Abstract

Soil organisms, including earthworms, are a key component of terrestrial ecosystems. However, little is known about their diversity, their distribution, and the threats affecting them. We compiled a global dataset of sampled earthworm communities from 6928 sites in 57 countries as a basis for predicting patterns in earthworm diversity, abundance, and biomass. We found that local species richness and abundance typically peaked at higher latitudes, displaying patterns opposite to those observed in aboveground organisms. However, high species dissimilarity across tropical locations may cause diversity across the entirety of the tropics to be higher than elsewhere. Climate variables were found to be more important in shaping earthworm communities than soil properties or habitat cover. These findings suggest that climate change may have serious implications for earthworm communities and for the functions they provide.

Soils harbor high biodiversity and are responsible for a wide range of ecosystem functions and services upon which terrestrial life depends (1). Despite calls for large-scale biogeographic studies of soil organisms (2), global biodiversity patterns remain relatively unknown, with most efforts focused on soil microbes (3–5). Consequently, the drivers of soil biodiversity, particularly soil fauna, remain unknown at the global scale.

Furthermore, our ecological understanding of global biodiversity patterns [e.g., latitudinal diversity gradients (6)] is largely based on the distribution of aboveground taxa. Yet many soil organisms have shown global diversity patterns that differ from above-ground organisms (3, 7–9), although the patterns often depend on the size of the soil organism (10).

Here, we analyzed global patterns in earthworm diversity, total abundance, and total biomass (hereafter “community metrics”). Earthworms are considered ecosystem engineers (11) in many habitats and also provide a variety of vital ecosystem functions and services (12). The provisioning of ecosystem functions by earthworms likely depends on the abundance, biomass, and ecological group of the earthworm species (13, 14). Consequently, understanding global patterns in community metrics for earthworms is critical for predicting how changes in their communities may alter ecosystem functioning.

Small-scale field studies have shown that soil properties such as pH and soil carbon influence earthworm diversity (11, 15, 16). For example, lower pH values constrain the diversity of earthworms by reducing calcium availability (17), and soil carbon provides resources that sustain earthworm diversity and population sizes (11). Alongside many interacting soil properties (15), a variety of other drivers can shape earthworm diversity, such as climate and habitat cover (11, 18, 19). However, to date, no framework has integrated a comprehensive set of environmental drivers of earthworm communities to identify the most important ones at a global scale.

Previous reviews suggested that earthworms may have high diversity across the tropics as a result of high endemism (10). However, this high regional diversity may not be captured by local-scale metrics. Alternatively, in the temperate region, local diversity may be higher (20) but may include fewer endemic species (10). We anticipate that earthworm community metrics (particularly diversity) will not follow global patterns seen aboveground, and instead, as seen across Europe (15), will increase with latitude. This finding would be consistent with previous studies at regional scales, which showed that the species richness of earthworms increases with latitude (19). Because of the relationship among earthworm communities, habitat cover, and soil properties on local scales, we expect soil properties (e.g., pH and soil organic carbon) to be key environmental drivers of earthworm communities.

