Abstract

Coronavirus infection is associated to life-threatening respiratory failure. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) was recently identified as a host factor for Zika and dengue viruses; AHR antagonists decrease viral titers and ameliorate ZIKV-induced pathology in vivo. Here we report that AHR is activated during coronavirus infection, impacting anti-viral immunity and lung basal cells associated to tissue repair. Hence, AHR antagonists are candidate therapeutics for the management of coronavirus-infected patients.

Keywords: coronavirus, aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation, lung basal cells

Introduction, Results And Discussion

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are positive sense single-stranded RNA viruses of major agricultural and public health importance1. Coronaviruses were considered of low risk to humans until 2002, when a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak occurred in Guangdong, China2–5. Ten years later, the highly pathogenic Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) emerged in the Middle East6. In December, 2019, an epidemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) originated in Wuhan, China7,8. The common symptoms of SARS- CoV-2 infection at onset are fever, fatigue, dry cough, myalgia, and dyspnea9. In5–15 % of the infected patients, the acute form of the disease causes life-threatening progressive respiratory failure8,10,11. The high rate of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 translates into an overwhelming number of patients needing intensive care support, putting an enormous stress on national health systems around the globe. However, no specific therapeutic agents or vaccines are available for COVID-19. Thus, there is an urgent unmet clinical need for candidate targets to treat and prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The ligand-activated transcription factor aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) controls multiple aspects of the immune response12,13. AHR activation by metabolites produced by tumors14,15 or in the context of viral infection16 interferes with the generation of protective immunity. Indeed, AHR suppresses the production of type I interferons (IFN-I)17,18, probably as part of a feedback negative mechanism because IFN-I induce AHR expression19. We recently showed that AHR activation during the infection with Zika or dengue virus suppresses IFN-I- dependent and IFN-I-independent anti-viral innate and intrinsic immunity17. Most importantly, an AHR antagonist optimized for human use boosted anti-viral immunity, interfered with viral replication and ameliorated multiple aspects of Zika congenital syndrome including microcephaly in animal models17, identifying AHR as a candidate target for therapeutic intervention. Based on these findings and the urgent need for therapies for SARS-CoV-2, we investigated the potential role of AHR in coronavirus infection.

