Abstract

The Patagonian fungal endophyte NRRL 50072 is reported to produce a variety of medium-chain and highly branched volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that have been highlighted for their potential as fuel alternatives and are collectively termed myco-diesel. To assess the novelty of this observation, we determined the extent to which ten closely related Ascocoryne strains from commercial culture collections possess similar VOC production capability. DNA sequencing established a high genetic similarity between NRRL 50072 and each Ascocoryne isolate, consistent with its reassignment as Ascocoryne sarcoides. The Ascocoryne strains did not produce highly branched medium-chain-length alkanes, and efforts to reproduce the branched alkane production of NRRL 50072 were unsuccessful. However, we confirmed the production of 30 other products and expanded the list of VOCs for NRRL 50072 and members of the genus Ascocoryne. VOCs detected from the cultures consisted of short- and medium-chain alkenes, ketones, esters and alcohols and several sesquiterpenes. Ascocoryne strains NRRL 50072 and CBS 309.71 produced a more diverse range of volatiles than the other isolates tested. CBS 309.71 also showed enhanced production compared with other strains when grown on cellulose agar. Collectively, the members of the genus Ascocoryne demonstrated production of over 100 individual compounds, with a third of the short- and medium-chain compounds also produced when cultures were grown on a cellulose substrate. This comparative production analysis could facilitate future studies to identify and manipulate the biosynthetic machinery responsible for production of individual VOCs, including several that have a potential application as biofuels.

Keywords: CTP, tricarboxylate transport protein; EI, electron impact; GC, gas chromatography; ITS, internal transcribed spacer; SPME, solid phase microextraction; VOC, volatile organic compound

INTRODUCTION

Fungi represent a rich source of bioactive natural products and have been studied for their production of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) (McAfee & Taylor, 1999; Strobel, 2006; Strobel et al., 2001). Microbial VOCs are typically low-molecular-mass organics derived from both primary and secondary metabolism pathways that include compounds used as industrial chemicals and aroma components (Korpi et al., 2009). Common VOCs such as 3-methyl-1-butanol are also recent targets for biofuel alternatives (Atsumi et al., 2008; Connor et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2008). Some of these alcohols are derived from branched-chain amino acid metabolism, and their increased carbon content and higher compatibility with existing engine and fuel transportation technologies make them a more attractive biofuel target than ethanol (Fortman et al., 2008; Hill et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008).

Volatile compounds equivalent to components in current fossil fuel formulations were recently reported from the fungus NRRL 50072, an endophyte isolated from Eucryphia cordifolia in northern Patagonia (Stinson et al., 2003; Strobel et al., 2008). The VOC profile reported for NRRL 50072 included medium-chain-length branched hydrocarbons and other organic derivatives. NRRL 50072 was also tested for hydrocarbon production when grown on a cellulose substrate to probe its conversion of cellulosic biomass to potential alternative fuel sources. The volatile products were termed ‘myco-diesel’ because of their fungal source and their similarity to compounds found in diesel fuel (Fortman et al., 2008; Strobel et al., 2008). Further investigation of NRRL 50072 is required to understand the extent of VOC production and inform future metabolic engineering for potential alternative fuel development. Although some NRRL 50072 VOCs are common fungal and bacterial volatiles, other compounds, such as the highly branched alkanes, represent novel products (Korpi et al., 2009; Schulz & Dickschat, 2007; Strobel et al., 2008). It is of interest to also consider VOC production capabilities by closely related species to assess the product novelty and to determine the machinery responsible for biosynthetic production.

The extent of VOC production by related organisms is unknown, partially due to uncertainty in NRRL 50072 taxonomy. In the original description of NRRL 50072, the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence did not provide any meaningful results in a blast search with GenBank due to the lack of sequences with either high sequence homology or related morphology at that time (Stinson et al., 2003). Classification of NRRL 50072 was therefore guided by morphological characterization and the isolate was identified as a Gliocladium species (Stinson et al., 2003). A second phylogenetic sequence analysis performed 5 years later indicated that NRRL 50072 is a close relative of Ascocoryne sarcoides, an ascomycete in the class Leotiomycetes (Strobel et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2006). A. sarcoides is phylogenetically distant from the original taxonomic assignment Gliocladium roseum, which belongs to the class Sordariomycetes (Rehner & Samuels, 1994). This reassignment was further validated during a study of Ascocoryne turficola that incorporated NRRL 50072 ITS sequence data into an Ascocoryne phylogeny. Identified as ‘Plant endophyte MSU 2259 Chile’, NRRL 50072 clustered closely with other A. sarcoides strains (Bunyard et al., 2008).

A. sarcoides is a wood-destroying saprophytic ascomycete (Pavlidis et al., 2005; Roll-Hansen & Roll-Hansen, 1980). Twenty-eight strains in the genus Ascocoryne are available from the American type Culture Collection (ATCC) and Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS) spanning three species, A. sarcoides, Ascocoryne cylichnium and Ascocoryne solitaria. Almost half of these strains were originally isolated in Norway and 10 are from the Norway spruce, Picea abies (Müller & Hallaksela, 2000; Pavlidis et al., 2005; Roll-Hansen & Roll-Hansen, 1980). Three Canadian strains are the only deposited Ascocoryne species isolated outside Europe.

Several strains within the genus Ascocoryne, including A. cylichnium ATCC 44015, have been examined for their sterol and fatty acid profiles from cellular extracts (Müller & Hallaksela, 1994; Müller et al., 1994), but no organisms in this genus other than NRRL 50072 have been studied for their VOC production capabilities. We therefore selected several Ascocoryne isolates deposited in ATCC and CBS to survey their ability to produce VOCs similar to those reported for NRRL 50072. Here, we report VOC production from 10 diverse members of the genus Ascocoryne under a series of growth and nutrient conditions and a re-examination of the VOC profile of NRRL 50072.

METHODS

Culture sourcing.

Cultures were obtained through the ATCC and CBS collection. All cultures were maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates [24 g potato dextrose broth (PDB), 15 g agar (both BD Difco), 1 l distilled water] stored at 23 °C, and 5 mm culture plugs used for inoculations were derived from these source plates.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

For genomic DNA isolation, the ordered isolates were cultured on PDA for approximately 3 weeks. Genomic DNA was isolated using the Plant DNeasy MiniPrep kit (Qiagen) with modifications as follows. Mycelia were harvested (100 mg) and subjected to seven freeze–thaw cycles (−195 °C, 65 °C) before adding 400 μl buffer AP1, 4 μl 100 mg RNase ml−1 and 4 μl 10 mg proteinase K ml−1 (Sigma). Two 10 min heating cycles at 65 °C were each followed by mechanical homogenization. Homogenized material was used to complete the remainder of the Qiagen protocol. The ITS rDNA region was amplified using ITS1 and ITS4 as described by White et al. (1990). Primers 4079F and 4079R (Supplementary Table S1, available with the online version of this paper) were used to amplify the third intron of the tricarboxylate transport protein, following the ITS thermocycler program, but with an annealing temperature of 60 °C. DNA product size was verified with 0.8 % agarose gel electrophoresis and purified from the reaction vessel by using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Products were sequenced at the W. M. Keck DNA sequencing facility using 5 μl DNA, 2 μl 4 mM primer, 11 μl H2O (Yale University). Data quality assessment and consensus sequence generation were performed using the Staden 2.0.0b6 package (preGap4 and Gap4). Sequence data were aligned using Muscle 3.7 (Edgar, 2004), cleaned with Phyutility (Smith & Dunn, 2008), and ends were truncated in Jalview 2.4.0b2 (Waterhouse et al., 2009). Trees were built using mrbayes 3 with a GTR+G+I model and 1×106 generations for two runs of four chains; trees were visualized with FigTree v1.1.2 (Rambaut, 2008; Ronquist & Huelsenbeck, 2003). All sequences were deposited in GenBank (see Supplementary Table S2, available with the online version of this paper, for accession numbers).

Culturing ATCC and CBS Ascocoryne strains for VOC analysis.

Cultures were grown under microaerophilic conditions in 20 ml clear glass vials with screw caps sealed with PTFE/Silicone septa (Supelco). Oatmeal agar (OA) was prepared by boiling oatmeal [25 g (l dH2O)−1] for 30 min and filtering through cheesecloth, following by the addition of agar (15 g l−1, BD Difco). The cellulose agar (CA) contained a mixture of salt and cofactors [2 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g MgSO4•7H2O, 0.5 g CaCl2, 2 g NaNO3, 1 g NH4Cl, 1 mg boric acid, 1 mg ZnSO4•7H2O, 5 mg MnSO4•4H2O, 5 mg FeCl3•6H2O, 5 mg CuSO4•5H2O, 50 μg biotin, 50 μg thiamine HCl, 5 mg inositol, 10 μg pantothenoic acid, 50 μg pyridoxine HCl, 50 μg NAD, 50 μg FMN, 50 μg vitamin B12, 50 μg FAD; all l−1], 25 g l−1 microcrystalline cellulose (Alfa Aesar), and 15 g agar l−1 (BD). The pH of the minimal CA medium was adjusted to 6.0 with 1 M NaOH. (Salts and cofactors were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and BD.) Each vial was filled with a 10 ml slant of autoclave-sterilized medium. Inoculated vials were sealed and grown at 23 °C for 18 days. Three biological replicates of each strain were inoculated to assess reproducibility of VOC production. Un-inoculated vials served as controls to account for media-derived volatiles.

