Abstract

Background

Studies have reported the impact of chronic childhood and adolescent tic disorder (TD) on families. However, few researches focused on the relationship between family environment and diagnosis of TD. We aim to assess the influence of couple relationship and family structure on the onset of TD.

Methods

A total of 660 parents of patients with TD (aged 6–12 years) and 641 parents of controls completed questionnaires. Couple relationship and family structure were selected by regression of binary logistic analysis as the risk factors. Couple relationship was divided into the harmonious, common, hostile, and divorced. Family structure included unconventional family, nuclear family, and unite family. Multivariate correspondence analysis was designed to explore relationships among categorical variables of couple relationship and family structure.

Results

There were significant associations between TD and couple relationship (Exp B = 1.310, p = .006, 95% CI = 1.080–1.590), family structure (Exp B = 0.668, p = .001, 95% CI = 0.526 ~ 0.847), gender (Exp B = 0.194, p < .001, 95% CI = 0.149–0.254), respectively. Obviously contradicted and common couple relationships were risk factors for TD compared with the harmonious and divorced. Children form unconventional family or nuclear family were prone to develop TD. Interestingly, divorced parents had the same protective effect as harmonious parents. The OR value could increase with the number and level of those risk factors.

Conclusions

In conclusion, children from nuclear families with bad parental relationship could be more likely to develop tic symptoms. The family intervention of children with TD should focus on family structure and parental relationship.

Keywords: couple relationship, family structure, gender, tic disorder

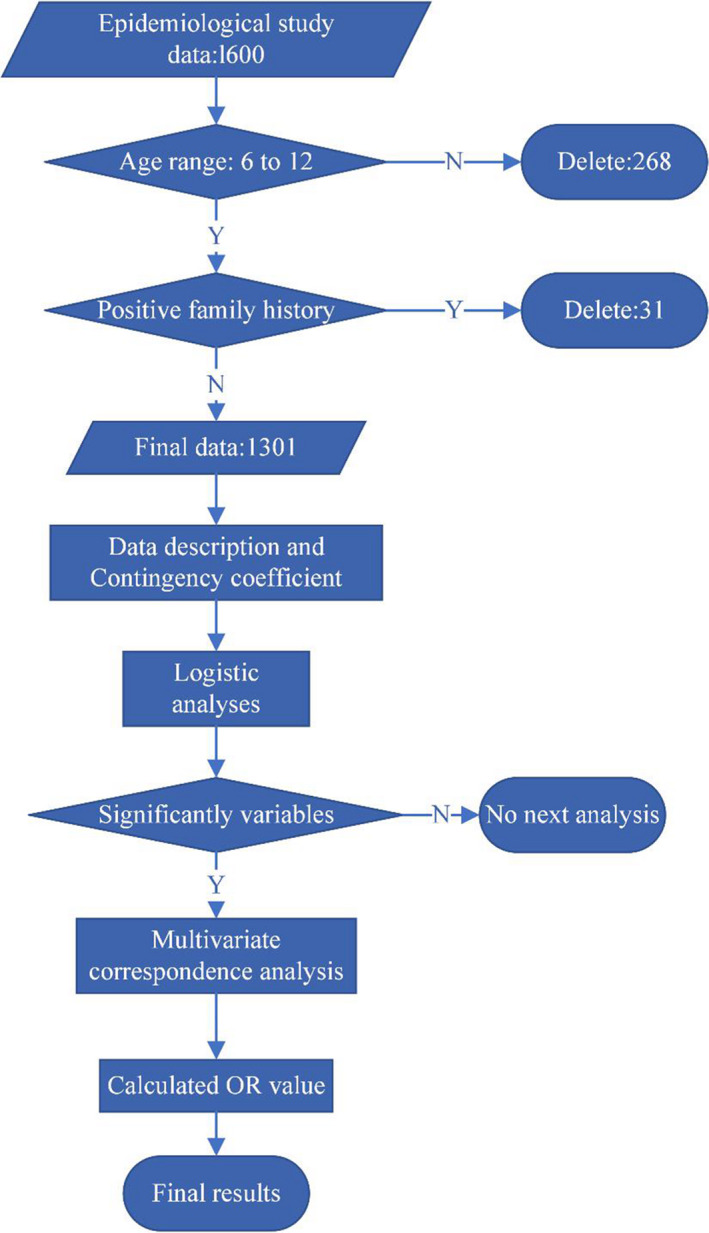

Flow diagram of data analysis.

What this paper adds.

Unconventional and nuclear family were risk factors for children to develop tic disorder (TD).

Unharmonious couple relationship was risk for children to develop TD.

Divorce could be protective for children compared with those unharmonious couples.

The superimposition of risk factors can increase the probability of TD.

The family intervention of children with TD should focus on family structure and parental relationship.

1. INTRODUCTION

Tic disorder (TD) is a childhood onset neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by motor or vocal tics (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Hallett, 2015). A meta‐analysis of the worldwide prevalence of TDs indicated that transient tic disorder (TTD) was the most common, with a prevalence of 2.99%. The prevalence of Tourette syndrome(TS)and chronic tic disorder (CTD) was 0.77% and 1.61% (Knight et al., 2012), respectively. The prevalence of TD was 6.1% in China with 1.7% TTD, 1.2% CTD and 0.3% TS (Yang, Zhang, Zhu, Zhu, & Guo, 2016). TDs can have a profoundly emotional and social impact on children and families, which can in turn have a reciprocal impact on tics (Evans, Wittkowski, Butler, Hedderly, & Bunton, 2016). TD children may experience subjective discomfort (pain or injury), sustained social problems (social isolation or bullying), and emotional problems (reactive depressive symptom; Roessner et al., 2011). Augustine et al. (2017) thought TD could influence on individuals, families, and communities (Dutta & Cavanna, 2013; Evans, Wittkowski, Butler, Hedderly, & Bunton, 2015; Kadam & Chuan, 2016). The health‐related quality of life, anxiety, and depression of TS adolescents and their parents were shown to be affected by TS (Dutta & Cavanna, 2013; Evans et al., 2015; Jalenques et al., 2017; Kadam & Chuan, 2016). Goussé et al. (2016) had found that most parents of TD children had a high level of anxiety‐depression. A Canadian population‐based study concluded that individuals with TS experienced a higher frequency of anxiety and mood disorders, and required more assistance with activities of daily living than the general population (Yang et al., 2017).