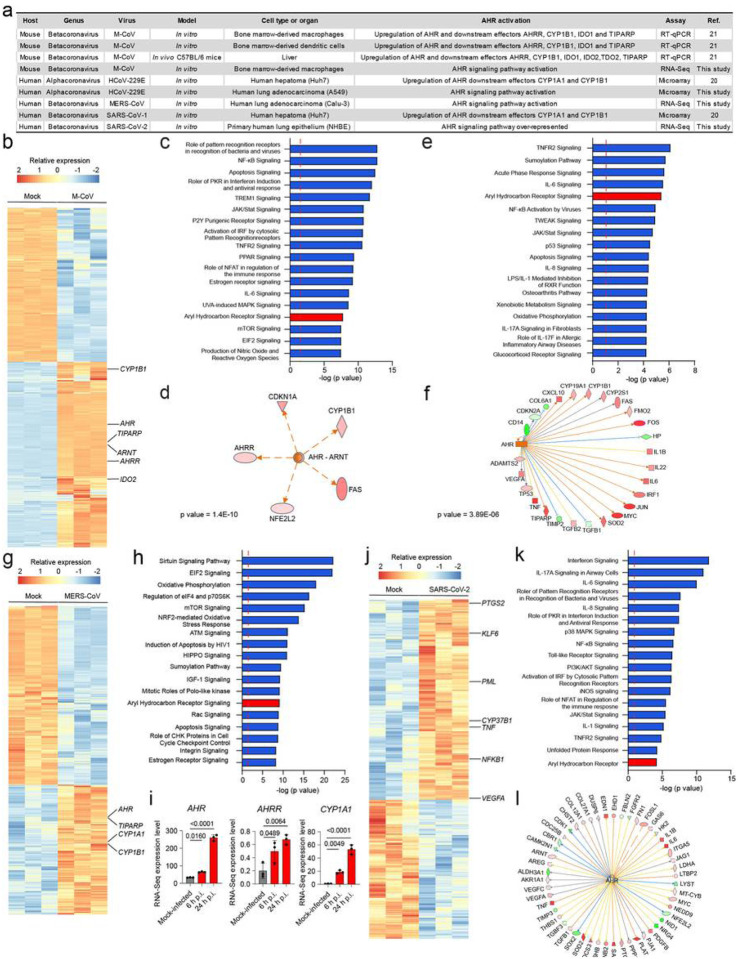

Early studies using gene expression microarrays analyzed the transcriptional response to infection by multiple coronaviruses, including the murine coronavirus (M-CoV) of the betacoronavirus genus, and the human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) usually associated to common cold. We detected increased expression of the AHR transcriptional targets CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 in response to M-CoV and HCoV-229E infection (Fig. 1a). These findings were confirmed by a recent study which analyzed the transcriptional response to M-CoV infection in vitro and in vivo20. We also detected the activation of AHR signaling in M-CoV21, HCoV-229E22, MERS-CoV23, SARS-CoV-120 and SARS-CoV-224 gene expression data available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) public database (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

AHR signaling is associated to infection with multiple coronaviruses. (a) Activation of AHR signaling upon infection with different members of the Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus genus of the Coronaviridae family (b) Heatmap showing gene expression detected by RNA-seq analysis of mock-infected and M-CoV-infected bone marrow-derived macrophages (n=3 independent experiments per condition) (c) Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) of pathways enriched in M-CoV-infected cells compared to mock-infected cells (n=3 independent experiments per condition). Dashed red line indicates p=0.05. p values were determined using a Fisher’s exact test. (d) IPA identifies AHR as an upstream regulator. p value was determined using a Fisher’s exact test. (e) IPA of pathways enriched in HCoV-229E- infected cells compared to mock-infected human lung adenocarcionma (A549) cells (n=3 independent experiments per condition). Dashed red line indicates p=0.05 (f) IPA identifies AHR as an upstream regulator in the infected samples. p value was determined using a Fisher’s exact test. (g) Heatmap showing gene expression detected by RNA-seq analysis of mock-infected and MERS-CoV-infected human lung adenocarcinoma (Calu-3) cells (n=3 independent experiments per condition) (h) IPA of pathways enriched in MERS-CoV-infected cells compared to mock- infected cells (n=3 independent experiments per condition). Dashed red line indicates p=0.05. p values were determined using a Fisher’s exact test. (i) Expression levels of AHR, AHRR and CYP1A1 determined at different times post infection by RNA-Seq (n=3 independent experiments per condition) (j) Heatmap showing gene expression detected by RNA-seq analysis of mock-infected and SARS-CoV-2-infected human primary lung epithelium cells (n=3 independent experiments per condition) (k) IPA of pathways enriched in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells compared to mock-infected cells (n=3 independent experiments per condition). Dashed red line indicates p=0.05. p value was determined using a Fisher’s exact test. (l) IPA identifies AHR as an upstream regulator in the infected samples. p value determined using a Fisher’s exact test.

In depth analyses of RNA-Seq data from M-CoV infected bone marrow-derived macrophages detected the up-regulation of AHR and related genes such as IDO2, CYP1B1, AHRR and TIPARP (Fig 1b). IDO2 catalyzes the production of AHR agonists in the context of tumors25 and viral infections17,26, and TIPARP contributes to the suppression of IFN-I expression18. Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) detected the enrichment of pattern recognition receptors and immune cell signaling molecules involved in antiviral IFN-related mechanisms, including NF-κB, JAK/Stat, PKR, IRF and IL-6, as well as a significant enrichment in AHR signaling (Fig. 1c). Moreover, upstream analysis identified AHR-ARNT as candidate regulators of the transcriptional response to M-CoV infection. These findings suggest that AHR participates in the transcriptional response of M-CoV infected cells (Fig. 1d).

