Abstract

Background

Racial/ethnic minorities, especially non‐Hispanic blacks, in the United States are at higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease. However, less is known about the prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among ethnic sub‐populations of blacks such as African immigrants residing in the United States. This study's objective was to compare the prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among African immigrants and African Americans in the United States.

Methods and Results

We performed a cross‐sectional analysis of the 2010 to 2016 National Health Interview Surveys and included adults who were black and African‐born (African immigrants) and black and US‐born (African Americans). We compared the age‐standardized prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, overweight/obesity, hypercholesterolemia, physical inactivity, and current smoking by sex between African immigrants and African Americans using the 2010 census data as the standard. We included 29 094 participants (1345 African immigrants and 27 749 African Americans). In comparison with African Americans, African immigrants were more likely to be younger, educated, and employed but were less likely to be insured (P<0.05). African immigrants, regardless of sex, had lower age‐standardized hypertension (22% versus 32%), diabetes mellitus (7% versus 10%), overweight/obesity (61% versus 70%), high cholesterol (4% versus 5%), and current smoking (4% versus 19%) prevalence than African Americans.

Conclusions

The age‐standardized prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors was generally lower in African immigrants than African Americans, although both populations are highly heterogeneous. Data on blacks in the United States. should be disaggregated by ethnicity and country of origin to inform public health strategies to reduce health disparities.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease risk factors, ethnicity, hypertension, immigration and emigration, obesity

Subject Categories: Race and Ethnicity; Risk Factors; Cardiovascular Disease; Obesity; Diabetes, Type 2

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

This study compares cardiovascular disease risk factor prevalence between African immigrant and African American adults in the United States.

The age‐standardized prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors were significantly lower among African immigrants compared with African Americans.

African immigrants were more likely to be younger, educated, and employed but were less likely to be insured than African Americans.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Because of current trends in migration, healthcare providers should be aware of the ethnic diversity of the black population in the United States.

Healthcare providers should consider the impact of birthplace, socioeconomic status, healthcare access, and cultural differences on the prevention and management of cardiovascular conditions.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the United States and worldwide. Nearly 30% of all US deaths are attributed to CVD.1 Approximately 40% of the US population will have some form of CVD by 2030.2 Direct and indirect CVD‐ and stroke‐related medical costs are expected to increase to nearly $918 billion by 2030 from $317 billion in 2013.1

Racial/ethnic minorities in the United States are at higher risk of developing CVD.3 Particularly, non‐Hispanic black adults, hereafter called blacks, bear a disproportionate burden of CVD risk factors compared with non‐Hispanic white adults1, 4 Although the CVD prevalence in blacks has been relatively well‐examined, less is known about ethnic sub‐populations of blacks such as African immigrants residing in the United States. The African immigrant population, one of the fastest growing immigrant groups in the United States, has doubled since 1970, to an estimated 2.1 million in 2015.5 Despite their increasing presence, African immigrants are still understudied and data on African immigrants are traditionally aggregated with their African American or foreign‐born black counterparts.6 Previous research has shown that even though African immigrants are generally more educated than US‐born people and other immigrants,7 African immigrants tend to have worse cardiometabolic health profiles than their African American counterparts.8, 9 However, data on this phenomenon are conflicting. In some studies, African immigrant men were more likely to have prediabetes (evidenced by abnormal glucose tolerance) or diabetes mellitus than African American men.8, 9 However, in other studies, African immigrants had lower odds of obesity10 and a lower prevalence of diabetes mellitus11 than their US‐born African American counterparts. Other studies comparing CVD risk factors in foreign‐ and US‐born blacks have observed higher odds of diabetes mellitus, lower odds of obesity12 and lower odds of hypertension13 in foreign‐born blacks. These studies, however, failed to disaggregate the data on the different foreign‐born black ethnicities. Thus, the results cannot be attributed to African immigrants.

Studies on the prevalence of CVD risk factors among African immigrants have examined African immigrants based on their geographical location.14, 15 However, limited epidemiological data exist on the prevalence of CVD risk factors among African immigrants using nationally representative data sets.6 An in‐depth examination of the prevalence of CVD risk factors among African immigrants may inform culturally targeted public health interventions. Additionally, it is unclear how the prevalence of CVD risk factors in African immigrants compares to that of African Americans. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate ethnic differences in the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, overweight/obesity, hypercholesterolemia physical inactivity, and current smoking among African immigrants and African Americans. Among African immigrants, we examined the prevalence of the CVD risk factors by length of US residence. We also compared the prevalence of the CVD risk factors between African immigrants with a longer length of US residence and African Americans. We hypothesized that using a nationally representative data source, there would be a significantly lower prevalence of CVD risk factors among African immigrants compared with African Americans. We hypothesized a lower prevalence of CVD risk factors in African immigrants because prior literature comparing foreign‐ and US‐born people has shown a health advantage in the foreign‐born people.16, 17, 18 We also hypothesized that African immigrants who had a longer length of US residence (≥10 years) will have a higher prevalence of CVD risk factors compared with those with a shorter length of US residence (<10 years) and that the prevalence of CVD risk factors among African immigrants with a longer length of US residence would be similar to that of African Americans. This is to determine whether the healthy immigrant effect exists in this population. The “healthy immigrant effect” is the phenomenon where immigrants are healthier than their native‐born counterparts on arrival or shortly after migrating,19 however, with increasing length of residence in their new country, the immigrants’ health profile worsens and resembles that of the native‐born people in their new country.20

