Abstract

Flexibility is intuitively valued as a means of dynamically adapting to uncertainty. Historically, it has been especially prized during times of crisis. This is clearly demonstrated today as the current Coronavirus crisis is unfolding; there are many different dimensions of flexibility, ranging from versatility, agility, and resilience, to hedging, robustness and liquidity. For convenience, we fuse these terms together under the conceptual umbrella of “super-flexibility”. We define super-flexibility as a dynamic capability to simultaneously withstand turbulence AND adapt to fluid reality. Our field research has focused on how companies in Silicon Valley embrace uncertainty and drive adaptation. In this paper, we draw on the experience of a manufacturing firm facing the floods that hit Thailand in October 2011. The crisis enabled us to observe a situation in which the different nuances of flexibility collectively came into play within a compressed time-frame. In this paper, we showcase the practical application of super-flexibility in a crisis. First, we describe the conceptual foundations of flexibility and its different nuances. We then examine the chronology of the crisis as events unfolded. We conclude by distilling a number of “super-flexibility” lessons for business leaders.

Keywords: Adaptation, Change leadership, Crisis management, Dynamic execution, Flexibility, VUCA world

Introduction

In today's interconnected world, digital technologies, environmental crises, geo-political dynamics, economic cycles and corporate challenges uniquely coalesce to trigger serious disruptions and hidden opportunities. Coronavirus is the latest crisis that showcases how inter-connected our world has become. Business leaders have to "manage in the moment," improvise quickly and deviate from plans. If the old game was about planning for, and predicting, the future, the new game is about surfing a fluid business landscape. Navigating uncertainty is the new leadership challenge.

The imperative, we argue, is to become super-flexible: how to adapt, re-invent and evolve; while maintaining consistency with core principles, staying the course and providing anchors of stability. As McKinsey (1932) pointed out several decades ago, “the unsoundness of the policies of many firms is due to their inflexibility.” As new crises unfold and the pace of transformation accelerates, leading super-flexibly is analogous to braving extreme sports like white-water rafting and kite surfing; velocity and direction morph quickly as winds and currents shift. The imperative is to seize the moment and strive for successful outcomes.

Research Foundations

While many studies focus on defining flexibility, how to operationalize the concept still remains elusive. One explanation is that flexibility is polymorphous. Context-specific actions that provide flexibility in one situation may not work in another setting. In addition, there is confusion when trying to disentangle the different nuances of flexibility.

Citation analysis reveals interest in flexibility spikes during crises and periods of technological disruption, when there is an urgent need for innovative, adaptive solutions. For example, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, economists Hart (1937) and Stigler (1939) viewed flexibility as a means of coping with demand fluctuations and changing expectations. Later research examined various corporate responses to the 1973 Oil Crisis (Ansoff 1975; Eppink 1978; Grewal and Tansuhaj 2001). Klein and Meckling (1958) studied flexibility in designing weapon systems during the Cold War. This line of thinking was later applied to complex engineering projects (Olsson and Magnussen 2007; Brady et al., 2012).

Environmental degradation stimulated the development of “resilience” as a means of regenerating damaged ecosystems (Holling 1974; Hahn and Nykvist 2017). In software development, the 2001 “agile” movement arose when innovations generated by “open-source” software disrupted traditional approaches (Highsmith 2001). A recent citation review also highlighted a substantial increase in the number of research papers on flexibility after the 2008 Financial Crisis (Coombe 2012). Today, the unprecedented emergence of the coronavirus crisis has presented us with another global challenge, demanding a fast and super-flexible response.

