Abstract

Planar pore-spanning membranes (PSMs) have been shown to be a versatile tool to resolve elementary steps of the neuronal fusion process. However, in previous studies, we monitored only lipid mixing between fusing large unilamellar vesicles and PSMs and did not gather information about the formation of fusion pores. To address this important step of the fusion process, we entrapped sulforhodamine B at self-quenching concentrations into large unilamellar vesicles containing the v-SNARE synaptobrevin 2, which were docked and fused with lipid-labeled PSMs containing the t-SNARE acceptor complex ΔN49 prepared on gold-coated porous silicon substrates. By dual-color spinning disk fluorescence microscopy with a time resolution of ∼20 ms, we could unambiguously distinguish between bursting vesicles, which was only rarely observed (<0.01%), and fusion pore formation. From the time-resolved dual-color fluorescence time traces, we were able to identify different fusion pathways, including remaining three-dimensional postfusion structures with released content and transient openings and closings of the fusion pores. Our results on fusion pore formation and lipid diffusion from the PSM into the fusing vesicle let us conclude that the content release, i.e., fusion pore formation after the merger of the two lipid membranes occurs almost simultaneously.

Significance

Despite great efforts to develop in vitro fusion assays to understand the process of neuronal fusion, there is still a huge demand for single-vesicle fusion assays that simultaneously report on intermediate states, including three-dimensional postfusion structures and dynamic openings and closings of the fusion pore. Here, we show that pore-spanning membranes are ideal candidates to fulfill these demands. Owing to their planarity and the second aqueous compartments, they are readily accessible by fluorescence microscopy and provide sufficient space underneath the membrane for the released vesicle content. Dual-color fluorescence microscopy allows distinguishing between different fusion intermediates and fusion pathways such as direct full content release or a stepwise release from one vesicle.

Introduction

SNARE-mediated membrane fusion has been established as one of the key steps in neuronal signal transmission. It is well accepted that SNAREs are the engine of the fusion machinery (1, 2, 3). The highly exergonic nature of the SNARE-assembly forming a complex provides the required energy to overcome the barrier—or even several barriers dependent on the intermediate states—from a docked vesicle to two fully fused membranes (4). The critical and most important step for neurotransmitter transfer from the synaptic vesicle into the presynaptic cleft is the creation of a fusion pore that allows the content to be released (5). Exocytic fusion pores have been shown to be highly dynamic and they determine the amount, size, and the kinetics of cargo release with important consequences for downstream events (6, 7, 8).

To elucidate the process of neuronal fusion with a focus on fusion pore formation, in vitro systems are highly desirable. Several in vitro assays have been developed over the past two decades (9,10). Bulk fusion assays based on lipid mixing (11,12) combined with content mixing (12) are frequently used to measure fusion efficiencies as well as kinetics (13). With the help of electron microscopy and fluorescence cross correlation spectroscopy, even intermediate states could be identified (14) in vesicle populations. However, observation of SNARE-driven fusion at the single-vesicle level has the great potential to readily dissect and characterize fusion intermediates as well as their lifetimes and kinetics by means of fluorescence microscopy. Based on two vesicle populations in which one population is immobilized on a support, Yoon et al. (15) analyzed SNARE-mediated fusion with a fluorescence-based lipid mixing assay. However, taking content mixing into account showed that efficient full fusion including pore formation, and expansion required synaptotagmin 1 and Ca2+ in this assay system (16,17).

To resemble the geometry of the planar presynaptic target membrane on one side and the vesicular membrane on the other side, supported lipid bilayers combined with fluorescence microscopy techniques such as total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy have been developed. To produce supported lipid bilayers, most research groups have employed the direct vesicle fusion method. However, the initial attempts of single-vesicle fusion to planar-supported bilayers resulted in SNAP25-independent fusion reactions (18,19), were Ca2+-dependent even though the system lacked synaptotagmin (20), or resulted in vesicle rupture instead of membrane fusion (21). One aspect that might explain these observations is the reduced mobility of the membrane components attached to the support (22). To increase the membrane-support distance, Karatekin and co-workers produced planar membranes via direct vesicle fusion and included a polymer cushion (23,24). In contrast to the direct vesicle fusion method, Tamm and co-workers introduced in their seminal work a two-step Langmuir-Blodgett/vesicle fusion approach to generate SNARE-containing lipid bilayers (25,26). With this assay, the group was able to show that the fusion kinetics strongly depend on the lipid environment (27). Later on, they were extended their system to the observation of content transfer from the vesicle—in which water-soluble dyes were entrapped—to the small cleft between the substrate and the supported membrane (28). Again, the lipid composition, i.e., the cholesterol content in either the supported membrane or the vesicle membrane was a critical parameter to shift between hemifusion states and full fusion (29). The group also showed that larger proteins entrapped in dense core vesicles can be released (22,30). Based on the cushioned planar bilayers in a microfluidic flow cell, Stratton et al. (31) similarly found that cholesterol increases the openness of SNARE-mediated flickering fusion pores.

In all these membrane systems, the aqueous space underneath the planar membrane is very small. An alternative membrane system, in which larger second aqueous compartments are provided that can take up the vesicle’s content, are pore-spanning membranes (PSMs) (32,33). In previous studies, we and others have shown that this model membrane is suited to investigate SNARE-mediated fusion on the single-vesicle level (32,34, 35, 36). Based on a fluorescent readout, we were able to observe the diffusion of docked vesicles as well as lipid mixing between the fusing vesicle and the planar PSM providing information about intermediate states in a time-resolved manner (32,34,35).

Here, we asked the question, whether PSMs allow us to observe content release (fusion pore formation) during the fusion process in a time-resolved manner. To address this question, we generated fluorescently labeled PSMs containing the t-SNARE acceptor complex ΔN49 on porous substrates, to which synaptobrevin-2 (syb 2)-doped large unilamellar vesicles entrapping a water-soluble dye at self-quenching concentrations were added. Dual-color spinning disk fluorescence microscopy was used to monitor the docking and fusion of individual vesicles with a temporal resolution of ∼20 ms. The porous mesh allowed us to directly observe the dye transfer into the underlying aqueous compartments. Simultaneously, we were able to measure lipid mixing, enabling us to visualize different fusion pathways based on the interplay of fusion pore formation and the lipid diffusion from the PSM into the fusing vesicle.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Porous SiO2/Si3N4 substrates with a pore diameter of 1.2 and 5.0 μm were purchased from Aquamarijn (Zutphen, the Netherlands). 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (POPS), and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE) were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Cholesterol, sulforhodamine B acid chloride (SRB) and 6-mercapto-1-hexanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany). Atto488 maleimide and Atto655/488/390-1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (Atto655/488/390 DPPE) were from Atto-Tec (Siegen, Germany).

Protein expression, isolation, and labeling

Expression and purification of the SNAREs was performed according to a protocol described previously (14,37). Briefly, recombinant expression of the t-SNAREs syntaxin 1A (amino acids (aa) 183–288), SNAP25a (aa 1–206 with all cysteine residues replaced by serine), the synaptobrevin 2 fragments (aa 1–96, aa 49–96, aa 49–96 S79C), and full-length synaptobrevin 2 (aa 1–116) originating from Rattus norvegicus was performed using transformed Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells carrying a pET28a vector. As all proteins are equipped with a His6-tag, purification was achieved using Ni2+-NTA agarose affinity chromatography, thrombin cleavage of the His6-tag overnight and final ion exchange chromatography with a MonoQ or MonoS column (Äkta purifying system; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Synaptobrevin 2 aa 49–96 S79C was labeled with Atto488 maleimide. Acceptor complex ΔN49 was assembled from syntaxin 1A, SNAP25a, and synaptobrevin 2 (aa 49–96, unlabeled or Atto488-labeled) and purified by ion exchange chromatography on a MonoQ column as described previously (32,34,35).

