Introduction

Epicenters of opioid addiction and drug related harms are shifting in the U.S., from cities to rural areas. The communities nested in Appalachian Kentucky are enduring escalating rates of hepatitis C (HCV), overdose, and other harms related to rising tides of prescription opioid (PO) and heroin use among young adults [1-3]. Between 2006 and 2012, the prevalence of HCV among people under 30 years of age in Central Appalachia grew 364%, alongside a 21.1% increase in admissions to drug treatment facilities for opioid dependency [4].

Research on the social-ecological determinants of HCV among people who inject drugs (PWID) in the rural U.S. is lacking. The Risk Environment Framework (REF) is a conceptual model that identifies economic, physical, social, and political determinants of drug-related harms, operating at intersecting micro and macro levels of social ecologies, in order to rapidly mobilize community-based and intersectoral interventions for marginalized groups [5, 6]. Cooper et al. expanded REF to include healthcare and law enforcement as distinct environmental domains [7-9]. REF posits that accountability for drug-related harms extends upstream, beyond the agency of individuals, and into realms of power, policy, and social forces binding systems, institutions, and societies [5, 6]. REF scholarship has proved vital in the design, implementation, and expansion of multi-level, intersectoral harm reduction policies and interventions worldwide[10].

To date, most REF studies have focused on urban and metropolitan settings, especially studies of drug use in the U.S. [8, 11-15]. Due to recent shifts in the dynamics of drug-related harms, from densely-populated urban centers to sparsely-inhabited rural regions, new REF-informed studies are needed to examine how properties of rural environments shape vulnerabilities to risky drug use and injection behaviors that lead to HCV [4,16-19]. Such research is necessary for accelerating the implementation of laws, policies, and programs tailored to the contextual contours of PWID living in rural places [5, 6].

Setting

Appalachia is a vast region of the U.S. landmass, where 25 million people live within 420 counties, spanning 205,000-square-miles that encompass all of West Virginia and segments of 11 other states [20]. About 42 % of Appalachia is designated as rural. Rural Eastern Kentucky is among the most impoverished areas of Appalachia, where more than a quarter of households live below the federal poverty line [20], and residents have endured disparate burdens of premature death and disability rooted in structural socioeconomic inequities [21-25] and healthcare disparities for decades [20, 26, 27].

This study focuses on a cluster of five rural Appalachian counties where between 23% and 32% of residents live below the federal poverty level, defined as a household income less than $25,000 for a family of four. We are not listing the names of these counties to avoid compounding stigma. In a recent study, 59 % of PWUD residing in these counties tested positive for HCV[28]. Downsizing of coal mining [29, 30], workforce de-unionization, and outmigration [31, 32] are among the forces deepening impoverishment and stagnating economic mobility in this area [25, 33]. Beginning in the 1990s, targeted prescription pain pill marketing tactics and loosely regulated prescribing practices [34,35] flooded Kentucky’s socioeconomically distressed communities with an abundance of potent POs [36-38]. These communities were already strained by high prevalence of chronic pain from work-related injuries and unmet mental health needs [30, 36]. The influx of POs, such as oxycodone has contributed to reported increased initiation of injecting and fatal overdoses [39] among young adults [16]. Subsequently, policies aimed at curbing supply of POs have expanded market demands for heroin as a cheaper alternative [40]. Between 2004 to 2014, Kentucky was 1 of 2 US states where treatment admissions attributed to heroin injection increased by more than 1000 % [18].

A recent study found most of the 220 US counties identified as highly susceptible to localized HCV and HIV outbreaks were rural, with nearly a quarter of these counties located in Kentucky [41]. Yet, beyond research on social and risk networks [16, 42-45], surprisingly few studies have examined social-ecological determinants of drug use and HCV in eastern Kentucky, or in any rural area [46]. Prior studies of Appalachian Kentucky show relationships between PO use, injecting practices, and features of social networks [16,17,47,48]. These studies suggest that oxycodone (OxyContin) operates as currency for social capital in PWID networks [47]; linkages exist among loggers and miners’ chronic pain, health service barriers, and PO use [37, 38]; and that gender, kinship, and intimate partnership dynamics are correlated with PO use and HCV risk for women [48,49]. Studies also suggest that people lack adequate access to MAT. A recent survey found that 23% of people who used opioids to get high in the study area tried to get into MAT in the past 6 months but were unsuccessful[28]. The present qualitative, exploratory study builds on this important work. Using REF as a “sensitizing framework,”[50] we advance understanding of rural US risk environments by describing features of the local risk environment, and exploring how they may interact to influence opioid use and HCV vulnerability, from the lived experiences and perspectives of young adults who use opioids and live in rural Appalachian Kentucky.

Methods

Participants were recruited between March and August 2017 via community-based outreach methods (e.g., cookouts, flyers) and peer referral. We admininstered brief screenings to identify eligible participants. Eligibility criteria included being aged 18-35 years, using PO or heroin to get high in the past 30 days, and living in one of thefive target counties. Participants who reported injecting or using opioids by other routes of administration were eligible. Eligible individuals took part in an indepth, one-on-one interview. The interview guide was constructed using REF, and explored each domain of the rural risk environment--economic, physical, social, political, and healthcare/law enforcement interventions -- as well as risk behaviors for HCV [5, 6, 9, 51]. Each participant took part in a brief survey after the one-on-one qualitaive interview that queried drug use patterns and sociodemographic characteristics. Interviews were conducted by trained interviewers in places that were private, convenient to participants, and safe; interview locations included cars, libraries, and local health departments. Interviews were audiorecorded and lasted 60-90 minutes; participants received $30 for taking part in the interview. All audiorecordings were transcribed verbatim.

