Abstract

Background

Off‐target properties of ticagrelor might reduce microvascular injury and improve clinical outcome in patients with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction. The REDUCE‐MVI (Evaluation of Microvascular Injury in Revascularized Patients with ST‐Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction Treated With Ticagrelor Versus Prasugrel) trial reported no benefit of ticagrelor regarding microvascular function at 1 month. We now present the follow‐up data up to 1.5 years.

Methods and Results

We randomized 110 patients with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction to either ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily or prasugrel 10 mg once a day. Platelet inhibition and peripheral endothelial function measurements including calculation of the reactive hyperemia index and clinical follow‐up were obtained up to 1.5 years. Major adverse clinical events and bleedings were scored. An intention to treat and a per‐protocol analysis were performed. There were no between‐group differences in platelet inhibition and endothelial function. At 1 year the reactive hyperemia index in the ticagrelor group was 0.66±0.26 versus 0.61±0.28 in the prasugrel group (P=0.31). Platelet inhibition was lower at 1 month versus 1 year in the total study population (61% [42%–81%] versus 83% [61%–95%]; P<0.001), and per‐protocol platelet inhibition was higher in patients randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel at 1 year (91% [83%–97%] versus 82% [65%–92%]; P=0.002). There was an improvement in intention to treat endothelial function in patients randomized to ticagrelor (P=0.03) but not in patients randomized to prasugrel (P=0.88). Major adverse clinical events (10% versus 14%; P=0.54) and bleedings (47% versus 63%; P=0.10) were similar in the intention‐to‐treat analysis in both groups.

Conclusions

Platelet inhibition at 1 year was higher in the ticagrelor group, without an accompanying increase in bleedings. Endothelial function improved over time in ticagrelor patients, while it did not change in the prasugrel group.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/. Unique Identifier: NCT02422888.

Keywords: endothelial function, microvascular injury, platelet inhibition, prasugrel, ST‐segment‐elevation myocardial infarction, ticagrelor

Subject Categories: Platelets, Acute Coronary Syndromes, Quality and Outcomes

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

This study reports the long‐term follow‐up of patients with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel maintenance therapy and demonstrated a higher platelet inhibition at 1 year with an improvement in peripheral endothelial function in the ticagrelor group. Interestingly, platelet inhibition was significantly lower at 1‐month versus 1‐year follow‐up.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

In patients with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction on P2Y12 inhibitor maintenance therapy, it is clinically of great importance to seek for an optimal balance in the benefit–risk ratio of platelet inhibition.

The lower platelet inhibition at 1 month could be explained either by a hampered platelet inhibition in the subacute phase after ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (with an associated increased risk of ischemic events) or by an exceedingly amplified platelet inhibition after 1 year of P2Y12 inhibitor treatment (with an associated increased bleeding risk).

In patients with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), the preferred treatment is immediate percutaneous coronary intervention of the culprit coronary artery with antiplatelet therapy. Currently, the P2Y12 inhibitors ticagrelor and prasugrel are recommended as antiplatelet therapy both in the acute setting and as maintenance therapy.1 Despite successful revascularization, microvascular injury occurs in about half of patients with STEMI,2 and its presence is associated with poor outcome.3 It has been proposed that equilibrative nucleoside transporter‐1 inhibition of ticagrelor could cause elevated adenosine levels and thereby may preserve endothelial function and prevent microvascular injury in STEMI with potentially better clinical outcome.4, 5, 6, 7 The REDUCE‐MVI (Evaluation of Microvascular Injury in Revascularized Patients with ST‐Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction Treated With Ticagrelor Versus Prasugrel) trial, was the first randomized trial that investigated the potential effect of ticagrelor versus prasugrel maintenance therapy on microvascular injury in patients with STEMI assessed by the index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR).8 Ticagrelor as compared with prasugrel did not show a beneficial effect with regard to the IMR in the culprit vessel 1 month after the index event.

Recently, it was reported that ticagrelor treatment at steady state improves peripheral endothelial function assessed by reactive hyperemic peripheral arterial tonometry (RH‐PAT) (EndoPAT, Itamar Medical Ltd., Caesarea, Israel) in patients with a previous myocardial infarction.9 However, whether ticagrelor maintenance therapy provides benefit over prasugrel with regard to long‐term peripheral endothelial function is unknown. Also, comparative randomized data on platelet inhibition with either ticagrelor or prasugrel maintenance therapy are currently not available.

Here, we present the 1.5‐year clinical follow‐up of the REDUCE‐MVI trial, including serial measurements of platelet inhibition and peripheral endothelial function as assessed by means of RH‐PAT.

Methods

Study Design and Outcome Measures

The current study is the predefined long‐term clinical follow‐up of the REDUCE‐MVI Trial.8 This investigator‐initiated, randomized, multicenter trial compared the potential effects of ticagrelor versus prasugrel maintenance therapy on microvascular injury in patients with STEMI. The study trial design10 and the short‐term primary outcome with IMR at 1 month and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging parameters as secondary outcomes were previously published.8 In the present study, we describe patient characteristics, platelet inhibition, patient symptoms, and clinical outcome (including bleeding) at 1‐ and 1.5‐year follow‐up. Furthermore, we present the serial peripheral endothelial function measurements by means of RH‐PAT. The study protocol complies with the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the institutional review board (local ethics committee), and conforms to the International Conference on Harmonization/Good Clinical Practice standards. The trial is registered at URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov, with the unique identifier: NCT02422888. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The trial was conducted at 6 centers in the Netherlands and Spain. In short, patients with a STEMI presenting <12 hours after onset of symptoms were considered eligible. All patients had multivessel disease, were <75 years old, and received a loading dose of ticagrelor (180 mg). Table S1 includes a complete overview of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After providing written informed consent, patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to either ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily or prasugrel 10 mg once daily as maintenance therapy for 1 year using a secure web‐based electronic case report form system (Castor EDC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). When the physician responsible for the clinical care of the patient decided that the randomized study drug was contraindicated, the patient could stop or switch their P2Y12 inhibitor before 1 year and continued follow‐up for the further duration of the study. Concomitant medical therapy after 1 year was left to the discretion of the treating physician and was based on current guidelines.1 Follow‐up at 1 year was performed before cessation of the P2Y12 inhibitor and at 1.5 years was performed to examine patient outcomes after cessation of the P2Y12 inhibitor. We assessed medication compliance each visit with a questionnaire.

Laboratory Measurements and Platelet Inhibition

Blood samples were collected in the acute setting and at all follow‐up visits and were subsequently sent to the local laboratory to assess standard clinical parameters (eg, blood count, lipid spectrum, and inflammatory status). In addition, in the acute setting during the index procedure, at 1 month during the follow‐up coronary angiogram, and at 1‐year follow‐up, we quantified platelet aggregation by percentage of inhibition by analysis of the collected blood samples with the VerifyNow System (Accumetrics, San Diego, CA). Blood was collected in a citrate‐coated tube, and the first 2 to 4 mL of blood was discarded to prevent spontaneous platelet activation. The percentage of platelet inhibition was calculated as follows: ([BASE−PRU]/BASE)×100 as previously described.11 We assumed a high platelet reactivity when the P2Y12 reaction units (PRU) exceeded 20812, 13 and a low platelet reactivity when PRU was below 85.14 As an alternative threshold we also described PRU <95, as this cutoff value is known to be associated with an increased bleeding risk.15

Peripheral Endothelial Function Measurements

To assess peripheral endothelial function, RH‐PAT using the EndoPAT device was performed in the acute setting (<24 hours after presentation), at 1 month, at 1 year, and at 1.5‐year follow‐up. The EndoPAT device measures the endothelium‐mediated changes in vascular tone with each arterial pulsation by 2 plethysmographic probes placed on the index fingers. RH‐PAT measurements were performed in the contralateral arm used for coronary angiographic access: (1) under resting conditions for 5 minutes; (2) after inflation of a blood cuff on the study arm, while the contralateral (angiographic access site) arm served as control for 5 minutes; and finally (3) after deflation of the blood cuff to induce reactive hyperemia for an additional 5 minutes.

The reactive hyperemia index (RHI) was calculated as a measure of reactive hyperemia by the ratio of the post‐ over preocclusive average amplitude of the RH‐PAT signal, normalized for the control arm to compensate for possible concurrent nonendothelial‐dependent systemic alterations in vascular tone. An exact description of the RH‐PAT measurements was previously published.16 Because of skewness of the data, we described the natural logarithm of RHI.17 A decreased endothelial function was defined as RHI <1.67,18 which resulted in a logarithmic RHI <0.51.

Patient Symptoms and Clinical Follow‐Up

A complete overview of the methods used to assess the occurrence and severity of angina (Seattle Angina Questionnaire and Canadian Cardiovascular Society grading), dyspnea (Borg Dyspnea Scale), and heart failure (New York Heart Association Functional class) is described in Data S1.

