Abstract

BACKGROUND

The prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is significantly rising worldwide. Type-2 diabetes (T2D) is a major risk factor for NAFLD progression.

AIM

To assess the association of commonly used medications to advanced fibrosis (AF) in patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD and T2D.

METHODS

We used the International Classification of Disease 9th Revision Clinical Modification coding system to identify patients with T2D and included patients who underwent liver biopsy for suspected NAFLD between January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2015. We compared demographics, clinical characteristics, and differences in pattern of medication use in patients who had biopsy-proven AF to those without it. A univariate and multivariate analysis was performed to assess the association of different classes of medication with the presence of AF.

RESULTS

A total of 1183 patients were included in the final analysis, out of which 32% (n = 381) had AF on liver biopsy. Mean age of entire cohort was 52 years and majority were females (65%) and Caucasians (85%). Among patients with AF, 51% were on oral hypoglycemics, 30% were on insulin, 66% were on antihypertensives and 27% were on lipid lowering agents for the median duration of 19 mo, 10 mo, 26 mo, and 24 mo respectively. Medications associated with decreased risk of AF included metformin, liraglutide, lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide, atorvastatin and simvastatin while the use of furosemide and spironolactone were associated with higher prevalence of AF.

CONCLUSION

In our cohort of T2D with biopsy proven NAFLD, the patients who were receiving metformin, liraglutide, lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide, atorvastatin and simvastatin were less likely to have AF on biopsy, while patients who were receiving furosemide and spironolactone had a higher likelihood of having AF when they underwent liver biopsy. Future studies are needed to confirm these findings and to establish measures for prevention of NAFLD progression in patients with T2D.

Keywords: Diabetes medications, Anti-lipid medications, Antihypertensive medication, Fatty liver, Advanced fibrosis

Core tip: Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is increasing worldwide. Certain medications such as HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) and Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors have been shown to be associated with reduction in advanced fibrosis in patients with viral hepatitis. Patients with T2D are at a higher risk of developing advanced fibrosis. Given that these patients require lifelong medications to treat type 2 diabetes, we sought to analyze their association with biopsy proven liver fibrosis. We hope that our findings will help researchers in the future explore and design prospective studies to further enhance our understanding of this association.

INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has been emerging as one of the most important cause of liver disease worldwide, and it is likely to become a leading cause of end-stage liver disease (ESLD) in the near future[1]. The global prevalence of NAFLD has been estimated to be around 25%, affecting nearly 1.8 billion individuals worldwide[2,3], of which 51.6 million are in the United States alone, representing 21.9% of adult United States population[4]. The pathological spectrum of NAFLD can range from benign hepatic steatosis to more severe forms such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), advanced fibrosis (AF), cirrhosis, and ESLD[5]. The subtype of NAFLD characterized by NASH is a potentially progressive liver disease that can lead to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, liver transplantation, and death, and result in significant health-care and economic burden[6].

As the epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) increase worldwide, the prevalence of NAFLD is rising rapidly[6]. Recently T2D has been recognized as a major risk factor for progressive liver disease, with standardized mortality rates for cirrhosis greater than that for cardiovascular disease[7]. A study by Williamson et al[8] showed that 56.9% patients with T2D had steatosis on ultrasonography. After excluding patients with secondary cause of steatosis, prevalence of NAFLD was 42.6% in their population[8]. Independent predictors for NAFLD in their patient population were body mass index (BMI), duration of diabetes, Hemoglobin A1c, triglyceride levels, and metformin use[8]. A meta-analysis of 17 studies involving 10897 patients concluded that the overall prevalence of NAFLD among patients with T2D is significantly higher and optimal management of T2D may play a role in preventing NAFLD[9]. Patients with T2D are usually on a number of prescription medications. These include oral hypoglycemics, insulin, anti-lipid and anti-hypertensive medications. It is known that diabetes mellitus is a risk factor for AF in NAFLD, however, not all NAFLD patients with diabetes develop AF. This may be due to effects of certain medications used to treat diabetes and dyslipidemia[10]. In one study the use of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor was observed to reduce the risk of AF in chronic Hepatitis C patients[11]. There is paucity of data on the association of various medications with AF in patients with T2D, which is a well-known risk factor for advanced liver disease. The aim of this study was to assess the association of commonly used medications (anti-lipid, anti-diabetic and anti-hypertensive medications) with AF in patients with T2D and NAFLD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This is a retrospective cohort study.

Data source and patient selection criteria

Our study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Board of the Cleveland Clinic. We used the International Classification of Disease 9th Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9 CM) coding system and identified the patients with T2D (ICD 9 code: 250.xx) and suspected NAFLD (ICD 9 code: 571.8 and 571.9) from the Cleveland Clinic Electronic Medical Record System. We included patients who were 18 years or older and who underwent liver biopsy between January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2015. The decision to do liver biopsy was based on the clinical judgment of treating physician. Biopsies were reviewed by a group of expert gastroenterology and hepatology pathologists to detect fibrosis. Liver biopsies were classified according to NASH-CRN classification. Fibrosis was staged on a 5-point scale: Stage 0 = no fibrosis, stage 1 = zone 3 perisinusoidal/perivenular fibrosis, stage 2 = zone 3 and periportal fibrosis, stage 3 = septal/bridging fibrosis, and stage 4 = cirrhosis. AF was defined as fibrosis stage 3-4. We excluded the patients who did not have liver biopsy within 24 mo of T2D diagnosis, as well as, those with incomplete medical records or with secondary causes of hepatic steatosis {viral hepatitis, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease, lipodystrophy, starvation, on parenteral nutrition, abetalipoproteinemia, and using certain medications (corticosteroids, valproate, and antivirals)} were excluded. Patients were also excluded if they consumed more than 30 g of alcohol per day for males or more than 20 g per day for females. We collected age, gender, patient demographics including race, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, existing concurrent comorbidities such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, laboratory results, medications and their duration of use.

