Abstract

HIV-1 is dependent upon cellular proteins to mediate the many processes required for viral replication. One such protein, PACS1, functions to localize Furin to the trans-Golgi network where Furin cleaves HIV-1 gp160 Envelope into gp41 and gp120. We show here that PACS1 also shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm, associates with the viral Rev protein and its cofactor CRM1, and contributes to nuclear export of viral transcripts. PACS1 appears specific to the Rev-CRM1 pathway and not other retroviral RNA export pathways. Over-expression of PACS1 increases nuclear export of unspliced viral RNA and significantly increases p24 expression in HIV-1-infected Jurkat CD4+ T cells. SiRNA depletion and over-expression experiments suggest that PACS1 may promote trafficking of HIV-1 GagPol RNA to a pathway distinct from that of translation on polyribosomes.

Introduction.

The HIV-1 replication cycle is dependent upon cellular co-factors to mediate the various steps in the viral life cycle. A meta-analysis concluded that over 2,000 cellular proteins likely have a role in the HIV-1 replication cycle (Bushman, Lewinski et al., 2005). The identification of co-factors and their mechanisms of action can provide broad insight into both HIV-1 and key cellular processes that are targeted by the virus. This is especially true for the HIV-1 Rev protein – studies of Rev and its co-factors have provided important insight into export of RNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and how HIV-1 hijacks the RNA export pathway to enhance its own replication (Cullen, 2003).

Rev activates the nuclear export of incompletely spliced viral RNAs. To achieve this, Rev contains an RNA-binding domain that interacts directly with a structured RNA element, the Rev-Response Element (RRE), present in unspliced and singly spliced viral transcripts. Rev also contains a nuclear export signal that binds to a nuclear export factor termed CRM1 (XPO1) (Shida, 2012;Fernandes, Booth et al., 2016). The Rev-CRM1-HIV-1 RNA complex, along with the co-factor Ran-GTP, accesses an export pathway used by cellular proteins, rRNA, snRNAs, and a subset of cellular mRNAs (Sloan, Gleizes et al., 2016).

We previously mined a human nuclear complexome database – the set of protein complexes in the nucleus of HeLa cells (Malovannaya, Lanz et al., 2011) – to identify RBM14 as a CRM1-associated protein that functions as a Rev co-factor (Budhiraja, Liu et al., 2015). In our analysis of the human nuclear complexome, we also identified PACS1 (Phosphofurin Acid Cluster Sorting protein 1) as a CRM1-associated protein. We found that siRNA depletion of PACS1 reduced Rev activation of a reporter plasmid, suggesting that PACS1 is a Rev co-factor.

PACS1 has previously been found to function in HIV-1 replication. PACS1 mediates localization of the protease Furin to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) where it cleaves the viral gp160 Envelope protein into gp41 and gp120 (Wan, Molloy et al., 1998;Hallenberger, Bosch et al., 1992). Additionally, PACS1 has been reported to bind to the viral Nef protein and this has been proposed to contribute to down-regulation of MHC class I during infection (Piguet, Wan et al., 2000;Blagoveshchenskaya, Thomas et al., 2002;Dikeakos, Thomas et al., 2012). Although PACS1 is predominantly a cytoplasmic protein (Dikeakos, Thomas et al., 2012), a PACS1-GFP fusion protein accumulates in the nucleus when the CRM1 nuclear export pathway is inhibited with Leptomycin B (Atkins, Thomas et al., 2014). This observation indicates that PACS1 may shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm, a property consistent with a role as a Rev co-factor.

In this study, we confirm that PACS1 shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm and show that it can be co-immunoprecipitated with CRM1 and Rev. SiRNA depletion experiments indicate that PACS1 is specific for the CRM-Rev-RRE nuclear export pathway and not the CRM1 export pathway of the Rem protein of Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus (MMTV) or the Constitutive Transport Element (CTE) export pathway of Mason-Pfizer Monkey Virus (MPMV). We observed that over-expression of PACS1 increases the level of cytoplasmic unspliced HIV-1 RNA and appears to direct this RNA to a pathway distinct from that of translation on polyribosomes. Additionally, we observed that over-expression of PACS1 in Jurkat CD4+ T cells significantly enhances HIV-1 p24 expression during HIV-1 infection. Thus, our data indicate that in addition to its roles in Furin localization to the TGN and down-regulation of MHC class I by Nef, PACS1 has an additional distinct role in HIV-1 replication– as a Rev co-factor.

Materials and Methods.

Plasmids, siRNAs, and antibodies.

The PACS1-HA plasmid was provided by Dr. Gary Thomas (University of Pittsburg). The PACS1-HA sequences were inserted into the MLV-based vector pBabe (provided by Dr. Richard Sutton, Yale University). The pCMVGagPol-RRE and pCMV-RevFlag plasmids were provided by Dr. Marie-Louise Hammarskjöld (University of Virginia). The Flag-Vpr plasmid was constructed by PCR amplification of the NL4-3 Vpr gene and insertion into a CMV-Flag expression plasmid. The influenza virus Flag-NS1 plasmid contains a mutation in the NS1 binding site to CPSF30 to increase NS1 protein expression (Golebiewski, Liu et al., 2011). The pHMRLuc (Renilla) and Rem-GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein) plasmids were provided by Dr. Jaquelin Dudley (University of Texas). PACS1 (sc-106348) and control (sc 37007) small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. PACS1 antiserum (ab56072) was from Abcam; anti-HA antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-7392); anti-CRM1 antibody (ST1100) and Flag antibody (F1804) were from Millipore and Sigma-Aldrich, respectively.

Generation of PACS1-HA cell lines and cell pools.

To generate cell lines and cell pools that over-express PACS1, a PACS1 cDNA with an HA tag at the carboxyl terminus was inserted into the MLV pBABE vector which contains a puromycin selectable marker. Cultures of either 293T or Jurkat CD4+ T cells were transduced with the MLV pBABE- PACS1-HA retrovirus and subjected to puromycin selection followed by limiting dilution was used to generate clonal cell lines. Jurkat clonal lines were found to rarely sustain expression of PACS1-HA. We therefore generated pools of Jurkat cells that were transduced with the MLV pBABE- PACS1-HA retrovirus and subjected to selection with puromycin. Flow cytometry was used to identify PACS1-HA+ cells in the Jurkat pools.

Transfections.

For siRNA depletions, 293T cells were transfected with 30 pmol of siRNAs in 6-well culture dishes using Lipofectamine RNAimax (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At 24 hours after siRNA transfections, cultures were transfected with 1.25 ug of pCMVGagPol-RRE plasmid and 1.25 ug of pCMV-RevFlag plasmid or 2.5 ug pCMV-MPMV (CTE) plasmid. Culture supernatants were harvested 24 hours after the plasmid transfection to quantify HIV-1 p24Gag by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs; Advanced Bioscience Laboratories). For some PACS1 over-expression experiments, 293T cells were transfected with a PACS1-HA expression vector or parental vector. At 24 hours post-transfection, transfected cells were infected with VSV pseudotyped NL4-3 HIV-1-GFP virus. At 4 days (96 hours) post-infection, culture supernatant and total cytoplasmic RNA were extracted. PACS1 RNA and HIV-1 GagPol RNA levels were quantified by qRT-PCR. For additional PACS1 over-expression experiments, 293T cells were co-transfected with 2ug NL4-3 Luc proviral plasmid, 1ug VSV G expression plasmid, 0.1ug pRL-TK (wild type Renilla luciferase (Rluc) control reporter vectors), and either an PACS1-HA expression vector (pCMV-PACS1-HA) or parental vector (pCMV-Flag) in 6-well culture dishes using Lipofectamine®2000 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s directions. At 48 hours post-transfection, total p24 levels were analyzed by ELISA. In additional PACS1 over-expression experiments, 293T cells were co-transfected with 1.5 ug of pCMVGagPol-RRE plasmid and 1.5 ug of pCMV-Rev-Flag plasmid or 3 ug pCMV-MPMV (CTE) plasmid, and either an 1ug PACS1-HA expression vector (pBABE- PACS1-HA) or 1ug parental vector (pBABE) in 6-well culture dishes using Lipofectamine®2000 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s directions. At 72 hours post-transfection, total p24 levels were analyzed by ELISA assays.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear RNA were isolated from cultured cells by the PARIS™ Kit Protein and RNA isolation system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. AM1921). Total RNA was isolated from cultured cells using miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, cat. no. 217004), and Real-time RT-qPCR was performed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, cat. no. 4368814) and Powerup SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystem, cat. no. A25743) using primers for unspliced and spliced viral RNAs, and pre-GAPDH and processed GAPDH RNAs as controls. Primers for unspliced viral RNA: Unspliced-F 5’ GTCTCTCTGGTTAGACCAG 3’ Unspliced-R 5’CTAGTCAAAATTTTTGGCGTACTC 3’ Primers for spliced viral RNA: Spliced-F 5’ GTCTCTCTGGTTAGACCAG 3’ Spliced-R 5’ TTGGGAGGTGGGTTGCTTTGATAGAG Primers for unspliced GAPDH: Pre-GAPDH-F 5’ CCACCAACTGCTTAGCACC 3’ Pre-GAPDH-R 5’CTCCCCACCTTGAAAGGAAAT 3’.

