Abstract

BACKGROUND

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the liver (IMTL) are extremely rare neoplasms and very little is known about their clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and biological behavior. Due to their absolute rarity, it is almost impossible to obtain a definite diagnosis without histological examination. Because of their intermediate biological behavior with the risk for local recurrence and metastases, surgical resection is recommend whenever IMTL is suspect.

CASE SUMMARY

We herein present a case of an otherwise healthy 32-year-old woman who presented with intermittent fever, unclear anemia, malaise and right flank pain 4 mo postpartum. The liver mass in segment IVa/b was highly FDG avid in the positron emission tomography-computed tomography. Hepatic resection was performed achieving a negative resection margin and an immediate resolution of all clinical symptoms. Histological analysis diagnosed the rare finding of an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver and revealed cytoplasmic anaplastic lymphoma kinase expression by immunohistochemistry. Twelve months follow-up magnetic resonance imaging showed no recurrence and no metastases in the fully recovered patient.

CONCLUSION

IMTLs are extremely rare and difficult to diagnose. Due to their intermediate biological behavior, surgical resection should be perform whenever feasible and patients should be followed-up in order to detect recurrence and metastasis as early as possible.

Keywords: Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, Hepatic, Inflammatory, Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-expression, Case report, Review

Core tip: In summary of the literature and with the experience from our own recent case, complete surgical resection of suspected inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the liver should be the preferred treatment of choice in order to rule out malignancy, avoid long-term medical treatment and to be able to recommend an appropriate follow-up for the patient.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMT) are rare diagnostic findings and little is known about their etiology, pathogenesis and clinical behavior. First described in the lungs, this rare neoplasm can occur in various tissues and organs of the human body[1-4]. Whereas IMTs were originally considered as inflammatory pseudo tumors, they are now recognized as true neoplasms in the histological typing of the soft tissue tumors classification of the World Health Organization with intermediate biological potential due to their ability to recur and to metastasize[1,4]. IMTs of the liver (IMTL) are even more seldom and most published literature are case reports (Table 1) or small case series (Table 2). Most patients present with either abdominal pain or fever, in others the tumor is detected incidentally[5]. A systemic inflammatory process with leukocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and other systemic inflammatory markers often accompanies the clinical presentation[3,5-11]. Although this type of neoplasm can occur in individuals of all ages, it seems more common in children and young adults[4,12]. The etiology of IMTL is unclear[4], but cytogenetic alterations suggest a clonal origin of theses lesions[3,4]. Proof of diagnosis is difficult since no tumor markers are available and radiological findings are often not specific[6,8,13]. Surgical resection is usually considered as the treatment of choice for these rare findings. IMTLs mostly present as solitary lesions with typical firm surfaces. Histopathologically, they can have three basic patterns, which are often combined in one tumor: (1) A myxoid/vascular; (2) Spindel cell; and (3) Hypocellular fibrous pattern[4]. The tumor is frequently infiltrated by eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells[4]. Rearrangements of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene locus are common in IMTs supporting its neoplastic origin. ALK overexpression and its positive immunohistochemical staining is reported in 50%-60% of the cases[14]. Differential diagnoses of IMTL include metastatic sarcomatoid carcinoma, spindel cell sarcoma or melanoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, sarcoma, solitary fibrous tumor and calcifying tumors besides the large group of inflammatory pseudotumors[6]. Although these lesions generally show a benign behavior, there is the possibility of malignant transformation and development of metastases[15,16]. Some small case series of IMTs described the anatomic location, size and age as potential risk factors correlated with recurrence[2,13,17]. In addition, ALK reactivity in the primary tumor was associated with a non-metastatic course of the disease[6]. In the liver, a malignant transformation is extremely rare and only very few cases with local recurrence or metastases have been described[1,18]. Due to the scarcity of this disease, the role of a preoperative biopsy is unclear, but because of the difficulty to obtain a proper histopathological diagnosis and the risk of malignant transformation, surgical resection is usually recommended whenever technically feasible[5,8,9,19,20].

Table 1.

Case reports

| Ref. | n | Age (yr) | Gender | Clinical and laboratory findings | Radiology | Localization | Tentative diagnose | Treatment | Histology | Follow up |

| Watanabe et al[32], 2019 | 1 | 70 | Female | Incidental finding | CT unenhanced, low density | Right lobe | HCC | Right partial hepatectomy | Unencapsuled, partly ill defined expansive mass, myofibroblast-, fibroblast cells, inflammatory cells, SMA+, cytokeratins AE1/AE3+; CK7,CK18+, Desmin-, CD68-, IgG4-, ALK- | No recurrence after 7 mo |

| Al-Hussaini et al[24], 2019 | 1 | 8 | Male | FUO, weight loss, hepatomegaly, normal liver enzymes, CRP↑ | MRI: Contrast-enhancing, hyper-intense, well-defined lesion | Right lobe | Infection DD malignancy | Right lobe hepatectomy | Multinucleated giant cells, inflammatory cells, SMA-, ALK-1-, CD-21- CD-23- CD-68+ | No recurrence after 4 mo |

| Lu et al[33], 2018 | 1 | 20 | Male | FUO, jaundice, abdominal pain, CA 19-9↑ | MRI: Multiple lesions, intrahepatic bile duct was significantly dilated | Left lobe | CCC | Biopsy, patient declined operation, PTCD | Spindle cells proliferation and infiltration by mixed inflammatory cells, ALK+, SMA+ | NM |

| Jin et al[5], 2017 | 1 | 42 | Female | Fatigue, fever, pale conjunctivae; Hb↓, Lc↑ | U/S: Hypoechoic mass with unclear border; CT: Low density lesion with mild enhancement | Right lobe | Liver abscess | Right posterior segmentectomy | Chronic inflammatory cells, spindle cells; CD68+, smooth muscle actin, ALK- | No recurrence after 32 mo |