Statistical analysis

We used Pearson’s chi-square (χ2) tests or Fisher’s Exact to analyze the differences in patient demographics. For continuous variables, we performed a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) or the non-parametric Kriskal Wallis tests. Findings are reported either as mean ± SD, median (25th, 75th percentiles) or percentage. A multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the independent clinical factors associated AF. Age, gender, race, BMI, concurrent hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, inflammatory bowel disease, deep vein thrombosis, use of oral hypoglycemic medications, insulin, antihypertensive medications, antilipidemic medications, and aspirin were considered for inclusion in the logistic regression model and a stepwise variable selection method was used to choose the final model; variables with P < 0.10 were included in the final model. We adjusted for age, gender, race and BMI. SAS (Version 9.4, The SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States) was used for all analyses and a two-sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 1183 subjects were identified and included in the final analysis. Out of these patients, 32.2% (n = 381) had AF (fibrosis score 3-4) on their liver biopsy. The demographics and clinical characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The mean age at liver biopsy for our cohort was 52 ± 11 years and 65.7% patients were female. The majority of patients were Caucasians (85.1%) followed by African American (9.2%) and other races (5.7%). Overall mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures (SBP and DBP) in our cohort were 129.6 ± 17.1 mmHg and 73.7 ± 11.0 mmHg, respectively. There was no difference in the SBP between the two fibrosis groups (129.5 ± 16.6 vs 129.9 ± 18.2, P = 0.66) but significant difference existed between the DBP in the two groups (74.5 ± 10.5 vs 72.1 ± 11.7, P < 0.001). Hypertension and hyperlipidemia were more prevalent in Fibrosis 0-2 group (70% vs 57.7%, P < 0.001; 68.2% vs 49.1%, P < 0.001) whereas CKD was more prevalent in Fibrosis 3-4 group (4.6% vs 13.6%, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| Factor |

Overall (n = 1183) |

Fibrosis 0-2 (n = 802) |

Fibrosis 3-4 (n = 381) |

P value | |||

| n | Statistics | n | Statistics | n | Statistics | ||

| Age at biopsy (yr) | 1183 | 52.0 ± 11.6 | 802 | 50.3 ± 11.5 | 381 | 55.5 ± 11.1 | < 0.0011 |

| Gender | 1183 | 802 | 381 | 0.0173 | |||

| Female | 777 (65.7) | 545 (68.0) | 232 (60.9) | ||||

| Male | 406 (34.3) | 257 (32.0) | 149 (39.1) | ||||

| Race | 1183 | 802 | 381 | < 0.0013 | |||

| Caucasian | 1007 (85.1) | 665 (82.9) | 342 (89.8) | ||||

| African American | 109 (9.2) | 97 (12.1) | 12 (3.1) | ||||

| Other | 67 (5.7) | 40 (5.0) | 27 (7.1) | ||||

| Smoking | 1173 | 795 | 378 | 0.0413 | |||

| Never | 675 (57.5) | 477 (60.0) | 198 (52.4) | ||||

| Former | 426 (36.3) | 274 (34.5) | 152 (40.2) | ||||

| Current | 72 (6.1) | 44 (5.5) | 28 (7.4) | ||||

| BMI | 1183 | 35.4 ± 8.3 | 802 | 35.4 ± 8.1 | 381 | 35.2 ± 8.8 | 0.571 |

| BMI group | 1183 | 802 | 381 | 0.592 | |||

| Normal weight | 74 (6.3) | 41 (5.1) | 33 (8.7) | ||||

| Overweight | 233 (19.7) | 161 (20.1) | 72 (18.9) | ||||

| Obese | 596 (50.4) | 413 (51.5) | 183 (48.0) | ||||

| Severely obese | 280 (23.7) | 187 (23.3) | 93 (24.4) | ||||

| SBP | 1183 | 129.6 ± 17.1 | 802 | 129.5 ± 16.6 | 381 | 129.9 ± 18.2 | 0.661 |

| DBP | 1183 | 73.7 ± 11.0 | 802 | 74.5 ± 10.5 | 381 | 72.1 ± 11.7 | < 0.0011 |

| Hypertension | 1183 | 781 (66.0) | 802 | 561 (70.0) | 381 | 220 (57.7) | < 0.0013 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1183 | 734 (62.0) | 802 | 547 (68.2) | 381 | 187 (49.1) | < 0.0013 |

| CKD | 1183 | 89 (7.5) | 802 | 37 (4.6) | 381 | 52 (13.6) | < 0.0013 |

| IBD type | 1181 | 802 | 379 | 0.293 | |||

| CD | 29 (2.5) | 18 (2.2) | 11 (2.9) | ||||

| UC | 14 (1.2) | 12 (1.5) | 2 (0.53) | ||||

| None | 1138 (96.4) | 772 (96.3) | 366 (96.6) | ||||

| IBD | 1181 | 43 (3.6) | 802 | 30 (3.7) | 379 | 13 (3.4) | 0.793 |

| Stricturing disease | 1183 | 17 (1.4) | 802 | 10 (1.2) | 381 | 7 (1.8) | 0.433 |

| DVT | 1183 | 66 (5.6) | 802 | 43 (5.4) | 381 | 23 (6.0) | 0.643 |

ANOVA.

Kruskal-Wallis test.

Pearson's χ2 test. Statistics presented as mean ± SD or n (%). BMI: Body mass index; SBP: Systolic blood pressures; DBP: Diastolic blood pressures; CKD: Chronic kidney disease; CD: Crohn's disease; UC: Ulcerative colitis; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; DVT: Deep venous thrombosis.

