Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected residents and staff at long-term care (LTC) and other residential facilities in the United States. The high morbidity and mortality at these facilities has been attributed to a combination of a particularly vulnerable population and a lack of resources to mitigate the risk. During the first wave of the pandemic, the federal and state governments received urgent calls for help from LTC and residential care facilities; between March and early June of 2020, policymakers responded with dozens of regulatory and policy changes. In this article, we provide an overview of these responses by first summarizing federal regulatory changes and then reviewing state-level executive orders. The policy and regulatory changes implemented at the federal and state levels can be categorized into the following 4 classes: (1) preventing virus transmission, which includes policies relating to visitation restrictions, personal protective equipment guidance, and testing requirements; (2) expanding facilities' capacities, which includes both the expansion of physical space for isolation purposes and the expansion of workforce to combat COVID-19; (3) relaxing administrative requirements, which includes measures enacted to shift the attention of caretakers and administrators from administrative requirements to residents' care; and (4) reporting COVID-19 data, which includes the reporting of cases and deaths to residents, families, and administrative bodies (such as state health departments). These policies represent a snapshot of the initial efforts to mitigate damage inflicted by the pandemic. Looking ahead, empirical evaluation of the consequences of these policies—including potential unintended effects—is urgently needed. The recent availability of publicly reported COVID-19 LTC data can be used to inform the development of evidence-based regulations, though there are concerns of reporting inaccuracies. Importantly, these data should also be used to systematically identify hot spots and help direct resources to struggling facilities.

Keywords: COVID-19, nursing homes, long-term care, CMS policies, executive orders

The COVID-19 pandemic has surfaced many of the ways in which our health care system fails to protect vulnerable older adults and their caregivers. Residents and staff of nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and other long-term care (LTC) facilities have contracted the disease at high rates; although nursing home residents comprise less than 1% of the US population, they account for more than 40% of COVID-19 deaths.1 In addition to a vulnerable patient population, the high morbidity and mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in LTC facilities has been attributed to poor access to personal protective equipment (PPE), staffing shortages, and poor infection control practices.2 During the first wave of the pandemic, federal and state governments responded to urgent calls for help from facilities with several policies and regulatory changes. Understanding those changes is an integral first step toward developing a comprehensive policy framework to address the LTC needs of older adults and their caregivers. In this piece, we review federal and state regulations implemented between March 4 and June 12, place those in the context of existing empirical evidence, and make recommendations for the future.

Federal Response

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has allowed numerous flexibilities, provided recommendations, and eased regulations for LTC facilities in response to the pandemic. We classified CMS COVID-19 regulatory responses into the following 4 categories and provide an overview of each below: preventing virus transmission, expanding facilities' capacities, relaxing administrative requirements, and reporting COVID-19 data.

Preventing Virus Transmission

After the first positive COVID-19 case at a nursing home was reported in Kirkland, Washington on February 28, 2020, CMS issued guidance on limiting the transmission of the coronavirus in these facilities. By March 13, federal recommendations included restricting all nonessential visitors, canceling communal dining and group activities, implementing active screening of residents and staff for symptoms (staff should be screened at the start of each shift), and using PPE according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.3 Additionally, CMS suspended routine inspections of LTC facilities (including inspections of medical equipment), instead prioritizing inspections that are most critical for infection control.4 On June 1, CMS tied these infection control results to federal funding through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act; states with facilities that fail to perform infection control surveys face CARES Act allocation reductions.5

Expanding Facilities' Capacities

CMS put forth numerous regulatory waivers to expand both the physical capacity and the workforce available to combat COVID-19.6 To increase capacity to isolate long-term residents and relieve acute hospital bed shortage, non-nursing facilities can temporarily be certified for use as nursing homes. Additionally, LTC facilities can transfer residents to other locations without a formal discharge, thus enabling facilities to place affected residents in separate locations from those who test negative.

Training and certification requirements have been modified to bolster the workforce available to care for LTC residents. Nurse aides can now postpone the deadline for completing a required 12-hour annual training until COVID-19 is no longer deemed a public health emergency. Physicians have more leeway to delegate tasks—including physician visits—to other licensed staff members (such as nurse practitioners). Minimum training hours for paid feeding assistants have been reduced from 8 to 1. Of note, physician visits are still required to occur at the same frequency as before and feeding assistants still must work under the supervision of a registered nurse or licensed practical nurse.

Relaxing Administrative Requirements

Several flexibilities implemented by CMS provide relief from billing and documentation requirements. These include waiving the 3-day hospitalization requirement for Medicare coverage of post-acute care in a nursing home, relaxing requirements for LTC facilities to submit data on facility staffing, and suspending requirements for preadmission assessments at nursing homes. CMS has also advised its billing contractors to allow extensions for filing appeals and to relax requirements relating to timeliness and completion of requests for appeals.

