Abstract

Background:

Beyond the severity of voice, speech, and language impairments, one potential predictor of communication success across adult populations with communication disorders may be perceived social support: the expectation that others will provide support if needed. Despite the preponderance of intervention approaches that assume a positive relationship between perceived social support and patient-reported communication success, the evidence base for these relationships is limited.

Aims:

The aim of this systematic review is to explore relationships between measures of perceived social support and patient-reported communication outcomes in adult populations with communication disorders.

Methods & Procedures:

PRISMA guidelines were followed in the conduct and reporting of this review. Electronic databases including PubMed, PsychINFO, and CINAHL were systematically searched up to May 19, 2017. Additional data were obtained for two studies. All of the included studies were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) tools. Given the heterogeneous nature of the studies, data synthesis was narrative for the quantitative studies. A meta-ethnographic approach was used to synthesize qualitative data.

Outcomes & Results:

Eight quantitative and 4 qualitative studies met eligibility criteria. All quantitative studies met 8 of 8 quality criteria. For the qualitative studies, one study met 9 of 9 quality criteria; the remaining three studies met 3, 7, and 8 quality criteria. Of the 8 included quantitative studies, 6 independent datasets were used. Results revealed no significant relationships between perceived social support and communication outcomes in three studies (2 aphasia with one dataset, 1 Parkinson’s Disease), while perceived social support was a weak, but significant predictor in two studies (1 multiple sclerosis, 1 head and neck cancer). Three additional studies (2 aphasia with one dataset; 1 Parkinson’s Disease) found that relationships were initially weak, but strengthened over time to become moderate. Results from qualitative studies (1 head and neck cancer, 2 aphasia, 1 multiple sclerosis) revealed that perceived social support acted as a facilitator, and absent or misguided support acted as a barrier to communication outcomes. Skillful, responsive family members were able to facilitate better quality of communicative interactions, whereas lack of social support, or negative attitudes and behaviours of other people, were barriers.

Conclusions & Implications:

While perceived social support may affect communication outcomes in adults with communication disorders, current measures may not adequately capture these constructs. Results have implications for future research and interventions for speech and language therapists.

Keywords: outcome, adults, disorder, psychosocial

Introduction

The impact of having a communication disorder is considerable. Individuals with different types of communication disorders may participate in fewer social activities with less satisfaction (Baylor et al. 2011). In addition, work, family life, relationships, and social roles may be disrupted, and communication partners might react in adverse ways (Yorkston et al. 2001). One way to capture the broad consequences of having a communication disorder is to include the patient’s perspective by using patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures (U. S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration 2009). A PRO measure is any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or others, such as family members or other proxies. PRO measures are increasingly used to document disease- or condition-specific effects as well as treatment outcomes for a wide number of communication disorders (e.g., Eadie et al. 2006, Hilari et al. 2012). For example, PRO measures for adults with communication disorders include the Voice Handicap Index (VHI: Jacobson et al. 1997), the Communicative Participation Item Bank (CPIB: Baylor et al. 2013), the Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale-39 (SAQOL-39; Hilari et al. 2003), the Communicative Effectiveness Survey (CES: Donovan et al. 2008), the Burden of Stroke Scale (BOSS; Doyle et al. 2004), the Assessment for Living with Aphasia (ALA: Simmons-Mackie et al. 2014), and the Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering (OASES; Yaruss and Quesal 2006), among others.

Many factors affect patient-reported communication success in everyday contexts for people with communication disorders. The most obvious variable that may affect communication success is the severity of the person’s speech, voice, or language impairment (e.g., severity of dysarthria, dysphonia, or word-finding abilities). Yet, patients with mild impairments, as determined by objective or clinician-rated measures, quite frequently report devastating effects on their communication in context. The opposite scenario also arises in which a person has a severe impairment, but still reports satisfaction in communicating in everyday roles. These clinical scenarios are mirrored in the literature: results from PRO measures often only correlate weakly with traditional measures of disorder severity (Awan et al. 2014, Constantinescu et al. 2017, Donovan et al. 2008, Eadie et al. 2016, McAuliffe et al. 2010, Williamson et al. 2011). For example, Donovan et al. (2008) reported a weak correlation between speech intelligibility rated by unfamiliar listeners and self-reported communicative effectiveness in individuals with Parkinson’s Disease. Constantinescu et al. (2017) found weak, non-significant relationships between speech intelligibility rated by unfamiliar listeners and a PRO measure related to speech handicap in speakers with oral cancer. Awan et al. (2014) reported weak correlations between acoustic measures of dysphonia and patient-rated voice handicap, as well as between clinician-rated measures of voice quality and voice handicap in those with voice disorders. Likewise, Williamson et al. (2011) found weak, non-significant relationships between aphasia severity measured by performance on a standard aphasia battery and self-reported quality of life scores in people with aphasia. Together, these results demonstrate that PRO measures capture constructs that go beyond the severity of speech, voice, or language impairments.

Knowing which variables influence patient-reported communication success is essential for building empirical models upon which future interventions may be founded. Consequently, many authors have investigated other variables that affect communication, beyond impairment measures. Yorkston et al. (2001) found that factors related to a person’s physical condition (e.g., vision, mobility, fatigue), or mental function (e.g., cognition, depression) affected communication outcomes in people with multiple sclerosis. Others have focused on how factors related to personality, as well as individual coping responses, affect PRO measures related to communication, such as those reported in teachers with and without voice disorders (Van Wijck-Warnaar et al. 2010). Finally, factors in the environment may affect communicative success, and include physical barriers such as background noise (Eadie et al. 2016), and those related to the social environment, such as a communication partners’ attitudes. All of these variables have been found to affect PRO measures related to communication in many different populations, including those with multiple sclerosis (MS), head and neck cancer (HNC), Parkinson’s Disease (PD), and aphasia (Baylor et al. 2010, Eadie et al. 2016, Hilari et al. 2012, McAuliffe et al. 2016).

One environmental factor that may be an important facilitator or barrier to communication success is social support. Although the influence of social relationships has been conceptualized and measured in a variety of ways, it can be divided into both structural and functional aspects (Holt-Lunstad and Uchino 2015). Structural aspects of relationships refer to the extent to which individuals are situated within or integrated into social networks. For example, this construct might be assessed by measures that indicate marital status, whether a person lives alone, the density or number of social contacts, or complex measures that capture a person’s active engagement in a variety of social activities or relationships. In contrast, functional support refers to the specific functions served by relationships such as help in daily activities or companionship. It is measured by actual (received) support or by the perceived availability of emotional, informational, tangible, or belonging support, if needed, from these relationships (i.e., called perceived support) (Holt-Lunstad and Uchino 2015).

Associations between both structural and functional aspects of support and health-related outcomes have been investigated. In general, studies across a wide number of health-related conditions (i.e., not necessarily those with communication disorders) have shown that those reporting greater social support have greater odds of survival and lower morbidity than those lacking social support (Holt-Lunstad et al. 2010, Holt-Lunstad and Uchino 2015). Yet, different types of social support have different relationships with health-related outcomes. For example, complex measures of social integration (i.e., structural measures of social support) are more closely linked with physical health outcomes than functional measures (Holt Lunstad et al. 2010). In contrast, structural measures of social support are not as consistently correlated with measures of mental health (Teo et al. 2013). Among the functional measures, perceived support is consistently linked with better mental and physical health, whereas received support is not (Barrera, 1986, Pinquart and Sorensen 2013, Uchino, 2009, Wills and Shinar 2000). Thus, it is important to consider which aspects of social support are being examined when comparing results across studies. In this paper, we focus on the construct of perceived social support.

