Abstract

Influenza viruses are respiratory pathogens of public health concern worldwide with up to 650,000 deaths occurring each year. Seasonal influenza virus vaccines are employed to prevent disease, but with limited effectiveness. Development of a universal influenza virus vaccine with the potential to elicit long-lasting, broadly cross-reactive immune responses is necessary for reducing influenza virus prevalence. In this study, we have utilized lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated, nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccines to intradermally deliver a combination of conserved influenza virus antigens (hemagglutinin stalk, neuraminidase, matrix-2 ion channel, and nucleoprotein) and induce strong immune responses with substantial breadth and potency in a murine model. The immunity conferred by nucleoside-modified mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccines provided protection from challenge with pandemic H1N1 virus at 500 times the median lethal dose after administration of a single immunization, and the combination vaccine protected from morbidity at a dose of 50 ng per antigen. The broad protective potential of a single dose of combination vaccine was confirmed by challenge with a panel of group 1 influenza A viruses. These findings support the advancement of nucleoside-modified mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccines expressing multiple conserved antigens as universal influenza virus vaccine candidates.

Keywords: influenza virus, vaccine, mRNA, nucleoside-modification, lipid nanoparticle, universal vaccine

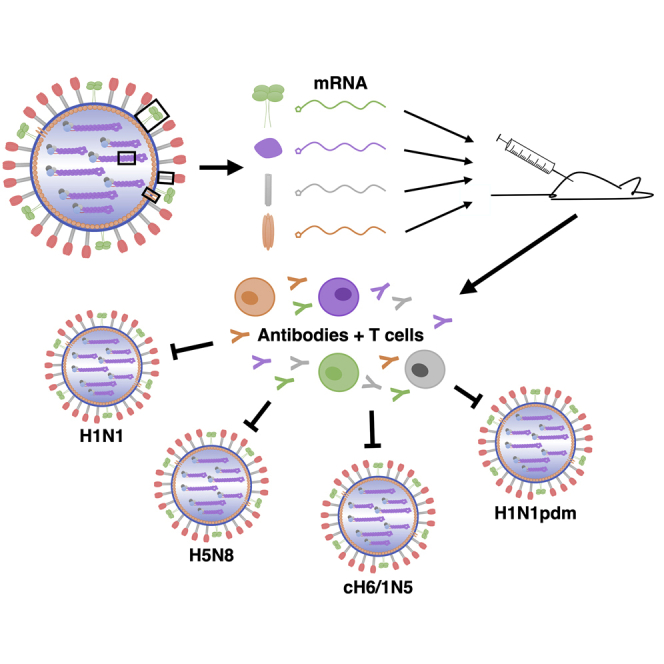

Graphical Abstract

Conserved influenza virus antigens delivered by mRNA-based vaccines were shown to provide protection from a diverse panel of influenza A virus challenge strains in a murine model. These data support the further development of this approach as a universal influenza virus vaccine.

Introduction

Influenza viruses cause substantial morbidity and mortality in humans across the globe, leading to the death of more than half a million individuals annually.1 Vaccination is the most common preventative measure utilized, but current influenza virus vaccines remain imperfect and do not provide broad and durable protective immunity. Quadrivalent inactivated influenza virus vaccines (QIVs) are most commonly administered to the public, but effectiveness of these vaccines lies in the range of 10%–60% due to a variety of factors, including poor immunogenicity and strain mismatches.2,3 In addition, seasonal vaccines are formulated to aid in protection from influenza viruses circulating in the human population, but they provide minimal protection from emerging influenza viruses with pandemic potential.4 Therefore, development of a novel vaccine platform targeting multiple conserved epitopes of influenza viruses capable of providing broadly reactive and long-lasting protection is highly desirable as a candidate for a universal influenza virus vaccine.

Previous work has focused on identifying conserved regions of influenza viruses that can act as targets for the induction of broadly protective humoral and cellular responses. The stalk of the major surface glycoprotein, hemagglutinin (HA), has been the object of much attention due to its ability to elicit broadly reactive neutralizing antibodies, which can protect from infection by influenza viruses displaying a wide variety of HA subtypes.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Importantly, in addition to classical measures of HA-mediated protection such as hemagglutination inhibition,10 antibodies against the HA stalk have been shown to correlate with protection in humans.11, 12, 13 More recently, the influenza virus surface glycoprotein neuraminidase (NA) has raised considerable interest after antibodies to this protein were found to provide protection within a single subtype, and broadly reactive NA-specific antibodies were isolated from human donors.14, 15, 16, 17, 18 The highly conserved matrix-2 (M2) ion channel protein and nucleoprotein (NP) of the influenza virus have also been found to elicit broad protective immune responses through antibody Fc-mediated mechanisms and cellular responses.19, 20, 21, 22 Simultaneous targeting of these proteins with a single vaccine formulation could provide broad immunity that protects against both seasonal influenza viruses and those with pandemic potential.

Nucleoside-modified mRNA-lipid nanoparticle (LNP) vaccines have recently emerged as vaccine vectors displaying many properties desirable for delivery of a universal influenza virus vaccine candidate.23 A single antigen from the virus can be expressed at high levels for an extended period of time, more closely mimicking the dynamics of viral infection.24 The lack of a foreign vector prevents the adaptive immune system from recognizing the input, allowing the potential for multiple rounds of vaccination to achieve a substantial boosting of immune responses. Additionally, production of synthetic mRNA vaccines is egg-independent, removing the reliance on embryonated chicken eggs for influenza virus vaccines. The mRNA vector utilized in this study has been modified to incorporate 1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ), which prevents recognition by RNA sensors, thereby avoiding excess inflammation and increasing protein (antigen) expression.25, 26, 27 mRNA is encapsulated in an ∼80-nm LNP that mimics the size of an influenza virion (Figure 1A).28,29 In this study, we have harnessed the technology of nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP vaccines to effectively deliver a universal influenza virus vaccine candidate that targets a combination of conserved antigens and provides broad protection in mice after administration of a single low dose.

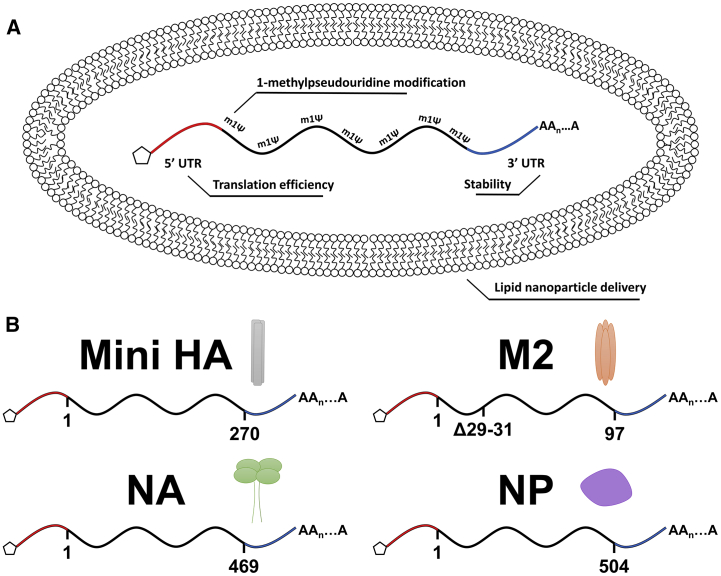

Figure 1.

mRNA-Lipid Nanoparticle Vaccine Platform Utilized for the Delivery of a Combination of Conserved Influenza Virus Antigens

(A) Schematic representation of the mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccine technology that incorporates a 1-methylpseudouridine-modified mRNA molecule into an 80 lipid nanometer vesicle for efficient delivery into host cells upon vaccination. (B) Diagrams illustrating the antigens used as immunogens in this study. Amino acid numbers are included under the mRNA coding for each antigen. Not drawn to scale.

Results

Selection of Universally Protective Influenza Virus Vaccine Antigens

To determine the extent of the variation in influenza virus proteins proposed as antigens for a combination universal influenza virus vaccine, conservation diagrams were produced. Human influenza virus isolates with complete genome sequences from within the H1N1 subtype were selected for each year available, dating back to 1918, to cover known variation. Across the H1N1 subtype, the HA stalk region remains conserved while the head domain shows substantial variability (Figure S1), consistent with previous reports.30,31 The NA head shows a high degree of conservation, solidifying the rationale that vaccination with a high dose of NA protein could provide cross-reactive antibodies within the N1 subtype.14,16 Both the M2 and NP proteins are highly conserved across the subtype, including the exposed M2 ectodomain.

Similarly, sequences were acquired for viruses spanning influenza HA group 1 viruses (H1, H2, H5, H6, H8, H9, H11, H12, H13, and H16) as well as NA group 1 viruses (N1, N4, N5, and N8) not limited by species tropism.32,33 The strong selective pressure on both of these molecules by antibody-mediated immunity is apparent in the small number of conserved domains within group 1 (Figure S1). The HA stalk has some patches of conservation where broadly cross-reactive antibodies have been described to bind.34 The NA active site is also well conserved within group 1 NAs (Figure S1), and cross-reactive antibodies have been reported to bind this site.15 Differences in M2 and NP are mostly found between species,35 and therefore sequences were selected from human, avian, and swine strains to model the breadth of influenza viruses of seasonal and pandemic concern. Both M2 and NP proteins show high levels of conservation compared to the more exposed glycoproteins and were both previously studied as antigens for influenza virus vaccines (Figure S1).20,21,36,37

Therefore, the conservation profile and previous encouraging approaches supported the selection of these four proteins for a combination vaccination approach using nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP vaccines (Figure 1B). To elicit antibodies against the conserved HA stalk domain, a “Mini HA” construct based on the A/Brisbane/59/2007 H1N1 HA and designed to lack the highly variable globular head domain of HA was used.8 The wild-type, membrane-bound NA from A/Michigan/45/2015 H1N1pdm (Mich15) was used to match the currently circulating seasonal influenza virus strain. Similarly, the wild-type NP from Mich15 was used, which matches the currently circulating H1N1 viruses and is overall highly conserved. To elicit immune responses against M2, a construct (based on Mich15) with the amino acid residues 29–31 deleted was used. This mutation was introduced to render the ion-channel activity non-functional and to reduce potential cytotoxicity as a result of overexpression on the cell surface.38 Importantly, the mRNA approach enables encoding of the full-length M2 ion channel, including the transmembrane region, which retains T cell epitopes and could lead to a more natural presentation of the antigen on the cell surface compared to previous vaccination approaches.

