Abstract

Background

Suicidal thinking during non-fatal overdose may elevate risk for future completed suicide or intentional overdose. Long-term outcomes following an intentional non-fatal overdose may be improved through specific intervention and prevention responses beyond those designed for unintentional overdoses, yet little research has assessed suicidal intent during overdoses or defined characteristics that differentiate these events from unintentional overdoses.

Methods

Patients with a history of opioid overdose (n=274) receiving residential addiction treatment in the Midwestern United States completed self-report surveys to classify their most recent opioid overdose as unintentional, actively suicidal (“wanted to die”), or passively suicidal (“didn’t care about the risks”). We characterized correlates of intent using descriptive statistics and prevalence ratios. We also examined how intent related to thoughts of self-harm at the time of addiction treatment.

Results

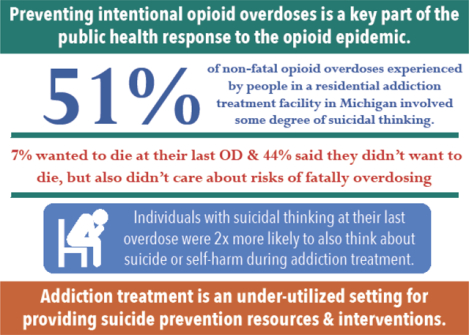

Of opioid overdoses, 51% involved suicidal intent (44% passive and 7% active). Active suicidal intent was positively associated with hospitalization. Active/passive intent (vs. no intent, aPR: 2.2, 95% CI: 1.4–3.5) and use of ≥5 substances (vs. 1 substance, aPR: 3.6, 95% CI: 1.2–10.6) at the last opioid overdose were associated with having thoughts of self-harm or suicide in the two weeks before survey completion in adjusted models. Participants who reported active/passive intent more commonly used cocaine or crack (27%) with opioids during their last overdose relative to unintentional overdoses (16%).

Conclusions

Over half of opioid overdoses among individuals in addiction treatment involved some degree of suicidal thinking. Identifying patients most at risk will facilitate better targeting of suicide prevention and monitoring services.

Keywords: Overdose, Suicide, Opioids, Polysubstance Use

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Opioid overdose mortality rates increased 5-fold during 1999–2017 (NIDA, 2018). Though >90% of opioid overdose fatalities are classified as unintentional in multiple cause of death data (Olfson et al., 2019), some evidence indicates that the role of suicidal intent in overdose risk may be substantial, although this is not well understood (Bohnert and Ilgen, 2019). Suicidal intent may be present in upwards of one-third of non-fatal opioid or sedative overdoses and is associated with increased overdose severity (Bohnert et al., 2018). The highly elevated risk of death from suicide in the year following a non-fatal opioid overdose (Olfson et al., 2018a) underscores the importance of accurately characterizing the intent of an overdose. Further, suicide-related events among people with substance use disorders may often be misclassified as unintentional and moreover, may involve suicidal thinking rather than an overt or obvious suicidal intent (Bohnert et al., 2013; Rockett et al., 2018).

Passive suicidal ideation and intent, defined as a general wish to be dead (Van Orden et al., 2010), may underlie many overdose events (Bohnert et al., 2013, 2018). In contrast, active suicidal intent refers to the wish to take one’s own life and to engage in the behaviors required to do so (Van Orden et al., 2010). Suicidal thinking may also exist along a continuum of severity. In a sample of patients receiving psychiatric care that were asked to rate the strength of their wish to die at their last opioid overdose on a scale of 0 to 10, nearly 60% of patients reported some level of wanting to die (score of >0), and 36% had a strong wish to die (defined as a score of ≥7 or higher) (Connery et al., 2019). Because active and passive suicidal ideation are rarely evaluated during assessments of overdose events and risk, intentional overdoses remain a poorly understood component of overdose surveillance. However, summarizing the prevalence and correlates of ideation during opioid overdoses could illuminate important pathways for prevention.

Concomitant substance use alongside opioids increases the likelihood and severity of an overdose due to drug-drug interactions (Cone et al., 2004; Ruttenber et al., 1990; van der Schrier et al., 2017) and influences whether medical care is received after a non-fatal overdose (Bohnert et al., 2018). The type and number of drugs used prior to overdose may be linked to suicidal intent as well. For example, suicide risk has been linked to opioid use (Bohnert and Ilgen, 2019), alcohol and benzodiazepine use (Wines et al., 2004), and in some cases, concomitant use of opioids and cocaine (Betts et al., 2015). Polysubstance combinations used during non-fatal opioid overdoses and their relationship to depression, suicidal intent, and overdose severity have not been examined. These overdose characteristics could inform future suicide and overdose prevention planning.

