Abstract

Background

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease with systemic repercussions and an association with comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, and obesity. Psoriasis patients have a higher prevalence of obesity compared to the general population. Diet is a relevant environmental factor, since malnutrition, inadequate body weight, and metabolic diseases, in addition to the direct health risk, impair the treatment of psoriasis.

Objectives

To evaluate food intake patterns, anthropometric, and metabolic syndrome-related aspects in psoriasis patients.

Methods

Cross-sectional study through anthropometric assessment and food frequency questionnaire. Food frequency questionnaire items were evaluated by exploratory factor analysis and identified dietary patterns were analyzed by multivariate methods.

Results

This study evaluated 94 patients, 57% female, with a mean age of 54.9 years; the prevalence of obesity was 48% and of metabolic syndrome, 50%. Factor analysis of the food frequency questionnaire identified two dietary patterns: Pattern 1 – predominance of processed foods; Pattern 2 – predominance of fresh foods. Multivariate analysis revealed that Patterns 1 and 2 showed inverse behaviors, and greater adherence to Pattern 2 was associated with females, eutrophic individuals, absence of lipid and blood pressure alterations, and lower waist-to-hip ratio and skin disease activity.

Study limitations

Monocentric study conducted at a public institution, dependent on dietary memory.

Conclusion

Two dietary patterns were identified in a Brazilian sample of psoriasis patients. The prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome were greater than in the adult Brazilian population. The fresh diet was associated with lower indicators of metabolic syndrome in this sample.

Keywords: Feeding behavior, Food consumption, Psoriasis

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, genetically based, and immunologically mediated inflammatory disease. It has systemic repercussions and is associated with comorbidities, such as metabolic syndrome (MS), arterial hypertension (AH), dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus (DM), cardiovascular disease, malignant neoplasia, and affective disorders.1, 2

It affects about 1.31% of the Brazilian population and, despite not being contagious and having a benign course, it has an important economic impact, as well as an impact on the quality of life of patients.3

Psoriasis triggers an abnormal release of cytokines involved in the inflammatory process, including IFN-γ, IL-1, IL-6, IL-17, IL-8, and TNF-α, which promote a chronic systemic inflammatory state, favoring the development of comorbidities.4

There is a higher prevalence of obesity (34%) among patients with psoriasis when compared with the general population (18%); moreover, the higher the body mass index (BMI), the greater the risk of developing psoriasis.5 Likewise, there is an association between the increase in abdominal circumference (AC) and hip circumference (HC) and the onset of psoriasis, which corroborates its association with MS. MS comprises a set of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and is also related to systemic inflammation.6, 7

In addition to drug treatment, changes in eating behavior and physical activity emerge as potential strategies for adjuvant treatment of psoriasis in order to reduce comorbidities.8, 9 Diet is an environmental factor of high interest to patients, since malnutrition, inadequate body weight, and metabolic diseases, in addition to the direct risk they pose to the general health, impair the treatment of psoriasis.10, 11

Due to the lack of consensus and guidelines establishing a specific diet for these patients and considering that there are few studies that evaluated the food consumption of patients with psoriasis, it is necessary to characterize their nutritional profile and dietary patterns in order to outline dietary strategies aimed at improving the quality of the diet in parallel with the treatment of the disease.

This study had as its primary objective the assessment of food consumption patterns; secondly, it aimed to correlate food consumption with anthropometric and clinical data and with MS markers in patients with psoriasis treated at a public dermatology clinic.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study that included psoriasis patients seen at the Dermatology outpatient clinic of the Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu – Universidade Estadual Paulista, Botucatu, SP (Brazil), from February to August 2019.

The diagnoses of psoriasis were established by a qualified dermatologist, and the study included adults (> 18 years) of both sexes with all clinical types and all stages of severity.

Sampling was carried out for convenience, recruiting consecutive, consenting patients during their medical consultations at the institution. Patients following specific diets (such as celiac), patients with malabsorptive syndromes or with limitations that would make dietary or anthropometric characterization impossible were not included.

