Abstract

Intracellular pathogens commonly manipulate the host lysosomal system for their survival. However, whether this pathogen-induced alteration affects the organization and functioning of the lysosomal system itself is not known. Here, using in vitro and in vivo infections and quantitative image analysis, we show that the lysosomal content and activity are globally elevated in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)-infected macrophages. We observed that this enhanced lysosomal state is sustained over time and defines an adaptive homeostasis in the infected macrophage. Lysosomal alterations are caused by mycobacterial surface components, notably the cell wall-associated lipid sulfolipid-1 (SL-1), which functions through the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1)–transcription factor EB (TFEB) axis in the host cells. An Mtb mutant lacking SL-1, MtbΔpks2, shows attenuated lysosomal rewiring compared with the WT Mtb in both in vitro and in vivo infections. Exposing macrophages to purified SL-1 enhanced the trafficking of phagocytic cargo to lysosomes. Correspondingly, MtbΔpks2 exhibited a further reduction in lysosomal delivery compared with the WT. Reduced trafficking of this mutant Mtb strain to lysosomes correlated with enhanced intracellular bacterial survival. Our results reveal that global alteration of the host lysosomal system is a defining feature of Mtb-infected macrophages and suggest that this altered lysosomal state protects host cell integrity and contributes to the containment of the pathogen.

Keywords: tuberculosis, lysosomes, homeostasis, sulfolipid-1 (SL-1), host-pathogen interaction, adaptive lysosomal homeostasis, cell wall lipid, macrophage, innate immunity, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, pathogenesis, phagocytosis, mTOR complex (mTORC), mycobacteria

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is considered as one of the most successful infectious agents known to mankind. A large part of this success is due to the ability of the bacteria to manipulate and interfere with the host system at multiple levels. At a cellular level, to establish and sustain the infected state, M. tuberculosis significantly interferes with the host cell trafficking pathways, such as phagosome maturation (1–4) and autophagy (5, 6). In cultured macrophages in vitro, M. tuberculosis prevents the fusion of phagosomes to lysosomes, instead residing in a modified phagosome (1, 4). During in vivo infections, mycobacteria are delivered to lysosomes (7, 8) after an initial period of avoiding it (7). Despite encountering acidic conditions in lysosomes in vivo, mycobacteria continue to survive (7, 8), showing that additional acid tolerance mechanism are involved (8, 9). Encounter with the host cell lysosomal pathway, in both avoiding it and adapting to it, is critical for the intracellular life of mycobacteria.

Despite the bacteria itself residing in an arrested phagosome in vitro, M. tuberculosis infection could impact the endo-lysosomal system globally, because mycobacterial surface components, including distinct lipids, accumulate in late endosomes and lysosomes (10–13). In fact, individual mycobacterial lipids modulate vesicular trafficking in the host cells. For example, phosphatidylinositol mannoside (PIM) specifically increases the homotypic fusion of endosomes and also endosome-phagosome fusion (14), lipoarabinomannan (LAM) inhibits the trafficking of hydrolases from the trans-Golgi network (TGN) to late phagosome-lysosome and also inhibits the fusion of late endosomes to late phagosomes (15), Trehalose dimycolate decreases late endosome-lysosome fusion and lysosomal Ca2+ release (16). These interactions suggest significant interferences with the endo-lysosomal network during M. tuberculosis infection. Indeed, increased lysosomal content is reported in M. tuberculosis-infected mouse tissues in vivo (7). However, only a few studies have systematically addressed such global alterations. Podinovskaia et al. (17) showed that the trafficking of an independent phagocytic cargo is significantly altered in M. tuberculosis-infected cells, arguing that M. tuberculosis infection globally affects phagocytosis.

Phagosome maturation from a nascent phagosome to phagolysosome requires sequential fusion with early endosomes, late endosomes, and lysosomes (18–20), hence optimal endosomal trafficking is necessary for phagosomal maturation. Consequently, pharmacological activation of endosomal trafficking overcomes mycobacteria-mediated phagosome maturation arrest, and negatively impacts intracellular mycobacterial survival (7). Similarly, pharmacological and physiological modulation of autophagy results in delivering mycobacteria to lysosomes (5, 21–23) and increasing the total cellular lysosomal content (23). Mycobacterial survival within macrophages could thus be sensitive to alterations in the host endo-lysosomal system.

Phagocytosis and lysosomes are coupled by signaling pathways, where phagocytosis enhances lysosomal bactericidal properties (24) and concomitant lysosomal degradation is important for sustained phagocytosis at the plasma membrane (25). Emerging evidence support a model of lysosomal remodeling and adaptation during phagocyte activation (26). Hence lysosomal homeostasis plays a crucial role during infections. The traditional view of lysosomes as the “garbage bin” of the cell is undergoing dramatic revisions in recent years, with lysosomes emerging as a signaling hub integrating diverse environmental, nutritional, and metabolic cues to alter cellular response (27, 28). Importantly, lysosomal biogenesis itself is one such major downstream response, which is orchestrated by transcription factors of the microphthalmia family, notably TFEB (29–32). Whether or not M. tuberculosis or its components impacts these processes is not known.

In this study, we focus on the global alterations in the macrophage lysosomal system and show that it is significantly increased in M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages compared with noninfected cells. This increase is robust and defines an altered homeostatic state in the infected cells. Modulations in the lysosomal system are mediated by diverse mycobacterial surface components, such as the sulfolipid (SL-1) and PIM6. Purified SL-1 induces lysosomal biogenesis in an mTORC1-TFEB–dependent manner, whereas an M. tuberculosis mutant strain lacking SL-1 shows correspondingly reduced alteration in the lysosomal homeostasis both in vitro and in vivo. The attenuated lysosomal rewiring in the SL-1 mutant results in reduced trafficking to lysosomes and an enhanced intracellular survival of the mutant bacteria.

Results

M. tuberculosis infected macrophages have elevated lysosomal content and activity than uninfected bystander cells

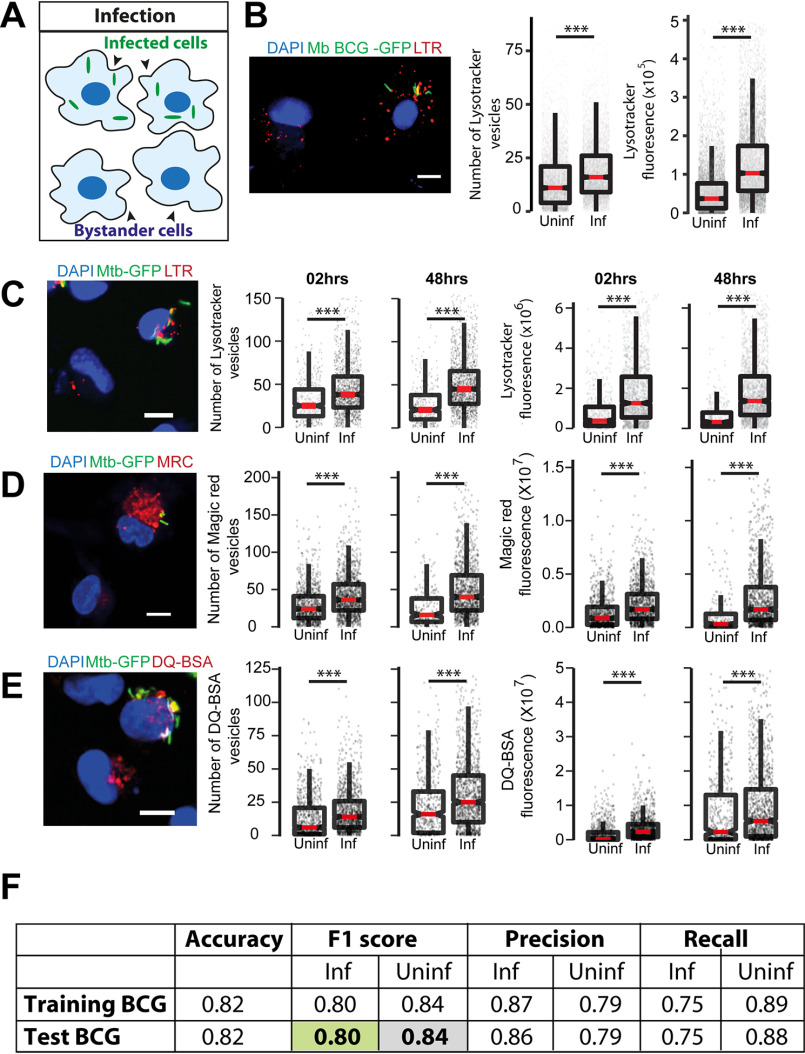

To assess if there are global changes in total lysosomal content during mycobacterial infections, we infected human primary monocyte-derived macrophages with Mycobacterium bovis BCG, stained with acidic probe LysoTracker Red, fixed the cells 48 h post-infection and imaged. Individual cells were segmented based on the cytoplasmic dye CellMask Blue, whereas bacteria and LysoTracker vesicles were segmented based on their GFP and LysoTracker Red fluorescence intensities, respectively (7, 23, 33) (Fig. S1A). From the segmented images multiple features relating to the number, intensity, and morphology of bacteria and lysosomes were extracted. Typically, 50–60% of cells were infected under these experimental conditions; hence, statistics could be obtained from a reliably large number of both infected and uninfected cells from the same population at a single cell resolution (Fig. 1A). First, we compared the total number and total intensity of lysosomes per cell between individual infected and uninfected cells (bystander cells) from the same population. The results show that infected cells on an average have more LysoTracker-positive vesicles than uninfected cells (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

M. tuberculosis infected macrophages have higher lysosomal content and activity (in vitro). A, schematic showing the experimental design to differentiate between infected and uninfected (bystander) cells in the same population. B, primary human macrophages infected with GFP expressing M. bovis BCG were pulsed with LysoTracker Red at 48 hpi. The number of LysoTracker vesicles and integrated LysoTracker fluorescence intensity were compared between infected and bystander-uninfected cells. C–E, THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages were infected with M. tuberculosis-GFP H37Rv and pulsed with LysoTracker Red (C), MRC (D), or DQ-BSA (E) 2 and 48 hpi and imaged. Graphs show the number and total cellular intensities of the corresponding vesicles at the indicated time points. Results are representative of at least three biological experiments. Statistical significance was assessed using Mann-Whitney test, *** denotes p value less than 0.001. Scale bar is 10 μm. For B–E, data are represented as box plots, with median value highlighted by a red line. Individual data points corresponding to single cells are overlaid on the boxplots. F, multiparametric data from different infection experiments were used to train a classifier to predict infected cells based on the lysosomal features, as described under “Experimental procedures.” The test was done in the absence of information on the bacteria channel. The close match in the F1 score between training and test datasets indicates accurate prediction. Approximately 15,000 cells were used for the M. bovis BCG training data set, and 6500 for the test.

