displays can regulate social behavior (Van Kleef, 2009), being notably true for people who are influential or in positions of power (Keltner, Van Kleef, Chen, & Kraus, 2008). Followers of those in power may be swayed in ways that harm social cooperation, another moral stance. By tapping into fears about food and money shortages, Jones presents an interesting case of moral challenge. Indeed, those who would balk at this provocative call to cannibalism have felt it necessary to counter his call, see “Please Don't Eat Your Neighbor” (Cohen, 2020 May 2).

Other examples of individual and social dilemmas include people fleeing high-risk communities (i.e., New York City) to shelter in lower risk communities (i.e., country homes and rentals) bringing into tension the moral correctness of seeking safety for oneself and immediate family at the expense of the larger community. For instance, if those who are economically privileged flee, it may contribute to the depression of economies in high-risk communities. Those of less economic privilege may be forced to stay in their communities and work, but with the loss of financial contributions to the local economy, more underprivileged may be laid off, potentially increasing the negative consequences of COVID-19. Additionally, traveling from a high-risk community to one that is lower risk, could spread COVID-19 to communities that had previously been protected. A wide array of other decisions pose similar social and moral questions: going to work versus staying home, visiting a loved elderly person and placing them at risk, deciding whether to wear a mask in public, eating out in restaurants during re-opening, traveling, sending children to daycare, etc. The potential mental health consequences of these cumulative moral dilemmas can be profound.

COVID-19-related moral crises will undoubtedly take a toll. The impact, for instance, of nursing homes hiding infection and staff being unable to address the needs of the residents in these settings followed by mass death may not only be a moral burden for those directly involved, but for broader communities recognizing their lack of resources or inability to respond.

It is our contention that over the course of this pandemic, COVID-19 will give rise to significant values conflicts. The resulting moral distress and moral injury will have mental health outcomes and need for intervention even after the end of the pandemic.

2. Moral distress

Moral distress is the suffering experienced by individuals who feel morally responsible but are constrained from doing what is right in a specific situation (Mitton, Peacock, Storch, Smith, & Cornelissen, 2010). This distress arises when a values dilemma is presented based on needing to make a choice between multiple courses of action. Moral distress was initially explored in the nursing literature (Jameton, 1993). Contemporary models of moral distress highlight five key components: 1) complicity in choices that lead to a values violation, 2) lack of voice in those choices, 3) wrongdoing associated with professional (not personal) values, 4) repeated experiences of moral questioning, and 5) events that occur at three levels of root causes (patient, unit, system) (Epstein, Whitehead, Prompahakul, Thacker, & Hamric, 2019; Whitehead, Herbertson, Hamric, Epstein, & Fisher, 2015). The professional suffering from moral distress at the systems level, for example, knows the moral action that they believe to be right but is unable to proceed due to hierarchical or institutional constraints (Oh & Gastmans, 2015), often leading to a lack of resources needed to provide competent and ethical care (Musto & Schreiber, 2012) at the level of the individual.

During a pandemic, a morally distressing event might include scenarios wherein providers need to decide who will receive the limited or scarce available treatment and who will not. Mental health outcomes resulting from these types of moral dilemmas include initial responses such as anger, frustration, and anxiety (Lamiani et al., 2017). Emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (Ohnishi, Ohgushi, Nakano, et al., 2010) may also occur. Secondary reactions include burnout (Hamaideh, 2014) depression, feelings of worthlessness, and nightmares, while physiological responses might include heart palpitations, headaches and diarrhea (Lamiani et al., 2017). Although the moral distress literature emphasizes health care workers, moral distress is relevant in any context causing individuals to transgress a value or moral principle. Treatments for moral distress have not been well-defined and researched. However, a small body of treatment research on moral injury, a construct that has emerged in the mental health literature, is applicable.

3. Moral injury

Unlike the construct of moral distress developed largely in the medical field, moral injury is a concept initially conceived in the context of combat. Psychiatrist Jonathan Shay (1994) first described moral injury in his treatment of Vietnam combat veterans as “a betrayal of what's right” by someone with authority in a high-stakes situation (p. 20). Drescher & Foy (2008) and Litz (2009) expanded on this definition. Litz et al. (2009) describe moral injury as “the lasting psychological, biological, spiritual, behavioral, and social impact of perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations” (p. 697). (Litz et al., (2009)) model is useful in conceptualizing the potential consequences of moral transgressions. A limitation of this model, however, is that the thoughts and emotions that follow a moral transgression are conceptualized as causal to moral injury. An alternative approach to this syndromal model of conceptualizing psychopathology is applying a functional contextual framework to understanding suffering (Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette, & Strosahl, 1996; Follette & Houts, 1996).