Because intentional overdoses may be commonly misclassified as unintentional, many patients do not receive suicide prevention interventions or timely care to reduce future suicide risk after an intentional overdose. Past depression and suicidal ideation are, not surprisingly, strong predictors of future suicidal ideation and attempts (Wines et al., 2004), including in individuals with substance use disorders. In one prospective study, a history of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation predicted suicidal behavior after discharge from an inpatient detoxification facility, with 7% of patients attempting suicide within two years (Wines et al., 2004). Thus, characterizing whether depressive symptoms or suicidal thinking are present at critical points of healthcare engagement, such as residential rehabilitation and detoxification, may identify opportunities for the assessment of suicidal thinking and intentional overdose risk and for the implementation of suicide prevention interventions. The importance of the addiction treatment setting as a point of engagement is further underscored by the high prevalence of prior non-fatal overdose in this patient population (Bohnert et al., 2010; Martins et al., 2015).

Understanding the circumstances of non-fatal overdose events, including the degree of suicidal intent, substances used, and medical care received, is essential to defining the optimal design and appropriate settings for integrated suicide risk reduction and opioid overdose prevention efforts. This study explored the role of suicidal intent in non-fatal overdose experiences among individuals in residential addiction treatment for a substance use disorder and characterized relationships between suicidal intent, polysubstance use, and overdose outcomes (e.g., hospitalization) following a non-fatal opioid overdose. We also examined how intent related to depressive symptoms and suicidal thinking at the time of addiction treatment. We hypothesized that patients with suicidal intent at their last opioid overdose would be more likely to experience a severe overdose requiring medical attention, more likely to report an event involving polysubstance use, and more likely to report depressive symptoms or suicidal thinking at the time of receiving addiction treatment services.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Description

Data for the present analysis came from a sample of 817 adult patients who were receiving residential treatment for a substances use disorder at a treatment facility in suburban Michigan during 2014–2016. Eligible patients, who were aged ≥18 years and able to provide informed consent, were approached by research staff and, after providing informed consent, self-administered a survey that assessed eligibility for a randomized controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02152397). The analytic sample was restricted to 274 participants who self-reported that they had ever personally experienced an overdose and that their most recent overdose involved prescription opioids or heroin, and who had complete data on measures of interest (described further below). This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Measures and Statistical Analysis

Participants reported whether they had ever experienced an overdose (defined on the survey as “taking too much drugs or medications/pills…sometimes called ‘poisoning,’ ‘nodding out,’ or an ‘overdose’ or ‘OD’”) (Tracy et al., 2005), the number of drug overdoses they had personally experienced in their lifetime, and the substance(s) involved in their most recent overdose (marijuana, alcohol, prescription stimulants, prescription sedatives or sleeping pills, prescription opioids, over the counter medications, energy drinks, cocaine or crack, methamphetamines, inhalants, hallucinogens, or heroin). This information was used to restrict the sample to overdose events involving prescription opioids or heroin and characterize substances used in addition to opioids. The overdose events described in this study could have occurred at any time prior to study involvement.

Active suicidal intent at last opioid overdose was defined as taking too much drugs or alcohol “On purpose, [they] wanted to die,” and passive suicidal intent was defined as “Didn’t want to die, but didn’t care about the risks either.” Participants who reported they took too much “accidentally” or were “unsure” about their intent were considered to have had an overdose without suicidal intent (hereafter referred to as an unintentional overdose). Receipt of medical care after the last opioid overdose was self-reported in a “choose all that apply” format, including whether participants’ last opioid overdose involved calling 911 (response choices: “I called 911” or “Someone else called 911”), going to the emergency room (“I was taken to the Emergency Room [ER] in an ambulance” or “Someone took me to the ER [not in an ambulance]”), or being hospitalized (“I was admitted to the hospital”).

Participants’ depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts in the two weeks before the survey (i.e., during the time of addiction treatment, and not during the period immediately following their opioid overdose) were characterized using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a validated brief screening for depression severity (Kroenke et al., 2001). We examined PHQ-9 scores as a continuous variable and classified depressive symptom severity and evidence for major depressive symptoms using validated scoring thresholds (Kroenke et al., 2001). We also characterized whether participants were experiencing thoughts of suicide or self-harm using the 9th question of the PHQ-9, which read: “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by…thoughts you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way?”. Participants’ responses were examined as reported (i.e., as a four-level variable) and as a dichotomized variable comparing those who said “Not at all” vs. having thoughts on “Several days,” “More than half the days,” or “Nearly every day.” We also examined how depressive symptoms impacted participants’ functioning using the 10th PHQ-9 question, which read: “If you checked of any problems [on the PHQ-9], how difficult have these problems made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people?”. We examined this as a four-level categorical variable and as a dichotomous variable comparing those who reported these problems made functioning “Not difficult at all” or “Somewhat difficult” vs. “Very difficult” or “Extremely difficult.”