All those who agreed to participate in the research signed an informed consent form. The project was approved by the institution's Research Ethics Committee (protocol No. 3,317,869).

Study variables

The Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), adapted to assess food consumption, was applied; patients were asked about the consumption of 76 types of food. This evaluation allowed the identification of the consumption of these foods over a period of one year, stratified as daily, weekly, monthly, and annual portions.12

Demographic and socioeconomic data, as well as duration of psoriasis treatment, were collected at the time of anthropometric and dietary assessment.

For anthropometric assessment, body weight and height were measured and later on calculation of the body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), the stratification for diagnosis was as folloows: malnutrition (<18.5), eutrophy (18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9), and obesity (≥30).13

Waist circumference (WC) was measured at the midpoint between the last rib and the iliac crest using a tape measure; HC was also measured to establish the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR = Waist [cm]/Hip [cm]), allowing the evaluation of parameters of android obesity and the risk for cardiovascular disease according to the classifications by sex and age.14

Food consumption (FFQ) and anthropometric assessments were performed by a nutritionist, after routine consultation at the dermatology outpatient clinic.

As all patients were under treatment, more detailed clinometric scores (such as the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index [PASI]) are impaired due to the treatment; therefore, disease activity was estimated by the presence/absence of skin and joint lesions at the consultation.15, 16

The routine clinical assessment and the clinical exams were used to assess the presence of MS using the criteria of the NCEP ATP III (National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults) to evaluate the components of metabolic syndrome: presence of DM or fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL; abdominal circumference > 102 cm for men and 88 cm for women; triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL; HDL < 40 mg/dL for men and <50 mg/dL for women; and blood pressure greater than or equal to 130/85 mmHg, or hypertension treatment.17

Statistical analysis

Qualitative data were described as absolute and percentage values. Quantitative data were represented as means and standard deviations, or medians and quartiles (p25–p75) if normality was not observed in the Shapiro–Wilk test.18

Dietary data (FFQ) were tabulated and converted into daily food consumption, then subjected to an exploratory factor analysis to determine dietary patterns and individualized standardized adherence scores to each dietary pattern (ranging from −3 to +3). The analysis included those foods mentioned by at least 30% of the sample; in the factorial model, only those with a factor load > 0.3 were kept. Principal component analysis was used for the extraction of dietary patterns, evaluated by the KMO test (Kaiser–Meyer–Oklin), with varimax rotation.19

To explain the variations in the scores of adherence to each diet pattern, a generalized linear model (gamma distribution, log binding function) was adjusted using the anthropometric, demographic, and psoriasis variables (joint disease and cutaneous activity) as predictor variables. The β coefficient of the regression was used to estimate the association effect.20

Subsequently, the variables were analyzed in a multivariate manner based on the multiple correspondence analysis of two dimensions and were then arranged on the perceptual map. The dimension of the effect was estimated by the inertia in each dimension and the associations between the variables were represented by their geometric proximity.21 Continuous variables were categorized as tertiles.

The sample was calculated in order to represent variables present in up to 10% of a population of up to 300 patients with psoriasis, with a standard error of up to 5%.22 Two-tailed p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. SAS for Windows, v.9.4 and IBM SPSS v. 25 were used for statistical analyses.

Results

The study included 94 psoriasis patients; Table 1 presents the main clinical and demographic data. The low educational and family income, high prevalence of comorbidities (especially MS), obesity, and high risk for the onset of cardiovascular disease according to the WHR were noteworthy. All patients were under treatment, and the PASI ranged from 0 to 17.6; 84% presented skin lesions on the day of the interview.

Table 1.

