Abstract

Background

We examined frailty as a predictor of recovery in older adults hospitalized with influenza and acute respiratory illness.

Methods

A total of 5011 patients aged ≥65 years were admitted to Canadian Serious Outcomes Surveillance Network hospitals during the 2011/2012, 2012/2013, and 2013/2014 influenza seasons. Frailty was measured using a previously validated frailty index (FI). Poor recovery was defined as death by 30 days postdischarge or an increase of more than 0.06 (≥2 persistent new health deficits) on the FI. Multivariable logistic regression controlled for age, sex, season, influenza diagnosis, and influenza vaccination status.

Results

Mean age was 79.4 (standard deviation = 8.4) years; 53.1% were women. At baseline, 15.0% (n = 750) were nonfrail, 39.3% (n = 1971) were prefrail, 39.8% (n = 1995) were frail, and 5.9% (n = 295) were most frail. Poor recovery was experienced by 21.4%, 52.0% of whom had died. Frailty was associated with lower odds of recovery in all 3 seasons: 2011/2012 (odds ratio [OR] = 0.70; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.59–0.84), 2012/2013 (OR = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.66–0.79), and 2013/2014 (OR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.69–0.82); results varied by season, influenza status, vaccination status, and age.

Conclusions

Increasing frailty is associated with lower odds of recovery, and persistent worsening frailty is an important adverse outcome of acute illness.

Keywords: elderly, frailty, hospitalization, influenza, recovery

Serum quantification of hepatitis B core–related antigen and anti–hepatitis B core antibodies could be useful in predicting hepatitis B e antigen seroclearance in patients with human immunodeficiency virus–hepatitis B virus coinfection undergoing long-term tenofovir-containing antiretroviral therapy, but they do not perform better than other, currently available markers.

Influenza affects older adults disproportionately [1]. Older adults aged ≥65 are estimated to be between 4 and 6 times more likely than younger adults to be hospitalized with influenza and to account for two thirds of influenza inpatient bed days [2, 3]. During the yearly influenza season, influenza is thought to contribute to much of the excess mortality observed in older adults from diverse causes including cardiovascular diseases, stroke, and pneumonia [4, 5].

Frailty, a state of increased vulnerability to adverse health outcomes [6], is increasingly understood to contribute to older adults’ vulnerability to adverse outcomes from influenza [7–9]. Frailty strongly predicts not only mortality but also cognitive decline, disability, and institutionalization in long-term care facilities, all of which are outcomes that are important to older people [10, 11]. Indeed, many older people fear disability, cognitive impairment, and dependence more than death itself [12].

The health impact of influenza is traditionally considered over short time periods, including the acute viral illness, mortality, hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) admission, medical complications, and economic impacts on productivity. However, there is increasing evidence that the acute influenza infection can have lasting health implications, particularly for older adults who are frail, in whom hospital admission is a known independent risk factor for declines in mobility and function [7, 8, 13–15], and frailty is increasingly considered to be a health measure of interest in influenza surveillance and vaccine studies [16–20].

Understanding the impact of influenza on frailty is thus critical to understanding its true burden. Indeed, if influenza infection leaves older adults with lasting increases in frailty, the true burden of influenza may go far beyond the period of acute illness and lead to both lasting health impacts and associated healthcare requirements. Likewise, if lasting increases in frailty are a consequence of influenza infection, preventing influenza through the use of vaccination may be an important means of reducing the burden that frailty places on individuals, families, and health systems. Indeed, those with a previous hospitalization for pneumonia or influenza have a greater risk for hospitalization or death from influenza compared with individuals aged 90 years and older [21]. Thus, frailty could be a self-perpetuating cycle, and the sequelae of an acute influenza illness could in fact extend over much longer time horizons.

In this study, we aimed to study the relationship between frailty and influenza, considering frailty as a candidate predisposing factor for poor recovery after acute illness and as an outcome of illness tracked in a program of active influenza surveillance in sentinel hospitals across Canada.

METHODS

The Canadian Immunization Research Network’s Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS) Network, in collaboration with the Toronto Invasive Bacterial Diseases Network (TIBDN), conducts active surveillance for influenza-related admission to acute care hospitals [22, 23]. This prospective, multicenter study evaluates data collected from academic and community sentinel hospitals during influenza seasons, enrolling adults aged 18 and older admitted to hospital with acute respiratory illness. In this study, we analyzed data from the 2011/2012 (38 hospitals, 6 provinces, 16 000 beds), 2012/2013 (45 hospitals, 7 provinces, 18 000 beds), and 2013/2014 (15 hospitals, 5 provinces, 9000 beds) influenza seasons. Frailty was measured only in those patients aged 65 and older, who comprise the sample for the present study.

