Abstract

Recent evidence showing degeneration of the noradrenergic system in the locus coeruleus (LC) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has motivated great interest in noradrenaline (NA) as a potential brain hallmark of the disease. Despite the current exploration of blood markers for AD, the deregulation of the plasma NA concentration ([NA]plasma) in AD is currently not well understood. This retrospective study includes a cohort of 71 patients (32 AD patients, 22 with other dementia and 17 without dementia) who were given consultations for memory complaints in the Cognitive Neurology Center of Lariboisière (Paris) between 2009 and 2014. As previously described in brain tissue, we show for the first time a linear correlation between [NA]plasma and Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score in AD patients. We observed that high [NA]plasma in AD patients was associated with higher [Aβ1–42]CSF than in other AD patients with [NA]plasma similar to NC patients. In parallel, we observed a lower (p-Tau/Tau)CSF in AD patients with low [NA]plasma than in non-AD patients with [NA]plasma similar to [NA]plasma in NC patients. Our data suggest that [NA]plasma could be a potential biomarker of disease evolution in the context of AD and could possibly improve early diagnosis.

Subject terms: Physiology, Molecular neuroscience

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia among adults over 65 years old and is characterized by progressive impairment in cognitive function and behavior1. The neuropathological hallmarks of the disease include amyloid plaques, formed by extracellular accumulation of amyloid β peptide (Aβ1–42) and neurofibrillary tangles, formed by intraneuronal aggregates of phosphorylated Tau protein p-181 (p-Tau)2. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) core biomarkers (Aβ1–42, p-Tau, and total-Tau), as well as amyloid and Tau positron-emission tomography, reliably reflect AD neuropathological brain lesions3,4, leading to their inclusion in research diagnostic criteria. However, acquiring these measurements is costly and invasive. In addition, CSF biomarkers are sometimes not sufficient to differentiate AD from other types of dementia, such as dementia with Lewy bodies5. Indeed, differential diagnosis remains a major challenge in clinical practice6. Thus, addressing the need to develop novel and inexpensive diagnostic techniques has become a focal point of Alzheimer’s research2.

The noradrenergic system and AD

Many studies have shown that the abnormal structure and function of noradrenergic neurons are closely related to AD pathophysiology6–8. The noradrenergic system plays pivotal regulatory roles in various behaviors, including selective attention, memory storage and retrieval, vigilance, and mood9. Most of the noradrenergic neurons in the CNS originate from the locus coeruleus (LC) and project to different areas of the brain, such as the cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, thalamus, and hypothalamus10. Hyperphosphorylation of Tau protein in the LC appears at an early stage of AD pathogenesis11, and the number of neurons in the LC has been shown to progressively decrease during the disease, beginning at the prodromal stage of AD8,12–17. Based on the current literature, one of the ideas that has emerged is that the onset of AD is preceded by abnormal hyperactivation of the LC, resulting in oversecretion of NA in the cortex18. The hyperactivation of noradrenergic receptors in the cortex leads to a cortical accumulation of Aβ1–42 plaques19. Following this accumulation, the dendritic spine density of noradrenergic neurons and noradrenaline (NA) secretion begin to decrease due to lack of stimulation and/or (glial) inflammatory processes18. However, this working hypothesis requires further research in this area and supporting evidence. NA is a catecholamine that acts as a neuromodulator when synthesized by noradrenergic neurons and as a hormone when synthesized by the sympathetic system. NA deregulation in AD was first identified at the end of the 1970s by Adolfsson et al., who showed that the NA concentration in postmortem brain tissue was lower in AD patients of ~75 years of age than in age-matched controls and correlated with dementia score20. Interestingly, a recent publication reported a correlation between the NA concentration in a specific cortical brain region of AD patients and MMSE score21. In addition, NA CSF levels in advanced AD patients differ from those in patients with mild to moderate severity and those in healthy older subjects22,23. These observations imply that cognitive decline could be timely correlated with coeruleo-cortical network deregulation and disconnection18. The early increase in neuronal NA secretion before the onset of AD that is later followed by noradrenergic neuron degeneration could be related to disease evolution11,24. At the peripheral level, NA circulates through the bloodstream and is known to be involved in the body response to acute stress by modulating, among other physiological parameters, heart rate, blood pressure, and muscle contraction25. Interestingly, the LC is known to regulate sympathetic activity26 by modulating postsympathetic noradrenergic neurons targeting the heart and blood vessels27. Different studies have shown that the plasma NA concentration ([NA]plasma) is altered in AD. Although these studies show conflicting results, it seems clear that AD pathophysiology is associated with modulations in [NA]plasma23,28–30.

Early stage of AD: CSF and plasma biomarkers

Investigations of potential treatments for AD have revealed the need to define and characterize an early stage of the disease, where therapeutic treatments could be the most effective. Recent studies have attempted to identify new biomarkers that can identify AD patients before the onset of advanced symptoms. The term mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was used for the first time in the 1980s to define patients at an intermediate stage between normal aging patients and patients with dementia31. Recently, the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) specified the state “MCI due to AD” to clearly identify a very early stage of this disease32. Among other clinical criteria33, CSF biomarkers are required in the determination of MCI due to AD, such as CSF Aβ1–42, total-Tau, and/or p-Tau concentrations32. Several studies in the literature have shown a significant difference in CSF Aβ1–4234–36, total-Tau35–39, and p-Tau37 concentrations between MCI and AD patients, describing a decrease in the CSF Aβ1–42 concentration ([Aβ1–42]CSF) and an increase in the CSF total-Tau and p-Tau concentrations ([Tau]CSF and [p-Tau]CSF) in AD patients. However, these differences are not always statistically significant for CSF Aβ1–4237,40, total-Tau34,40, and p-Tau34,35,39,40. A higher CSF p-Tau/total Tau ratio ((p-Tau/Tau)CSF) (or lower (Tau/p-Tau)CSF) was also previously described in AD patients in comparison with healthy controls41,42. Furthermore, (p-Tau/Tau)CSF has been shown to be lower in AD patients than in control patients and patients with fronto-temporal dementia43. However, no difference in (p-Tau/Tau)CSF was found between patients with mild AD and those with moderate AD41. (p-Tau/Tau)CSF was also associated with the rate of cognitive decline, showing a negative dose-dependent relation between (p-Tau/Tau)CSF and yearly MMSE score fold change during AD44. In other words, a low (p-Tau/Tau)CSF in patients with AD is associated with a faster cognitive decline than that observed in other AD patients with higher (p-Tau/Tau)CSF. This association implies that AD patients with low [Aβ1–42]CSF and elevated [Tau]CSF and [p-Tau]CSF are more likely to be in an advanced stage of the disease.

