To the Editor

Bronchiolitis is the leading cause of hospitalizations among infants in the U.S.(1) Two major respiratory viruses—respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and rhinovirus (RV)—account for 85% of severe bronchiolitis (bronchiolitis resulting in hospitalization).(2) While bronchiolitis has been considered a single disease entity and currently-available management does not vary by causative virus,(3) emerging evidence suggests heterogeneity in the clinical manifestations and pathobiology of bronchiolitis by virus. For example, epidemiological research has shown that causative viruses are associated with distinct risks of both acute (e.g., illness severity) and chronic (e.g., incident asthma) outcomes in childhood.(1) Recent data also suggest an interplay between respiratory viruses, airway microbiome, and host response.(1) For example, studies have shown virus-specific (e.g., RSV- and RV-specific) microbiome composition (through 16S rRNA gene sequencing)(4) and host response (through transcriptomics(5–7) and metabolomics(8)) in children with acute respiratory infection, including bronchiolitis. Despite the clinical and research importance of bronchiolitis, no study to date has reported an integrated investigation of the between-virus differences in microbiome composition (beyond 16S rRNA gene sequencing) and function, along with host response, in the airway of infants with bronchiolitis. In this context, we performed a pilot study using a dual-transcriptomic approach(9,10) —simultaneous profiling of microbe’s transcriptome (metatranscriptome) and host transcriptome—to test the hypothesis that, in infants with severe bronchiolitis, RSV and RV infection have distinct nasopharyngeal airway microbiome composition and function as well as host response profiles.

Details of the study design, setting, samples, measurement, and analysis may be found in the Online Supplement (Supplemental Methods [online]). Briefly, in the current pilot study, we performed dual-transcriptomic profiling of the nasopharyngeal samples from five infants with RSV infection and five infants with sole RV infection (i.e., no co-infecting RSV) as part of an ongoing cohort study. This multicenter prospective cohort study—the 35th Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC-35)—enrolled infants (aged <12 months) hospitalized with bronchiolitis at 17 sites across 14 U.S. states during the 2011–2014 winter seasons. Bronchiolitis was defined by the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines.(3) In addition to phenotypic data measurements, investigators collected nasopharyngeal aspirates within 24 hours of hospitalization using a standardized protocol. These samples underwent 1) real-time reverse transcription PCR to test for respiratory viruses—e.g., RSV and RV—and 2) dual-transcriptomics through RNAseq to profile the microbiome composition and function, as well as host function, in the nasopharyngeal airway.

The bioinformatic processing and analysis are detailed in the Supplemental Methods (online). Firstly, we used microbial RNA to infer microbial taxonomic composition through PathoScope.(11–13) Then, to compare compositional differences (α-diversity indices and individual species abundances) between the RSV and sole RV infection groups, we used linear regression models and Wald test with Cook’s distance correction, respectively. We also used the Benjamini-Hochberg method to correct for multiple testing. Secondly, we used metatranscriptomic contigs to infer microbial function and Gene Ontologies, and compared their between-group differences. Thirdly, we also computed host gene expression profiles for each sample and examined differential expression. Lastly, we also performed pathway enrichment analysis to examine the virus-specific host response.

The ten infants with severe bronchiolitis had a median age of 7 (IQR, 3–9) months. Between the virus groups, there was no significant difference in the baseline characteristics (all P>0.10; Supplemental Table S1 [online]). All RNAseq samples had sufficient sequence depth (mean, 74 million pair-end reads/sample) to obtain a high degree of sequence coverage. The metatranscriptomic analysis obtained 22,115,512 merged sequences and identified 2,780 microbial lineages after singleton removal.

Composition and function of the nasopharyngeal microbiome

Nasopharyngeal microbiome was dominated by M. catarrhalis (32%), followed by other bacteria including S. mitis (7%), S. pneumoniae (6%), Prevotella spp. (5%), P. melaninogenica (5%), and H. influenzae (4%). Comparing the α-diversity between the two groups, Shannon and Simpson indices were generally higher in the RSV group but there were no significant differences (P>0.05; Supplemental Figure S1 [online]). By contrast, at the individual taxon level, the abundance of 52 microbial species were significantly different between the virus groups (q<0.05; Supplemental Figure S2 [online]), including several representatives of the some genera, Moraxella and Staphylococcus.