Unfortunately, there is no cure for TD now, and we need to explore effective treatments to diminish the severity and frequency of TD (Cath et al., 2011). Besides pharmacological help (Schlander, Schwarz, Rothenberger, & Roessner, 2011), certain intervention or support is required to manage tics and impaired social, emotional, and behavioral functioning. Complex neurobiological and genetic mechanisms, prenatal and perinatal infections, as well as environmental factors are thought to interact with each other in the development of TD (Tagwerker & Walitza, 2016). The severity of TS and co‐occurring conditions were proved to be associated with school challenges and educational service needs (Claussen, Bitsko, Holbrook, Bloomfield, & Giordano, 2018). There were many studies interested in the impact of family on chronic childhood and adolescent TD, while few studies have focused on the relationship between family environment and diagnosis of TD (Hong et al., 2013). In this study, we are looking forward to finding family risk factors related to TD by the epidemiological study and providing potential intervention suggestions.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design and participants

The case group included 660 families with tic children (from outpatient), who diagnosed with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (version 5.0) by Pediatrics of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine from 1 January 2008 to 30 March 2014. The ages of participants ranged from 6 to 12 years without family history of TD, epilepsy and other neurological or mental illness. The TD patients in our research do not have other co‐occurring conditions like ADHD, OCD, impulsive and self‐injurious behavior. They were excluded by specialists in Pediatric Tic Disorder Specialist Clinic. All specialists in the clinic have a background in neuropsychiatry. Of the 660 patients in the case group, 434 had TTD, 117 had chronic motor or vocal TD, and 109 had TS. They were classified into three types according to severity: 245 mild patients with YGTSS ≤ 24 points, 370 moderate patients with YGTSS about 25–50 points and 45 severe patients with YGTSS about 51–100 points.

We handed out the questionnaires to parents of TD children by specialists and asked them to fill in it before their second visit. The control data was gotten from the questionnaire finished by parents of 641 primary school students without TD from Yangpu District at the same age. Both them were given 1 week to finish it seriously. All data were inputted by two postgraduates by excel and checked by the third party. Flow diagram of data analysis are shown in Figure 1. Investigators obtained the informed consent before enrolling participants in the study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine (XHEC‐D‐2018‐033).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of data analysis

2.2. Questionnaire and setting

The questionnaire used in this research has been identified by five specialists in this field, with the reliability coefficient r = .7523 and internal consistency coefficient α = 0.8123. The questionnaire includes three parts: Family Factors, Perinatal and Past History Factors, and Diet Factors. The original variables of family factors included family structure (1 = nuclear family, 2 = stem family, 3 = unite family, 4 = broken family, 5 = inter‐generational family, 6 = single family), single child or not (1 = yes, 2 = no), parents’ education level (1 = postgraduate, 2 = graduate, 3 = junior college, 4 = secondary professional education school, 5 = technical school, 6 = senior high school, 7 = junior high school, 8 = primary school, 9 = illiteracy), relationship of parents (1 = harmonious, 2 = common, 3 = disharmony, 4 = divorce) and home environment (1 = quiet, 2 = commonly quiet, 3 = noisy). Family structure comprised the following categories on the basis of current living arrangement: unconventional family, nuclear family, and unite family. In accordance with the education law of the PRC (Education Law of the People's Republic of China, 2015), Parents’ education level was reordered as illiteracy (1), compulsory education (2 include junior high school, primary school), non‐compulsory secondary education (3 include secondary professional education school, technical school, senior high school), junior college (4), graduate (5), and postgraduate (6). A new variable was created by subtracting the value of mother's education level from the father's to describe the different of parents’ education level. To ensure that the assignment was 1 and above, the result of the subtraction should pulse 4. The value less than 4 meant that fathers’ education levels were lower than mothers’ and more than 4 was the opposite. The extreme value represents a greatly different education levels of parents. The value assignment of variables was shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Value assignment of variables

| Factors description | Choices | Value assignment |

|---|---|---|

| Family structure | Unconventional family | 1 |

| Nuclear family | 2 | |

| Unite family | 3 | |

| Single child or not | Single child | 1 |

| Not single child | 2 | |

| Gender | Boys | 1 |

| Girls | 2 | |

| Parents’ education level | Compulsory education | 1 |

| Non compulsory secondary education | 2 | |

| Junior college | 3 | |

| Bachelor degree | 4 | |

| Graduate degree | 5 | |

| Couple relationship | Harmonious | 1 |

| Commonly | 2 | |

| Hostile | 3 | |

| Divorce | 4 | |

| Home environment | Quiet | 1 |

| Commonly | 2 | |

| Noisy | 3 | |

| Age group | 6 ~ 8 | 1 |

| 9 ~ 10 | 2 | |

| 11 ~ 12 | 3 | |

| Different of parents’ education level | F«M | 1 |

| F < M | 2 | |

| F = M | 3 | |

| F > M | 4 | |

| F»M | 5 |

2.3. Statistical analysis

The abnormal values were identified by sorting each choice and cases with missing values were deleted. Frequency of each variable was used to describe the form of the data and contingency coefficient was used to estimate the extent of the relationship between two variables. Statistically significant variables were screened by logistic regression analyses. The multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was used to describe the relationship between each choice. Finally, the proportions of the case and the control in population constructed according to MCA were calculated. All analyses were carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 23.0). Statistical significance was determined as p < .05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. The gender differences in TD

The case group with 549 males (83.18%) and 111 females (16.82%) had a male‐to‐female ratio of 4.94:1 (Table 1). In the control healthy group, there were 309 males (48.20%) and 332 females (51.80%) and the ratio was 0.93:1. Chi‐square test was used for the evaluation of gender differences in two groups χ 2 = 177.14, p < .001. The gender difference in the two groups was related to that in the incidence of TD (Yang et al., 2016), which was similar to that reported in the literature (Albin, 2018).