Demographic, socioeconomic, anthropometric, and clinical characteristics of patients with psoriasis interviewed at the dermatology clinic (n = 94).

| Variables | Results |

|---|---|

| Sexa | |

| Female | 54 (57) |

| Male | 40 (43) |

| Age (years)b | 54.9 (12.8) |

| Educationalstatusa | |

| Illiterate | 3 (3) |

| Elementary school | 51 (54) |

| High school | 31 (33) |

| University education | 9 (10) |

| Family income (minimum wage)a | |

| 1 | 17 (18) |

| 2 | 44 (47) |

| ≥3 | 33 (35) |

| Anthropometric profile | |

| Weight (kg)b | 84.8 (17.1) |

| Height (cm)b | 1.7 (0.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2)b | 31.1 (6.2) |

| Eutrophic (18.5–24.9)a | 11 (12) |

| Overweight (25–29.9)a | 38 (40) |

| Obesity (>30)a | 45 (48) |

| Waist circumference (cm)b | 109.0 (13.7) |

| Hip circumference (cm)b | 104.2 (14.7) |

| WHR (cm)b | 1.06 (0.15) |

| Clinical data | |

| Disease duration (years)b | 15.7 (12.1) |

| Skin disease activity (plaques)a | 75 (84) |

| Joint diseasea | 11 (12) |

| PASIb | 5.3 (4.8) |

| Comorbiditiesa | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 43 (49) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 39 (43) |

| Hypertension (mmHg) | 42 (47) |

| Altered blood glucose or DM (mg/dL) | 34 (38) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 47 (50) |

DM, diabetes mellitus; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; BMI, body mass index.

n (%).

Mean (SD).

As to systemic treatments, 32% used methotrexate, 23% used acitretin, and 45% were on immunobiological drugs (12% infliximab, 11% adalimumab, 10% secukinumab, 8% etanercept, 4% ustekinumab). There were no cyclosporine users in this sample.

Patients with psoriasis did not follow an exclusive diet, and all reported some variability in the food consumed. From the factorial analysis of the food consumption reported by the sample, two dietary patterns were identified (Table 2). Pattern 1 (processed diet) consisted of industrialized foods, rich in saturated fats, sugar, and sodium, i.e., a diet with high caloric density and low nutritional quality. Pattern 2 (fresh diet) was characterized by the consumption of fruits and vegetables, which are sources of vitamins, minerals, fibers, and bioactive compounds, in addition to offering high nutritional support in qualitative terms.

Table 2.

Food patterns and factorial loads of the foods that make up each pattern, identified by analyzing the sample food frequency questionnaire.

| Pattern 1 (processed diet) | FL | Pattern 2 (fresh diet) | FL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pizza | 0.79 | Raw vegetables | 0.73 |

| Deep fried savory snack | 0.74 | Cooked vegetables | 0.73 |

| Filled cookie | 0.69 | Tomato | 0.70 |

| Charcuterie | 0.69 | Cooked greens | 0.68 |

| Cheese | 0.67 | Broccoli | 0.62 |

| Sandwiches | 0.66 | Carrot | 0.59 |

| Soda | 0.64 | Lettuce | 0.57 |

| Flour | 0.53 | Orange | 0.50 |

| Burger | 0.52 | Salt | 0.42 |

| Mayonnaise | 0.45 | Apple | 0.42 |

| Baked savory snack | 0.38 | Olive oil/cooking oil | 0.39 |

| Breads | 0.38 | Banana | 0.38 |

| Desserts | 0.37 | Melon | 0.38 |

| Sausage | 0.35 | Papaya | 0.38 |

| Industrialized juice | 0.32 | Potato | 0.31 |

| Butter | 0.32 |

FL, factorial load; KMO = 0.65.

Adherence scores to each dietary pattern (Table 3) were assessed according to anthropometric, demographic, and clinical (joint and cutaneous activity) variables. Pattern 1 was associated with more recent psoriasis. The female sex showed greater adherence to Pattern 2, as well as patients with higher age and income. There was an inverse association of WHR with adherence to Pattern 2, as well as with cutaneous activity (plaques).