Next, we analyzed a dataset of HCoV-229E infected A549 cells; IPA analysis detected AHR among the most highly enriched pathways in infected cells. Moreover, we identified AHR as a regulator of the transcriptional response of infected samples (Figs. 1e,f). The analysis of RNA-seq data from MERS-CoV infected human lung adenocarcinoma (Calu-3) cells detected the up-regulation of AHR and related genes (CYPA1, CYP1B1 and TIPARP) (Fig. 1g). Accordingly, IPA detected the activation of a broad range of cellular processes, including AHR signaling (Fig. 1h). Of note, AHR, AHRR and CYP1A1 expression determined by RNA-seq was found to be gradually up-regulated at different times post infection (Fig. 1i). Finally, we analyzed RNA-seq data of mock-infected and SARS-CoV-2 infected human primary lung epithelium cells. IPA of differentially expressed genes in SARS-CoV-2 infected cells compared to mock-infected cells detected the activation of the AHR pathway, together with IFN signaling, NF-KB, JAK/Stat and others (Figs. 1j,k). In addition, AHR was also identified as an upstream regulator of relevant cytokines and chemokines involved in the response to viral infection and in ammation-related cellular processes (Fig. 1l).

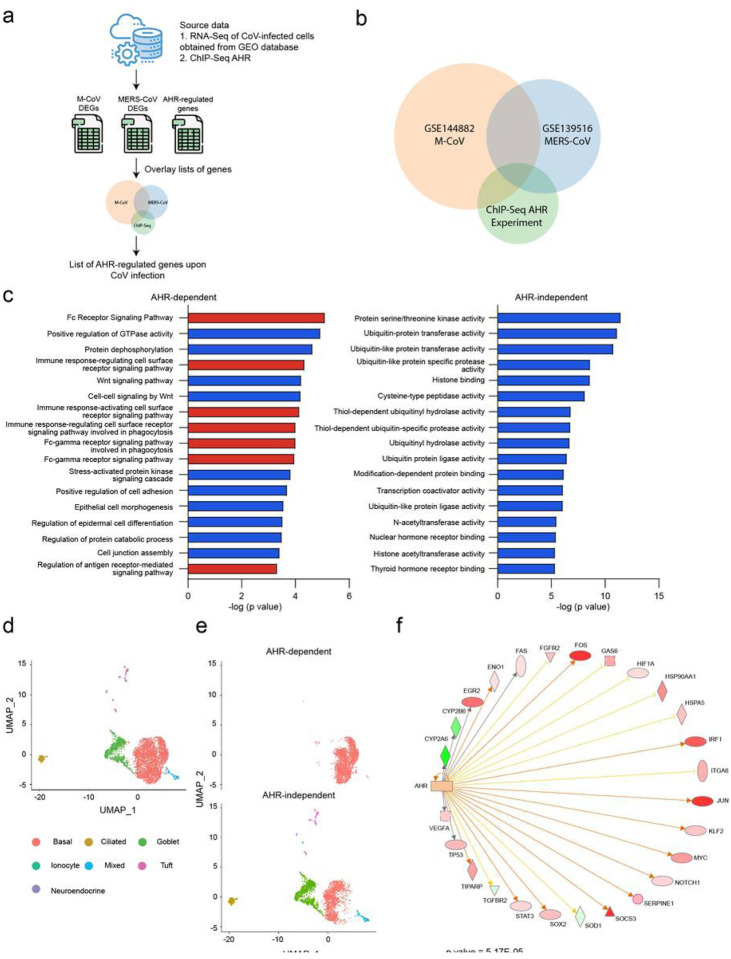

We used a dataset of AHR targets identified in genome-wide ChIP-seq studies to define the AHR-dependent module in the transcriptional response to coronavirus, focusing on M-CoV and MERS-CoV for which the available datasets were most complete (Figs. 2a,b). The pathway enrichment analysis of the AHR-dependent and the AHR-independent components of the transcriptional response to coronavirus infection detected an enrichment in biological pathways related to the immune response and Fc signaling in the AHR-dependent transcriptional module (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Identification of an AHR-dependent module in the transcriptional response to coronavirus infection. (a) Strategy used to identify AHR-dependent modules in the transcriptional response to coronavirus infection. Significantly up-regulated genes in each RNA- seq dataset were overlapped with genes associated to peaks identified by AHR ChIP-seq within 1 kilobase distance to the transcription start region. (b) Venn diagram representing the overlap in significantly up-regulated genes in M-CoV-infected cells, MERS-CoV-infected cells and the ones identified by an AHR ChIP-Seq experiment. (c) Pathway enrichment analysis was performed on two gene sets: the one resulting from the overlap of the three datasets in (b) (“AHR”) and the one resulting from the overlap between the M-CoV and MERS-CoV datasets in (b) (“non-AHR”). p value was determined using a Fisher’s exact test. Pathways colored in red are related to immunity (d) Single cell RNA-sequencing data of mouse trachea epithelia cells. Each cell is labelled by the cell type. (e) “AHR-dependent” and a “AHR-independent” cell populations identified by gene set enrichment analysis using the previously generated gene set (f) Upstream regulator analysis on the AHR activated cell population compared to the non-AHR activated cell population identified AHR as an upstream regulator.

