Abstract

Objective

Trunk exoskeletons are a new technology with great promise for human rehabilitation, assistance and augmentation. However, it is unclear how different exoskeleton features affect the wearer’s body during different activities. This study thus examined how varying a trunk exoskeleton’s thoracic and abdominal compression affects trunk kinematics and muscle demand during several activities.

Methods

We developed a trunk exoskeleton that allows thoracic and abdominal compression to be changed quickly and independently. To evaluate the effect of varying compression, 12 participants took part in a two-session study. In the first session, they performed three activities (walking, sit-to-stand, lifting a box). In the second session, they experienced unexpected perturbations while sitting. This was done both without the exoskeleton and in four exoskeleton configurations with different thoracic and abdominal compression levels. Trunk flexion angle, low back extension moment and the electromyogram of the erector spinae and rectus abdominis were measured in both sessions.

Results

Different exoskeleton compression levels resulted in significantly different peak trunk flexion angles and peak electromyograms of the erector spinae. However, the effects of compression differed significantly between activities.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that a trunk exoskeleton’s thoracic and abdominal compression affect the wearer’s kinematics and muscle demand; furthermore, a single compression configuration is not appropriate for all activities.

Significance

The study suggests that future trunk exoskeletons should either be able to vary their compression levels to suit different activities or should have the compression designed for a specific activity in order to be beneficial to the wearer.

Keywords: electromyography, ergonomics, exoskeletons, human kinematics, orthoses, spine, trunk

I. INTRODUCTION

Trunk exoskeletons are a relatively new technology with enormous promise for human rehabilitation, assistance and augmentation. By reducing the load on the spine and guiding trunk motion, such exoskeletons could potentially reduce back pain and improve stability in people with spinal injuries [1]–[4]. As low back pain is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide [5], [6] and since surgical and pharmaceutical solutions are only recommended for extreme cases [7], [8], trunk exoskeletons thus have the potential to improve quality of life for millions of people. Furthermore, motors added to the exoskeleton could assist with lifting heavier loads, thus augmenting the capabilities of workers in physically demanding professions [9]–[11].

A. Mechanical Design of Trunk Exoskeletons

The mechanical design of a trunk exoskeleton has a major effect on the user’s experience, as evidenced by previous studies of passive rigid spinal orthoses (braces). Those studies have consistently found that different spinal orthosis designs have different effects on the body, though it is unclear just how specific mechanical elements affect the user [12]–[16]. A similar result was recently observed in a comparison of two different trunk exoskeleton designs, again with no clear understanding of what specific elements were responsible for the differences [2]. Furthermore, the effects of spinal orthoses are known to vary between different activities: for example, an orthosis that restricts sagittal motion across the L4-S1 segments during standing flexion may increase sagittal motion at these spinal levels during walking [17]. A similar result was recently observed in a passive trunk exoskeleton, which was found to be effective for some tasks but not others [18]. Finally, any benefits of a specific design during a particular activity may have corresponding drawbacks within the same activity: for example, an analysis of multiple off-the-shelf spinal orthoses meant to limit intervertebral motion found that the orthoses were able to limit motion during flexion at L3/4 and L4/5 levels, but not at the L5-S1 level, a common site for low back pain [16].

To enable more effective development and deployment of future trunk exoskeletons, it is critical to determine how different exoskeleton features affect the body during different activities. Developers could use this information to design an exoskeleton to maximally benefit a specific activity such as lifting; alternatively, they could create an exoskeleton whose mechanical features (e.g. stiffness) can be manually adjusted by the wearer. Equipped with knowledge about what settings are appropriate for a particular activity, the wearer could then manually adjust the exoskeleton to suit their current activity. A prototype of such a trunk exoskeleton with adjustable mechanical components was previously presented by Park et al. [19], though they used it to measure trunk stiffness rather than assist the wearer. In the long term, a trunk exoskeleton could even be equipped with sensors and actuators to automatically detect the current activity and automatically reconfigure the exoskeleton into a mechanical configuration that would be appropriate for that activity.

B. Our Reconfigurable Trunk Exoskeleton

Our research group recently developed a modular reconfigurable trunk exoskeleton whose spinal column stiffness and trunk compression can be independently changed at multiple spinal levels. Furthermore, the length and angle of many other device elements can be modified to enable a better anatomical fit to the user, and individual elements can be easily removed and replaced with different ones. We believe that this reconfigurable device represents a potentially valuable research platform, as it allows multiple mechanical characteristics to be independently studied. For example, stiffness is believed to be responsible for differences in effects of different spinal orthoses [13], [16] and trunk exoskeletons [2], but has never been systematically evaluated; it could be easily studied with our device by independently changing stiffness at different spinal levels. Similarly, the human-exoskeleton interface (i.e., the way the device grips the wearer) is likely to have a critical effect on wearer comfort and exoskeleton displacement, and this could be systematically studied by removing and replacing individual modular gripper elements. Similar modular reconfigurable approaches have been proposed for studying mechanical properties of lower limb exoskeletons [20], and have the potential to provide generalizable knowledge that would apply to all trunk exoskeletons.

Our 2018 conference paper [21] previously briefly described the exoskeleton and conducted a single-subject study of trunk compression, identifying it as a promising mechanical characteristic for further evaluation. In the current paper, we describe the mechanical design of our reconfigurable trunk exoskeleton in detail as well as conduct a pilot 12-subject study of the effects of independently varying thoracic and abdominal trunk compression during different activities. While our results are obtained with a single specific exoskeleton, we believe that information about thoracic and abdominal compression is generalizable to all trunk exoskeletons; furthermore, the principle of easily and independently reconfigurable components could be implemented in all other exoskeletons, allowing them to be adjusted to a specific wearer or activity.

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. Participants

Eighteen individuals with no history of chronic low back pain or back injury volunteered for the study and attended the initial screening session. 6 individuals did not fit the exoskeleton comfortably (either because they were too short/tall or because their chest was too broad) and were thus excluded, resulting in 12 valid participants (11 male, 1 female). They were 28 ± 12 (mean ± standard deviation) years old (range: 20–64 years old), with a height of 183.5 ± 4.0 cm (range: 175–188 cm) and weight of 82 ± 8 kg (range: 66 to 93 kg).

B. Trunk Exoskeleton

The exoskeleton used in our research (Fig. 1) is a variableresistance exoskeletal thoracic-lumbar-sacral orthosis that weighs approximately 2.5 kg. It consists of multiple sections: an exoskeletal spinal column, trunk-grasping end-effectors, thoracic and abdominal front modules, and elastic straps that connect the front modules to the end-effectors.