The study adopted a constructivist grounded-theory approach [50, 52, 53]. The codebook was created based on prior literature and a system of open-coding. Consistent with Charmaz and others, we used REF as a set of inter-related sensitizing concepts in this analysis. “Sensitizing concepts offer ways of seeing, organizing, and understanding experience; they are embedded in our disciplinary emphases and perspectival proclivities.” [54]

REF is a framework, and not a theory, and thus provided a generative starting point for data collection and analyses to explore which features of participants’ environments shaped HCV risk, and how they did so. As with all sensitizing concepts used in Grounded Theory, data collection and analyses allowed for departures and negations of REF [54]. Transcripts were double-coded and reviewed for consistency; coding discrepancies were resolved through discussion. We used an interactive process of conceptual ordering, axial coding, diagramming, selective coding, and memoes to identify and describe emergent properties and intersecting features of categories, and explore how REF constructs promoted drug use, and safe versus harmful injection-related behaviors. We explored possible gender differences in risk environments, and in the processes through which they affected HCV risk beahviors. We used NVivo version 12 to support analyses. [55]

In this exploratory study, we recruited participants who reported injecting and using drugs through non-injection routes - the latter were included because they reported using drugs with PWID and demonstrated firsthand knowledge of the places where people inject and social contexts surrounding risky injection behaviors. Moreover, the interview guide encouraged participants to describe risk environments for other young adults in the area. Data collection ceased when we reached saturation on our guiding questions about the risk environment and drug-related harm

Ethics Statement

All data collection protocols for this study were approved by Institutional Review Boards at Emory University. Audiofiles and transcripts were stored on a HIPAA-compliant server; paper documents were stored in a locked cabinet accessible only to project staff.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participants included 19 non-Hispanic white adults, 58% of whom were men (n=11; Table 1). The mean age was 26 years (SD=4.20), and participants reported living in the five county area for an average of 11 years (range= 0.5-27 years). Akin to the study area (which was 95% non-Hispanic White), 100% of the sample was non-Hispanic White. Participants reported using multiple drugs to get high within the past 30 days, and 90% and 47% of participants reported recent use of POs to get high and heroin, respectively. Most participants (74%, n=14) reported injecting at least one type of drug in past 6 months, and heroin, POs, and methamphetamines were the most commonly injected drugs. Participants reported knowing an average of 41 other young adults who consumed opioids and lived in the area.

Table 1:

Characteristics of young adults who live in rural Kentucky and reported recently using opioids to get high (N=19)

| Characteristics | Mean/N | SD/% |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26.30 | 4.20 |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 11 | 57.90 |

| Women | 8 | 42.10 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 19 | 100.00 |

| Drugs used (multiple responses permitted; most commonly reported answers presented here) | ||

| Heroin | 9 | 47.37 |

| Prescription opioids | 17 | 89.50 |

| Methamphetamines | 11 | 57.90 |

| Injected drugs (past 6 months) | 14 | 76.10 |

| Drugs Injected (multiple responses permitted; most commonly reported answers presented here) | ||

| Heroin | 8 | 42.10 |

| Prescription opioids | 9 | 47.37 |

| Methamphetamines | 7 | 36.84 |

Qualitative findings

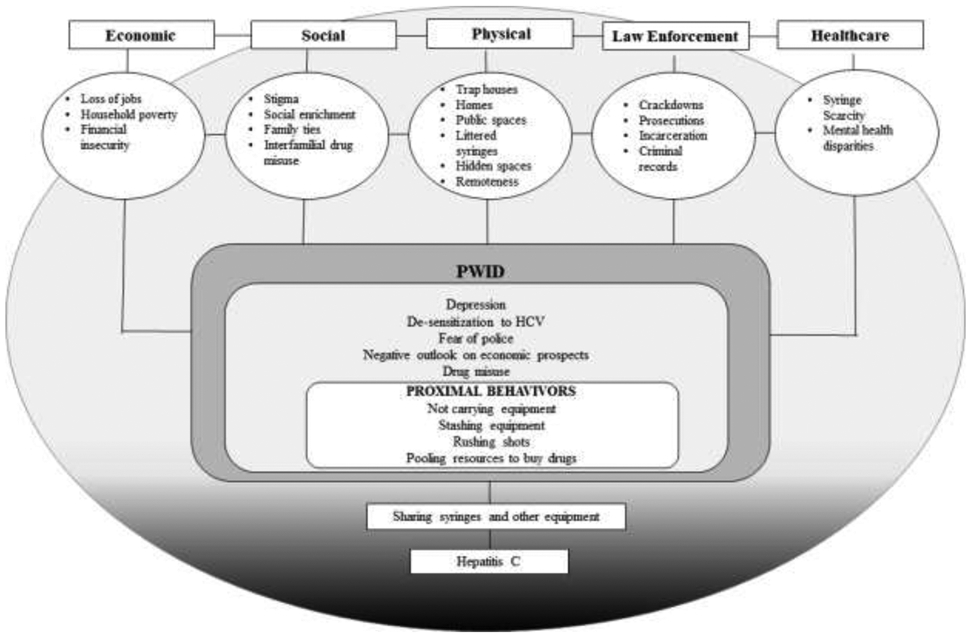

A range of features of social, economic, political, law enforcement, healthcare, and physical domains, operating at multiple, intersecting levels, emerged as prominent factors shaping young adults’ drug use and vulnerabilities to HCV in the study area. We first discuss features of rural risk environments that appeared to propagate propensities for drug use, and then turn to describing how these features shaped HCV vulnerability, from participants’ perspectives. Figure 1 provides a visual portrayal of our findings. We explored gender differences in HCV risk behaviors and in experiences with the REF, but found none in this sample, and so present findings for women and men together.

