Abstract

Objective:

This study investigated barriers to quality end-of-life care in the context of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), one of the most common degenerative dementias in the United States.

Methods:

The study consisted of telephone interviews with caregivers and family members of individuals who died with DLB in the last 5 years. Interviews used a semi-structured questionnaire. Investigators employed a qualitative descriptive approach to analyze interview transcripts and identify common barriers to quality end-of-life care.

Results:

Thirty participants completed interviews. Reported barriers to quality end-of-life experiences in DLB pertained to the DLB diagnosis itself and factors relating to the U.S. healthcare system, facilities, hospice, and healthcare providers (physicians, staff). Commonly reported barriers included lack of recognition and knowledge of DLB, lack of education regarding what to expect, poor coordination of care and communication across healthcare teams and circumstances, and difficulty accessing healthcare resources including skilled nursing facility placement and hospice.

Conclusion:

Many identified themes were consistent with published barriers to quality EOL care in dementia. However, DLB-specific EOL considerations included diagnostic challenges, lack of knowledge regarding DLB and resultant prescribing errors, difficulty accessing resources due to behavioral changes in DLB, and waiting to meet Medicare dementia hospice guidelines. Improving EOL experiences in DLB will require a multifaceted approach, starting with improving DLB recognition and provider knowledge. More research is needed to improve recognition of EOL in DLB and factors that drive quality EOL experiences.

Keywords: Dementia with Lewy bodies, Lewy body disease [MeSH], death [MeSH], palliative care [MeSH], terminal care [MeSH], hospice care [MeSH], qualitative research [MeSH], health care quality [MeSH]

Introduction

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is one of two diseases under the Lewy body dementia umbrella. Lewy body dementia is the second-most-common neurodegenerative dementia in the U.S. after Alzheimer disease (AD),1 but it often is undiagnosed.2 Most individuals with DLB die from dementia-related causes,3,4 but little is known regarding end-of-life (EOL) experiences of individuals with DLB and their families. This is particularly important as EOL experiences in DLB may be distinct from other dementias like AD. Individuals with clinically-diagnosed DLB survive a median of 3–4 years after diagnosis,3,5-7 shorter than those with AD dementia.6,8 DLB symptoms such as hallucinations, paranoia, cognitive fluctuations, parkinsonism, orthostatic hypotension, and antipsychotic hypersensitivity9 may also affect EOL experiences.10 Individuals with Lewy body dementia have more than double the likelihood of respiratory death as those with AD dementia4 and commonly die from failure to thrive (65%) or pneumonia/swallowing difficulties (23%).3

Barriers to quality EOL care in dementia relate to health systems (e.g. lack of reimbursement),11-13 difficulty recognizing the EOL in dementia,14 lack of awareness of a role for palliative care in dementia,11-13 lack of education and staff training,12,13 need for caregiver support and respite services,11-13 difficulty assessing patient symptoms,11 and treatment of behavioral symptoms.12 Such barriers may explain why many individuals with dementia do not access palliative care services or access them only in the final weeks of life.3,15

Given the many aspects of DLB that are unique from other dementias, we aimed to explore barriers to quality EOL care with caregivers and families of individuals who died with DLB. This was part of a larger study investigating EOL experiences of individuals with DLB and their families.

Method

Study Design

Caregiver/family member interviews were conducted to explore barriers to quality EOL care for individuals with DLB and their families. A qualitative descriptive approach16 was used to collect and analyze data. This technique describes straight-forward accounts of participants’ views and provides a comprehensive summary without intending to generate or test theory. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research guided study reporting (Supplementary File 1).17

Population and Recruitment

Interview participants were recruited through a survey investigating cause of death and EOL experiences in DLB.3 Individuals were eligible for the survey if they were a caregiver, family member, or friend to an individual who died with a DLB diagnosis within 5 years and could complete an online English-language survey. Recruitment occurred through the Lewy Body Dementia Association (LBDA). At the survey conclusion, respondents were asked if they were willing to participate in a 30-minute telephone interview. Willing respondents were given the PI’s contact information to learn study details. Individuals contacting the PI received the informed consent form and semi-structured interview guide. The target sample size was quickly surpassed and a second IRB-approved email script informed interested individuals regarding enrollment completion. Volunteers were invited largely sequentially but with purposive sampling for representation of different genders and roles (spouses, children).

The University of Florida institutional review board provided approval (IRB201701657). The study was conducted with a waiver of documentation of informed consent. Participants reviewed the informed consent form prior to the telephone interview. Participants asked questions about the study and consent at the call start. After questions and verbal consent, recording and interviewing commenced.

Data Collection and Analysis

The PI (MJA) developed the semi-structured interview guide and revised it based on suggestions from LBDA staff, two LBDA scientific advisory board members, and three caregivers for individuals who died with DLB. The guide included 11 open-ended questions regarding EOL experiences, what went well, what could have been better, necessary decisions, hospice experiences, and whether they would do anything different in retrospect (Supplementary File 2). The PI, a physician specializing in DLB, conducted all interviews. She had no prior relationship with participants. Participants called into the interview; phone numbers were not collected. A professional service transcribed interviews verbatim so member checking was not employed. Participants could opt to receive study results.

