Summary

Amino acid transport via phloem is one of the major source‐to‐sink nitrogen translocation pathways in most plant species. Amino acid permeases (AAPs) play essential roles in amino acid transport between plant cells and subsequent phloem or seed loading. In this study, a soybean AAP gene, annotated as GmAAP6a, was cloned and demonstrated to be significantly induced by nitrogen starvation. Histochemical staining of GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS transgenic soybean revealed that GmAAP6a is predominantly expressed in phloem and xylem parenchyma cells. Growth and transport studies using toxic amino acid analogs or single amino acids as a sole nitrogen source suggest that GmAAP6a can selectively absorb and transport neutral and acidic amino acids. Overexpression of GmAAP6a in Arabidopsis and soybean resulted in elevated tolerance to nitrogen limitation. Furthermore, the source‐to‐sink transfer of amino acids in the transgenic soybean was markedly improved under low nitrogen conditions. At the vegetative stage, GmAAP6a‐overexpressing soybean showed significantly increased nitrogen export from source cotyledons and simultaneously enhanced nitrogen import into sink primary leaves. At the reproductive stage, nitrogen import into seeds was greatly enhanced under both sufficient and limited nitrogen conditions. Collectively, our results imply that overexpression of GmAAP6a enhances nitrogen stress tolerance and source‐to‐sink transport and improves seed quality in soybean. Co‐expression of GmAAP6a with genes specialized in source nitrogen recycling and seed loading may represent an interesting application potential in breeding.

Keywords: source‐to‐sink partitioning, amino acid transport, amino acid permease, nitrogen, soybean

Introduction

Nitrogen (N) is an indispensable component in biomolecules involving nucleotides, proteins, chlorophylls and hormones. Long‐distance transport of N through phloem is responsible for N selective partitioning from source to sink organs in plants. Amino acids represent one of the major long‐distance transport and redistribution forms of organic N in plants. The efficient amino acid delivery from source to sink is important for the growth and development of both vegetative and reproductive organs (Tegeder, 2014; Tegeder and Masclaux‐Daubresse, 2018). For example, more than 50%–70% of wheat seed proteins originate from amino acids remobilized from source organs (Barneix, 2007; Kichey et al., 2007). In soybean, N remobilization from vegetative parts contributes 38.9%–50.4% of the total N in mature seeds (Bender et al., 2015; Gaspar et al., 2017). A revised model simulating N accumulation and use in soybean indicated that the highest yield was achieved when the growing stem had a high N concentration and the senescing stem had a low‐N concentration, implying that enhanced source‐to‐sink N transfer was key for increasing the yield potential of soybean (Sinclair et al., 2003).

The long‐distance transport of amino acids is performed by amino acid transporters (Tegeder, 2014; Tegeder and Masclaux‐Daubresse, 2018). H+/amino acid cotransporter amino acid permeases (AAPs) in plants are a group of proteins responsible for amino acid uptake through roots, loading into phloem and redistribution to seeds (Tegeder, 2012; Tegeder, 2014; Tegeder and Rentsch, 2010). The specialized roles of different members of AAPs have been investigated in Arabidopsis and several other plant species. For instance, Arabidopsis AtAAP1 is expressed in early embryos and is important for embryo amino acid absorption. Knockout of AtAAP1 led to an accumulation of free amino acids in seed coats and the endosperm but a reduction of the N content in dry seeds (Sanders et al., 2009). Arabidopsis AtAAP2 protein is localized to the phloem throughout the plant and functions in xylem–phloem transfer of amino acids. In AtAAP2 T‐DNA insertion lines, N delivery to seeds was decreased, and seed protein levels were reduced (Zhang et al., 2010). AtAAP8 gene was reported to be expressed in source leaf phloem (Santiago and Tegeder, 2016). The aap8 mutant showed decreased amino acid phloem loading and partitioning to sink organs, which led to an increase in total N in source leaves but reduced vegetative biomass and seed yields (Rentsch et al., 2007; Santiago and Tegeder, 2016; Santiago and Tegeder, 2017). The high‐affinity transporter in Arabidopsis, AtAAP6, is expressed in xylem parenchyma cells (Okumoto et al., 2002). The abolition of AtAAP6 function led to an approximately 70% reduction in the total amino acid concentration of sieve element sap (Hunt et al., 2010). In legume species, expression of PsAAP1 driven by Arabidopsis AtAAP1 promoter in pea enhanced N allocation from source to sink organs, improved the nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) as well as total biomass and seed yields (Perchlik and Tegeder, 2017; Zhang et al., 2015). Cotyledon parenchyma cell‐specific overexpression of VfAAP1 in Pisum sativum and Vicia narbonensis significantly increased seed weight, seed size and contents of total globulins (containing the major 7S and 11S storage proteins) (Rolletschek et al., 2005). In rice, OsAAP6 is expressed in the seed endosperm, and its overexpression greatly improved the grain protein content and nutrition quality (Peng et al., 2014).

A recent bioinformatics analysis of the soybean genome revealed 189 amino acid transporter genes, including 35 AAPs (Cheng et al., 2016); however, the detailed biochemical properties and biological functions of these AAPs in soybean remain elusive. An AAP‐like gene Glyma.17g192000 was strongly induced under N‐deficient conditions in DNA microarray gene expression analysis. We named this gene GmAAP6a following phylogenetic analysis. Histochemical GUS staining of GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS transgenic soybean was utilized to investigate the localization of GmAAP6a protein in planta. The selective transport of amino acids by GmAAP6a was tested by toxic amino acid analog treatment and sole amino acid feeding assay. We further generated GmAAP6a‐overexpressing soybean plants and evaluated their tolerance to N deficiency and source‐to‐sink transfer of amino acids under low‐N conditions. Our study demonstrated that GmAAP6a is involved in N translocation from source to sink organs and is essential for seed N accumulation in soybean.

Results

GmAAP6a encodes an N deficiency‐responsive amino acid permease

Glyma.17g192000 was identified as an N deficiency‐responsive gene based on the transcriptome analysis of N‐deprived soybean (data not shown). This gene is annotated to encode a 470‐amino acid AAP‐like protein. Phylogenetic analysis together with reported AAP proteins revealed that it is highly homologous to AAP6 in Arabidopsis or Brassica napus (Figure S1a). We therefore named this gene GmAAP6a. A total of 10 transmembrane helices were predicted (Figure S1b), which is in line with known AAP integral membrane proteins (Cheng et al., 2016; Tegeder et al., 2000; Wipf et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2017). BLASTP searches using GmAAP6a as a query revealed 65–85% identity between GmAAP6a and other AAP6‐like plant proteins depending on the species (Figure S1b).

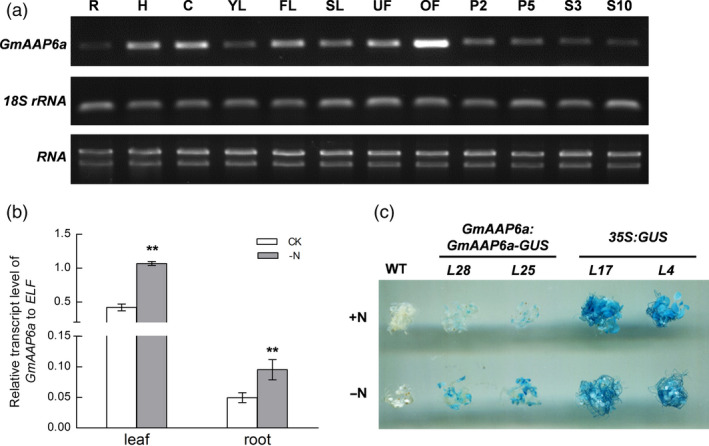

Semiquantitative RT–PCR analysis showed that the GmAAP6a transcript was detectable in almost all soybean tissues. The highest level of the transcriptional expression of GmAAP6a was detected in opened flowers, while relatively lower expression was detected in roots, young leaves and developing seeds (Figure 1a). Under N starvation conditions as described in the materials and methods, GmAAP6a transcripts in leaves and roots were increased more than onefold compared to those under control conditions (Figure 1b). To further examine the effects of N starvation on the accumulation level of GmAAP6a protein, the 7‐day‐old seedlings of GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS transgenic Arabidopsis (line 25 and 28) were transferred from semi‐solid half‐strength Murashige and Skoog (1/2 MS) medium to N‐sufficient (+N) or N‐depleted (−N) liquid 1/2 MS medium and allowed to grow for another 5 days. The histochemical GUS staining revealed that the accumulation level of the GmAAP6a‐GUS fusion protein was greatly enhanced by the N starvation treatment in the GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings, while the accumulation level of the GUS protein was constantly maintained at a similar level in the 35S:GUS controls (line 4 and 17; Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

