Abstract

The disease burden associated with air pollution continues to grow. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates ≈7 million people worldwide die yearly from exposure to polluted air, half of which—3.3 million—are attributable to cardiovascular disease (CVD), greater than from major modifiable CVD risks including smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. This serious and growing health threat is attributed to increasing urbanization of the world's populations with consequent exposure to polluted air. Especially vulnerable are the elderly, patients with pre‐existing CVD, and children. The cumulative lifetime burden in children is particularly of concern because their rapidly developing cardiopulmonary systems are more susceptible to damage and they spend more time outdoors and therefore inhale more pollutants. World Health Organization estimates that 93% of the world's children aged <15 years—1.8 billion children—breathe air that puts their health and development at risk. Here, we present growing scientific evidence, including from our own group, that chronic exposure to air pollution early in life is directly linked to development of major CVD risks, including obesity, hypertension, and metabolic disorders. In this review, we surveyed the literature for current knowledge of how pollution exposure early in life adversely impacts cardiovascular phenotypes, and lay the foundation for early intervention and other strategies that can help prevent this damage. We also discuss the need for better guidelines and additional research to validate exposure metrics and interventions that will ultimately help healthcare providers reduce the growing burden of CVD from pollution.

Keywords: air pollutants, environmental; cardiovascular abnormalities; cardiovascular disease; epithelial barrier

Subject Categories: Atherosclerosis, Coronary Artery Disease, Thrombosis, Vascular Disease, Gene Expression & Regulation

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of death worldwide, and evidence suggests that the disease process can begin early in life.1 Several factors contribute to the development of CVD; greater than half of the risk is modifiable, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and smoking, while the remaining risks are thought to be heritable.2 A substantial body of epidemiological evidence has demonstrated significant associations between air pollution exposure and increased CVD risk.3 Here, we focus on the cumulative lifetime burden of air pollution, especially the evidence of pollution exposure that begins in childhood, by surveying the association between CVD risk from exposure to ambient and indoor pollution and discuss interventional strategies to prevent and mitigate risk.

Every year, >3 million people worldwide die of ischemic heart disease or stroke attributed to air pollution, more than from other modifiable cardiac disease risks such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, or cigarette smoking.4 Both acute and chronic exposures to components of air pollution, including fine particulate matter (PM) and polycyclic hydrocarbons (PAH), have been associated with increased cardiovascular events such as ischemic heart disease, heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension, and others.5

The cardiopulmonary systems of children are rapidly developing, and are therefore more vulnerable to injury and inflammation caused by pollutants.6 Emerging observations from the World Health Organization (WHO) suggest that early exposure to pollution during childhood and adolescent years can alter a child's health trajectory and result in increased prevalence of risks for CVD later in life, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, and hypertension.7 The most recent WHO report concluded that the millions of children exposed to unsafe levels of air pollution suffer a “life sentence” of illness, pushing them to a “path of chronicity, suffering…and challenge.”8 Furthermore, economically disadvantaged groups are disproportionally vulnerable to air pollution and its adverse health effects.9 As such, there is an urgent need to formulate more effective policy responses and health guidelines, aimed at protecting the most vulnerable, particularly children and the elderly.

Air pollution is a complex mixture containing both particles and gases. The air pollutants for which the Environmental Protection Agency has set National Ambient Air Quality Standards include carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and ozone, PM, and lead.5 The most well‐researched air pollutant related to cardiovascular events is fine PM (particles ≤2.5 μm in diameter [PM2.5]), of which a large fraction is comprised of particles generated by a combustion of fossil fuels, including black elemental carbon, metals, and a variety of complex organic molecules.10 These fine particles penetrate deeply into the small airways and alveoli of the lungs where they stimulate macrophages and epithelial cells to release proinflammatory cytokines.4, 11, 12 The US Environmental Protection Agency regulates air pollutants such as lead, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxides, carbon monoxide, PM, and ozone, all of which have been associated with cardiovascular events.5

Although the association between exposures to a pollutant like PM2.5 and CVD risk is now well established, the specific mechanisms by which these exposures promote CVD are not completely understood.3 From epidemiological studies, one hypothesis argues that upon entering the lungs, pollutants produce local inflammation and oxidative stress that leads to subsequent systemic inflammation, which contributes to endothelial dysfunction, thrombosis, and enhanced atherosclerosis.13 A second hypothesis suggests that pollutants activate the pulmonary autonomic nervous system which can lead to life‐threatening arrhythmias.5 A third hypothesis suggests that PM, particularly, ultrafine particles (<0.1 μm in diameter), enter the blood stream, directly damaging tissues and cells within the cardiovascular system.5

This paper is meant to be a contemporary review, rather than a comprehensive review. It focuses on relevant and recent published articles. Using available evidence, including from our own research, it intends to inform readers about the complex issue of the cumulative lifetime burden of CVD from exposure to air pollution. Search terms and keywords included hypertension, obesity, glucose metabolism, and diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, dyslipidemia, cardiac arrhythmias, stroke, atherosclerosis, cardiac disease, as well as pollution, PAH, PM2.5, concurrently with keywords including early exposure, fetal exposure, infants, children, or adolescent. We searched for exact phrases such as “pollution and CVD and children” and included wildcard searches to find other possible results such as “cardiovascular disease * pollution”. Finally, to make our online searches more comprehensive, we conducted citation searches to determine whether articles have been cited by other authors, and to find more recent papers on the same or similar subject(s). All citations were confirmed and entered using EndNote.

Global Air Pollution: A Growing Lifetime Burden

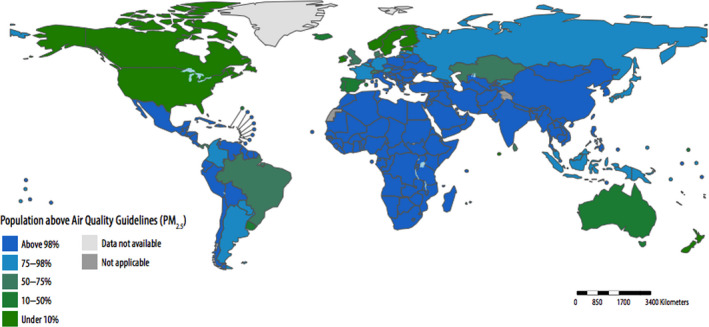

Much of the world's population lives in places where air quality exceeds the limits of the health‐protective guidelines set by the WHO (Figure 1), making air pollution the largest environmental risk to health worldwide.14 Here, we discuss the risks from ambient and indoor air pollution, as well as pollution from tobacco smoke, which shares common pathways to air pollution‐induced CVD.

Figure 1.

Proportion of children aged <5 years of age living in areas in which World Health Organization air quality guidelines (particulate matter <2.5 μm) are exceeded (by country, 2016).From World Health Organization report on air pollution.14 PM 2.5 indicates particulate matter <2.5 μm.

Ambient and Indoor Pollution

Although there are many sources of air pollution, both natural (eg, volcanic eruptions) and man‐made (eg, cookstoves, power plants, motor vehicles), the latter is the primary source, because even most catastrophic wildfires are started by human activities.14, 15 Outdoor air pollution is typically produced by combustion of fossil fuels and industrial processes while indoor or household air pollution is produced by smoke from poorly ventilated domestic cookstoves that burn solid fuels such as wood, crop waste, dried dung, and coal/lignite or kerosene mostly in low and middle‐income countries.14 Nearly 3 billion people worldwide are exposed to household air pollution from inefficient cooking and heating stoves,14 and almost the entire global population is exposed to detectable levels of outdoor air pollution from traffic, industry, and other sources.