In the assay described above, we have used LysoTracker Red, a fluorescent dye commonly used as a lysosomal reporter, which is, however, not specific to lysosomes as it labels all acidic vesicles in the cell. To confirm if the alterations observed are specific to lysosomes, we immunostained M. bovis BCG-infected THP-1 macrophages with antibodies against commonly used lysosomal markers, Lamp1, Lamp2, and assessed the lysosomal content by imaging (Fig. S1, B–D) as well as flow cytometry (Fig. S1E) assays. In both cases, infected cells showed higher lysosomal content than uninfected cells. Moreover, the elevated lysosomal content in M. bovis BCG-GFP–infected cells was observed as early as 2 h post-infection and sustained over time (Fig. S1, C–E).

Next, we tested if similar lysosomal alterations are observed during pathogenic M. tuberculosis infection. We infected THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages with M. tuberculosis H37Rv expressing GFP and stained with LysoTracker Red and analyzed the LysoTracker Red content at 2 and 48 h post-infection. The results (Fig. 1C) show increased LysoTracker Red content in M. tuberculosis H37Rv-infected cells, showing that the lysosomal alterations are not limited to M. bovis BCG-GFP infections. We sought to further functionally characterize the lysosomal alterations during Mtb infection. Hence, we repeated these experiments with two lysosome activity probes, Magic Red cathepsin (MRC) and DQ-BSA, which are cell-permeable fluorogenic substrates of lysosomal proteases that fluoresce when exposed to the hydrolytic lysosomal proteases. The results (Fig. 1, D and E) show that the number and total fluorescence of both MRC and DQ-BSA–positive vesicles are higher in M. tuberculosis H37Rv-infected cells compared with noninfected cells, showing that the lysosomes in infected cells are functional in terms of their proteolytic activity. Together, these results from different macrophage and mycobacterial infections were assessed using a variety of lysosomal probes show that Mtb infection alters the lysosomal system of macrophages.

Our high content analysis extracted several parameters related to lysosomes, such as the intensity, size, elongation, and distribution at a single cell resolution. We tested if analysis of all the parameters from a large number of infected and uninfected cells can provide further evidence of lysosomal alterations in infected cells. We used two separate datasets of human primary monocyte-derived macrophages infected with M. bovis BCG-GFP (Exp1 and Exp2). Dataset Exp1 contained 37,923 cells of which 18,546 were infected, whereas dataset Exp2 contained 36,476 cells of which 15,022 were infected. The data were split into training and test sets, and a model was trained using logistic regression, as described under “Experimental procedures.” The results showed that the model can indeed identify infected cells with ∼90% accuracy (Fig. 1F). Accuracy measures the fraction of true predictions made by the model. For the Exp1 dataset, accuracy varied from 0.717 to 0.821 for the test set as we increased the number of features used for classification. To identify the individual lysosomal features contributing maximally for accurate identification of infected cells, we iterate over different sets of parameters. This analysis revealed that a subset of seven features showed the highest contribution, with an accuracy of 0.800, showing that maximum information is captured by this subset of features. Similarly, for the Exp2 dataset, the accuracy values vary between 0.770 and 0.849, with an accuracy of 0.841 for a subset of six features. Single feature analysis showed that the top 11 features selected by both datasets are identical, showing that the features selected are data independent. Furthermore, analyses using an independent algorithm (random forest) reiterated the importance of these features as they are once again ranked in the top 11 and contribute >70% during classification. We obtained similar results in another data set describing THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages infected with M. bovis BCG-GFP. Thus, lysosomal features alone can predict the infection status of a cell. The accurate prediction of an infected cell solely based on the lysosomal parameters in the absence of any information from the bacterial channel, and the remarkable consistency across different experimental data sets shows the robustness of the alterations in lysosomes upon mycobacterial infection.

Lysosomal alterations in vivo

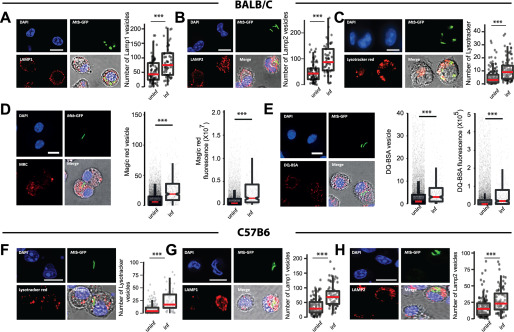

Next, we tested if similar lysosomal rewiring is observed during in vivo infection. We infected BALB/c mice with M. tuberculosis H37Rv expressing GFP using aerosol infection. After 4 weeks, we prepared single cell suspensions from infected lungs and isolated macrophages. The identity of these cells was tested using F4/80 and CD11b, two markers frequently used to characterize murine macrophages (34), and were found to be over 90% positive (Fig. S2, A–D). We stained these cells with LysoTracker Red, or immunostained for antibodies against Lamp1 and Lamp2 followed by the assessment of the total lysosomal content between infected and uninfected cells. The results, compiled from 4 individual mice (Fig. 2, A–C), show increased lysosomes specifically in infected cells. Similarly, macrophages from infected mice pulsed with functional lysosomal probes MRC and DQ-BSA showed a higher number and total cellular fluorescence of lysosomes in infected cells compared with noninfected (Fig. 2, D and E). Similar results were obtained in macrophages isolated from C57BL/6J mice infected with Mtb-GFP H37Rv and lysosomes stained using LysoTracker Red or Lamp1 or Lamp2 antibodies (Fig. 2, F–H), showing that these alterations are strain independent.

Figure 2.

M. tuberculosis infected macrophages have higher lysosomal content and activity (in vivo). A–C, BALB/c mice were infected with ∼5000 cfu of M. tuberculosis-GFP H37Rv by aerosol inhalation. 4 weeks post-infection, macrophages were isolated from infected lungs and immunostained with Lamp1 (A), Lamp2 (B), or stained with LysoTracker Red (C) and the number of lysosomes were compared between infected and uninfected cells. Data are pooled from four mice. D and E, BALB/c mice were infected with ∼500 cfu of M. tuberculosis-GFP H37Rv by aerosol inhalation. Macrophages were isolated from 6-weeks post-infection infected lungs and stained with Magic Red cathepsin (D) or DQ-BSA (E) and the lysosome number and integral intensity were compared between infected and uninfected cells. Data are pooled from three mice. Results are representative of three independent infections. F–H, C57BL/6J mice were infected with ∼5000 cfu of M. tuberculosis-GFP H37Rv by aerosol inhalation and 4 weeks post-infection macrophages were isolated from infected lungs. Panels F–H show representative images from LysoTracker Red, Lamp1, and Lamp2 staining, respectively, of these macrophages. Data are pooled from three mice. Results are representative of two independent infections with at least three mice each. For all experiments, statistical significance was assessed using Mann-Whitney test, and *** denotes p value less than 0.001. Scale bar is 10 μm. Data are represented as box plots, with median value highlighted by a red line. Individual data points corresponding to single cells are overlaid on the box plots.

Although these results suggest that lysosomes are rewired in vivo during Mtb infection, there are two potential confounding factors for this interpretation. First, the time point used for these infections (4 or 6 weeks) could result in immune activation, which could influence our results. Second, we used high aerosol inocula of 5,000 cfu in these assays. Although both the high inocula and longer infection time were necessary to obtain a sufficient number of infected cells from mice for statistical analysis, they could cause artifacts. To test if these factors are significantly influencing the results, we first infected THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages with Mtb-GFP CDC1551 and treated with 25 ng/ml of Interferon-γ for 48 hpi followed by staining with LysoTracker Red. Quantification of total cellular LysoTracker content reveals that, although as expected, there is an increase in net lysosomal content upon Interferon-γ treatment, Mtb CDC1551-infected cells showed a further increase (Fig. S2, E and F). These results suggest that the lysosomal rewiring during Mtb infection is autonomous of immune activation status. Next, we infected BALB/c mice with low aerosol inocula (∼150 cfu) of Mtb-GFP H37Rv for a shorter time point. We isolated infected macrophages from mice ∼2 weeks post-infection and stained with LysoTracker Red or MRC. Data pooled from multiple infected mice show (Fig. S2, G and H) similar alterations in lysosomes in vivo even at low cfu infection and shorter infection time point. Thus, the rewiring of host lysosomes observed in vitro is also conserved during in vivo infections and is consistent across different M. tuberculosis strains.