Farnsworth, Drescher, Evans, and Walser (2017) offer a functional contextual model where experiential avoidance is delineated as the factor leading to the development of moral injury. First exposure to morally injurious events are described which lead to moral pain. Moral pain is viewed as an evolutionarily adaptive response to violating one's moral values. Rather than conceptualizing moral pain as a factor that directly causes moral injury, within the functional contextual approach attempts to control or avoid the experience of moral pain are what lead to moral injury through impairing functioning.

Within this framework, potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs) are situations that occur in high-stakes environments where one's moral code or values are violated (e.g., in the context of war, killing a child). These PMIEs cause moral pain. Moral pain often includes moral emotions such as guilt, shame, disgust, anger, and contempt, as well as cognitions associated with blaming oneself (e.g., the thought “I am monster” because of the PMIE) or others (e.g., the thought “My supervisor is evil” because of the PMIE). People tend to experience more significant consequences when tangible harm results from the PMIE.

Moral injury occurs through rigid efforts to avoid or control moral pain. These control efforts often negatively influence a person's life. While the functional contextual model of moral injury has been most researched among warzone veterans, this model was developed with general human suffering related to moral dilemmas in mind (Farnsworth et al., 2017). Non-war related moral dilemmas have increasingly been recognized as potential sources of moral injury (e.g., Chapalo, Kerig, & Wainryb, 2019; Steinmetz, Gray, & Clapp, 2019; Evans, Walser, Drescher, & Farnsworth, 2020). These definitions of PMIEs, moral pain, and moral injury all bear relevance to the kinds of scenarios people have faced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Moral distress and moral injury in the time of COVID-19 pandemic

Moral distress and moral injury are two distinct, but related constructs that developed in parallel, the former with a focus on health care and the latter with a focus on combat. The moral dilemmas described in the moral distress literature are somewhat broader and may be conventionally considered less “high-stakes” than the PMIEs described in warzone scenarios. Yet morally injurious events always include moral dilemmas. Moral distress overlaps somewhat with the concepts of exposure to PMIEs and moral pain, but does not speak to the difficulties in functioning that emerge as a result of inflexible responding to these experiences which characterizes moral injury. Within the functional contextual model the developement of difficulties in functioning is precisely described and points to potential prevention and treatment options, which could be valuable for several populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic including health care workers, first responders, and those affected directly by the virus.

5. A contextual behavioral model applied to moral injury during COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a novel context for responding. We are newly motivated to wear masks and gloves. We practice social distancing, work from home, and avoid physically interacting with family, friends, and neighbors. The context of the pandemic has also given rise to moral dilemmas, causing PMIEs. For instance, many cannot afford to stay home for financial, health, or family reasons. From grocery store employees to doctors, those in the position of serving as essential workers face a constant tension between providing critical services to sustain the community and considering their own and their family's health, safety, and livelihood. People are faced with choosing between multiple important valued domains like contribution, health, and family. Choosing to pursue one valued domain over another could negatively impact other areas of meaning and importance, potentially resulting in behavior that is inconsistent with a personally held moral value, creating exposure to a PMIE.

6. PMIEs during COVID-19

As a first example, PMIEs may be more likely during COVID-19 for health care professionals when they are unable to engage with their values in a contextually flexible manner due to the demands of the pandemic. They may be more likely to be exposed to PMIEs in the context of COVID-19 (Borges, Barnes, Farnsworth, Bahraini, & Brenner, 2020) when they feel forced, based on the demands of a high-stakes situation, to choose between multiple values, thus inherently engaging with some of those values to a lesser degree. PMIEs can include one's actions ranging from doing something they felt they should not have done to failing to do something they believe they should have done. PMIEs can also include feeling betrayed by other people's actions or inactions. Specific PMIEs among providers may include those related to triaging COVID-19 patients, discharging COVID-19 patients, working directly with dying COVID-19 patients, witnessing others engage in unethical practices related to COVID-19 and not intervening, and being told by hospital administrators that the medical equipment needed is not available to save the lives of patients. Other health care providers are also at risk. Emergency medical technicians and first responders might experience PMIEs associated with their roles providing care to COVID-19 patients.

Members of the community affected by the virus are also vulnerable to exposure to PMIEs. Unintentionally infecting family, friends, and colleagues with COVID-19, continuing to work in a high risk environment to support one's family while also unintentionally passing COVID-19 onto them and causing severe illness, injury, or death, and being unable to visit dying family members are just a few examples of PMIEs among those with COVID-19 (e.g., Saslow, 2020, May 30). For example, essential employees like grocery store workers and those working at meatpacking plants might be at increased risk for PMIEs. One grocery worker described their experience of going to work in keeping with a PMIE when they equated work with “feeling like a war zone” (Bhattarai, 2020 April 12). An individual working at a meatpacking plant stated, “How many more have to fight for their life, how many more families have to suffer before they realize we are more important than their production?” (Jordan & Dickerson, 2020 April 9).