We used descriptive statistics and prevalence ratios calculated using Poisson generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors (Zou, 2004) to summarize 1) how suicidal intent related to polysubstance use and medical attention received during participants’ most recent overdose, 2) how suicidal intent during participants’ most recent overdose related to later depressive symptoms, suicidal thinking, and functioning in the context of depressive symptoms during the time of addiction treatment (i.e., assessed in the two weeks prior to completing of the survey) and 3) how polysubstance use during participants’ most recent opioid overdose were associated with receipt of medical attention immediately following the most recent opioid overdose. Adjusted models included demographic characteristics (age, race, and gender) and statistically significant bivariate correlates (p<0.05). In adjusted models examining the association of active or passive intent with depressive symptoms, suicidal thinking, or functioning in the context of depressive symptoms, we also adjusted for the amount of time since the last overdose (past 6 months, >6 months but ≤1 year, >1 year ago).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Last Non-Fatal Opioid Overdose

Among 274 participants who had experienced a non-fatal opioid overdose, 78% used heroin and 43% used prescription opioids (Table 1). Over 70% of participants’ most recent non-fatal overdoses had occurred in the last year and 47% had experienced ≥5 drug overdoses in their lifetime. In addition to opioids, 40% of most recent non-fatal overdoses involved sedatives/sleeping pills, 25% alcohol, 25% marijuana, 22% cocaine or crack, and <10% other substances. On average, participants used a median of 2 substances (interquartile range: 1–3). Nearly half (48%) of opioid overdoses involved emergency medical services (either calling 911 or visiting the emergency room) and 26% resulted in hospitalization.

Table 1.

Characteristics of last non-fatal opioid overdose and correlates of suicidal intent among a sample of 274 people who use opioids receiving addiction treatment services, Michigan, 2014–2016

| Total n (%) | Active or Passive Suicidal Intent n (%) | Unintentional n (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 274 (100) | 139 (50.7) | 135 (49.3) | - |

| Race | ||||

| African American | 21 (7.7) | 6 (4.3) | 15 (11.1) | 0.10 |

| White | 230 (83.9) | 120 (86.3) | 110 (81.5) | |

| Multi-racial or other race | 23 (8.4) | 13 (9.4) | 10 (7.4) | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 30.5 (25–37) | 29 (25–36) | 33 (26–41) | 0.03a |

| Female | 94 (34.3) | 50 (36.0) | 44 (32.6) | 0.64 |

| Number of lifetime overdoses | ||||

| 1 | 40 (14.6) | 15 (10.8) | 25 (18.5) | 0.008 |

| 2–4 | 105 (38.3) | 46 (33.1) | 59 (43.7) | |

| ≥5 | 129 (47.1) | 78 (56.1) | 51 (37.8) | |

| Timing of last overdose relative to time of survey participation | ||||

| Within the last 6 months | 125 (45.6) | 71 (51.1) | 54 (40.0) | 0.11 |

| >6 months but ≤1 year ago | 68 (24.8) | 34 (24.5) | 34 (25.2) | |

| >1 year ago | 81 (29.6) | 34 (24.5) | 47 (34.8) | |

| Opioids used in last overdose | ||||

| Heroin (only) | 156 (56.9) | 77 (55.3) | 79 (58.5) | 0.07 |

| Prescription opioids (only) | 61 (22.3) | 26 (18.7) | 35 (25.9) | |

| Heroin and prescription opioids | 57 (20.8) | 36 (25.9) | 21 (15.6) | |

| Substances other than opioids used in last overdose | ||||

| Prescription sedatives or sleeping pills | 109 (39.8) | 60 (43.2) | 49 (36.3) | 0.30 |

| Alcohol | 69 (25.2) | 36 (25.9) | 33 (24.4) | 0.89 |

| Marijuana | 68 (24.8) | 41 (29.5) | 27 (20.0) | 0.09 |

| Cocaine or crack | 59 (21.5) | 38 (27.3) | 21 (15.6) | 0.03 |

| Energy drinks | 21 (7.7) | - | - | |

| Prescription stimulants | 21 (7.7) | - | - | |

| Methamphetamines | 19 (6.9) | - | - | |

| Hallucinogens | 7 (2.6) | - | - | |

| Over the counter drugs | 6 (2.2) | - | - | |

| Inhalants | 2 (0.7) | - | - | |

| Number of substances used | ||||

| 1 | 89 (32.5) | 42 (30.2) | 47 (34.8) | 0.17 |

| 2 | 81 (29.6) | 37 (26.6) | 44 (32.6) | |

| 3–4 | 63 (23.0) | 33 (23.7) | 30 (22.2) | |

| ≥5 | 41 (15.0) | 27 (19.4) | 14 (10.4) | |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.19a |

| Medical involvement in last overdose | ||||

| Called 911 | 101 (36.9) | 49 (35.3) | 52 (38.5) | 0.66 |

| Went to the emergency room | 113 (41.2) | 59 (42.4) | 54 (40.0) | 0.77 |

| Hospitalized | 72 (26.3) | 34 (24.5) | 38 (28.1) | 0.58 |

Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. IQR: Interquartile range.

