The entire clinical spectrum of COVID-19 is not limited to pulmonary manifestations. Recently, neurological complications associated with COVID-19 were increasingly reported giving evidence that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has a potential for central nervous system (CNS) invasion. Manifestations have included ischemic stroke, Guillain-Barré syndrome, meningitis and encephalitis [1], [2], [3]. To the best of our knowledge, COVID-19 presenting with mild encephalitis with reversible splenial corpus callosum lesion (MERS) has not been previously reported.

A 60-year-old man, with a medical history of dyslipidemia, presented to the Emergency Department with cough, headaches and short loss of consciousness lasting 4 minutes. He was afebrile and had bibasilar rales. His oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. Neurological examination was normal. Laboratory tests showed normal white blood cell (WBC) count, lymphopenia at 700 per mm3, 0 eosinophils per mm3, normal hemoglobin (Hb) and platelet count. C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration was at 4 mg/l. Procalcitonin value was 0.02 ng/ml. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed normal protein level 0.49 g/L (N:0.2–0.55), glucose 0.55 g/L (N: 0.45–0.75) and 1 white cell per mm3. CSF culture was sterile. Computed tomographic (CT) imaging of the brain was normal. Neither nasal swab nor chest CT imaging were performed. The patient was discharged with symptomatic treatment. Nine days later, he was referred to our Department of Internal Medicine for vertigo, persistence of headaches and intermittent disturbance of consciousness. He suffered from myalgia, loss of appetite and tiredness. He remained afebrile with bibasilar rales, normal oxygen saturation on ambient air and stable hemodynamic parameters. His Glasgow coma scale (GCS) was 15. Neuropsychiatric examination showed psychomotor slowing, good orientation in time and space with appropriate verbal responses and a vestibular syndrome. He had no neck stiffness. On day 1, he had a brief episode of consciousness loss. Electroencephalogram revealed slow oscillations without epileptiform features. Laboratory examination showed lymphopenia at 900 per mm3, 0 eosinophils per mm3, elevated CRP and serum ferritin levels at 50 mg/L and 703 ng/ml respectively. Protein electrophoresis showed hypoalbuminemia at 26.9 g/L, and elevated α2 globulin at 15.5 g/L. Investigations for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus, influenza A and B, antinuclear and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. Oropharyngeal swab was negative for SARS-CoV-2 on reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) assay but serologic analysis for COVID-19 was subsequently positive. The test used was ELISA SARS-CoV-2 (EUROIMMUN 2606-9601 G) revealing high serum level of IgG antibodies at 18.9 U (the test is considered as positive if IgG levels > 1.1 U).

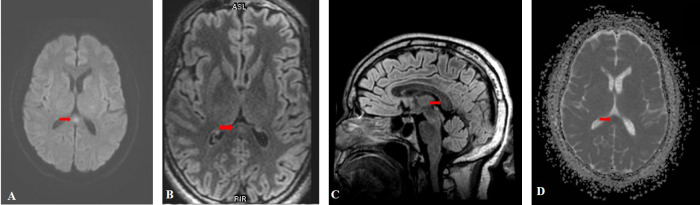

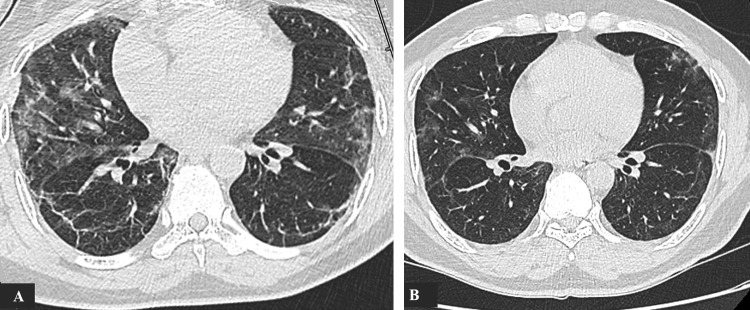

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a focal hyperintense signal in the splenium of the corpus callosum (SCC) on T2-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and diffusion weighted images (DWI). This lesion had a low ADC value and no contrast enhancement (Fig. 1 A,B,C,D). All cerebral arteries were permeable on magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). Lung CT imaging showed typical features of COVID-19 with ground-glass opacities, consolidations and crazy paving pattern with moderate lesions extent at 26% (Fig. 2 A).

Fig. 1.

Initial MRI imaging showing an hyperintense signal in the SCC on DWI (A) and T2-FLAIR images (B, C) with reduced ADC value (D).

Fig. 2.