Table 3.

Multivariate comparison of the scores of dietary patterns with anthropometric, demographic, and psoriasis-related variables (n = 94).

| Variable | Pattern 1 (processed) |

Pattern 2 (fresh) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β coefficient | p-Valuea | β coefficient | p-Valuea | |

| Female gender | −0.027 | 0.748 | 0.268 | 0.006 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.123 | 0.05 | 0.045 |

| Educational status | ||||

| College or university degree | 0.042 | 0.760 | −0.183 | 0.329 |

| High school | −0.090 | 0.278 | −0.069 | 0.547 |

| Illiterate + elementary school | (−) | |||

| Income (minimum wages) | 0.020 | 0.327 | 0.099 | 0.003 |

| BMI | −0.009 | 0.076 | −0.009 | 0.492 |

| WHR | 0.230 | 0.362 | −0.340 | 0.054 |

| Disease duration | −0.005 | 0.034 | −0.005 | 0.154 |

| Skin activity | −0.110 | 0.233 | −0.353 | 0.001 |

| Joint disease | −0.145 | 0.096 | −0.014 | 0.427 |

| Arterial hypertension | −0.074 | 0.256 | −0.037 | 0.852 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.092 | 0.208 | 0.176 | 0.142 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | −0.084 | 0.333 | 0.117 | 0.938 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.187 | 0.057 | −0.063 | 0.526 |

BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

Adjusted p-value.

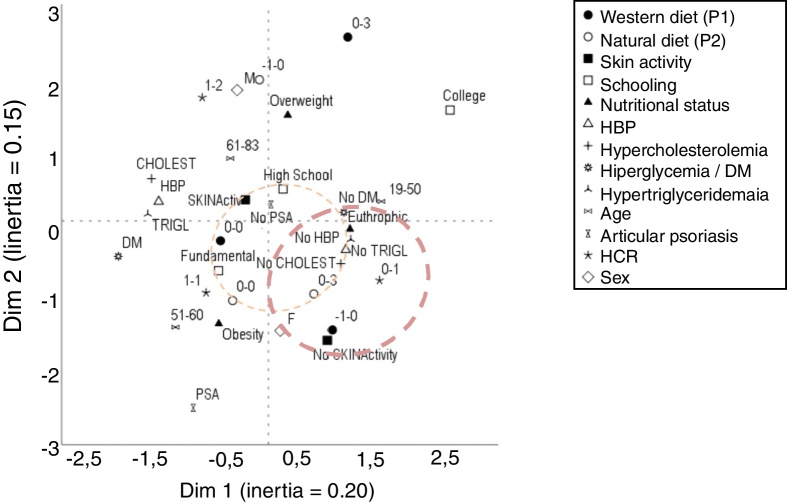

The multivariate correspondence analysis (Fig. 1) indicated a relationship between lower adherence to the processed diet and greater adherence to the fresh diet, as well as with females, absence of lipid and blood pressure alterations, in addition to lower WHR and eutrophy. The presence of joint psoriasis was related with obesity.

Figure 1.

Perceptual map of the main demographic, clinical, and anthropometric variables and adherence to dietary patterns in 94 patients with psoriasis. Quantitative variables were categorized according to the tertile of the distributions. DM, diabetes mellitus; BMI, body mass index; WTH, waist-to-hip ratio; AH, arterial hypertension. Standardized scores for P1 and P2 ranged from −3 to +3 according to adherence to each dietary pattern.

Discussion

Two patterns of food consumption were identified in patients with psoriasis, which were associated with clinical and anthropometric factors and MS markers.