Recent data released by WHO show that outdoor and household air pollution has a vast negative impact on both adult and child health and survival.14 United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) recently reported that deaths in Africa from outdoor air pollution increased from 164 000 in 1990 to 258 000 in 2017–a growth of nearly 60%–affecting especially the poorest children.16 In Asia, deaths attributable to PM2.5 increased from 3.5 million in 1990 to 4.2 million in 2015,17 many of them in children exposed to household air pollution from unventilated stoves and wood fires.14 In 2010 in China alone, outdoor air pollution was associated with >300 000 deaths, 20 million cases of respiratory illness, and annual healthcare costs >$500 billion, with children particularly susceptible.18 Especially in children whose organs are still developing, exposure to PM can result in adverse cardiopulmonary effects early in life19 and WHO estimates about 93% of the world's children aged <15 years (1.8 billion children) breathe air that is so polluted it puts their health and development at serious risk.7 In fact, the damage from air pollution often has already been inflicted even before birth, as maternal exposure to air pollutants during pregnancy has been shown to be associated with increased adverse birth outcomes such as stillbirth, low birth weight, and preterm birth.20, 21, 22 In particular, families living in environments with high levels of household air pollutants have low child survival rates23 and increased neonatal morbidity and mortality.24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 A new, yet‐unpublished study from the Cardiff School of Medicine that followed 8 million live births in the U.K. and Wales between 2001 and 2012, found that babies who grow up breathing polluted air—compared with those living in non‐polluted regions—have a higher risk of death as a neonate (38%), between 1 and 12 months of age (54%), or during infancy (43%).30

Tobacco Smoke Pollution

Tobacco use significantly increases the risk for many serious human diseases, but its greatest effect on morbidity and mortality is through promoting CVD31, 32 and the tobacco‐related risk for symptomatic atherosclerotic CVD is ≈40%.33 Air pollution‐induced CVD shares common pathways with tobacco‐induced CVD, and air pollution from combustion sources is a complex mixture of carbon‐based particles and gases similar to tobacco smoke.34 Although a greater body of literature exists on studies of tobacco smoke exposure, the precise toxic components and the mechanisms involved in smoking‐related cardiovascular dysfunction are not completely known, but we know that cigarette smoking increases inflammation, thrombosis, and oxidation of low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol,32 similar effects produced by pollution exposure. Also, increased hypertension, obesity, and insulin resistance—components of metabolic syndrome—have been reported to be associated with tobacco exposure,35 similar to what has been reported for ambient pollution exposure (Table). As with indoor and outdoor pollution, we have seen similar patterns of epigenetic changes including increased methylation in newborns and adults exposed to tobacco smoke.36, 37, 38

Table 1.

CVD Risks From Pollution Exposure in Pregnant Women, Neonates, Children, and Adults

| Cardiovascular Risk | Timing of Exposure | Exposure | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | Neonatal | PM2.5 | Increased blood pressure in ages 3 to 9 y | Zhang M (2018)39 |

| Children 1 to 10 y; Adolescents 10 to 19 y | PM2.5 | Increased blood pressure | Zhang M (2019)40 | |

| Newborns | PM2.5 | Increased systolic blood pressure | Van Rossem L (2015)41 | |

| School children, 6 to 12 y | Ultrafine particles (<100 nm) | Increased systolic blood pressure | Pieters N (2015)42 | |

| 12 y | Long‐term exposure to NO2 and PM2.5 | Increased diastolic blood pressure | Bilenko N (2015)43 | |

| Women 18 to 84 y | PM2.5 | Increased blood pressure | Curto A (2019)44 | |

| adults | Pollution from cookstoves | Increased systolic pressure | Fedak KM (2019)45 | |

| Obesity | Pregnant women | Traffic‐related air pollution | Higher cord blood levels of leptin and high molecular weight adiponectin, adipokines associated with increased infant weight change in female infants. | Alderete TL (2018)46 |

| 5 to 14 y | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and fine PM | The prevalence of obesity was 20.6% at age 5 y and increased across follow‐ups until age 11 y when it was 33.0% | Rundle A (2019)47 | |

| 10 to 18 y | Traffic‐related pollution | Increased BMI, mostly in females at age 18 y | Jerrett M (2010)48 | |

| 5 to 7 y | Traffic‐related air pollution | A 13.6% increase in the rate of average annual BMI growth between the children exposed to the lowest to the highest tenth percentile of air pollution | Jerrett M (2014)49 | |

| Birth to 6 mo | Black carbon, PM2.5 | Infants exposed to higher traffic‐related pollution in early life may exhibit more rapid postnatal weight gain and reduced fetal growth in mothers exposed to PM2.5 | Fleisch AF (2015)50 | |

| Adults, meta‐analysis | Chemical pollutants (polychlorinated biphenyls, others) | Positive associations between pollutants and obesity | Wang Y (2016)51 | |

| Glucose metabolism abnormalities, Diabetes mellitus | Pregnant women | NO2, PM2.5 | Gestation diabetes mellitus in first and second trimester | Choe S (2019)52 |

| 8 to 18 y | Ambient and traffic‐related ambient pollution | Higher insulin resistance and secretion, which was observed in conjunction with higher glycemia | Toledo‐Corral C (2018)53 | |

| 6 to 13 y | Medium‐term exposure to ambient PM2.5 and PM10 | Higher fasting blood glucose levels | Cai L (2019)54 | |

| 5 y | Traffic‐related exposure to ozone and PM10. | Increased ozone exposure may be a contributory factor to the increased incidence of type 1 diabetes mellitus. PM10 may be associated with development of type 1 diabetes mellitus before 5 y of age | Hathout E (2002)55 | |

| 10 y | Traffic‐related air pollution | Insulin resistance increased by 17% for every 2 SD of increase in ambient PM and NO2 | Thiering E (2013)56 | |

| 12 to 19 y | Tobacco smoke | Environmental second‐hand tobacco smoke exposure was independently associated with the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus | Weitzman M (2005)57 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 45 to 84 y | PM2.5 and black carbon exposure 2 wk, 3 mo, 1 mo | Air pollution is adversely associated with HDL | Bell G (2017)58 |

| 18 to 29 y (23±5 y) | PM2.5, black carbon, NO2, CO | High ambient air pollution concentrations associated with impairments in HDL functionality from systemic inflammation and oxidative stress | Li J (2019)59 | |

| Children and adults | PM10 | PM10 associated with elevated triglycerides, apolipoprotein B, and reduced HDL | Chuang K (2010)60 | |

| Adults | PM2.5 | Long‐term PM2.5 exposure associated with lipoprotein increases | McGuinn L (2019)61 | |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | Adults | Second‐hand smoke | Exposure during gestational development and during childhood was associated with having atrial fibrillation later in life | Dixit S (2016)62 |

| Adults | PM2.5 and PM10 | Increased risk of atrial fibrillation | Liu X (2018)63 | |

| Older adults (median 71 y) | PM2.5 and PM10 | In patients exposed to PM10 and PM2.5 followed for 1 y, ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation correlated significantly with PM2.5 but not PM10 | Folino F (2017)64 | |

| Young adults | Ultrafine particles (5–560 nm), black carbon, NO2 and CO, SO2, and O3 | Significant increases in QTc, indicating cardiac repolarization abnormalities particularly in males overweight/obese and with higher C‐reactive protein levels | Xu H (2019)65 | |

| Stroke | Post‐menopausal women | NO2 and NOx | In a large cohort of postmenopausal women, strong association between daily NO2 and NOx exposure and hemorrhagic stroke more pronounced among non‐obese participants | Sun S (2019)66 |

| Adults | PM2.5 and PM10, NO2, NOx, SO2, and O3 | Air pollutants are significantly associated with ischemic stroke mortality | Hong YC (2002)67 | |

| Adults | PM10, NO2, NOx, SO2, and O3 | All pollutants associated with primary intracerebral hemorrhage and ischemic stroke patients | Tsai SS (2003)68 | |

| Atherosclerosis | Adults | PM2.5 | In older men and women (>60 y), significant associations between PM2.5 and carotid thickness | Kunzil N (2005)69 |

| Adults 45 to 84 y | PM2.5 | Concentrations of PM2.5 and traffic‐related air pollution within metropolitan cities associated with coronary calcification, consistent with acceleration of atherosclerosis | Kaufman JD (2016)70 | |

| Adults | PM2.5 | PM2.5 exposure associated with increased likelihood of having mild and especially severe coronary atherosclerosis | Hartiala J (2016)71 | |

| Adults | PM2.5 | Exposure to higher concentrations of PM2.5 in ambient air was significantly associated with development of high‐risk coronary plaques | Yang S (2019)72 |

BMI indicates body mass index; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; and PM, particulate matter.