7. Moral pain during COVID-19

When someone's moral values are violated through a PMIE, moral pain is considered a prosocial response. Painful moral emotions serve important functions to protect the survival of the social group (Farnsworth, Drescher, Nieuwsma, Walser, & Currier, 2014; Wilson, Hayes, Biglan, & Embry, 2014). Self-directed moral pain related to social functioning could include shame for continuing to work due to the need to provide for one's family while unintentionally transmitting the virus to family members and coworkers, self-blame related thoughts for the death of a patient with COVID-19, and guilt for not being present to support dying relatives. Moral pain might also take the form of other-directed emotions and cognitions which could include anger, disgust directed at others, contempt, and cognitions related to blaming others for COVID-19. Some examples of other-directed moral pain could include feeling betrayed concerning the behavior of political leaders, neighbors, bosses and administrators, colleagues, and patients in the context of the pandemic. For example, a mental health provider might be told by an administrator that they must provide face-to-face rather than telehealth care. This might create unnecessary COVID-19 exposure for the patients they see, causing some to contract the virus and resulting in the provider's contempt toward the administrator.

8. Moral injury during COVID-19

Among those experiencing moral pain during the COVID-19 pandemic, moral injury may develop through attempts to excessively block, avoid, or control moral pain to facilitate experiential avoidance. Efforts to get rid of moral pain may cause individuals to avoid triggers associated with the experience. This disrupts values-based living connected to moral pain. As an example of the relationship between values and pain in moral injury related to COVID-19, if a health care provider attempts to block the shame they feel concerning failure to save a man who has the virus, they might also avoid contact with their spouse. For the provider, interacting with her husband could evoke the very feelings of shame that she is attempting to avoid. This avoidance may cause immense social, psychological, and spiritual suffering.

In addition to isolation and disconnection from relationships of importance, moral injury may also be associated with detachment from spiritual practice, disengagement from work, and discontinuing self-care, as acting in any of these valued domains could simultaneously evoke moral pain. These functional impairments have been studied among warzone veterans and service members who have sustained moral injuries or who have been exposed to PMIEs (Borges et al., 2020; Currier, Holland, & Mallot, 2014; Purcell, Koenig, Bosch, & Maguen, 2016). Mental health consequences in these populations have been associated with substance use, depression, PTSD, and suicidal ideation and behavior (Battles et al., 2018; Bryan, Bryan, Roberge, Leifker, & Rosek, 2018; Currier et al., 2014; Currier, McDermott, Farnsworth, & Borges, 2019).

These moral injury outcomes have been apparent in recent news articles. For example, a top emergency room doctor died by suicide following her tireless efforts to provide treatment to COVID-19 patients at a New York City Hospital during the peak of the pandemic (Watkins, Rothfeld, Rashbaum, & Rosenthal, 2020 April 27). The doctor's father stated, “She tried to do her job and it killed her.” A second person's father died after contracting the virus from him. He stated, “I just killed my dad. I gave this to my dad … It's an odd feeling like you're not at peace … you can't rest because you're still dealing with the guilt” (Schuppe, 2020 May 16). While it is unclear the extent to which these events were caused by or now cause moral injury, scenarios like them highlight the relevance of moral healing given the potentially devastating mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

9. Moral healing during COVID-19

Healing from moral injury requires a willingness to feel moral pain in the service of creating meaning, purpose, and vitality. This involves reengaging areas of life that are often sources of suffering during moral injury. Relationships, spirituality, and self-care are pursued while simultaneously making room for moral pain in the presence of these valued domains. To facilitate moral healing for individuals suffering from moral injury during the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe that an intervention like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Moral Injury (ACT-MI), which is sensitive to the contextual factors and behavioral functions that keep moral injury alive, may prove a useful therapeutic approach (Farnsworth et al., 2020). To enable moral healing for small groups and prevent moral injury, communities may benefit from the application of the Prosocial intervention.

10. Intervening on moral injury during COVID-19

10.1. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Moral Injury (ACT-MI) for the individual

Given the scope of the COVID-19 pandemic, treatment and prevention efforts focused on moral distress and moral injury are critical. Among those with presenting problems commonly associated with moral injury, like veterans reporting suicidal ideation and behavior (Walser et al., 2015) and individuals reporting shame associated with substance use (Luoma, Kohlenberg, Hayes, & Fletcher, 2012), ACT has demonstrated efficacy in improving psychological flexibility. ACT-MI is an application of ACT designed specifically to cultivate acceptance of moral pain in the service of one's values (Farnsworth et al., 2020).