| Mulki et al[22], 2015 | 1 | 50 | Male | Abdominal pain, anorexia, mild fever, hepatomegaly | U/S: 2 hypodense masses, CT: + hepatic vein thrombus | Right lobe | Abscess with septic thrombus | Initial treatment: Biopsy, pigtail, antibiotics, secondary operation | Plasma cells, inflammatory cells, ALK, IgG4+ | No residual disease |

| Obana et al[25], 2015 | 1 | 69 | Male | FUO, CA 19-9 48 ng/mL (n: < 37 ng/mL), Diabetes mellitus II, Dyslipidemia, hypertension | U/S: Irregularly shaped, low-echoic mass; CT: Peripherally enhanced, MRI: T1W, central portion hyperintense | Right lobe Seg VI | CCC/HCC | Partial hepatectomy | Whitish-yellow mass 2 cm in size , inflammatory cell infiltrates, cholesterol cleft granuloma with focal abscess were observed in the central compartment , IgG4 - | NM |

| Guerrero Puente et al[26], 2015 | 1 | 75 | Male | Weight loss, fever, intermittent night sweat, abdominal pain, CRP↑, leukocytosis, cholestasis hypertension, hypercholesterinemia | CT: 8 cm heterogeneous focal lesion, portal branch thrombosis, lymphadenopathy; MRI: T2W isointense, T1W discretely hypointense, cystic–necrotic areas, perilesional edema | Left lobe | Inflammatory disease | CT-guided biopsy followed by antibiotic therapy | Inflammatory pseudotumour, vimentin+, AML+, desmin−, CD68−, ALK−, with no light chain restriction and a low proliferative index (15%) | Partial remission after 1 mo, almost complete remission after 6 mo |

| Onieva-González et al[27], 2015 | 1 | 70 | Male | Low-grade fever, asthenia, weight loss and oligoarthritis, lung tuberculosis, diabetes, gouty arthritis, renal lithiasis and colon diverticulitis | CT: Thickened gallbladder wall, poorly-defined hypodense lesion of 17 mm in the gallbladder bed, U/S: Nodule; MRI: Hypointense in T2 sequences; PET: No metabolism | Seg. V | Liver abscess | Antibiotic therapy, after 4 mo later fine needle biopsy followed by laparoscopic biopsy and cholecystectomy with the lesion in the gallbladder bed | Lymphoid infiltration without malignancy signs, compatible with an inflammatory pseudotumour | NM |

| Chang et al[50], 2014 | 1 | 38 | Male | Fatigue, abdominal distension and weight loss, jaundice, hepatomegaly, bilateral ankle edema | U/S: Complex mass; CT: Large cystic or necrotic mass; MRI: T2W: Cystic portion hyperintense to liver parenchyma, surrounded by a hypointense rim. T2W: Hyperintense compared to liver parenchyma | Bilateral | N/A | Ultrasound-guided and open biopsy, followed by resection | Cellular spindle-cell proliferation with heavy inflammatory infiltrate consisting primarily of plasma cells and lymphocytes | Recurrence |

| You et al[35], 2014 | 1 | 43 | Male | Chronic cough, right-upper-quadrant pain, anorexia for 3 mo, leukozytosis, elevated platelet count | U/S: 18 cm mass with slightly echogenic center; MRI: Large mass with central dark area and some peripheral spokes; CT: Mass, 20 cm × 17 cm × 18 cm, with extensions into the medial segment of the left hepatic lobe, hypervascular nodular area with enhanced density at the periphery and hypoattenuating density centrally | Right lobe | Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma or CCC | Percutaneous needle core biopsy > NM | Bland spindle cell proliferation amidst small mature lymphocytes, numerous plasma cells, histiocytes, and few neutrophils. Spindle cells showed a storiform pattern with large areas of necrosis; cytokeratin (CAM 5.2) -, cytokeratin 5/6 -, actin-, CD34-, CD117-, DOG-1-, desmin-, CD68-, S100-, Pan-melanoma-. Spindle cells were negative for CD21, CD23, CD35, ALK-1. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA in situ hybridization (EBER) showed large numbers of Epstein-Barr virus positive cells, including some spindle cells | NM |

| Durmus et al[36], 2014 | 1 | 67 | Female | Moderate diffuse abdominal tenderness, focus over epigastrium | U/S: Heterogeneous hypoechogenic tumor; CT: Contrast enhancing mass with irregular confluent non-enhancing areas in the center with a hypodense late enhancing rim and no wash-out in the late phase, MRI: In T1W hypointense borders, well defined without fatty components. T2W showed a heterogeneous slightly hyperintense lesion with an ill-defined hyperintense rim | Segment IV | Malignancy | Left hemihepatectomy with partial excision of the adherent abdominal wall and diaphragm | Tumor with fibrosis and partially necrotic tissue infiltrated by inflammatory cells, predominantly plasma cells, and also pigmented macrophages and granulocytes | NM |

| Wong et al[37], 2013 | 1 | 56 | Female | Right-upper-quadrant abdominal pain, renal transplant | U/S: 2 cm × 2.4 cm mass in the left hepatic lobe with associated biliary duct dilatation, MRI: atrophic left liver lobe with multiple strictures and distal duct dilatation. 2-cm lesion at the origin of the left hepatic duct | Left lobe | Primary hepatic tumor | Surgical resection | Dense hyalinised stroma and scattered, histiocytic and lymphocytic inflammation | NM |

| Kruth et al[38], 2012 | 1 | NM | NM | FUO CRP↑ | Gastroscopy, CT lung and abdomen, MRI: 3.3 cm lesion | Seg. VI | Adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia or HCC | Surgical resection | NM | No recurrence after 1 yr |

| Chablé-Montero et al[39], 2012 | 1 | 23 | Female | Fever, diaphoresis, right-upper-quadrant abdominal pain | U/S and CT: Heterogenous rounded hepatic lesion of 7 cm in greatest dimension | Right lobe | Pyogenic hepatic abscess | Antibiotics, later right hepatic lobectomy | Grossly a non-encapsulated but well demarcated hepatic tumor with central necrosis of 11 cm in greatest dimension; microscopically: Spindle myofibroblastic cells arranged in fascicles. Leukocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells, SMA+ | NM |

