Abstract

In the recent years, the epidemiology of invasive fungal infections (IFIs) has changed worldwide. This is remarkably noticed with the significant increase in high-risk populations. Although surveillance of such infections is essential, data in the Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) region remain scarce. In this paper, we reviewed the existing data on the epidemiology of different IFIs in the MENA region. Epidemiological surveillance is crucial to guide optimal healthcare practices. This study can help to guide appropriate interventions and to implement antimicrobial stewardship and infection prevention and control programs in countries.

Keywords: Invasive fungal infections, Invasive candidiasis, Invasive aspergillosis, Pneumocystis pneumonia, Cryptococcal meningitis, Mucormycosis, Histoplasmosis

Introduction

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) have turned out to be a major public health concern along with the expansion of at-risk populations besides the lack of universal implementation of definitive diagnostics [1]. Numerous major risk factors for IFIs have been described including surgery, total parenteral nutrition, fungal colonization, renal replacement therapy, hemodialysis, mechanical ventilation, diabetes mellitus (DM), broad-spectrum antibiotics use, red blood cells transfusion, antifungal medication, central venous catheter, and peripheral catheter use [2]. In fact, IFIs can be divided into two categories: endemic mycoses like histoplasmosis and opportunistic mycoses like invasive candidiasis (IC), invasive aspergillosis (IA), cryptococcal meningitis (CM), Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP) [3].

In liver transplant recipients, Pneumocystis is the underlying pathogen in 7% of all pneumonia cases [4]. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) in a cohort study has indicated that fungemia ranged from 0.15% in patients with solid tumors to 1.55% in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. It occurred predominantly due to Candida spp. infections (90%), where C. albicans (46.5%), and non-albicans Candida (NAC) (53.5%) were found in patients [5]. IFIs are an important cause of morbidity and mortality among high-risk groups including solid organ transplantation (SOT) recipients and hematological malignancy patients. For instance, mortality rates were the highest for IA (67–82%) as well as cerebral forms of mucormycosis (73.5%) [6].

Even though there are limited choices of antifungals, treating patients with confirmed fungal disease with effective antifungal agents is crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality. Also, several investigations described a significant link between early reliable diagnosis and treatment of IFIs and improved outcomes of patients at risk [7]. The diagnostic includes traditional methods like culture, histopathology, and imaging expertise and newer antigen- and PCR-based diagnostic assays [8].

In this review, we focus on the epidemiology, burden and incidences of IFIs in the Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) region among high-risk groups, to support infectious disease specialists and healthcare workers in this geographic area and assist the provision of optimal care for patients susceptible to IFIs.

Epidemiology of invasive fungal infections in the MENA region

Since the increase of IFIs is strongly associated with the expanding immunosuppressed population and the increase in invasive diagnostics and treatment, an urgent need for surveillance of the changing trends in incidences is required. The knowledge of the current situation allows the assessment of the burden of such infections in the region. Thus, PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases search was done for epidemiological studies of IFIs from tertiary care hospitals published in the last decade. We used a combination of the keywords for paper retrieving including the following: “invasive fungal infections,” “invasive fungal disease,” “invasive candidiasis,” “candidaemia,” “invasive aspergillosis,” “pneumocystis pneumonia,” “mucormycosis,” “histoplasmosis,” in addition to a MENA country. Indexed original articles and case reports in English and French of any design and sampling strategy were included. Despite the globally growing importance of invasive infections, especially among the high susceptible risk groups, the epidemiological assessment of the status of IFIs is underestimated in the MENA region. Indeed, only very few reports about the estimation of IFIs were found in this region in the last decade. In the next parts of this review, we will discuss the available data concerning IC, IA, CM, Pneumocystis pneumonia, mucormycosis, and histoplasmosis in the region.

Invasive candidiasis

Candida infections accounts for approximately 70 to 90% of total IFIs [9]. Global estimates indicated that ~ 750,000 cases of IC occur annually [10]. Candidemia (Candida bloodstream infection) is the most common clinical presentation of IC and occurs mainly in hospitalized patients with an ascribable mortality of 15–35% for adults and 10–15% for neonates [11]. Only five species contribute to almost 92% of cases of candidemia: Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei. C. albicans is the most common etiological agent worldwide [11]. However, an upward trend in the incidence of NAC in IC cases was witnessed worldwide, which may be correlated with an increasing use of triazoles, mainly fluconazole [12]. Furthermore, a recent emerging multi-drug resistant Candida species, Candida auris, has been reported to cause healthcare-associated fungal infections [13]. In comparison with Candida species, several characteristics make the opportunistic C. auris unique in the field of clinical mycology such as his ability to colonize inert surfaces, capacity to cause nosocomial invasive infections, resistance to some commonly used chlorine-based disinfectants, and non-susceptibility to any or all of the systemic antifungal drugs available at this time [14, 15].

Epidemiological studies assessing the status of IC, including candidemia, are underestimated in the developing world, counting MENA countries (Table 1). Several studies have estimated the incidence rates of candidemia in MENA countries. Candidemia incidence rate was estimated to be the highest in Qatar, with an estimated rate of (15.4/100,000) [16] and the lowest in Iran (0.34/100,000) [17] (Fig. 1). IC and other IFIs were compared with reported estimations in different countries at global level (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis in the MENA region

| Country | Clinical presentation | Study period | Incidence | Age of patients | Number of isolates | Predisposing condition | Causative agent | Sample type | Diagnostic tools | Mortality rate related to IFIs | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lebanon and KSA | – | 2011–2012 | 0.39 cases/1000 discharges (Lebanon) 1.21 cases/1000 discharges (KSA) | 55.2 ± 25.1 y | 102 with IFIs |

Diabetes (41%) Coronary artery disease (24%) Leukemia (19%) Moderate to severe renal disease (16%) Congestive heart failure and chronic pulmonary disease (15%) |

C. albicans (56%) C. tropicalis (20%) C. glabrata (14%) |

– |

Culture Chest radiograph CT Galactomannan PCR |

33% | [39] |

| KSA | Candidemia (107 patients) | August 2012 and May 2016 | 26 cases per 1000 ICU admissions | 58.4 ± 18.9 y | 162 |

Diabetes (66%) (insulin treated* 29.6%) Chronic kidney disease requiring hemodialysis (34.2%) Active cancer (13.2%) Recent neutropenia (17%) Recent surgery (10.6%) Total parenteral nutrition (10.6%) Recent antibacterial therapy* (36.4%) Recent antifungal therapy* (11.9%) |

C. albicans (38.3%) C. tropicalis (16.7%) C. glabrata (16%) C. parapsilosis (13.6%) |

– | Culture | 58.6% | [49] |

| KSA | – | January 2010 and January 2015 | – | 2.4 ± 1.41 y | 129 |

ICU stay (62%) Antibiotics (65.9%) Prematurity (28.7%) Low birth weight (32.6%) Central venous catheter (45.7%) CVC (45.7%) Dialysis (8.5%) Malignancy (16.3%) Neutropenia (18.6%) Immunodeficiency (10.1%) Immunotherapy (15.5%) Previous antifungal (24.8%) Recent steroid (14.7%) Ventilator support (46.5%) |

C. albicans (45.7%) C. tropicalis (21.7%) C. parapsilosis (12.4%) C. famata (5.4%) C. lusitaniae (3.9%) Others (10.9%) |

Blood CSF Sterile body fluids (synovial fluid, peritoneal fluid, and pleural fluid) |

– |

Ventilator-related* (48.3%) ICU-related* (43.8%) |

[50] |

| KSA | Candidemia | 2002–2009 | – | ˂ 1 to ˃ 60 y | 258 |

Malignancy* Use of corticosteroids ICU admission Antibiotics and antifungals use Prior major surgery Neutropenia Diabetes mellitus Long-term dialysis* Organ transplantation |

C. albicans (34.1%) C. tropicalis (15.5%) C. parapsilosis (11.9%) C. glabrata (9.1%) C. famata (4.4%) C. krusei (4%) C. guilliermondii (2%) C. lusitaniae (0.8%) C. zeylanoides (0.4%) |

Blood |

Culture Biochemical identification |

– | [51] |

| KSA | – | January 2003 to December 2012 | 1.65 per 1000 hospital discharges per year | 52 y | 652 | – |

C. albicans (38.7%) C. tropicalis (18.9%) C. glabrata (16.3%) C. parapsilosis (12.6%) |

Blood Cerebrospinal fluid Other body fluid Tissue biopsies |

Culture Biochemical identification |

40.6% | [48] |

| Jordan | Candidemia | – | 0.48 episodes/1000 admissions | – | 158 |

Central venous catheterization* Mechanical ventilation* ICU admission Broad antibiotics use |

C. albicans (44.3%) NAC (42.2%) |

– | – | 38.7% (independent mortality risk factors*: mechanical ventilation, ICU admission, length of stay, C. albicans, CVC, severe sepsis, and septic shock) | [40] |

| Qatar | Candidemia | January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2010 | – | ˂ 1 to ˃ 60 y* (65.8% males) | 201 |

Malignancies (17% hematological and solid organ tumors) GI disease including surgery (13%) Renal diseases including transplant patients (11%) |