Although these results are conflicting, the CSF AD biomarker profile seems helpful in the differentiation of MCI patients from AD patients and provides information about whether the patients is in an early or late stage of the disease.

The need to find alternative body fluids for biomarker identification in AD has recently led investigators to analyze currently known CSF biomarkers for AD in plasma45–57. Studies in this area have shown conflicting results with (i) no difference between AD and control patients47,49,50, (ii) differences in plasma Aβ1–4245,58, Tau57 and p-Tau54 concentrations between AD and control patients, and (iii) differences in plasma Aβ1–4253,58, Tau, and p-Tau54 levels among patients with MCI due to AD, patients with AD, and control subjects. Other articles have reported that the plasma Aβ1–42 concentration might change during disease evolution, showing abnormally high concentrations at the preclinical stage or beginning of cognitive decline that decrease progressively during AD progression51,55. Moreover, other studies have shown different linear correlations in the context of AD (i) between imaging data of amyloid plaque deposition in the brain and CSF59 or plasma46,48 biomarker concentrations and (ii) between CSF and plasma biomarker concentrations45,47,50,57,58. The mechanisms behind brain AD biomarker clearance pathways (blood–brain, CSF–brain and blood–CSF barriers) are not yet understood, and it is not clear if those barriers are altered during the disease. Nonetheless, some articles suggest that biomarkers in plasma could mirror brain and CSF biomarker deposition and metabolism60. However, some studies did not observe any correlation between CSF and plasma biomarker concentrations56. There are a variety of possible factors that could explain the inconsistent conclusions and concentration value heterogeneity among studies. For example, technical (antibody used, time and temperature of sample conservation, hydrophobic and albumin binding properties of Aβ, low concentration in comparison with CSF, etc.) and physiological (effect of age and diet, peripheral origins, kidney and hepatic clearance, etc.) reasons51,58 may make determining plasma Aβ1–42 level alterations in the context of AD difficult. For these reasons, the clinical utility of plasmatic Aβ1–42 and Tau has not yet been demonstrated, and the need to identify other plasma AD biomarkers is crucial for AD diagnosis.

In this retrospective study, we explored [NA]plasma in patients between 58 and 79 years old consulting for memory complaints for the first time. Our study examined the relationship between [NA]plasma and concomitant diagnostic criteria such as MMSE score and CSF biomarker profile (Aβ1–42, Tau and p-Tau). Due to the deregulation of noradrenergic transmission in the brain during AD, we wanted to determine whether [NA]plasma could be correlated with clinical parameters reflecting the stage of the disease at the cognitive (MMSE score) and molecular (Aβ1–42, Tau, and p-Tau CSF biomarkers) levels.

Materials/subjects and methods

Study population

All patients presented to the Cognitive Neurology Center of Lariboisière (Paris) for their first consultation between 2009 and 2014. Patients involved in this study were between 58 and 79 years old at the time of blood sampling. MMSE score and lumbar puncture were performed the day of blood sampling or <1 month later. The MMSE is a worldwide commonly used, easy to apply and rapid screening tool lasting <10 min. The MMSE score provides supporting information for dementia diagnosis that evaluates global cognitive impairment for all causes of dementia61. Briefly, the paper-based test consists of 11 orally administered questions with verbal and written responses concerning different domains (attention, memory, orientation, language, and ability to follow verbal and written commands) with a maximum score of 30 (normal cognition) and lower scores highlighting a severe deficit62. The original article published in 1975 defined 24 as a cutoff score for normal cognition with a sensitivity and specificity of 87% and 82.6%, respectively61. In a more recent study, the mean MMSE score of the population older than 90 years without dementia was reported to be 26.6, whereas the cutoff score for normal cognition was reported to be 23.3, very similar to the cutoff score for normal cognition in the younger population (~23 or 24 points)62,63. In the context of AD, the MMSE score is used to assess disease severity and is occasionally used to estimate efficacy in clinical drug trials64. Previous studies have shown that MMSE scores decrease during AD progression at different rates depending on disease progression and patient education65. More generally, patients in the moderate to severe stages of AD have an MMSE score below 2066. Sample size was calculated based on results from previous articles highlighting a significant difference in plasma catecholamines between AD and non-AD patients. Raskind et al.23 observed a significant difference between advanced AD and control patients with a small sample size (<20 patients). Therefore, we based our calculation for sample size on the article of Umageki et al.28 that examined adrenaline levels. Considering a common standard deviation of 18.46 pg/mL, a sample size of 68 patients is necessary to show a difference of 12.69 pg/mL between the two groups with a power of 80% and an α of 5%. Seventy-one patients were included in this retrospective study: 32 AD patients (diagnoses were performed according to NIA-AA guidelines4), 22 other dementia (OD; frontotemporal dementia, vascular dementia, or dementia with Lewy bodies) patients, and 17 neurological control (NC) patients. NC patients were defined as those with memory complaints, mental depression or anxiety but for whom no dementia was diagnosed. The following cutoff values for core AD CSF biomarkers were used as supportive criteria for dementia due to AD: Aβ1–42 (<550 pg/mL), total-Tau (>400 pg/mL), and p-Tau (>50 pg/mL). Demographic information, MMSE scores, presence of the APOE ε4 allele, CSF biomarkers (Aβ1–42 protein, total Tau, and p-Tau protein) and concomitant medications of the studied cohort are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and physiologic data of studied cohort.