Nutrition is a complex phenomenon, and since isolated foods or nutrients are generally not considered to be harmful to health, the assessment of the cumulative effect of diet on health through dietary patterns can help determine which are the most favorable for a population and provide a more accurate description of eating habits.23

Food patterns are transitioning worldwide, influenced by several factors, such as income, food costs, individual food preferences, beliefs, cultural traditions, and geographic, behavioral, and socioeconomic aspects.24

According to the Family Budget Survey (Pesquisa de Orçamento Familiar; POF 2018/2019), an increase in the consumption of foods with lower nutritional density, higher concentration of energy, total lipids, sugar, and sodium has been observed in Brazil over the past decades.25, 26 The most important changes in this regard were a reduction in the consumption of beans (31%), roots and tubers (32%), and eggs (84%), and an increase in the consumption of cookies (400%), soft drinks (400%), meats (50%), and milk (36%), i.e., an increase in diets rich in processed and ultra-processed foods, characterizing the so-called Western diet, which is associated with increased obesity, MS, neoplasms, and inflammatory diseases.27, 28

The “Western diet” pattern has been a characteristic of the modern diet, with convenient, easily accessible, industrialized foods with low nutritional content.8 In the present study, adherence to the Western pattern (Pattern 1) was associated with overweight and presence of MS markers. All MS markers are modifiable risk factors; changes in lifestyle, diet, and exercise can favorably impact the onset of diseases.25, 29

In contrast, Pattern 2 was characterized by the consumption of fresh foods (fruits and vegetables), which are sources of vitamins, minerals, fibers, and bioactive compounds, in addition to offering a high nutritional intake. These are foods that provide micronutrient balance. Nutrients present mainly in fresh foods – such as fibers, vitamins, minerals, and mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids – have antioxidant effects, which can reduce systemic inflammation and potentially interfere in the clinical picture of psoriasis and metabolic diseases.9, 11, 27

Cross-sectional studies have shown that a “healthy” food pattern is associated with a lower prevalence of MS, while western/unhealthy patterns are associated with an increased risk of MS.30 In this sample, the fresh pattern was associated with absence of alterations in the lipid profile and blood pressure, in addition to a lower WHR, evidencing that diets with a high fruit and vegetable content may mitigate the effects of inflammation and MS.31

A study conducted in Croatia with 82 inpatients found improvement in psoriasis plaques and reduction in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) after four weeks of adherence to a low energy density diet.32

An Italian study followed 61 patients for 24 weeks and observed weight and WC reduction, in addition to reduced PASI and serum levels of C-reactive protein, after a calorie-reduced diet combined with low-dose cyclosporine treatment.33

Another randomized clinical study, carried out in Denmark with 60 overweight psoriasis patients who adhered to a low-calorie diet for eight weeks, showed improvement in PASI and in the quality of life index when compared with the control group.34

In Sweden, a study with 51 patients evidenced the influence of the Mediterranean diet (rich in fish, olive oil, and vegetables); after three months of intervention, individuals showed improvement in disease activity and quality of life.35 These findings corroborate the results of a study carried out in Hawaii with five patients who showed improvement in PASI of 47.8% when submitted for ten days to a diet rich in fish, whole foods, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and herbal teas.36

In the present study, the prevalence of obesity was 48%. Obesity is a growing public health challenge, and is more prevalent among individuals with psoriasis (34%) than in the general population. In Brazil, over half of the population (55.7%) are overweight and 19.8% are obese (23% in women and 20% in men).37, 38, 39

Longitudinal population-based studies suggest a causal role of obesity in psoriasis, as well as an association with poor response to treatment and greater disease severity. The increase in obesity rates and adherence to the Western diet, in addition to longevity and greater access to diagnosis, may be associated with the increase in the incidence of psoriasis.40, 41, 42

Weight control can also improve the prognosis of psoriasis and quality of life. Moreover, caloric control leads to significant improvements in skin lesions and systemic inflammatory status. Therefore, low-calorie diets can be considered an important aid factor in the prevention and treatment of psoriasis, as well as in weight management, reduction of inflammatory markers, improvement in the lipid and glucidic profiles, and reduction of the risk of associated diseases.43, 44