Culturing NRRL 50072 for VOC analysis.

In addition to the conditions described for the Ascocoryne cultures, NRRL 50072 was also tested for VOC production following growth in a variety of conditions. To examine the influence of media sources on VOC production, OA medium was also prepared from oatmeal agar (BD Difco, 72.5 g l−1) as directed. An alternative minimal medium base was prepared for CA using the M1-D recipe (Pinkerton & Strobel, 1976). NRRL 50072 was grown on BD Difco OA and M1-D CA in both 20 ml vials and 250 ml brown glass bottles (Supelco). Bottles were filled with a 100 ml slant of medium and inoculated from culture plugs; cultures were grown for 18 days. Vials were prepared as described above.

Liquid minimal media were prepared with the same salts and cofactors base used for the initial CA medium without the addition of agar and by replacing cellulose with sodium acetate (4.1 g anhydrous NaOAc l−1), glucose (15 g l−1) or cellobiose (20 g l−1). The glucose minimal medium base did not include an ammonium source (NH4Cl). All minimal media were adjusted to pH 6.0 with 1 M NaOH. PDB (EMD chemicals) and PDA (BD Difco) were made with 24 g potato dextrose l−1 and 15 g agar for solid medium. All cultures grown in vials and bottles were sealed and incubated at 23 °C. All liquid flask cultures were sealed with sterilized foil caps and incubated at 23 °C shaking at 150 r.p.m.

Solid phase microextraction (SPME)-GC/MS analysis of VOCs.

A CTC CombiPAL Autosampler (Leap Technologies) was used for automated culture sampling of vial cultures via 50/30 μm divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane StableFlex SPME Fiber (Supelco). Culture headspace samples were analysed using a gas chromatograph A7890 coupled to a time-of-flight mass spectrometer (GCT Premier, Waters). Compounds were loaded via the SPME fiber onto the GC column at 240 °C splitless injection for 30 s with a 0.75 mm ID injection port liner, and were separated on a DB-WAX column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.50 μm film thickness; Phenomenex). An internal standard, 2-heptanone, was loaded onto the pre-conditioned SPME fiber (2 min, 250 °C) for 30 s at 30 °C before sample exposure [20 ml vial with 4 g pump oil and 10 μl 2-heptanone (1 mg methanol ml−1)] (Setkova et al., 2007). Samples were exposed to the fiber for 35 min at 30 °C. The SPME fiber was conditioned after each run to prevent carry-over (2 min, 250 °C). The GC temperature programme was held at 30 °C for 2 min after injection, and increased to 220 °C at 7 °C min−1 with a constant flow rate of 1 ml min−1 Ultra High Purity Helium (Airgas East). Electron impact (EI) spectra were obtained from EI ionization at 70 eV (source temperature 150 °C) and data were collected over the mass range 50–650 Da. Manual headspace sampling of 250 ml bottle and 100 ml flask cultures of NRRL 50072 used the following sampling parameters: pre-condition fiber (12 min, 250 °C), sample extraction (35 min, room temperature), splitless-injection (30 s, 240 °C). No standard was used for manually sampled cultures. GC oven and MS ionization and detection parameters were identical to those described for autosampler runs. Culture replicates for each growth condition were analysed via SPME-GC/MS twice, except where noted, providing up to six analyses per experiment.

Data were analysed by using the MassLynx Software Suite (Waters). Chromatographic peaks were initially identified through spectral search comparisons with the Wiley Registry of Mass Spectral Data, 8th Edition, containing EI spectra from over 390 000 compounds, and elemental composition analysis using exact mass accuracy. Manual inspection of spectral matches and peak content further confirmed compound assignments and detected evidence of impurities or co-elution. Identifications were verified through comparison of retention times and spectra with pure standards for the compounds were noted (Sigma Aldrich). The mass spectra of the sesquiterpenes, eluting between 16 and 24 min under the described GC temperature program, included the parent ion, m/z=204, and an elemental composition analysis supported the molecular formula C15H24. For the terpenes, VOC tables report the number of distinctly eluting compounds detected in all replicates for each culture. Chromatographic peaks resulting from the SPME fiber or inlet septum, including siloxane derivatives, were excluded from the analysis. Compounds identified in the blank media were also removed from the final data analysis. Peak heights and areas relative to the internal standard 2-heptanone were used to estimate levels of production for each compound (#–#####).

RESULTS

Cultures of ten species of the genus Ascocoryne were chosen from ATCC and CBS to represent the species diversity, geographical distribution of isolation sites and range of host plant sources within the culture collections (Table 1). The strains selected for comparative VOC analysis comprise three species based on the taxonomic classifications provided within each culture collections' database, including five A. sarcoides, four A. cylichnium and one A. solitaria. These strains were isolated from seven countries and eight different plant sources between 1913 and 1984.

Table 1.

Culture collection and isolation sources for Ascocoryne strains

| Culture ID no. | Organism | Culture collection | Isolation | Deposition year | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Host | Year | ||||

| 170.56 | A. sarcoides | CBS | UK | Nothofagus sp. | 1913 | 1956 |

| 171.56 | A. sarcoides | CBS | Germany | Pinus contorta | 1913 | 1956 |

| 192.62 | A. sarcoides | CBS | France | Unknown | Unknown | 1962 |

| 246.80 | A. sarcoides | CBS | Norway | Picea abies | 1966 | 1980 |

| 251.80 | A. cylichnium | CBS | Norway | Picea abies | 1966 | 1980 |

| 309.71 | A. cylichnium | CBS | Switzerland | Quercus wood | 1967 | 1971 |

| 738.84 | A. solitaria | CBS | Netherlands | Angiosperm wood | 1984 | 1984 |

| 44013 | A. sarcoides | ATCC | Norway | Malus domestica | 1966 | Unknown |

| 44015 | A. cylichnium | ATCC | Norway | Picea abies stump | 1968 | Unknown |

| 64109 | A. sarcoides | ATCC | Canada | Betula alleghaniensis | Unknown | Unknown |

Phylogenetic analysis

Initial taxonomic assignments were based on identifications provided within each culture collections' database (Table 1), but the ten cultures were deposited in collections before the advent of routine DNA sequencing. Uncertainties in the morphological identification of Ascocoryne species necessitate the genetic examination of each isolate to verify species assignment (Roll-Hansen & Roll-Hansen, 1979).

The ITS region is commonly used for sequence comparisons to assess the relationships between closely related fungi and to help define taxonomic boundaries (White et al., 1990). For all ten cultures, the sequence of the PCR-amplified ITS region matched most closely with an Ascocoryne species when searched against the GenBank database (megablast, blastn). All strains, with the exception of CBS 309.71 and CBS 192.62, also matched most closely at the species level to their designated taxonomy. CBS 309.71 was deposited as an A. cylichnium species, but the most closely aligned sequence was A. sarcoides (GenBank accession no. GC411510). This sequence was also the highest match for five of the cultures deposited as A. sarcoides in the culture collections. A similar inconsistency was observed for CBS 192.62, which was deposited as an A. sarcoides strain, but the closest GenBank match was with A. cylichnium (A789395).

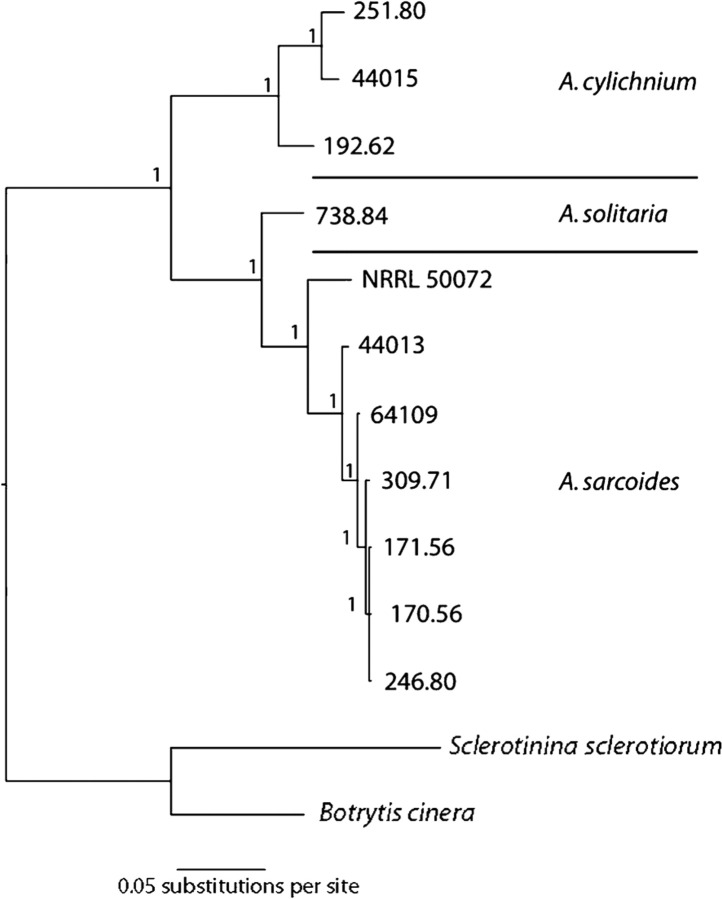

The ITS region gave an insufficient phylogenetic signal to partition the A. sarcoides clade in a phylogenetic reconstruction, so we explored other regions of high variability. Bioinformatic analysis of the NRRL 50072 genome (data not shown) established that the tricarboxylate transport protein (CTP) contains a long intron that could be captured with a single sequencing reaction. The ITS and CTP sequences from each isolate were combined into a concatenated dataset and a Bayesian analysis was used to generate a consensus phylogeny (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1, available with the online version of this paper) (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck, 2003; White et al., 1990). The topology of the consensus phylogram has clear divisions between A. sarcoides, A. cylichnium and A. solitaria strains with uniformly high Bayesian posterior probabilities (Fig. 1). All strains were more closely related to each other than to other genera in the family Helotiaceae (Supplementary Fig. S1). Based upon these observations, CBS 309.71 was classified with the A. sarcoides strains and CBS 192.62 with the A. cylichnium strains for this analysis.