Nucleoside-Modified mRNA-LNP Vaccination Elicits Robust Humoral Immune Responses

Protein production from mRNAs encoding Mini HA, NA, and M2 immunogens was confirmed by western blot analyses on cell lysates made from transfected NIH/3T3 cells (Figure S2). Denaturing SDS-PAGE was performed for NA and M2, giving the appropriate band size for an NA monomer and an M2 dimer. Non-denaturing PAGE was performed for the Mini HA construct, giving two bands for both a trimer and a dimer. Production of NP protein in NP mRNA-transfected NIH/3T3 cells was validated by flow cytometry (Figure S3). We then investigated the titers elicited as well as specificity and functionality of serum antibodies produced 28 days after vaccination. Mice were vaccinated with a single dose of nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNPs encoding different conserved influenza virus antigens (combined or individually) or an irrelevant formulation encoding firefly luciferase (Luc) (Figure 2A). In enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), the vaccines were shown to elicit potent antigen-specific antibodies, with similar results observed when the four constructs were administered individually or in combination (Figures 2B–2E).

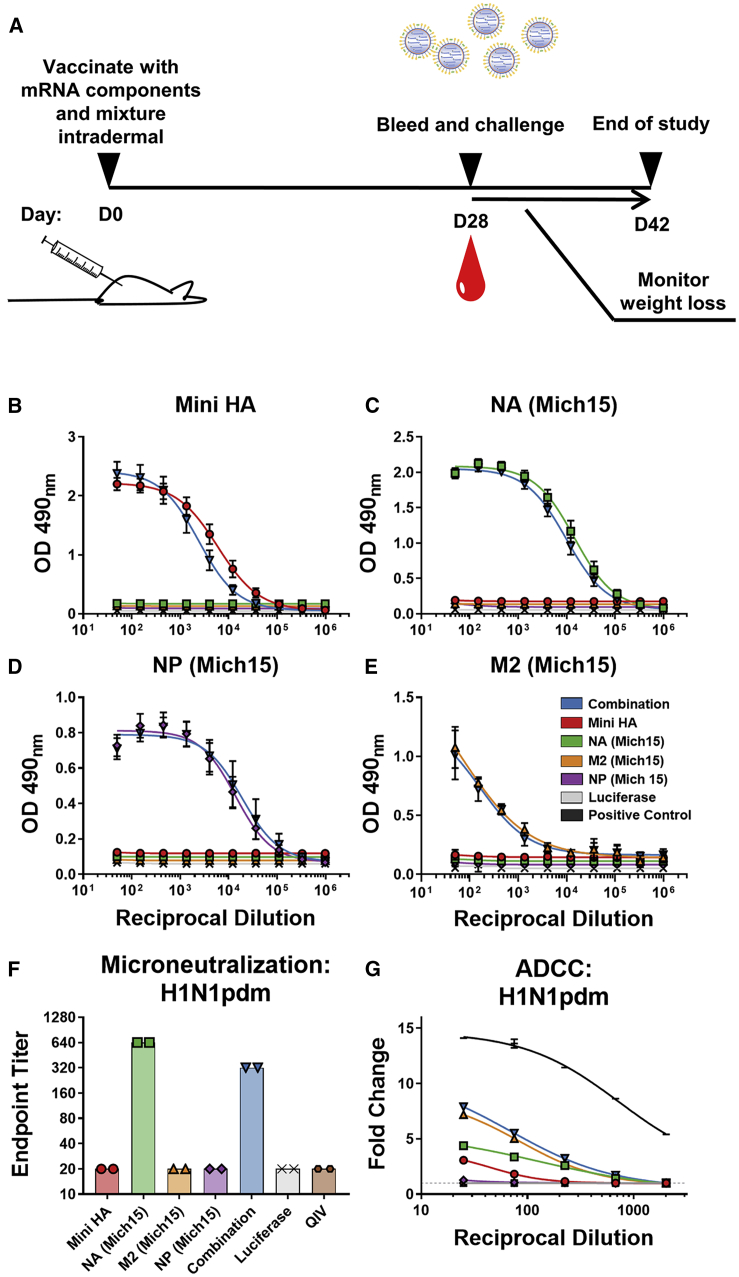

Figure 2.

Nucleoside-Modified mRNA-LNP Vaccines Encoding Conserved Influenza Virus Antigens Elicit Robust Immune Responses in Mice

(A) Mice were vaccinated intradermally once with either monovalent or combined mRNA vaccines (20 μg per antigen). Sera were collected on day 28 post-vaccination, and binding of antibodies to corresponding antigen was measured by ELISA. (B–D) Mean optical density at 490 nm is plotted with SD for each dilution (n = 19–20 individual sera per group) against (B) Mini HA, (C) NA (Mich15), and (D) NP (Mich15). (E) Cell-based ELISAs were utilized to detect antibody binding to M2 (Mich15). Mean optical density at 490 nm is plotted with SD for each dilution displayed with SD (n = 4 repeats of pooled sera). (F) Endpoint titers of a multi-cycle microneutralization assay to determine the neutralization potential of antibodies elicited by vaccination. Sera from mice taken 4 weeks after vaccination with 1.5 μg of the 2018–2019 quadrivalent influenza virus vaccine (QIV) were included in this assay. Sera were pooled and run in duplicate against H1N1pdm virus. (G) ADCC activities of sera were measured using a reporter assay to determine engagement with the mouse FcγRIV. The positive control used was anti-influenza A group 1 monoclonal antibody KB2.39 Luminescence was measured and data from pooled sera run in triplicate are represented as fold change over background (average of negative wells plus 3 times the SD, indicated as a dashed line) with SD. Curves were fit using a nonlinear regression formula log(agonist) versus response minus variable slope (four parameters).

To further assess the functionality and potency of vaccine-elicited antibodies, a multicycle neutralization assay was performed using a vaccine strain for the current seasonal H1N1pdm virus (Figure 2F). The NA component of the vaccine was found to elicit high neutralizing titers, even in the context of a combination approach. While NA-specific antibodies generally do not interfere with virus entry, the multicycle assay used can also detect antibodies that interfere with virus egress, which is the likely mechanism of action. In contrast, sera from the NP, M2, and Mini HA vaccination groups did not show neutralization in the assay. NP is not exposed on the virion surface and therefore would not be expected to elicit neutralizing antibodies. M2-specific antibodies have been previously shown to lack neutralizing functionality, but to mediate protection through Fc functions.40 Although HA stalk antibodies can exhibit neutralizing activity, repeated administrations may be required to elicit these antibodies in a naive animal model. Similar to M2-specific antibodies, HA stalk-specific antibodies have been shown to confer Fc-mediated protection in vivo.11 Additional microneutralization assays were performed using the complete panel of viruses represented in this study, with neutralization found to only be detectable with virus strains bearing a completely matched NA (Figure S4).

To assess the ability of serum antibodies to elicit Fc-mediated effector functions, a murine antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) reporter assay was utilized.41,42 Sera from M2-encoded mRNA-LNP-vaccinated mice showed the strongest activity in the ADCC reporter assays (Figure 2G; Figures S5 and S6). Lower responses were observed in groups immunized with the monovalent NA or Mini HA mRNA-LNP vaccines, and no activity was detected in mice given NP mRNA-LNP vaccine alone.

In addition, the sera were tested against a purified stock of the H1N1pdm virus by ELISA in order to determine the binding of serum antibodies to virion particles rather than individual recombinant proteins (Figure 3A). The strongest binding was observed in groups that received NA and NP vaccines, revealing a strong antibody response to the internal NP. Sera from Mini HA-vaccinated mice showed lower binding, again indicating that repeated vaccinations may be required for strong affinity maturation of HA stalk-specific antibodies. Sera from M2-vaccinated mice showed the weakest reactivity to whole virus, likely due to the low prevalence of M2 on the virion surface.43 The combination vaccine did not result in higher reactivity to the virion, although antigen saturation may have been achieved by the NA- and NP-specific antibodies.

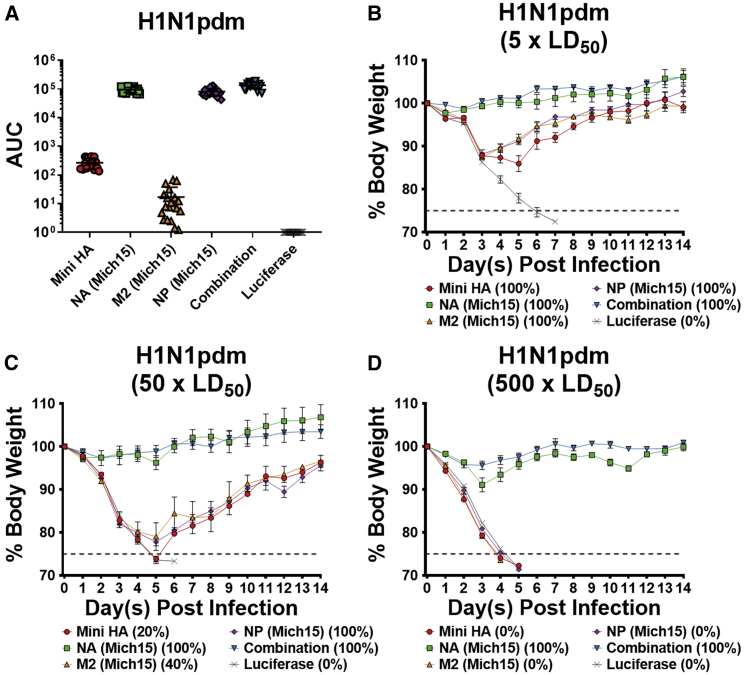

Figure 3.

Vaccination with a Combination of Nucleoside-Modified mRNA-LNP-encoded Influenza Virus Antigens Protects Mice from a Highly Lethal Dose of Matched Challenge Virus

(A) Sera collected 28 days after mRNA-LNP vaccination were measured against H1N1pdm virus. Individual data are represented as AUC with lines indicating mean and SD of responses (n = 19–20 per group). (B–D) Mice were challenged with (B) 5 × LD50, (C) 50 × LD50, or (D) 500 × LD50 of H1N1pdm and weight loss was monitored for 14 days. Data are shown as mean and SEM (n = 5 per group). Mortality is reported as the percentage of surviving mice for each group.

Overall, the antibodies elicited by nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP vaccines are antigen-specific, bind to virus, and show functionality in multiple assays.

