Abstract

Genetically encoded voltage indicators (GEVIs) continue to evolve, resulting in many different probes with varying strengths and weaknesses. Developers of new GEVIs tend to highlight their positive features. A recent article from an independent laboratory has compared the signal/noise ratios of a number of GEVIs. Such a comparison can be helpful to investigators eager to try to image the voltage of excitable cells. In this perspective, we will present examples of how the biophysical features of GEVIs affect the imaging of excitable cells in an effort to assist researchers when considering probes for their specific needs.

Significance

In this perspective, we explore the biophysical characteristics of genetically encoded voltage indicators and their consequences on voltage imaging.

Main Text

Challenges for imaging voltage

The optical voltage signal is limited to the plasma membrane, which constrains the amount of probe responding to membrane potential transients (1). Erroneous membrane trafficking contributes a nonresponsive background fluorescence, further reducing the signal/noise ratio (SNR) (2). Other challenges come from the changes in membrane potentials associated with suprathreshold and subthreshold neuronal activities (3). A genetically encoded voltage indicator (GEVI) must sufficiently alter its fluorescence in 0.5–2 ms to resolve action potentials. For synaptic potentials, the probe needs to be able to respond to small changes in membrane potential (under 10 mV). Given these challenges, it is imperative that investigators appreciate the optical characteristics of a GEVI when determining which probe to use.

Optical properties of GEVIs

Fluorescence

Every functional characteristic of a GEVI is dependent upon its brightness. The fluorescence intensity of a GEVI is a product of how well it absorbs photons (the extinction coefficient) and what fraction of the absorbed light is emitted (the quantum yield). These two parameters determine the brightness, often referred to as resting fluorescence (F0). Given that most of the parameters reported for GEVIs are a percentage of F0, this value is extremely important for comparing different GEVIs.