3.2. Cross frequency and contingency coefficient analysis

The relationships between TD and gender, family structure (C = 0.125, p < .001), home environment (C = 0.097, p = .002), couple relationship (C = 0.184, p < .001), fathers' educational level (C = 0.219, p < .001), and mothers' educational level (C = 0.218, p < .001) are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The relationship of TD and parents' educational level (C = 0.190, p < .001) was weak, with a modest association with gender (C = 0.346, p < .001), as mentioned above that the ratio of males to females was 4.94:1 in the case group and 0.93:1 in the control group. Family structure had a strong association with couple relationship (C = 0.444, p < .001) and harmonious couples were more inclined to build nuclear families and unite families. The level of education was an important reference at the time of mate selection, as suggested in the research that there was a high degree of correlation between parents' educational attainment (C = 0.664, p < .001). Most parents had a comparable level of education. Compared with women, men were more likely to accept female partners with lower level of education than theirs shown in cell frequency in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Crosstab of each variable

| Group | Age group | Family structure | Gender | Home environment | The noly child or not | Couple relationship | Fathers' educatioal level | Mothers' educatioal level | Difference in parents' educational level | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Case | 6 ~ 8 years | 9 ~ 10 years | 11 ~ 12 | Unconventional family | Nuclear family | Unite family | Boys | Girls | Qquiet | Commonly | Noisy | Single child | Not single child | Harmonious | Commonly | Hostile | Divorce | Compulsory education | Non compulsory secondary education | Junior college | Bachelor degree | Graduate degree | Compulsory education | Non compulsory secondary education | Junior college | Bachelor degree | Graduate degree | F«M | F < M | F = M | F > M | F»M | ||

| Group | Control | 641 | 0 | 356 | 185 | 100 | 11 | 365 | 265 | 309 | 332 | 504 | 19 | 118 | 572 | 69 | 565 | 50 | 5 | 21 | 44 | 215 | 168 | 166 | 48 | 45 | 158 | 221 | 191 | 26 | 32 | 147 | 307 | 137 | 18 |

| Case | 0 | 660 | 364 | 189 | 107 | 21 | 443 | 196 | 549 | 111 | 471 | 41 | 148 | 566 | 94 | 499 | 111 | 31 | 19 | 126 | 154 | 117 | 218 | 45 | 137 | 187 | 149 | 165 | 22 | 12 | 77 | 370 | 157 | 44 | |

| Age group | 6 ~ 8 years | 356 | 364 | 720 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 470 | 234 | 450 | 270 | 541 | 33 | 146 | 634 | 86 | 599 | 80 | 20 | 21 | 100 | 191 | 152 | 226 | 51 | 93 | 191 | 200 | 209 | 27 | 29 | 118 | 383 | 160 | 30 |

| 9 ~ 10 years | 185 | 189 | 0 | 374 | 0 | 12 | 219 | 143 | 255 | 119 | 280 | 20 | 74 | 324 | 50 | 299 | 49 | 12 | 14 | 43 | 121 | 86 | 101 | 23 | 57 | 98 | 121 | 85 | 13 | 10 | 74 | 180 | 88 | 22 | |

| 11 ~ 12 | 100 | 107 | 0 | 0 | 207 | 4 | 119 | 84 | 153 | 54 | 154 | 7 | 46 | 180 | 27 | 166 | 32 | 4 | 5 | 27 | 57 | 47 | 57 | 19 | 32 | 56 | 49 | 62 | 8 | 5 | 32 | 114 | 46 | 10 | |

| Family structure | Unconventional family | 11 | 21 | 16 | 12 | 4 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 6 | 22 | 3 | 7 | 23 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 18 | 1 | 7 | 14 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 12 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 18 | 8 | 1 |

| Nuclear family | 365 | 443 | 470 | 219 | 119 | 0 | 808 | 0 | 549 | 259 | 624 | 39 | 145 | 696 | 112 | 676 | 100 | 24 | 8 | 117 | 202 | 163 | 260 | 66 | 136 | 191 | 201 | 243 | 37 | 38 | 115 | 416 | 195 | 44 | |

| Unite family | 265 | 196 | 234 | 143 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 461 | 283 | 178 | 329 | 18 | 114 | 419 | 42 | 380 | 56 | 11 | 14 | 52 | 160 | 108 | 116 | 25 | 46 | 143 | 157 | 105 | 10 | 5 | 105 | 243 | 91 | 17 | |

| Gender | Boys | 309 | 549 | 450 | 255 | 153 | 26 | 549 | 283 | 858 | 0 | 615 | 53 | 190 | 736 | 122 | 676 | 123 | 34 | 25 | 145 | 235 | 163 | 249 | 66 | 153 | 231 | 219 | 217 | 38 | 23 | 130 | 480 | 184 | 41 |

| Girls | 332 | 111 | 270 | 119 | 54 | 6 | 259 | 178 | 0 | 443 | 360 | 7 | 76 | 402 | 41 | 388 | 38 | 2 | 15 | 25 | 134 | 122 | 135 | 27 | 29 | 114 | 151 | 139 | 10 | 21 | 94 | 197 | 110 | 21 | |

| Home environment | Quiet | 504 | 471 | 541 | 280 | 154 | 22 | 624 | 329 | 615 | 360 | 975 | 0 | 0 | 864 | 111 | 854 | 83 | 15 | 23 | 96 | 280 | 219 | 312 | 68 | 110 | 254 | 281 | 302 | 28 | 36 | 160 | 511 | 220 | 48 |

| Commonly | 19 | 41 | 33 | 20 | 7 | 3 | 39 | 18 | 53 | 7 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 47 | 13 | 34 | 15 | 8 | 3 | 15 | 9 | 16 | 17 | 3 | 15 | 19 | 14 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 27 | 22 | 3 | |

| Noisy | 118 | 148 | 146 | 74 | 46 | 7 | 145 | 114 | 190 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 266 | 227 | 39 | 176 | 63 | 13 | 14 | 59 | 80 | 50 | 55 | 22 | 57 | 72 | 75 | 43 | 19 | 6 | 58 | 139 | 52 | 11 | |

| Single child or not | Single child | 572 | 566 | 634 | 324 | 180 | 23 | 696 | 419 | 736 | 402 | 864 | 47 | 227 | 1,138 | 0 | 944 | 131 | 31 | 32 | 126 | 329 | 253 | 351 | 79 | 124 | 307 | 330 | 333 | 44 | 43 | 213 | 578 | 252 | 52 |

| Not single child | 69 | 94 | 86 | 50 | 27 | 9 | 112 | 42 | 122 | 41 | 111 | 13 | 39 | 0 | 163 | 120 | 30 | 5 | 8 | 44 | 40 | 32 | 33 | 14 | 58 | 38 | 40 | 23 | 4 | 1 | 11 | 99 | 42 | 10 | |

| Couple relationship | Harmonious | 565 | 499 | 599 | 299 | 166 | 8 | 676 | 380 | 676 | 388 | 854 | 34 | 176 | 944 | 120 | 1,064 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 133 | 300 | 241 | 312 | 78 | 136 | 278 | 309 | 308 | 33 | 39 | 190 | 547 | 238 | 50 |

| Commonly | 50 | 111 | 80 | 49 | 32 | 5 | 100 | 56 | 123 | 38 | 83 | 15 | 63 | 131 | 30 | 0 | 161 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 45 | 25 | 51 | 10 | 38 | 43 | 37 | 32 | 11 | 1 | 24 | 89 | 41 | 6 | |