Major adverse clinical events (MACE) were prospectively collected between the index event and 1.5‐year follow‐up. MACE was defined as death and recurrent myocardial infarction. As a safety objective, we compared the occurrence and severity of bleedings between both groups. The severity of bleeding was classified by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium criteria.19 A blinded clinical study investigator performed the adjudication of events.

Statistical Analysis

The REDUCE‐MVI trial had a superiority design with a power of 80% to detect a between‐group difference in IMR of 7 (arbitrary unit) with an SD of 12 in favor of the ticagrelor group at 1‐month follow‐up. Details of the sample size calculation are provided in Data S2. SPSS Statistics, version 22 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was used to perform statistical analyses. For the current study, an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis was used to assess the difference in outcome measures in patients randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel maintenance therapy. We prespecified the per‐protocol (PP) analysis for secondary outcomes in the original protocol. PP analyses for all end points during 1‐year follow‐up were performed in those patients who did not switch or stop their randomized P2Y12 therapy before 1 year. PP analyses for 1.5‐year follow‐up involved the subgroup of patients included in the 1‐year follow‐up PP analysis that no longer received a P2Y12 inhibitor at 1.5‐year follow‐up.

A complete overview of the statistical analysis methods can be found in Data S3. Continuous normally distributed data were reported as mean±SD and non–normally distributed data as median (interquartile range). Dichotomous data were described as number (%). To assess between‐group differences in continuous variables, an independent t test or Mann–Whitney U test was used as appropriate. Paired analyses were performed with the paired sample t test or Wilcoxon signed‐rank test as appropriate. To assess between‐group differences in categorical variables, a Pearson chi‐square test was used, and results were summarized as numbers (%). Paired analyses with dichotomous variables were performed by the McNemar test. A linear mixed‐model analysis was used to compare changes in mean RHI over time between treatment groups. Generalized estimating equations were used to compare changes in proportion of patients with decreased RHI value over time between treatment groups. Time to MACE was visualized by Kaplan–Meier curve and compared between groups using the log‐rank test. A hazard ratio was calculated, with prasugrel as the reference group. Statistical significance was assumed when 2‐sided P was <0.05.

Results

Study Population and Treatment Strategy

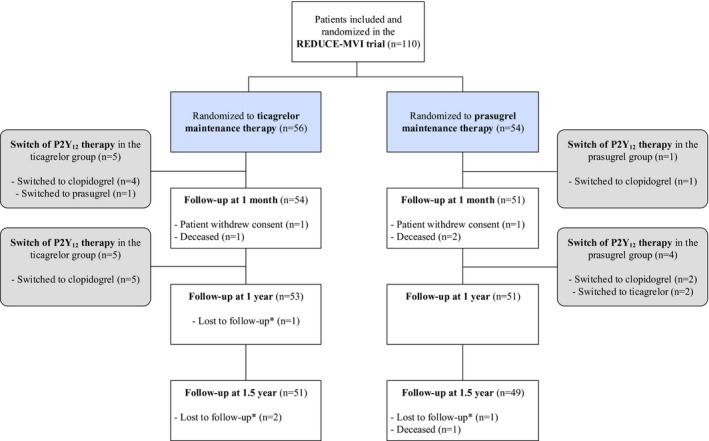

Between May 2015 and October 2017 a total of 110 patients with STEMI were randomized to either ticagrelor (n=56) or prasugrel (n=54) maintenance therapy. Baseline and procedural characteristics of the total study population during the index procedure are described in Tables S2 and S3, respectively. Two patients withdrew informed consent before the primary end point. The total study population therefore consisted of 108 patients (ticagrelor [n=55] versus prasugrel [n=53]). Figure 1 represents the study flowchart during the conduct of the study. Figure S1 represents the study flowchart of the patients included in the per‐protocol analysis at 1 year (n=84) and at 1.5 years (n=77), and Table S4 demonstrates the PP patient characteristics at 1‐year follow‐up. There was no difference in time between ticagrelor loading dose and the start of the index procedure (55 [39–70] minutes in the ticagrelor group versus 50 [36–71] minutes in the prasugrel group; P=0.55)

Figure 1.

Study enrollment and participation flowchart. *In these patients we did retrieve the survival status at 1.5‐year follow‐up, and we therefore also included them in the final analysis.

One‐year follow‐up was performed at 11.8±0.5 months and 1.5‐year follow‐up at 18.6±1.4 months. There were no relevant differences in patient characteristics, medication use or laboratory values at 1‐year follow‐up in patients randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel maintenance therapy (Table 1). During the conduct of the study, 9% of patients randomized to ticagrelor switched to either prasugrel or clopidogrel, and 5% of patients randomized to prasugrel switched to ticagrelor or clopidogrel for various reasons (Table S5). A total of 8% of patients stopped with their randomized P2Y12 inhibitor before 1‐year follow‐up without replacement of another P2Y12 inhibitor. There were no significant differences between patients initially randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel in cessation/switch of the initially randomized P2Y12 treatment (P=0.44). At 1.5‐year follow‐up, 11% of patients were still on P2Y12 inhibition therapy: 4% received ticagrelor, 2% received prasugrel, and 6% received clopidogrel maintenance therapy.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at 1‐Year Follow‐Up

| Ticagrelor (n=53) | Prasugrel (n=51) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to 1‐y follow‐up (d), mean±SD | 359±7 | 360±19 | 0.64 |

| Age at initial admission, y, mean±SD | 60.1±10.4 | 61.2±8.8 | 0.54 |

| Male, n (%) | 46/53 (86.8) | 42/51 (82.4) | 0.53 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), mean±SD | 134±16 | 135±17 | 0.78 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg), mean±SD | 81±11 | 80±13 | 0.77 |

| Heart rate (bpm), mean±SD | 64±14 | 66±11 | 0.59 |

| Medication at follow‐up | |||

| P2Y12 inhibitor, n (%) | 49/53 (92.5) | 46/51 (90.2) | 0.68 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid, n (%) | 51/53 (96.2) | 48/51 (94.1) | 0.62 |

| Oral anticoagulants, n (%) | 1/53 (1.9) | 1/51 (2.0) | 0.98 |

| β‐Blocker, n (%) | 44/53 (83.0) | 37/51 (72.5) | 0.20 |

| ACE‐i, n (%) | 31/53 (58.5) | 29/51 (56.9) | 0.87 |

| ARB, n (%) | 9/53 (17.0) | 10/51 (19.6) | 0.73 |

| Lipid lowering medication, n (%) | 48/53 (90.6) | 47/51 (92.2) | 0.77 |

| Long acting nitrate, n (%) | 2/53 (3.8) | 1/51 (2.0) | 0.58 |

| CCB, n (%) | 4/53 (7.5) | 3/51 (5.9) | 0.74 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 2/53 (3.8) | 6/51 (12.0) | 0.12 |

| Diabetes mellitus medication, n (%) | 5/53 (9.4) | 3/51 (5.9) | 0.50 |

| Anti‐inflammatory drugs, n (%) | 3/53 (5.7) | 5/51 (9.8) | 0.43 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| Hemoglobin (mmol/L), mean±SD | 9.0±0.7 | 8.9±0.8 | 0.45 |

| Hematocrit (L/L), mean±SD | 0.43±0.04 | 0.43±0.04 | 0.84 |

| Platelet count (×109/L), mean±SD | 242.5±61.9 | 235.0±50.1 | 0.51 |

| Total leukocyte count (×109/L), median (IQR) | 6.4 (5.7–7.9) | 7.0 (5.8–8.1) | 0.42 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L), mean±SD | 3.4±0.9 | 3.7±1.1 | 0.18 |

| HDL (mmol/L), mean±SD | 1.2±0.4 | 1.3±0.4 | 0.35 |

| LDL (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.2–2.0) | 1.6 (1.1–2.2) | 0.75 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 1.4 (2.1–0.9) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | >0.99 |

| CRP (mg/L), median (IQR) | 2.5 (2.5–2.5) | 2.5 (2.5–2.5) | 0.88 |

| LDH (U/L), median (IQR) | 197 (182–220) | 194 (182–228) | 0.99 |

| Glucose (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 5.5 (5.0–6.5) | 5.3 (4.9–6.1) | 0.61 |

| NT‐proBNP (ng/L), median (IQR) | 90 (43–340) | 97 (49–243) | 0.81 |

ACE‐i indicates angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CRP, C‐reactive protein; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; IQR, interquartile range; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide.