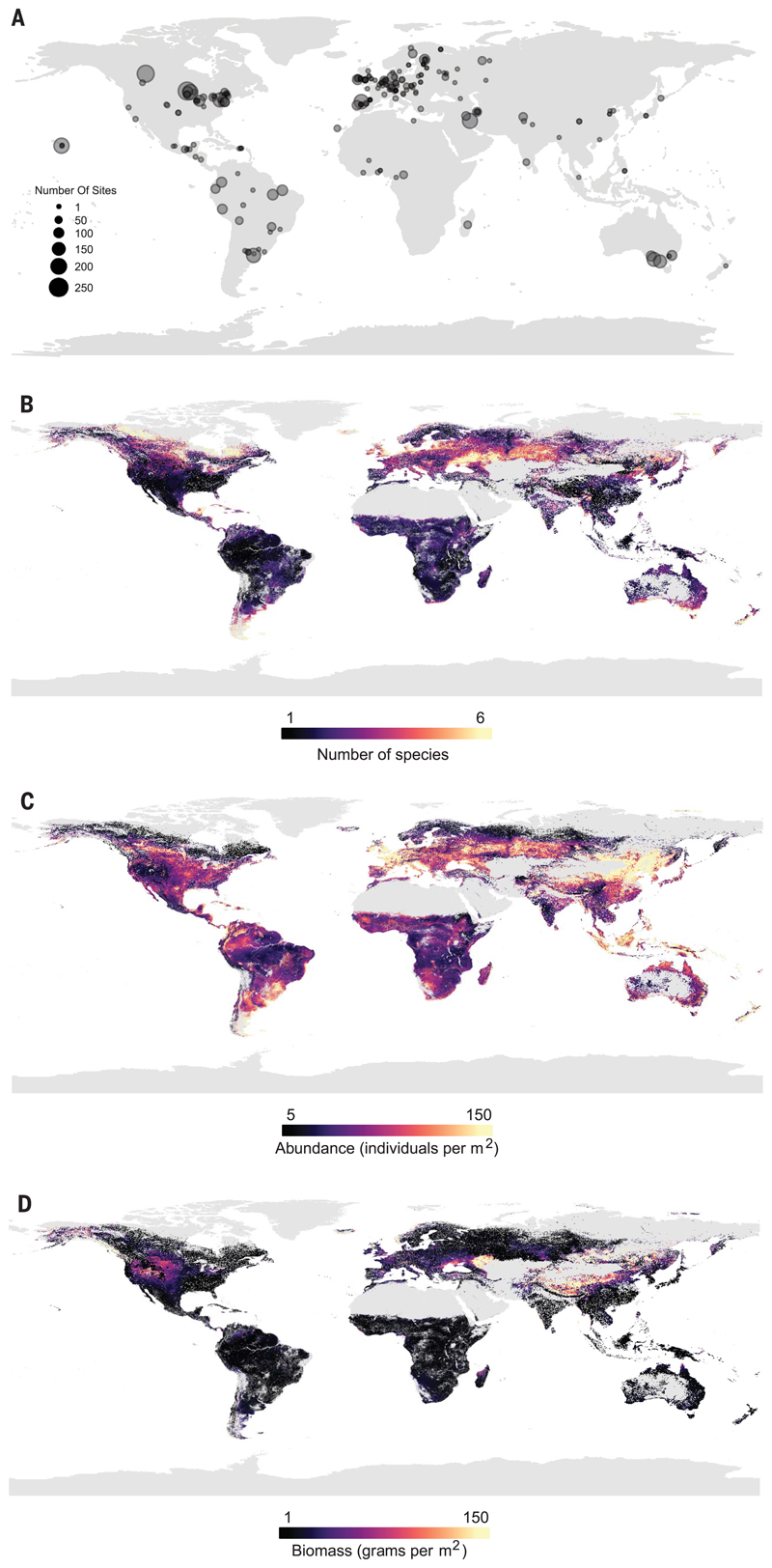

Here, we present global maps predicting local diversity (number of species), abundance, and biomass. (We use “local” in the sense of site-level: a location of one or more samples that adequately captured the earthworm community.) We collated 180 datasets from the literature and unpublished field studies (164 and 16, respectively) to create a dataset spanning 57 countries (all continents except Antarctica) and 6928 sites (Fig. 1A). We explored spatial patterns of earthworm communities and determined the environmental drivers that shape earthworm biodiversity. We then used the relationships between earthworm community metrics and environmental drivers (table S1) to predict local earthworm communities across the globe.

Fig. 1. Global distribution of earthworm diversity.

(A) Black dots represent the center of a “study” used in at least one of the three models (species richness, total abundance, and total biomass). The size of the dot corresponds to the number of sites within the study. Opaqueness is for visualization purposes only. (B to D) The globally predicted values of (B) species richness (within site), (C) total abundance, and (D) total biomass. Yellow indicates high diversity; dark purple, low diversity. Gray areas are habitat cover categories that lacked samples.