GmAAP6a expression patterns in soybean plants under normal and N starvation conditions. (a) Semiquantitative RT–PCR was used to determine GmAAP6a organ‐specific expression in soybean plants. Two micrograms of total RNA for each sample was reverse‐transcribed into cDNA with 18S rRNA as a control. R, H and C represent the root, hypocotyl and cotyledon, respectively, at the Vc stage (with cotyledons fully opened and unifoliolate leaves unrolled); YL, FL and SL represent the young leaf, functional leaf and senescent leaf, respectively, collected from the main stem; UF and OF: unopened and opened flowers; P2 and P5: pods with lengths of 2 and 5 cm, respectively; S3 and S10: seeds with lengths of 3 and 10 mm, respectively. (b) Relative transcript levels of GmAAP6a in leaves and roots under normal (CK) and N deprivation (‐N) conditions. Soybean elongation factor 1 beta (ELF) was used as an internal control. Data are the mean ± SE of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences based on Student’s t‐test (**α = 0.01). (c) GUS staining of GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS transgenic Arabidopsis grown in N‐rich (+N) or N‐free (−N) liquid medium. Wild‐type (WT) and 35S:GUS transgenic Arabidopsis were used as references. GUS staining was performed with 10 plants of each sample, with three repeats. Representative results are shown

GmAAP6a is predominantly expressed in vascular tissues of soybean plants

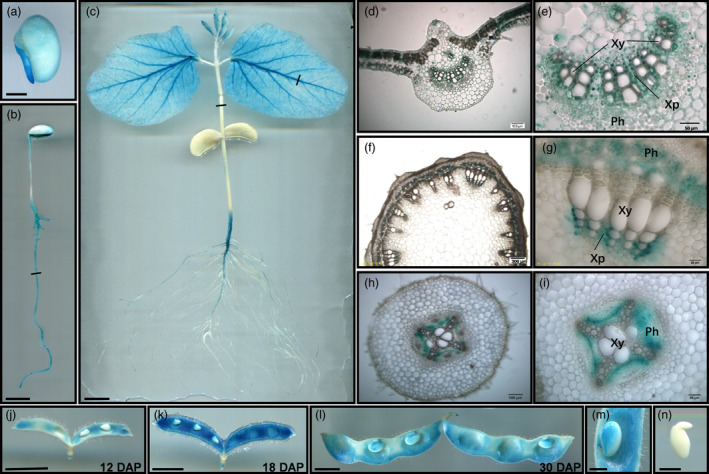

To further examine the detailed expression profile and functions of GmAAP6a, three independent lines of GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS transgenic soybean plants were generated. The typical results of histochemical GUS staining are shown in Figure 2. In germinating seeds, the GUS signal was mainly detected in embryonic roots (Figure 2a). At later developmental stages, blue colouring was detected in almost all organs, with a major presence in the vascular tissues of the main roots, lateral roots, stems, leaves, petals, filaments and seed pods, but no traces were observed in the pistils (Figure 2b‐d, f and h; Figure S2). A close‐up examination of the cross sections of roots, stems and leaves revealed prominent blue colouring in phloem and xylem parenchyma cells (Figure 2e, g and i). The strongest GUS signal in seed pods was observed at the early seed‐filling stage, that is, 18 days after pollination (DAP) (Figure 2j‐l). The GUS signal was also observed in the funicle and the adjacent seed coat of developing seeds (Figure 2m). However, no GUS signal was detected in the developing embryo (Figure 2n).

Figure 2.

Histochemical GUS staining of GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS soybean plants. The GUS signal was observed in germinating radicles (a), tap roots and lateral roots of 4‐ (b) or 10‐day‐old seedlings (c). The GUS signal was also found in vasculatures of leaves and newly developing buds (c). Bright‐field images of cross sections showed that GUS signals were predominant in phloem and xylem parenchyma cells of the leaf (d, e) and stem (f, g) and in root phloem (h, i). In developing pods, GUS signals were predominant in vasculatures and peaked at 18 days after pollination (j‐l). The GUS signal was also found in the funicle and the adjacent seed coat at 28 days after pollination (m), but not in developing embryos (n). Short black lines in (b, c) indicate the section site for (d‐i). Scale bars = 1 cm (b‐c, j‐l), 3 mm (a, m and n), 100 μm (d, f and h) or 50 μm (e, g and i). Ph: phloem; Xy: xylem; Xp: xylem parenchyma

GmAAP6a can deliver neutral and acidic amino acids

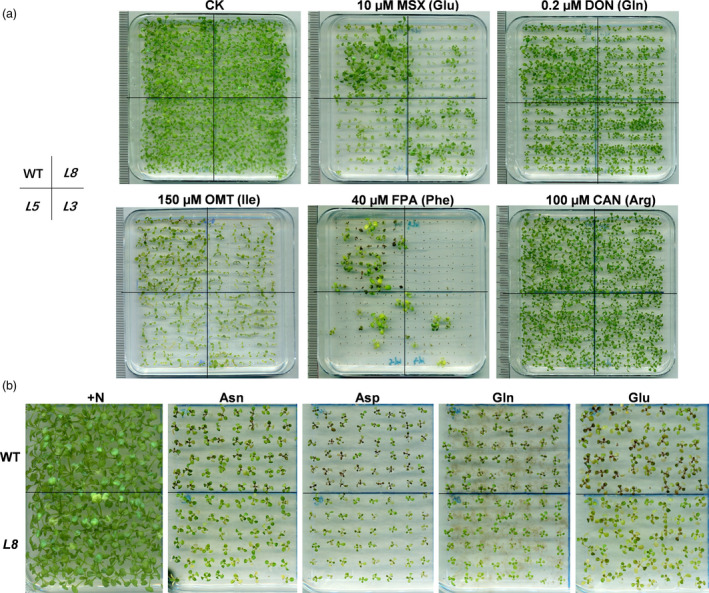

Some amino acid analogs are known to compete specifically with the corresponding amino acids and are toxic for plant cells. Growth and uptake assays using low levels of toxic amino acid analogs are often employed to determine the function of amino acid transporters (Perchlik et al., 2014; Slayman, 1974). To investigate whether GmAAP6a functions in amino acid transfer and the associated substrate specificity, three independent lines of 35S:GmAAP6a transgenic Arabidopsis were generated and evaluated by their survival abilities against a range of toxic amino acid analogs. We modulated the concentrations of the analogs to ensure that wild‐type plants survived. As shown in Figure 3a, much lower survival rates were found in the GmAAP6a‐overexpressing seedlings (Line 3, 5 and 8) grown on media containing 0.2 μm DON, 150 μm OMT or 40 μm FPA, that is, the toxic analog for neutral amino acids Gln, Ile and Phe, respectively. Similarly, a lower survival rate of the transgenic plants was also observed on media with 10 μm MSX, the analog for acidic amino acid Glu. However, only a minor difference was observed between WT and the GmAAP6a‐overexpressing seedlings grown on media containing 100 μm CAN, an analog for the basic amino acid Arg (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Overexpression of GmAAP6a in Arabidopsis enhances acidic and neutral amino acid assimilation. (a) Wild‐type (WT) and three independent lines of GmAAP6a‐overexpressing Arabidopsis plants (L3, L5 and L8) were grown for 3 weeks on half‐strength MS medium containing amino acid analogs of glutamate (N‐methyl sulphoximine; MSX), glutamine (2‐amino‐6‐diazo‐5‐oxo‐L‐norleucine; DON), phenylalanine (p‐fluorophenylalanine; FPA) and arginine (canavanine; CAN) while grown for 2 weeks on the medium containing isoleucine (o‐methylthreonine; OMT). (b) A typical line of GmAAP6a‐overexpressing Arabidopsis (L8) and its WT control were grown for 3 weeks on half‐strength MS medium containing normal N (+N) or 1 mm of Asn, Asp, Gln or Glu as the sole N source. All experiments were biologically repeated at least three times and similar results were obtained

To further determine the transportable substrates of GmAAP6a, a typical line of GmAAP6a‐overexpressing Arabidopsis (L8) and its WT control were grown on N‐free medium supplemented with either single neutral (Asn or Gln, the major forms of amino acids delivered from source to sink organs in plants) or acidic (Glu or Asp) amino acids as the sole N source. It was observed that GmAAP6a‐overexpressing plants accumulated less anthocyanin and exhibited better growth compared to the wild‐type control on all four plates containing a single amino acid as the sole source of N (Figure 3b). All results indicated that GmAAP6a functions in transporting neutral and acidic amino acids.