Immunoprecipitations and immunoblots.

Immunoprecipitations were performed using anti-Flag M2 affinity gel (A2220) from Sigma-Aldrich or Pierce-anti-HA agarose from Thermo Scientific. Briefly, cultures transfected with Flag-tagged expression plasmids were lysed 48 h after transfection with EBC lysis buffer (Tris-HCl 50 mM, NaCl 120mM, and 0.5% NP-40, pH 8.0); 20 ul of the anti-Flag M2 affinity gel or anti-HA agarose was washed with lysis buffer three times and incubated with the cell lysates for four hours at 4°C. Following the incubation, beads were washed with lysis buffer, and bound proteins were eluted by mixing and heating the beads in sample loading buffer for 5 min at 95°C. Samples were spun in a microcentrifuge, and immunoprecipitates were loaded on a 4 to 15% Tris gradient gel (Bio-Rad). Gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked with 5% BSA for an hour, and probed with the appropriate antibodies.

Immunofluorescence.

For Leptomycin B experiments (LMB), 293T cells were transfected with 400 ng of pCMV-PACS1-HA in 24-well culture dishes using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At 24 hours after plasmid transfections, the cultures were treated with10 ng/mL LMB. After the indicated times of LMB treatment, cells were fixed with fixation buffer (4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) for 30 min at room temperature followed by permeabilization with 0.25 Triton-X-100 in PBS. The cells were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 2 h, and then incubated with the primary antibody- anti-HA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C followed by Alexa Fluor® 594 secondary antibody (A-11037, Life Technologies). For DAPI stains, cells were treated with 5 ug/ mL DAPI (D9542, Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 minutes before mounting. Images were taken using a deconvolution microscope at integrated Microscopy Core Laboratory in Baylor College of Medicine.

Flow cytometry.

At indicated time points, uninfected or HIV-1 NL4.3-infected Jurkat cells were washed with PBS/2%FBS and incubated with Zombie yellow viability dye for 30 minutes at 4°C (Biolegend). Cells were washed and fixed/permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer (BD Biosciences) 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed with Perm/Wash buffer and incubated with HA-APC (Miltenyi Biotec) and p24-PE (Beckman-Coulter) mabs for 60 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed and analyzed with a Gallios Flow Cytometer and Kaluza software (Beckman-Coulter). HA positivity was determined based on FMO-APC controls.

Polysome profiles.

HeLa cells were treated for 30 min at 37 °C with 100 μg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Post-treatment, cells were washed with cycloheximide containing phosphate-buffered saline before being lysed using polysome lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.5% (w/v) deoxycholate in RNase-free water, supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 1,000 U ml−1 RNasin and 100 μg ml−1 cycloheximide) for 10 min on ice. Post-nuclear fractions were obtained by centrifuging the lysates at 16,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were loaded on top of an 11-mL 15% to 45% sucrose gradients in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7,4, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 140 mM NaCl and ultracentrifuged for 2.5 hours at 38,000 rpm in a SW41Ti rotor (Beckman). The gradient was collected via bottom puncture on an ISCO Gradient Fractionator equipped with UA-6 UV spectrophotometer.

Results.

PACS1 co-immunoprecipitates with CRM1 and HIV-1 Rev.

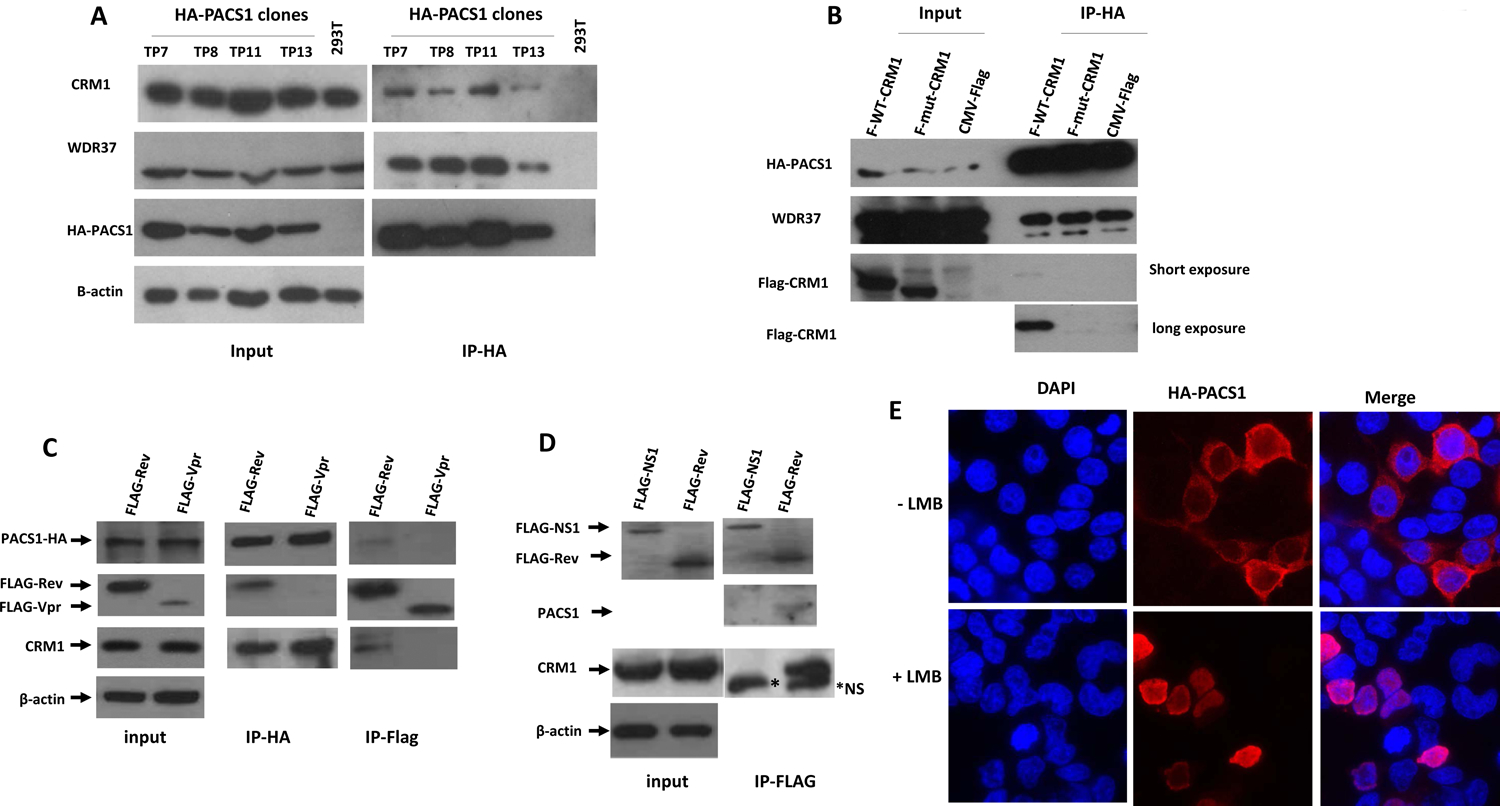

Using commercially available antisera against PACS1, we found that it was difficult to unequivocally identify endogenous PACS1 in immunoblots in Jurkat CD4+ T cells, primary CD4+ T cells, HeLa cells, or 293T cells. This may be due to low expression levels of PACS1 and/or poor quality antisera. We attempted to generate Jurkat cell lines that express an HA-tagged PACS1. However, we were unable to obtain Jurkat cell lines that stably express the PACS1-HA protein, suggesting that over-expression of PACS1 is selected against in Jurkat cells. To study the role of PACS1 in RNA export, we therefore generated 293T cell lines termed TP7, TP8, TP11, and TP13 that express PACS1 with an HA epitope tag at the carboxyl terminus (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. CRM1 and Rev co-immunoprecipitate with PACS1.