Three generalized linear mixed-effects models were constructed, one for each of the three community metrics: species richness (calculated within a site), abundance per m2, and biomass per m2. Each model contained 12 environmental variables as main effects (table S2), which were grouped into six themes; “soil,” “precipitation,” “temperature,” “water retention,” “habitat cover,” and “elevation” [habitat cover and some soil variables were measured in the field; the remaining variables were extracted from global data layers based on the geographic coordinates of the sites (14)]. Within each theme, each model contained interactions between the variables. After model simplification, all models retained most of the original variables, but some interactions were removed (table S3).

Consistent with previous results (20), local earthworm diversity predictions based on global environmental data layers resulted in estimates of one to four species per site across most of the terrestrial surface (Fig. 1B) (mean, 2.42 species; SD, 2.19). Most of the boreal and subarctic regions were predicted to have low values of species richness, which is in line with aboveground biodiversity patterns (21, 22). However, low local diversity also occurred in subtropical and tropical areas, such as Brazil, India, and Indonesia, in contrast to commonly observed aboveground patterns, such as the latitudinal gradient in plant diversity (22). This pattern could be due to different relationships with climate variables. For example, although plant diversity increases with potential evapotranspiration (PET) (22), earthworm diversity tended to decrease with increasing PET (table S3). In addition, soil properties, which are typically not included in models of above-ground diversity, can play a role in determining earthworm communities (11, 15, 23). For instance, litter availability and soil nutrient content are important regulators of earthworm diversity, with oligotrophic forest soils having more epigeic species and eutrophic soils more endogeics (23). Furthermore, tropical regions with higher decomposition rates have fewer soil organic resources and lower local earthworm diversity (Fig. 1B and table S3), dominated by endogeic species, which have specific digestion systems that allow them to feed on low-quality soil organic matter (11, 14, 20).

High local species richness was found at mid-latitudes, such as the southern tip of South America, the southern regions of Australia and New Zealand, Europe (particularly north of the Black Sea), and the northeastern United States. Although this pattern contrasts with latitudinal diversity patterns found in many aboveground organisms (6, 24), it is consistent with patterns found in some belowground organisms [ectomycorrhizal fungi (3), bacteria (5)], but not all [arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (25), oribatid mites (26)]. Such mismatches between above- and belowground biodiversity have been predicted (1, 7) but not shown across the globe for soil fauna at the local scale.