Particulate Matter Pollution

Both chronic and acute exposure to pollutants like PM2.5, as well as to tobacco, activate the release of proinflammatory and vasoactive factors that contribute to cardiopulmonary pathology4. The pulmonary effects of PM2.5 and PM10 are well known and include decreased lung function and increased risks of lung infection, asthma, bronchitis, disorders for which children are particularly vulnerable, as well as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer in adults.73, 74, 75, 76, 77 Epidemiological and clinical studies have increasingly shown that air pollution is associated with not only respiratory diseases but also CVD.6 In fact, PM2.5 is the pollutant with the most compelling observational and experimental evidence of association with increased risk of cardiovascular mortality.78 As we detail in this review, ambient PM2.5 is strongly associated with increased CVD such as myocardial infarction (MI), cardiac arrhythmias, ischemic stroke, vascular dysfunction, hypertension and atherosclerosis78 (Table). Ambient PM2.5 exposure is among the leading causes of world‐wide mortality, particularly from CVD79 and exposure to PM2.5 increases the risk of hospitalizations from CVD.80 Accordingly, reducing exposure to PM2.5 would benefit public health by decreasing both immediate and long‐term CVD risk.4, 12, 79, 81, 82, 83

Pollution in the Disadvantaged

In addition, economically disadvantaged groups are disproportionately vulnerable to air pollution and its negative health effects.84 An underprivileged environment is clearly linked to increased risks for CVD and other diseases.2 This is because low‐income residents in urban settings often live closer to major roadways, power plants, and industrial facilities, and in neighborhoods with other environmental risk factors (noise, crime, little green space, food deserts) and poor‐quality housing compared with those living under better conditions.85 Indoor pollution caused by cooking with fires burning solid fuels or dirty stoves fueled by kerosene is of particular concern for children living in such households.85 In poorly ventilated houses with families living in low‐ and middle‐income countries, the burning of solid fuels, kerosene, incense, and mosquito coils increases indoor PM, irritating respiratory tract, eyes, and skin86, 87 and, according to WHO, is responsible for around nearly 4 million deaths from serious cardiopulmonary diseases.15

CVD Risk From Pollution: From Birth to Adulthood

The large and growing body of scientific evidence points to a causal relationship between elevated air pollution and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.3 Such evidence places nearly 2 billion children at serious lifetime CVD risk.7, 14 These children are disproportionately in low‐socioeconomic‐status households, with little control over their home and social environment. Further, maternal exposures to pollution during pregnancy has also been linked to increased propensity towards developing future CVD risk.88 The published evidence about the adverse effects of pollution exposure on major CVD risks and cardiovascular phenotypes in pregnant women, neonates, children, and adults is summarized in Table and discussed in detail below.

Hypertension

Children with high systolic blood pressures are at increased risk of hypertension and the metabolic syndrome later in life.89 Recent evidence suggests that air pollution exposure in pregnancy may also portend increased risk for the next generation. In the prospective Boston Birth Cohort of 1200 mothers, Zhang et al39 found that PM2.5 exposure during pregnancy was associated with elevated blood pressure in children ages 3 to 9 years; further, in another study, these authors found long‐term exposure to ambient PM was also associated with higher prevalence of hypertension in children and adolescents.40 In addition, exposure to PM2.5 during late pregnancy was positively associated with systolic hypertension in newborns41 and in a cohort of 1131 mother‐infant pairs exposed to PM2.5, newborn infants showed systolic hypertension,41 an association also seen in smoking mothers.90 Children attending school on days with higher concentrations of PM (diameter <100 nm) had higher systolic blood pressures.42 In addition, children aged 6 to 12 years exposed to ultrafine PM or PM2.5 in combination with NO2 demonstrated increased systolic and diastolic blood pressures.42, 43 Curto et al44 found that adult women aged 18 to 84 years living in India exposed to PM2.5 had increased systolic blood pressure. Finally, even short‐term exposure to air pollution from cookstoves elicited increases in systolic blood pressure in adults.45

Obesity

Airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) is a family of pollutants that have been most strongly associated with obesity, although PM2.5 and NO2 have been linked with obesity as well. PAH are created during incomplete combustion processes and are known to have endocrine disrupting effects, and alter the behavior of adipocytes, promoting obesity.91, 92, 93, 94, 95 Alderete et al46 found pregnant women exposed to traffic‐related air pollution had higher cord blood levels of leptin and high‐molecular‐weight adiponectin, which were associated with increased infant weight gain, which may have implications for future obesity risk. Adolescents exposed to air pollution and PAH during the pre‐term/neonatal period had increased prevalence of obesity and diabetes mellitus.47 In 1 study, Jerrett et al48 examined traffic pollution around family homes in the United States and found that higher levels of vehicular traffic and pollution were associated with higher attained body mass index in children aged 10 to 18 years, particularly females aged 18 years. In 1 community of Southern California, pollution from automobiles was positively associated with higher body mass index in children aged 5 to 11 years.49 Infants exposed to black carbon and PM2.5 emissions from traffic pollution in early life exhibited rapid postnatal weight gain.50 Wang et al51 found a positive association between several pollutants and obesity in a meta‐analysis of 35 studies.

Insulin Resistance and Diabetes Mellitus

Animals exposed to air pollutants during pregnancy show an increased risk of metabolic syndrome, birth defects, and diabetes mellitus.96 Animal studies have also demonstrated that PM2.5 exposure enhances insulin resistance and visceral inflammation/adiposity, providing a strong link between air pollution and type 2 diabetes mellitus.97 This has been borne out in human studies. In a large cohort of singleton births in New York City, mothers’ exposure to NO2 in the first trimester and PM2.5 in the second trimester were associated with higher odds of gestational diabetes mellitus.52 In a cohort of 429 overweight and obese minority children in Los Angeles, increased prior‐year exposure to traffic‐related air pollution adversely affected type 2 diabetes mellitus‐related pathophysiology.53 Further, in 4234 children aged 6 to 13 years, Cai et al54 found exposure to ambient PM2.5 and PM10 was associated with higher fasting blood glucose levels. Hathout et al55 reported that exposure to fine particulates such as PM10 was a specific contributing factor for type 1 diabetes mellitus in children aged <5 years. In another study, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus were greater in 10‐year‐old children exposed to high levels of traffic‐related air pollution compared with those children exposed to lower levels.56 Finally, indoor exposure from second‐hand tobacco smoke was associated with an increase in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus in adolescents aged 12 to 19 years.57

Dyslipidemia

In Chinese men and women, Bell et al58 found that exposures to PM2.5 and black carbon (2 weeks, 3 months, and 1 year) was associated with lower concentrations of high‐density lipoprotein. In a 2‐year study, 73 young adults (23±5 years) exposed to traffic‐related pollution (PM2.5, black carbon, NO2, CO) had significant reductions in high‐density lipoprotein and apolipoprotein A‐I (ApoA1) indicating impairments in lipoprotein functionality as a result of systemic inflammation and oxidative stress.59 In a cohort of Taiwanese children and adults, Chuang et al60 found that individuals exposed to PM10 over time had elevated triglycerides, apolipoprotein B, and reduced high‐density lipoprotein levels, indicating a link between air pollution and progression of atherosclerotic disease. In a recent 9‐year study of 6587 adults in the United States, long‐term exposure to PM2.5 was associated with increased lipoprotein concentrations.61

Cardiac Arrhythmias

Arrhythmia is another potential manifestation of air pollution exposure that could lead to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.98 Adults having had a smoking parent during gestational development and those living with a smoker during childhood were each significantly associated with atrial fibrillation, which was more pronounced among adults without risk factors for atrial fibrillation.62 In a study of 100 adults exposed over to PM2.5 and PM10 over several months, an increased risk of atrial fibrillation was seen.63 In another study of 281 patients (mean 71 years) exposed to PM10 and PM2.5 followed for 1 year,64 ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation correlated significantly with PM2.5 (P<0.001) but not PM10. In these older adults, an analysis of the ventricular fibrillation episodes alone correlated significantly with higher PM2.5 and PM10 exposure. Finally, Xu et al65 followed 73 healthy young adults living in China under continuous pollution (particulates 5–560 nm diameter, black carbon, NO2, CO, SO2, and O3) using 24‐hour electrocardiographic recordings, and found that the young participants showed cardiac repolarization abnormalities (increased QTc interval), which were most strongly associated with nano‐sized PM, with traffic‐related pollutants (black carbon, NO2, and CO), and with SO2, and O3. The associations were stronger in males who were overweight and had higher levels of C‐reactive protein levels.

Stroke

Evidence from epidemiological studies has demonstrated a strong association between air pollution and stroke.99 Among 5417 confirmed strokes in 5224 women between 1993 and 2012 in Asia exposed daily to particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), NO2, NOx, SO2, and O3, Sun et al66 found a positive association between risk of hemorrhagic stroke and NO2 and NOx but not with the other pollutants in the 3 days before a stroke. A 7‐year study in Korea showed significant associations between PM2.5 and PM10, NO2, NOx, SO2, and O3 and the incidence of ischemic but not hemorrhagic stroke mortality, suggesting clinically significant alterations in the cerebrovascular system induced by air pollution.67 Finally, in a study of 23 179 stoke admissions in Taiwan between 1997 and 2000, Tsai et al68 reported significant positive associations between levels of PM10, NO2, SO2, O3, and CO and primary intracerebral hemorrhage as well as ischemic stroke.