Four clonal 293T cell lines expressing a PACS1-HA cDNA were generated as described in Materials and Methods. A. Cell extracts were prepared from PACS1-HA cell lines (TP7, TP8, TP11, TP13) and parental 293T cells. Immunoprecipitations of cell extracts were performed with an anti-HA antibody; cell extracts (Input) and immunoprecipitates (IP-HA) were examined in an immunoblot. B. The TP11 PACS1-HA cell line was transfected with an expression plasmid for wild type Flag-CRM1 (F-WT-CRM1), mutant Flag-CRM1 (F-mut CRM1; deletion of residues 510–595), or parental Flag vector (CMV-Flag). Extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitations with an HA antibody were performed; cell extracts (Input) and immunoprecipitates (IP-HA) were examined by immunoblot. C. The TP8 PACS1-HA cell line was transfected with a Flag-Rev or a Flag-Vpr expression plasmid, cell extracts were prepared at 48 hours post-transfection and immunoprecipitations were performed with the HA or Flag antibodies; cell extracts (Input) and immunoprecipitates (IP-Flag and IP-HA) were examined in an immunoblot, using the HA antibody to detect PACS1-HA and Flag antibody to detect Flag-Rev and Flag-Vpr. D. Cultures of 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for a Flag-tagged influenza NS1 protein or Flag-Rev. Cell extracts were prepared at 48 hours post-transfection and immunoprecipitations were performed with a Flag antibody; cell extracts (input) and immunoprecipitates were examined in an immunoblot using the Flag antibody to detect NS1 and Rev, a PACS1 antiserum to detect endogenous PACS1, and a CRM1 antiserum to detect CRM1. A non-specific band detected in CRM1 immunoprecipitates is indicated by *NS. E. 293T cells were transfected with a PACS1-HA expression plasmid, treated with or without 10 ng/ml Leptomycin B (LMB) for 24 hours, and examined by immunofluorescence with an anti HA-antibody.

We prepared cell lysates from the PACS1-HA cell lines and parental 293T cells and performed immunoprecipitations with an anti-HA antibody. Immunoblot analysis of the immunoprecipitation products demonstrated that WDR37 (WD repeat domain 37) co-immunoprecipitated with PACS1-HA (Fig. 1A). WDR37 was identified as a partner of PACS1 in the HeLa nuclear complexome (Malovannaya, Lanz et al., 2011). CRM1 also co-immunoprecipitated with PACS1-HA from extracts of each of the PACS1-HA cell lines, also in agreement with the nuclear complexome data which reported that PACS1 and CRM1 are found in a protein complex (Malovannaya, Lanz et al., 2011).

To examine the specificity of the association between PACS1 and CRM1, we transfected 293T cells with a wild type or mutant Flag-CRM1 expression plasmid. The mutant plasmid expresses a CRM1 protein with deletion of residues 510 to 595; this region of CRM1 forms a hydrophobic groove that is the binding site for NES-containing proteins (Dong, Biswas et al., 2009). As expected, WDR37 was present in immunoprecipitations with the HA-antibody (Fig. 1B). The wild type but not mutant CRM1 protein co-immunoprecipitated with PACS1-HA, demonstrating a requirement of the CRM1 hydrophobic groove for the association with PACS1.

We next used co-immunoprecipitations to determine whether PACS1-HA could associate with the HIV-1 Rev protein. A Flag-Rev or a control Flag-Vpr expression plasmid were transfected into the TP11 PACS1-HA cell line, extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitations were performed with an HA or Flag antibody (Figure 1C). CRM1 was observed in the Flag immunoprecipitate of Flag-Rev transfected cells; PACS1-HA was also detected, albeit at a low level, in the immunoprecipitate from Flag-Rev transfected cells. In the Flag-Vpr transfected cells, neither CRM1 nor PACS1-HA were observed in the Flag immunoprecipitate. In an additional experiment to examine the association between PACS1 and Rev, a Flag-Rev or influenza a virus Flag-NS1 expression plasmid were transfected into parental 293T cells (Fig. 1D). A low level of endogenous PACS1 and abundant CRM1 were observed in the Flag immunoprecipitate from Flag-Rev transfected cells, while it was absent in Flag-NS1 transfected cells. These data suggest that PACS1 specifically associates with CRM1 and Rev in cells. The nature of this association is unclear. PACS1 may not make direct protein-protein contact with Rev, but may associate indirectly through a protein-protein interaction with CRM1 or through association with viral RNA undergoing Rev-mediated nuclear export.

PACS1 shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm.

PACS1 has been observed to be a predominantly cytoplasmic protein (Dikeakos, Thomas et al., 2012). Given the positive role of PACS1 in Rev function (Budhiraja, Liu et al., 2015) and its association with CRM1 and Rev demonstrated in Figure 1, we reasoned that PACS1 might shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm via a CRM1-dependent mechanism. Indeed, a PACS1-GFP fusion protein has been reported to accumulate in the nucleus when cells are treated with the specific inhibitor Leptomycin B (LMB) (Atkins, Thomas et al., 2014). LMB inhibits CRM1 through alkylation of Cys 528 in the NES-binding site (Kudo, Matsumori et al., 1999). To verify that PACS1 is LMB-sensitive, we transfected 293T cells with a PACS1-HA expression plasmid and examined PACS1 localization with and without LMB treatment (Fig. 1E). PACS1-HA was predominantly cytoplasmic in non-LMB-treated 293T cells, while it became predominantly nuclear in LMB-treated cells. We also observed nuclear accumulation of PACS1-HA after LMB treatment of the TP11 cell line (not shown). We conclude from these data that PACS1 shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm in a CRM1-dependent mechanism.

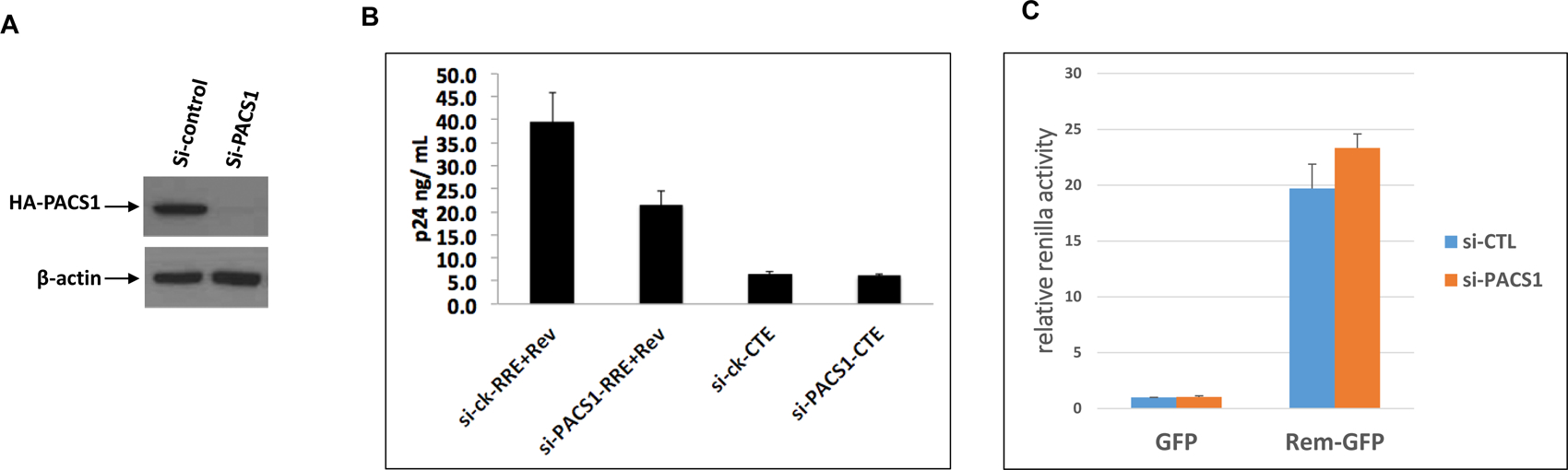

PACS1 siRNA depletion inhibits Rev-RRE but not CTE RNA nuclear export or MMTV CRM1-Rem nuclear export.