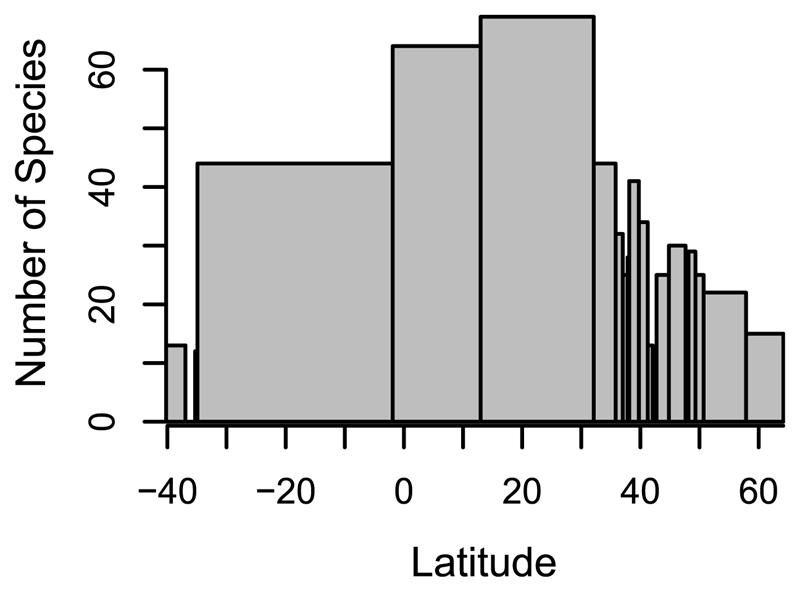

The patterns seen here could in part be a result of glaciation in the last ice age, as well as human activities. Temperate regions (mid- to high latitudes) that were previously glaciated were likely recolonized by earthworm species with high dispersal capabilities and large geographic ranges (19) and through human-mediated dispersal [“anthropochorous” earthworms (16)]. Thus, temperate communities could have high local diversity, as seen here, but those species would be widely distributed, resulting in lower regional diversity relative to local diversity. In the tropics, which did not experience glaciation, the opposite may be true. Specific locations may have individual species that are highly endemic, but these species are not widely distributed (table S4). This high local endemism would result in low local diversity (as found here) and high regional diversity [as suggested by (10)] relative to that low local diversity. When the numbers of unique species within latitudinal zones that had equal numbers of sites were calculated (i.e., a regional richness that accounted for sampling effort), there appeared to be a regional latitudinal diversity gradient (Fig. 2). Even with a sampling bias (table S4), regional richness in the tropics was greater than in the temperate regions, despite low local diversity. These results should be interpreted with caution, given the latitude span of the tropical zones. However, the underlying data suggest that endemism of earthworms and β-diversity within the tropics (27) may be considerably higher than within the well-sampled temperate region (table S4). Therefore, it is likely that the tropics harbor more species overall.

Fig. 2. The number of unique species within each latitudinal zone, when the number of sites within each zone is comparable.

The width of the bar shows the latitude range of the sites/zones.

The predicted total abundance of the local community of earthworms typically ranged between 5 and 150 individuals per m2 across the globe, in line with other estimates (28) (Fig. 1C; mean, 77.89 individuals per m2; SD, 98.94). There was a slight tendency for areas of higher total abundance to be in temperate areas, such as Europe (particularly the UK, France, and Italy), New Zealand, and part of the Pampas and surrounding region (South America), rather than the tropics. Lower total abundance occurred in many of the tropical and subtropical regions, such as Brazil, central Africa, and parts of India. Given the positive relationship between total abundance and ecosystem function (29), in regions with lower earthworm abundance, such functions may be reduced or carried out by other soil taxa (1).

The predicted total biomass of the local earthworm community (adults and juveniles) across the globe showed extreme values (>2 kg) in 0.3% of pixels, but biomass typically ranged (97% of pixels) between 1 g and 150 g per m2 [Fig. 1D; median, 6.69; mean, 2772.8; SD, 1,312,782; see (14) for additional discussion of extreme values]. The areas of high total biomass were concentrated in the Eurasian Steppe and some regions of North America. The majority of the globe showed low total biomass. In northern North America, where there are no native earthworms (13), high density and, in some regions, higher biomass of earthworms likely reflect the earthworm invasion of these regions. The small invasive European earthworm species encounter an enormous unused resource pool, which leads to high population sizes (30). On the basis of previous suggestions (28), we expected that earthworms would decrease in body size toward the poles, showing low biomass relative to the total abundance in temperate or boreal regions. In contrast, in tropical regions (e.g., Brazil and Indonesia) that are dominated by giant earthworms that normally occur at low densities and low species richness (31), we expected high biomass but low abundance. However, these patterns were not found. This could be due to the relatively small number of sample points for the biomass model (n = 3296) compared to the diversity (n = 5416) and total abundance models (n = 6358), reducing the predictive ability of the model (fig. S1C), most notably in large regions of Asia and in areas of Africa, particularly the boundaries of the Sahara Desert and the southern regions (which coincides with sites where samples are lacking). Additionally, the difficulty in consistently capturing such large earthworms in every sample may increase data variability, reducing the ability of the model to predict.

Overall, the three community metric models performed well in cross-validation (figs. S3 and S4) with relatively high R2 values [Table 1; see (14) for further details and caveats]. But given the nature of such analyses, models and maps should only be used to explore broad patterns in earthworm communities and not at the fine scale, especially in relation to conservation practices (32).

Table 1. Model validation results.

