Abstract

Our previous study revealed that expression of G protein-coupled receptor 68 (GPR68) was upregulated in MDSL cells, a cell line representing Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS), in response to lenalidomide (LEN), and mediated a calcium/calpain proapoptotic pathway. Isx, a GPR68 agonist, enhanced the sensitivity to LEN in MDSL cells. The fact that Isx is not an FDA-approved drug prompts us to look for alternative candidates that could enhance the sensitivity of LEN in MDS as well as other hematologic malignancies, such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML). In the present study, we showed that regulator of calcineurin 1 (RCAN1), an endogenous inhibitor of calcineurin (CaN), was upregulated in MDSL cells in response to LEN, possibly through degradation of IKZF1. Consistently, cyclosporin (Cys), a pharmacological inhibitor of CaN, inhibited the activity of CaN and induced apoptosis in MDSL cells, indicating that CaN provided a prosurvival signal in MDSL cells. In addition, Cys enhanced the cytotoxic effect of LEN in MDS/AML cell lines as well as primary bone marrow cells from MDS patients and AML patient-derived xenograft models. Intriguingly, pretreatment with LEN reversed the suppressive effect of Cys on T cell activation. Our study suggests a novel mechanism of action of LEN in mediating cytotoxicity in MDS/AML via upregulating RCAN1 thus inhibiting the CaN prosurvival pathway. Our study also suggests that Cys enhances the sensitivity to LEN in MDS/AML cells without compromising T cell activation.

Introduction

Lenalidomide (LEN) is used for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM) and lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) that harbor deletion of chromosome 5q (del(5q))[1]. Clinical trials reveal poor response to LEN in patients with higher-risk MDS or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with or without del(5q)[2, 3]. Understanding the molecular mechanism of the action of LEN will provide novel insights into its therapeutic implications in hematologic malignancies. Recent studies demonstrated that LEN directly binds cereblon (CRBN), a component of the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, resulting in ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of Ikaros (IKZF1) and Aiolos (IKZF3), two zinc finger transcription factors, in MM cells[4, 5].

We recently found that LEN induced degradation of IKZF1 in MDS cells as well[6]. With an RNA interference screen, we identified that depletion of G protein-coupled receptor 68 (GPR68) reversed the cytotoxic effects of LEN in a cell line derived from a patient with low-risk del(5q) MDS, the MDSL cells[6]. IKZF1 acted as a transcription repressor, inhibiting the expression of GPR68 in MDSL cells[6]. Degradation of IKZF1 in response to LEN derepressed GPR68 expression, leading to activation of a calcium/calpain proapoptotic pathway in MDSL cells[6]. Of note, the GPR68 agonist, 3,5-disubstituted isoxazoles (Isx), significantly enhanced the sensitivity of MDSL cells to LEN[6], indicating a therapeutic potential of manipulating the GPR68 pathway in improving the clinical efficacy of LEN. However, Isx is not an FDA-approved drug, limiting its therapeutic application in combination with LEN. We therefore decided to identify alternative pathways with therapeutic potential in combination with LEN in MDS/AML.

In addition to GPR68, we found that depletion of interferon regulatory factor 9 (IRF9), ribosomal RNA processing 1B (RRP1B) or regulator of calcineurin 1 (RCAN1) also reversed the cytotoxic effects of LEN in MDSL cells[6]. RCAN1 is a well-known endogenous inhibitor of calcineurin (CaN)[7]. CaN, also known as protein phosphatase 3 (PPP3), is a serine/threonine phosphatase. During T cell activation, CaN is activated in response to antigen/MHC complex, contributing to proliferation, survival, cytokine production and cytotoxicity of T cells[8, 9]. The pharmacological inhibitor of CaN, cyclosporine (Cys), is used in the clinic to prevent immune rejection from organ transplantation[10]. These data prompted us to investigate whether the RCAN1-CaN signaling complex might be a potential alternative therapeutic pathway in combination with LEN for the treatment of MDS as well as other hematologic malignancies.

In the present study, we examined the combined effect of LEN and Cys in MDS / AML cells and T cells. Our results suggest that Cys enhances the sensitivity to LEN in MDS/AML cells without compromising T cell activation.