| Kayashima et al[30], 2011 | 1 | 57 | Female | Asymptomaticlaparoscopic calculous cholecystectomy 3 yr ago | U/S: 3 liver masses, CT: 1 intra- and 2 extrahepatic lesions; MRI: three high‐intensity lesions; PET: Abnormal accumulation in all lesions | Right lobe | CCC | Surgical resection (tiny black‐colored nodules within the abdominal cavity and spilled gallstones) | Inflammatory granuloma located at liver parenchyma | No recurrence after 6 mo |

| Huang et al[40], 2012 | 1 | 30 | Male | Right upper abdominal pain; CEA↑; 2 yr after renal transplant | CT: Low-density mass, about 30 mm in diameter, well defined, and with peripheral enhancement | Caudate lobe | HCC or liver abscess | Hepatic caudate lobectomy with complete resection of the mass | Mixture of spindle-shaped myofibroblastic cells and chronic inflammatory cells; SMA+ | NM |

| Beauchamp et al[41], 2011 | 1 | 74 | Female | FUO | CT: Numerous hypodense lesions scattered throughout the liver | NM | NM | Liver biopsy | IMT | NM |

| Al-Jabri et al[29], 2010 | 1 | 69 | Male | Right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting, recent weight loss, rheumatoid arthritis and bronchiectasis, CRP↑, cholestasis (normal Bili) | U/S: Ill-defined area, CT: multiple low attenuation lesions | Right lobe | Cholecystitis, malignancy | Fine needle biopsy | Presence of benign hepatocytes, acellular debris and a mixture of acute and chronic inflammatory cells | No recurrence after 3 mo |

| Salakos et al[43], 2010 | 1 | 10 | Male | Fever, weight loss, fatigue, tachycardia, hepatomegaly, leukocytosis, platelet count ↑ | U/S: Space occupying lesion in the liver; CT: Large lesion with sold and cystic parts and heterogenous enhancement | Right and left lobe | NM | Biopsy followed by conservative treatment (ceftriaxone, clindamycin, NSAR) | Hyperplastic cholangioles, myofibroblasts and fibroblasts, infiltrate of lymphocytes, eosinophils and neutrophils; ALK+ | Partial response after 2 mo, complete response |

| Ueda et al[45], 2009 | 1 | 79 | Male | Leukocytosis | U/S: Hypoechoic lesion, 3 cm in diameter, with several stones. CT: Low density area in segment V; MRI: Lesion of slightly low signal intensity; MRCP: Lesion of moderate-to-high signal intensity on T2W | Right lobe | Inflammation due to cholangitis with intrahepatic bile duct stones | 1. ERCP: Sphincterotomy, antibiotics because of common bile duct stone; 2. Relapse of symptoms 4 wk later > resection | Grossly gray, fibrotic, solid tumor, intrahepatic bile duct stones. Proliferation of diffuse myofibroblastic and mesenchymal cells in a mixed myxoedematous, dense fibrotic stroma, with many small vessels and marked infiltration by various acute and chronic inflammatory cells | No recurrence after 18 mo |

| Sürer et al[7], 2009 | 1 | 48 | Female | Weakness, fever, weight loss, right upper abdominal pain, Lc-, neutrophil 75.3%, liver function normal | U/S: Single hypoechoic lesion in right lobe | Right lobe | NM | Resection | No capsule, light brown, no necrosis, spindle cells, granulation-tissue type vessels, chronic inflammatory cells on loose, edemateous, myxoid stroma, CD 38+, SMA+, ALK+, desmin, EMA- | 2 yr no recurrence after 2 yr |

| Manolaki et al[47], 2009 | 1 | 9 | Female | Fever, mild anorexia, intermittent epigastric pain | U/S: Hypoechoic lesion, lymph node at porta hepatis, CT: hypodense space-occupying lesion | Left lobe | NM | Biopsy, secondary left lateral segmentectomy with lymph node excision | Pale and firm lesion (3.5 cm × 2.5 cm × 3.0 cm) with whitish solid infiltrations extending to the capsule of the liver. Proliferation of spindle-shaped cells arranged in short fascicles with an ill-defined mark. Inflammatory cells, predominantly lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils; vimentin+, SMA+, CD68+,TBC+ | No recurrence after 3 yr |

CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; FUO: Fever unknown origin; CRP: C-reactive protein; CCC: Cholangiocarcinoma; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; PTCD: Percutaneous transhepatic cholangio drainage; NM: Not mentioned; U/S: Ultrasonography; Hb: Haemoglobin; LC: Leukocytes; TC: Thrombocytes; T1W: T1-Weighted; T2W: T2-Weighted; Chron Hep B: Chronic Hepatitis B; Seg: Segment; ↑: Increase; ↓: Decrease; WBC : Wight blood cells; SMA: Smooth muscle actin; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Table 2.

Clinical studies of > 2 patients

| Ref. | n | Age (yr) | Gender | Clinical and laboratory findings | Radiology | Localization | Tentative diagnose | Treatment | Histology | Follow up |

| Park et al [28], 2014 | 45 | 65 (29-84) | Male/female (26/19) | Abdominal pain (n = 16) fever (n = 11), malaise (n = 5) weight loss (n = 4); CRP↑ (n = 31), leukocytosis (n = 10), CEA (n = 1) CA 19-9 (n = 1); hypertension, tuberculosis, chronic Hepatitis B | CT scan: Hypo-attenuating lesions in 40 patients, MRI: Low signal intensity lesion at T1W image in 86.4% and relatively homogenous high signal intensity lesion at T2W image in 76.2% | Right lobe (n = 27), left lobe (n = 14), both (n = 4) | Malignancy (n = 26, 57.8%), abscess (n = 11, 24.4%) | Percutaneous needle biopsy (n = 35), surgical resection (n = 9), both (n = 1) | Chronic infiltration of various inflammatory cells (plasma cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils) and fibrous stroma | No recurrence after median follow-up of 8 mo |