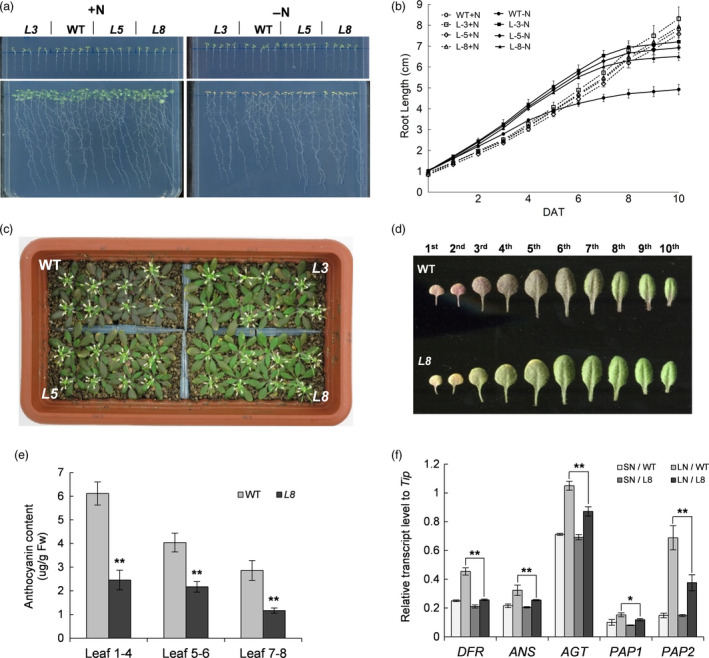

Overexpression of GmAAP6a enhances tolerance to N deficiency in both Arabidopsis and soybean

We further examined the responses of GmAAP6a‐overexpressing Arabidopsis to N deficiency treatment. Three independent lines of 5‐day‐old GmAAP6a transgenic Arabidopsis and their wild‐type control at the same developmental stage were transferred to a 1/2 MS plate (+N) or an N‐free 1/2 MS plate (−N) and allowed to grow for another 12 days. No significant difference was observed between the transgenic lines and their WT control under N‐sufficient condition. However, primary roots of the transgenic seedlings were much longer than the control under N‐free condition (Figure 4a). Although during the early period of the treatment, in response to the N‐limiting condition, primary roots of both the GmAAP6a transgenic and WT seedlings on N‐free plate grew faster than their control counterparts on N‐sufficient plate, the inhibition of root growth occurred much earlier in WT (at 6 DAT) than in the transgenic lines (at 8 DAT) (Figure 4b). When the 9‐day‐old seedlings were transferred to vermiculite and grown for 23 days with a constantly limited supply of N (1 mm), WT plants showed a purple colour in their leaves, whereas the leaves of the three transgenic lines remained largely green (Figure 4c), indicating that elevated N deficiency tolerance was also observed in adult GmAAP6a‐overexpressing Arabidopsis. To gain a better view of the differences, the rosette leaves of a typical line of the transgenic plants (L8) were compared with their WT counterparts. As shown in Figure 4d, when the first seven leaves of WT turned purple, most of the corresponding leaves in the transgenic plant were still green, and only the first two leaves were slightly purple. As expected, the anthocyanin contents in different leaves of the GmAAP6a‐overexpressing Arabidopsis were all significantly lower than those in WT (Figure 4e). Consistently, the real‐time RT–PCR analysis showed that the transcript levels of three anthocyanin biosynthesis marker genes, DFR (dihydroflavonol‐4‐reductase), ANS (anthocyanidin synthase) and AGT (anthocyanin glycosyltransferase), and two transcriptional regulators involved in anthocyanin production, PAP1 (production of anthocyanin pigment 1) and PAP2 (production of anthocyanin pigment 2; Lea et al., 2007; Lillo et al., 2008; Nemie‐Feyissa et al., 2014; Peng et al., 2008), were significantly lower in the GmAAP6a‐overexpressing Arabidopsis than in the WT control under N‐limited conditions (Figure 4f).

Figure 4.

Arabidopsis seedlings overexpressing GmAAP6a showed better root elongation and accumulated less anthocyanin in leaves under N deprivation. (a) Three Arabidopsis lines (L3, L5 and L8) overexpressing GmAAP6a were grown vertically on half‐strength MS plates for 5 days (upper panels) and then transferred to half‐strength MS plates with (left, +N) or without (right, −N) N for an additional 12 days (lower panels). (b) Root growth curves of Arabidopsis in (a) after the transfer are shown as root length increases over a ten‐day time course. Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 10). DAT, days after transplanting. (c) Phenotypes of GmAAP6a‐overexpressing (L3, L5 and L8) and wild‐type (WT) Arabidopsis plants grown under N‐deficient conditions in vermiculite with half‐strength Hoagland’s solution containing 1 mm N for 23 days. (d) Leaves from WT and L8 were laid out in order of emergence. (e) Anthocyanin content measurements in leaves of WT and L8. Data represent the mean ± SD, and asterisks indicate significant differences from WT based on Student’s t‐test (n = 8): *α = 0.05, **α = 0.01. (f) Nine‐day‐old GmAAP6a‐overexpressing Arabidopsis (L8) and the wild‐type (WT) grown on half‐strength MS medium were transplanted to sufficient‐N (SN, vermiculite with half‐strength Hoagland’s solution) or limited‐N (LN, vermiculite with half‐strength Hoagland’s solution containing 1 mm N) conditions and grown for 23 days. Expression analyses of genes involved in anthocyanin synthesis (DFR, ANS, AGT) and metabolism (PAP1 and PAP2) were evaluated by quantitative RT–PCR using RNAs isolated from the fifth and six leaves. The Tip41‐like gene was used as an internal control. Data represent the mean ± SD, and asterisks indicate significant differences from WT based on Student’s t‐test (n = 8): *α = 0.05, **α = 0.01

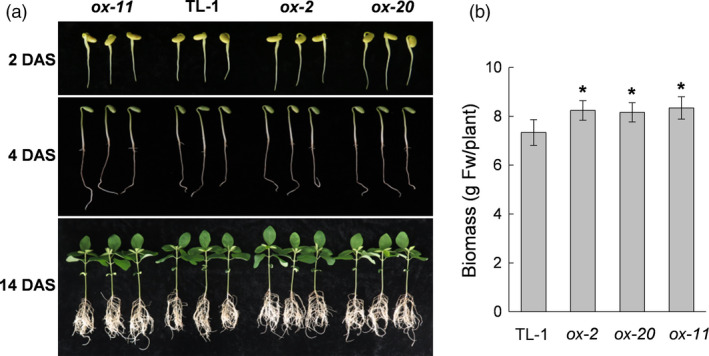

We also tested the effects of GmAAP6a overexpression on soybean. Four independent lines of single‐copy 35S:GmAAP6a transgenic soybean (GmAAP6a‐ox) were obtained. Three of them (ox‐2, ox‐11 and ox‐20) with relatively higher expression of GmAAP6a (Figure S3) were selected and grown under low‐N conditions (1 mm N) with Tianlong 1 (TL‐1) control plants in a hydroponic system as described in the ‘materials and methods’ section. It was found that all three GmAAP6a transgenic lines had more developed roots and higher biomass in comparison with TL‐1 at 14 days after sowing (DAS) (Figure 5a, b), although only minor differences were observed at earlier time points such as 2 and 4 DAS. All these results suggested that overexpression of GmAAP6a led to increased tolerance to N deficiency in both Arabidopsis and soybean.

Figure 5.

GmAAP6a‐overexpressing soybean seedlings show higher biomass when grown under low‐N conditions. Soybean plants were grown under low‐N conditions (1 mm N). (a) Three GmAAP6a‐overexpressing lines (ox‐2, ox‐20 and ox‐11) and the nontransgenic Tianlong 1 control (TL‐1) were germinated and grown in vermiculite supplied with 1 mm N. Pictures were taken at 2, 4 or 14 days after sowing (DAS). (b) Fresh weights were measured at 14 DAS (n = 6). The measurements were performed in triplicate, and the data shown represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of a representative experiment. Asterisks indicate significant differences based on Student’s t‐test: *α = 0.05

Overexpression of GmAAP6a accelerates N export from source and import into sink leaves under low‐N conditions in soybean

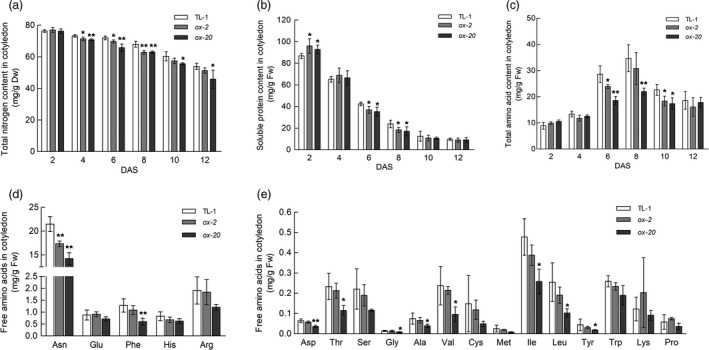

During germination and early seedling development of soybean, cotyledons serve as the main source organ (Ohyama et al., 2013). To further analyse whether GmAAP6a is involved in source‐to‐sink amino acid transport in soybean, we first measured the dynamic changes of N levels in the GmAAP6a‐overexpressing cotyledons under N‐limited conditions (1 mm N). The contents of total N and soluble proteins were constantly decreased in the cotyledons of GmAAP6a transgenic lines (ox‐2 and ox‐20) and the TL‐1 control from 2 to 10 DAS (Figure 6a, b). From 10 to 12 DAS, the contents of total N continued decreasing in the transgenic lines and TL‐1 control while the contents of soluble proteins seemed to have reached a steady state (Figure 6a, b). Interestingly, the contents of soluble proteins in the ox‐2 and ox‐20 cotyledons were higher than those in the TL‐1 control line at 2 DAS but became significantly lower than their control since the 6 DAS (Figure 6b). This suggested a more rapid degradation of storage proteins in the GmAAP6a transgenic cotyledons. The contents of free amino acids were first elevated from 2 to 8 DAS but declined afterwards from 8 to 12 DAS in both transgenic soybean cotyledons and TL‐1 to support the growth of newly formed organs (Figure 6c). It is noteworthy that the contents of total free amino acids were lower in the cotyledons of ox‐2 and ox‐20 than in those of TL‐1 at almost all time points (Figure 6c), implying increased amino acids export from the transgenic cotyledons. Analysis of individual free amino acids with relatively higher abundance showed that Asn represented the most dominant export amino acid from cotyledons. The level of Asn in ox‐2 cotyledons was only 80% of that in the TL‐1 control, and it was only 66% of the TL‐1 counterpart in ox‐20 (Figure 6d, Table S1). In addition, a broad spectrum of amino acids with lower abundances was also significantly reduced in the cotyledons of GmAAP6a‐transgenic seedlings (Figure 6e, Table S1).