Methods

Mice

C57Bl6 (The Jackson Laboratory, 000664) and NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (The Jackson Laboratory, 005557) mice were housed and handled in the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited animal facility of University of South Carolina. Splenocytes were harvested for T cell activation assay. Pre-established and deidentified AML patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models were described previously[11].

Cell culture

Primary MDS samples were obtained from Yale University patients with written informed consent, and according to a protocol approved by the University Investigation Committee. To determine the effect of LEN on RCAN1 expression, MDSL cells were treated with DMSO or 10μM LEN for 4 days (Sigma, CDS022536). To examine the cytotoxic effect of LEN and Cys (Sigma, 30024) on MDS/AML cells, cells were treated with DMSO or 10μM LEN for 2 days, followed by concurrent treatment with control or Cys at the indicated concentrations for additional 2~4 days. To analyze CaN activity, MDSL cells were treated with 10μM Cys for 2 days.

Lentiviral transduction

The lentiviral expression vector targeting RCAN1 or IKZF1 was kindly provided by Dr. Starczynowski[6]. Lentiviruses were packaged with 293-FT cells.

Flow cytometry

MDS/AML cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC antibody and 7AAD (eBioscience, 88-8005-74) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Analysis was performed with NovoCyte Flow Cytometer with NovoExpress Software.

Colony forming cell assay

2 × 103 MDSL cells were plated in methylcellulose (StemCell Technology, 4434) in the presence of DMSO or 10μM LEN, or 10μM LEN plus 10μM Cys. For THP-1 cells, 10μM LEN plus 5μM were used for the combination group. Colonies were quantified after 7 days.

RT-qPCR

cDNA was used for qPCR with probes for GADPH (Applied Biosystems, 4331182, Assay ID Hs02758991_g1) and RCAN1 (Applied Biosystems, 4448892, Assay ID Hs01120954_m1).

Immunoblotting

Cell lysates were used for immunoblotting with RCAN1 antibody (Sigma, 087M4886V) and β-actin antibody (Cell Signaling, 3700).

Calcineurin activity

Cells were washed with Tris buffered saline and protein levels were quantified with a BCA assay. Calcineurin activity was measured with the Calcineurin cellular activity assay kit (Enzo, BML-AK816–0001).

T cell activation

Splenocytes were harvested from the C57Bl6 mice for T cell activation assay according to the manufacturer’s instruction (eBioscience, T cell activation bioassays-Bestprotocols).

Statistical analysis

Results are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. Student’s t-test was used for all the results with GraphPad Prism (v7, GraphPad).