A vegetarian diet, provided it is well planned and structured, can be nutritionally adequate and have potential health benefits, including for individuals with psoriasis.32, 43 A new line of research, on plant-based diets, prioritizes the consumption of foods of plant origin as natural and as close to their original form as possible, advocating the consumption of food in its most complete form, free from refinement, processing, and artificial additives. It seems possible that a plant-based diet is able to influence the immune and metabolic response from changes mainly in the intestinal microbial state.45 However, these interventions require studies with appropriate designs to clarify the relationship with psoriasis.46, 47

Nutritional strategies should be encouraged for patients with psoriasis; patients should be instructed to follow a low-calorie diet, with adjustment of macronutrients, micronutrients, and stimulated to eat fresh foods, restricting the consumption of processed foods and alcohol. Dietary interventions present positive results in the control of comorbidities and response to clinical treatment, and may help prevent diseases.47

In the present sample, the multivariate analyses reinforced the inverse correlation between MS markers and adherence to Pattern 1. Moreover, the association between diet, gender, income, and disease duration should be assessed in later studies with appropriate designs.

Study limitations include its monocentric and non-randomized design, including only a population of patients from a public institution, and the evaluation through the FFQ, which is memory-dependent.

The multidisciplinary care of patients with psoriasis allows a broader assistance aimed at reducing comorbidities along with the clinical treatment. The results of this study support the need for a specific nutritional care for psoriasis, aiming at possible improvement in disease activity and the reduction of risks arising from chronic inflammatory status and comorbidities.

Conclusion

Two dietary patterns were identified in a sample of patients with psoriasis at a public healthcare institution. The prevalence of obesity and MS was significantly higher in this population than in the adult Brazilian population. Adherence to a fresh diet was associated with lower MS indicators.

Financial support

None declared.

Authors’ contributions

Tatiana Cristina Figueira Polo: Statistical analysis; approval of the final version of the manuscript; conception and planning of the study; elaboration and writing of the manuscript; obtaining, analyzing, and interpreting the data; effective participation in research orientation; intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of studied cases; critical review of the literature; critical review of the manuscript.

José Eduardo Corrente: Statistical analysis; obtaining, analyzing, and interpreting the data; critical review of the manuscript.

Luciane Donida Bartoli Miot: Approval of the final version of the manuscript; conception and planning of the study; elaboration and writing of the manuscript; obtaining, analyzing, and interpreting the data; intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of studied cases; critical review of the manuscript.

Silvia Justina Papini: Approval of the final version of the manuscript; conception and planning of the study; obtaining, analyzing, and interpreting the data; effective participation in research orientation; critical review of the manuscript.

Hélio Amante Miot: Statistical analysis; approval of the final version of the manuscript; conception and planning of the study; elaboration and writing of the manuscript; obtaining, analyzing, and interpreting the data; effective participation in research orientation; intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of studied cases; critical review of the literature; critical review of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Polo TCF, Corrente JE, Miot LDB, Papini SJ, Miot HA. Dietary patterns of patients with psoriasis at a public healthcare institution in Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:452–8.