| NC | OD | AD | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 17 | 22 | 32 | – | |

| Sex | % of female patients | 52.9 | 36.4 | 56.3 | 0.3360 |

| Age | Age mean (SD) in year | 67 (6.671) | 67.27 (5.650) | 70.69 (6.703) | 0.0746 |

| MMSE | MMSE score median (IQR) | 28 (27–29) | 21 (16.25–23.25) | 23 (20–25) | <0.0001 |

| APOE4a | % of patients carrying APOE ε4 allele | 15.4 | 36.8 | 70.0 | 0.0021 |

| CSF Aβ1–42 concentrationb | CSF Aβ concentration mean (SD) | 795.4 (155,8) | 793.1 (294.5) | 419.2 (162.2) | <0.0001 |

| CSF Tau concentrationb | CSF Tau concentration median (IQR) | 172 (139–239.5) | 245 (190–299) | 581.5 (388.8–766.8) | <0.0001 |

| CSF p-Tau concentrationb | CSF p-Tau concentration median (IQR) | 34.50 (19.50–44.75) | 44 (34–59.50) | 88.5 (69.45–113.50) | <0.0001 |

| Plasma NA concentration | Plasma NA concentration median (IQR) | 2564 (1614–3131) | 2108 (1540–2561) | 2194 (1846–3534) | 0.3873 |

| % of patients with co-medication | Anti-Alzheimer or anti-Parkinsonian/dopaminergic agents | 5.9 | 22.7 | 18.8 | 0.3536 |

| Antidepressants | 23.5 | 27.3 | 21.9 | 0.9000 | |

| Benzodiazepines (anxiolytics/hypnotics) and Neuroleptics | 5.9 | 18.2 | 9.4 | 0.4361 | |

| Lipid-lowering agents, oral antidiabetics | 35.3 | 40.9 | 28.1 | 0.6143 | |

| Anti-hypertensive agents | 52.9 | 31.8 | 31.3 | 0.2770 | |

| Veinotonics / vasodilatators | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | – | |

| Others (Vitamines, anti-asthmatics, non steroidal anti-inflammatory agents) | 23.5 | 18.2 | 12.5 | 0.6069 | |

aFive NC, three OD, and two AD patients did not undergo APOE genotyping.

bThree NC, one OD, and two AD patients did not undergo lumbar puncture.

Plasma NA quantification

Patients fasted overnight (for ~12 h) before blood collection and were in the decubitus position during sampling. Plasma samples were purified and analyzed with a reagent kit for HPLC analysis of catecholamines in plasma (Chromsystems, order #5000) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, blood samples were stabilized with glutathione, and plasma was isolated less than 1 h after blood sampling by centrifugation. Plasma samples were stored at −80 °C. After thawing, 1 mL of plasma was used to extract catecholamines for dosage by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrochemical detection. Experimenters did not know the corresponding group of the sample during dosage.

CSF biomarker quantification

Lumbar punctures were performed on fasting patients, typically between 9 and 12 a.m. CSF samples were centrifuged at 1 g for 10 min at 4 °C within 4 h of collection, aliquoted in 0.5-mL polypropylene tubes and stored at –80 °C for further analysis. CSF levels of Aβ1–42, total Tau, and p-Tau were measured using the commercially available sandwich ELISA INNOTEST®, according to the manufacturer’s procedures (Fujirebio Europe NV, formerly Innogenetics NV).

Statistical analysis

Depending on the normality of the data (D’Agostino-Pearson normality test), the results are presented as the mean with standard deviation (SD) (standard error of mean in figures) or median with interquartile range (IQR: 25–75th percentiles) (95% confidence interval in figures). For normally distributed data, we performed Student’s t test (or Student’s t test with Welch’s correction if the F-test showed significantly different variances between groups) or one-way ANOVA. For non-normally distributed samples, we performed a Mann–Whitney test or Kruskal–Wallis test. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare frequencies. Linear correlation coefficients were calculated using Pearson’s correlation test or Spearman’s correlation test for normally or not normally distributed data, respectively. To compare distributions of data, we performed the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. We performed Rosner’s Extreme Studentized Deviate test (using log-normal distribution for plasma and CSF biomolecules) for multiple outliers (two-sided test) with a p value of 0.01, and we found no outliers for MMSE score, [NA]plasma, [Aβ1–42]CSF, [Tau]CSF, or [p-Tau]CSF. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 software. Statistical significance was set at p value < 0.05.

Results

Characterization of the study cohort

The studied groups did not significantly differ by sex ratio, age, or concomitant treatments (Table 1). As expected, they differed by MMSE score and by APOE ε4 carrier status (Table 1). Clinical diagnosis of AD made by the neurologist was based on age, MMSE score, and CSF biomarkers, according to NIA-AA guidelines4. AD patients had significantly lower Aβ1–42, higher p-Tau, and higher total-Tau CSF concentrations than OD and NC patients (Table 1).

Correlation between plasma NA concentration and cognitive MMSE score in AD patients