3.2. Suicidal Intent

At their last opioid overdose, approximately 44.1% (95% CI: 38.3%−50.0%) of participants reported they did not care about the risks of taking too much drugs/alcohol (passively suicidal) and 6.6% (95% CI: 3.6%−9.5%) reported they wanted to die (actively suicidal). Approximately half (49.3%, 95% CI: 43.4%−55.2%) of participants reported that their overdose was unintentional. Of these, 121 participants reported their overdose was unintentional and 14 participants reported they were “unsure” about the reason. Participants who were actively or passively suicidal during their non-fatal opioid overdose more commonly used cocaine or crack in addition to opioids (27% used cocaine or crack) than participants who overdosed unintentionally (16% used cocaine or crack). Actively suicidal participants were more commonly hospitalized (50% [n=9]) relative to passively suicidal (21% [n=25]) or unintentional overdoses (28% [n=38], p=0.03).

Over half (58%) of participants in the entire sample reported experiencing moderate or severe depressive symptoms during the two weeks prior to completing the survey (i.e., after their overdose and during the time of treatment, Table 2). Relative to participants who experienced an unintentional overdose, participants who were actively or passively suicidal during their non-fatal opioid overdose more commonly reported moderate or more severe depressive symptoms (67% vs. 48%) and more commonly reported thinking they would be better off dead or thought about hurting themselves on several days or more in the two weeks prior to the survey (31% vs. 14%). Whereas 45% of participants who had been actively or passively suicidal at their last overdose reported difficulty functioning given their depressive symptoms in the last two weeks, only 27% of those who had experienced an unintentional overdose reported these difficulties.

Table 2.

Depressive symptoms and suicidal intent at the time of treatment stratified by intent at last non-fatal opioid overdose among a sample of 274 people who use opioids receiving addiction treatment services, Michigan, 2014–2016

| Total | Active or Passive Suicidal Intent n (%) | Unintentional n (%) | Chi-Squared p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 274 (100) | 139 (50.7) | 135 (49.3) | |

| Total PHQ-9 Score, Median (IQR) | 11 (6–17) | 12 (8–18) | 9 (5–15) | 0.003a |

| Severity of depressive symptoms | ||||

| Normal (Score: 0–4) | 50 (18.2) | 21 (15.1) | 29 (21.5) | 0.03 |

| Mild (Score: 5–9) | 66 (24.1) | 25 (18.0) | 41 (30.4) | |

| Moderate (Score: 10–14) | 67 (24.5) | 41 (29.5) | 26 (19.3) | |

| Moderately Severe (Score: 15–19) | 54 (19.7) | 29 (20.9) | 25 (18.5) | |

| Severe (Score: ≥20) | 37 (13.5) | 23 (16.5) | 14 (10.4) | |

| Frequency of thoughts that participant would be better off dead or hurting oneself | ||||

| None | 212 (77.4) | 96 (69.1) | 116 (85.9) | 0.01 |

| Several days | 30 (10.9) | 21 (15.1) | 9 (6.7) | |

| More than half of days | 21 (7.7) | 14 (10.1) | 7 (5.2) | |

| Nearly every day | 11 (4.0) | 8 (5.8) | 3 (2.2) | |

| Difficulty working, taking care of things at home, getting along with people because of these thoughts | ||||

| Not difficult at all | 52 (19.0) | 20 (14.4) | 32 (23.7) | 0.004 |

| Somewhat difficult | 123 (44.9) | 57 (41.0) | 66 (48.9) | |

| Very difficult | 69 (25.2) | 39 (28.1) | 30 (22.2) | |

| Extremely difficult | 30 (10.9) | 23 (16.5) | 7 (5.2) |

Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. IQR: Interquartile range.

Experiencing active or passive suicidal thoughts at the last overdose remained associated with depressive symptoms, thoughts of self-harm or suicide, and difficulty functioning after adjustment for several demographic factors and correlates of the last overdose (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 1). Those who had reported being actively or passively suicidal at their last overdose were 2.2-fold more likely to report thoughts of suicide or self-harm in the two weeks prior to the survey (95% CI: 1.4–3.5) after adjustment for the time since the most recent overdose, use of opioids, marijuana, and cocaine or crack at the last overdose, the number of substances used at the last overdose, the number of drug overdoses personally experienced by the participant in their lifetime, age, race, and gender. Use of a greater number of substances at the last overdose was also associated with a higher likelihood of reporting recent thoughts of suicide or self-harm and high levels of difficulty functioning due to depressive symptoms in a dose-dependent manner, with those using 5 or more substances at the last overdose being 3.6-fold more likely to report thoughts of suicide or self-harm (95% CI: 1.2–10.6).

Table 3.