Dynamic fluorescence change

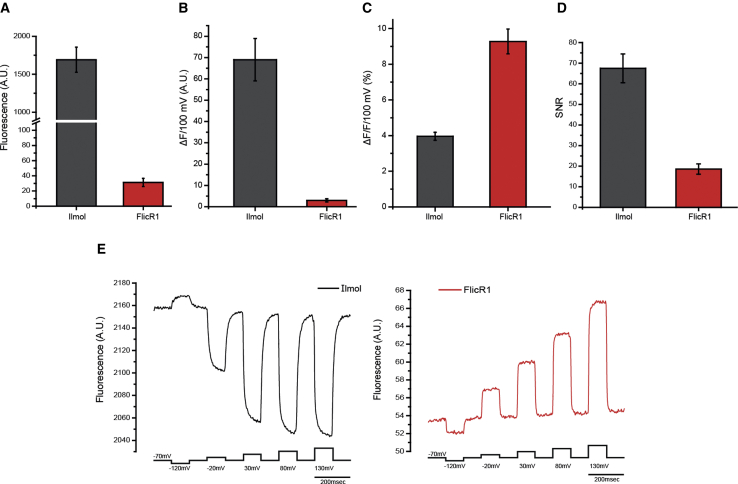

The dynamic fluorescence change is the alteration of the fluorescence output of the GEVI in response to changes in membrane potential. A commonly reported parameter is ΔF/F0/100 mV (100 mV is roughly equivalent to the size of an action potential in mammalian neurons). Without knowing F0, this value is meaningless. Because the fractional change is a function of F0, one can be fooled into thinking that a probe with a 60% ΔF/F0/100 mV signal is better than a probe with a 30% signal. However, if the 30% signal comes from a probe that is 10-fold brighter, then a much larger change in the number of photons will be detected. The number of photons is important because shot noise is defined as /, where is the number of photons. Increasing therefore improves the SNR. Compare, for example, the GEVIs Ilmol (4) and FlicR1 (5), which are both red-shifted GEVIs. Ilmol yields only a 4% ΔF/F0/100 mV change when expressed in HEK cells, whereas FlicR1 has a larger fluorescence fractional change of 10% ΔF/F0/100 mV (4,5). However, Ilmol is more than 10-fold brighter than FlicR1, resulting in a threefold improvement in the SNR (Fig. 1). The improved SNR for Ilmol does not necessarily mean that it is always a better probe than FlicR1. Ilmol gets dimmer when the plasma membrane is depolarized, whereas FlicR1 gets brighter. In some circumstances, an increase in the fluorescence output may offset the reduced SNR (see Optical Considerations below).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the GEVIs Ilmol and FlicR1. (A) Shown is the fluorescence of HEK 293 cells expressing Ilmol or FlicR1. (B) The fluorescence change for Ilmol and FlicR1 for a 100 mV depolarization step of the plasma membrane is shown. (C) The fractional fluorescence change for Ilmol and FlicR1 for a 100 mV depolarization step is shown. (D) A signal-to-noise comparison of Ilmol to FlicR1 is shown. (E) Representative fluorescence traces for Ilmol (black) and FlicR1 (red) are shown (modified from Yi et al. (4)). To see this figure in color, go online.

Kinetics

The time constant, τ, is the response time required for the GEVI to reach 63% of the maximal fluorescence change. τon refers to the time constant at the onset of the voltage step, and τoff represents the time constant during the recovery. A GEVI with a τon of 2 ms and a dynamic change of 10% for a 100-mV step will exhibit a fluorescence change of ∼6% at 2 ms (roughly the time span for an action potential). A probe with a τon of 10 ms and a 40% dynamic change would yield an ∼7% fluorescence change for an action potential (see table in Yi et al. (4)). Faster does not necessarily mean better. A slower probe with a larger ΔF may be better at reporting action potentials because of the larger difference in photons emitted, which improves the SNR.

Two GEVIs have greatly influenced the current state of the field. ArcLight resulted from a spontaneous mutation to the fluorescent protein, Super Ecliptic pHluorin, which yielded a 40% ΔF/F0/100 mV in HEK cells (6, 7, 8). The other is Arch, a GEVI that utilizes bacterial rhodopsin to optically report membrane potential in mammalian cells (9). Arch exhibited sub-millisecond time constants, and the onset of ArcLight’s optical signal had a fast component of 10 ms (the optical trace was best fit by a double exponential decay). Arch also exhibited a ΔF/F0/100 mV that was greater than 60% but was >100 times dimmer than ArcLight. Despite these differences, both ArcLight and Arch could optically resolve action potentials. The brighter fluorescence of ArcLight has enabled its use in many in vivo models (10, 11, 12, 13). Brighter versions of Arch have also been used in vivo, but they still require strong illumination intensities because they are at least one order of magnitude dimmer than ArcLight (14, 15, 16, 17).