Lysosomal profiles of macrophages infected with mycobacteria and Escherichia coli are distinct from each other

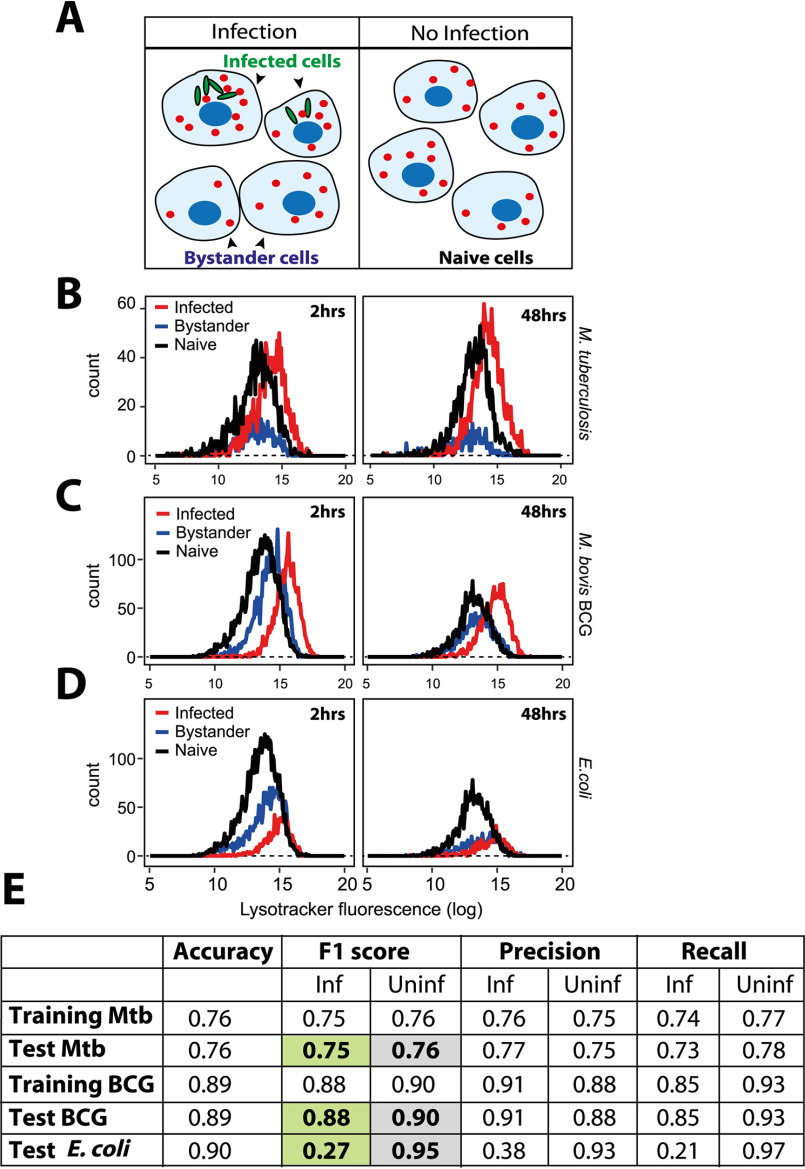

In the assays described above, we have compared lysosomal content and activity from infected and uninfected cells from the same population. Uninfected cells in the same milieu as infected cells are subjected to bystander effects (11, 13) and may not be true representatives of a nonperturbed macrophage. Hence, we next compared the lysosomal content of infected and bystander cells with naive macrophages. The definitions of the three cell populations are illustrated in Fig. 3A. Distributions give a more complete picture of the heterogeneity in a population than methods that emphasize on central tendencies. Hence, we compared the distribution of lysosomal content of the three different cell populations, i.e. Mtb-GFP H37Rv infected, bystander, and naive macrophages using LysoTracker Red, as well as lysosomal activity probes, DQ-BSA and MRC labeling. The results (Fig. 3B, Fig. S3, A and B) show that naive macrophages have a broad spread of distribution of integral intensity in all the three lysosomal probes tested, indicating substantial heterogeneity within the macrophage population. The distribution of bystander cells was contained within the naive cell distribution. However, the bounds of the distribution of the infected cells extended beyond the upper limits of the naive cells, showing that the alterations in lysosomes are specific for infected cells. This pattern was similar at 2 and 48 hpi, indicating the sustained nature of lysosomal alteration in infected macrophages (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained in THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages infected with M. bovis BCG (Fig. 3C) and stained with LysoTracker Red.

Figure 3.

M. tuberculosis infected macrophages show distinct lysosomal modulation compared with E. coli-infected macrophages. A, schematic showing the experimental design to differentiate between bystander-uninfected and naive cells. Two different wells from a multiwell plate are shown; one is infected with GFP expressing mycobacteria, where infected and bystander (uninfected) cells are present. Bacteria are not added to the second well, hence the cells are naive. Lysosomes are illustrated in red. B, THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages were infected with M. tuberculosis-GFP H37Rv and stained for LysoTracker Red at 2 and 48 hpi. Cells were fixed and imaged. Histograms compare the distribution of LysoTracker intensities between M. tuberculosis-GFP infected, bystander and naive macrophages at 2 and 48 hpi. Results are representative of at least three biological experiments. C and D, THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages were infected with either M. bovis BCG (C) or E. coli (D) and pulsed with LysoTracker Red at 2 and 48 hpi. Integrated LysoTracker intensity was measured between infected and bystander cells (red and blue lines) and compared with the distribution of naive macrophages (black). More than 800 cells were analyzed of each condition for distributions. Results are representative of at least two biological experiments. E, multiple lysosomal features from THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages infected with Mtb-GFP H37Rv or M. bovis BCG-GFP were used as a training data set to classify an infected cell solely based on lysosomal parameters (in the absence of any information on the bacteria), as described under “Experimental procedures.” Test Mtb, BCG, or E. coli shows the accuracy of the prediction, as assessed by the F1 score, precision, and recall values. Uninfected cells from Mtb, M. bovis BCG-GFP, or E. coli-infected macrophage populations were indistinguishable from each other in terms of the lysosomal properties; however, the respective infected cells were very different. Over 7000 and 10,000 cells were used for training and test data set, respectively, for M. bovis BCG-GFP and E. coli infections, whereas the corresponding numbers for Mtb-GFP H37Rv infections were 1,300 and 600 cells.

Next, we assessed if the alterations observed on lysosomes are specific to mycobacterial infections, because emerging literature suggests a role for lysosomal expansion during phagocyte activation, including E. coli infection (24). Toward this, we compared the lysosomal distributions with a similar experiment in E. coli-infected macrophages. The result (Fig. 3D) shows that the distribution of lysosomal integral intensity of E. coli-infected macrophages, despite a relative increase compared with bystander cells immediately after infection, remained within the bounds of naive macrophages (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the lysosomal response observed during Mtb infections is distinct. Similarly, a scatter plot analysis of bacterial and LysoTracker integral intensities from the same cell shows a high correlation between the two parameters from M. bovis BCG-infected, but not E. coli-infected, cells (Fig. S3C). Additionally, the classifier previously trained to predict the infection status of a cell solely based on its lysosomal features in human primary macrophages also successfully predicted infected cells in case of both Mtb H37Rv and M. bovis BCG infections in THP-1 cells, but failed to predict E. coli-infected cells (Fig. 3E). Together, these results suggest that alteration in lysosomal homeostasis is distinct in Mtb-infected cells, and imply that mycobacteria-specific factor(s) cause the alterations in host lysosomes during M. tuberculosis infection.

Mycobacterial components modulating the lysosomal pathway

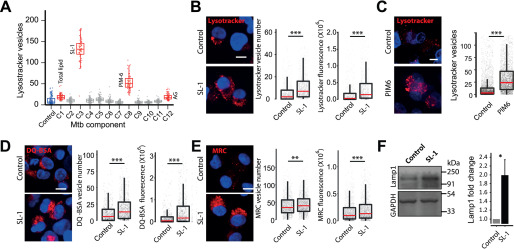

We hypothesized that the factor(s) modulating lysosomal homeostasis could be of mycobacterial origin. We reasoned that the mycobacterial surface components could play a role in the adaptive lysosomal homeostasis, because Mtb surface lipids access the host endo-lysosomal pathway and are known to be involved in virulence and modulation of host responses (12, 14, 15). Hence, we screened different M. tuberculosis surface components for their effect on host lysosomes. The addition of total M. tuberculosis H37Rv lipids to THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages resulted in a significant increase in the cellular lysosomes, as assessed by LysoTracker Red staining (Fig. 4A, component C1). Some of the purified individual M. tuberculosis H37Rv surface components added at identical concentration resulted in elevated lysosomal levels (Fig. 4A). Two of the lipids, SL-1 and PIM6, showed a strong response, we validated them in independent assays at lower doses (Fig. 4, B and C). Because SL-1 showed the strongest response, we chose this for further detailed analysis. We further validated the SL-1–mediated lysosomal expansion by adding increasing amounts of SL-1 to THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages, which resulted in increasing levels of Lysotracker Red fluorescence (Fig. S4A). Next, we checked if the increase is specific for LysoTracker Red staining, or if the lysosomal activity is increased as well. Hence, we pulsed SL-1 treated THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages with lysosomal activity probes DQ-BSA and MRC (Fig. 4, D and E) and obtained similar results, showing that total cellular lysosomal content and activity increases upon SL-1 treatment. The increase in lysosomal content upon SL-1 treatment was further confirmed by immunoblotting lysates of SL-1–treated THP1 cells for lysosomal marker Lamp1 (Fig. 4F). Importantly, RAW macrophages as well as nonmacrophage cells like HeLa cells treated with SL-1 showed similar phenotypes (Fig. S4, B and C), showing that the increased lysosomal phenotype mediated by SL-1 is not cell type-specific and suggesting that SL-1 could influence a molecular pathway broadly conserved in different cell types. Finally, we assessed if the SL-1 effect is specific for lysosomes or if it influences the upstream endocytic pathway. Toward this, we pulsed SL-1 treated cells with two different endocytic cargo, namely fluorescently tagged transferrin or dextran. The results (Fig. S4, D and E) show that SL-1 does not affect endocytic uptake, suggesting that its effect is modulating lysosomes specifically.

Figure 4.