Figure 6.

GmAAP6a overexpression accelerates N export from source leaves under low‐N conditions. Wild‐type (TL‐1) and GmAAP6a‐overexpressing soybean plants (ox‐2, ox‐20) were grown under low‐N conditions (1 mm N). Cotyledon samples were collected over a 2–12 DAS time course; and leaf samples were collected at 6 DAS when the primary leaf remained unfolded. The total N content in cotyledons (a) was normalized to the dry weight (n = 6). Soluble protein and free amino acid levels in cotyledons at 6 DAS (b‐e) were normalized to fresh weights (n = 6). Data represent the mean ± SD and are representative of two independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant differences based on Student’s t‐test: *α = 0.05, **α = 0.01

We further measured the contents of phloem exudates released from the cut cotyledon petioles. As expected, the total free amino acid contents in the cotyledon exudates of ox‐2 and ox‐20 were significantly increased compared to those in TL‐1 (Figure S4a). The contents of a wide spectrum of individual amino acids, including the most abundant Asn, were also higher in the exudates collected from ox‐2 and ox‐20 cotyledons than those from the TL‐1 control (Figure S4b). These results supported the previous observations that overexpression of GmAAP6a enhanced the export of amino acids from the source cotyledons.

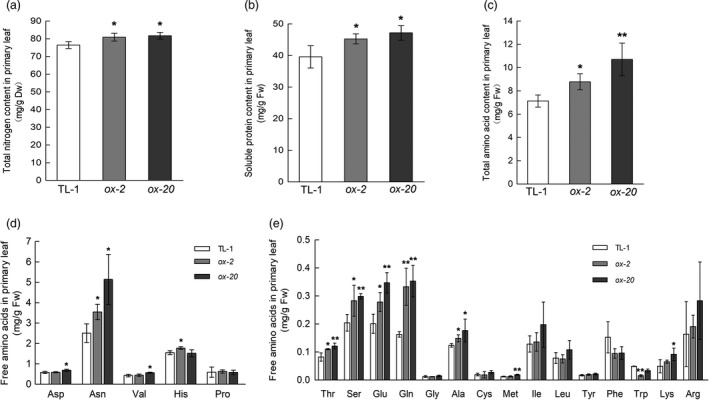

We next examined the N contents in primary leaves, which was the main sink organ at 6 DAS under 1 mm N treatment. The contents of total N, soluble proteins and total amino acids were all significantly higher in the two transgenic lines than in TL‐1 (Figure 7a‐c). Individual amino acid measurements showed that the contents of a broad spectrum of amino acids were significantly increased (Figure 7d, e; Table S2).

Figure 7.

GmAAP6a overexpression improves N import into sink leaves under low‐N conditions. Wild‐type (TL‐1) and GmAAP6a‐overexpressing soybean plants (ox‐2, ox‐20) were grown under low‐N conditions (1 mm N). Primary leaf samples were collected at 6 DAS when they remained unfolded. The total N content in the primary leaf (a) was normalized to the dry weight (n = 6). Soluble protein and free amino acid levels (b‐e) were normalized to fresh weights (n = 6). Data represent the mean ± SD and are representative of two independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant differences based on Student’s t‐test: *α = 0.05, ** α = 0.01

Overexpression of GmAAP6a enhanced nitrogen import into seeds and altered the seed amino acid composition in soybean

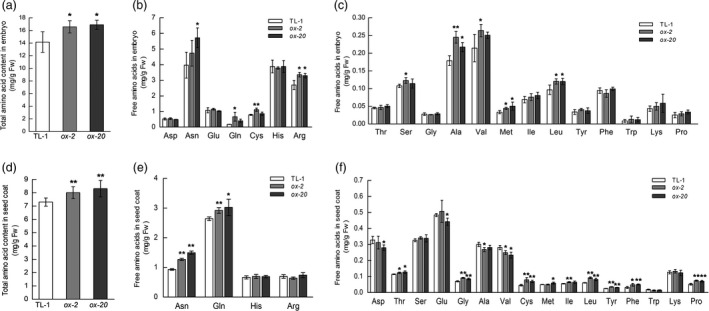

Seeds are the major sink during the reproductive stage and are closely related to the yield and quality traits of crops (Lemoine et al., 2013; Thorne, 1980). To further investigate the role of GmAAP6a at the reproductive stage, we compared the N levels in developing seeds of the two transgenic lines of GmAAP6a‐overexpressing soybean (ox‐2 and ox‐20) with those of the TL‐1 control. Seed coats and immature embryos were harvested and analysed separately as described in the materials and methods. In the transgenic embryos at the early seed‐filling stage, the levels of total free amino acids were much higher than those in the TL‐1 control (Figure 8a). The increase was due to elevated amounts of many individual amino acids, among which Asn and Arg contributed most remarkably with contribution rates at 31.7% and 27.4%, respectively, in ox‐2 while at 63.9% and 22.0%, respectively, in ox‐20 (Figure 8b, c). In the seed coat, the contents of total free amino acids and the contents of a wide spectrum of individual amino acids were all higher than those in TL‐1 (Figure 8d‐f). Among the significantly altered amino acids, the most abundant amino acids, Gln and Asn, were increased by 9.5%–14.4% and 36.2%–60.6%, respectively (Figure 8e).

Figure 8.

GmAAP6a‐overexpressing soybean plants show enhanced amino acid import into seeds. Seed samples were collected at the R5 stage, that is, 25–30 days after pollination (DAP) when premature seeds were approximately 5 mm in size. Thirty or more seeds from six wild‐type or GmAAP6a overexpression plants were separated into embryos and seed coats, which were further processed for measurements. Total and individual free amino acid levels in the embryo (a‐c) and seed coat (d‐f) were normalized to fresh weights (n = 3). Data represent the mean ± SD and are representative of two independently grown sets of plants. Asterisks indicate significant differences based on Student’s t‐test: * α = 0.05, ** α = 0.01

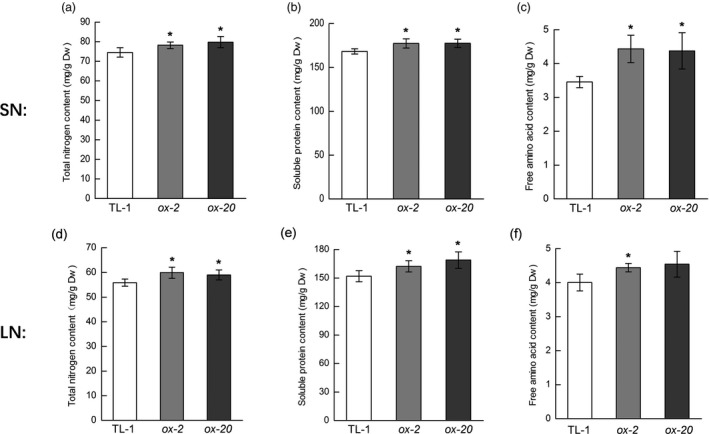

We further evaluated the N levels in mature/dry seeds from plants grown under both sufficient‐N (SN) and low‐N (LN) conditions. The contents of total N, soluble proteins and total amino acids were all significantly elevated in the GmAAP6a‐transgenic lines grown under both conditions (Figure 9). All results demonstrated that overexpression of GmAAP6a increased amino acid transport from sources into soybean seeds.

Figure 9.