Patients

Active surveillance of all patients admitted with broadly defined respiratory or febrile illness was used to identify potential influenza cases. A nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) was obtained from all patients presenting with symptom onset ≤7 days and an admitting diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia, exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, unexplained sepsis, or any respiratory diagnosis or symptom. All NPS were tested for influenza A and B using reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or viral culture (1 site) at the local site according to routine local testing procedures, and results were verified by RT-PCR at the SOS reference central laboratory [24]. Patients with NPS positive for influenza were enrolled as cases. For each case, up to 2 control patients were enrolled who had negative NPS. Cases and controls were matched according to age strata (≥65 or <65 years) and admission date (within 14 days).

Atypical presentations of influenza cases were captured through the use of an enhanced surveillance protocol beginning when the local laboratory reported 2 or more positive influenza tests in 1 single week or 1 or more positive influenza tests in 2 consecutive weeks. Once enhanced surveillance was enacted, on 1 day per week, patients admitted with a stroke or a cardiac diagnosis (eg, acute coronary syndrome, atrial fibrillation, myocarditis) and a triage temperature of 37.5°C were screened. This enhanced surveillance ceased once the local laboratory reported no positive influenza results for 2 consecutive weeks. In TIBDN-associated hospitals, enhanced influenza surveillance for cardiac and stroke patients was performed daily as part of routine clinical practice.

Frailty and Recovery

Frailty status was measured by trained research nurses using a frailty index (FI), which has been previously validated in this dataset [25]. The FI of health and functional deficits was measured at baseline (as charted or described by the patient and/or caregivers reflecting the patient’s status 2 weeks before onset of illness), at the time of enrollment, and again at 30 days after discharge from hospital. The FI used here comprised 39 deficits from 10 domains: cognition, mood, sensory, mobility, nutrition, function in activities of daily living, skin, continence, chronic illness, and medications (see Table 1). These deficits were identified according to published criteria and given scores mapping to the 0–1 interval, with greater scores corresponding to worse health status [26]. Deficits were summed and then divided by the total number of deficits considered to generate an index value from 0 to 1.

Table 1.

Items Included in the 40-Deficit Frailty Index

| Question | Options | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Cognition | WNL | 0 |

| CIND | 0.5 | |

| Dementiaa | 1 | |

| Cognition | Delirium due to illnessb | 1 |

| Fatiguec | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Mood | Within normal limits | 0 |

| Low mood | 0.5 | |

| Depression | 1 | |

| Mood | Anxiety or psychosis/mania | 1 |

| Hearing | Within normal limits | 0 |

| Impaired | 1 | |

| Vision | Within normal limits | 0 |

| Impaired | 1 | |

| Speech | Within normal limits | 0 |

| Impaired | 1 | |

| Transfer | Independent | 0 |

| Assist | 0.5 | |

| Depdendent | 1 | |

| Ambulates | Independent | 0 |

| Assist | 0.5 | |

| Nonambulatory | 1 | |

| Aid | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Balance | Within normal limits | 0 |

| Impaired | 1 | |

| Falls | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Weight | Stable | 0 |

| Gain | 0.5 | |

| Loss | 1 | |

| Bathing | Independent | 0 |

| Assist | 0.5 | |

| Depdendent | 1 | |

| Toileting | Independent | 0 |

| Assist | 0.5 | |

| Depdendent | 1 | |

| Meds | Independent | 0 |

| Assist | 0.5 | |

| Depdendent | 1 | |

| Dressing | Independent | 0 |

| Assist | 0.5 | |

| Depdendent | 1 | |

| Eating | Independent | 0 |

| Assist | 0.5 | |

| Depdendent | 1 | |

| Finances | Independent | 0 |

| Assist | 0.5 | |

| Depdendent | 1 | |

| Ulcers | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Edema | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Bladder | Continent | 0 |

| Incontinent/catheter | 1 | |

| Bowel | Continent | 0 |

| Incontinent/catheter | 1 | |

| Endocrine | No | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus (with or without complication) | 1 | |

| Cardiac | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| 2 or more of angina, arrhythmia, valvular, previous MI, congestive heart failure, or other cardiac checked | 2 | |

| Vascular | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| 2 or more of peripheral vascular, hypertension, cerebrovascular, or other vascular checked | 2 | |

| Pulmonary | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| 2 or more of asthma, COPD, or other pulmonary checked | 2 | |

| Renal | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Neuromuscular | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Liver | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Gastrointestinald | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Cancer | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Rheumatologic | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Other chronic illness | No | 0 |

| Yes and check at least one of HIV, sickle cell disease, previous splenectomy/functional asplenia, liver transplant, lung transplant, kidney transplant, bone marrow transplant, immunosuppressed/immunocompromised, cochlear implant, alcoholism, other substance abuse | 1 | |

| Medication | 0–4 | 0 |

| 5–7 | 0.5 | |

| 8–13 | 1 | |

| ≥14 | 2 |

Abbreviations: CIND, cognitive impairment no dementia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MI, myocardial infraction; WNL, within normal limits.

aNo score will be assigned if dementia is the only checked illness under neuromuscular.

bDelirium due to illness is not captured at baseline. Patients are assumed not having this disease at baseline.

cFatigue was not collected in season 2011–2012.

dNo score will be assigned if peptic ulcer is the only illness under gastrointestinal.