Nucleoside-Modified mRNA-LNP-Vaccinated Mice Are Protected from Challenge with Influenza Virus

Twenty-eight days after a single intradermal (i.d.) vaccination, mice were challenged with an influenza virus H1N1pdm challenge strain (Figure 2A). I.d. vaccination was chosen due to previous studies showing increased duration of antigen expression and immunogenicity after using this route of administration.24 All animals vaccinated with the monovalent or combined influenza virus vaccines survived challenge with 5 × 50% lethal dose (LD50) of virus, albeit with some morbidity in the Mini HA, M2, and NP groups (Figure 3B). All mice vaccinated with Luc mRNA-LNPs at the same dose did not survive infection. Due to a complete lack of morbidity in both the NA-only and combination vaccine groups, additional challenge experiments with higher doses of virus (50 and 500 × LD50) were performed (Figures 3C and 3D). Vaccination with Mini HA, M2, or NP alone conferred only partial protection at 50 × LD50 and did not protect at 500 × LD50. The NA-only vaccine prevented mortality in mice at both high-dose challenges. A trend toward improved protection with the combination vaccine compared to NA only could be observed at the highest infection dose (Figure 3D). However, this is strong support for NA-based protection in a vaccine-matched challenge virus setting.

Nucleoside-Modified mRNA-LNP Vaccine-Induced Protection from Influenza Virus Challenge Is Mediated Primarily by Antibodies

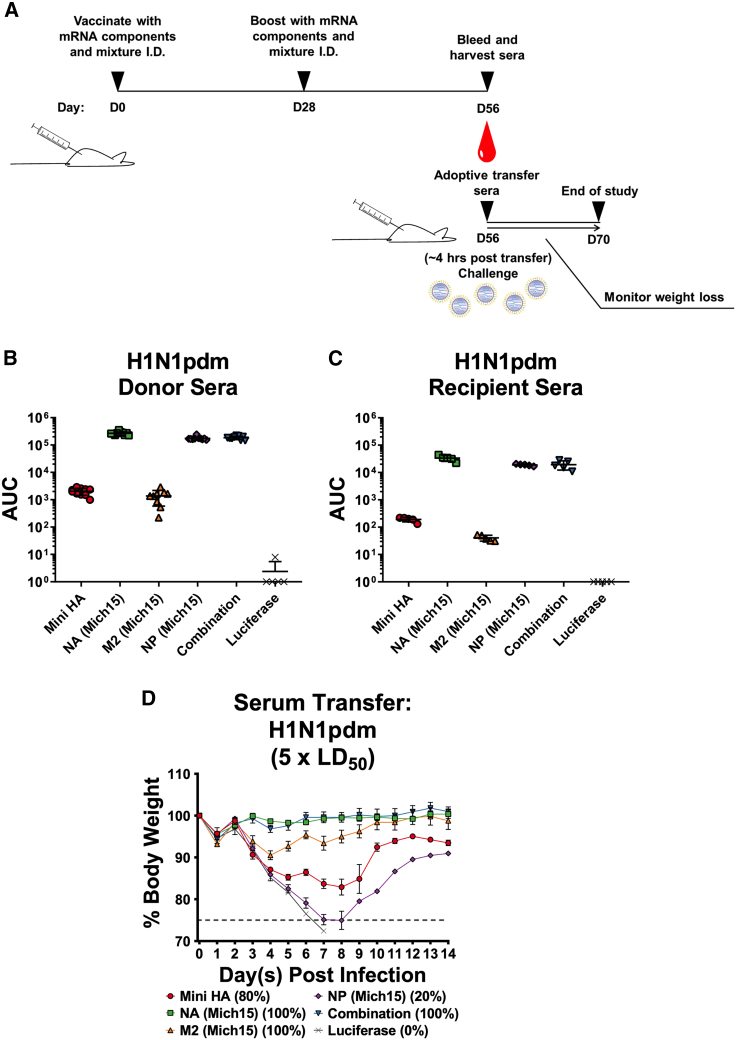

To determine which components of the immune system contributed to protection, an adoptive transfer system was established. Mice were vaccinated twice with 10 μg of mRNA-LNP vaccines (single and combined formulations) with 4-week intervals between administrations to generate strong immune responses (Figure 4A). Mice were then euthanized 4 weeks after the boost and a terminal bleed was performed to collect sera. Spleens were also extracted from immunized animals, and splenocytes were isolated and pooled after red blood cell lysis for adoptive transfer experiments using naive mice. Serum from the terminal bleeds was tested against purified H1N1pdm virus by ELISA and shown to be highly reactive (Figure 4B). This serum was then pooled and transferred into naive mice through intraperitoneal administration. Concurrently, additional groups of naive mice were adoptively transferred 80 million splenocytes from the immune-primed hosts through the intravenous route. Two hours after transfer, sera from the recipient mice were harvested and subsequently tested by ELISA (Figure 4C). The sera tested reacted similarly to the pre-transfer sera, although a loss of response was noted, due to the low volume (200 μL) of transfer relative to the total blood volume of a mouse (∼2 mL). Animals were then challenged with 5 × LD50 of H1N1pdm virus and weight loss was monitored for 14 days. Animals that received serum from mice vaccinated with the combination of antigens or the NA component of the vaccine alone were protected from challenge (Figure 4D), while those receiving Mini HA or M2 alone saw morbidity and partial protection. Mice that received sera from NP-immunized donors showed severe morbidity and mortality. After splenocyte transfer, all animals succumbed to infection (Figure S7), with no protection from morbidity or mortality observed.

Figure 4.

Nucleoside-Modified mRNA-LNP-Vaccine-Induced Protection from Influenza Virus Challenge Is Mediated Primarily by the Humoral Arm of the Immune System

(A) Mice were vaccinated twice (4-week intervals) intradermally with 10 μg of mRNA-LNPs. Animals were euthanized on day 56 after initial vaccination and sera were collected and transferred into naive mice. Two hours after transfer, recipient mice were infected with 5 × LD50 of H1N1pdm (IVR-180) and weight loss was monitored for 14 days. (B) ELISAs were performed to measure the ELISA reactivity of sera from hyper-immune mice to H1N1pdm before transfer (n = 9–10 per group). Lines indicate mean and SD. (C) Sera were pooled, transferred into naive mice, and reactivity to H1N1pdm was measured by ELISA from sera taken 2 h after transfer (n = 5 per group). Lines indicate mean and SD. (D) Weight loss curves of mice that received hyper-immune sera. Average weight loss with SEM is plotted (n = 5 per group). Mortality is reported as the percentage of surviving mice for each group.

Overall, these results show that immunity elicited by nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP vaccines is primarily antibody mediated. However, the adoptive splenocyte transfer approach may not be sensitive enough to detect cell-mediated protection, which likely contributes to the stronger effect observed for NP in the direct challenge setup.

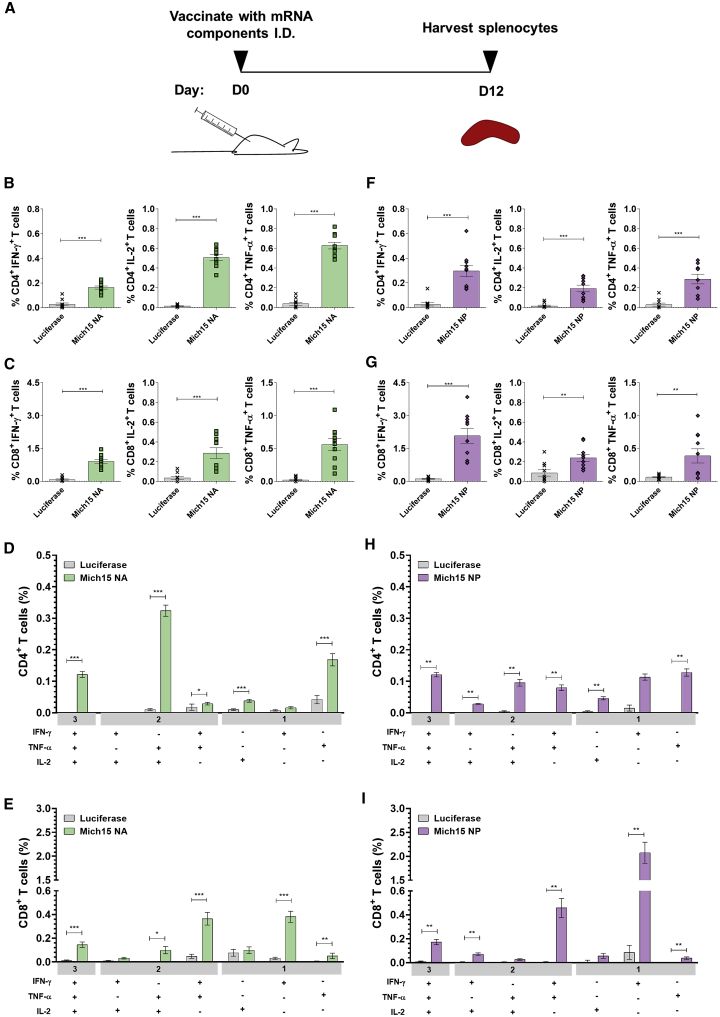

To determine the induction of cellular immune responses elicited by vaccination with nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNPs, CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses were evaluated. The immune responses elicited in mice after vaccination with nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNPs has been previously reported to induce high frequencies of antigen-specific CD4+ helper T cells, which stimulate a strong germinal center B cell reaction and subsequent antibody production.27 In line with these findings, polyfunctional CD4+ T cell responses and strong CD8+ T cell activation to NA were measured in mice 12 days after a single i.d. immunization with 20 μg of NA mRNA-LNPs (Figures 5A–5E; Figure S8). We could also measure potent NP-specific CD8+ T cell activation followed by i.d. administration of a single dose of 20 μg of NP mRNA-LNPs (Figures 5F and 5I; Figure S8). Therefore, these cellular responses may be playing a role in combatting infection, but the adoptive transfer assay may not have been sensitive enough to detect protective cellular immunity (Figure 4D). These data are consistent with in vivo cell killing assays that demonstrate that mice vaccinated with NP mRNA-LNPs produce a cytotoxic effect on cells loaded with NP peptides and transferred to immunized mice (Figure S9; Data S5). Furthermore, alignment of NP sequences from the vaccine antigen and all challenge viruses used in this study showed complete conservation of the BALB/c NP147–155 immunodominant peptide, which has been shown to contribute to the majority, if not all, of the cellular response to NP antigen in this strain.44

Figure 5.