Protein reconstitution

A comicellization procedure in presence of n-octyl-β-d-glycoside (n-OG) followed by detergent removal via size-exclusion chromatography was used to reconstitute the proteins into small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) as described previously (38). Briefly, lipids (DOPC/POPE/POPS/cholesterol; 5:2:1:2 (n/n), 0.465 mg total) were mixed in chloroform, the solvent was removed under a nitrogen stream at 30°C and the resulting lipid film subsequently dried in vacuo for 2 h at room temperature. Lipid films were rehydrated with 50 μL of buffer A (20 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7,4, 217 mOsmol/L) and n-OG for 30 min at 0°C. Mixing with protein solution results in a nominal final protein to lipid ratio (p/l) of 1:500 at 75 mM n-OG. After incubation for 45 min at 0°C, detergent was removed by size-exclusion chromatography (Illustra NAP-10 G25 column; GE Healthcare) in buffer A. A second size-exclusion chromatography step was performed in ultrapure water to remove remaining detergent and salt. For the preparation of giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) containing the ΔN49 complex, proteo-SUVs were dried on indium tin oxide slides. GUVs were produced via electroformation (3 h, 1.6 Vpeak to peak, 12 Hz) in 255 mOsmol/L sucrose solution. For large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) containing synaptobrevin 2, proteo-SUVs were dried in a round-bottom flask in a desiccator over a saturated NaCl solution at 4°C. Sulforhodamine B (SRB) was dissolved in buffer A (43 mM, 255 mOsmol/L), the pH was adjusted to pH 7.4 and added to the proteolipid film. After incubation for 30 min, the suspended lipid film was extruded 31 times through a 400-nm polycarbonate membrane using a miniextruder (LiposoFast-Basic; Avestin, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) resulting in a mean vesicle diameter of 240 ± 100 nm and quantitative protein reconstitution as determined previously (32). Stable inclusion of SRB into the vesicle lumen was verified by UV-Vis spectroscopy (Fig. S1 A). The fusogenicity of the SRB containing LUVs with synaptobrevin 2 and SUVs containing the ΔN49 complex was analyzed using a bulk fusion assay (Fig. S1 B).

Reconstitution efficiency of ΔN49 complex in GUVs

The reconstitution efficiency R of the ΔN49 complex was determined according to Aimon et al. (39) with slight modifications. R is defined as (Eq. 1)

| (1) |

with Ip IP as the peak membrane fluorescence of ΔN49-Atto488-doped GUVs in detector counts and c0 as the nominal protein concentration of 0.2 mol%. Mref = 47,300 counts/mol% is the slope of a calibration curve of peak membrane intensities of five known Atto488 DPPE concentrations measured at exactly the same experimental conditions (Fig. S2 A), whereas DOL is the degree of labeling of the protein determined to be 35%. The fusion activity of the labeled ΔN49-Atto488 complex was analyzed in a bulk fusion assay (Fig. S2 B).

PSM preparation

Porous SiO2/Si3N4 substrates with a pore diameter of 1.2 μm for single-vesicle fusion experiments and 5 μm for fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments were flushed with a nitrogen stream and cleaned with a combination of argon and oxygen plasma. The surface was coated with titanium (20 s, 40 mA, 0.4 mbar, Cressington sputter coater 108 auto; Elektronen-Optik-Service, Dortmund, Germany) and subsequently with a 40-nm-thick gold layer by thermal evaporation (Bal-Tec Med 020; Bal-Tec, Balzers, Liechtenstein). The substrates were functionalized in 1 mM n-propanolic 6-mercapto-1-hexanol solution overnight at 8°C. For PSM preparation, substrates were rinsed with ethanol, buffer B (20 mM HEPES, 121 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.4, 255 mOsmol/L), and fixed in a chamber. 10–15 μL of GUV suspension was pipetted onto the surface and incubated for 30 min. Excess lipid material was removed by carefully rinsing with buffer B.

Indirect FRAP experiments

Indirect FRAP experiments were performed to determine the diffusion coefficient DΔN49 of the fusion-active acceptor complex ΔN49 in the solid supported part of pore-spanning membranes (s-PSM). A circular region of interest (ROI) was placed on top of the freestanding part of the PSM (f-PSM), and the fluorescence was bleached within this ROI. Because the observed fluorescence recovery in the ROI depends on the diffusion of protein in the s- and f-PSM, DΔN49 was obtained by comparing the acquired data with simulated recovery curves of indirect FRAP experiments using finite element simulations. For detailed information see the Fig. S3.

Single-vesicle assay on PSMs

Single-vesicle experiments were performed using an upright spinning disk confocal setup (spinning disk, Yokogawa CSU-X (Rota Yokogawa KG, Wehr, Germany); camera iXon 897 Ultra, (Andor Technology, Belfast, United Kingdom), pixel size 222 × 222 nm2) equipped with a water immersion objective (LUMFLN 60XW 60×, NA 1.1; Olympus, Hamburg, Germany). SRB was excited at λex = 561 nm and Atto655 DPPE at λex = 639 nm. Emission light was separated and aligned on either side of the 512 × 512 pixel2 detector using an optosplit (Acal BFi Germany, Dietzenbach, Germany) equipped with a 595/40 and 655lp emission filter. Single-vesicle docking and fusion events were recorded with a resolution of 20.83 ms/frame over 6.94 min. Each docked vesicle was tagged manually with a minimum of 4 × 4 pixel2 ROI. Time-resolved fluorescence intensity readout and data evaluation was achieved semiautomatically using a custom-made MATLAB script (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). For detailed information see the Fig. S4.

Results and Discussion

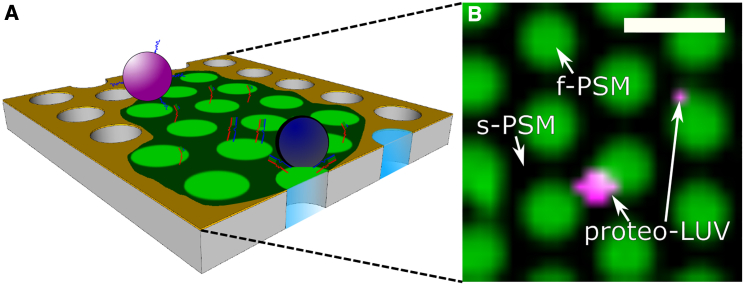

Although lipid mixing assays report on the merging of the outer and inner leaflets of the fusing membranes, no information is gathered about the formation of fusion pores. To address fusion pore formation in our SNARE-mediated single-vesicle fusion assay based on PSMs (33), we entrapped a water-soluble fluorescent dye into the vesicles at self-quenching concentrations (Fig. 1 A). To setup the system, we reconstituted the t-SNARE acceptor complex ΔN49 composed of syntaxin 1A, SNAP25a, and the soluble synaptobrevin 2 fragment (aa 49–96) into the PSMs and the v-SNARE synaptobrevin 2 (syb 2) into LUVs (34). PSMs composed of DOPC/POPE/POPS/cholesterol (5:2:1:2, n/n) and doped with the ΔN49 complex were visualized by fluorescence microscopy using 1 mol% Atto655 DPPE (Fig. 1 B).