While the role of perceived social support has been studied in a number of populations, it is less understood among those with communication disorders (Hilari et al. 2012). Baylor et al. (2010) investigated variables associated with PRO measures of communicative participation in community-dwelling adults with MS. Of the 13 variables that were included in their model, 6 were found to account for almost half the variance in scores. Self-reported measures of fatigue, slurred speech, depression, problems thinking, employment status, and perceived social support emerged as significant predictors. The study was then extended with repeated measures of communicative participation over two years (Baylor et al. 2012). A growth-mixture modeling analysis found relatively stable communicative participation over time. However, three latent classes were evident in the data, suggesting different levels of communicative participation restrictions. The class with the least restrictions in communicative participation was characterised by fewer symptoms of slurred speech, depression, and fatigue. The class with moderate restrictions in communicative participation was characterised by low perceived social support. The class with the greatest restrictions in communicative participation was characterised by low perceived social support and more self-reported cognitive symptoms. While these two preliminary studies suggest multiple variables that may be associated with communicative participation, one limitation of the studies is that a large portion of the sample did not report having notable communication disorder symptoms. Whether different results might be found exclusively in individuals with communication disorder symptoms is unknown. Yet, among those who reported the most difficulties in communicative participation, perceived social support emerged as an important predictor.

A few studies have examined the role of social support for people with communication disorders, but these studies primarily have used PRO measures that focus on broader constructs such as quality of life (QOL). For example, increased perceived social support has been shown to positively affect health-related QOL outcomes in adults who stutter, individuals with aphasia, those treated for HNC, and stroke survivors, among others (Boyle 2015, Hilari et al. 2012, Karnell et al. 2007, Kruithof et al. 2013). The challenge in using health-related QOL measures to understand the relationship between social support and communication, however, is that health-related QOL measures typically include a wide range of constructs, and may not directly address communication. QOL questionnaires often only include one or two, if any, items related to communication. Consequently, results from health-related QOL measures may not sufficiently address questions about the role of social support as it specifically pertains to communication outcomes.

The purpose of this systematic review was to explore relationships between measures of perceived social support and patient-reported communication outcomes in adult populations with communication disorders. Determining how perceived social support affects patient-reported communication outcomes is important for identifying potential future targets for intervention that may extend beyond a focus on the speech or language impairment. A cross-disorder approach for this review may reveal whether results generalise across populations, or if there are disorder-specific factors that may deserve consideration for future research and clinical practice.

Methods

The PRISMA guidelines formed the basis of the conduct and reporting of this systematic review (Liberati et al. 2009).

Eligibility criteria

Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included in the review. Only studies originally published in English were considered because this reflects the linguistic experience of the team of researchers conducting the review. There was no restriction on the original publication date or geographical location.

To be included, studies had to report on relationships between perceived social support and patient-reported communication outcomes in adults with communication disorders. Populations included in the review were individuals 18 years of age and over with aphasia, dysarthria, apraxia of speech, voice disorders, fluency disorders, and those with speech, language, and/or cognitive-communication disorders secondary to HNC (including laryngectomy) and traumatic brain injury. Because communication contexts vary by age (child vs. adult), comparisons were limited to adult participants. Thus, studies involving pediatric populations (< 18 years) and individuals with developmental disorders (except fluency disorders) were excluded. To ensure the validity of patient-reported responses, individuals with moderate to severe cognitive symptoms were excluded. The focus of the investigation was on speech and language disorders; as a result, individuals with hearing disorders also were excluded.

For quantitative studies, only those using validated PRO measures of perceived social support were included. For the purposes of this review, a validated PRO measure was one that had some demonstrated properties of reliability and validity. Structural aspects of social support (e.g., social networks or other indicators such as marital status) and received social support measure different constructs than perceived social support (Barrera 1986, Uchino 2009, Wills and Shinar, 2000). In addition, perceived social support has been found to be a more consistent predictor of both mental and physical health outcomes than structural and received social support. As a result, studies that only included measures of received (actual) social support or other structural aspects of social support were excluded.

Studies also needed to include validated PRO measures of communication related to speech, voice, or language; included measures needed to have demonstrated properties related to reliability and validity. There were no restrictions on what constructs the PRO measured, as long as they were related specifically to communication. For example, participants might be rating the severity of their symptoms in their own view, difficulties with communication, how communication made them feel, or other constructs. Studies that included only PROs that were health-related QOL instruments (e.g., with less than three items related to speech, voice, or language) were excluded because the relationship between social support and communication outcomes would likely be confounded by other constructs in the QOL instruments. Studies on hearing impairment were excluded due to the focus in this study on speech and language disorders.

All responses to items on the outcome measures included in the quantitative studies needed to be from the person with the communication disorder (i.e., patient-reported). Responses generated by proxies such as clinicians or family members may yield different results from the individual with the communication disorder (Baylor et al. 2017, Cruice et al. 2005). As a result, studies that solely included responses from proxy raters were excluded.

For qualitative studies, included papers needed to be explicit about their use of qualitative methods and focus on the experiences of participants with communication disorders. Further, only qualitative studies that reported on an aspect of perceived social support as it related to communication were included. Studies that reported on themes related to perceived social support and to communication separately, with no direct link between the themes, were excluded.

Sources of Information and Search Strategy

Electronic databases were searched up to May 2017 including: PubMed, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. Requests for additional (post-hoc) data were made to four authors of studies selected for review; two responded and these data subsequently were included.

Broad search terms were created related to perceived social support, communication disorders, and patient-reported communication outcomes. Additional specific search terms related to categories of communication disorders (e.g., voice disorders, PD) and associated PRO measures (e.g., VHI; Jacobson et al. 1997) also were included. Searches were conducted in each database combining terms within lists (perceived social support, communication disorder, PRO measures) with OR, and combining across lists with AND (see Table 1 for a comprehensive list of search terms that also include specific PRO measures). Searches in PubMed used the filter “All adult.” The initial search was conducted by one author (MKS) in April 2016, and then re-run in May 2017. Search results were stored on MyNCBI. Additional studies, including unpublished studies, were assessed based on a screening of references listed in included studies.

Table 1.

Search terms for systematic review

| Broad Search Area | Search terms included |

|---|---|

| Perceived social support | social support, social satisfaction, social participation |

| Communication disorders (general) | communicat* disorder*, speech disorder*, language disorder*, communication impairment*, speech impairment*, language impairment* |

| PRO – communication (general) | communicat* participation, communicat* effectiveness, patient reported outcome*, lived experience* |

| Aphasia | aphasi*, dysphasi* |

| PRO(C) - aphasia | Burden of Stroke Scale, Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale, Communication Confidence Rating Scale, Quality of Communication Life, Communicat* Participation, lived experience* |

| Apraxia of speech (AOS) | apraxi*, dyspraxi*, motor speech disorder* |

| PRO(C) - AOS | Communicat* Participation, lived experience* |

| Dysarthria | dysarthri*, motor speech disorder*, Parkinson* Disease, Multiple Sclerosis, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Muscular Dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, motor neuron disease* |

| PRO(C) - dysarthria | Communicative Effectiveness Survey, Quality of Life of the Dysarthric Speaker, Living with Dysarthria, Dysarthria Impact Profile, Everyday Communication in Dysarthria, Communicat* Participation, lived experience* |

| Fluency disorders | stutter*, clutter*, dysfluen* |

| PRO(C) - fluency | Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering, Stutterer’s Self Ratings of Reactions to Speech Situations, Perceptions of Stuttering Inventory, S scale and S24, Speech Situations Checklist, Communication Attitude Test*, Communicat* Participation, lived experience* |

| Head and neck cancer (HNC) | head and neck cancer, oral cancer, *pharyngeal cancer, laryngeal cancer, laryngectom* |

| PRO(C) - HNC | Speech Handicap, Voice Handicap, Voice-Related Quality of Life, Voice Symptom Scale, Communication-Related Quality of Life, Self Evaluation of Communication Experiences, Communicat* Participation, lived experience* |

| Voice disorders | dysphoni*, aphoni*, hoarse*, voice disorder* |

| PRO(C) - voice disorders | Voice Activity and Participation Profile, Voice Handicap, Voice-Related Quality of Life, Voice Symptom Scale, Communicat* Participation, lived experience* |

| Traumatic brain injury (TBI) | cognitive impairment, TBI, traumatic brain injury, post-concussion, cognitive-communication, executive dysfunction, dysexective syndrome |

| PRO(C) - TBI | Cognitive Communication Checklist for Acquired Brain Injury, Dysexecutive Questionnaire, Communicat* Participation, lived experience* |

Note. PRO(C) = patient-reported outcome measure related to communication

Screening, data extraction, critical appraisal, and data synthesis

Each abstract of the articles obtained through the search strategy above was screened against inclusion and exclusion criteria by two of the four authors conducting the screening (two of TE, MKS, SB, CS). In cases of disagreement, consensus was reached through discussion between the two reviewers. Where eligibility could not be determined through review of the abstract alone, studies were passed through to full-text review. All studies with abstracts that indicated possible eligibility were subjected to a full-text review by all four screening authors. In cases of disagreement, consensus was reached through discussion.