We previously reported that siRNA depletions of PACS1 inhibited Rev nuclear export of unspliced HIV-1 RNA as assayed with a pCMV-GagPol-RRE reporter plasmid (Budhiraja, Liu et al., 2015). To examine the specificity of PACS1 in RNA export, we used PACS1 siRNA depletions to evaluate the role of PACS1 in the CRM1-Rev export pathway, the Constitutive Transport Element (CTE) export pathway (Bray, Prasad et al., 1994), and the MMTV CRM1-Rem export pathway (Mertz, Simper et al., 2005). We used the TP8 cell line that expresses PACS1-HA to verify that siRNA targeting PACS1 mRNA are effective in depletion of PACS1 protein (Fig. 2A). In agreement with our previous finding, depletion of PACS1 showed a clear trend for inhibition of CRM1-Rev nuclear export as assayed by p24 expression from a transfected pCMV-GagPol-RRE reporter plasmid and a Rev expression plasmid (Fig. 2B). In contrast, PACS1 siRNAs had no effect on the CTE pathway as assayed by p24 expression of a pCMV-GagPol-CTE reporter plasmid. Similar to the CTE pathway, PACS1 depletion had no effect on MMTV Rem nuclear export as assayed with the pHRMLuc MMTV reporter plasmid (Fig. 2C). The data shown in Figure 2 suggest that PACS1 is a positive factor involved in increasing HIV-1 Rev nuclear export and is not involved in CTE nuclear export or MMTV CRM1-Rem nuclear export. Over-expression experiments presented below provide further support for this notion (Fig. 4C).

Figure 2. PACS1 siRNA depletions specifically inhibit Rev-RRE nuclear export pathway.

A. Cultures of the TP8 cell line expressing PACS1-HA were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA against PACS1. Cell extracts were prepared at 48 hours post-transfection and levels of PACS1-HA and β-actin were examined in an immunoblot. B. 293T cells were transfected with control siRNAs or siRNAs against PACS1, followed by transfection 24 hours later with a pCMVGagPol-RRE + Rev-expression plasmid or a pCMVGagPol-CTE4X expression vector. Supernatants were collected 48 hours later and p24 levels were quantified by ELISAs. Data presented are technical duplicates and the experiment is representative of three biological replicate experiments. C. 293T cells were transfected with control, siRNAs or siRNAs against PACS1, followed by transfection 24 hours later as indicated with pHMRLuc (Renilla Luciferase containing the Rem Response element), pCMV-Luc expressing firefly Luciferase, and EGFP or Rem-GFP expression plasmids. Renilla and firefly Luciferase activities were measured in cell lysates at 24 hours post-transfection. Relative firefly Luciferase values were calculated by normalizing to Renilla luciferase activity and setting the value to 1.0 in Control siRNA treated cells. Data presented represent three biological replicate experiments, each containing technical duplicates.

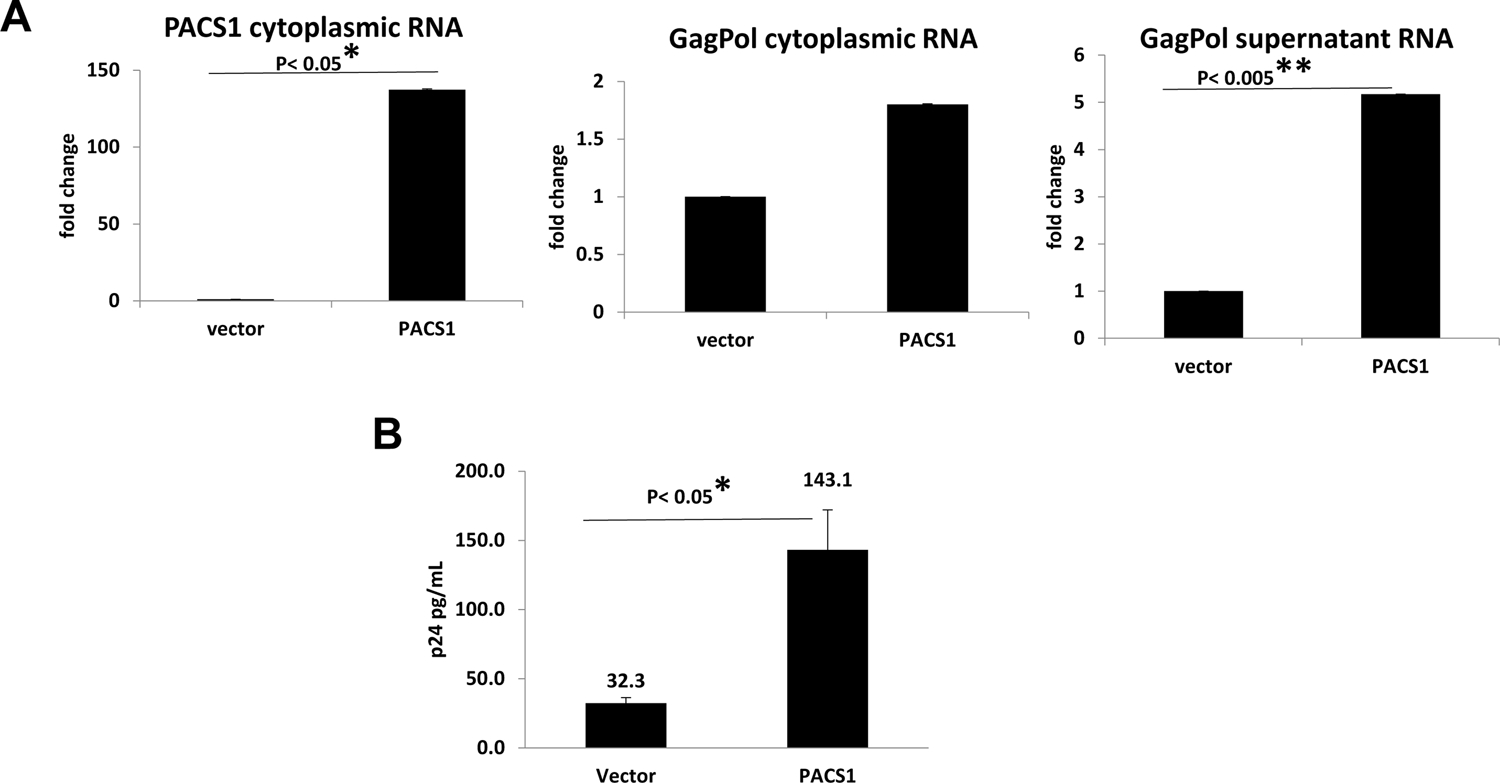

Figure 4. Over-expression of PACS1 stimulates HIV nuclear RNA export and p24 expression.

A. Cultures of 293T cells were transfected with a PACS1-HA expression vector or parental vector. At 24 hours post-transfection, cells were infected with HIV-1 NL4-3-Luciferase virus. At three days post-infection, cells and culture supernatants were collected. Cytoplasmic PACS1 and cytoplasmic GagPol RNA were quantified by real-time qRT-PCR, and normalized to GAPDH RNA. GagPol RNA in culture supernatants was quantified by real-time RT-PCR and normalized to the total protein of cultures. The levels GagPol RNA in vector transfected cells were assigned an arbitrary value of 1.0; level of RNA in PACS1-transfected cells is presented relative to this 1.0 value. Data presented are from three biological replicate experiments. B. Cultures of 293T cells were co-transfected with HIV-1 NL4-3-Luciferase proviral plasmid, a VSV-G expression plasmid, pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase reporter plasmid), and either an PACS1-HA expression vector or parental vector. At 48 hours post-transfection, total p24 levels were quantified by ELISA. Data presented in Panels A and B are from three biological replicate experiments. Values that were significantly different by a paired Student’s t test are indicated by a bar and asterisks as follows:*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005.

PACS1 over-expression increases HIV-1 RNA nuclear export and p24 expression.