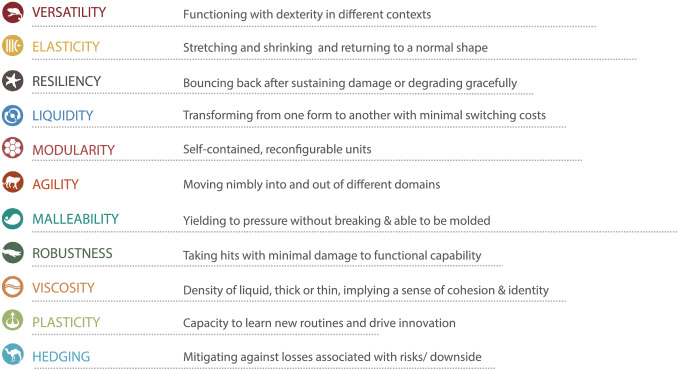

Examining the literature, there are several terms used interchangeably with flexibility, creating both precision and ambiguity. This is why we grouped together the different dimensions of flexibility, under the umbrella term “super-flexibility”. They include agility, elasticity, hedging, liquidity, malleability, modularity, versatility, plasticity, resilience, robustness, and viscosity (Sushil 2005, 2017; Bahrami and Evans 2010; Shukla et al. 2019). Table 1 defines several concepts related to flexibility.

Table 1.

Flexibility: definitions of related concepts

As we examine these concepts, their different nuances also emerge. For example, having the liquidity to exploit an opportunity in the moment is different from robustness, which refers to the capacity to withstand turbulence and to deflect threats. Resilience refers to the ability to rebound from setbacks, while agility is about acceleration and movement. Reliance on hedging mechanisms such as insurance, buffers or slack, to protect against potentially damaging situations, is different from versatility, the ability to switch gears, wear different hats and be competent in several domains. To avoid getting bogged down in these semantic differences, we integrated these senses, under one conceptual rubric: “super-flexibility”.

In this paper, we showcase the practical application of several super-flexibility concepts in a crisis situation and distill practical lessons for business leaders.

The Chronology of a Crisis: A Case Vignette

Over the past few decades, several electronics companies have set up manufacturing operations in Thailand due to the country’s competitive costs, proficient labor force, and logistical convenience (Robinson 2011). These businesses took a large hit when catastrophic flooding—the worst to hit the country in 50 years—damaged key supply-link chains in October 2011.

Fabrinet, a manufacturing company with two facilities in Thailand, produces components for optical communications systems, industrial lasers, and sensors. Its business model is to provide low volume, high mix production capability for complex advanced optical components, using customers’ own equipment, in a dedicated part of its factory. At the time of the floods, Fabrinet had just reported revenues of $744 million and operating income of $64 million for the fiscal year ended June 24, 2011. The company was in the midst of its best financial quarter ever.

In the following section, we describe how Fabrinet’s leadership team dealt with the devastating impact of the floods that destroyed one of its manufacturing plants and almost flooded its second facility. Just how Fabrinet came back from the brink without losing any customers, with minimum disruption to shipments, and maintained its share price, showcases the practical application of several flexibility concepts.

Tom Mitchell founded Fabrinet in 2000. He was one of the four co-founders of Seagate Technology, an innovative disk drive manufacturer in Silicon Valley. Mitchell served as Seagate’s President and COO from 1983 to 1991. While at Seagate, Mitchell—a former U.S. Marine officer who had a tour of duty in Vietnam during the 1960s—earned a reputation for producing disk drives at a much lower cost. In addition to relying on a high-volume strategy to achieve economies of scale, Mitchell also relocated the company’s manufacturing operations to Asia. At the end of 1982, Seagate began to assemble disk drives in Singapore (Bahrami and Evans 1985; Jauch and Townsend 1989). Within 2 years, Seagate transferred almost all of its manufacturing to Singapore, added a second manufacturing site in Thailand, and reduced its California staff by half (Gebhardt 1999). Using this strategy, Seagate increased its market share and maintained its dominant position, reaching $1 billion in revenue by 1987.

Following later stints as the COO at Conner Peripherals (later acquired by Seagate), Mitchell founded JTS Corporation during the 1990s. The company ran out of cash and went out of business, a hard lesson never forgotten. Mitchell then decided to found Fabrinet in 2000. His vision was to be a high-quality manufacturing partner and service provider for OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers), with a focus on low volume, high mix, complex optical component (Maleval 2010). He founded Fabrinet with $1 million of his own capital, and later received a $19 million investment from Hambretcht & Quist Asia. Fabrinet took over Seagate’s Chokchai manufacturing site in Thailand, and Seagate became one of Fabrinet’s first customers.