| Ahn et al [42], 2011 | 22 | 34- 76 | Male/ female (16/6) | Abdominal pain (n = 12), febrile (n = 5), malaise (n = 1), asymptomatic (n = 4), leucocytosis (n = 6), hyperbilirubinaemia (n = 3), alkaline phosphatase↑ (n = 10), liver enzymes ↑ (n = 5), CA 19-9 ↑ (n = 5), AFP↑ (n = 1) ; associated biliary disease (n = 15), malignancy (n = 4) | Solitary (n = 17); multiple (n = 5), median size 3 cm (1.1-9.6 cm), non-enhanced CT: Hypoattenuating lesions (n = 22), enhanced CT: Central hypoattenuating areas and a delayed hyperattenuating periphery (n = 18), multiseptate appearance with hyperattenuating internal septa and periphery (n = 3), hypoattenuation up to the equilibrium phase (n = 1) | Right lobe n = 10, left lobe n = 9, both n = 3, (mostly seg. IV n = 12) | IPT (n = 12), malignancy (n = 4), recurrence of malignancy (n = 2), abscess (n = 4) | Percutaneous needle biopsy (n = 18), incisional biopsy (n = 1) --> surgical resection (n = 3); liver resection (n = 3) without prior biopsy, 16 patients conservatively, 6 patients with surgical resection | Histiocytic cell infiltration with negative IgG4 (n = 17), lymphoplasmacytic type (n = 5) with positive IgG4 (n = 4) | Post conservative treatment: 10 complete remission after 15 mo; 5 partial remission after 4 mo, post resection: Mortality n = 2 (myocardial infarction, peritoneal seeding) |

| Geramizadeh et al [44], 2009 | 2 | 14 | Male | Chills, fever, anorexia > 8 kg weight, leukocytosis | CT: Well-defined heterogeneous mass with central areas of necrosis and a slightly hyperdense rim | Left lobe | Abscess | Resection | Creamy grey mass with a vague whorling appearance. Plasma cells with varying degrees of fibroblastic proliferation admixed with lymphocytes, eosinophils and macrophages | No recurrence after 1 yr |

| 15 | Male | Hepatitis B positive, weight loss | Well defined liver mass | NM | Malignancy | Fine needle biopsy | 6 cm liver mass, fibroblastic proliferation, many plasma cells and eosinophils | No recurrence after 2 yr | ||

| Yamaguchi et al [17], 2007 | 3 | 52 | Male | Epigastric pain, appetite loss, weight loss, fever | U/S and CT: Hepatic mass in left lobe | Left lobe | IPT | Follow up | NM | Complete remission after 1 yr |

| 58 | Male | Auxiliary finding | CT: Low density mass in the right lobe enhanced during the delayed phase | Right lobe | CCC | Biopsy > no treatment, follow up | IMTL | NM | ||

| 57 | Female | Sigmoid cancer planned for resection | MRI: 2 metastases with low-intensity signal on T1, a slightly high-intensity signal on T2 | Right lobe | Hepatic metastasis | Intraoperative right portal vein embolization | NM | NM | ||

| Milias et al[46], 2009 | 4 | 35 | Male | Abdominal and bone pain, fatigue, malaise, hematuria, WBC↑ | CT: Liver abscess right upper abdominal quadrant | Right lobe | Liver abscess | Drainage followed by right hepatectomy | Many plasma cells, densely collagenous bundles between a plasma cell-rich infiltrate | NM |

| 56 | Male | Right upper abdominal pain, malaise | CT: Liver abscess | Right lobe | Liver abscess | Drainage followed by right hepatectomy | Inflammatory response to hepatic abscess | |||

| 75 | Female | Moderate upper quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting | U/S: Cystic lesion, CT: Cystic lesion, slight dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts | IVB | Cholangitis/ Cystadenoma | Biopsy followed by Seg. IVB resection | Central granulation, fibrosis and chronic lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, no features of neoplasia. Inflammatory pseudotumor | |||

| 47 | Female | Right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, fever, pruritus | CT: Marked dilatation of the intrahepatic biliary tree | Right lobe | CCC | Seg. III resection, secondary right hepatectomy | Widespread chronic inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and plasma cells, numerous lipid-laden macrophages, no malignancy |

CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; FUO: Fever unknown origin; CRP: C-reactive protein; CCC: Cholangiocarcinoma; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; PTCD: Percutaneous transhepatic cholangio drainage; NM: Not mentioned; U/S: Ultrasonography; Hb: Haemoglobin; LC: Leukocytes; TC: Thrombocytes; T1W: T1-Weighted; T2W: T2-Weighted; Chron Hep B: Chronic Hepatitis B; Seg: Segment; ↑: Increase; ↓: Decrease; WBC: Wight blood cell.

We herein report the case of a 32-year-old woman who received an immediate hepatic resection for a large IMTL causing intermittent fever 4 mo postpartum.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 32-year old woman presented herself to her family doctor with intermittent fever, unclear blood loss, malaise and pain in the right flank 4 mo postpartum.

History of present illness

The patient reported that the symptoms began 4 mo after she gave birth to her healthy child. She complaint about fatigue and right upper quadrant abdominal pain. She had recurrent episodes of fever up to 38.5 °C, but no jaundice or pruritus.

History of past illness

There was no significant history of past illnesses.

Personal and family history

Personal and family history was unremarkable. She gave birth to a healthy child 4 mo before she was treated at our institution.

Physical examination upon admission

Vital signs were within the normal range, body temperature was 38.5 °C. On examination, the patient had a right upper quadrant tenderness, without jaundice or hepatosplenomegaly.

Laboratory examinations

Urine and most blood analyses were without any pathological findings including a normal liver function and normal ferritin levels. While the white blood cell count was normal, CRP was elevated to 181 mg/L. The liver enzymes (aspartate-aminotransferase 31 U/L, alkalic-aminotransferase 49 U/L) and cholestasis parameters (alkalic-phosphatase 466 U/L, y-glutamyl transferase 424 U/L) showed an increase while the serum bilirubin (6 μmol/L) stayed normal.