C. albicans (33.8%) C. glabrata (18.9%) C. tropicalis (17.9%) C. parapsilosis (16.9%) C. dubliniensis (1.5%) C. orthopsilosis (4%) M. guilliermondii (1%) |

Blood |

Molecular identification Biochemical identification MALDI-TOF MS |

Crude-mortality: 56.1% (Heart/pulmonary diseases-related (24%); Malignancies (hematological and solid organ tumors) (22.1%); GI (10.5%); Renal diseases (12.5%) |

[53] |

| Kuwait | Candidemia | 2014–2016 | 0.24 (2014), 0.16 (2015), and 0.15 (2016) cases/1000 patient-days | 59–66 y | 89 |

Diabetes (n = 41) Antimicrobial agent(s) prior to candidemia (n = 74) Vascular catheter (79%) Hemodialysis (12%) Total parenteral nutrition (15%) Abdominal surgery (20%) ICU admission (20%) |

C. albicans (32%) C. parapsilosis (32%) C. tropicalis (20%) C. glabrata (13%) C. dubliniensis (1%) C. famata (1%) C. auris (1%) |

– | – | 54% (related factors: ICU stay*, C. tropicalis*, abdominal surgery*) | [52] |

| Turkey | Candidemia | 2010–2016 | 0.10 to 0.30 cases/1000 patient-days | 45 y (55.1% males) | 351 |

ICU admission (58.7%) Underlying malignancy (35.6%) Central venous line (81.5%) Parenteral nutrition (55.8%) Major surgery (42.7%) |

C. albicans (48.1%) C. parapsilosis (25.1%) C. glabrata (11.7%) |

Blood | Culture | Total: 40.7% C. albicans (36.1%), and non-albicans Candida spp. (39.6%) | [135] |

| Turkey | – | January 2000 and December 2007 | 11.5 per 1000 NICU admissions | 28 |

Maternal pre-eclampsia Prematurity* Prolonged mechanical ventilation* Prolonged hospitalization* Prolonged total parenteral nutrition* Presence of jaundice. Retinopathy of prematurity Bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

C. parapsilosis (57.1%) C. albicans (42.9%) |

Blood | Culture | 42.8% | [45] | |

| Turkey | Nosocomial candidemia | June 30, 2007 and June 30, 2009 | – | 1–54 y (51.0% males) | 120 |

Pediatrics: Prematurity (25.5%) Neoplasia (17.6%) Infection (15.7%) Adults: Neoplasia (36.2%) Trauma (13.0%) Infection (17.4%) |

C. albicans (43.3%) C. parapsilosis (25.0%) C. tropicalis (17.5%) |

Blood | Culture | – | [136] |

| Iran | Candidemia | November 2016 to August 2017 | – | 48 ± 16.6 y (40% males) | 5 (6.25%) |

AML (80%) Central venous catheter (100%) |

Candida spp. | Blood | Culture | – | [137] |

| Iran | Candidemia | – | – | 46.80 ± 24.30 y | 55 |

Surgery* and burns (23.6%) Malignancies (20%) Broad-spectrum antibiotic use (18.2%) Diabetes (7.3%) |

C. parapsilosis (30.8%) C. albicans (27.3%) C. glabrata (18.2%) C. tropicalis (14.5%) |

– | – | – | [47] |

| Iran | Candidemia | May 2011–November 2013 | – | 48.2 ± 30.9 y (40% males) | – |

Cancer (20%) Diabetes (20%) Premature birth (20%) Multiple trauma and vast surgery (40%) Surgery, dialysis, diabetes, or renal failure (20%) |

C. albicans (50%) C. glabrata (40%) C. parapsilosis (10%) |

Blood |

Culture PCR |

60% | [138] |

| Egypt | Candidemia | – | 3 per 1000 inpatient-days | 6 m–15 y (54.5% males) | 88 |

Respiratory tract disease (15.2%) Neurological diseases (12.1%) Cardiovascular disease (9.1%) Nephropathy (4.5%) Endocrinopathy (3%) Chronic liver disease (1.5%) |

C. albicans (40%) C. parapsilosis (25%) C. tropicalis (17%) C. glabrata (8%) |

Blood | Culture | 16.7% | [54] |

| Tunisia | – | 1995 to 2010 | 12.2 cases/1000 admissions (average) | 25–41 w | 265 |

Broad-spectrum antibiotics (98.4%) Central catheter (68.3%) |

C. albicans (74.3%) C. parapsilosis (13.6%) C. glabrata (4.5%) C. tropicalis (3.8%) C. lusitaniae (1.5%) C. krusei (0.7%) C. guilliermondii (0.4%) C. pelliculosa (0.4%) C. ciferrii (0.4%) C. zeylanoides 1 (0.4) |

Blood (100) Central catheter (133) CSF (18) Peritoneal fluid (4) Hepatic abscess (4) Joint fluid (2) Intra-abdominal abscess (1) Mediastinal fluid (1) |

– | 63% | [56] |

| Tunisia | – | January 1995–December 2009 | 24 episodes per year (average) | – | 369 | – |

C. albicans (64.0%) C. parapsilosis (13.3%) C. tropicalis (11.6%) C. glabrata (5.4%) |

Normally sterile sites (blood, CSF, pleural, peritoneal, and joint fluids) Biopsy specimens from deep organs |

Culture Biochemical tests |

– | [55] |

C. albicans Candida albicans, C. glabrata, Candida glabrata, C. parapsilosis Candida parapsilosis, C. tropicalis Candida tropicalis, C. guilliermondii Candida guilliermondii, C. pelliculosa Candida pelliculosa, C. ciferrii Candida ciferrii, C. zeylanoides Candida zeylanoides, C. lusitaniae Candida lusitaniae, C. famata Candida famata, C. auris Candida auris; IFIs invasive fungal infections, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, GI gastrointestinal, ICU intensive care unit, NICU neonatal intensive care unit, AML acute myeloid leukemia, GI Gastrointestinal, MALDI-TOF MS Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, PCR polymerase chain reaction, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, CT computerized tomography, CVC central venous catheter, y years, m months, w weeks, KSA Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

*Significant association (p < 0.05)

Fig. 1.

Available estimates of the incidence rate (per 100,000 population) of invasive fungal infections in MENA countries [16–22]

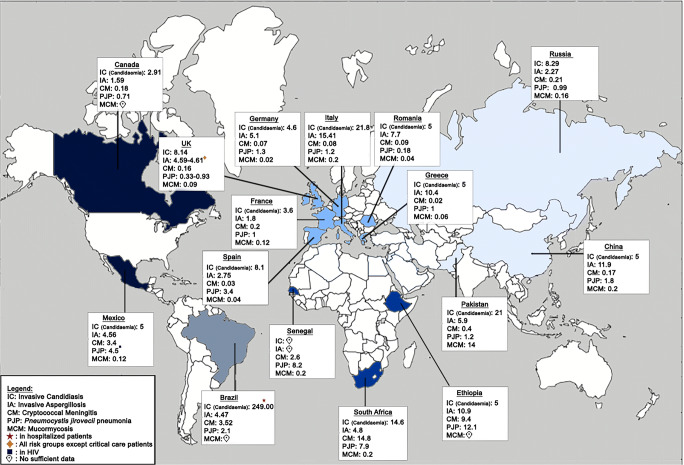

Fig. 2.

Available estimates of the incidence rate (per 100,000 population) of invasive fungal infections in different countries around the world [23–38]

As for the available epidemiological studies, only a few were found to assess the status of IC and candidemia. In Lebanon, only one study took place in the past 10 years. The study evaluating 2011–2012 data of three hospitals, with a mean of 2.2–2.5 co-morbid conditions per patient, has reported the incidence of IC to be 0.39 cases per 1000 hospital discharges [39]. In Jordan, an overall incidence rate of 0.48 episodes/1000 admissions was recorded in an academic tertiary hospital, with a 30-day mortality rate of 38.7% [40]. In Turkey, several studies have shown that nosocomial IC, including candidemia, ranged between 1.2/1000 and 5.6/1000 admissions [41–43]. The incidence of candidemia in ICUs ranged from 1.76 patients/1000 ICU admissions to 11.5 per 1000 neonatal ICU admissions among neonates [44, 45]. However, a prospective study in Iran indicated higher incidence rate of candidemia (15.2/1000 in neonatal ICU admissions), with a 42.5% mortality rate [46]. A systematic review and meta-analysis identified 55 cases of candidemia in Iran where the risk factors were surgery and burns (23.6%), malignancies (20%), use of broad-spectrum antibiotics (18.2%), and diabetes (7.3%) [47].

As for the Arabian Peninsula, it has been recorded in Saudi Arabia that IC rates ranged from 1.55–1.65 cases per 1000 discharges to 26 cases per 1000 ICU admissions [39, 48, 49]. A retrospective study on IC among pediatric patients indicated a group of risk factors: prematurity in 37 (28.7%) of patients, low birth weight (32.6%), central venous catheter (45.7%), malignancy (16.3%), immunotherapy (15.5%), and ventilator support (46.5%) [50]. In 2002–2009, data indicated that malignancy was independently associated with the development of candidemia [51]. In Kuwait, candidemia rate has decreased to a 0.15 cases/1000 in 2016 compared to 0.24 cases/1000 patient-days in 2014 [52]. In Qatar, 201 episodes of candidemia in 187 patients were identified in a single-center study [53].