Fabrinet pioneered the concept of “factory within a factory”. Customers provide the equipment needed to build their components and sub-systems. Fabrinet provides the facilities, labor, logistics, advanced manufacturing discipline and supply chain expertise. Each customer has its own dedicated team. Over the next 10 years, Fabrinet expanded its Asia-based manufacturing hubs, with two factories, Pinehurst and Chokchai, in Thailand, and another in China.

Fabrinet was on its way to setting another record year for the 2011–2012 fiscal year. Having gone “public” by undertaking its IPO in June 2010, its cash balance was $127 million. This reserve would prove auspicious when disaster hit.

Early October 2011: Going to ‘Alert Level’ Status

After weeks of constant rainfall during Summer 2011 and news reports of flooding in the northern area of Thailand, Fabrinet’s management team decided to take steps to monitor potential flooding at its two Bangkok-based manufacturing campuses, Chokchoi and Pinehurst, located about seven miles apart. This was necessary as the excess flood waters continued to flow south from Thailand’s northern region, finding their way to the Gulf of Thailand. In September 2011, the leadership team decided to add 18 inches of height to Chokchai’s outer barrier wall as a precautionary measure. On October 6, with news of increased flooding in the Auyutthaya Province, close to Fabrinet’s two campuses, the company was placed on Alert Status. They started to hold daily meetings of the “Emergency Preparedness/Disaster Recovery” (EP/DRT) team, led by its President and Chief Operating Officer, Dr. Harpal Gill. The team was responsible for putting together flood contingency plans at both campuses.

Under the direction of the EP/DRT, the company quickly moved to fortify both campuses, and continued to monitor news of flooding in the north. On Saturday, October 8—just 2 days after going into “Alert Status”—sandbags were positioned at both campuses, pumps and backup power systems were added, and retaining walls were tested. In addition, Fabrinet issued a statement to customers explaining the situation and its actions. The EP/DRT also created a fishbone diagram (see Fig. 1) to better anticipate contingency plans. Fortunately, they had the cash reserves to purchase sandbags, shrink wrap supplies and boats, in anticipation of potential flooding. These pre-emptive moves allowed Fabrinet to remain agile in a rapidly evolving situation.

Fig. 1.

Fabrinet’s fish bone diagram

Gill also increased the frequency of the EP/DRT meetings to twice a day, and asked senior managers to stay 24/7 on each campus. The company continued to take additional precautionary steps, such as moving the IT servers to higher ground, and reinforcing the barriers at both campuses.

Though the two campuses were not yet engulfed by water, the team was hearing stories about other facilities in the local area devastated by flooding. The water levels near both campuses continued to rise. Despite conflicting media reports on the potential local damage, Mitchell and Gill decided to check the facts for themselves, and hired a helicopter to survey the area. They concluded that the local area was becoming more vulnerable, and sent 95% of employees home as a safety precaution.

By the next day, the Thai Government had announced flood alerts throughout the region, including plans to open the floodgates, allowing the water to recede. Meanwhile, water had breached the perimeter walls at the Pinehurst campus and entered the parking areas. By October 21, the water level appeared to stabilize at Pinehurst, and continued to rise outside Chokchai. At both facilities, the remaining staff shrink-wrapped and moved much of the equipment to higher floors. A number of support functions—including procurement and finance—were moved to another location (Bahrami and Evans 2014).

Believing that the Chokchai plant might be at risk, Gill decided to assess the situation for himself. He recalled:

For two days, the water just continued to rise, so one of my guys who lives near our factory, on the seventeenth floor, said. There’s water on the street—I went to the seventeenth floor…took binoculars and [from] what I saw that night, I knew we were in trouble... the canal wasn’t moving. That night when the water continued to rise…I said we should all sleep on the second floor” (Bahrami and Evans 2014).

Three hours later, Dr. Gill’s assumption proved true. He recalled:

At about eleven twenty-two, the wall broke…The water came, just like a tsunami, and within thirty seconds, there was so much water that it engulfed the entire campus.

The focus now shifted to saving the Pinehurst campus. During the following two weeks, from October 23 to November 7, Mitchell remained in continuous contact with customers, and the EP/DRT focused their efforts on recovery. By then, the entire Chokchai campus was flooded, and the facility was unusable. “I knew that we only had until November 7, to get everything running again,” recalled Gill, “otherwise we would start to lose customers”. Over those next 14 days, Gill and the team worked tirelessly to re-start operations. Mitchell continued to act as the focal point of communication with customers.