Platelet Inhibition

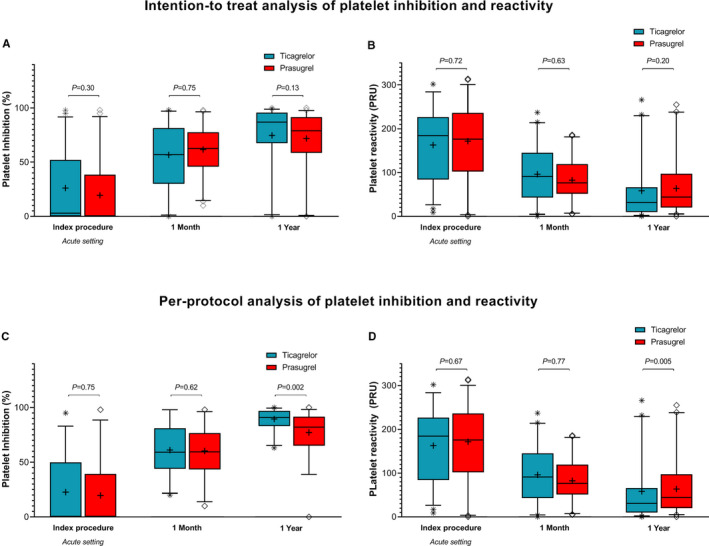

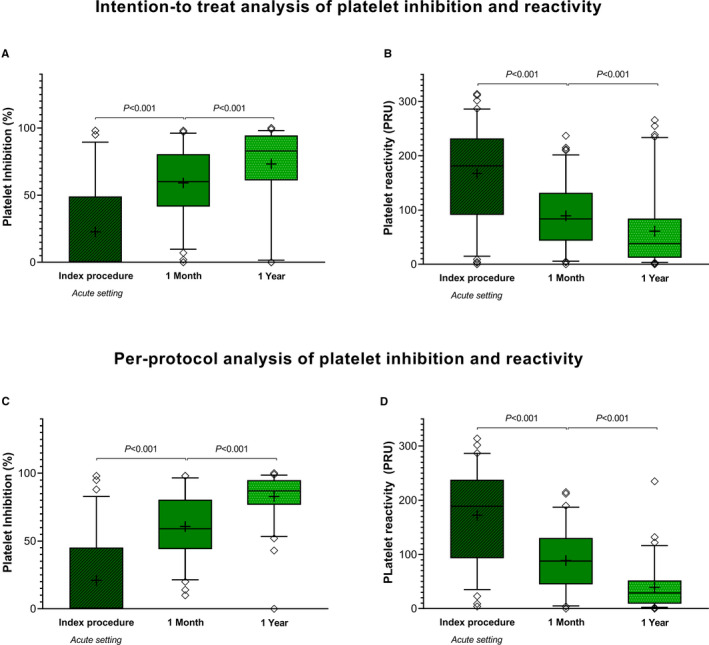

In the ITT analysis, there were no significant differences between the ticagrelor versus prasugrel group in platelet inhibition or reactivity during the index procedure, at 1 month or at 1 year (Table 2, Figure 2A and 2B). In the total study population, platelet inhibition was lower (61 [42–81] versus 83 [61–95]; P<0.001) and PRU was higher (84 [44–132] versus 38 [12–84]; P<0.001) at 1 month compared with 1 year (Figure 3A and 3B). At 1‐year follow‐up, 79% of patients randomized to ticagrelor had low platelet reactivity (<85) versus 71% in the prasugrel group (P=0.39). A total of 7% of patients randomized to ticagrelor had high platelet reactivity (>208) versus 7% in the prasugrel group (P=0.95).

Table 2.

ITT Platelet Inhibition and Platelet Reactivity

| Ticagrelor (n=55) | Prasugrel (n=53) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRU, median (IQR) | |||

| Index procedure | 185 (87–227) | 176 (102–236) | 0.72 |

| 30 d | 91 (43–145) | 76 (51–119) | 0.63 |

| 1 y | 31 (10–66) | 44 (20–97) | 0.20 |

| Inhibition (%), median (IQR) | |||

| Index procedure | 3 (0–51) | 0 (0–39) | 0.30 |

| 30 d | 59 (30–83) | 63 (46–78) | 0.75 |

| 1 y | 87 (68–96) | 79 (59–92) | 0.13 |

| LPR (<85), n (%) | |||

| Index procedurea | 10 (22.2%) | 9 (18.8%) | 0.68 |

| 30 db | 22 (45.8%) | 26 (54.2%) | 0.41 |

| 1 yc | 34 (79.1%) | 32 (71.1%) | 0.39 |

| HPR (>208), n (%) | |||

| Index procedurea | 19 (41.3%) | 19 (39.6%) | 0.87 |

| 30 db | 4 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.04 |

| 1 yc | 3 (7.0%) | 3 (6.7%) | 0.95 |

ITT analysis in the total study population of 108 patients. HPR indicates high platelet reactivity; IQR, interquartile range; ITT, intention‐to‐treat; LPR, low platelet reactivity; PRU, platelet reactivity unit.

ITT analysis; ticagrelor n=45 and prasugrel n=48.

ITT analysis; ticagrelor n=48 and prasugrel n=48.

ITT analysis; Ticagrelor n=43 and Prasugrel n=45.

Figure 2.

Platelet inhibition and reactivity in patients randomized to ticagrelor vs prasugrel. In the intention to treat analysis (A and B), we included the total study population of 108 patients. The per‐protocol analysis (C and D) was performed in 84 patients who did not switch or stop their randomized P2Y12 therapy before 1‐year follow‐up. 3A (ITT) and C (PP) indicate the platelet inhibition, and 3B (ITT) and D (PP) indicate the platelet reactivity in patients randomized to ticagrelor vs prasugrel maintenance therapy at 3 different time points. The line in the boxplots indicates the median, and the cross indicates the mean. PP indicates per‐protocol; PRU, platelet reactivity unit; ITT, intention to treat.

Figure 3.

Platelet inhibition and reactivity in the total study population. In the intention‐to‐treat analysis (A and B), we included the total study population of 108 patients. The per‐protocol analysis (C and D) was performed in 84 patients who did not switch or stop their randomized P2Y12 therapy before 1‐year follow‐up. A‐C indicates the platelet inhibition, and B‐D indicates the platelet reactivity in the total study population at 3 different time points. The line in the boxplots indicates the median, and the cross indicates the mean. PRU indicates platelet reactivity unit.

In the PP analysis, platelet inhibition at 1‐year follow‐up was significantly higher in patients randomized to ticagrelor compared with prasugrel (Table 3, Figure 2C and 2D). Fewer patients had PRU <95 at 1‐month versus 1‐year follow‐up (53% versus 91%; P<0.001). Figure 3C and 3D demonstrates the PP platelet inhibition in the total study population from the index procedure to 1‐year follow‐up.

Table 3.

PP Platelet Inhibition and Platelet Reactivity

| Ticagrelor (n=41) | Prasugrel (n=43) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRU, median (IQR) | |||

| Index procedure | 189 (84–239) | 188 (114–237) | 0.67 |

| 30 d | 93 (45–138) | 84 (53–122) | 0.77 |

| 1 y | 19 (7–38) | 39 (20–73) | 0.005 |

| Inhibition (%), median (IQR) | |||

| Index procedure | 0 (0–50) | 0 (0–39) | 0.75 |

| 30 d | 61 (44–82) | 60 (44–77) | 0.62 |

| 1 y | 91 (83–97) | 82 (65–92) | 0.002 |

| LPR (<85), n (%) | |||

| Index procedurea | 8 (23.5%) | 6 (15.8%) | 0.41 |

| 30 db | 15 (44.1%) | 19 (50.0%) | 0.62 |

| 1 yc | 29 (96.7%) | 29 (78.4%) | 0.03 |

| HPR (>208), n (%) | |||

| Index procedurea | 15 (44.1%) | 16 (42.1%) | 0.86 |

| 30 db | 2 (5.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0.13 |

| 1 yc | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0.36 |

The PP analysis was performed in 84 patients who did not switch or stop their randomized P2Y12 therapy before 1‐year follow‐up. HPR indicates high platelet reactivity; IQR, interquartile range; LPR, low platelet reactivity; PP, per‐protocol; PRU, platelet reactivity unit.

PP analysis; ticagrelor n=34 and prasugrel n=38.

PP analysis; ticagrelor n=34 and prasugrel n=38.

PP analysis; ticagrelor n=30 and prasugrel n=38.