Results and Discussion

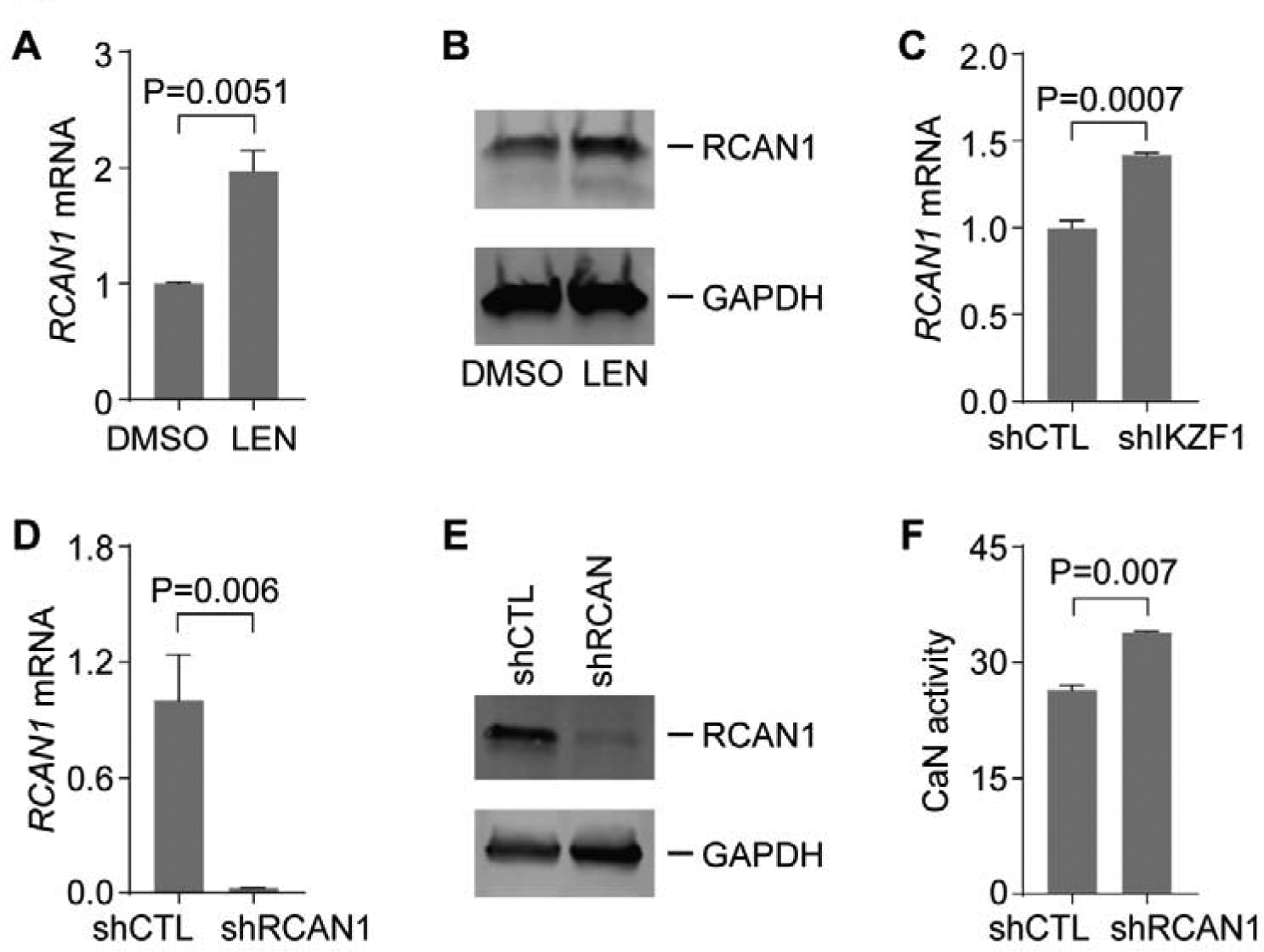

We first examined whether LEN modulated expression of RCAN1 in MDSL cells. Expression of RCAN1 at both transcript and protein levels was increased in MDSL cells after treatment with LEN at 10μM for 4 days compared to control group (Figure 1A,B). Intriguingly, depletion of IKZF1 in MDSL cells with shRNA increased RCAN1 mRNA compared to those expressing a control shRNA (shCTL, Figure 1C), indicating that IKZF1 inhibited the expression of RCAN1. To determine whether RCAN1 regulated the activity of CaN in MDSL cells, we depleted RCAN1 with shRNA (i.e. shRCAN1). Successful knockdown of RCAN1 was confirmed at transcript and protein levels (Figure 1D,E). CaN activity was increased in MDSL cells expressing shRCAN1 compared to those expressing shCTL (Figure 1F), indicating that RCAN1 also inhibited CaN activity in MDSL cells.

Figure 1. Depression of RCAN1 in MDSL cells in response to LEN.

(A-B) Expression of RCAN1 mRNA (A) and protein (B) in MDSL cells after treated with DMSO or 10μM LEN for 4 days (n=3). (C) Expression of RCAN1 mRNA in MDSL cells expressing shCTL or shIKZF1 (n=3). (D-E) Expression of RCAN1 mRNA (D) and protein (E) in MDSL cells expressing shCTL or shRCAN1 (n=4). (F) CaN activity in lysates of MDSL cells expressing shCTL or shRCAN1 (n=2).