Investigators used Microsoft Word® 2016 tables to organize data and a qualitative descriptive approach to identify, define, and organize themes.16 One investigator (SA), a research assistant with qualitative experience but not DLB expertise, independently analyzed 5 interviews to create a draft log of emerging themes and sample quotes. A second investigator (MJA) reviewed and revised the initial coding. Consensus was achieved for emerging themes. SA analyzed remaining transcripts using a constant comparative technique, expanding or merging thematic codes as needed. MJA reviewed and revised coding again after 20 and 30 interviews, also applying a constant comparative approach. Subthemes were identified by both investigators. MJA assessed saturation during interviewing; MJA and SA reassessed saturation by consensus following coding. Co-investigators gave feedback after the initial analysis.

Results

Data Collection and Participant Demographics

The LBDA posted the DLB EOL survey link on 9/1/2017. Within a week, over 400 individuals completed the survey and over 60 volunteered for interviews, so the survey question querying interview interest was removed. Investigators contacted 36 volunteers: 30 completed interviews, 4 did not respond after study information was provided, 1 opted not to participate given scheduling difficulties, and 1 did not attend a scheduled interview. Investigators notified 47 additional volunteers that recruitment ended. Interviews occurred 9/15/2017-10/30/2017. Most participants were women (27/30, 90%): 13 daughters, 11 wives, 1 sister, 1 daughter-in-law, and 1 niece. Two husbands and 1 son participated. The study collected no additional demographic information. Interview participant demographics resembled survey demographics: 89% of 657 respondents were women, 42% were spouses, and 53% were children.3 Average interview duration was 31 minutes.

Barriers Relating to Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Interviews focused on EOL experiences, but 11 participants highlighted misdiagnosis, delays in diagnosis, and/or conflicting diagnoses as important parts of their experiences (Supplementary File 3).

I would definitely say that if I could’ve had… a diagnosis of Lewy body dementia nine years ago—I think that things would’ve been very different in how we dealt with our—with life. (18, wife)

We didn’t get a really firm diagnosis, actually until really months before he went into his final last stages. And his last stages were very quick. (9, daughter)

Even once individuals received the DLB diagnosis, lack of knowledge regarding the diagnosis was a barrier to EOL care across the healthcare system.

I was kind of shocked at the lack of information, even in the medical community. (8, daughter)

You know, there’s a lotta people that aren’t getting good medical care, and the lack of awareness about Lewy body dementia is a real problem. (29, daughter)

Participants specifically described this barrier for physicians from all backgrounds and for staff at locations ranging from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities to hospice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Lack of Knowledge across the Healthcare System Affects End-of-Life Care in DLB

| Healthcare Location, Provider |

Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|

| Physicians generally | And physicians do not understand it. And, um, you know, the let’s try Haldol, or let’s try this and try that. Um, none of ‘em understood the complexity of the behavioral issues. And that’s what made the management of it from the mid to the late stages so difficult. (13, daughter) One of the things about doctors is that a lot of doctors don’t even understand this disease at all. (21, wife) |

| Primary care physicians | His primary doctor, um, I don’t think that they-they even knew what to tell me. (5, wife) Her primary physician and nurse practitioner were not unfamiliar with Lewy body. But I don’t think they were deeply knowledgeable about it. So, I think education of both, um, the general population and the medical community would be helpful. (20, daughter-in-law) |

| Neurologists | This neurologist recognized the poss—and he started talking about Lewy body dementia. And then we got to a point when he said, "I—I don't know what else to do with—I can't help him anymore because this is the limit of what I know about it." (18, wife) Even our neurologist’s office was very, um, ignorant about that sort of thing. It-it surprised me, especially with the neurology office. You would think they would have wonderful resources to share, and they just didn’t. (28, wife) |

| Emergency room physicians, staff | We were in emergency, and they had asked, you know, about her. And I says, “Well, she's got, you know, Lewy body dementia." And it was just like, "What? Well, I've never heard of that," you know. So just—there needs to be some more education out there for people just to understand that there is this other kind of dementia. Everything is not Alzheimer’s. (3, daughter) I had a bunch of pamphlets on what is Lewy body, and I would literally carry them around with me, and I literally handed them out in the ER when Mom had been—had to be taken there a couple times— because they have no idea how to handle someone. Not only dementia or Alzheimer’s; they just don’t know Lewy body. And then there was that big, big concern about some of those drugs that would potentially—could be fatal if someone— with Lewy body takes certain drugs… “Don’t give her this. Don’t give her this.” And that’s wh-always what they give people to calm them down. So just from day one, it was lack of awareness. (14, daughter) |

| Hospital providers | Nobody at the hospital had ever heard of Lewy body dementia. (25, wife) |