Cells in boldface show the “best” value when comparing between the main models (a mixture of sampled soil properties and SoilGrids data) and models containing only SoilGrids data. Values shown are mean square error [MSE; calculated for all predicted data (“Total”) and for tertiles (“Low,” “Mid,” “High”)] following 10-fold cross-validation of the main models and models containing only SoilGrids data, as well as R2 of the main models and SoilGrids-only models.

| Total | Low | Mid | High | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSE: Main models | ||||

| Species richness | 1.376 | 0.917 | 0.812 | 3.561 |

| Abundance | 17977.42 | 1720.75 | 2521.25 | 48751.51 |

| Biomass | 3220.29 | 264.56 | 441.25 | 8783.77 |

| MSE: SoilGrids models | ||||

| Species richness | 1.385 | 0.887 | 0.793 | 3.716 |

| Abundance | 18775.81 | 1735.11 | 2516.13 | 51156.76 |

| Biomass | 3068.00 | 199.91 | 461.88 | 8380.81 |

| Marginal | Conditional | |||

| R2: Main models | ||||

| Species richness | 0.132 | 0.748 | ||

| Abundance | 0.176 | 0.626 | ||

| Biomass | 0.201 | 0.612 | ||

| R2: SoilGrids models | ||||

| Species richness | 0.142 | 0.745 | ||

| Abundance | 0.234 | 0.643 | ||

| Biomass | 0.242 | 0.650 | ||

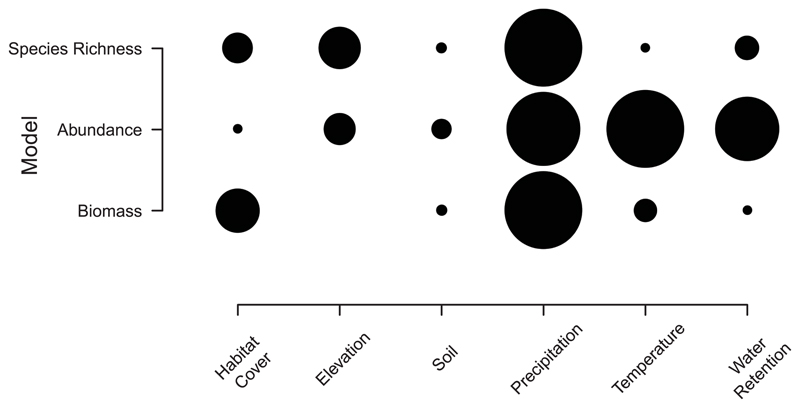

For all three community metric models, climatic variables were the most important drivers (the “precipitation” theme being the most important for both species richness and total biomass models, and “temperature” for the total abundance model; Fig. 3). The importance of climatic variables in shaping diversity and distribution patterns at large scales is consistent with many aboveground taxa [e.g., plants (22), reptiles, amphibians, and mammals (32)] and belowground taxa [bacteria and fungi (3, 5), nematodes (33)]. This suggests that climate-related methods and data, which are typically used by macro-ecologists to estimate aboveground biodiversity, may also be suitable for estimating earthworm communities. However, the strong link between climatic variables and earthworm community metrics is cause for concern, as climate will continue to change due to anthropogenic activities over the coming decades (34). Our findings further highlight that changes in temperature and precipitation are likely to influence earthworm diversity (35) and distributions (15), with implications for the functions that they provide (12). Shifts in distributions may be particularly problematic in the case of invasive earthworms, such as in areas of North America, where they can considerably change the ecosystem (13). However, a change in climate will most likely affect abundance and biomass of the earthworm communities before it affects diversity, as shifts in the latter depend on dispersal capabilities, which are relatively low in earthworms.

Fig. 3. The importance of the six variable themes from the three biodiversity models.

Rows show the results of each model (top, species richness; middle, abundance; bottom, biomass). Columns represent the variable themes that are present in the simplified biodiversity model. The most important variable group has the largest circle. Within each row, the circle size of the other variable themes is proportional to the relative change in importance. The circle size should only be compared within a row.