Data were extracted from each eligible study by one author, and reviewed by a second author. For all studies, data included publication information, the research question/purpose, participant information, major findings, conclusions, and limitations. Critical appraisal of the included studies was performed by one of the authors, and then done independently by a second author. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion with the entire team. The authors who performed the critical appraisal were not authors of the papers they reviewed. All included studies were appraised, consistent with the traditional approach for study inclusion in systematic reviews (Glass 2000). This approach optimized the clinical applicability of our findings.

Quantitative studies were assessed using an adapted version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) tool for cohort studies (Public Health Resource Unit 2004). Because the question in this study is prognostic in nature, rather than related to treatment efficacy, several criteria were not relevant and were excluded. Questions that were open-ended were operationally defined so as to provide a yes or no answer. Our modification included 8 quality criteria (out of the original 12 CASP items): 1) Did the study address a clearly focused issue? 2) Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way? 3) Was the outcome accurately measured to minimise bias? 4) Have the authors identified all important confounding factors? 5) Have they taken account of the confounding factors in the design and/or analysis? 6) Was the follow up of subjects complete enough? 7) Was the follow up of subjects long enough? 8) How precise are the results (e.g., do they report confidence intervals, standard errors, or standard deviations?).

Qualitative studies were assessed using the CASP tool for Qualitative Research (Public Health Resource Unit 2006), and included 9 quality criteria out of a possible 10. The tenth question, “How valuable is the research”, was subjective and multidimensional. As a result, it was not included as a specific criterion. The nine CASP quality criteria included in this study were: 1) Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? 2) Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? 3) Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? 4) Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? 5) Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? 6) Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? 7) Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? 8) Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? 9) Is there a clear statement of findings? The CASP tools assess the rigor and validity of the included studies and have been used in previous systematic reviews involving participants with communication disorders (Hilari et al. 2012, Northcott et al. 2016).

Given the heterogeneous nature of the studies such as participant populations, measures used, study aims, and methods used, it was not possible to perform a formal meta-analysis of results from the quantitative studies. However, data from the qualitative studies were synthesized using a meta-ethnographic approach (Noblit and Hare 1998), performed by two independent reviewers (TE and CB). Specifically, while reading and re-reading the qualitative studies, we used thematic analysis to identify recurrent issues arising in the studies. We extracted quotes and other data related to the relationships between aspects of perceived social support and communication in each of the studies. These results were tabulated, and we developed a coding scheme to develop overarching concepts. Meta-ethnography was used to synthesize the data.

Results

Study Selection

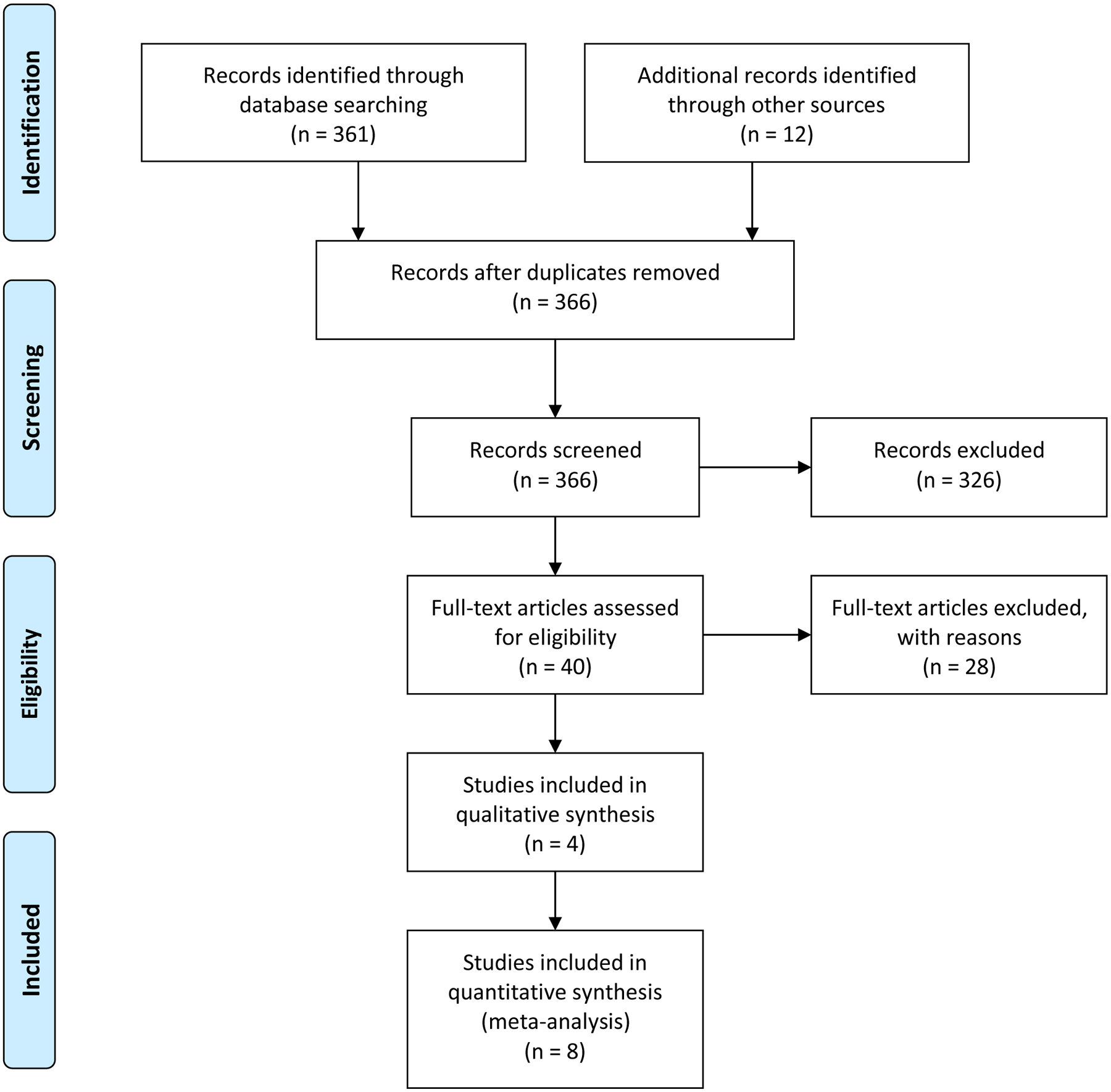

Electronic database searches resulted in 366 unique references. A flow diagram (see Figure 1) shows the reasons for exclusion at each stage. Twelve of these studies met eligibility criteria, including 8 quantitative and 4 qualitative studies. The authors of Hilari (2011) and Northcott and Hilari (2013) (one dataset), and Zahodne et al. (2009) provided additional analyses for these quantitative studies to meet inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the review process

Quantitative Studies

Quality criteria.