Fig. 1.

Phylogeny of ATCC and CBS Ascocoryne strains and NRRL 50072. Bayesian analysis of Ascocoryne strains and NRRL 50072 using ITS and CTP sequences. Bayesian posterior probabilities are displayed at branch nodes, and species clustering is noted.

The phylogenetic comparisons also illustrate the genetic similarity between NRRL 50072 and the Ascocoryne species present in culture collections. Based on ITS sequence alone, NRRL 50072 could not be resolved from a six-tip polytomy (data not shown). Inclusion of the CTP sequence resolved this node and showed that NRRL 50072 is more distant from the other six A. sarcoides than they are from each other, possibly reflecting the geographical difference in isolation locations (Fig. 1). The close grouping of NRRL 50072 with several A. sarcoides strains in public culture collections further establishes that NRRL 50072 is an A. sarcoides rather than a G. roseum strain (Bunyard et al., 2008; Strobel et al., 2008).

VOC production by Ascocoryne strains

VOC production was monitored from the culture headspace of each Ascocoryne strain grown on two types of solid media. OA and CA were selected to facilitate the comparison of production profiles between each strain and those previously reported for NRRL 50072 (Strobel et al., 2008). Volatiles detected after 18 days of growth in sealed vials were expected to represent the compounds produced over the experimental time-course.

Compounds spanning seven chemical classes were produced by the ten Ascocoryne cultures and included over 100 distinct compounds. Individual isolates alone produced as many as 63 compounds (Tables 2 and 3). The VOCs include classes of alkanes, alkenes, alcohols, esters, ketones, acids, benzene derivatives and terpenes.

Table 2.

Volatile products detected from NRRL 50072 and the ten Ascocoryne strains grown on OA in vials

Peak heights and areas relative to the internal standard 2-heptanone were used to estimate levels of production for each compound (#–#####; low–high); a number following the hash(es) indicates the number of replicates in which the compound was detected at that level. Two values in one cell indicate that the compound was detected with significantly different peak areas between replicates for that culture.

| Product | Retention time (min) | CA* | Previous report† | NRRL50072 | A. sarcoides | A. solitaria | A. cylichnium | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 170.56 | 171.56 | 246.80 | 309.71 | 44013 | 64109 | 738.84 | 192.62 | 251.80 | 44015 | |||||

| Alkanes/alkenes | ||||||||||||||

| 2-Pentene‡ | 1.70 | C | #### 3 | ##### 3 | ##### 3 | ## 1; # 2 | ## 1 | ### 2 | ### 1 | ### 3 | ## 2; # 1 | #### 2 | ||

| Heptane‡ | 2.08 | ### 3 | # 2 | ## 2 | # 1 | ## 2 | # 2 | ## 1 | ## 3 | ### 2 | # 3 | |||

| Octane‡ | 2.91 | b | ## 2 | ## 3 | ## 2 | # 2 | ## 2 | ## 2 | ## 1 | ## 3 | ### 2 | ## 1; # 2 | ## 1 | |

| 1-Methyl cyclohexene | 15.49 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 1 | # 3 | ||||||||

| 3-Octene | 3.90 | # 2 | # 2 | # 1 | # 2 | |||||||||

| 3,5-Octadiene | 15.20 | b | # 3 | |||||||||||

| 3-Nonene | 15.68 | C | ## 1; # 2 | |||||||||||

| 4-Nonene | 15.83 | ## 1; # 2 | ||||||||||||

| Cyclodecane | 16.57 | C | ## 2 | |||||||||||

| Cyclodecene | 20.67 | b | # 3 | # 2 | ||||||||||

| Alcohols | ||||||||||||||

| 1-Propanol | 7.51 | # 3 | ||||||||||||

| 2-Methyl-1-propanol‡ | 8.85 | C | a, b | ## 3 | ## 3 | ## 3 | ## 3 | ### 2; ## 1 | ## 3 | ### 1; ## 2 | ## 3 | ## 3 | ## 3 | ### 2; ## 1 |

| 1-Butanol | 9.90 | # 3 | ||||||||||||

| 3-Methyl-1-butanol‡ | 11.23 | C | a, b | #### 3 | ##### 3 | #### 3 | ##### 3 | ##### 3 | ##### 3 | ##### 3 | ### 3 | #### 3 | ##### 2; ### 1 | ##### 3 |

| 3-Methyl-1-pentanol | 13.73 | # 3 | ||||||||||||

| 1-Hexanol‡ | 14.23 | b | ## 3 | ## 3 | # 3 | # 3 | ## 3 | # 3 | # 2 | # 3 | ## 2 | # 3 | # 3 | |

| 3-Hexanol‡ | 10.95 | # 1 | # 2 | |||||||||||

| 1-Heptanol‡ | 16.20 | C | b | # 3 | ### 3 | ### 3 | ### 2; # 1 | ### 2; ## 1 | ### 3 | ### 1; ## 2 | ### 3 | #### 3 | ##### 3 | ##### 3 |

| 2-Heptanol | 13.33 | b | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | ||||||||

| 3-Heptanol | 12.26 | C | # 2 | ## 1 | ### 3 | ## 1 | ||||||||

| 1-Octanol‡ | 18.03 | # 1 | # 1 | # 2 | # 2 | # 3 | # 3 | |||||||

| 3-Octanol | 14.90 | # 2 | # 2 | # 1 | ||||||||||

| 3-Nonen-2-ol | 19.00 | # 3 | ||||||||||||

| Phenylmethanol | 23.61 | b | # 3 | # 2 | ||||||||||

| 2-Phenylethanol‡ | 24.14 | C | a, b | ## 3 | ## 3 | # 3 | ## 3 | ## 3 | ## 3 | ## 3 | # 3 | # 3 | ## 3 | ## 3 |

| Esters | ||||||||||||||

| Methyl acetate‡ | 3.49 | C | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | ## 2; # 1 | ## 3 | ## 3 | ||||||

| Ethyl acetate‡ | 4.45 | C | ##### 3 | ##### 3 | #### 3 | ##### 2; ### 1 | ##### 3 | ##### 3 | ##### 3 | ## 3 | ## 2 | ## 3 | ## 2 | |

| Propyl acetate | 6.14 | ## 3 | # 1 | # 1 | # 1 | # 1 | # 1 | # 1 | # 1 | # 1 | # 1 | |||

| 2-Butyl acetate | 5.52 | # 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2-Methyl-1-propyl acetate‡ | 6.93 | C | b | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | ## 1; # 2 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 2 | # 3 | # 2 |

| 3-Methyl-1-butyl acetate‡ | 9.35 | b | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | ## 1; # 2 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | |

| Hexyl acetate‡ | 12.59 | b | # 3 | # 2 | # 1 | # 1 | # 2 | ## 1 | ||||||

| Heptyl acetate | 14.63 | C | b | ### 3 | ### 3 | ### 3 | ### 2; # 1 | ### 3 | ## 3 | ## 3 | # 3 | # 3 | ## 1; # 2 | ## 1; # 2 |

| Octyl acetate‡ | 16.60 | C | b | ## 3 | ## 3 | ## 3 | # 3 | # 2 | # 3 | |||||

| Nonyl acetate‡ | 18.43 | # 2 | # 3 | # 3 | # 2 | # 2 | # 3 | |||||||

| Decyl acetate | 20.17 | b | # 3 | |||||||||||

| 2-Phenylethyl acetate‡ | 22.64 | C | a | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | ||||

| Propyl propionate | 7.65 | # 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2-Butyl propionate | 7.76 | C | a | #### 1 | #### 1 | ### 1 | ||||||||