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

The data used in this study are publicly available from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) website.21 Statistical code for the results can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The NHIS, which is administered by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), is a cross‐sectional, nationally representative study of civilian non‐institutionalized US adults who are ≥18 years.22 The NHIS uses a complex multistage probability design including clustering, stratification, and differentiation with an oversampling of blacks (primarily African Americans), Hispanics, and Asians. However, the sampling weights used for the analyses do not account for the ethnic and nativity differences among blacks. Thus, the probability of selection may differ between African immigrants and African Americans because recruitment strategies were not targeted toward immigrants, leading to underrepresentation in African immigrants.

Approximately 45 000 households and about 110 000 people are interviewed annually.23 Information on sociodemographic characteristics, health indicators, and healthcare use are obtained via face‐to‐face interviews in English and Spanish. One adult per household is randomly selected to complete the Sample Adult Module and provide detailed information on health status, use of healthcare services, and health behavior.22 A detailed description of the design and methodology of the NHIS is published elsewhere.22, 23

The Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics (current protocol #2018‐01) and the US Office of Management and Budget (current control 0920‐0214) support the conduct of the NHIS by maintaining its approval. Oral informed consent was given by all participants before their participation. This study was exempted from institutional review board review because it used deidentified data available in the public domain published by the NCHS.

Participants

All people who self‐identified as black and born in Africa were considered African immigrants. These included respondents who were naturalized citizens, legal permanent residents, refugees, undocumented immigrants, and those on visas, including students or guest workers. Specific information on countries of origin was not used for analysis; this is protected data and not publicly available.22 People who self‐identified as black and born in the United States were considered African Americans. People who self‐identified as black and born in the Caribbean or Europe were not included in this study.

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest were self‐reported hypertension, diabetes mellitus, overweight/ obesity, hypercholesterolemia, physical inactivity, and current smoking status. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hypercholesterolemia were defined by the respondents’ response to the dichotomized question posed as follows: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or healthcare professional that you had:” “hypertension, also called high blood pressure?” “diabetes, or sugar diabetes?” or “high cholesterol?” For those with an affirmative response to diabetes mellitus, the diabetes mellitus outcome was restricted to type 2. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using respondents’ self‐reported height and weight, without shoes. The BMI categories used to define overweight/obesity were based on the National Institutes of Health cut‐offs. Based on these classifications, BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2 is classified as normal weight, and BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 kg/m2, and >30 kg/m2 are considered overweight and obese, respectively.1 The overweight and obese BMI categories were combined into one category, and BMI was analyzed as a dichotomous outcome (overweight/obese versus normal weight). People in the total sample who were underweight (1%; 2% African immigrant, 1% African American), were excluded from the analysis. Current smoking was defined as an affirmative response to the question: “Do you now smoke cigarettes every day, some days, or none at all?” among people who assented to having “ever smoked at least 100 cigarettes in [their] entire life.” Physical activity was defined based on participants’ responses to questions inquiring how often and how long during their leisure time they engaged in at least 10 minutes of vigorous‐intensity activities or light‐to‐moderate activities. Participants were classified as physically inactive if they reported engaging in no physical activity or <150 minutes a week of light‐to‐moderate physical activity and <75 minutes a week of vigorous physical activity or an equivalent combination of the 2. Using the 2008 adult physical activity guidelines which were in effect during data collection, when obtaining the equivalent amount of moderate and vigorous intensity physical activity, vigorous intensity activity in minutes accounted for twice the estimate of minutes of moderate intensity physical activity.24

Covariates

We examined the following variables as covariates: age in years (continuous), sex (male/female), marital status (married/cohabitating or not currently married/cohabitating), employment status (employed/not employed), insurance status (with/without health insurance), educational status (high school and below, college, and graduate school), a usual place to go for health care when sick (yes/no), length of US residence for African immigrants (<10 years and ≥10 years), and Poverty Income Ratio (PIR) as a proxy for income status. The PIR, defined as the ratio of income to poverty, was obtained by dividing the midpoint of an individual's family income by the poverty threshold for that respective year.25 The PIR was categorized into poor (PIR <1), near poor (PIR 1 to 2), and not poor/near poor (PIR >2). A PIR of <1 means that a person is <100% below the federal poverty level/threshold.

Statistical Analysis

Taking into consideration the complex survey design, sample weights, and sampling design parameters, we pooled data from the NHIS surveys for the years 2010 to 2016 to improve the reliability of our estimates. Using the NCHS guidelines for combining NHIS data, the Sample Adult and Person‐Level files for each of the years were merged and sampling weights adjusted to account for pooling the data.26 We considered 2013 the midpoint of the 2010 to 2016 period, consistent with NCHS recommendations.27

Participants with missing data on all outcomes (n=15) and those who had a history of stroke (n=7535) or coronary heart disease (n=11 966) were excluded from analysis. Characteristics of the sample were summarized using weighted descriptive statistics; design‐adjusted chi‐square and t tests were used to test for differences in categorical and continuous sociodemographic factors, respectively, between African immigrants and African Americans.