Figure 1.

Rural Risk Environment for Hepatitis C Among Young Adults in Appalachian Kentucky

Economic adversity, lack of social enrichment, and stigma: Drivers of Substance Use

A barren job market, diminished formal opportunities for social enrichment, and stigma were macro-level features of the social and economic environment that shaped drug use among young adults. Four of the five counties in the study area were more rural and less populated than a county [“County Z”] with a small city that contained a large hospital and a state university anchoring its downtown. Participants who currently lived in or had recently relocated from more rural counties within the study area reported worse employment situations than residents of this more populated county. As one woman who recently moved from a more to less rural county to work at a fast food restaurant said: “Yeah.. there ain’t no jobs there like there is here [County Z].” Longer-term residents of “County Z,” however, still reported significant challenges with employment. A young man who recently competed high school remarked:

“It is hard to get a job after graduating. I still can’t get a job. I have applied to every fast food [restaurant].. when I was in high school, I applied everywhere. Then I was like ok… once I graduate, then they will call me, but they still haven’t. I have applied like three times everywhere in this town.”

The costs of criminal justice involvement compounded participants’ economic distress. A history of arrest or incarceration made it extremely difficult to get work. As a 27-year old woman explained:

“Nobody will hire me because of my record, and [my boyfriend] is doing everything [paying bills] himself.”

While features of the physical environment provided young adults with places for socialization, reflection, and recreation, economic distress limited social opportunities. Lakes, mountains, and trails were identified as places where young adults engaged in outdoor activities such as such as fishing, swimming, camping, and four-wheeling. As a 33-year old woman described it:

“That’s what I love to do: go out four-wheeling. It gets your mind off of stuff. That’s what I did to get rid of some of my drug habits-- I went out four-wheeling. Got muddy.”

Yet, the effects of community-level economic decline has also extended to decaying resources for youth and young adults in the area. Participants expressed nostalgia for places, events, and activities that once provided sources of social enrichment for families and communities during childhood. A 29 year old woman stated: “There is literally nothing here. It wasn’t like that when I was younger… there was [sic] pool halls and stuff that got shut down.”

A 27-year old woman also longed for more structured activities for youth in the area.

“They used to have a bowling alley. They shut that down. They took the city pool out. There’s nothing. There’s no events to take the kids to – no concerts – You sit at home, or ….maybe get to go to McDonald’s or something.”

Analysis suggests that diminished sources of social enrichment, paired with poor prospects for financial security, contributed to feelings of disempowerment and depression among local young adults.

A 25-year old man said:

“There is a lack of jobs – that tends to send people into a depressive state; because they are trying, but it ain’t getting them nowhere; and it tends to be easier to backpedal than it is to try to go forward.”

Participants reported that they and others used opioids to cope with economic adversity and depression. For instance, a 26-year old man reflected on the negative consequences of a bleak job market: “If jobs could be found around here. It wouldn’t be that bad. We wouldn’t have the depression that people are trying to fix with the drugs.” An 18-year old man said: “Drugs is their [young adults] life…because there’s not activities to do. That is a big thing around here. People do drugs, because there is nothing else to do.” A 26-year old man viewed the absence of jobs as a root cause drug use: “If we could get more jobs here, half the needle problem would go away.”

People who reported severe feelings of depression associated those feelings with “not caring” or “feeling powerless” against acquiring HCV, which in turn led to taking less precautions against not sharing injection equipment even when knowing the risk. As one woman noted, “People just basically feel down. Feel depressed, and so they don’t really focus on injecting safely.”

Poor access to care and drug-related stigma were cited as barriers to accessing services that might alleviate depression and addiction. Participants reported that there were few mental health services in their communities that young adults could use to treat depression. As described by a young man raising a family, who sustained debilitating combat injuries in the military:

“This town, a lot of people are very depressed, and nothing gets done about it. Whether you are a veteran, or someone whose experienced domestic violence, anything… There’s nothing to help around here.”

Even when services were available, stigma often prevented participants from accessing them. Participants lamented that many community members held strong, dehumanizing views against people who use drugs, and especially against those who injected; this stigma, in turn, undermined self-esteem and deterred people from seeking support. As a result PWID mostly count on family and each other for support. As a 25-year old woman remarked:

“Everybody’s judgmental, and it just keeps you from reaching out. The only other person you’re going to reach out to is the guy that can get you a needle or the drugs you’re trying to score.”

Countervailing family ties and interfamilial drug use

Economic hardships at the structural level cultivated complex, familial contexts that had countervailing features that both alleviated and exacerbated drug-related harms. Most participants reported having deep roots in Eastern Kentucky that spanned multiple generations, and cited strong familial ties as a buffer against economic adversities. Indeed, family ties were cited as the primary reason that young adults stay in the area, despite its poor economic prospects. A 27-year old-woman struggling to find employment said: “I just got family and stuff here. That is the only reason I am here.”

Families were central to many participants’ lives, and were sources of both support and harm. Reliance on parents, siblings, or cousins for housing, financial support, or childcare was common. One young mother remarked: “I got a little boy…He is six. He stays with my momma right now, until his momma gets back on her feet…He’s my world.” Another woman explained: “So, my sister just recently moved in, so she could pay the utilities, so that we could concentrate on getting the house payment caught up.”

However, interfamilial drug use was commonly reported, and described as counteracting the protective aspects of strong family ties by reinforcing generational patterns of poverty and addiction. An 18 year-old man who reported injecting heroin with his father and brother reflected on the influence of parental drug use and dealing on his extended family:

“ All three of our dads were drug dealers. So, we’d seen junkies and stuff. [My cousins and I] never wanted to be that. My dad… my life is like his… and my whole life he tried to get me to go on a different path. Somehow I got brought into it.”