In about 5–15% of infected patients, SARS-CoV-2 infection causes life-threatening respiratory complications10,11. To investigate potential AHR-dependent mechanisms that may contribute to the pathogenesis of COVID-19, we analyzed a single-cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-seq) dataset of lung epithelial cells, identifying six cell populations corresponding to basal cells, goblet cells, ciliated cells, Tuft cells, neuroendocrine cells and pulmonary ionocytes (Fig. 2d). Strikingly, the AHR-dependent transcriptional module induced by coronavirus infection was mostly associated to basal cells (Fig. 2e), which contribute to lung regeneration after multiple types of injuries including influenza infection27. Interestingly, IPA analysis of the scRNA-seq dataset of lung epithelial cells identified AHR as a transcriptional regulator of the basal cell cluster (Fig. 2f). These findings suggest that AHR signaling triggered by coronavirus infection interferes with the regenerative activity of lung epithelial basal cells.

In summary, we identified AHR signaling as a common host response to infection by multiple coronaviruses. It has been reported that although some NF-κB signaling is needed for coronavirus replication, excessive activation of this pathway may be deleterious for the virus22. AHR limits NF- B activation, and interferes with multiple anti-viral immune mechanisms including IFN-I production and intrinsic immunity17,18. Thus, our findings suggest that the modulation of NF-kB signaling via AHR may dampen the immune response against coronavirus. We also detected a potential role of AHR in the control Fc receptor expression and signaling. Based on recent reports on the association of high antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 with worst clinical outcomes28, these findings suggest a role for antibody enhancement in COVID-19 pathogenesis.

Our studies also suggest that AHR signaling associated to coronavirus infection affects lung basal cells, which give rise to stem cells involved in lung repair in multiple contexts including influenza virus infection29–31. Of note, AHR-deficient mice show enhanced repair of the lung bronchiolar epithelium following naphthalene injury32, concomitant with the increase proliferation and the earlier activation of basal cells. Taken together, these findings suggest that AHR signaling associated to coronavirus infection may interfere with the activity of basal cells, contributing to the lung pathogenesis associated to SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Of note, although lung basal cells do not constitutively express ACE2, the cellular entry receptor for SARS-CoV-133 and SARS-CoV-28,27, IFN-I drive ACE2 expression on primary human upper airway basal cells34. Thus, AHR signaling may be induced in basal cells following their infection, or indirectly via the up-regulation of enzymes involved in the production of AHR agonists in other cells. Indeed, TDO and IDO2 expression is up-regulated in response to viral infection17, probably as part of a mechanism that limits immunopathology35 but is exploited by pathogens to evade the immune-response. Most importantly, AHR antagonists activate anti-viral immunity, decrease viral titers and virus-induced pathology in the context of Zika and dengue virus infection17. Thus, AHR antagonists developed for clinical use may provide novel approaches for the treatment of COVID-19 patients.

Methods

RNA-sequencing alignment and quantification.