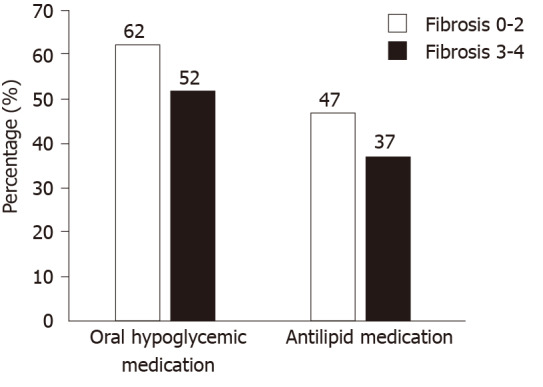

In terms of medications in the AF group (n = 381), 51.7% were on oral hypoglycemic, 30.1% were on insulin, 65.4% were on antihypertensive and 37.3% on anti-lipidemic medications for a median duration of 17.4 mo, 8.3 mo, 18.1 mo, and 20.9 mo respectively. Table 2 presents a summary of medication use in our cohort. Figure 1 shows a visual representation of medication usage among the two groups. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio (OR) of clinical factors associated with AF have been listed in the Table 3. Amongst oral hypoglycemic medications, Metformin use was associated with decreased risk of AF [OR = 0.64 (0.49, 0.82), P < 0.001]. We did not find a statistically significant association between Glipizide (P = 0.75), Pioglitazone (P = 0.11) or Sitagliptin/Januvia (P = 0.79) and the presence of AF. Liraglutide use was also associated with decreased risk of AF [OR = 0.30 (0.14, 0.64), P = 0.002]. We did not find a statistically significant association between the use of Detemir/Levemir (P = 0.83), Lantus (P = 0.14), Humulin (P = 0.35) or Byetta (P = 0.65) and the presence of AF. Amongst anti-hypertensive medications, use of Lisinopril [OR = 0.74 (0.56, 0.97), P = 0.031] and Hydrochlorothiazide [OR = 0.57 (0.43, 0.76), P < 0.001] were associated with decreased risk of AF. In contrast, use of Furosemide [OR = 1.9 (1.4, 2.5), P < 0.001) and Spironolactone [OR = 3.1 (2.0, 4.6), P < 0.001] were associated with increased risk of AF. For other anti-hypertensive medications we did not find any statistically significant association. Amongst anti-lipidemics, use of Atorvastatin [OR = 0.62 (0.44, 0.86), P = 0.004] and Simvastatin [OR = 0.61 (0.44, 0.85), P = 0.003] were associated with decreased risk of AF. We did not find a statistically significant association for other anti-lipid agents.

Table 2.

Medication use

| Factor |

Overall (n = 1183) |

Fibrosis 0-2 (n = 802) |

Fibrosis 3-4 (n = 381) |

P value | |||

| n | Statistics | n | Statistics | n | Statistics | ||

| Oral hypoglycemic medications | 1183 | 691 (58.4) | 802 | 494 (61.6) | 381 | 197 (51.7) | 0.0012 |

| Oral hypoglycemic duration (mo) | 691 | 19.4 (5.0, 52.1) | 494 | 20.6 (5.5, 54.4) | 197 | 17.4 (3.4, 50.0) | 0.0981 |

| Metformin use | 1183 | 631 (53.3) | 802 | 461 (57.5) | 381 | 170 (44.6) | < 0.0012 |

| Metformin duration (mo) | 631 | 20.0 (5.1, 53.3) | 461 | 20.8 (5.4, 54.5) | 170 | 18.3 (4.5, 52.1) | 0.361 |

| Glipizide use | 1183 | 116 (9.8) | 802 | 82 (10.2) | 381 | 34 (8.9) | 0.482 |

| Glipizide duration (mo) | 116 | 17.2 (5.6, 45.4) | 82 | 19.2 (5.5, 47.7) | 34 | 16.4 (6.0, 42.2) | 0.851 |

| Pioglitazone use | 1183 | 136 (11.5) | 802 | 100 (12.5) | 381 | 36 (9.4) | 0.132 |

| Pioglitazone duration (mo) | 136 | 15.5 (5.6, 44.8) | 100 | 15.8 (6.1, 51.9) | 36 | 12.5 (3.0, 40.8) | 0.301 |

| Sitagliptin/Januvia use | 1183 | 147 (12.4) | 802 | 100 (12.5) | 381 | 47 (12.3) | 0.952 |

| Sitagliptin/Januvia duration (mo) | 147 | 7.2 (1.6, 26.2) | 100 | 7.4 (2.3, 26.6) | 47 | 5.0 (0.30, 24.9) | 0.231 |

| Saxagliptin use | 1183 | 10 (0.85) | 802 | 9 (1.1) | 381 | 1 (0.26) | 0.132 |

| Insulin | 1183 | 370 (31.3) | 802 | 253 (31.5) | 381 | 117 (30.7) | 0.772 |

| Insulin duration (mo) | 370 | 10.9 (2.7, 34.0) | 253 | 11.9 (3.0, 36.8) | 117 | 8.3 (2.5, 25.3) | 0.121 |

| Liraglutide use | 1183 | 69 (5.8) | 802 | 61 (7.6) | 381 | 8 (2.1) | < 0.0012 |

| Liraglutide duration (mo) | 69 | 8.9 (2.6, 21.2) | 61 | 8.6 (2.5, 17.9) | 8 | 20.8 (5.0, 35.0) | 0.131 |

| Detemir/Levemir use | 1183 | 67 (5.7) | 802 | 48 (6.0) | 381 | 19 (5.0) | 0.492 |

| Detemir/Levemir duration (mo) | 67 | 5.9 (1.1, 17.7) | 48 | 3.9 (0.85, 16.4) | 19 | 9.0 (1.8, 17.7) | 0.391 |

| Lantus use | 1183 | 202 (17.1) | 802 | 127 (15.8) | 381 | 75 (19.7) | 0.102 |

| Lantus duration (mo) | 202 | 8.2 (0.80, 37.6) | 127 | 9.2 (0.90, 42.8) | 75 | 6.6 (0.20, 25.1) | 0.171 |