In sum, results suggest that economic adversity, diminished social enrichment opportunities, and stigma contributed to depression among young adults. With few mental health and drug treatment options in the community, drug use became a common coping mechanism. According to these young adults, while strong family ties mitigated harms of impoverishment and stigma, interfamilial drug use also underlay cycles of addiction and impoverishment among young adults living in rural Kentucky.

REF And HCV RISK

The following section reports first on injection practices among young adults in rural Kentucky that create vulnerability to HCV transmission, and then describes key social-ecological determinants of this vulnerability, as described by participants.

Reported injecting behaviors

Participants described HCV as ubiquitous in their families and social circles. As a 29 year-old man put it:

“Hepatitis is an epidemic right now. Out of all my friends, there’s probably a handful that ain’t got it. All three of my cousins have it. My uncle has it. My mom’s probably got it. I’ve got it.”

Participants reported multiple injection behaviors that created HCV transmission risk. Sharing needles was the most commonly cited HCV risk behavior. Participants also routinely shared other injection equipment. Proximal reasons for sharing syringes and other injection equipment were not carrying personal equipment and resorting to using discarded syringes, rushing to inject in public spaces, stashing syringes in places where others may find them, and pooling resources to buy drugs. In the case of sharing other injection equipment, participants often noted that local PWID were unaware that HCV could be transmitted via sharing contaminated cookers, water, or cotton. One woman indicated that sharing cookers and cottons was common: “[PWID] share spoons. They share cottons. Well, usually the filter of a cigarette is what most people around here use.” Another woman learned about cottons as a transmission route during an interview, disclosing in a whispered aside: “I share cotton. I didn’t know that you could pass with cotton.” People who were rushing injections described being in situations where they do not have the time to sort equipment or prepare new water and therefore were more likely to share syringes and other equipment. Additionally, participants stated that people who pool money to buy drugs were more likely to share those drugs and any equipment used to inject them, especially within trap houses or settings where fear of police leads to rushing shots. Each of these behaviors was shaped by features of the risk environment, including the political environment governing syringe access; police; and poverty.

Local political opposition underlies barriers to sterile syringes

A systemic shortage of sterile syringes was the most commonly cited reason for syringe sharing, and this scarcity was attributed to local opposition, cost, stigma, and fear of law enforcement. One year prior to the time of data collection, Kentucky passed a law permitting syringe service programs (SSP), and one of the five counties had recently opened an SSP when this study started. Pharmacists were allowed to sell syringes over the counter without a prescription at their discretion, but few participants reported using this source. A woman living in a county without a syringe service program (SSP) reported: “You know, [community members] argue against [the SSP] and say its proliferating drug use, but… it’s an epidemic. You can’t stop it… [PWID] are gonna keep using dirty needles, unless you give us clean needles.”

In this context of syringe scarcity, participants reported obtaining syringes from a variety of sources, none of them guaranteed to be sterile. Sources included diabetic friends and family members; dealers, for about $5 per syringe; and on the roadside or other places where people discarded used syringes. A woman who reported injecting heroin and cocaine relied on her mother for clean syringes: “My mother is a diabetic. And she gets insulin needles, and she shoots up too.” One man spoke of instances where people resorted to injecting with littered syringes: “I have been with someone that literally picked one [syringe] up off the side of the road and used it. That’s so gross. I was like… you are going to catch something for sure.

Participants also traveled hundreds of miles to reach SSPs: a 27-year old woman remarked, “There is no needle exchange in the county. So, most of the time what people are doing to keep themselves safe is traveling outside the county, several hours, to get hypodermic needles.”

To compensate for syringe shortages, participants bleached syringes when they re-used their own syringes, or before sharing with another person. One man noted: “If you use after somebody, at least bleach it out. Or you’re just asking for it.” Another woman wished for Vancouver’s safe injection facility, but said she would settle for better access to free syringes: “That’s the main thing. More than anything. Just get us access to needles. If we have a way of getting clean needles for free, we will use them.

Most participants viewed the one SSP in the study area as a vital resource, but few reported utilizing this new program at the time of these interviews. Participants also indicated that fear of arrest and the SSP’s proximity to the police station deterred utilization of SSP services. As a 25-year old man stated:

“There’s a city police station on Main Street, and a sheriff’s office a thousand feet from the one [SSP] on Main Street, and then you’ve got your state police barracks up, like, smack in the middle of town. It could be a setup. They could go in, exchange their needle. You feel like they’re going to test it, find residue, call the cops; and they get arrested walking out. A lot of people fear that.”

Stigma further discouraged SSP participants. A 25-year old woman said: “people still scared to come to that program [SSP], because they don’t believe it is actually confidential.”

Fear of arrest and risky injection locations

Fear of law enforcement not only shaped whether people used the SSP, it was uniformly emphasized as a determinant of the physical places and social contexts where people injected. Most participants preferred injecting in the privacy of their own home, or that of family or friends. They viewed homes as places where they were less likely to share injection equipment or rush shots, because there was access to clean water, personal syringes and cookers, sanitized counter space to prepare shots, and less fear of police encounters. When queried about where he preferred to inject, a 25 year-old man answered: “Home. First and foremost. That’s where [people] feel the most comfortable. Just because they have all of their supplies… and everything set up”.

However, fear of law enforcement often led participants to inject away from homes, in settings that conferred significant HCV risk. According to participants, police, prosecutors, and courts were cracking down on heroin and drug-related crimes in the area. As a 25-year old man explained: “Everybody’s afraid of incarceration, because that’s a big charge [heroin possession]. They’re cracking down on it.”