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of the fusion assay based on pore-spanning membranes (PSMs) (A) and a fluorescence micrograph (B) of Atto655-DPPE-labeled PSMs (false colored in green) containing the t-SNARE complex ΔN49 (DOPC/POPE/POPS/cholesterol (5:2:1:2, n/n), nominal p/l = 1:500). Proteo-LUVs (false colored in magenta) doped with full-length syb 2 with the same lipid composition and p/l ratio and filled with sulforhodamine B (43 mM) are docked to the s-PSMs. Scale bar, 2 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

Owing to the gold coating on the top part of the porous substrate, only the freestanding PSMs (f-PSMs) are visible in the fluorescence micrographs, while the supported parts (s-PSMs) appear black as a result of fluorescence quenching (40,41). LUVs composed of DOPC/POPE/POPS/cholesterol (5:2:1:2, n/n) doped with syb 2 and filled with SRB were added to the PSMs (Fig. 1 B), while taking time series to monitor the docking and fusion of individual vesicles. To measure single-vesicle content release (SRB) and lipid mixing (Atto655 DPPE) simultaneously, both fluorescent dyes were recorded with a temporal resolution of 20.83 ms by means of dual-color spinning disk confocal microscopy.

In contrast to the s-PSMs, which appear black because of the gold-induced quenching of the lipid fluorophores, the vesicles are sufficiently large so that the SRB fluorophores are far enough away from the gold surface (>15 nm) to become fluorescently visible (40,41).

SNARE-specificity of docking was proven by blocking the SNARE-binding site of the ΔN49 complex with a soluble syb 2 fragment (aa 1–96) that is known to block fusion before protein reconstitution (38). No docking of syb-2-doped LUVs to PSMs was observed under these conditions. Specific docking of syb-2-doped LUVs on the PSMs was observed primarily on the supported parts of the PSMs with the majority of vesicles located at the edge between the f-PSM and s-PSM, in agreement with previous observations (32). Vesicle aggregation at the edges of the pores, a region where the membrane is known to bend ∼100 nm into the pore (42,43) was also monitored by Ramakrishnan et al. (44). They discussed this finding in terms of protein aggregation in this area. Although proteins are mobile in the s-PSM, the mobility is by a factor of two to four lower compared to that in the f-PSM (see Fig. 2 C; (32,34)). Of note, already a small fraction of immobile protein would immobilize the vesicle. Besides this aspect, we further propose that a larger contact area between the docked vesicle and the curved PSM might increase the number of SNARE complexes leading to vesicle immobilization.

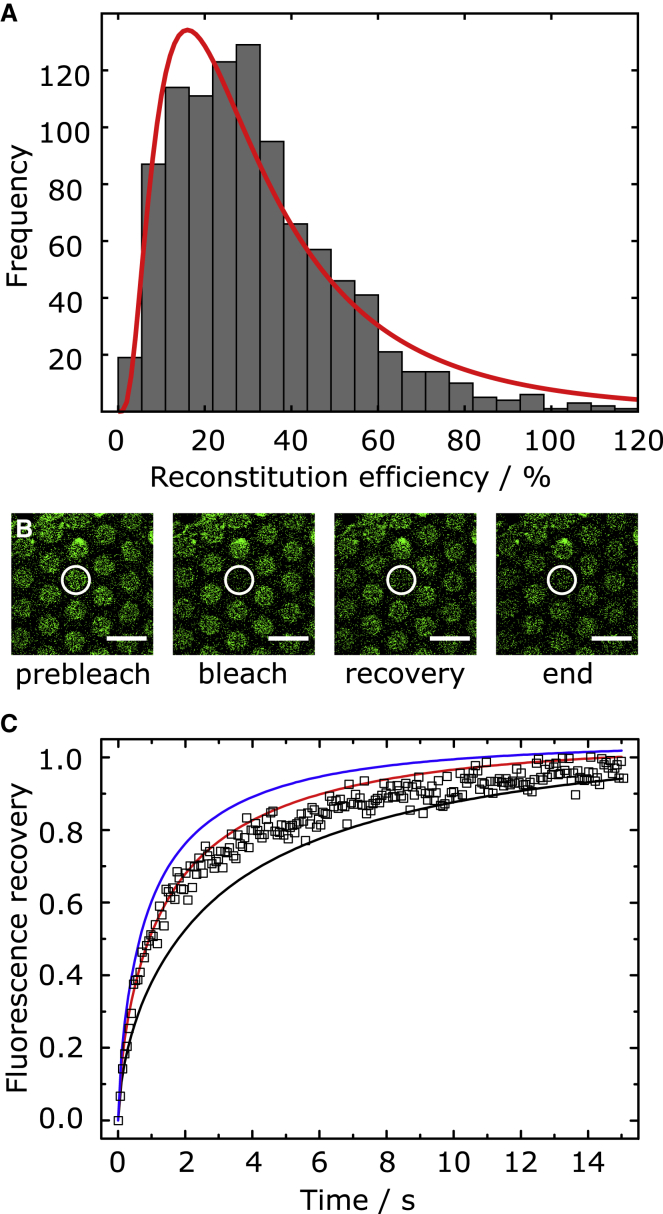

Figure 2.

Determination of the reconstitution efficiency and mobility of the ΔN49 acceptor complex labeled with an Atto488 syb 2 (49–96) fragment. (A) Reconstitution efficiency of the ΔN49 complex in GUVs composed of DOPC/POPE/POPS/cholesterol (5:2:1:2, n/n) and nominal p/l = 1:500 (N = 1015). The red line is a result of fitting a log-normal distribution to the data with a median value of 26 ± 24%. Values with a reconstitution efficiency >120% are not displayed in the graph (N>120% = 49). (B) Fluorescence micrographs of an indirect FRAP experiment. The fluorescence of an f-PSM composed of DOPC/POPE/POPS/cholesterol (5:2:1:2, n/n), doped with Atto488-labeled ΔN49 acceptor complex (nominal p/l = 1:250), was bleached (white circle), and the recovery of the fluorescence in the f-PSM was monitored as a function of time. Scale bars, 10 μm. (C) Normalized (mean (N = 33)) time-dependent fluorescence recovery curve (open squares) and simulated recovery curves with DΔN49 (s-PSM) = 0.5 (black), 1 (red), and 1.5 (blue) μm2 s−1, and DΔN49 (f-PSM) = 3.4 μm2 s−1. To see this figure in color, go online.

Mobility and reconstitution efficiency of fusion-active acceptor complex

The specific docking of syb-2-doped vesicles indicates the successful reconstitution of the ΔN49 complex in the PSMs. However, to quantify the reconstitution efficiency and the mobility of the ΔN49 complex within the PSMs, we performed additional experiments using a ΔN49 complex that was fluorescently labeled with an Atto488-labeled syb 2 fragment (aa 49–96 S79C). In contrast to a study in which SNAP25a was labeled via maleimide chemistry at a single cysteine residue to determine the reconstitution efficiency in GUVs (45), we pursued this approach to ensure that only the fusion-active ΔN49 acceptor complex is observed and not the fusion inactive SNAP25a/syntaxin 1A (1:2) complex (38). Fusogenicity of this construct was verified in a bulk fusion assay (Fig. S2 B). By using lipid probes as standards (Fig. S2 A), the fluorescence intensities of ΔN49-Atto488-doped GUVs (N = 1015) were read out to calculate the reconstitution efficiency (Fig. 2 A) of the ΔN49 complex. By fitting a log-normal function to the histogram, a reconstitution efficiency of 26 ± 24% (median) was obtained. In few cases, a reconstitution efficiency of >100% was calculated. Given the nominal protein/lipid ratio of 1:500, that means that the actual median protein/lipid ratio reads 1:1900. As the reconstitution of the ΔN49 acceptor complex into SUVs was proven to be quantitative (32) and SUVs are the starting material for the preparation of GUVs, the large deviation from the nominal value and the large variation in protein content is attributed to the electroformation process (32,46,47). Each individual GUV forms one PSM patch on the porous substrate, which explains why we find a large variation of docked vesicles on the individual membrane patches. The average number of docked vesicles was determined to be 0.43 ± 0.56 docked vesicles μm−2.