The team deployed imaginative ways to protect customers’ equipment in their allocated mini factories at the Pinehurst campus. For example, they sealed entire pieces of machinery by wrapping them in sourced car covers. When sandbags could not be filled due to lack of sand, the team drove a truck to the beach and loaded up. Expensive equipment was bubble wrapped and jacked up off the ground in case of seepage. These actions were enabled by ample cash reserves, which Mitchell kept on hand, recalling his painful experience running out of cash at JTS.

The uncertainty on the ground had to be communicated to anxious customers, who were dependent on Fabrinet for key components and sub-systems. Mitchell emphasized they would never promise anything that could not be done. This meant managing customers’ expectations on a daily basis. They made regular calls and sent daily updates. At the peak of the crisis, the team did not know whether the situation would worsen or improve. Either way, they had to prepare for different contingencies.

Customers even showed up at Pinehurst, checking on the status of their shipments. Gill redeployed the construction crew from a semi-finished building, and asked them to build walking bridges between all the campus’ buildings. Resourceful team members collected flashlights, batteries, drinking water, bandages, pontoons, and other essential items. Others were asked to find creative solutions to preserve manufactured goods.

On October 29, Gill noticed something stirring on the lake. It was near the 9th hole of the golf course close to Pinehurst. Gill noted:

at about 5 o’clock at night, the water started flowing. I looked around and said to the team, ‘Let’s go and get in the boat. Let’s see which way the water is flowing. Is it going to continue to flow or is it going to start coming up again?’ We took the boat ride and saw the water running through and I said, ‘..this may be a risk but it’s a risk we have to take. Let’s go unwrap, [the shrink wrap]’ and everyone thought I was crazy. An hour ago I was saying ‘Wrap as fast as you can,’ and then we came back and I said we were going to unwrap. Tom said ‘We have to start unwrapping,’ because if the water continued to rise, we were in trouble anyway (Bahrami and Evans 2014).

Swinging Back into Production

The team started to plan for the restoration and refurbishment of customers’ equipment by unwrapping the shrink-wrap; the goal was to kick-start production as quickly as possible and to meet the November 7th deadline.

Several team members credited advanced planning to their ability to get operations up-and-running at Pinehurst. The fishbone diagram communicated what needed to be done by the different team members. Executive offices were stripped of furniture so they could be converted into clean rooms. Unconventional measures had to be taken swiftly to bring Pinehurst back online.

Several teams were tasked with setting up 100 showers overnight by converting the spray washers located in every toilet to proper showers through quick and fast plastic plumbing, while others collected sleeping bags and pillows, set up laundry stations, and gathered other amenities including food, water and basic toiletries. Meanwhile management oversaw the construction of a wharf so that employees could return to the Pinehurst campus by boat. They also got an ambulance and a boat dedicated to emergencies. With all the basics covered, they set up a makeshift hostel at Pinehurst. Things were looking up. Operations at Pinehurst were resuming, products were being unwrapped and prepared for shipping, and customers’ confidence was being restored.

As Gill comments:

“The Thai workforce really cared about the factory and they cared about the community. So what made them come back? They were proud that they could help to contribute. I talked to a lot of people and they wanted to make sure that the factory was up and running. They were a key part of the team”.

Fabrinet’s Chief Strategy Officer commented:

Customers who were in Chokchai, had every reason to relocate. ..And yet those customers came back to us and that speaks volumes about the service mentality that Tom has built into the DNA of the company. I joined the company in January (2012) that is two months after the flood, you would never know that it happened.

Super-Flexibility in Action

How can we be super-flexible in a crisis situation? What can we learn from Fabrinet’s experience of a crisis? Which “super-flexible” initiatives can we learn from? Actions taken by Fabrinet’s leaders illustrate super-flexibility in practice.

They were robust by thinking ahead and delegating authority within a clear framework.

They hedged their bets by anticipating different scenarios and making contingency plans.

They were versatile, used creative strategies and monitored impending danger, using the evidence of their own eyes.