Correlates of depressive symptoms and suicidal intent at the time of treatment with characteristics of last non-fatal opioid overdose among a sample of 274 people who use opioids receiving addiction treatment services, Michigan. 2014–2016.

| Evidence of MDDa, aPR (95 % CI) | Thoughts of suicide or self harmb, aPR (95 % CI) | Tasks very/extremely difficultc, aPR (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal intent at last OD | 1.37 (1.10–1.69) | 2.19 (1.35–3.54) | 1.44 (1.03–2.01) |

| Number of lifetime ODs | |||

| 1 | - | ref | ref |

| 2–4 | - | 2.41 (0.72–8.01) | 2.01 (0.94–4.27) |

| ≥5 | - | 2.97 (0.94–9.35) | 2.3 (1.09–4.87) |

| Timing of last OD | |||

| Within the last 6 months | 1.17 (0.88–1.56) | 1.67 (0.91–3.07) | 1.26 (0.81–1.97) |

| > 6 Months to ≤ 1 year ago | 1.27 (0.94–1.72) | 2.08 (1.11–3.89) | 1.72 (1.06–2.78) |

| > 1 Year ago | ref | ref | ref |

| Opioid use at last OD | |||

| POs only | 1.23 (0.93–1.63) | 0.89 (0.44–1.78) | 1.26 (0.82–1.93) |

| Heroin and POs | 1.30 (0.97–1.74) | 1.01 (0.55–1.86) | 0.93 (0.61–1.42) |

| Heroin only | ref | ref | ref |

| Marijuana at last OD | - | 0.70 (0.37–1.33) | 0.71 (0.45–1.13) |

| Cocaine/crack at last OD | - | 0.88 (0.51–1.50) | 0.91 (0.62–1.32) |

| # Substances used at last OD | |||

| 1 | ref | ref | ref |

| 2 | 0.98 (0.73–1.30) | 1.40 (0.71–2.76) | 1.22 (0.74–2.01) |

| 3–4 | 1.02 (0.74–1.42) | 1.73 (0.78–3.82) | 2.05 (1.21–3.47) |

| ≥5 | 1.08 (0.77–1.52) | 3.57 (1.21–10.58) | 3.58 (1.78–7.22) |

| African American | 1.29 (0.96–1.74) | 1.51 (0.86–2.67) | 1.01 (0.58–1.76) |

| Female | 0.99 (0.79–1.23) | 0.83 (0.52–1.34) | 1.07 (0.77–1.48) |

| Age | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) |

aPR: adjusted prevalence ratio, OD: overdose, POs: prescription opioids.

Associations of correlates (adjusted for all others shown) with a score of a ≥10 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, indicating moderate, moderately severe, or severe depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks.

Associations of correlates (adjusted for all others shown) with endorsing thoughts the participant would be better off dead or hurting themselves on several days, more than half of days, or nearly every day in the past 2 weeks.

Associations of correlates (adjusted for all others shown) with indicating that problems on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 made it very difficult or extremely difficult to do their work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people in the past 2 weeks.

3.3. Medical Involvement after Last Non-Fatal Opioid Overdose

In bivariate analysis, participants who used prescription sedatives or sleeping pills were more likely to receive medical attention after their last non-fatal opioid overdose (i.e., 911 call, emergency room visit, or hospitalization, Supplemental Table 2). African American participants less commonly visited the emergency room. Participants who used both heroin and prescription opioids were more commonly hospitalized.

As shown in Table 4, after adjustment for demographic characteristics (age, race, and gender), using prescription sedatives or sleeping pills remained associated with calling 911 (aPR: 1.5, 95% CI: 1.1–2.0), visiting the emergency room (aPR: 1.4, 95% CI: 1.1–1.8), and hospitalization (aPR: 1.4, 95% CI: 1.0–1.9). African American participants remained less likely to visit the emergency room (aPR: 95% CI: 0.4, 0.1–1.0), though the prevalence ratio estimates lack precision, likely due to the small number of African Americans included in this sample (n=21).

Table 4.

Correlates of medical involvement during last opioid overdose among a sample of 274 people who use opioids receiving addiction treatment services, Michigan, 2014–2016

| Called 911 aPR (95% CI) | Emergency Room Visit aPR (95% CI) | Hospitalized aPR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid use at last OD | |||

| POs only | - | - | 0.70 (0.45–1.09) |

| Heroin & POs | - | - | 1.09 (0.78–1.53) |

| Heroin only | - | - | ref |

| Prescription sedatives or sleeping pills at last OD | 1.46 (1.08–1.98) | 1.39 (1.06–1.84) | 1.40 (1.04–1.88) |

| African American | 0.35 (0.12–1.00) | 0.35 (0.12–0.99) | 0.35 (0.12–1.02) |

| Female | 1.21 (0.88–1.66) | 1.18 (0.89–1.57) | 1.18 (0.89–1.57) |

| Age | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) |

Abbreviations: POs: Prescription Opioids, PR: prevalence ratio.

4. Discussion

In this addiction treatment sample, over half of participants intended to take their own life during their last opioid overdose or reported feelings of apathy about their risks of fatally overdosing. The largest prior study distinguishing passive from active suicidal intent in overdose survivors was in a sample recruited from an emergency department, wherein 39% of participants reported suicidal intent when asked to recall their most severe overdose event (Bohnert et al., 2018). Likewise, 59% of participants receiving psychiatric treatment reported some level of wanting to die during their last opioid overdose (Connery et al., 2019). Taken together, the high proportion of drug overdose events that involve passive and active suicidal intent in studies across various clinical settings indicate suicidal intent is an overlooked driver of overdose worthy of future research and clinical attention. The idea that the response to the opioid crisis must integrate suicide risk reduction into opioid overdose prevention programs to maximally reduce mortality has been only recently highlighted (Oquendo and Volkow, 2018; Bohnert and Ilgen, 2019; Gordon and Volkow, 2019). The present study supports that the potential impact of such a change in approach has even greater importance than previously understood.