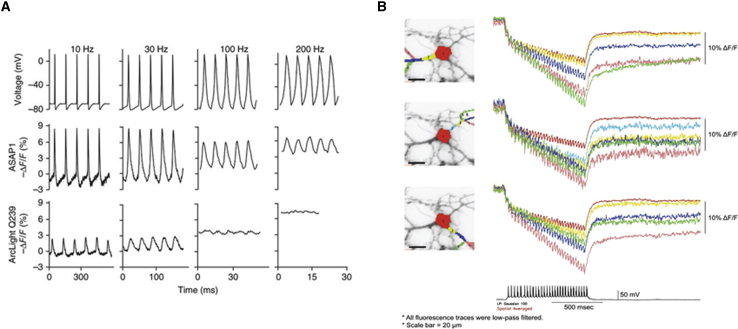

The likelihood of a second voltage event occurring before the fluorescence returns to baseline is increased for slower-responding probes, resulting in a temporal binning of the fluorescence change. Two examples are shown in Fig. 2. The first example is the GEVI ASAP1 (18). ASAP1 consists of a circularly permuted FP fused in the loop between the transmembrane segments 3 and 4 in the voltage-sensing domain of the voltage-sensing phosphatase from chicken. In Fig. 2 A, HEK cells expressing ASAP1 were voltage clamped and subjected to simulated action potentials with increasing frequencies. As the frequency of the action potentials increased, the fluorescence did not return to baseline, thereby diminishing the net fluorescence change for each spike. Despite the decrease in fluorescence change, ASAP1 could still optically report voltage events at 100 Hz (Fig. 2 A). The second example comes from ArcLight, which is slower (6). When exposed to higher frequencies, the optical response fuses (Fig. 2 A). However, ArcLight is still capable of resolving action potentials firing around 30 Hz from different regions of a neuron (Fig. 2 B; (19)). It should also be noted that slower probes will temporally distort the waveform of the action potentials. The width at the half-peak maximum will increase depending on the speed of the sensor.

Figure 2.

High-frequency spiking results in a reduction of the voltage-dependent optical signal. (A) ASAP1 and ArcLight expressed in HEK 293 cells experiencing simulated action potentials at 10, 30, 100, and 200 Hz via whole-cell voltage clamp are shown (modified from St-Pierre et al. (18)). (B) ArcLight expressed in a hippocampal neuron responding to action potentials from different regions of the cell are shown (modified from Kang et al. (19)).

Voltage range

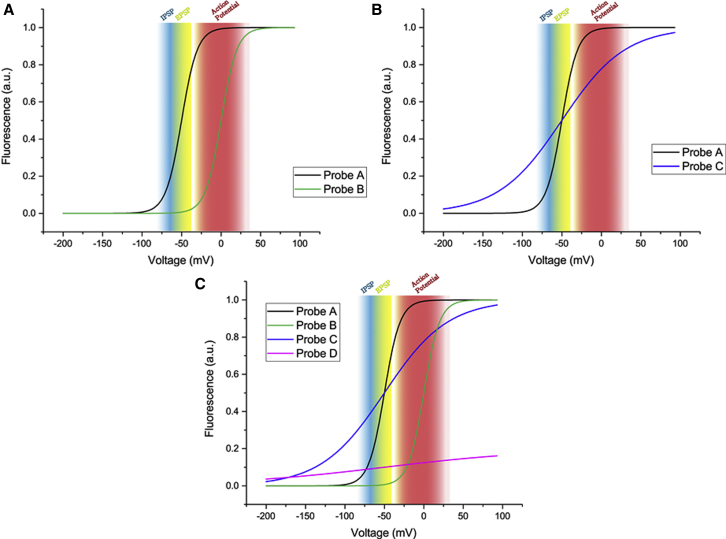

The voltage range is an often overlooked characteristic of a GEVI (3). The V1/2 of a GEVI is the voltage at which the probe reaches 50% of the total fluorescence change. A GEVI with a V1/2 near −50 mV will have a larger fractional change in fluorescence during synaptic subthreshold activity than a GEVI with a V1/2 near 0 mV (Fig. 3 A). In contrast, distinguishing action potentials from synaptic activity may be more difficult for the GEVI with the V1/2 at −50 mV because nearly half of the fluorescence response has already occurred during the subthreshold voltage change.

Figure 3.

Theoretical voltage ranges. (A) Two GEVIs differing in V1/2 are shown. Probe A has a V1/2 of −50 mV. Probe B has a V1/2 of 0 mV. Color-coding refers to IPSPs (blue), EPSPs (yellow), and action potential ranges (red). Probe A could respond to IPSP, EPSPs, and action potentials, whereas probe B would only be able to respond to action potentials. (B) Two GEVIs having an identical V1/2 (−50 mV) but with differing slopes are shown. (C) A comparison of probes A, B, and C with probe D, which is roughly fivefold dimmer, is shown.

The V1/2 is only part of the story. The total range of the voltage response is also dependent upon the slope of the fluorescence change as a function of voltage. The rhodopsin-based GEVIs exhibit a near-linear voltage response (9,15,20, 21, 22). Other GEVIs exhibit a sigmoidal fluorescence change as a function of voltage (4,6,23, 24, 25, 26). A linear slope will spread the dynamic fluorescence change over a broad voltage range. A sigmoidal response has the potential to focus the optical response to a narrow voltage range (Fig. 3 A). If the goal is to detect all types of activity, then a linear slope or a shallow sigmoidal response might be desired. If the goal is to detect specific types of activity, especially in vivo, then a sigmoidal response with a steep slope might be better (Fig. 3 B).