Within ACT-MI, six core processes are targeted in treatment. To motivate behavior change associated with values and moral pain, efforts to control moral pain are explored and the workability of attempts to control these associated emotions, thoughts, sensations, and urges are discussed. Specifically, the following interventions are applied: 1) values are clarified and explored throughout treatment via bold moves; 2) bold moves are exercised as small, values-consistent, committed actions that an individual intentionally chooses as a method of exploring different areas of meaning and vitality in their life; 3) contact with the present moment is practiced creating the opportunity for direct contingencies to shape behavior; 4) defusion processes are introduced to develop the perspective of an observer of moral pain; 5) acceptance of moral pain is practiced; and 6) perspective taking through self-as-context is engaged to practice defusion related to moral-injury associated stories about the self and/or others.

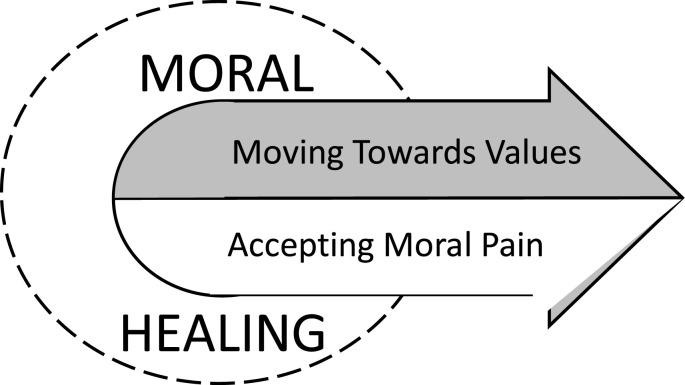

Within the ACT-MI intervention, opening to moral pain is emphasized instead of challenging the content of that pain. Acceptance may be particularly important during the COVID-19 pandemic as challenging the content of painful experiences can pathologize the often functional response of moral pain. Indeed, experiencing guilt following unintentionally infecting another with a deadly illness is a prosocial response. Moral pain signals deeply important personally held values and challenging this pain could invalidate what it represents (often a social value). As a part of changing one's relationship to moral pain, values are explored in the context of practicing acceptance of the pain that particular value evokes (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Moral healing requires both moving toward values and accepting the moral pain that arises in the presence of those values.

Once acceptance practices are introduced, the intervention involves more formally exploring self-as-context. This process is particularly important in the context of moral injury, as people often generate verbal content or stories about what their morally injurious events mean about themselves or others. Attachment to these stories often leads to identifying as a “terrible person” or as “unforgiveable.” In ACT-MI an emphasis is placed on learning to hold stories about the self and others lightly and compassionately. Clients practice perspective taking between their I/here/now experience and the you/there/then experience associated with the morally injurious event. In the context of these exercises, clients observe and describe their moral pain as it arises rather than using the story or other verbal rules to avoid contact with their present moment experiences. Learning to hold stories lightly allows clients the freedom to choose behaviors linked to values instead of remaining attached to unworkable stories. ACT-MI clients are afforded the freedom to write the next chapter of their lives, a chapter that is informed by old stories, but not defined by them. Preliminary evidence supports ACT-MI (Borges, 2019; Farnsworth et al., 2017). Additionally, the intervention is grounded in the empirical evidence demonstrating the efficacy of ACT, however research on the efficacy of ACT-MI is still needed.

In the examples that follow we demonstrate how exposure to a PMIE in the context of working in a health care system can lead to the development of moral injury in an individual medical provider and can increase the vulnerability of a small group of hospital employees to developing moral injury. Using the same PMIE, two interventions are presented to demonstrate how moral injury might be disrupted in the context of COVID-19. First, we present ACT-MI as a psychotherapy designed to treat moral injury among a single health care provider. Next, we present Prosocial as a framework to prevent the development of moral injury and to facilitate moral healing for a team of providers following exposure to PMIEs. While both of these examples are focused on health care providers for clarity in comparing the two interventions, we believe any of the examples of PMIEs presented in this paper would be relevant to address using ACT-MI and/or Prosocial.

11. Case example applying ACT-MI to moral injury-related to COVID-19

The following scenario was inspired by those reported in the media during the COVID-19 pandemic about health care providers experiencing increased exposure to traumatic and morally injurious events (e.g., Godoy, 2020 February 14). In this case example we describe an emergency room (ER) doctor working in a health care system overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients. The ER doctor was under continual pressure to discharge patients quickly to make room for the next group of critically ill individuals. She had been working relentless hours, was feeling fatigued, and depressed about the situation in her hospital. Her experience with one patient was particularly “haunting.” It was her first experience with a child testing positive for COVID-19. The patient reminded her of her own son, recalling his innocence. Although the patient tested positive, she believed his symptoms did not warrant hospitalization. As well, the hospital was overrun with COVID-19 patients and every spare room was needed. The ER doctor chose to send the patient home for quarantine and recovery. However, the child's COVID-19 symptoms quickly progressed and he returned to the ER just a few days later. The ER doctor saw the patient again, noting his worsened symptoms. She provided urgent care and had him transported to the intensive care unit (ICU) where he was placed on a ventilator. Later that evening, she was informed that the child died of multi-organ failure. Although the ER doctor had experienced many tragedies in the emergency room, including the death of children, she realized that she had not ordered any other tests once he tested positive for COVID-19. In her exhausted and overwhelmed state, she believed she missed other possible medical factors contributing to the child's death but had no time to check this story due to the frantic pace in the ER.