Baseline frailty was categorized using published cutoffs (0–0.1 nonfrail, >0.1–0.21 prefrail, >0.21–0.45 frail, >0.45 most frail) [27]. Recovery after hospitalization was defined as being alive 30 days postdischarge with less than 2 additional health or functional deficits (≤0.06 FI increase); although a FI change of 0.03 (1 deficit) is detectable, the accumulation of 2 health deficits was used here because it provides a more stringent test of clinical meaningfulness [28]. Patients were excluded from analysis if FI at baseline was missing or if clinical status (FI or death) 30 days after discharge was missing. Clinical outcomes at 30 days were determined by contact with the patient and/or family/substitute decision maker, which could have been by phone or during a subsequent contact with the healthcare system (eg, if they were readmitted to the same hospital).

Statistical Methods

A χ 2 test was used to compare categorical variables and analysis of variance was used to compare continuous variables across seasons and influenza types. Logistic regression was used to examine the change in odds of recovery for every 0.1 increase in baseline FI, controlling for age, sex, season, laboratory-confirmed influenza status, and seasonal influenza vaccination status. Logistic regression analyses were conducted separately for each influenza season. We also investigated whether sex, age, vaccination status, or influenza status modified the relationship between baseline frailty and recovery by testing interaction terms. Statistical analyses were done using SPSS and R software packages.

This research protocol was approved by the research ethics boards of participating institutions (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT 01517191). Data collection was performed according to local Research Ethics Board requirements.

RESULTS

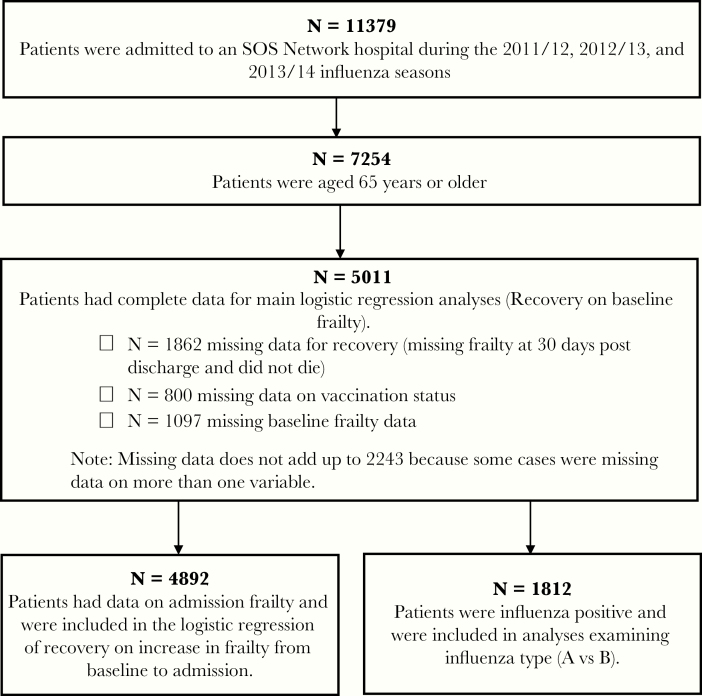

In total, 11 379 patients were admitted to an SOS Network hospital during the 2011/2012, 2012/2013, and 2013/2014 influenza seasons, and 7254 of these were 65 years of age or older. We omitted 2243 patients due to missing data. See Table 2 for comparison of omitted and included patients. See Figure 1 for participation flow chart. Of note, included participants were less frail, less likely to test positive for influenza, and more likely to recover compared with omitted participants.

Table 2.

Comparison of Omitted and Included Participantsa

| Variable | Omitted | Included | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (N = 2243/5011) | 80.1 (8.6) | 79.4 (8.4) | <.01 |

| Female (N = 2243/5011) | 1159 (51.7%) | 2661 (53.1%) | .26 |

| Influenza positive (N = 2243/5011) | 1136 (50.6%) | 1812 (36.2%) | <.001 |

| Vaccination status (N = 1443/5011) | 868 (60.2%) | 3433 (68.5%) | <.001 |

| Influenza A (N = 1135/1812) | 769 (67.9%) | 1223 (67.5%) | .83 |

| Baseline frailty (N = 1146/5011) | 0.24 (0.12) | 0.22 (0.12) | <.001 |

| Admission frailty (N = 1171/4892) | 0.30 (0.14) | 0.28 (0.14) | <.001 |

| Frailty 30 days postdischarge (N = 188/4455) | 0.24 (0.13) | 0.22 (0.13) | <.05 |

| Recovered (N = 381/5011) | 129 (33.9%) | 3941 (78.6%) | <.001 |

| Season (N = 2243/5011) 2011 | 228 (10.2%) | 698 (13.9%) | <.001 |

| 2012 | 1039 (46.3%) | 1980 (39.5%) | |

| 2013 | 976 (43.5%) | 2333 (46.6%) |

aIndependent samples t test (continuous variables) and χ 2 tests of independence (categorical variables) were used to test for differences between omitted and included participants.