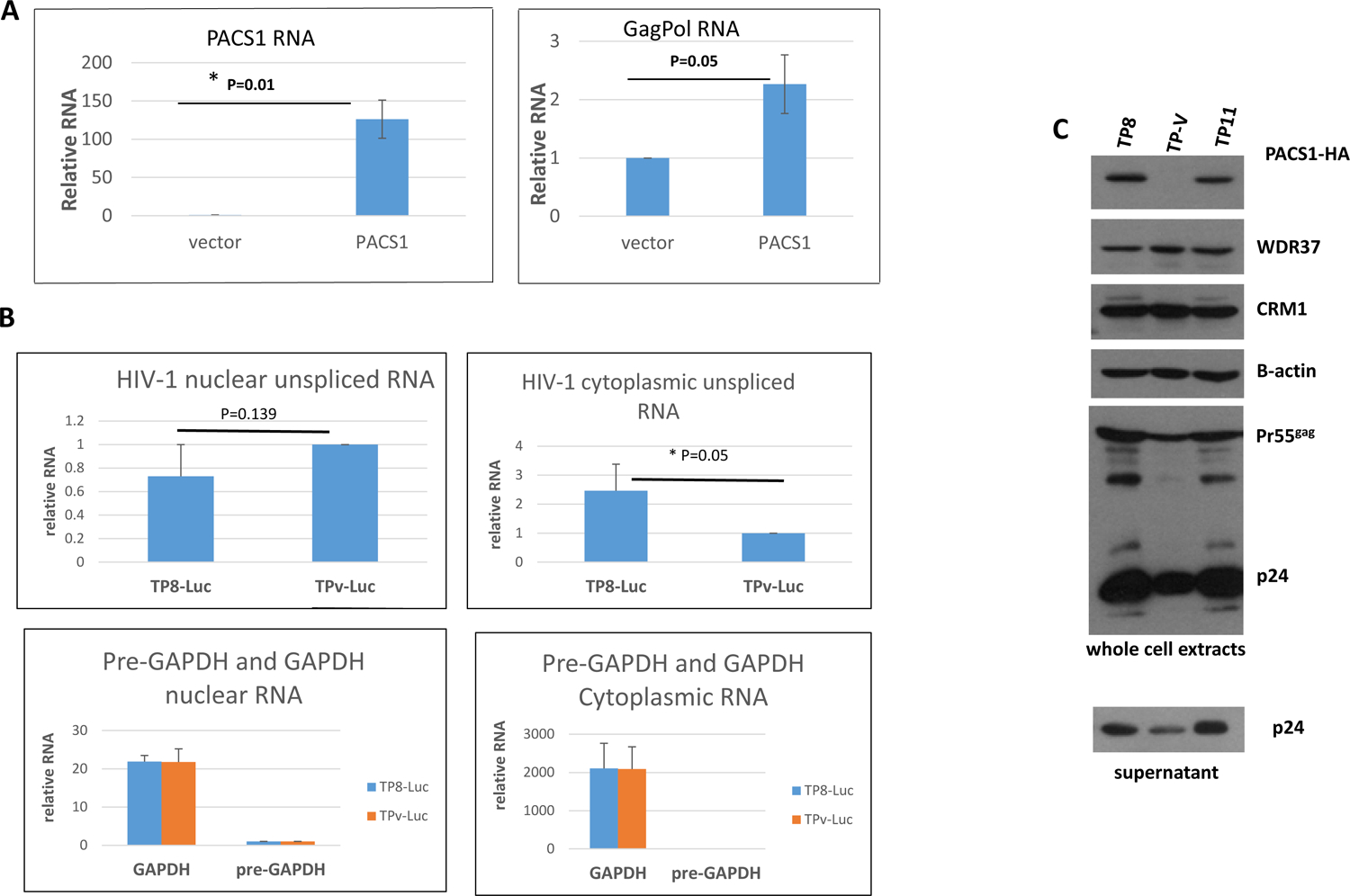

We next investigated if over-expression of PACS1 could stimulate nuclear export of unspliced HIV-1 transcripts. We co-transfected 293T cells with a pNL4-3-GFP (deleted for Vpr, Env, and Nef) proviral plasmid with either the PACS1-HA expression vector or the parental vector. Total cellular RNA was extracted at 48 hours post-transfection and levels of PACS1 RNA and HIV-1 GagPol RNA were quantified by qRT-PCR (Figure 3A). As expected, PACS1 RNA levels were greatly elevated in the PACS1-HA transfected cells relative to cells transfected with the parent vector. Co-transfection of the PACS1-HA expression plasmid increased unspliced GagPol RNA levels approximately 2.3-fold relative to the parental vector. These data suggest that over-expression of PACS1 can stimulate Rev nuclear export of unspliced viral transcripts.

Figure 3. Over-expression of PACS1 enhances nuclear export of unspliced HIV-1 RNA.

A. Cultures of 293T cells were transfected with a pNL4-3-GFP proviral plasmid and either a PACS1-HA expression vector or parental vector. At 48 hours post-transfection, total cellular RNA was extracted. PACS1 RNA (left panel) and HIV GagPol RNA (right panel) levels were quantified by qRT-PCR. Levels of PACS1 and GagPol RNA in vector transfected cells were assigned an arbitrary value of 1.0. *p < 0.05 in a paired Student’s t-test. B. PACS1-HA line TP8 and control TP-Vector (TPv) cell lines were infected with VSV G pseudotyped NL4-3-Luciferase virus and nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA was isolated at 48 hours post-infection. Levels of nuclear and cytoplasmic unspliced HIV-1, pre-GAPDH, and GAPDH RNAs were quantified by real time qRT-PCR. The data are from three biological replicate experiments; the indicated statistical significance was evaluated in a paired Student’s t-test. C. PACS1-HA clonal cell lines TP8, TP11, and control TP-Vector cell line were infected with a VSV G pseudotyped HIV-Luciferase reporter virus. Cell extracts were prepared at 48 hours post-infection and levels of indicated proteins were evaluated in an immunoblot. The level of PACS1 was evaluated with a polyclonal antiserum that detects both PACS1-HA and endogenous PACS1. The supernatant from cells was collected at 48 hours post infection and levels of p24 were evaluated in an immunoblot.

To confirm the experiment presented in Figure 3A, we infected the TP8 PACS1-HA and control TP-vector 293T cell lines (see Fig. 1) with VSV G pseudotyped NL4-3-Luciferase virus, isolated nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA at 48 hours post-infection, and used qRT-PCR to quantify unspliced viral RNAs (Figure 3B). GAPDH pre-mRNA and GAPDH mRNA were examined to evaluate the fractionation of nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA. The cytoplasmic level of pre-GAPDH RNA was greater than 2,000-fold less than of cytoplasmic GAPDH mRNA, while the level of nuclear pre-GAPDH was only 20-fold less than of GAPDH mRNA. These data indicate that our fractionation of nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA was effective. The nuclear level of unspliced viral RNA in the PACS1 over-expression cell line was 70% below that of the vector control cell line, although this difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, the level of unspliced viral RNA was 2.5-fold higher in the PACS1 over-expression cell line, and this difference was statistically significant. These data further indicate that over-expression of PACS1 enhances the level of unspliced viral RNA that is exported from the nucleus through the Rev pathway.

We utilized the PACS1-HA 293T cell lines TP8 and TP11 (see Fig. 1) to examine the effect of over-expressed PACS1 on Gag expression from its Rev-dependent mRNA during HIV-1 infection (Fig. 3C). TP8, TP11, and control TP-Vector cells were infected with a VSV G-pseudotyped HIV-1-Luciferase reporter virus. At 48 hours post-infection, cell extracts were prepared from a portion of the infected cells for immunoblot analysis, and RNA was extracted from another portion of infected cells; supernatants were also collected to examine the levels of p24 in culture supernatants. We observed an increase in level of p24 in both cell extracts and culture supernatants from the PACS1-HA TP8 and TP11 infected cells relative to the control TP-Vector infected cells. In agreement with the protein expression measurements, both PACS1 RNA and HIV-1 GagPol RNA were elevated in the TP8 and TP11 cell lines relative to the TP-Vector control (not shown).

The data presented in Figure 3 indicate that HIV-1 RNA nuclear export and p24 expression are enhanced in cell lines that over-express PACS1. To confirm these data, we performed additional experiments in which PACS1 was over-expressed transiently from expression plasmids. Cultures of 293T cells were transfected with a PACS1-HA expression plasmid or parental vector. At 24 hours-post transfection, cultures with infected with a VSV G-pseudotyped HIV-1 NL4-3 luciferase virus. At three days post infection, culture supernatants were collected and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared. RNA was extracted from both supernatants and cytoplasmic extracts and Gag-Pol and PACS1 RNAs were quantified by real-time RT PCR. Transfection of the PACS1 expression plasmid resulted in a large increase in PACS1 cytoplasmic RNA as expected (Fig. 4A). Transfection of the PACS1 plasmid resulted in a 1.8-fold increase in cytoplasmic GagPol RNA and a 5-fold increase in GagPol RNA in the culture supernatant (Fig. 4A).