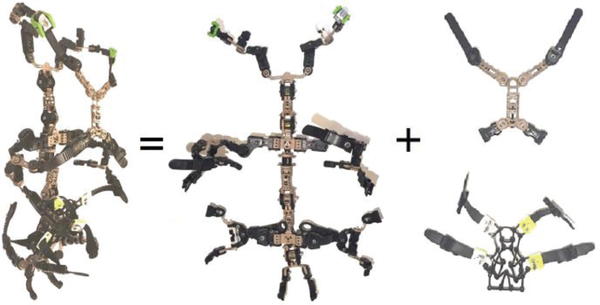

Fig. 1.

The trunk exoskeleton used in our research. Left: full device. Center: spinal column with trunk-grasping end-effectors. Right: thoracic and abdominal front sections, which attach to the end-effectors using adjustable straps. Figure reused from Johnson et al. [21].

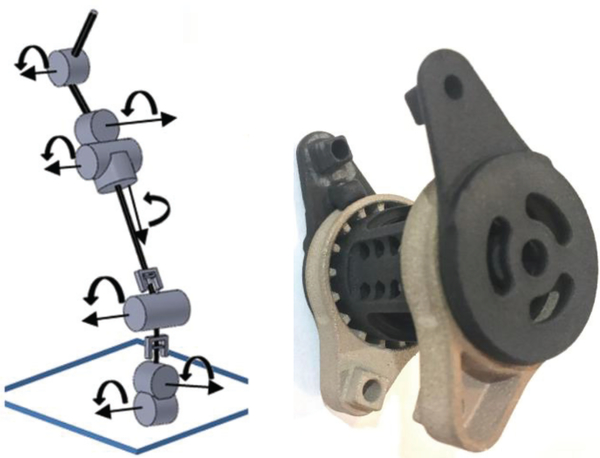

The reconfigurable articulated exoskeletal spinal column (Fig. 1, center) was designed to be easily adjustable and facilitate selected variable resistance (damping and friction) along the posterior of the torso. The main components of the column incorporate seven variable-segment axial (sagittal, transverse, longitudinal) resistance couplings as well as variable angular couplings. Of the seven couplings, three are located at the T12-L1 level, two at the L5-S1 level, and one each at the L2-L3 and T7-T8 levels (Fig. 2). These levels correspond to regional lateral-bending and axialrotation coupling locations, allowing effective stabilization of the torso. Curvic couplings (similar to Hirth couplings, but with curved teeth) integrated within the coupling assemblies allow selection of the angle between adjacent segments. A viscoelastic coupling [22] allows independent control of each joint’s stiffness while avoiding the vibrational effects typically exerted along the spine by standard elastic springs. Each coupling consists of an external ‘stator’, an internal ‘rotor’, and multi-node spoked springs that connect the stator and rotor. Neither the stator nor rotor is electrically powered, though the rotor can be moved relative to the stator by applying external forces to the spinal column. Each coupling also includes a ratcheting mechanism that allows the nodes to be deformed and the spoked springs to be preloaded using a simple screwdriver, thus adjusting the stiffness of each coupling independently. For purposes of the current study, which focused on varying trunk compression, the properties of all 7 coupling assemblies were constant, with each coupling having a moment of resistance of 4.7 N·m, a torsional stiffness of 180 N·m/rad, and a viscosity of 1350 Pa·s.

Fig. 2.

Left: schematic of the spinal column’s segments and viscoelastic couplings. Right: close-up picture of a coupling assembly. Figure reused from Johnson et al. [21].

A schematic of the spinal column’s couplings and segments as well as a detailed picture of a coupling assembly are shown in Fig. 2. The couplings and connecting segments are made of a combination of 3D-printed metal and nylon components and are surrounded by a flexible housing. This housing is a combination of 90A urethane, viscoelastic material (sorbothane) and foam (similar to that used in shoe insoles). This flexible material is used at points where the device is attached to the body. Furthermore, rigid segments of the device conform to bony landmarks, and padding is used to distribute the device load. The design avoids areas where point loading could lead to puncture. Finally, lead screw mechanisms allow the distances between adjacent couplings to be modified in order to accommodate the individual wearer. The current exoskeleton prototype can thus be comfortably worn by participants who are approximately 174–188 cm tall.

Multiple trunk-grasping end-effectors in the shape of compliant multi-digit grippers are attached to the spinal column (Fig. 1, center). Instead of actuating each digit, interlocking joints were devised to allow manual adjustment of each digit’s position to grasp torsos of different sizes; furthermore, the end-effectors are padded with silicone and foam for safety and comfort. Finally, each end-effector can be independently removed and replaced with a different one, though this was not done in the current study.

The trunk-grasping end-effectors connect to front parts of the exoskeleton using detachable straps (Fig. 1, right). The abdominal front section of the exoskeleton is a webbing that encompasses and compresses the abdominal region. It connects to the grippers located at the iliac crest and lumbar-thoracic borders, and interchangeable webbings of different sizes were developed to accommodate large variations in stomach size. The thoracic section is an anterolateral module connected to the grippers at the trapezium and T12-L1 levels; it provides a function analogous to a thoracic cage. A sternal-clavicular assembly with an adjustable size and geometry provides a comfortable and secure fit on sternums and clavicles of multiple sizes. The assembly’s length and the angle of its clavicular digits can be modified and locked in position, and the axis of the assembly can be aligned with the axis of the manubrium. Varying the distance between the sternal-clavicular and xiphoid process sections allows for improved comfort and secure mechanical locking with the tensionable chondral digits. These digits are located along the intersection of the thoracic-lumbar region and partially rest on the lowest ribs of the torso.

Finally, adjustable straps between the thoracic/abdominal front modules and the spinal-column-mounted grippers provide independently adjustable compression in the thoracic and abdominal regions. The effects of this thoracic and abdominal compression were evaluated in the present study. To reduce slippage, we used ladder straps threaded through ratchet buckles.

The trunk exoskeleton is not intended as a replacement for existing back support exoskeletons that use motors on the thighs or upper arms to augment the body (e.g. the exoskeleton of Toxiri et al. [11]). Rather, we believe that future exoskeletons should incorporate both reconfigurable trunk elements (spinal column stiffness, trunk compression and others) and active motors on the arms and legs. Therefore, we have already designed attachment points for a future thigh module, though they were not included in the present study.

C. Study Protocol

The protocol was approved by the University of Wyoming Institutional Review Board (protocol #20160607AB01212), and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Each participant first attended a screening session to ensure that they could wear the exoskeleton comfortably. During this session, the purpose and procedure of the study were also explained, and each participant signed an informed consent form. If the participant was able to wear the exoskeleton comfortably and agreed to continue the study, they took part in two study sessions on two different days. A participant wearing the exoskeleton and attached sensors is shown in Fig. 3.