| Skilled nursing facilities | The nursing home had not heard of it, so I actually pulled up the literature from the LBDA.org organization to try to share with them. They didn’t really actually have a whole lot of interest. I think they just have their hands full. (10, son) I think in general, uh, people who are, um, doing the most direct and personal care are not well-acquainted with Lewy body—and what distinguishes it from other forms of dementia. And a lotta the time that probably doesn’t matter, but toward the end of life, I think it-it would be helpful if people were—if everybody who is involved in care, um, has a sense of what’s normal and what’s not what’s part of the disease and what’s not. (20, daughter-in-law) |

| Hospice | When the nurse came to see him on Thanksgiving… she suggested Haldol. I went and picked up the Haldol the next day, and that was Friday… And I would say within a half hour—and this is about two, two and a half hours since he had his Haldol—he had a neuroleptic malignant episode… And I truly believe that it was the Haldol that hastened his death, and my—the inexperience of the nurse who suggested it, the inexperience of the provider who okayed it—- the inexperience of the pharmacist who filled it. Why are we—you know, somebody with a LBD diagnosis, why are we giving Haldol? (17, wife) |

DLB: dementia with Lewy bodies, LBD: Lewy body dementia

Barriers at Different Levels of the Healthcare System

Participants described two main system-level barriers: poorly coordinated care across the healthcare system and cost. Cost was a barrier regardless of whether families desired in-home care or used a skilled facility (Table 2).

Table 2.

Barriers Relating to the Healthcare System, Skilled Facilities, & Home Care

| Level | Barrier | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Health system | Poorly coordinated care | Once they figured out what to do, they couldn’t execute it across the team, you know, so it’s so many people. The hospice people take over for the doctor, and then the hospice people are communicating with the in-house people, but the in-house people are in so many different shifts, and— I'd call hospice. Hospice—says, “No. Your doctor has to write an order.” (2, daughter) I just can’t say enough about the importance of hospice though and palliative care and a team approach to this. And it just, it can’t be, you know, so many physicians. You know, it’s a, a turf battle and there’s not enough of a team with social work, with PT, and OT, and there absolutely has to be a team approach to dealing with patients with Lewy body dementia. (13, daughter) |

| Cost | I alert anyone that has to go into a memory-care facility, the cost is astronomical… And nothing pays for it, unless you have long-term care, but that’s expensive… (6, husband) And I know it’s a business to them and they gotta make money, too, but, you know, who can afford $24, $26, $28 an hour? Are you kidding me? Nobody can afford that. You know, stupid insurance… it-it’s just ridiculous, the elder care in this country. (7, niece) Then our healthcare system… it's darn expensive to put somebody in memory care. It's darn expensive to have somebody come to your house, and our healthcare system doesn't—doesn't allow for any help with that. I think it's terrible. I think it's terrible, terrible, terrible. (18, wife) |

|

| Facilities | Trouble finding the right facility | “You cannot take her home. You have to put her into a strong memory-care facility.”… And I found one that I thought was perfect, and [they] sent a nurse to the hospital to check on my wife and see if she’d be a fit. And the shocking thing for me was they called me on a Friday afternoon and said, “We were there, and she is too much for us to handle. We cannot take her.” And it’s literally like your whole world falls apart, like, now what do I do? (6, husband) We couldn’t really find a place that would like specialize in that type of stuff… He was there [in a geriatric psychiatry unit] for three weeks. They were really wanting us to move him somewhere. We could not really find a place for my—he couldn’t go home. (19, daughter) I must have called every facility in this entire area and county, and they were full, or they didn’t take that kind of dementia patient because they needed more care. (27, wife) |

| Facility unable to handle person with DLB | We got a call that said Dad had become combative and that we had to get him out of the unit immediately. They had called everywhere in the area and said, "You have to find another place for him to go… (9, daughter) And their way of dealing with a-a incident of acting out was they’d send the person to the hospital. (22, wife) |

|

| Insufficient staffing, turnover | I didn’t know about the crisis in healthcare around, assisted living and whatnot in terms of the pipeline issues of just not having enough workers. (2, daughter) They had 22 people in this wing, and so they couldn’t necessarily check everything, and there was a rotating nursing staff. So, not everybody saw him, you know, every day… so, some of that gets lost in the shuffle. (10, son) The facility she was in was new, so it had a fair bit of staff turnover. (20, daughter-in-law) |

|

| Desire for better staff communication with family | In retrospect what we should’ve done is sat down with a nurse and—you know, when it was—once she’d stopped eating and said, “Right, this is what you’re now going to expect.” (16, daughter) The other things, um, I would’ve liked to see in these are, in the grand scheme of things, quite minor. But the communication between the facility and the families of people in memory care about such things as staffing changes was - suboptimal. (20, daughter-in-law) |

|

| Family conflict with staff | Those places, you know, they think they’re doing you a favor by giving somebody a shower twice a week. And I said, “Nope. She showers every day, and that’s what I want her to have.” And, um, at one point in time, they even raised the price cuz I had ‘em showering every day. (7, niece) “She’s suicidal, and we need to medicate her.” Dude, no, I don’t think so. I really laid into this one guy. I said, “Oh, my gosh, I—you’re not even thinking here… Of course this is the way she’s thinking right this second. She’s in a brand-new place, and she just—you know, and she’s ill,” and all this other stuff. So that, the whole psych eval, I don’t— the timing of that just seemed really, really odd. I didn’t think that made a lot of sense. Someone who has dementia… Brand-new environment, has no idea what’s going on. Of course she’d rather not be there. (14, daughter) It’s very difficult. Sometimes you get angry because it’s very difficult watching an aid being rough with your loved one… I’m pretty, I was very protective of my husband. And I think most people who’s a caregiver and a spouse is that way. I think they should be, the aids and the nurses should be responsible, you know, aware of that (21, wife) |