Study conducted at the Department of Dermatology, Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Botucatu, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Souza C.S., de Castro C.C.S., Carneiro F.R.O., Pinto J.M.N., Fabricio L.H.Z., Azulay-Abulafia L. Metabolic syndrome and psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis vulgaris: quality of life and prevalence. J Dermatol. 2019;46:3–10. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milčić D., Janković S., Vesić S., Milinković M., Marinković J., Ćirković A. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:46–51. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romiti R., Amone M., Menter A., Miot H.A. Prevalence of psoriasis in Brazil – a geographical survey. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e167–e168. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiBonaventura M., Carvalho A.V.E., Souza C.D.S., Squiassi H.B., Ferreira C.N. The association between psoriasis and health-related quality of life, work productivity, and healthcare resource use in Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:197–204. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20186069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunz M., Simon J.C., Saalbach A., Psoriasis: Obesity and fatty acids. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1807. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrascosa J.M., Rocamora V., Fernandez-Torres R.M., Jimenez-Puya R., Moreno J.C., Coll-Puigserver N. Obesidad y psoriasis: naturaleza inflamatoria de la obesidad, relación entre psoriasis y obesidad e implicaciones terapéuticas. Actas Dermoifiliogr. 2014;105:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen P., Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633–639. doi: 10.1159/000455840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flegal K.M., Kruszon-Moran D., Carroll M.D., Fryar C.D., Ogden C.L. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2284–2291. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madden S.K., Flanagan K.L., Jones G. How lifestyle factors and their associated pathogenetic mechanisms impact psoriasis. Clin Nutr. 2019;2:171. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alotaibi H.A. Effects of weight loss on psoriasis: a review of clinical trials. Cureus. 2018;10:e3491. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuccotti E., Oliveri M., Girometta C., Ratto D., Di Iorio C., Occhinegro A. Nutritional strategies for psoriasis: current scientific evidence in clinical trials. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;23:8537–8551. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201812_16554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aquino E.M., Barreto S.M., Bensenor I.M., Carvalho M.S., Chor D., Duncan B.B. Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brazil): objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;4:315–324. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization Expert Committee. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry: report of a WHO Expert Committee. WHO Tech Rep Ser. 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed]

- 14.Alberti K.G., Eckel R.H., Grundy S.M., Zimmet P.Z., Cleeman J.I., Donato K.A. Harmonizing the Metabolic Syndrome: A Joint Interim Statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harari M., Shani J., Hristakieva E., Stanimirovic A., Seidl W., Burdo A. Clinical evaluation of a more rapid and sensitive Psoriasis Assessment Severity Score (PASS), and its comparison with the classic method of Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), before and after climatotherapy at the Dead-Sea. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:913–918. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korman N.J., Zhao Y., Pike J., Roberts J. Relationship between psoriasis severity, clinical symptoms, quality of life and work productivity among patients in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:514–521. doi: 10.1111/ced.12841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Final Report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421. [PubMed]

- 18.Miot H.A. Assessing normality of data in clinical and experimental trials. J Vasc Bras. 2017;16:88–91. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Figueiredo Filho D.B., Silva Júnior J.A. Visão além do alcance: uma introdução à análise fatorial. Opinião Pública. 2010;16:160–185. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norman G.R., Streiner D.L. 4th ed. People's Medical Publishing House; Connecticut: 2014. Biostatistics: the bare essentials. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sourial N., Wolfson C., Zhu B., Quail J., Fletcher J., Karunananthan S. Correspondence analysis is a useful tool to uncover the relationships among categorical variables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:638–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miot H.A. Tamanho da amostra em estudos clínicos e experimentais. J Vasc Bras. 2011;10:275–278. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fabiani R., Naldini G., Chiavarini M. Dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome in adult subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2019;11:E2056. doi: 10.3390/nu11092056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattei J., Malik V., Wedick N.M., Hu F.B., Spiegelman D., Willett W.C. Reducing the global burden of type 2 diabetes by improving the quality of staple foods: The Global Nutrition and Epidemiologic Transition Initiative. Global Health. 2015;11:23. doi: 10.1186/s12992-015-0109-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popkin B.M., Reardon T. Obesity and the food system transformation in Latin America. Obes Rev. 2018;19:1028–1064. doi: 10.1111/obr.12694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.IBGE. Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2008-2009 – Despesas, Rendimentos e Condições de Vida. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2010.