Eight quantitative studies were included in the review, representing 6 independent datasets (i.e., there were two aphasia datasets that each were used in two published studies). All 8 of the quantitative studies met 8 of 8 quality criteria for cohort study design, such as subject recruitment, minimising bias, controlling for confounding factors, and follow up.

Characteristics and findings.

Characteristics and relevant findings of the included quantitative studies are reported in Table 2. Included studies were diverse in research design (e.g., 5 cross-sectional and 3 longitudinal/repeated measures), and populations (4 stroke/aphasia (2 datasets), 2 PD, 1 MS, 1 HNC). Of the 6 datasets, outcome measures also were diverse. Three different PROs related to communication were used. In two datasets (4 studies) involving patients with aphasia, patient-reported communication was measured using the 7-item communication subdomain of the SAQOL-39 (Hilari et al. 2003). For two studies involving participants with PD, the 3-item communication subdomain of the Parkinson’s Disease QOL questionnaire (PDQ-39; Peto et al.1995) was used. For the other two studies (1 MS and 1 HNC), the Communicative Participation Item Bank (Baylor et al. 2013) was used. Perceived social support also was measured using three different questionnaires, including the Medical Outcomes Studies Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS; Sherbourne and Stewart 1991) in 4 studies (2 datasets in aphasia), the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al. 1988) in 2 studies (1 MS and 1 HNC) and the 3-item social support domain of the PDQ-39 (Peto et al. 1995) in 2 studies (2 PD). Due to this heterogeneity, meta-analysis was not possible, and a descriptive synthesis was provided.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Quantitative studies

| Included report | Loc | Diagnosis and time since diagnosis or other symptoms | N | Research topic | Research design | Perceived Social Support measure | Patient-reported communication outcome | QC | Relationship between perceived social support and communication measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hilari et al. 2003 | UK | Aphasia (stroke); all were at least 1 year post-stroke (mean = 3.5 years) | 83 | To adapt the Stroke-Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS-QOL) for use with people with aphasia, producing the Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale (SAQOL-39). | Cross-sectional, interview-based psychometric study |

Medical Outcomes Studies Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS) | Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life-39 (SAQOL-39) communication subdomain | 8/8 | Pearson’s r = .08 |

| McComb and Tickle-Degnen 2006 | US | Parkinson’s Disease; median time since initial diagnosis = 5.2 years; all moderate severity | 19 (plus CGs) | To determine the convergence between self-report and caregiver report of social support and quality of life; To determine relationships between perceived social support and quality of life domains. | Cross-sectional, survey-based study | Parkinson Disease Questionnaire-39 social support subscale (3 items) | Parkinson Disease Questionnaire −39 communication subscale (3 items) | 8/8 | For patient group only: Spearman’s rho = .06, p > .05 |

| Hilari and Northcott 2006 | UK | Aphasia (stroke); all at least 1 year post-stroke (mean = 3.5 years) | 83 | To determine the relationship between social support and quality of life in people with aphasia following stroke. | Cross-sectional, interview-based survey study | Medical Outcomes Studies Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS) | Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life-39 (SAQOL-39) communication subdomain | 8/8 | Spearman’s rho = .02, p = .84; Pearson’s r = .08, p = .49 |

| Zahodne et al. 2009* | US | Parkinson’s Disease; median time since diagnosis, STN = 162 months; GPi = 148 months | 42 (n=20, STN; n=22, GPi) | To compare the effects of unilateral DBS in the subthalamic nucleus (STN) vs. globus pallidus (GPi) on various domains of quality of life. | Randomized clinical trial, measured pre-DBS and 6 months post-DBS | Parkinson Disease Questionnaire-39 social support subscale (3 items) | Parkinson Disease Questionnaire-39 communication subscale (3 items) | 8/8 | STN, Pre-DBS: Pearson’s r = .232, p > .05; Post-DBS: Pearson’s r = .466, p < .038 GPi, Pre-DBS: Pearson’s r = .400, p = .065; Post-DBS: Pearson’s r = .424, p = .049. Total group, Pre-DBS: Pearson’s r = .334, p = .031; Post-DBS: Pearson’s r = .448, p = .003. |

| Baylor et al. 2010 | US | Multiple Sclerosis, mean duration of MS symptoms = 13.13 years | 498 | What self-report variables are most strongly related to communicative participation in a sample of adults with MS? | Cross-sectional (measured at a single time point as part of a larger longitudinal, survey-based study) | Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Communicative Participation Item Bank (CPIB), 25 item short form | 8/8 | Pearson’s r = .281, p < .01. MSPSS also entered into the final regression model as a significant predictor. |

| Hilari, 2011* | UK | Stroke (with and without Aphasia), adults with first ever stroke | 87 (n = 32 with aphasia; n=55 without aphasia); at 3 months, n = 14 with aphasia; n = 62 without aphasia; at 6 months, n = 11 with aphasia; n = 60 without aphasia) | What are the stroke outcomes in people with aphasia vs. those without, including activities of daily living, social support, psychological distress, and health-related quality of life? | Longitudinal, repeated measures study, measured at baseline (within 2 weeks of stroke), 3 months, and 6 months post-stroke | Medical Outcomes Studies (MOS) Social Support Survey (SSS) | Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life −39 (SAQOL-39) communication subscale | 8/8 | Control (no aphasia) group, baseline: Spearman’s rho = 0.148, p = .286; Pearson’s r = .158, p = .254; Aphasia group, baseline: Spearman’s rho = −.013, p = .942; Pearson’s r = .061, p = .738 Control (no aphasia) group, 3 months: Spearman’s rho = .108, p = .411, Pearson’s r = .227, p = .081; Aphasia group, 3 months: Spearman’s rho = .557, p = .048, Pearson’s r = .620, p = .024 Control (no aphasia) group, 6 months: Spearman’s rho = .236, p = .069, Pearson’s r = .358, p = .005; Aphasia group, 6 months: Spearman’s rho = .468, p = .172, Pearson’s r = .653, p = .041 |

| Northcott and Hilari 2013* | UK | Stroke (with and without Aphasia), adults with first ever stroke | 87 | To develop a new patient-reported measure of social network functioning that is specific to stroke, and is valid and acceptable for those with and without aphasia. | Repeated measures psychometric study; see Hilari, 2011 above. | Medical Outcomes Studies Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS) | Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life −39 (SAQOL-39) communication subscale | 8/8 | Same dataset as Hilari 2011. See results above. |

| Eadie et al. 2018 | US | Head and neck cancer, mean time since diagnosis = 12.2 years | 88 | To examine the contribution of psychosocial factors on communicative participation in adult survivors of HNC. | Cross-sectional survey study | Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Communicative Participation Item Bank (CPIB) short form | 8/8 | Pearson’s r = 0.22, p < .05. MSPSS did not enter as a significant unique predictor in final regression model. |

Note.

Denotes a study in which secondary (post-hoc) analyses were provided by the authors. Loc = location; N = sample size; QC = quality criteria; CG = caregiver

Of the 8 studies, weak (r < .20), non-significant relationships were found between measures of perceived social support and PROs related to communication in 3 studies (2 aphasia with one dataset: Hilari et al. 2003, Hilari and Northcott 2006; 1 PD: McComb and Tickle-Degnen 2006). Perceived social support was a weak (r < .30), but significant predictor of patient-reported communication outcomes in 2 studies (1 MS: Baylor et al. 2010, 1 HNC: Eadie et al. 2018). In all three studies that used a repeated measures/longitudinal design (1 PD: Zahodne et al. 2009, 2 aphasia with one dataset: Hilari, 2011, Northcott and Hilari, 2013), relationships were initially weak, but became moderate (rs > .40) and significantly stronger over time. In PD, relationships strengthened after treatment with deep brain stimulation in individuals who were on average 12 to 13.5 years post-diagnosis. Two studies (one dataset) included those without and with aphasia (Hilari 2011, Northcott and Hilari 2013). Participants were assessed at baseline, 3 months and 6 months post-stroke. Relationships between perceived social support and self-reported communication remained consistently weak in the control group (i.e., non-aphasia group) over time. The relationship also was initially weak in those with aphasia at baseline. Relationships became significantly stronger over time only in the group with aphasia (ranging between r = .557–.653 at 3 and 6 months, respectively; see Table 2).