In North Africa, candidemia in a pediatric ICU reached up to 3 per 1000 inpatient-days in Egypt [54]. A 15-year (1995–2009) retrospective analysis in the Sousse Region, Tunisia, had indicated an increase in the frequency of IC episodes, with an average of 24 episodes per year [55]. A previous study analyzing the data from 1995 to 2010 in the same region has shown an incidence of neonatal IC about 12.2 cases/1000 admissions, with a fourfold decrease of incidence from 2007 to 2010 [56]. A retrospective study of IFI among renal transplant recipients from January 1995 to February 2013 reported only 2 cases of IC [57]. In Morocco, 8-month prospective surveillance from January to August 2011 conducted at the Casablanca University Hospital—pediatric hematology/oncology unit—showed a healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) incidence of 28/1000 patient-days, where Candida accounted for 14% [58].

Some factors may have a probable role in the spread of IFIs among MENA countries. For instance, country socioeconomic status affects device-associated infection rates in developing countries and should be taken into account when comparing device-associated infections from one country to another [59]. In addition, the global share of the health research in the Eastern Mediterranean region is lower than the average percentage worldwide. The rise in academic health publications has been more common in only a few countries [60]. Furthermore, socio-political instabilities influence research output as well, such as in Egypt and Tunisia in the last few years. The concentration of biomedical and health research in the region’s academic institutions is expected to help turn information into public health results, if more suitable conditions are given [60].

Based on data published in the last decade regarding IC causative agents, C. albicans was found to be the most prevalent in Iran (80%) in a local study conducted in Tehran, followed by Turkey (48.3%), Kuwait (37.22–47.2%), and Qatar (30.2%) [61, 62]. According to Ghazi et al. [62], an increase in NAC is being observed in the MENA region, especially in Saudi Arabia (48.1%), Kuwait (52.8%), Egypt (60%), Qatar (69.3%), and Tunisia (~ 76.1%). A decrease in the NAC incidence was observed in Turkey (from 52.43 to 44%). With regard to the NAC distribution, C. tropicalis was prevalent in Saudi Arabia (15.5%), and Tunisia (37.7%), while C. glabrata predominated in Qatar (25.5%), Turkey (13.3%), and Iran (20%) and C. parapsilosis in Kuwait (38.2%) and Egypt (25%) [62].

Concerning C. auris, it was associated with IC, mostly candidemia, in the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia [52, 63–68]. Surprisingly, while C. auris isolation in Kuwait has steadily increased over a study period and almost doubled in 2018 compared to 2017, a noteworthy finding of nearly sixfold increase was in bloodstream C. auris isolates in the same period [68]. Unfortunately, no reports of C. auris were found form other MENA countries. In fact, C. auris is closely related to the species of the C. haemulonii complex, leading to a misidentification with other Candida species such as C. haemulonii or C. famata [69, 70]. Even though most of the region belong to the middle-income countries, the total mass of the publication of research is lower than its global proportion of population or income [60]. Most of the clinical microbiology laboratories in this geographic area are not yet supported with more advanced diagnostic tools that allow the extensive search for this agent, in contrary to the high-income countries, which reported and investigated to a certain extent the C. auris distribution. C. auris infection may be present in other countries as well, but its occurrence has not yet been investigated. Unfortunately, the insufficiency of conventional commercial systems to identify C. auris also leads to delayed intervention and treatment [70, 71]. This will definitely cause a threat in the healthcare settings, since this fungal agent can contaminate and prevail in hospital environments, in addition to transfer between patients, and from health workers and abiotic surfaces of medical equipment to patients [72].

Invasive aspergillosis

IA is an opportunistic fungal infection affecting primarily the immunocompromised population: 70% of the total putative or proven IA happens in immunocompromised patients, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or patients with diabetes admitted to the ICUs [73]. It is estimated that ~ 250,000 cases occur annually [10]. IA is associated with elevated hospital mortality, extended duration of hospitalization, and high costs [74]. The causative agent Aspergillus spp. is a ubiquitous environmental mold that is found on organic matter, soil, and in the air as conidia [75]. Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus terreus, and Aspergillus versicolor are the most common causative species, where A. fumigatus is the commonest agent worldwide [76]. Despite the growing concern of aspergillosis, it is not thoroughly reported in the majority of MENA countries (Table 2).

Table 2.

Epidemiology of invasive aspergillosis in the MENA region

| Country | Study period | Setting | Incidence | Age of patients (% gender) | Number of isolates | Predisposing condition(s) | Causative agent | Sample type | Diagnostic tool | Mortality rate | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lebanon and KSA | 2011–2012 | Five hospitals (3 in Lebanon and 2 in KSA) |

1.21 cases/1000 discharges (Lebanon) 0.4 cases/1000 discharges (KSA) |

55.2 ± 25.1 y (54.9% males) |

102 with IFIs |

Diabetes (41%) Coronary artery disease (24%) Leukemia (19%) Moderate to severe renal disease (16%) Congestive heart failure and chronic pulmonary disease (15%) |

A. fumigatus (60%) A. niger (10%) A. flavus (10%). |

– |

Culture Chest radiograph CT Galactomannan PCR |

IFIs-related (33%) | [39] |

| Bahrain | 2009—2013 | The Salmaniya Medical Complex | – | 52.85 y | 60 |

Diabetes (23%) COPD (17%) Malignancy (15%) SOT (2%) Corticosteroid therapy (23%) Radiotherapy/chemotherapy (12%) Immunosuppressive therapy (7%) |

A. fumigatus (53%) A. niger (28%) A. flavus (12%) Aspergillus spp. (7%) |

Sputum (50%) ETA (30%) BAL (20%) |

Gram stain Direct sputum smear Culture Chest X-ray/CT |

Colonized patients (25%) Probable cases (44%) Putative cases (32%) |

[78] |

| Tunisia | December 2009 to November 2011 | Farhat Hached Hospital | 7.5% | 1–65 y* | 56 |

ALL AML |

A. niger (35%) A. flavus (38%) A. tubingensis (19%) A. fumigatus (4%) A. westerdijkiae (2%) A. ochraceus (2%) |

– |

Microscopy MALDI-TOF MS PCR CT scan |

– | [80] |

| Tunisia | December 2004–September 2007) | Hedi Chaker Hospital | 15% | – | 1680 |

AML ALL Neutropenia Medullar aplasia |

A. flavus (79.2%) A. niger (10%) A. ochraceus (2.3%) A. fumigatus (2.3%) |

BAL Effusion drainage Biopsies |

Microscopy Galactomannan detection by ELISA PCR |

– | [81] |

A.fumigatus Apergillus fumigatus, A. niger Aspergillus niger, A. flavus Aspergillus flavus, A. ochraceus Aspergillus ochraceus, A. westerdjikiae Aspergillus westerdjikiae, A. tubingensis Aspergillus tubingensis, AML acute myeloid leukemia, ALL acute lymphocytic leukemia, SOT solid organ transplantation, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, BAL bronchoalveolar lavage, CT computerized tomography, MALDI-TOF MS matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, PCR polymerase chain reaction, ETA endotracheal aspiration, IFIs invasive fungal infections, y years, KSA Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

*Significant association (p < 0.05)

IA burden estimates have been done for several MENA countries, and the highest estimated incidence rate in Egypt is 10.7/100,000 [18], followed by Iran with 7.9/100,000 among COPD cases, 0.1/100,000 among lung cancer cases, and 0.03/100,000 among acute myeloid leukemia cases [17]. In Saudi Arabia, incidence rate was 7.6/100,000 [19], followed by Algeria (7.1/100,000) [20], Turkey (4.48/100,000) [21], Iraq (2.62/100,000) [77], Jordan (1.34/100,000) [22], and reached its lowest value (0.6/100,000) in Qatar [16]. Moreover, the incidence of IA in Lebanon was estimated at 1.21 cases/1000 hospital discharges, higher than that found in Saudi Arabia with 0.4 cases/1000 hospital discharges [39]. In Bahrain, medical records during 2009–2013 of a tertiary care hospital of patients with positive Aspergillus cultures revealed 53.3% colonization and 46.7% presumed IA associated with 25% and 32% mortality respectively [78]. In Tunisia, the incidence of IA was 7.5–15% among hematology patients [79–81]. A retrospective study of IFIs among renal transplant recipients at Habib Bourguiba Sfax university hospital from January 1995 to February 2013 reported 2 cases of aspergillosis [57]. Between 2002 and 2010, 29 cases of IA were reported in the Sousse Farhat Hached Hospital Hematology Unit, where acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was the most common disease (65.5%) among the severely neutropenic patients [82].

Regarding species distribution, A. fumigatus predominated in IFIs of hospital discharges in both Lebanon and Saudi Arabia (60%) [39] and was responsible for 53% of IA in Bahrain [78]. A. flavus was predominant in 75% of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples in Iran [83] and in 37.5% of sputum samples and 79.2% among clinical samples of hematology patients in Tunisia [81, 84].