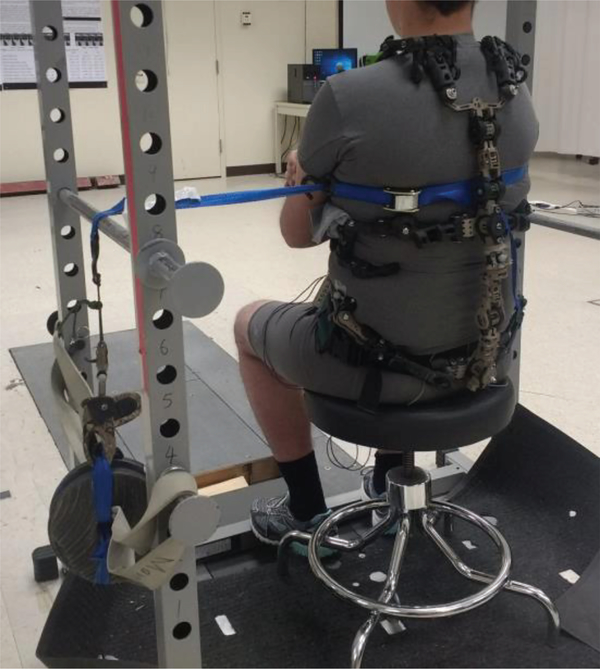

Fig. 3.

Front and back views of a participant wearing the trunk exoskeleton and sensors.

Both study sessions were conducted in the Biomechanics Laboratory of the University of Wyoming, and both involved wearing the trunk exoskeleton in four different compression conditions: low thoracic and low abdominal compression (LT-LA), low thoracic and high abdominal compression (LT-HA), high thoracic and low abdominal compression (HT-LA), and high thoracic and high abdominal compression (HT-HA). While the exoskeleton allows many possible levels of both thoracic and abdominal compression, two discrete levels were selected in order to allow a systematic experiment with a reasonable session duration. Both high and low compression were set differently for each participant depending on that participant’s subjective perception. Low compression was the lowest that could be perceived by the participant as pressure; it was set by loosening the exoskeleton’s straps as much as possible, then gradually tightening them (in increments of one “tooth” on the ladder strap that connects the front module to the spinal-column-mounted gripper) and asking the participant to verbally report when they perceived pressure on the thorax or abdomen. High compression was the highest that was still comfortable for the participant; it was set by gradually tightening the straps (as above) until the participant reported discomfort in the thorax or abdomen, then loosening the straps again until the participant reported that the discomfort had disappeared. This procedure was done separately for the thoracic and abdominal module in order to vary thoracic and abdominal compression.

1). Session 1: Walking, Lifting, Sit-to-Stand

In the first study session, participants were asked to complete three activities of daily life without the trunk exoskeleton and with the trunk exoskeleton in all four compression conditions. The three activities were:

Walking: Starting at one end of the laboratory, participants walked at their preferred pace in a straight line across the laboratory, head facing forward.

Sit-to-stand: Participants stood up from an initial sitting position on a padded stool. For each participant, the stool height was adjusted so that they initially sat with their knees bent at approximately a 90-degree angle, their thighs parallel to the ground, and their feet forward.

Lifting: A 20-pound (9.1 kg) box was placed on the floor in front of the participants. Starting from a standing position approximately 30 cm away from the box, participants picked up the box with both arms and lifted it to approximately waist level. No specific lifting strategy was prescribed.

The five conditions (no exoskeleton, LT-LA, LT-HA, HTLA, HT-HA) were performed in random order that differed among participants. The “no exoskeleton” condition was always first or last so that participants only had to put the exoskeleton on and off once. At the end of the session, a maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) test of the erector spinae muscles was done by having the participant lie on their stomach and try to lift their upper body (without using their arms) as much as possible for 5 s while an experimenter pushed down on the participant’s shoulders with a steady force. Then, an MVC test of the rectus abdominis muscles was performed by having the participant lie on their back and again try to lift their upper body for 5 s while an experimenter pushed back against them.

2). Session 2: Response to perturbations

In the second study session, the effect of the exoskeleton on the wearer’s stability was evaluated using a protocol similar to one previously used to predict knee injury [23]. As in the first session, the protocol was performed in five conditions (no exoskeleton, LT-LT, LT-HA, HT-LA, HT-HA). The order of conditions was random, with the “no exoskeleton” condition always first or last. At the end of the session, an MVC test was performed in the same way as in the first session.

The protocol within each of the five conditions was as follows: Participants sat on a padded stool, and a rope was tied around their upper trunk at armpit height. The rope was led over a metal bar (which was at the same height as the rope) and then attached to a 20-pound (9.1 kg) weight. The rope was thus horizontal from the participant to the bar and vertical from the bar to the weight. A photo of the study setup is shown in Fig. 4. For each trial, the participant first resisted the pull of the rope with their eyes closed for 5–10 seconds. At a randomly chosen moment, the rope was then disconnected from the weight using a mechanical release aid (originally used for archery). The participant was not informed about the timing of the release and thus experienced an unexpected perturbation for which they had to compensate. This was performed four times: with the rope and weight attached from the front, back, left or right side in order to induce perturbations from different directions. The order of the four directions was random.

Fig. 4.

Experiment setup used to evaluate participants’ responses to unexpected perturbations. Participants sit on a stool with their eyes closed and resist the pull of the weight attached to them via a rope. The weight is then unexpectedly released from the rope.

D. Measurements and Signal Processing

Eight Vicon Bonita optical cameras (Vicon Motion Systems, UK) and retroreflective markers were used to track the participant’s trunk kinematics as well as the position of relevant objects at a sampling frequency of 160 Hz. In the first session (which involved full-body motions), the markers were placed on the participant’s prominent anatomical landmarks (vertex, gonions, acromioclavicular joints, olecranon processes, midpoints of radial and ulnar styloid processes, third metacarpal heads, anterior superior iliac spines, posterior superior iliac spines, iliac crests and heels); furthermore, a marker was placed on the estimated center of mass of the exoskeleton and two markers were placed on the box that the participant had to lift. In the second session (where participants remained in a sitting position), two markers were placed on the anterior superior iliac spines and two were placed on the acromioclavicular joints; furthermore, one marker was attached to the weight to measure the exact time of perturbation. To evaluate muscle demand, the electromyograms (EMG) of the left and right erector spinae as well as left and right rectus abdominis were measured at a sampling frequency of 2 kHz using the Delsys Myomonitor wireless EMG system (Delsys Inc., MA). Bipolar electrodes were placed at L3 height, approximately 4 cm left and right from the midline of the spine, and 3 cm from the midline of the abdomen and 2 cm above the umbilicus. EMG measurement did not vary between sessions.