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart. SOS, Serious Outcomes Surveillance.

In total, 5011 patients aged 65 years or older were included in our analyses (See Table 3). The mean age was 79.4 (standard deviation = 8.37) years; 53.1% were women (n = 2661). At baseline (2 weeks before the onset of acute illness), 15.0% (n = 750) were nonfrail, 39.3% (n = 1971) were prefrail, 39.8% (n = 1995) were frail, and 5.9% (n = 295) were most frail. A total of 68.5% had received an influenza vaccination for that season (n = 3433). Please see Table 4 for descriptive statistics by influenza strain.

Table 3.

Patient Characteristics by Season

| Variable | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | Significancea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 698 | n = 1980 | n = 2333 | ||

| Influenza case | 167 (23.9%) | 870 (43.9%) | 775 (33.2%) | P < .001 |

| Type A | 49 (29.3%) | 815 (93.7%) | 359 (46.3%) | P < .001 |

| Type B | 118 (70.7%) | 55 (6.3%) | 416 (53.7%) | |

| Age mean (SD) | 79.2 (SD 8.1) | 79.7 (SD 8.4) | 79.3 (SD 8.4) | P = .13 |

| Sex, n (%) women | 398 (57.0%) | 1032 (52.1%) | 1231 (52.8%) | P = .08 |

| Vaccinated N (%) | 484 (69.3%) | 1320 (68.7%) | 1629 (69.8%) | P = .07 |

| Baseline frailty index, mean FI (SD) | 0.20 (SD 0.11) | 0.22 (SD 0.12) | 0.23 (SD 0.13) | P < .001 |

| Frailty at admission, mean FI (SD) | 0.26 (SD 0.13) | 0.29 (SD 0.13) | 0.28 (0.14) | P < .001 |

| Frailty at 30 days postdischarge, mean (SD) | 0.20 (0.11) | 0.22 (0.13) | 0.22 (0.13) | P < .001 |

| Deceased 30 days postdischarge, N (%) | 53 (7.6%) | 238 (12.0%) | 265 (11.4%) | P < .01 |

| Recovered, N (%) | 581 (83.2%) | 1494 (75.5%) | 1866 (80.0%) | P < .001 |

Abbreviations: FI, frailty index; SD, standard deviation.

aAnalysis of variance (continuous variables) or χ 2 (categorical variables), as appropriate. For frailty at admission N = 691 in 2011/2012, N = 1935 in 2012/2013, N = 2266 in 2013/2014. For frailty at discharge N = 645 in 2011/2012, N = 1742 in 2012/2013, and N = 2068 in 2013/2014.

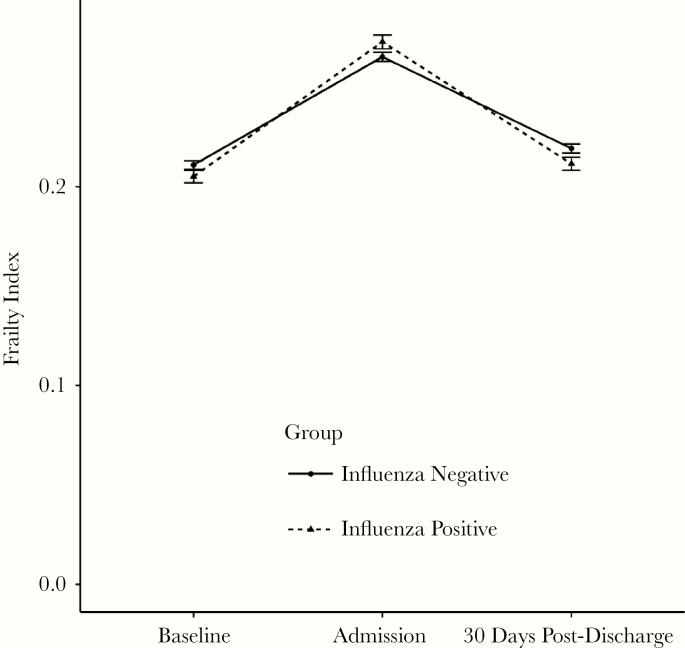

At 30 days after discharge, the majority of surviving patients were still prefrail (n = 1742, 34.8%) or frail (n = 1738, 34.7%). Please see Figure 2 for graph of frailty over time by influenza status. The number of nonfrail patients remained largely unchanged at 30 days postdischarge (14.0%, n = 703), as did the number of most frail patients (5.4%, n = 272). At 30 days postdischarge, 556 (11.1%) of patients were deceased. Poor recovery was experienced by 21.4% of patients (n = 1070 of 5011 patients): 556 (52.0%) had died and 514 (48%) had experience an increase in frailty of 0.06 or more.

Figure 2.

Mean (±standard error) frailty index levels for influenza-positive and -negative participants. N = 4467 (alive at 30 days postdischarge and a computed frailty index for all 3 time points).