Cryptococcal meningitis

Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common fungal agent that causing meningoencephalitis in the immunocompromised individuals worldwide [85], followed by Cryptococcus gatti [86]. C. neoformans is acquired through inhalation of spores or dried agent in the environment [87]. CM arises in 15% of AIDS-related mortality worldwide [88]. It is estimated that ~ 223,100 incident cases occur globally, with an estimation of 181,100 annual deaths [88].

Considering CM as a rare fungal infection, it could not be estimated in Jordan [22], Iraq [77], and Egypt [18], in addition to being estimated to probably be affecting under 10 patients in Saudi Arabia [19]. In Qatar, CM had a low estimated incidence rate of 0.43 cases per 100,000 considering the low human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) rate in the country [16]. In Turkey, the estimated rate was 0.13 per 100,000 population with the prediction of 106 annual cases occurring among HIV patients [21]. Similarly, the incidence rate in Iran was estimated at 0.14 per 100,000 population [17]. In Algeria, a nearly negligible rate of 0.09 per 100,000 population was estimated [20].

Overall, few cases of CM were reported in the MENA region. A case was observed in a Turkish female who has undergone mastectomy and has had received chemotherapy following surgery [89]. In addition, a rare case of tenosynovitis caused by Cryptococcus luteolus was reported in a 68-year-old type 2 diabetic male [90]. Regarding Iran, a review article reported a case of CM caused by C. neoformans in HIV-positive Iranian female who died 4 days after antifungal therapy due to respiratory failure in Sari. The authors have also included 12 other reported cases of cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus species between 1969 and 2014 [91]. Moreover, a study showed that the prevalence of cryptococcal infection in HIV-infected patients with a CD4 cell count of < 100 cells/mm3 was very low (< 3%) [92]. In fact, C. neoformans is highly prevalent in pigeon droppings in Iran, allowing its transmission to the environment and consequently to the patients at risk of developing CM [93, 94].

The first report of CM in the Arabian Peninsula was in Saudi Arabia in 1990, showing the occurrence of this disease in a child having systemic lupus erythematosus [95]. The only reported case from Kuwait was in 1995, considered the second in the Arabian Peninsula, in a 22-year-old man presented with confusional psychosis caused by C. neoformans serotype A [96]. However, in Oman, a study conducted between January 1999 and December 2008 showed that CM accounted for 22% of AIDS-defining opportunistic infections [97].

Regarding the North African region, 0.6% of CM cases were estimated among annually HIV-infected patients in Egypt [18]. The first cases of CM were reported in two HIV-positive patients in Libya [98]. In Morocco, a study that was conducted from January 2005 to May 2015 showed that CM accounted for 20% of neurological disorders involved that was suggestive of HIV infection in 68.8% cases [99]. A 2016 cross-sectional study in Tunisia declared that CM was responsible for 11% out of 70.4% deaths associated with HIV [100]. Among renal transplant recipients between January 1995 to February 2013, 2 cases of cryptococcosis were reported [57].

Pneumocystis pneumonia

Pneumocystis spp., a ubiquitous yeast-like fungus that affects a wide variety of mammals, is a host strict agent where P. jirovecii infects primarily humans [101]. The main transmission route is through inhalation; however, some evidence suggests a direct-contact transmission route [102]. PJP is widely known as an HIV-positive-related opportunistic fungal infection. However, because of the extensive use of immunosuppressant drugs, non-HIV risk groups have emerged, particularly among cancer patients [103].

Concerning incidence rate estimates, it could not be estimated in both Iraq and Saudi Arabia due to the lack of data on PJP infections [19, 77]. In Qatar, the estimated rate was 0.8 per 100,000 population [16], followed by Turkey 0.79 per 100,000 [21], Algeria 0.18 per 100,000 [20], Egypt 0.15 per 100,000 [18], and Jordan 0.1 per 100,000 [22] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Epidemiology of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in the MENA region

| Country | Study period | Setting | Incidence | Age of patients | Number of isolates | Predisposing condition(s) | Sample type | Diagnostic tool | Mortality rate | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lebanon | 1984 to January 2008 | American University of Beirut Medical Center | 10.9% | 35.4 y | 89 | HIV | – | – | – | [104] |

| Turkey | 2009–2015 | Ege University Hospital | – | 56.7 ± 15.3 y | 43 | CMV co-infection | BAL, sputum and endotracheal aspiration | Microscopy Real-time PCR |

PJP: 46.7% Co-infection: 78.6% |

[105] |

| Turkey | 1992–2009 | Erciyes University Hospital Infectious Diseases Clinics | – | 45 y | – | HIV/AIDS | – | – | – | [106] |

| Iran | 2011 | Imam Khomeini and army’s 501 hospitals | 39.3% (77.5% in AIDS group) | 19–58 y | 160 | AIDS, diabetes, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Serum | Indirect fluorescent antibody test | – | [107] |

| Iran | June 2010–December 2011 | National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (NRITLD) | 10.5% | Age: 23–65 | 153 | Malignancy under chemotherapy | BAL | Nested PCR | – | [108] |

| Iran | 2000–2015 | Imam Khomeini Hospital | 4.5% | 15–63 y | 177 | HIV/AIDS | – | – | – | [109] |

| Kuwait | January 2004 and December 2013 | Kuwait National Primary Immunodeficiency Disorders Registry | 8.3% | – | – | Primary immunodeficiency disorders | – | – | – | [110] |

| Bahrain | January 2009–May 2013 | Salmaniya Medical Complex (SMC) | 15.1% | 48.3 ± 11.6 y | 10 | HIV-positive patients | BAL | Direct antigen detection test using an immunofluorescence method | – | [111] |

| Oman | January 1999 and December 2008 | Sultan Qaboos University (SQU) Hospital | 25% | 37.5 y | 19 | HIV/AIDS | Sputum |

Microscopy Radiography High-resolution CT |

– | [97] |

| Libya | 2013 | Tripoli Medical Center | 8.8% | 40 y | 227 | HIV/AIDS | – | Clinical presentation chest X-ray/computerized tomography treatment response | 37.4% | [112] |

| Tunisia | January 2000 and August 2014 | Infectious Disease Services of Sousse and Monastir at the Tunisian Center | – | 40 ± 11 y | 213 | HIV/AIDS | – | – | HIV-related: 70.4% (pulmonary pneumpocystosis (11%)) | [100] |

PJP Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, AIDS acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, PCR polymerase chain reaction, BAL bronchoalveolar lavage, CMV cytomegalovirus, CT computerized tomography, y years

Case reports and epidemiological data on PJP were reported in few countries. A Lebanese report indicated a prevalence of 10.9% PJP cases among HIV patients [104]. In Turkey, the prevalence of PJP among AIDS/HIV patients ranged from 10 to 46.7% [104–106], while in Iran, PJP ranged from 4.5 to 39.3% [107–109]. Regarding the Arabian Peninsula region, PJP occurring in 9 episodes among primary immunodeficiency disorder patients in Kuwait [110] was found in 5.1% of total HIV-infected patients in Bahrain [111], while accounted for 25% of opportunistic infections in HIV/AIDS patients in Oman with no mortality reported due to this infection [97]. Concerning North Africa, a retrospective analysis in 2013 conducted on HIV-related hospitalizations showed that PJP was responsible for 8.8% respiratory diseases in Libya [112] and accounted for 11.1% death in HIV-infected patients in Tunisia [100]. Another retrospective study from January 1995 to February 2013 on IFIs reported 4 cases of pneumocystosis among renal transplant recipients [57].

Mucormycosis

Mucormycosis is an IFI ordinarily seen in individuals with underlying predisposing risk factors including DM and hematological malignancies. Disseminated forms are usually seen in individuals with such risk factors, although rhino-sinusoidal and cutaneous forms may occur in all individuals [113]. Causative agents belong to the subphylum Mucoromycotina. Rhizopus arrhizus is the most common agent causing mucormycosis globally. It is acquired through inhalation of sporangiospores [114]. The global estimates of mucormycosis were around > 10,000, with an estimate of disseminated mucormycosis around 100,000 [10].

Estimated incidence rates were scarce. The highest estimated rate was in Iran at 9.2 per 100,000 population [17], then in Iraq and Algeria at 0.2 per 100,000 [20, 77]. In Lebanon, an average incidence of 0.83 cases/10,000 admissions (range 0–2.22) was seen over a 10-year period in hospitalized patients, in addition to 20% mucormycosis-related deaths [115]. As for Turkey, 223 cases occurred in hematological malignancies patients and 214 cases in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis [21]. A 17-year assessment indicated 60% cases of rhino-cerebral and 1.9% disseminated forms of mucromycosis diagnosed in 151 patients, with 49% diabetes 39.7% hematological malignancies co-morbidities among them [116]. In Iran, a systematic review indicated that the commonest form was rhino-cerebral (48.9%) in addition to eight disseminated forms were identified which accounted for 75% of total mortality [117]. Another 10-year assessment indicated the prevalence of the rhino-cerebral form (95%) among the total diagnosed mucormycoses [118]. In addition, a case of rhino-orbital mucormycosis caused by Rhizopus oryzae was reported in an acute lymphoblastic leukemia patient [119]. Among children with hematological malignancies, mucoromycetes were responsible for 11.5% of IFIs and accounted for 53.3% mortality [120]. An overall incidence rate was estimated at 4.27 per 100 leukemia patients, which decreased from 2001 to 2011 [121].