GmAAP6a‐overexpressing dry soybean seeds showed higher N content under both sufficient and low‐N conditions. Two independent lines of GmAAP6a‐overexpressing soybean (ox‐2 and ox‐20) and the nontransgenic control plants (TL‐1) grown under sufficient (soil irrigated with half‐strength Hoagland’s solution) and limited (vermiculite irrigated with half‐strength Hoagland’s solution containing 1 mm N) N conditions were harvested, and at least 30 seeds from a group of 6 plants were air‐dried for 2 weeks and machine‐crushed before analyses. Total elemental seed N, soluble protein, and free amino acids under sufficient‐N conditions (a‐c) or limited‐N conditions (d‐f) were measured. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological repetitions and are representative of two independently grown sets of plants. Asterisks indicate significant differences from TL‐1 based on Student’s t‐test: * α = 0.05, ** α = 0.01

Discussion

The source‐to‐sink transfer of N exerts profound effects on the development of reproductive organs as well as crop yields (Tegeder and Masclaux‐Daubresse, 2018). Amino acids represent the main long‐distance transport forms of N in most plant species, and AAPs are thought to be essential in this process (Tegeder, 2014; Tegeder and Masclaux‐Daubresse, 2018; Tegeder and Rentsch, 2010). In this study, we demonstrated that the GmAAP6a gene, a close ortholog of Arabidopsis AtAAP6, was involved in source‐to‐sink transport of amino acids and played important roles in optimizing N partitioning in soybean.

GmAAP6a functions in neutral and acidic amino acid transport in soybean

Plant AAP family proteins differ in their tissue or cellular localizations, substrate specificities, and affinities to exert their physiological functions (Fischer et al., 2002; Tegeder, 2012). By protein sequence, GmAAP6a in soybean is quite similar with AtAAP6, AtAAP8 and AtAAP1 in Arabidopsis, which were reported to be acidic and neutral amino acid transporters (Fischer et al., 2002; Okumoto et al., 2002). The hypersensitivity to toxic analogs of acidic and neutral amino acids and the increased tolerance to single neutral or acidic amino acid feeding in GmAAP6a‐overexpressing Arabidopsis suggested that GmAAP6a also functions in selectively transporting neutral and acidic amino acids (Figure 3). Accordingly, compared to those in TL‐1 control, both the decline of major acidic and neural amino acids in source cotyledons and the increase of these amino acids in sink organs such as primary leaves and seed coats were generally much greater in GmAAP6a‐ox soybean (Figures 6, 7, 8). In addition, GUS staining of GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS transgenic soybean showed that GmAAP6a was predominantly expressed in xylem parenchyma cells and phloem (Figure 2). The high‐level distribution of GmAAP6a in xylem parenchyma was similar to that of AtAAP6, the counterpart in Arabidopsis, which was reported to be involved in the translocation of acidic and neutral amino acids from the xylem to the phloem (Okumoto et al., 2002). Taken together, these results suggest that GmAAP6a may also have acidic and neutral amino acid transport and phloem and/or seed loading functions.

GmAAP6a is involved in the source‐to‐sink transfer of amino acids in soybean at both vegetative and reproductive stages

Most AAP proteins expressed in plant vascular tissues function in source‐to‐sink amino acid transport, hence exert direct influences on the development of vegetative sinks and seeds (Tegeder and Ward, 2012). For instance, overexpression of OsAAP5 that expressed in root and vasculatures of aboveground organs markedly increased amino acid transport from root to the tiller basal part, leaf sheath and leaf blade of rice, resulting in decreases in tiller number and grain yield, while the opposite effects were observed in the RNAi lines (Wang et al., 2019). Silencing of PsAAP6 in phloem and cortex cells of nodulated roots significantly decreased the export of amino acids from nodules and thereby reduced N supply for roots and shoots in pea (Garneau et al., 2018). In the current study, amino acid partitioning between the source and sink tissues of GmAAP6a‐overexpressing soybean were evaluated during different developmental transitions.

At the vegetative stage, soybean cotyledons were found to provide nutrients to newly formed organs continuously for approximately one week after emergence. Cotyledons (source) can provide amino acids from protein degradation to support the growth of new leaves (sink) and protein synthesis (Ritchie et al., 1994). Therefore, cotyledon(s) and new leaves provide an ideal source‐sink pair for this study. The contents of total N and soluble proteins were decreased more greatly and the level of residual amino acids was significantly lower in the cotyledons of GmAAP6a‐ox soybean than in those of TL‐1 control under N‐limited condition (Figure 6a‐c). This observation together with the analysis of phloem exudates from cut cotyledon petioles (Figure S4) both suggest that overexpression of GmAAP6a could accelerate amino acids export from cotyledons. Consistently, higher amino acid contents were observed in the sink primary leaves of GmAAP6a‐ox seedlings than in the TL‐1 control at 6 DAS (Figure 7). Enhanced N export from source cotyledons and simultaneously elevated N import into sink growing leaves in GmAAP6a‐overexpressing soybean indicate that GmAAP6a mediates source‐to‐sink amino acid transport in soybean.

At the reproductive stage, developing seeds and pods represent the largest sink (Tegeder, 2014). The free amino acids in the seed coat come from either direct phloem unloading via symplastic pathway or from conversion of other N forms (Tegeder and Hammes, 2018). They are first released into the apoplast through exporters like UmamiTs and are then taken up by young embryo because the developing embryo is symplasmically isolated from maternal tissues (Müller et al., 2015; Offler et al., 2003; Patrick et al., 2003; Thorne, 1981; Werner et al., 2011). GmAAP6a was localized in the vasculatures of pod, funicle and seed coat but not in embryo (Figure 2j‐n); however, the contents of free amino acids in both the seed coats and immature embryos of GmAAP6a‐ox plants were higher than those in the TL‐1 control (Figure 8), suggesting that GmAAP6a not only functions in phloem loading of amino acids into the seed coat but also indirectly promotes the amino acid uptake into embryo. The elevated export of amino acids into embryo could be resulted from the ectopic expression of GmAAP6a driven by constitutive 35S promoter. Another possibility could be that overexpression of GmAAP6a increased the activities of other transporters that specifically involved in amino acid transport from seed coat to embryo. It has been reported that knockout of AtAAP8 in Arabidopsis led to down‐regulations of several other AAP family members such as AtAAP1, AtAAP2, AtAAP4 and AtAAP6 (Santiago and Tegeder, 2016), while overexpression of AAP1 in pea simultaneously increased the expression level of the cationic amino acid transporter encoding gene CAT6 (Perchlik and Tegeder, 2017). Interestingly, the content of basic amino acid Arg that was not supposed to be transported by GmAAP6a was increased in the embryos of GmAAP6a‐ox seeds (Figure 8b). In addition, levels of some neutral amino acids such as Ala and Val were reduced in the GmAAP6a transgenic seed coats while increased in the young embryos (Figure 8c, f). These observations support that GmAAP6a overexpression may have also promoted other transporter‐mediated amino acid loading into the embryo.

The levels of total N, soluble proteins and free amino acids were elevated in GmAAP6a transgenic soybean dry seeds under both low‐ and sufficient‐N conditions (Figure 9), suggesting that GmAAP6a could function in either environment. This may expand its application for NUE improvement under different N conditions in soybean breeding. Overexpression of GmAAP6a ultimately results in higher storage protein accumulation in soybean seeds (Figure 9). Similarly, seed‐specific overexpression of VfAAP1 in Pisum sativum and Vicia narbonensis also led to markedly increased contents of total globulins in the seeds (Rolletschek et al., 2005). These imply that genetic manipulation of special AAPs in legumes could affect seed quality.

GmAAP6a is involved in enhanced resistance to low‐N stress

The expression of most AAPs was reported to be induced under high N conditions (Gaufichon et al., 2010; Liu and Bush, 2006). For instance, PsAAP1 and PsAAP2 in P. sativum and BnAAP1, BnAAP2 and BnAAP6 in B. napus were all induced by excessive N supply (Tegeder et al., 2007; Tilsner et al., 2005). However, both the transcript and protein levels of GmAAP6a were remarkably increased by N starvation treatment, suggesting that GmAAP6a responds particularly to low‐N stress (Figure 1b, c).

Better developed roots and higher biomass were observed for the GmAAP6a‐overexpressing Arabidopsis and soybean under low‐N conditions (Figure 4, 5). This could be because overexpression of GmAAP6a increased the source‐to‐sink transport of amino acids and thus provided better support for newly growing organs. Another possibility might be that overexpression of GmAAP6a promoted the absorption of N in the roots through a feedback regulatory mechanism and shoot‐to‐root signalling. This is consistent with previous findings in the AtAAP1:ScMMP1 (yeast S‐methylmethionine permease 1) and AtAAP1:PsAAP1 transgenic peas that enhanced amino acid phloem loading promoted N absorption in the roots and thereby enhanced the metabolism or utilization of the corresponding N in the source or sink organs, respectively (Perchlik and Tegeder, 2017; Tan et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2015).

To date, improved nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) has been achieved in several plant species through genetic manipulation of AAP genes; however, it was only reported in the AtAAP1:PsAAP1 transgenic pea that higher shoot biomass, increased root‐to‐shoot N partitioning and yield were obtained under low‐N conditions (Perchlik and Tegeder, 2017). In the current study, we reported the functional analysis of a soybean AAP for the first time. All results in the current study support that genetic manipulation of GmAAP6a‐like amino acid transporters represents an effective strategy to increase N partitioning efficiency, enhances N stress tolerance, and improves seed quality in crops.