Atherosclerosis

In mice prone to developing atherosclerotic lesions, chronic exposure to concentrated ambient PM produced aortic plaques that were significantly more advanced compared with non‐exposed mice, indicating long‐term exposure to PM can produce adverse cardiovascular effects by enhancing atherosclerosis.100 The atherosclerotic disease process begins early as suggested by human autopsy studies that have found fatty streaks, indicating the early stages of atherosclerosis, in coronary arteries of teenagers.1 In fact, fatty streaks have been observed in children as young as 3 years of age with coronary involvement identified at adolescence.101 Several studies confirm that the risk factors observed in adults (eg, elevated low‐density lipoprotein, obesity, hypertension, tobacco exposure, and diabetes mellitus) also contribute to atherosclerosis in children.102, 103 In particular, pollution has been shown to induce the progression of atherosclerosis and CAD. In a study of 798 adults in 2 clinical trials, among older participants (≥60 years), women, never smokers, and those reporting lipid‐lowering treatment at baseline, showed significant associations between PM2.5 and carotid intimal‐media thickness, with the strongest associations found in women aged ≥60 years.69 In a prospective, 10‐year cohort study of 6795 adults aged 45 to 84 years living in metropolitan cities, it was found that increased concentrations of PM2.5 and traffic‐related air pollution commonly encountered worldwide, were associated with the progression of coronary calcification, consistent with acceleration of atherosclerosis.70 In a longitudinal study of 6575 adults undergoing coronary angiography, exposure to PM2.5 was associated with increased likelihood of having coronary atherosclerosis that was mild to severe.71

Mechanisms of CVD From Pollution Exposure

Currently available evidence has demonstrated that systemic inflammation and immunological responses—derived from pollutants coming into contact with the epithelial lung lining and entering the systemic circulation—initiate a cascade of events leading to the acute and chronic effects of pollution on CVD.104 Based on our current knowledge, plausible pathophysiological mechanisms linking exposure to pollutants (primarily PM2.5) and CVD include: (1) increased systemic inflammation, which produce cardiovascular stress105, 106; (2) activated platelets in the bloodstream, increasing the risk of acute thrombosis, as in MI and ischemic stroke107, 108; (3) alterations of the autonomic nervous system and the autorhythmic cells in the sinoatrial node, which leads to decreased heart rate variability, a prognostic risk factor for heart disease109, 110; and (4) direct changes in the vascular cell types, including macrophages, endothelial and smooth muscle cells, thereby increasing CVD risk.106 However, because of the lack of a standard modeling platform, the mechanisms underlying PM‐induced cardiopulmonary toxicity in humans are still not well understood, making clinical management of air pollution‐related cardiovascular risks difficult and impeding the development of effective preventive approaches.111

Improving our understanding of the specific molecular or immunological pathways underpinning pollution‐driven CVD will allow us to develop targeted therapies for individuals living in areas of high pollution or those genetically predisposed to pollution‐driven CVD.

Increased Systemic Inflammatory Burden of Pollution: Interleukin‐1β and the Inflammasome

Exposure to pollutants generates airway oxidative stress and inflammation.112 Furthermore, these local lung responses spill over, and ultrafine PM can cross the alveolar capillary membrane to the blood stream and produce systemic inflammatory and immunological responses by activating circulating immune cells.113 Multiple studies indicate an increase in the systemic inflammatory burden in response to air pollution exposure as measured by biomarkers, including interleukin (IL)‐6, IL‐8, C‐reactive protein, IL‐1β, and monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1 (MCP‐1).113, 114, 115 Gruzieva et al measured a panel of blood inflammatory markers from 8‐year‐old children (n=670) who had been exposed to traffic NO2 and PM10 in early life and also examined gene data from 16‐year‐olds that had been exposed to traffic NO2 and PM10. In this cohort, a 10 μg/m3 increase of NO2 exposure during their infancy was associated with a 13.6% increase in IL‐6 levels, as well as with a 27.8% increase in IL‐10 levels, which was limited to children with asthma. Results were similar using PM10, which showed a high correlation with NO2 exposure. The functional analysis of 16‐year‐olds in this study identified several differentially expressed genes in response to air pollution exposure during infancy, including IL10, IL13, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF). In a group of healthy young adults, episodic PM2.5 exposure was associated with increased levels of circulating monocytes and T cells along with increased levels of TNF‐α, MCP‐1, IL‐6, IL‐1β, and chemoattractants including soluble intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 (sICAM‐1) and circulating vascular cell adhesion molecule‐1 (sVCAM‐1).114 This response appears to be dose‐dependent, and several components of air pollution including PAHs—NO2, PM2.5, and PM10—have been associated with increases in inflammatory biomarker signatures. The inflammatory cytokines are likely derived mainly from the cells in the lung epithelium and the circulating immune cells. Additionally, PM10 was found to stimulate alveolar macrophages to release the prothrombotic cytokine IL‐6, which activates pathways that can accelerate arterial thrombosis and increase the risk of cardiovascular events.116 Both chronic and acute exposures to PM2.5 activate the release of proinflammatory and vasoactive factors that contribute to cardiopulmonary pathology and accordingly, reducing exposure to PM2.5 would benefit cardiopulmonary health by decreasing both immediate and long‐term cardiopulmonary disease risk.4, 12, 79, 81, 82, 83

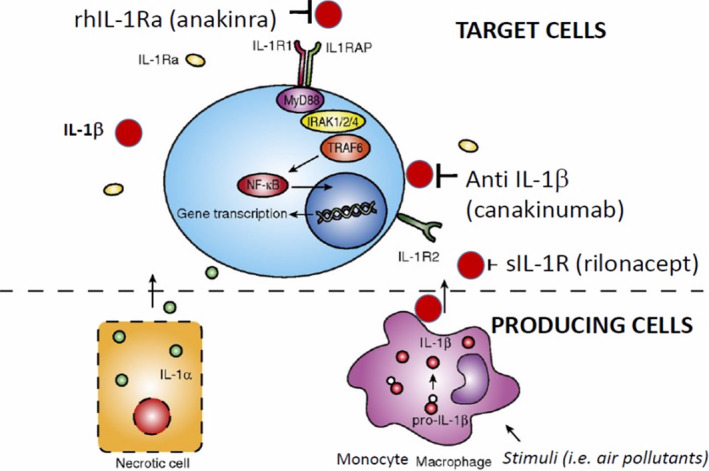

A sensor of cell injury called the “inflammasome,” which includes an IL‐1β‐processing platform, plays a crucial role in IL‐1β maturation and secretion from cells. Nucleotide‐binding domain (NOD)‐like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes monitor membrane integrity and pore‐forming toxins, crystals, and many other noxious stimuli and are involved in IL‐1β processing and maturation.117, 118, 119 Produced by epithelial and inflammatory cells, IL‐1β plays a central role in the inflammatory processes in blood, lung, cardiac, and vascular tissues. IL‐1β is initially synthesized as pro‐IL‐1β, an inactive precursor. Pro‐IL‐1β is then cleaved inside the cell by the inflammasome complex.120 Once pro‐IL‐1β is processed, the mature IL‐1β product is secreted and binds to the IL‐1 receptor (Figure 2, 121). In non‐lymphoid organs, IL‐1β is expressed in tissue macrophages in the lung.122, 123 There are 2 cell‐surface IL‐1 receptors, IL‐1 type receptor (IL‐1R1) and IL‐1R2, a decoy receptor. IL‐1R1 initiates inflammatory responses when binding to IL‐1β and has been reported to be expressed by T‐ lymphocytes, cardiac‐derived and lung‐derived fibroblasts, alveolar epithelial type II cells and vascular endothelial cells. IL‐1R2, which does not initiate signal transduction, is expressed in a variety of hematopoietic cells, especially in B lymphocytes, mononuclear phagocytes, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and bone marrow cells. Notably, expression levels of IL‐1R1 and IL‐1R2 are different among the cell types; for example, alveolar epithelial type II cells express IL‐1R1, but not IL‐1R2. The IL‐1β pathway has been targeted effectively by different products available as inhibitors for human use as recombinant human or soluble inhibitors (Figure 2).120

Figure 2.

Potential therapeutic targets on the interleukin‐1 pathway.

IL indicates interleukin; IL1RAP, Interleukin‐1 receptor accessory protein; IL‐1R1, Interleukin 1 receptor, type I; IL‐1R2, Interleukin 1 receptor, type II; IRAK 1/2/4, interleukin‐1 receptor‐associated kinase 1, 2, 4; MyD88, Myeloid differentiation primary response 88; NF‐kB, Nuclear Factor kappa‐light‐chain‐enhancer of activated B cells; rh, recombinant human; rhIL‐1RA, recombinant human interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist; sIL‐1R, soluble type 1 interleukin‐1 receptor; and TRAF6, TNF receptor associated factor 6.