To investigate the lateral mobility of the ΔN49 acceptor complex in the s-PSMs, we performed so-called indirect FRAP experiments (Fig. 2 B) as described previously (32). By averaging 33 individual FRAP curves (Fig. 2 C) and comparing them with simulated recovery curves using finite element simulations (Supporting Materials and Methods), a diffusion coefficient of DΔN49 = 1.0 ± 0.5 μm2 s−1 and DLipid = 2 ± 1 μm2 s−1 (Fig. S3 B) was estimated. The protein complex mobility is similar to the one that we determined for the single OregonGreen-labeled syntaxin 1A transmembrane domain (Dsyx1A = 1.1 ± 0.2 μm2 s−1) (32) and shows that the diffusion coefficient is mainly determined by the transmembrane helix embedded in the bilayer.

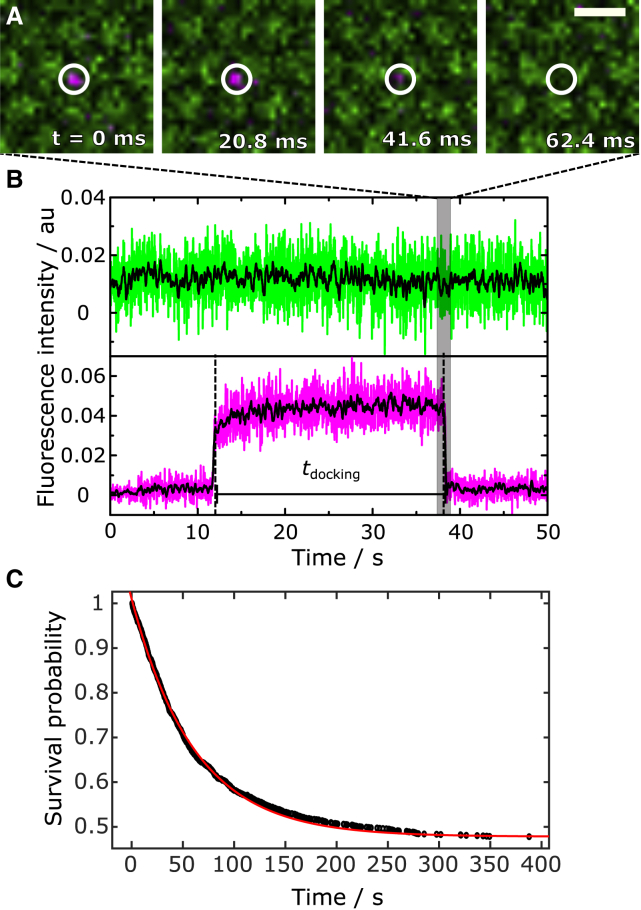

Kinetics of single-vesicle content release events

Even though single-vesicle fusion assays are rich in information, as each fusion event can be analyzed individually in a time-resolved manner, the drawback is that a sufficiently large number of events needs to be evaluated to provide good statistics. Here, we detected 1609 docked vesicles of seven different preparations and 68 individual membrane patches by their SRB fluorescence. 840 of the 1609 vesicles (52%) proceeded to fusion with the s-PSMs. Fluorescence intensity time traces of each docked vesicle within a ROI (Fig. 3 A) was read out from the time series. In the given example, complete content release upon fusion pore formation is detected by a decrease in SRB fluorescence intensity to the baseline level (Fig. 3, A and B). Lack of an increase in s-PSM fluorescence intensity (Fig. 3 B, green) indicates no detectable influx of lipids from the s-PSM via a fusion stalk. This observation suggests that the fusion pore is formed very rapidly concomitant with the release of the content dye and a rapid collapse of the vesicle into the s-PSM.

Figure 3.

(A) Fluorescence micrographs of a docked vesicle filled with SRB (shown in magenta). The region of interest (ROI) used to readout the fluorescence time trace is highlighted with a white circle. The vesicle fuses with the PSM (shown in green). Scale bar, 2 μm. (B) Time-resolved fluorescence intensity time traces of the vesicle (magenta) and the membrane (green) obtained from the ROI in (A). The black lines are 20 data points-smoothed data. (C) Survival analysis of docked vesicles and monoexponential fit (red line) to the data leads to a mean docking lifetime of τdocking = 61 ± 2 s. To see this figure in color, go online.

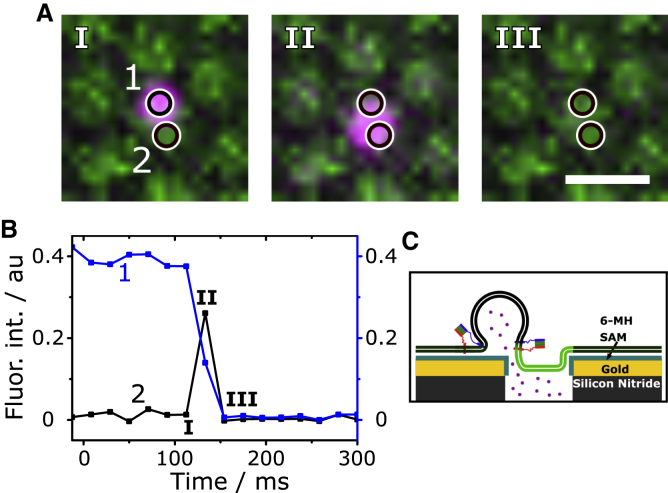

Content release has been observed previously upon fusion of single vesicles with planar membranes. In these studies, supported lipid membranes were generated. Pore formation during the fusion process was concluded from characteristic fluorescent time traces observed upon release of self-quenching SRB concentrations. A first increase in fluorescence intensity followed by a decrease as a result of the diffusion of SRB with a two-dimensional diffusion behavior (cleft between membrane and support) rather than a three-dimensional (3D) diffusion behavior (bulk solution) indicates the release of the fluorescent dye into the small cleft between membrane and support (22,28, 29, 30, 31). In our setup, we make use of the underlying aqueous compartments, which can uptake the released SRB dye. This process can, in few cases, be directly visualized (Fig. 4). The characteristic video sequence along with the fluorescent time traces obtained at the site of vesicle docking (Fig. 4, A and B, ROI 1) or at the position of the neighboring f-PSM (Fig. 4, A and B, ROI 2) shows that the content is released below the membrane, indicating fusion pore formation. In contrast, if the vesicle ruptures, the content is released into the bulk solution directly above the membrane (Fig. S5), which is discernable as a spike in the SRB fluorescence intensity time trace at the position of vesicle docking (Fig. S5 B). This time trace signature can be readily used to separate burst events (0.003%, see Fig. 7) from fusion pore formation events.

Figure 4.