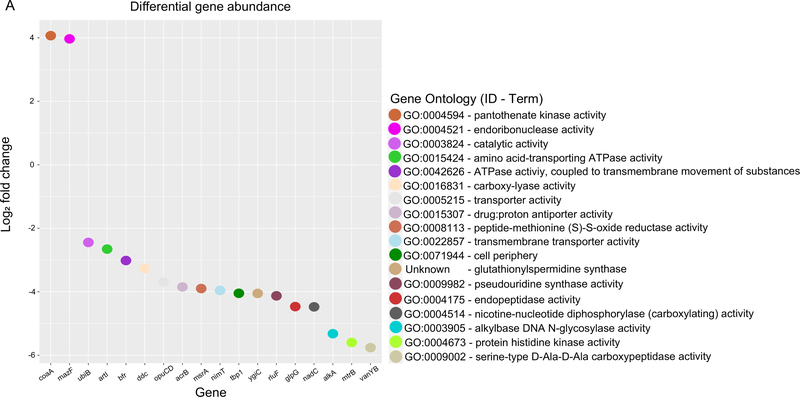

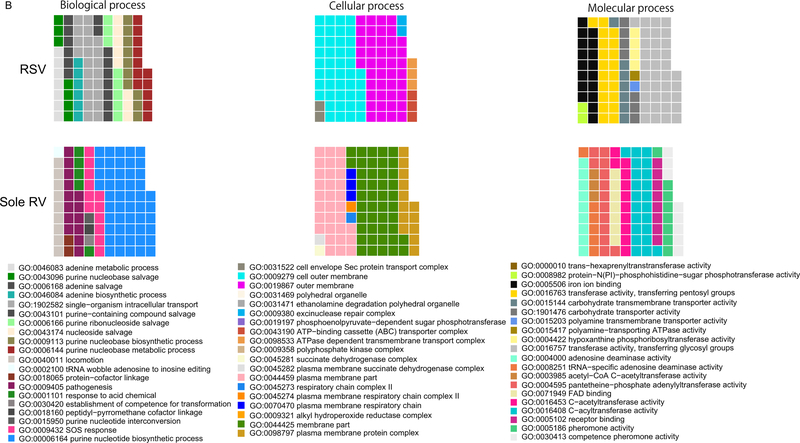

The functional profiling identified 18 differentially-expressed microbial genes between the virus groups (q<0.05; Figure 1A [online]). In the RSV group, two genes were upregulated—coaA and mazF, which are involved in pantothenate kinase and nucleic acid metabolism activities, respectively. By contrast, in the sole RV group, 16 genes were upregulated (e.g., ddc involved in carboxylyase activity). Similarly, the GO-level analysis demonstrated different top ontology terms between the virus groups (Figure 1B and Supplemental Table S2 [online]). While some GO terms were shared between the virus groups (e.g., nucleobase biosynthetic process), most of the enriched terms were exclusive to each group, indicating functional differences in the microbiome by infecting virus. Indeed, the RSV group was enriched with nucleic acid-related metabolism (e.g., adenine metabolic process [GO: 0046083], purine-nucleobase compound salvage [GO:0043096]; q<0.05). By contrast, the sole RV group was enriched with acylation and acetylation activities (e.g., C-acyltransferase activity [GO: 0016408], C-acetyltransferase activity [GO: 0016453] activities; q<0.05).

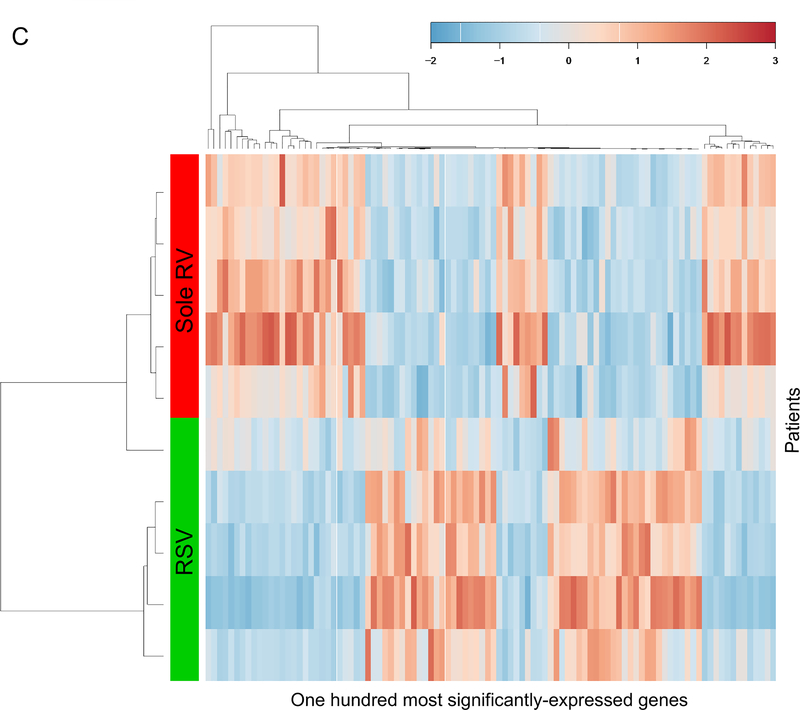

FIGURE 1. Nasopharyngeal airway microbiome function and host response between five respiratory syncytial virus and five sole rhinovirus bronchiolitis.