Nucleoside-Modified Neuraminidase and Nucleoprotein mRNA-LNP Vaccines Elicit Robust Antigen-Specific T Cell Responses in Mice

(A) Mice were vaccinated intradermally with a single dose of 20 μg of NA or NP mRNA-LNPs. Splenocytes were stimulated with NA or NP peptides 12 days after immunization, and cytokine production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was assessed by flow cytometry. Percentages of NA-specific (B) CD4+ and (C) CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 and frequencies of combinations of cytokines produced by (D) CD4+ and (E) CD8+ T cells are shown. Percentages of NP-specific (F) CD4+ and (G) CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 and frequencies of combinations of cytokines produced by (H) CD4+ and (I) CD8+ T cells are shown. Values from NA- and NP-immunized mice are compared to values from Luc-immunized animals for each cytokine combination (D, E, H, and I). Each symbol represents one animal and error is shown as SEM (n = 10 mice per group). Data from two independent experiments are shown. Statistical analysis: Mann-Whitney test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Dose De-escalation of Nucleoside-Modified mRNA-LNP Vaccines Shows Protection in the Nanogram Range after Administration of a Single Dose

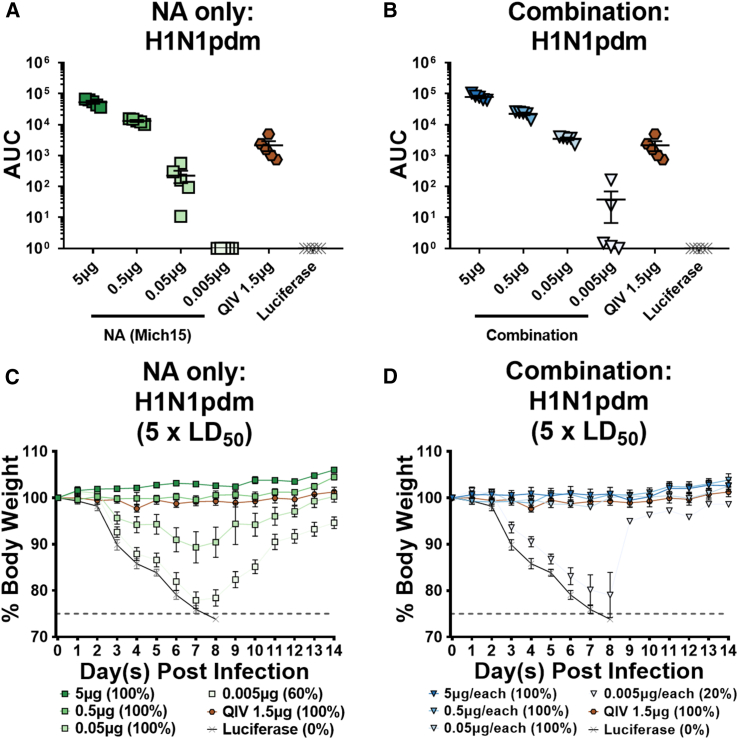

Mice were vaccinated with decreasing doses of either NA alone or NA in addition to the Mini HA, M2, and NP constructs (combination). Matched, seasonal QIV was administered intramuscularly (i.m.) as a “standard of care.” Twenty-eight days after vaccine administration, mice were bled and sera were analyzed by ELISA against purified H1N1pdm virus. Mice given NA alone showed responses to purified virus with a dose as low as 0.050 μg of mRNA, with responses reaching undetectable levels at the 0.005-μg dose (Figure 6A). The sera from mice vaccinated with the combination vaccine were more reactive by ELISA at similar doses, which can be explained by the additional antigens administered in addition to the NA (Figure 6B). Responses were consistently detectable at the 0.05-μg (per antigen) dose, and two serum samples reacted above background at the 0.005-μg dose. Mice were then challenged with 5 × LD50 of H1N1pdm virus and weight loss was monitored for 14 days. All NA-vaccinated mice were protected from infection at the 0.5-μg dose, with no morbidity or mortality observed (Figure 6C). Some morbidity was observed at the 0.05-μg dose, but all mice survived the challenge. At the 0.005-μg dose, mice either succumbed to the infection or lost nearly 25% of their body weight before recovering. In the combination vaccination group, the protection was more potent, with no morbidity or mortality noted in mice immunized with 0.05 μg per antigen of mRNA-LNP vaccine (Figure 6D). Four out of five mice given 0.005 μg for each antigen succumbed to infection. One mouse only lost 10% of initial body weight and was identified as the highest responder by ELISA. In summary, vaccination with a single low dose of 0.05 μg of NA nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP alone can protect animals from morbidity and mortality with an NA-matched challenge strain, while the addition of Mini HA, M2, and NP antigens further contribute to this protection to ameliorate morbidity at this dose. Importantly, note that this low-dose NA-mediated protection is likely due to the complete match between the antigen and the challenge virus strain.

Figure 6.

The Combination of Nucleoside-Modified mRNA-LNP-Encoded Influenza Virus Antigens Enhances Porteection of NA-Mediated Immunity in the Nanogram Range

Serum from mice vaccinated with a single intradermal dose of 5, 0.5, 0.05, or 0.005 μg of nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNPs of either (A) NA alone or (B) supplemented with Mini HA, M2, and NP constructs additively (combination) were tested against H1N1pdm in ELISA assays. Luciferase mRNA-LNP was used as a negative control at a dose of 5 μg, and quadrivalent inactivated influenza virus vaccine (QIV) was used as a standard of care control at a dose of 1.5 μg. Data are represented as AUC with the mean and SD plotted. (C and D) Mice were infected with 5 × LD50 of H1N1pdm virus and body weight was monitored for 14 days. Weight loss curves after infection for mice vaccinated with NA alone or a combination of antigens. Luciferase and QIV groups are shown in both graphs. Mean plus SEM is plotted for each group (n = 5 per group). Mortality is reported as the percentage of surviving mice for each group.

A Single Immunization with Nucleoside-Modified mRNA-LNP Influenza Virus Vaccines Induces Protection from a Broad Range of Group 1 Influenza A Viruses

To assess the potential of this vaccination approach to provide protection from group 1 influenza viruses, a broad panel of challenge viruses was utilized. Mice were vaccinated in a prime-only regimen, as described above. Twenty-eight days after vaccination, mice were bled to determine the reactivity of sera against the corresponding purified viruses by ELISA (Figures S10 and S11). H1N1 subtype viruses isolated before the 2009 pandemic, influenza viruses with avian glycoproteins, and a current H3N2 strain were tested to determine the level of cross-reactivity (Table 1). A/New Caledonia/20/1999 H1N1 (NC99) and A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 H1N1 (PR8) viruses were chosen due to the relative distance of these viruses from one another within the pre-pandemic H1N1 subtype.32 Influenza virus strains were selected to represent group 1 breadth of protection for both HA and NA, including recombinant viruses in a PR8 backbone bearing an avian H6 head domain and H1N1pdm stalk domain coupled with an avian N5 glycoprotein (cH6/1N5), a low-pathogenicity avian H5 and avian N8 (H5N8), or an avian H9 and avian N2 (H9N2). Interestingly, high NP-specific antibody responses were seen in all cases, highlighting both the high conservation of NP and also the potential that NP protein is secreted during viral replication or that virions are denatured on the ELISA plate, exposing NP-coated ribonucleoparticles.45,46

Table 1.

Amino Acid Identity between Modified Vaccine Antigens and Corresponding Influenza Virus Proteins

| Mini HA (%) | NA (%) | M2 (%) | NP (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVR-180 | 77.8 | ~100 | 83.0 | 90.4 |

| Mich15 | 77.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NC99 | 87.0 | 81.7 | 81.9 | 89.6 |

| PR8 | 81.5 | 82.6 | 86.2 | 91.2 |

| cH6/1N5 | 77.4 | 52.5 | 86.2 | 91.2 |

| H5N8 | 65.1 | 52.5 | 86.2 | 91.2 |

| H9N2 | 55.6 | 43.6 | 86.2 | 91.2 |

| H3N2 | 44.6 | 43.9 | 83.0 | 89.0 |

Amino acid sequences from vaccine antigens were aligned to appropriate proteins from influenza virus challenge strains using the Clustal Omega multiple sequence alignment tool.47 Percent amino acid identity was determined using the computed percent identity matrix and examined for each virus used. Please see Data S1. HA Alignment, Data S2. M2 Alignment, Data S3. NA Alignment, Data S4. NP Alignment.

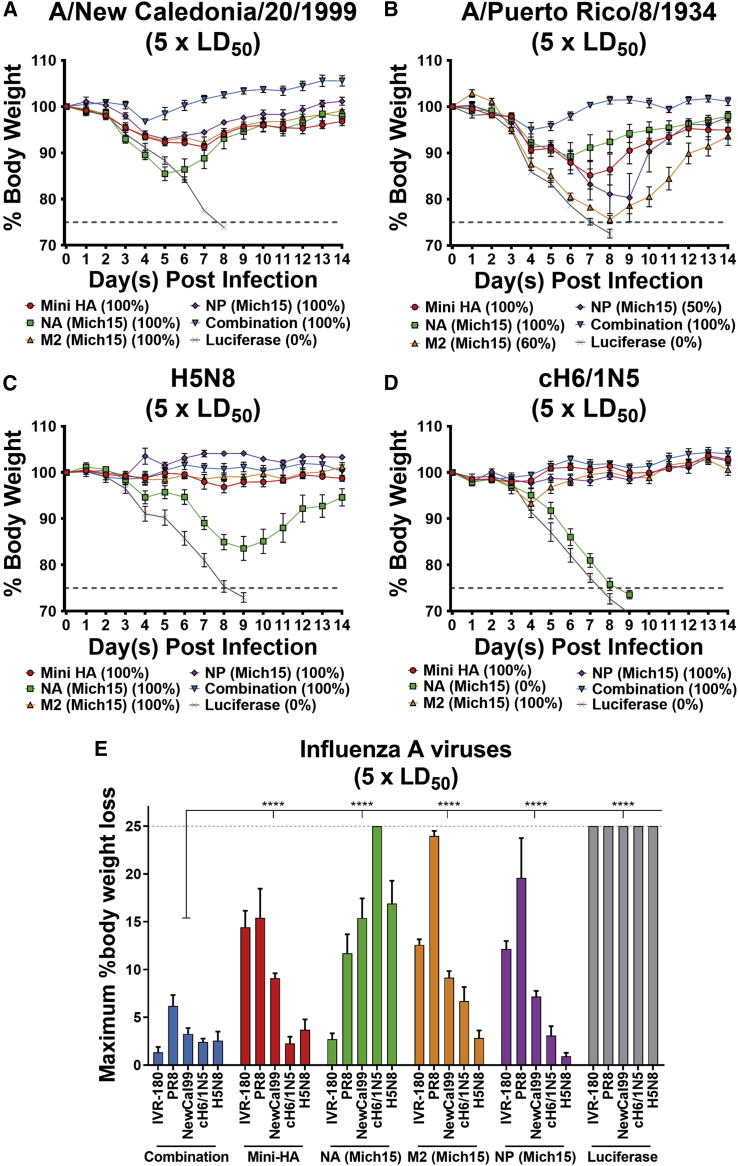

Mice were challenged with influenza viruses selected from this broad panel and weight loss was monitored to observe morbidity and mortality. For viruses of the H1N1 subtype, morbidity was observed in animals immunized with the single-component vaccines, although all mice survived the challenge with NC99 virus (Figure 7A) and some mortality was observed after challenge with PR8 virus (Figure 7B). When given a combination of all four influenza virus antigens, mice showed limited morbidity (<5% initial body weight loss) and all survived viral challenge. To further evaluate the breadth of the vaccine response, viruses bearing avian glycoproteins were used for infection. Interestingly, protection mediated by the internal protein components of the vaccine (M2 and NP) as well as that stimulated by Mini HA alone were sufficient to protect mice from morbidity and mortality in infections with H5N8 or cH6/1N5 (Figures 7C and 7D). NA-based responses resulted in complete mortality upon infection with cH6/1N5 and substantial morbidity with H5N8, although all mice survived the challenge. This minimal protection conferred to N5- and N8-bearing viruses was not surprising, as generally NA antibodies do not exceed subtype-specific breadth.16 Weight loss maxima for each individual mouse were compiled into a single graphic to better compare the potency and breadth of protective efficacy elicited by the nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP vaccines (Figure 7E).