Concerning the Arabian Peninsula, mucormycosis was estimated to probably being affecting less than 10 patients in Saudi Arabia [19]. A retrospective analysis has reported rhino-cerebral mucormycosis as a cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) [122]. Gangrenous necrotizing cutaneous mucormycosis in a female neonate who has had injuries on the scalp, abdomen, and back was reported in an ICU in Oman [123].

In North Africa, proven mucormycosis developed in 45 patients in which 90% of the cases had hematological malignancies in Egypt; in addition to mucormycosis-related complications in 5 cases with disfigurement and perforated hard palate. Mucormycosis-related mortality was 33% [124]. In December 2010, 3 out of 5 acute leukemia patients due to Rhizomucor outbreak [125]. Another study during 2010 reported 10 cases of mucormycosis, in which 80% had pulmonary mucormycosis and only 20% sinus involvement [126]. As for Tunisia, two patients had died after reporting rhino-cerebral, rhino-orbital, auricular, pulmonary, and cutaneous mucormycosis in one acute leukemia and 3 diabetic patients. The responsible Mucorales were R. arrhizus in 3 cases and Lichtheimia corymbifera in 2 cases. [127]. One mucormycosis was reported among 321 renal transplant recipients [57]. Surprisingly, considering the rarity of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, it was reported to be complicated by sinonasal mucormycosis in a diabetic child [128]. Retrospective analysis of data between 1992 and 2007 included 17 diabetic patients with rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis which resulted in 65% mortality primarily due to delay in diagnosis and the lack of surgical treatment [129] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Epidemiology of Mucormycosis in the MENA region

| Country | Clinical presentation | Study period | Setting | Incidence | Age of patients | Infected patients | Predisposing condition(s) | Agent | Diagnostic tool | Mortality rate | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lebanon |

Rhino-orbito-cerebral disease; Disseminated disease |

January 2008 and January 10, 2018 | American University of Beirut Medical Center | 0.83 cases/10,000 admissions | 17–79 y | 20 |

Hematological malignancies (acute myeloid, leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma) Allogenic-HSCT DM |

Rhizopus (44%) Mucorales spp. (44%) Lichtheimia spp. (12%) |

Histopathology Culture |

20% | [115] |

| Turkey | Rhino-cerebral infection (19.6%); Bone destruction (33.3%) | January 2003 to May 2013 | Çukurova University Hospital | – | 44.2 ± 18.2 y | 51 |

Hematologic malignancies (52.9%) DM (25.5%) Solid malignancies (5.8%) Renal transplantation (1.9%) Pregnancy (1.9%) |

– | – | 52.9% | [139] |

| Turkey |

Rhino-cerebral infection (60%); Disseminated infection (3.9%) |

1995 and 2012 | – | – | 45.4 ± 21.4 y | 151 |

Hematological malignancies (39.7%) Diabetes (49%) |

Mucor spp. (37.2%) Rhizopus spp. (31.4%) Mucoromycetes (17.6%) Rhizopus oryzae (7.8%) Rhizomucor spp. (3.9%) Rhizosporium spp. (1.9%) |

– | 54.3% | [116] |

| Iran | Rhino-cerebral mucormycosis (95%) | 2007 to 2017 | Imam Reza Hospital in Tabriz | – | 14–60 y | 40 | Diabetes (90%) | Rhizopus spp. (62.5%) | Clinical signs and symptoms, histopathology and culture | 42.5% | [118] |

| Iran | Upper respiratory system (50%); Oral (40%); External otitis (10%) | 2005 and 2010 | Ali-Asghar Children Hospital | 11.5% | 7.95 y | 10 | Hematological malignancies (ALL (72.5%), AML (17.3%), Hodgkin lymphoma (5.8%), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (2.2%), Burkitt’s lymphoma (1.1%)) | Mucoromycetes (11.5%) | Local biopsy and pathology | 53.3% | [120] |

| KSA |

Sinus involvement (76.3%); Rhino-cerebral (3.4%); Disseminated (8.5%); Sino-pulmonary (11.9%) |

2007–2017 | Children’s Cancer Hospital 57,357 | – | 8 y | 45 |

Solid tumors (11%) AML (49%) ALL (37%) CML post-allogenic transplant (2%) Neutropenia (90%) Steroids (35%) |

– |

Histopathology (84%) Culture (4%) Both (12%) |

33% | [124] |

DM diabetes mellitus, CML chronic myeloid leukemia, ALL acute lymphocytic leukemia, AML acute myeloid leukemia, KSA Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, allo-HSCT allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, y years

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus and causative agent of human histoplasmosis, causes respiratory and systemic mycoses in immunocompromised individuals [130]. The global burden of disseminated histoplasmosis is estimated to be ~ 100,000 annual cases [10]. The co-occurrence of histoplasmosis and tuberculosis in advanced HIV poses a diagnostic problem especially in histoplasmosis endemic regions [131]. Histoplasmosis is a known endemic mycoses of North America [132]; however, some reports were made from North Africa. In Morocco, a 39-year-old HIV-infected patient presented sinusitis and cutaneous histoplasmosis [133]. As well, a case of disseminated histoplasmosis caused by H. capsulatum was diagnosed in the bone marrow of a 34-year-old HIV-infected woman at Rabta Hospital of Tunis [134].

Concluding remarks

Despite the limited number of investigations dealing with the epidemiology of IFIs in this geographic area, the currently available data underlines that IFIs are not negligible. There is an urgent need for surveillance and implementation of recommendations and procedures in tertiary care centers in order to stem the morbidity and mortality related to IFIs, particularly among high-risk populations. Furthermore, a regional reference center for invasive mycoses and antifungals at the MENA region, with broad missions, is needed to promote the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship programs in this geographical area.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Basheer Al Bikai for his assistance in the design of the figure.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Marwan Osman and Aisha Al Bikai contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Enoch DA, Yang H, Aliyu SH, Micallef C. The changing epidemiology of invasive fungal infections. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1508:17–65. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6515-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muskett H, Shahin J, Eyres G, Harvey S, Rowan K, Harrison D. Risk factors for invasive fungal disease in critically ill adult patients: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2011;15:R287. doi: 10.1186/cc10574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuite NL, Lacey K. Overview of invasive fungal infections. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;968:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-257-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kabir V, Maertens J, Kuypers D. Fungal infections in solid organ transplantation: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2019;33:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornely OA, Gachot B, Akan H, Bassetti M, Uzun O, Kibbler C, Marchetti O, de Burghgraeve P, Ramadan S, Pylkkanen L, Ameye L, Paesmans M, Donnelly JP, EORTC Infectious Diseases Group Epidemiology and outcome of fungemia in a cancer cohort of the Infectious Diseases Group (IDG) of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC 65031) Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:324–331. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welte T, Len O, Muñoz P, Romani L, Lewis R, Perrella A. Invasive mould infections in solid organ transplant patients: modifiers and indicators of disease and treatment response. Infection. 2019;47:919–927. doi: 10.1007/s15010-019-01360-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole DC, Govender NP, Chakrabarti A, Sacarlal J, Denning DW. Improvement of fungal disease identification and management: combined health systems and public health approaches. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:e412–e419. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batzlaff CM, Limper AH. When to consider the possibility of a fungal infection: an overview of clinical diagnosis and laboratory approaches. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delaloye J, Calandra T. Invasive candidiasis as a cause of sepsis in the critically ill patient. Virulence. 2014;5:161–169. doi: 10.4161/viru.26187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bongomin F, Gago S, Oladele RO, Denning DW (2017) Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases-estimate precision. J Fungi (Basel) 3. 10.3390/jof3040057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Guinea J. Global trends in the distribution of Candida species causing candidemia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(Suppl 6):5–10. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miceli MH, Díaz JA, Lee SA. Emerging opportunistic yeast infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:142–151. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sears D, Schwartz BS. Candida auris: an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;63:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coste AT, Imbert C, Hennequin C. Candida auris, an emerging and disturbing yeast. J Mycol Med. 2019;29:105–106. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bidaud AL, Chowdhary A, Dannaoui E. Candida auris: an emerging drug resistant yeast—a mini-review. J Mycol Med. 2018;28:568–573. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taj-Aldeen SJ, Chandra P, Denning DW. Burden of fungal infections in Qatar. Mycoses. 2015;58(Suppl 5):51–57. doi: 10.1111/myc.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedayati M, Tagizadeh M, Charati J, Denning D. Burden of serious fungal infection in Iran. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;12:910–918. doi: 10.3855/jidc.10476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaki SM, Denning DW. Serious fungal infections in Egypt. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:971–974. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-2929-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albarrag AM, Al-Abdely H, Abu Khalid NF, Denning DW. Burden of serious fungal infections in Saudi Arabia