IL‐1β is linked to exposure to air pollution. PM2.5 exposure has been shown to increase rates of reactive airway disease and MI associated with the release of IL‐1β from monocytes and macrophages.7, 8 Components of PM from air pollution, including PAHs, activate human monocytes by stimulating cells such as pulmonary endothelial cells, showing that inhaled PM from pollution induces pulmonary and systemic inflammation.124 Different mechanisms have been proposed for the activation of the inflammasome by air pollution.125, 126 Among them, the NLRP3 inflammasome is a prototype inflammasome, which has been reported to be activated by diesel exhaust, tobacco smoke, e‐cigarette liquid, ozone, and reactive oxygen species in pollution.127 Provoost et al128 recently published a study in a murine model demonstrating that air pollution particle‐induced pulmonary inflammation was mediated by IL‐1β, but was NLRP3/caspase‐1‐independent. Our research using blood samples from 100 adolescents exposed to known quantities of ambient air pollution show that, even after 1 week of ambient air pollution exposure, there was a significant (P=0.017) association between IL‐1β increases in plasma and increases in ambient air pollution exposure, specifically PM2.5.129

Epithelial Activation Barrier and Inflammation From Pollution

In considering the pathways that pollutants gain entry to the bloodstream, epithelial cells should be considered the first line of defense, as they are essential components of the innate immune response and are barriers to pollutants. Upper and lower respiratory epithelial cells are exposed to air pollution, whereas gastrointestinal epithelial cells are exposed to food and water pollution. Mucosal epithelium produces antimicrobial peptides, cytokines, and chemokines, activates intraepithelial and subepithelial cells, which supports the physical, chemical, and immunological barrier.130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136 Epithelial cells respond to pollution by releasing cytokines such as IL‐25, IL‐33, and TSLP, which initiate inflammation by activating dendritic cells, T helper cells, innate lymphoid cells, and mast cells.137 Once exposed to pollution, the epithelial tight‐junctions barrier in the nasal and oral mucosa open, allowing pollutants to enter directly into the bloodstream and deeper tissues,132, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148 which initiate distant tissue inflammation like in the cardiovascular systems. For example, exposure to PM2.5 has shown to break down the nasal epithelial barrier by breaking down cellular tight junctions and release proinflammatory cytokines,149 which play key roles in the progression of cardiovascular and cardiopulmonary diseases.150, 151, 152, 153

Currently there are substantial data showing that pollutants such as cigarette smoke, particulate matter, diesel exhaust, ozone, nanoparticles, detergents, as well as cleaning agents and chemicals in household substances all can damage and open the epithelial barrier.149, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163 Opening this barrier initiates the inflammatory cascade in tissues, especially cardiac and pulmonary tissues, which become vulnerable to systemic inflammation and the damaging effects of air pollution, particularly in children and young adults.164

Vascular Remodeling

Research has shown that fine and ultrafine particles can cross the alveoli, and enter the bloodstream, directly affecting tissues involved in CVD.165 Specifically, one study found in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy that inhaled gold nanoparticles entered the blood stream and became deposited in the carotid artery.166 In fetuses of pregnant mice, pollutants alter vascular development manifested at birth as atrial septal defects and coronary malformation.167 Brook et al168 found that after only 2 hours of inhalation of fine PM and ozone at concentrations found in urban environments, healthy young adults showed significant brachial artery vasoconstriction. Also, healthy college students with a history of prenatal exposure to air pollution, compared with those not exposed, had significant carotid artery stiffness.169 These studies suggest that the increased inflammatory signal is derived not only from the pulmonary exposure, but also a direct exposure of the vascular wall to systemic oxidative stress and inflammation, leading to activation of the pathways causing vascular injury and vascular remodeling via atherosclerosis and plaque buildup. In children whose vasculature is still developing, exposure to pollution can alter the structure and function of the vascular wall and potentially predispose them for future cardiovascular complications as shown by a recent study of 733 Dutch children aged 5 years demonstrating that exposure to PM2.5 and nitrogen oxides caused decreased arterial distensibility.170

Endothelial Injury

Individuals exposed to fine PM from pollution have signs of endothelial injury and dysfunction along with increased markers of systemic inflammation.171 Specifically, episodic PM2.5 exposure in young adults was associated with increased antiangiogenic plasma profiles and elevated levels of circulating monocytes and T (but not B) lymphocytes, indicating increased endothelial cell apoptosis.114 Similarly, healthy young non‐smoking males exposed to ultrafine PM and gases demonstrated 50% reduction in endothelial function, as measured by flow‐mediated dilation of the brachial artery.172 These authors concluded that gaseous pollutants affect large artery endothelial function, whereas PM inhibit the post‐ischemic dilating response of small arteries. Further, patients with diabetes mellitus exposed to PM2.5, black carbon, and sulfates showed decreased endothelium‐dependent and endothelium‐independent vascular reactivity, particularly to PM2.5 and black carbon, and the effect was more pronounced in those with type‐2 diabetes mellitus.173

Plaque Instability

In mice exposed to diesel emissions, formed plaques were advanced to a fragile, vulnerable state.174 Chronic pollution exposure of children, adolescents, and adults can potentially lead to a shift in the plaque morphology and content towards a more vulnerable state. In adults, even short‐term pollution exposure was associated with higher levels of biomarkers consistent with reduced plaque stability.175 Furthermore, Yang et al72 found that PM2.5 exposure was correlated with the development of plaque with higher‐risk characteristics based on CT analysis suggesting that pollution exposure can modify plaque stability, which increases the risk of MI.

Platelet Aggregation and Thrombosis

Another potential CVD outcome is increased MI and stroke from acute exposure to pollution. Specifically, PM exposure has been linked to CVD and stroke, possibly mediated through proinflammatory or pro‐thrombotic mechanisms.176, 177 As noted above, exposure to PM2.5 has been linked to an increase in systemic oxidative stress and inflammation as well as a modulatory effect on tissue factors that have all been implicated as potential mechanisms of increased platelet activation.178 The aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway has also been implicated in increasing tissue factor production from vascular smooth muscle cells in response to ligand activation, leading to increased thrombosis.179 This has been confirmed by research in adults exposed to air pollution.180 In healthy adults exposed to traffic‐related pollution, Xu et al175 reported increased thrombogenicity as measured by prothrombin time and fibrin degradation products. Additionally, in a 10‐year study of 870 patients with deep vein thrombosis and 1210 controls, Baccarelli et al181 found that higher mean PM10 exposure during the year before examination was associated with shortened prothrombin time and increased deep vein thrombosis risk.

Epigenetics and Gene‐Environment Interactions

Exposure to pollution has also been linked to an altered epigenetic state. Specifically, exposure to PAH and tobacco smoke contribute to gene expression modifications through epigenetic remodeling by 3 primary targets: CpG methylation, amino acid tail modification on histones, and aberrant microRNAs expression.182 Histone modification via methylation occurs post‐translationally while miRNAs can control expression of other genes post‐transcriptionally.183 Changes to these targets can influence DNA folding, DNA‐transcription factor interaction, transcript stability, and other methods of gene silencing (heterochromatin) or activation (euchromatin). Several studies indicate a role of pollution‐produced epigenetic remodeling on the immune system. DNA methylation has been associated with changes in IL‐4 and IFN‐γ transcription.183 Studies with mouse models demonstrate that increases in immunoglobulin E levels are associated with hypomethylation at IL‐4 promoter CpG sites and hypermethylation of IL‐4 and IFN‐γ promoter CpG sites.184 Histone acetylation is associated with IL‐4, IL‐13, IL‐5, IFN‐γ, CXCL10, and FOXP3+ transcription patterns.183 Finally, miRNA‐mediated silencing has been found to repress transcripts associated with human leukocyte antigen G, or HLA‐G, IL‐13, IL‐12p35, transforming growth factor beta, or TGFβ, and the pituitary‐specific, Octamer, Neural, or POU domain, a bipartite DNA binding domain.183 Importantly, we believe these epigenetic modifications from exposure to air pollution may have the greatest consequences to prenatal and infant populations.182

We and others have found an increase in the global methylation signal in the peripheral blood of children and adults exposed to pollution.129, 185, 186, 187, 188 Furthermore, pollution exposure‐related effects may be inherited to the fetus through epigenetic mechanisms.189 The inheritance of epigenetic modification in the mother could potentially result in babies and children more prone to increased obesity and hypertension. Gruzieva et al36 examined associations between NO2 exposure and cord blood DNA methylation in pregnant women and also NO2 exposure in children aged 4 and 8 years. Exposure to NO2 during pregnancy was associated with differential offspring DNA methylation in mitochondria‐related genes and was also linked to differential methylation as well as expression of genes involved in antioxidant defense pathways. In this study, Gruzieva et al36 also found NO2 exposure of young children was linked to differential methylation as well as increased expression of genes involved in antioxidant defense pathways.