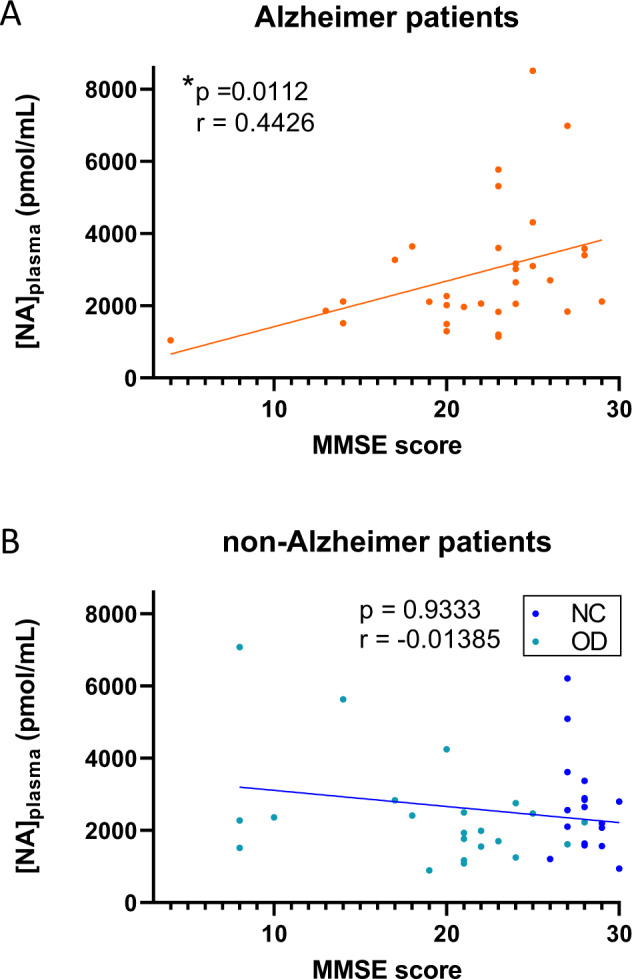

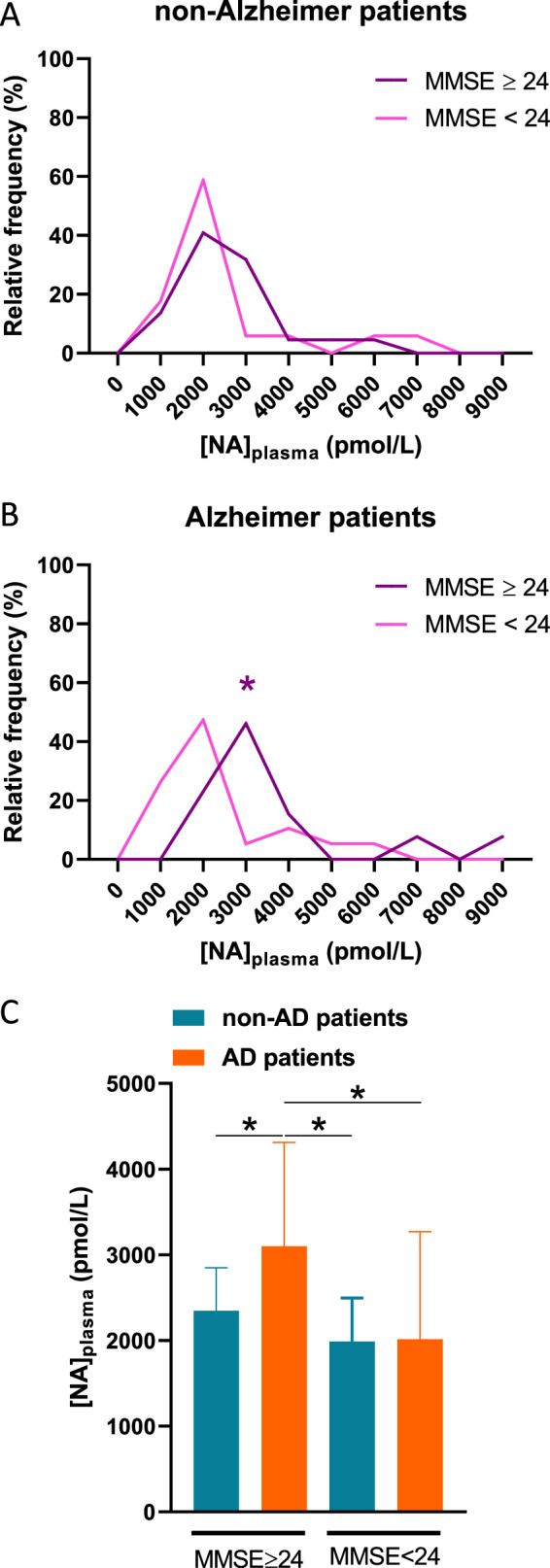

As previously described in a specific cortical brain region21, we observed a significant linear correlation between [NA]plasma at the peripheral level and MMSE score in AD patients (Spearman’s correlation, r = 0.4426 (95% CI: 0.1004–0.6912); p value = 0.0112; equation: Y = 126.3*X + 158) (Fig. 1a). However, this correlation was not observed in non-AD patients (Spearman’s correlation, r = −0.01385 (95% CI: −0.3365 to 0.3117); p value=0.9333; equation: Y = −44.63*X + 3556) (Fig. 1b). These results suggest a possible link between [NA]plasma and cognitive decline in AD patients. Nonetheless, we observed no difference in [NA]plasma among the AD, OD and NC patients (Table 1). We discriminated patients with an MMSE score above (≥) and below (<) 24, which correspond to the cutoff score for normal cognition in the literature67. In non-AD patients, we observed no difference in the distribution of [NA]plasma between patients with an MMSE score above and those with a score below 24 (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, p value = 0.7459) (Fig. 2a). On the other hand, we found a significant difference between the distribution of [NA]plasma in AD patients with an MMSE score above and those with a score below 24 (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, p value = 0.0260) (Fig. 2b). Moreover, we observed that the median [NA]plasma of AD patients with an MMSE score above 24 was significantly higher than the median [NA]plasma of non-AD patients with a similar MMSE score (≥24) (Mann–Whitney test, p value = 0.0287) and lower (<24) MMSE score (Mann–Whitney test, p value = 0.0136) and than the median [NA]plasma of other AD patients (Mann–Whitney test, p value = 0.0177). We observed no difference between the median [NA]plasma of AD patients with an MMSE score below 24 and that of non-AD patients with similar (Mann–Whitney test, p value = 0.8757) or higher (Mann–Whitney test, p value = 0.3851) MMSE scores (Fig. 2c). Taken together, these results support the idea that there is a subpopulation of AD patients with an MMSE score above 24 and a higher median {NA]plasma than other patient groups, implying that a mild cognitive decline in AD depicted by MMSE score is associated with an elevated [NA]plasma.

Fig. 1. MMSE score correlates with [NA]plasma in AD patients.

Linear regression between [NA]plasma and MMSE score of AD (a) and non-AD (b) patients. * indicates p value < 0.05.

Fig. 2. Existence of subpopulations of AD patients described by MMSE score and [NA]plasma.

a Relative frequency distribution of [NA]plasma in non-AD patients with MMSE score above and below 24. b Relative frequency distribution of [NA]plasma in AD patients with MMSE score above and below 24. c [NA]plasma median of NC, OD, and AD patients with MMSE score above and below 24. * indicates p value < 0.05.