- 20.Chekiri-Talbi M, Denning DW. Burden of fungal infections in Algeria. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:999–1004. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-2917-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilmioğlu-Polat S, Seyedmousavi S, Ilkit M, Hedayati MT, Inci R, Tumbay E, Denning DW. Estimated burden of serious human fungal diseases in Turkey. Mycoses. 2019;62:22–31. doi: 10.1111/myc.12842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wadi J, Denning DW (2018) Burden of serious fungal infections in Jordan. J Fungi (Basel). 4. 10.3390/jof4010015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Dufresne SF, Cole DC, Denning DW, Sheppard DC. Serious fungal infections in Canada. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:987–992. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-2922-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giacomazzi J, Baethgen L, Carneiro LC, Millington MA, Denning DW, Colombo AL, Pasqualotto AC, Association With The LIFE Program The burden of serious human fungal infections in Brazil. Mycoses. 2016;59:145–150. doi: 10.1111/myc.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corzo-León DE, Armstrong-James D, Denning DW. Burden of serious fungal infections in Mexico. Mycoses. 2015;58(Suppl 5):34–44. doi: 10.1111/myc.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klimko N, Kozlova Y, Khostelidi S, Shadrivova O, Borzova Y, Burygina E, Vasilieva N, Denning DW. The burden of serious fungal diseases in Russia. Mycoses. 2015;58(Suppl 5):58–62. doi: 10.1111/myc.12388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mareș M, Moroti-Constantinescu VR, Denning DW (2018) The burden of fungal diseases in Romania. J Fungi (Basel). 4. 10.3390/jof4010031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Jabeen K, Farooqi J, Mirza S, Denning D, Zafar A. Serious fungal infections in Pakistan. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:949–956. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-2919-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu LP, Wu JQ, Denning DW (2013) Burden of serious fungal infections in China

- 30.Ruhnke M, Groll AH, Mayser P, Ullmann AJ, Mendling W, Hof H, Denning DW, University of Manchester in association with the LIFE program Estimated burden of fungal infections in Germany. Mycoses. 2015;58(Suppl 5):22–28. doi: 10.1111/myc.12392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pegorie M, Denning DW, Welfare W. Estimating the burden of invasive and serious fungal disease in the United Kingdom. J Inf Secur. 2017;74:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz I, Denning D. The estimated burden of fungal diseases in South Africa. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2019;12:124. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tufa TB, Denning DW (2019) The burden of fungal infections in Ethiopia. J Fungi (Basel). 5. 10.3390/jof5040109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Badiane AS, Ndiaye D, Denning DW. Burden of fungal infections in Senegal. Mycoses. 2015;58(Suppl 5):63–69. doi: 10.1111/myc.12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gamaletsou MN, Drogari-Apiranthitou M, Denning DW, Sipsas NV. An estimate of the burden of serious fungal diseases in Greece. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35:1115–1120. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bassetti M, Carnelutti A, Peghin M, et al. Estimated burden of fungal infections in Italy. J Inf Secur. 2018;76:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gangneux J-P, Bougnoux M-E, Hennequin C, Godet C, Chandenier J, Denning DW, Dupont B, LIFE program, the Société française de mycologie médicale SFMM-study group An estimation of burden of serious fungal infections in France. J Mycol Med. 2016;26:385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Gago S, Cuenca-Estrella M, León C, Miro JM, Nuñez Boluda A, Ruiz Camps I, Sole A, Denning DW. Burden of serious fungal infections in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moghnieh R, Alothman AF, Althaqafi AO, Matar MJ, Alenazi TH, Farahat F, Corman SL, Solem CT, Raghubir N, Macahilig C, Stephens JM. Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal infections and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) pneumonia and complicated skin and soft tissue infections (cSSTI) in Lebanon and Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10:849–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ababneh M, Abu-Bdair OA, Mhaidat N, Almomani BA. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of patients with Candida bloodstream infections in a tertiary care hospital in Jordan. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2017;11:861–867. doi: 10.3855/jidc.8634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kazak E, Akın H, Ener B, Sığırlı D, Özkan Ö, Gürcüoğlu E, Yılmaz E, Çelebi S, Akçağlar S, Akalın H. An investigation of Candida species isolated from blood cultures during 17 years in a university hospital. Mycoses. 2014;57:623–629. doi: 10.1111/myc.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutcu M, Salman N, Akturk H, Dalgıc N, Turel O, Kuzdan C, Kadayifci EK, Sener D, Karbuz A, Erturan Z, Somer A. Epidemiologic and microbiologic evaluation of nosocomial infections associated with Candida spp in children: a multicenter study from Istanbul, Turkey. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44:1139–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeşilkaya A, Azap Ö, Aydın M, Akçil Ok M. Epidemiology, species distribution, clinical characteristics and mortality of candidaemia in a tertiary care university hospital in Turkey, 2007-2014. Mycoses. 2017;60:433–439. doi: 10.1111/myc.12618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tukenmez Tigen E, Bilgin H, Perk Gurun H, Dogru A, Ozben B, Cerikcioglu N, Korten V. Risk factors, characteristics, and outcomes of candidemia in an adult intensive care unit in Turkey. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45:e61–e63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Celebi S, Hacimustafaoglu M, Koksal N, Ozkan H, Cetinkaya M, Ener B. Neonatal candidiasis: results of an 8 year study. Pediatr Int. 2012;54:341–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Charsizadeh A, Mirhendi H, Nikmanesh B, Eshaghi H, Makimura K. Microbial epidemiology of candidaemia in neonatal and paediatric intensive care units at the Children’s Medical Center, Tehran. Mycoses. 2018;61:22–29. doi: 10.1111/myc.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vaezi A, Fakhim H, Khodavaisy S, Alizadeh A, Nazeri M, Soleimani A, Boekhout T, Badali H. Epidemiological and mycological characteristics of candidemia in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Mycol Med. 2017;27:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Omrani AS, Makkawy EA, Baig K, Baredhwan AA, Almuthree SA, Elkhizzi NA, Albarrak AM. Ten-year review of invasive Candida infections in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2014;35:821–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Dorzi HM, Sakkijha H, Khan R, Aldabbagh T, Toledo A, Ntinika P, Al Johani SM, Arabi YM (2018) Invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients: a prospective cohort study in two tertiary care centers. J Intensive Care Med 885066618767835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Almooosa Z, Ahmed GY, Omran A, AlSarheed A, Alturki A, Alaqeel A, Alshehri M, Alfawaz T, AlShahrani D. Invasive candidiasis in pediatric patients at kIng Fahad Medical City in Central Saudi Arabia. A 5-year retrospective study. Saudi Med J. 2017;38:1118–1124. doi: 10.15537/smj.2017.11.21116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al Thaqafi AHO, Farahat FM, Al Harbi MI, Al Amri AFW, Perfect JR. Predictors and outcomes of Candida bloodstream infection: eight-year surveillance, western Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;21:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alobaid K, Khan Z. Epidemiologic characteristics of adult candidemic patients in a secondary hospital in Kuwait: a retrospective study. J Mycol Med. 2019;29:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taj-Aldeen SJ, Kolecka A, Boesten R, Alolaqi A, Almaslamani M, Chandra P, Meis JF, Boekhout T. Epidemiology of candidemia in Qatar, the Middle East: performance of MALDI-TOF MS for the identification of Candida species, species distribution, outcome, and susceptibility pattern. Infection. 2014;42:393–404. doi: 10.1007/s15010-013-0570-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hegazi M, Abdelkader A, Zaki M, El-Deek B. Characteristics and risk factors of candidemia in pediatric intensive care unit of a tertiary care children’s hospital in Egypt. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:624–634. doi: 10.3855/jidc.4186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saghrouni F, Bougmiza I, Ben Abdeljelil J, Yacoub A, Khammari I, Fathallah A, Mtiraoui A, Ben Saïd M. Epidemiological trends in invasive candidiasis: results from a 15-year study in Sousse Region, Tunisia. J Mycol Med. 2011;21:123–129. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ben Abdeljelil J, Saghrouni F, Nouri S, Geith S, Khammari I, Fathallah A, Sboui H, Ben Saïd M. Neonatal invasive candidiasis in Tunisian hospital: incidence, risk factors, distribution of species and antifungal susceptibility. Mycoses. 2012;55:493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2012.02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trabelsi H, Néji S, Sellami H, Yaich S, Cheikhrouhou F, Guidara R, Charffedine K, Makni F, Hachicha J, Ayadi A. Invasive fungal infections in renal transplant recipients: about 11 cases. J Mycol Med. 2013;23:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2013.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cherkaoui S, Lamchahab M, Samira H, Zerouali K, Madani A, Benchekroun S, Quessar A. Healthcare-associated infections in a paediatric haematology/oncology unit in Morocco. Sante Publique. 2014;26:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosenthal VD, Jarvis WR, Jamulitrat S, Silva CP, Ramachandran B, Dueñas L, Gurskis V, Ersoz G, Novales MG, Khader IA, Ammar K, Guzmán NB, Navoa-Ng JA, Seliem ZS, Espinoza TA, Meng CY, Jayatilleke K, International Nosocomial Infection Control Members Socioeconomic impact on device-associated infections in pediatric intensive care units of 16 limited-resource countries: international Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium findings. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:399–406. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318238b260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tadmouri GO, Mandil A, Rashidian A. Biomedical and health research geography in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25:728–743. doi: 10.26719/emhj.19.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khan Z, Ahmad S, Al-Sweih N, et al. Changing trends in epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility patterns of six bloodstream Candida species isolates over a 12-year period in Kuwait. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0216250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghazi S, Rafei R, Osman M, El Safadi D, Mallat H, Papon N, Dabboussi F, Bouchara J-P, Hamze M. The epidemiology of Candida species in the Middle East and North Africa. J Mycol Med. 2019;29:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2019.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alatoom A, Sartawi M, Lawlor K, AbdelWareth L, Thomsen J, Nusair A, Mirza I. Persistent candidemia despite appropriate fungal therapy: first case of Candida auris from the United Arab Emirates. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;70:36–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khan Z, Ahmad S, Al-Sweih N, Joseph L, Alfouzan W, Asadzadeh M. Increasing prevalence, molecular characterization and antifungal drug susceptibility of serial Candida auris isolates in Kuwait. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khan Z, Ahmad S, Benwan K, Purohit P, al-Obaid I, Bafna R, Emara M, Mokaddas E, Abdullah AA, al-Obaid K, Joseph L. Invasive Candida auris infections in Kuwait hospitals: epidemiology, antifungal treatment and outcome. Infection. 2018;46:641–650. doi: 10.1007/s15010-018-1164-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abdalhamid B, Almaghrabi R, Althawadi S, Omrani A. First report of Candida auris infections from Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11:598–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elsawy A, Alquthami K, Alkhutani N, Marwan D, Abbas A. The second confirmed case of Candida auris from Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2019;12:907–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ahmad S, Khan Z, Al-Sweih N, Alfouzan W, Joseph L. Candida auris in various hospitals across Kuwait and their susceptibility and molecular basis of resistance to antifungal drugs. Mycoses. 2019;63:104–112. doi: 10.1111/myc.13022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee WG, Shin JH, Uh Y, Kang MG, Kim SH, Park KH, Jang H-C. First three reported cases of nosocomial fungemia caused by Candida auris. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3139–3142. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00319-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kathuria S, Singh PK, Sharma C, Prakash A, Masih A, Kumar A, Meis JF, Chowdhary A. Multidrug-resistant Candida auris misidentified as Candida haemulonii: characterization by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry and DNA sequencing and its antifungal susceptibility profile variability by Vitek 2, CLSI broth microdilution, and Etest method. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:1823–1830. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00367-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morales-López SE, Parra-Giraldo CM, Ceballos-Garzón A, Martínez HP, Rodríguez GJ, Álvarez-Moreno CA, Rodríguez JY. Invasive infections with multidrug-resistant yeast Candida auris, Colombia. Emerging Infect Dis. 2017;23:162–164. doi: 10.3201/eid2301.161497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.(2019) Candida auris: a drug-resistant germ that spreads in healthcare facilities | Candida auris | Fungal Diseases | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/c-auris-drug-resistant.html. Accessed 6 Mar 2020