Mycobacterial surface lipids, predominantly SL-1, mediate alterations in host cell lysosomes. A, THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages were treated with different purified M. tuberculosis H37Rv surface components at 50 μg/ml concentration and screened for their effect on macrophage lysosomal content. DMSO is used as vehicle control. The M. tuberculosis H37Rv surface components used are C1 (total lipid), C2 (mycolic acid), C3 (sulfolipid-1), C4 (trehalose dimycolate), C5 (mycolylarabinogalactan-peptidoglycan), C6 (lipomannan), C7 (phosphatidylinositol mannosides 1 and 2), C8 (phosphatidylinositol mannosides 6), C9 (lipoarabidomannan), C10 (mycobactin), C11 (trehalose monomycolate), and C12 (arabinogalactan). Each data point in the graph represents one image. The results are representative of two independent screens. B and C, THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages were treated with 20 μg/ml of purified Mtb H37Rv SL-1 (B) or PIM6 (C) for 24 h and stained with LysoTracker Red. Representative images show staining of LysoTracker Red in vehicle and SL-1/PIM6–treated THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages. D and E, THP1 monocyte-derived macrophages were treated with 20 μg/ml of purified SL-1 for 24 h and stained with lysosomal activity probes DQ-BSA (D) or MRC (E). Representative images show the staining and quantification of lysosomal number and integral intensity in respective stain in control and SL-1–treated macrophages. Statistical significance for A–E was assessed using Mann-Whitney test, ** denotes p value of less than 0.01 and *** denotes p value of less than 0.001. Scale bar is 10 μm. For B–G, data are represented as box plots, with the median denoted by red line. Individual data points corresponding to single cells are overlaid on the box plot. F, Lamp1 protein levels in SL-1–treated THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophage lysates assessed by immunoblotting for the Lamp1 antibody. GAPDH used as a loading control. The graph shows the average and S.E. of band intensity normalized to GAPDH from at least three experiments. Significance is assessed using unpaired-one tailed Student's t test with unequal variance, * represents p value less than 0.05.

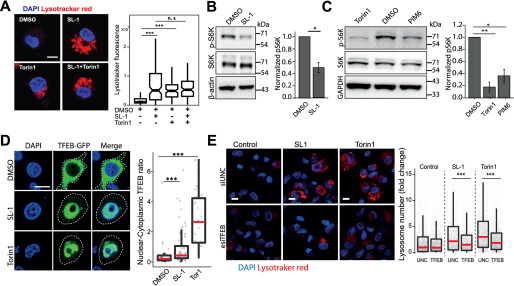

Next, we aimed to gain insights into the molecular mechanism by which SL-1 influences lysosome biogenesis. The role of the mTORC1 complex in lysosomal biogenesis is well known (35). We reasoned that if mTORC1 is involved in the SL-1–mediated lysosomal increase, it should not have an additive effect on the lysosomal increase when combined with Torin1, a well-known mTORC1 inhibitor (36). Hence, we co-treated cells with Torin1 and SL-1 and tested for any additive effect on lysosomal biogenesis. The result (Fig. 5A) showed that whereas Torin1 and SL-1 increased lysosomal content in the cells individually, they did not show an additive effect when added together (Fig. 5A), suggesting that SL-1 acts through mTORC1. To check if SL-1 influences mTORC1 activity, we immunoblotted lysates from control and SL-1–treated cells with antibodies specific against phosphorylated forms of the mTORC1 substrate, S6 kinase. The results show a significant decrease in S6K phosphorylation, showing that SL-1 inhibits mTORC1 activity (Fig. 5B). Similar results were obtained with a different lysosome modulating Mtb lipid, PIM6 (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

SL-1 from M. tuberculosis influences lysosomal biogenesis in host cells via mTORC1-dependent nuclear translocation of the TFEB. A, THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages were treated with DMSO/SL1/Torin1/SL1+Torin1 comparing LysoTracker staining levels between the different conditions. Representative images and quantification of cells treated with 25 μg/ml of SL-1 and 1 μm Torin1. Approximately 100 cells were analyzed per category in each experiment and significance was assessed by Mann-Whitney test. The data presented are representative of two independent experiments. B and C, immunoblots and quantification of phosphorylated and total levels of indicated proteins in THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophage lysates treated with DMSO (control) or SL-1 (B) or PIM6 (C). Torin1 (1 μm) was used as a positive control. Bar graphs show average of at least three biological replicates and error bars represent S.D. Change in the phosphorylation status of the indicated protein (S6 kinase, Thr-389) was assessed by normalizing phosphorylated protein to the respective total protein. Actin/GAPDH was used as the loading control. Significance is assessed using unpaired one-tailed Student's t test with unequal variance, * represents p value less than 0.05 and ** less than 0.01. D, RAW macrophages were transfected with TFEB-GFP for 24 h and treated with 25 μg/ml of SL-1 or negative and positive controls, DMSO and Torin1 (250 nm for 24 h), respectively. Representative images and quantification of nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio of TFEB-GFP between the different conditions are shown. Results are representative of at least three independent experiments. E, THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages were transfected with either control siRNA (Universal negative control 1, UNC1) or TFEB siRNA for 48 h followed by treatment with SL-1 (25 μg/ml for 24 h) or Torin1 (1 μm for 4 h) and were pulsed with LysoTracker Red and imaged. Representative images and quantification of control, SL-1, and Torin1 treatment in UNC1 or TFEB siRNA-transfected macrophages are shown. Results are representative of two biological experiments. Statistical significance for A, D, and E was assessed using Mann-Whitney test, *** denotes p value of less than 0.001 and n.s. represents nonsignificant. Scale bar is 10 μm. For A, D, and E, data are represented as box plot. Individual data points overlaid on the box plot in D and E represent single cells.

mTORC1 inhibition releases the transcription factor TFEB from lysosomes, which translocates to the nucleus and binds to the genes containing CLEAR motif, to drive the transcription of lysosomal genes (29, 37). Hence, we checked if SL-1–mediated inhibition of mTORC1 results in nuclear translocation of TFEB. Toward this, we transfected HeLa as well as RAW cells with TFEB-GFP (38) and treated with SL-1. Torin1 was used as positive control in these assays. The results (Fig. 5D, Fig. S5A) show a significant nuclear translocation of TFEB upon SL-1 treatment. Finally, to confirm the involvement of TFEB in the SL-1–mediated increase in lysosomes, we silenced TFEB expression in THP-1 macrophages with esiRNA for TFEB. Silencing was confirmed by Western blotting for TFEB (Fig. S5B). We treated TFEB and universal negative control-silenced cells with SL-1, and quantified the change in the lysosomal number between the different conditions (Fig. 5E). The result shows a significant reduction in the number of lysosomes in TFEB-silenced cells treated with SL-1. Similar results were obtained with the positive control Torin1 (Fig. 5E). Together, these assays identify Mtb SL-1 as a key lipid mediator of lysosomal biogenesis, which is acting through the mTORC1-TFEB pathway. A previous study by Blanc et al. (39) showed SL-1 as a competitive antagonist of TLR2, thus providing a link with the innate immune pathway. To check if TLR2 is involved in the lysosomal expansion phenotype mediated by SL-1, we treated WT and TLR2-deficient macrophages with SL-1 and assessed the lysosomal content by LysoTracker staining and imaging. Our results show that TLR2 deficiency does not rescue the SL-1–induced lysosomal expansion (Fig. S5, C and D), suggesting that TLR2 is not involved in the lysosomal phenotype mediated by SL-1.

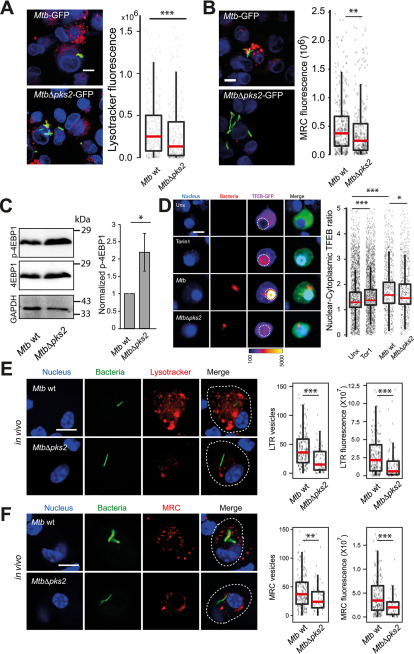

In the assays described above, we have treated macrophages with purified lipids. The presentation of the lipids to the host cells, and consequently its response, can be different when added externally in a purified format, or presented in the context of the Mtb bacteria. To address this question, we tested an Mtb mutant lacking polyketide synthase 2 (pks2), a key enzyme involved in the SL-1 biosynthesis pathway (40). Infection of THP-1 macrophages with WT Mtb CDC1551 and MtbΔpks2 CDC1551 showed that the cells infected with the mutant Mtb elicited a weaker lysosomal response, as assessed by LysoTracker Red as well as the functional MRC probe staining (Fig. 6, A and B). Thus, SL-1 mediates lysosomal biogenesis in the context of Mtb infection. Similar results were obtained in RAW macrophages infected with the two Mtb strains (Fig. S6A). Furthermore, the external addition of SL-1 complemented the mutant phenotype, showing the specificity for SL-1 in the lysosomal expansion phenotype (Fig. S6A). We next tested the mTORC1-TFEB axis in modulating lysosomal biogenesis in the context of Mtb infection. Toward this, we probed lysates of THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages infected with either WT Mtb or MtbΔpks2 CDC1551with an antibody specific for phospho-4EBP1, a substrate of mTORC1. The results (Fig. 6C) shows a relative increase in p-4EBP1 signal in cells infected with MtbΔpks2 compared with WT Mtb-infected cells. We further confirmed the result using an independent assay of immunofluorescence with a different mTORC1 substrate, pS6K (Fig. S6, B and C), which showed a relative increase in pS6K intensity upon infection with the mutant Mtb. Together, these results suggest the involvement of SL-1 in mTORC1 modulation during Mtb infection. Next, we tested the nuclear translocation of TFEB upon Mtb infection by infecting RAW macrophages transfected with TFEB-GFP. The results show that similar to Torin1 treatment, WT Mtb infection results in nuclear translocation of TFEB (Fig. 6D). In this assay, Torin1 treatment was performed for 4 h, to have the same time scale as for the Mtb infection, hence the assay conditions are different from the earlier experiment involving Torin1 (Fig. 5D). Importantly, MtbΔpks2-infected cells show a partial rescue in the nuclear translocation of TFEB compared with WT-infected cells (Fig. 6D). Together, these results show that SL-1 modulates lysosomal biogenesis through the mTORC1-TFEB axis in the context of Mtb infection.