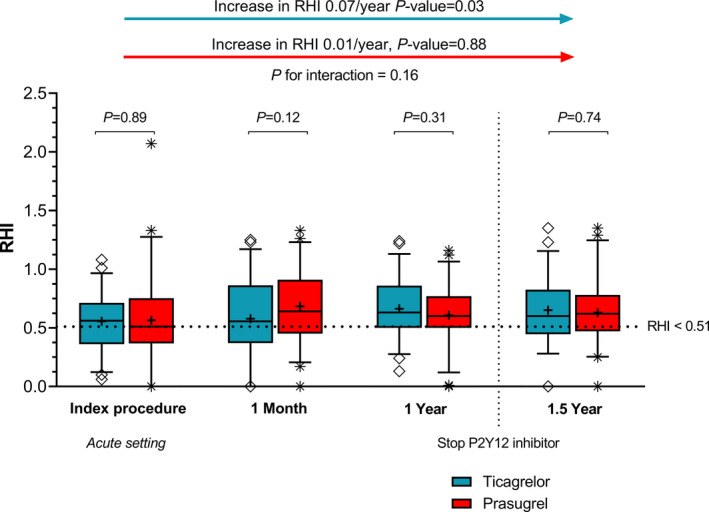

Peripheral Endothelial Function

In the ITT analysis, there were no significant differences in mean RHI between patients randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel at individual time points (Figure 4). At 1‐year follow‐up, RHI in the ticagrelor group was 0.66±0.26 versus 0.61±0.28 in the prasugrel group (P=0.31). In patients with ticagrelor maintenance therapy, average RHI significantly improved (P=0.03), while in patients with prasugrel maintenance therapy, RHI did not change (P=0.88) over time. However, slopes were not found to differ between groups (P=0.16). There was no difference in the number of patients with decreased RHI between patients randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel in the acute setting (43% versus 48%; P=0.58), at 1‐month (41% versus 29%; P=0.23), at 1‐year (26% versus 31%; P=0.57) or at 1.5‐year follow‐up (33% versus 30%; P=0.76). The number of patients with impaired RHI values decreased from acute to 1 year (P=0.05) in the ticagrelor group, while in the prasugrel group it did not change (P=0.30). In the total study population, RHI was significantly lower in the acute setting compared with 1.5‐year follow‐up (0.54±0.33 versus 0.64±0.30; P=0.03). There were significantly more patients with lower RHI in the acute setting versus 1‐year (47% versus 39%; P=0.03) and 1.5‐year (47% versus 42%; P=0.04) follow‐up. The improvement in RHI over time (P=0.098) in the total study population was described in Figure S2.

Figure 4.

Peripheral endothelial function and improvement in peripheral endothelial function in patients randomized to ticagrelor vs. prasugrel maintenance therapy. The dashed line represents the established cutoff value for decreased peripheral endothelial function (RHI <1.67 equals the natural logarithm RHI <0.51). The line in the boxplots indicates the median and the cross indicates the mean. The increase in RHI over time was calculated using a mixed‐model analysis including time as main effect. RHI indicates reactive hyperemia index.

In the PP analysis, there were no significant between‐group differences in mean RHI at all time points, but as in ITT analysis, RHI significantly improved over time in patients randomized to ticagrelor (P=0.04), while it did not in patients randomized to prasugrel (P=0.56) (Figure S3). RHI did not significantly change after cessation of the P2Y12 inhibitor in patients randomized to ticagrelor (0.62±0.31 at 1 year versus 0.62±0.38 at 1.5‐year; P=0.90) or prasugrel (0.67±0.27 at 1 year versus 0.68±0.29 at 1.5 year; P=0.86). The improvement in RHI over time in the total study population was described in Figure S2.

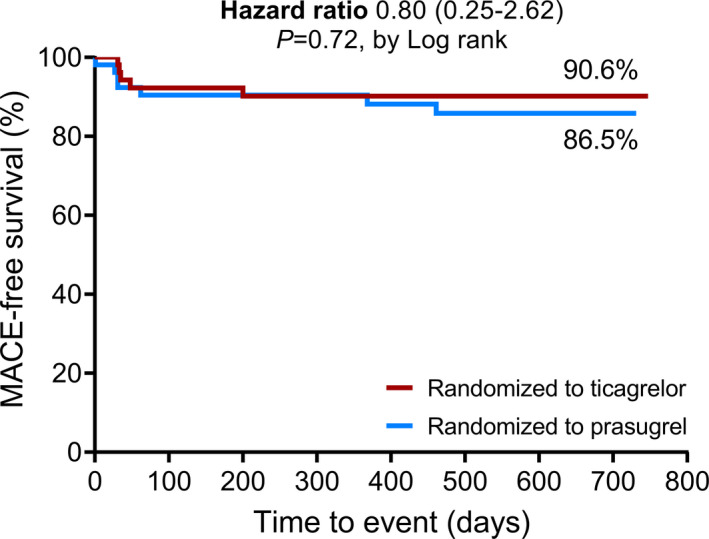

Clinical and Patient Reported Outcome

In the ITT analysis, there were no between‐group differences in the occurrence or severity of dyspnea or angina pectoris at follow‐up (Tables 4 and 5). The number of patients with an increased New York Heart Association Functional score (New York Heart Association Functional score >1) at 1.5‐year follow‐up did not differ between patients randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel (13 [26%] versus 13 [27%]; P=0.91). There were no patients with stroke and 8 patients with myocardial infarction (7.8% in the ticagrelor group versus 8.2% in the prasugrel group; P=0.95). There were 22 patients hospitalized during our study (17.0% in the ticagrelor group versus 21.6% in the prasugrel group; P=0.55; reasons for hospitalization are described in Table S6). The combined end point of MACE at 1.5 years was not significantly different in patients randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel (10% versus 14%; P=0.54; Table 5). The hazard ratio for MACE at 1.5‐year follow‐up with prasugrel as reference group was 0.80 (0.25–2.62), with P=0.72 (Figure 5). During the conduct of the study, 50% of patients had either an actionable minor or major bleeding (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium >2). There was no significant between‐group difference in bleedings in patients randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel (47% versus 63%, P=0.10). The majority of bleedings were nonactionable Bleeding Academic Research Consortium 1 bleedings, and there was no significant difference in Bleeding Academic Research Consortium >1 bleeding score between patients randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel maintenance therapy (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Patient Symptoms and Clinical Outcome at 1 Year

| Ticagrelor (n=53a) | Prasugrel (n=51b) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angina pectoris, n (%) | 11/52 (21.2) | 9/51 (17.6) | 0.65 |

| CCS class, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 9/11 (81.8) | 5/9 (55.6) | 0.19 |

| 2 | 2/11 (18.2) | 3/9 (33.3) | |

| 3 | 0/11 (0.0) | 1/9 (11.1) | |

| 4 | 0/11 (0.0) | 0/9 (0.0) | |

| SAQ, median (IQR) | |||

| Angina frequency | 100 (100–100) | 100 (100–100) | 0.99 |

| Physical limitation | 92 (83–100) | 100 (75–100) | 0.52 |

| Quality of life | 71 (58–89) | 83 (67–100) | 0.10 |

| Angina stability | 100 (100–100) | 100 (100–100) | 0.84 |

| Treatment satisfaction | 94 (81–100) | 94 (81–100) | 0.25 |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 22/52 (42.3) | 18/51 (35.3) | 0.47 |

| MBS>3, n (%) | 6/22 (27.3) | 5/18 (27.8) | 0.97 |

| Total number of bleedings, n (%) | 23/51 (45.1) | 30/51 (58.8) | 0.17 |

| BARC score, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 28/51 (54.9) | 21/51 (41.2) | 0.33 |

| 1 | 19/51 (37.3) | 27/51 (52.9) | |

| 2 | 3/51 (5.9) | 2/51 (3.9) | |

| 3 | 0/51 (0.0) | 0/51 (0.0) | |

| 4 | 1/51 (2.0) | 1/51 (2.0) | |

| 5 | 0/51 (0.0) | 0/51 (0.0) | |

| Death, n (%) | 1/55 (1.8) | 2/53 (3.8) | 0.54 |

| Recurrent myocardial infarction, n (%) | 4/53 (7.5) | 3/51 (5.9) | 0.74 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Stent thrombosis, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Hospitalization, n (%) | 6/53 (11.3) | 9/51 (17.6) | 0.36 |

| Malignant arrhythmia, n (%)c | 0/52 (0.0) | 1/51 (2.0) | 0.31 |

| Intercurrent CAG (without the need for PCI), n (%)c | 3/52 (5.8) | 0/51 (0.0) | 0.08 |

| PCI, n (%)c | 3/52 (5.8) | 1/51 (2.0) | 0.32 |

| Cardiac surgery, n (%)c | 0/52 (0.0) | 0/51 (0.0) | NA |

| MACE, n (%) | 5/54 (9.3) | 5/53 (9.4) | 0.98 |

We included them in the final analysis regarding the occurrence of events (MACE) because we retrieved their survival status at 1 year, except for 1 patient in the prasugrel group for whom we did not have information regarding recurrent myocardial infarction. BARC indicates Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CAG, coronary angiography; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; IQR, interquartile range; MACE, major adverse clinical events including death and recurrent myocardial infarction; MBS, Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale; NA, not applicable; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire.

In the ticagrelor group, 1 patient was deceased and 1 patient was lost to follow‐up before 1‐year follow‐up.

In the prasugrel group, 2 patients were deceased before 1‐year follow‐up.

There were no additional events reported between 1‐ and 1.5‐year follow‐up.

Table 5.