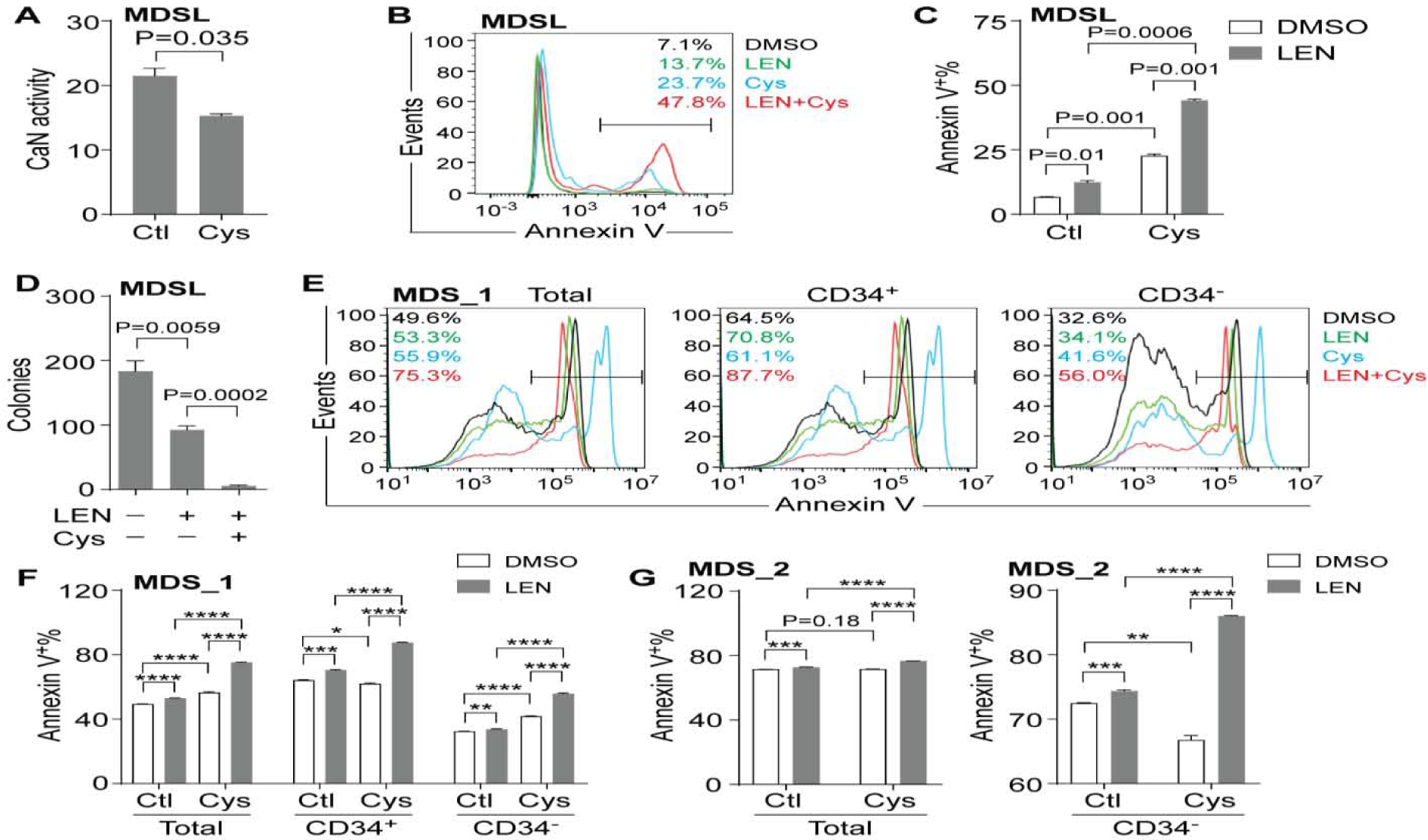

Despite the severe immunosuppressive effects mediated by high-dose of Cys, low-dose of Cys is used in pleiotropic diseased conditions[12–14]. We next examined the effects of Cys on MDSL cells. The activity of CaN was reduced in MDSL cells after treatment with 10μM Cys for 2 days compared to the control group (Figure 2A), indicating that CaN was constitutively active in MDSL cells. Given that CaN promotes survival of T cells during immune response, we examined whether CaN also regulated survival of MDSL cells by measuring Annexin V. Consistently, we observed increased Annexin V+ cells in CD34− MDSL cells after treatment with 20μM Cys for 5 days compared to the control group (Figure 2B,C), indicating that constitutively active CaN provided a prosurvival pathway in MDSL cells. We then examined the combined effect of LEN and Cys on MDSL cells. As expected, we found increased Annexin V+ cells in CD34− MDSL cells after treatment with 10μM LEN for 5 days (Figure 2B,C). In addition, we pretreated MDSL cells with DMSO or 10μM LEN for 2 days, followed by cotreatment with control (Ctl) or 20μM Cys for additional 3 days. MDSL cells (the CD34− compartment) cotreated with LEN and Cys exhibited more Annexin V+ cells as compared to the single treatment groups (Figure 2B,C). We also examined progenitor cell function by plating MDSL cells in semi solid methylcellulose. Similarly, colonies were dramatically reduced in MDSL cells in the presence of both LEN and Cys as compared to single treatment with LEN (Figure 2D). In addition, we examined the combined effect of LEN and Cys on primary bone marrow (BM) cells from MDS patients. We found increased Annexin V+ cells in BM cells from patient MDS_1, who was diagnosed with del(5q) MDS RAEB II, after single treatment with 10μM LEN or 10μM Cys (Figure 2E,F and