|

| Home care | Difficulty finding good caregivers | We were able to keep mother in her home. We hired a team of uh, around-the-clock team of 24/7 caregivers. That was quite a process, because we had to weed out a lot of horrid folks. (24, daughter) |

| Needing someone to help take charge | The visiting nurse, um, the main one who was assigned to us, we really liked. Unfortunately, she was having a lot of health issues… We got a substitute, who we also liked, but… she didn’t seem to want to take charge as much as the other one did. And I understand she was a substitute for us, um, but the other one had a little more, “Well, I can-I can help you with this,” kinda thing whereas the substitute was like, “Well, call so-and-so and find out such-and-such.” I’m like, I’m already way beyond overwhelmed, you know? Um, so, if we could’ve had our-our regular gal, if her health hadn’t been an issue, I think it would’ve been easier. (28) |

Facility-level challenges started with finding the right facility. Numerous participants reported difficulty finding a facility that would accept a person with DLB, often due to behavioral concerns. After placement, several participants reported that facilities subsequently described an inability to safely care for the person with DLB (Table 2). Sometimes facilities relied on families to help provide care:

The care home, they’re under pressure. They’re busy and everything, and it’s almost like, oh, the family’s there, and it perhaps took the pressure-took the pressure off them a bit— whereas to my mind, it shouldn’t have done. (16, daughter)

Staff unfamiliar with LBD (Table 1) and facility costs (Table 2) were issues affecting facility care in addition to care more generally. In some circumstances, the lack of familiarity with DLB resulted in administration of medications usually avoided in DLB:

Then, in a rehab facility, they administered Haldol… We had no idea this would’ve been a problem… When they administered the Haldol that he fell into sort of a—I wouldn’t say comatose state, but he was uh, retreated quite substantially, and he never really fully recovered from that. (10, son)

A couple of months ago, we had an incident where they—that medication was still in his chart, and one of the caregivers actually didn’t pay attention and go further into it. And he was agitated, and she gave that to him. And… they call me to say, “Well, we gave him the wrong medication.” And, sure enough, he slept for 36 hours. (18, wife)

Participants mentioned challenges from insufficient staffing and staff turnover. In reflecting on what would have improved the EOL experience, multiple participants described a desire for improved communication with facility staff. They also reported differing expectations causing conflict with staff (Table 2). Participants reported fewer barriers relating to home care, but difficulty finding good caregivers and needing visiting nurses to take charge were two themes (Table 2).

One major barrier to hospice care was waiting for the person with DLB to meet criteria for hospice for a person with dementia (Table 3). While many families reported waiting to be eligible for hospice, one wife delayed hospice use because she didn’t want her husband to lose access to physical therapy:

Table 3.

Barriers Relating to Hospice Care

| Barrier | Exemplar Quote |

|---|---|

| Waiting to meet hospice criteria | When they finally called them, I-I mean, it was like, oh, my gosh. Finally. You know, that’s a horrible thing to say, but finally, we get hospice… It seemed like a long time before he met those criteria of hospice. (5, wife) The first hospice said, no, he’s not—“We won’t take him,” essentially. They didn’t think that he met the guidelines. And so, there was another hospice that said yes. So, he was in hospice for, I would say, about six months before he died. (21, wife) They saw the writing on the wall, and I think they knew that he was destined for hospice, but because at that moment, which was M—early May, h-he didn’t meet all of the criteria at that time to be— admitted. It wasn’t another two weeks until he finally got admitted, so mid-May. He was in hospice maybe two, three weeks, and he passed… The doctor called them in, and [the hospice provider] came and she said, “Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. It’s just a—it’s not today. It’s just a matter of time.” Well, I could have used you today. You know, I coulda used that little extra support… I think if hospice sees the writing on the wall, is two weeks really gonna matter? I mean, seriously, is two weeks really gonna matter when you see folks kind of struggling? (23, daughter) |

| Poor coordination | Well, what it came down to was that was the way we could get him morphine. And I had to literally drive like the wind to get to the pharmacy as fast as I could to get him the morphine, but we couldn't do that until hospice was contacted and said, "Okay. Get him the morphine." So it was it was a madhouse. I was calling, calling, calling, and trying to get somebody to okay this fast. (15, wife) And supposedly, that-that was the group that would come in at the end, the last few, um, wh-when he was really in the dying stage, and be there 24 hours. And so, I chose that. It turns out that I was very, very unhappy with the kind of response that they had… He had a-a huge, huge, blister on his heel. It took me two days finally actually having a fit, crying and everything, on the phone, before they would—they sent somebody out to take a look at it… And I couldn’t get them to respond. And finally, they sent out what they needed to send out. It was just—it was one incident like that after another… The last incident was—the, uh, the last four days. So, he died on Thursday. So, Monday night, the director of the summer house… finally called [hospice] and she said, “You need to bring somebody in here. This is now the time to do the 24-hour.” And finally, they brought somebody in that-that, uh, Monday. (26, wife) |