Patient Symptoms and Clinical Outcome at 1.5 Years

| Ticagrelor (n=51a) | Prasugrel (n=49b) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angina pectoris, n (%) | 10/51 (19.6) | 4/49 (8.2) | 0.10 |

| CCS class, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 5 (50.0) | 2/4 (50.0) | 0.87 |

| 2 | 4 (40.0) | 2/4 (50.0) | |

| 3 | 1 (10.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | |

| 4 | 0 (0.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | |

| SAQ, median (IQR) | |||

| Angina frequency | 100 (98–100) | 100 (100–100) | 0.36 |

| Physical limitation | 94 (83–100) | 96 (81–100) | 0.79 |

| Quality of life | 75 (66–92) | 83 (67–92) | 0.16 |

| Angina stability | 100 (80–100) | 100 (100–100) | 0.29 |

| Treatment satisfaction | 94 (81–100) | 100 (88–100) | 0.08 |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 14/51 (27.5) | 18/49 (36.7) | 0.32 |

| MBS>3, n (%) | 6/14 (42.9) | 8/18 (44.4) | 0.93 |

| Total number of bleedings, n (%) | 24/51 (47.1) | 31/50 (63.3) | 0.10 |

| BARC score, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 27/51 (52.9) | 18/50 (36.7) | 0.33 |

| 1 | 19/51 (37.3) | 26/50 (53.1) | |

| 2 | 4/51 (7.8) | 4/50 (8.2) | |

| 3 | 0/51 (0.0) | 0/50 (0.0) | |

| 4 | 1/51 (2.0) | 1/50 (2.0) | |

| 5 | 0/51 (0.0) | 0/50 (0.0) | |

| Ticagrelor (n=55a) | Prasugrel (n=53b) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death, n (%) | 1/55 (1.8) | 3/53 (5.7) | 0.29 |

| Recurrent myocardial infarction, n (%) | 4/51 (7.8) | 4/49 (8.2) | 0.95 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Stent thrombosis, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Hospitalization, n (%) | 9/53 (17.0) | 11/51 (21.6) | 0.55 |

| MACE, n (%) | 5/52 (9.4) | 7/52 (13.5) | 0.54 |

We included them in the final analysis regarding the occurrence of events (MACE) because we retrieved their survival status at 1 year, except for 1 patient in the prasugrel group for whom we did not have information regarding recurrent myocardial infarction. BARC indicates Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; IQR, interquartile range; MACE, major adverse clinical events including death and recurrent myocardial infarction; MBS, Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale; NA, not applicable; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire.

In the ticagrelor group, 1 patient was deceased and 3 patients were lost to follow‐up (of whom 2 patients had hospitalization at 1 year follow‐up, which we reported) before 1.5‐year follow‐up.

In the prasugrel group, 3 patients were deceased and 1 patient was lost to follow‐up before 1.5‐year follow‐up.

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier curve for the occurrence of MACE at 1.5‐year follow‐up. The Kaplan–Meier curve of the MACE‐free survival at 1.5‐year follow‐up in patients randomized to ticagrelor vs. prasugrel maintenance therapy. The hazard ratio with the 95% CI is for the occurrence of MACE, with prasugrel as reference. There is no significant between‐group difference in MACE. FU indicates follow‐up; MACE, major adverse clinical events.

Also in the PP analysis, there were no significant between‐,group differences in patient symptoms, MACE or bleedings (Table S7). The between‐group relative difference (%) and risk (ratio) for clinical discrete outcomes is demonstrated in Table S8.

Discussion

The current long‐term follow‐up study of the REDUCE‐MVI trial reports platelet inhibition, peripheral endothelial function, and clinical outcome up to 1.5 years in patients with STEMI randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel maintenance therapy. While the ITT analyses did not reveal between‐group differences in platelet inhibition, peripheral endothelial function, the occurrence of patient reported symptoms, bleedings, or MACE up to 1.5 years, the PP analysis revealed a significantly higher platelet inhibition at 1‐year follow‐up in patients randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel; an increase in platelet inhibition from 1‐month to 1‐year follow‐up; a significant improvement in peripheral endothelial function from acute to long‐term follow‐up in patients randomized to ticagrelor, which persisted after cessation, and which did not occur in patients randomized to prasugrel; and a significantly lower peripheral endothelial function in the acute setting versus 1.5‐year follow‐up.

The multicenter PRAGUE‐18 (Comparison of Prasugrel and Ticagrelor in the Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial randomized patients with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) to either ticagrelor or prasugrel maintenance therapy in the first month following primary percutaneous coronary intervention and reported an equivalent efficacy and safety between both P2Y12 inhibitors.20 Present guidelines therefore recommend using either ticagrelor or prasugrel as maintenance therapy in patients presenting with STEMI.1 It has been suggested that ticagrelor may increase adenosine levels, predominantly at sites of ischemia and tissue injury, by blockage of the equilibrative nucleoside transporter‐1 transporter and thus inhibiting adenosine uptake by red blood cells,4, 5 which we could not confirm in the acute setting and up to 1 month in the REDUCE‐MVI trial.8 Below, we discuss the long‐term effects of ticagrelor versus prasugrel maintenance therapy on platelet inhibition, endothelial function, and clinical outcome.

Platelet Inhibition

The REDUCE‐MVI trial reported no significant difference in platelet inhibition from the index event to 1‐month follow‐up between patients randomized to ticagrelor compared with prasugrel maintenance therapy.8 The loading dose of ticagrelor given to all patients in the acute setting could have led to a similar platelet inhibition in the acute phase, and because platelet inhibition in the acute and subacute setting was impaired, this could have diluted between‐group differences.

In the current long‐term follow‐up study, we demonstrated higher platelet inhibition at 1 year in the ticagrelor versus prasugrel group, which is in line with a large meta‐analysis.21 A possible mechanism that could explain the higher platelet inhibition in the ticagrelor group is the 24‐hour systemic exposure of a direct active compound of ticagrelor versus the short plasma exposure (2–4 hours) of the active metabolite of thienopyridines.22 Furthermore, ticagrelor is a direct‐acting drug that binds reversibly to the P2Y12 receptor, while prasugrel is a prodrug that binds irreversibly to the P2Y12 receptor.23 In addition, ticagrelor inhibits platelet aggregation not only by P2Y12 antagonism but also via adenosine.24 In line with our findings, Perl et al25 demonstrated an increased platelet reactivity in patients with STEMI randomized to prasugrel compared with ticagrelor in the acute setting and up to 1 month, which was confirmed in a randomized crossover pharmacodynamics study in stable patients.26 Consequently, one might speculate that ticagrelor, in comparison with prasugrel maintenance therapy, reduces the occurrence of ischemic cardiovascular events at the expense of an increased bleeding risk. The recently published ISAR‐REACT‐5 (Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment 5) trial, however, demonstrated the opposite with an increased occurrence of the primary composite end point of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke at 1‐year follow‐up in the ticagrelor versus prasugrel group (9.3% versus 6.9%) in 4018 patients with ACS, without a between‐group difference in the occurrence of major bleeding.27

Additionally, for the first time to our knowledge, we report a lower platelet inhibition at 1 month compared with 1 year in our total STEMI population. This could be explained either by a hampered platelet inhibition in the subacute phase after STEMI (with an associated increased risk of ischemic events) or by an exceedingly amplified platelet inhibition after 1 year of P2Y12 inhibitor treatment (with an associated increased bleeding risk). It has been proposed that in the acute setting of STEMI, increased levels of reticulated (immature) platelets could increase platelet reactivity in patients on P2Y12 inhibitor maintenance therapy.28 Alternatively, increased reactive oxygen species and lipoperoxidation following STEMI are also predictors for increased platelet reactivity.29 In patients with stable CAD undergoing elective coronary angiogram, there was a large interindividual variability in platelet inhibition that was dependent on pretreatment platelet reactivity,30 which is increased after STEMI. We hypothesize that in the subacute phase, these mechanisms are not fully normalized yet and contribute to the lower platelet inhibition at 1 month and may furthermore explain the increased risk of ischemic events following STEMI.31, 32 Results by Lynch et al33 support this hypothesis, demonstrating an increased platelet aggregation up to 3 months after the ACS index event. In patients with STEMI, a PRU ≥282 was associated with the occurrence of ischemic events and death.34 Our study was not powered to detect a difference in ischemic events or death. On the contrary, a PRU <95 was associated with a 1.7‐fold higher risk of bleeding.15 Interestingly, we found more patients with a PRU <95 at 1‐year versus 1‐month follow‐up, which could indicate an excessive platelet inhibition at 1 year. Concomitantly, it is clinically of great importance to seek for an optimal balance in the benefit–risk ratio of platelet inhibition in patients with STEMI receiving P2Y12 inhibitor maintenance therapy.

Peripheral Endothelial Function

Endothelial dysfunction is not limited to the coronary arteries,35 and consequently RH‐PAT is able to measure the status of peripheral endothelial function, which correlates with coronary endothelial function.16 In the acute setting of STEMI, circulating markers for endothelial injury in peripheral blood samples are elevated,36 which supports our finding of an impaired peripheral endothelial function shortly after the index event.

We demonstrate an improvement in endothelial function in patients randomized to ticagrelor, while in patients randomized to prasugrel, endothelial function did not significantly improve over time, although it must be noted that the improvement over time was not significantly different between both groups. Similar to our results, Torngren et al9 also reported an improvement in peripheral endothelial function in patients with ACS treated with ticagrelor versus prasugrel. In patients with ACS, ticagrelor improved endothelial function, reduced inflammatory cytokines, and increased circulating progenitor cells.37 The recently published randomized crossover HI‐TECH (Hunting for the Off‐Target Properties of Ticagrelor on Endothelial Function in Humans) trial reported no beneficial effect of ticagrelor over prasugrel or clopidogrel treatment with regard to peripheral endothelial function, but they did not assess the potential effects of ticagrelor on endothelial function over a prolonged time period.38 The statistical insignificance between slopes of both groups could have been attributable to the limited statistical power to reveal an interaction.