| Humulin use | 1183 | 65 (5.5) | 802 | 49 (6.1) | 381 | 16 (4.2) | 0.182 |

| Humulin duration (mo) | 65 | 12.0 (2.8, 34.0) | 49 | 12.8 (2.0, 34.9) | 16 | 8.4 (5.2, 18.7) | 0.881 |

| Byetta use | 1183 | 119 (10.1) | 802 | 83 (10.3) | 381 | 36 (9.4) | 0.632 |

| Byetta duration (mo) | 119 | 10.2 (3.8, 24.0) | 83 | 11.9 (4.4, 24.0) | 36 | 7.1 (2.5, 24.5) | 0.211 |

| Antihypertensive medications | 1183 | 787 (66.5) | 802 | 538 (67.1) | 381 | 249 (65.4) | 0.562 |

| Antihypertensive duration (mo) | 787 | 26.8 (4.7, 63.1) | 538 | 31.3 (5.8, 65.8) | 249 | 18.1 (3.1, 55.5) | 0.0101 |

| Lisinopril use | 1183 | 377 (31.9) | 802 | 274 (34.2) | 381 | 103 (27.0) | 0.0142 |

| Lisinopril duration (mo) | 377 | 16.1 (3.8, 49.0) | 274 | 18.1 (3.6, 49.4) | 103 | 12.4 (5.2, 48.6) | 0.861 |

| Losartan use | 1183 | 112 (9.5) | 802 | 71 (8.9) | 381 | 41 (10.8) | 0.292 |

| Losartan duration (mo) | 112 | 18.6 (3.2, 51.4) | 71 | 24.1 (6.2, 54.3) | 41 | 9.1 (2.1, 25.8) | 0.0771 |

| Furosemide use | 1183 | 252 (21.3) | 802 | 135 (16.8) | 381 | 117 (30.7) | < 0.0012 |

| Furosemide duration (mo) | 252 | 8.7 (1.8, 39.4) | 135 | 10.9 (2.3, 47.2) | 117 | 7.9 (1.4, 30.0) | 0.161 |

| Hydrochlorothiazide use | 1183 | 371 (31.4) | 802 | 279 (34.8) | 381 | 92 (24.1) | < 0.0012 |

| Hydrochlorothiazide duration (mo) | 371 | 32.9 (7.9, 65.6) | 279 | 34.4 (9.2, 67.1) | 92 | 22.6 (4.8, 58.0) | 0.0891 |

| Spironolactone use | 1183 | 115 (9.7) | 802 | 47 (5.9) | 381 | 68 (17.8) | < 0.0012 |

| Spironolactone duration (mo) | 115 | 5.4 (0.90, 29.1) | 47 | 18.7 (3.6, 46.9) | 68 | 3.0 (0.25, 10.4) | < 0.0012 |

| Amlodipine use | 1183 | 180 (15.2) | 802 | 128 (16.0) | 381 | 52 (13.6) | 0.302 |

| Amlodipine duration (mo) | 180 | 14.1 (3.0, 40.4) | 128 | 14.7 (3.0, 40.9) | 52 | 12.2 (3.5, 31.2) | 0.451 |

| Metoprolol use | 1183 | 273 (23.1) | 802 | 185 (23.1) | 381 | 88 (23.1) | 0.992 |

| Metoprolol duration (mo) | 273 | 11.4 (0.20, 45.1) | 185 | 12.2 (0.20, 45.9) | 88 | 10.0 (0.20, 36.1) | 0.411 |

| Carvedilol use | 1183 | 50 (4.2) | 802 | 28 (3.5) | 381 | 22 (5.8) | 0.0682 |

| Carvedilol duration (mo) | 50 | 8.9 (2.3, 22.3) | 28 | 11.3 (1.4, 28.7) | 22 | 8.4 (2.9, 13.5) | 0.391 |

| Antilipidemic medications | 1183 | 522 (44.1) | 802 | 380 (47.4) | 381 | 142 (37.3) | 0.0012 |

| Antilipidemic duration (mo) | 522 | 24.3 (5.3, 54.6) | 380 | 24.8 (5.5, 62.4) | 142 | 20.9 (4.4, 43.3) | 0.0861 |

| Rosuvastatin use | 1183 | 84 (7.1) | 802 | 61 (7.6) | 381 | 23 (6.0) | 0.332 |

| Rosuvastatin duration (mo) | 84 | 10.4 (2.7, 40.8) | 61 | 10.8 (3.0, 35.4) | 23 | 7.7 (2.2, 41.2) | 0.581 |

| Atorvastatin use | 1183 | 243 (20.5) | 802 | 179 (22.3) | 381 | 64 (16.8) | 0.0282 |

| Atorvastatin duration (mo) | 243 | 21.0 (5.3, 61.9) | 179 | 23.5 (5.4, 66.7) | 64 | 14.6 (4.4, 45.4) | 0.301 |

| Simvastatin use | 1183 | 251 (21.2) | 802 | 187 (23.3) | 381 | 64 (16.8) | 0.0102 |

| Simvastatin duration (mo) | 251 | 15.6 (3.4, 45.8) | 187 | 15.6 (3.6, 51.1) | 64 | 16.5 (1.6, 36.8) | 0.211 |

| Pravastatin use | 1183 | 79 (6.7) | 802 | 57 (7.1) | 381 | 22 (5.8) | 0.392 |

| Pravastatin duration (mo) | 79 | 13.8 (2.4, 33.9) | 57 | 13.8 (2.0, 30.7) | 22 | 15.4 (4.3, 34.7) | 0.811 |

| Gemfibrozil use | 1183 | 38 (3.2) | 802 | 27 (3.4) | 381 | 11 (2.9) | 0.662 |

| Gemfibrozil duration (mo) | 38 | 12.3 (3.0, 50.5) | 27 | 7.9 (2.1, 49.0) | 11 | 33.5 (5.8, 62.3) | 0.121 |