| Staff inconsistency | One of the things that I thought that hospice should have done is they kept giving me different nurses all the time. And I thought that, that it would have been nice to have the same nurse, the same— continuity. (21, wife) And I found that in a situation like that there were too many people that he came in contact with, and the—everybody’s way of doing things were different. And he had all his life been a fearful person…. So, um, he would give them a very hard time. (30, wife) |

| Needing more education from hospice about what to expect | I think if I understood a little bit more about the medication and the hospice flow, how that goes,— right? Is it—is it, “Initially we do morphine, and then for three days—and then this”? Like, is there some sort of protocol?… This is actually a point that I wanted to share with you—I wanted to have—I tried to get a hold of the head nurse for hospice… I just was kind of not understanding what to do next. (12, husband) I feel like we had a little lack of information as far as meds and how it goes. You know, as the days progress, we’re assuming that her kidneys are shut down and they’re gonna hurt her, so we’re give her more morphine, or—yeah, how does that—how does that go down? I think that would be helpful. (14, daughter) There was no real discussion about, you know, this is what likely to happen over the next, you know, number of months. (16, daughter) It was very surreal, actually. The hospice team was nice. It was a little shocking because we didn’t realize that my dad wasn’t gonna like be eating or drinking there. (19, daughter) |

| Difficulty with hospice medications | One of the bad things that happened, um, repeatedly for my mom is that they kept messing up the morphine level… the coordination of care, there were a couple of different errors that happened, you know, well-meaning people. (2, daughter) He looked at the strings hanging down from the overhead lights and he thought they were a noose. I mean, it wasn't anything you know, anything I was worried about. I was just relating to [the nurse] how things had been going. And she suggested Haldol. And I didn't research it… About two, two and a half hours since he had his Haldol… He was suddenly sitting upright… Every muscle in his body was clenched. His mouth was clenched. It was opening and closing, opening and closing. His tongue was thrusting out. He almost bit his tongue off at one point and he was groaning and moaning, and he was in terrible pain… His temperature skyrocketed… From there, his kidneys shut down, and he was gone by Tuesday morning. (17, wife) |

I really fought not to put him on hospice because I felt like he should have as much therapy and PT and— good experiences as possible and not just let him have end of life experience before he was ready… I think that with this disease, dementia, the person should be allowed to go on hospice but have the therapy and the exercise to keep their brain going as much as they can. (21, wife)

Once individuals were receiving hospice either at home or in a skilled nursing facility, participant descriptions of hospice experiences were generally positive. However, some participants described hospice-related barriers to quality EOL experiences including poor coordination/responsiveness from the hospice provider, changes in staff that could be particularly hard for individuals with dementia, needing more information on what to expect, and challenges relating to hospice medications (Table 3). While some individuals with DLB received haloperidol from hospice packs without apparent adverse effects, others had negative reactions (Table 3, Supplementary File 3).

Physician-Level Barriers

The most common physician-level barrier to quality EOL experiences in DLB was the lack of knowledge of physicians across environments and specialties (Table 1). Some participants described needing to travel to see a specialist:

The neurologist that he got referred to, a-and I don’t say this lightly, I think he was just a quack… Pe-people travel away from [city] to find a good neurologist. (5, wife)

After a year, I took him back to his neurologist, and his neurologist said, “Nope, he—it didn’t advance in Parkinson’s.” He says, “I need you to go to [city] and talk to a doctor there.” (11, sister)

Participants commonly reported that physicians never discussed that DLB can be terminal and provided no education regarding what to expect at the EOL (Table 4). Lack of support for the caregiver was an additional barrier (Table 4).

Table 4.

Physician-Related Barriers

| Barrier | Exemplar Quote |

|---|---|

| No discussion that dementia can be terminal | [When answering what could be improved] Probably at least addressing and saying that, you know, this is terminal, and these are the types of things that we have to talk about or think about. And that never happened… I think that if that had happened, maybe we would have been able to get hospice sooner. (3, daughter) Where I figured out that she was gonna die is from reading all the material I could get. But the doctor, I don’t think, ever said she is gonna die. And I think that’s important for this person to know… I think the doctor needs to be very specific with the caretaker. Now, the patient may not wanna hear it. (6, husband) |

| No education regarding what to expect at end of life | …no conversations with any doctors about end of life, or what that was going to be like, or what to expect, or what to plan for. I mean, nothing, nothing (3, daughter) We just were not prepared. We had—we didn’t know what to expect, like I said, and—but my dad was diagnosed with the-the disease and then he, uhm, he-he declined so rapidly— (19, daughter) |