| Methyl butanoate | 6.22 | # 1 | ||||||||||||

| Methyl 3-methyl-1-butanoate | 7.09 | a | # 3 | # 1 | ||||||||||

| Methyl octanonate | 14.96 | b | # 3 | |||||||||||

| Methyl 2-octenoate | 15.38 | # 3 | ||||||||||||

| Ethyl octanonate | 15.79 | # 2 | ||||||||||||

| Ketones | ||||||||||||||

| 2-Methyl-3-pentanone‡ | 6.45 | # 3 | # 2 | # 2 | # 2 | # 3 | ||||||||

| 3-Hexanone‡ | 7.80 | C | b | # 2 | ## 2; # 1 | # 1 | ||||||||

| 4-Methyl-3-hexanone | 8.28 | C | a, b | ## 3 | ## 3 | #### 2; ## 1 | ## 3 | #### 2; # 1 | ||||||

| 2-Octanone‡ | 12.89 | # 3 | # 3 | # 2 | # 3 | # 2 | ## 3 | ## 2; # 1 | ||||||

| 3-Octanone‡ | 12.24 | a, b | # 1 | # 3 | # 3 | # 1 | # 1 | # 3 | # 1 | # 3 | # 2 | # 3 | # 2 | |

| 7-Octen-2-one | 13.86 | b | # 3 | |||||||||||

| 4-Methyl-3-octanone | 12.25 | C | ## 2 | |||||||||||

| 5-Ethyl-4-methyl-3-heptanone | 13.13 | C | ## 3 | ## 2; # 1 | ### 3 | # 3 | ## 2 | |||||||

| 2-Nonanone | 14.98 | # 1 | ## 3 | # 1 | # 1 | # 1 | ||||||||

| Ethers | ||||||||||||||

| 1-Ethenyl-4-methoxy-benzene | 20.43 | # 1 | # 1 | # 1 | # 1 | # 1 | # 1 | # 2 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | |||

| 1-Ethyl-4-methoxy-benzene | 17.80 | ## 2 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | # 3 | |||||||

| 4-Ethyl-1,2-dimethyoxybenzene | 23.50 | # 1 | # 1 | # 2 | # 3 | # 1 | ||||||||

| 1,2-Dimethoxybenzene | 21.02 | C | # 1 | # 3 | # 2 | |||||||||

| Acids | ||||||||||||||

| Acetic acid‡ | 17.01 | C | b | #### 3 | ##### 2 | #### 3 | ##### 1; ## 1 | #### 2; ## 1 | #### 3 | #### 1; # 2 | ## 3 | ##### 2; # 1 | #### 2; ### 1 | ## 1; # 1 |

| 2-Methyl-pentanoic acid | 24.50 | b | # 3 | |||||||||||

| Unknown | 16.95 | # 1 | # 3 | |||||||||||

| Unknown | 16.12 | # 1 | ||||||||||||

| Terpenes§ | ||||||||||||||

| Sesquiterpene | 16–24 | 8 | 34 | 35 | 8 | 14 | 12 | 18 | 23 | 28 | 39 | 23 | ||

| Monoterpene | 6–13 | 6 | ||||||||||||

*A ‘C’ in this column indicates that the compound was also detected in the headspace of Ascocoryne cultures grown on CA (see Table 3).

†Some VOCs were previously reported to be produced by NRRL 5007. Reported by: a, Stinson et al. (2003); b, Strobel et al. (2008).

‡Retention time and mass spectra matched that of pure standard.

§Terpene isomers were not differentiated for the compounds. The retention time given is the range and the number of distinctly eluting terpene compounds detected in all replicates is reported for each organism.

Table 3.

Volatile products detected from NRRL 50072 and the ten Ascocoryne strains grown on CA in vials

Peak heights and areas relative to the internal standard 2-heptanone were used to estimate levels of production for each compound (#–#####; low–high); a number following the hash(es) indicates the number of replicates in which the compound was detected at that level. Two values in one cell indicate that the compound was detected with significantly different peak areas between replicates for that culture.

| Product | Retention time (min) | OA* | Previous report† | NRRL 50072 | A. sarcoides | A. solitaria | A. cylichnium | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 170.56 | 171.56 | 246.80 | 309.71 | 44013 | 64109 | 738.84 | 192.62 | 251.80 | 44015 | |||||

| Alkanes/alkenes | ||||||||||||||

| 2-Pentene‡ | 1.70 | O | ## 3 | ##### 2 | ##### 2; ## 1 | #### 3 | ### 3 | ##### 3 | ##### 3 | ##### 2 | ##### 2; ### 1 | ##### 1; #### 2 | ||

| 3-Nonene | 15.53 | # 3 | ||||||||||||

| Cyclodecane | 16.47 | O | # 3 | |||||||||||

| Alcohols | ||||||||||||||

| 2-Methyl propanol‡ | 8.85 | O | a, b | ## 2 | ## 2 | ## 3 | ## 3 | ## 2; # 1 | ## 3 | ## 2 | # 3 | # 3 | ||

| 3-Methyl butanol‡ | 11.23 | O | a, b | # 3 | ### 2 | ### 2 | ### 1; ## 2 | #### 3 | ##### 2; ## 1 | ### 2; ## 1 | ## 3 | ### 1; # 2 | ## 3 | ## 3 |

| 1-Heptanol‡ | 16.20 | O | b | #### 1 | ## 3 | ## 2 | ||||||||

| 3-Heptanol | 12.26 | O | # 2 | |||||||||||

| 2-Phenylethanol‡ | 24.14 | O | a, b | # 2 | # 1 | |||||||||

| Esters | ||||||||||||||

| Methyl acetate‡ | 3.39 | O | # 1 | ## 1 | ## 3 | # 2 | ||||||||

| Ethyl acetate‡ | 4.45 | O | ### 1 | ### 1 | ##### 3 | ##### 1; ### 1 | ## 1 | |||||||

| 2-Methyl-1-propyl acetate‡ | 6.82 | O | b | # 3 | ||||||||||

| Heptyl acetate‡ | 14.63 | O | b | # 1 | # 3 | ## 1; # 1 | ||||||||

| Octyl acetate‡ | 16.60 | O | b | ## 1 | ||||||||||

| 2-Phenylethyl acetate‡ | 22.64 | O | a | # 1 | ||||||||||

| 2-Butyl propionate | 7.76 | O | a | ## 2 | ## 2 | |||||||||

| Ketones | ||||||||||||||

| 4-Methyl-2-pentanone | 6.65 | b | # 1 | |||||||||||

| 3-Hexanone | 7.80 | O | b | ## 1 | ||||||||||

| 4-Methyl-3-hexanone | 8.28 | O | a, b | ## 1 | ## 3 | |||||||||

| 4-Methyl-3-octanone | 12.25 | O | ## 3 | |||||||||||

| 5-Ethyl-4-methyl-3-heptanone | 13.13 | O | b | ## 3 | ||||||||||

| Acids | ||||||||||||||

| Acetic acid‡ | 17.01 | O | b | ### 1 | ##### 1; ## 2 | ##### 1; ### 1 | ||||||||

| Terpenes§ | ||||||||||||||

| Sesquiterpene | 16–24 | O | a, b | 27 | 25 | 11 | 8 | 12 | 13 | 49 | 40 | 38 | ||

| Monoterpene | 6–13 | O | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

*An ‘O’ in this column indicates that the compound was also detected in the headspace of Ascocoryne cultures grown on OA (see Table 2).

†Some VOCs were previously reported to be produced by NRRL 5007. Reported by: a, Stinson et al. (2003); b, Strobel et al. (2008).

‡Retention time and mass spectra matched that of pure standard.

§Terpene isomers were not differentiated for the compounds. The retention time given is the range, and the number of distinctly eluting terpene compounds detected in all replicates is reported for each organism.

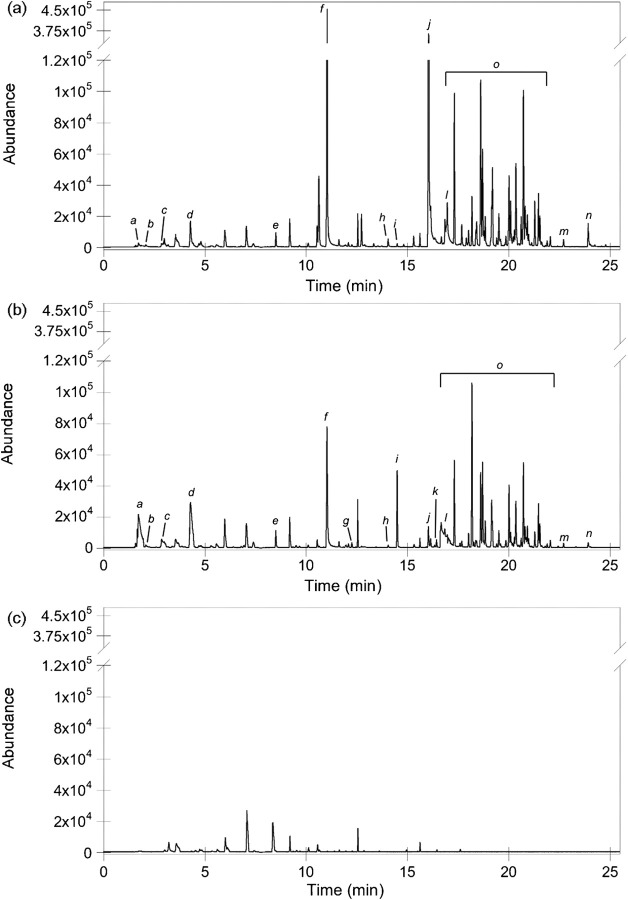

Short- and branched-chain alcohol VOCs were produced broadly by members of the genus Ascocoryne, but the production profiles of medium straight-chain alcohols exhibited species specificity. The alcohol product 3-methyl-1-butanol, the related shorter chain alcohol 2-methyl-1-propanol and 2-phenylethanol were present in all OA-grown cultures at comparable levels (Table 2). However, the longer straight-chain alcohols, 1-heptanol and 1-octanol, were produced preferentially by the three A. cylichnium strains (Table 2). Approximately 35-fold higher levels of 1-heptanol were detected in A. cylichnium cultures versus A. sarcoides, making it one of the most dominant compound peaks in A. cylichnium total ion chromatograms (Fig. 2). The eight carbon straight-chained alcohol, 1-octanol, was only reproducibly detected from A. cylichnium and A. solitaria cultures, while 1-hexanol was detected at equally low levels from all species.