In an additional experiment, cultures of 293T cells were co-transfected with the PACS1-HA expression plasmid or parental vector plus an HIV-1 NL4-3 Luciferase proviral plasmid. At 48 hours-post transfection, levels of p24 in culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA (Fig. 4B). Over-expression of PACS1 resulted in a 4.4-fold increase in p24 levels, in agreement with the PACS1 enhancement of GagPol RNA levels in culture supernatants in the experiment shown in Figure 4B.

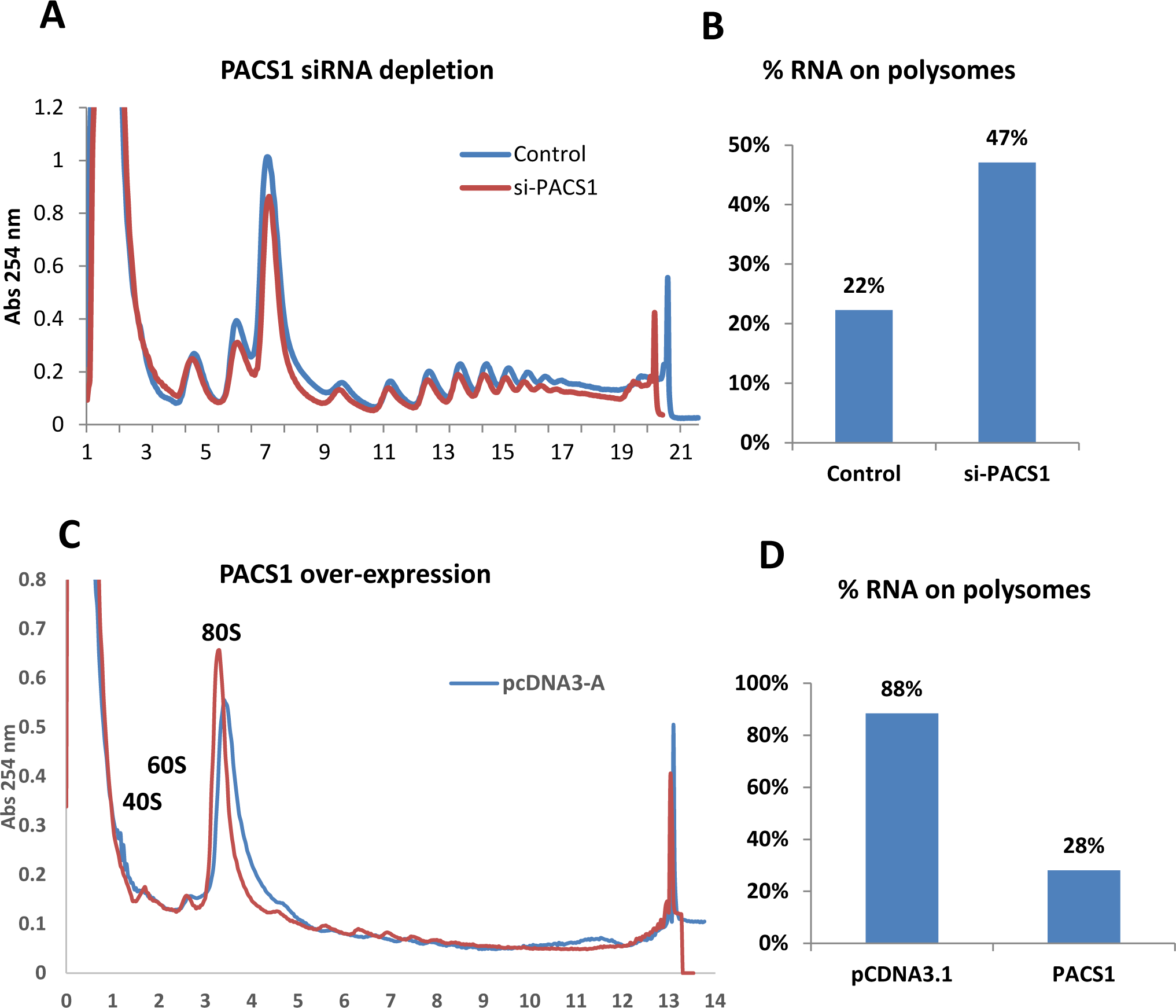

PACS1 appears to direct HIV-1 GagPol RNA to a pathway distinct from that of translation on polyribosomes.

We conducted polyribosome profiling experiments to examine if PACS1 may direct the trafficking of GagPol RNA to polyribosomes for translation (Fig. 5). For siRNA depletion, HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs that target PACS1 and 24 hours later cells were transfected with the CMV-GagPol-RRE and Rev expression plasmids; polysomes were prepared 48 hours later and levels of unspliced GagPol RNA in polysome fractions (Fig. 5A) were quantified by qRT-PCR (Fig. 5B). Although PACS1 depletion reduced the total level of GagPol RNA expressed from the CMV-GagPol vector, it resulted in an approximate 2-fold increase in the percentage of GagPol RNA on polysomes relative to the control siRNA sample. For the over-expression experiment, HeLa cells were transfected with a CMV- PACS1-HA expression plasmid or vector plasmid and 48 hours later cultures were infected with a VSG pseudotyped NL4-3-Luciferares HIV-1 reporter virus; polysomes were prepared 24 hours later and levels of unspliced GagPol RNA in polysome fractions (Fig. 5C) were quantified by qRT-PCR assays (Fig. 5D). Although over-expression of PACS1 increased the total level of GagPol RNA, it resulted in an approximate 3-fold reduction in percentage of GagPol RNA on polysomes relative to the vector control (Fig. 5D). These data indicate that depletion of PACS1 increases the fraction of GagPol RNA on polyribosomes, while over-expression decreases this fraction. Taken together, these data suggest that PACS1 directs GagPol RNA to a pathway that is distinct from that of translation on polyribosomes.

Figure 5. PACS1 directs unspliced HIV-1 RNA away from polysomes.

A. HeLa cells were transfected with PACS1 or control siRNAs and 24 hours later cultures were transfected with a CMV-GagPol-RRE and Rev expression plasmids; polysomes were prepared at 48 hours later as described in Materials and Methods. Levels of GagPol RNA in polysomes (fractions 11–19) were quantified by qRT-PCR. B. The percentage of total GagPol RNA in polysome fractions was quantified for Control and PACS1 siRNA samples. Data are representative of two biological repeat experiments. C. HeLa cells were transfected with a pCMV- PACS1-HA or vector plasmid and 48 hours later cultures were infected with a VSV G-pseudotyped NL4-3 Luciferase reporter virus; polysomes were prepared 24 hours later and levels of GagPol RNA were quantified by qRT-PCR assays. D. The percentage of total GagPol RNA on polysomes was calculated for CMV- PACS1-HA and vector transfected cells. Data are representative of two biological repeat experiments.