The similar prevalence of active and passive ideation in samples from several clinical settings (i.e., the emergency department, a psychiatric treatment facility, and this addiction treatment facility) is notable and identifies several potential locations to evaluate overdose and suicide risks. Emergency department and psychiatric settings may identify medically severe events that have occurred very recently, perhaps even within the hours following an intentional overdose. On the other hand, the prevalence of intentional overdose history was similarly high in this addiction treatment sample, wherein history of non-fatal overdose was also prevalent. Many patients reported recent suicidal thinking or depressive symptoms later, during the time they were engaged with addiction treatment, which may exacerbate their risks of future intentional overdose. A multi-pronged intentional overdose prevention response in multiple clinical settings is required, and should include the addiction treatment setting.

We found that active or passive intent at the most recent overdose was associated with a greater than two-fold increase in the likelihood of thoughts of suicide or self-harm during addiction treatment. This finding suggests that assessing suicidal thinking and providing care related to suicide prevention may be important in the addiction treatment setting. Future research could examine whether suicide and overdose harm reduction services provided during addiction treatment mitigate the increased risk of fatal overdose immediately following treatment (Davoli et al., 2007). Further, whether suicidal thinking is persistent versus intermittent in the time after intentional overdose, and whether history of intentional overdose or suicidal thinking during treatment increases the risk of fatal overdose following treatment (Strang et al., 2003) have yet to be characterized.

Actively suicidal participants more commonly reported hospitalization after overdosing. Though our study was unable to describe the suicide prevention services received by these patients during hospitalization, the inpatient hospital setting is another important access point and opportunity for integration of suicide prevention and post-overdose care. The associations of concomitant opioid and sedative/sleeping pill use (e.g., benzodiazepines) with emergency medical involvement and hospitalization likely reflect the increased severity of overdoses involving substances with known drug-drug interactions (Jones and McAninch, 2015). The utility of suicide risk reduction among these individuals could be explored in future work given the increasing trend in overdose deaths from concomitant use of benzodiazepines and opioids (Jones and McAninch, 2015).

Crack and cocaine use emerged as a correlate of suicidal intent prior to opioid overdose. Nearly one-quarter of participants used cocaine or crack with opioids during their last overdose, a combination that has been associated with fatal overdose (Coffin et al., 2003). This finding is consistent with a prior study reporting that co-use of opioids and stimulants was associated with a higher risk of non-fatal overdose only among participants experiencing psychological distress (Betts et al., 2015) and may also reflect the association of major depression with cocaine use and cocaine use disorder (John and Wu, 2017). Likewise, using 5 or more drugs together before the last overdose was associated with a 3.6-fold increase in reporting thoughts of self-harm during addiction treatment. This finding implies that individuals who have used both opioids and cocaine or crack or who report polysubstance use more generally may particularly benefit from suicide risk assessment and referral to psychiatric services as necessary. These patients could be engaged through venues such as syringe services programs, addiction treatment services, or in the emergency department after a non-fatal overdose (Des Jarlais et al., 2015; Park et al., 2018; Stahler et al., 2016).

Although our sample was primarily white, it was notable that opioid overdoses experienced by the few African American participants in our study less commonly resulted in an emergency room visit relative to other racial and ethnic groups. This finding warrants further study and underscores a need to examine drivers of racial/ethnic disparities in overdose-related emergency care in diverse study populations. This finding could also reflect an avoidance of calling 911 due to fear of arrest in the context of discriminatory enforcement of drug laws, which has been documented in other studies with primarily African American participants (Latimore and Bergstein, 2017; Tobin et al., 2005).

4.1. Limitations

This cross-sectional, secondary analysis of self-reported data had a limited sample size and power to detect differences between intentional and unintentional overdoses or explore the potential for effect measure modification. Nonetheless, the descriptive findings we report, together with the handful of other studies on intentional overdose, should be used to guide the design of future, adequately powered studies. Additionally, suicidal intent is likely under-reported (Calear and Batterham, 2019) for many reasons, including fears related to stigma, hospitalization, or loss of autonomy (Blanchard and Farber, 2018; Richards et al., 2019). Our study lacked data on the type of hospitalization (e.g., overdose-related, psychiatric, or other), severity of the overdose event based on presentation (e.g., loss of consciousness), year of the overdose event, or co-habitation or marital status during the overdose event. The experiences and intent of non-fatal overdoses may not reflect those leading to fatal overdoses, and thus inferences may not generalize to mortality reduction efforts, although non-fatal overdose is also an important goal of prevention and a strong predictor of future fatal overdose (Kelty and Hulse, 2017; Olfson et al., 2018b; Stoové et al., 2009). The few actively suicidal participants and racial/ethnic minorities limited our ability to further describe overdose circumstances among these groups.