- 27.Hassannejad R., Kazemi I., Sadeghi M., Mohammadifard N., Roohafza H., Sarrafzadegan N. Longitudinal association of metabolic syndrome and dietary patterns: a 13-year prospective population-based cohort study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;4:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2017.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bray G.A., Heisel W.E., Afshin A., Jensen M.D., Dietz W.H., Long M. The science of obesity management: an endocrine society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2018;2:79–132. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin A., Booth J.N., Laird Y., Sproule J., Reilly J.J., Saunders D.H. Physical activity, diet and other behavioural interventions for improving cognition and school achievement in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Group. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2018:CD009728. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009728.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen P., Christensen R., Zachariae C., Geiker N.R., Schaadt B.K., Stender S. Long-term effects of weight reduction on the severity of psoriasis in a cohort derived from a randomized trial: a prospective observational follow-up study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:259–265. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.125849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yousefzadeh H., Mahmoudi M., Banihashemi M., Rastin M., Azad F.J. Investigation of dietary supplements prevalence as complementary therapy: comparison between hospitalized psoriasis patients and non-psoriasis patients, correlation with disease severity and quality of life. Complement Ther Med. 2017;33:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rucević I., Perl A., Barisić-Drusko V., Adam-Perl M. The role of the low energy diet in psoriasis vulgaris treatment. Coll Antropol. 2003;27(Suppl. 1):41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gisondi P., Del Giglio M., Di Francesco V., Zamboni M., Girolomoni G. Weight loss improves the response of obese patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis to low-dose cyclosporine therapy: a randomized, controlled, investigator-blinded clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1242–1247. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen P., Zachariae C., Christensen R., Geiker N.R., Schaadt B.K., Stender S. Effect of weight loss on the severity of psoriasis: a randomized clinical study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;7:795–801. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sköldstam L., Hagfors L., Johansson G. An experimental study of a Mediterranean diet intervention for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:208–214. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.3.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown A.C., Hairfield M., Richards D.G., McMillin D.L., Mein E.A., Nelson C.D. Medical nutrition therapy as a potential complementary treatment for psoriasis – five case reports. Altern Med Rev. 2004;3:297–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaparro M.P., Pina M.F., de Oliveira Cardoso L., Santos S.M., Barreto S.M., Giatti Gonçalves L. The association between the neighbourhood social environment and obesity in Brazil: a cross-sectional analysis of the ELSA-Brasil study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e016800. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malta D.C., Silva A.G., Tonaco L.A.B., Freitas M.I.F., Velasquez-Melendez G. Time trends in morbid obesity prevalence in the Brazilian adult population from 2006 to 2017. Cad Saúde Pública. 2019;35:223–518. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00223518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martins-Silva T., Vaz J.S., de Mola C.L., Assunção M.C.F., Tovo-Rodrigues L. Prevalence of obesity in rural and urban areas in Brazil: National Health Survey, 2013. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2019;22:190049. doi: 10.1590/1980-549720190049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahil S.K., McSweeney S.M., Kloczko E., McGowan B., Barker J.N., Smith C.H. Does weight loss reduce the severity and incidence of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis? A critically appraised topic. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:946–953. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eder L., Widdifield J., Rosen C.F., Cook R., Lee K.A., Alhusayen R. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in Ontario, Canada: a population-based study. Arthritis Care Res (Honoken) 2019;71:1084–1091. doi: 10.1002/acr.23743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrándiz C., Carrascosa J.M., Toro M. Prevalence of psoriasis in Spain in the age of biologics. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;5:504–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rastmanesh R. Psoriasis and vegetarian diets: a role for cortisol and potassium? Med Hypotheses. 2009;3:368. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Unger A.L., Torres-Gonzalez M., Kraft J. Dairy fat consumption and the risk of metabolic syndrome: an examination of the saturated fatty acids in dairy. Nutrients. 2019;12 doi: 10.3390/nu11092200. pii:E2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Medawar E., Huhn S., Villringer A., Witte A.V. The effects of plant-based diets on the body and the brain: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;1:226. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0552-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chi C.C., Ko S.H., Yeh M.L., Wang S.H., Tsai Y.S., Hsu M.Y. Lifestyle changes for treating psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;11:CD011972. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011972.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zmora N., Suez J., Elinav E. You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:35–56. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]