Genetic alterations also likely contribute to susceptibility of a child to the development of cardiovascular alterations in response to air pollution exposure. Eze et al190 found that a common functional variant in the IL6 gene interacted with PM10 exposure‐dependent IL‐6 levels in the circulation. We have shown that an environment sensing transcription factor for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, which has been shown to be activated by several components of pollution and tobacco smoke, is regulated both transcriptionally and epigenetically by TCF21, a gene associated with increased risk for atherosclerosis and MI.191

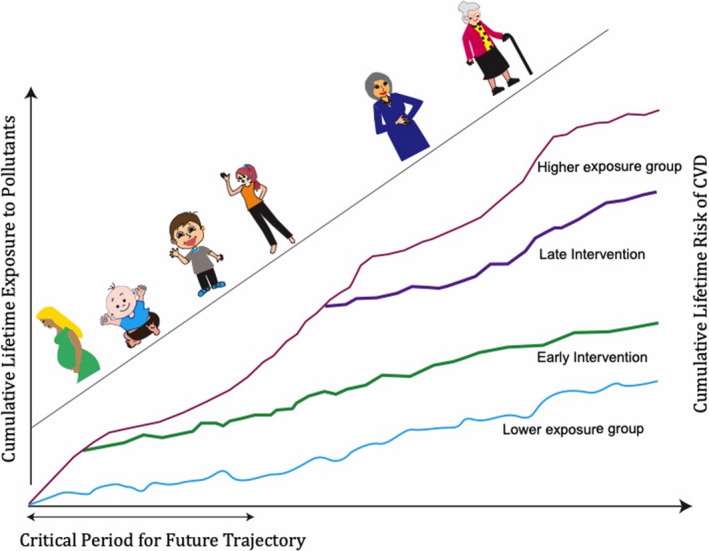

Lifetime Disease Risk—Strategies For Prevention and Intervention

As we have discussed, the evidence of air pollution exposure affecting cardiovascular health begins in the neonatal period and continues throughout childhood and adolescence. The lifetime risk of CVD is the accumulated risks from the developmental period into childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (Figure 3). Because children are most vulnerable to environmental influences, improving their environment and reducing pollutant exposure during this critical phase can have significant long‐term health benefits by altering the overall disease trajectory. Accordingly, this window of time offers an important opportunity for intervention.

Figure 3.

Early intervention can improve cumulative lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease.CVD indicates cardiovascular disease.

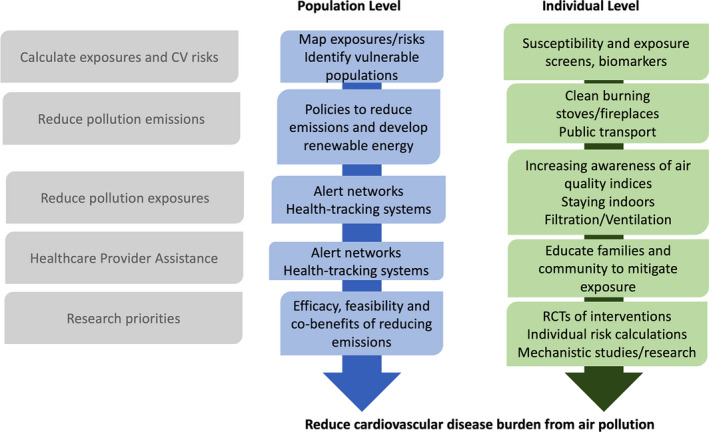

For maximum impact, interventions could be implemented at both the individual and population levels (Figure 4). At the individual level, children and parents can be taught several simple but effective measures to reduce exposures. First, increasing awareness of air quality indices has shown to significantly change pollution‐avoiding behaviors.192 Second, staying indoors and using personal protective devices such as N95 masks during acute periods of intense exposure, as well as use of home air filtration devices can significantly reduce pollution exposure. For example, N95 facemasks reduced acute particle‐associated airway inflammation in young healthy adults living in China.193

Figure 4.

Combined population‐level and individual‐level approaches for reducing exposures to air pollution and reducing cardiovascular disease burden.CV indicates cardiovascular; and RCT indicates randomized clinical trial.

Currently, there is little evidence that dietary intervention or chemoprevention (ie, antioxidant or antithrombotic agents) can have an overall long‐term survival benefit from pollution exposure. Carnosine supplementation has been shown to mitigate PM2.5‐induced effects on bone marrow stem‐cell populations in mice and may be one approach for preventing immune dysfunction in humans exposed to pollution.194 In addition, cobalamin (vitamin B12) supplementation has been shown to protect against superoxide‐induced cell injury in human aortic endothelial cells,195 one known outcome from oxidative stress after air pollution exposure.196 Recently, in a large prospective cohort of >500 000 individuals in the United States followed for an average of 17 years, Lim et al197 reported that, based on questionnaire of exposure history, there was a correlation between long‐term exposure to fine PM and CVD mortality risk, and a Mediterranean diet reduced this risk. Also, in 1 study of young students exposed to high levels of air pollution in China, use of omega‐3 fatty acids stabilized the levels of multiple biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress.198

Current Evidence‐Based Interventions

Although we know that interventions to reduce air pollution exposure can reduce the incidence of CVD, no randomized clinical trial has yet been proposed to demonstrate that long‐term reduction in pollution exposure results in reducing CVD mortality. We need to design randomized clinical trials that will establish the effectiveness of interventions; however, traditional randomized trials would not be practical for this purpose given the large number of participants required and the difficulty of implementing individual monitoring. Several ways to improve participant selection for a more targeted intervention trial would be to develop an individual risk‐calculator, and use biomarkers to identify higher‐risk patients.199, 200

Healthcare providers play a critical role to help reduce the harmful effect of air pollution on children. Not only can they treat children's illnesses, they can also help educate the community about factors that contribute to air pollution and work with community leaders to reduce exposures and mitigate risks. Research should be aimed at developing established consensus guidelines that can help providers effectively counsel patients and families who are dealing with acute or chronic exposures. Recently, Hadley et al11 outlined the role of healthcare providers and clinical approaches that factor in air pollution to preventive cardiac care. This includes a patient‐screening tool that indicates known risk factors for air pollution exposure and cardiovascular risks. Developing an individual risk calculator that incorporates pollution exposure with traditional risk metrics—such as the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and Atherosclerotic Cardiovasular Disease (ASCVD) 10‐year risk calculator—may help to further stratify patient risks so that interventions can be targeted to the higher‐risk groups.11

The 2004 American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations on the health hazards of air pollution in children201 underscore the importance of pediatricians who play an important role in educating families and children about the harmful effects of pollution and helping to reduce exposures. Pediatricians who serve as physicians for schools or for team sports should be aware of the health implications of pollution alerts to provide appropriate guidance to school and sports officials, particularly in communities with high levels of pollution.201 Physicians can do much to protect children by educating their local policymakers about the need for cleaner air and the need to replace older diesel buses, and limit school bus idling wherever children congregate.202

Population‐Based Approaches

At the population level, we need policy measures to decrease the overall emission of harmful pollutants. The American Heart Association has published several position papers on the role of pollution on cardiovascular health, and concluded that there is an urgent need to advocate for strong regulations and policy to curtail pollution.79 Regulations and fiscal strategies such as increased taxation of gasoline and diesel fuels or a carbon tax on emissions would effectively reduce air pollution levels. Other population‐level approaches include using monitoring stations to build exposure maps and community alert networks (Figure 4).

We also should consider optimizing air quality standards further. Current research suggests that current United States and European standards are still too high, especially considering the pediatric population that is more susceptible to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.203, 204 Furthermore, as discussed by Hadley et al,11 the most effective intervention occurs at lower pollution exposure levels, as most of the increase in conferred risk occurs at PM2.5 concentrations of 40 to 100 μg/m3, after which there is a plateau of accrued risk from pollution exposure.205, 206 Anecdotal and historical observations strongly suggest that interventions to reduce exposures to PM would reduce risk of CVD, just as implementing policies to reduce tobacco exposure can lower hospitalizations for cardiopulmonary diseases. For example, it has been estimated that full implementation of the New York City fuel oil regulations would prevent >300 premature deaths and >500 emergency department visits and hospitalizations for respiratory or cardiovascular causes each year.207, 208

Gaps in Knowledge and Research Needs

While most epidemiologic studies address the effects of short‐term pollution exposure on acute CVD outcomes, we believe more research is needed to understand the long‐term cumulative effects of air pollution on cardiovascular end points. The differences in the mechanisms leading to cardiovascular events from short‐term exposure and long‐term exposure are not well understood, and we need to better characterize the mechanisms from short‐term exposure (eg, from wildfires) and long‐term exposure (eg, from diesel exhaust). Many subclinical physiological changes occur in response to exposure to air pollution, and identifying these subclinical changes is one way to gain insight to the mechanisms leading to cardiovascular events.