Figure 6.

M. tuberculosis SL-1 influences lysosomal biogenesis in both in vitro and in vivo infection via mTORC1-dependent nuclear translocation of the TFEB. A and B, THP1 monocyte-derived macrophages were infected with Mtb WT and MtbΔpks2 M. tuberculosis-GFP CDC1551 for 48 h and stained with different lysosome probes, namely LysoTracker Red (A) and MRC (B). Images and graphs in A and B show a comparison of the total lysosomal intensities of the respective probes in individual Mtb WT and MtbΔpks2 mutant-infected cells. C, THP1 monocyte-derived macrophages were infected with Mtb WT or MtbΔpks2 CDC1551 for 48 h and lysates were immunoblotted for mTORC1 substrate 4EBP1. Immunoblots and quantification of phosphorylated and total 4E-BP1 are shown. GAPDH is used as loading control. Results represent the average and S.E. of four biological experiments. D, RAW macrophages were transfected with TFEB-GFP followed by 4 h infection with Mtb WT or MtbΔpks2 CDC1551. Cells were fixed 4 hpi, imaged, and nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio of TFEB-GFP was compared between unexposed, Torin1 treated, WT, and pks2 mutant-infected cells. Torin1 treatment (250 nm for 4 h) was used as positive control. TFEB-GFP channel images are shown in Fire LUT for better visualization of the fluorescence intensities. Each data point represents the nuclear cytoplasmic ratio of TFEB intensity from an individual cell. Data points are pooled from two independent biological experiments. E and F, C57BL/6NJ mice were infected with Mtb WT or MtbΔpks2 CDC1551 by aerosol inhalation. Eight weeks post-infection, macrophages were isolated from infected lungs from single-cell suspension and were pulsed with LysoTracker Red (E) or MRC (F). The number and intensity of lysosomes in respective probes were compared between Mtb WT or MtbΔpks2 CDC1551-infected cells. Results are compiled from four WT Mtb and three Δpks2 CDC1551-infected mice and are representative of two independent infections. Statistical significance for A, B, and D–F was assessed using Mann-Whitney test, * denotes p value of less than 0.05, ** denotes p-value of less than 0.01 and *** denotes p value of less than 0.001. Scale bar is 10 μm. For A, B, and D–F, data are represented as box plots, with the median denoted by a red line. Individual data points corresponding to single cells are overlaid on the box plot.

Next, we assessed the role of SL-1 in modulating lysosomal response in vivo. We infected C57BL/6NJ mice with WT and MtbΔpks2 CDC1551 and assessed the lysosomal content in macrophages obtained from single-cell suspensions from infected lungs using LysoTracker Red and MRC staining. The results show decreased total lysosomal content in MtbΔpks2-infected cells compared with WT Mtb-infected cells (Fig. 6, E and F) demonstrating that indeed SL-1 is involved in lysosomal biogenesis also during in vivo infections. Despite this difference, both WT and MtbΔpks2 CDC1551-infected cells exhibited higher lysosomal content compared with their respective uninfected controls based on LysoTracker Red and MRC staining (Fig. S6, D and E), showing that the redundancy in the system is also conserved in vivo.

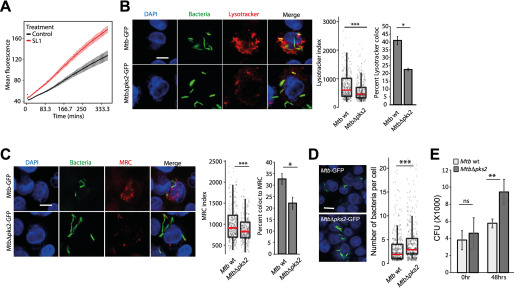

Our previous results (7) showed that mycobacterial infection alters the trafficking environment in hosts and influences the phagosome maturation of subsequent infections. We reasoned that the altered lysosomal environment mediated by SL-1 could affect phagosome trafficking kinetics. To test this, we pulsed SL-1 or vehicle-treated macrophages with pHrodo Red-labeled E. coli. Because the fluorescence of pHrodo inversely correlates with pH, the dye is a reliable indicator of phagosome maturation. The results (Fig. 7A) show a significant increase in the pHrodo intensity compared with control at all time points tested, showing that SL-1 indeed increases the acidification rate of E. coli phagosome. In cultured macrophages, it is well known that Mtb arrests the maturation of mycobacterial phagosome to lysosomes (1). Phagosome maturation arrest is a population effect, i.e. whereas a significant proportion of individual Mtb are in the arrested phagosome, a smaller fraction are indeed delivered to lysosomes. We reasoned that if SL-1 affects the kinetics of phagosome maturation, it could influence the proportion of Mtb delivered to the lysosomes. To test this, we infected macrophages with either WT or MtbΔpks2 bacteria and assessed their delivery to LysoTracker Red or MRC-positive vesicles. We assessed the co-localization using two different methods, as described earlier (7, 33) (Fig. S7). The results (Fig. 7, B and C) show that, in line with values reported in literature, the bulk of WT Mtb (∼60%) evade delivery to lysosomes. Interestingly, in the absence of SL-1, an even higher proportion of the mutant Mtb evade delivery to lysosomes, as seen with both LysoTracker Red and MRC labeling, showing that indeed the proportion of Mtb trafficked to lysosomes is altered.

Figure 7.

SL-1 alters phagosome maturation kinetics and survival of intracellular Mtb. A, RAW macrophages were infected with pHrodo Red-labeled E. coli and treated with SL-1. pHrodo Red fluorescence intensity was measured in a kinetic mode using a microplate reader. Mean ± S.D. from at least 4 wells for each condition is plotted. Results are representative of two biological replicates. The differences between control and SL-1 are statistically significant as assessed by unpaired one-tailed Student's t test with unequal variance. B and C, lysosomal delivery of WT and MtbΔpks2 CDC1551 following infection in THP1 monocyte-derived macrophages and lysosomal labeling with LysoTracker Red (B) or Magic Red cathepsin (C). Graphs show object-based colocalization of bacterial phagosomes with lysosomes stained with the respective lysosomal probes and quantified by two different methods as described under “Experimental procedures.” Bacteria overlapping by more than 50% with the lysosomal compartment were considered co-localized (shown in B and C, bar graphs). More than 1000 phagosomes were analyzed in each experiment for colocalization analysis. Results are average of three biological experiments and S.E. between the biological replicates. LysoTracker (B) and MRC (C) index represent the intensity of the respective lysosomal probe in the mycobacterial phagosome. D, bacterial counts from WT or MtbΔpks2-infected THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages 48 hpi. Cells and bacteria were segmented and counted as described under “Experimental procedures.” Each dot is a single infected cell, the median value of the data set indicated by red line and spread as indicated by the box plot. Results are representative of at least three independent biological replicates. E, CFUs of Mtb WT or MtbΔpks2 CDC1551-infected THP1 monocyte-derived macrophages immediately after infection and 48 hpi. Results are the average and S.E. of data compiled from three biological experiments, each containing four technical replicates. Scale bars are 10 μm, data are represented as box plots, with individual data points corresponding to single cells overlaid. Statistical significance for bar graphs in B, C, and E is assessed using unpaired-one tailed Student's t test with unequal variance, * represents p value less than 0.05, ** less than 0.01, and n.s. represents nonsignificant. Statistical significance for box plots in B–D was assessed using Mann-Whitney test, *** denotes p value of less than 0.001. Data are represented as box plots, with the median denoted by red line. Individual data points corresponding to single cells are overlaid on the box plot.

Mutant Mtb that fail to arrest phagosome maturation are typically compromised in their intracellular survival in cultured macrophages in vitro. In the case of MtbΔpks2, our results show a further decrease in lysosomal delivery from the WT. To check if this correlates with intracellular Mtb survival, we infected THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages with WT and MtbΔpks2 CDC1551 and assessed intracellular bacterial survival by imaging assays, as described earlier (23, 33). The results show that the number of bacteria per infected cell (Fig. 7D) is significantly higher in MtbΔpks2 compared with WT Mtb. Finally, to confirm this phenotype, we lysed infected cells and plated the cells on 7H11 agar medium immediately after infection, or at 48 hpi, and counted the number of colonies obtained. The results (Fig. 7E) show similar cfu immediately after infection, indicating that the uptake is not altered. Importantly, at 48 hpi, a significantly higher number of colonies were seen in mutant bacteria-infected cells (Fig. 7E) confirming the higher intracellular survival of MtbΔpks2 compared with WT Mtb CDC1551.