In this situation, the ER doctor experiences intense moral pain following this morally injurious event. She frequently experiences thoughts she has not encountered before, “I killed a child.” Her values as a doctor and mother and the context of hospital overwhelm lead her to deeply question her decision. She does not talk to anyone about her feelings and begins to feel shame about the event and disgust at the way the hospital is handling the COVID-19 pandemic.

To cope with her shame and disgust, she shuts down further and begins to avoid most of her meaningful relationships. She interacts less with her colleagues but works longer hours. When she does go home, she immediately barricades herself in the guest bedroom, telling her family she is isolating to minimize their contact with COVID-19, when in reality she is doing so because she believes she deserves to be alone and does not want to face her own child. She begins drinking more heavily while alone in the guest room. She finds herself completely buried in her thoughts related to killing an innocent child and begins contemplating suicide as a way to escape her pain. On a weekend off work when she feels particularly alone with her thoughts, she drinks heavily. Her suicidal thoughts escalate and she begins planning for suicide which scares her, leading her to finally tell her partner and seek help.

The ER doctor is referred to ACT-MI and works with a provider to discuss the factors contributing to her suicidal ideation and alcohol use during the pandemic. She identifies the PMIE she experienced and the moral pain this event caused. She works to describe all of the strategies she has used in the past in response to her moral pain and learns how these behaviors have functioned to help her avoid emotions like shame and disgust in the short-term. She begins working to find areas of meaning in her life both in her career and in her personal life discovering that she has neglected her family relationships because her son reminds her of the child in her care who died of COVID-19. She explores how she can reengage in a relationship with her son in spite of the pain that is evoked by interacting with him, realizing it places her in contact with the child who died (ACT processes: values, bold moves, acceptance). She also explores how her moral pain at work is connected to what matters to her. She learns that her pain signals that she deeply cares about doing no harm and treating all patients with thorough care. She works to re-engage more fully with her colleagues and patients as not doing so is inconsistent with her values (values, bold moves, acceptance). Her clinical interactions with child patients sometimes evoke guilt and shame, but she allows herself to experience this shame while still working (acceptance, bold moves, and values), contextualizing the shame as a signal that she cares about her job and about contributing to those that are suffering (values). She practices observing her guilt and shame in the present moment (defusion, contact with the present moment). She also practices observing her moral pain in her interactions with hospital staff, realizing the difficult circumstances they are working under. Not only does she observe her moral pain as it rises and falls (defusion, contact with present moment, acceptance), but she also practices stepping back from the stories about herself and others that the shame evokes (defusion, self-as-context). She learns that she is more than her moral pain and has the choice to live a life that is still profoundly meaningful even if her shame from the PMIE never completely dissipates.

12. Prosocial for small groups to intervene on moral injury

While we recommend that ACT-MI be implemented at the individual level for those suffering from COVID-19-related moral injury, an interventional approach influencing group behavior may be more appropriate for preventing moral injury within larger systems. Prosocial is one such approach. Prosocial was created based on Elenor Ostrom's Nobel Prize winning core design principles (Atkins et al., 2019; Ostrom, 1993; Wilson, Ostrom, & Cox, 2013). The intervention was developed for groups to grow and evolve in healthy directions using small groups as a fundamental unit of human social organization (Atkins et al., 2019). Within Prosocial, some of Ostrom's core design principles remain intact and others are adapted to emphasize the improvement of group functioning from a contextual behavioral perspective. The Prosocial principles include cultivating the following within small groups: 1) shared identity and purpose, 2) equitable distribution of contributions and benefits, 3) fair and inclusive decision making, 4) monitoring agreed behaviors, 5) graduated responding to helpful and unhelpful behavior, 6) fast and fair conflict resolution, 7) authority to self-govern (according to principles 1–6), and 8) collaborative relations with other groups (using principles 1–7) (Atkins et al., 2019). Prosocial has been shown to be an intervention that improves the cooperation of small groups (Wilson, Kaufmann, & Purdy, 2011). Given the benefits of Prosocial in facilitating group cohesion and cooperation, it appears a promising intervention to promote behavior change during the COVID-19 pandemic for the purposes of moral injury prevention.