Fig. 2.

Total ion chromatograms from SPME-GC/MS analysis of Ascocoryne isolates grown on OA in vials for 18 days. (a) A. cylichnium CBS 251.80; (b) A. sarcoides CBS 170.56; (c) uninoculated control. Some compounds discussed in the text are denoted as follows: a, 2-pentene; b, heptane; c, octane; d, ethyl acetate; e, 2-methyl-1-propanol; f, 3-methyl-1-butanol; g, hexyl acetate; h, 1-hexanol; i, heptyl acetate; j, 1-heptanol; k, octyl acetate; l, acetic acid; m, 2-phenylethyl acetate; n, 2-phenylethanol; o, sesquiterpenes.

In contrast with the alcohols, the A. sarcoides isolates exhibited preferential production of several ketones and esters when grown on OA (Table 2). Half of the ketones were detected only from A. sarcoides isolates, and of these, the branched ketones, 4-methyl-3-hexanone and 5-ethyl-4-methyl-3-heptanone, were produced by four of the six A. sarcoides isolates (Table 2). Esters exclusively produced by the six A. sarcoides cultures include the methyl, 2-butyl, hexyl, octyl, nonyl and 2-phenylethyl esters of acetic acid, and the propyl and 2-butyl esters of propanoic acid (Fig. 2, Table 2). The octyl, nonyl and 2-phenylethyl acetate esters were produced by at least five of the six A. sarcoides isolates, further demonstrating species-specific production. Hexyl acetate was similarly detected from the A. sarcoides isolates in addition to the A. solitaria strain. Ethyl acetate and heptyl acetate were produced by all cultures, but the levels detected were species-dependent. They were present at much higher levels in all A. sarcoides strains compared with A. cylichnium or A. solitaria (Fig. 2, Table 2).

Although the VOC production profiles of the Ascocoryne strains were similar to one another, CBS 309.71 offered a unique profile of volatiles. In the analysis of VOCs from OA-grown cultures, six short- and medium-chain volatile compounds were found only in the CBS 309.71 culture, and four additional compounds were produced by two or fewer other organisms. These VOCs include alkenes tentatively identified as 3-nonene, 4-nonene, cyclodecane, and 3-hexanone, 4-methyl-3-octanone and 3-hexanol. The analysis of cultures grown on cellulose further demonstrated the unique production capabilities of CBS 309.71, with twice the number of short- and medium-chain volatile products detected from CBS 309.71 than the second highest producing isolate on CA. The additional VOCs include nine compounds that were produced only by CBS 309.71 under the CA conditions. Moreover, CBS 309.71 also showed the fastest growth rate of all Ascocoryne strains when grown in liquid culture (results not shown). The remaining nine isolates had limited production when grown on CA with 2-pentene, 2-methyl-1-propanol, 3-methyl-1-butanol, ethyl acetate, acetic acid and 1-heptanol, constituting the majority of short- and medium-chain products observed.

The Ascocoryne strains demonstrate production of numerous sesquiterpene compounds when grown on a cellulosic substrate. The A. cylichnium strains each produced about 30 sesquiterpenes on OA, but this increased to almost 50 sesquiterpenes when grown on CA. The A. cylichnium strains had the highest number of sesquiterpenes, but two A. sarcoides isolates and the A. solitaria isolate also produced more than 20 sesquiterpenes on at least one growth medium.

Although all tested organisms from the genus Ascocoryne produced a variety of VOCs, there were limited similarities to the VOC profile reported for NRRL 50072. VOCs produced by these strains had 21 short- and medium-chain products in common with the reported NRRL 50072 reported products, but the 10 cultures also made an additional 29 short- and medium-chain VOCs that were not detected from NRRL 50072. Many of these new volatiles were short (C1–C3) acetate esters, medium-chain alcohols (C7–C8) and benzene derivatives.

Despite a breadth of VOC production by the ten cultures, several compounds reported for NRRL 50072 were not produced by any of the Ascocoryne strains. Notably absent were the medium-chain branched alkanes, including compounds such as 5-ethyl-2,2,3-trimethyl-heptane, 3-ethyl-2,7-methyl-octane and 4,4-dimethyl-undecane (Strobel et al., 2008).

NRRL 50072 VOC production

The Patagonian endophytic A. sarcoides isolate NRRL 50072 may be unique from its European relatives in its ability to produce branched alkanes. However, the differences in VOCs noted for members of the genus Ascocoryne and NRRL 50072 led us to re-examine NRRL 50072 VOC production and to explore its production abilities under a wide variety of growth and sampling conditions.

Two previous analyses of NRRL 50072 production report VOCs manually sampled from four different media with either one or two replicates (Stinson et al., 2003; Strobel et al., 2008). The first NRRL 50072 VOC analysis reported volatiles from a single PDA culture at 19 days. In a subsequent study, the headspace of NRRL 50072 was monitored from cultures grown on three types of media (OA, CA and host plant medium) (Strobel et al., 2008). In this analysis, it was noted that nine compounds did not match the authentic standard compound retention time, and 13 of the highly branched alkane compounds were compared to a diesel fuel as a standard, which is a highly complex mixture of unknown absolute composition. Identification of alkanes is notoriously difficult based upon comparison with standard libraries because the EI fragments are similar for many alkanes (Schulz & Dickschat, 2007). Further difficulty in alkane identification is evident in Tables 1–3 in the paper by Strobel et al. (2008). The identification of some of the highly branched alkanes was considered possible and some compounds were indicated as possible isomers (Strobel et al., 2008). 5-Ethyl-2,3,3-trimethyl heptane and 3,3,5-trimethyl decane are both included twice within the same sample table, but correspond to peaks that elute 0.5–1 min apart (Strobel et al., 2008). This raises concerns about the accuracy of that analysis.

We re-analysed NRRL 50072 headspace volatiles using conditions developed for the Ascocoryne strain survey that were similar to those used in the previous report (Strobel et al., 2008). Forty-eight compounds were detected from OA and CA culture headspace of the NRRL 50072 replicates and approximately two-thirds were consistent with the previously reported products for this strain (Tables 2 and 3) (Stinson et al., 2003; Strobel et al., 2008). Over 75 % of VOCs produced by NRRL 50072 under these conditions were also products of the other Ascocoryne strains. These volatiles were detected at levels similar to those from the six A. sarcoides isolates, further demonstrating a correlation between phylogeny and production profiles within the genus. A subset of volatiles not previously known as products of NRRL 50072 or members of the genus Ascocoryne was also detected. Twelve VOCs detected from NRRL 50072 replicates were not products of other Ascocoryne strains, and 16 of the compounds were not previously reported for NRRL 50072 (Stinson et al., 2003; Strobel et al., 2008). These products include 1-propanol, 1-butanol, 3-methyl-1-pentanol, methyl 2-octenoate and ethyl octanoate.

Although a wide variety of VOCs were observed from NRRL 50072 under these conditions, we did not observe production of the medium-chain-length branched alkanes that were reported previously for this organism. Some chromatographic peaks for medium- or long-chain alkanes were detected in the NRRL 50072 analysis, but in each case there was an equivalent compound in the uninoculated media control. It is noteworthy that the uninoculated media headspaces contained small amounts of several highly branched alkanes (C4–C14) and other compounds such as hexanal, 2-octenal, furan derivatives, 1-octen-3-ol, 3-octen-2-one, butyrolactone and phenol derivatives. The identity of these compounds was specific to the media type. The chromatographic peaks resulting from the uninoculated media increased in peak intensity and area in the autoclaved uninoculated media compared with non-autoclaved uninoculated media (data not shown).