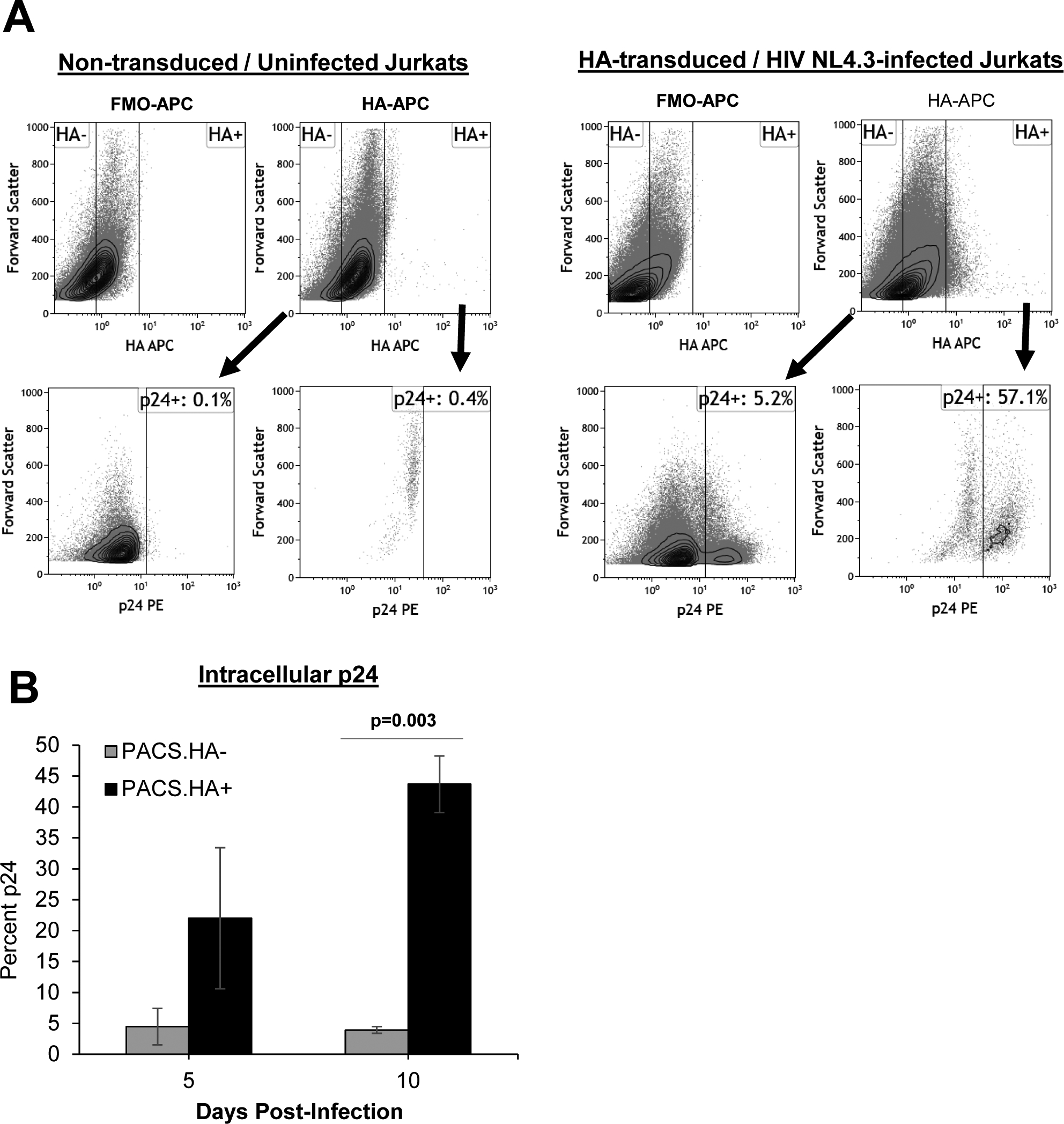

PACS1 over-expression enhances p24 expression in HIV-1-infected Jurkat CD4+ T cells.

In order to examine the effects of PACS1 over-expression in CD4+ T cells, we transduced Jurkat CD4+ T cells with a retroviral vector that expresses an HA-tagged PACS1 cDNA and a puromycin selection marker (see Materials and Methods). As stated above, we attempted to isolated clonal lines that over-express PACS1-HA, similar to the PACS1-HA 293T cell lines shown in Figure 1A. However, we observed that the expression level of PACS1-HA was not stable in Jurkat cell lines, suggesting that sustained over-expression of PACS1 is selected against in Jurkat cells. We therefore chose to perform short-term experiments in pools of Jurkat cells transduced with the PACS1-HA retrovirus vector. Cultures of Jurkat cells were transduced with the PACS1-HA retrovirus vector and subject to puromycin selection. Pools were then infected with HIV-1 NL4-3 and flow cytometry was used to evaluate intracellular PACS1-HA and p24 expression at 5 and 10 days post-infection. A representative experiment from four independent experiments is presented in Figure 6A; the summary of p24 expression at 5 and 10 days post-infection from the four experiments is shown in Figure 6B. There was a strong enhancement of p24 expression in HA+ vs. HA− cells at both 5 and 10 days post-infection. At 10 days post-infection, p24 expression was greater than 10-fold higher in the HA+ cell population. These data demonstrate that over-expression of PACS1 is associated with increased expression of p24 in HIV-1-infected CD4+ T cells, in agreement with the data presented in Figures 3 and 4 from experiments in HeLa and 293T cells.

Figure 6. Over-expression of PACS1 enhances p24 expression during HIV-1 infection in Jurkat CD4+ T cells.

A pool of PACS1-HA Jurkat CD4+ T cells were generated with a retroviral vector and puromycin selection as described in Materials and Methods. Cell pools were infected with HIV-1 NL4-3 and cultured for 5–10 days. Cells were examined for intracellular HA and p24 by flow cytometry. Jurkat cells non-transduced with PACS1-HA retrovirus and uninfected were examined as controls for the specificity of HA and p24 measurements. A. A representative p24 dot blot gated on HA− or HA+ cells at 10 days post-infection is shown. B. The summary is shown for the mean percentage of p24+ cells in HA− or HA+ cells at 5 and 10 days post-infection in four independent experiments. *p = 0.03 in a paired students t-test.

Discussion.

In this study, we have shown that PACS1 is involved in Rev-mediated nuclear export of HIV-1 RNAs. Previous studies presented evidence that PACS1 associates with the viral Nef protein and is involved in down-regulation of MHC class I (Blagoveshchenskaya, Thomas et al., 2002;Dikeakos, Thomas et al., 2012;Piguet, Wan et al., 2000). It should be noted, however, that the notion that PACS1 is involved in MHC class I down-regulation is somewhat controversial (Baugh, Garcia et al., 2008). PACS1 also has a role, albeit indirect, in Furin cleavage of the HIV-1 Envelope gp160 protein, as PACS1 mediates localization of Furin to the TGN where it cleaves Envelope (Hallenberger, Bosch et al., 1992;Wan, Molloy et al., 1998). Thus, PACS1 is a multi-tasking co-factor that appears to participate in multiple distinct processes of the HIV-1 replication cycle – nuclear export of viral RNA, down-regulation of MHC class I, and cleavage of the viral Envelope protein.

In the present study, we have provided extensive data indicating that PACS1 is a Rev co-factor. PACS1 can be co-immunoprecipitated with Rev and CRM1, and its over-expression stimulates the level of unspliced HIV-1 transcripts in the cytoplasm and in virions that bud into the culture supernatant. We confirmed a previous report that PACS1 shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm, a property consistent with that of a Rev co-factor (Atkins, Thomas et al., 2014). We have also shown that PACS1 is specific for the Rev-CRM1 nuclear export pathway, as siRNA depletion of PACS1 has no observable effect on nuclear export via the MMTV Rem-CRM1 pathway or the MPMV Constitutive Transport Element pathway that utilizes the NXF1/NXT1 export pathway. It is perhaps not surprising that PACS1 does not have a role in the CTE-NXF1/NXT1 pathway, as live cell imaging has demonstrated that the Rev-CRM1 and CTE-NXF1 export pathways have distinct trafficking properties. Viral RNA exported via the Rev-CRM1 pathway traffics to the cytoplasm in a non-localized fashion, while RNA exported via the CTE-NXF1/NXT1 pathway traffics to microtubules in the cytoplasm (Pocock, Becker et al., 2016). The role of PACS1 in the HIV-1 Rev-CRM1 export but not MMTV Rem-CRM1 export indicates that these two viral proteins utilize divergent CRM1-dependent pathways by mechanisms that remain to be identified.

SiRNA depletion and over-expression experiments suggest that PACS1 may direct GagPol RNA to a pathway that is distinct from that of translation on polyribosomes (Fig. 5). It is possible that PACS1 functions to direct GagPol RNA to the plasma membrane where the RNA is packaged into virions. Features at the 5’ end of HIV-1 GagPol RNA have been identified that direct the RNA to polyribosomes or to the plasma membrane (Kharytonchyk, Monti et al., 2016). RNA Polymerase II transcriptional start site heterogeneity generates viral RNAs that contain from one to three guanosines at the 5’ end. A single 5’ capped guanosine directs GagPol RNA to the plasma membrane to be selectively packaged in virions, while two or three 5’ capped guanosines directs the RNA to polysomes (Kharytonchyk, Monti et al., 2016). Cellular factors have been identified that are involved in directing GagPol RNA to translation on ribosomes. The methyltransferase PIMT is responsible for a trimethylguanosine-cap in some Rev dependent viral transcripts and this is thought to promote translation (Yedavalli & Jeang, 2010). A Rev-CBP80-eIF4AI complex has recently been shown to promote translation of Rev-dependent transcripts (Toro-Ascuy, Rojas-Araya et al., 2018). To our knowledge, no cellular factors have been identified that are involved in the selective trafficking of HIV-1 GagPol RNA to the plasma membrane for packaging into virions. As Rev has been shown to enhances packaging of HIV-1 RNA into virions (Blissenbach, Grewe et al., 2010;Brandt, Blissenbach et al., 2007), it is possible that PACS1 is a cellular factor involved in this process.