To avoid the police, participants reported turning to “trap houses.” Trap houses are apartments, trailers, or motel rooms where people gathered to buy and/or inject drugs; they were reportedly abundant in the area. While trap houses solved the problem of how to travel from the location where the participant bought drugs to the location where they used them, they also introduced significant HCV-related harms. Trap houses were filled with people who were using drugs -- as 27-year old woman put it succinctly, in trap houses: “There’s people in and out all of the time” – and these peopled places provided multiple opportunities for HCV transmission. Trap houses were frequent sites of communal drug use between friends, casual acquaintances, and strangers, especially when people pooled resources to buy drugs inside the trap house. In addition, used syringes were strewn around the interior of trap houses, and around the exteriors. One woman spoke about the perils of injecting in trap houses with people she did not know or trust.

I don’t think it’s really the place but, it’s just the people wherever they might be using with you know, people are bound to want to pick up someone else’s thing and use it and put it back, you know to where they don’t know if they touched it

People were often experiencing dope sickness when arriving at trap houses, and those without money to buy syringes from dealers resorted to using these discarded syringes. As a 24 year old man described it: “As soon as they come in to buy it, they are not even leaving before they do it. There’s needles laying all over the place. If you get somebody that is really sick, they will just pick it up and use it.” Participants said that women who go to trap houses to exchange sex for drugs were often pressured into sharing needles: “Most of the time it’s women, they go there [trap house] to prostitute their selves out, and so when you’re prostituting yourself out… you know, you’re gonna use someone else’s needle”

In addition to turning to trap houses to avoid the police, participants avoided the police by rushing injections in less private places. As a 26-year old man stated:

“The only thing with [cops], is they make me more paranoid, so therefore I’d be trying to speed up the process of getting high [injecting].”

Some participants reported opting not to carry personal injection equipment when traveling between destinations because they feared police, which increased their odds of being in situation where people resolve to sharing equipment. When asked about people in his social circle, an 18-year old PWID, remarked: “No one that I know will carry one [syringe] out of the house.” Similarly, a 25-year old woman who reported injecting POs noted: “People don’t want to carry their needles on them if they think they are going to go to jail for it.” However, another man stated that he always carried an extra syringe in the event that a peer did not have a clean one to avoid sharing. “I always try to carry extra [syringe] with me. That way, if whoever I was with didn’t have one, I will give them a clean one.” One participant described how personal encounters with police dissuaded him from carrying syringes due to fear of charges related to accidental needle sticks.

“And the cop, the first thing they ask is there anything that will stick me or poke me? If you say no, and hope they don’t find it, then you’re going to get like wanton endangerment and do a long time [in prison], you know. Nobody is going to say ‘I’ve got a needle in my back pocket..’ because then you’re getting paraphernalia or whatever, and still wanton endangerment. They still might charge you with it.

Discussion

This exploratory study used REF as a sensitizing set of inter-related concepts to assess determinants of HCV vulnerability among young adults who used opioids to get high in rural Appalachian Kentucky. While preliminary, analysis provide insights into directions for future research and intersectoral interventions in rural settings. Using drugs to get high among young adults was described as closely tied to features of the social and economic environments. At the macro-level, job scarcity and lack of resources for social enrichment for youth contributed to high levels of depression among young adults. People reported that many young adults used opioids and other drugs to get high to cope with depression, in part because they lack access to mental health care and because stigma against people who use drugs deterred them from using available services. These findings signal a need for government and private sector interventions that increase resources for youth and young adult development, provide households financial security, and stimulate economic mobility of young adults in rural Appalachia.

This study’s findings mirror those of recent studies focused on the implications of economic domains on drug-related harms in urban settings [10]. For example, McClean (2016) suggest that de-industrialization and population loss in wake of a dwindling steel industry underlies heroin use and overdose mortality in the Monongahela Valley region of Pennsylvania [56]. Similarly, in our study setting, drug use and HCV were rooted in economic distress from a stagant job market for young adutls, against the backdrop of a shrinking coal mining industry.

We found that, in this novel rural environment, multiple concepts within REF “[offered] ways of seeing, organizing, and understanding experience” related to place and HCV vulnerability. REF is an impactful framework for developing interventions to slow the tides of drug-related harms in contexts characterized by significant economic decline [57]. Future studies should continue to explore how historical, sociopolitical, and economic forces at the state and regional level shape trajectories of drug use and its related harms in Appalachia. Additional empirical evidence may prove essential for advancing the political viability of legislative measures that incorporate anti-poverty strategies and remove barriers to unemployment for people with criminal records. These new studies can draw on the methods developed to study REF in urban areas, including geospatial methods to measure physical, social, economic, political, and healthcare service/criminal justice characteristics of places and multilevel models to investigate how these place characteristics might relate to a range of risk and protective behaviors [11, 58, 59].

In 2014, Kentucky expanded Medicaid benefits via the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to wider range of young adults, which has provided thousands of previously uninsured residents coverage for behavioral health services[60] and HCV treatment for the first time[60]. Medicaid is also a vital financing stream for supporting the operation of rural hospitals, drug treatment services, and essential healthcare services. However, a pending proposal portends to take away Medicaid coverage from young adults. Thus, research is needed to examine the impacts of Medicaid policy on individuals’ access to drug treatment and HCV treatments, and evaluate the implications of restricting Medicaid benefits on the capacities of rural health systems as treatment providers and employers[61, 62]

Participants described HCV as pervasive in their families and social networks, and reported a range of injection behaviors that associated with HCV transmission risk. Despite knowledge of risks, sharing needles was the most commonly cited HCV risk behavior. Participants also reported widespread sharing of other injection equipment, and some were unaware that HCV could be transmitted via sharing cookers, water, and cotton. Proximal reasons for sharing equipment included not carrying personal equipment and resorting to using littered syringes, rushing shots, stashing syringes in places where others may find them, and pooling money to share drugs.