In both sessions, signals were manually segmented into individual trials (activity repetitions in the first session, perturbations in the second session). For the first session, a trial began when the participant started moving and ended when the participant stopped moving. For the second session, a trial began at the time of perturbation (defined as the time when the marker on the weight started dropping) and ended when the participant stopped moving. Following segmentation, the data were analyzed as follows:

EMG, both sessions: Segmented signals were first manually examined for artifacts – brief sections of the signal where the EMG amplitude was excessively high relative to the rest of the trial. If an artifact occurred at the start or end of the trial (where the participant should not be moving), that section of the trial was removed, and the rest of the trial was used for further analysis. If a possible artifact occurred in the middle of the trial where the participant was moving, that EMG channel of the entire trial was discarded; this resulted in the removal of 4 total trials (across all participants and sessions) for the EMG of the erector spinae and 7 total trials for the EMG of the rectus abdominis. Following artifact removal, segmented signals were detrended, filtered with a second-order 20–450 Hz bandpass filter and rectified. The EMG envelope was extracted by applying a second-order lowpass filter with a cutoff frequency of 10 Hz. Each envelope was normalized by the maximum value measured during the MVC test. In both sessions, the peak value of the EMG envelope was calculated for each muscle in each trial.

Kinematics, first session: A three-dimensional linked segment model was constructed from marker data using the method of Kingma et al. [24], which also allowed moments to be estimated using a top-down approach. Segment anthropometric data were estimated using the method of Leva [25]. The trunk flexion and extension angles were calculated between the upper trunk and pelvis reference frames. The peak low back extension moment and peak trunk flexion angle (from the initial standing or sitting position) were then calculated for each trial.

Kinematics, second session: The middle points of both shoulder markers and both pelvis markers were determined, and a unit vector between both middle points was calculated throughout the trial. Peak trunk deflection was calculated for each trial as the maximum displacement from the starting vector orientation; furthermore, trunk deflection was calculated 150 ms and 300 ms after each perturbation as recommended by previous research [23].

E. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted for each session and each variable separately. In the first session, repeated-measures analyses of variance (RMANOVA) were performed for each measured variable (peak values of EMG envelopes, peak low back extension moment, peak trunk flexion angle), with each RMANOVA having two within-subject factors: exoskeleton configuration (five conditions: none, LT-LA, LT-HA, HT-LA, HT-HA) and activity (three activities: walk, sit-to-stand, lift). In the second session, RMANOVA were again performed for each measured variable (peak values of EMG envelopes, peak trunk deflection, deflection after 150 ms, deflection after 300 ms), with each RMANOVA having two within-subject factors: exoskeleton configuration (five conditions as before) and direction of perturbation (four directions: front, back, left, right). Huynh-Feldt corrections were made in case of violations of sphericity, and effect size was estimated as partial eta squared (pη2). Post-hoc least significant difference tests were conducted regardless of whether RMANOVA found a significant main effect of exoskeleton configuration, and all p-values under 0.1 were reported. This procedure follows general recommendations for exploratory studies, which suggest reporting all p-values precisely regardless of significance and including effect sizes as well; p-values above 0.1 were omitted primarily due to length constraints.

III. RESULTS

All 12 participants completed all trials in both sessions. EMG data from one participant were discarded due to a nonthreatening cardiac condition that resulted in excessive electrocardiographic artefacts in the EMG. To save space, this section presents the results of the statistical tests and illustrates the most relevant results using boxplots; however, means and standard deviations of all measured variables for all conditions and both sessions are available in the Appendix. In all boxplots, whiskers indicate 10th and 90th percentiles while dots indicate individual outliers.

It should be noted that the EMG of the rectus abdominis muscles exhibited relatively poor signal quality for all participants. Electrodes for these muscles were placed close to the exoskeleton’s abdominal front section, resulting in mechanical artefacts (especially during high-flexion events such as lifting) that could not be reduced without mechanically modifying the exoskeleton. While results of the rectus abdominis EMG are nonetheless given for all participants, the low signal quality should be taken into account.

A. Session 1: Walking, Sit-to-Stand, Lifting

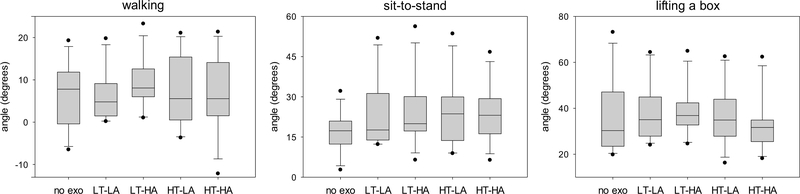

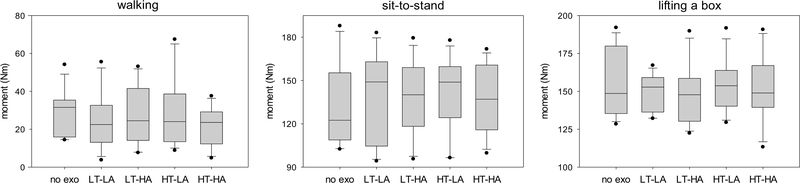

RMANOVA found a significant main effect of activity on all measured variables (p < 0.001 for all variables, pη2 ranging from 0.55 to 0.97) except for peak EMG of the right rectus abdominis (p = 0.1). There was also a significant main effect of exoskeleton configuration on peak trunk flexion angle (p = 0.014, pη2 = 0.24).

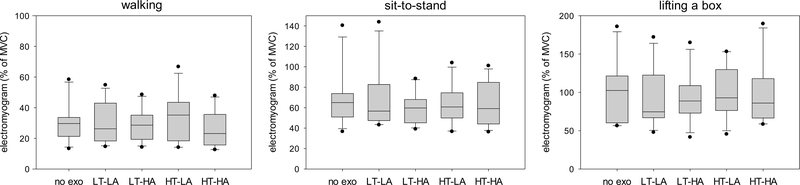

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons of exoskeleton configurations found differences in peak trunk flexion angle between no exoskeleton and LT-LA (p = 0.008), between no exoskeleton and LT-HA (p = 0.006), between no exoskeleton and HT-LA (p = 0.057), and between LT-HA and HT-HA (p = 0.028). Furthermore, post-hoc comparisons found differences in peak low back extension moment between HT-LA and HT-HA (p = 0.041). Finally, post-hoc comparisons found differences in peak EMG of the left erector spinae between LT-LA and HT-HA (p = 0.087). Due to insufficient statistical power, post-hoc comparisons of configurations were not conducted for each individual activity separately; however, boxplots of measured variables in different activities are shown in Figs. 5–7.