Qualitative Studies

Quality criteria.

Four qualitative studies were included in the review. Overall qualitative methodology was deemed appropriate in all four studies. For the four included studies, one study (25%) met all nine quality criteria; the remaining three studies met three, seven, and eight quality criteria, respectively. Details related to the critical appraisal are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Quality assessment of qualitative studies of perceived social support and patient-reported communication outcomes.

| Criteria | Bringfelt et al. 2006 | Dalemans et al. 2010 | Swore Fletcher et al. 2012 | Natterlund 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell |

| Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell |

| Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell |

| Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | No |

| Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | No |

| Is there a clear statement of findings? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

Characteristics and findings.

Characteristics of the included studies, major themes, and quotes supporting relationships between perceived social support and communication are presented in Table 4. Included studies were diverse in research designs (e.g., 3 consistent with phenomenology, 1 descriptive), and populations (1 HNC, 2 aphasia, 1 MS).

Table 4.

Characteristics of qualitative studies.

| Included report | Diagnosis and time since diagnosis or other symptoms | Purpose statement | Grand tour question | N | Methodological orientation | QC | Major themes | Quotes or themes illustrating relationship between social support and communication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bringfelt et al. 2006 | Multiple sclerosis, mean time since disease onset = 39 years; all had clinical signs of dysarthria | 1) To reinvestigate the speech of a selected subgroup of individuals with MS included in Hartelius et al … and 2) to interview these individuals about their experiences of living with MS. | “As a starting point, the participant was encouraged to describe a typical day and discuss communication in relation to his or her activities and encounters during the day.” | 18 | Phenomenology; semi-structured interview | 8/9 | Barriers (intrapersonal and extrapersonal); Facilitating factors (intrapersonal, extrapersonal, and professional assistance) |

Facilitator: E.g., “Neighbors that knew about her condition facilitated participation in social interaction outside her home.” Barrier: E.g., One participant “seemed to experience considerable restrictions and frustrations regarding interpersonal interaction and communication, despite facilitating factors such as a supportive and loving daughter and two friends who visited regularly” |

| Dalemans et al. 2010 | Aphasia (stroke), mean time post onset = 5.1 years | To explore how people with aphasia perceive participation in society and to gain insight into the perceived influencing factors. | “What do you do on a regular day?” | 13 (plus 12 CGs) | Consistent with phenomenology | 9/9 | Perceived engagement in social participation; Influencing factors (personal, social, and environmental) |

Facilitator: e.g., “The central caregiver played an important role. Often they stimulated the person with aphasia to take part, organized meetings with friends, stayed in the background so people would talk to the person with aphasia as well, and gave tips to communicative partners.” Barrier: e.g., “There were also central caregivers who had the habit of taking over… [and] had the tendency to overprotect, excluding the person with aphasia…” |

| Natterlund 2010 | Aphasia (stroke or traumatic brain injury), mean time post onset = 6.52 years | To describe aphasic individuals’ experiences of everyday activities and social support in daily life. | “The interviews covered the participants’ own experiences of everyday activities and social support in daily life.” | 20 | Descriptive | 3/9 | Life situation today; Social support in daily life; Social life at present |

Facilitator: e.g., “It was of great value to have a relative supporting them with their speech.” Barrier: e.g., “Participants experienced a lack of support from the healthcare system and they wanted more support”. |

| Swore Fletcher et al. 2012 | Head and neck cancer, range = 2 to 24 months post-treatment for HNC | To explore survivors’ experience of communication during and after treatment for HNC. | “What was it like communicating during the treatment phase?” and “What have you learned from the experience?” | 39 | Phenomenology; descriptive, and interpretive | 7/9 | Change in communication; Going deeper into life |

Facilitator: e.g., One participant said about his friends: “it’s not me reaching out, but them reaching in” that affected his communication opportunities. Barrier: e.g., Sometimes family members of those with HNC “just want to go away a little bit, and.. the usual person is feeling that loss… the loss of their usual mate or their usual amount of talking or communication”. |

Note: N = sample size; CG = caregiver; QC = quality criteria.

Although the qualitative studies did not directly study the specific questions posed in this review, relevant findings emerged in subthemes and quotes that enabled synthesis of the findings. Two overarching themes were identified. First, aspects related to perceived social support were found to facilitate better communication outcomes; this was reported in all four studies (Bringfelt et al. 2006, Dalemans et al. 2010, Natterlund et al. 2010, Swore Fletcher et al. 2012). A second theme revealed how misguided or absent social support also acted as barriers of communication outcomes; this was reported in all four studies (Bringfelt et al. 2016, Dalemans et al. 2010, Natterlund et al. 2010, Swore Fletcher et al. 2012).

Social support as facilitators of communication.

A prevailing theme throughout all of the studies was that aspects of perceived social support were facilitators of better communication outcomes. The types of perceived social support that facilitated communication outcomes included the perceived availability of emotional support (e.g., expressions of caring), belonging support (e.g., knowing others are available to engage in social activities), and informational support (e.g., availability to provide advice and guidance, if needed). For example, Swore Fletcher and colleagues’ (2012) investigation of HNC survivors’ experiences revealed that different types of supportive relationships acted as facilitators for adaptations in communication. One participant reported that perceived emotional support resulted in better communication with his wife:

…adapted to what I was going through… She would sit there and whisper to me… And I told her that you don’t have to whisper because I can’t talk, and she goes, ‘I know but if you can’t be loud, then I’m not going to be loud.’ So call it what you want, call it support, call it love. I just know that she was a strong support structure, a strong support in my life that helped me get through what I had to get through.

(Swore Fletcher et al. 2012, p. 130)

Likewise, in a study involving participants with MS, Bringfelt et al. (2006) concluded that “even in cases where communicative impairment was mild or absent…. participants described communication as being facilitated by extrapersonal (relationships with family, friends, and neighbors) factors” (p. 138). However, even when there was strongly perceived social support, participants were not always able to overcome restrictions in communication caused by their impairments. For example, one participant with moderate-severe dysarthria as well as language and cognitive impairments secondary to MS experienced communication restrictions in spite of reporting positive support from a daughter and two friends as facilitating factors.

Natterlund (2010) also showed that different types of perceived social support facilitated positive communication outcomes in people with aphasia. Participants said that they often asked their partners to help them with communicative interactions, at times talking for them. A few reported that close relatives supported them with language training at home, and felt “that it was of great value to have a relative supporting them with their speech” (p. 122). Similarly, Dalemans and colleagues (2010) identified the support of caregivers as facilitating communication. One facilitating technique, a form of informational support, involved giving tips to unfamiliar communication partners to ensure successful communication with the person with aphasia. Dalemans et al. (2010) best summarises how perceived social support could enable communication success for a person with a communication disorder:

a motivated person with aphasia living with a stimulating caregiver in a quiet accessible environment with willing people surrounding him, who have knowledge and skills to adapt to the communicative possibilities of the person with aphasia, have [sic] a better chance to achieve engagement.

(Dalemans et al. 2010, p. 546)

Failed or absent social support as barriers to communication.

While the section above describes how the presence of perceived social support could improve communication experiences, participants in all four of the studies reported how failed or absent attempts of perceived social support also acted as barriers to communication outcomes. In their study of individuals with aphasia, Dalemans et al. (2010) reported that caregivers could act as barriers by taking over conversations and overprotecting the person with aphasia. While the caregivers might have had the good intent of saving the person with aphasia the struggle of talking, this misguided effort had the undesirable outcome of minimizing participants’ opportunities to communicate. Other examples of lack of social support included not involving individuals with aphasia in conversations at all.