Lung CT showing ground-glass opacities with basal consolidations (A). One month later, lesions have partially regressed (B).

The patient was treated with analgesic drugs and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for 6 days. We did not start antiepileptic drugs due to the absence of seizure evidence. On day 6, psychomotor impairment and myalgia had gradually improved, vertigo and headaches had completely recovered. Unconsciousness disturbance, seizures and focal signs did not occur during several weeks of follow-up. One month after disease onset, a follow-up imaging showed complete disappearance of SCC abnormal signal on the brain MRI and reduced pulmonary lesions on the chest CT (Fig. 2 B).

MERS is a rare clinico-radiological syndrome that was first described by Tada et al. [4] in 2004. Its spectrum comprises type 1 with an isolated lesion in the SCC and type 2 with bilateral extension in the subcortical white matter and/or entire corpus callosum [5]. The specific pathogenesis of this syndrome is still unknown. Nevertheless, reversible DWI signals associated with reduced ADC suggest that cerebral cytotoxic edema probably due to cytokine release might be the underlying causative mechanism of this condition [6]. MERS usually develops in children and young adults [6]. The most described neurological features of MERS are agitation, disorientation, delirious behavior, seizures and consciousness disturbance [6], [7]. Dong K et al. reported a case of MERS presenting with transient ischemic attack (TIA)-like symptoms including paroxysmal limb weakness, slurred speech, and bucking which completely resolved without any medication [8]. Our patient had brief episodes of consciousness loss. He had no other clinical symptoms suggestive of seizure. Additionally, the electroencephalogram provided no evidence of epileptiform features. Neither delirious behavior nor cognitive function impairment were found at neuropsychiatric examination. The hypothesis of brief TIA-like episodes is still probable.

Acute infections are the most common etiologies of MERS including Epstein Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, herpes virus, influenza A and B, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Salmonella enteritidis [6]. It can also be caused by withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs, metabolic disorders and poisoning [7]. Zhu Y et al. [6] reported 15 cases of MERS. The therapeutic regimens included acyclovir for 11 patients, corticosteroids for six patients and antiepileptic drugs for two patients. Intravenous immunoglobulin was prescribed for three critically ill patients presenting consciousness disturbance, headache, meningeal irritation (2 cases) and seizures (2 cases) with severe neurological sequelae in two cases. Thirteen patients had complete recovery within 1 month.

No special medication was given for our patient except for antibiotics to prevent bacterial superinfection with complete recovery and favorable outcome.

Our case report illustrates a MERS type1 complicating COVID-19 infection and demonstrates that this virus must be added to the list of various causes associated with MERS. The pathogenic mechanism of corpus callosum lesions during this infection remains unclear. Recently, immune mediated injury due to cytokine storm and excessive inflammatory response has been suggested as a possible mechanism of COVID-19 neurological damages [2].

Our patient had simultaneous occurrence of neurological lesions and suggestive pulmonary clinical and CT features for COVID-19 with negative nasal swab. Although RT-PCR remains the molecular test of choice for identifying acute infection, serological assays can be also useful for confirming the diagnosis of COVID-19 if it is performed within the correct timeframe after disease onset [9], [10].

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for the publication of this article.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Financial support and industry affiliation

None.

References

- 1.Mao L., Jin H., Wang M. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad I., Rathore F.A. Neurological manifestations and complications of COVID-19: a literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.017. S0967-5868(20)31078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montalvan V., Lee J., Bueso T. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 and other coronavirus infections: a systematic review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;194:105921. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tada H., Takanashi J., Barkovich A.J. Clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion. Neurology. 2004;63(10):1854–1858. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000144274.12174.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takanashi J., Imamura A., Hayakawa F., Terada H. Differences in the time course of splenial and white matter lesions in clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) J Neurol Sci. 2010;292(1–2):24–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu Y., Zheng J., Zhang L. Reversible splenial lesion syndrome associated with encephalitis/encephalopathy presenting with great clinical heterogeneity. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:49. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0572-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang S., Ma Y., Feng J. Clinicoradiological spectrum of reversible splenial lesion syndrome (RESLES) in adults: a retrospective study of a rare entity. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(6):e512. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong K., Zhang Q., Ding J., Ren L., Zhang Z., Wu L. Mild encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion mimicking transient ischemic attack: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(44):e5258. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winter A.K., Hegde S.T. The important role of serology for COVID-19 control. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30322-4. S1473-3099(20)30322-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang Y.W., Schmitz J.E., Persing D.H., Stratton C.W. Laboratory diagnosis of COVID-19: current issues and challenges. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(6):e00512–e520. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00512-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]