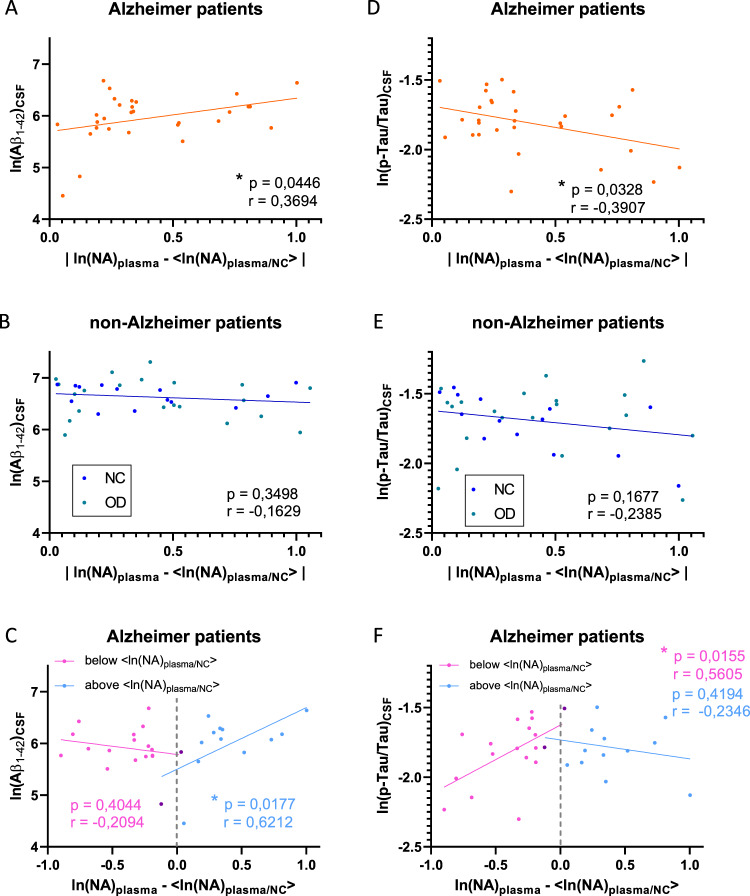

NA plasma level in AD is associated with MMSE score and CSF biomarker profile

To determine whether [NA]plasma reflects early disease evolution, we examined whether there was a correlation between the distance from the NC patient median [NA]plasma and the CSF biomarker profile. Because of the non-normal distribution of [NA]plasma data, we decided to use logarithmic data as previously described68 (in the following text, all statistical tests for CSF biomarkers were performed on logarithmic data). This distance was defined as the absolute value of ln(NA)plasma—<ln(NA)plasma/N>, with <ln(NA)plasma/N> the median value of logarithmic [NA]plasma from NC patients (<ln(NA)plasma/NC ≥ 7.849). We found a significant positive linear correlation between this absolute distance and [Aβ1–42]CSF in AD patients (Pearson’s correlation, r = 0.3694 (95% CI 0.01047 to 0.6439); p value = 0.0446; equation: Y = 0.6449*X + 5.695) (Fig. 3a), but this correlation was not observed in non-AD patients (Pearson’s correlation, r = −0.1629 (95% CI −0.4706 to 0.1801); p value = 0.3498; equation: Y = −0.1662*X + 6.697) (Fig. 3b). Looking at the relative distance of ln[NA]plasma from <ln(NA)plasma/NC > (negative or positive when respectively lower or higher than the NC patients median), we observed a negative correlation that does not reach significance for negative distance (Pearson’s correlation, r = −0.2094 (95% CI −0.6160 to 0.2854); p value = 0.4044; equation: Y = −0.3175*X + 5.786) and a significant positive correlation for positive distance (Pearson’s correlation, r = 0.6212 (95% CI: 0.1352–0.8663); p value = 0.0177; equation: Y = 1.192*X + 5.499) (Fig. 3c). Similarly, we found a negative linear correlation between absolute distance from <ln(NA)plasma/N> and (p-Tau/Tau)CSF in AD patients (Pearson’s correlation, r = −0.3907 (95% CI: −0.6583 to −0.03541); p value = 0.0328; equation: Y = −0.3079*X – 1.687) (Fig. 3d) but not in non-AD patients (Pearson’s correlation, r = −0.2385 (95% CI: −0.5296 to 0.1029); p value = 0.1677; equation: Y = −0.1737*X – 1.621) (Fig. 3e). An examination of the relative distance from <ln(NA)plasma/NC> revealed a significant positive correlation for negative distance (Pearson’s correlation, r = 0.5605 (95% CI: 0.1269–0.8143); p value = 0.0155; equation: Y = 0.4962*X – 1.625) and a negative correlation for positive distance that does not reach significance (Pearson’s correlation, r = −0.2346 (95% CI: −0.6805 to 0.3380); p value = 0.4194; equation: Y = −0.1361*X – 1.732) (Fig. 3f). Taken together, our results suggest that [NA]plasma may reflect the progression of AD, highlighting the existence of different groups of AD patients characterized by different biomarkers.

Fig. 3. Absolute [NA]plasma distance from median of NC patients correlates with [Aβ1–42]CSF and (p-Tau/Tau)CSF in AD patients.

Linear correlations between absolute distance of ln(NA)plasma from median ln(NA)plasma/NC with [Aβ1–42]CSF in AD (a) and non-AD (b) patients. c Linear correlations between negative (in pink) and positive (in blue) values of ln(NA)plasma-<ln(NA)plasma/NC>with [Aβ1–42]CSF in AD patients (points in purple were counted in both groups). Linear correlations between absolute distance of ln(NA)plasma from median ln(NA)plasma/NC with (p-Tau/Tau)CSF in AD (d) and non-AD (e) patients. f Linear correlations between negative (in pink) and positive (in blue) values of ln(NA)plasma-<ln(NA)plasma/NC>with (p-Tau/Tau)CSF in AD patients (points in purple were counted in both groups). * indicates p value < 0.05.