| Fenofibrate use | 1183 | 109 (9.2) | 802 | 78 (9.7) | 381 | 31 (8.1) | 0.382 |

| Fenofibrate duration (mo) | 109 | 17.2 (5.7, 40.7) | 78 | 22.0 (6.0, 44.6) | 31 | 12.6 (3.1, 28.7) | 0.271 |

| Aspirin use | 1183 | 339 (28.7) | 802 | 245 (30.5) | 381 | 94 (24.7) | 0.0372 |

| Aspirin dose | 335 | 241 | 94 | 0.982 | |||

| 81 mg | 328 (97.9) | 236 (97.9) | 92 (97.9) | ||||

| 325 mg | 7 (2.1) | 5 (2.1) | 2 (2.1) | ||||

Kruskal-Wallis test.

Pearson's χ2 test. Statistics presented as median (P25, P75) or n (%).

Figure 1.

Graphical presentation of differences in medication usage among patients in different fibrosis groups.

Table 3.

Assessment of associations between clinical factors and advanced fibrosis

| Factor |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted1 |

||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Hypertension | 0.59 (0.46, 0.76) | < 0.001 | 0.52 (0.39, 0.68) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.45 (0.35, 0.58) | < 0.001 | 0.42 (0.32, 0.54) | < 0.001 |

| CKD | 3.3 (2.1, 5.1) | < 0.001 | 2.6 (1.7, 4.2) | < 0.001 |

| IBD | 0.91 (0.47, 1.8) | 0.79 | 0.94 (0.47, 1.9) | 0.85 |

| DVT | 1.1 (0.67, 1.9) | 0.64 | 0.99 (0.58, 1.7) | 0.97 |

| Oral Hypoglycemic medications | 0.67 (0.52, 0.85) | 0.001 | 0.69 (0.53, 0.89) | 0.004 |

| Metformin use | 0.60 (0.47, 0.76) | < 0.001 | 0.64 (0.49, 0.82) | < 0.001 |

| Glipizide use | 0.86 (0.57, 1.3) | 0.48 | 0.93 (0.60, 1.4) | 0.75 |

| Pioglitazone use | 0.73 (0.49, 1.10) | 0.13 | 0.71 (0.47, 1.08) | 0.11 |

| Sitagliptin/Januvia use | 0.99 (0.68, 1.4) | 0.95 | 0.95 (0.65, 1.4) | 0.79 |

| Insulin | 0.96 (0.74, 1.3) | 0.77 | 1.02 (0.77, 1.3) | 0.91 |

| Liraglutide use | 0.26 (0.12, 0.55) | < 0.001 | 0.30 (0.14, 0.64) | 0.002 |

| Detemir/Levemir use | 0.82 (0.48, 1.4) | 0.49 | 0.94 (0.53, 1.7) | 0.83 |

| Lantus use | 1.3 (0.95, 1.8) | 0.10 | 1.3 (0.92, 1.8) | 0.14 |

| Humulin use | 0.67 (0.38, 1.2) | 0.18 | 0.75 (0.41, 1.4) | 0.35 |

| Byetta use | 0.90 (0.60, 1.4) | 0.63 | 1.1 (0.72, 1.7) | 0.65 |

| Antihypertensive medications | 0.93 (0.72, 1.2) | 0.56 | 0.77 (0.59, 1.02) | 0.064 |

| Lisinopril use | 0.71 (0.55, 0.93) | 0.014 | 0.74 (0.56, 0.97) | 0.031 |

| Losartan use | 1.2 (0.83, 1.9) | 0.30 | 1.09 (0.71, 1.7) | 0.70 |

| Furosemide use | 2.2 (1.6, 2.9) | < 0.001 | 1.9 (1.4, 2.5) | < 0.001 |

| Hydrochlorothiazide use | 0.60 (0.45, 0.79) | < 0.001 | 0.57 (0.43, 0.76) | < 0.001 |

| Spironolactone use | 3.5 (2.4, 5.2) | < 0.001 | 3.1 (2.0, 4.6) | < 0.001 |

| Amlodipine use | 0.83 (0.59, 1.2) | 0.30 | 0.74 (0.51, 1.07) | 0.11 |

| Metoprolol use | 1.00 (0.75, 1.3) | 0.99 | 0.87 (0.64, 1.2) | 0.37 |

| Carvedilol use | 1.7 (0.96, 3.0) | 0.071 | 1.6 (0.89, 3.0) | 0.12 |

| Antilipidemic medications | 0.66 (0.51, 0.85) | 0.001 | 0.58 (0.45, 0.76) | < 0.001 |

| Rosuvastatin use | 0.78 (0.48, 1.3) | 0.33 | 0.66 (0.40, 1.1) | 0.12 |

| Atorvastatin use | 0.70 (0.51, 0.96) | 0.029 | 0.62 (0.44, 0.86) | 0.004 |

| Simvastatin use | 0.66 (0.48, 0.91) | 0.011 | 0.61 (0.44, 0.85) | 0.003 |

| Pravastatin use | 0.80 (0.48, 1.3) | 0.39 | 0.75 (0.44, 1.3) | 0.28 |

| Gemfibrozil use | 0.85 (0.42, 1.7) | 0.66 | 0.92 (0.44, 1.9) | 0.82 |

| Fenofibrate use | 0.82 (0.53, 1.3) | 0.38 | 0.73 (0.47, 1.1) | 0.18 |

| Aspirin use | 0.74 (0.56, 0.98) | 0.037 | 0.58 (0.43, 0.78) | < 0.001 |

Adjusted for age at time of biopsy, gender, race and body mass index. CKD: Chronic kidney disease; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; DVT: Deep venous thrombosis; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first study in the literature exploring the association of different pharmacological modalities used in the treatment of T2D and AF in biopsy-proven NAFLD. Our study highlights the critical findings that certain prescription medications taken by patients with T2D are associated with decreased risk of AF. These medications might be playing a protective role by decreasing the rate of NAFLD progression. In our cohort of patients, oral hypoglycemic like metformin and liraglutide, anti-hypertensive medications like Lisinopril and Hydrochlorothiazide, and anti-lipid medication like Atorvastatin and Simvastatin are associated with decreased risk of AF, suggesting that they could perhaps have a protective effect on NAFLD.