Finally, the crude assessment of time since prior overdose as a categorical variable did not permit us to conduct a formal time-to-event analysis of the association of active or passive suicidal intent at the most recent overdose with suicidal intent or depressive symptoms at the time of treatment. The strong association of reporting active or passive intent at the last overdose with thoughts of suicide or self-harm during treatment, which persisted even after adjustment for other characteristics of the overdose event, suggests that a more complete characterization of the patterns of persistent suicidal thinking following an intentional overdose is warranted. In particular, future research may benefit from a mixed methods approach coupling a description of lived experiences of suicidal thinking with quantitative assessments that more accurately capture the spectrum of severity of suicidal thinking beyond the suicide and self-harm screening question in the PHQ-9 (Connery et al., 2019; Richards et al., 2019).

4.2. Conclusions

Suicidal intent, and particularly passive intent, likely has an important and under-recognized role in the opioid overdose epidemic. A number of prevention interventions could address both overdose and suicide risk together, but the present findings suggest an even greater emphasis on suicide risk in the opioid overdose response is warranted. Brief suicide risk assessments during emergency care, addiction treatment, and in settings that reach individuals who use opioids and other drugs may improve overdose outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Surveyed 274 people receiving addiction treatment about most recent opioid overdose

7% said they wanted to die and 44% didn’t care about the risks during last overdose

Active/passive intent at OD associated with recent suicide/self-harm thoughts

Active suicidal intent associated with hospitalization following opioid overdose

Overdose prevention should routinely assess and address suicide risk

Acknowledgements

We thank Emily Yeagley for providing project oversight. We also thank the participants and staff at the addiction treatment facility where data were collected.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R34DA035331, T32AI102623, and K23AA023869).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared.

References

- Betts KS, McIlwraith F, Dietze P, Whittaker E, Burns L, Cogger S, Alati R, 2015. Can differences in the type, nature or amount of polysubstance use explain the increased risk of non-fatal overdose among psychologically distressed people who inject drugs? Drug Alcohol Depend. 154, 76–84. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard M, Farber BA, 2018. “It is never okay to talk about suicide”: Patients’ reasons for concealing suicidal ideation in psychotherapy. Psychother. Res. J. Soc. Psychother. Res 1–13. 10.1080/10503307.2018.1543977 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA, 2019. Understanding Links among Opioid Use, Overdose, and Suicide. N. Engl. J. Med 380, 71–79. 10.1056/NEJMra1802148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert ASB, McCarthy JF, Ignacio RV, Ilgen MA, Eisenberg A, Blow FC, 2013. Misclassification of suicide deaths: examining the psychiatric history of overdose decedents. Inj. Prev. J. Int. Soc. Child Adolesc. Inj. Prev 19, 326–330. 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert ASB, Roeder K, Ilgen MA, 2010. Unintentional overdose and suicide among substance users: A review of overlap and risk factors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 110, 183–192. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert ASB, Walton MA, Cunningham RM, Ilgen MA, Barry K, Chermack ST, Blow FC, 2018. Overdose and adverse drug event experiences among adult patients in the emergency department. Addict. Behav 86, 66–72. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calear AL, Batterham PJ, 2019. Suicidal ideation disclosure: Patterns, correlates and outcome. Psychiatry Res. 278, 1–6. 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin PO, Galea S, Ahern J, Leon AC, Vlahov D, Tardiff K, 2003. Opiates, cocaine and alcohol combinations in accidental drug overdose deaths in New York City, 1990–98. Addict. Abingdon Engl. 98, 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone EJ, Fant RV, Rohay JM, Caplan YH, Ballina M, Reder RF, Haddox JD, 2004. Oxycodone involvement in drug abuse deaths. II. Evidence for toxic multiple drug-drug interactions. J. Anal. Toxicol 28, 616–624. 10.1093/jat/28.7.616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connery HS, Taghian N, Kim J, Griffin M, Rockett IRH, Weiss RD, Kathryn McHugh R, 2019. Suicidal motivations reported by opioid overdose survivors: A cross-sectional study of adults with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 205, 107612 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoli M, Bargagli AM, Perucci CA, Schifano P, Belleudi V, Hickman M, Salamina G, Diecidue R, Vigna-Taglianti F, Faggiano F, VEdeTTE Study Group, 2007. Risk of fatal overdose during and after specialist drug treatment: the VEdeTTE study, a national multi-site prospective cohort study. Addict. Abingdon Engl 102, 1954–1959. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Nugent A, Solberg A, Feelemyer J, Mermin J, Holtzman D, 2015. Syringe Service Programs for Persons Who Inject Drugs in Urban, Suburban, and Rural Areas - United States, 2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 64, 1337–1341. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6448a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J, Volkow N, 2019. Suicide Deaths Are a Major Component of the Opioid Crisis that Must Be Addressed. NIMH Dir. Messag URL https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/director/messages/2019/suicide-deaths-are-a-major-component-of-the-opioid-crisis-that-must-be-addressed.shtml (accessed 11.1.19).