Insufficient access to free, sterile syringes was the most prominently cited factor that resulted in risky injection practices. Syringe scarcity prompted many people to depend on an array of sources for accessing injection equipment that may be contaminated. Syringe scarcity, stigma, and fear of police led to multiple proximal risk behaviors, such as not carrying personal equipment and rushing injections that often increase risk of acquiring an HCV infection through sharing equipment. Since Kentucky legalized the operation of SSPs in 2015, local health departments have started 50 programs across the state [63]. The statutory framework authorizing SSPs, however, provides local officials wide discretion to establish policies and components of each program. Thus, one pressing area for future research is to examine the influence of localized policy environments on the implementation and impact of rural SSPs.

Participants reported having large social circles and strong family ties. Both were cited as a vital sources of support, and a basis for living in rural towns despite dire economic prospects. Yet, social buffers were sometimes counteracted by interfamilial drug use, which contributed to financial insecurity, addiction, and unsafe injecting practices. Adoption of secondary-exchange policies in SSPs is one way to leverage dense social connections to overcome geographic, financial, and psychological barriers to accessing sterile equipment[64, 65].

Notably, PWID reported relying on each other for social, material, and emotional support due to community stigma. Community organizing of directly-impacted people and coalition building for key stakeholders offer promising strategies for advancing policy reforms and evidence-based programs amidst enduring socioeconomic inequities[66, 67].

An immense body of research has demonstrated that criminalization, police crackdowns, and other deterrence-based approaches to drug use typically exacerbate rather than mitigate vulnerabilities to blood-borne infections among PWID [12, 68]. This study bolsters this widely replicated finding. Fear of law enforcement was uniformly cited as a determinant of the physical places and social contexts where young adults injected. Avoidance of arrest was a primary reason for proximal risk behaviors, such as not carrying personal injection equipment and injecting in trap houses that may result in sharing equipment. Moreover, the proximity of SSPs to police stations deterred utilization of program services. Prior studies suggest that training and education on the benefits of SSPs for officer safety and linkages to drug treatment improves police perceptions and buy-in for SSP. Implementing police trainings will likely improve reach and impact of SSPs in Kentucky [69, 70]. Recent data show that the greatest levels of growth in jail populations is taking place in rural communities, and largely driven by incarceration for drug-related crimes[71]. Examining the public health implications of jail expansion on drug-related harms in rural settings is another important direction for action-oriented researchers.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. In retrospect, data collection and analysis might have been strengthened had we included sensitizing concepts pertaining to young adult development. This conceptual expansion could have supported explorations of how various features of the risk environment supported or thwarted the attainment of developmental milestones for young adults, and the pathways through which these experiences in turn might shape HCV vulnerability and resilience. In addition, the five-county area was quite heterogeneous, with significant variations in topographies (e.g., mountainous vs flat with rolling hills) and in the extent of rurality (forests vs. more settled areas). Our guide did not explore these variations, and participants did not discuss them independently, and yet these conditions may shape key experiences (e.g., isolation, access to resources) with implications for HCV risk