| Hostile | 5 | 31 | 20 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 24 | 11 | 34 | 2 | 15 | 8 | 13 | 31 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 15 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 9 | 5 | |

| Divorce | 21 | 19 | 21 | 14 | 5 | 18 | 8 | 14 | 25 | 15 | 23 | 3 | 14 | 32 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 1 | 18 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 16 | 13 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 23 | 6 | 1 | |

| Fathers' educational level | Compulsory education | 44 | 126 | 100 | 43 | 27 | 1 | 117 | 52 | 145 | 25 | 96 | 15 | 59 | 126 | 44 | 133 | 30 | 6 | 1 | 170 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 114 | 51 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 51 | 114 | 0 | 0 |

| Non compulsory secondary education | 215 | 154 | 191 | 121 | 57 | 7 | 202 | 160 | 235 | 134 | 280 | 9 | 80 | 329 | 40 | 300 | 45 | 6 | 18 | 0 | 369 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 59 | 189 | 88 | 32 | 1 | 33 | 88 | 189 | 59 | 0 | |

| Junior college | 168 | 117 | 152 | 86 | 47 | 14 | 163 | 108 | 163 | 122 | 219 | 16 | 50 | 253 | 32 | 241 | 25 | 7 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 285 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 62 | 148 | 66 | 6 | 6 | 66 | 148 | 62 | 3 | |

| Bachelor degree | 166 | 218 | 226 | 101 | 57 | 8 | 260 | 116 | 249 | 135 | 312 | 17 | 55 | 351 | 33 | 312 | 51 | 15 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 384 | 0 | 6 | 36 | 119 | 204 | 19 | 0 | 19 | 204 | 119 | 42 | |

| Graduate degree | 48 | 45 | 51 | 23 | 19 | 2 | 66 | 25 | 66 | 27 | 68 | 3 | 22 | 79 | 14 | 78 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 93 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 54 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 54 | 17 | |

| Mothers' educational level | Compulsory education | 45 | 137 | 93 | 57 | 32 | 0 | 136 | 46 | 153 | 29 | 110 | 15 | 57 | 124 | 58 | 136 | 38 | 8 | 0 | 114 | 59 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 182 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 114 | 59 | 9 |

| Non compulsory secondary education | 158 | 187 | 191 | 98 | 56 | 11 | 191 | 143 | 231 | 114 | 254 | 19 | 72 | 307 | 38 | 278 | 43 | 8 | 16 | 51 | 189 | 62 | 36 | 7 | 0 | 345 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 51 | 189 | 62 | 43 | |

| Junior college | 221 | 149 | 200 | 121 | 49 | 12 | 201 | 157 | 219 | 151 | 281 | 14 | 75 | 330 | 40 | 309 | 37 | 11 | 13 | 5 | 88 | 148 | 119 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 370 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 88 | 148 | 119 | 10 | |

| Bachelor degree | 191 | 165 | 209 | 85 | 62 | 8 | 243 | 105 | 217 | 139 | 302 | 11 | 43 | 333 | 23 | 308 | 32 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 32 | 66 | 204 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 356 | 0 | 32 | 66 | 204 | 54 | 0 | |

| Graduate degree | 26 | 22 | 27 | 13 | 8 | 1 | 37 | 10 | 38 | 10 | 28 | 1 | 19 | 44 | 4 | 33 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 19 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 7 | 19 | 22 | 0 | 0 | |

| Difference in parents' educational level | F«M | 32 | 12 | 29 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 38 | 5 | 23 | 21 | 36 | 2 | 6 | 43 | 1 | 39 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 33 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 32 | 7 | 44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F < M | 147 | 77 | 118 | 74 | 32 | 4 | 115 | 105 | 130 | 94 | 160 | 6 | 58 | 213 | 11 | 190 | 24 | 2 | 8 | 51 | 88 | 66 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 51 | 88 | 66 | 19 | 0 | 224 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| F = M | 307 | 370 | 383 | 180 | 114 | 18 | 416 | 243 | 480 | 197 | 511 | 27 | 139 | 578 | 99 | 547 | 89 | 18 | 23 | 114 | 189 | 148 | 204 | 22 | 114 | 189 | 148 | 204 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 677 | 0 | 0 | |

| F > M | 137 | 157 | 160 | 88 | 46 | 8 | 195 | 91 | 184 | 110 | 220 | 22 | 52 | 252 | 42 | 238 | 41 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 59 | 62 | 119 | 54 | 59 | 62 | 119 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 294 | 0 | |

| F»M | 18 | 44 | 30 | 22 | 10 | 1 | 44 | 17 | 41 | 21 | 48 | 3 | 11 | 52 | 10 | 50 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 42 | 17 | 9 | 43 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 62 | |

TABLE 3.

Contingency coefficient between variables

| Group | Age group | Family structure | Gender | Home environment | The noly child or not | Couple relationship | Fathers' educatioal level | Mothers' educatioal level | Difference in parents' educational level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | — |

C = 0.008 p = .956 |

C = 0.125 p < .001 |

C = 0.346 p < .001 |

C = 0.097 p = .002 |

C = 0.052 p = .058 |

C = 0.184 p < .001 |

C = 0.219 p < .001 |

C = 0.218 p < .001 |

C = 0.190 p < .001 |

| Age group |

C = 0.008 p = .956 |

— |

C = 0.078 p = .091 |

C = 0.089 p = .005 |

C = 0.034 p = .819 |

C = 0.020 p = .773 |

C = 0.060 p = .576 |

C = 0.079 p = .414 |

C = 0.085 p = .310 |

C = 0.076 p = .486 |

| Family structure |

C = 0.125 p < .001 |

C = 0.078 p = .091 |

— |

C = 0.083 p = .011 |

C = 0.089 p = .036 |

C = 0.101 p = .001 |

C = 0.444 p < .001 |

C = 0.155 p < .001 |

C = 0.175 p < .001 |

C = 0.148 p < .001 |

| Gender |

C = 0.346 p < .001 |

C = 0.089 p = .005 |

C = 0.083 p = .011 |

— |

C = 0.125 p < .001 |

C = 0.071 p = .010 |

C = 0.134 p < .001 |

C = 0.173 p < .001 |

C = 0.177 p < .001 |

C = 0.119 p = .001 |

| Home environment |

C = 0.097 p = .002 |

C = 0.034 p = .819 |

C = 0.089 p = .036 |

C = 0.125 p < .001 |

— |

C = 0.072 p = .033 |

C = 0.272 p < .001 |

C = 0.187 p < .001 |

C = 0.196 p < .001 |

C = 0.103 p = .083 |

| Single child or not |

C = 0.052 p = .058 |

C = 0.020 p = .773 |

C = 0.101 p = .001 |

C = 0.071 p = .010 |

C = 0.072 p = .033 |

— |

C = 0.083 p = .028 |

C = 0.162 p < .001 |

C = 0.236 p < .001 |

C = 0.124 p < .001 |

| Couple relationship |

C = 0.184 p < .001 |

C = 0.060 p = .576 |

C = 0.444 p < .001 |

C = 0.134 p < .001 |

C = 0.272 p < .001 |

C = 0.083 p = .028 |

— |

C = 0.133 p = .025 |

C = 0.163 p < .001 |

C = 0.117 p = .117 |

| Fathers' educational level |

C = 0.219 p < .001 |

C = 0.079 p = .414 |

C = 0.155 p < .001 |

C = 0.173 p < .001 |

C = 0.187 p < .001 |

C = 0.162 p < .001 |

C = 0.133 p = .025 |

— |

C = 0.664 p < .001 |

C = 0.468 p < .001 |

| Mothers' educational level |

C = 0.218 p < .001 |

C = 0.085 p = .310 |

C = 0.175 p < .001 |

C = 0.177 p < .001 |

C = 0.196 p < .001 |

C = 0.236 p < .001 |

C = 0.163 p < .001 |

C = 0.664 p < .001 |

— |

C = 0.406 p < .001 |

| Difference in parents' educational level |

C = 0.190 p < .001 |

C = 0.076 p = .486 |

C = 0.148 p < .001 |

C = 0.119 p = .001 |

C = 0.103 p = .083 |

C = 0.124 p < .001 |

C = 0.117 p = .117 |

C = 0.468 p < .001 |

C = 0.406 p < .001 |

— |

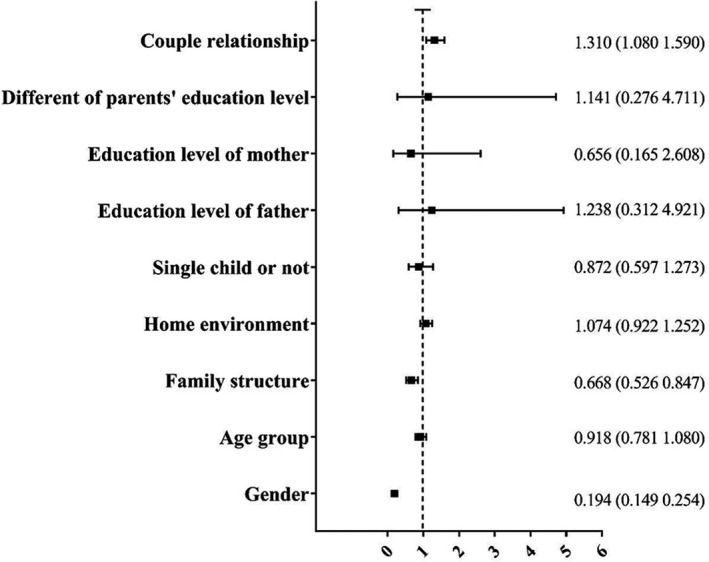

3.3. Regression of binary logistic analysis

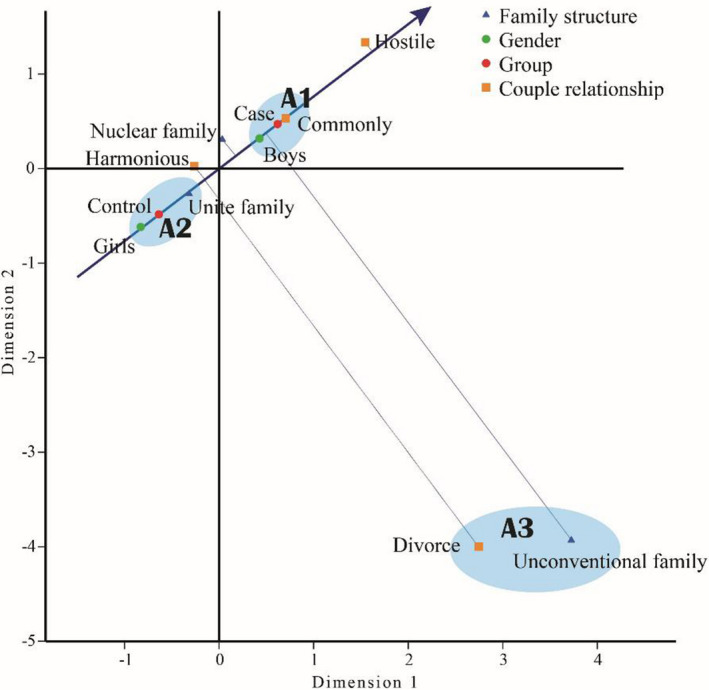

Regression of binary logistic analyses (BLA) was used to analyze the association between ‘Group’ and other variables including gender and age. According to the results (Table 4; Figure 2), we found that the gender, family structure, and couple relationship could influence the onset of tic with statistically significant (p < .01). Boys had a higher risk of TD than girls (Exp B = 0.194, p < .001, 95% CI = 0.149–0.254). Compared with unite family, children living in nuclear families were more susceptible to the illness (Exp B = 0.668, p = .001, 95% CI = 0.526–0.847). The harmonious relationship between parents was a significant protective factor, making children away from the tic (Exp B = 1.310, p = .006, 95% CI = 1.080–1.590). The relationship between group, family structure, family environment, and gender was the inertia 0.752 analyzed by MCA(Figure 3).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of variables between the case and the control

| Factors description | Group | wald χ 2 | Exp B | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Case | ||||||

| Gender | Boys | 309 | 549 | 144.193 | 0.194 | <.001 | 0.149 ~ 0.254 |

| Girls | 332 | 111 | |||||

| Age group | 6 ~ 7 | 356 | 364 | 1.069 | 0.918 | .301 | 0.781 ~ 1.080 |

| 8 ~ 9 | 185 | 189 | |||||

| 10 ~ 12 | 100 | 107 | |||||

| Family structure | Unconventional family | 11 | 21 | 11.098 | 0.668 | .001 | 0.526 ~ 0.847 |

| Nuclear family | 365 | 443 | |||||

| Unite family | 265 | 196 | |||||

| Home environment | Quiet | 504 | 471 | 0.845 | 1.074 | .358 | 0.922 ~ 1.252 |

| Commonly | 19 | 41 | |||||

| Noisy | 118 | 148 | |||||

| Single child or not | Single child | 572 | 566 | 0.503 | 0.872 | .478 | 0.597 ~ 1.273 |