Imaging examinations

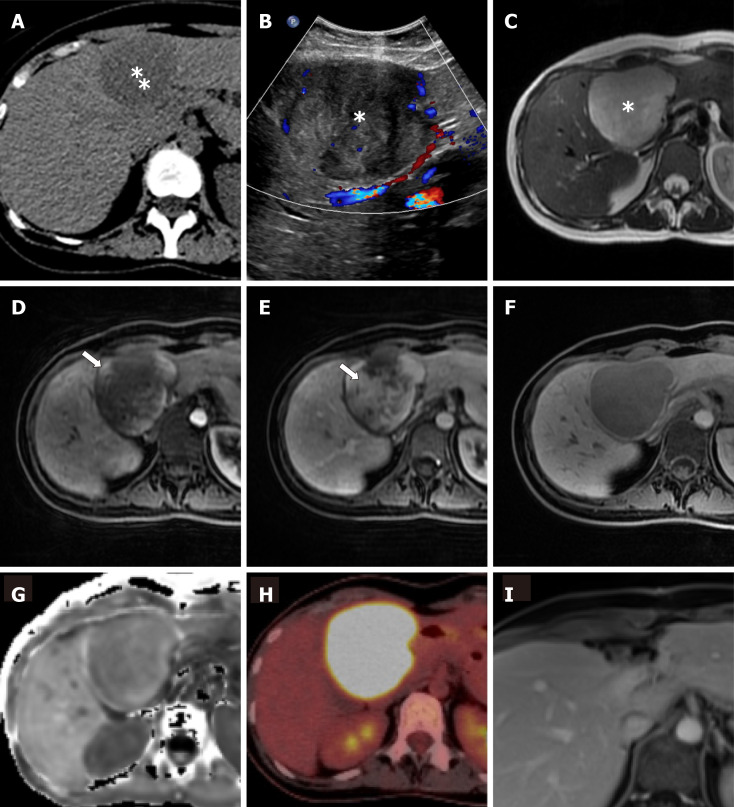

An ultrasound of the abdomen (Figure 1A) revealed a round, encapsulated liver lesion in segment IVa/b of unclear dignity, a non-contrast computed tomography of the abdomen ruled out urolithiasis, but confirmed the suspicious lesion of 8 cm in the liver as an incidental finding. The computer tomography (CT) and, same day magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the upper abdomen (Figure 1B-F) showed an 8 cm × 8 cm tumor in segment IVa/b of the liver suspected to be a liver adenoma. Additional serological tests for hepatitis, the tumor markers carbohydrate-antigen 19-9 and alpha-fetoprotein, and markers for echinococcosis were all negative. After discussion of the case in our interdisciplinary liver tumor board on the next day, we performed a positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) which showed the known lesion as a metabolically active tumor resembling an inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver or a malignant tumor of unclear origin. No other lesions was detected in any of the performed scans.

Figure 1.

Imaging features within the liver lesion in segment IV. A: The lesion was a first detected as an incidental finding in an unenhanced abdominal computed tomography to rule out kidney stones (asterisk); B: Conformed with an ultrasound examination (asterisk); C: In a following magnetic resonance imaging the lesion showed a homogeneous high signal in T2-weighted imaging (asterisk); D: After the application of intravenous hepatocyte specific contrast medium (gadoxetic acid, Primovist®/Eovist®, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Leverkusen, Germany) there was an early enhancement at the rim in the arterial phase (arrow); E: Followed by a strong enhancement in the venous phase (arrow); F: In the hepatobiliary phase after 20 min, the lesion appeared with a low intracellular uptake of the contrast medium compared with the adjacent liver tissue; G: In the diffusion-weighted imaging there was no clear diffusion restriction detection within the lesion (apparent diffusion coefficient); H: In an additional positron emission tomography-computed tomography examination the lesion showed an intensively increased tracer uptake; I: A follow-up magnetic resonance imaging examination after 3 mo confirmed a complete surgical resection (with multiple artifacts at the resection margin due to multiple clips) and ruled out new hepatic lesions.