Fig. 5.

Peak trunk flexion angle for walking, sit-to-stand, and lifting a box during different exoskeleton configurations. No exo = no exoskeleton, LT = low thoracic compression, HT = high thoracic compression, LA = low abdominal compression, HA = high abdominal compression. Negative values indicate that the trunk was in extension throughout the trial and the peak flexion angle was thus the minimal extension angle.

Fig. 7.

Peak electromyogram of the right erector spinae for walking, sit-to-stand, and lifting a box during different exoskeleton configurations. No exo = no exoskeleton, LT = low thoracic compression, HT = high thoracic compression, LA = low abdominal compression, HA = high abdominal compression. MVC = value obtained during maximum voluntary contraction trial.

In a few cases (mainly the lifting task), peak EMG of the erector spinae exceeded 100% of the MVC value. This can be considered a weakness of the MVC protocol, which was not optimal for the erector spinae; however, we nonetheless consider it to be a useful way to normalize the EMG.

B. Session 2: Response to Perturbations

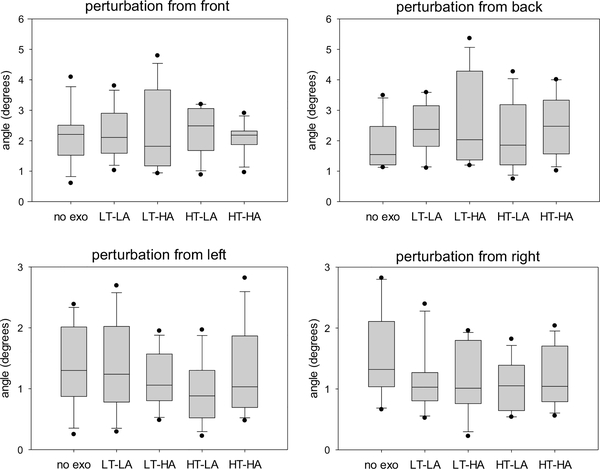

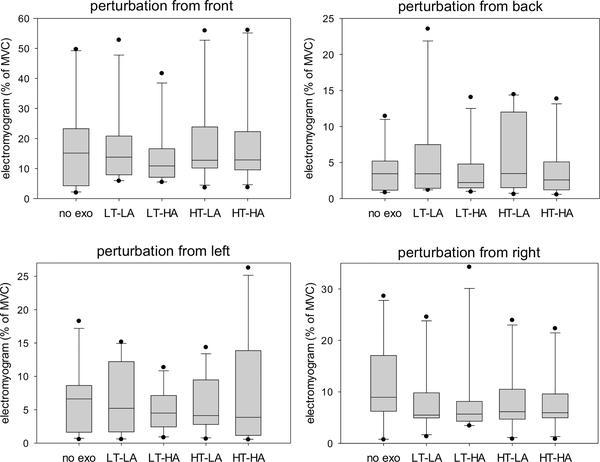

RMANOVA found a significant main effect of direction of perturbation on all three trunk deflection variables and peak EMG of both erector spinae muscles (p ranging from 0.011 to below 0.001, pη2 ranging from 0.37 to 0.76), but not peak EMG of the rectus abdominis muscles. There was also a significant main effect of exoskeleton configuration on peak trunk deflection (p = 0.014). Finally, there was a significant interaction effect (direction of perturbation * exoskeleton configuration) on peak trunk deflection (p = 0.048, pη2 = 0.22) and on trunk deflection 300 ms after the perturbation (p = 0.066, pη2 = 0.22).

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons of exoskeleton configurations found differences in trunk deflection 300 ms after the perturbation between LT-LA and HT-LA (p = 0.023) and between LT-HA and HT-LA (p = 0.078). Furthermore, post-hoc comparisons found differences in peak trunk deflection between LT-LA and HT-LA (p = 0.082). Due to insufficient statistical power, post-hoc comparisons of configurations were not conducted for each individual direction of perturbation separately; however, boxplots of measured variables are shown in Figs. 8 and 9.

Fig. 8.

Peak trunk deflection in response to perturbations from four different directions during different exoskeleton configurations. No exo = no exoskeleton, LT = low thoracic compression, HT = high thoracic compression, LA = low abdominal compression, HA = high abdominal compression.

Fig. 9.

Peak electromyogram of the left erector spinae in response to perturbations from four different directions during different exoskeleton configurations. No exo = no exoskeleton, LT = low thoracic compression, HT = high thoracic compression, LA = low abdominal compression, HA = high abdominal compression. MVC = value obtained during maximum voluntary contraction trial. Note: One extreme outlier not shown in “perturbation from back” subfigure.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Effects of Trunk Compression

Our results support the general premise that modifying trunk compression via a trunk exoskeleton can affect the wearer’s kinematics and muscle load. Simply wearing the exoskeleton appears to have some effect: for example, peak low back extension moment is lower during walking when wearing the exoskeleton than when not wearing it, regardless of trunk compression levels (Fig. 6, left); similarly, the same moment is higher during sit-to-stand motions when wearing the exoskeleton than when not wearing it, regardless of compression levels (Fig. 6, center). However, there are also notable differences between trunk compression levels. During walking, for example, the LT-LA condition results in a lower peak trunk flexion angle than the LT-HA condition (Fig. 5, left). As another example, in response to a perturbation from the left, the LT-LA configuration does not decrease trunk deflection compared to not wearing the exoskeleton while the HT-LA configuration does decrease it (Fig. 8, bottom left).

Fig. 6.

Peak low back extension moment for walking, sit-to-stand, and lifting a box during different exoskeleton configurations. No exo = no exoskeleton, LT = low thoracic compression, HT = high thoracic compression, LA = low abdominal compression, HA = high abdominal compression

None of the four exoskeleton configurations appear to be optimal for every situation: for example, while HT-LA results in the lowest trunk deflection in response to perturbations from the left, it results in the highest median trunk deflection in response to perturbations from the front (Fig. 8). Thus, future back support exoskeletons should ideally allow trunk compression (and other characteristics) to be modified either manually by the wearer or automatically by sensors and actuators in the exoskeleton, thus providing appropriate support for a particular activity.

B. Study Limitation: Two Subjective Compression Settings

Though we found significant effects of trunk compression, we acknowledge that our manipulation of compression was not optimal. First, we examined only two compression settings (low and high), but it is possible that the effects of compression are nonlinear and that investigating only very high and very low settings does not provide insight into the effects of medium compression levels. Second, we defined high and low compression subjectively for each participant, which may have increased intersubject variability (since participants likely perceive pressure, comfort and pain differently) and decreased experiment reproducibility. Future studies should consider objectively defining compression via the contact pressure applied to the body by the exoskeleton at different points, as already done in a recent study [9].