Materials and methods

Phylogenetic analysis and sequence alignment

The DNA sequence of GmAAP6a and its encoded protein sequence were obtained from the Phytozome website (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html). The protein sequences of reported AAPs were retrieved from NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) according to the accession numbers. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016) using the maximum likelihood method based on the JTT matrix‐based model (Jones et al., 1992). The tree was bootstrapped using 1000 replicates, and the values were marked on the joint.

The protein sequence of GmAAP6a was then used to perform BLASTp searches against the NCBI databases to identify homologous genes in certain species, including legumes French bean (PvAAP6‐like) and Medicago truncatula (MtAAP6‐like), eudicots Arabidopsis (AtAAP6), oilseed rape (BnAAP6‐like) and tomato (SlAAP6‐like), monocots maize (ZmAAP6‐like) and rice (OsAAP6‐like). The GmAAP6a amino acid sequences were aligned with these AAP6 or AAP6‐like proteins using DNAMAN software. Transmembrane domains of GmAAP6a were predicted using the web‐based TMHMM Server v. 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/).

Plant materials and growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) ecotype Columbia (Col‐0) and Glycine max (L.) cultivar Tianlong 1 (TL‐1) were used for all experiments and as the genetic background for corresponding plant transformations.

Arabidopsis seeds were sterilized and grown on half‐strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium [0.8% (w/v) agar, pH 5.7, 1% (w/v) sucrose] as described by Xia et al. (2012). To study the response of the wild‐type and GmAAP6a‐overexpressing Arabidopsis to N starvation, 5‐day‐old seedlings grown under a long‐day photoperiod (16‐h light/8‐h night) were transferred to half‐strength MS medium with or without N. Seedlings were scanned every two days with a scanner (Epson, V370, China), and the root length was measured with ImageJ software. For N‐limitation treatment of adult plants, 9‐day‐old seedlings were transferred to vermiculite with half‐strength Hoagland’s solution as the sufficient‐N control or half‐strength Hoagland’s solution containing 1 mm N as the low‐N treatment. When the plants started bolting at stages 6.0–6.10 (Boyes et al., 2001), the rosette leaves were harvested for further phenotypic observation, anthocyanin determination or gene expression analyses.

Soybean plants were grown in a phytotron under a light/dark regime of 14‐h light at 250 to 300 μmol photons/m2/s and 10‐h dark with a stable temperature of 25 °C at 60% humidity. For the N‐limited treatment assay, mature, dry soybean seeds of three homozygous lines (T4 generation) and the nontransgenic control were first sterilized as previously described (Liu et al., 2013) and were then sown in 1/5 gallon plastic pots (one seed per pot) containing vermiculite moistened with modified half‐strength Hoagland’s solution (1 mm N). After germination, the seedlings were fertilized every two days with 200 mL of the same solution mentioned above. Expression analysis of GmAAP6a in response to N‐limitation treatment was performed as described previously (Xia et al., 2012).

For other assays, unless otherwise stated, soybean plants were grown in 2 gallon pots containing a mixture of compost soil (75%) and vermiculite (25%) with regular irrigation. For the analysis of gene expression patterns, organs at different growth stages were sampled for RNA extraction. For expression analysis of GmAAP6a in GmAAPP6a‐overexpressing lines, fully expanded primary leaves were sampled at V1 stage (Fehr et al., 1971). For physiological analyses of the developing seeds, pods were tagged according to days after pollination (DAP) and were collected in the middle of the light phase.

Binary constructs and plant transformations

The complete coding sequence of GmAAP6a harbouring the first intron was amplified by fusion PCR using 2 pairs of primers (Table S3) with genomic DNA and full‐length cDNA of soybean (cv. Williams 82) leaves as templates. The Nco I site was introduced into the forward primer 35S‐GmAAP6a‐F, and the BstE II site was introduced into reverse primer 35S‐GmAAP6a‐R. After overlap extension PCR, the resulting fusion fragment was digested and ligated into the binary vector pCAMBIA3301 (CAMBIA, Australia) between the Nco I and BstE II sites, resulting in a 35S:GmAAP6a construct.

To construct the GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS fusion gene, the promoter sequence of GmAAP6a, a 1500‐bp DNA fragment covering the 5′ flanking region was first amplified from soybean genomic DNA by PCR and then used to replace the 35S promoter of the abovementioned binary vector 35S:GmAAP6a by Kpn I/Nco I double digestion to create an intermediate transcription unit GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a. The intermediate unit was subsequently combined with a GUS gene fragment amplified from pCAMBIA1301 plasmids (CAMBIA, Australia) to obtain the final GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS binary construct.

The authenticity of the fusion constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing followed by transformation into Agrobacterium strain GV3101 or LBA4404 for Arabidopsis or soybean stable transformation. Arabidopsis transformation was carried out by the Agrobacterium‐mediated floral dipping method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Transformants were first screened on half‐strength MS medium containing 30 mg/L hygromycin. The resistant seedlings were transferred to soil and verified by genomic PCR and semiquantitative RT–PCR. Homozygous T3 Arabidopsis were used for all experiments. Transgenic soybeans were obtained using the Agrobacterium‐mediated cotyledon node transformation method as described previously (Paz et al., 2006).

Genotyping of GmAAP6a‐overexpressing transgenic soybean

The genomic DNA in all transgenic soybeans as well as in the corresponding controls was extracted by the CTAB method (Porebski et al., 1997). The presence of transgenes was verified by PCR analysis. For Southern blot analysis, a digoxigenin detection kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) was used following the manufacturer’s instructions. Ten micrograms of DNA was digested with the restriction enzymes EcoR I or EcoR V, separated on 0.7% agarose gel, transferred to positively charged nylon membranes (Amersham Hybond‐N+, Buckinghamshire, UK), and subjected to hybridization with a GmAAP6a‐specific probe. After immunological detection, the membrane was stripped and rehybridized with a bar (bialaphos resistance gene)‐specific probe.

RNA isolation and gene expression analyses

Total RNA extraction, semiquantitative RT–PCR and real‐time RT–PCR assays were performed as described previously (Liu et al., 2010). All primers used are listed in Table S3.

Growth of Arabidopsis plants on toxic amino acid analogs or single amino acids as the sole N source

The wild‐type and GmAAP6a‐overexpressing transgenic Arabidopsis plants were cultured on half‐strength MS medium containing amino acid analogs at optimized concentrations as described previously (Perchlik et al., 2014) but with some adjustments. Specifically, 0.2 μm 2‐amino‐6‐diazo‐5‐oxo‐L‐norleucine (DON) (Poppenberger et al., 2003), 150 μm o‐methylthreonine (OMT) (Mourad and King, 1995), 40 μm p‐fluorophenylalanine (FPA) (Yan et al., 2000), 10 μm N‐methyl sulphoximine (MSX) (Su et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2010) and 100 μm canavanine (CAN) (Yan et al., 2000) were used as toxic analogs for glutamine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, glutamate and arginine, respectively. All seedlings grown on toxic amino acid analogs were photographed after three weeks except for those grown on OMT, which were imaged after two weeks. For the growth of Arabidopsis on medium with a single amino acid as the sole N source, plants were cultured for 17 days on N‐free half‐strength MS medium containing 1 mm of a certain amino acid (Asn, Asp, Gln or Glu). All plants were imaged with a scanner (Epson, V370, China).

Histochemical GUS staining assay

Histochemical GUS staining was performed as previously described (Wang et al., 2005). To examine the responses to N starvation, 7‐day‐old seedlings of two independent GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS Arabidopsis lines (L25 and L28) were transferred from semi‐solid half‐strength MS medium to N‐depleted (‐N) or N‐sufficient (+N) liquid 1/2 MS medium for 5 days before staining. Wild‐type and two independent 35S:GUS lines (L4 and L17) were used as controls.

For the tissue‐specific expression assay, three independent GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS soybean lines were generated, and at least five seedlings of each line were subjected to GUS expression assays. Whole plants or geminating seeds, roots and opening flowers of GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS soybean seedlings were stained for 24 h, whereas seedpods were stained for 4 h. Stained plants were cleared by incubation in a mixture of EtOH (75%) and acetic acid (25%). Images of whole seedlings and organs were recorded with a scanner (Epson, V370, China) except for flowers that were dissected and imaged under a stereomicroscope (Leica, M165C). In addition, the tap roots of 4‐day‐old seedlings, hypocotyls and primary leaves of 10‐day‐old seedlings were embedded in 3% agarose gel and sliced into 30‐μm sections with a tissue vibration microtome (Leica, VT1000S, Germany) and were subsequently imaged with a microscope (Olympus, BX63, Japan).

Collection of cotyledon exudates

Cotyledon exudates were collected from cut cotyledon petioles of soybean plants at 8 DAS for 2 h as described previously (Deeken et al., 2008; Urquhart and Joy, 1981). Phloem exudates from soybean cotyledons were finally concentrated under vacuum to 1 mL, and 100 μL HCl of 1 N was added. Samples were then incubated on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 10 625 g at 4°C prior to use in amino acid analysis (Santiago and Tegeder, 2016).