While there has been no research explicitly examining the impact of Prosocial on moral injury, Prosocial has been shown to influence health behavior change related to the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone. Using Prosocial to reduce rates of exposure to Ebola suggests that it may be helpful in reducing exposure to PMIEs in the context of moral injury as it is plausible that higher rates of Ebola infection correspond with higher rates of exposure to PMIEs. This suggests that an intervention like Prosocial may be useful in reducing exposure to PMIEs in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. To break the chain of transmission of the Ebola virus, Prosocial was used to assess the problem associated with Ebola transmission in Sierra Leone and to facilitate behavior change in small communities. In the Bo district of Sierra Leone, cultural practices used to honor a dead loved one were increasing the deceased family's risk of contracting the virus. These practices included touching the dead family member, washing, kissing, dressing, and perfuming them. Each of these increased physical proximity to the Ebola virus. Two people trained in ACT and Prosocial including Hannah Bockarie and Beatte Ebert (Stewart et al., 2016) worked with a small group of villagers in Sierra Leone to develop a practice that honored important cultural values and traditions, while increasing safety and minimizing Ebola transmission. Instead of engaging in typical funeral preparations, banana trunks were used to honor the dead. These banana trunks were prepared like a dead body based on the villagers' funeral practices. They were wrapped, perfumed, touched, and celebrated as symbols representing the deceased relative, but minimized villager contact with the loved one's body and thus the Ebola virus (Atkins et al., 2019). Such an application of Prosocial demonstrates the power of the intervention to facilitate significant change at the level of small groups to significantly improve health related outcomes. It also suggests that moral healing is possible in a community context. While research is still needed to investigate Prosocial as an intervention for moral injury prevention, examples like this one suggest potential utility during the COVID-19 pandemic.

13. Case example applying prosocial to prevent moral injury related to COVID-19

The following scenario offers a case example of applying Prosocial to prevent moral injury in a health care system during the COVID-19 pandemic. This scenario was inspired by the call to action for hospitals to integrate triage committees into their pandemic practices to “prevent debilitating or disabling distress for some clinicians” (Truog, Mitchell, & Daley, 2020). Following the ER doctor's PMIE in the ACT-MI case example, she meets with her team to discuss the pressures she is feeling to discharge patients quickly to make room for the next group of critically ill individuals. She describes why it is important to her to keep her patients longer than hospital guidelines recommend and has requested resources that administrators are not able to provide (e.g., more ventilators). She explains the pressure she feels from administrators to discharge her patients quickly. She feels angry and distressed for being asked to compromise patient medical care due to hospital guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the context of her experience of moral injury. Other team members describe similar frustration and disillusionment with the system. She reaches out to the director of the hospital for feedback to address her concerns for her own role, to communicate concerns from her team, and to express her concern that other team members might develop moral injury from the morally injurious events she experienced or from other similar events involving tragic outcomes associated with patient care. The director says that she has just learned about a psychologist who is working to help providers manage tensions in overtaxed health care systems using an approach called Prosocial.

The doctor learns that Prosocial is about working with her team to function as a cooperative small group capable of coordinating behavior based on shared values. Prosocial training is provided to the doctor and her team including administrators, other doctors, and the nurses, respiratory therapists, and physical therapists who facilitate the most direct patient care. In the context of Prosocial (Atkins et al., 2019), team members work to explore shared values during the COVID-19 pandemic (core design principle 1). Everyone's perspective is heard regardless of their role (core design principle 2). Decisions are made about establishing triage and discharge guidelines collectively, including all group members in decisions (core design principle 3). Once triage and discharge guidelines have been established together, the team works to ensure that these new guidelines are being followed by all group members (core design principle 4). To do this, the team members learn to differentially reinforce behaviors that are contributing to cooperation and provide feedback related to those that are detracting from group functioning (core design principle 5). The group develops conflict resolution processes and procedures so that when conflict does arise between group members, a fast and fair system is in place to address this conflict (core design principle 6). Using core design principles 1 through 6, the group learns to manage themselves effectively while still working within the larger system of the hospital (core design principle 7). Administrators demonstrate willingness to allow this as long as certain metrics are still met by providers. The group learns to develop and maintain cooperative relationships with other groups within the hospital using core design principles 1 through 7 (core design principle 8). Following the development of a cooperative team, the doctor experiences a shared sense of decision making for her patients which honors her personal values. She feels less individual responsibility for each patient and is able to rely on her team and the newly established triage and discharge guidelines to make challenging decisions, causing her to experience less culpability for scenarios in which patients die from COVID-19. The Prosocial intervention ultimately reduces the team's exposure to future PMIEs, potentially decreasing the likelihood that they will go on to develop moral injury. Beyond reducing the team's exposure to future PMIEs, applying Prosocial in this way could directly address the systematic and social issues that can give rise to PMIEs and moral injury in the community. For instance, in addition to creating a triage committee, the team could develop and operate mobile screening clinics to target communities with limited access to health care resources that might be most influenced by COVID-19. This could not only help to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in these communities, but help prevent the resource strain that many hospitals are facing.