Figure 7.

A Single Immunization with a Combination of Nucleoside-Modified mRNA-Encoded Influenza Virus Antigens Protects Mice from Heterologous Challenge

Twenty-eight days after a single intradermal vaccination with 20 μg of mRNA-LNPs, mice were bled and challenged with 5 × LD50 of influenza virus. Weight loss was monitored for 14 days for challenge viruses: (A) A/New Caledonia/20/1999 H1N1 virus (n = 5 per group), (B) A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 H1N1 virus (n = 4–5 per group), (C) H5N8 virus (n = 5 per group), and (D) cH6/1N5 virus (n = 5 per group). Means and SEM are shown for weight loss curves. Mortality is reported as the percentage of surviving mice for each group. (E) Summarized maximum weight loss of all challenge experiments at 5 × LD50 for each respective virus is represented. Mean plus SEM is plotted for each group. Statistical analysis: two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction for multiple comparisons, ∗p < 0.0332, ∗∗p < 0.0021, ∗∗∗p < 0.0002, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP vaccines demonstrated great promise in multiple recent studies, as they induced protective immunity against critical infectious pathogens such as herpes simplex virus-2, human cytomegalovirus, influenza virus, Zika virus, and Ebola virus.27,48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 52, 53, 54 Nucleoside-modified influenza virus mRNA-LNP vaccines encoding a single full-length HA antigen are well studied and induce durable protective immune responses (often after a single immunization) through the induction of potent T follicular helper cell and humoral immune responses in mice.27,55 Although most pre-clinical evaluations of mRNA-LNP vaccines have been performed in the murine model, studies in non-human primates and clinical trials in humans have supported the efficacy and translatability of this approach.56,57 These studies show the ability of pre-clinical data to translate to effective vaccination strategies in the clinic.

Multiple approaches have been explored in the pursuit of developing a universal influenza virus vaccine that would increase both breadth and effectiveness compared to the standard of care QIV. To elicit broadly reactive antibody responses to the influenza HA stalk influenza virus, vaccines have been produced utilizing chimeric HAs with avian head domains,7 recombinant rationally designed mini-HA antigens, which consist only of the HA stalk,8 or hyperglycosylated HA recombinant protein, which focuses the antibody response to pre-determined epitopes.58 Use of a recombinantly produced M2 extracellular domain has shown the potential to induce broadly reactive, Fc-active antibody responses.40 Internal proteins able to stimulate broadly reactive T cell responses have also been pursued using vector-delivered influenza NP and M1.21 These approaches generally focus on one specific aspect of the immune response to influenza virus and may allow exposure to infection should the virus mutate and escape the protective response.

To broaden the protective efficacy and redundancy of these vaccines, in the current study, a nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP influenza virus vaccine was developed to elicit predominantly antibody-based protection to several conserved antigens (HA stalk, NA, M2, and NP) of the influenza virus. When multiple antigens were delivered in combination, no substantial differences in the magnitude of humoral immune responses were detected when compared to a single antigen delivered alone. This solidifies the rationale that multiple individual mRNA-encoded antigens could be combined in a single administration to increase the breadth of immune responses elicited by vaccination, which should provide a protective layer of redundancy should the virus mutate to escape from any singular response. Serum antibodies obtained after a single immunization with the combination vaccine were found to bind a diverse panel of influenza virus strains, including those from the pre-pandemic H1N1 subtype and those bearing glycoproteins from avian isolates. Mice were protected after a single dose of the combination vaccine against infection with seasonal influenza virus, heterologous challenge within the H1N1 subtype (NC99 and PR8), and heterosubtypic challenge with viruses bearing avian glycoproteins (H5N8 and cH6/1N5). Of note, the vast majority of previous influenza virus mRNA vaccine studies used 1- to 80-μg vaccine doses to induce protection in mice.23 Studies using self-amplifying RNA vectors have been able to reduce the effective dose to the nanogram range and are currently being pursued in phase 1 clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04062669).59,60 Our combined vaccine formulation induced protection from seasonal influenza virus challenge after administration of a single dose of 0.05 μg per antigen. This level of protection highlights the potential of this vaccine approach for further development as a universal influenza virus vaccine. This platform should also be considered as a replacement to current seasonal influenza virus vaccines, to allow for increased potency and breadth of responses to annually circulating viruses.

In addition to potency, the nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP vaccine platform has critical advantages over conventional influenza virus vaccines, specifically: (1) rapid, scalable, sequence-independent production of synthetic mRNA vaccines that does not require eggs or cell lines and complicated purification procedures; (2) enormous flexibility of the mRNA vaccine technology that allows combination of several antigen-encoding mRNAs into a single regimen that could result in greater breadth of vaccine protection;48,52,61 and (3) the ability to use several influenza virus antigens (M2 and internal proteins) that can be expressed directly in the cytosol to better recapitulate the expression occurring during infection, which cannot be achieved through administration of recombinant proteins—here we show that the nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP vaccine platform allows us to use M2 and NP (and possibly other antigens) for vaccination to induce broadly protective immune responses.

Individually, a single immunization with the Mini HA component provided protection from all H1N1 challenge strains as well as H5N8 and cH6/1N5 strains, highlighting the breadth of protection provided by the stalk-specific responses. The antibodies functioned to protect in the absence of neutralizing activity, measured by microneutralization assay, but they did show low ADCC-reporter activity. A potential limitation is the likely requirement of affinity maturation for potent HA stalk responses, as demonstrated by the improvement of antibody responses after booster vaccination (Figure S12). Importantly, most humans are already primed for HA stalk responses and could respond more effectively to HA stalk-based vaccines.7 An important benefit of using HA stalk-based constructs is the lack of an antibody response against the immunodominant variable head domain of the HA, which is highly strain-specific, while HA stalk antibodies have been shown to confer protection against very diverse strains.62

Vaccination with NA out-competed all other single components when challenge with a seasonal H1N1pdm strain was performed. Antibodies elicited by this antigen protected mice up to a challenge dose of 500 times the LD50, and with the addition of the other vaccine components, no morbidity was observed (<5%). NA was the only vaccine component that elicited neutralizing antibodies in a multicycle microneutralization assay, and antibodies also were seen to induce modest ADCC activity. Importantly, the vaccine dose could be reduced to 0.05 μg and still elicit complete protection from mortality. Protection from morbidity was demonstrated when additional antigens were included in the vaccine regimen. This low dose of vaccination is promising, as a major limitation to mRNA vaccines has been side effects associated with high doses of LNP, causing inflammation at the injection site.57

The M2 construct designed in this vaccine approach was mutated to ablate ion channel activity to prevent excess cytotoxicity when overexpressed in recipient cells.38 This approach allowed the delivery of the full-length M2 protein as an antigen, which maintains T cell epitopes present in the transmembrane domain.19 Also, the intracellular expression of the M2 results in more efficient presentation of conformational epitopes. M2 is highly conserved, and antibodies tested after vaccination with M2 alone were found to have high ADCC activity. Furthermore, M2 alone prevented mortality in challenge with multiple influenza strains. Although protection was not complete against PR8 virus, morbidity was not observed after challenge with H5N8 or cH6/1N5 virus strains. Interestingly, these viruses all share the same M2 sequence, as well as NP where a similar phenomenon was observed. This is likely due to kinetics of viral replication, which also resulted in delayed weight loss for cH6/1N5 compared to PR8. The initial delay in viral replication may be sufficient for humoral and cellular immunity to clear infected cells before further viral spread occurs.

Due to the sizable global health burden incurred by influenza virus infection, the threat of pandemic outbreaks, and the limited effectiveness of current vaccines, novel vaccine platforms must be developed to mitigate or remove these dangers. Our study shows that a nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP vaccine with the potential to deliver multiple influenza virus antigens can provide the breadth and potency of immune responses necessary to prevent influenza virus infection, warranting the development of this approach as a universal influenza virus vaccine candidate.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The investigators faithfully adhered to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by the Committee on Care of Laboratory Animal Resources Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council. The animal facilities at the University of Pennsylvania and The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai vivarium are fully accredited by the American Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All studies were conducted under protocols approved by the University of Pennsylvania and The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai institutional animal care and use committees.

Viruses, Cells, and Proteins

Influenza A viruses utilized are described as follows. H1N1pdm (IVR-180): recombinant influenza A virus with the HA and NA from A/Singapore/GP1908/2015 H1N1pdm virus and remaining proteins from A/Texas/1/1977 H3N2 virus. Mich15: A/Michigan/45/2015 H1N1pdm virus. NC99: A/New Caledonia/20/1999 H1N1 virus. PR8: A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 H1N1 virus. cH6/1N5: Recombinant chimeric influenza A virus with an HA head domain from A/mallard/Sweden/81/2002 H6N1 virus, HA stalk domain from A/California/04/2009 H1N1pdm virus, NA from A/mallard/Sweden/86/2003 H12N5 virus, and remaining proteins from A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 H1N1 virus. H5N8: recombinant influenza A virus containing a low pathogenic H5 HA, with the polybasic cleavage site removed, from the A/Vietnam/1203/2004 H5N1 virus, the N8 from A/mallard/Sweden/50/2002 H3N8 virus, and remaining proteins from A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 H1N1 virus. H9N2: recombinant influenza A virus with the HA and NA from A/chicken/Hong Kong/G9/1997 H9N2 virus and remaining proteins from A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 H1N1 virus. H3N2: A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 H3N2 virus.