We next examined an extensive range of culture conditions and sampling methods in an effort to probe the remaining differences in NRRL 50072 VOC products, specifically the branched chain alkanes. Oatmeal and potato dextrose media from various suppliers (EMD, Difco, Acumedia) or freshly prepared media, minimal media base with a series of different salt and cofactor supplements and varied carbon (sodium acetate, cellulose, cellobiose, glucose) and nitrogen (NH4Cl, NaNO3, NH4NO3) sources were tested. The source of water in culture medium preparations (distilled, tap, well) was also investigated due to potential differences in metal concentrations that may impact secondary metabolite biosynthesis (Paranagama et al., 2007). Culture growth delay prior to headspace sampling varied between 2 and 35 days for different sample types to probe the changes in production with age. Samples tested included microaerophilic sealed bottles and vials and fully aerobic cultures grown in Petri dishes or shaking flasks.

VOC production by NRRL 50072 varied over this diverse set of culture conditions. A subset of the headspace analysis results demonstrates the range of production observed (Table 4). The PDB 100 ml NRRL 50072 culture sampled at day 10 contained a collection of volatiles similar to those detected from NRRL 50072 grown on OA in vials or bottles. The NRRL 50072 PDB culture product list was dominated by an extensive series of alcohols and esters and 24 sesquiterpenes. Notably, very few alkane or alkene short-chain products were detected from this liquid culture. Cultures grown on PDA and sampled at day 35 displayed a similar depletion in alkane and alkene products (Table 4). Fewer products were produced by NRRL 50072 when grown on the defined media resulting in limited similarity to the VOCs produced by NRRL 50072 grown on OA or PDA (Table 4). Branched-chain amino acid alcohols 2-methyl-1-propanol, 3-methyl-1-butanol, 2-phenylethanol and 1-hexanol were the most common alcohol products across all conditions. The predominant esters made by NRRL 50072 on minimal media were straight-chain C6–C9 esters of acetic acid such as octyl and nonyl acetate. A small number of other compounds including alkenes and ketones were also detected from cultures grown on defined media.

Table 4.

Volatile products detected from NRRL 50072 grown under various conditions

×, Compound was detected. For experiments with multiple trials, the number of replicates for which the compound was detected is given. The total number of replicates for each experiment is: OA vial day 18, 3 replicates; PDB flask day 10, 1 replicate; PDA vial day 35, 1 replicate; CB flask day 15, 1 replicate; acetate vial day 5, 3 replicates; no ammonium vial day 10, 3 replicates.

| Product | Retentiontime (min) | Previous report* | OA vial day 18 | PDB flaskday 10 | PDA vialday 35 | CB flaskday 15 | Acetate vialday 5 | No ammonium vial day 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkanes/alkenes | ||||||||

| Pentane | 1.54 | × | ||||||

| 2-Pentene† | 1.70 | × 3 | × 3 | × 3 | ||||

| Heptane† | 2.08 | × 3 | × | × 3 | ||||

| 1-Heptene | 2.40 | × | × 1 | × 3 | ||||

| Octane† | 2.91 | b | × 2 | × | × | |||

| 1-Methyl cyclohexene | 15.49 | × 3 | ||||||

| 3,5-Octadiene | 15.20 | b | × 3 | |||||

| Cyclodecene | 20.67 | b | × 3 | × 1 | × 1 | |||

| Alcohols | ||||||||

| 1-Propanol | 7.51 | × 3 | × | × | ||||

| 2-Methyl-1-propanol† | 8.85 | a, b | × 3 | × | × | × | × 3 | |

| 1-Butanol | 9.86 | × 3 | × | |||||

| 3-Methyl-1-butanol† | 11.23 | a, b | × 3 | × | × | × 1 | × 3 | |

| 3-Methyl-3-buten-1-ol | 12.22 | × | ||||||

| 1-Pentanol | 12.13 | × | × | × | × 3 | |||

| 4-Penten-1-ol | 13.28 | × | ||||||

| 4-Methyl-1-pentanol | 13.48 | × | ||||||

| 3-Methyl-1-pentanol | 13.73 | × 3 | × | |||||

| 2,3-Dimethyl-3-pentanol | 8.78 | × | ||||||

| 1-Hexanol† | 14.23 | b | × 3 | × | × | × | × 3 | × 3 |

| 3-Methyl-1-hexanol | 15.39 | × | ||||||

| 1-Heptanol† | 16.20 | b | × 3 | × 3 | ||||

| 3-Heptanol | 12.26 | × 2 | ||||||

| 4-Heptanol | 14.70 | × | ||||||

| 1-Octanol† | 18.03 | × | ||||||

| 1-Octen-3-ol | 16.09 | a, b | × 3 | |||||

| 3-Nonen-2-ol | 19.00 | × 3 | × 1 | × 3 | ||||

| Phenylmethanol | 23.61 | b | × 3 | |||||

| 2-phenylethanol† | 24.14 | a, b | × 3 | × | × | × 1 | ||

| Esters | ||||||||

| Methyl acetate† | 3.49 | × 3 | ||||||

| Ethyl acetate† | 4.45 | × 3 | × | × | × 1 | × 3 | ||

| Propyl acetate | 6.14 | × 3 | × | |||||

| 2-Methyl-1-propyl acetate† | 6.93 | b | × 3 | × | × | |||

| Butyl acetate | 8.24 | × | × | |||||

| 3-Methyl-1-butyl acetate† | 9.35 | b | × 3 | × | ||||

| Pentyl acetate | 10.44 | × | ||||||

| Hexyl acetate† | 12.59 | b | × 3 | × | × 3 | |||

| 4-Methyl-1-hexyl acetate | 13.64 | × | ||||||

| Heptyl acetate | 14.63 | b | × 3 | × | × 3 | |||

| Octyl acetate† | 16.60 | b | × 3 | × | × 3 | × 3 | ||

| Nonyl acetate† | 18.43 | × 3 | × | × 3 | × 3 | |||

| Decyl acetate | 20.17 | b | × 3 | × 2 | ||||

| 2-Phenylethyl acetate† | 22.64 | a | × 3 | × | × | × 1 | ||

| 2-Butyl propionate | 7.76 | a | × 3 | |||||

| Methyl 2-methyl-1-butanoate | 6.85 | × | ||||||

| Methyl 3-methyl-1-butanoate | 7.09 | a | × 3 | × | × | |||

| Methyl 2,6-dimethyl heptanoate | 15.16 | × | ||||||

| Methyl octanonate | 14.96 | b | × 3 | |||||

| Methyl 2-octenoate | 15.38 | × 3 | × | |||||

| Methyl 2-methyl octanoate | 14.90 | × | ||||||

| Ethyl propionate | 5.78 | × | ||||||

| Ethyl 3-methyl-1-butanoate | 8.11 | × | ||||||

| Ethyl octanoate | 15.79 | × 2 | × | |||||

| 3-Methyl-1-butyl butanoate | 12.38 | × | ||||||

| Ketones | ||||||||

| 3-Pentanone | 6.19 | × | ||||||

| 2-Methyl-3-pentanone† | 6.45 | × | ||||||

| 4-Methyl-3-hexanone | 8.28 | a, b | × 3 | |||||

| 6-Methyl-2-heptanone | 11.89 | × 3 | ||||||

| 3-Octanone† | 12.24 | a, b | × 1 | × | × 3 | |||

| 7-Octen-2-one | 13.86 | b | × 3 | |||||

| 5-Ethyl-4-methyl-3-heptanone | 13.13 | × 3 | × | |||||

| 2-Nonanone | 14.98 | × | ||||||

| 5-Ethyl-2-heptanone | 14.06 | × 3 | ||||||

| 2-Undecanone | 18.82 | × | ||||||

| Acids | ||||||||

| Acetic acid† | 17.01 | b | × 3 | × | × 3 | × 3 | ||

| Propanoic acid | 18.54 | × | ||||||

| 3-Methyl butanoic acid | 20.67 | × | ||||||

| 2,3-Dimethyl butanoic acid | 21.87 | × | ||||||

| 2-Methyl pentanoic acid | 24.50 | b | × 3 | |||||

| Hexanoic acid | 20.58 | b | × | |||||

| Other VOCs | ||||||||

| 2-Isopropylfuran | 7.29 | × | × 3 | × 3 | ||||

| 2-Pentyl furan | 11.85 | × 3 | × 3 | |||||

| Octahydro-1H-idenene | 18.95 | b | × | |||||

| 4-Ethyl-1,2-dimethyoxybenzene | 23.50 | × 1 | ||||||

| Terpenes‡ | ||||||||

| Sesquiterpenes | 16–24 | a, b | 8 | 24 | 2 |

*Some VOCs were previously reported to be produced by NRRL 5007. Reported by: a, Stinson et al. (2003); b, Strobel et al. (2008).

†Retention time and mass spectra matched that of pure standard.

‡Terpene isomers were not differentiated for the compounds. The retention time given is the range, and the number of distinctly eluting terpene compounds detected in all replicates is reported for each organism.

Ninety-seven volatiles were detected from these six representative samples and they expand the collection of short- and medium-chain VOCs produced by NRRL 50072 by 47 compounds. The majority of compounds were either identical or similar to VOCs produced by other ascocoryne strains. We were able to detect production of the straight-chain alkanes heptane and octane, but no growth or sampling condition variation tested recovered production of the highly branched alkane VOCs.