Diabetes is a known cause of NAFLD and advanced liver disease is the most common cause of deaths in patients with T2D, showing a reciprocal relationship between the two. Treatment approaches in T2D mainly include either decreasing insulin resistance (metformin, thiazolidinediones) or increasing circulating insulin levels (exogenous insulin or sulfonylureas)[10,12,13]. A study by Hazlehurst et al[14]. explored the role of different classes of antidiabetic medications as a therapeutic disease modifying effect on NAFLD in patients with T2D. They specifically highlighted a promising role of metformin and GLP-1 agonists in treatment of NAFLD[14]. Our observation that Metformin is associated with a decrease in AF might suggests that insulin resistance is likely implicated in the pathophysiology of development of hepatic fibrosis. Metformin is effective as an anti-diabetic drug due to its ability to improve peripheral insulin sensitivity. Lowering blood glucose is achieved by decreasing gluconeogenesis in the liver, stimulating glucose uptake in the muscle, and increasing fatty acid oxidation in adipose tissue[15]. At the molecular level, some of the beneficial effects of metformin have been associated to the phosphorylation and nuclear export of Liver-kinase B1 which activates adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase, a regulator of energy metabolism, able to stimulate ATP-producing catabolic pathways (glycolysis, fatty acid oxidation, and mitochondrial biogenesis) and to inhibit ATP-consuming anabolic processes (gluconeogenesis, glycogen, fatty acid, and protein synthesis), leading to decreased glucose levels in the blood and ultimately decreased glucose mediated organ injury[16]. A meta-analysis showed a 50% reduction in Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence with metformin use (n = 8 studies; OR = 0.50, 95%CI: 0.34-0.73), further strengthening our observation that Metformin likely plays a protective role in liver disease[17]. In addition to Metformin, Liraglutide also showed a decreased risk of AF. Liraglutide is a glucagon-like-peptide 1 (GLP-1) analog that binds to the same receptors as the endogenous metabolic hormone GLP-1 and improves glucose homeostasis via its glucose-dependent stimulation of insulin secretion, inhibition of postprandial glucagon secretion and delayed gastric emptying[18]. A recent multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 study published by Armstrong et al[19] showed that 39% of the patients who received liraglutide and underwent end-of-treatment liver biopsy had resolution of definite NASH compared with 9% of the patients in the placebo group [relative risk 4.3 (95%CI: 1.0-17.7), P = 0.01]. Also they noted that 9% of the patients in the liraglutide group had progression of fibrosis compared to 36% in the placebo group [0.2 (0.1-1.0), P = 0.04], further supporting the findings of our study.

Another observation made in our study was the protective role of Lisinopril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme, a medication commonly prescribed to lower blood pressure, in patients with T2D. A recent meta-analysis showed that renin angiotensin system inhibitors resulted in a marginally significant reduction in liver fibrosis score [MD = -0.30, 95%CI (-0.62, 0.02), P = 0.05] and a significant reduction in liver fibrosis area [MD = -2.36%, 95%CI (-4.22%, -0.50%), P = 0.01], hence concluding that these medications perhaps play a more protective role in liver disease[20]. Multiple animal studies have suggested that angiotensin II contributes to hepatic fibrosis by interacting with the angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1 receptor) leading to the activation of hepatic stellate cells-the main collagen producing cells in the liver[21-23]. One animal model illustrated that inhibition of angiotensin II decreases the generation of reactive oxygen species, resulting in less collagen synthesis by hepatic stellate cells, and downregulates the vascular endothelial growth factor[24]. While another model suggested that angiotensin-receptor blockade leads to downregulation pro inflammatory/profibrotic cytokines[25], thus attenuating liver fibrosis. A study investigating the effect of Ramipril, an ACE inhibitor on the incidence of diabetes suggested that the use of ACE inhibitors may reduce the incidence of hyperglycemia in new diabetics as well as in those with insulin resistance[26]. Hence, this additional benefit that ACE inhibitors provide in diabetics may also contribute in part to the observed reduction in fibrosis in patients with NAFLD.

Our data in a large cohort of well characterized patients with NAFLD also suggests that the use of statins like Atorvastatin and Simvastatin is associated with reduced risk of advanced hepatic fibrosis in NAFLD patients with T2D. In the presence of NAFLD and hyperinsulinemia, there is accumulation of lipid molecules in the liver which further leads to inflammation and lipotoxicity[27], playing a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis, steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Statins, the mainstay of lipid-lowering therapy, improves liver outcomes by lowering lipids and lipotoxicity[28]. Apart from that, statins have also been reported to reduce cardiovascular risks and mortality in patients with NAFLD[29]. In a Swedish study that explored changes in liver histology over time among patients with NAFLD, there was less fibrosis in patients prescribed a statin[30]. However, previous studies have concluded that statin should not be used for NASH alone without the association of dyslipidemia[31]. For the simplification of the medication classification furosemide and spironolactone were considered under antihypertensive group, while these medications do lower blood pressure, they are often used primarily as diuretics. It is possible that patients were receiving these medications for advanced liver disease associated fluid overload or ascites.