Discussion

There is a significant amount of literature on deregulation of cerebral, plasma, and urine NA concentrations in murine models of AD69–72 and in human AD patients21,28,29,73,74. In mouse models, NA has been implicated in the microglial phagocytosis of Aβ1–42 plaques and cognition24,75. In humans, NA levels in cortical brain regions have been correlated with dementia score20 and MMSE score21, which decreases during AD development67. This observation is consistent with our results showing a significant correlation between [NA]plasma and MMSE score in AD patients. Regarding those results, it is tempting to say that [NA]plasma could be a mirror of cerebral NA deregulation and could help in the diagnosis of AD. Previous studies have shown an increase23 or a decrease28 in [NA]plasma in AD patients in comparison with the concentration in control patients. This discordance could be explained by the existence of subpopulations of AD patients, as suggested previously23 and as identified in our analysis as patients with a high distance from the median [NA]plasma of NC patients (meaning high or low [NA]plasma).

In the present study, high [NA]plasma in AD patients was associated with higher [Aβ1–42]CSF than in other AD patients with [NA]plasma similar to NC patients. Several studies in the literature have compared [Aβ1–42]CSF between MCI stage and more or less severe AD. MCI patients have been shown to have a higher [Aβ1–42]CSF than AD patients34–37,40. There have also been conflicting results concerning CSF Tau and p-Tau concentrations, showing no difference or increased levels in late-stage AD compared with MCI34–37,40,41,76. However, the differences observed were not always significant. The absence of statistical significance could be due to several parameters that differ among the different studies, such as the precision of the chemical dosage, sample storage, age of patients, sex ratio of the cohort groups, MMSE score, or advancement of the disease, involving stages of AD more or less distant from MCI. Moreover, the temporal evolution of biomarkers and cognitive markers of AD have previously been shown to differ according to disease stage (asymptomatic, MCI and dementia stage)77. We observed a lower (p-Tau/Tau)CSF in AD patients with low [NA]plasma than in non-AD patients with [NA]plasma similar to [NA]plasma in NC patients. A low (p-Tau/Tau)CSF has also been associated with faster cognitive decline44, suggesting a possible link between this ratio and disease severity. In this way, low (p-Tau/Tau)CSF associated with low MMSE score and low [Aβ1–42]CSF is more likely to describe an advanced stage of AD pathology.

Regarding MMSE score, [Aβ1–42]CSF, and (p-Tau/Tau)CSF, it is tempting to speculate that AD patients with high or low [NA]plasma represent an early or late stage of AD, setting [NA]plasma as a potential marker of disease evolution. However, the link between the brain and [NA]plasma alterations during AD is not yet understood. We hypothesize that the [NA]plasma increase observed in AD patients could be due to (i) NA oversecretion in the CNS and disruption of the blood-brain barrier that may occur in AD78, (ii) release of cerebral NA in the blood through the CSF interface, with the potential of a linear correlation between [NA]CSF and [NA]plasma23, (iii) deregulation of NA secretion into the blood by the sympathetic system regulated by the LC26, and (iv) NA oversecretion from sympathetic noradrenergic postganglionic neurons to targeted organs and leakage or spillover into the blood79. We did not approach the concept of cognitive reserve in this article. Cognitive reserve is the phenomenon that maintains cognitive function despite advanced physiological symptoms of AD pathology in the brain80. Robertson developed the idea that LC-noradrenergic system activity may be the biological mechanism explaining the gap between cognitive function and pathophysiological observations of the disease (especially amyloid plaques)81, which has been further supported by several articles82–84. The pupillary response, a potential marker of NA-LC activity, illustrates that NA activity is enhanced by cognitively challenging stimuli. Knowing that NA seems to mediate neurocompensatory and neuroprotective effects, variables of cognitive reserve (education, enriched environment/novelty, social interactions, mental activity) may lessen AD pathology through noradrenergic pathway activation81. Thus, this pathway represents a good candidate for the missing link in the cognition-brain pathology discrepancy observed in AD. Robertson has highlighted the fact that cognitive reserve phenomena through the action of NA in AD could have a direct effect on AD symptoms (anti-inflammatory action, inhibition of amyloid aggregation, etc.) and/or a compensatory effect (increased connectivity, network reorganization). This complex question remains open and needs to be explored with further studies.

In this study, we showed for the first time that [NA]plasma was correlated with MMSE score in the context of AD. We described particular profiles of MMSE score and CSF AD biomarkers for AD patients with high and low [NA]plasma. [NA]plasma deregulation could hypothetically reflect overactivation and regression of the LC during AD. These results imply that (1) [NA]plasma could support the early diagnosis of AD, (2) [NA]plasma could help to better characterize AD patient profiles during disease evolution, and (3) the link between LC degeneration and [NA]plasma in the context of AD needs to be further investigated. Combined with the MMSE score, [NA]plasma could help the patient be referred to a specialist before the appearance of advanced AD symptoms. For example, physicians could advise patients with memory complaints, good MMSE scores and high [NA]plasma to consult a neurologist for further examinations. Thus, this process could favor fast and early diagnosis of AD, which opens new research potentials for blood biomarkers in AD.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who were involved in this retrospective study and their caregivers. We also thank Claire Paquet, MD, PhD (Memory Resources and Research Center, Cognitive Neurology Center, INSERM UMR-S 942, University Hospital of Paris Diderot Saint Louis-Lariboisière-Fernand Widal, APHP, France) for initiating and conducting this study as well as Jacques Callebert, PharmD, PhD (Department of Biochemistry, University Hospital of Paris Diderot Saint Louis-Lariboisière-Fernand Widal, APHP, France) for performing the blood sample analyses. We also thank Claire Hourrègue, MD; Julien Dumurgier, MD, PhD; Jacques Hugon, MD, PhD and Emmanuel Cognat, MD, PhD (University Hospital of Paris Diderot Saint Louis-Lariboisière-Fernand Widal, APHP, France) as well as Audrey Gabelle, MD, PhD, Jean-Pierre Garnier, PhD and Sylvain Lehmann, MD, PhD (University Hospital of Montpellier, France) for their time and support.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Patients gave their informed and written consent to have their samples stored in an officially registered and ethically approved biological collection that has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Paris University Hospitals (CEERB [Comité d’Ethique En Recherche Biomédicale], Bichat University Hospital, Paris, France).