A. Microbial gene abundance. Differential microbial gene expression in the nasopharyngeal airway between the RSV and sole RV groups. Upregulated genes in the RSV group are represented by positive log2 fold changes, while upregulated genes in the sole RV group are represented by negative log2 fold changes. Color represents Gene Ontology terms associated with the genes.

B. Top Gene Ontology terms of the nasopharyngeal microbiome. The waffle plots show the top ontology (biological process, cellular component, and, molecular function) terms within each of the two groups. The number of squares indicates the importance of the function within each group. The majority of the enriched terms differ between the groups.

C. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the 100 most differentially-expressed host genes. The gene expression profiles separated infants with RSV bronchiolitis from those with sole RV bronchiolitis. The color bar indicates the standardized expression of each gene to a mean of 0. Upregulated genes have positive values and are displayed as red. Downregulated genes have negative values and are displayed as blue. The differences in gene expression between RSV and sole RV are summarized in Supplemental Table S3.

Abbreviations: RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus

Host gene expression in the nasopharyngeal airway

The unsupervised hierarchical clustering using the transcriptomics data segregated infants from each viral group (Figure 1C). Between the virus groups, 269 genes were differentially expressed (q<0.05; Supplemental Table S3 [online]). For example, compared to the RSV group, the RV group had higher expression of DEFA1 and MAP3K14, both of which are involved in innate immunity. Likewise, the pathway enrichment analysis revealed differentially-enriched signaling and metabolic pathways between the groups (Supplemental Table S4 [online]). For example, the RV group had 49 significantly-enriched pathways (q<0.05)—e.g., Toll-like receptor (hsa04620), NOD-like receptor (hsa04621), RIG-I-like receptor (hsa04622), T cell receptor (hsa04660), and JAK-STAT (hsa04630) signaling pathways—suggesting the virus-specific differential activation of innate immunity with a transition to adaptive immunity in infants with bronchiolitis.

In this dual-transcriptomics profiling of infants with severe bronchiolitis, RSV and sole RV infection had distinctly different nasopharyngeal microbiome composition and function profiles (e.g., enriched nucleic acid metabolism in the RSV group vs. acylation/acetylation function in the RV group), as well as differences in host transcriptome profile (e.g. upregulated innate immunity pathways in the RV group). These observations lend an additional support to the emerging concept that bronchiolitis pathobiology is heterogenous,(1) at least between the two major viruses (RSV and RV).

Consistent with the current study, an earlier analysis using16S rRNA gene sequencing demonstrated that the nasopharyngeal microbiome composition differs by virus (e.g., more-abundant Firmicutes bacteria in RSV infection) in infants with severe bronchiolitis.(4) Beyond the composition of the microbiome, our data also suggest differences in its function. For example, infants with RSV infection had enriched nucleic acid metabolism, which may be explained by, at least partially, increased cell turn-over secondary to severe airway inflammation.(14) Additionally, the RV-related enrichment of acylation/acetylation function is in line with recent metabolomics research showing virus-specific signatures—e.g., increased abundance of N-acetyl amino acids in infants with RV bronchiolitis.(8) Taken together, these data suggest potential cross-talk between respiratory viruses and airway microbiome, with downstream functional effects in the airway.

Furthermore, in agreement with the observed up-regulation of host innate immunity signaling (e.g., Toll-like receptor, NOD-like receptor, RIG-I-like receptor signaling) and T cell receptor signaling in the RV group, an earlier analysis of nasal airway microRNA and mRNA in infants with bronchiolitis also showed that RV infection had unique microRNA profile upregulating NFκB signaling(7)—a key regulator for innate and adaptive immune response. Another study also reported that, within children with RSV infection, unique nasopharyngeal airway microbiome profile (through 16S rRNA gene sequencing) is associated with differential regulation of genes related to Toll-like receptor in blood.(5) The current study utilizing a novel dual-transcriptomic approach corroborates these earlier studies, and extends them by simultaneously determining the virus-specific microbiome function and host response signatures in the airway of infants with bronchiolitis.