| Physicians didn’t recommend palliative care or hospice | I don’t feel that from his PCP perspective, when [my mother] would take him in and explain things to the doctor, like that he was declining, that she was—my mother, that is—was offered, um, any type of additional care—for perhaps like end-stage—the end-stage Lewy body dementia. Like hospice or palliative care support (1, daughter). Nobody mentioned the word hospice. Nobody ever said it would be a good idea to look into that now too. I didn't think of it. I should have, but, you know—and of course, we didn't know how end his near was. He was- he was only two weeks in the home before he passed away. (15, wife) We did inquire about hospice. Uh, none of our doctors recommended it. In fact, I called the neurologist, and he thought it was too early. This was in 2016 when he was really r-just really goin’ downhill, and I thought—- wow, it doesn’t seem too early to me. (27, wife) |

| Lack of support for caregiver | It is so hard being a caregiver. And I think it's really unrecognized by people who aren't living through it. Um, and doctors don't do a good job of supporting it a lot of the time. (17, wife) |

Discussion

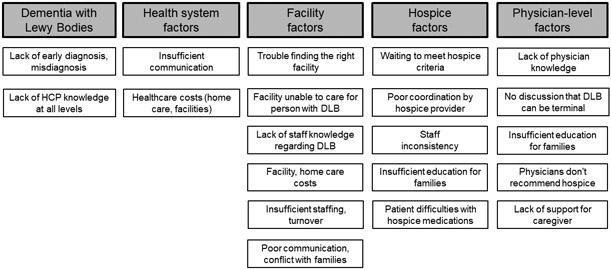

Interview participants described barriers to quality EOL experiences pertaining to the DLB itself and factors relating to health systems, facilities, hospice, and physicians (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Barriers to High-Quality End-of-Life Care in Dementia with Lewy Bodies.

Commonly reported barriers to end-of-life care in DLB related to the disease itself and various levels of the healthcare system. Categorizations do not imply exclusivity. DLB: dementia with Lewy bodies; HCP: Healthcare provider.

Several identified barriers to quality EOL experiences in DLB are consistent with those reported for dementia in general. Knowing what to expect is an unmet need described by prior research with caregivers in Lewy body18 and other dementias.19-22 Families caring for individuals with dementia report that clinicians don’t discuss that dementia can be terminal.20,23,24 Difficulty recognizing the EOL in dementia14 and lack of awareness of a role for palliative care in dementia11-13 are known barriers to dementia palliative care and hospice. Multiple studies show that Medicare hospice guidelines have poor predictive abilities,25-27 further affecting hospice referrals. Communication (between teams, professionals, and patients/families) is a major barrier to quality palliative care in advanced dementia24,28-31 also reported by current study participants (Tables 2, 3).

While current findings are consistent with barriers to quality EOL dementia care generally, this study identified multiple barriers relating specifically to the experience of DLB. Interviews focused on EOL experiences, but numerous participants commented on how delays in DLB diagnosis and initial misdiagnosis negatively affected their experience, even at the EOL. This finding is highly relevant, as prior research found that it can take multiple consultations, often over years, before individuals receive a diagnosis of Lewy body dementia.32 It is believed that 1 in 3 cases of DLB are missed.33 Misdiagnosis as AD is common.32,33 In addition to the need for improved diagnosis, the emphasis on lack of physician knowledge regarding DLB at every level of the healthcare system (Table 1) suggests a need for physician and staff education about all DLB aspects. Physician/staff knowledge is a barrier to quality EOL care in dementia more broadly,12,13 but unique DLB characteristics specifically affect EOL care, such as the lack of defined DLB stages to guide counseling and hospice referrals, presence of behavioral symptoms limiting placement options, and heightened risk of hypersensitivity to antipsychotics34 that may be included in hospice comfort medication packs. Similarly, while there is a need for improved caregiver (and staff) EOL education and counseling in dementia generally, DLB-specific knowledge is critical given the faster progression of DLB compared AD dementia,6,8 the potential for worsening of DLB-specific symptoms in the EOL period,10 the common experiences of swallowing difficulties and failure to thrive in individuals with DLB,3 and increased risks of antipsychotic hypersensitivity.34,35

Difficulty accessing skilled nursing resources was a commonly reported barrier by study participants. Prior research found that individuals with DLB have a shorter time to admission in a skilled nursing facility than individuals with AD dementia.36 Factors associated with an increased risk of skilled nursing facility placement include antipsychotic use, more neuropsychiatric symptoms, and higher caregiver burden.36 This is consistent with caregiver reports in the current study, where neuropsychiatric symptoms often prompted the need for placement. However, numerous interview participants reported difficulty finding or keeping skilled nursing facility spots due to the disease-related behavior of the person with DLB (Table 2). This led to additional stress for families of individuals with DLB at the EOL, as having (often reluctantly) accepted the need for placement, they then were unable to find a facility that could support their loved one’s needs. Some participants had to move the individual with DLB to new facilities because of DLB symptoms. This was associated with further stress at the EOL, consistent with prior research showing that continuity of care in place and relationships is important for quality EOL experiences in dementia.37