DISCUSSION

Ten Ascocoryne cultures were obtained from the ATCC and CBS cultures collections to compare their VOC production capabilities with NRRL 50072 A. sarcoides. A phylogenetic analysis confirmed the genus classifications of the ten cultures and established their relatedness to NRRL 50072. SPME-GC/MS analysis of Ascocoryne volatiles revealed production of over 100 VOCs, a subset of which was species-specific. To understand differences between the observed Ascocoryne VOCs and those reported for NRRL 50072, we examined NRRL 50072 production under numerous growth and sampling conditions. The extensive VOC analyses expanded the NRRL 50072 production list to include 47 additional compounds, but we did not observe production of the highly branched alkanes.

VOC production by Ascocoryne strains available in public culture collections

Investigations into VOCs produced by strains of common environmental cultures have provided information on production trends within different fungal genera on many substrates. Multiple isolates from the genera Aspergillus, Fusarium, Penicillium and Trichoderma have been studied for VOC production from a variety of laboratory media or substrates designed to mimic building materials (Fiedler et al., 2001; Larsen & Frisvad, 1995; Minerdi et al., 2009; Schuchardt & Kruse, 2009; Van Lancker et al., 2008; Wheatley et al., 1997; Wihlborg et al., 2008). Frequently reported microbial VOCs from these and other organisms include short chain organics such as branched alcohols and esters in addition to terpene compounds (Korpi et al., 2009).

The ten strains selected for this study included a collection of both very closely related organisms, such as most of the European A. sarcoides, and a more diverse sampling of the genus with three represented species groups. These strains exhibited a broad range of VOC production. The products encompass numerous chemical classes identified from other micro-organisms, but include compounds rarely reported together from a single isolate. Some Ascocoryne volatiles include microbial VOCs derived from the primary metabolism of amino acids, the breakdown of cellular components, such as fatty acids, and conserved secondary metabolism pathways (Korpi et al., 2009; Schulz & Dickschat, 2007).

Branched-chain amino acid metabolism may be responsible for several of the Ascocoryne volatile alcohols and esters, but medium straight-chain products with undefined biosynthetic pathways were also detected and displayed interesting production trends. Alpha-ketoacid intermediates in amino acid metabolism, such as 2-ketoisovalerate, can be converted to corresponding alcohols (2-methyl-1-propanol) and subsequently to esters (2-methylpropyl acetate) (Atsumi et al., 2009; Korpi et al., 2009). Similarly, 2-phenylethanol and the ester 2-phenylethyl acetate originate from phenylalanine (Korpi et al., 2009). Given their conserved biosynthetic origin, there are examples of these VOC products in other fungal genera and they were uniformly produced by all Ascocoryne strains. The alcohols 1-octanol and 1-hexanol are also both commonly reported microbial VOCs, but they were specific to A. cylichnium strains under the tested conditions (Korpi et al., 2009).

Particularly notable is the novel odd-numbered alcohol 1-heptanol, which was detected at high levels in all A. cylichnium strains (Table 2). A survey of volatile metabolites from 14 common indoor fungi reported production of 1-heptanol by a single culture at very low levels (Aureobasidium pullullans CBS 96.1303) and little evidence for its production by other fungi is available (Schuchardt & Kruse, 2009; Wihlborg et al., 2008). However, some organisms are known to produce the closely related secondary alcohol 2-heptanol and the branched 6-methyl-1-heptanol [Penicillium coprophileum (Berk & M.A. Curtis) Seiferi & Samson IBT 5539 and Alternaria alternata Keissler, respectively] (Fiedler et al., 2001; Larsen & Frisvad, 1995; Van Lancker et al., 2008). NRRL 50072 was reported to produce 2-heptanol on OA but 1-heptanol on CA. Four Ascocoryne strains produced 2-heptanol on OA, but interestingly all ten strains demonstrated production of the rarely observed alcohol 1-heptanol (Table 2). Although 1-heptanol was produced at high levels by A. cylichnium strains on OA, only A. sarcoides strains produced this alcohol on CA, similar to NRRL 50072 (Table 3) (Strobel et al., 2008).

The straight-chain acetate esters, hexyl, heptyl, octyl and nonyl, were also produced by many Ascocoryne strains. A survey of volatiles from 47 Penicillium species reported that only one of the 47 strains tested produced pentyl, hexyl, heptyl and octyl acetate [Penicillium digitatum (Pers.: Fr.) Sacc IBT 10188] (Larsen & Frisvad, 1995). Hexyl acetate was also produced by Rhizopus stolonifer and two penicillium strains, but these esters are infrequently observed (Fiedler et al., 2001; Wihlborg et al., 2008). The C6–C9 straight-chain acetate esters were each found in the headspace of at least half of the sampled Ascocoryne strains, mostly A. sarcoides (Table 2). These esters were also reported as NRRL 50072 products, suggesting that this is a species-wide ability and is not limited to a particular strain or isolation location or host. The straight and branched medium-chained alcohols, esters and ketones produced by members of the genus Ascocoryne, such as 3-hexanol, 1-heptanol, heptyl acetate, nonyl acetate, 2-methyl-3-pentanone and 4-methyl-3-hexanone, or their derivatives are similar to biofuel targets (Atsumi et al., 2008; Peralta-Yahya & Keasling, 2010; Rude & Schirmer, 2009; Zhang et al., 2008).

In addition to the short- and medium-chain volatiles, a diverse collection of sesquiterpenes was produced by many Ascocoryne strains. Sesquiterpenes include common microbial VOCs synthesized by terpene cyclases that guide the cyclization of the 15-carbon products (Christianson, 2008). Some Ascocoryne strains produced numerous sesquiterpenes (CBS 192.62 produced 49 different sesquiterpene compounds on CA), which may be indicative of multiple or promiscuous terpene cyclases that lead to a diverse set of products (Tables 2 and 3) (Tholl et al., 2005). The cyclic and branched nature of sesquiterpene hydrocarbons make them potential sources of diesel or jet fuel alternatives (Rude & Schirmer, 2009). A diversity of C15 hydrocarbons can be formed by some Ascocoryne species when grown on a cellulose substrate.

The most distinct VOC profile was from the most rapidly growing strain, A. sarcoides CBS 309.71, particularly when grown on the defined CA medium. CBS 309.71 demonstrated production of compounds not detected from the other isolates, including NRRL 50072. On OA, a series of unsaturated hydrocarbons, 3-nonene, 4-nonene and cyclodecane, were only found in CBS 309.71 headspace (Table 2). On CA, this strain had the most extensive medium-chain product list among the isolates and it demonstrated production of more compounds than we detected from NRRL 50072 under this growth condition (Table 3). Except for sesquiterpenes, the other Ascocoryne strains showed only limited VOC production when grown on CA. Production was typically limited to common microbial VOCs such as 3-methyl-1-butanol and ethyl acetate. The products detected from CBS 309.71 grown on CA represent a subset of those produced by all strains grown on OA and CA, and suggest that CBS 309.71 has the ability to convert a cellulose substrate to a range of interesting VOCs.

Compounds were detected in this Ascocoryne survey that were not previously reported for NRRL 50072 A. sarcoides, and numerous alkanes were reported to be produced by NRRL 50072 that were not produced by any related strain (Stinson et al., 2003; Strobel et al., 2008). However, the ten Ascocoryne strains demonstrated production of both common VOCs and compounds that are seen in isolation from other organisms, but that are rarely seen from a single fungal isolate or genus and with unknown biosynthetic origins. These data support the conclusion that organisms throughout the genus Ascocoryne are producers of a variety of VOCs.

Re-examination of NRRL 50072 VOC production

Many of the compounds reported to be produced by NRRL 50072 were not detected in this study, including approximately 40 medium- and long-chain branched alkane compounds. These were previously unidentified as fungal products, and their potential biosynthetic routes were uncertain (Korpi et al., 2009; Ladygina et al., 2006; Strobel et al., 2008). The production of a series of straight and branched medium- and long-chain alkanes was unexpected in the previous studies given that these products were not observed when NRRL 50072 was first isolated and analysed (Stinson et al., 2003; Strobel et al., 2008). In the first report of VOC production, 1,3,5,7-cyclooctatraene, [8]annulene, was identified as the major NRRL 50072 product and its disappearance in the second analysis was attributed to culture passages or storage, but differences in culturing and sampling conditions can also influence VOC production (Fiedler et al., 2001; Stinson et al., 2003; Strobel et al., 2008; Van Lancker et al., 2008). None of the related Ascocoryne organisms produced either [8]annulene or highly branched alkanes. Extensive efforts to reproduce conditions used with NRRL 50072 in the earlier reports did not yield these products.

Compounds either identical or similar to the branched-chain alkanes reported for NRRL 50072 were present in many culture vials, but we excluded these from VOC production lists due to their presence in corresponding uninoculated media headspace controls. The observation of such compounds in the controls suggests a plausible explanation for the discrepancy between this and the previous study with regard to branched alkane production by NRRL 50072. Consistent with these findings, we understand that the authors of the previous NRRL 50072 study (Strobel et al., 2008) will submit corrections to their results that remove compounds, including the branched alkanes, from the production list (G. A. Strobel, personal communication; see the Corrigendum in this issue, pp. 3830–3833).