C. Statistical Power and Other Confounding Variables

Our study included 12 participants of relatively similar heights and weights, resulting in low statistical power for several analyses. Future studies in this area will likely need to involve larger numbers of participants as well as keep track of numerous confounding variables that likely contribute to the intersubject variability observed among participants. For example, future studies should recruit participants with a larger spread of ages, heights and weights as well as a better balance of sexes. Ideally, they should also measure body proportions (e.g., hip, waist and chest sizes) and use them as covariates in statistical analyses. Body side dominance may also play a factor, as we observed differences in participants’ responses to perturbations from the left and right side (Figures 8 and 9). While body side dominance was not recorded in our study, we later contacted all participants to ask about their handedness; 10 replied and all stated that they were right-handed, so we did not analyze this in more detail.

In addition to physical characteristics, the strategies used by participants during different activities should also be considered. For example, when asking participants to lift a 20-pound box from the floor, we did not explicitly prescribe a lifting strategy. Some participants thus squatted down (lifting primarily with their legs) while others bent their back with their legs mostly straight (lifting primarily with their back), increasing intersubject variability. In at least one case, the strategy explicitly changed as a result of the exoskeleton (participant was no longer able to bend his back due to high abdominal compression and was forced to squat), potentially increasing variability further. In the future, this could be controlled by explicitly prescribing ways to perform each activity and/or monitoring how task strategies change as a result of the exoskeleton.

Finally, given the many sources of intersubject and intrasubject variability, it is possible that statistical analyses of large samples can only provide limited, very general findings, and that real-world users of trunk exoskeletons will simply need to work with the exoskeleton for some time to determine appropriate configurations for specific activities by trial and error. In this case, users will likely obtain useful guidance via proprioception, but may also benefit from sensors integrated into the exoskeleton that could provide quantitative feedback about how the user’s posture has been affected by the device.

D. Underlying Mechanisms

While our study shows that trunk compression affects posture, low back moments and muscle demand, the exact underlying mechanism is not entirely clear. Traditional spinal orthoses aim to support the wearer through mechanisms such as motion limitation, load reduction/redistribution, spinal stabilization and modified muscle activation [8], [14], [15], and it is likely that our trunk exoskeleton acts on the body through a combination of these mechanisms. For example, previous studies of spinal orthoses have found that they can reduce trunk flexion via motion limitation [14], and our study indicates that both thoracic and abdominal compression have the potential to limit motion. Post-experiment interviews indicated that several participants changed their task completion strategies entirely – during box lifting, for example, at least one participant switched from bending his back to squatting (a more ergonomic lifting strategy) as a result of (by his description) the motion limitation caused by high abdominal compression.

Similarly, the reduced trunk deflection and reduced peak EMG in response to perturbations are likely due to the exoskeleton’s immobilization effect, as effects of increased trunk immobilization on stability have been observed with traditional spinal orthoses [15]. As stabilization in response to perturbations generally involves muscle cocontraction [26], externally provided immobilization likely reduces the need for cocontraction and thus reduces EMG. The significant advantage of a trunk exoskeleton over traditional rigid orthoses is that this immobilization can be modified quickly and easily at different spinal levels, allowing the trunk to be immobilized when necessary (e.g., if stabilization is critical) and released when the user needs to be able to move freely.

However, not all effects of the exoskeleton can be due to trunk immobilization. Simply wearing it at low compression levels (with very little immobilization) already has an effect compared to not wearing it, as evidenced by, e.g., Figure 6 (center) and Figure 9 (bottom right). Thus, it is possible that the weight added to the body by the exoskeleton has an effect on its own. The weight is primarily due to the exoskeletal spinal column on the wearer’s back and may explain results such as the increased low back extension moment during sitto-stand motions or the difference between perturbations from the front and from the back. However, the added weight may also increase the metabolic cost of the user, and this should be examined in future studies using previously established exoskeleton metabolic load evaluation techniques [27].

Based on the measurements taken in our study, we cannot say with certainty whether the exoskeleton’s effects are truly primarily due to immobilization (as we believe) or due to other underlying mechanisms. A more detailed understanding of these mechanisms is critical for future development of trunk exoskeletons and could be achieved with additional sensors, additional data analysis and/or additional experiment conditions. For example, modular modifications of individual exoskeleton components could be used to examine the effects of factors such as exoskeleton weight and contact pressure (as already done in studies of, e.g., gait exoskeletons [20]). Furthermore, full-body musculoskeletal modeling could be used to estimate spinal loading [28], though this would require more sensors than were used in our study.

E. Other Exoskeleton Characteristics

While the current study focused on the effects of thoracic and abdominal trunk compression, other trunk exoskeleton characteristics likely have a strong effect on the wearer as well. One characteristic of interest is the device’s stiffness, which was suggested to be responsible for differences between traditional off-the-shelf spinal orthoses [13], [16], though this was never investigated in detail. Our trunk exoskeleton already allows stiffness to be investigated, as each coupling can be independently varied. Another characteristic of the interest is the human-exoskeleton interface (the way the device grips the body), which is known to have a major effect on wearer comfort and device effectiveness [29] but has seen little systematic study in trunk exoskeletons. Neither of these characteristics were examined in the present study since varying them is more time-consuming than varying compression (varying the human-exoskeleton interface would require the end-effectors to be removed and replaced, and varying stiffness would require part of the coupling assembly to be removed and replaced) and since varying multiple characteristics simultaneously would result in very long study sessions.. However, future studies should investigate multiple exoskeleton characteristics at once if possible, as their effects may not be additive. To enable easier study of stiffness in the future, we are currently prototyping a new version of the trunk exoskeleton that would allow stiffness to be varied using small actuators connected to a microcontroller rather via manual mechanical modification of the coupling assembly.

F. Longer-Term Studies

Finally, our study involved only a limited number of activities and only a very brief evaluation period. While our exoskeleton is able to modify trunk kinematics and muscle demand via changing thoracic and abdominal compression, there is no guarantee that such modifications would have long-term benefits. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that long-term modifications would even be feasible: since different exoskeleton configurations have different effects during different activities, a trunk exoskeleton would have to be regularly reconfigured to be suitable for the current activity. This could be done manually by the wearer, but manual reconfiguration may prove to be too confusing and/or tedious. Alternatively, it could be done automatically using sensors that recognize the wearer’s activity and actuators that reconfigure the exoskeleton accordingly; similar methods are already used in lower limb prostheses [30], but may not be sufficiently robust for use with trunk exoskeletons, especially given the significant intersubject variability. To evaluate the practical potential of reconfigurable trunk exoskeletons, we believe that it is essential to first determine the feasibility of wearing and reconfiguring such an exoskeleton for an extended period of time. Once this feasibility has been demonstrated, clinical trials can be conducted to examine any health-related outcomes of long-term wear.