(A) Time lapse fluorescence images of a fusing vesicle (magenta) with transfer of its content across the PSM. Scale bar, 2 μm. (B) Fluorescence intensity time traces obtained from ROI 1 and 2 shown in (A). After docking (I), the vesicle fuses and releases its content (II) into the aqueous compartment underneath the adjacent f-PSM, where it leads to an increase in fluorescence intensity visible in ROI 2. (C) Schematic illustration of a vesicle docked at the edge of a pore and releasing its content into the underlying aqueous compartment. The figure is not drawn to scale. To see this figure in color, go online.

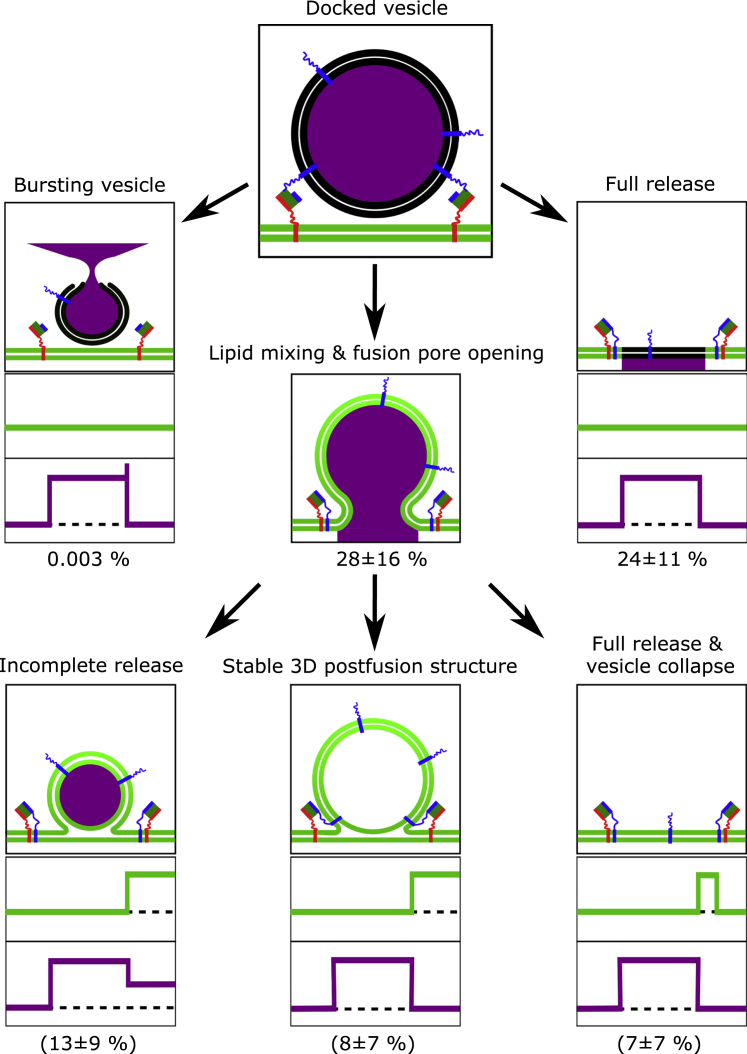

Figure 7.

Proposed fusion pathways determined by single-vesicle docking/fusion events. 1609 docked vesicles were analyzed, and 52% of these docked vesicles proceeded to fusion. 75% of these vesicles released their content completely through fusion pore formation. Only 0.003% of vesicles ruptured and released their content in a burst into the solution above the membrane. Overall, 28 ± 16% of vesicles fuse via a fusion stalk with different 3D postfusion structures. To see this figure in color, go online.

To extract the mean docking lifetime, a survival analysis of all docked vesicles was performed (Fig. 3 C). Fitting a monoexponential decay function to the data results in τdocking = 61 ± 2 s. This monoexponential decay, indicating a one-step process for fusion, was also observed by Gong et al. (48), who monitored content mixing between two vesicle populations on a single-vesicle level. The observed docking lifetimes of tens of seconds are similar to those reported previously for synthetic vesicles (∼30 s) (32,34) and chromaffin granules (80 ± 16 s) (35) on PSMs with reconstituted ΔN49 complex using lipid mixing as a readout parameter. As shown in Fig. S6, a different analysis as performed previously by us (32,34,35) did not affect the resulting docking lifetime significantly.