Reporting COVID-19 Data

On April 19, CMS began requiring nursing homes to report COVID-19–positive cases and deaths to residents, families, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on a weekly basis; these data were published on Nursing Home Compare on June 4.

State-Level Responses

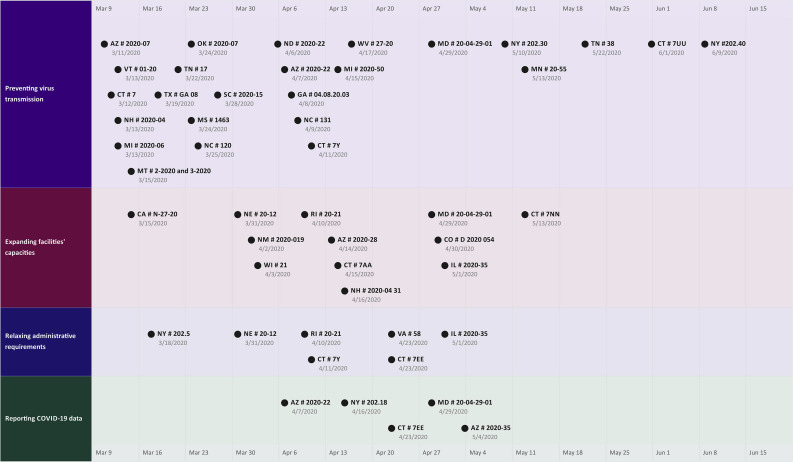

We used Executive Orders compiled by the Council of State Governments, a nonpartisan organization that serves as a resource for state governments, to identify state-level policy changes.7 As of June 12, 25 state governors collectively issued nearly 50 executive orders relating to the prevention of COVID-19 transmission among residential and LTC facilities (Figure 1 ). Executive orders are policy tools used by state governors without direct involvement of the legislative or judicial branches; as such, they allow for swift policy responses to public health problems that demand immediate attention.8 We focused this summary of state-level policy changes on executive orders, though such orders alone likely do not capture all state initiatives in response to COVID-19 (eg, orders from departments of health, governor proclamations, and emergency orders were excluded). We limited policies to those that specifically addressed concerns of LTC and other residential facilities (such as assisted living facilities); as such, changes concerning health care settings at large (such as hospitals and outpatient care) were not included. Executive order numbers are provided in parentheses for reference.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of COVID-19 state executive orders relating to LTC, nursing, and other residential facilities. State-level executive order numbers are plotted by date and policy category. Each data point includes the state abbreviation, the executive order number, and the date the order was signed. Policies were identified using orders compiled by the Council of State Governments at https://web.csg.org/covid19/executive-orders/.

Preventing Virus Transmission

Beginning in mid-March, 14 state governors released orders∗ that restricted visitation at facilities; nearly all involved complete bans on nonessential visitors. In addition, Arizona required separation of residents at nursing care and residential care facilities based on COVID-19 status (#2020-22), North Carolina required LTC facilities to regularly screen staff for symptoms (#131), Michigan required all employees of LTC facilities who test positive or display COVID-19 symptoms to remain home (#2020-50), Connecticut designated specific nursing facilities as COVID-19 Recovery Facilities (#7Y), and Minnesota prioritized distribution of PPE to support at-risk populations and staff, including those at nursing homes (#20-55). North Carolina and Michigan also canceled all communal dining.

Executive orders released more recently have focused heavily on testing and virus detection. Maryland required increased testing of residents and staff at nursing homes, as well as a daily evaluation of each resident for COVID-19 symptoms (#20-04-29-01); New York required nursing homes and assisted living residences to test all personnel twice per week (#202.30; subsequently revised down to once per week for some facilities via Executive Order #202.40); and Connecticut mandated COVID-19 testing for all staff at nursing homes, residential communities, and assisted living facilities (#7UU).

Expanding Facilities' Capacities

Between mid-March and mid-May, 7 states issued executive orders† to expand the workforce available for patient care at LTC and residential care facilities. Most of these included waivers of staff training requirements and flexibilities in certification. Rhode Island authorized “disaster response workers” to provide services without a license at facilities including nursing homes (#20-21). Three states (Nebraska, Rhode Island, and Connecticut) issued orders that expanded the physical space available to facilities for isolation of COVID-19–positive residents by waiving requirements relating to new construction (such as approval of plans and inspections) for assisted living facilities (NE #20-12), expanding alternative nursing care sites to serve as COVID-19 recovery facilities (RI #20-21), and adding nursing beds for COVID-19 patients at designated recovery facilities (CT #7AA). Other states increased resources by apportioning additional funds to nursing homes to provide disaster relief: New Mexico allocated up to $750,000 to the Aging and Long-Term Services Department (NM #2020-019), Colorado increased funding to Medicaid-certified nursing facilities and intermediate nursing facilities (CO #D 2020 054), Connecticut directed CARES Act funding towards nursing homes (CT #7NN), and New Hampshire provided temporary stabilization funding (about $300/week) to incentivize frontline LTC workers (NH 2020-04 #31). Some states have also used mechanisms that were not executive orders to increase LTC and residential facilities' funding,9 but these orders were beyond the scope of this article.