We expected that soil properties would be the most important driver of earthworm communities, but this was not the case (Fig. 3), likely because of the scale of the study. First, the importance of drivers could change at different spatial scales. Climate is driving patterns at global scales, but within climatic regions (or at the local scale), other variables may become more important (36). Thus, one or more soil properties may be the most important drivers of earthworm communities within each of the primary studies, rather than across them all. Second, for soil properties, the mismatch in scale between community metrics and the soil properties taken from global layers [for sites where sampled soil properties were missing (14)] potentially reduced the apparent importance of the theme. Habitat cover influenced the earthworm community (fig. S5, A and B), especially the composition of the three ecological groups (epigeics, endogeics, and anecics) (fig. S6) (14). Across larger scales, climate influences both habitat cover and soil properties, all of which affect earthworm communities. Being able to account for this indirect effect with appropriate methods and data may alter the perceived importance of soil properties and habitat cover [e.g., with pathway analysis (37) and standardized data]. However, our habitat cover variable did not directly consider local management (such as land use or intensity).

Our findings suggest that climate change might have substantial effects on earthworm communities and the functioning of ecosystems; any climate change–induced alteration in earthworm communities is likely to have cascading effects on other species in these ecosystems (13, 28). Despite earthworm communities being controlled by environmental drivers similar to those that affect above-ground communities (22, 37), these relationships result in different patterns of diversity. We highlight the need to integrate below-ground organisms into biodiversity research, despite differences in the scale of sampling, if we are to fully understand large-scale patterns of biodiversity and their underlying drivers (7, 8, 38), especially if processes underlying macroecological patterns differ between above-ground and belowground diversity (38). The inclusion of soil taxa may alter the distribution of biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities. For example, protected areas (7) may not be protecting earthworms (7), despite their importance as ecosystem function providers (12) and soil ecosystem engineers for other organisms (11). By modeling both realms, aboveground/belowground comparisons are possible, potentially allowing a clearer view of the biodiversity distribution of whole ecosystems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the reviewers who provided thoughtful and constructive feedback on this manuscript. We thank M. Winter and the sDiv team for their help in organizing the sWorm workshops, and the Biodiversity Informatics Unit (BDU) at iDiv for their assistance in making the data open access. In addition, the data providers thank all supervisors, students, collaborators, technicians, data analysts, land owners/managers, and anyone else involved with the collection, processing, and/or publication of the primary datasets.