V. CONCLUSION

We performed a pilot evaluation of a passive reconfigurable trunk exoskeleton that involved 12 participants performing different activities while wearing the exoskeleton at different levels of thoracic and abdominal compression. Results indicate that thoracic and abdominal compression affect the wearer’s kinematics and muscle demand; furthermore, the effects of different compression levels differ between activities, indicating that a single trunk exoskeleton configuration is not appropriate for all activities. This supports the premise of a reconfigurable trunk exoskeleton whose compression as well as other elements such as stiffness could be adjusted to suit a particular activity, thus providing individualized support to the spine. Such reconfigurable trunk elements could also be combined with motors on the hips and upper arms (as used in other back support exoskeletons), providing an effective combination of trunk support and limb augmentation. However, further research is needed to determine the effects and mechanisms of different trunk exoskeleton configurations on the body, the reasons for the high intersubject variability, and the feasibility of long-term use of such technology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to thank all study participants for their assistance. Furthermore, we thank Bradley S. Davidson of the University of Denver for his valuable advice on study design as well as Venu Akuthota, Akil Jackson, Milton Hardie, Lynn Malec, Margaret Schenkman, Marty Mandelbaum and Chris Jones for input on the exoskeleton design.

This work was made possible by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Grant #2P20GM103432.

APPENDIX

Tables A-I and A-II show the means and standard deviations of all measured variables in all different conditions for session 1 (Table A-I) and session 2 (Table A-II).

TABLE A-I.

Means and standard deviations for all measured variables in session 1. Abbreviations: no exo = no exoskeleton. LT = low thoracic compression, LA = low abdominal compression, HT = high thoracic compression, HA = high abdominal compression, EMG = electromyogram, ES = erector spinae, RA = rectus abdominis, MVC = maximum voluntary contraction.

| walking | sit-to-stand | lifting | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no exo | LT-LA | LT-HA | HT-LA | HT-HA | no exo | LT-LA | LT-HA | HT-LA | HT-HA | no exo | LT-LA | LT-HA | HT-LA | HT-HA | |

| flexion angle (deg) | 6.3 ± 7.6 | 6.6 ± 6.0 | 9.0 ± 5.9 | 6.6 ± 8.4 | 6.2 ± 9.1 | 16.7 ± 7.7 | 23.2 ± 13.1 | 23.9 ± 12.7 | 24.6 ± 12.9 | 23.2 ± 10.6 | 35.4 ± 16.5 | 37.7 ± 13.2 | 38.4 ± 10.8 | 36.2 ± 13.4 | 33.3 ± 12.1 |

| extension moment (Nm) | 28.6 ± 11.8 | 25.0 ± 14.9 | 27.4 ± 15.8 | 29.0 ± 18.7 | 22.1 ± 10.3 | 132.8 ± 28.8 | 140.0 ± 30.1 | 138.2 ± 25.4 | 142.5 ± 25.7 | 137.0 ± 24.2 | 155.6 ± 22.2 | 150.0 ± 11.8 | 148.8 ± 19.7 | 153.6 ± 17.1 | 152.1 ± 22.2 |

| EMG left ES (% MVC) | 30.4 ± 13.3 | 30.5 ± 13.0 | 29.0 ± 10.4 | 33.1 ± 15.8 | 25.6 ± 11.5 | 67.9 ± 27.3 | 71.4 ± 30.8 | 59.2 ± 16.4 | 61.8 ± 19.8 | 63.9 ± 20.5 | 101.8 ± 41.3 | 91.6 ± 37.6 | 94.8 ± 31.7 | 101.4 ± 35.2 | 100.0 ± 42.7 |

| EMG right ES (% MVC) | 30.0 ± 9.3 | 30.0 ± 11.9 | 28.7 ± 11.9 | 27.0 ± 10.3 | 25.3 ± 8.7 | 67.2 ± 25.6 | 68.1 ± 33.6 | 63.7 ± 32.4 | 65.1 ± 33.1 | 63.8 ± 16.8 | 106.0 ± 50.2 | 93.1 ± 41.2 | 100.1 ± 50.5 | 97.8 ± 32.3 | 97.9 ± 42.0 |

| EMG left RA (% MVC) | 6.9 ± 8.6 | 5.5 ± 4.6 | 5.4 ± 4.2 | 6.5 ± 6.7 | 5.2 ± 3.7 | 6.8 ± 5.3 | 7.8 ± 5.6 | 7.0 ± 5.2 | 6.5 ± 3.8 | 7.5 ± 7.3 | 10.6 ± 7.0 | 9.9 ± 8.2 | 9.0 ± 8.2 | 8.6 ± 5.4 | 8.4 ± 5.9 |

| EMG right RA (% MVC) | 7.4 ± 9.1 | 5.4 ± 4.1 | 5.3 ± 3.6 | 5.5 ± 5.1 | 5.5 ± 3.6 | 6.7 ± 5.5 | 6.2 ± 3.6 | 6.1 ± 5.3 | 6.7 ± 4.0 | 6.7 ± 5.7 | 7.8 ± 5.4 | 8.6 ± 6.9 | 8.4 ± 7.0 | 9.5 ± 6.2 | 8.6 ± 5.6 |

TABLE A-II.

Means and standard deviations for all measured variables in session 2. Abbreviations: no exo = no exoskeleton. LT = low thoracic compression, LA = low abdominal compression, HT = high thoracic compression, HA = high abdominal compression, EMG = electromyogram, ES = erector spinae, RA = rectus abdominis, MVC = maximum voluntary contraction.