Barriers also were identified as stemming from the perception of other people’s negative behaviors and attitudes, which in turn affected communication. In some cases, these attitudes even extended to family members. Bringfelt et al. (2006) stated that one participant did not report many communication difficulties due to MS, but that troublesome interpersonal interactions with her children led to limited communication opportunities. A similar barriers involving family members was reported by one participant with HNC (Swore Fletcher et al. 2012). Negative reactions extended beyond family and friends. One participant with MS noted that she avoided social contacts because of negative attitudes of unfamiliar communication partners. Finally, Natterlund (2010) reported that some participants in their study with aphasia reported a perceived lack of support from specific domains in society where they had hoped and expected to find it, such as from healthcare providers..

Discussion

This systematic review explored relationships between perceived social support and patient-reported communication outcomes in adults with communication disorders. The information revealed using both quantitative and qualitative approaches is important for interpreting the clinical significance of the findings, as well as providing directions for future research.

Integrating Results from the Quantitative and Qualitative Studies

In this study, different patterns of results were revealed when relationships between perceived social support and communication outcomes were investigated using quantitative versus qualitative methods. Five of 8 quantitative studies included in this study showed no or weak relationships, regardless of the patient populations or the PRO measures used. Moderate relationships were demonstrated in three longitudinal quantitative studies that included two datasets. In contrast, results from the four included qualitative studies, although somewhat limited by poor quality, suggested that presence of perceived social support acted as a facilitator for communication, whereas misguided or absent social support posed barriers to communication outcomes. Skillful, responsive family members and friends were able to facilitate better quality of communicative interactions, while lack of support or negative attitudes and behaviours of other people acted as barriers to satisfactory interactions.

One possible explanation for the different conclusions drawn from the quantitative and qualitative studies might relate to the different types, or the specific combinations of PRO measures used for assessing perceived social support and/or communication in the quantitative studies. Of the 8 included quantitative studies (6 datasets), there were three different measures of perceived social support, and three different PRO measures of communication (see Table 2). As described in the methods, any type of PROs related to communication were included. The measures captured different aspects of communication including participants’ reports of their own communication abilities, their experiences of communication in daily activities, or their emotions and feelings. Further, the items on the social support questionnaires also might not have captured the specific types of supportive behaviors that participants in the qualitative studies identified as being helpful (or not) for communication. As stated by Natterlund (2010), people with aphasia (and we would suggest other types of communication disorders as well) require “different kinds of social support, to help them manage their aphasia and to improve their participation in society” (p. 127). Thus, one significant barrier to measuring a possible connection between perceived social support and communication outcomes might be the availability and/or selection of instruments that are most sensitive for capturing these relationships.

Another factor that could have affected the quantitative results might relate to the time post-diagnosis and/or the time point at which participants were assessed. One interesting pattern that emerged in the quantitative studies was that the weakest relationships (r values ranging from .08 to .28; see Table 2) were noted in cross-sectional studies with participants who were on average many years post-diagnosis and/or who had lived with their symptoms for many years. Participants in these studies were on average 3.5 to 13.3 years post-diagnosis: they had many years to adapt to their health condition or consequences of treatment, including changes to their social environment and communication.

Among the three quantitative studies that used repeated measures (two datasets), relationships between perceived social support and patient-reported communication success started as weak, but strengthened and became moderate over time. Two studies (one dataset) included those with and without aphasia (Hilari 2011, Northcott and Hilari 2013). Relationships between perceived social support and self-reported communication remained consistently weak in the control group over time. However, relationships became significantly stronger over time in the group with aphasia, suggesting that it was not the repeated measures design that was critical for capturing these changes, but that it was the assessment of these constructs during a relatively unstable, stressful, and changing period of time that was important. Although these findings are interesting, small sample sizes, especially at follow up, warrant caution in interpretation.

One study by Zahodne et al. (2009) also revealed increasingly strong relationships between perceived social support and communication outcomes in a repeated measures design. Unlike the longitudinal studies involving participants with aphasia, participants in the study by Zahodne et al. (2009) were on average 12 to 13.5 years post-PD diagnosis. Similar to the results from cross-sectional studies involving participants who also were many years post-diagnosis, relationships between perceived social support and communication were initially weak. Yet, 6 months after the participants underwent deep brain stimulation, relationships between perceived social support and communication were revealed to be stronger. In other words, acute changes from surgery, even among individuals who had lived with PD a long time, affected relationships between the measures. Caution is warranted in interpreting these data, as both measures (perceived social support and communication) are based on subscales on the PDQ-39 with only 3 items. Yet, taken together, results from the quantitative studies might lead us to question whether PROs of communication or perceived social support are differentially affected by time and adaptation to a condition.

In contrast to the quantitative studies, results from the qualitative studies more consistently revealed relationships between perceived social support and communication outcomes, regardless of the patient populations. All studies included themes related to how supportive family and friends could facilitate better communication outcomes (Bringfelt et al. 2006, Dalemans et al. 2010, Natterlund 2010, Swore Fletcher et al. 2012). Interestingly, these positive aspects of perceived social support appear to be included in all of the reviewed PRO measures of perceived social support. While not specifically related to communication per se, the positive influence of social support has been identified as highly valued by people with communication disorders (Baylor et al. 2011, Northcott et al. 2015). Beyond family and friends, Swore Fletcher et al. (2012) and Natterlund (2010) also reported that people with communication disorders might look to other people, such as healthcare providers, as sources of perceived social support. While beyond the scope of this investigation, the effect of the clinician-patient therapeutic relationship on communication outcomes also appears to be a direction for future study.

Importantly, results from the qualitative studies consistently reported that other people could be barriers to communication success. Some family members took over new roles and “over-controlled” the person with the communication disorder. In other cases, barriers arose from impatient attitudes and behaviours of both familiar and unfamiliar communication partners, or from lack of support altogether (Bringfelt et al. 2006, Dalemans et al. 2010). Social strain, lack of social support, and poor overall relationship quality have been shown to be risk factors for depression in otherwise healthy populations (Teo et al. 2013). Likewise, negative aspects of social support, as well as changing roles and the inability of partners to adapt to these changes, frequently arise when individuals experience a change in health status, and negatively impact health outcomes (Northcott et al. 2015). Acknowledgment of these barriers needs inclusion among quantitative measures of perceived social support; exclusion of these factors among current PRO measures is an obvious gap, which may have significantly affected the results of this study. However, before proposing directions for future research and clinical practice, we first need to understand the underlying mechanisms that describe the pathways between perceived social support and health outcomes that go beyond communication.

Proposed Mechanisms of Perceived Social Support

One of the most influential models relating perceived social support to PRO measures such as health-related QOL was proposed by Cohen and Wills (1985). They suggest that perceived social support is associated with good mental and physical health through two models: a) stress buffering, in which social support reduces stress, which thereby has a positive impact on health and well-being and; b) the direct pathway model, whereby social support directly impacts health and well-being. Cohen and Wills (1985) provide examples for these models. In the stress-buffering scenario, a person experiences a stressful event: an event that is appraised by an individual as threatening or demanding and for which the person does not have an appropriate coping response. In this model, the perception that others can and will provide necessary resources or emotional support may redefine the potential for harm. In fact, perceived social support in this model can even prevent a stressful response in the first place, which some authors have proposed as a separate (third) stress prevention pathway for affecting health outcomes (Holt-Lunstad and Uchino, 2015). However, even if the individual does experience stress, Cohen and Wills (1985) suggest various mechanisms by which perceived social support, in particular informational and emotional support, may alleviate this stressful response, and reduce the impact of stress on health. In contrast, in the direct effect model, Cohen and Willis (1985) describe a scenario in which a person is not experiencing acute stress. In this scenario, they hypothesize that the person will benefit most from social networks (i.e., a form of structural support), and that a large social network will promote a sense of social integration, which will directly lead to well-being.