Improved measurements of individual exposure are an important prerequisite for personalized care, and currently, pollution exposure to an individual is estimated mostly based on the person's location of residence. However, such an estimate does not include the amount of time the person might spend indoors versus outdoors, the amount of time spent at work or school, the extent of exposure to household pollution, as well as the vital capacity and respiratory rate of the person. Even when exposed to similar levels of pollution, children absorb more pollutants because they breathe more often than adults, are often outdoors more than adults, and are lower to the ground where some pollutants may concentrate.15 Several surrogate markers can be considered as a measure of exposure. A panel of blood biomarkers may allow us to estimate the systemic effect of both short‐term and long‐term exposures114 and, as we have seen, increased inflammatory markers such as IL‐6, IL‐1β, IL‐10, DNA methylation, and TNF have been found in young children and adults exposed to pollution.36, 115, 209 Also, measures of exhaled breath condensate, fluid formed by cooling down exhaled air, can be used to measure the amount of oxidative stress biomarkers—reactive aldehydes—and inflammatory markers related to pollution exposure.210 These biomarkers should be incorporated and tested for their efficacy in prospective trials of intervention, perhaps including anti‐IL‐1β therapies. Future research should also be directed toward better understanding the mechanism of epithelial barrier damage from particulate matter, ozone, nanoparticles, detergents, as well as cleaning agents and chemicals in household substances.

In this contemporary review, we have focused primarily on the effects of ambient air pollution, especially components of PM and PAHs. Although sufficient data are available to support preventive action, it is yet unclear how the different components of pollution—carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, ozone, ambient PM, and lead—each affect the cardiovascular system.

Of the different pollution components, fine PM is known to be highly toxic to the cardiopulmonary system. However, we still do not fully understand whether all types of PM (eg, wildfire smoke versus diesel exhaust) are equally toxic or which specific components determine toxicity. The most studied particle matter is PM2.5, which is especially harmful because they can penetrate into the pulmonary alveoli where they can induce a local inflammatory response. Ultrafine particles, a component of PM2.5, can penetrate the alveolar‐capillary barrier and enter the bloodstream. Several studies have established that PM induces inflammatory effects211, 212, 213 and oxidative stress,212, 214 yet it is not yet clear to what extent such effects are different for PM collected at different locations or from different sources.215 The proinflammatory and oxidative potential of PM may be influenced by variations in PM chemical and physical composition.216, 217 PM composition is determined by whether the emissions originate from cars, trucks, industry, or agricultural activities, and emissions are further affected by variations in temperature and meteorological conditions through atmospheric changes.218 As such, although much research has concentrated on the effects of PM in animals and humans, we still have limited information on PM chemical components from different sources and locations.219 PM, especially PM10, includes biological components such as fungal spores and endotoxins, elemental carbon, sulfur, nitrogen, metal compounds, and complex hydrocarbons such as PAH.10 Some of these PM components have been shown to induce systemic inflammation. For example, endotoxin and PAH initiate monocyte inflammatory responses mediated by reactive oxygen species,124, 220, 221 and transition metals (iron, manganese, chromium, copper) induce cytotoxicity and oxidative stress.222 While some studies indicate a degree of differential toxicity from such components as endotoxin, specific metals, PAH, and elemental carbon,218 current knowledge does not allow us to precisely quantify the health effects of individual PM components or PM from different sources. To better inform regulatory strategies in the future, we must more fully understand the health effects of various PM components from different sources, which will allow us to identify the causal agents. This will help formulate more targeted strategies for harm reduction. It will also help us to appropriately lower the current annual ambient air quality standards, considering the more susceptible populations, especially our children. Collaborating with rapidly developing countries, where extremely unhealthy air quality level is a daily concern, will help us to develop impactful research that will be applicable in both the United States and throughout the world.

Conclusions

With the rapid rise in industrial development came increased emission of air pollutants harmful to human health. Regardless of the pollution source, polluted air is shared by us all, especially our children, who are most vulnerable. The lifetime cumulative exposure to pollution is increasing in children, and current evidence shows that long‐term exposure, even in utero, leads to increased prevalence of hypertension, obesity, and metabolic disorders, resulting in a greater CVD burden in our future generations. The concept of life time and acute exposure should be well integrated to public health and devices to monitor individual and regional exposure should be improved and focused on new dangers of exposure. Development of biomarkers that identify the levels of exposure, tissue and systemic inflammation, and tissue damage is essential to overcome diseases linked to pollution. We must develop clinical guidelines to effectively mitigate the risk of increased exposure to pollution. Continued research into the mechanisms of pollution‐induced CVD and policies to limit emissions and promote preventive efforts to limit exposure, especially during childhood and adolescent years, all will have significant long‐term benefits for the future.

Sources of Funding

We received funding support from National Institutes of Health K08HL133375 (Kim), Tobacco‐Related Disease Research Program T30IP0999 (Kim), Tobacco‐Related Disease Research Program 27IR‐0012 (Wu), Sean N Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford University (Nadeau, Dant, Smith, Prunicki, Patel), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences P01ES022849‐05 (Nadeau), NHBLI R01HL118612 (Nadeau), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences R01ES020926 (Nadeau).

Disclosures

Dr Nadeau reports grants from National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Food Allergy Research & Education, End Allergies Together, Allergenis, and Ukko Pharma; grant awardee at National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the Environmental Protection Agency; involved in Clinical trials with Regeneron, Genentech, AImmune Therapeutics, DBV Technologies, AnaptysBio, Adare Pharmaceuticals, and Stallergenes‐Greer; Research Sponsorship by Novartis, Sanofi, Astellas, Nestle; Data and Safety Monitoring Board member at Novartis and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; co‐founded BeforeBrands, Alladapt, ForTra, and Iggenix; director of Food Allergy Research & Education and World Health Organization (WHO) Center of Excellence; personal fees from Regeneron, Astrazeneca, ImmuneWorks, and Cour Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Akdis reports grants from Allergopharma, grants from Idorsia, grants from Swiss National Science Foundation, grants from Christine Kühne‐Center for Allergy Research and Education, grants from European Commission's Horison's 2020 Framework Programme, Cure, grants from Novartis Research Institutes, grants from Astra Zeneca, grants from Scibase, advisory board membership in Sanofi/Regeneron. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Acknowledgments

All authors listed on this review contributed to the scientific content and editing in their areas of expertise. The authors thank Dr Aaron Bernstein of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at Harvard Medical School for his suggestions.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014944 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014944.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 15.

References

- 1. Zieske AW, Malcom GT, Strong JP. Pathobiological determinants of atherosclerosis in youth (PDAY) cardiovascular specimen and data library. J La State Med Soc. 2000;152:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bhatnagar A. Environmental determinants of cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2017;121:162–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brook RD, Franklin B, Cascio W, Hong Y, Howard G, Lipsett M, Luepker R, Mittleman M, Samet J, Smith SC Jr, et al. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the expert panel on population and prevention science of the american heart association. Circulation. 2004;109:2655–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hadley MB, Vedanthan R, Fuster V. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a window of opportunity. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:193–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chin MT. Basic mechanisms for adverse cardiovascular events associated with air pollution. Heart. 2015;101:253–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee BJ, Kim B, Lee K. Air pollution exposure and cardiovascular disease. Toxicol Res. 2014;30:71–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kmietowicz Z. Health of 1.8 billion children is at serious risk from air pollution, says WHO. BMJ. 2018;363:k4580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Heath Organization (WHO) Report . Air pollution and child heath—prescribing clean air. 2018.

- 9. Hajat A, Hsia C, O'Neill MS. Socioeconomic disparities and air pollution exposure: a global review. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2015;2:440–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weagle CL, Snider G, Li C, van Donkelaar A, Philip S, Bissonnette P, Burke J, Jackson J, Latimer R, Stone E, et al. Global sources of fine particulate matter: interpretation of PM2.5 chemical composition observed by spartan using a global chemical transport model. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52:11670–11681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hadley MB, Baumgartner J, Vedanthan R. Developing a clinical approach to air pollution and cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2018;137:725–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Newby DE, Mannucci PM, Tell GS, Baccarelli AA, Brook RD, Donaldson K, Forastiere F, Franchini M, Franco OH, Graham I, et al. Expert position paper on air pollution and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:83–93b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Araujo JA. Particulate air pollution, systemic oxidative stress, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Air Qual Atmos Health. 2010;4:79–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Heath Organization Report . WHO report on air pollution. 2019.

- 15. World Heath Organization Report . Ambient air pollution: a global assessment of exposure and burden of disease. 2016.

- 16. Rees N, Wickham A, Choi YS. UNICEF Report. Silent Suffocation in Africa: Air Pollution is a Growing Menace, Affecting the Poorest Children the Most. 2019.