Viruses were propagated in 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs (Charles River Laboratories) after injection of 100 plaque-forming units (PFU) of influenza virus into each egg. Eggs were incubated at 37°C for 48 h or 33°C for 72 h, then left overnight at 4°C. Allantoic fluid was harvested from each egg and spun at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove debris. Resulting supernatant was aliquoted and frozen at −80°C to form a viral stock. To make purified stocks of virus, this supernatant was spun at 125,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C in tubes containing 5 mL of a 30% sucrose solution. The resulting pellet was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), aliquoted, and frozen at −80°C to form a purified stock. Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay.

NIH/3T3 cells (ATCC) were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine (Corning Life Sciences) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone) and 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco) (complete medium). The NIH/3T3 cell line was tested for mycoplasma contamination after receipt from ATCC and before expansion and cryopreservation. Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells and HEK293T cells (ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco), and 1 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES; Gibco).

Expression plasmids (pcDNA3.1) were constructed for a stabilized, trimeric headless H1 (i.e., Mini HA) described by Impagliazzo et al.,8 an N1 NA (A/Michigan/45/2015), or a viral NP (A/Michigan/45/2015) and synthesized by GenScript. The NA construct features an N-terminal signal peptide, a hexahistadine tag, and the vasodilator-stimulating phosphoprotein (VASP) tetramerization domain followed by the NA ectodomain as described previously.63 Mini HA and NP both feature a C-terminal hexahistidine purification tag. Plasmids were transfected into 6 × 107 Expi293F suspension cells (Life Technologies) using 4 μg/mL polyethylenimine (PEI). Supernatants were harvested 96 h post-transfection and recombinant protein was purified from the cell-free supernatant by affinity chromatography using nickel nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (QIAGEN). Expression was confirmed by anti-HIS (Abcam) western blot and, when relevant, the multimerization of recombinant protein was confirmed by ELISA using monoclonal antibodies that recognize conformational epitopes (e.g., CR9114 and FI6). Expression levels were as follows: Mini HA, 15–20 mg/L; N1 and NP, both 1–0.5 mg/L.

mRNA Production

Sequences of A/Michigan/45/2015 H1N1 influenza virus NA, NP, M2 (pUC-ccTEV-Michigan NA-A101, pUC-ccTEV-Michigan NP-A101, pUC-ccTEV-Michigan M2-A101), Crucell Mini HA #4900 (pUC-ccTEV-CRC HA-A101), or firefly Luc (pUC-ccTEV-Luc2-A101) were codon-optimized, synthesized (GenScript), and cloned into the mRNA production plasmid. After ligation into expression vectors, mRNAs were produced using T7 RNA polymerase (MEGAscript, Ambion) on linearized plasmids. mRNAs were transcribed to contain 101-nt-long poly(A) tails. m1Ψ-5′-triphosphate (TriLink) instead of UTP (uridine 5'-triphosphate) was used to generate modified nucleoside-containing mRNA. Capping of the in vitro-transcribed mRNAs was performed co-transcriptionally using the trinucleotide cap1 analog, CleanCap (TriLink). mRNA was purified by cellulose purification, as described.64 All mRNAs were analyzed by denaturing or native agarose gel electrophoresis and were stored frozen at −20°C.

LNP Formulation of the mRNA

Cellulose-purified m1Ψ-containing RNAs were encapsulated in LNPs using a self-assembly process as previously described wherein an ethanolic lipid mixture of ionizable cationic lipid, phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol, and polyethylene glycol-lipid was rapidly mixed with an aqueous solution containing mRNA at acidic pH.24 The RNA-loaded particles were characterized and subsequently stored at −80°C at a concentration of 1 μg/μL. The mean hydrodynamic diameter of these mRNA-LNPs was ∼80 nm with a polydispersity index of 0.02–0.06 and an encapsulation efficiency of ∼95%.

Staining and Flow Cytometry Analyses of mRNA-Transfected NIH/3T3 Cells and Mouse Splenocytes

1.2 × 105 NP- or Luc mRNA-transfected NIH/3T3 cells were incubated at 4°C for 10 min with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution, then washed with 1× Perm/Wash buffer (both from BD Biosciences). Cells were then incubated at 4°C for 30 min with 1:100 dilutions of an anti-NP mouse monoclonal antibody (Bio X Cell, BE0159) and washed again with 1× Perm/Wash buffer. Finally, cells were incubated at 4°C for 30 min with a 1:900 dilution of a goat anti-mouse (immunoglobulin G [IgG] + IgM) fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibody (Cayman Chemical). After an additional wash, cells were resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (PBS with 2% FBS) and stored at 4°C until analysis. The percentage of NP-positive cells was detected on a modified LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). At least 25,000 events for each sample were recorded, and data were analyzed with the FlowJo 10 software.

Spleen single-cell suspensions were made in complete RPMI 1640 medium. 3 × 106 cells per sample were stimulated for 6 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, in the presence of overlapping NA (BEI Resources, NR-19249) or NP (JPT peptides, PM-INFA-NPH2N2) peptide pools at 5 μg/mL per peptide and an anti-CD28 antibody (1 μg/mL; clone 37.51; BD Biosciences). GolgiPlug (5 μg/mL; brefeldin A; BD Biosciences) and GolgiStop (10 μg/mL; monensin; BD Biosciences) were added to each sample after 1 h of stimulation. Unstimulated samples for each animal were included. A phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate (10 μg/mL) and ionomycin (200 ng/mL; Sigma)-stimulated sample was included as a positive control.

After stimulation, cells were washed with PBS and stained with the LIVE/DEAD fixable aqua dead cell stain kit (Life Technologies) and then surface stained with the monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) anti-CD4 PerCP (peridinin chlorophyll protein)/Cy5.5 (clone GK1.5; BioLegend) and anti-CD8 Pacific Blue (clone 53-6.7; BioLegend) for 30 min at 4°C. After surface staining, cells were washed with FACS buffer, fixed (PBS containing 1% paraformaldehyde), and permeabilized using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences). Cells were intracellularly stained with anti-CD3 allophycocyanin (APC)-Cy7 (clone SP34-2; BD Biosciences), anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy7 (clone MP6-XT22; BD Biosciences), anti-interferon (IFN)-γ Alexa Fluor 700 (AF700) (clone XMG1.2; BD Biosciences), and anti-interleukin (IL)-2 Brilliant Violet 711 (BV711) (clone JES6-5H4; BioLegend) mAbs for 30 min at 4°C. Next, the cells were washed with the permeabilization buffer, fixed as before, and stored at 4°C until analysis.

Splenocytes were analyzed on a modified LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). 500,000 events were collected per specimen. After the gates for each function were created, the Boolean gate platform was used to create the full array of possible combinations, equating to seven response patterns when testing three functions. Data were analyzed with the FlowJo 10 program. Data were expressed by subtracting the percentages of the unstimulated stained cells from the percentages of the peptide pool-stimulated stained samples.

ELISAs

Flat-bottom, 96-well plates (Immulon 4 HBX; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated with either recombinant protein at 2 μg/mL or whole purified influenza virions at 5 μg/mL to a volume of 50 μL per well. Plates were stored overnight at 4°C. The following morning, plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) (Fisher Scientific). 220 μL of blocking buffer (0.5% milk and 3% goat serum [Gibco] in PBS-T) was added to each well and plates were left at room temperature (RT) for 1 h. Blocking buffer was removed from wells, and fresh blocking buffer was added to ensure a final volume of 100 μL per well. Mouse sera were added and a 3-fold serial dilution was performed in the plate, leaving the first and last column blank to account for edge effects. The plate was stored at RT for 2 h. Plates were then washed with PBS-T three times and secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-linked polyclonal goat anti-mouse IgG; Abcam) at a dilution of 1:15,000 was added to each well to a final volume of 50 μL. Plates were left at RT for 1 h, then washed four times with PBS-T with a shaking step included. 100 μL of SigmaFast ο-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride substrate (Sigma) was added and quenched with 50 μL of 3 M hydrochloric acid (Fisher Scientific) after 10 min of development. Plates were read on a Synergy H1 hybrid multimode microplate reader (BioTek) at 490 nm. Data were analyzed using Prism 8.0 (GraphPad), and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using a baseline of the average of all control wells plus 3 times the standard deviation (SD), or 0.07 if the baseline was lower than 0.07. All AUC values below 1 were adjusted to a value of 1. Points showing no reactivity were nudged to ensure that all lines are visible on a single graph.

For cell-based ELISAs, 4 × 104 293T cells were plated in serum-free DMEM in 96-well plates previously coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma). After 24 h of incubation, cells were transfected with 100 ng of pCAGGS-vectored Mich15 M2 (catalytically inactive) using 0.3 μL of TransIT-LT1 (Mirus) per 100 ng of DNA per well. Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (Fisher Scientific) in PBS for 24 h at 4°C before washing with PBS and blocking as above. The procedure was continued as described above, with gentle pipetting used to avoid dislodging cells from the plate.

mRNA Vaccination and Virus Challenge

To determine the appropriate viral challenge dose, an infection using a dose escalation of infectious influenza virus was performed in female BALB/c mice aged 6–8 weeks (Jackson Laboratory). 3 mice were infected from each dose, which ranged from 10 to 105 PFU in log intervals. Mice were anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine mixture, and 50 μL of virus at each dose was introduced through the intranasal route. Weight loss was monitored for 14 days, and mice losing 25% of their initial body weight were humanly sacrificed. The dose at which 50% of mice succumbed to infection was determined as the LD50 for future challenge studies.

Female BALB/c mice aged 6–8 weeks were anesthetized and shaved to expose the skin of the back. After sterilization with 70% ethanol, mRNA vaccines diluted to 10 or 20 μg per 100 μL in PBS were injected i.d. into two sites distant from one another on the back to a total volume of 100 μL. Four weeks after vaccination, mice were anesthetized and infected with 50 μL of influenza virus intranasally. Additionally, mice were bled for serological analysis. Weight loss was monitored for 14 days, and mice that lost more than 25% of initial body weight were humanely euthanized. All mouse experiments were performed according to guidelines stated in the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol.

Passive Transfer of Sera and Splenocytes

Female BALB/c mice aged 6–8 weeks underwent a prime-boost regimen with 10 μg of mRNA vaccine per mouse with 4-week intervals between both vaccinations and subsequent harvest. Mice were anesthetized and then a cardiac puncture was performed to gather whole blood. The blood was allowed to coagulate at room temperature for 1 h before being placed at 4°C for 30 min. Blood was then spun at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and sera were separated from remaining blood components and stored at 4°C until further use. 200 μL of sera was transferred intraperitoneally into naive mice 2–6 hours prior to influenza virus challenge. Mice were bled post-transfer, and sera were tested against the appropriate antigen by ELISA to ensure that the transfer was successful. Spleens were dissected from euthanized mice and processed through a 70-μm filter (Falcon) to dissociate cells, and spleens and cells were placed in RPMI 1640 media (Gibco) on ice throughout this process. Red blood cells were lysed with ACK lysing buffer (Gibco) for 5 min before quenching with PBS. Cleared splenocytes were counted and 80 million cells were intravenously transferred into naive mice 2—4 h prior to influenza virus challenge.