Further diagnostic work-up

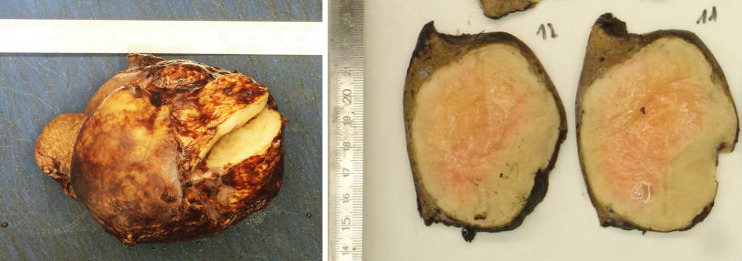

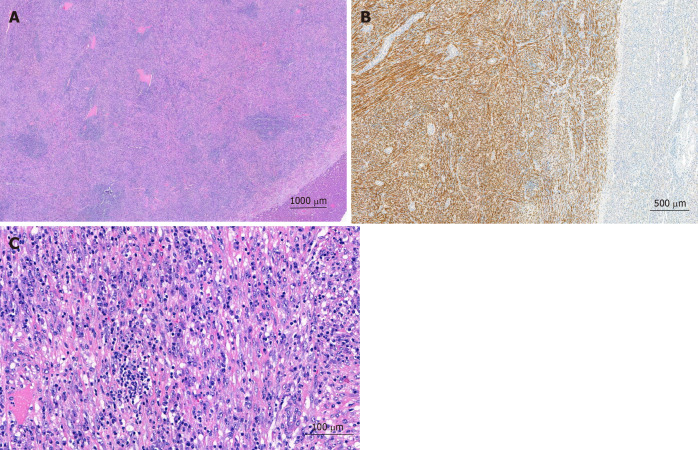

The pathologist macroscopically (Figure 2) described the size of the resected specimen as wedge-shaped and nodular, 9.5 cm × 7.0 cm × 7.5 cm. The capsule of the liver was about unremarkable on one-half of the supplement. An area of 7.5 cm × 7.5 cm × 6.2 cm was sharply circumscribed, whitish/creamy and fibrous. No clearly definable capsule. The remaining liver tissue was inconspicuous and showed no further hereditary findings. The total weight of the tumor was 198 g. Immunohistochemistry showed a clear expression of cytoplasmic ALK and a weak expression of smooth muscle actin. Cytokeratin-PAN (CK Pan), Cytokeratin 18 (CK18), signal transducer and activator of transcription protein 6 (STAT6), Desmin, tyrosin-protein (C-kit), discovered on gastrointestinal stromal tumors 1 (DOG1), ETS related gene (ERG), family of calcium binding protein (S100) and SRY-related HMG-box 10 Protein (SOX10) showed no expression. The intra-tumoral immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-positive plasma cells were slightly increased, but displayed only a very small percentage of all plasma cells (Figure 3). The pathological diagnosis revealed an IMTL with no fibrosis and no malignancy.

Figure 2.

Postoperative macroscopic pathology of the inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors.

Figure 3.

Postoperative microscopic pathology of the inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. A: Well demarcated firm vascularized tumor mass with spotty inflammatory infiltrate; B: Bland proliferation of spindle cells in broad fascicles at higher magnification. Scattered lymphocytes and plasma cell; C: Intense positivity of the spindel cells for anaplastic lymphoma kinase.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis of the presented case is an IMTL.

TREATMENT

Due to the unclear situation with fever and the suspicion of a large adenoma or malignant tumor of the liver, an immediate surgical resection was performed. Intraoperatively, the solitary central lesion could be confirmed by intraoperative ultrasound, which also excluded additional liver lesions. An open resection of the liver segment IVa/b was performed achieving a negative resection margin. While no intra-operative complications occurred, the patient developed a bilioma, which had to be drained interventionally 7 d after the surgery accompanied by an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with stent insertion.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The case was discussed postoperatively in our interdisciplinary liver tumor board to determine the postoperative management. While no adjuvant therapy was indicated, it was recommended to follow the patient clinically by MRI imaging every 3 mo after the surgery for the duration of at least one year.

The patient returned to work and MRIs of the liver 3, 6 and 12 mo after resection showed no local recurrence and no novel liver lesions.

DISCUSSION

We herein present and discuss the case of a 32-year-old woman who presented with a suspicious and symptomatic liver mass consequently diagnosed as IMTL.

IMTs of the liver are extremely rare findings that can sometimes mimic malignant lesions[6]. In terms of demographics, the tumor seems to be more common in men than in women (M/F: 1.5/1) with a mean age at diagnosis of 37 years[7]. IMTL usually occur in the right liver lobe, in close proximity to the gallbladder or central biliary system[7,8]. Typical clinical findings reported in the literature are fever, abdominal pain, lack of strength and weight loss[7], which all occurred in our case (intermittent fever, unclear blood loss, malaise and pain in the right flank) and led to the ultimate diagnosis. In addition to the fever, laboratory findings often suggest inflammation due to leukocytosis, neutrophilia and elevated CRP[5,6,8,10]. More rarely, anemia and sometimes also elevated liver enzymes are reported[6]. According to the clinical signs of infection, some individual cases were reported to be correlated with different active (virus) infections[5,18,19,21,22]. In our patient, the antibody to Epstein-Barr virus was positive in the serological findings without any signs of an active Epstein-Barr virus infection. A clear association between IMT and infectious organisms seems to be doubtful since in most reported series, including our own case, no acid-fast organisms, fungi, parasites or bacteria could be identified in the tumor[10,19].

Radiological features of IMTLs are nonspecific and a definite radiological diagnosis seems to be impossible. Due to the small cases (Tables 1 and 2) we could see, that the tumor in ultrasonography mostly was hypoechogenic. An IMT may be suspected if a defined soft tissue mass and a heterogeneous enhancement with invasive or non-invasive growth are present on adjacent structures in CT or MRI[6,8,23]. Not all patients underwent a MRI for diagnostic treatment, only in eight cases[17,24-29]. Al-Hussaini et al[24] and Kayashima et al[30] described a contrast-enhancing, hyper-intense well defined lesion without going into details. In four cases the lesion in T1W was mostly hypointense and T2W hyperintense[17,25,26,28]. Despite its rarity, lack of diagnostic signs and symptoms, IMTL should not be ruled out as a differential diagnosis in liver lesions like focal nodular hyperplasia, hepatocellular adenoma, carcinoma and ecchinococcosis especially in young patients with normal tumor markers[7]. In addition IMTL can sometimes mimic a liver abscess[22]. Although many synonyms have been used for this lesion, including plasma cell granuloma, postinflammatory tumor, xanthomatous pseudotumor, inflammatory pseudotumor, and inflammatory fibrosarcoma[31], the new classification clearly suggests the term inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of its suitable origin or organ, in our case an IMTL[4].

Due to the small number of cases worldwide (Tables 1 and 2), no clear diagnostic tests or radiographic features exist that help to make a definite diagnosis without a histopathological examination of the tissue[10]. We performed a comprehensive literature search and studied the cases published during the last 10 years[5,7,17,24-30,32-47]. There were more men affected than women. The most common localization of the tumor was on the right lobe of the liver. All patients in the described cases had at least an ultrasonography and/or a CT. In some cases, the diagnostic work-up was completed with MRI, MRCP or PET-CT. Due to the different radiological findings the tentative diagnose showed a large variation from liver abscess, inflammatory process and also malignancy.

In the gross examination of the resected specimen, most findings showed the similar finding of a well-demarcated, unencapsulated, yellow-whitish mass. Histologically infiltrations of chronic inflammatory-cells like lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and macrophages were often described. Whenever immunohistochemical analyses were performed, ALK expression showed a similar distribution. The performed treatment of the different cases varied according to the initially suspected diagnose. In summary, more patients were treated conservatively, although there is no clear indication for such a treatment. Surgical resections were performed according to the size and location of the suspected tumor and varied from small atypical resections to major hepatectomies. In most of the cases the definite histology report of the resected specimen then showed the diagnosis of an IMTL-Unfortunately, follow-up was not described in all published cases. Except for one reported recurrence after 2.5 years, most patients stayed tumor-free during a follow-up ranging from X-Y months[48].