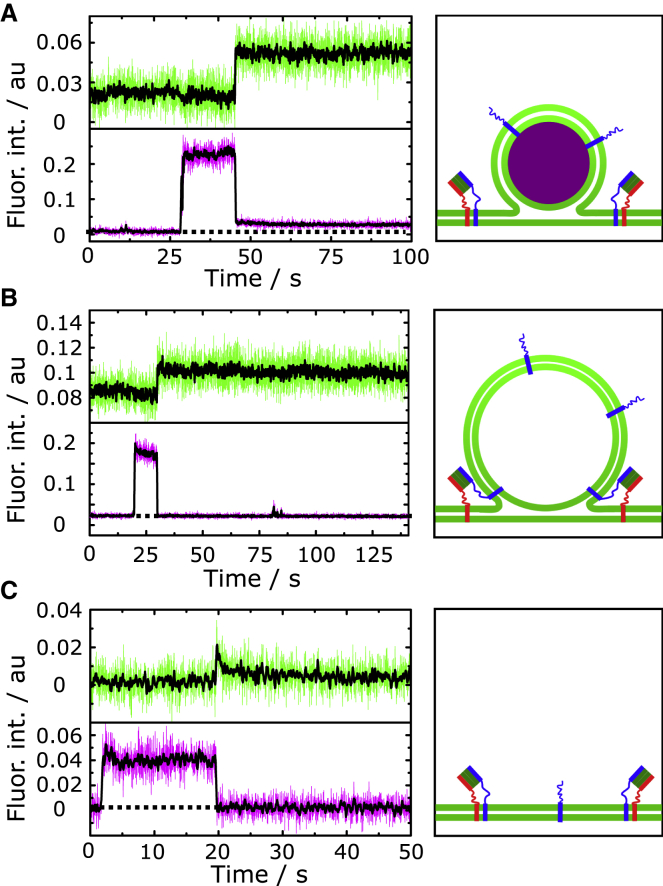

During the fusion process, several different fusion pathways could be distinguished each being unique in their fluorescence intensity time traces (Fig. 5). Whereas the fluorescence intensity time trace of SRB reports on the formation of a fusion pore releasing the dye underneath the membrane, the Atto655 DPPE fluorescence provides information about the influx of this lipid dye into the 3D structure of the fusing vesicle if the vesicle is docked to the gold-covered pore rims, which is found for the majority of docked vesicles. In contrast to the event shown in Fig. 3 B, in which lipid diffusion from the s-PSM into the fusing vesicle was not discernable, an increase in Atto655 DPPE fluorescence intensity indicates that lipid material diffuses from the s-PSM into the unlabeled vesicular membrane, thus increasing the distance of the lipid dye to the gold surface, which results in a dequenching of fluorescence (Fig. S7). It has been shown previously that the quenching or enhancement of fluorescence depends upon the distance between fluorophores and the gold surface. Chi et al. (40) quantified that fluorescence quenching occurs at distances within ∼15 nm from the gold surface, whereas surface-enhanced fluorescence is observed at tens of nanometers beyond the range of quenching with the maximal enhancement at ∼40–50 nm. Hence, we conclude that if an increase in Atto655 DPPE fluorescence is observed, a vesicular structure connected with the s-PSM is present with an increased fluorescence intensity given by the three-dimensional structure of the vesicle and the dequenching effect. In case of an incomplete content release (13 ± 9% of all fusion events, see Fig. 7), due to the formation of a metastable fusion pore, the 3D structure remains intact during the whole observation time (Fig. 5 A). Besides partial release of the content, also complete release events were observed. Here, we distinguish between two cases: either a complete SRB release is observed, whereas the 3D structure of the vesicle remains intact (Fig. 5 B), or the vesicular 3D structure fully fuses into the s-PSM (Fig. 5 C). The observed decay in Atto655 DPPE fluorescence intensity is attributed to a vesicle collapse concomitant with a re-entering of the Atto655 DPPE fluorophores into the quenching regime of the gold surface. The cases of a remaining 3D vesicular structure associated with a full or partial content release can be discussed in the context of “kiss and run” fusion (3,49, 50, 51, 52, 53). Vesicles that remain in a visible 3D postfusion structure while releasing their content would be readily accessible for a direct retrieval in a “kiss and run” fashion. However, one has to be aware that, in this study, only the minimal fusion machinery has been reconstituted and it is still under investigation how the full neuronal protein set guides the fusion pathways. Because we are able to determine the time points, during which the fusion pore opens and the lipids from the s-PSM diffuse into the fusing vesicle, we looked more deeply into these kinetics. On the one hand, we determined the time span τ3D between Atto655 DPPE influx into the fusing vesicle and the onset of the collapse of the 3D vesicular structure (Fig. 6, A and B).

Figure 5.

(Left) Fluorescence intensity time traces of fusing vesicles (magenta) with the planar s-PSMs (green) with smoothed data (black) showing different fusion pathways with (right) the corresponding schematics of the (post)fusion structure. (A) Incomplete content release with a remaining three-dimensional (3D) postfusion structure. (B) Complete content release with a remaining stable 3D postfusion structure. (C) Complete content release with an unstable 3D postfusion structure. To see this figure in color, go online.

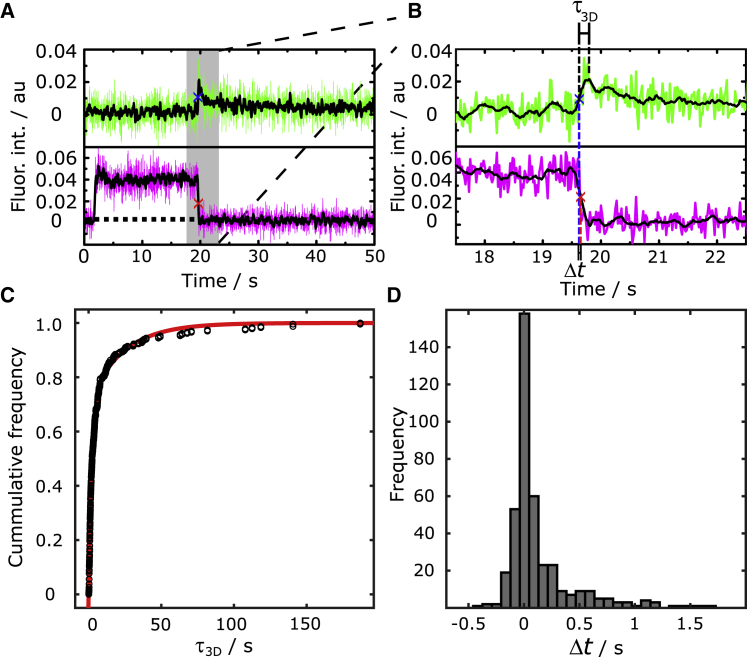

Figure 6.

Overview (A) and zoom (B) of time-resolved fluorescence intensity traces (smoothed, black) of a vesicle (magenta) fusing with the s-PSM (green). An increase in the lipid fluorescence intensity is attributed to the Atto655 DPPE diffusion into the 3D structure of the lipid-unlabeled vesicle. τ3D is defined as the time span between the Atto655 DPPE influx into the fusing vesicle (marked by a blue x) until the onset of the vesicle collapse. Δt is defined as the lag time between the Atto655 DPPE diffusion into the 3D structure and fusion pore formation (marked by a red x). (C) Cumulative frequency function of τ3D (N = 234) together with a biexponential fit (red) resulting in rate constants of k1 = 0.043 ± 0.004 s−1 and k2 = 0.43 ± 0.01 s−1. (D) Histogram of lag times (Δt, N = 455). Values with lag times of <−0.7 s and >2 s are not displayed in the graph (N−0.7s<Δt>2s = 51). To see this figure in color, go online.

Fig. 6 C shows the cumulative distribution function of τ3D (N = 234). Only a biexponential function described the data well with rate constants of k1 = 0.043 ± 0.004 s−1 and k2 = 0.43 ± 0.01 s−1. This result suggests that there are two vesicle populations, one that starts to collapse fast and the other one remaining intact longer. Previously, we reported on such two vesicle populations in a qualitative manner by making use of a lipid mixing assay (32). More importantly, even in live chromaffin cells, these two vesicle populations have been reported (54). The kinetic constant obtained for the fast collapsing synthetic vesicles is in good agreement with the kinetics we found for chromaffin granules (0.24 ± 0.05 s−1) (35) and is in the same range as values found for the endocytosis kinetics observed in vivo (∼1 s−1) (55,56), implying that these types of collapsing vesicles can be directly retrieved from the target membrane in a “kiss and run” manner. Owing to the given time resolution of 20.83 ms, we were able to determine a lag time Δt between the Atto655 DPPE diffusion into the 3D structure and fusion pore formation (Fig. 6, A and B). Fig. 6 D shows the corresponding histogram (N = 455) of Δt. A positive value of Δt means that the influx of Atto655 DPPE into the 3D vesicular structure occurs prior fusion pore formation. The distribution indicates that in most of the fusion processes content release follows immediately after lipid mixing with a median time difference of only 42 ± 11 ms, which is close to the resolution limit of the setup of ∼20 ms. Both processes occur almost simultaneously in agreement with previous reports (31,36). For comparison, Stratton et al. quantified the lag time to be 18.3 ms (31).

In Fig. 7, we summarize the different fusion pathways that we observed. The different pathways were identified according to the two fluorescence intensity time traces (Atto655 DPPE, green; SRB, magenta) (see e.g., Figs. 3 B and 5, A–C). Overall, 1609 docked vesicles were analyzed, 52% of these docked vesicles proceeded to fusion. The different percentages were calculated as weighted means according to Eq. 2:

| (2) |

with being the respective percentage of the fusion pathway found at n = 68 individual membrane patches and being the respective amount of docked vesicles/μm2 at this patch as a weighting factor. We assume that the number of docked vesicles is a function of reconstituted ΔN49 complex in the PSM. Thus, we need to account for the broad distribution of the ΔN49 complex in the GUVs (Fig. 2 A), which is directly transferred into the membrane patches.

By comparing the docking time, fusion efficiency, and the different fusion pathways (Fig. S8) with the number of docked vesicles, we conclude that the distribution of the ΔN49 complex does not significantly influence the calculated mean values. The total number of events (N) for each pathway is summarized in Table S1. The weighted standard deviation SD was calculated according to Eq. 3

| (3) |

24 ± 11% of docked vesicles released their content without visible lipid diffusion via a fusion stalk. 28 ± 16% (54% of fusing) vesicles underwent fusion with visible lipid mixing into an either stable or unstable 3D structure and/or showing an incomplete content release. 75% of the vesicles that proceeded to fusion released their content completely either directly or consecutively. A process in which hemifusion occurs without fusion pore formation was negligible. These findings differ from results reported by others, who worked with supported lipid bilayers. Stratton et al. (31) found a large fraction of incomplete content release (80%), whereas Kreutzberger et al. (29) reported on dead-end hemifusion (∼65%). A direct comparison of the results is difficult because, besides the differences in the space underneath the membranes, other parameters such as the lipid composition of the vesicle and the planar membrane, contributing significantly to the fusion pathways (29,31), are different.