Quantifications of total N, amino acid, protein and anthocyanin contents

For the N content determination, cotyledons and primary leaves of young seedlings grown under N‐limited conditions were collected every two days from 2 to 12 DAS and from 6 to 12 DAS, respectively, and heated to denature the enzymes at 105°C for 30 min followed by being dried to a constant weight at 80°C. All samples, including dry seeds, were ground into powder in tubes with a Tissuelyser machine (Jingxin, China), and total N and C contents were determined using a Vario EL elemental analyser (Elementar, Germany). The same batches of cotyledons, primary leaves and dry seeds were also sampled for free amino acids and soluble protein extraction. Free amino acids were extracted in mixed buffer containing methanol (15%) and chloroform (25%) and were subsequently measured by an amino acid analyser (MembraPure, A300, Germany). For the measurement of free amino acids in developing seeds, premature seed samples were collected at 25–30 days after pollination (DAP) when seeds were approximately 5mm in size at R5 stage. Seed coats and embryos were separated carefully with tweezers and frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately prior to amino acid extraction. Total soluble proteins were extracted in extraction buffer as previously described (Liu et al., 2010). Protein concentrations were determined with the Bradford method (Bradford, 1976). The anthocyanin content was measured as previously described (Jin et al., 2012).

Accession number

GmAAP6a (Glyma.17g192000).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Author contributions

NNW conceived and designed the study, supervised the experiments, and compiled and finalized the article. SL, TX, WX, YZ, XY and XZ performed the experiments. NNW, SL and DW analysed the data. SL, DW and YM drafted and wrote the manuscript. YM, NNW and LL revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Phylogenetic analysis of GmAAP6a.

Figure S2. GUS staining of GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS soybean in roots and flowers.

Figure S3. Genotyping of GmAAP6a‐overexpressing transgenic soybean plants.

Figure S4. GmAAP6a‐overexpressing soybean plants show higher free amino acid content in cotyledon exudates.

Table S1. Free amino acid contents in the cotyledons of TL‐1 and transgenic seedlings under low nitrogen conditions.

Table S2. Free amino acid contents in primary leaves of TL‐1 and transgenic seedlings under low nitrogen conditions.

Table S3. Gene‐specific primers used in this study.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Xin‐an Zhou (Oil Crops Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for providing the ‘Tianlong 1’ soybean seeds. We thank Juanjuan Bi and Jieli Jin for their kind assistance with the histochemical GUS staining assay. This research was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFD0101005), the Major S&T Projects on the Cultivation of New Varieties of Genetically Modified Organisms (Nos. 2016ZX08004005‐004 and 2016ZX08010002‐006), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31370285) and the 111 project (B08011).

Liu, S. , Wang, D. , Mei, Y. , Xia, T. , Xu, W. , Zhang, Y. , You, X. , Zhang, X. , Li, L. and Wang, N. N. (2020) Overexpression of GmAAP6a enhances tolerance to low nitrogen and improves seed nitrogen status by optimizing amino acid partitioning in soybean. Plant Biotechnol J, 10.1111/pbi.13338

Sheng Liu and Dan Wang should be considered joint first authors.

References

- Barneix, A.J. (2007) Physiology and biochemistry of source‐regulated protein accumulation in the wheat grain. J. Plant Physiol. 164, 581–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender, R.R. , Haegele, J.W. and Below, F.E. (2015) Nutrient uptake, partitioning, and remobilization in modern soybean varieties. Agron. J. 107, 563–573. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein‐dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes, D.C. , Zayed, A.M. , Ascenzi, R. , McCaskill, A.J. , Hoffman, N.E. , Davis, K.R. and Görlach, J. (2001) Growth stage–based phenotypic analysis of Arabidopsis: a model for high throughput functional genomics in plants. Plant Cell, 13, 1499–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L. , Yuan, H.Y. , Ren, R. , Zhao, S.Q. , Han, Y.P. , Zhou, Q.Y. , Ke, D.X. et al. (2016) Genome‐wide identification, classification, and expression analysis of amino acid transporter gene family in Glycine Max . Front. Plant Sci. 7, 515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J. and Bent, A.F. (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant J. 16, 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeken, R. , Ache, P. , Kajahn, I. , Klinkenberg, J. , Bringmann, G. and Hedrich, R. (2008) Identification of Arabidopsis thaliana phloem RNAs provides a search criterion for phloem‐based transcripts hidden in complex datasets of microarray experiments. Plant J. 55, 746–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr, W.R. , Caviness, C.E. , Burmood, D.T. and Pennington, J.S. (1971) Stage of development descriptions for soybeans, Glycine Max (L.) Merrill. Crop Sci. 11, 929–931. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, W.N. , Loo, D.D. , Koch, W. , Ludewig, U. , Boorer, K.J. , Tegeder, M. , Rentsch, D. et al. (2002) Low and high affinity amino acid H+‐cotransporters for cellular import of neutral and charged amino acids. Plant J. 29, 717–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garneau, M.G. , Tan, Q. and Tegeder, M. (2018) Function of pea amino acid permease AAP6 in nodule nitrogen metabolism and export, and plant nutrition. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 5205–5219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar, A.P. , Laboski, C.A.M. , Naeve, S.L. and Conley, S.P. (2017) Dry matter and nitrogen uptake, partitioning, and removal across a wide range of soybean seed yield levels. Crop Sci. 57, 2170–2182. [Google Scholar]

- Gaufichon, L. , Reisdorf‐Cren, M. , Rothstein, S.J. , Chardon, F. and Suzuki, A. (2010) Biological functions of asparagine synthetase in plants. Plant Sci. 179, 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, E. , Gattolin, S. , Newbury, H.J. , Bale, J.S. , Tseng, H.M. , Barrett, D.A. and Pritchard, J. (2010) A mutation in amino acid permease AAP6 reduces the amino acid content of the Arabidopsis sieve elements but leaves aphid herbivores unaffected. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, F. , Li, S. , Dang, L.J. , Chai, W.T. , Li, P.L. and Wang, N.N. (2012) PL1 fusion gene: a novel visual selectable marker gene that confers tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in transgenic tomato. Transgenic Res. 21, 1057–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.T. , Taylor, W.R. and Thornton, J.M. (1992) The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 8, 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kichey, T. , Hirel, B. , Heumez, E. , Dubois, F. and Le Gouis, J. (2007) In winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), post‐anthesis nitrogen uptake and remobilisation to the grain correlates with agronomic traits and nitrogen physiological markers. Field Crop Res. 102, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. , Stecher, G. and Tamura, K. (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea, U.S. , Slimestad, R. , Smedvig, P. and Lillo, C. (2007) Nitrogen deficiency enhances expression of specific MYB and bHLH transcription factors and accumulation of end products in the flavonoid pathway. Planta, 225, 1245–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine, R. , La Camera, S. , Atanassova, R. , Dédaldéchamp, F. , Allario, T. , Pourtau, N. , Bonnemain, J.L. , et al. (2013) Source-to-sink transport of sugar and regulation by environmental factors. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillo, C. , Lea, U.S. and Ruoff, P. (2008) Nutrient depletion as a key factor for manipulating gene expression and product formation in different branches of the flavonoid pathway. Plant Cell Environ. 31, 587–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. , Gong, Q. , Ma, Y. , Li, P. , Li, J. , Yang, S. , Yuan, L. et al. (2010) cpSecA, a thylakoid protein translocase subunit, is essential for photosynthetic development in Arabidopsis . J. Exp. Bot. 61, 1655–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. , Liu, S. , Chang, D.S. , Wang, L. , Wang, D. and Wang, N.N. (2013) A simple and efficient method for obtaining transgenic soybean callus tissues. Acta Physiol. Plant. 35, 2113–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. and Bush, D.R. (2006) Expression and transcriptional regulation of amino acid transporters in plants. Amino Acids 30, 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourad, G. and King, J. (1995) LO‐Methylthreonine‐resistant mutant of Arabidopsis defective in isoleucine feedback regulation. Plant Physiol. 107, 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, B. , Fastner, A. , Karmann, J. , Mansch, V. , Hoffmann, T. , Schwab, W. , Suter‐Grotemeyer, M. et al. (2015) Amino acid export in developing Arabidopsis seeds depends on UmamiT facilitators. Curr. Biol. 25, 3126–3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemie‐Feyissa, D. , Olafsdottir, S.M. , Heidari, B. and Lillo, C. (2014) Nitrogen depletion and small R3‐MYB transcription factors affecting anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis leaves. Phytochemistry 98, 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offler, C.E. , McCurdy, D.W. , Patrick, J.W. and Talbot, M.J. (2003) Transfer cells: cells specialized for a special purpose. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54, 431–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama, T. , Minagawa, R. , Ishikawa, S. , Yamamoto, M. , Hung, N.V.P. , Ohtake, N. , Sueyoshi, K. , et al. (2013) Soybean seed production and nitrogen nutrition. In A Comprehensive Survey of International Soybean Research-Genetics, Physiology, Agronomy and Nitrogen Relationships ( James, E.B. , ed), pp. 115–157. Rijeka: InTech. [Google Scholar]