| Not single child | 69 | 94 | |||||

| Education level of father | Compulsory education | 44 | 126 | 0.092 | 1.238 | .761 | 0.312 ~ 4.921 |

| Non compulsory secondary education | 215 | 154 | |||||

| Junior college | 168 | 117 | |||||

| Bachelor degree | 166 | 218 | |||||

| Graduate degree | 48 | 45 | |||||

| Education level of mother | Compulsory education | 45 | 137 | 0.358 | 0.656 | .549 | 0.165 ~ 2.608 |

| Non compulsory secondary education | 158 | 187 | |||||

| Junior college | 221 | 149 | |||||

| Bachelor degree | 191 | 165 | |||||

| Graduate degree | 26 | 22 | |||||

| Different of parents' education level | F«M | 32 | 12 | 0.033 | 1.141 | .855 | 0.276 ~ 4.711 |

| F < M | 147 | 77 | |||||

| F = M | 307 | 370 | |||||

| F > M | 137 | 157 | |||||

| F»M | 18 | 44 | |||||

| Couple relationship | Harmonious | 565 | 499 | 7.478 | 1.310 | .006 | 1.080 ~ 1.590 |

| Commonly | 50 | 111 | |||||

| Hostile | 5 | 31 | |||||

| Divorce | 21 | 19 | |||||

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of logistic analyses

FIGURE 3.

Unite plot of category points

3.4. Analysis of a ray and its’ reverse extension from the origin to the case and vertical lines from other points to the line

A ray and its’ reverse extension from the origin to the case and vertical lines from other points to the line were made. The distance between the origin and the feet corresponds to relationship between the factors and the occurrence of TD. The negative sign represents the protective factor and the positive sign represents the risk factor (Figure 3; Table 5). We found that the case group was more likely to include boys who lived in the common family environment (A1), while the control group was more likely to be girls in a united family (A2). In addition, the divorce of spouses was an important factor leading to abnormal family structure (A3). The hostile relationship between parents would greatly increase the risk of children suffering from TD. All the conclusions above can be considered statistically significant because the A1, A2, and A3 regions distributed in different quadrants. The distance, common and hostile condition in couple relationship, unusual and nuclear family structure, could increase probability of TD, especially boys.

TABLE 5.

Coordinate of each category

| Category | Coordinate of category | Coordinate of foot point | Distance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dim 1 | Dim 2 | Dim 1 | Dim 2 | ||

| Group | |||||

| Control | −0.637 | −0.484 | −0.637 | −0.484 | −0.800 |

| Case | 0.619 | 0.470 | 0.619 | 0.470 | 0.777 |

| Family structure | |||||

| Unconventional family | 3.725 | −3.933 | 0.469 | 0.356 | 0.589 |

| Nuclear family | 0.033 | 0.309 | 0.170 | 0.129 | 0.213 |

| Unite family | −0.316 | −0.268 | −0.330 | −0.250 | −0.414 |

| Couple relationship | |||||

| Harmonious | −0.262 | 0.025 | −0.154 | −0.117 | −0.194 |

| Commonly | 0.705 | 0.530 | 0.703 | 0.533 | 0.882 |

| Hostile | 1.545 | 1.336 | 1.624 | 1.232 | 2.038 |

| Divorce | 2.748 | −4.000 | −0.183 | −0.139 | −0.229 |

| Gender | |||||

| Boys | 0.428 | 0.319 | 0.425 | 0.323 | 0.534 |

| Girls | −0.829 | −0.617 | −0.823 | −0.625 | −1.033 |

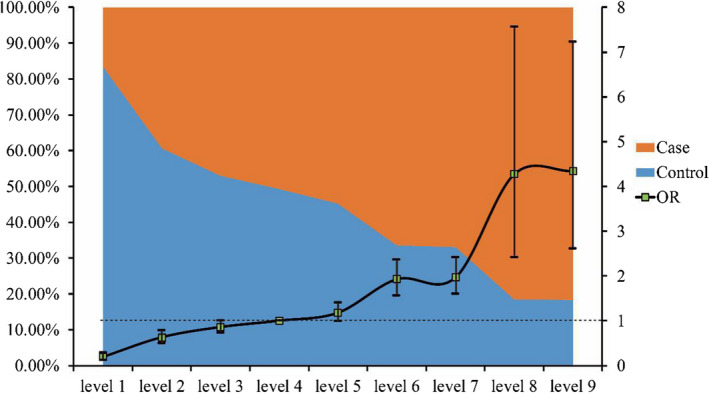

3.5. The OR value increased with the number and level of risk factors

We selected the population that meet all protective factors from the database and remove the protections in order according to the distances in Table 5, and then increase the risk factor conditions. The proportions of the case and the control in those population constructed was calculated (Figure 4). Levels from 1 to 9 represent the increase in the number of risk factors and their levels. Level 1 present all protective factors and Level 9 present all risk factors. We compared all observations as controls with the constructed population and calculated the OR value (Table 6). As the number and level of risk factors increased, the proportion of patients with TD in the selected population and OR value gradually increases (Figure 3).

FIGURE 4.

The risk of superimposed factors

TABLE 6.

Proportions of case in constructed population

| Level | Family structure | Couple relationship | Gender | Case (%) | Control (%) | N | OR | χ 2 | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| 1 | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | 16.46 | 83.54 | 164 | 0.191 (0.125 ~ 0.293) | 68.670 | <.0001 |

| 2 | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | 39.34 | 60.66 | 394 | 0.630 (0.501 ~ 0.792) | 15.717 | <.0001 |

| 3 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | 46.92 | 53.08 | 1,104 | 0.859 (0.731 ~ 1.008) | 3.469 | .063 |

| 4 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 50.73 | 49.27 | 1,301 | — | — | — |

| 5 | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 54.83 | 45.17 | 808 | 1.179 (0.988 ~ 1.406) | 3.353 | .067 |

| 6 | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | 66.48 | 33.52 | 549 | 1.927 (1.565 ~ 2.372) | 38.783 | <.0001 |

| 7 | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | 66.96 | 33.04 | 575 | 1.968 (1.603 ~ 2.416) | 42.550 | <.0001 |

| 8 | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | 81.48 | 18.52 | 81 | 4.273 (2.414 ~ 7.564) | 28.917 | <.0001 |

| 9 | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | 81.73 | 18.27 | 104 | 4.345 (2.611 ~ 7.229) | 37.156 | <.0001 |

Family structure: 1 = Unconventional family, 2 = Nuclear family, 3 = Unite family; Couple relationship: 1 = Harmonious, 2 = Commonly, 3 = Hostile, 4 = Divorce; Gender: 1 = Boys, 2 = Girls; ●: The category was included in the population.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that gender, couple relationship, and family structure could play important roles in TD. Boys, unusual or unclear families and bad couple relationship are risks for TD. What's more, we constructed populations according to the risks and compared them with the population included all categories (all data) to calculated the OR value. With the gradual increase in risk, the OR value gradually increases, which gives us significant advice for the prevention of tics and primary care (Mills & Hedderly, 2014; Steeves et al., 2012; Verdellen, van de Griendt, Hartmann, & Murphy, 2011).