Controlling for age, sex, vaccination status, and influenza status, baseline frailty was associated with lower odds of recovery in all 3 seasons (2011/2012 [odds ratio {OR} = 0.70; 95% confidence interval {CI}, 0.59–0.84], 2012/2013 [OR = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.66–0.79], 2013/2014 [OR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.69–0.82]). When we added interaction terms to the model, frailty interacted with vaccination status in the 2011/2012 season such that frailty was associated with poor recovery in unvaccinated (OR = 0.45; 95% CI, 0.31–0.65) but not vaccinated patients (OR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.68–1.03). In the 2012/2013 season, frailty interacted with influenza status such that there was a stronger effect of frailty on poor recovery in influenza cases (OR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.58–0.75) compared with control participants (OR = 0.78; 95% CI, = 0.69–0.67). None of the interaction terms were statistically significant in the 2013/2014 season.

Of the 4892 participants for whom we had both baseline and admission frailty, 2153 (43.0%) experienced an increase in frailty from baseline to admission of ≥0.06 (2 additional deficits). After controlling for age, sex, vaccination status, and influenza status, this increase in frailty was associated with decreased odds of recovery in all 3 seasons (2011/2012 [OR = 0.35; 95% CI, 0.23–0.53], 2012/2013 [OR = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.39–0.60], 2013/2014 [OR = 0.35; 95% CI, 0.28–0.44]).

Of the 1812 participants who tested positive for influenza, 1223 patients (67.5%) were diagnosed with influenza A, and 589 patients were diagnosed with influenza B (32.5%). In general, the population characteristics did not differ between (1) patients diagnosed with influenza versus influenza negative controls or (2) between influenza A and B (Table 2).

For those with laboratory-confirmed influenza infection, frailty was associated with statistically significant lower odds of recovery in 2012/2013 (OR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.58–0.75; A/H3N2 dominant season) and 2013/2014 (OR = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.63–0.83; A/H1N1 dominant season) but not in 2011/2012 (in which 4 strains cocirculated and a marked decrease in hospitalization rates was observed in hospitalized adults aged ≥65 years) [23, 29]. Of particular note, among those with laboratory-confirmed influenza in any season, the odds of recovery after influenza B and influenza A did not differ (2011/2012: 83.7% influenza A both H1N1 and H3N2 vs 72.9% influenza B, P = .14; 2012/2013: 77.7% influenza A/H3N2 vs 72.7% influenza B, P = .40; 2013/2014: 80.5% A/H1N1 vs 77.9% B, P = .37).

DISCUSSION

Increasing baseline frailty was consistently associated with lower odds of recovery in older adults admitted with influenza and other acute respiratory and febrile illnesses, although the association varied across seasons and by influenza status. Outcomes were similarly poor for influenza A and B.

Frailty was associated with statistically significant lower odds of recovery from laboratory-confirmed influenza in both the 2013/2014 and the 2012/2013 influenza seasons. It is worth noting that during the 2012/2013 influenza season, in which H3N2 was the circulating A strain, influenza infections were found to be particularly severe in elderly people [30], whereas the 2011/2012 influenza season (with 4 cocirculating strains) was found to be “remarkably mild” in the United States and was similarly mild in Canada [23, 29, 31].

In 2011/2012, although frailty was not found to be associated with poor recovery overall, frailty was found to be statistically significantly associated with poor recovery in unvaccinated older adults with laboratory-confirmed influenza infection, but not in older adults with laboratory-confirmed influenza who had been vaccinated. This supports prior reports that influenza vaccination may help to prevent the most serious outcomes, even if it does not prevent the influenza infection itself [32, 33]. If this is the case, vaccine effectiveness may be higher against more serious outcomes (eg, ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, mortality) than less serious outcomes [32]. This association also suggests that depending on seasonal factors, such as vaccine effectiveness and circulating influenza strains, vaccination may provide some protection from the impact of frailty on recovery. It is notable that, in 2011/2012, we found that vaccination was associated with greater odds of recovery, and it indeed appeared to buffer the negative impact of frailty on recovery. Given the impact of frailty on quality of life, and associated increased vulnerability to serious health events, disability, and death, influenza vaccination represents an important opportunity to maintain health and function [34]. The study of frailty outcomes of influenza is an emerging field. A study in Thailand found that mild acute influenza illness did not seem to impact frailty status assessed in the short term, although few cases of severe illness were included and only 2 participants were hospitalized [35]. This suggests that the resilience of older adults to recover from influenza likely varies according to the severity of the insult.

It is interesting to note that there did not appear to be any association between influenza type and odds of recovery. This is in contrast to the once commonly held belief that influenza B may be less severe in adults [36–39]. More recently, however, studies have found that both influenza A and B are of comparable severity, as is also suggested by our own findings in the hospital setting [40, 41]. It is also likely that in frail older adults, widely used indicators of severity (eg, ICU admission and mechanical ventilation) do not adequately capture a full picture of severity, and the consideration of longer terms impacts on frailty and function may help to complete the picture [9, 25, 42].