Surgical resection is usually recommended so that a proper pathological work-up can be performed and malignancy can be ruled out. Nevertheless, several different treatment strategies have been published including conservative approaches with steroids, high-dose steroids, radiation and chemotherapy[6-8,11]. Interestingly, one case with a spontaneous regression has also been reported[17]. A typical pathological finding is that the IMTL’s are unencapsulated. They are usually solid or gelatinous on the intersection and have a white color. Hemorrhage, calcification or necrosis are rarely described[6,12], similar to the pathological findings in our case. As described by Elpek et al[6], chromosomal translocations leading to the activation of ALK can be detected in IMTLs. Although immunohistochemistry for ALK expression in immunohistochemistry can reliably predict the presence of ALK gene rearrangement, its prognostic relevance is still unclear[14,49]. IMTLs differ from IgG4-related liver disease in terms of ALK expression, low IgG4 positive cell infiltration, and lack of obstructive phlebitis[6].

The natural course of IMTL without curative surgical therapy is unclear. To date, only a few cases have been described in which patients had local recurrence or metastases after liver resections[15,16,48]. Due to the small numbers published worldwide, no recommendations for the follow-up are available and patients is treated according to the decisions made in the local interdisciplinary tumor boards. In our case, the finding of the pseudotumor was 4 mo postpartum. Due to the rather large size of the lesion it was considered an advanced lesion. The pregnancy may have masked general symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. So far, only one case of newly diagnosed IMTL has been reported during pregnancy[18].

CONCLUSION

In summary of the literature and with the experience from our own recent case, complete surgical resection of a suspected IMTL should be the preferred treatment of choice in order to rule out malignancy, avoid long-term medical treatment and to be able to recommend an appropriate follow-up for the patient.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: November 29, 2019

First decision: December 12, 2019

Article in press: March 11, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Switzerland

Peer-review report´s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Luo GH, Tajiri K S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu YXJ

Contributor Information

Alexandra Filips, Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Bern 3010, Switzerland.

Martin H Maurer, Department of Radiology, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Bern 3010, Switzerland.

Matteo Montani, Institute of Pathology, Inselspital, University Hospital, University Bern, Bern 3010, Switzerland.

Guido Beldi, Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Bern 3010, Switzerland.

Anja Lachenmayer, Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Bern 3010, Switzerland. anja.lachenmayer@insel.ch.