- 17. Cohen AJ, Brauer M, Burnett R, Anderson HR, Frostad J, Estep K, Balakrishnan K, Brunekreef B, Dandona L, Dandona R, et al. Estimates and 25‐year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the global burden of diseases study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389:1907–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Millman A, Tang D, Perera FP. Air pollution threatens the health of children in china. Pediatrics. 2008;122:620–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oyana TJ, Podila P, Relyea GE. Effects of childhood exposure to PM2.5 in a memphis pediatric asthma cohort. Environ Monit Assess. 2019;191:330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhu X, Liu Y, Chen Y, Yao C, Che Z, Cao J. Maternal exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and pregnancy outcomes: a meta‐analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2015;22:3383–3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lavigne E, Burnett RT, Stieb DM, Evans GJ, Godri Pollitt KJ, Chen H, van Rijswijk D, Weichenthal S. Fine particulate air pollution and adverse birth outcomes: effect modification by regional nonvolatile oxidative potential. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126:077012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lamichhane DK, Leem JH, Lee JY, Kim HC. A meta‐analysis of exposure to particulate matter and adverse birth outcomes. Environ Health Toxicol. 2015;30:e2015011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bruce NG, Dherani MK, Das JK, Balakrishnan K, Adair‐Rohani H, Bhutta ZA, Pope D. Control of household air pollution for child survival: estimates for intervention impacts. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(Suppl 3):S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hajat S, Armstrong B, Wilkinson P, Busby A, Dolk H. Outdoor air pollution and infant mortality: analysis of daily time‐series data in 10 english cities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:719–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lin CA, Pereira LA, Nishioka DC, Conceicao GM, Braga AL, Saldiva PH. Air pollution and neonatal deaths in sao paulo, brazil. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:765–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tielsch JM, Katz J, Thulasiraj RD, Coles CL, Sheeladevi S, Yanik EL, Rahmathullah L. Exposure to indoor biomass fuel and tobacco smoke and risk of adverse reproductive outcomes, mortality, respiratory morbidity and growth among newborn infants in South India. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1351–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glinianaia SV, Rankin J, Bell R, Pless‐Mulloli T, Howel D. Does particulate air pollution contribute to infant death? A systematic review Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1365–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khan MN, CZ BN, Mofizul Islam M, Islam MR, Rahman MM. Household air pollution from cooking and risk of adverse health and birth outcomes in bangladesh: a nationwide population‐based study. Environ Health. 2017;16:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neogi SB, Pandey S, Sharma J, Chokshi M, Chauhan M, Zodpey S, Paul VK. Association between household air pollution sand neonatal mortality: an analysis of annual health survey results, India. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2015;4:30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Davis NK. Babies exposed to air pollution have greater risk of death—study. The Guardian UK News Report. 2019. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/sep/26/babies-exposed-to-air-pollution-have-greater-risk-of-death-study. [Google Scholar]

- 31. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Heath, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general. 2014. [PubMed]

- 32. Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1731–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nilsson PM, Nilsson JA, Berglund G. Population‐attributable risk of coronary heart disease risk factors during long‐term follow‐up: the malmo preventive project. J Intern Med. 2006;260:134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Uzoigwe JC, Prum T, Bresnahan E, Garelnabi M. The emerging role of outdoor and indoor air pollution in cardiovascular disease. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:445–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Calo WA, Ortiz AP, Suarez E, Guzman M, Perez CM, Perez CM. Association of cigarette smoking and metabolic syndrome in a puerto rican adult population. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15:810–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gruzieva O, Xu CJ, Breton CV, Annesi‐Maesano I, Anto JM, Auffray C, Ballereau S, Bellander T, Bousquet J, Bustamante M, et al. Epigenome‐wide meta‐analysis of methylation in children related to prenatal NO2 air pollution exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:104–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee MK, Xu CJ, Carnes MU, Nichols CE, Ward JM, consortium B, Kwon SO, Kim SY, Kim WJ, London SJ. Genome‐wide DNA methylation and long‐term ambient air pollution exposure in Korean adults. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oh SW, Yoon YS, Lee ES, Kim WK, Park C, Lee S, Jeong EK, Yoo T, Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey . Association between cigarette smoking and metabolic syndrome: the Korea national health and nutrition examination survey. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2064–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang M, Mueller NT, Wang H, Hong X, Appel LJ, Wang X. Maternal exposure to ambient particulate matter </=2.5 microm during pregnancy and the risk for high blood pressure in childhood. Hypertension. 2018;72:194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang Z, Dong B, Li S, Chen G, Yang Z, Dong Y, Wang Z, Ma J, Guo Y. Exposure to ambient particulate matter air pollution, blood pressure and hypertension in children and adolescents: a national cross‐sectional study in China. Environ Int. 2019;128:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van Rossem L, Rifas‐Shiman SL, Melly SJ, Kloog I, Luttmann‐Gibson H, Zanobetti A, Coull BA, Schwartz JD, Mittleman MA, Oken E, et al. Prenatal air pollution exposure and newborn blood pressure. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:353–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pieters N, Koppen G, Van Poppel M, De Prins S, Cox B, Dons E, Nelen V, Panis LI, Plusquin M, Schoeters G, et al. Blood pressure and same‐day exposure to air pollution at school: associations with nano‐sized to coarse pm in children. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:737–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bilenko N, van Rossem L, Brunekreef B, Beelen R, Eeftens M, Hoek G, Houthuijs D, de Jongste JC, van Kempen E, Koppelman GH, et al. Traffic‐related air pollution and noise and children's blood pressure: results from the piama birth cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Curto A, Wellenius GA, Mila C, Sanchez M, Ranzani O, Marshall JD, Kulkarni B, Bhogadi S, Kinra S, Tonne C. Ambient particulate air pollution and blood pressure in peri‐urban India. Epidemiology. 2019;30:492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fedak KM, Good N, Walker ES, Balmes J, Brook RD, Clark ML, Cole‐Hunter T, Devlin R, L'Orange C, Luckasen G, et al. Acute effects on blood pressure following controlled exposure to cookstove air pollution in the stoves study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012246 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alderete TL, Song AY, Bastain T, Habre R, Toledo‐Corral CM, Salam MT, Lurmann F, Gilliland FD, Breton CV. Prenatal traffic‐related air pollution exposures, cord blood adipokines and infant weight. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13:348–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rundle AG, Gallagher D, Herbstman JB, Goldsmith J, Holmes D, Hassoun A, Oberfield S, Miller RL, Andrews H, Widen EM, et al. Prenatal exposure to airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and childhood growth trajectories from age 5‐14 years. Environ Res. 2019;177:108595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jerrett M, McConnell R, Chang CC, Wolch J, Reynolds K, Lurmann F, Gilliland F, Berhane K. Automobile traffic around the home and attained body mass index: a longitudinal cohort study of children aged 10‐18 years. Prev Med. 2010;50(suppl 1):S50–S58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jerrett M, McConnell R, Wolch J, Chang R, Lam C, Dunton G, Gilliland F, Lurmann F, Islam T, Berhane K. Traffic‐related air pollution and obesity formation in children: a longitudinal, multilevel analysis. Environ Health. 2014;13:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fleisch AF, Rifas‐Shiman SL, Koutrakis P, Schwartz JD, Kloog I, Melly S, Coull BA, Zanobetti A, Gillman MW, Gold DR, et al. Prenatal exposure to traffic pollution: associations with reduced fetal growth and rapid infant weight gain. Epidemiology. 2015;26:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang Y, Hollis‐Hansen K, Ren X, Qiu Y, Qu W. Do environmental pollutants increase obesity risk in humans? Obes Rev. 2016;17:1179–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Choe SA, Eliot MN, Savitz DA, Wellenius GA. Ambient air pollution during pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes in New York City. Environ Res. 2019;175:414–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Toledo‐Corral CM, Alderete TL, Habre R, Berhane K, Lurmann FW, Weigensberg MJ, Goran MI, Gilliland FD. Effects of air pollution exposure on glucose metabolism in los angeles minority children. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13:54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cai L, Wang S, Gao P, Shen X, Jalaludin B, Bloom MS, Wang Q, Bao J, Zeng X, Gui Z, et al. Effects of ambient particulate matter on fasting blood glucose among primary school children in Guangzhou, China. Environ Res. 2019;176:108541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hathout EH, Beeson WL, Nahab F, Rabadi A, Thomas W, Mace JW. Role of exposure to air pollutants in the development of type 1 diabetes before and after 5 yr of age. Pediatr Diabetes. 2002;3:184–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Thiering E, Cyrys J, Kratzsch J, Meisinger C, Hoffmann B, Berdel D, von Berg A, Koletzko S, Bauer CP, Heinrich J. Long‐term exposure to traffic‐related air pollution and insulin resistance in children: results from the giniplus and lisaplus birth cohorts. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1696–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]