To further illustrate the effect of fluorescence intensity, Fig. 3 C also includes a probe that is fivefold dimmer. One can see that the relative fluorescence change for such a probe would be much less. The dimmer fluorescence intensity can be overcome by increasing the illumination power during the optical recording. For instance, imaging of mouse nodose ganglia using QuasAr2 used 300 W/cm2 excitation intensity (15) compared with 500 mW/cm2 for the GEVI Ilmol when imaging hippocampal brain slices (4). However, care must be taken when using high-intensity illumination (see Drawbacks below).

Optical considerations

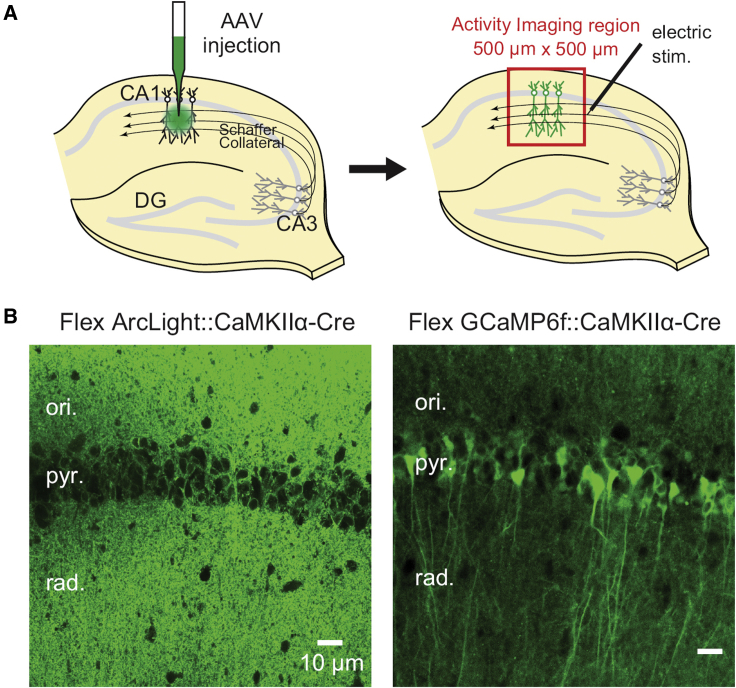

The experimenter must also take into account the preparation that is being imaged. Voltage imaging is much different than calcium imaging. Voltage transients occur at the plasma membrane, whereas calcium transients are intracellular. Targeting the probe to the plasma membrane rather than the cytoplasm can alter the fluorescent architecture of a sample (Fig. 4; (27)). For the calcium probe, the fluorescence is primarily in the soma, with some fluorescence detected in the processes. In this example, the voltage probe is a near-negative image from that seen for calcium probes. The processes are well labeled, whereas the soma is relatively faint.

Figure 4.

GEVI expression compared with GECI expression. (A) An AAV for the GEVI ArcLight or the GECI GCaMP6f is injected into the CA1 region of the mouse hippocampus. (B) Fluorescence of ArcLight is primarily in the oriens and radiatum layers because the surface area of the plasma membrane is far greater in the processes than the soma (pyramidal layer). Conversely, the calcium indicator GCaMP6f is primarily in the soma because the sensor resides in the cytoplasm. This figure was modified from Nakajima and Baker (27). To see this figure in color, go online.

Polarity of the optical signal

Many GEVIs get fainter when the plasma membrane is depolarized. Typical expression patterns like those shown in Fig. 4 generate a high fluorescent background from which individual cell activities can be difficult to resolve. For this reason, engineering a GEVI that starts dim and gets brighter, such as FlicR1 or Marina, could improve the contrast for population recordings in slice or in vivo (5,28). However, although it would be easier to detect depolarization events with such a probe, identifying inhibitory responses would become more difficult because a dim probe would get dimmer upon hyperpolarization of the plasma membrane.