Supplemental Table 1). The cotreatment group exhibited more Annexin V+ cells compared to the single treatment groups (Figure 2E,F). This was observed when Annexin V+ cells were analyzed within total cells and within the CD34+ and CD34− compartments (Figure 2E,F). In comparison, we observed massive apoptosis in BM cells from patient MDS_2, who was diagnosed with del(5q) MDS (Figure 2G and Supplemental Table 1). Nonetheless we observed more Annexin V+ cells, especially within the CD34− compartment, in the cotreatment group compared to the single treatment groups (Figure 2G). These results indicated that Cys enhanced the cytotoxic effect of LEN in MDS cells, including both lower-risk and higher-risk MDS, via inhibiting the CaN prosurvival pathway.

Figure 2. The combined effect of LEN and Cys on MDS cells.

(A) CaN activity in lysates of MDSL cells after treated with DMSO or 10μM Cys for 4 days (n=2). (B-C) Representative flow cytometric analysis (B) and frequency (C) of Annexin V+ cells in MDSL cells after treatment with DMSO or 10μM LEN for 2 days, followed by concurrent treatment with control (Ctl) or 20μM Cys for additional 3 days (n=2). Annexin V+ cells were analyzed within CD34− cells. (D) Colonies produced by MDSL cells in methylcellulose in the presence of DMSO, 10μM LEN, or 10μM LEN plus 10μM Cys (n=3). (E-F) Representative flow cytometric analysis (E) and frequency (F) of Annexin V+ cells in BM cells from patient MDS_1 after treatment with DMSO or 10μM LEN for 2 days, followed by concurrent treatment with control (Ctl) or 10 μM Cys for additional 2 days (n=3). (G) Frequency of Annexin V+ cells in BM cells from patient MDS_2 after treatment with DMSO or 10μM LEN for 2 days, followed by concurrent treatment with control (Ctl) or 10 μM Cys for additional 2 days (n=3). * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001