Funding

This work was developed during and following two sWorm workshops. H.R.P.P. and the sWorm workshops were supported by the sDiv [Synthesis Centre of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig (DFG FZT 118)]. H.R.P.P., O.F., and N.E. acknowledge funding by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 677232 to N.E.). K.S.R. and W.H.v.d.P. were supported by ERC-ADV grant 323020 to W.H.v.d.P. Also supported by iDiv (DFG FZT118) Flexpool proposal 34600850 (C.A.G. and N.E.); the Academy of Finland (285882) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (postdoctoral fellowship and RGPIN-2019-05758) (E.K.C.); DOB Ecology (T.W.C., J.v.d.H., and D.R.); ERC-AdG 694368 (M.R.); and the TULIP Laboratory of Excellence (ANR-10-LABX-41) (M.L.). In addition, data collection was funded by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (12-04-01538-a, 12-04-01734-a, 14-44-03666-r_center_a, 15-29-02724-ofi_m, 16-04-01878-a 19-05-00245); Tarbiat Modares University; Aurora Organic Dairy; UGC(NERO) (F. 1-6/Acctt./NERO/2007-08/1485); Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (RGPIN-2017-05391); Slovak Research and Development Agency (APVV-0098-12); Science for Global Development through Wageningen University; Norman Borlaug LEAP Programme and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA); São Paulo Research Foundation - FAPESP (12/22510-8); Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station; INIA - Spanish Agency (SUM 2006-00012-00-0); Royal Canadian Geographical Society; Environmental Protection Agency (Ireland) (2005-S-LS-8); University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (HAW01127H; HAW01123M); European Union FP7 (FunDivEurope, 265171); U.S. Department of the Navy, Commander Pacific Fleet (W9126G-13-2-0047); Science and Engineering Research Board (SB/SO/AS-030/2013) Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi, India; Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP) of the U.S. Department of Defense (RC-1542); Maranhão State Research Foundation (FAPEMA); Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES); Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (LTT17033); Colorado Wheat Research Foundation; Zone Atelier Alpes, French National Research Agency (ANR-11-BSV7-020-01, ANR-09-STRA-02-01, ANR 06 BIODIV 009-01); Austrian Science Fund (P16027, T441); Landwirtschaftliche Rentenbank Frankfurt am Main; Welsh Government and the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (Project Ref. A AAB 62 03 qA731606); SÉPAQ; Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Finland; Science Foundation Ireland (EEB0061); University of Toronto (Faculty of Forestry); National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada; Haliburton Forest and Wildlife Reserve; NKU College of Arts and Sciences Grant; Österreichische Forschungsförderungsgesellschaft (837393 and 837426); Mountain Agriculture Research Unit of the University of Innsbruck; Higher Education Commission of Pakistan; Kerala Forest Research Institute, Peechi, Kerala; UNEP/GEF/TSBF-CIAT Project on Conservation and Sustainable Management of Belowground Biodiversity; Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Finland; Complutense University of Madrid/European Union FP7 project BioBio (FPU UCM 613520); GRDC; AWI; LWRRDC; DRDC; CONICET (National Scientific and Technical Research Council) and FONCyT (National Agency of Scientific and Technological Promotion) (PICT, PAE, PIP), Universidad Nacional de Luján y FONCyT [PICT 2293 (2006)], Fonds de recherche sur la nature et les technologies du Québec (131894), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [SCHR1000/3-1, SCHR1000/6-1, 6-2 (FOR 1598), WO 670/7-1, WO 670/7-2, and SCHA 1719/1-2], CONACYT (FONDOS MIXTOS TABASCO/PROYECTO11316); NSF (DGE-0549245, DGE-0549245, DEB-BE-0909452, NSF1241932); Institute for Environmental Science and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago; Dean’s Scholar Program at UIC; Garden Club of America Zone VI Fellowship in Urban Forestry from the Casey Tree Endowment Fund; J. E. Weaver Competitive Grant from the Nebraska Chapter of The Nature Conservancy; the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at DePaul University; Elmore Hadley Award for Research in Ecology and Evolution from the UIC Dept. of Biological Sciences; Spanish CICYT (AMB96-1161; REN2000-0783/GLO; REN2003-05553/GLO; REN2003-03989/GLO; CGL2007-60661/BOS); Yokohama National University; MEXT KAKENHI (25220104); Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (25281053, 17KT0074, 25252026); ADEME (0775C0035); Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain (CGL2017-86926-P); Syngenta Philippines; UPSTREAM; LTSER (Val Mazia/Matschertal); Marie Sklodowska Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship (747607); National Science and Technology Base Resource Survey Project of China (2018FY100306); McKnight Foundation (14-168); Program of Fundamental Researches of Presidium of Russian Academy of Sciences (AAAA-A18-118021490070-5); Brazilian National Council of Research CNPq; and French Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs.

Footnotes

Author contributions: H.R.P.P. led the analysis, data curation, and writing of the original manuscript draft. C.A.G. assisted in analyses and writing of the original manuscript draft. E.K.C. and N.E. revised subsequent manuscript drafts. J.v.d.H., D.R., and T.W.C. provided additional analyses. E.K.C., N.E., and M.P.T. acquired funding for the project. J.K., K.B.G., B.S., M.L.C.B., M.J.I.B., and G.B. contributed to data curation. H.R.P.P., C.A.G., M.L.C.B., M.J.I.B., G.B., O.F., A.O., E.M.B., J.B., U.B., T.D., F.T.d.V., B.K.-R., M.L., J.M., C.M., W.H.v.d.P., K.S.R., M.C.R., D.R., M.R., M.P.T., D.H.W., D.A.W., E.K.C., and N.E. contributed to the project conceptualization. All authors reviewed and edited the final draft manuscript. The majority of the authors provided data for the analyses.