We considered multiple potential confounders of the relationship between African‐descent ethnic group status (African American versus African immigrant) and the CVD risk factors, which included age, sex, marital, employment, insurance, educational, and income status as well as a usual place to go for health care when sick. These variables are well‐established in the literature.1, 28, 29 We used generalized linear models with a Poisson distribution and a logarithmic link with linearized variance estimation and controlled for these confounders in the fully adjusted models. We determined the best model using backward model selection with exclusion at the 0.05 level for all 6 outcomes. The best model was the fully adjusted model. This was confirmed using the best subset selection approach using the lowest Akaike Information Criterion as the criterion for model selection. The results of the age‐adjusted and fully adjusted generalized linear models are found in Table S1. The age distribution among the participants differed by African‐descent ethnic group; we therefore used age‐standardization to account for this difference in further analyses.

We examined potential effect measure modifiers of the relationship between African‐descent ethnic group and the CVD risk factor prevalence in 2 ways. We included the interaction term consisting of the product of African‐descent ethnic group with age in one model, and the product of African‐descent ethnic group and sex in another model. Since the interaction terms were non‐significant, we did not present stratified results.

For age‐standardization, we used the direct method of standardization with the 2010 US population, with the age groups of 18 to 25, 25 to 44, 45 to 64, 65 to 74, and ≥75 years as the standard,30 using estimates obtained by the US Census Bureau. Per NCHS guidelines,31 we used the Stata command: svy: mean with the options stdize and stdweight, to obtain estimates of the age‐standardized prevalence with standard errors of the self‐reported outcomes of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, overweight/obesity, hypercholesterolemia, physical inactivity, and current smoking by African‐descent ethnic group. To compare the prevalence of the self‐reported CVD risk factors between African immigrants and African Americans, we used the non‐linear combination post‐estimation command nlcom, to estimate the age‐standardized prevalence ratios with their 95% CI by African‐descent ethnic group and sex.

To test the “healthy immigrant effect” hypothesis that African immigrants with ≥10 years of residence have a similar burden of CVD risk factors as African Americans, we stratified African immigrants into <10 versus ≥10 years of US residence and compared the age‐standardized prevalence of CVD risk factors with prevalence ratios of African immigrants with ≥10 years of US residence to that of African Americans. The svy subpop option in Stata was used to restrict the analyses to the African immigrant subgroup. We did not fit an interaction term in the model for the association between African‐descent ethnic group and CVD risk factors because length of residence only applies to African immigrants. Results were considered statistically significant at a 2‐sided alpha (α) level of ≤0.05. Data analyses were performed with Stata 14 IC (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

We included all NHIS participants (N=29 094) who were African immigrants (n=1345) or African Americans (n=27 749). Table 1 provides details of the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Almost 60% of African Americans were women compared with 46% of African immigrants. Sociodemographic differences by sex and African‐descent ethnic group are described in Table S2. African immigrants had a mean (±SE) age of 39 (±0.4) years and were on average 6 years younger than African Americans. African immigrants (44%) were more likely to be married than African Americans (24%; P<0.001). Although African immigrants were significantly more likely to have a bachelor's degree or higher (39% versus 20%; P<0.001) and be employed (73% versus 57%; P<0.001) compared with African Americans, there was no difference in poverty status between the 2 groups. African immigrants were less likely than African Americans to have health insurance (72% versus 82%; P<0.001) and to have a usual place to go when sick (72% versus 85%; P<0.001). Among African immigrants, 58% had lived in the United States for ≥10 years.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of African Immigrants and African Americans in the 2010 to 2016 National Health Interview Surveysa

| Characteristics (%) | Total | African American | African Immigrant | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted n | 11 359 578 | 10 821 022 | 538 556 | |

| Unweighted n | 29 094 | 27 749 | 1345 | |

| Age, y, mean (±SE) | 45.8 (±19.0) | 44.6 (±0.2) | 38.9 (±0.4) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 59.3 | 59.9 | 46.2 | <0.001 |

| Men | 40.7 | 40.1 | 53.8 | |

| Married | ||||

| Not married | 75.5 | 76.4 | 56.3 | <0.001 |

| Currently married | 24.5 | 23.6 | 43.7 | |

| Education | ||||

| ≤High school graduate | 44.4 | 45.2 | 28.8 | <0.001 |

| Some college | 35.0 | 35.1 | 32.1 | |

| ≥Bachelor's degree | 20.6 | 19.7 | 39.1 | |

| Poverty category | ||||

| Poor (PIR <1) | 22.5 | 22.5 | 21.8 | 0.880.88 |

| Near poor (PIR 1–2) | 19.4 | 19.4 | 19.6 | |

| Not poor/Near poor (PIR >2) | 58.1 | 58.1 | 58.6 | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 42.3 | 43.1 | 27.5 | <0.001 |

| Employed | 57.7 | 56.9 | 72.6 | |

| Health insurance status | ||||

| Not covered | 17.5 | 17.0 | 27.2 | <0.001 |

| Covered | 81.9 | 82.4 | 71.7 | |

| Don't know | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | |

| Have a usual place to go when sick | ||||

| Do not have a usual place | 15.7 | 15.1 | 28.5 | <0.001 |

| Have a usual place | 84.3 | 84.9 | 71.6 | |

| Length of US residence | ||||

| <10 y | … | … | 42.0 | |

| ≥10 y | … | … | 58.1 | |

PIR indicates poverty‐income ratio.