It has been reported that the range of male preponderance varies between 1.6 and 10:1 (Tanner & Goldman, 1997), and is even more pronounced in youth 5.2:1 (Freeman et al., 2000). Existing evidence demonstrates intriguing ratios of 3:1 between males and females in TD (Robertson, 2012), explaining the imbalance of gender in the study. Authors suggest that the prenatal androgen related masculinization might account for this difference (Peterson et al., 1992). The others attributed that to the increased masculine play preferences in both males and females (Alexander & Peterson, 2004). From the Figure 2, we found that gender was related to the couple relationship and family structure. Parents with girls could be more likely to construct unite families while boys’ parents tend to construct the nuclear families. Another interesting finding is that boys could be related to the inharmonious couple relationship. According to the results, gender difference could impact on the family factors which can affect the development of TD.

Family‐related environmental factors may play a role in the development or exacerbation of TDs (Hong et al., 2013). Starkweather and Keith (2018) thought it might account for more variation in some children's outcomes than expected, relative to genetics. As professor Waldinger and Schulz (2016) concluded, the warmth of family environment in childhood predicts the quality of health in the long reach of nurturing family environments. Couple relationship influence not only physical health but also the mental health of children. Tai Young Park (2013) reported that marital conflict became the primary factor of the child's TD and the family therapist usually tried to solve the TD problem based on MRI's communication theory and Bowen's family systems theory. Storch et al. (2017) have studied family accommodation in children and adolescents with TD. They found that accommodation was not associated with tic severity, but was related to higher levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, externalizing symptoms, aggression, and rule breaking behaviors (Storch et al., 2017). Other researches’ results suggest that the emotional symptoms, such as anxiety (Coffey et al., 2000), are more likely to drive the TS. In this study, family structure and couple relationship were determined as important factors for TD.

Nuclear family, stem family, and unite family are common structure in China while the others considered as the unusual. On the other side, the stem and unite family could be thought as the combination of nuclear families that should be divided into the same category. Nuclear family could be dangerous for children to develop into TD. The change in family structure may impact on family members’ mental health, and the internal quality of role (family function) might be the key factor (Cheng et al., 2017). The influence of family structure on children has been reported. (Troxel, Lee, Hall, & Matthews, 2014). The order of family structure related to TD was unconventional family, nuclear family, and unite family.

Mental health assessment would consider various contextual factors, from the individual to the relational and environmental. The parental couple is an important influence factor that related to child and adolescent mental health (Karamat, 2015). We found that divorced parents had the same protective effect as the harmonious while the hostile could be risk for children. Kelly (1998) thought that children living in marriages with frequent and intense conflict are significantly more likely to have substantial mental problems before parental divorce and had a bad relationship with parents (Kelly, 1998). These findings suggest that the deleterious effects of divorce have been overstated, with insufficient attention paid in the clinical and research literature of the damaging effects of highly troubled marriages on children's adjustment.

Taken together, couple relationship and family structure could influence not only physical health but also the mental health of the children. Unconventional and nuclear family, as well as hostile parents were risk for children to develop TD. The superimposition of those factors can increase the risk of TD. This study suggests that parents should try to construct a harmonious couple relationship for the health of their children.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Pengcheng Zhu: Study concepts; Min Wu: Study design; Pengcheng Zhu: Definition of intellectual content; Pengcheng Zhu: Literature research; Xiaoyi Ji: Clinical studies; Xiaoyi Ji: Data acquisition; Pengcheng Zhu, Pinxian Huang: Data analysis; Pengcheng Zhu, Pinxian Huang: Statistical analysis; Pengcheng Zhu: Manuscript preparation; Xin Zhao: Manuscript editing; Min Wu: Manuscript review.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None.

CONFLICT‐OF‐INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Zhu P, Wu M, Huang P, Zhao X, Ji X. Children from nuclear families with bad parental relationship could develop tic symptoms. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8:e1286 10.1002/mgg3.1286

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Albin, R. L. (2018). Tourette syndrome: A disorder of the social decision‐making network. Brain, 141(2), 332–347. 10.1093/brain/awx204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, G. M. , & Peterson, B. S. (2004). Testing the prenatal hormone hypothesis of tic‐related disorders: Gender identity and gender role behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 16(2), 407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM‐5) (Vol. 5, 5th ed., p. 81). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine, E. F. , Adams, H. R. , Bitsko, R. H. , van Wijngaarden, E. , Claussen, A. H. , Thatcher, A. , … Mink, J. W. (2017). Design of a multisite study assessing the impact of tic disorders on individuals, families, and communities. Pediatric Neurology, 68, 49–58.e3. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2016.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cath, D. C. , Hedderly, T. , Ludolph, A. G. , Stern, J. S. , Murphy, T. , Hartmann, A. , … Rizzo, R. (2011). ESSTS guidelines group. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part I: Assessment. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(4), 155–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y. , Zhang, L. , Wang, F. , Zhang, P. , Ye, B. , & Liang, Y. (2017). The effects of family structure and function on mental health during China's transition: A cross‐sectional analysis. BMC Family Practice, 18(1), 59 10.1186/s12875-017-0630-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claussen, A. H. , Bitsko, R. H. , Holbrook, J. R. , Bloomfield, J. , & Giordano, K. (2018). Impact of Tourette syndrome on school measures in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 39(4), 335–342. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, B. J. , Biederman, J. , Smoller, J. W. , Geller, D. A. , Sarin, P. , Schwartz, S. , & Kim, G. S. (2000). Anxiety disorders and tic severity in juveniles with Tourette's disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(5), 562–568. 10.1097/00004583-200005000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, N. , & Cavanna, A. E. (2013). The effectiveness of habit reversal therapy in the treatment of Tourette syndrome and other chronic tic disorders: A systematic review. Functional Neurology, 28(1), 7–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Education Law of the People's Republic of China . (2015). Retrieved from http://www.moe.edu.cn/s78/A02/zfs__left/s5911/moe_619/201512/t20151228_226193.html