They were agile in communicating with customers and making quick decisions as the crisis unfolded.

They showcased resilience and bounced back by re-starting operations two weeks after the floods.

They leveraged their “liquid” assets and cash reserves to ensure they had the relevant supplies to minimize damage and re-start operations.

In a nutshell, the Fabrinet case illustrates how several flexibility concepts can be simultaneously leveraged to address a risky and fluid situation.

Robustness: Delegating Authority Within a Clear Framework

Robustness is about a clear purpose and core values that guide behavior and action. Fabrinet’s leadership team set a guiding framework within which others were empowered to operate. Guiding principles minimize the need for micro-management, facilitate delegation, and enable front-liners to make decisions and take the initiative.

The cultural framework that Mitchell had established, ahead of time, enabled Gill and the team to move swiftly and take decisive action. Putting people above profits, prioritizing delegated teamwork, and emphasizing constant communication, provided stable and consistent guidelines for executing a broad range of responses: securing supplies, building a dam, moving equipment, and setting up temporary housing. The team’s collective actions, based on a clear foundation, enabled their adaptive responses in a fast-moving situation.

Clear guiding principles gave the team specific boundaries within which to operate, without having to seek permission every step of the way. The key objectives were (1) not to endanger the lives of any Fabrinet employees, (2) jump-start operations as quickly as possible, and (3) keep customers and maintain production volume. Several other manufacturers took longer to recover, partly because front-line teams had to get permission from headquarters before taking any action.

Hedging: Anticipating Possible Scenarios and Mapping Key Priorities

Hedging involves mitigating risks by anticipating different scenarios and developing contingency plans. There is no time to think in a crisis: the focus must be on action. Hedging enables key players to think through possibilities and to develop back-up plans before they are needed.

The fishbone diagram (see Fig. 1) used by Gill and the EP/DRT was a critical tool in keeping the team on the same page and mapping out possible flood scenarios. It described key priorities, and clarified roles and accountabilities of different team members. Critical actions included securing customized bubble wrap to protect customers’ equipment, creating a satellite office for the procurement and finance teams, moving the customer data base to the higher floors, and setting up temporary housing for employees. Team members could take decisive action without having to resort to intricate coordination.

Versatility: Sensing First-Hand Information and Switching Gears

Versatility involves functioning effectively in different environments, and the ability to switch gears and wear different hats. Sensing early warning signals is a crucial step in switching gears. In a crisis situation, when there is a lot of noise and conflicting messages, seeking first-hand information, free of filtering or distortion, is critical for making optimal decisions.

As an engineer, Gill had a knack for assessing situations first hand. Unfiltered sensing was critical in two instances. The first occurred when Mitchell and Gill took a helicopter ride on Wednesday, October 19, assessing the situation in the immediate area. They concluded that the situation was worse than predicted by the authorities. With a focus on protecting employees’ lives, the Chokchai plant was closed that same evening. The second instance occurred on the evening of Saturday, October 22, when Gill went to a colleague’s 17th floor apartment to assess flooding around Chokchai. Predicting immediate danger to the facility, he asked the team to move quickly to the second floor, just before flood waters burst open the walls at 11:22 p.m. that same night.

Agility: Frequent Communication and Decisive Action

Agility has become a buzzword in business settings. It came into prominence with the 2001 “Agile Manifesto,” intended to speed up the development of software projects. It has since been promoted as a key success factor in driving digital transformation. We define agility as the ability to move quickly in order to seize opportunities or side-step threats.

In a crisis, leaders have to make quick decisions and minimize response times. The best illustration in the Fabrinet case is the one-hour time difference between when Gill gave instructions to shrink-wrap, and then switched gears and asked the team to unwrap, when he saw the flood waters moving. The decision to set up temporary housing at Pinehurst, so employees could return to work, is another example. They set up washing machines, meals, transportation, and sleeping quarters, in a couple of days.

Frequent communication is vital in a crisis. Even if there is not much substantive information, it is important to set clear expectations regularly as reality morphs and unfolds. Mitchell and Gill were in constant phone and e-mail communication with customers. Mitchell called key customers on a daily basis, while Gill sent daily e-mails. These increased to two daily updates at the height of the crisis. “Business usually shrinks after an event like this,” a key customer said. But “Fabrinet actually got more business from us after the floods”.