Weighted sample sociodemographic characteristics presented.

Prevalence of CVD Risk Factors

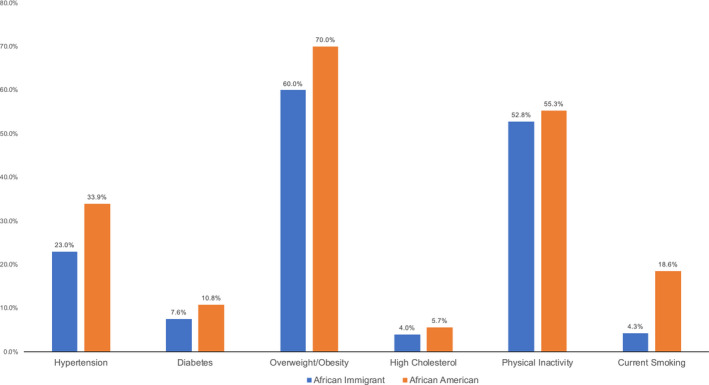

Overall, the prevalence of CVD risk factors was lower in African immigrants compared with African Americans (Figure). The prevalence of the CVD risk factors by sex and African‐descent ethnic group are shown in Figure S1. African immigrants had significantly lower prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, overweight/obesity, hypercholesterolemia, and current smoking compared with African Americans (Table 2). The age‐standardized prevalence of hypertension in African immigrants was 22% compared with 32% in African Americans (P<0.01). The age‐standardized diabetes mellitus prevalence in African immigrants was 7%; in African Americans, it was higher at 10% (P<0.01). The overweight/obesity prevalence in African immigrants was 61%; African Americans had a significantly higher prevalence at 70% (P<0.01). The high cholesterol prevalence was higher in African Americans (5%) compared with African immigrants (4%) (P<0.01). African Americans were ≈5 times more likely to be current smokers compared with African immigrants (19% versus 4%; P<0.01). However, there was no significant difference in physical inactivity levels between African immigrants (53%) and African Americans (55%).

Figure 1.

Age‐standardized prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors.

Table 2.

Age‐Standardized Prevalence and Prevalence Ratios of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in African Immigrants and African Americans by Sex

| Risk Factors | Men | Women | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Immigrants | African Americans | African Immigrants | African Americans | African Immigrants | African Americans | |||||

| Prev% (SE) | PR (95% CI) | Prev% (SE) | PR (95% CI) | Prev% (SE) | PR (95% CI) | Prev% (SE) | PR (95% CI) | Prev% (SE) | Prev% (SE) | |

| Hypertension | 22.6 (1.7) | 0.74 (0.63–0.85)a | 30.5 (0.5) | Ref | 21.9 (1.7) | 0.65 (0.55–0.75)a | 33.4 (0.4) | Ref | 22.1 (1.2)a | 32.3 (3.1)a |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8.3 (2.0) | 0.86 (0.44–1.28) | 9.6 (0.3) | Ref | 5.4 (1.2) | 0.56 (0.33–0.80)a | 9.5 (0.2) | Ref | 6.6 (1.1)a | 9.5 (1.7)a |

| Overweight/Obesity | 61.9 (3.3) | 0.93 (0.83–1.02) | 66.7 (0.6) | Ref | 58.9 (2.7) | 0.82 (0.74–0.89)a | 71.9 (0.5) | Ref | 60.7 (2.2)a | 69.8 (0.4)a |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 3.5 (0.7) | 0.64 (0.36–0.91)a | 5.4 (0.3) | Ref | 4.3 (1.1) | 0.84 (0.42–1.25) | 5.2 (0.2) | Ref | 3.7 (0.6)a | 5.3 (1.7)a |

| Physical inactivity | 45.5 (3.5) | 0.99 (0.84–1.15) | 45.7 (0.7) | Ref | 60.2 (2.6) | 0.97 (0.89–1.06) | 61.8 (0.6) | Ref | 52.3 (2.2) | 55.3 (5.1) |

| Current smoking | 6.2 (0.8) | 0.27 (0.20–0.34)a | 23.2 (0.6) | Ref | 1.8 (1.2) | 0.12 (−0.04–0.28)a | 16.6 (0.4) | Ref | 4.3 (0.8)a | 18.6 (0.3)a |

Results are weighted. PR indicates prevalence ratio; Prev, prevalence; Ref, Reference.

Statistically significant, P<0.05.

Differences in the prevalence of the CVD risk factors were also observed when stratified by sex. (Table 2). African immigrant women were less likely to report having hypertension (prevalence ratio [PR] 0.65; 95% CI: 0.55–0.75), diabetes mellitus (PR: 0.56; 95% CI: 0.33–0.80), overweight/obesity (PR: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.74–0.89), or current smoking (PR: 0.12; 95% CI: −0.04–0.28) compared with African American women. African immigrant men were less likely than their African American counterparts to have hypertension (PR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.63–0.85), hypercholesterolemia (PR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.36–0.91), or be current smokers (PR: 0.27; 95% CI; 0.20–0.34). African American women had a higher prevalence of overweight/obesity and physical inactivity compared with African American men, these were both higher than the prevalence in African immigrant men and women. African immigrants were much less likely to be current smokers than African Americans.