Although several compounds attributed to A. sarcoides NRRL 50072 could not be confirmed and appear to be artefacts of the original analyses, the data support the conclusion that organisms throughout the genus Ascocoryne are producers of a wide variety of VOCs. We were able to confirm the production of many compounds and expanded the list of volatile products for this fungal genus. NRRL 50072 demonstrated enhanced alkene, ester and alcohol production over most of the other Ascocoryne isolates. Its products included short- and medium-chain branched compounds such as 3,5-octadiene, 1-heptene, 4-methyl-1-pentanol, 3-methyl-1-hexanol, 6-methyl-2-heptanone and methyl 2,6-dimethyl heptanoate. The genus Ascocoryne, represented by NRRL 50072 and ten isolates available in public culture collections, demonstrated production of over 100 distinct VOCs. Numerous Ascocoryne VOC products were detected from cellulose-grown cultures and several have chemical properties consistent with their potential use as biofuels.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gary A. Strobel of the Department of Plant Sciences at Montana State University (Bozeman, MT) for kindly providing NRRL 50072 for the analysis and Lori-Ann Boulanger for technical assistance and helpful discussions. This work was funded by a Department of Defense NSSEFF Grant, 1N00244-09-1-0070. M. A. G. was supported by a pre-doctoral fellowship from the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

The GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession numbers for the sequences reported in this paper are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Two supplementary tables and a supplementary figure are available with the online version of this paper.

Edited by: M. Tien

References

- Atsumi S., Hanai T., Liao J. C. Non-fermentative pathways for synthesis of branched-chain higher alcohols as biofuels. Nature. 2008;451:86–89. doi: 10.1038/nature06450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atsumi S., Li Z., Liao J. C. Acetolactate synthase from Bacillus subtilis serves as a 2-ketoisovalerate decarboxylase for isobutanol biosynthesis in Escherichia coli . Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:6306–6311. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01160-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunyard B. A., Wang Z., Malloch D., Clayden S., Voitk A. New North American Records for Ascocoryne turficola (Ascomycota: Helotiales. FUNGI Magazine. 2008;1:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Christianson D. W. Unearthing the roots of the terpenome. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor M. R., Cann A. F., Liao J. C. 3-Methyl-1-butanol production in Escherichia coli : random mutagenesis and two-phase fermentation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;86:1155–1164. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2401-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. muscle: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler K., Schutz E., Geh S. Detection of microbial volatile organic compounds (MVOCs) produced by moulds on various materials. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2001;204:111–121. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortman J. L., Chhabra S., Mukhopadhyay A., Chou H., Lee T. S., Steen E., Keasling J. D. Biofuel alternatives to ethanol: pumping the microbial well. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J., Nelson E., Tilman D., Polasky S., Tiffany D. Environmental, economic, and energetic costs and benefits of biodiesel and ethanol biofuels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11206–11210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604600103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpi A., Jarnberg J., Pasanen A. L. Microbial volatile organic compounds. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2009;39:139–193. doi: 10.1080/10408440802291497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladygina N., Dedyukhina E. G., Vainshtein M. B. A review on microbial synthesis of hydrocarbons. Process Biochem. 2006;41:1001–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen T. O., Frisvad J. C. Characterization of volatile metabolites from 47 Penicillium taxa. Mycol Res. 1995;99:1153–1166. [Google Scholar]

- McAfee B. J., Taylor A. A review of the volatile metabolites of fungi found on wood substrates. Nat Toxins. 1999;7:283–303. doi: 10.1002/1522-7189(199911/12)7:6<283::aid-nt70>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minerdi D., Bossi S., Gullino M. L., Garibaldi A. Volatile organic compounds: a potential direct long-distance mechanism for antagonistic action of Fusarium oxysporum strain MSA 35. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:844–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M. M., Hallaksela A. M. Variation in combined fatty acid and sterol profiles of Ascocoryne, Nectria, and Neobulgaria-strains isolated from Norway spruce. Eur J Forest Pathol. 1994;24:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Müller M. M., Hallaksela A. M. Fungal diversity in Norway spruce: a case study. Mycol Res. 2000;104:1139–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Müller M. M., Kantola R., Kitunen V. Combining sterol and fatty-acid profiles for the characterization of fungi. Mycol Res. 1994;98:593–603. [Google Scholar]

- Paranagama P. A., Wijeratne E. M., Gunatilaka A. A. Uncovering biosynthetic potential of plant-associated fungi: effect of culture conditions on metabolite production by Paraphaeosphaeria quadriseptata and Chaetomium chiversii . J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1939–1945. doi: 10.1021/np070504b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis T., Ilieva M., Bencheva S., Stancheva J. Researches on wood-destroying fungi division Ascomycota , classis Ascomycetes . Matica Srpska Proc Nat Sci. 2005;109:143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Peralta-Yahya P. P., Keasling J. D. Advanced biofuel production in microbes. Biotechnol J. 2010;5:147–162. doi: 10.1002/biot.200900220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton F., Strobel G. Serinol as an activator of toxin production in attenuated cultures of Helminthosporium sacchari . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:4007–4011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.4007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. FigTree: Tree Figure Drawing Tool, version 1.1.2. Institute of Evolutionary Biology; University of Edinburgh, UK: 2008. Available at: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ [Google Scholar]

- Rehner S. A., Samuels G. J. Taxonomy and phylogeny of Gliocladium analyzed from nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA-sequences. Mycol Res. 1994;98:625–634. [Google Scholar]

- Roll-Hansen F., Roll-Hansen H. Ascocoryne sarcoides and Ascocoryne cylichnium . Descriptions and comparison. Norw J Bot. 1979;26:193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Roll-Hansen F., Roll-Hansen H. Microorganisms which invade Picea abies in seasonal stem wounds II Ascomycetes fungi imperfecti, and bacteria. General discussion Hymenomycetes included. Eur J Forest Pathol. 1980;10:396–410. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P. mrbayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rude M. A., Schirmer A. New microbial fuels: a biotech perspective. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuchardt S., Kruse H. Quantitative volatile metabolite profiling of common indoor fungi: relevancy for indoor air analysis. J Basic Microbiol. 2009;49:350–362. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200800152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz S., Dickschat J. S. Bacterial volatiles: the smell of small organisms. Nat Prod Rep. 2007;24:814–842. doi: 10.1039/b507392h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setkova L., Risticevic S., Pawliszyn J. Rapid headspace solid-phase microextraction-gas chromatographic-time-of-flight mass spectrometric method for qualitative profiling of ice wine volatile fraction. I. Method development and optimization. J Chromatogr A. 20071147:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. A., Dunn C. W. Phyutility: a phyloinformatics tool for trees, alignments and molecular data. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:715–716. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson M., Ezra D., Hess W. M., Sears J., Strobel G. An endophytic Gliocladium sp. of Eucryphia cordifolia producing selective volatile antimicrobial compounds. Plant Sci. 2003;165:913–922. [Google Scholar]

- Strobel G. Muscodor albus and its biological promise. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;33:514–522. doi: 10.1007/s10295-006-0090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel G. A., Dirkse E., Sears J., Markworth C. Volatile antimicrobials from Muscodor albus , a novel endophytic fungus. Microbiology. 2001;147:2943–2950. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-11-2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel G. A., Knighton B., Kluck K., Ren Y., Livinghouse T., Griffin M., Spakowicz D., Sears J. The production of myco-diesel hydrocarbons and their derivatives by the endophytic fungus Gliocladium roseum (NRRL 50072. Microbiology. 2008;154:3319–3328. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholl D., Chen F., Petri J., Gershenzon J., Pichersky E. Two sesquiterpene synthases are responsible for the complex mixture of sesquiterpenes emitted from Arabidopsis flowers. Plant J. 2005;42:757–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lancker F., Adams A., Delmulle B., De Saeger S., Moretti A., Van Peteghem C., De Kimpe N. Use of headspace SPME-GC-MS for the analysis of the volatiles produced by indoor molds grown on different substrates. J Environ Monit. 2008;10:1127–1133. doi: 10.1039/b808608g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Binder M., Schoch C. L., Johnston P. R., Spatafora J. W., Hibbett D. S. Evolution of helotialean fungi ( Leotiomycetes , Pezizomycotina ): a nuclear rDNA phylogeny. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;41:295–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A. M., Procter J. B., Martin D. M., Clamp M., Barton G. J. Jalview Version 2 – a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley R., Hackett Ch., Bruce A., Kundzewicz A. Effect of substrate composition on production of volatile organic compounds from Trichoderma spp. inhibitory to wood decay fungi. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 1997;39:199–205. [Google Scholar]

- White T. J., Burns T., Lee S., Taylor J. Amplification and sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR protocols: A guide to methods and applications. In: Innis M. A., Gelfand D. H., Sninsky J. J., White T. J., editors. San Diego: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 315–322. Edited by. [Google Scholar]

- Wihlborg R., Pippitt D., Marsili R. Headspace sorptive extraction and GC-TOF/MS for the identification of volatile fungal metabolites. J Microbiol Methods. 2008;75:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Sawaya M. R., Eisenberg D. S., Liao J. C. Expanding metabolism for biosynthesis of nonnatural alcohols. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20653–20658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807157106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]