Resilience: Role-Modeling a Positive Mindset and a Can-Do Attitude

Resilience, or the capacity to bounce back, is partly about the mindset and behavioral role modeling of senior leaders. Do they focus on constructive solutions within their control, or do they panic and become victims, blaming external factors for the crisis? Gill was highly visible before, during and after the floods. As the head of the EP/DRT, he stayed on campus overnight with other Fabrinet managers throughout the crisis. He had to remain calm, reminding himself that employees would either feed off his positive energy, or flounder off perceived negativity. Once the focus shifted to restoring production, Gill patrolled the temporary housing facilities and took the 9 p.m. shift. This visibility endeared Gill to the Thai workforce: many of them returned to work to help Fabrinet kick-start manufacturing at Pinehurst by November 5.

Liquidity: Leveraging Available Cash Reserves

Liquidity is partly about having available resources that can be readily used without friction or switching costs. The concept is an essential principle of financial flexibility. The Fabrinet team was able to reboot its operations within two weeks partly because it had the cash resources to secure needed supplies including sandbags, shrink-wrap, pumps, car covers, boats, and equipment needed to set up temporary housing for employees. The company spent $97 million on flood-related expenses. It took almost 2 years for Fabrinet to get reimbursed by insurance companies for damage caused by the floods.

Concluding Lessons

What can business leaders learn about super-flexibility from Fabrinet’s experience of a crisis?

In the old world, a company was like a fixed building, needing repairs now and again, and remodeling itself to accommodate new developments. Its fundamental needs changed periodically. In today’s digital world, business entities resemble whitewater rafts, flowing through rapids without knowing what is around the corner, or how the winds or currents may shift. This is where the super-flexibility framework helps us conceptualize the realities of continuous adaptation. How can an organization stay the course and withstand turbulence through a clear sense of purpose and guiding principles that are consistent over time? (Volberda 1996) On the other hand, how should it adapt and evolve as reality morphs and unfolds?

As the Fabrinet case illustrates, super-flexibility is about leveraging different capabilities and switching gears in real time. Shifting gears is difficult due to organizational inertia; re-alignment is challenging when an enterprise is in motion. With different stakeholders and conflicting objectives, it is difficult for any firm, once it has reached a certain size, to spin on a dime. As innovation scholars have pointed out, this is why startups outperform established companies with much greater resources; alignment of goals and the ability to quickly re-deploy resources make it easier to adapt and evolve (Freeman and Engel 2007).

Becoming super-flexible requires the ability to directly sense front-line realities, coupled with decisive action, delegated authority, clear focus and team alignment. There is no magic formula or single “best” solution. Leaders need an operational palette, a dash-board, that encompasses the different senses of flexibility, from robustness, hedging and liquidity, to agility, versatility and resilience. They need a framework that enables them to select the relevant tools, depending on the context and the situation. We hope this article has given business leaders food for thought as they drive their enterprises in today’s turbulent world, where super-flexibility is an essential tool for real-time adaptation.

Key Questions.

What does flexibility mean in your context?

Which flexibility principle applies directly to your organization?

What are the barriers to flexibility?

How are the lessons of this article transferable to your organization?

Biographies

Stuart Evans

is a Distinguished Service Professor at the Integrated Innovation Institute, and Director of the Emirates-CMU i-Lab at Carnegie Mellon University (Silicon Valley Campus). His research focuses on how enterprises adapt to disruptive technologies. His professional career spans research (SRI International, Stanford Graduate School of Business,), teaching (The Judge Business School, Cambridge University), consulting (Bain and Company, Menlo Park, California) and executive management (Shugart Corporation, Sunnyvale, California). He serves on the Boards and Advisory Boards of several tech companies. Dr. Evans has published widely in leading academic journals. His book “Super-Flexibility for Knowledge Enterprises” (second edition) was published by Springer.