CVD Risk Factor Prevalence by Length of Residence among African Immigrants

Among African immigrants, we examined CVD risk factors by length of US residence. There were no significant differences in the age‐standardized prevalence of the CVD risk factors by length of residence. (Table 3). Furthermore, African immigrants who had lived in the United States ≥10 years were significantly less likely to have hypertension (PR:0.69; 95% CI: 0.61–0.78), diabetes mellitus (PR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.43–0.79), overweight/obesity (PR: 0.87; 95% CI: 0.77–0.96), and to be physically inactive (PR: 0.21; 95% CI: 0.15–0.28) than African Americans. (Table 3).

Table 3.

Age‐Standardized Prevalence and Prevalence Ratios of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in African Immigrants and African Americans by Length of US Residence

| African Immigrants | African Americans | African Immigrants With ≥10 y vs African Americans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10 y US Residence | ≥10 y US Residence | |||||

| Risk Factors | Prevalence % (SE) | PR (95% CI) | Prevalence % (SE) | PR (95% CI) | Prevalence % (SE) | PR (95% CI)a |

| Hypertension | 19.5 (2.1) | Ref | 22.4 (1.4) | 1.15 (0.88–1.42) | 32.3 (0.3) | 0.69 (0.61–0.78)b |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6.9 (2.3) | Ref | 5.8 (0.9) | 0.84 (0.26–1.42) | 9.5 (0.2) | 0.61 (0.43–0.79)b |

| Overweight/obesity | 60.3 (3.5) | Ref | 60.3 (3.4) | 1.00 (0.84–1.16) | 69.8 (0.4) | 0.87 (0.77–0.96)b |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 2.6 (1.2) | Ref | 4.2 (0.8) | 1.60 (0.07–3.13) | 5.3 (0.2) | 0.81 (0.50–1.11) |

| Physical inactivity | 56.7 (3.0) | Ref | 51.9 (3.9) | 0.91 (0.75–1.08) | 55.3 (0.5) | 0.21 (0.15–0.28)b |

| Current smoking | 4.3 (1.5) | Ref | 4.0 (0.6) | 0.92 (0.22–1.62) | 18. 6 (3.5) | 0.94 (0.80–1.08) |

Results are weighted. PR indicates prevalence ratio; Prev, prevalence; Ref, reference.

African Americans are reference group for comparison.

Statistically significant.

Discussion

We sought to understand ethnic differences in the prevalence of CVD risk factors among African Americans and African immigrants. We found that the prevalence of CVD risk factors in African immigrants was generally lower in comparison with African Americans.

The overall age‐standardized hypertension prevalence in African Americans was much higher than both the prevalence in African immigrants in this study and all Americans in the NHIS in 2013 (24%; midpoint year of our analyses).32 The age‐standardized hypertension prevalence (22%) in African immigrants in this study is considerably higher than that of African immigrants (n=996) in the New Americans Community Services (NACS) Study in Minnesota (8%).14 The NACS study surveyed participants from 18 African countries which they clustered into 6 groups, two thirds of whom were from East Africa, obtaining information on self‐reported CVD risk factors.14 The lower prevalence in the NACS study may be explained by the inclusion of participants from only 6 African groups and differences in sampling strategies between the NACS study and the NHIS. The hypertension prevalence in this study was also much lower than the 40% reported in the Afro‐Cardiac Study,15 which sampled 256 African immigrants from only Ghana and Nigeria and obtained blood pressure measurements.

We expected differences in hypertension prevalence because both groups have unique cultural backgrounds, values, and lifestyle although they are considered “blacks.” The lower prevalence among African immigrants may be attributed to positive selection processes which allow healthier and more educated individuals to migrate to the United States.33, 34 Level of education is often considered a proxy for socioeconomic status and is associated with healthier lifestyle choices.35 Although African immigrants were more likely to have a bachelor's degree or higher than African Americans, there was no difference in poverty status between the 2 groups. This finding supports the argument that education may not be a reliable proxy for socioeconomic status among African immigrants in the United States.

The overall age‐standardized prevalence of self‐reported diabetes mellitus in African Americans was higher than the prevalence among African immigrants. The diabetes mellitus prevalence observed among African immigrants in this study (6.6%) was higher than the 5.4% prevalence reported in the NACS study.14 The total diabetes mellitus prevalence among African immigrants in the Afro‐Cardiac study was 13%,15 which is both higher than the overall diabetes mellitus prevalence in our sample of African immigrants and African Americans (9.5%). Notably, diabetes mellitus status in the Afro‐Cardiac study15 was ascertained with fasting blood glucose samples and not with self‐report. The lower prevalence among African immigrants, compared with African Americans could be because of the lower level of healthcare use,36 resulting in lower diabetes mellitus detection, compared with their US‐born counterparts.37 Similar findings about the lack of insurance and a usual place to go when sick were observed among approximately a third of African immigrants in this study. Lower healthcare use may result in delayed diabetes mellitus diagnosis and treatment, which may lead to higher morbidity and mortality in this population.