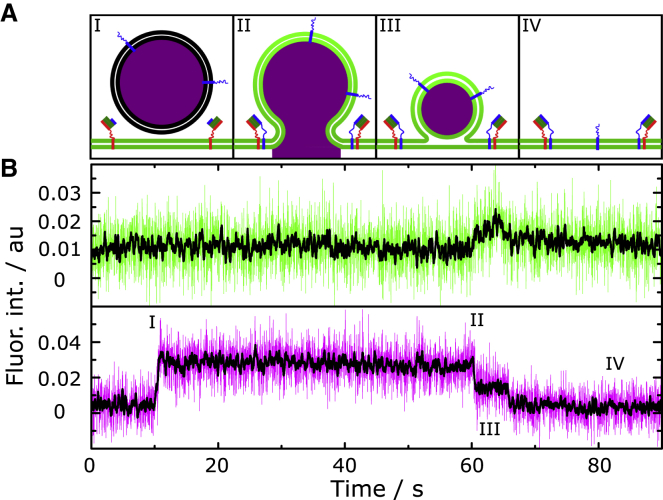

Dynamic openings and closings of the fusion pore

Interestingly, in ∼50% of the fusing vesicles, of which a first partial content release was observed, the fusion pore reopens (Fig. 8, A and B). In rare cases, this process even consists of three or more consecutive partial dye release events. Similar fusion behaviors have been frequently described in in vivo experiments and were referred to as flickering fusion pores (6,57, 58, 59, 60). Staal et al. (6) detected consecutive dopamine release events (two to five times) in midbrain neurons that were proven to originate from one individual vesicle. Such transient fusion pore dynamics is thought to first facilitate vesicle recycling in a “kiss and run” manner and would lead to a long-range signaling as well as long-lasting activation of postsynaptic receptors (3,6). In in vitro assays, dynamics of fusion pores have been only rarely described (48). Gong et al. (48) were first to show that a stepwise content release is possible in a simple, well-defined model system. In their study, two highly curved vesicle populations containing either the v- or the t-SNAREs fused with each other with 72% fusing in a single step and the remaining 38% fusing in a two- or three-step process. Our findings indeed support the occurrence of more than one release event. Such observed dynamic transient pores are hence not a function of the full neuronal protein machinery, but can already be observed with the simple minimal fusion proteins reconstituted in a model membrane system.

Figure 8.

(A) Schematic drawing of the fusion pathway for a stepwise release of the vesicle content with (B) a typical fluorescence intensity time trace of the vesicle (magenta) and planar s-PSM (green) with smoothed data (black). Vesicles with a first partial content release (II) undergo a consecutive fusion pore formation with a likeliness of 51%. 8% of the whole vesicle population show this stepwise pore formation with 2% resulting in a complete release as the final situation. In rare cases, fusing vesicles show even more than two release events. To see this figure in color, go online.

Conclusions

Although several single-fusion assays have illuminated elementary steps occurring during neuronal fusion, there is still a lack of in vitro assays that are capable of simultaneously reporting on all the different intermediate states including 3D vesicular structures and fusion pore formation including flickering pores. In our membrane system, vesicle bursting is negligible and can be unambiguously distinguished from fusing vesicles forming a fusion pore. Our results demonstrate that the different fusion intermediates and fusion pathways as reported in vivo, are apparently not a result of the large number of additional proteins involved in the fusion process but are already an intrinsic characteristic of the simple neuronal fusion machinery composed of only three SNAREs.

Author Contributions

P.M. performed the fusion experiments. K.H. and L.V. performed the experiments with labeled ΔN49 complex. P.M. and I.M. analyzed the data. C.S. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank R. Jahn for providing the SNARE constructs.

The authors thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for financial support (SFB 803, project B04).

Editor: Ilya Levental.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.05.023.