Conflict of interest

Alzohis is a company that has activities related to the submitted work. This study and this publication were produced and written in a responsible and ethical manner.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Motta C, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation predicts cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2018;89:1237–1242. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blennow K. A review of fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: moving from CSF to blood. Neurol. Ther. 2017;6:15–24. doi: 10.1007/s40120-017-0073-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carswell CJ, et al. Clinical utility of amyloid PET imaging with (18)F-florbetapir: a retrospective study of 100 patients. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2018;89:294–299. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-316194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jack CR, et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Dement. J. Alzheimer's Assoc. 2018;14:535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paterson RW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: clinical utility of an extended panel of biomarkers in a specialist cognitive clinic. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2018;10:32. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0361-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gannon M, et al. Noradrenergic dysfunction in Alzheimera’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2015;9:220. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trillo L, et al. Ascending monoaminergic systems alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Translating basic science into clinical care. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013;37:1363–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly SC, et al. Locus coeruleus cellular and molecular pathology during the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2017;5:8. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0411-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sara SJ. The locus coeruleus and noradrenergic modulation of cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;10:211–223. doi: 10.1038/nrn2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satoh A, Iijima KM. Roles of tau pathology in the locus coeruleus (LC) in age-associated pathophysiology and Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: potential strategies to protect the LC against aging. Brain Res. 2019;1702:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grudzien A, et al. Locus coeruleus neurofibrillary degeneration in aging, mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2007;28:327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olivieri P, et al. Early alteration of the locus coeruleus in phenotypic variants of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2019;6:1345–1351. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi J, et al. Detection of changes in the locus coeruleus in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: high-resolution fast spin-echo T1-weighted imaging. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2015;15:334–340. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh A, et al. An experimental model of Braak’s pretangle proposal for the origin of Alzheimer’s disease: the role of locus coeruleus in early symptom development. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2019;11:59. doi: 10.1186/s13195-019-0511-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giorgi FS, et al. The neuroanatomy of the reticular nucleus locus coeruleus in Alzheimera’s Disease. Front. Neuroanat. 2017;11:80. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2017.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betts MJ, et al. Locus coeruleus imaging as a biomarker for noradrenergic dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain. 2019;142:2558–2571. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Theofilas P, et al. Locus coeruleus volume and cell population changes during Alzheimer’s disease progression: a stereological study in human postmortem brains with potential implication for early-stage biomarker discovery. Alzheimer's Dement. J. Alzheimer's Assoc. 2017;13:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross JA, Gliebus G, Van Bockstaele EJ. Stress induced neural reorganization: a conceptual framework linking depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;85:136–151. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross JA, McGonigle P, Van Bockstaele EJ. Locus Coeruleus, norepinephrine and Aβ peptides in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Stress. 2015;2:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adolfsson R, Gottfries C, Roos B, Winblad B. Changes in the brain catecholamines in patients with dementia of Alzheimer type. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1979;135:216–223. doi: 10.1192/bjp.135.3.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vermeiren Y, Van Dam D, Aerts T, Engelborghs S, De Deyn PP. Monoaminergic neurotransmitter alterations in postmortem brain regions of depressed and aggressive patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2014;35:2691–2700. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elrod R, et al. Effects of Alzheimer’s disease severity on cerebrospinal fluid norepinephrine concentration. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1997;154:25–30. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Halter JB, Jimerson DC. Norepinephrine and MHPG levels in CSF and plasma in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1984;41:343. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790150033006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalinin S, et al. Noradrenaline deficiency in brain increases β-amyloid plaque burden in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2007;28:1206–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordan R, Gwathmey JK, Xie L-H. Autonomic and endocrine control of cardiovascular function. World J. Cardiol. 2015;7:204–214. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i4.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szabadi E. Functional neuroanatomy of the central noradrenergic system. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxf.) 2013;27:659–693. doi: 10.1177/0269881113490326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wehrwein EA, Orer HS, Barman SM. Overview of the anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology of the autonomic nervous system. Compr. Physiol. 2016;6:1239–1278. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umegaki H, et al. Low plasma epinephrine in elderly female subjects of dementia of Alzheimer type. Brain Res. 2000;858:67–70. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umegaki H, Tamaya N, Shinkai T, Iguchi A. The metabolism of plasma glucose and catecholamines in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Gerontol. 2000;35:1373–1382. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petrie EC, Peskind ER, Dobie DJ, Veith RC, Raskind MA. Plasma catecholamine and cardiovascular responses to physostigmine in Alzheimer’s disease and aging. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26:147–164. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reisberg B, et al. Stage-specific behavioral, cognitive, and in vivo changes in community residing subjects with age-associated memory impairment and primary degenerative dementia of the Alzheimer type. Drug Dev. Res. 1988;15:101–114. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albert MS, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Dement. J. Alzheimer's Assoc. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vega JN, Newhouse PA. Mild cognitive impairment: diagnosis, longitudinal course, and emerging treatments. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16:490. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0490-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poulsen K, Bahl JM, Simonsen AH, Hasselbalch SG, Heegaard NH. Distinct transthyretin oxidation isoform profile in spinal fluid from patients with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Clin. Proteom. 2014;11:12. doi: 10.1186/1559-0275-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janelidze S, et al. CSF biomarkers of neuroinflammation and cerebrovascular dysfunction in early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2018;91:e867–e877. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hampel H, et al. Value of CSF beta-amyloid1–42 and tau as predictors of Alzheimer’s disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Mol. Psychiatry. 2004;9:705–710. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Höglund K, et al. Prediction of Alzheimer’s disease using a cerebrospinal fluid pattern of C-terminally truncated beta-amyloid peptides. Neurodegener. Dis. 2008;5:268–276. doi: 10.1159/000119457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han P, et al. A quantitative analysis of brain soluble tau and the tau secretion factor. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2017;76:44–51. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlw105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schönknecht P, Pantel J, Kaiser E, Schröder J. Total and phospho-tau (Thr 181) CSF levels in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Psychogeriatra Pol. 2004;1:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wildsmith KR, et al. Identification of longitudinally dynamic biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid by targeted proteomics. Mol. Neurodegener. 2014;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riemenschneider M, et al. Phospho-tau/total tau ratio in cerebrospinal fluid discriminates Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease from other dementias. Mol. Psychiatry. 2003;8:343–347. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corrêa JD, Starling D, Teixeira AL, Caramelli P, Silva TA. Chemokines in CSF of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69:455–459. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2011000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pijnenburg YAL, et al. CSF neurofilaments in frontotemporal dementia compared with early onset Alzheimer’s disease and controls. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2007;23:225–230. doi: 10.1159/000099473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kester MI, et al. CSF biomarkers predict rate of cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73:1353–1358. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bd8271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teunissen CE, et al. Plasma amyloid-β (Aβ42) correlates with cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2018;62:1857–1863. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakamura A, et al. High performance plasma amyloid-β biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2018;554:249–254. doi: 10.1038/nature25456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giedraitis V, et al. The normal equilibrium between CSF and plasma amyloid beta levels is disrupted in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2007;427:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park J-C, et al. Chemically treated plasma Aβ is a potential blood-based biomarker for screening cerebral amyloid deposition. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2017;9:20. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0248-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lövheim H, et al. Plasma concentrations of free amyloid β cannot predict the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Dement. J. Alzheimer's Assoc. 2017;13:778–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Figurski MJ, et al. Improved protocol for measurement of plasma β-amyloid in longitudinal evaluation of Alzheimer’s Disease neuroimaging Initiative study patients. Alzheimer's Dement. J. Alzheimer's Assoc. 2012;8:250–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poljak A, Sachdev PS. Plasma amyloid beta peptides: an Alzheimer’s conundrum or a more accessible Alzheimer’s biomarker? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2017;17:3–5. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2016.1217156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takeda S, Sato N, Rakugi H, Morishita R. Plasma β-amyloid as potential biomarker of Alzheimer disease: possibility of diagnostic tool for Alzheimer disease. Mol. Biosyst. 2010;6:1760. doi: 10.1039/c003148h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim HJ, et al. Elevation of the plasma Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio as a diagnostic marker of sporadic early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2015;48:1043–1050. doi: 10.3233/JAD-143018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang C-C, et al. Assay of plasma phosphorylated tau protein (Threonine 181) and total tau protein in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2018;61:1323–1332. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rembach A, et al. Changes in plasma amyloid beta in a longitudinal study of aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2014;10:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Le Bastard N, et al. No correlation between time-linked plasma and CSF Aβ levels. Neurochem. Int. 2009;55:820–825. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fossati S, et al. Plasma tau complements CSF tau and P-tau in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Dement. Amst. Neth. 2019;11:483–492. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Janelidze S, et al. Plasma β-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular disease. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26801. doi: 10.1038/srep26801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fagan AM, et al. Comparison of analytical platforms for cerebrospinal fluid measures of β-amyloid 1–42, total tau, and p-tau181 for identifying Alzheimer disease amyloid plaque pathology. Arch. Neurol. 2011;68:1137. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xin S-H, Tan L, Cao X, Yu J-T, Tan L. Clearance of amyloid beta and tau in Alzheimer’s Disease: from mechanisms to therapy. Neurotox. Res. 2018;34:733–748. doi: 10.1007/s12640-018-9895-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsoi KKF, Chan JYC, Hirai HW, Wong SYS, Kwok TCY. Cognitive tests to detect dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015;175:1450. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Legdeur N, et al. Cognitive functioning of individuals aged 90 years and older without dementia: a systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017;36:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jia J, et al. Efficacy and safety of Donepezil in Chinese patients with severe alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2017;56:1495–1504. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yoelin AB, Saunders NW. Score disparity between the MMSE and the SLUMS. Am. J. Alzheimer's Dis. Dementiasr. 2017;32:282–288. doi: 10.1177/1533317517705222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harrison J. Cognitive approaches to early Alzheimer’s Disease diagnosis. Med. Clin. North Am. 2013;97:425–438. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Doody RS, Massman P, Dunn JK. A method for estimating progression rates in Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2001;58:449–454. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cleophas, T. J. & Zwinderman, A. H. Logarithmic transformations, a great help to statistical analyses. In Clinical Data Analysis on a Pocket Calculator: Understanding the Scientific Methods of Statistical Reasoning and Hypothesis Testing (eds. Cleophas, T. J. & Zwinderman, A. H.) 243–247 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