Relaxing Administrative Requirements

Six states issued executive orders‡ that eased administrative burden. New York relaxed requirements for mandatory comprehensive assessments of residents on admission to nursing homes (#202.5); these assessments are typically conducted to evaluate residents' functional capacity and to develop an individualized plan of care. Similarly, Virginia suspended preadmission screening requirements (#58). Three states eased licensing requirements (NE #20-12, RI #20-21, and IL #2020-35). Connecticut does not require designated COVID Recovery Facilities to notify residents of discharge or provide a discharge plan (#7Y).

Reporting COVID-19 Data

Four states ordered facilities to report COVID-19 cases and deaths prior to CMS's mandate on April 19.§ Arizona requires nursing home and residential care facilities to report within 24 hours of confirming COVID-19 cases and deaths (#2020-35), and Connecticut's residential care facilities are subject to civil penalties for failure to comply with mandatory reporting (#7EE).

Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research

These policies represent a snapshot of the initial efforts to mitigate the damage to LTC and residential facilities inflicted by the pandemic. As this wave of COVID-19 infections subsides, there is an opportunity for evidence-based long-term policy development (Table 1 provides a summary of recommendations.) Empirical evaluation of the consequences of these policies, including potential unintended effects, is urgently needed. For example, despite the efforts to improve resident access to providers via telemedicine or to relax scope of practice regulations, COVID-era distancing policies may limit residents' access to necessary caregivers and advocates. This could put residents at higher risk for other adverse outcomes, as previous work has shown that patients in skilled nursing facilities without physician or advanced practitioner visits were at higher risk for both hospital readmission and death.10 Also, close proximity to visitors is associated with positive nursing home resident behaviors, such as smiling and alertness.11 Containment measures are a necessary step to prevent transmission, but many patients caught in the fray of involuntary transfers and visitation restrictions may incur considerable harm that they may deem worse than COVID-19.

Table 1.

Recommendations for Practice, Policy, and Research

|

Paralleling ongoing policy evaluation, state and federal administrations should also use the COVID-19 nursing home data to systematically identify and help facilities that are struggling. Given that the current crisis compounds already-existing disparities in nursing home resource distribution, waiving requirements is not enough. States need to develop an infrastructure for continuous monitoring of nursing home cases, providing immediate assistance to facilities facing an outbreak; such support could come in the form of health care personnel, sick leave for overworked frontline workers, additional equipment, isolation spaces, training, and increased Medicaid payments. Similar efforts could be extended to other residential facilities, such as assisted living facilities.

The rapidly changing policy landscape may allow for the shedding of outdated rules. Prior work has shown that the 3-day hospital stay requirement for a Medicare enrollee to qualify for coverage at a skilled nursing facility care may unnecessarily extend hospital stays.12 COVID-19 prompted CMS to temporarily waive this requirement; making this change permanent may have a beneficial impact on the quality and efficiency of care. Similarly, the next wave of policies and regulations could support those aspects of nursing home and residential care practice that are associated with better patient outcomes. For example, prior evidence supports the use of advanced practitioners in nursing homes,13 as well as physicians who specialize in nursing home practice.14

We also need to understand the effects of public reporting of COVID-19 cases and deaths, as well as COVID-related funding penalties, on the quality of and access to nursing home and residential care—including facility closures. Fiscally vulnerable facilities—facilities that mainly house Medicaid residents, operate on narrow financial margins, and have limited resources—may be disproportionally affected by the recently issued CMS penalties for infection control lapses.15 These facilities already have a depleted workforce with high turnover rates, have more health-related deficiencies, are disproportionately located in the poorest counties, and are more likely to serve minority populations.16 Performance-based funding may be well-intentioned but could exacerbate disparities by putting these facilities at even greater risk of financial insolvency. This may lead to deteriorating care quality or, if facilities close, many residents will lose their homes.