Supporting Citations

References (61,62) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Jahn R., Fasshauer D. Molecular machines governing exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 2012;490:201–207. doi: 10.1038/nature11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Südhof T.C. Neurotransmitter release: the last millisecond in the life of a synaptic vesicle. Neuron. 2013;80:675–690. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alabi A.A., Tsien R.W. Perspectives on kiss-and-run: role in exocytosis, endocytosis, and neurotransmission. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013;75:393–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao Y., Zorman S., Zhang Y. Single reconstituted neuronal SNARE complexes zipper in three distinct stages. Science. 2012;337:1340–1343. doi: 10.1126/science.1224492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindau M., Alvarez de Toledo G. The fusion pore. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1641:167–173. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(03)00085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Staal R.G.W., Mosharov E.V., Sulzer D. Dopamine neurons release transmitter via a flickering fusion pore. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:341–346. doi: 10.1038/nn1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han X., Wang C.-T., Jackson M.B. Transmembrane segments of syntaxin line the fusion pore of Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Science. 2004;304:289–292. doi: 10.1126/science.1095801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bai J., Wang C.-T., Chapman E.R. Fusion pore dynamics are regulated by synaptotagmin∗t-SNARE interactions. Neuron. 2004;41:929–942. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lira R.B., Dimova R. Chapter six: fusion assays for model membranes. A critical review. In: Lipowsky R., editor. Multiresponsive Behavior of Biomembranes and Giant Vesicles. Academic Press; 2019. pp. 229–270. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunger A.T., Cipriano D.J., Diao J. Towards reconstitution of membrane fusion mediated by SNAREs and other synaptic proteins. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015;50:231–241. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2015.1023252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber T., Zemelman B.V., Rothman J.E. SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell. 1998;92:759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Bogaart G., Holt M.G., Jahn R. One SNARE complex is sufficient for membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:358–364. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernandez J.M., Kreutzberger A.J.B., Jahn R. Variable cooperativity in SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:12037–12042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407435111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez J.M., Stein A., Jahn R. Membrane fusion intermediates via directional and full assembly of the SNARE complex. Science. 2012;336:1581–1584. doi: 10.1126/science.1221976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoon T.-Y., Okumus B., Ha T. Multiple intermediates in SNARE-induced membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:19731–19736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606032103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai Y., Diao J., Shin Y.-K. Fusion pore formation and expansion induced by Ca2+ and synaptotagmin 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:1333–1338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218818110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kyoung M., Srivastava A., Brunger A.T. In vitro system capable of differentiating fast Ca2+-triggered content mixing from lipid exchange for mechanistic studies of neurotransmitter release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:E304–E313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107900108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowen M.E., Weninger K., Chu S. Single molecule observation of liposome-bilayer fusion thermally induced by soluble N-ethyl maleimide sensitive-factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) Biophys. J. 2004;87:3569–3584. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.048637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu T., Tucker W.C., Weisshaar J.C. SNARE-driven, 25-millisecond vesicle fusion in vitro. Biophys. J. 2005;89:2458–2472. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fix M., Melia T.J., Simon S.M. Imaging single membrane fusion events mediated by SNARE proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7311–7316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401779101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang T., Smith E.A., Weisshaar J.C. Lipid mixing and content release in single-vesicle, SNARE-driven fusion assay with 1-5 ms resolution. Biophys. J. 2009;96:4122–4131. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreutzberger A.J.B., Kiessling V., Tamm L.K. In vitro fusion of single synaptic and dense core vesicles reproduces key physiological properties. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3904. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11873-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karatekin E., Rothman J.E. Fusion of single proteoliposomes with planar, cushioned bilayers in microfluidic flow cells. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:903–920. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karatekin E., Di Giovanni J., Rothman J.E. A fast, single-vesicle fusion assay mimics physiological SNARE requirements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:3517–3521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914723107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domanska M.K., Kiessling V., Tamm L.K. Single vesicle millisecond fusion kinetics reveals number of SNARE complexes optimal for fast SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:32158–32166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiessling V., Liang B., Tamm L.K. Planar supported membranes with mobile SNARE proteins and quantitative fluorescence microscopy assays to study synaptic vesicle fusion. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017;10:72. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Domanska M.K., Kiessling V., Tamm L.K. Docking and fast fusion of synaptobrevin vesicles depends on the lipid compositions of the vesicle and the acceptor SNARE complex-containing target membrane. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2936–2946. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiessling V., Ahmed S., Tamm L.K. Rapid fusion of synaptic vesicles with reconstituted target SNARE membranes. Biophys. J. 2013;104:1950–1958. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreutzberger A.J.B., Kiessling V., Tamm L.K. High cholesterol obviates a prolonged hemifusion intermediate in fast SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Biophys. J. 2015;109:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kreutzberger A.J.B., Kiessling V., Tamm L.K. Reconstitution of calcium-mediated exocytosis of dense-core vesicles. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1603208. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1603208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stratton B.S., Warner J.M., O’Shaughnessy B. Cholesterol increases the openness of SNARE-mediated flickering fusion pores. Biophys. J. 2016;110:1538–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuhlmann J.W., Junius M., Steinem C. SNARE-mediated single-vesicle fusion events with supported and freestanding lipid membranes. Biophys. J. 2017;112:2348–2356. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kocun M., Lazzara T.D., Janshoff A. Preparation of solvent-free, pore-spanning lipid bilayers: modeling the low tension of plasma membranes. Langmuir. 2011;27:7672–7680. doi: 10.1021/la2003172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwenen L.L.G., Hubrich R., Steinem C. Resolving single membrane fusion events on planar pore-spanning membranes. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:12006. doi: 10.1038/srep12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hubrich R., Park Y., Steinem C. SNARE-mediated fusion of single chromaffin granules with pore-spanning membranes. Biophys. J. 2019;116:308–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.11.3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramakrishnan S., Gohlke A., Pincet F. High-throughput monitoring of single vesicle fusion using freestanding membranes and automated analysis. Langmuir. 2018;34:5849–5859. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b00116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fasshauer D., Antonin W., Jahn R. Mixed and non-cognate SNARE complexes. Characterization of assembly and biophysical properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:15440–15446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pobbati A.V., Stein A., Fasshauer D. N- to C-terminal SNARE complex assembly promotes rapid membrane fusion. Science. 2006;313:673–676. doi: 10.1126/science.1129486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aimon S., Manzi J., Toombes G.E.S. Functional reconstitution of a voltage-gated potassium channel in giant unilamellar vesicles. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chi Y.S., Byon H.R., Choi I.S. Polymeric rulers. Distance-dependent emission behaviors of fluorophores on flat gold surfaces and bioassay platforms using plasmonic fluorescence enhancement. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008;18:3395–3402. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schneider G., Decher G., Blanchard-Desce M. Distance-dependent fluorescence quenching on gold nanoparticles ensheathed with layer-by-layer assembled polyelectrolytes. Nano Lett. 2006;6:530–536. doi: 10.1021/nl052441s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Böcker M., Muschter S., Schäffer T.E. Imaging and patterning of pore-suspending membranes with scanning ion conductance microscopy. Langmuir. 2009;25:3022–3028. doi: 10.1021/la8034227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schütte O.M., Mey I., Steinem C. Size and mobility of lipid domains tuned by geometrical constraints. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E6064–E6071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704199114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramakrishnan S., Bera M., Rothman J.E. Synaptotagmin oligomers are necessary and can be sufficient to form a Ca2+ -sensitive fusion clamp. FEBS Lett. 2019;593:154–162. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witkowska A., Jahn R. Rapid SNARE-mediated fusion of liposomes and chromaffin granules with giant unilamellar vesicles. Biophys. J. 2017;113:1251–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garten M., Aimon S., Bassereau P., Toombes G.E.S. Reconstitution of a transmembrane protein, the voltage-gated ion channel, KvAP, into giant unilamellar vesicles for microscopy and patch clamp studies. J Vis Exp. 2015:52281. doi: 10.3791/52281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Girard P., Pécréaux J., Bassereau P. A new method for the reconstitution of membrane proteins into giant unilamellar vesicles. Biophys. J. 2004;87:419–429. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gong B., Choi B.-K., Kim K. High affinity host-guest FRET pair for single-vesicle content-mixing assay: observation of flickering fusion events. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:8908–8911. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b05385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aravanis A.M., Pyle J.L., Tsien R.W. Single synaptic vesicles fusing transiently and successively without loss of identity. Nature. 2003;423:643–647. doi: 10.1038/nature01686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qin X., Tsien R.W., Park H. Real-time three-dimensional tracking of single synaptic vesicles reveals that synaptic vesicles undergoing kiss-and-run fusion remain close to their original fusion site before reuse. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;514:1004–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevens C.F., Williams J.H. “Kiss and run” exocytosis at hippocampal synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:12828–12833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230438697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsuboi T., Rutter G.A. Multiple forms of “kiss-and-run” exocytosis revealed by evanescent wave microscopy. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:563–567. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.An S., Zenisek D. Regulation of exocytosis in neurons and neuroendocrine cells. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2004;14:522–530. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chiang H.-C., Shin W., Wu L.-G. Post-fusion structural changes and their roles in exocytosis and endocytosis of dense-core vesicles. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3356. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gandhi S.P., Stevens C.F. Three modes of synaptic vesicular recycling revealed by single-vesicle imaging. Nature. 2003;423:607–613. doi: 10.1038/nature01677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sankaranarayanan S., Ryan T.A. Real-time measurements of vesicle-SNARE recycling in synapses of the central nervous system. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:197–204. doi: 10.1038/35008615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fulop T., Radabaugh S., Smith C. Activity-dependent differential transmitter release in mouse adrenal chromaffin cells. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:7324–7332. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2042-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klyachko V.A., Jackson M.B. Capacitance steps and fusion pores of small and large-dense-core vesicles in nerve terminals. Nature. 2002;418:89–92. doi: 10.1038/nature00852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou Z., Misler S., Chow R.H. Rapid fluctuations in transmitter release from single vesicles in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Biophys. J. 1996;70:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79718-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alvarez de Toledo G., Fernández-Chacón R., Fernández J.M. Release of secretory products during transient vesicle fusion. Nature. 1993;363:554–558. doi: 10.1038/363554a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen R.F., Knutson J.R. Mechanism of fluorescence concentration quenching of carboxyfluorescein in liposomes: energy transfer to nonfluorescent dimers. Anal. Biochem. 1988;172:61–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jönsson P., Jonsson M.P., Höök F. A method improving the accuracy of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching analysis. Biophys. J. 2008;95:5334–5348. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.134874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.