Future directions and conclusion

This is one of the first studies of the rural risk environment, a vital arena for inquiry given the geographic shifts in the epidemiology of opioid use and drug-related harms. Answering questions at the intersections of race, class, and geography—that account for structural racism of the drug war—are important for advancing of equitable policy solutions to drug-related harms that target social and economic determinants. The War on Drugs fueled a vast expansion of criminal justice system in the U.S. that is inextricably bound to historical and contemporary structures of racial oppression and discrimination against black men and women[72]. Prior drug epidemics, such as the crack boom in the 1980s and 1990s resulted in hyper-policing and mass incarceration of black communities[8, 11, 51]. Future research should dive deeper into relationships between policing, incarceration trends, and HCV burden in rural settings. Future research could also explore HCV vulnerability and the REF in older participants, and among the emerging population of people who use methamphetamines to get high. Researchers seeking to build on this study might consider adopting quasi-experimental designs to explore pathways linking upstream determinants, community contexts, individual behaviors, and HCV outcomes. Multi-level modeling and geospatial techniques previously applied to urban and metropolitan risk environments should be extended to rural contexts [73]. Finally, examining the impacts of state laws and regulations on economic distress and capacities of rural communities to adopt and expand SSPs in geographically and socio-politically distinct contexts of rural Appalachia is vital for advancing structural change that is needed.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21 DA042727; PIs: Cooper and Young). Community partners who provided feedback during the development of the quiz were identified through an ongoing study supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, CDC, SAMHSA, and the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) (UG3 DA044798; PIs: Young and Cooper); the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, CDC, SAMHSA, or ARC. We declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Havens JR, et al. , Individual and network factors associated with non-fatal overdose among rural Appalachian drug users. Drug and alcohol dependence, 2011. 115(1-2): p. 107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koneru A, Increased hepatitis C virus (HCV) detection in women of childbearing age and potential risk for vertical transmission—United States and Kentucky, 2011–2014. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 2016. 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christian WJ, et al. , Viral hepatitis and injection drug use in Appalachian Kentucky: a survey of rural health department clients. Public health reports, 2010. 125(1): p. 121–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zibbell JE, et al. , Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged≤ 30 years-Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006-2012. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 2015. 64(17): p. 453–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes T, The risk environment’: a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. . International journal of drug policy, 2002. 13(2): p. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhodes T, Risk environments and drug harms: a social science for harm reduction approach. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper HL, Bossak B, Tempalski B, Des Jarlais DC, & Friedman SR, Geographic approaches to quantifying the risk environment: Drug-related law enforcement and access to syringe exchange programmes. . International Journal of Drug Policy, 2009. 20(3): p. 217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper HL, Des Jarlais DC, Tempalski B, Bossak BH, Ross Z, & Friedman SR , Drug-related arrest rates and spatial access to syringe exchange programs in New York City health districts: combined effects on the risk of injection-related infections among injectors. Health & place, 2012. 18(2): p. 218–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper HL, & Tempalski B, Integrating place into research on drug use, drug users’ health, and drug policy. . International Journal of Drug Policy,, 2014. 25(3): p. 503–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Des Jarlais DC, Pinkerton S, Hagan H, Guardino V, Feelemyer J, Cooper H, … & Uuskula A, 30 years on selected issues in the prevention of HIV among persons who inject drugs. Advances in preventive medicine,, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper HL, et al. , Racialized risk environments in a large sample of people who inject drugs in the United States. International Journal of Drug Policy, 2016. 27: p. 43–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman SR, Tempalski B, Brady JE, West BS, Pouget ER, Williams LD, … & Cooper HL, Income inequality, drug-related arrests, and the health of people who inject drugs: reflections on seventeen years of research. International Journal of Drug Policy, 2016. 32(11-16). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strathdee SA, Hallett TB, Bobrova N, Rhodes T, Booth R, Abdool R, & Hankins CA, HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: the past, present, and future. The Lancet, 2010. 376(9737): p. 268–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linton SL, Cooper HL, Kelley ME, Karnes CC, Ross Z, Wolfe ME, … & Tempalski B ., Associations of place characteristics with HIV and HCV risk behaviors among racial/ethnic groups of people who inject drugs in the United States. Annals of epidemiology, 2016. 26(9): p. 619–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knight KR, et al. , Single room occupancy (SRO) hotels as mental health risk environments among impoverished women: The intersection of policy, drug use, trauma, and urban space. International Journal of Drug Policy, 2014. 25(3): p. 556–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young AM and Havens JR, Transition from first illicit drug use to first injection drug use among rural Appalachian drug users: a cross-sectional comparison and retrospective survival analysis. Addiction, 2012. 107(3): p. 587–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young AM, Havens JR, and Leukefeld CG, Route of administration for illicit prescription opioids: a comparison of rural and urban drug users. Harm reduction journal, 2010. 7(1): p. 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zibbell JE, et al. , Increases in acute hepatitis C virus infection related to a growing opioid epidemic and associated injection drug use, United States, 2004 to 2014. American journal of public health, 2018. 108(2): p. 175–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cicero TJ, et al. , The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA psychiatry, 2014. 71(7): p. 821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Commission AR, Health Disparities in Appalachia Appalachian Regional Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Billings D and Blee K, Social origins of Appalachian poverty: Markets, cultural strategies, and the state in an Appalachian Kentucky community, 1804–1940. Rethinking Marxism, 200416(1): p. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenberg P, Spatial inequality and uneven development: The local stratification of poverty in Appalachia. Journal of Appalachian Studies, 2016. 22(2): p. 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kannapel PJ and Flory MA, Postsecondary Transitions for Youth in Appalachia's Central Subregions: A Review of Education Research, 1995-2015. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 2017. 32(6): p. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith BE, Another place is possible? Labor geography, spatial dispossession, and gendered resistance in Central Appalachia. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 2015. 105(3): p. 567–582. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsou P-C, “YOU’RE SURVIVING BUT I DON’T SEE HOW YOU’RE LIVING” APPALACHIAN WOMEN TALK ABOUT TANF AND EMPLOYMENT IN THEIR COMMUNITIES. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lane NM, et al. , Health care costs and access disparities in Appalachia. 2012: Citeseer. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris JK, et al. , The double disparity facing rural local health departments. Annual review of public health, 2016. 37: p. 167–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hannah LF Cooper DC, Nadya Prood, Umed Ibragimov, April Ballard, Regine Haardörfer, April M Young. , Potential for HIV Outbreaks in Rural Kentucky, in 2018 National CFAR Scientific Symposium 2018: Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott SL, et al. , The long-term effects of a coal waste disaster on social trust in Appalachian Kentucky. Organization & Environment, 2012. 25(4): p. 402–418. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hendryx M, Mortality from heart, respiratory, and kidney disease in coal mining areas of Appalachia. International archives of occupational and environmental health, 2009. 82(2): p. 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tighe JR, Responding to the foreclosure crisis in Appalachia: A policy review and survey of housing counselors. Housing Policy Debate, 2013. 23(1): p. 111–143. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulrich-Schad JD, Henly M, and Safford TG, The role of community assessments, place, and the great recession in the migration intentions of rural Americans. Rural Sociology, 2013. 78(3): p. 371–398. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kratzer NW, Coal mining and population loss in Appalachia. Journal of Appalachian Studies, 2015. 21(2): p. 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luu H, et al. , Trends and Patterns of Opioid Analgesic Prescribing: Regional and Rural-Urban Variations in Kentucky From 2012 to 2015. The Journal of Rural Health, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dyer O, Kentucky seeks $1 bn from Purdue Pharma for misrepresenting addictive potential of oxycodone. 2014, British Medical Journal Publishing Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moody LN, Satterwhite E, and Bickel WK, Substance use in rural Central Appalachia: Current status and treatment considerations. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 2017. 41(2): p. 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leukefeld C, et al. , Prescription drug use, health services utilization, and health problems in rural Appalachian Kentucky. Journal of Drug Issues, 2005. 35(3): p. 631–643. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leukefeld C, et al. , What does the community say: Key informant perceptions of rural prescription drug use. Journal of Drug Issues, 2007. 37(3): p. 503–524. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bunn T and Slavova S, Drug Overdose Morbidity and Mortality in Kentucky, 2000-2010: An Examination of Statewide Data, Including the Rising Impact of Prescription Drug Overdose on Fatality Rates, and the Parallel Rise in Associated Medical Costs. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Victor GA, et al. , Opioid analgesics and heroin: Examining drug misuse trends among a sample of drug treatment clients in Kentucky. International Journal of Drug Policy, 2017. 46: p. 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van MH, et al. , County-level vulnerability assessment for rapid dissemination of HIV or HCV infections among persons who inject drugs, United States. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 2016. 73(3): p. 323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudolph AE, Young AM, and Havens JR, Examining the Social Context of Injection Drug Use: Social Proximity to Persons Who Inject Drugs Versus Geographic Proximity to Persons Who Inject Drugs. American journal of epidemiology, 2017. 186(8): p. 970–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young A, Jonas A, and Havens J, Social networks and HCV viraemia in anti-HCV-positive rural drug users. Epidemiology & Infection, 2013. 141(2): p. 402–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young A, et al. , Network structure and the risk for HIV transmission among rural drug users. AIDS and Behavior, 2013. 17(7): p. 2341–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young AM, Rudolph AE, and Havens JR, Network-based research on rural opioid use: an overview of methods and lessons learned. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 2018: p. 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Broz D, et al. , Multiple injections per injection episode: High-risk injection practice among people who injected pills during the 2015 HIV outbreak in Indiana. International Journal of Drug Policy, 2018. 52: p. 97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jonas AB, et al. , OxyContin® as currency: OxyContin® use and increased social capital among rural Appalachian drug users. Social science & medicine, 2012. 74(10): p. 1602–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buer LM, Leukefeld CG, and Havens JR, “I'm Stuck”: Women's Navigations of Social Networks and Prescription Drug Misuse in Central Appalachia. North American Dialogue, 2016. 19(2): p. 70–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Staton-Tindall M, et al. , Drug use, hepatitis C, and service availability: perspectives of incarcerated rural women. Social work in public health, 2015. 30(4): p. 385–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Charmaz K, Grounded theory: objectivist and constructivist methods In ‘Strategies for Qualitative Inquiry’.(Eds Denzin NK, Lincoln YS) pp. 249–291. 2003, Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cooper HL, Wypij D, & Krieger N, Police drug crackdowns and hospitalisation rates for illicit-injection-related infections in New York City. International Journal of Drug Policy, 2005. 16(3): p. 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strauss A and Corbin J, Basics of qualitative research. 1990: Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glaser BG and Strauss AL, Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. 2017: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Charmaz K and Belgrave L, Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. The SAGE handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft, 2012. 2: p. 347–365. [Google Scholar]