Homa Bahrami

is a Senior Lecturer and a Distinguished Teaching Fellow at the Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, and a Faculty Director at the Haas Center for Executive Education, She is the co-author of a major textbook (with Harold Leavitt, GSB Stanford University) “Managerial Psychology: Managing Behavior in Organizations", published by the University of Chicago Press, and translated into many languages. Her latest book is “Super-Flexibility for Knowledge Enterprises”, (second edition published by Springer). Homa has served on the Boards of Directors of three public technology companies and is active in executive education and executive development in the US, Europe, and Asia.

Footnotes

This article is partly based on the Berkeley-Haas Case Study “Real-Time Leadership at Fabrinet” 2014. https://cases.haas.berkeley.edu/search/articleDetail.aspx?article=5795.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ansoff, H. I. (1975). Managing strategic surprise by response to weak signals. California Management Review,18(2), 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami, H., & Evans, S. (1985). Industry Note: Disk Drives for Small & Microcomputer Systems, Case study #S-MM-6N, Stanford University, Graduate School of Business; and "Planning Manufacturing Capabilities, Case study# S-MM-8. Stanford: Stanford University Graduate School of Business. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami, H., & Evans, S. (2010). Super-flexibility for knowledge enterprises (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami, H., & Evans, S. (2011). Super-flexibility for real time adaptation: perspectives from silicon valley. California Management Review,53(3), 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami, H., & Evans, S. (2014). Real time leadership at Fabrinet (A) & (B); Berkeley Haas case series. Berkeley: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, T., Davies, A., & Nightingale, P. (2012) Dealing with Uncertainty in complex projects: Revisiting Klein and Meckling. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business5.

- Coombe, I. (2012) Marketing and flexibility: Debates past, present, and future. European Journal of Marketing46(10).

- Eppink, D.J. (1978) Managing the Unforeseen: A Study of Flexibility. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. Vrije Unviersiteit, Amsterdam.

- Freeman, J., & Engel, J. (2007). Models of Innovation: Start-Ups & Mature Corporations. California Management Review,50(1), 94–119. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt, K. (1999). Seagate technology, case study. Stanford: Graduate School of Business, Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, R., & Tansuhaj, P. (2001). Building organizational capabilities for managing economic crisis: The role of market orientation and strategic flexibility. Journal of Marketing,65(2), 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, T., & Nykvist, B. (2017) Are adaptations self-organized, autonomous and harmonious? Assessing the social-ecological resilience literature. Ecology & Society, 22(1), 12. 10.5751/ES-09026-220112. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, A. G. (1937). Failure and fulfillment of expectations in business fluctuations. Review of Economic Statistics,19(2), 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Highsmith, J. (2001). Agile software development: The business of innovation. IEEE Computer, 34(9), 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C. S. (1974). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecological Systems, 4, 301–321. [Google Scholar]

- Jauch, L. R., & Townsend, J. (1989). Cases in strategic management. New York: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, B.H., & Meckling, W. (1958) Application of O.R. to development decisions. Operations Research: 352–363.

- Maleval, J-J (2010) Do you remember controversial Tom Mitchell? Storage Newsletter.com. Accessed 21 June 2010.

- McKinsey, J. O. (1932). Adjusting policies to meet changing conditions. American Management Association.

- Olsson, N., & Magnussen, O. M. (2007). Flexibility at different stages in the life cycle of a project: An empirical illustration of the freedom to maneuver. Project Management Journal,38(4), 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Palanisamy, R., & Sushil. (2003/4). Measurement and enablement of information systems for organizational flexibility: An empirical study. Journal of Services Research, 3(2), 81–103.

- Robinson, G. (2011). Global supply chain awaits impact of Thai floods. FT.com. Accessed 27 Dec 2011.

- Shukla, S. K., Sushil, & Sharma, M. K. (2019). Managerial paradox toward flexibility: Emergent views using thematic analysis of literature. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 20(4), 349–370. [Google Scholar]

- Stigler, G. (1939). Production and distribution in the short run. Journal of Political Economy, 47(3), 305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Sushil. (2005). A flexible strategy framework for managing continuity and change. International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness1(1), 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sushil. (2017). Small steps for a giant leap: Flexible organization. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 18(4), 273–274. [Google Scholar]

- Volberda, H. W. (1996). Toward the flexible form: How to remain vital in hyper-competitive environments. Organization Science,7(4), 359–374. [Google Scholar]