Sparse labeling and subcellular expression restrictions

A few strategies have been employed to reduce the fluorescent background for population imaging in slice and in vivo. The first is sparse labeling by titrating the expression of the GEVI via injection of two viral constructs. One viral construct is a floxed version of the gene of interest, whereas the second virus contains the CRE recombinase gene (29). Another approach is to limit expression of the GEVI to the soma using a targeting motif from the voltage-gated potassium channel, Kv2.1 (30,31). Yet another strategy is to only illuminate the soma, which requires advanced optical tools but limits the number of cells that can be imaged simultaneously (17). Although these methods will reduce the background fluorescence, they also sacrifice information because the entire neuron is no longer fluorescent or only a small subset of neurons are fluorescent.

Two-photon imaging

Two-photon imaging enables access to deeper areas and optical sectioning of the tissue. The sampling rate for two-photon microscopy can now be in the millisecond time frame (32). Unfortunately, no effort has been made to specifically engineer a two-photon GEVI. Every GEVI reported to date has been the product of a one-photon screen. The results for two-photon imaging of GEVIs have therefore been somewhat variable. Whereas the ArcLight and ASAP families of GEVIs yield good two-photon signals, rhodopsin-based GEVIs give little to no voltage-dependent optical signals upon two-photon illumination (Fig. 5; (32)).

Figure 5.

Comparison of two-photon recordings of various GEVIs in Drosophila. (A) A schematic of the experimental setup is shown. (B) Recordings from medulla region of L2 neuron terminals expressing ASAP1, ASAP2, ArcLight, MacQ-mCitrine, Ace2N-2AA-mNeon, or GCaMP6f. The flies were exposed to 300 ms of dark (black bar) followed by 300 ms of light flashes (white bar). This figure was modified from Chamberland et al. (32). To see this figure in color, go online.

Spike detection fidelity, d′, versus SNR

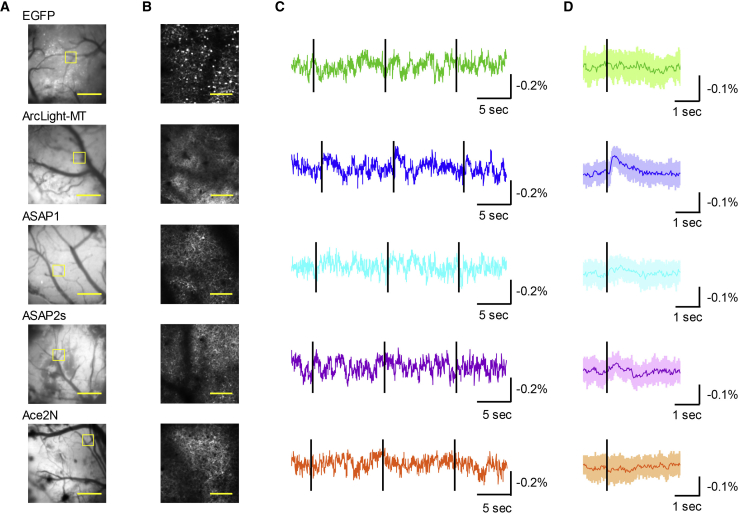

With so many parameters contributing to the voltage-dependent optical signal, it is difficult to determine which GEVI to use. The spike detection fidelity, d′ (33), attempts to compare GEVIs based on “a neuron’s experimentally determined fluorescence baseline, the peak ΔF/F response to a spike, and the temporal duration of the sensor’s response to a spike” (20). Gong et al. suggest that d′ is a more realistic measure of spike detection fidelity than SNR measurements. However, there are issues with using d′ to compare GEVIs. For one, there is more to voltage imaging than measuring spikes. The most severe issue is that d′ has been a poor predictor of success. A recent independent comparison of the GEVIs ArcLight (6), ASAP1 (18), ASAP2s (32), and Ace2N (21) expressed in the mouse visual cortex showed that only ArcLight could consistently report neuronal responses for one-photon wide-field imaging in vivo despite Ace2N having a 10-fold-better d′ value than ArcLight (Fig. 6; (34)). ArcLight was also better at two-photon in vivo imaging, which is not surprising because opsin-based probes yield poor two-photon signals (Figs. 5 and 6).