Discussion

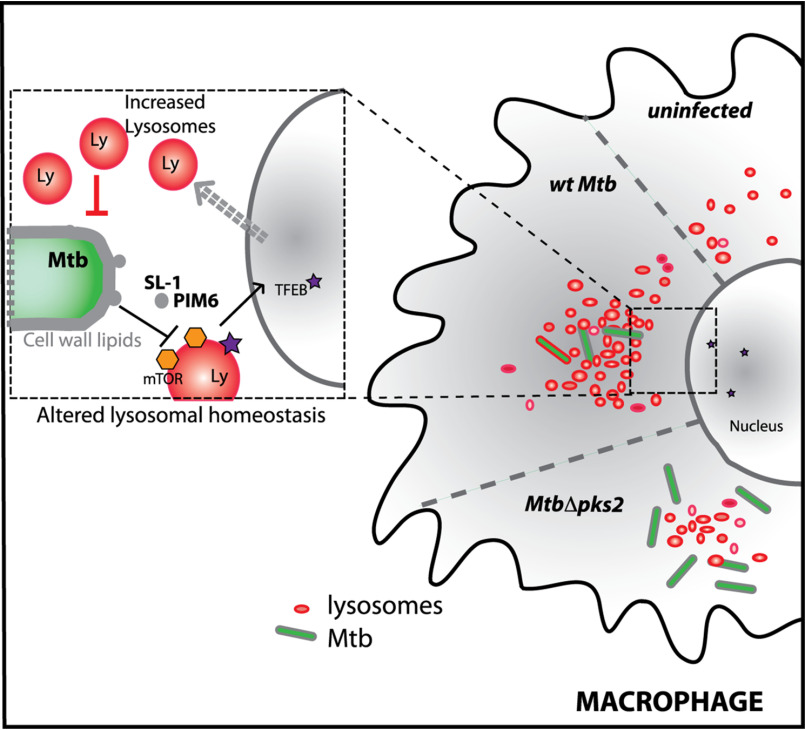

Here we report that M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages have a significantly elevated lysosomal system compared with noninfected cells. Strikingly, these alterations are sustained over time and conserved during in vivo infections, thus defining a rewired lysosomal state of an Mtb-infected macrophage. The alterations in lysosomes are mediated by mycobacterial surface components, predominantly SL-1. SL-1 alone induces lysosomal biogenesis in a cell type-independent manner by modulating the mTORC1-TFEB axis of the host cells and impacts the phagosome trafficking kinetics in macrophages. MtbΔpks2, a mutant that does not produce SL-1, shows attenuated lysosomal rewiring and a further reduction in bacterial delivery to lysosomes, correlating with increased intracellular Mtb survival (Fig. 8). Our results support a model of Mtb and lysosomes exerting reciprocal control on each other, where Mtb infection induces lysosomal biogenesis in macrophages, which in turn controls the trafficking and survival of the bacteria.

Figure 8.

Mtb infection induces lysosomal rewiring in macrophages. Mtb infection alters the cellular lysosomal homeostasis by inducing the biogenesis of lysosomes in infected cells. The lysosomal rewiring is mediated by Mtb surface lipids, predominantly sulfolipid (SL-1), which acts by modulating the mTORC1-TFEB axis. Mutant Mtb (MtbΔpks2) that does not produce SL-1 shows attenuated lysosomal rewiring, reduced lysosomal delivery and enhanced intracellular Mtb survival.

It is well established in in vitro infection models that M. tuberculosis blocks the maturation of its phagosome to lysosome, instead residing in a modified mycobacteria containing phagosome (1–4). Recent reports have shown that pathogenic mycobacteria are delivered to lysosomes in vivo, where they continue to survive, albeit at a reduced rate (7, 8). In the assay conditions reported in this work, both during in vitro and in vivo experiments, Mtb remained largely outside lysosomes, in line with an earlier observation that Mtb is delivered to lysosomes in vivo only after an initial period of avoiding lysosomal delivery (7). Therefore, in the context of this work, the majority of Mtb are within the arrested phagosome. The maturation of phagosome requires sequential fusion with endosomes, but what are the consequences of the presence of an arrested phagosome on the host endo-lysosomal pathway? Few studies have systematically explored such global alterations. Notably, Podinovskaia et al. (17) showed that in macrophages infected with M. tuberculosis, trafficking of an independent phagocytic cargo is altered, with changes in the proteolysis, lipolysis, and acidification rates, suggesting alterations in the host trafficking environment beyond the confines of the mycobacterial phagosome. Similarly, M. tuberculosis-infected tissues show strong alterations in the trafficking environment, which influences the trafficking of a subsequent infection (7). Thus, the environment of M. tuberculosis-infected cells and tissues are significantly different from a noninfected condition. Our results presented here show that the lysosomal system of Mtb-infected macrophages is globally altered. By combining data from different macrophage–mycobacteria infection systems, including strikingly primary infected macrophages from Mtb-infected mouse lungs, we show that this modulation is robust. In fact, the alterations in lysosomes are strong enough to accurately predict an infected cell only based on the lysosomal features, in the absence of any information from the bacteria. Therefore, the elevated lysosomal features are distinctive and indeed a defining aspect of M. tuberculosis-infected macrophage.

Our comparison of lysosomal features between mycobacteria and other infection conditions suggested that mycobacteria-specific factors modulate lysosomes. Mycobacterial components, including surface lipids and proteins, have been observed in infected cells outside of the mycobacterial phagosome, as well as in neighboring noninfected cells (11–13, 16, 41–49), where they can influence the antigen presenting capacity of macrophages or interfere with other macrophage functions (10). Specifically, individual mycobacterial lipids, including phosphatidylinositol mono- and di-mannosides (PIMs), phosphatidylglycerol, cardiolipin, phosphatidylethanolamine, and trehalose mono- and dimycolates are released into the macrophage and accumulate in late endosomes/lysosomes (10–13). In this study, we identify mycobacterial surface components that increase the macrophage lysosomes, even in the absence of infection, in a cell autonomous way.

Of the lipids tested, SL-1 showed a prominent effect on host lysosomes. Although considered nonessential for M. tuberculosis growth in culture, SL-1 is an abundant cell wall lipid, contributing up to 1–2% of the dry cell wall weight (50). SL-1 synthesis is controlled by multiple mechanisms and is up-regulated during infection of both human macrophages and in mice (51–55). Consequently, SL-1 has been proposed to play multiple roles in host physiology, including modulation of secretion of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, phagosome maturation arrest, antigen presentation, modulation of membrane dynamics, and host signaling (39, 56–60), and most recently, in inducing cough by activating nociceptive neurons (61). Here we show that SL-1 influences lysosomal biogenesis by inhibiting mTORC1 activity and consequently activating nuclear translocation of the transcription factor TFEB. Most of the studies attributing cellular roles for individual lipids employ purified lipids; but the abundance, distribution, and presentation of these lipids to the host cell from a mycobacterial cell envelope during infection scenario could be different. Our results with SL-1–deficient mutant, MtbΔpks2, shows that the mTORC1-TFEB pathway is correspondingly altered during bacterial infection, resulting in attenuated lysosomal rewiring in macrophages infected with the SL-1–deficient mutant bacteria, a phenotype that is strikingly recapitulated in primary infected cells from the mouse infection model. Thus SL-1 plays a critical role in adaptive lysosomal homeostasis in an infection context.

The mTOR complex is at the center of many signaling networks and plays a pivotal role in many host-pathogen interactions (62–66). Several reports have demonstrated that mTOR activity in the host cell is altered by viral (poliovirus, encephalomyocarditis virus, and poxviruses), protozoan (Toxoplasma and Leishmania), and bacterial (Shigella and Salmonella) pathogens (67–75). Some pathogens such as Leishmania, Shigella, Brugia malayi, poliovirus, and encephalomyocarditis virus have an inhibitory effect on mTOR activity in the host cell (67, 68, 71–73). Individual components from other pathogens have also been reported to inactivate the mTOR complex in the host cell by different mechanisms. A Leishmania surface protease, GP63, cleaves mTOR complex and inactivates it (68), whereas B. malayi microfilariae inactivate the mTORC1 complex, possibly by secreting a rapamycin homolog (71). In contrast to inhibiting mTOR signaling, some pathogens, such as influenza virus and Toxoplasma, activate mTOR signaling in the host cells, suggesting that different pathogens affect mTOR signaling in distinct ways (69, 70, 75). The mTOR network in innate immune cells is influenced by a variety of stimuli, including Toll-like receptors (TLR) (76). We have shown here that the known antagonistic effect of SL-1 on the TLR2 signaling pathway (39) does not play a role in SL-1–induced lysosomal expansion. Although whether other TLR's are involved remains to be examined.

SL-1 alone has been suggested to play role in phagosome acidification because phagosomes containing sulfolipid-coated silica beads acidify more compared with control lipid (77). Our results of enhanced lysosomal delivery of pHrodo-E. coli to lysosomes in SL-1–treated cells shows that SL-1 alone can promote phagosome maturation of a different phagocytic cargo as well. However, whereas E. coli is readily delivered to lysosomes, pathogenic Mtb resist phagosome maturation. Thus the presence of SL-1 on the WT Mtb suggests an interesting scenario where the mechanisms of active phagosome maturation arrest could be countered to a degree by SL-1. In agreement with this, mutants that overproduce acetylated sulfated glycolipid (AC4SGL) cannot arrest phagosome maturation and are readily delivered to lysosomes (77). On the other hand, our study shows that MtbΔpks2, which lacks SL-1, exhibits a further reduction in the delivery to lysosomes. In contrast to these studies, an earlier work suggested that SL-1 inhibits phagosome maturation in murine peritoneal macrophages (78). These differences could be attributed to multiple factors such as the intrinsic differences between different macrophages, the different assays systems employed, the high concentrations of SL-1 used, or potential minor bioactive substances co-purified with SL-1 (39). Further studies with synthetic analogs of SL-1 (39, 79) could eliminate potential artifacts. Moreover, accurate detection and quantification of individual secreted Mtb lipid species within infected macrophages could establish a physiologically relevant concentration range for these molecules. New methods enabling detection of individual bacterial lipids in host cells and tissues during infection (80) could help address these critical issues directly.

Mtb mutants overproducing AC4SGL show compromised intracellular bacterial survival (77), in line with the observation of most Mtb mutants fail to arrest phagosome maturation. Our results here extend this correlation the other way by showing that mutant Mtb that better arrest phagosome maturation survive better. In agreement with our results, a different SL-1–specific M. tuberculosis mutant, which lacks sulfotransferase stf0, the first committed enzyme in the SL-1 biosynthesis pathway, also shows a hypervirulent phenotype (79) in human macrophages. Our results with MtbΔpks2 confirms the hypervirulent phenotype of SL-1 deletion and demonstrates that presentation of SL-1 to the host cells in the context of Mtb infection influences host lysosomal biogenesis, phagosome maturation, and intracellular bacterial survival.