The present study has several potential limitations. First, bronchiolitis involves inflammation of the lower airways in addition to the upper airways. While our analyses relied on nasopharyngeal samples, studies have shown that the upper airway sampling provides reliable representation of the lung microbiome(15) and transcriptome profiles.(16) Second, the limited sample size of this current proof-of-concept study precluded us from evaluating the role of RSV/RV co-infection compared to sole infection and from making robust inferences. Third, we did not have a “healthy control” group. Yet, the study objective was not to evaluate the role of metatranscriptome and transcriptome on the development of bronchiolitis (yes/no), but to examine virus-specific (RSV vs. RV) pathobiology within this high-risk population. Lastly, our inferences may not be generalizable beyond infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis. Yet, our findings are directly relevant for infants with severe bronchiolitis which accounts for 130,000 hospitalizations in the U.S. each year.(1)

In summary, based on the dual-transcriptomics analysis in infants with bronchiolitis, we found that RSV and sole RV infection had distinct microbiome composition and function, as well as host response, profiles. In conjunction with earlier studies, our findings suggest that the bronchiolitis pathobiology differs between RSV and RV infection. The current pilot study lends support to the use of dual-transcriptomic approach, which has a potential to delineate the integrated contributions of the airway microbiome and host to bronchiolitis pathobiology. In conjunction with existent evidence—the data should not only inform future adaptive clinical trials (e.g., the use of microbiome and host data as biomarkers) but also facilitate investigations into the development of treatment strategies (e.g., modification of microbiome, immunomodulators) in infants with bronchiolitis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: The current study is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD): R01 AI-127507, R01 AI-134940, R01 AI-137091, and UG3/UH3 OD-023253. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. MP-L was partially supported by the Margaret Q. Landenberger Research Foundation, the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Award Number UL1TR001876), and the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tegnologia (T495756868-00032862).

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: The authors have indicated that they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hasegawa K, Dumas O, Hartert TV, Camargo CA. Advancing our understanding of infant bronchiolitis through phenotyping and endotyping: clinical and molecular approaches. Expert Rev Respir Med 2016;10(8):891–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mansbach JM, et al. Prospective multicenter study of viral etiology and hospital length of stay in children with severe bronchiolitis. JAMA Pediatr 2012;166(8):700–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ralston SL, et al. Clinical practice guideline: The diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2014;134(5):e1474–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansbach JM, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus severe bronchiolitis are associated with distinct nasopharyngeal microbiota. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;137(6):1909–1913.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Steenhuijsen Piters WAA, et al. Nasopharyngeal microbiota, host transcriptome, and disease severity in children with respiratory syncytial virus infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194(9):1104–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mejias A, et al. Whole blood gene expression profiles to assess pathogenesis and disease severity in infants with respiratory syncytial virus infection. PLoS Med 2013;10(11):e1001549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasegawa K, et al. RSV vs. rhinovirus bronchiolitis: difference in nasal airway microRNA profiles and NFκB signaling. Pediatr Res 2018;83(3):606–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart CJ, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus bronchiolitis are associated with distinct metabolic pathways. J Infect Dis 2018;217(7):1160–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pérez-Losada M, Castro-Nallar E, Bendall ML, Freishtat RJ, Crandall KA. Dual transcriptomic profiling of host and microbiota during health and disease in pediatric asthma. PLoS ONE 2015;10(6):e0131819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro-Nallar E, et al. Integrating microbial and host transcriptomics to characterize asthma-associated microbial communities. BMC Med Genomics 2015;8(1):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis OE, et al. Pathoscope: Species identification and strain attribution with unassembled sequencing data. Genome Res 2013;23(10):1721–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrd AL, et al. Clinical PathoScope: Rapid alignment and filtration for accurate pathogen identification in clinical samples using unassembled sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 2014;15(1):262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong C, et al. PathoScope 2.0: A complete computational framework for strain identification in environmental or clinical sequencing samples. Microbiome 2014;2(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanada S, Pirzadeh M, Carver KY, Deng JC. Respiratory viral infection-induced microbiome alterations and secondary bacterial pneumonia. Front Immunol 2018;9:2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marsh RL, et al. The microbiota in bronchoalveolar lavage from young children with chronic lung disease includes taxa present in both the oropharynx and nasopharynx. Microbiome 2016;4(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poole A, et al. Dissecting childhood asthma with nasal transcriptomics distinguishes subphenotypes of disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133(3):670–678.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.