The Cohen and Wills (1985) models are useful for interpreting results from the present study. Relationships between measures of perceived social support and PRO communication measures were most strongly observed in quantitative studies that measured changes in individuals over a period of time in which there was a stressful event. This occurred in studies involving participants who were acutely adapting to their stroke (Hilari 2011, Northcott and Hilari 2013), and in individuals who had lived a long time with PD symptoms, but who had also recently undergone surgery (Zahodne et al. 2009). Consistent with the stress buffering model, one might predict that measures of perceived social support would be most sensitive to outcomes such as communication while a person is undergoing a stressful event such as undergoing a medical treatment or adapting to a newly diagnosed health condition.

In contrast, results from quantitative studies with cross-sectional designs that included participants who had lived many years with their diagnosis or symptoms showed no to weak relationships. These results also are consistent with what might be predicted by Cohen and Wills (1985) models. If individuals have adapted and are not experiencing acute stress (i.e., as in the direct pathway model), Cohen and Wills postulate that integration in social networks (or lack thereof) most strongly affects outcomes. It therefore begs the question as to whether social network measures (i.e., measures of structural social support) might have been more sensitive in capturing aspects related to social support than measures of perceived social support in quantitative studies with participants who had lived many years with their condition.

Interestingly, all four qualitative studies included participants who had lived many years with their diagnoses, although some participants continued to experience changes in their symptoms (e.g., those with MS; Bringfelt et al. 2006). Yet, in all four of these studies, participants were asked to reflect back on a time of stress and change (e.g., pre- to post-stroke; during HNC treatment). As a result, it is difficult to assess how the Cohen and Wills models relate to results from the qualitative studies. Future study is needed to address these relationships.

Future Directions and Limitations

The hypothesis that different types of social support measures may be more or less sensitive at different times of recovery (or at different times post-diagnosis) needs testing in future longitudinal research. This hypothesis contrasts with measures of actual or received social support, which have not been consistently linked to better patient-reported outcomes such as emotional health (Barrera, 1986, Uchino, 2009, Wills and Shinar, 2000). Also relevant is recent evidence suggesting that the Cohen and Wills (1985) models may need modification. For example, functional support may directly facilitate better mental health, even in individuals who are not experiencing acute stress (Holt-Lundstad and Uchino 2015). Thus, future research needs to determine how factors beyond stress, including personal factors, also might mediate outcomes related to social support.

Further research, including qualitative approaches, should also help determine which measures might best meet our needs for assessing social support and communication, as well as how we might better define these constructs among individuals with communication disorders. To provide stronger evidence for interventions, which factors to consider, as well as determining the strength of relationships among variables, it is recommended that standardized measures be used.

Finally, results from this study support the contention that perceived social support is among a variety of factors that affect patient-reported communication success in adults with communication disorders. In addition to perceived social support, factors include disorder severity, other environmental influences, and personal factors (e.g., coping responses). All of these variables have been found to affect communication outcomes in different populations, and all need further study (Baylor et al. 2017, Baylor et al. 2010, Hilari et al. 2012, McAuliffe et al. 2016, Yorkston et al. 2001).

Several limitations to this study need to be addressed. First, while the search strategy used in this review was comprehensive with a wide-ranging search of electronic databases supplemented by hand-searches of the reference lists, the review included only studies written in English. Relevant studies in other languages may have been excluded. Second, very few studies met the inclusion criteria, making generalisation of the results difficult. In addition, half of the included studies (quantitative and qualitative) included participants with aphasia. Because of the difficulty of using PROs and performing qualitative interviews with people with severe aphasia, it is possible that the results from this study were limited due to the exclusion of these participants. Third, the heterogeneity in patient populations, time scales and follow-up, and outcome measures make between-study comparisons and overall conclusions difficult. This was the reason a meta-analysis of the quantitative studies was not possible. In addition, some of the patient-reported subscales (and scores) consisted of only three items (e.g, PDQ-39), whereas others were based on more comprehensive total scores (e.g., MOS-SSS, MSPSS). Clearly, a broader battery of psychometrically rigorous tools to measures various aspects of social support is needed. Fourth, only one of the qualitative studies met all nine quality criteria; the remaining three studies met three, seven, and eight quality criteria, rendering results from at least one of these studies somewhat questionable. This selection approach was deliberate, as inclusion criteria that were more narrowly defined may have severely limited the clinical applicability of the results. However, readers must be cautioned about these limitations when considering the qualitative results. Finally, this systematic review was prognostic; thus, relationships that were observed cannot be interpreted as causal. However, many implications may still be derived for future practice.

Clinical Implications

Determining the specific effect of perceived social support on communication outcomes is important for identifying targets for intervention in individuals with communication disorders. For these interventions to be effective, we need to consider contextual factors that underlie or affect perceived social support: stress-related factors that may affect the efficacy of support, support provider factors and characteristics, and support recipient factors. As support providers, we need to continue to include families and caregivers in all stages of the experience of a communication disorder for all patient populations. In the stroke literature, it has been shown that while the support of family remains relatively constant post-stroke, people are at risk of losing contact with friends and social activities, particularly in adults with aphasia (Kruithof et al. 2013, Northcott et al. 2015). In addition, while family support may remain relatively constant, the role of family members changes and may create disharmony in the family unit. As clinicians and researchers, we must consider the role of both positivity and negativity in these relationships. For example, interventions solely aimed at increasing social support may have detrimental effects if they do not account for negativity in relationships and responsivity of the provided support. Northcott et al. (2015) suggest that to safeguard the quality of the support of family “despite the strain of caregiving, it is arguably important to consider the family during rehabilitation, and explore family or couple-orientated interventions” (p. 18) in people with aphasia. Results from the present study show similar findings in those treated for HNC, as well as those diagnosed with MS and PD, with implications for rehabilitation in all of these populations.

There is also a growing body of evidence for the positive impact of intervention focusing on social support, which has implications for SLTs. In addition to families and caregivers, involvement with others with similar health conditions (e.g., either through formal group therapy or patient-oriented support groups) continues to be a powerful option that needs more evidence. These approaches are important because while SLTs often provide practical help and informational support, group therapy or support groups may provide other types of support such as emotional support, which may be the strongest predictor of better health-related QOL outcomes (Kruithof et al. 2013). Whether the medium (e.g., face to face vs. online) or characteristics of the support recipients (e.g., age or sex) also affect these outcomes needs future study. If confirmed, these factors may serve as important targets of future clinical practice.

Conclusions

Results from this study show preliminary evidence that perceived social support is related to patient-reported communication outcomes in adults with communication disorders, with similar results demonstrated across patient populations. Perceived social support was found to act as a facilitator to communication success, whereas the lack of support, or misguided attempts at social support served as barriers to communication success. Yet, formal measures of perceived social support may not adequately capture this construct, and may be more or less sensitive at different points of recovery, treatment, or course of a disease. Barriers to communication such as negative attitudes and behaviours of others also do not appear to be included in formal measures of perceived social support. As such, SLTs need to exercise caution when selecting formal measures of perceived social support for assessing these effects in research and clinical practice in those with communication disorders. Further research is needed for determining any causative factors relating to communication outcomes, as well as the strength of these relationships, and for determining future targets for intervention in these patient populations.

What this paper adds.

What is already known about this subject?

Increased perceived social support has been shown to positively relate to health-related quality of life outcomes in adults with communication disorders; yet, its effect on patient-reported outcomes related to communication is not well established. The lack of research evidence about these relationships makes it difficult to develop and recommend intervention approaches that may include factors related to perceived social support.

What this paper adds?

This systematic review addresses a gap in the literature by considering how perceived social support, assessed using formal patient-reported measures in quantitative studies and themes derived from qualitative studies, relates to patient-reported communication outcomes in adults with communication disorders. It expands on previous studies that have focused on relationships within particular disorder groups. The results reveal that while perceived social support may act as a facilitator and a barrier to communication outcomes, current measures of perceived social support may not adequately capture this construct.

Clinical implications?