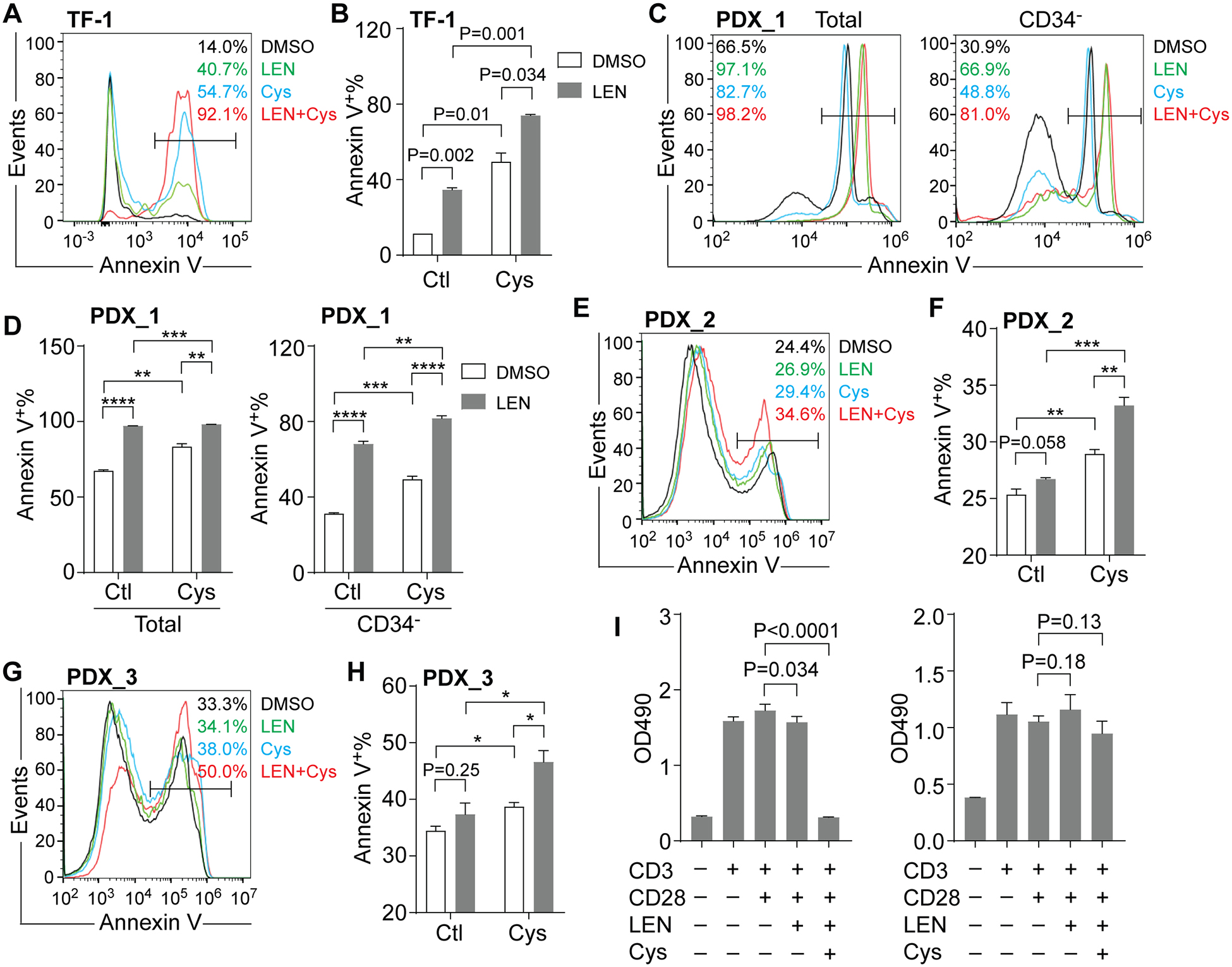

We previously found that TF-1 cells, an AML cell line with del(5q), were also sensitive to LEN[6]. Similar to MDSL cells, TF-1 cells (the CD34− compartment) exhibited more Annexin V+ cells after cotreatment with LEN and Cys compared to the single treatment groups (Figure 3A,B). However, AML cell lines THP-1 and HL60 did not exhibit more Annexin V+ cells after cotreatment with LEN and Cys compared to the single treatment groups (Supplemental Figure 1A–D). THP-1 cells formed similar number of colonies in the presence of both LEN and Cys compared to control group (Supplemental Figure 1E). In addition to AML cell lines, we also examined the combined effect of LEN and Cys on AML patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models. Increased Annexin V+ cells were observed in the PDX_1 model that harbored MLL-AF6 chromosomal translocation after treatment with 10μM LEN compared to control group, indicating that the PDX_1 model was sensitive to LEN (Figure 3C,D and Supplemental Table 1). More Annexin V+ cells were observed in the cotreatment group than the single treatment groups, especially within the CD34− compartment of the PDX_1 model (Figure 3C,D), indicating that Cys enhanced the cytotoxicity of LEN in AML cells that were sensitive to LEN. In contrast, we failed to observe increased Annexin V+ cells in the PDX_2 model that harbored complex karyotypes or the PDX_3 model that harbored del(5q) and mono 7 (Figure 3E–H and Supplemental Table 1), indicating that these two AML PDX models were resistant to LEN. Surprisingly, we observed a significant increase of Annexin V+ cells in PDX_2 and 3 models after cotreatment with LEN and Cys compared to the single treatment groups (Figure 3E–H), indicating that Cys enhanced the cytotoxicity of LEN in AML cells that were resistant to LEN. These results suggested that Cys enhanced the sensitivity to LEN in both LEN-sensitive and LEN-resistant AML cells.