DLB-specific considerations also affected hospice care. Physicians failed to recommend hospice and multiple participants reported delays while waiting for their loved one to meet hospice guidelines for dementia. As noted above, these issues can also be challenges in dementia more broadly. However, the challenge in meeting Medicare dementia guidelines may be particularly prevalent in DLB, as Medicare hospice guidelines fail to account for DLB-specific symptoms that may worsen with approaching EOL.10 Once individuals with DLB are receiving hospice, DLB-specific considerations may impact care. Hospice comfort packs often include morphine, lorazepam, haloperidol, anticholinergics (for secretions) and anti-emetics. Anti-emetics that block dopamine (e.g. prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, promethazine) can worsen symptoms in individuals with parkinsonism and anticholinergic agents are generally avoided in individuals with dementia due to potential for worsening confusion, but whether there are particular concerns regarding EOL use in DLB is uncertain. The availability of haloperidol in hospice for individuals with DLB is more problematic, as evidenced by the experience of one participant in this study, where death followed a reaction to haloperidol recommended by a hospice nurse (Tables 1, 3). Over 50% of individuals with DLB have severe reactions to antipsychotics, including impaired consciousness, worsening parkinsonism, and death.34,35 While death is expected in individuals with DLB on hospice, the manner of death can be adversely affected by antipsychotic use.

Barriers to quality EOL care in DLB in this study were grouped in certain categories (Figure 1), but many identified barriers were relevant to multiple categories, such as insufficient provider knowledge, lacking education, poor communication, and cost. Waiting to meet hospice criteria was categorized as a hospice barrier, but could be described as a U.S. health system factor. Many individuals with DLB in the U.S. are of an age that Medicare is their insurance provider. All interview participants were U.S.-based except one, limiting generalizability to international healthcare systems. Other limitations include generalizability based on participant demographics. Most participants were women, consistent with U.S. dementia caregiver statistics.38 Demographics other than gender and role were not collected. Recall bias was limited by recruiting only individuals whose loved one died in the prior 5 years. Participants may have volunteered because of particular experiences or strong views, but many themes were consistent with published research.

Conclusion

Interview participants described multiple barriers to quality EOL experiences in DLB. Commonly reported barriers included lack of recognition and knowledge of DLB, lack of education regarding what to expect, poor coordination of care and communication across healthcare teams and experiences, and difficulty accessing healthcare resources including skilled nursing facility placement and hospice. While many of these findings are consistent with published barriers to quality EOL care in dementia, DLB-specific EOL considerations including challenges obtaining a DLB diagnosis, lack of knowledge regarding DLB and resultant errors in care (e.g. administration of antipsychotics), difficulty accessing resources, particularly because of behavior changes in DLB, and waiting to meet Medicare hospice guidelines for dementia. Successfully improving EOL experiences for individuals with DLB and their families will require a multifaceted approach, starting with improving recognition of DLB and provider knowledge. More research is needed to identify DLB stages, recognition of EOL in DLB, factors that drive quality EOL experiences, and best practices for tailoring palliative approaches for DLB.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Everyone who has contributed significantly to the manuscript is listed as an author. There are no separate acknowledgements relating to contributors.

Funding: The authors received no specific financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article. Lewy body dementia research at the University of Florida is supported by the University of Florida Dorothy Mangurian Headquarters for Lewy Dementia and the Raymond E. Kassar Research Fund for Lewy Body Dementia. Subjects were recruited through the Lewy Body Dementia Association (LBDA).

Conflict of Interest:

M.J. Armstrong: M.J. Armstrong is supported by an ARHQ K08 career development award (K08HS24159); receives compensation from the AAN for work as an evidence-based medicine methodology consultant and is on the level of evidence editorial board for Neurology® and related publications (uncompensated); receives publishing royalties for Parkinson’s Disease: Improving Patient Care (Oxford University Press, 2014); and has received honoraria from Medscape CME. She receives support as an investigator for a Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence.

S. Alliance: Ms. Alliance reports no disclosures.

P. Corsentino: Ms. Corsentino is employed by the Lewy Body Dementia Association.

S.M. Maixner: Dr. Maixner receives support as an investigator for a Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence.

H.L. Paulson: H.L. Paulson is supported by P30AG053760 from the NIH.