The recent release of nationwide COVID-19 data on Nursing Home Compare provides an opportunity to evaluate COVID-era policy changes, but care must be taken when using these data. Prior evidence from Nursing Home Compare has shown that public reporting of data may be inaccurate, and that the public often distrusts publicly reported information.17 Prior studies have already highlighted the difficulty of differentiating between a lack of resources and subpar performance as a reason for poor outcomes; in a recent analysis, infection control violations were not associated with COVID-related morbidity or mortality in nursing homes.18 Researchers should also account for the unique aspects of studying virus transmission among LTC populations19 and appreciate that findings—especially those under the COVID-19 spotlight—may cause unnecessary panic, transfers, and admissions that are particularly harmful to older patients.20 Although care must be taken, evidence-based reform of nursing homes can address the existing vulnerabilities of health care providers while maintaining patient and caregiver access to the residential care that so many people rely on.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely acknowledge Ms. Hannah Wang (Jerome Fisher Program in Management and Technology at the Wharton School) for assistance with policy review and proofreading the manuscript.

Footnotes

A.T.C. and K.L.R. share equal first-coauthorship.

Dr Ryskina's work on this study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Career Development Award (K08-AG052572). Dr Jung is the recipient of a Mentored Research Scientist Development Award from the National Institute of Aging (K01AG057824).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AZ #2020-07, VT #01-20, CT #7, NH #2020-04, MI #2020-06, MT #2-2020 and 3-2020, TX #GA 08, TN #17, MS #1463, OK #2020-07, NC #120, SC #2020-15, ND #2020-22, GA #04.08.20.03.

CA #27-20, NE #20-12, WI #21, RI #20-21, AZ #2020-28, MD #20-04-29-01, IL #2020-35.

NY #202.5, NE #20-12, RI #20-21, CT #7Y and 7EE, VA #58, IL #2020-35.

AZ #2020-22 and #2020-35, NY #202.18, CT #7EE, MD #20-04-29-01.

References

- 1.Girvan G., Roy A. Nursing homes & assisted living facilities account for 42% of COVID-19 deaths. https://freopp.org/the-covid-19-nursing-home-crisis-by-the-numbers-3a47433c3f70 Available at:

- 2.Abbasi J. “Abandoned” nursing homes continue to face critical supply and staff shortages as COVID-19 toll has mounted. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10419. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Guidance for infection control and prevention of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in nursing homes (revised) https://www.cms.gov/files/document/qso-20-14-nh-revised.pdf Available at:

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Prioritization of survey activities. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/qso-20-20-allpdf.pdf Available at:

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services COVID-19 Survey Activities, CARES Act funding, enhanced enforcement for infection control deficiencies, and quality improvement activities in nursing homes. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/qso-20-31-all.pdf Available at:

- 6.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Long term care facilities (skilled nursing facilities and/or nursing facilities): CMS flexibilities to fight COVID-19. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-long-term-care-facilities.pdf Available at:

- 7.The Council of State Governments Executive orders. https://web.csg.org/covid19/executive-orders/ Available at:

- 8.Gakh M., Vernick J.S., Rutkow L. Using gubernatorial executive orders to advance public health. Public Health Rep. 2013;128:127–130. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Office of Governor Ned Lamont Governor Lamont expands financial aid for Connecticut's nursing homes amid COVID-19 pandemic, announces nursing home site visits to extend additional support from state. https://portal.ct.gov/Office-of-the-Governor/News/Press-Releases/2020/04-2020/Governor-Lamont-Expands-Financial-Aid-for-Connecticuts-Nursing-Homes Available at:

- 10.Ryskina K.L., Yuan Y., Teng S., Burke R. Assessing first visits by physicians to Medicare patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:528–536. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendy H.M. Effects of pet and/or people visits on nursing home residents. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1987;25:279–291. doi: 10.2190/D3DD-VB2N-UQJ8-8AGN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grebla R.C., Keohane L., Lee Y. Waiving the three-day rule: Admissions and length-of-stay at hospitals and skilled nursing facilities did not increase. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:1324–1330. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shield R., Rosenthal M., Wetle T. Medical staff involvement in nursing homes: Development of a conceptual model and research agenda. J Appl Gerontol. 2014;33:75–96. doi: 10.1177/0733464812463432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryskina K.L., Yuan Y., Werner R.M. Postacute care outcomes and Medicare payments for patients treated by physicians and advanced practitioners who specialize in nursing home practice. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:564–574. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unruh M.A., Yun H., Zhang Y. Nursing home characteristics associated with COVID-19 deaths in Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:1001–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mor V., Zinn J., Angelelli J. Driven to tiers: Socioeconomic and racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care. Milbank Q. 2004;82:227–256. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geng F., Stevenson D.G., Grabowski D.C. Daily nursing home staffing levels highly variable, often below CMS expectations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:1095–1100. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abrams H.R., Loomer L., Gandhi A., Grabowski D.C. Characteristics of U.S. nursing homes with COVID-19 cases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1653–1656. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pillemer K., Subramanian L., Hupert N. The importance of long-term care populations in models of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9540. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Covinsky K.E., Pierluissi E., Johnston C.B. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I'm not sure”. JAMA. 2011;306:1782–1793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]