- 69.Lv, C. et al. Determination of catecholamines and their metabolites in rat urine by ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry for the study of identifying potential markers for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Mass Spectrom. 50, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Francis BM, et al. Reduced tissue levels of noradrenaline are associated with behavioral phenotypes of the TgCRND8 mouse model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1934–1944. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Von Linstow CU, et al. Effect of aging and Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology on brain monoamines in mice. Neurochem. Int. 2017;108:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rorabaugh JM, et al. Chemogenetic locus coeruleus activation restores reversal learning in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2017;140:3023–3038. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu L, et al. Simultaneous determination of catecholamines and their metabolites related to Alzheimer’s disease in human urine. J. Sep. Sci. 2011;34:1198–1204. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201000799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vermeiren Y, et al. Brain serotonergic and noradrenergic deficiencies in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia compared to early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2016;53:1079–1096. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heneka MT, et al. Locus ceruleus controls Alzheimer’s disease pathology by modulating microglial functions through norepinephrine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:6058–6063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909586107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Betts MJ, et al. Locus coeruleus MRI contrast is reduced in Alzheimer’s disease dementia and correlates with CSF Aβ levels. Alzheimer's Dement. Amst. Neth. 2019;11:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bertens D, Knol DL, Scheltens P, Visser PJ. Temporal evolution of biomarkers and cognitive markers in the asymptomatic, MCI and dementia stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Dement. J. Alzheimer's Assoc. 2015;11:511–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.05.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamazaki, Y. & Kanekiyo, T. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Goldstein DS, Eisenhofer G, Kopin IJ. Sources and significance of plasma levels of catechols and their metabolites in humans. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;305:800–811. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.049270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stern Y, Barulli D. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2015–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Robertson IH. A noradrenergic theory of cognitive reserve: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2013;34:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wilson RS, et al. Neural reserve, neuronal density in the locus ceruleus, and cognitive decline. Neurology. 2013;80:1202–1208. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182897103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xu W, Yu J-T, Tan M-S, Tan L. Cognitive reserve and Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015;51:187–208. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8720-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fleck, J. I. et al. The impact of age and cognitive reserve on resting-state brain connectivity. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]