The prevalence of overweight/obesity among all blacks (69%) in the 2013 NHIS was higher than the prevalence among African immigrants (60%) but similar to that of African Americans (70%) in this study. This suggests that aggregating data on blacks may mask ethnic differences in CVD risk. In African immigrants in the NACS study, the prevalence of overweight/obesity (55%) was lower than what we observed among African immigrants in this study. In contrast, the overall prevalence of overweight/obesity (88%) in African immigrants in the Afro‐Cardiac study was considerably higher than that observed in our study. Notably, weight was measured and not self‐reported in the Afro‐Cardiac study. The lower overweight/obesity prevalence in the African immigrant population may be partly explained by differences that may occur in their lifestyle or environment such as having healthier dietary patterns or living in enclaves, as has been observed among Hispanic and Asian immigrants.38, 39

Limited studies have been published on the prevalence of self‐reported high cholesterol using NHIS data. However, in the 2011 to 2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, where cholesterol was assessed by venipuncture, the prevalence of high total cholesterol in US blacks was 9%.40 This prevalence is higher than what we observed in this study in both African immigrants and African Americans. The prevalence of high cholesterol observed in the sample of African immigrants in this study was similar to the 5% observed in an earlier analysis of US African immigrants adults in the NHIS between 2010 to 2014.28 However, in African immigrants in the Afro‐Cardiac study, where high cholesterol (total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dL]) was assessed via finger‐stick, the prevalence of high cholesterol was higher at 27%.15 It is likely that the prevalence of high cholesterol is underestimated in this NHIS study because assessment of lipid profile often requires access to health care.41

In 2013, the prevalence of smoking in blacks in the NHIS was 18.3%;42 this estimate is similar to the prevalence observed in African Americans in this study and higher than that of African immigrants in this study. The prevalence of current smokers among African immigrants is typically low; among African immigrants in the NACS study, 8.3% were current smokers.14 This is higher than what we observed in our study. In contrast, only 1 participant (0.4%) out of the sample of 253 African immigrants in the Afro‐Cardiac study reported being a current smoker. In 1 study examining African immigrants and African Americans, the proportion of African Americans (21%) who were current smokers was 3.5 times that of African immigrants (6%).43 This observation is similar to the findings in this study where African immigrants were significantly less likely to be current smokers compared with African Americans. Other studies examining smoking in African immigrants have also found similar relationships.44, 45 These findings of lower smoking prevalence among African immigrants may be suggestive of cultural influences which might regard smoking unfavorably.

In 2013, the prevalence of physical inactivity among blacks in the NHIS was 58.6%.46 This figure is slightly higher than the prevalence among African immigrants (52.8%) and African Americans (55.3%) in this study. Among African immigrants, 72% in the NACS Study reported being physically inactive14 and 44% in the Afro‐Cardiac study stated they were physically inactive. Similar, to this study, another study found a non‐significant difference in physical inactivity between African Americans and African immigrants.43

Among African immigrants, we examined the prevalence of the CVD risk factors by length of stay. We had anticipated observing a higher prevalence of CVD risk factors in African immigrants with longer length of US residence, suggesting evidence of the healthy immigrant effect.19 However, we observed no significant differences in prevalence of the CVD risk factors by length of stay which does not support the “healthy immigrant effect.” There were also no sex differences by length of US residence among the African immigrants.

Additionally, the prevalence of the CVD risk factors among African immigrants with ≥10 years of residence was lower than that of African Americans, which contradicts the “healthy immigrant effect” hypothesis. This finding may reflect cardioprotective health behaviors that African immigrants engage in with longer length of US residence or with healthy acculturation. Indeed, African immigrants with ≥10 years of residence were more physically active than African Americans which suggests that with longer length of stay, African immigrants may adopt healthier lifestyles.

Future studies that consider sex differences while examining cardiometabolic health profiles among subpopulations of people of African descent may provide additional insights about high‐risk groups. Additionally, future studies should prospectively examine changes in CVD risk among diverse African‐descent ethnic groups to further elucidate the mechanisms contributing to health disparities among blacks. Additionally, future research should examine what, if any, is the impact of the differential uptake of smoking in these African‐descent ethnic groups on the development of subclinical and overt CVD risk factors. Future studies should also further examine the role of sex in CVD‐related interventions among African immigrants and African Americans.

This study has some limitations that are worth considering. First, people in the United States who identify as African American or black and born in the United States are not a homogeneous group. These people of African descent may also identify as Afro Caribbean, Hispanic, Latino, or may be second or third generation African immigrants. They may also include people who may be admixed with other races/ethnicities.47 We were not able to make these distinctions in this study, and results may not be applicable to these groups. Second, we relied on self‐report of diagnosis of CVD risk factors and not clinical markers to ascertain the study outcomes which could have resulted in social desirability or healthcare access bias and led to an underestimation of the true prevalence of the CVD risk factors among study participants. Third, we could not compare the prevalence of CVD risk factors among African immigrants between population‐based studies such as National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey which uses clinical markers versus those that use self‐report such as the NHIS because National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey does not report on the country of birth for foreign‐born people.