Although we could not demonstrate increased adenosine plasma levels in the acute and subacute phase in patients randomized to ticagrelor in the REDUCE‐MVI trial,8 this does not exclude possible stimulation of the endothelium by adenosine on a local level, resulting in a release of microcirculatory vasodilators such as nitric oxide, endothelial hyperpolarizing factor, and prostacyclins.39, 40 Endothelial hyperpolarizing factor induces endothelium‐dependent microcirculatory vasodilation by activation of the potassium channels41 and hence remains an interesting target for future studies investigating potential effects of ticagrelor on endothelial function. Additionally, an increase in local concentrations of adenosine may lead to microcirculatory vasodilation by activation of the membrane‐bound α2A‐adenosine receptors.42 We hypothesize that these combined effects of ticagrelor are accountable for the improvement in endothelial function. Further research is necessary to explore the potential mechanisms by which ticagrelor augments peripheral endothelial function.

Patient Symptoms and Clinical Outcome

A well‐known drug‐specific side effect of ticagrelor unrelated to pulmonary function is the manifestation of dyspnea.43, 44 We demonstrated a 42% occurrence of dyspnea in the ticagrelor group versus 35% in the prasugrel group (nonsignificant relative difference of 17%) and a similar severity of dyspnea at 1 year. Although most patients in our study were revascularized at 1‐month follow‐up, we know that (microvascular) angina still occurs in about 40%.45 We hypothesized that ticagrelor could improve (microvascular) angina by its previously discussed off‐target properties. In our study, we did not observe between‐group differences in the presence or severity of angina pectoris or heart failure.

In our study, despite limited statistical power, MACE (9% in the ticagrelor group versus 14% in the prasugrel group) and the occurrence of bleeding (47% in the ticagrelor group versus 63% in the prasugrel group) at long‐term follow‐up were not statistically different in patients randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel. This was in line with a previous observational study in 318 patients with STEMI with the combined end point of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at 1‐year follow‐up.46 As our study was not powered to detect differences in clinical end points, caution is needed interpreting our results. The TRITON‐TIMI‐38 (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition With Prasugrel–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38) showed that prasugrel compared with clopidogrel prevents ischemic events in patients with ACS, but this resulted in an accompanying increase in Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction major bleedings.47 The PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial demonstrated a similar benefit of ticagrelor over clopidogrel with regard to the occurrence of ischemic events in patients with ACS, but without an increase in Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction major bleeding rate.48 On the other hand, it has been reported that patients with STEMI randomized to ticagrelor have an increased risk of bleeding compared with prasugrel.46 The ISAR‐REACT‐5 trial including 41.1% STEMI, 46.2% non‐ST‐segment‐elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and 12.7% unstable angina patients demonstrated reduced occurrence of MACE without a difference in major bleeding in the prasugrel versus ticagrelor group in a modified intention‐to‐treat analysis.27

Limitations

There are some limitations that should be considered. First of all, the current study was not powered to detect a significant between‐group difference in secondary outcomes. The sample size was determined to detect a between‐group difference in the primary end point (IMR at 1 month). Including a PP analysis in our study could have led to selection bias excluding those patients who stopped or switched with their initial randomized medication, although the number of patients deviating from their randomized medication did not differ between groups. In the REDUCE‐MVI trial, we reported no differences in adenosine levels in the acute setting up to 1 month in patients randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel maintenance therapy. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that this would not change during long‐term follow‐up, and thus we did not measure adenosine levels at 1‐ and 1.5‐year follow‐up. In the REDUCE‐MVI main paper, we report a longer symptom‐to‐balloon time and a higher proportion of patients with hypertension in the ticagrelor compared with the prasugrel group. These differences were not statistically significant but could have influenced results. Furthermore, we did not test P2Y12‐inhibition adherence by means of ticagrelor or prasugrel levels at follow‐up, but we did assess therapy adherence at follow‐up by questionnaires and platelet inhibition. Because our main results were primarily based on an ITT analysis, a potential lack in therapy adherence would not alter our main outcomes. Furthermore, we did not mark the time of intake of the P2Y12 inhibitors on follow‐up days, so the time between medication intake and platelet inhibition tests could vary between patients and randomized groups. At 1 month, blood samples were collected during coronary angiography, which may have influenced platelet inhibition tests. Finally, the study participants, treating physicians, and study team were not blinded for the treatment allocation, and therefore this could have biased our results. The events, however, were adjudicated by a blinded study investigator.

Conclusions

In this predefined 1.5‐year follow‐up study of the REDUCE‐MVI trial, we report platelet inhibition, peripheral endothelial function, and clinical outcome in patients with STEMI randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel maintenance therapy. Ticagrelor maintenance therapy provided higher platelet inhibition at 1 year compared with prasugrel. Additionally, ticagrelor improved peripheral endothelial function from the acute moment to 1.5‐year follow‐up, albeit not statistically different compared with patients on prasugrel maintenance therapy. Patient symptoms, bleedings, and MACE rate were not statistically different between both groups; however, our study was not powered to detect differences in clinical outcome.

Sources of Funding

AstraZeneca supported this investigator‐initiated study with an unrestricted grant. The collaboration is financed by the Ministry of Economic Affairs by means of PPP Allowance made available by the Top Sector Life Sciences & Health to stimulate public–private partnerships.

Disclosures

Prof. dr. van Royen reports institutional research grants from AstraZeneca, Abbott, Philips, and Biotronik, and honorarium from Medtronic, Boston, Amgen, and Microport outside the submitted work. Prof. dr. Escaned reports consultancy work for Philips outside of the submitted work. Prof. dr. Piek reports nonfinancial support from Abbott Vascular as a member of the medical advisory board and personal fees and nonfinancial support from Philips/Volcano as a consultant. Prof. dr. von Birgelen reports institutional research grants from Abbott Vascular, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic outside the submitted work. Prof. dr. Valgimigli reports grants from Medtronic, Abbott, Chiesi, Baye, Boeringher, Menarini, Servier, and Daiichi Sankyo outside of the submitted work. Dr van Leeuwen reports an institutional research grant from AstraZeneca. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Data S1. Methods and Scores for Patient Symptom Assessment.

Data S2. Sample Size Calculation of REDUCE‐MVI Trial.

Data S3. Complete Overview of the Statistical Analysis Methods.

Table S1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria of the REDUCE‐MVI Trial

Table S2. Baseline Characteristics of Total Study Population at the Index Event

Table S3. Procedural Characteristics of Total Study Population at the Index Event

Table S4. Per‐Protocol Analysis of Patient Characteristics at 1‐Year Follow‐Up

Table S5. Reasons for Switch of Initial Randomized P2Y12 Treatment Strategy

Table S6. Reasons for Hospitalization

Table S7. Per‐Protocol Analysis of Patient Symptoms and Clinical Outcome

Table S8. Relative Between‐Group Difference and Risk in Discrete Outcomes

Figure S1. Study flowchart of patients included in the per‐protocol analysis.

Figure S2. Improvement in peripheral endothelial function over time in the total study population. Peripheral endothelial function and improvement in peripheral endothelial function at different time points. In the ITT analysis (A), all patients were included (n=108). In the per‐protocol analysis (B), we included 77 patients (ticagrelor n=36 vs. prasugrel n=41) who did not switch or stop with their initial randomized P2Y12 inhibition therapy before 1‐year follow‐up and who additionally did not receive P2Y12 inhibition therapy at 1.5‐year follow‐up. The dashed line represents the established cutoff value for decreased peripheral endothelial function (RHI <1.67 equals the natural logarithm RHI <0.51). The line in the boxplots indicates the median and the cross indicates the mean. The increase in RHI over time was calculated using a mixed‐model analysis including time as main effect. ITT indicates intention to treat; PP, per protocol; RHI, reactive hyperemia index.

Figure S3. Per‐protocol analysis of peripheral endothelial function. Peripheral endothelial function and improvement in peripheral endothelial function in patients randomized to ticagrelor vs. prasugrel maintenance therapy. In the per‐protocol analysis, we included 77 patients (ticagrelor n=36 vs. prasugrel n=41) who did not switch or stop with their initial randomized P2Y12 inhibition therapy before 1‐year follow‐up and who additionally did not receive P2Y12 inhibition therapy at 1.5‐year follow‐up. The dashed line represents the established cutoff value for decreased peripheral endothelial function (RHI <1.67 equals the natural logarithm RHI <0.51). The line in the boxplots indicates the median, and the cross indicates the mean. The increase in RHI over time was calculated using a mixed‐model analysis including time as main effect. RHI indicates reactive hyperemia index.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014411 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014411.)