Figure 3. The combined effect of LEN and Cys on AML and T cells.

(A-B) Representative flow cytometric analysis (A) and frequency (B) of Annexin V+ cells in TF-1 cells after treatment with DMSO or 10μM LEN for 2 days, followed by concurrent treatment with control (Ctl) or 20μM Cys for additional 3 days (n=2). Annexin V+ cells were gated on CD34− cells. (C-D) Representative flow cytometric analysis (C) and frequency (D) of Annexin V+ cells in PDX model (PDX_1) after treatment with DMSO or 10μM LEN for 2 days, followed by concurrent treatment with control (Ctl) or 10μM Cys for additional 3 days (n=3). (E-F) Representative flow cytometric analysis (E) and frequency (F) of Annexin V+ cells in PDX model (PDX_2) after treatment with DMSO or 10μM LEN for 2 days, followed by concurrent treatment with control (Ctl) or 10μM Cys for additional 3 days (n=3). Annexin V+ cells were gated on total cells. (G-H) Representative flow cytometric analysis (G) and frequency (H) of Annexin V+ cells in PDX model (PDX_3) after treatment with DMSO or 10μM LEN for 2 days, followed by concurrent treatment with control (Ctl) or 10μM Cys for additional 3 days (n=3). Annexin V+ cells were gated on total cells. (I) Measurement of splenocyte expansion via MTS after treatment with DMSO, 10μM LEN, or 10μM LEN plus 10μM Cys for 2 days (n=3~4, left panel). Measurement of splenocyte expansion via MTS after pretreatment with DMSO or 10μM LEN for 2 days, followed by concurrent treatment with 10μM Cys for additional 2 days (n=3~4, right panel). *, P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001

Both LEN and Cys have been shown to regulate T cell function[10, 15]. We then examined the combined effect of LEN and Cys on T cell function by measuring T cell expansion upon activation. To activate T cells, splenocytes from C57B6 mice were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. As expected, the addition of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies significantly induced T cell expansion (Figure 3 I). Single treatment with 10μM LEN did not alter T cell expansion (Figure 3I). We found a dramatic reduction of T cell expansion when cotreatment with 10μM LEN and 10μM Cys was applied for 2 days (Figure 3 I, left panel). Intriguingly, when splenocytes were pretreated with 10μM LEN for 2 days followed by cotreatment with 10μM LEN and 10μM Cys for additional 2 days, suppression of T cell expansion was reversed (Figure 3 I, right panel), indicating that sequential cotreatment of LEN and Cys did not inhibit T cell response.

In the present study, we found that the expression of RCAN1 was derepressed in MDSL cells in response to LEN. This was possibly due to degradation of IKZF1 in the presence of LEN[4, 5]. Despite the observation that knockdown of IKZF1 increased the expression of RCAN1, we failed to find any obvious IKZF1 binding peaks in the promoter region of RCAN1[6]. The mechanism of how IKZF1 regulated the expression of RCAN1 needed further study. The pharmacological inhibitor of CaN, Cys, inhibited the activity of CaN and induced apoptosis in MDSL cells, indicating that CaN was constitutively active in MDSL cells and provided a prosurvival signal. These results suggested that upregulation of RCAN1 in MDSL cells in response to LEN induced apoptosis via inhibiting the CaN prosurvival pathway. Our study suggested a novel mechanism of action of LEN in MDS cells in that LEN induced degradation of IKZF1, which led to upregulation of RCAN1 and inhibition of the CaN prosurvival pathway.

In addition, Cys also enhanced the cytotoxic effect of LEN in MDSL cells as well as primary BM cells from patients with higher-risk MDS. We observed similar cooperative cytotoxic effect of LEN and Cys in AML cell line (i.e. TF-1) as well as AML PDX models that were sensitive or resistant to LEN. In particular, certain AML PDX models contained complex cytogenetic abnormalities and genetic mutations other than a single del(5q). These results implicated a broader clinical potential of LEN for the treatment of hematologic malignancies, including higher-risk MDS and AML, in combination with Cys irrespective of del(5q). However, we failed to observe a cooperative cytotoxic effect of LEN and Cys in certain AML cell lines, such as HL-60 and THP-1 cells. This may be due to compensatory survival signals after long-term in vitro culture.