In contrast to their enhanced survival phenotype in human macrophages, MtbΔpks2 and MtbΔstf0 do not show a survival phenotype in mouse and guinea pig infection models in vivo (79, 81). Despite these differences, our data shows that altered lysosomal homeostasis, mediated by SL-1, is central to both human and mouse macrophages. The differential ability of human macrophages, such as the production of anti-microbial peptides (79), or additional compensatory mechanisms during in vivo infections could contribute to these differences. The precise contributions of lysosomal rewiring to Mtb trafficking and survival during in vivo infections require further studies. Similarly, it will be interesting to extend these studies to clinical isolates of Mtb, which differ in SL-1 gene expression and lipid levels (82–84). Some strains of the “ancestral” Clade 2 show reduced expression of genes in the SL-1 biosynthetic pathway (85), whereas a recent report shows an Mtb strain belonging to the ancestral lineage with a point mutation in the papA2 gene, which confers it a loss of SL-1 phenotype (86). The contribution of the lysosomal alterations and their differential subcellular localization to the distinct inflammatory responses elicited by these phylogenetically distant strains will be interesting to explore.

Why should Mtb harbor such molecules that are apparently beneficial to the hosts? Presence of lipids like SL-1 on the surface could provide Mtb with a means to regulate or fine-tune its own survival by modulating host lysosomes and their own intracellular trafficking. Generation of reliable probes to accurately quantify individual lipid species such as SL-1 on the bacteria during infection could play a key role in exploring this idea and enable accurate assessment of variations within and across different mycobacterial strains and infection contexts. The discovery that structurally unrelated lipids (SL-1 and PIM6) independently exhibit the same phenotype of enhancing lysosomal biogenesis shows the redundancy in the system. Redundancy is thought to confer distinct advantages to the pathogen and enable robust virulence strategies without compromising on fitness (87). Alternatively, elevated lysosomal levels could be a response of the host cells recognizing mycobacterial lipids such as SL-1. Further dissection of the exact molecular targets of these lipids would be important to identify host mediators involved in the process and dissect these possibilities.

The success of M. tuberculosis depends critically on its ability to modulate crucial host cellular processes and alter their function. Our results here define the elevated lysosomal system as a key homeostatic feature for intracellular M. tuberculosis infection and uncover a new paradigm in M. tuberculosis-host interactions, of Mtb and lysosomes reciprocally influencing each other. Understanding the nature of this altered homeostasis and its consequences for pathogenesis will enable the development of effective counter strategies to combat the dreaded disease.

Experimental procedures

Mycobacterial strains and growth conditions

M. tuberculosis (H37Rv) expressing GFP was provided by Dr. Amit Singh (Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore). M. bovis BCG expressing GFP was a kind gift from Jean Pieters (University of Basel). WT M. tuberculosis, strain CDC1551 (NR-13649), and M. tuberculosis Δpks2, strain CDC1551: transposon mutant 1046 (MT3933, Rv3825c, NR-17974), were obtained from BEI resources, NIAID, National Institutes of Health. M. tuberculosis CDC1551 WT and M. tuberculosis Δpks2 CDC1551 strains were transformed with pMV762-roGFP2 vector (a kind gift from Dr. Amit Singh, IISc, Bangalore) for subsequent experiments. Mycobacterial strains were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 (BD Difco 271310) supplemented with 10% OADC (BD Difco 211886) at 37 °C. Before infection, bacterial clumps were removed by centrifugation at 80 × g and supernatant was pelleted, re-suspended in RPMI media, and used for infection.

Cell culture and infection

THP-1 monocytes were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco™ 31800022) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco™ 16000-044). THP1 monocytes were differentiated to macrophages by treatment with 20 ng/ml of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich, P8139) for 20 h followed by incubation in PMA-free RPMI 1640 medium for 2 days and used for infections. THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages were incubated with mycobacteria for 4 h followed by the removal of extracellular bacteria by multiples washes. Infected cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma 158127) at 2 and 48 hpi and were used for subsequent experiments. For infection in RAW macrophages, bacteria were incubated with cells for 2 h followed by removal of extracellular bacteria by multiples washes. Human primary monocytes were isolated from buffy coats and differentiated to macrophages as described previously (23, 33) and used for infection assays. The following reagents were obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: macrophage cell line derived from wildtype mice (NR-9456) and macrophage cell line derived from TLR2 knockout mice (NR-9457) and were cultured according to the manufacturer's instructions.

CFU assay

THP1 monocyte-derived macrophages were infected with WT or pks2 KO CDC1551 M. tuberculosis-GFP. At 0 and 48 h post-infection, cells were lysed with 0.05% SDS (Himedia GRM205) and plated in multiple dilutions on 7H11 (BD Difco 0344C41) agar plates. Colonies were counted after incubation at 37 °C for 3-4 weeks.

Immunostaining, imaging, and image analysis

For immunostaining of different markers, differentiated THP-1 macrophages after infection were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS, and permeabilized with SAP buffer (0.2% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich S4521), 0.2% gelatin (Himedia Laboratories TC041) in PBS) for 10 min at room temperature. Primary antibodies Lamp1 (DSHB H4A3) and Lamp2 (DSHB H4B4), anti-Mtb (Genetex GTX20905) and phospho-p70 S6 kinase (Thr-389) (CST) were prepared in SG-PBS (0.02% saponin, 0.2% gelatin in PBS) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Gelatin in the buffers was used as a blocking agent and saponin as detergent. After washing with SG-PBS, cells were incubated in Alexa-tagged secondary antibodies (Life Technologies, Invitrogen) prepared in SG-PBS for 1 h at room temperature, washed, stained with 1 μg/ml of 4[prime],6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and 3 μg/ml of Cell Mask Blue (Life Technologies, Invitrogen), and imaged using either confocal microscopes FV3000, the automated spinning disk confocal Opera Phenix (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) or Nikon Ti2E.

Images were analyzed by CellProfiler, Harmony, or Motiontracking image analysis platforms. CellProfiler pipelines similar to those previously established (7, 33) were used. In all cases, images were segmented to identify nuclei, cells, bacteria, and lysosomal compartments. Objects such as bacteria and lysosomes were related to individual cells to obtain single cell statistics, and multiple parameters relating to their numbers, sizes, intensities, as well as intra-object associations were extracted. MS Excel and RStudio platform with libraries ggplot2, dplyr, and maggitr were used for data analysis and plotting. Most data are plotted as box plots, which show the minimum, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile and maximum values. Individual data points corresponding to single cells are overlaid on the box plots. Statistical significance between different sets was determined using Mann-Whitney unpaired test or unpaired Student's t test with unequal variance.

Flow cytometry

Samples were analyzed using FACS Aria Fusion cytometer. Using FSC-Area versus SSC-Area scatter plot, the macrophage population was gated for further use. Based upon fluorescence levels in the uninfected sample, gates for uninfected and infected cells were defined. Furthermore, cargo uptake, endosomal, and lysosomal levels were compared between the gated infected and uninfected populations. For each sample, 10,000 gated events were acquired. FSC files exported using FlowJo were subsequently analyzed by RStudio.

Identifying important morphological features from high content image analysis and classification of infected cells from lysosomal features

Two separate data sets from human primary macrophages infected with M. bovis BCG-GFP (named Exp1 and Exp2) were used for analysis. Data set Exp1 contained a total of 37,923 cells of which 18,546 were infected. Data set Exp2 contained a total of 36,476 cells of which 15,022 were infected. Each data set has multiple features relating to cells, bacteria, and lysosomes, as well as their associations with each other. Of these features, 16 lysosomal parameters and 11 cellular parameters were chosen for further analysis. The data were split into training and test set (7:3) and the model was trained using logistic regression with an L1 penalty. Logistic regression uses a logistic function to model one or more independent variables to predict a categorical variable (88). Applying an L1-regularization penalty using the parameter c forces the weights of many of the features to go to zero. The best regularization parameter was identified by 20-fold cross-validation on the training set. Because all the features were selected for the best regularization parameter (), we further reduced c. Classification metrics, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score were calculated for infected and noninfected cells for a range of regularization parameters (1, 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0005, 0.0001, and 0.00018). The value of forces the model to pick a single feature for classification. Accuracy is defined as total true predictions divided by false predictions. Precision measures the ability of the model to make correct predictions. Recall measures the fraction of correct predictions from the total number of cells belonging to the given class. F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. F1-score, precision, and recall were calculated for each class (infected, noninfected). To find the contribution of individual features for classification accuracy, we used logistic regression on single features with 20-fold cross-validation and reported the accuracy of training and test set for both data sets.

The random forest algorithm considers predictions of multiple decision trees to perform classification (88, 89). Furthermore, a random forest also enables us to rank the features, by measuring the contribution of individual features to each of the constituent decision trees. Note that random forests thus use multiple models, in contrast to logistic regression, which builds a single model; in both cases, the goal is to classify a cell as infected or noninfected. Parameters for random forest were estimated using a grid search with 20-fold cross-validation. The best parameters were based on maximum average accuracy and were used for finding feature contribution and ranking. For infections in THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages (with M. bovis BCG-GFP or E. coli), similar analysis was done, with a difference that the features were extracted from the images using Harmony image analysis platform.

Cargo pulsing and functional endocytic assays

Alexa-labeled Human Holo-Transferrin (Life Technologies, Invitrogen T23365, T2336; 5 µg/ml) and dextran (Life Technologies, Invitrogen D22914, D-1817; 200 µg/ml) were used to quantify endocytic uptake capacity in cells. Cargo pulse for endocytic assays was performed by individually diluting the respective cargo at the indicated concentrations in RPMI media and incubating the cells at 37 °C and 5% CO2, followed by washing with media and fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde. LysoTracker Red (Life Technologies, Invitrogen L7528; 100 nm) and Magic Red cathepsin B (MRC) (Bio-Rad ICT937) were used to stain lysosomes in the cells. For LysoTracker Red labeling, cells were incubated in complete RPMI containing 100 nm LysoTracker Red for 30 min and 1 h for MRC followed by fixation with 1% paraformaldehyde for 1 h at room temperature.