Microneutralization Assay

MDCK cells were plated at a concentration of 2.5 × 104 cells per well in 96-well dishes and incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. Serum samples were treated with a working dilution, following the manufacturer’s guidelines, of receptor-destroying enzyme (RDE) (Seiken) at a ratio of 3:1 overnight in a 37°C water bath. The following morning, RDE-treated serum was incubated with a 2.5% solution of sodium citrate (Fisher Scientific) at 56°C for 30 min at a ratio of 3:4. To bring the sample to a 1:10 dilution, PBS was added at a final ratio of 3:7 with the solution. Assay buffer was made by adding 6-(1-tosylamido-2-phenyl)ethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin at a concentration of 1 μg/mL to Ultra-MDCK media (Lonza). Sera were serially diluted 1:2 in a 96-well plate in assay buffer. Influenza virus IVR-180 was diluted to 100 TCID50 in Ultra-MDCK media. 60 μL of diluted, RDE-treated serum was mixed with 60 μL of virus and allowed to shake at RT for 1 h. In this time, MDCK cells were rinsed with PBS. 100 μL of the serum/virus mixture was then added to the cells and virus was allowed to adsorb to cells for 1 h at 33°C. Virus/serum mixture was then removed and cells were washed with PBS before replacing with media containing serum at the same dilutions and incubating for 72 h at 33°C. A hemagglutination assay was performed by mixing equal volumes of cell supernatant with 0.5% chicken red blood cells (Lampire). Wells in which red blood cells were agglutinated were determined to lack virus, determining the neutralization potential of the sera.

Antibody-Dependent Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity Reporter Assay

MDCK cells were plated in 96-well dishes at a concentration of 2.5 × 104 cells per well and incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. The next morning, influenza virus IVR-180 was diluted to 2.5 × 105 PFU per well in Ultra-MDCK media (MOI of 5 assuming a doubling of cells) and MDCK cells were washed with PBS before the addition of 100 μL of diluted virus in the absence of TPCK-treated trypsin. Infection was allowed to proceed 24 h at 37°C. Assay buffer was prepared by adding 4% ultra-low-IgG FBS (Gibco) to RPMI 1640 (Gibco). Serum samples were serial diluted 3-fold in assay buffer starting at 1:25. Medium was removed from infected MDCK cells, and 25 μL of warm assay buffer was added to each well along with 25 μL of diluted serum. ADCC effector cells (Jurkat cell line expressing the mouse FcγRIV cell-surface receptor; Promega) were rapidly thawed and diluted in warm assay buffer to a concentration of 3 × 106 cells/mL (7.5 × 104 cells per 25 μL) and 25 μL of cell dilution was added to each well and the mixture was allowed to incubate for 6 h at 37°C. Cells and Bio-Glo Luc substrate (Promega) were adjusted to RT, then 75 μL of Luc substrate was added to each well and luminescence was immediately read on a Synergy H1 hybrid multimode microplate reader (BioTek). Fold change was calculated as relative luminescence unit of test wells divided by the average plus 3 times the SD of background wells.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the Prism 6.0 program (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). In Figure 5, data were compared with a Mann-Whitney (two-tailed) test. All p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant with a confidence interval of 95%. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. In Figure 7, data were compared using a two-way ANOVA test with Dunnett’s correction for multiple comparisons. All adjusted p values <0.0332 were considered statistically significant with a confidence interval of 95%. ∗p < 0.0332, ∗∗p < 0.0021, ∗∗∗p < 0.0002, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Author Contributions

R.N., N.P., and A.W.F. conceived the study. R.N., N.P., A.W.F., J.R.d.S., and C.M.B. designed experiments. A.W.F., J.R.d.S., V.C.R., L.C., and R.N. performed experiments. R.N., N.P., A.W.F., J.R.d.S., L.C.d.S.F., D.W., F.K., L.C., and P.P. reviewed and interpreted data. Y.K.T., B.L.M., and T.D.M. contributed to vaccine production. A.W.F. drafted and all authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and gave final approval before submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The Icahn School of Medicine has filed patents on influenza virus vaccines naming R.N., F.K., and P.P. as inventors. In accordance with the University of Pennsylvania policies and procedures and our ethical obligations as researchers, we report that D.W. is named on patents that describe the use of nucleoside-modified mRNA as a platform to deliver therapeutic proteins. D.W. and N.P. are also named on a patent describing the use of modified mRNA in lipid nanoparticles as a vaccine platform. N.P., R.N., P.P., F.K., D.W., and A.W.F. are named on a patent filed on universal influenza vaccines using nucleoside-modified mRNA. We have disclosed those interests fully to the University of Pennsylvania, and we have in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from licensing of our patents. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Angela Choi and Michael Schotsaert for providing the NC99 H1N1 challenge virus and Daniel Stadlbauer for optimization of the microneutralization assay for H1N1pdm (IVR-180) and cH6/1N5 viruses. The study was supported by NIH grant R01-AI146101-01 (to N.P. and R.N.); National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) Collaborative Influenza Vaccine Innovation Centers (CIVIC) contract 75N93019C00051 (to F.K., R.N., and P.P.); a US Public Health Service institutional research training award AI07647 (to A.W.F.); NIH grant 5P01AI097092-07 (“Toward a universal influenza virus vaccine”) (to P.P.); and by funding from BioNTech RNA Pharmaceuticals (to D.W.). J.R.d.S. was a fellow supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) grant 2019/01523-3.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.04.018.

Contributor Information

Norbert Pardi, Email: pnorbert@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