Figure 6.

Comparison of different GEVI responses in the mouse visual cortex. (A) Images of the primary visual cortex expressing the fluorescent protein as labeled are shown. Scale bars, 1 mm. (B) Two-photon images of the areas shown in the yellow box in (A) are shown. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C) Representative single trials with the black line representing the presentation of the visual stimulus for 10 ms. (D) The averages of 10 trials from (C) are shown. The dark colored line is the mean. The shaded area is the standard error of the mean. This figure was modified from Bando et al. (34). To see this figure in color, go online.

Drawbacks

Every GEVI has some unwanted characteristic. ArcLight-derived probes are pH sensitive (6,35). The pH response has a minimal effect on the voltage imaging (19) but may complicate slow, subthreshold events in population recordings. It is advisable to implement a pH-sensitive FP-only control to validate that the optical response is due to voltage. Opsin-based GEVIs can have light-induced currents (16,20) and chromogenic behavior (illumination with other wavelengths disturbs the fluorescence output of the GEVI) (15,16). Some opsin-based probes also require intense illumination. The recently described paQuasAr3 exploits its chromogenic nature by coexcitation with 488 nm (100 mW/mm2) and 640 nm (10 W/mm2) wavelengths. That much light will heat the sample, which has been shown to have variable physiological effects depending on the cell type being illuminated (36). For a list of the illuminations used for different GEVIs, see the excellent review by Bando et al. (37).

Phototoxicity and photobleaching

In an excited state, a fluorophore can degrade via an interaction with oxygen, resulting in photobleaching. This process also produces reactive oxygen species, such as superoxide radicals, that can damage cells, resulting in phototoxicity. Though related, photobleaching and phototoxicity are not necessarily linked. One can occur without the other. For instance, cells possess antioxidants that can prevent phototoxicity but may not prevent the degradation of the fluorophore. See the fine review by Icha et al. (38). One should also be aware that the exogenous fluorophore (GEVI) is not the only contributor to phototoxicity. Endogenous molecules such as flavins can also generate free oxygen radicals, so any illumination regardless of the GEVI being used can potentially result in photoxicity, which is another reason to limit the intensity/time of illumination.

The trend is toward brighter

As discussed above, the brightness of the GEVI is critical. Recent advancements in the opsin-based GEVIs have all involved making the probe brighter (16,17,21,39,40). A new GEVI, Voltron, combines the speed of the opsin reporters with the ability to bind a synthetic fluorescent dye, which vastly improves the brightness of the probe (40). It is too early to tell whether the need to add a second component will complicate the use of Voltron, but more photons improves the potential to increase the SNR. FRET-based probes may also make a comeback because ratiometric measurements would reduce motion artifacts such as respiration during in vivo recordings (25,41).

Internal membranes

In addition to elucidating the functions of neural networks, GEVIs may also help resolve the internal workings of a cell. The ability to fluorescently tag internal cellular structures has demonstrated interplay between organelles that appears to have physiological consequences. We recently reported a voltage transient in the endoplasmic reticulum (42). The role of that internal voltage transient remains uncertain, but it is clear that internal membranes can experience changes in membrane potential. Efforts are underway to develop GEVIs that specifically label distinct organelles, i.e., mitochondria, and image the response during environmental stress.

Conclusion

There is no perfect GEVI. Although many have been shown to yield signals in vivo, the investigator needs to consider the type of signal desired (population versus single-cell recordings), the voltage range to be investigated (e.g., synaptic inputs from dendrites or action potentials along the axon), the light source required for imaging, and the speed of the detection device being used. Although these signals can be informative, the brightness and signal size of these sensors need to improve to provide the spatial and temporal resolution of voltage changes in neural networks. Until then, it is our hope that the examples provided here give researchers better insights into which GEVIs, if any, are appropriate for their experimental needs.