A. Taylor: Ms. Taylor is employed by the Lewy Body Dementia Association.

Footnotes

This study was performed in partnership with the Lewy Body Dementia Association with additional research support from the University of Florida Dorothy Mangurian Headquarters for Lewy Dementia and the Raymond E. Kassar Research Fund for Lewy Body Dementia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barker WW, Luis CA, Kashuba A, et al. Relative frequencies of Alzheimer disease, Lewy body, vascular and frontotemporal dementia, and hippocampal sclerosis in the state of Florida Brain Bank. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16(4):203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane JPM, Surendranathan A, Bentley A, et al. Clinical prevalence of Lewy body dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong MJ, Alliance S, Corsentino P, DeKosky ST, Taylor A. Cause of death and end-of-life experiences in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(1):67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Ptacek S, Kåreholt I, Cermakova P, Rizzuto D, Religa D, Eriksdotter M. Causes of death according to death certificates in individuals with dementia: a cohort from the Swedish Dementia Registry. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):e137–e142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker Z, Allen RL, Shergill S, Mullan E, Katona CL. Three years survival in patients with a clinical diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(3):267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price A, Farooq R, Yuan JM, Menon VB, Cardinal RN, O'Brien JT. Mortality in dementia with Lewy bodies compared with Alzheimer's dementia: a retrospective naturalistic cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e017504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsson V, Torisson G, Londos E. Relative survival in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease dementia. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams MM, Xiong CJ, Morris JC, Galvin JE. Survival and mortality differences between dementia with Lewy bodies vs Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(11):1935–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong MJ, Alliance S, Taylor A, Corsentino P, Galvin JE. End-of-life experiences in dementia with Lewy bodies: Qualitative interviews with former caregivers. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0217039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachs GA, Shega JW, Cox-Hayley D. Barriers to excellent end-of-life care for patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(10):1057–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torke AM, Holtz LR, Hui S, et al. Palliative care for patients with dementia: a national survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(11):2114–2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kupeli N, Leavey G, Moore K, et al. Context, mechanisms and outcomes in end of life care for people with advanced dementia. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee RP, Bamford C, Poole M, McLellan E, Exley C, Robinson L. End of life care for people with dementia: The views of health professionals, social care service managers and frontline staff on key requirements for good practice. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beernaert K, Deliens L, Pardon K, et al. What are physicians' reasons for not referring people with life-limiting illnesses to specialist palliative care services? A nationwide survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colorafi KJ, Evans B. Qualitative descriptive methods in health science research. HERD. 2016;9(4):16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galvin JE, Duda JE, Kaufer DI, Lippa CF, Taylor A, Zarit SH. Lewy body dementia: the caregiver experience of clinical care. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16(6):388–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jennings LA, Reuben DB, Evertson LC, et al. Unmet needs of caregivers of individuals referred to a dementia care program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(2):282–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hennings J, Froggatt K, Keady J. Approaching the end of life and dying with dementia in care homes: the accounts of family carers. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2010;20:114–127. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Millenaar JK, Bakker C, Koopmans RT, Verhey FR, Kurz A, de Vugt ME. The care needs and experiences with the use of services of people with young-onset dementia and their caregivers: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(12):1261–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore KJ, Davis S, Gola A, et al. Experiences of end of life amongst family carers of people with advanced dementia: longitudinal cohort study with mixed methods. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Steen JT, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Knol DL, Ribbe MW, Deliens L. Caregivers' understanding of dementia predicts patients' comfort at death: a prospective observational study. BMC Med. 2013;11:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erel M, Marcus EL, Dekeyser-Ganz F. Barriers to palliative care for advanced dementia: a scoping review. Ann Palliat Med. 2017;6(4):365–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Murphy K. Criteria for enrolling dementia patients in hospice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(9):1054–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schonwetter RS, Han B, Small BJ, Martin B, Tope K, Haley WE. Predictors of six-month survival among patients with dementia: an evaluation of hospice Medicare guidelines. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20(2):105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Teno JM, Kiely DK, Davis RB, Shaffer ML. Prediction of 6-month survival of nursing home residents with advanced dementia using ADEPT vs hospice eligibility guidelines. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1929–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies N, Maio L, van Riet Paap J, et al. Quality palliative care for cancer and dementia in five European countries: some common challenges. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(4):400–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies N, Maio L, Vedavanam K, et al. Barriers to the provision of high-quality palliative care for people with dementia in England: a qualitative study of professionals' experiences. Health Soc Care Community. 2014;22(4):386–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sampson EL, Candy B, Davis S, et al. Living and dying with advanced dementia: A prospective cohort study of symptoms, service use and care at the end of life. Palliat Med. 2018;32(3):668–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toles M, Song MK, Lin FC, Hanson LC. Perceptions of family decision-makers of nursing home residents with advanced dementia regarding the quality of communication around end-of-life care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(10):879–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galvin JE, Duda JE, Kaufer DI, Lippa CF, Taylor A, Zarit SH. Lewy body dementia: the caregiver experience of clinical care. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16(6):388–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas AJ, Taylor JP, McKeith I, et al. Development of assessment toolkits for improving the diagnosis of the Lewy body dementias: feasibility study within the DIAMOND Lewy study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(12):1280–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKeith I, Fairbairn A, Perry R, Thompson P, Perry E. Neuroleptic sensitivity in patients with senile dementia of Lewy body type. BMJ. 1992;305(6855):673–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aarsland D, Perry R, Larsen JP, et al. Neuroleptic sensitivity in Parkinson's disease and parkinsonian dementias. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(5):633–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rongve A, Vossius C, Nore S, Testad I, Aarsland D. Time until nursing home admission in people with mild dementia: comparison of dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(4):392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Steen JT, Lemos Dekker N, Gijsberts MHE, Vermeulen LH, Mahler MM, The BA. Palliative care for people with dementia in the terminal phase: a mixed-methods qualitative study to inform service development. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:325–373. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.