The raw fastq les for all samples were downloaded and aligned to Human (GRCh38) and Mouse (GRCm38) reference genome using STAR v2.7.3a36. Then the aligned reads were quantified using Rsem v1.3.137.

Differential expression analysis.

The count matrix was built using the Rsem output for each sample, and then DESeq238 was used to conduct differential expression analysis. The log2 fold change in the results was shrunk using Apeglm39.’

Downstream analysis.

Differentially expressed genes were further analyzed using GSEA40 and IPA in order to find enriched pathways and upstream regulators.

Overlap between the ChIP-seq and bulk RNA-sequencing results.

The list of AHR target genes, generated from a ChIP-seq dataset41, was overlapped with the lists of differentially expressed genes from M-CoV and MERS-CoV-infected samples using the threshold of log2 fold change larger than 0 and adjusted p value smaller than 0.05. Then the results were further overlapped to generate a list of up-regulated genes common to all virus-infected samples and ChIP-seq identified AHR targets.

Download and processing of data.

The single cell dataset was downloaded from the GEO repository (GSE103354). The 10X format count matrices were downloaded and processed using Seurat42 including normalization, dimension reduction and clustering. Then for each cluster the GSEA was used to analyze the differential expression analysis results of each cluster with the AHR activation signature generated in the previously. The clusters that had significant up- regulation in AHR activation signature (FDR < 0.25) are marked as “AHR-dependent” and other clusters are marked as “AHR-independent”. Then MAST43 was used to conduct the differential expression analysis between the AHR activated population and non AHR activated population.

Downstream analysis.

Differentially expressed genes were further analyzed using GSEA and IPA in order to find enriched pathways and upstream regulators.

Cell-trajectory and pseudo-time analysis.

The single cell dataset was further analyzed using monocle44. The pseudo-time order of the cells were constructed using the genes that were differentially expressed (p adjusted value < 0.01) between the AHR and the non-AHR activated population.

Data availability.

The authors declare that the raw data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available. Transcriptomics data (RNA-Seq or microarray) from virus-infected samples, including M-CoV, HCoV-229E, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 were accessed at GSE144882, GSE89167, GSE139516, and GSE147507 respectively. Trachea epithelial single cell data was accessed at GSE103354.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by grants NS102807, NS087867, ES02530, AI126880, AI093903 and AI100190 from the National Institutes of Health, USA and RG4111A1 and JF2161-A-5 from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society to FJQ. FJQ received support from the International Progressive MS Alliance. C.C.G. was supported by Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA) (20020160100091BA), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas (CONICET) (PIP11220170100171CO) and Agencia de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCyT) (BID-PICT 3080). C.C.G is member of the Research Career CONICET. We thank all members of the Garcia and Quintana laboratories for helpful advice and discussions.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

FJQ is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Kyn Therapeutics. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Cybele C. Garcia, Universidad de Buenos Aires