14. Conclusion

To fully address the mental health consequences associated with COVID-19, attention must be paid to moral distress and moral injury among patients, providers, and individuals suffering their effects. The conceptual model applied to COVID-19 mental health outcomes such as moral injury may prove useful. Indeed, ACT-MI and Prosocial offer tenable options for treating and preventing moral injury. While the functional contextual model of moral injury offers important recommendations for understanding and intervening on moral injury during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is of vital importance that additional research be conducted to characterize moral injury in populations outside of warzone veterans and Service Members. Investigators are called to study moral injury and its treatment to better understand the impact of moral injury and recovery among health care providers, emergency workers, COVID-19 patients, and individuals suffering related to the pandemic in the community. Research is also needed to determine the efficacy of moral injury interventions at the level of the individual (e.g., Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Moral Injury) and group (e.g., applying Prosocial to prevent the development of moral injury among small groups). Through these kinds of efforts, we can harness the power of CBS to promote mental health recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and move toward a values-consistent future together.

Footnotes

The contents of this publication are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Atkins P.W.N., Wilson D.S., Hayes S.C. Context Press; 2019. Prosocial: Using evolutionary science to build productive, equitable, and collaborative groups. [Google Scholar]

- Battles A.R., Brave A.J., Kelley M.L., White T.D., Braitman A.L., Hamrick H.C. Moral injury and PTSD as mediators of the associations between morally injurious experiences and mental health and substance use. Traumatology. 2018;24(4):246–254. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai A. 2020. ‘It feels like a war zone’: As more of them die, grocery workers increasingly fear showing up at work.https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/12/grocery-worker-fear-death coronavirus/ April 12. Washington Post. [Google Scholar]

- Borges L.M. A service member's experience of acceptance and commitment therapy for moral injury (ACT-MI): “Learning to accept my pain and injury by reconnecting with my values and starting to live a meaningful life. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2019;13:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borges L.M., Bahraini N.H., Holliman B.D., Gissen M.R., Lawson W.C., Barnes S.M. Veterans' perspectives on discussing moral injury in the context of evidence-based psychotherapies for PTSD and other VA treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2020;76(3):377–391. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges L.M., Barnes S.M., Farnsworth J.K., Bahraini N.H., Brenner L.A. A commentary on moral injury among healthcare providers during the Covid-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1037/tra0000698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan C.J., Bryan A.O., Roberge E., Leifker F.R., Rozek D.C. Moral injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicidal behavior among National Guard personnel. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2018;10(1):36–45. doi: 10.1037/tra0000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2020. COVID-19 in Racial and ethnic minority groups.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.htmlhttps://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html June 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chapalo S.D., Kerig P.K., Wainryb C. Development and validation of the moral injury scales for youth. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2019;32(3):448–458. doi: 10.1002/jts.22408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. 2020. Please don't eat your neighbor: Why what Alex Jones just said is so dangerous.https://www.forbes.com/sites/sethcohen/2020/05/02/please-dont-eat-your-neighbor--why-what-alex-jones-just-said-is-so-dangerous/#46a117df5810 May 2. [Google Scholar]

- Currier J.M., Holland J.M., Mallot J. Moral injury, meaning making, and mental health in returning veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014;71(3):229–240. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier J.M., McDermott R.C., Farnsworth J.K., Borges L.M. Temporal associations between moral injury and PTSD symptom clusters in military veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2019;32(3):382–392. doi: 10.1002/jts.22367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher & Foy When they come home: Posttraumatic stress, moral injury, and spiritual consequences for veterans. Reflective Practice: Format. Supervision Ministry. 2008;28:85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein E.G., Whitehead P.B., Prompahakul C., Thacker L.R., Hamric A.B. Enhancing understanding of moral distress: The measure of moral distress for health care professionals. AJOB Empirical Bioethics. 2019;10(2):113–124. doi: 10.1080/23294515.2019.1586008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans W.R., Walser R.D., Drescher K.D., Farnsworth J.K. New Harbinger Publications; 2020. The moral injury workbook: Acceptance and commitment Therapy skills for moving beyond shame, anger, and trauma to reclaim your values. [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth J.K., Drescher K.D., Evans W., Walser R.D. A functional approach to understanding and treating military-related moral injury. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2017;6(4):391–397. [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth J.K., Drescher K.D., Nieuwsma J.A., Walser R.D., Currier J.M. The role of moral emotions in military trauma: Implications for the study and treatment of moral injury. Review of General Psychology. 2014;18(4):249–262. [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth J.K., Borges L.M., Drescher K.D., Walser R.D. 2020. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for the treatment of moral injury (ACT-MI) [Google Scholar]

- Follette W.C., Houts A.C. Models of scientific progress and the role of theory in taxonomy development: A case study of the DSM. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(6):1120–1132. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.6.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy M. National Public Radio; 2020. How COVID-19 kills: The new coronavirus Disease can take a deadly turn.https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/02/14/805289669/how-covid-19-kills-the-new-coronavirus-disease-can-take-a-deadly-turnhttps://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/02/14/805289669/how-covid-19-kills-the-new-coronavirus-disease-can-take-a-deadly-turn February 14. [Google Scholar]