Author Contributions

J.K.R. wrote the manuscript and assisted with figures. L.M.L. wrote the manuscript and assisted with figures. M.S.I.M. assisted with figures. B.E.K. wrote the manuscript and assisted with figures. S.L. wrote the manuscript. L.B.-B. assisted with manuscript content and figures. B.J.B. wrote the manuscript and assisted with figures.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lawrence Cohen for the critical review of the manuscript. B.J.B. was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders And Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under award number U01NS099691. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This report was also funded by the Korea Institute of Science and Technology grants 2E26190, 2E26170, 2E30070.

Editor: Brian Salzberg.

References

- 1.Storace D., Sepehri Rad M., Baker B.J. Toward better genetically encoded sensors of membrane potential. Trends Neurosci. 2016;39:277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker B.J., Lee H., Kosmidis E.K. Three fluorescent protein voltage sensors exhibit low plasma membrane expression in mammalian cells. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2007;161:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakajima R., Jung A., Baker B.J. Optogenetic monitoring of synaptic activity with genetically encoded voltage indicators. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2016;8:22. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2016.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yi B., Kang B.E., Baker B.J. A dimeric fluorescent protein yields a bright, red-shifted GEVI capable of population signals in brain slice. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:15199. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33297-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdelfattah A.S., Farhi S.L., Campbell R.E. A bright and fast red fluorescent protein voltage indicator that reports neuronal activity in organotypic brain slices. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:2458–2472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3484-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin L., Han Z., Pieribone V.A. Single action potentials and subthreshold electrical events imaged in neurons with a fluorescent protein voltage probe. Neuron. 2012;75:779–785. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han Z., Jin L., Pieribone V.A. Mechanistic studies of the genetically encoded fluorescent protein voltage probe ArcLight. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han Z., Jin L., Pieribone V.A. Fluorescent protein voltage probes derived from ArcLight that respond to membrane voltage changes with fast kinetics. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kralj J.M., Douglass A.D., Cohen A.E. Optical recording of action potentials in mammalian neurons using a microbial rhodopsin. Nat. Methods. 2011;9:90–95. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Storace D.A., Braubach O.R., Sung U. Monitoring brain activity with protein voltage and calcium sensors. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:10212. doi: 10.1038/srep10212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Storace D.A., Cohen L.B. Measuring the olfactory bulb input-output transformation reveals a contribution to the perception of odorant concentration invariance. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:81. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00036-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borden P.Y., Ortiz A.D., Stanley G.B. Genetically expressed voltage sensor ArcLight for imaging large scale cortical activity in the anesthetized and awake mouse. Neurophotonics. 2017;4:031212. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.4.3.031212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao G., Platisa J., Nitabach M.N. Genetically targeted optical electrophysiology in intact neural circuits. Cell. 2013;154:904–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochbaum D.R., Zhao Y., Cohen A.E. All-optical electrophysiology in mammalian neurons using engineered microbial rhodopsins. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:825–833. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lou S., Adam Y., Cohen A.E. Genetically targeted all-optical electrophysiology with a transgenic Cre-dependent optopatch mouse. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:11059–11073. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1582-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piatkevich K.D., Jung E.E., Boyden E.S. A robotic multidimensional directed evolution approach applied to fluorescent voltage reporters. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018;14:352–360. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adam Y., Kim J.J., Cohen A.E. Voltage imaging and optogenetics reveal behaviour-dependent changes in hippocampal dynamics. Nature. 2019;569:413–417. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1166-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.St-Pierre F., Marshall J.D., Lin M.Z. High-fidelity optical reporting of neuronal electrical activity with an ultrafast fluorescent voltage sensor. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17:884–889. doi: 10.1038/nn.3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang B.E., Lee S., Baker B.J. Optical consequences of a genetically-encoded voltage indicator with a pH sensitive fluorescent protein. Neurosci. Res. 2019;146:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong Y., Wagner M.J., Schnitzer M.J. Imaging neural spiking in brain tissue using FRET-opsin protein voltage sensors. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3674. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gong Y., Huang C., Schnitzer M.J. High-speed recording of neural spikes in awake mice and flies with a fluorescent voltage sensor. Science. 2015;350:1361–1366. doi: 10.1126/science.aab0810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kannan M., Vasan G., Pieribone V.A. Fast, in vivo voltage imaging using a red fluorescent indicator. Nat. Methods. 2018;15:1108–1116. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0188-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piao H.H., Rajakumar D., Baker B.J. Combinatorial mutagenesis of the voltage-sensing domain enables the optical resolution of action potentials firing at 60 Hz by a genetically encoded fluorescent sensor of membrane potential. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:372–385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3008-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S., Piao H.H., Baker B.J. Imaging membrane potential with two types of genetically encoded fluorescent voltage sensors. J. Vis. Exp. 2016:e53566. doi: 10.3791/53566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akemann W., Mutoh H., Knöpfel T. Imaging neural circuit dynamics with a voltage-sensitive fluorescent protein. J. Neurophysiol. 2012;108:2323–2337. doi: 10.1152/jn.00452.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dimitrov D., He Y., Knöpfel T. Engineering and characterization of an enhanced fluorescent protein voltage sensor. PLoS One. 2007;2:e440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakajima R., Baker B.J. Mapping of excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials of neuronal populations in hippocampal slices using the GEVI, ArcLight. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018;51:504003. doi: 10.1088/1361-6463/aae2e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Platisa J., Vasan G., Pieribone V.A. Directed evolution of key residues in fluorescent protein inverses the polarity of voltage sensitivity in the genetically encoded indicator ArcLight. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017;8:513–523. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song C., Do Q.B., Knöpfel T. Transgenic strategies for sparse but strong expression of genetically encoded voltage and calcium indicators. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1461. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim S.T., Antonucci D.E., Trimmer J.S. A novel targeting signal for proximal clustering of the Kv2.1 K+ channel in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2000;25:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80902-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piatkevich K.D., Bensussen S., Han X. Population imaging of neural activity in awake behaving mice. Nature. 2019;574:413–417. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1641-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chamberland S., Yang H.H., St-Pierre F. Fast two-photon imaging of subcellular voltage dynamics in neuronal tissue with genetically encoded indicators. eLife. 2017;6:e25690. doi: 10.7554/eLife.25690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilt B.A., Fitzgerald J.E., Schnitzer M.J. Photon shot noise limits on optical detection of neuronal spikes and estimation of spike timing. Biophys. J. 2013;104:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bando Y., Sakamoto M., Yuste R. Comparative evaluation of genetically encoded voltage indicators. Cell Rep. 2019;26:802–813.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang B.E., Baker B.J. Pado, a fluorescent protein with proton channel activity can optically monitor membrane potential, intracellular pH, and map gap junctions. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:23865. doi: 10.1038/srep23865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owen S.F., Liu M.H., Kreitzer A.C. Thermal constraints on in vivo optogenetic manipulations. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:1061–1065. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0422-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bando Y., Grimm C., Yuste R. Genetic voltage indicators. BMC Biol. 2019;17:71. doi: 10.1186/s12915-019-0682-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Icha J., Weber M., Norden C. Phototoxicity in live fluorescence microscopy, and how to avoid it. BioEssays. 2017;39 doi: 10.1002/bies.201700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zou P., Zhao Y., Cohen A.E. Bright and fast multicoloured voltage reporters via electrochromic FRET. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4625. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abdelfattah A.S., Kawashima T., Schreiter E.R. Bright and photostable chemigenetic indicators for extended in vivo voltage imaging. Science. 2019;365:699–704. doi: 10.1126/science.aav6416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carandini M., Shimaoka D., Knöpfel T. Imaging the awake visual cortex with a genetically encoded voltage indicator. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:53–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0594-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sepehri Rad M., Cohen L.B., Baker B.J. Monitoring voltage fluctuations of intracellular membranes. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:6911. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25083-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]