Intriguingly, pretreatment of LEN prevented the inhibitory effect of Cys on T cell activation. This was in line with the immunomodulatory effects of LEN on T cells[15]. Given that LEN did not act through mouse Crbn[16], the observation that pretreatment of LEN prevented the inhibitory effect of Cys on T cell activation implicated that LEN may act through alternative molecules. More work is needed in order to identify novel interacting molecules of LEN.

In summary, our study suggested that Cys enhanced the sensitivity to LEN in MDS/AML cells without compromising T cell activation. Future work will investigate the in vivo effect of LEN and Cys in MDS/AML.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

RCAN1, an endogenous inhibitor of calcineurin (CaN), was upregulated in an MDS cell line in response to lenalidomide (LEN).

Cyclosporine (Cys), a pharmacological inhibitor of CaN, inhibited the activity of CaN and induced apoptosis in the MDS cell line.

Cys enhanced the cytotoxic effect of LEN in MDS/AML cell lines, primary MDS patient samples and AML patient-derived xenograft models.

Pretreatment of LEN reversed the inhibitory effect of Cys on T cell activation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH (R01CA218076), St. Baldrick’s Foundation and Aplastic Anemia & MDS International Foundation, NSF (1736150). We thank the animal facility of the University of South Carolina for their help with mouse work. We thank the Yale Smilow Cancer Center Patients and Advanced Practice Providers for MDS samples. The Yale Hematology Tissue Bank is part of the Deluca Center for Innovation in Hematology Research at Yale Cancer Center.

Financial and other disclosures

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pan B and Lentzsch S, The application and biology of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) in cancer. Pharmacol Ther, 2012. 136(1): p. 56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang M, et al. , Outcome of patients with acute myeloid leukemia with monosomal karyotype who undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood, 2011. 118(6): p. 1490–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cancer, et al. , Pretreatment cytogenetics add to other prognostic factors predicting complete remission and long-term outcome in patients 60 years of age or older with acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 8461. Blood, 2006. 108(1): p. 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kronke J, et al. , Lenalidomide causes selective degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 in multiple myeloma cells. Science, 2014. 343(6168): p. 301–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu G, et al. , The myeloma drug lenalidomide promotes the cereblon-dependent destruction of Ikaros proteins. Science, 2014. 343(6168): p. 305–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang J, et al. , A calcium- and calpain-dependent pathway determines the response to lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Med, 2016. 22(7): p. 727–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arron JR, et al. , NFAT dysregulation by increased dosage of DSCR1 and DYRK1A on chromosome 21. Nature, 2006. 441(7093): p. 595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rusnak F and Mertz P, Calcineurin: form and function. Physiol Rev, 2000. 80(4): p. 1483–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayden-Martinez K, Kane LP, and Hedrick SM, Effects of a constitutively active form of calcineurin on T cell activation and thymic selection. J Immunol, 2000. 165(7): p. 3713–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamawy MM, Molecular actions of calcineurin inhibitors. Drug News Perspect, 2003. 16(5): p. 277–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wunderlich M, et al. , OKT3 prevents xenogeneic GVHD and allows reliable xenograft initiation from unfractionated human hematopoietic tissues. Blood, 2014. 123(24): p. e134–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe NJ, et al. , Long-term low-dose cyclosporine therapy for severe psoriasis: effects on renal function and structure. J Am Acad Dermatol, 1996. 35(5 Pt 1): p. 710–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isnard Bagnis C, et al. , Long-term renal effects of low-dose cyclosporine in uveitis-treated patients: follow-up study. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2002. 13(12): p. 2962–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessel A and Toubi E, Low-dose cyclosporine is a good option for severe chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2009. 123(4): p. 970; author reply 970–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotla V, et al. , Mechanism of action of lenalidomide in hematological malignancies. J Hematol Oncol, 2009. 2: p. 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kronke J, et al. , Lenalidomide induces ubiquitination and degradation of CK1alpha in del(5q) MDS. Nature, 2015. 523(7559): p. 183–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.