While lower metazoans encode a single PACS gene, higher metazoans encode two related PACS genes – PACS1 and PACS2. Both proteins are broadly expressed in all tissues examined, although PACS1 is selectively enriched in peripheral blood lymphocytes and this may be of significance to HIV-1 infection (Youker, Shinde et al., 2009). Both PACS1 and PACS2 regulate membrane trafficking, including TGN localization (Youker, Shinde et al., 2009), and both proteins shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm [(Atkins, Thomas et al., 2014), Fig. 1]. As shown here, PACS1 is involved in Rev-mediated nuclear RNA export, while PACS2 has been shown to regulate SIRT1 deacetylation of p53 in the nucleus (Atkins, Thomas et al., 2014). Thus, both PACS1 and PACS2 are multi-functional proteins that are involved in both nuclear and cytoplasmic processes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants AI114335 (to A.P.R.), AI116167 (to J.T.K), and P30AI1036211 [Baylor College of Medicine-University of Texas at Houston Center for AIDS Research (CFAR)]. We thank Dr. Mary Marie Louise Hammarskjöld (University of Virginia), Dr. Jacquelin Dudley (University of Texas, Austin) and Dr. Gary Thomas (University of Pittsburgh) for plasmids.

References

- Atkins KM, Thomas LL, Barroso-Gonzalez J, Thomas L, Auclair S, Yin J, Kang H, Chung JH, Dikeakos JD, Thomas G, 2014. The multifunctional sorting protein PACS-2 regulates SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of p53 to modulate p21-dependent cell-cycle arrest. Cell Rep. 8, 1545–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh LL, Garcia JV, Foster JL, 2008. Functional characterization of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef acidic domain. J Virol. 82, 9657–9667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagoveshchenskaya AD, Thomas L, Feliciangeli SF, Hung CH, Thomas G, 2002. HIV-1 Nef downregulates MHC-I by a PACS-1- and PI3K-regulated ARF6 endocytic pathway. Cell 111, 853–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blissenbach M, Grewe B, Hoffmann B, Brandt S, Uberla K, 2010. Nuclear RNA export and packaging functions of HIV-1 Rev revisited. Journal of Virology 84, 6598–6604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt S, Blissenbach M, Grewe B, Konietzny R, Grunwald T, Uberla K, 2007. Rev proteins of human and simian immunodeficiency virus enhance RNA encapsidation. PLoS Pathog. 3, e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray M, Prasad S, Dubay JW, Hunter E, Jeang KT, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold ML, 1994. A small element from the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus genome makes human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression and replication Rev-independent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 91, 1256–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budhiraja S, Liu H, Couturier J, Malovannaya A, Qin J, Lewis DE, Rice AP, 2015. Mining the human complexome database identifies RBM14 as an XPO1-associated protein involved in HIV-1 Rev function. J Virol 89, 3557–3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman F, Lewinski M, Ciuffi A, Barr S, Leipzig J, Hannenhalli S, Hoffmann C, 2005. Genome-wide analysis of retroviral DNA integration. Nat Rev.Microbiol 3, 848–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen BR, 2003. Nuclear mRNA export: insights from virology. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 28, 419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikeakos JD, Thomas L, Kwon G, Elferich J, Shinde U, Thomas G, 2012. An interdomain binding site on HIV-1 Nef interacts with PACS-1 and PACS-2 on endosomes to down-regulate MHC-I. Mol Biol Cell 23, 2184–2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Biswas A, Suel KE, Jackson LK, Martinez R, Gu H, Chook YM, 2009. Structural basis for leucine-rich nuclear export signal recognition by CRM1. Nature 458, 1136–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes JD, Booth DS, Frankel AD, 2016. A structurally plastic ribonucleoprotein complex mediates post-transcriptional gene regulation in HIV-1. Wiley.Interdiscip.Rev.RNA, 7:470–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed EO, Martin MA, 1994. HIV-1 infection of non-dividing cells. Nature 369, 107–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golebiewski L, Liu H, Javier RT, Rice AP, 2011. The Avian Influenza Virus NS1 ESEV PDZ Binding Motif Associates with Dlg1 and Scribble To Disrupt Cellular Tight Junctions. J Virol 85, 10639–10648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallenberger S, Bosch V, Angliker H, Shaw E, Klenk HD, Garten W, 1992. Inhibition of furin-mediated cleavage activation of HIV-1 glycoprotein gp160. Nature 360, 358–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharytonchyk S, Monti S, Smaldino PJ, Van V, Bolden NC, Brown JD, Russo E, Swanson C, Shuey A, Telesnitsky A, Summers MF, 2016. Transcriptional start site heterogeneity modulates the structure and function of the HIV-1 genome. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A 113, 13378–13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyanagi Y, Miles S, Mitsuyasu RT, Merrill JE, Vinters HV, Chen IS, 1987. Dual infection of the central nervous system by AIDS viruses with distinct cellular tropisms. Science 236, 819–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo N, Matsumori N, Taoka H, Fujiwara D, Schreiner EP, Wolff B, Yoshida M, Horinouchi S, 1999. Leptomycin B inactivates CRM1/exportin 1 by covalent modification at a cysteine residue in the central conserved region. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A 96, 9112–9117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malovannaya A, Lanz RB, Jung SY, Bulynko Y, Le NT, Chan DW, Ding C, Shi Y, Yucer N, Krenciute G, Kim BJ, Li C, Chen R, Li W, Wang Y, O’Malley BW, Qin J, 2011. Analysis of the human endogenous coregulator complexome. Cell. 145, 787–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertz JA, Simper MS, Lozano MM, Payne SM, Dudley JP, 2005. Mouse mammary tumor virus encodes a self-regulatory RNA export protein and is a complex retrovirus. Journal of Virology 79, 14737–14747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piguet V, Wan L, Borel C, Mangasarian A, Demaurex N, Thomas G, Trono D, 2000. HIV-1 Nef protein binds to the cellular protein PACS-1 to downregulate class I major histocompatibility complexes. Nat.Cell Biol 2, 163–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock GM, Becker JT, Swanson CM, Ahlquist P, Sherer NM, 2016. HIV-1 and M-PMV RNA Nuclear Export Elements Program Viral Genomes for Distinct Cytoplasmic Trafficking Behaviors. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poss M, Overbaugh J, 1999. Variants from the diverse virus population identified at seroconversion of a clade A human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected woman have distinct biological properties. J Virol. 73, 5255–5264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shida H, 2012. Role of Nucleocytoplasmic RNA Transport during the Life Cycle of Retroviruses. Front Microbiol. 3, 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan KE, Gleizes PE, Bohnsack MT, 2016. Nucleocytoplasmic Transport of RNAs and RNA-Protein Complexes. J Mol.Biol 428, 2040–2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro-Ascuy D, Rojas-Araya B, Garcia-de-Gracia F, Rojas-Fuentes C, Pereira-Montecinos C, Gaete-Argel A, Valiente-Echeverria F, Ohlmann T, Soto-Rifo R, 2018. A Rev-CBP80-eIF4AI complex drives Gag synthesis from the HIV-1 unspliced mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan L, Molloy SS, Thomas L, Liu G, Xiang Y, Rybak SL, Thomas G, 1998. PACS-1 defines a novel gene family of cytosolic sorting proteins required for trans-Golgi network localization. Cell 94, 205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yedavalli VS, Jeang KT, 2010. Trimethylguanosine capping selectively promotes expression of Rev-dependent HIV-1 RNAs. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A 107, 14787–14792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youker RT, Shinde U, Day R, Thomas G, 2009. At the crossroads of homoeostasis and disease: roles of the PACS proteins in membrane traffic and apoptosis. Biochem.J 421, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]