- John WS, Wu L-T, 2017. Trends and correlates of cocaine use and cocaine use disorder in the United States from 2011 to 2015. Drug Alcohol Depend. 180, 376–384. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.08.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, McAninch JK, 2015. Emergency Department Visits and Overdose Deaths From Combined Use of Opioids and Benzodiazepines. Am. J. Prev. Med 49, 493–501. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelty E, Hulse G, 2017. Fatal and non-fatal opioid overdose in opioid dependent patients treated with methadone, buprenorphine or implant naltrexone. Int. J. Drug Policy 46, 54–60. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, 2001. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med 16, 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimore AD, Bergstein RS, 2017. “Caught with a body” yet protected by law? Calling 911 for opioid overdose in the context of the Good Samaritan Law. Int. J. Drug Policy 50, 82–89. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Sampson L, Cerdá M, Galea S, 2015. Worldwide Prevalence and Trends in Unintentional Drug Overdose: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Am. J. Public Health 105, 2373 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302843a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIDA, 2018. Overdose Death Rates [WWW Document]. URL https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates (accessed 10.24.18).

- Olfson M, Crystal S, Wall M, Wang S, Liu S-M, Blanco C, 2018a. Causes of Death After Nonfatal Opioid Overdose. JAMA Psychiatry 75, 820–827. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Rossen LM, Wall MM, Houry D, Blanco C, 2019. Trends in Intentional and Unintentional Opioid Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2000–2017. JAMA 322, 2340–2342. 10.1001/jama.2019.16566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Wall M, Wang S, Crystal S, Blanco C, 2018b. Risks of fatal opioid overdose during the first year following nonfatal overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 190, 112–119. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Volkow ND, 2018. Suicide: A Silent Contributor to Opioid-Overdose Deaths. N. Engl. J. Med 378, 1567–1569. 10.1056/NEJMp1801417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JN, Weir BW, Allen ST, Chaulk P, Sherman SG, 2018. Fentanyl-contaminated drugs and non-fatal overdose among people who inject drugs in Baltimore, MD. Harm. Reduct. J 15, 34 10.1186/s12954-018-0240-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JE, Hohl SD, Whiteside U, Ludman EJ, Grossman DC, Simon GE, Shortreed SM, Lee AK, Parrish R, Shea M, Caldeiro RM, Penfold RB, Williams EC, 2019. If You Listen, I Will Talk: the Experience of Being Asked About Suicidality During Routine Primary Care. J. Gen. Intern. Med 34, 2075–2082. 10.1007/s11606-019-05136-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett IRH, Caine ED, Connery HS, D’Onofrio G, Gunnell DJ, Miller TR, Nolte KB, Kaplan MS, Kapusta ND, Lilly CL, Nelson LS, Putnam SL, Stack S, Värnik P, Webster LR, Jia H, 2018. Discerning suicide in drug intoxication deaths: Paucity and primacy of suicide notes and psychiatric history. PloS One 13, e0190200 10.1371/journal.pone.0190200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruttenber AJ, Kalter HD, Santinga P, 1990. The role of ethanol abuse in the etiology of heroin-related death. J. Forensic Sci 35, 891–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahler GJ, Mennis J, DuCette JP, 2016. Residential and outpatient treatment completion for substance use disorders in the U.S.: Moderation analysis by demographics and drug of choice. Addict. Behav 58, 129–135. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoové MA, Dietze PM, Jolley D, 2009. Overdose deaths following previous non-fatal heroin overdose: record linkage of ambulance attendance and death registry data. Drug Alcohol Rev. 28, 347–352. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang J, McCambridge J, Best D, Beswick T, Bearn J, Rees S, Gossop M, 2003. Loss of tolerance and overdose mortality after inpatient opiate detoxification: follow up study. BMJ 326, 959–960. 10.1136/bmj.326.7396.959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin KE, Davey MA, Latkin CA, 2005. Calling emergency medical services during drug overdose: an examination of individual, social and setting correlates. Addiction 100, 397–404. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00975.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy M, Piper TM, Ompad D, Bucciarelli A, Coffin PO, Vlahov D, Galea S, 2005. Circumstances of witnessed drug overdose in New York City: implications for intervention. Drug Alcohol Depend. 79, 181–190. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Schrier R, Roozekrans M, Olofsen E, Aarts L, van Velzen M, de Jong M, Dahan A, Niesters M, 2017. Influence of Ethanol on Oxycodone-induced Respiratory Depression: A Dose-escalating Study in Young and Elderly Individuals. Anesthesiology 126, 534–542. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite S, Selby EA, Joiner TE, 2010. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychol. Rev 117, 575–600. 10.1037/a0018697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wines JD, Saitz R, Horton NJ, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Samet JH, 2004. Suicidal behavior, drug use and depressive symptoms after detoxification: a 2-year prospective study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 76 Suppl, S21–29. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou G, 2004. A Modified Poisson Regression Approach to Prospective Studies with Binary Data. Am. J. Epidemiol 159, 702–706. 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.