The prevalence of NAFLD has progressively increased over the past 10 years, making it a significant health burden and the treatment of NAFLD is of prime concern to health care professionals and patients due to significant mortality and morbidity it implies[32]. Treatment is focused on lifestyle changes and managing the associated comorbidities. Lifestyle modification includes attention to patient’s diet by promoting intake of fruits and vegetables and avoiding high fat content; and increasing physical activity[33,34]. Obesity treating drugs like Orlistat and bariatric surgery may also help in selected cases in achieving weight loss that can help in NAFLD[34,35]. Other measures include insulin sensitizers, drugs that reduce blood lipids, glucagon-mimetics, drugs that may reduce fibrosis, angiotensin receptor blockers, and medicines believed to reduce endoplasmic reticular stress such as vitamin E, ursodeoxycholic acid, and S-adenosyl methionine[30]. Several newer agents such as Obeticholic acid and GFT505 have shown promising results and various other pharmacotherapies are still being studied[32]. Treatment options such as gene based therapeutic treatment of NAFLD in diabetics are still in the experimental phases, however they could offer promising therapeutic options in the near future[36].

Our study has several limitations. It is a retrospective analysis and association does not imply causal relationship. In our multivariable analysis we adjusted for possible confounders, however, it is possible that one or more unknown confounders might be responsible for some of the results which we have observed. Since our study population was recruited from a single center, generalization should be avoided. In addition, despite using the strict exclusion criteria, some degree of recall bias may have been present while evaluating for alcohol consumption and medication use. On the other hand, the large sample size of biopsy proven NAFLD patients is a major strength of the current study.

In conclusion, in this large cohort of T2D with biopsy proven NAFLD, patients who were receiving Metformin, Liraglutide, Lisinopril, Hydrochlorothiazide, Atorvastatin and Simvastatin were less likely to have AF on liver biopsy while patients who were receiving Furosemide and Spironolactone had a higher likelihood of having AF on liver biopsies. Although our study does not indicate a causation it is important that physicians are aware of this key association. In the management and treatment of patients with NAFLD, clinicians should consider both liver disease and the associated metabolic co-morbidities. Along with diet and physical activity, focus should be given on specific pharmacological therapies that have been proven to be beneficial in NAFLD. Despite the consistent increase in the knowledge of therapeutic options for NAFLD, its management still remains a challenge for the scientific community and additional clinical trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of various agents in NAFLD and T2D.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is estimated around 25% of the global population and is expected to increase further in the coming years. Type-2 diabetes mellitus is a major risk factor for NAFLD with significant portion of diabetic patients develop progressive liver disease and a proportion of these patients also develop advanced fibrosis (AF). NAFLD pose significant health care burden and is associated with significant mortality and morbidity.

Research motivation

Patients with diabetes are commonly on multiple medication regimen, of which, some have a positive impact on slowing the progression of NAFLD to AF. For instance, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) and Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors have been shown previously to be associated with reduction in AF in viral hepatitis patients. There is a paucity of data on the association of these medications on the progression of liver fibrosis in NAFLD patients.

Research objectives

We aimed to understand the association of the different pharmacologic modalities used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus on the progression of liver fibrosis in NAFLD patients with type-2 diabetes.

Research methods

We identified all adult patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus who underwent liver biopsy for suspected NAFLD at the Cleveland Clinic between January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2015. We retrospectively reviewed a cohort of 1183 patients with type-2 diabetes and biopsy proven NAFLD. We compared demographics, clinical characteristics, and differences in pattern of medication use in patients who had biopsy-proven NAFLD with and without advance fibrosis. A univariate and multivariate analysis was performed to assess the association of different classes of medication with and without the presence of AF.

Research results

We found that the patients who were receiving Metformin, Liraglutide, Lisinopril, Hydrochlorothiazide, Atorvastatin and Simvastatin were less likely to have AF on biopsy, while patients who were receiving furosemide and spironolactone were more likely to have AF when they underwent liver biopsy. Diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease were more likely to have AF on liver biopsy.

Research conclusions

Our study highlights the protective role of some of the commonly used medications in the treatment of type-2 diabetes mellitus. We propose that Metformin, Liraglutide, Lisinopril, Hydrochlorothiazide, Atorvastatin and Simvastatin may have a beneficial role in slowing down the progression of NAFLD.

Research perspectives

Although it is possible that some unknown confounding factors could have impacted our findings, this study lays a solid groundwork for future prospective studies to further investigate the protective role of these medications on the progression of liver fibrosis in diabetic patients with NAFLD.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved for publication by our Institutional Reviewer.

Informed consent statement: This was a retrospective study which involved the chart review. Requirement for individual patient consent was waived by the IRB.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the Authors have no conflict of interest related to the manuscript.

STROBE statement: The guidelines of the STROBE Statement have been adopted and implemented.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: January 31, 2020

First decision: February 27, 2020

Article in press: June 10, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Durazzo M, Enosawa S, Kusmic C, Tomkin GH S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Mohamed Tausif Siddiqui, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Digestive Diseases and Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States.

Hina Amin, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Digestive Diseases and Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States.

Rajat Garg, Department of Hospital Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, OH 44195, United States.

Pravallika Chadalavada, Department of Hospital Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, OH 44195, United States.

Wael Al-Yaman, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Digestive Diseases and Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States.

Rocio Lopez, Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Cleveland Clinic, OH 44195, United States.

Amandeep Singh, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Digestive Diseases and Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States. singha4@ccf.org.

Data sharing statement

The original anonymous dataset is available on request from the corresponding author at singha4@ccf.org.