Fourth, relative to the number of African Americans, there were fewer African immigrants in this study. Hence, the burden of CVD risk factors may not be accurately reflected in our sample of African immigrants. The NHIS does not purposely sample for African immigrants, thus, participants may not be representative of the larger African immigrant population in the United States. Since country of origin is not provided in the publicly available data set, we could not factor this variable into our analysis. The proportion of African immigrants in this study (5%), however, is similar to the estimated proportion of black immigrants from Africa in the United States, also 4%.48 Fifth, African immigrants who were not English or Spanish speaking were likely unable to participate in the NHIS. This is especially relevant for African immigrants from Francophone and Lusophone countries. Last, since this is a cross‐sectional study, no causal inferences can be made on when these CVD risk factors were acquired.

This study has some notable strengths. It is one of the largest studies to‐date comparing the prevalence of CVD risk factors among African immigrants and African Americans using a random sample. Because of the complex sampling strategy and national representation of the NHIS, the present study likely included a greater diversity of African immigrants with respect to their country of origin than observed in studies which have used non‐probability sampling such as the NACS14 and the Afro‐Cardiac15 studies. Our study uses a publicly available data set to address some of the limitations of previous research, providing novel insights on the CVD risk profiles of African immigrants in the United States.

Conclusions

Although both populations are highly heterogeneous, the burden of CVD risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, overweight/obesity, high cholesterol, and current smoking) was lower in African immigrants compared with African Americans in the 2010 to 2016 NHIS. Our findings provide further evidence in support of prior calls to disaggregate data on African descent populations by ethnicity and country of origin.6 Doing so will enhance the understanding of protective factors in African ancestry populations, which may reduce health disparities observed among blacks. This strategy will ultimately help inform the development of culturally‐relevant public health strategies to reduce health disparities.

Sources of Funding

Dr Turkson‐Ocran is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32DK062707 and an award from the American Heart Association. Dr Szanton is supported by a National Institute on Aging grant (R01AG056607). Dr Golden is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (U01DK048485). Dr Cooper is supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute (UH3HL130688). Dr Commodore‐Mensah is supported by the Johns Hopkins Institute of Clinical and Translational Research through a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number: 5KL2TR001077‐05.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Prevalence and Prevalence Ratios of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in African Immigrants and African Americans by Sex

Table S2. Sociodemographic Characteristics of African Immigrants and African Americans in the 2010 to 2016 National Health Interview Surveys by Sex*

Figure S1. Age‐Standardized Prevalence of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in African Americans and African Immigrants by Sex.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Jonathan Aboagye, MD, MPH (Howard University Hospital Department of Surgery, Washington DC) and Christopher Dodoo, MS (Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso) for their feedback on the data analysis process.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e013220 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013220.)

References

- 1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O'Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P. Heart disease and stroke statistics‐2018 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, Butler J, Dracup K, Ezekowitz MD, Finkelstein EA, Hong Y, Johnston SC, Khera A. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States. Circulation. 2011;123:933–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gillespie CD, Hurvitz KA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of hypertension and controlled hypertension—United States, 2007–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:144–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Appelman Y, van Rijn BB, Ten Haaf ME, Boersma E, Peters SAE. Sex differences in cardiovascular risk factors and disease prevention. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. United States Census Bureau . African‐born population in U.S. Roughly doubled every decade since 1970, census bureau reports. 2014.

- 6. Commodore‐Mensah Y, Himmelfarb CD, Agyemang C, Sumner AE. Cardiometabolic health in African immigrants to the United States: a call to re‐examine research on African‐descent populations. Ethn Dis. 2015;25(373–380):378p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. New American Economy . Power of the purse: How sub‐saharan Africans contribute to the U.S. Economy. 2018.

- 8. O'Connor MY, Thoreson CK, Ricks M, Courville AB, Thomas F, Yao J, Katzmarzyk PT, Sumner AE. Worse cardiometabolic health in African immigrant men than African American men: reconsideration of the healthy immigrant effect. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2014;12:347–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ukegbu UJ, Castillo DC, Knight MG, Ricks M, Miller BV III, Onumah BM, Sumner AE. Metabolic syndrome does not detect metabolic risk in African men living in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2297–2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mehta NK, Elo IT, Ford ND, Siegel KR. Obesity among U.S.‐ and foreign‐born blacks by region of birth. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:269–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ford ND, Narayan KMV, Mehta NK. Diabetes among US‐ and foreign‐born blacks in the USA. Ethnicity & Health. 2016;21:71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Horlyck‐Romanovsky MF, Wyka K, Echeverria SE, Leung MM, Fuster M, Huang TT‐K. Foreign‐born blacks experience lower odds of obesity but higher odds of diabetes than US‐born blacks in New York City. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown AGM, Houser RF, Mattei J, Mozaffarian D, Lichtenstein AH, Folta SC. Hypertension among US‐born and foreign‐born non‐hispanic blacks: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003‐2014 data. J Hypertens. 2017;35:2380–2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sewali B, Harcourt N, Everson‐Rose SA, Leduc RE, Osman S, Allen ML, Okuyemi KS. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors across six African immigrant groups in minnesota. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Commodore‐Mensah Y, Hill M, Allen J, Cooper LA, Blumenthal R, Agyemang C, Himmelfarb CD. Sex differences in cardiovascular disease risk of Ghanaian‐ and Nigerian‐born west African immigrants in the United States: the Afro‐Cardiac study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002385 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singh GK, Siahpush M. All‐cause and cause‐specific mortality of immigrants and native born in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:392–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Singh GK, Miller BA. Health, life expectancy, and mortality patterns among immigrant populations in the United States. Can J Public Health. 2004;95:I14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Uretsky MC, Mathiesen SG. The effects of years lived in the United States on the general health status of california's foreign‐born populations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007;9:125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kennedy S, McDonald JT, Biddle N. The healthy immigrant effect and immigrant selection: evidence from four countries. 2006.