Raffael Nachbagauer, Email: raffael.nachbagauer@mssm.edu.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2020. Influenza (seasonal) fact sheet.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2019. Seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness, 2004–2019.https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/effectiveness-studies.htm [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osterholm M.T., Kelley N.S., Sommer A., Belongia E.A. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012;12:36–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiMenna L.J., Ertl H.C. Pandemic influenza vaccines. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009;333:291–321. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-92165-3_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steel J., Lowen A.C., Wang T.T., Yondola M., Gao Q., Haye K., García-Sastre A., Palese P. Influenza virus vaccine based on the conserved hemagglutinin stalk domain. MBio. 2010;1:e00018-10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00018-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krammer F., Pica N., Hai R., Margine I., Palese P. Chimeric hemagglutinin influenza virus vaccine constructs elicit broadly protective stalk-specific antibodies. J. Virol. 2013;87:6542–6550. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00641-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernstein D.I., Guptill J., Naficy A., Nachbagauer R., Berlanda-Scorza F., Feser J., Wilson P.C., Solórzano A., Van der Wielen M., Walter E.B. Immunogenicity of chimeric haemagglutinin-based, universal influenza virus vaccine candidates: interim results of a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:80–91. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30393-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Impagliazzo A., Milder F., Kuipers H., Wagner M.V., Zhu X., Hoffman R.M., van Meersbergen R., Huizingh J., Wanningen P., Verspuij J. A stable trimeric influenza hemagglutinin stem as a broadly protective immunogen. Science. 2015;349:1301–1306. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yassine H.M., Boyington J.C., McTamney P.M., Wei C.J., Kanekiyo M., Kong W.P., Gallagher J.R., Wang L., Zhang Y., Joyce M.G. Hemagglutinin-stem nanoparticles generate heterosubtypic influenza protection. Nat. Med. 2015;21:1065–1070. doi: 10.1038/nm.3927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobson D., Curry R.L., Beare A.S., Ward-Gardner A. The role of serum haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody in protection against challenge infection with influenza A2 and B viruses. J. Hyg. (Lond.) 1972;70:767–777. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400022610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobsen H., Rajendran M., Choi A., Sjursen H., Brokstad K.A., Cox R.J., Palese P., Krammer F., Nachbagauer R. Influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies in human serum are a surrogate marker for in vivo protection in a serum transfer mouse challenge model. MBio. 2017;8:e01463-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01463-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng S., Nachbagauer R., Balmaseda A., Stadlbauer D., Ojeda S., Patel M., Rajabhathor A., Lopez R., Guglia A.F., Sanchez N. Novel correlates of protection against pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus infection. Nat. Med. 2019;25:962–967. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0463-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhar N., Kwatra G., Nunes M.C., Cutland C., Izu A., Nachbagauer R., Krammer F., Madhi S.A. Hemagglutinin-stalk antibody responses following trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine immunization of pregnant women and association with protection from influenza virus illness. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019:ciz927. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y.Q., Wohlbold T.J., Zheng N.Y., Huang M., Huang Y., Neu K.E., Lee J., Wan H., Rojas K.T., Kirkpatrick E. Influenza infection in humans induces broadly cross-reactive and protective neuraminidase-reactive antibodies. Cell. 2018;173:417–429.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stadlbauer D., Zhu X., McMahon M., Turner J.S., Wohlbold T.J., Schmitz A.J., Strohmeier S., Yu W., Nachbagauer R., Mudd P.A. Broadly protective human antibodies that target the active site of influenza virus neuraminidase. Science. 2019;366:499–504. doi: 10.1126/science.aay0678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wohlbold T.J., Nachbagauer R., Xu H., Tan G.S., Hirsh A., Brokstad K.A., Cox R.J., Palese P., Krammer F. Vaccination with adjuvanted recombinant neuraminidase induces broad heterologous, but not heterosubtypic, cross-protection against influenza virus infection in mice. MBio. 2015;6:e02556. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02556-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eichelberger M.C., Wan H. Influenza neuraminidase as a vaccine antigen. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015;386:275–299. doi: 10.1007/82_2014_398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eichelberger M.C., Morens D.M., Taubenberger J.K. Neuraminidase as an influenza vaccine antigen: a low hanging fruit, ready for picking to improve vaccine effectiveness. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018;53:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng L., Cho K.J., Fiers W., Saelens X. M2e-based universal influenza a vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2015;3:105–136. doi: 10.3390/vaccines3010105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schotsaert M., Ysenbaert T., Smet A., Schepens B., Vanderschaeghe D., Stegalkina S., Vogel T.U., Callewaert N., Fiers W., Saelens X. Long-lasting cross-protection against influenza a by neuraminidase and M2e-based immunization strategies. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24402. doi: 10.1038/srep24402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambe T., Carey J.B., Li Y., Spencer A.J., van Laarhoven A., Mullarkey C.E., Vrdoljak A., Moore A.C., Gilbert S.C. Immunity against heterosubtypic influenza virus induced by adenovirus and MVA expressing nucleoprotein and matrix protein-1. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1443. doi: 10.1038/srep01443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rekstin A., Isakova-Sivak I., Petukhova G., Korenkov D., Losev I., Smolonogina T., Tretiak T., Donina S., Shcherbik S., Bousse T., Rudenko L. Immunogenicity and cross protection in mice afforded by pandemic H1N1 live attenuated influenza vaccine containing wild-type nucleoprotein. BioMed Res. Int. 2017;2017:9359276. doi: 10.1155/2017/9359276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scorza F.B., Pardi N. New kids on the block: RNA-based influenza virus vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2018;6:20. doi: 10.3390/vaccines6020020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pardi N., Tuyishime S., Muramatsu H., Kariko K., Mui B.L., Tam Y.K., Madden T.D., Hope M.J., Weissman D. Expression kinetics of nucleoside-modified mRNA delivered in lipid nanoparticles to mice by various routes. J. Control. Release. 2015;217:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karikó K., Buckstein M., Ni H., Weissman D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005;23:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durbin A.F., Wang C., Marcotrigiano J., Gehrke L. RNAs containing modified nucleotides fail to trigger RIG-I conformational changes for innate immune signaling. MBio. 2016;7:e00833-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00833-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pardi N., Hogan M.J., Naradikian M.S., Parkhouse K., Cain D.W., Jones L., Moody M.A., Verkerke H.P., Myles A., Willis E. Nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccines induce potent T follicular helper and germinal center B cell responses. J. Exp. Med. 2018;215:1571–1588. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parhiz H., Shuvaev V.V., Pardi N., Khoshnejad M., Kiseleva R.Y., Brenner J.S., Uhler T., Tuyishime S., Mui B.L., Tam Y.K. PECAM-1 directed re-targeting of exogenous mRNA providing two orders of magnitude enhancement of vascular delivery and expression in lungs independent of apolipoprotein E-mediated uptake. J. Control. Release. 2018;291:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noda T. Native morphology of influenza virions. Front. Microbiol. 2012;2:269. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thyagarajan B., Bloom J.D. The inherent mutational tolerance and antigenic evolvability of influenza hemagglutinin. eLife. 2014;3:e03300. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fulton B.O., Sun W., Heaton N.S., Palese P. The influenza B virus hemagglutinin head domain is less tolerant to transposon mutagenesis than that of the influenza A virus. J. Virol. 2018;92:e00754-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00754-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nachbagauer R., Choi A., Hirsh A., Margine I., Iida S., Barrera A., Ferres M., Albrecht R.A., García-Sastre A., Bouvier N.M. Defining the antibody cross-reactome directed against the influenza virus surface glycoproteins. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18:464–473. doi: 10.1038/ni.3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krammer F., Fouchier R.A.M., Eichelberger M.C., Webby R.J., Shaw-Saliba K., Wan H., Wilson P.C., Compans R.W., Skountzou I., Monto A.S. NAction! How can neuraminidase-based immunity contribute to better influenza virus vaccines? MBio. 2018;9:e02332-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02332-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee P.S., Wilson I.A. Structural characterization of viral epitopes recognized by broadly cross-reactive antibodies. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015;386:323–341. doi: 10.1007/82_2014_413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhuang Q., Wang S., Liu S., Hou G., Li J., Jiang W., Wang K., Peng C., Liu D., Guo A., Chen J. Diversity and distribution of type A influenza viruses: an updated panorama analysis based on protein sequences. Virol. J. 2019;16:85. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1188-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antrobus R.D., Coughlan L., Berthoud T.K., Dicks M.D., Hill A.V., Lambe T., Gilbert S.C. Clinical assessment of a novel recombinant simian adenovirus ChAdOx1 as a vectored vaccine expressing conserved Influenza A antigens. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:668–674. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coughlan L., Sridhar S., Payne R., Edmans M., Milicic A., Venkatraman N., Lugonja B., Clifton L., Qi C., Folegatti P.M. Heterologous two-dose vaccination with simian adenovirus and poxvirus vectors elicits long-lasting cellular immunity to influenza virus A in healthy adults. EBioMedicine. 2018;29:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watanabe T., Watanabe S., Ito H., Kida H., Kawaoka Y. Influenza A virus can undergo multiple cycles of replication without M2 ion channel activity. J. Virol. 2001;75:5656–5662. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5656-5662.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heaton N.S., Leyva-Grado V.H., Tan G.S., Eggink D., Hai R., Palese P. In vivo bioluminescent imaging of influenza a virus infection and characterization of novel cross-protective monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 2013;87:8272–8281. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00969-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El Bakkouri K., Descamps F., De Filette M., Smet A., Festjens E., Birkett A., Van Rooijen N., Verbeek S., Fiers W., Saelens X. Universal vaccine based on ectodomain of matrix protein 2 of influenza A: Fc receptors and alveolar macrophages mediate protection. J. Immunol. 2011;186:1022–1031. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng Z.J., Garvin D., Paguio A., Moravec R., Engel L., Fan F., Surowy T. Development of a robust reporter-based ADCC assay with frozen, thaw-and-use cells to measure Fc effector function of therapeutic antibodies. J. Immunol. Methods. 2014;414:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi A., Bouzya B., Cortés Franco K.D., Stadlbauer D., Rajabhathor A., Rouxel R.N., Mainil R., Van der Wielen M., Palese P., García-Sastre A. Chimeric hemagglutinin-based influenza virus vaccines induce protective stalk-specific humoral immunity and cellular responses in mice. Immunohorizons. 2019;3:133–148. doi: 10.4049/immunohorizons.1900022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamb R.A., Zebedee S.L., Richardson C.D. Influenza virus M2 protein is an integral membrane protein expressed on the infected-cell surface. Cell. 1985;40:627–633. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Epstein S.L., Kong W.P., Misplon J.A., Lo C.Y., Tumpey T.M., Xu L., Nabel G.J. Protection against multiple influenza A subtypes by vaccination with highly conserved nucleoprotein. Vaccine. 2005;23:5404–5410. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prokudina E.N., Semenova N.P., Chumakov V.M., Rudneva I.A., Yamnikova S.S. Extracellular truncated influenza virus nucleoprotein. Virus Res. 2001;77:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(01)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Semenova N.P., Prokudina E.N. [Detection of influenza virus nucleoprotein on the surface of infected cells and in free nonvirion form] Mol. Gen. Mikrobiol. Virusol. 1991;(4):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Madeira F., Park Y.M., Lee J., Buso N., Gur T., Madhusoodanan N., Basutkar P., Tivey A.R.N., Potter S.C., Finn R.D., Lopez R. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W636–W641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz268. W1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Awasthi S., Hook L.M., Pardi N., Wang F., Myles A., Cancro M.P., Cohen G.H., Weissman D., Friedman H.M. Nucleoside-modified mRNA encoding HSV-2 glycoproteins C, D, and E prevents clinical and subclinical genital herpes. Sci. Immunol. 2019;4:eaaw7083. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw7083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bahl K., Senn J.J., Yuzhakov O., Bulychev A., Brito L.A., Hassett K.J., Laska M.E., Smith M., Almarsson Ö., Thompson J. Preclinical and clinical demonstration of immunogenicity by mRNA vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 influenza viruses. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:1316–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pardi N., Hogan M.J., Pelc R.S., Muramatsu H., Andersen H., DeMaso C.R., Dowd K.A., Sutherland L.L., Scearce R.M., Parks R. Zika virus protection by a single low-dose nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccination. Nature. 2017;543:248–251. doi: 10.1038/nature21428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richner J.M., Himansu S., Dowd K.A., Butler S.L., Salazar V., Fox J.M., Julander J.G., Tang W.W., Shresta S., Pierson T.C. Modified mRNA vaccines protect against Zika virus infection. Cell. 2017;169:176. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.John S., Yuzhakov O., Woods A., Deterling J., Hassett K., Shaw C.A., Ciaramella G. Multi-antigenic human cytomegalovirus mRNA vaccines that elicit potent humoral and cell-mediated immunity. Vaccine. 2018;36:1689–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meyer M., Huang E., Yuzhakov O., Ramanathan P., Ciaramella G., Bukreyev A. Modified mRNA-based vaccines elicit robust immune responses and protect guinea pigs from Ebola virus disease. J. Infect. Dis. 2018;217:451–455. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pardi N., Parkhouse K., Kirkpatrick E., McMahon M., Zost S.J., Mui B.L., Tam Y.K., Karikó K., Barbosa C.J., Madden T.D. Nucleoside-modified mRNA immunization elicits influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3361. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05482-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lindgren G., Ols S., Liang F., Thompson E.A., Lin A., Hellgren F., Bahl K., John S., Yuzhakov O., Hassett K.J. Induction of robust B cell responses after influenza mRNA vaccination is accompanied by circulating hemagglutinin-specific ICOS+ PD-1+ CXCR3+ T follicular helper cells. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1539. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lutz J., Lazzaro S., Habbeddine M., Schmidt K.E., Baumhof P., Mui B.L., Tam Y.K., Madden T.D., Hope M.J., Heidenreich R., Fotin-Mleczek M. Unmodified mRNA in LNPs constitutes a competitive technology for prophylactic vaccines. NPJ Vaccines. 2017;2:29. doi: 10.1038/s41541-017-0032-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feldman R.A., Fuhr R., Smolenov I., Mick Ribeiro A., Panther L., Watson M., Senn J.J., Smith M., Almarsson Ӧ., Pujar H.S. mRNA vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 influenza viruses of pandemic potential are immunogenic and well tolerated in healthy adults in phase 1 randomized clinical trials. Vaccine. 2019;37:3326–3334. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eggink D., Goff P.H., Palese P. Guiding the immune response against influenza virus hemagglutinin toward the conserved stalk domain by hyperglycosylation of the globular head domain. J. Virol. 2014;88:699–704. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02608-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brazzoli M., Magini D., Bonci A., Buccato S., Giovani C., Kratzer R., Zurli V., Mangiavacchi S., Casini D., Brito L.M. Induction of Broad-Based Immunity And Protective Efficacy By Self-Amplifying mRNA vaccines encoding influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 2015;90:332–344. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01786-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Magini D., Giovani C., Mangiavacchi S., Maccari S., Cecchi R., Ulmer J.B., De Gregorio E., Geall A.J., Brazzoli M., Bertholet S. Self-amplifying mRNA vaccines expressing multiple conserved influenza antigens confer protection against homologous and heterosubtypic viral challenge. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0161193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]