- Evans, G. , Wittkowski, A. , Butler, H. , Hedderly, T. , & Bunton, P. (2015). Parenting interventions in tic disorders: An exploration of parents' perspectives. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41(3), 384–396. 10.1111/cch.12212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G. A. , Wittkowski, A. , Butler, H. , Hedderly, T. , & Bunton, P. (2016). Parenting interventions for children with tic disorders: Professionals' Perspectives. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 1594–1604. 10.1007/s10826-015-0317-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R. D. , Fast, D. K. , Burd, L. , Kerbeshian, J. , Robertson, M. M. , & Sandor, P. (2000). An international perspective on Tourette syndrome: Selected findings from 3,500 individuals in 22 countries. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 42(7), 436–447. 10.1017/S0012162200000839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goussé, V. , Czernecki, V. , Denis, P. , Stilgenbauer, J. L. , Deniau, E. , & Hartmann, A. (2016). Impact of perceived stress, anxiety‐depression and social support on coping strategies of parents having a child with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 30(1), 109–113. 10.1016/j.apnu.2015.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett, M. (2015). Tourette syndrome: Update. Brain and Development, 37(7), 651–655. 10.1016/j.braindev.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S. B. , Kim, J. W. , Shin, M. S. , Hong, Y. C. , Park, E. J. , Kim, B. N. , … Cho, S. C. (2013). Impact of family environment on the development of tic disorders: Epidemiologic evidence for an association. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 25(1), 50–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalenques, I. , Auclair, C. , Morand, D. , Legrand, G. , Marcheix, M. , Ramanoel, C. , … Derost, P. H. (2017). Syndrome de Gilles de La Tourette Study Group, Derost P. Health‐related quality of life, anxiety and depression in parents of adolescents with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: A controlled study. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 26(5), 603–617. 10.1007/s00787-016-0923-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadam, P. D. , & Chuan, H. H. (2016). Erratum to: Rectocutaneous fistula with transmigration of the suture: A rare delayed complication of vault fixation with the sacrospinous ligament. International Urogynecology Journal, 27(3), 505 10.1007/s00192-016-2952-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamat, A. R. (2015). The parental couple relationship in child and adolescent mental health. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 20(2), 169–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J. B. (1998). Marital conflict, divorce, and children's adjustment. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 7(2), 259–271. 10.1016/S1056-4993(18)30240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight, T. , Steeves, T. , Day, L. , Lowerison, M. , Jette, N. , & Pringsheim, T. (2012). Prevalence of tic disorders: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Pediatric Neurology, 47(2), 77–90. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills, S. , & Hedderly, T. (2014). A guide to childhood motor stereotypies, tic disorders and the tourette spectrum for the primary care practitioner. Ulster Medical Journal, 83(1), 22–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, B. S. , Leckman, J. F. , Scahill, L. , Naftolin, F. , Keefe, D. , Charest, N. J. , & Cohen, D. J. (1992). Steroid hormones and CNS sexual dimorphisms modulate symptom expression in Tourette's syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 17(6), 553–563. 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90015-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, M. M. (2012). The Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: The current status. Archives of Disease in Childhood ‐ Education & Practice Edition, 97(5), 166–175. 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessner, V. , Plessen, K. J. , Rothenberger, A. , Ludolph, A. G. , Rizzo, R. , Skov, L. , … ESSTS Guidelines Group . (2011). European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part II: Pharmacological treatment. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(4), 173–196. 10.1007/s00787-011-0163-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlander, M. , Schwarz, O. , Rothenberger, A. , & Roessner, V. (2011). Tic disorders: Administrative prevalence and co‐occurrence with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a German community sample. European Psychiatry, 26(6), 370–374. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkweather, K. E. , & Keith, M. H. (2018). Estimating impacts of the nuclear family and heritability of nutritional outcomes in a boat‐dwelling community. American Journal of Human Biology, 30(3), e23105 10.1002/ajhb.23105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeves, T. , McKinlay, B. D. , Gorman, D. , Billinghurst, L. , Day, L. , Carroll, A. , … Pringsheim, T. (2012). Canadian guidelines for the evidence‐based treatment of tic disorders: Behavioural therapy, deep brain stimulation, and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(3), 144–151. 10.1177/070674371205700303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch, E. A. , Johnco, C. , McGuire, J. F. , Wu, M. S. , McBride, N. M. , Lewin, A. B. , & Murphy, T. K. (2017). An initial study of family accommodation in children and adolescents with chronic tic disorders. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 26(1), 99–109. 10.1007/s00787-016-0879-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagwerker, G. F. , & Walitza, S. (2016). Tic disorders and Tourette syndrome: Current concepts of etiology and treatment in children and adolescents. Neuropediatrics., 47(2), 84–96. 10.1055/s-0035-1570492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai Young Park, J. H. Y. (2013). A case study on family therapy for parents with a daughter suffering from multiple tic disorder. Journal of Korean Home Management Association, 31(5), 47–63. 10.7466/JKHMA.2013.31.5.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, C. M. , & Goldman, S. M. (1997). Epidemiology of Tourette syndrome. Neurologic Clinics, 15(2), 395–402. 10.1016/S0733-8619(05)70320-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel, W. M. , Lee, L. , Hall, M. , & Matthews, K. A. (2014). Single‐parent family structure and sleep problems in black and white adolescents. Sleep Medicine, 15(2), 255–261. 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdellen, C. , van de Griendt, J. , Hartmann, A. , & Murphy, T. (2011). European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part III: Behavioural and psychosocial interventions. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(4), 197–207. 10.1007/s00787-011-0167-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger, R. J. , & Schulz, M. S. (2016). The long reach of nurturing family environments: Links with midlife emotion‐regulatory styles and late‐life security in intimate relationships. Psychological Science, 27(11), 1443–1450. 10.1177/0956797616661556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C. , Zhang, L. , Zhu, P. , Zhu, C. , & Guo, Q. (2016). The prevalence of tic disorders for children in China: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Medicine (Baltimore), 95(30), e4354 10.1097/MD.0000000000004354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. , Hirsch, L. , Osland, S. , Martino, D. , Jette, N. , Roberts, J. I. , & Pringsheim, T. (2017). Health status, health related behaviours and chronic health indicators in people with Tourette syndrome: A Canadian population‐based study. Psychiatry Research, 250, 228–233. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.