References

- 1.Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor). A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:859–872. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coffin CM, Humphrey PA, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a clinical and pathological survey. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1998;15:85–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook JR, Dehner LP, Collins MH, Ma Z, Morris SW, Coffin CM, Hill DA. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) expression in the inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a comparative immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1364–1371. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher CD, Unni KK, Mertens F. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. In: Kleihues P, Sobin LH, editors. In: Kleihues P, Sobin LH. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC, 2002: 120-122. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin YW, Li FY, Cheng NS. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: An unusual hepatic tumor mimicking liver abscess. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41:243–245. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elpek GÖ. Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor of the Liver: A Diagnostic Challenge. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2014;2:53–57. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2013.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sürer E, Bozova S, Gökhan GA, Gürkan A, Elpek GO. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver: a case report. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2009;20:129–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koea JB, Broadhurst GW, Rodgers MS, McCall JL. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: demographics, diagnosis, and the case for nonoperative management. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:226–235. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang L, Lai EC, Cong WM, Li AJ, Fu SY, Pan ZY, Zhou WP, Lau WY, Wu MC. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver: a cohort study. World J Surg. 2010;34:309–313. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakai M, Ikeda H, Suzuki N, Takahashi A, Kuroiwa M, Hirato J, Hatakeyama Si, Tsuchida Y. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:663–666. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.22316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Locke JE, Choti MA, Torbenson MS, Horton KM, Molmenti EP. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:314–316. doi: 10.1007/s00534-004-0962-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: comparison of clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:509–520. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213393.57322.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang X, Miao R, Yang H, Chi T, Jiang C, Wan X, Xu Y, Xu H, Du S, Lu X, Mao Y, Zhong S, Zhao H, Sang X. Retrospective and comparative study of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:885–890. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen ST, Lee JC. An inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in liver with ALK and RANBP2 gene rearrangement: combination of distinct morphologic, immunohistochemical, and genetic features. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1854–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zavaglia C, Barberis M, Gelosa F, Cimino G, Minola E, Mondazzi L, Bottelli R, Ideo G. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver with malignant transformation. Report of two cases. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1996;28:152–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pecorella I, Ciardi A, Memeo L, Trombetta G, de Quarto A, de Simone P, di Tondo U. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver--evidence for malignant transformation. Pathol Res Pract. 1999;195:115–120. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(99)80083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamaguchi J, Sakamoto Y, Sano T, Shimada K, Kosuge T. Spontaneous regression of inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: report of three cases. Surg Today. 2007;37:525–529. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maze GL, Lee M, Schenker S. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver and pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:529–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.890_s.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto H, Kohashi K, Oda Y, Tamiya S, Takahashi Y, Kinoshita Y, Ishizawa S, Kubota M, Tsuneyoshi M. Absence of human herpesvirus-8 and Epstein-Barr virus in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with anaplastic large cell lymphoma kinase fusion gene. Pathol Int. 2006;56:584–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dishop MK, Warner BW, Dehner LP, Kriss VM, Greenwood MF, Geil JD, Moscow JA. Successful treatment of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with malignant transformation by surgical resection and chemotherapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:153–158. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200302000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheuk W, Chan JK, Shek TW, Chang JH, Tsou MH, Yuen NW, Ng WF, Chan AC, Prat J. Inflammatory pseudotumor-like follicular dendritic cell tumor: a distinctive low-grade malignant intra-abdominal neoplasm with consistent Epstein-Barr virus association. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:721–731. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulki R, Garg S, Manatsathit W, Miick R. IgG4-related inflammatory pseudotumour mimicking a hepatic abscess impending rupture. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-211893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.1 Tan H, Wang B, Xiao H, Lian Y, Gao J. Radiologic and Clinicopathologic Findings of Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2017;41:90–97. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Hussaini H, Azouz H, Abu-Zaid A. Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor presenting in an 8-year-old boy: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8730–8738. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i28.8730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obana T, Yamasaki S, Nishio K, Kobayashi Y. A case of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor protruding from the liver surface. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2015;8:340–344. doi: 10.1007/s12328-015-0605-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guerrero Puente L, Muñoz García-Borruel M, Barrera Baena P, de la Mata García M. [Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: A propos of a case] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:329–331. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onieva-González FG, Galeano-Díaz F, Matito-Díaz MJ, López-Guerra D, Fernández-Pérez J, Blanco-Fernández G. [Inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver. Importance of intra-operative histopathology] Cir Cir. 2015;83:151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.circir.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park JY, Choi MS, Lim YS, Park JW, Kim SU, Min YW, Gwak GY, Paik YH, Lee JH, Koh KC, Paik SW, Yoo BC. Clinical features, image findings, and prognosis of inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: a multicenter experience of 45 cases. Gut Liver. 2014;8:58–63. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2014.8.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Jabri T, Sanjay P, Shaikh I, Woodward A. Inflammatory myofibroblastic pseudotumour of the liver in association with gall stones - a rare case report and brief review. Diagn Pathol. 2010;5:53. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-5-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kayashima H, Ikegami T, Ueo H, Tsubokawa N, Matsuura H, Okamoto D, Nakashima A, Okadome K. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver in association with spilled gallstones 3 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of a case. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2011;4:181–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-5910.2011.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pettinato G, Manivel JC, De Rosa N, Dehner LP. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (plasma cell granuloma). Clinicopathologic study of 20 cases with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural observations. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94:538–546. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/94.5.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe J, Yamada S, Sasaguri Y, Guo X, Kurose N, Kitada K, Inagaki M, Iwagaki H. A Surgical Case of Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor of the Liver: Potentially Characteristic Gross Features. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2019;13:1179554919829498. doi: 10.1177/1179554919829498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu J, Xiong XZ, Cheng NS. Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic: Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver mimicking intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with hilar lymph node metastasis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:312. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H, Shen Q, Xia Q, Shi S, Zhang R, Yu B, Ma H, Lu Z, Wang X, He Y, Zhou X, Rao Q. [Clinicopathologic features of extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor] Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2014;43:370–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.You Y, Shao H, Bui K, Bui M, Klapman J, Cui Q, Coppola D. Epstein-Barr virus positive inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: report of a challenging case and review of the literature. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2014;44:489–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durmus T, Kamphues C, Blaeker H, Grieser C, Denecke T. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver mimicking an infiltrative malignancy in computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging with Gd-EOB. Acta Radiol Short Rep. 2014;3:2047981614544404. doi: 10.1177/2047981614544404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong JS, Tan YM, Chung A, Lim KH, Thng CH, Ooi LL. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver mimicking cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2013;42:304–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kruth J, Michaely H, Trunk M, Niedergethmann M, Rupf AK, Krämer BK, Göttmann U. A rare case of fever of unknown origin: inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver. Case report and review of the literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2012;75:448–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chablé-Montero F, Angeles-Ángeles A, Albores-Saavedra J. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11:708–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang YH, Zhong DJ, Tang J, Han JJ, Yu JD, Wang J, Wan YL. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver following renal transplantation. Ren Fail. 2012;34:789–791. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2012.673446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beauchamp A, Villanueva A, Feliciano W, Reymunde A. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver in an elderly woman following a second liver biopsy: a case report. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2011;103:60–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahn KS, Kang KJ, Kim YH, Lim TJ, Jung HR, Kang YN, Kwon JH. Inflammatory pseudotumors mimicking intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma of the liver; IgG4-positivity and its clinical significance. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:405–412. doi: 10.1007/s00534-011-0436-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salakos C, Nikolakopoulou NM, De Verney Y, Tsamandas AC, Ziambaras T, Petsas T, Papanastasiou DA. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) positive inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: conservative treatment and long-term follow-up. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2010;20:278–280. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geramizadeh B, Tahamtan MR, Bahador A, Sefidbakht S, Modjalal M, Nabai S, Hosseini SA. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: two case reports and a review of the literature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:210–212. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.48920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ueda J, Yoshida H, Taniai N, Onda M, Hayashi H, Tajiri T. Inflammatory pseudotumor in the liver associated with intrahepatic bile duct stones mimicking malignancy. J Nippon Med Sch. 2009;76:154–159. doi: 10.1272/jnms.76.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Milias K, Madhavan KK, Bellamy C, Garden OJ, Parks RW. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the liver: experience of a specialist surgical unit. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1562–1566. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manolaki N, Vaos G, Zavras N, Sbokou D, Michael C, Syriopoulou V. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in an immunocompetent girl. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:451–454. doi: 10.1007/s00383-009-2361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang SD, Scali EP, Abrahams Z, Tha S, Yoshida EM. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: a rare case of recurrence following surgical resection. J Radiol Case Rep. 2014;8:23–30. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v8i3.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mergan F, Jaubert F, Sauvat F, Hartmann O, Lortat-Jacob S, Révillon Y, Nihoul-Fékété C, Sarnacki S. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in children: clinical review with anaplastic lymphoma kinase, Epstein-Barr virus, and human herpesvirus 8 detection analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1581–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang AI, Kim YK, Min JH, Lee J, Kim H, Lee SJ. Differentiation between inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor and cholangiocarcinoma manifesting as target appearance on gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2019;44:1395–1406. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1847-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]