It is interesting to note that any illness, particularly those that result in hospitalization, could result in decline in a vulnerable older adult. Influenza is one among many infectious causes of hospitalization from acute respiratory illness; other pathogens and illnesses including respiratory syncytial virus and bacterial pneumonia also lead to hospitalizations and declines in health status with worsening frailty. However, influenza is notable for 2 main reasons: it is both common and potentially preventable (eg, with better vaccines and improved vaccine uptake). In addition, it has been hypothesized that dysregulated immune responses to influenza could lead to outcomes for older adults that are worse than those for noncommunicable illnesses, admission for which make up a substantial part of our control group [7].

Our findings should be interpreted with caution. Limitations of this study include its observational design and the difficulty in generalizing findings across seasons, given differences in circulating viruses and vaccine effectiveness. Viral culture was used at a single site. The results were confirmed with PCR at the central laboratory. Because both cases (positive) and controls (negative test) from all sites including the site using viral culture were included in the second round of confirmatory testing by PCR, this difference in methodology should not have impacted our results. In the event of 1 positive and 1 negative test (ie, a discrepancy between testing methods), the patient was registered as a flu positive case. In practice, such discrepancies were rare. We identified similar trends across 3 influenza seasons, although it is useful to consider the season characteristics in the interpretation of our results. The 2011/2012 influenza season was relatively mild and was characterized by 4 circulating strains (A/H3N2, A/H1N1, and both influenza B lineages) with influenza B viruses accounting for 53% or more of virus detections nationally and 65.5% of laboratory-confirmed influenza cases among patients admitted to hospital and enrolled in the SOS Network that season [23, 25, 31]. The 2012/2013 season was largely dominated by influenza A/H3N2, followed by a later peak of influenza B [30]. Finally, influenza A/H1N1 was the predominant virus in 2013/2014, with a late season increase in influenza B [22, 43]. Estimates of vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization have been published for these seasons in the SOS Network; the pooled adjusted vaccine effectiveness estimate for adults aged 65 and older was 39.3% (95% CI, 29.4%–47.8%) for the prevention of hospitalization and 74.5% (44.0%–88.4%) for the prevention of influenza-related death [23]. We have also previously reported that vaccine effectiveness appears to decrease with increasing frailty [25].

Patients who were missing frailty at baseline and/or at follow up were excluded from these analyses. In general, patients with missing data tended to be older, frailer, and sicker than those with complete data. Specifically, patients with known baseline FI but missing follow-up frailty were more frail at baseline than those in whom frailty data were complete; this is consistent with prior experience that those with missing data tend to be more frail than those in whom the data can be collected [44]. As a consequence, our results may be conservative and may underestimate the impact of hospitalization with acute respiratory illness on the most vulnerable. Nevertheless, our study also has certain strengths, including a large-scale observational setting, with centers reporting from across Canada, active surveillance protocols with broad case definitions for enrollment, and the use of PCR to confirm the diagnosis of influenza and influenza type. Our prospective collection of frailty data across 3 seasons is a particularly unique feature of the SOS Network.

CONCLUSIONS

The population of frail older adults is large and growing. We have previously found that there is a frailty bias in influenza vaccine effectiveness, in that frail older adults are more likely to receive an influenza vaccine, but it may have lower vaccine effectiveness [25]. In this study, we have found that frailty is associated with poor recovery after hospital admission for influenza. As such, not taking frailty into consideration in studies of influenza vaccination and burden of disease is likely to consistently underestimate the true burden of influenza for older adults and thus underestimate the benefits of prevention efforts including influenza vaccination. Attention to how influenza impacts the health and lives of this vulnerable population in both the acute phase and the longer term is critical to understanding the true burden of influenza-related illness. In addition to preventing hospitalization and death, prevention of worsening frailty status represents an important aim of influenza immunization for older adults.

Table 4.

Characteristics by Influenza Straina

| Variable | Influenza A (N = 1223) (67.5%) | Influenza B (N = 589) (32.5%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza Season | P < .001 | ||

| 2011/2012 N (%) | 49 (4.0%) | 118 (20.0%) | |

| 2012/2013 N (%) | 815 (66.6%) | 55 (9.3%) | |

| 2013/2014 N (%) | 359 (29.4%) | 416 (70.6%) | |

| Mean age | 79.5 (SD 8.6) | 81.4 (SD = 8.7) | P < .001 |

| Sex N (%) female | 612 (50.0%) | 328 (55.7%) | P < .05 |

| Vaccinated N (%) | 724 (59.2%) | 373 (63.3%) | P = .09 |

| Baseline frailty | 0.22 (SD 0.13) | 0.23 (SD = 0.14) | P = .05 |

| Admission frailty (N = 1190/573) | 0.29 (SD 0.14) | 0.29 (SD 0.15) | P = .97 |

| Frailty index at 30 days postdischarge (N = 1087/505) | 0.21 (SD 0.13) | 0.22 (SD 0.13) | P = .44 |

| Mortality (30 days postdischarge) N (%) | 136 (11.1%) | 84 (14.3%) | P = .06 |

| Recovered N (%) | 963 (78.7%) | 450 (76.4%) | P = .26 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation.

aIndependent samples t tests (continuous variables) or χ 2 tests (categorical variables) were used to compare influenza A and influenza B.