- 73.Taccone FS, Van den Abeele A-M, Bulpa P, et al. Epidemiology of invasive aspergillosis in critically ill patients: clinical presentation, underlying conditions, and outcomes. Crit Care. 2015;19:7. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0722-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zilberberg MD, Nathanson BH, Harrington R, Spalding JR, Shorr AF. Epidemiology and outcomes of hospitalizations with invasive aspergillosis in the United States, 2009-2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:727–735. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barnes PD, Marr KA. Aspergillosis: spectrum of disease, diagnosis, and treatment. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2006;20(545–561):vi. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sugui JA, Kwon-Chung KJ, Juvvadi PR, Latgé J-P, Steinbach WJ. Aspergillus fumigatus and related species. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;5:a019786. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Karzan MA, Ismael HM, Shekhany K, Al-Attraqhchi AAF, Abdullah S, Aldabbagh R, Denning DW (2014) Burden of serious fungal infection in Iraq

- 78.Alsalman J, Zaid T, Makhlooq M, Madan M, Mohamed Z, Alarayedh A, Ghareeb A, Kamal N. A retrospective study of the epidemiology and clinical manifestation of invasive aspergillosis in a major tertiary care hospital in Bahrain. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gheith S, Ranque S, Bannour W, Ben Youssef Y, Khelif A, Ben Said M, Njah M, Saghrouni F. Hospital environment fungal contamination and aspergillosis risk in acute leukaemia patients in Sousse (Tunisia) Mycoses. 2015;58:337–342. doi: 10.1111/myc.12320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gheith S, Saghrouni F, Bannour W, Ben Youssef Y, Khelif A, Normand A-C, Ben Said M, Piarroux R, Njah M, Ranque S. Characteristics of invasive aspergillosis in neutropenic haematology patients (Sousse, Tunisia) Mycopathologia. 2014;177:281–289. doi: 10.1007/s11046-014-9742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hadrich I, Makni F, Sellami H, Cheikhrouhou F, Sellami A, Bouaziz H, Hdiji S, Elloumi M, Ayadi A. Invasive aspergillosis: epidemiology and environmental study in haematology patients (Sfax, Tunisia) Mycoses. 2010;53:443–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saghrouni F, Ben Youssef Y, Gheith S, Bouabid Z, Ben Abdeljelil J, Khammari I, Fathallah A, Khlif A, Ben Saïd M. Twenty-nine cases of invasive aspergillosis in neutropenic patients. Med Mal Infect. 2011;41:657–662. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zanganeh E, Zarrinfar H, Rezaeetalab F, Fata A, Tohidi M, Najafzadeh MJ, Alizadeh M, Seyedmousavi S. Predominance of non-fumigatus Aspergillus species among patients suspected to pulmonary aspergillosis in a tropical and subtropical region of the Middle East. Microb Pathog. 2018;116:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gheith S, Saghrouni F, Bannour W, Ben Youssef Y, Khelif A, Normand A-C, Piarroux R, Ben Said M, Njah M, Ranque S (2014) In vitro susceptibility to amphotericin B, itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole and caspofungin of Aspergillus spp. isolated from patients with haematological malignancies in Tunisia. Springerplus 3:19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Loyse A, Thangaraj H, Easterbrook P, Ford N, Roy M, Chiller T, Govender N, Harrison TS, Bicanic T. Cryptococcal meningitis: improving access to essential antifungal medicines in resource-poor countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:629–637. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Galanis E, MacDougall L, Kidd S, Morshed M. Epidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii, British Columbia, Canada, 1999–2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:251–257. doi: 10.3201/eid1602.090900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lin X, Heitman J. The biology of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2006;60:69–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rajasingham R, Smith RM, Park BJ, Jarvis JN, Govender NP, Chiller TM, Denning DW, Loyse A, Boulware DR. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: an updated analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:873–881. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30243-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Taşbakan MS, Yamazhan T, Aydemir S, Bacakoğlu F. A case of ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by Cupriavidus pauculus. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2010;44:127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hunter-Ellul L, Schepp ED, Lea A, Wilkerson MG. A rare case of Cryptococcus luteolus-related tenosynovitis. Infection. 2014;42:771–774. doi: 10.1007/s15010-014-0593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Badali H, Alian S, Fakhim H, Falahatinejad M, Moradi A, Mohammad Davoudi M, Hagen F, Meis JF. Cryptococcal meningitis due to Cryptococcus neoformans genotype AFLP1/VNI in Iran: a review of the literature. Mycoses. 2015;58:689–693. doi: 10.1111/myc.12415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hajiabdolbaghi M, Kalantari S, Jamshidi-Makiani M, Shojaei E, Abbasian L, Rasoulinezhad M, Tayeri K. Prevalence of cryptococcal antigen positivity among HIV infected patient with CD4 cell count less than 100 of Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran, Iran. Iran J Microbiol. 2017;9:119–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Agha Kuchak Afshari S, Shokohi T, Aghili R, Badali H. Epidemiology and molecular characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans isolated from pigeon excreta in Mazandaran Province, Northern Iran. J Mycol Med. 2012;22:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ghaderi Z, Eidi S, Razmyar J. High prevalence of Cryptococcus neoformans and isolation of other opportunistic fungi from pigeon (Columba livia) droppings in Northeast Iran. J Avian Med Surg. 2019;33:335–339. doi: 10.1647/2018-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Al-Rasheed SA, Al-Fawaz IM. Cryptococcal meningitis in a child with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1990;10:323–326. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1990.11747452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sa’adah MA, Araj GF, Diab SM, Nazzal M. Cryptococcal meningitis and confusional psychosis. A case report and literature review. Trop Geogr Med. 1995;47:224–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Balkhair AA, Al-Muharrmi ZK, Ganguly S, Al-Jabri AA. Spectrum of AIDS defining opportunistic infections in a series of 77 hospitalised HIV-infected Omani patients. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2012;12:442–448. doi: 10.12816/0003169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ellabib MS, Krema ZA, Allafi AA, Cogliati M. First report of two cases of cryptococcosis in Tripoli, Libya, infected with Cryptococcus neoformans isolates present in the urban area. J Mycol Med. 2017;27:421–424. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2017.04.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.El Fane M, Sodqi M, Lamdini H, Marih L, Lahsen AO, Chakib A, El Filali KM. Central neurological diagnosis in patients infected with HIV in the infectious diseases unit of University Hospital of Casablanca, Morocco. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2018;111:24–30. doi: 10.3166/bspe-2018-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chelli J, Bellazreg F, Aouem A, Hattab Z, Mesmia H, Lasfar NB, Hachfi W, Masmoudi T, Chakroun M, Letaief A. Causes of death in patients with HIV infection in two Tunisian medical centers. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:105. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.25.105.9748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ma L, Cissé OH, Kovacs JA (2018) A molecular window into the biology and epidemiology of Pneumocystis spp. Clin Microbiol Rev 31. 10.1128/CMR.00009-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.Icenhour CR, Rebholz SL, Collins MS, Cushion MT. Early acquisition of Pneumocystis carinii in neonatal rats as evidenced by PCR and oral swabs. Eukaryot Cell. 2002;1:414–419. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.3.414-419.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Patterson L, Coyle P, Curran T, Verlander NQ, Johnston J. Changing epidemiology of Pneumocystis pneumonia, Northern Ireland, UK and implications for prevention, 1 July 2011-31 July 2012. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66:1650–1655. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Naba MR, Kanafani ZA, Awar GN, Kanj SS. Profile of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected patients at a tertiary care center in Lebanon. J Infect Public Health. 