- Hamaideh S.H. Moral distress and its correlates among mental health nurses in Jordan. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2014;23(1):33–41. doi: 10.1111/inm.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C., Wilson K.W., Gifford E.V., Follette V.M., Strosahl K. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(4):1152–1168. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M.M., Sultana A., Purohit N. 2020. Mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for infection prevention: A systematic umbrella review of the global evidence. Available at: SSRN 3561265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameton A. Dilemmas of moral distress: Moral responsibility and nursing practice. AWHONNS Clinical Issues in Perinatal & Womens Health Nursing. 1993;4(4):542–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M., Dickerson C. 2020. Poultry worker's death highlights spread of coronavirus in meat plants. April 9. (New York Times) [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D., Van Kleef, Chen S., Kraus M.W. A reciprocal influence model of social power: Emerging principles and lines of inquiry. Advanced in Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;40:151–192. [Google Scholar]

- Lamiani G., Borghi L., Argentero P. When healthcare professionals cannot do the right thing: A systematic review of moral distress and its correlates. Journal of Health Psychology. 2017;22(1):51–67. doi: 10.1177/1359105315595120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz B.T., Stein N., Delaney E., Lebowitz L., Nash W.P., Silva C. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(8):695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma J.B., Kohlenberg B.S., Hayes S.C., Fletcher L. Slow and steady wins the race: A randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy tar- geting shame in substance use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(1):43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0026070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak I.W.C., Chu C.M., Pan P.C., Yiu M.G.C., Chan V.L. Long-term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31(4):318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitton C., Peacock S., Storch J., Smith N., Cornelissen E. Moral distress among healthcare managers: Conditions, consequences and potential responses. Healthcare Policy. 2010;6(2):99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musto L., Schreiber R.S. Doing the best I can do: Moral distress in adolescent mental health nursing. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2012;33(3):137–144. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.641069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y., Gastmans C. Moral distress experienced by nurses: A quantitative literature review. Nursing Ethics. 2015;22(1):15–31. doi: 10.1177/0969733013502803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi K., Ohgushi Y., Nakano M., Fujii H., Tanaka H., Kitaoka K. Moral distress experienced by psychiatric nurses in Japan. Nursing Ethics. 2010;17:726–740. doi: 10.1177/0969733010379178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom E. Design principles in long-enduring irrigation institutions. Water Resources Research. 1993;29(7):1907–1912. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell N., Koenig C.J., Bosch J., Maguen S. Veterans' perspectives on the psychosocial impact of killing in war. The Counseling Psychologist. 2016;44(7):1062–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Saslow E. Voices from the pandemic: It was me. I know it was me. 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/05/30/coronavirus-daughter-to-mother-contagion/?arc404=true May 30.

- Schuppe J. NBC news; 2020. ‘I gave this to my dad’: COVID-19 survivors grapple with guilt of infecting family.https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/i-gave-my-dad-covid-19-survivors-grapple-guilt-infecting-n1207921 May 16. [Google Scholar]

- Shay J. Achilles in Vietnam: Combat trauma and the undoing of character. Scribner. 1994:20. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz S.E., Gray M.J., Clapp J.D. Development and evaluation of the perpetration-induced distress scale for measuring shame and guilt in civilian populations. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2019;32(3):437–447. doi: 10.1002/jts.22377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C., White R.G., Ebert B., Mays I., Nardozzi J., Bockarie H. A preliminary evaluation of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) training in Sierra Leone. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2016;5:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Truog R.D., Mitchell C., Daley G.Q. The toughest triage-Allocating ventilators in the pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kleef G.A. How emotions regulate social life: The emotions as social information (EASI) model. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Walser R.D., Garvert D.W., Karlin B.E., Trockel M., Ryu D.M., Taylor C.B. Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy in treating depression and suicidal ideation in veterans. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2015;74:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins A., Rothfeld M., Rasbaum W.K., Resnthal B.M. Top E.R. doctor who treated virus patients dies by suicide. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/27/nyregion/new-york-city-doctor-suicide-coronavirus.html April 27. New York Times.

- Whitehead P.B., Herbertson R.K., Hamric A.B., Epstein E.G., Fisher J.M. Moral distress among healthcare professionals: Report of an institution-wide survey. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2015;47(2):117–125. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D.S., Hayes S.C., Biglan A., Embry D.D. Evolving the future: Toward a science of intentional change. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2014;37:395–460. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X13001593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D.S., Kauffman R.A., Purdy M.S. A program for at-risk high school students informed by evolutionary science. PloS One. 2011;6(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D.S., Ostrom E., Cox M.E. Generalizing the core design principles for the efficacy of groups. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 2013;90(supplement):S21–S32. [Google Scholar]