References

- 1. Neumann FJ, Sousa‐Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Falk V, Head SJ, Juni P, Kastrati A, Koller A, Kristensen SD, Niebauer J, Richter DJ, Seferovic PM, Sibbing D, Stefanini GG, Windecker S, Yadav R, Zembala MO. [2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization]. Eur Heart J. 2018;76:1585–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Teunissen PF, de Waard GA, Hollander MR, Robbers LF, Danad I, Biesbroek PS, Amier RP, Echavarria‐Pinto M, Quiros A, Broyd C, Heymans MW, Nijveldt R, Lammertsma AA, Raijmakers PG, Allaart CP, Lemkes JS, Appelman YE, Marques KM, Bronzwaer JG, Horrevoets AJ, van Rossum AC, Escaned J, Beek AM, Knaapen P, van Royen N. Doppler‐derived intracoronary physiology indices predict the occurrence of microvascular injury and microvascular perfusion deficits after angiographically successful primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:e001786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Waard GA, Fahrni G, de Wit D, Kitabata H, Williams R, Patel N, Teunissen PF, van de Ven PM, Umman S, Knaapen P, Perera D, Akasaka T, Sezer M, Kharbanda RK, van Royen N; Oxford Acute Myocardial Infarction Study investigators . Hyperaemic microvascular resistance predicts clinical outcome and microvascular injury after myocardial infarction. Heart. 2018;104:127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bonello L, Laine M, Kipson N, Mancini J, Helal O, Fromonot J, Gariboldi V, Condo J, Thuny F, Frere C, Camoin‐Jau L, Paganelli F, Dignat‐George F, Guieu R. Ticagrelor increases adenosine plasma concentration in patients with an acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:872–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cattaneo M, Schulz R, Nylander S. Adenosine‐mediated effects of ticagrelor: evidence and potential clinical relevance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2503–2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wittfeldt A, Emanuelsson H, Brandrup‐Wognsen G, van Giezen JJ, Jonasson J, Nylander S, Gan LM. Ticagrelor enhances adenosine‐induced coronary vasodilatory responses in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:723–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Armstrong D, Summers C, Ewart L, Nylander S, Sidaway JE, van Giezen JJ. Characterization of the adenosine pharmacology of ticagrelor reveals therapeutically relevant inhibition of equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19:209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Leeuwen MAH, van der Hoeven NW, Janssens GN, Everaars H, Nap A, Lemkes JS, de Waard GA, van de Ven PM, van Rossum AC, Ten Cate TJF, Piek JJ, von Birgelen C, Escaned J, Valgimigli M, Diletti R, Riksen NP, van Mieghem NM, Nijveldt R, van Royen N. Evaluation of microvascular injury in revascularized patients with ST‐segment‐elevation myocardial infarction treated with ticagrelor versus prasugrel. Circulation. 2019;139:636–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Torngren K, Ohman J, Salmi H, Larsson J, Erlinge D. Ticagrelor improves peripheral arterial function in patients with a previous acute coronary syndrome. Cardiology. 2013;124:252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Janssens GN, van Leeuwen MA, van der Hoeven NW, de Waard GA, Nijveldt R, Diletti R, Zijlstra F, von Birgelen C, Escaned J, Valgimigli M, van Royen N. Reducing microvascular dysfunction in revascularized patients with st‐elevation myocardial infarction by off‐target properties of ticagrelor versus prasugrel. Rationale and design of the REDUCE‐MVI study. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2016;9:249–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alexopoulos D, Xanthopoulou I, Gkizas V, Kassimis G, Theodoropoulos KC, Makris G, Koutsogiannis N, Damelou A, Tsigkas G, Davlouros P, Hahalis G. Randomized assessment of ticagrelor versus prasugrel antiplatelet effects in patients with ST‐segment‐elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:797–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tantry US, Bonello L, Aradi D, Price MJ, Jeong YH, Angiolillo DJ, Stone GW, Curzen N, Geisler T, Ten Berg J, Kirtane A, Siller‐Matula J, Mahla E, Becker RC, Bhatt DL, Waksman R, Rao SV, Alexopoulos D, Marcucci R, Reny JL, Trenk D, Sibbing D, Gurbel PA; Working Group on On‐Treatment Platelet Reactivity . Consensus and update on the definition of on‐treatment platelet reactivity to adenosine diphosphate associated with ischemia and bleeding. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:2261–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sibbing D, Aradi D, Alexopoulos D, Ten Berg J, Bhatt DL, Bonello L, Collet JP, Cuisset T, Franchi F, Gross L, Gurbel P, Jeong YH, Mehran R, Moliterno DJ, Neumann FJ, Pereira NL, Price MJ, Sabatine MS, So DYF, Stone GW, Storey RF, Tantry U, Trenk D, Valgimigli M, Waksman R, Angiolillo DJ. Updated expert consensus statement on platelet function and genetic testing for guiding P2Y12 receptor inhibitor treatment in percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1521–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Campo G, Parrinello G, Ferraresi P, Lunghi B, Tebaldi M, Miccoli M, Marchesini J, Bernardi F, Ferrari R, Valgimigli M. Prospective evaluation of on‐clopidogrel platelet reactivity over time in patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention relationship with gene polymorphisms and clinical outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2474–2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aradi D, Kirtane A, Bonello L, Gurbel PA, Tantry US, Huber K, Freynhofer MK, ten Berg J, Janssen P, Angiolillo DJ, Siller‐Matula JM, Marcucci R, Patti G, Mangiacapra F, Valgimigli M, Morel O, Palmerini T, Price MJ, Cuisset T, Kastrati A, Stone GW, Sibbing D. Bleeding and stent thrombosis on P2Y12‐inhibitors: collaborative analysis on the role of platelet reactivity for risk stratification after percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1762–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bonetti PO, Pumper GM, Higano ST, Holmes DR Jr, Kuvin JT, Lerman A. Noninvasive identification of patients with early coronary atherosclerosis by assessment of digital reactive hyperemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2137–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matsuzawa Y, Sugiyama S, Sumida H, Sugamura K, Nozaki T, Ohba K, Matsubara J, Kurokawa H, Fujisue K, Konishi M, Akiyama E, Suzuki H, Nagayoshi Y, Yamamuro M, Sakamoto K, Iwashita S, Jinnouchi H, Taguri M, Morita S, Matsui K, Kimura K, Umemura S, Ogawa H. Peripheral endothelial function and cardiovascular events in high‐risk patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bonetti PO, Barsness GW, Keelan PC, Schnell TI, Pumper GM, Kuvin JT, Schnall RP, Holmes DR, Higano ST, Lerman A. Enhanced external counterpulsation improves endothelial function in patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1761–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, Kaul S, Wiviott SD, Menon V, Nikolsky E, Serebruany V, Valgimigli M, Vranckx P, Taggart D, Sabik JF, Cutlip DE, Krucoff MW, Ohman EM, Steg PG, White H. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Motovska Z, Hlinomaz O, Miklik R, Hromadka M, Varvarovsky I, Dusek J, Knot J, Jarkovsky J, Kala P, Rokyta R, Tousek F, Kramarikova P, Majtan B, Simek S, Branny M, Mrozek J, Cervinka P, Ostransky J, Widimsky P; PRAGUE‐18 Study Group . Prasugrel versus ticagrelor in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: multicenter randomized PRAGUE‐18 study. Circulation. 2016;134:1603–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lhermusier T, Lipinski MJ, Tantry US, Escarcega RO, Baker N, Bliden KP, Magalhaes MA, Ota H, Tian W, Pendyala L, Minha S, Chen F, Torguson R, Gurbel PA, Waksman R. Meta‐analysis of direct and indirect comparison of ticagrelor and prasugrel effects on platelet reactivity. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:716–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Storey RF, Husted S, Harrington RA, Heptinstall S, Wilcox RG, Peters G, Wickens M, Emanuelsson H, Gurbel P, Grande P, Cannon CP. Inhibition of platelet aggregation by AZD6140, a reversible oral P2Y12 receptor antagonist, compared with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1852–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schomig A. Ticagrelor–is there need for a new player in the antiplatelet‐therapy field? N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1108–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nylander S, Femia EA, Scavone M, Berntsson P, Asztely AK, Nelander K, Lofgren L, Nilsson RG, Cattaneo M. Ticagrelor inhibits human platelet aggregation via adenosine in addition to P2Y12 antagonism. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1867–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Perl L, Zemer‐Wassercug N, Rechavia E, Vaduganathan M, Orvin K, Weissler‐Snir A, Lerman‐Shivek H, Kornowski R, Lev EI. Comparison of platelet inhibition by prasugrel versus ticagrelor over time in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;39:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Franchi F, Rollini F, Aggarwal N, Hu J, Kureti M, Durairaj A, Duarte VE, Cho JR, Been L, Zenni MM, Bass TA, Angiolillo DJ. Pharmacodynamic comparison of prasugrel versus ticagrelor in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease: the OPTIMUS (Optimizing Antiplatelet Therapy in Diabetes Mellitus)‐4 study. Circulation. 2016;134:780–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schupke S, Neumann FJ, Menichelli M, Mayer K, Bernlochner I, Wohrle J, Richardt G, Liebetrau C, Witzenbichler B, Antoniucci D, Akin I, Bott‐Flugel L, Fischer M, Landmesser U, Katus HA, Sibbing D, Seyfarth M, Janisch M, Boncompagni D, Hilz R, Rottbauer W, Okrojek R, Mollmann H, Hochholzer W, Migliorini A, Cassese S, Mollo P, Xhepa E, Kufner S, Strehle A, Leggewie S, Allali A, Ndrepepa G, Schuhlen H, Angiolillo DJ, Hamm CW, Hapfelmeier A, Tolg R, Trenk D, Schunkert H, Laugwitz KL, Kastrati A; ISAR‐REACT 5 Trial Investigators . Ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1524–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bernlochner I, Goedel A, Plischke C, Schupke S, Haller B, Schulz C, Mayer K, Morath T, Braun S, Schunkert H, Siess W, Kastrati A, Laugwitz KL. Impact of immature platelets on platelet response to ticagrelor and prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3202–3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Becatti M, Fiorillo C, Gori AM, Marcucci R, Paniccia R, Giusti B, Violi F, Pignatelli P, Gensini GF, Abbate R. Platelet and leukocyte ROS production and lipoperoxidation are associated with high platelet reactivity in Non‐ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients on dual antiplatelet treatment. Atherosclerosis. 2013;231:392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Hiatt BL, O'Connor CM. Clopidogrel for coronary stenting: response variability, drug resistance, and the effect of pretreatment platelet reactivity. Circulation. 2003;107:2908–2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Weisz G, Rinaldi MJ, Neumann FJ, Metzger DC, Henry TD, Cox DA, Duffy PL, Mazzaferri E, Gurbel PA, Xu K, Parise H, Kirtane AJ, Brodie BR, Mehran R, Stuckey TD; ADAPT‐DES Investigators . Platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes after coronary artery implantation of drug‐eluting stents (ADAPT‐DES): a prospective multicentre registry study. Lancet. 2013;382:614–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bonello L, Pansieri M, Mancini J, Bonello R, Maillard L, Barnay P, Rossi P, Ait‐Mokhtar O, Jouve B, Collet F, Peyre JP, Wittenberg O, de Labriolle A, Camilleri E, Cheneau E, Cabassome E, Dignat‐George F, Camoin‐Jau L, Paganelli F. High on‐treatment platelet reactivity after prasugrel loading dose and cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention in acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lynch DR Jr, Khan FH, Vaidya D, Williams MS. Persistent high on‐treatment platelet reactivity in acute coronary syndrome. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012;33:267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jin HY, Yang TH, Kim DI, Chung SR, Seo JS, Jang JS, Kim DK, Kim DK, Kim KH, Seol SH, Nam CW, Hur SH, Kim W, Park JS, Kim YJ, Kim DS. High post‐clopidogrel platelet reactivity assessed by a point‐of‐care assay predicts long‐term clinical outcomes in patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction who underwent primary coronary stenting. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1877–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Anderson TJ, Uehata A, Gerhard MD, Meredith IT, Knab S, Delagrange D, Lieberman EH, Ganz P, Creager MA, Yeung AC, Selwyn AP. Close relation of endothelial function in the human coronary and peripheral circulations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1235–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mallat Z, Benamer H, Hugel B, Benessiano J, Steg PG, Freyssinet JM, Tedgui A. Elevated levels of shed membrane microparticles with procoagulant potential in the peripheral circulating blood of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2000;101:841–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jeong HS, Hong SJ, Cho SA, Kim JH, Cho JY, Lee SH, Joo HJ, Park JH, Yu CW, Lim DS. Comparison of ticagrelor versus prasugrel for inflammation, vascular function, and circulating endothelial progenitor cells in diabetic patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndrome requiring coronary stenting: a prospective, randomized, crossover trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:1646–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ariotti S, Ortega‐Paz L, van Leeuwen M, Brugaletta S, Leonardi S, Akkerhuis KM, Rimoldi SF, Janssens G, Gianni U, van den Berge JC, Karagiannis A, Windecker S, Valgimigli M; HI‐TECH Investigators . Effects of ticagrelor, prasugrel, or clopidogrel on endothelial function and other vascular biomarkers: a randomized crossover study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:1576–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ohman J, Kudira R, Albinsson S, Olde B, Erlinge D. Ticagrelor induces adenosine triphosphate release from human red blood cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;418:754–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Erlinge D, Burnstock G. P2 receptors in cardiovascular regulation and disease. Purinergic Signal. 2008;4:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yada T, Shimokawa H, Hiramatsu O, Kajita T, Shigeto F, Goto M, Ogasawara Y, Kajiya F. Hydrogen peroxide, an endogenous endothelium‐derived hyperpolarizing factor, plays an important role in coronary autoregulation in vivo. Circulation. 2003;107:1040–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Belardinelli L, Shryock JC, Snowdy S, Zhang Y, Monopoli A, Lozza G, Ongini E, Olsson RA, Dennis DM. The A2A adenosine receptor mediates coronary vasodilation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:1066–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Storey RF, Becker RC, Harrington RA, Husted S, James SK, Cools F, Steg PG, Khurmi NS, Emanuelsson H, Cooper A, Cairns R, Cannon CP, Wallentin L. Characterization of dyspnoea in PLATO study patients treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel and its association with clinical outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2945–2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Storey RF, Bliden KP, Patil SB, Karunakaran A, Ecob R, Butler K, Teng R, Wei C, Tantry US, Gurbel PA; ONSET/OFFSET Investigators . Incidence of dyspnea and assessment of cardiac and pulmonary function in patients with stable coronary artery disease receiving ticagrelor, clopidogrel, or placebo in the ONSET/OFFSET study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, Brennan JM, Redberg RF, Anderson HV, Brindis RG, Douglas PS. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:886–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dimitroulis D, Golabkesh M, Naguib D, Knoop B, Dannenberg L, Helten C, Pohl M, Jung C, Kelm M, Zeus T, Polzin A. Safety and efficacy in prasugrel‐ versus ticagrelor‐treated patients with ST‐elevation myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2018;72:186–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, Neumann FJ, Ardissino D, De Servi S, Murphy SA, Riesmeyer J, Weerakkody G, Gibson CM, Antman EM; TRITON‐TIMI 38 Investigators . Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2001–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, Horrow J, Husted S, James S, Katus H, Mahaffey KW, Scirica BM, Skene A, Steg PG, Storey RF, Harrington RA; PLATO Investigators , Freij A, Thorsen M. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Methods and Scores for Patient Symptom Assessment.