- Okumoto, S. , Schmidt, R. , Tegeder, M. , Fischer, W.N. , Rentsch, D. , Frommer, W.B. and Koch, W. (2002) High affinity amino acid transporters specifically expressed in xylem parenchyma and developing seeds of Arabidopsis . J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45338–45346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, J.W. , Offler, C.E. and Bel, A.J.E.V. (2003) Seed development | nutrient loading of seeds. Encyclopedia Appl. Plant Sci. 1240–1249. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, M.M. , Martinez, J.C. , Kalvig, A.B. , Fonger, T.M. and Wang, K. (2006) Improved cotyledonary node method using an alternative explant derived from mature seed for efficient Agrobacterium‐mediated soybean transformation. Plant Cell Rep. 25, 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, B. , Kong, H. , Li, Y. , Wang, L. , Zhong, M. , Sun, L. , Gao, G. et al. (2014) OsAAP6 functions as an important regulator of grain protein content and nutritional quality in rice. Nat. Commun. 5, 4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M. , Hudson, D. , Schofield, A. , Tsao, R. , Yang, R. , Gu, H. , Bi, Y.M. et al. (2008) Adaptation of Arabidopsis to nitrogen limitation involves induction of anthocyanin synthesis which is controlled by the NLA gene. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2933–2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perchlik, M. , Foster, J. and Tegeder, M. (2014) Different and overlapping functions of Arabidopsis LHT6 and AAP1 transporters in root amino acid uptake. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 5193–5204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perchlik, M. and Tegeder, M. (2017) Improving plant nitrogen use efficiency through alteration of amino acid transport processes. Plant Physiol. 175, 235–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppenberger, B. , Berthiller, F. , Lucyshyn, D. , Sieberer, T. , Schuhmacher, R. , Krska, R. , Kuchler, K. et al. (2003) Detoxification of the Fusarium mycotoxin deoxynivalenol by a UDP‐glucosyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana . J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47905–47914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porebski, S. , Bailey, L.G. and Baum, B.R. (1997) Modification of a CTAB DNA extraction protocol for plants containing high polysaccharide and polyphenol components. Plant mol. Biol. Rep. 15, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rentsch, D. , Schmidt, S. and Tegeder, M. (2007) Transporters for uptake and allocation of organic nitrogen compounds in plants. FEBS Lett. 581, 2281–2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, S.W. , Hanway, J.J. , Thompson, H.E. and Benson, G.O. (1994) How a soybean plant develops: Iowa State University of Science and Technology. Special Rep. 53, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rolletschek, H. , Hosein, F. , Miranda, M. , Heim, U. , Gotz, K.P. , Schlereth, A. , Borisjuk, L. et al. (2005) Ectopic expression of an amino acid transporter (VfAAP1) in seeds of Vicia narbonensis and pea increases storage proteins. Plant Physiol. 137, 1236–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, A. , Collier, R. , Trethewy, A. , Gould, G. , Sieker, R. and Tegeder, M. (2009) AAP1 regulates import of amino acids into developing Arabidopsis embryos. Plant J. 59, 540–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, J.P. and Tegeder, M. (2016) Connecting source with sink: the role of Arabidopsis AAP8 in phloem loading of amino acids. Plant Physiol. 171, 508–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, J.P. and Tegeder, M. (2017) Implications of nitrogen phloem loading for carbon metabolism and transport during Arabidopsis development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 59, 409–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, T.R. , Farias, J.R. , Neumaier, N. and Nepomuceno, A.L. (2003) Modeling nitrogen accumulation and use by soybean. Field Crop Res. 81, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Slayman, C.W. (1974) The genetic control of membrane transport. Curr. Top. Membranes Transport 4, 1–174. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.H. , Frommer, W.B. and Ludewig, U. (2004) Molecular and functional characterization of a family of amino acid transporters from arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 136, 3104–3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Q.M. , Grennan, A.K. , Pelissier, H.C. , Rentsch, D. and Tegeder, M. (2008) Characterization and expression of French bean amino acid transporter PvAAP1. Plant Sci. 174, 348–356. [Google Scholar]

- Tegeder, M. (2012) Transporters for amino acids in plant cells: some functions and many unknowns. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15, 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegeder, M. (2014) Transporters involved in source to sink partitioning of amino acids and ureides: opportunities for crop improvement. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 1865–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegeder, M. and Masclaux‐Daubresse, C. (2018) Source and sink mechanisms of nitrogen transport and use. New Phytol. 217, 35–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegeder, M. and Ward, J.M. (2012) Molecular evolution of plant AAP and LHT amino acid transporters. Front. Plant Sci. 3, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegeder, M. , Offler, C.E. , Frommer, W.B. and Patrick, J.W. (2000) Amino acid transporters are localized to transfer cells of developing pea seeds. Plant Physiol. 122, 319–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegeder, M. and Rentsch, D. (2010) Uptake and partitioning of amino acids and peptides. Mol. Plant, 3, 997–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegeder, M. , Tan, Q. , Grennan, A.K. and Patrick, J.W. (2007) Amino acid transporter expression and localisation studies in pea (Pisum sativum). Funct. Plant Biol. 34, 1019–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegeder, M. and Hammes, U.Z. (2018) The way out and in phloem loading and unloading of amino acids. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 43, 16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, J.H. (1980) Kinetics of 14C‐photosynthate uptake by developing soybean fruit. Plant Physiol. 65, 975–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, J.H. (1981) Morphology and ultrastructure of maternal seed tissues of soybean in relation to the import of photosynthate. Plant Physiol. 67, 1016–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilsner, J. , Kassner, N. , Struck, C. and Lohaus, G. (2005) Amino acid contents and transport in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) under different nitrogen conditions. Planta, 221, 328–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart, A.A. and Joy, K.W. (1981) Use of Phloem exudate technique in the study of amino Acid transport in pea plants. Plant Physiol. 68, 750–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. , Wu, B. , Lu, K. , Wei, Q. , Qian, J. , Chen, Y. and Fang, Z. (2019) The Amino Acid Permease 5 (OsAAP5) regulates tiller number and grain yield in rice. Plant Physiol. 180, 1031–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.N. , Shih, M.C. and Li, N. (2005) The GUS reporter‐aided analysis of the promoter activities of Arabidopsis ACC synthase genes AtACS4, AtACS5, and AtACS7 induced by hormones and stresses. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 909–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, D. , Gerlitz, N. and Stadler, R. (2011) A dual switch in phloem unloading during ovule development in Arabidopsis . Protoplasma, 248, 225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wipf, D. , Ludewig, U. , Tegeder, M. , Rentsch, D. , Koch, W. and Frommer, W.B. (2002) Conservation of amino acid transporters in fungi, plants and animals. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, T. , Xiao, D. , Liu, D. , Chai, W. , Gong, Q. and Wang, N.N. (2012) Heterologous expression of ATG8c from soybean confers tolerance to nitrogen deficiency and increases yield in Arabidopsis . PLoS ONE, 7, e37217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, N. , Doelling, J.H. , Falbel, T.G. , Durski, A.M. and Vierstra, R.D. (2000) The ubiquitin‐specific protease family from Arabidopsis. AtUBP1 and 2 are required for the resistance to the amino acid analog canavanine. Plant Physiol. 124, 1828–1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. , Bogner, M. , Stierhof, Y.D. and Ludewig, U. (2010) H+‐independent glutamine transport in plant root tips. PLoS ONE, 5, e8917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. , Garneau, M.G. , Majumdar, R. , Grant, J. and Tegeder, M. (2015) Improvement of pea biomass and seed productivity by simultaneous increase of phloem and embryo loading with amino acids. Plant J. 81, 134–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. , Tan, Q. , Lee, R. , Trethewy, A. , Lee, Y.H. and Tegeder, M. (2010) Altered xylem‐phloem transfer of amino acids affects metabolism and leads to increased seed yield and oil content in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell, 22, 3603–3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.Y. , Xu, Y.L. , Wang, Z. , Zhang, J.F. , Chen, X. , Li, Z.F. , Li, Z.F. et al. (2017) Genome‐wide identification and characterization of an amino acid permease gene family in Nicotiana tabacum . RSC Adv. 7, 38081–38090. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Phylogenetic analysis of GmAAP6a.

Figure S2. GUS staining of GmAAP6a:GmAAP6a‐GUS soybean in roots and flowers.

Figure S3. Genotyping of GmAAP6a‐overexpressing transgenic soybean plants.

Figure S4. GmAAP6a‐overexpressing soybean plants show higher free amino acid content in cotyledon exudates.

Table S1. Free amino acid contents in the cotyledons of TL‐1 and transgenic seedlings under low nitrogen conditions.

Table S2. Free amino acid contents in primary leaves of TL‐1 and transgenic seedlings under low nitrogen conditions.

Table S3. Gene‐specific primers used in this study.