2010;3:130–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Korkmaz Ekren P, Töreyin ZN, Nahid P, Doskaya M, Caner A, Turgay N, Zeytinoglu A, Toz S, Bacakoglu F, Guruz Y, Erensoy S. The association between Cytomegalovirus co-infection with Pneumocystis pneumonia and mortality in immunocompromised non-HIV patients. Clin Respir J. 2018;12:2590–2597. doi: 10.1111/crj.12961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Alp E, Bozkurt I, Doğanay M. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of HIV/AIDS patients followed-up in Cappadocia region: 18 years experience. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2011;45:125–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Homayouni MM, Behniafar H, Mehbod ASA, Mohammad-Sadeghi M-J, Maleki B. Prevalence of Pneumocystis jirovecii among immunocompromised patients in hospitals of Tehran City, Iran. J Parasit Dis. 2017;41:850–853. doi: 10.1007/s12639-017-0901-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sheikholeslami MF, Sadraei J, Farnia P, Forozandeh M, Emadi Kochak H, Tabarsi P, Nadji SA, Pirestani M, Masjedi MR, Velayati A. Colonization of Pneumocystis jirovecii in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients and the rate of Pneumocystis pneumonia in Iranian non-HIV(+) immunocompromised patients. Iran J Microbiol. 2013;5:411–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Alinaghi SAS, Vaghari B, Roham M, Badie BM, Jam S, Foroughi M, Djavid GE, Hajiabdolbaghi M, Hosseini M, Mohraz M, McFarland W. Respiratory complications in Iranian hospitalized patients with HIV/AIDS. Tanaffos. 2011;10:49–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Owayed A, Al-Herz W. Sinopulmonary complications in subjects with primary immunodeficiency. Respir Care. 2016;61:1067–1072. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Saeed NK, Farid E, Jamsheer AE. Prevalence of opportunistic infections in HIV-positive patients in Bahrain: a four-year review (2009-2013) J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015;9:60–69. doi: 10.3855/jidc.4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Shalaka NS, Garred NA, Zeglam HT, Awasi SA, Abukathir LA, Altagdi ME, Rayes AA. Clinical profile and factors associated with mortality in hospitalized patients with HIV/AIDS: a retrospective analysis from Tripoli Medical Centre, Libya, 2013. East Mediterr Health J. 2015;21:635–646. doi: 10.26719/2015.21.9.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Krishnappa D, Naganur S, Palanisamy D, Kasinadhuni G (2019) Cardiac mucormycosis: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep 3. 10.1093/ehjcr/ytz130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 114.Richardson M. The ecology of the Zygomycetes and its impact on environmental exposure. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(Suppl 5):2–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.El Zein S, El-Cheikh J, El Zakhem A, Ibrahim D, Bazarbachi A, Kanj SS. Mucormycosis in hospitalized patients at a tertiary care center in Lebanon: a case series. Infection. 2018;46:811–821. doi: 10.1007/s15010-018-1195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zeka AN, Taşbakan M, Pullukçu H, Sipahi OR, Yamazhan T, Arda B. Evaluation of zygomycosis cases by pooled analysis method reported from Turkey. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2013;47:708–716. doi: 10.5578/mb.5836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Vaezi A, Moazeni M, Rahimi MT, de Hoog S, Badali H. Mucormycosis in Iran: a systematic review. Mycoses. 2016;59:402–415. doi: 10.1111/myc.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nezafati S, Kazemi A, Asgari K, Bahrami A, Naghili B, Yazdani J. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis, risk factors and the type of oral manifestations in patients referred to a University Hospital in Tabriz, Iran 2007-2017. Mycoses. 2018;61:764–769. doi: 10.1111/myc.12802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gumral R, Yildizoglu U, Saracli MA, Kaptan K, Tosun F, Yildiran ST. A case of rhinoorbital mucormycosis in a leukemic patient with a literature review from Turkey. Mycopathologia. 2011;172:397–405. doi: 10.1007/s11046-011-9449-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ansari S, Shirzadi E, Elahi M. The prevalence of fungal infections in children with hematologic malignancy in Ali-Asghar Children Hospital between 2005 and 2010. Iran J Ped Hematol Oncol. 2015;5:1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sarvestani SA, Pishdad G, Bolandparvaz S. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of mucormycosis in patients with leukemia; a 21-year experience from Southern Iran. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2014;2:38–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kajtazi NI, Zimmerman VA, Arulneyam JC, Al-Shami SY, Al-Senani FM. Cerebral venous thrombosis in Saudi Arabia. Clinical variables, response to treatment, and outcome. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2009;14:349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sawardekar KP. Gangrenous necrotizing cutaneous mucormycosis in an immunocompetent neonate: a case report from Oman. J Trop Pediatr. 2018;64:548–552. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmx094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Khedr R, Madney Y, Ahmed N, El-Mahallawy H, Yousef A, Taha H, Hassanain O, Taha G, Hafez H (2019) Overview and outcome of mucormycosis among children with cancer; Report From The Children’s Cancer Hospital Egypt Mycoses 10.1111/myc.12915, 62, 984, 989 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 125.El-Mahallawy HA, Khedr R, Taha H, Shalaby L, Mostafa A. Investigation and Management of a Rhizomucor Outbreak in a Pediatric Cancer Hospital in Egypt. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:171–173. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zaki SM, Elkholy IM, Elkady NA, Abdel-Ghany K. Mucormycosis in Cairo, Egypt: review of 10 reported cases. Med Mycol. 2014;52:73–80. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2013.809629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Bellazreg F, Hattab Z, Meksi S, Mansouri S, Hachfi W, Kaabia N, Ben Said M, Letaief A. Outcome of mucormycosis after treatment: report of five cases. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;6:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bahloul M, Tounsi A, Chaari A, Ben Aljia N, Ammar R, Chelly H, Bouaziz M. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis complicated by hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: case report from Tunisia. Med Sante Trop. 2012;22:210–212. doi: 10.1684/mst.2012.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Anane S, Kaouech E, Belhadj S, Ammari L, Abdelmalek R, Ben Chaabane T, Ben Lakhal S, Cherif A, Ammamou M, Ben Fadhel K, Kallel K, Chaker E. Rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis in the diabetic: a better known pathology in Tunisia. Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 2009;67:325–332. doi: 10.1684/abc.2009.0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ (2014) Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases, 8th ed.

- 131.Caceres DH, Valdes A (2019) Histoplasmosis and tuberculosis co-occurrence in people with advanced HIV. J Fungi (Basel). 5. 10.3390/jof5030073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 132.Armstrong PA, Jackson BR, Haselow D, Fields V, Ireland M, Austin C, Signs K, Fialkowski V, Patel R, Ellis P, Iwen PC, Pedati C, Gibbons-Burgener S, Anderson J, Dobbs T, Davidson S, McIntyre M, Warren K, Midla J, Luong N, Benedict K. Multistate epidemiology of histoplasmosis, United States, 2011-2014. Emerging Infect Dis. 2018;24:425–431. doi: 10.3201/eid2403.171258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Elansari R, Abada R, Rouadi S, Roubal M, Mahtar M. Histoplasma capsulatum sinusitis: possible way of revelation to the disseminated form of histoplasmosis in HIV patients: case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;24:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fakhfakh N, Abdelmlak R, Aissa S, Kallel A, Boudawara Y, Bel Hadj S, Ben Romdhane N, Touiri Ben Aissa H, Kallel K. Disseminated histoplasmosis diagnosed in the bone marrow of an HIV-infected patient: first case imported in Tunisia. J Mycol Med. 2018;28:211–214. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ulu Kilic A, Alp E, Cevahir F, Ture Z, Yozgat N. Epidemiology and cost implications of candidemia, a 6-year analysis from a developing country. Mycoses. 2017;60:198–203. doi: 10.1111/myc.12582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Birinci A, Cayci YT, Bilgin K, Gunaydin M, Acuner C, Esen S. Comparison of nosocomial candidemia of pediatric and adult cases in 2-years period at a Turkish university hospital. Eurasian J Med. 2011;43:87–91. doi: 10.5152/eajm.2011.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Yousefi M, Yadegarynia D, Lotfali E, Arab-Mazar Z, Ghajari A, Fatemi A. Candidemia in febrile neutropenic patients; a brief report. Emerg (Tehran) 2018;6:e39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]