Francisco J. Quintana, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

References

- 1.Cui J., Li F. & Shi Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nature reviews. Microbiology 17, 181–192 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drosten C., et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. The New England journal of medicine 348, 1967–1976 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fouchier R.A., et al. Aetiology: Koch’s postulates fulfilled for SARS virus. Nature 423, 240 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ksiazek T.G., et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. The New England journal of medicine 348, 1953–1966 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong N.S., et al. Epidemiology and cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Guangdong, People’s Republic of China, in February, 2003. Lancet (London, England) 362, 1353–1358 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D. & Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. The New England journal of medicine 367, 1814–1820 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu N., et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. The New England journal of medicine 382, 727–733 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou P., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang D., et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guan W.J., et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. The New England journal of medicine (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grasselli G., Pesenti A. & Cecconi M. Critical Care Utilization for the COVID-19 Outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: Early Experience and Forecast During an Emergency Response. Jama (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutierrez-Vazquez C. & Quintana F.J. Regulation of the Immune Response by the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Immunity 48, 19–33 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothhammer V. & Quintana F.J. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: an environmental sensor integrating immune responses in health and disease. Nature reviews. Immunology 19, 184–197 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takenaka M.C., et al. Control of tumor-associated macrophages and T cells in glioblastoma via AHR and CD39. Nat Neurosci 22, 729–740 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opitz C.A., et al. An endogenous tumour-promoting ligand of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 478, 197–203 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence B.P. & Vorderstrasse B.A. New insights into the aryl hydrocarbon receptor as a modulator of host responses to infection. Seminars in Immunopathology 35, 615–626 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giovannoni F., et al. AHR is a Zika virus host factor and a candidate target for antiviral therapy. Nat Neurosci (In press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamada T., et al. Constitutive aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling constrains type I interferon-mediated antiviral innate defense. Nature immunology 17, 687–694 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothhammer V., et al. Type I interferons and microbial metabolites of tryptophan modulate astrocyte activity and central nervous system in ammation via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nat Med 22, 586–597 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grunewald M.E., Shaban M.G., Mackin S.R., Fehr A.R. & Perlman S. Murine Coronavirus Infection Activates the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in an Indoleamine 2,3- Dioxygenase-Independent Manner, Contributing to Cytokine Modulation and Proviral TCDD-Inducible-PARP Expression. J Virol 94(2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng X., et al. Coronavirus Interferon Antagonists Differentially Modulate the Host Response during Replication in Macrophages. bioRxiv, 782409 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poppe M., et al. The NF-kappaB-dependent and -independent transcriptome and chromatin landscapes of human coronavirus 229E-infected cells. PLoS Pathog 13, e1006286 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X., et al. Competing endogenous RNA network profiling reveals novel host dependency factors required for MERS-CoV propagation. Emerg Microbes Infect 9, 733–746 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanco-Melo D., et al. SARS-CoV-2 launches a unique transcriptional signature from in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo systems. bioRxiv, 2020.2003.2024.004655 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemos H., Huang L., Prendergast G.C. & Mellor A.L. Immune control by amino acid catabolism during tumorigenesis and therapy. Nature reviews. Cancer 19, 162–175 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Favre D., et al. Tryptophan catabolism by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 alters the balance of TH17 to regulatory T cells in HIV disease. Science translational medicine 2, 32ra36 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao J., et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. medRxiv, 2020.2003.2002.20030189 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaughan A.E., et al. Lineage-negative progenitors mobilize to regenerate lung epithelium after major injury. Nature 517, 621–625 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y., et al. Spatial-Temporal Lineage Restrictions of Embryonic p63(+) Progenitors Establish Distinct Stem Cell Pools in Adult Airways. Developmental cell 44, 752–761.e754 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuo W., et al. p63(+)Krt5(+) distal airway stem cells are essential for lung Nature 517, 616–620 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morales-Hernandez A., et al. Lung regeneration after toxic injury is improved in absence of dioxin receptor. Stem Cell Res 25, 61–71 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W., et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 426, 450–454 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montoro D.T., et al. A revised airway epithelial hierarchy includes CFTR-expressing ionocytes. Nature 560, 319–324 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bessede A., et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor control of a disease tolerance defence pathway. Nature 511, 184–190 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobin A., et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li B. & Dewey C.N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC bioinformatics 12, 323 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Love M.I., Huber W. & Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome biology 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu A., Ibrahim J.G. & Love M.I. Heavy-tailed prior distributions for sequence count data: removing the noise and preserving large differences. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 35, 2084–2092 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramanian A., et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lo R. & Matthews J. High-resolution genome-wide mapping of AHR and ARNT binding sites by ChIP-Seq. Toxicol Sci 130, 349–361 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Satija,, Farrell J.A., Gennert D., Schier A.F. & Regev A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nature biotechnology 33, 495–502 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finak G., et al. MAST: a exible statistical framework for assessing transcriptional changes and characterizing heterogeneity in single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome biology 16, 278 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qiu X., et al. Reversed graph embedding resolves complex single-cell Nature methods 14, 979–982 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the raw data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available. Transcriptomics data (RNA-Seq or microarray) from virus-infected samples, including M-CoV, HCoV-229E, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 were accessed at GSE144882, GSE89167, GSE139516, and GSE147507 respectively. Trachea epithelial single cell data was accessed at GSE103354.