Phagosomal trafficking assay

RAW macrophages were seeded to Costar white-bottom 384-well plates (15,000 cells/well) and pulsed with pHrodo-labeled E. coli (ThermoFisher Scientific, P35361) in CO2 independent media (ThermoFisher Scientific, 18045088). Plates were transferred to Varioskan LUX Multimode Microplate Reader (ThermoFisher Scientific) maintained at 37 °C and fluorescence reading of treated and control cells was recorded with a 2-min time interval.

In vivo infection and single cell suspension preparation

BALB/c, C57BL/6J, or C57BL/6NJ mice were infected with M. tuberculosis GFP using the Glas-Col inhalation exposure chamber (at the indicated cfu). Mice were sacrificed post-infection at the indicated time points, and infected lungs were dissected out, minced, and placed in Miltenyi GentleMACS C-tubes containing 2 ml of dissociation buffer (RPMI media with 0.2 mg/ml of Liberase (Sigma-Aldrich 5466202001) and 0.5 mg/ml of DNase (Sigma-Aldrich 11284932) and subjected to the inbuilt lung dissociation protocol 1 of Miltenyi GentleMACS, followed by incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 30 min with low agitation (50 rpm) and a second 20-s dissociation with lung dissociation protocol 2 (Miltenyi GentleMACS). The suspension was passed through a 70-μm cell strainer and then pelleted at 1200 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was re-suspended in 1 ml of erythrocyte lysis buffer (155 mm NH4Cl, 12 mm NaHCO3, and 0.1 mm EDTA) for 1 min and immediately added to 10 ml of RPMI media. Cells were centrifuged again, re-suspended in RPMI media with 10% fetal bovine serum, and plated for 2 h in RPMI media with 10% fetal bovine serum for macrophage selection based on adherence. After 2 h, nonadhered cells were washed and adhered cells were used for the assay. Adherent cells were immunostained with F4/80 PE-Vio615 (Miltenyi Biotec REA126) and CD11b (DSHB M1/70.15.11.5.2) antibody to check for macrophage purity. All procedures involving animals were approved by the NCBS Animal Ethics Committee and the IISc Animal Ethics Committee.

M. tuberculosis component screen

The following M. tuberculosis H37Rv surface components were obtained through BEI resources, NIAID, NIH: M. tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, purified phosphatidylinositol mannosides 1 and 2 (PIM1,2), NR-14846; M. tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, purified phosphatidylinositol mannoside 6 (PIM6), NR-14847; M. tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, purified LAM, NR-14848; M. tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, purified lipomannan (LM), NR-14850; M. tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, total lipids, NR-14837; M. tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, purified trehalose dimycolate (TDM), NR-14844; M. tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, purified SL-1, NR-14845; NR-14850; M. tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, purified mycolylarabinogalactan-petidoglycan (mAGP), NR-14851; M. tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, purified arabinogalactan, NR-14852; M. tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, purified mycolic acid methyl esters, NR-14854; M. tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, mycobactin (MBT), NR-44101; M. tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, purified trehalose monomycolate (TMM), NR-48784. They were reconstituted according to the supplier's instruction and treated on THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages at the indicated concentration. Components that affected lysosomes were selected for further use.

Immunoblotting

To compare protein levels by immunoblotting, PMA-differentiated THP1 cells were treated with selected mycobacterial surface components, lysed using cell lysis buffer (150 mm Tris-HCl, 50 mm EDTA, 100 mm NaCl, protease inhibitor mixture) at 4 °C for 20 min, passaged through 40-gauge syringe followed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was used for blotting. The following antibodies were used: p70 S6 kinase (49D7), phospho-p70 S6 kinase (Thr-389), phospho-4E-BP1 (2855T), 4E-BP1 (9644T), GAPDH (5174S), and β-actin (13E5). These antibodies were procured from Cell Signaling Technologies. LAMP-1 (H4A3 and 1D4B) antibodies were procured from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank.

Cell transfection and nuclear-cytoplasmic TFEB translocation

pEGFP-N1-TFEB was a gift from Shawn Ferguson (Addgene plasmid no. 38119). HeLa cells were seeded at 70% confluence in 8-well chambers and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (ThermoFisher Scientific, 11668030). For RAW macrophages, Lipofectamine 3000 (ThermoFisher Scientific, L3000015) was used. Transfection was performed following the manufacturer's protocol. Transfection complex was washed after 6 h, and SL-1 treatment was started 12 h post-transfection. Cells were fixed and imaged after 24 h of SL-1 treatment (25 µg/ml). The boundary of transfected cells was marked manually based on bright-field or cytoplasmic stain, cell mask blue and DAPI signal was used to segment nucleus. Nuclear-cytoplasmic translocation of TFEB was assessed by comparing TFEB fluorescence ratio between nuclear and cytoplasmic regions. For siRNA transfection, 15,000 THP1 cells were seeded per well in a 384-well plate and were transfected with either universal negative control 1 (UNC1) (Millipore Sigma, SIC001) or esiRNA human TFEB (Millipore Sigma, EHU059261) siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAimax (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 13778100) according to the manufacturer's protocol for 48 h and were used for further experiments.

Data availability

All data generated for the study are contained in the manuscript. Data sets used to generate the model to predict infected cell based on lysosomal feature is available upon request to V. Sundaramurthy (varadha@ncbs.res.in).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Profs. Jean Pieters for the kind gift of M. bovis expressing GFP and Marc Bickle for critical comments, Mahamad Ashiq for technical assistance, and Harmanjit Singh Bansal for assistance in data analysis. We acknowledge BEI resources for providing M. tuberculosis components and CDC1551 strains used in the study. The BSL3 facility in the Center for Infectious Disease Research (CIDR), Indian Institute of Science (IISc), is gratefully acknowledged for Mtb animal infections. We acknowledge the Central Imaging and Flow Cytometry (CIFF), Screening, Animal house and BSL3 facilities at NCBS. The study has been approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee and Institutional Biosafety committees from NCBS and IISc, as well as the Institutional Human Ethics committee from NCBS.

This article contains supporting information.

Author contributions—K. S., M. S., and K. R. formal analysis; K. S. and M. G. validation; K. S., M. G., M. M., and V. S. investigation; K. S., M. G., and V. S. methodology; K. S., M. G., M. S., A. S., and V. S. writing-review and editing; M. S. and K. R. software; M. M., R. R., K. R., A. S., and V. S. resources; V. S. conceptualization; V. S. supervision; V. S. funding acquisition; V. S. writing-original draft; V. S. project administration.

Funding and additional information—This work was supported by National Center for Biological Sciences-Tata Institute of Fundamental Research core funds (to V. S.), DST Max-Planck partner group (to V. S.), and a Ramalingaswamy re-entry fellowship (to V. S.).

Conflict of interest—The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- PIM

- phosphatidylinositol mannoside

- LAM

- lipoarabinomannan

- SL-1

- sulfolipid

- TFEB

- transcription factor EB

- cfu

- colony-forming unit

- hpi

- hours post-infection

- PMA

- phorbol myristate acetate

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- MRC

- Magic Red cathepsin

- pks2

- polyketide synthase 2

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

References

- 1. Armstrong J. A., and Hart P. D. (1971) Response of cultured macrophages to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with observations on fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. J. Exp. Med. 134, 713–740 10.1084/jem.134.3.713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cambier C. J., Falkow S., and Ramakrishnan L. (2014) Host evasion and exploitation schemes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell 159, 1497–1509 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pieters J. (2008) Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the macrophage: maintaining a balance. Cell Host Microbe 3, 399–407 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Russell D. G. (2001) Mycobacterium tuberculosis: here today and here tomorrow. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 569–578 10.1038/35085034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gutierrez M. G., Master S. S., Singh S. B., Taylor G. A., Colombo M. I., and Deretic V. (2004) Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell 119, 753–766 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar D., Nath L., Kamal M. A., Varshney A., Jain A., Singh S., and Rao K. V. (2010) Genome-wide analysis of the host intracellular network that regulates survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell 140, 731–743 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sundaramurthy V., Korf H., Singla A., Scherr N., Nguyen L., Ferrari G., Landmann R., Huygen K., and Pieters J. (2017) Survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis BCG in lysosomes in vivo. Microbes Infect. 19, 515–526 10.1016/j.micinf.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Levitte S., Adams K. N., Berg R. D., Cosma C. L., Urdahl K. B., and Ramakrishnan L. (2016) Mycobacterial acid tolerance enables phagolysosomal survival and establishment of tuberculous infection in vivo. Cell Host Microbe 20, 250–258 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vandal O. H., Pierini L. M., Schnappinger D., Nathan C. F., and Ehrt S. (2008) A membrane protein preserves intrabacterial pH in intraphagosomal Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Med 14, 849–854 10.1038/nm.1795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Russell D. G., Mwandumba H. C., and Rhoades E. E. (2002) Mycobacterium and the coat of many lipids. J. Cell Biol. 158, 421–426 10.1083/jcb.200205034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beatty W., Ullrich H. J., and Russell D. G. (2001) Mycobacterial surface moieties are released from infected macrophages by a constitutive exocytic event. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 80, 31–40 10.1078/0171-9335-00131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beatty W. L., and Russell D. G. (2000) Identification of mycobacterial surface proteins released into subcellular compartments of infected macrophages. Infection Immun. 68, 6997–7002 10.1128/iai.68.12.6997-7002.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beatty W. L., Rhoades E. R., Ullrich H. J., Chatterjee D., Heuser J. E., and Russell D. G. (2000) Trafficking and release of mycobacterial lipids from infected macrophages. Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark) 1, 235–247 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vergne I., Fratti R. A., Hill P. J., Chua J., Belisle J., and Deretic V. (2004) Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome maturation arrest: mycobacterial phosphatidylinositol analog phosphatidylinositol mannoside stimulates early endosomal fusion. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 751–760 10.1091/mbc.e03-05-0307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fratti R. A., Chua J., Vergne I., and Deretic V. (2003) Mycobacterium tuberculosis glycosylated phosphatidylinositol causes phagosome maturation arrest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 5437–5442 10.1073/pnas.0737613100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]