Notes

Presented in part: ID Week 2017, 4–8 October 2017, San Diego, California.

Disclaimer. The authors are solely responsible for final content and interpretation. The authors received no financial support or other form of compensation related to the development of the manuscript.

Financial support. Funding for this study was provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) and through an investigator-initiated Collaborative Research Agreement with GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA.

Potential conflicts of interest. J. E. M. reports payments to her institution from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Sanofi, Pfizer, Medicago, and RestorBio outside of the submitted work. S. A. M. reports payments from the GSK group of companies, during the conduct of the study, and payments from Pfizer, GSK, Merck, Novartis, and Sanofi, outside the submitted work. M. L. reports payments from Sanofi, Medicago, Sequirus, and Pfizer outside the submitted work. T. F. H. reports payments from the GSK and Pfizer group of companies, during the conduct of the study. J. L. reports payments to his institution from the GSK group of companies for the conduct of this study and payments from Pfizer and Merck outside of the submitted work. A. M. reports payments to her institution from the GSK group of companies for the conduct of this study and payments from GSK, Seqirus, and Sanofi Pasteur, outside the submitted work. A. P. reports the following: grants from CIRN Network, during the conduct of the study; and payments from Sunovion, outside the submitted work. J. P. reports grants from Gilead, outside the submitted work. M. S. reports payments from the GSK group of companies and Pfizer, during the conduct of the study. M. K. A. reports grant payments to her institution from the GSK group of companies for the conduct of this study and payments and grant funding from the GSK group of companies, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur, outside the submitted work. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Thommes EW, Kruse M, Kohli M, Sharma R, Noorduyn SG. Review of seasonal influenza in Canada: burden of disease and the cost-effectiveness of quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2017; 13:867–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Simonsen L, Fukuda K, Schonberger LB, Cox NJ. The impact of influenza epidemics on hospitalizations. J Infect Dis 2000; 181:831–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fleming D, Harcourt S, Smith G, Influenza and adult hospital admissions for respiratory conditions in England 1989–2001. Commun Dis Public Health 2003; 6:231–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reichert TA, Simonsen L, Sharma A, et al. Influenza and the winter increase in mortality in the United States, 1959–1999. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 160:492–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnstone J, Loeb M, Teo KK, et al. ; Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global EndPoint Trial (ONTARGET); Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators Influenza vaccination and major adverse vascular events in high-risk patients. Circulation 2012; 126:278–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hogan DB, MacKnight C, Bergman H; Steering Committee, Canadian Initiative on Frailty and Aging Models, definitions, and criteria of frailty. Aging Clin Exp Res 2003; 15:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McElhaney JE, Zhou X, Talbot HK, et al. The unmet need in the elderly: how immunosenescence, CMV infection, co-morbidities and frailty are a challenge for the development of more effective influenza vaccines. Vaccine 2012; 30:2060–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Monto AS, Ansaldi F, Aspinall R, et al. Influenza control in the 21st century: optimizing protection of older adults. Vaccine 2009; 27:5043–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andrew MK, Bowles SK, Pawelec G, et al. Influenza vaccination in older adults: recent innovations and practical applications. Drugs Aging 2019; 36:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005; 173:489–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rockwood K, Mitnitski A, Song X, Steen B, Skoog I. Long-term risks of death and institutionalization of elderly people in relation to deficit accumulation at age 70. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54:975–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Losing independence is a bigger ageing worry than dying 2009. Available at: http://www.dlf.org.uk/blog/losing-independence-bigger-ageing-worry-dying. Accessed 16 March 2020.