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: Data and analysis code are available on the iDiv Data repository (DOI: 10.25829/idiv.1804-5-2593) and GitHub (https://github.com/helenphillips/GlobalEWDiversity; DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3386456).

Earthworm distribution in global soils

Earthworms are key components of soil ecological communities, performing vital functions in decomposition and nutrient cycling through ecosystems. Using data from more than 7000 sites, Phillips et al. developed global maps of the distribution of earthworm diversity, abundance, and biomass (see the Perspective by Fierer). The patterns differ from those typically found in aboveground taxa; there are peaks of diversity and abundance in the mid-latitude regions and peaks of biomass in the tropics. Climate variables strongly influence these patterns, and changes are likely to have cascading effects on other soil organisms and wider ecosystem functions.

Science, this issue p. 480; see also p. 425

References

- 1.Bardgett RD, van der Putten WH. Nature. 2014;515:505–511. doi: 10.1038/nature13855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenhauer N, et al. Pedobiologia. 2017;63:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pedobi.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tedersoo L, et al. Science. 2014;346 1256688. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delgado-Baquerizo M, et al. Science. 2018;359:320–325. doi: 10.1126/science.aap9516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahram M, et al. Nature. 2018;560:233–237. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0386-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillebrand H. Am Nat. 2004;163:192–211. doi: 10.1086/381004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron EK, et al. Conserv Biol. 2019;33:1187–1192. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fierer N, Strickland MS, Liptzin D, Bradford MA, Cleveland CC. Ecol Lett. 2009;12:1238–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van den Hoogen J, et al. Nature. 2019;572:194–198. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1418-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decaëns T. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2010;19:287–302. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards CA, editor. Earthworm Ecology. ed. 2. CRC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blouin M, et al. Eur J Soil Sci. 2013;64:161–182. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craven D, et al. Glob Change Biol. 2017;23:1065–1074. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.See supplementary materials

- 15.Rutgers M, et al. Appl Soil Ecol. 2016;97:98–111. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendrix PF, Bohlen PJ. Bioscience. 2002;52:801–811. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piearce TG. J Anim Ecol. 1972;41:167. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spurgeon DJ, Keith AM, Schmidt O, Lammertsma DR, Faber JH. BMC Ecol. 2013;13:46. doi: 10.1186/1472-6785-13-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathieu J, Davies TJ. J Biogeogr. 2014;41:1204–1214. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lavelle P, Lattaud C, Trigo D, Barois I. Plant Soil. 1995;170:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunn RR, et al. Ecol Lett. 2009;12:324–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreft H, Jetz W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608361104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fragoso C, Lavelle P. Soil Biol Biochem. 1992;24:1397–1408. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaston KJ, Blackburn TM. Pattern and Process in Macroecology. Blackwell; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davison J, et al. Science. 2015;349:970–973. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maraun M, Schatz H, Scheu S. Ecography. 2007;30:209–216. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Decaëns T, et al. Soil Biol Biochem. 2016;92:171–183. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coleman DC, Crossley DA, Hendrix PF. Fundamentals of Soil Ecology. ed. 2. Elsevier; 2004. pp. 271–298. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spaak JW, et al. Ecol Lett. 2017;20:1315–1324. doi: 10.1111/ele.12828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisenhauer N, Schlaghamerský J, Reich PB, Frelich LE. Biol Invasions. 2011;13:2191–2196. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drumond MA, et al. Braz J Biol. 2013;73:699–708. doi: 10.1590/s1519-69842013000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santini L, et al. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2018;27:968–979. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song D, et al. Appl Soil Ecol. 2017;114:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report Summary for Policymakers. 2014 www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/AR5_SYR_FINAL_SPM.pdf.

- 35.Hackenberger DK, Hackenberger BK. Eur J Soil Biol. 2014;61:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradford MA, et al. Nat Ecol Evol. 2017;1:1836–1845. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rice A, et al. Nat Ecol Evol. 2019;3:265–273. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0787-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shade A, et al. Trends Ecol Evol. 2018;33:731–744. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.