Data S2. Sample Size Calculation of REDUCE‐MVI Trial.

Data S3. Complete Overview of the Statistical Analysis Methods.

Table S1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria of the REDUCE‐MVI Trial

Table S2. Baseline Characteristics of Total Study Population at the Index Event

Table S3. Procedural Characteristics of Total Study Population at the Index Event

Table S4. Per‐Protocol Analysis of Patient Characteristics at 1‐Year Follow‐Up

Table S5. Reasons for Switch of Initial Randomized P2Y12 Treatment Strategy

Table S6. Reasons for Hospitalization

Table S7. Per‐Protocol Analysis of Patient Symptoms and Clinical Outcome

Table S8. Relative Between‐Group Difference and Risk in Discrete Outcomes

Figure S1. Study flowchart of patients included in the per‐protocol analysis.

Figure S2. Improvement in peripheral endothelial function over time in the total study population. Peripheral endothelial function and improvement in peripheral endothelial function at different time points. In the ITT analysis (A), all patients were included (n=108). In the per‐protocol analysis (B), we included 77 patients (ticagrelor n=36 vs. prasugrel n=41) who did not switch or stop with their initial randomized P2Y12 inhibition therapy before 1‐year follow‐up and who additionally did not receive P2Y12 inhibition therapy at 1.5‐year follow‐up. The dashed line represents the established cutoff value for decreased peripheral endothelial function (RHI <1.67 equals the natural logarithm RHI <0.51). The line in the boxplots indicates the median and the cross indicates the mean. The increase in RHI over time was calculated using a mixed‐model analysis including time as main effect. ITT indicates intention to treat; PP, per protocol; RHI, reactive hyperemia index.

Figure S3. Per‐protocol analysis of peripheral endothelial function. Peripheral endothelial function and improvement in peripheral endothelial function in patients randomized to ticagrelor vs. prasugrel maintenance therapy. In the per‐protocol analysis, we included 77 patients (ticagrelor n=36 vs. prasugrel n=41) who did not switch or stop with their initial randomized P2Y12 inhibition therapy before 1‐year follow‐up and who additionally did not receive P2Y12 inhibition therapy at 1.5‐year follow‐up. The dashed line represents the established cutoff value for decreased peripheral endothelial function (RHI <1.67 equals the natural logarithm RHI <0.51). The line in the boxplots indicates the median, and the cross indicates the mean. The increase in RHI over time was calculated using a mixed‐model analysis including time as main effect. RHI indicates reactive hyperemia index.