- 13. Boyd CM, Landefeld CS, Counsell SR, et al. Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56:2171–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kortebein P, Symons TB, Ferrando A, et al. Functional impact of 10 days of bed rest in healthy older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008; 63:1076–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51:451–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ferdinands JM, Gaglani M, Martin ET, et al. Prevention of influenza hospitalization among adults in the United States, 2015–2016: results from the US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (HAIVEN). J Infect Dis 2019; 220:1265–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Segaloff HE, Petrie JG, Malosh RE, et al. Severe morbidity among hospitalised adults with acute influenza and other respiratory infections: 2014–2015 and 2015–2016. Epidemiol Infect 2018; 146:1350–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Petrie JG, Martin ET, Zhu Y, et al. Comparison of a frailty short interview to a validated frailty index in adults hospitalized for acute respiratory illness. Vaccine 2019; 37:3849–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Narang V, Lu Y, Tan C, et al. Influenza vaccine-induced antibody responses are not impaired by frailty in the community-dwelling elderly with natural influenza exposure. Front Immunol 2018; 9:2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moehling KK, Nowalk MP, Lin CJ, et al. The effect of frailty on HAI response to influenza vaccine among community-dwelling adults ≥ 50 years of age. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018; 14:361–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hak E, Wei F, Nordin J, Mullooly J, Poblete S, Nichol KL. Development and validation of a clinical prediction rule for hospitalization due to pneumonia or influenza or death during influenza epidemics among community-dwelling elderly persons. J Infect Dis 2004; 189:450–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McNeil S, Shinde V, Andrew M, et al. Interim estimates of 2013/14 influenza clinical severity and vaccine effectiveness in the prevention of laboratory-confirmed influenza-related hospitalisation, Canada, February 2014. Euro Surveill 2014; 19:20729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nichols MK, Andrew MK, Hatchette TF, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness to prevent influenza-related hospitalizations and serious outcomes in Canadian adults over the 2011/12 through 2013/14 influenza seasons: a pooled analysis from the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS Network). Vaccine 2018; 36:2166–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. LeBlanc JJ, ElSherif M, Mulpuru S, et al. Validation of the Seegene RV15 multiplex PCR for the detection of influenza A subtypes and influenza B lineages during national influenza surveillance in hospitalized adults. J Med Microbiol 2020; 69:256–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Andrew MK, Shinde V, Ye L, et al. ; Serious Outcomes Surveillance Network of the Public Health Agency of Canada/Canadian Institutes of Health Research Influenza Research Network (PCIRN) and the Toronto Invasive Bacterial Diseases Network (TIBDN) The importance of frailty in the assessment of influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza-related hospitalization in elderly people. J Infect Dis 2017; 216:405–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr 2008; 8:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoover M, Rotermann M, Sanmartin C, Bernier J. Validation of an index to estimate the prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling seniors. Health Rep 2013; 24:10–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eendebak R, Theou O, van der Valk A, et al. Defining minimal important differences and establishing categories for the frailty index. Innov Aging 2018; 2(Suppl 1):715–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Andrew MK, Shinde V, Hatchette T, et al. ; Public Health Agency of Canada/Canadian Institutes of Health Research Influenza Research Network (PCIRN) Serious Outcomes Surveillance Network and the Toronto Invasive Bacterial Diseases Network (TIBDN) Influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza-related hospitalization during a season with mixed outbreaks of four influenza viruses: a test-negative case-control study in adults in Canada. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17:805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization. Review of the 2012–2013 winter influenza season, northern hemisphere. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2013; 22:225–32. [Google Scholar]

- 31. World Health Organization. Review of the 2011–2012 winter influenza season, northern hemisphere. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2012; 24:233–40. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Castilla J, Godoy P, Domínguez A, et al. ; CIBERESP Cases and Controls in Influenza Working Group Spain Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing outpatient, inpatient, and severe cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:167–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Talbot HK, Griffin MR, Chen Q, Zhu Y, Williams JV, Edwards KM. Effectiveness of seasonal vaccine in preventing confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations in community dwelling older adults. J Infect Dis 2011; 203:500–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bilotta C, Bowling A, Casè A, et al. Dimensions and correlates of quality of life according to frailty status: a cross-sectional study on community-dwelling older adults referred to an outpatient geriatric service in Italy. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010; 8:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hughes MM, Praphasiri P, Dawood FS, et al. Effect of acute respiratory illness on short-term frailty status of older adults in Nakhon Phanom, Thailand-June 2015 to June 2016: a prospective matched cohort study. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2019; 13:391–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. The pathology of influenza virus infections. Annu Rev Pathol 2008; 3:499–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kaji M, Watanabe A, Aizawa H. Differences in clinical features between influenza A H1N1, A H3N2, and B in adult patients. Respirology 2003; 8:231–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Simonsen L, Clarke MJ, Williamson GD, Stroup DF, Arden NH, Schonberger LB. The impact of influenza epidemics on mortality: introducing a severity index. Am J Public Health 1997; 87:1944–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thompson WW, Moore MR, Weintraub E, et al. Estimating influenza-associated deaths in the United States. Am J Public Health 2009; 99(Suppl 2):S225–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gutiérrez-Pizarraya A, Pérez-Romero P, Alvarez R, et al. Unexpected severity of cases of influenza B infection in patients that required hospitalization during the first postpandemic wave. J Infect 2012; 65:423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chagvardieff A, Persico N, Marmillot C, Badiaga S, Charrel R, Roch A. Prospective comparative study of characteristics associated with influenza A and B in adults. Med Mal Infect 2018; 48:180–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McElhaney JE, Andrew MK, McNeil SA. Estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness: evolution of methods to better understand effects of confounding in older adults. Vaccine 2017; 35:6269–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. World Health Organization. Review of the 2013–2014 winter influenza season, northern hemisphere. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2014; 23:245–56. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Andrew MK. Social vulnerability in old age. In: Fillit HM, Rockwood K, Young J, eds. Brocklehurst’s Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2016: pp 185–92. [Google Scholar]