Caution should be exercised when selecting formal measures of perceived social support as outcome measures in research and clinical practice related to communication disorders. Clinicians should consider factors related to perceived social support as both facilitators and barriers to communication success when developing future intervention approaches.

Footnotes

Note: Portions of this paper were presented at the Annual Meeting on Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) in June 2017 in Washington DC, and at the Annual Convention of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association in November 2017 in Los Angeles, CA.

Declaration of Interests: Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number [R01CA177635 PI: Eadie]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- AWAN SN, ROY N, and COHEN SM, 2014, Exploring the relationship between spectral and cepstral measures of voice and the Voice Handicap Index (VHI). Journal of Voice, 28(4), 430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRERA M, 1986, Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14(4):413–445. [Google Scholar]

- BAYLOR C, AMTMANN D, and YORKSON KM, 2012, A longitudinal study of communicative participation in individuals with Multiple Sclerosis: Latent classes and predictors. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 20(4), 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- BAYLOR C, BURNS M, EADIE T, BRITTON D, and YORKSTON K, 2011, A qualitative study of interference with communicative participation across communication disorders in adults. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(4), 269–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAYLOR C, OELKE M, BAMER A, HUNSAKER E, OFF C, WALLACE SE, PENNINGTON S, KENDALL D, and YORKSTON K, 2017, Validating the Communicative Participation Item Bank (CPIB) for use with people with aphasia: an analysis of differential item function (DIF). Aphasiology, 31(8), 861–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAYLOR C, YORKSTON K, BAMER A, BRITTON D, and AMTMANN D, 2010, Variables associated with communicative participation in people with multiple sclerosis: a regression analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19(2), 143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAYLOR, YORKSTON K, EADIE T, KIM J, CHUNG H, and AMTMANN D, 2013, The Communicative Participation Item Bank (CPIB): Item bank calibration and development of a disorder-generic short form. Journal of Speech, Language, & Hearing Research, 56(4), 1190–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOYLE MP, 2015, Relationships between psychosocial factors and quality of life for adults who stutter. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRINGFELT P-A, HARTELIUS L, and RUNMAKER B, 2006, Communication problems in multiple sclerosis: 9-year follow up. International Journal of MS Care, 8, 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- COHEN S, and Wills TA, 1985, Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological bulletin, 98, 310–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONSTANTINESCU G, RIEGER J, WINGET M, PAULSEN C, and SEIKALY H, 2017, Patient perception of speech outcomes: The relationship between clinical measures and elf-perception of speech function following surgical treatment for oral cancer. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26(2), 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRUICE M, WORRALL L, HICKSON L, and MURISON R, 2005, Measuring quality of life: Comparing family members’ and friends’ ratings with those of their aphasic partners. Aphasiology, 19(2), 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- DALEMANS RJ, DE WITTE L, WADE D, and VAN DEN HEUVEL W, 2010, Social participation through the eyes of people with aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 45(5), 537–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DONOVAN NJ, KENDALL DL, YOUNG ME, and ROSENBEK JC, 2008, The communicative effectiveness survey: preliminary evidence of construct validity. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(4), 335–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOYLE PJ, MCNEIL MR, MIKOLIC JM, PRIETO L, HULA WD, LUSTIG AP, ROSS K, WAMBAUGH JL, GONZALEZ-ROTHI LJ, and ELMAN RJ, 2004, The Burden of Stroke Scale (BOSS) provides valid and reliable score estimates of functioning and well-being in stroke survivors with and without communication disorders. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 57(10), 997–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EADIE T, FAUST L, BOLT S, KAPSNER-SMITH M, HUNTING POMPON R, BAYLOR C, FUTRAN N, and MENDEZ E, 2018, The role of psychosocial factors on communicative participation in head and neck cancer survivors. Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery. doi: 10.1177/0194599818765718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- EADIE TL, YORKSTON KM, KLASNER ER, DUDGEON BJ, DEITZ JC, BAYLOR CR, MILLER RM, and AMTMANN D, 2006, Measuring communicative participation: a review of self-report instruments in speech-language pathology. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15(4), 307–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLASS GV (2000). Meta-anaysis at 25. Retrieved May 20, 2018 from http://www.gvglass.info/papers/meta25.html

- HILARI K, 2011, The impact of stroke: are people with aphasia different to those without? Disability and Rehabilitation, 33(3), 211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILARI K, BYNG S, LAMPING DL, and SMITH SC, 2003, Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale-39 (SAQOL-39): evaluation of acceptability, reliability, and validity. Stroke, 34(8), 1944–1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILARI K, NEEDLE JJ, and HARRISON KL, 2012, What are the important factors in health-related quality of life for people with aphasia? A systematic review. Archives of [DOI] [PubMed]

- HILARI K, and NORTHCOTT S, 2006, Social support in people with chronic aphasia. Aphasiology, 20(1), 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- HOLT-LUNSTAD J, SMITH TB, and LAYTON JB, 2010, Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLT-LUNSTAD J, and UCHINO BN, 2015, Social support and health In Glanz K, Rimer B, & Viswanath K (Eds.), Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; ), pp. 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- JACOBSON BH, JOHNSON A, GRYWALSKY C, SILBERGLEIT A, JACOBSON G, and BENNINGER MS, 1997, The Voice Handicap Index (VHI): Development and validation. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 6(3), 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- KARNELL LH, CHRISTENSEN AJ, ROSENTHAL EL, MAGNUSON JS, and FUNK GF, 2007, Influence of social support on health-related quality of life outcomes in head and neck cancer. Head & Neck, 29(2), 143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRUITHOF WJ, VAN MIERLO ML, VISSER-MEILY JM, VAN HEUGTEN CM, and POST MW, 2013, Associations between social support and stroke survivors’ health-related quality of life--a systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 93(2), 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIBERATI A, ALTMAN DG, TETZLAFF J, MULROW C, GOTZSCHE PC, IOANNIDIS JP, CLARKE M, DEVEREAUX PJ, KLEIJNEN J, and MOHER D, 2009, The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), W65–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCAULIFFE MJ, BAYLOR CR, and YORKSTON KM, 2016, Variables associated with communicative participation in Parkinson’s disease and its relationship to measures of health-related quality-of-life. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19(4), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCAULIFFE MJ, CARPENTER S, and MORAN C, 2010, Speech intelligibility and perceptions of communication effectiveness by speakers with dysarthria following traumatic brain injury and their communication partners. Brain Injury, 24(12), 1408–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCOMB MN, and TICKLE-DEGNEN L, 2006, Developing the construct of social support in Parkinson’s Disease. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 24(1), 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- NATTERLUND BS, 2010, A new life with aphasia: everyday activities and social support. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. doi: 10.1080/11038120902814416 [DOI] [PubMed]

- NOBLIT G, HARE R, 1998, Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies (London: Sage; ). [Google Scholar]

- NORTHCOTT S, and HILARI K, 2013, Stroke Social Network Scale: development and psychometric evaluation of a new patient-reported measure. Clinical Rehabilitation, 27(9), 823–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORTHCOTT S, MOSS B, HARRISON K, and HILARI K, 2016, A systematic review of the impact of stroke on social support and social networks: associated factors and patterns of change. Clinical Rehabilitation, 30(8), 811–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETO V, JENKINSON C, FITZPATRICK R, and GREENHALL R, 1995, The Development and Validation of a Short Measure of Functioning and Well-Being for Individuals with Parkinsons-Disease. Quality of Life Research, 4(3), 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PINQUART M, SORENSEN S, 2000, Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: a meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 15, 187–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUBLIC HEALTH RESOURCE UNIT, 2004, 12 questions to help you make sense of cohort study. Oxford, UK: Public Health Resource Unit. [Google Scholar]

- PUBLIC HEALTH RESOURCE UNIT, 2006, 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Oxford, UK: Public Health Resource Unit [Google Scholar]

- SHERBOURNE CD, and STEWART AL, 1991, The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine, 32(6), 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]