| walking | sit-to-stand | lifting | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no exo | LT-LA | LT-HA | HT-LA | HT-HA | no exo | LT-LA | LT-HA | HT-LA | HT-HA | no exo | LT-LA | LT-HA | HT-LA | HT-HA | |

| flexion angle (deg) | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.7 |

| extension moment (Nm) | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.3 |

| EMG left ES (% MVC) | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 1.5 | 1.7 ± 1.1 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 1.4 | 2.0 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.6 |

| EMG right ES (% MVC) | 18.6 ± 16.2 | 16.7 ± 13.6 | 14.2 ± 10.8 | 19.1 ± 15.6 | 20.0 ± 17.4 | 10.3 ± 21.6 | 6.2 ± 7.0 | 3.6 ± 3.7 | 5.8 ± 5.2 | 6.6 ± 9.7 | 6.6 ± 5.3 | 6.3 ± 5.2 | 4.9 ± 3.2 | 5.4 ± 4.2 | 7.5 ± 8.3 |

| EMG left RA (% MVC) | 19.7 ± 14.4 | 20.7 ± 13.7 | 18.6 ± 10.9 | 18.7 ± 12.0 | 19.0 ± 10.2 | 10.9 ± 21.1 | 9.2 ± 16.2 | 5.3 ± 5.1 | 6.5 ± 7.6 | 10.4 ± 16.1 | 14.4 ± 11.0 | 13.0 ± 9.9 | 9.0 ± 7.4 | 10.4 ± 10.3 | 12.9 ± 11.8 |

| EMG right RA (% MVC) | 2.8 ± 1.9 | 2.2 ± 1.3 | 3.0 ± 1.9 | 2.1 ± 1.6 | 2.9 ± 1.7 | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 1.9 | 2.6 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 1.9 | 2.9 ± 1.8 | 3.1 ± 1.7 | 3.0 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 2.2 | 2.8 ± 1.6 | 3.4 ± 2.6 |

Footnotes

Disclosure of Financial Interests

Coauthor A. P. Johnson has patented parts of the trunk exoskeleton used in this work, and has an interest in commercializing the technology. The other authors declare that they have no financial interests related to the research.

Contributor Information

Maja Goršič, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071. USA.

Yubi Regmi, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071. USA.

Alwyn P. Johnson, Livity Technologies, Highlands Ranch, CO 80129, USA

Boyi Dai, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071. USA.

Domen Novak, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071. USA.

REFERENCES

- [1].De Rijcke L et al. , “SPEXOR: Towards a passive spinal exoskeleton,” in Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Wearable Robotics, WeRob2016, 2016, pp. 325–329. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Näf MB et al. , “Passive back support exoskeleton improves range of motion using flexible beams,” Front. Robot. AI, vol. 5, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lamers EP, Yang AJ, and Zelik KE, “Feasibility of a biomechanically-assistive garment to reduce low back loading during leaning and lifting,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, vol. 65, no. 8, pp. 1674–1680, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Johnson DD, Ashton-Miller JA, and Shih AJ, “Active spinal orthosis to reduce lumbar postural muscle activity in flexed postures,” J. Prosthetics Orthot, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 109–113, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [5].James SL et al. , “Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017,” Lancet, vol. 392, pp. 1789–1858, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Balagué F et al. , “Non-specific low back pain,” Lancet, vol. 379, no. 9814, pp. 482–491, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].International Society for the Advancement of Spine Surgery, “Policy statement on lumbar spinal fusion surgery,” 2015.

- [8].Qaseem A et al. , “Noninvasive treatments of acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians,” Ann. Intern. Med, vol. 166, no. 7, pp. 514–530, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Huysamen K et al. , “Assessment of an active industrial exoskeleton to aid dynamic lifting and lowering manual handling tasks,” Appl. Ergon, vol. 68, pp. 125–131, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].de Looze MP et al. , “Exoskeletons for industrial application and their potential effects on physical work load,” Ergonomics, vol. 59, no. 5, pp. 671–681, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Toxiri S et al. , “Rationale, implementation and evaluation of assistive strategies for an active back-support exoskeleton,” Front. Robot. AI, vol. 5, p. 53–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Azadinia F et al. , “Can lumbosacral orthoses cause trunk muscle weakness? A systematic review of literature,” Spine J, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 589–602, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Morrissette DC et al. , “A randomized clinical trial comparing extensible and inextensible lumbosacral orthoses and standard care alone in the management of lower back pain,” Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976), vol. 39, no. 21, pp. 1733–1742, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Curfs I et al. , “Evaluating the immobilization effect of spinal orthoses using sensor-based motion analysis,” J. Prosthetics Orthot, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 23–29, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kienle A, Saidi S, and Oberst M, “Effect of 2 different thoracolumbar orthoses on the stability of the spine during various body movements,” Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976), vol. 38, no. 17, pp. E1082–E1089, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Utter A et al. , “Video fluoroscopic analysis of the effects of three commonly-prescribed off-the-shelf orthoses on vertebral motion,”Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976), vol. 35, no. 12, pp. E525–E529, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Willems P, “Decision making in surgical treatment of chronic low back pain: the performance of prognostic tests to select patients for lumbar spinal fusion,” Acta Orthop, vol. 84, no. sup349, pp. 1–37, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Baltruschet al SJ, “The effect of a passive trunk exoskeleton on functional performance in healthy individuals,” Appl. Ergon, vol. 72, pp. 94–106, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Park J-H et al. , “Robotic Spine Exoskeleton (RoSE): Characterizing the 3-D Stiffness of the Human Torso in the Treatment of Spine Deformity,” IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 1026–1035, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bartenbach V et al. , “A lower limb exoskeleton research platform to investigate human-robot interaction,” in IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, 2015, pp. 600–605. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Johnson AP et al. , “Design and pilot evaluation of a reconfigurable spinal exoskeleton,” in Proceedings of the 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2018, pp. 1731–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Johnson AP, “Flexible coupling system,” US 9782273 B2, 2017.

- [23].Zazulak BT et al. , “Deficits in neuromuscular control of the trunk predict knee injury risk: A prospective biomechanical-epidemiologic study,” Am. J. Sports Med, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kingma I et al. , “Validation of a full body 3-D dynamic linked segment model,” Hum. Mov. Sci, vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 833–860, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [25].De Leva P, “Adjustments to Zatsiorsky-Seluyanov’s segment inertia parameters,” J. Biomech, vol. 29, no. 9, pp. 1223–1230, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Granata KP and Marras WS, “Cost-benefit of muscle cocontraction in protecting against spinal instability,” Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976), vol. 25, no. 11, pp. 1398–1404, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Junius K et al. , “Metabolic effects induced by a kinematically compatible hip exoskeleton during STS,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, vol. 65, no. 6, pp. 1399–1409, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kim HK and Zhang Y, “Estimation of lumbar spinal loading and trunk muscle forces during asymmetric lifting tasks: application of whole-body musculoskeletal modelling in OpenSim,” Ergonomics, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 563–576, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yandell MB et al. , “Physical interface dynamics alter how robotic exosuits augment human movement: implications for optimizing wearable assistive devices,” J. Neuroeng. Rehabil, vol. 14, no. 1, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Stolyarov R, Burnett G, and Herr H, “Translational motion tracking of leg joints for enhanced prediction of walking tasks,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, vol. 65, no. 4, pp. 763–769, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]