- 55.NVivo qualitative data analysis Software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 12, 2018.

- 56.McLean K, “There's nothing here”: Deindustrialization as risk environment for overdose. International Journal of Drug Policy, 2016. 29: p. 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friedman SR, Rossi D, and Braine N, Theorizing “Big Events” as a potential risk environment for drug use, drug-related harm and HIV epidemic outbreaks. International Journal of Drug Policy, 2009. 20(3): p. 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Linton SL, et al. , Changing places and partners: associations of neighborhood conditions with sexual network turnover among African American adults relocated from public housing. Archives of sexual behavior, 2017. 46(4): p. 925–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Linton SL, et al. , People and places: Relocating to neighborhoods with better economic and social conditions is associated with less risky drug/alcohol network characteristics among African American adults in Atlanta, GA. Drug and alcohol dependence, 2016. 160: p. 30–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wen H, et al. Impact of Medicaid expansion on Medicaid-covered utilization of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder treatment. Medical care, 2017. 55(4): p. 336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sommers BD, et al. , Changes in utilization and health among low-income adults after Medicaid expansion or expanded private insurance. JAMA internal medicine, 2016. 176(10): p. 1501–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wright CB and Vanderford NL, Closing Kynect and Restructuring Medicaid Threaten Kentucky's Health and Economy. Journal of health politics, policy and law, 2017. 42(4): p. 719–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Services K.C.f.H.a.F., Kentucky Syringe Exchange Programs. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brothers S, Merchants, Samaritans, and public health workers: secondary syringe exchanger discursive practices. International Journal of Drug Policy, 2016. 37: p. 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Snead J, et al. , Secondary syringe exchange among injection drug users. Journal of Urban Health, 2003. 80(2): p. 330–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bell SE, Photovoice as a strategy for community organizing in the central Appalachian coalfields. Journal of Appalachian Studies, 2008: p. 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bell SE “There Ain’t No Bond in Town Like There Used to Be”: The Destruction of Social Capital in the West Virginia Coalfields 1 in Sociological Forum. 2009. Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Friedman SR, Pouget ER, Chatterjee S, Cleland CM, Tempalski B, Brady JE, & Cooper HL, Drug Arrests and Injection Drug Deterrence. American Journal of Public Health, 2011101(2): p. 344–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beletsky L, et al. , Police training to align law enforcement and HIV prevention: preliminary evidence from the field. American Journal of Public Health, 2011. 101(11): p. 2012–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davis CS, et al. , Attitudes of North Carolina law enforcement officers toward syringe decriminalization. Drug and alcohol dependence, 2014. 144: p. 265–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kang-Brown J and Subramanian R, Out of sight: The growth of jails in rural America. 2017: Vera Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alexander M, The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. 2012: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Janulis P, The micro-social risk environment for injection drug use: An event specific analysis of dyadic, situational, and network predictors of injection risk behavior. International Journal of Drug Policy. 27: p. 56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]