- 20. Antecol H, Bedard K. Unhealthy assimilation: why do immigrants converge to American health status levels? Demography. 2006;43:337–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Center for Health Statistics . NHIS data, questionnaires and related documentation. 2019.

- 22. Parsons VL, Moriarity C, Jonas K, Moore TF, Davis KE, Tompkins L. Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 2006–2015. Vital Health Stat 2. 2014;165:1–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) public use data release: NHIS survey description. 2013.

- 24. Committee PAGA . Physical activity guidelines advisory committee report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008;A1‐H14. [Google Scholar]

- 25. United States Census Bureau . Selected population profile in the united states: 2014 American community survey 1‐year estimates. 2014.

- 26. National Center for Health Statistics . Variance estimation and other analytic issues, NHIS 2006–2012. 2013.

- 27. National Health Interview Survey . Variance estimation guidance, NHIS 2006–2015. 2016.

- 28. Commodore‐Mensah Y, Ukonu N, Obisesan O, Aboagye JK, Agyemang C, Reilly CM, Dunbar SB, Okosun IS. Length of residence in the United States is associated with a higher prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in immigrants: a contemporary analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016. 5:e004059 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Commodore‐Mensah Y, Matthie N, Wells JB, Dunbar S, Himmelfarb CD, Cooper LA, Chandler RD. African Americans, African immigrants, and Afro‐Caribbeans differ in social determinants of hypertension and diabetes: evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2018;5:995–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Wen XJ, Gotway CA. Age adjustment of diabetes prevalence: use of 2010 U.S. Census data. J Diabetes. 2014;6:451–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Centers for Disease Control Prevention . NHANES tutorials ‐ module 7 ‐ age standardization and population estimates. 2018.

- 32. National Center for Health Statistics . Summary health statistics: National Health Interview Survey, 2013. 2013;2018.

- 33. Zong J, Batalova J. Sub‐saharan African immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. 2017;2018.

- 34. Anderson M, Connor P. Sub‐saharan African immigrants in the U.S. Are often more educated than those in top. European destinations. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35. National Center for Health Statistics . Health, United States, 2017: With special feature on mortality. 2018. [PubMed]

- 36. Ku L, Matani S. Left out: immigrants’ access to health care and insurance. Health Aff. 2001;20:247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dey A, Lucas J. Physical and mental health characteristics of U.S. and foreign‐born adults: United States, 1998–2003. 2006. [PubMed]

- 38. Osypuk TL, Roux AVD, Hadley C, Kandula N. Are immigrant enclaves healthy places to live? The multi‐ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Social science & medicine (1982). 2009;2009:110–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wen M, Maloney TN. Latino residential isolation and the risk of obesity in Utah: the role of neighborhood socioeconomic, built‐environmental, and subcultural context. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13:1134–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Kit BK. Total and high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol in adults: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Alcalá HE, Albert SL, Roby DH, Beckerman J, Champagne P, Brookmeyer R, Prelip ML, Glik DC, Inkelas M, Garcia R‐E, Ortega AN. Access to care and cardiovascular disease prevention: a cross‐cectional ctudy in 2 latino communities. Medicine. 2015;94:e1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jamal A, Agaku IT, O'Connor E, King BA, Kenemer JB, Neff L. Current cigarette smoking among adults–United States, 2005–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1108–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yu SSK, Ramsey NLM, Castillo DC, Ricks M, Sumner AE. Triglyceride‐based screening tests fail to recognize cardiometabolic disease in African immigrant and African‐American men. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders. 2013;11:15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. G Hamilton T, Green TL. Intergenerational differences in smoking among west Indian, Haitian, Latin American, and African blacks in the United States. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:305–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. King G, Polednak AP, Bendel R, Hovey D. Cigarette smoking among native and foreign‐born African Americans. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9:236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Summary health statistics: National Health Interview Survey, 2013 table a‐14a. 2013.

- 47. Bryc K, Durand EY, Macpherson JM, Reich D, Mountain JL. The genetic ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96:37–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Anderson M. A rising share of the US black population is foreign born. Pew Research Center. 2015:1–32. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Prevalence and Prevalence Ratios of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in African Immigrants and African Americans by Sex

Table S2. Sociodemographic Characteristics of African Immigrants and African Americans in the 2010 to 2016 National Health Interview Surveys by Sex*

Figure S1. Age‐Standardized Prevalence of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in African Americans and African Immigrants by Sex.