References

- 1.Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, George J, Bugianesi E. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:686–690. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong RJ, Liu B, Bhuket T. Significant burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis in the US: a cross-sectional analysis of 2011-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:974–980. doi: 10.1111/apt.14327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zafrani ES. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an emerging pathological spectrum. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0943-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Younossi ZM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease - A global public health perspective. J Hepatol. 2019;70:531–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leite NC, Salles GF, Araujo AL, Villela-Nogueira CA, Cardoso CR. Prevalence and associated factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. Liver Int. 2009;29:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williamson RM, Price JF, Glancy S, Perry E, Nee LD, Hayes PC, Frier BM, Van Look LA, Johnston GI, Reynolds RM, Strachan MW Edinburgh Type 2 Diabetes Study Investigators. Prevalence of and risk factors for hepatic steatosis and nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease in people with type 2 diabetes: the Edinburgh Type 2 Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1139–1144. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amiri Dash Atan N, Koushki M, Motedayen M, Dousti M, Sayehmiri F, Vafaee R, Norouzinia M, Gholami R. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2017;10:S1–S7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tacelli M, Celsa C, Magro B, Giannetti A, Pennisi G, Spatola F, Petta S. Antidiabetic Drugs in NAFLD: The Accomplishment of Two Goals at Once? Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2018;11:121. doi: 10.3390/ph11040121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corey KE, Shah N, Misdraji J, Abu Dayyeh BK, Zheng H, Bhan AK, Chung RT. The effect of angiotensin-blocking agents on liver fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2009;29:748–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.01973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tolman KG, Fonseca V, Dalpiaz A, Tan MH. Spectrum of liver disease in type 2 diabetes and management of patients with diabetes and liver disease. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:734–743. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Marco R, Locatelli F, Zoppini G, Verlato G, Bonora E, Muggeo M. Cause-specific mortality in type 2 diabetes. The Verona Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:756–761. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.5.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hazlehurst JM, Woods C, Marjot T, Cobbold JF, Tomlinson JW. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes. Metabolism. 2016;65:1096–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stumvoll M, Nurjhan N, Perriello G, Dailey G, Gerich JE. Metabolic effects of metformin in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:550–554. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loomba R, Lutchman G, Kleiner DE, Ricks M, Feld JJ, Borg BB, Modi A, Nagabhyru P, Sumner AE, Liang TJ, Hoofnagle JH. Clinical trial: pilot study of metformin for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:172–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh S, Singh PP, Singh AG, Murad MH, Sanchez W. Anti-diabetic medications and the risk of hepatocellular cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:881–91; quiz 892. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Federico A, Zulli C, de Sio I, Del Prete A, Dallio M, Masarone M, Loguercio C. Focus on emerging drugs for the treatment of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16841–16857. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.16841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong MJ, Gaunt P, Aithal GP, Barton D, Hull D, Parker R, Hazlehurst JM, Guo K LEAN trial team, Abouda G, Aldersley MA, Stocken D, Gough SC, Tomlinson JW, Brown RM, Hübscher SG, Newsome PN. Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2016;387:679–690. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00803-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu Q, Li N, Li F, Zhou Z, Han Q, Lv Y, Sang J, Liu Z. Therapeutic effect of renin angiotensin system inhibitors on liver fibrosis. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2016;17:1470320316628717. doi: 10.1177/1470320316628717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bataller R, Gäbele E, Parsons CJ, Morris T, Yang L, Schoonhoven R, Brenner DA, Rippe RA. Systemic infusion of angiotensin II exacerbates liver fibrosis in bile duct-ligated rats. Hepatology. 2005;41:1046–1055. doi: 10.1002/hep.20665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuncer I, Ozbek H, Ugras S, Bayram I. Anti-fibrogenic effects of captopril and candesartan cilexetil on the hepatic fibrosis development in rat. The effect of AT1-R blocker on the hepatic fibrosis. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2003;55:159–166. doi: 10.1078/0940-2993-00309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Töx U, Steffen HM. Impact of inhibitors of the Renin-Angiotensin-aldosterone system on liver fibrosis and portal hypertension. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:3649–3661. doi: 10.2174/092986706779026138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshiji H, Fukui H. Renin-angiotensin system and progression of chronic liver diseases. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1020–1022. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1897-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu W, Song S, Huang Y, Gong Z. Effects of perindopril and valsartan on expression of transforming growth factor-beta-Smads in experimental hepatic fibrosis in rats. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1250–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DREAM Trial Investigators. Dagenais GR, Gerstein HC, Holman R, Budaj A, Escalante A, Hedner T, Keltai M, Lonn E, McFarlane S, McQueen M, Teo K, Sheridan P, Bosch J, Pogue J, Yusuf S. Effects of ramipril and rosiglitazone on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in people with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose: results of the Diabetes REduction Assessment with ramipril and rosiglitazone Medication (DREAM) trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1007–1014. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cusi K. Role of obesity and lipotoxicity in the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:711–725.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farrell G. Should we lower lipids in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:152–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Gossios TD, Griva T, Anagnostis P, Kargiotis K, Pagourelias ED, Theocharidou E, Karagiannis A, Mikhailidis DP GREACE Study Collaborative Group. Safety and efficacy of long-term statin treatment for cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease and abnormal liver tests in the Greek Atorvastatin and Coronary Heart Disease Evaluation (GREACE) Study: a post-hoc analysis. Lancet. 2010;376:1916–1922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61272-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Mathiesen UL, Holmqvist M, Bodemar G, Kechagias S. Statins in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and chronically elevated liver enzymes: a histopathological follow-up study. J Hepatol. 2007;47:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dharmalingam M, Yamasandhi PG. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2018;22:421–428. doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_585_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dajani A, AbuHammour A. Treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Where do we stand? an overview. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:91–105. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.178527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Diehl AM, Brunt EM, Cusi K, Charlton M, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology. 2012;55:2005–2023. doi: 10.1002/hep.25762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polyzos SA, Kountouras J, Mantzoros CS. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From pathophysiology to therapeutics. Metabolism. 2019;92:82–97. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia MF, Bian H, Gao X. NAFLD and Diabetes: Two Sides of the Same Coin? Rationale for Gene-Based Personalized NAFLD Treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:877. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original anonymous dataset is available on request from the corresponding author at singha4@ccf.org.