Abstract

Currently, breast cancer is becoming a major public health problem for developing countries. In Ethiopia, breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer among women, and constitutes a major public health concern. Hence, this study was aimed to determine the incidence and predictor of recurrence among breast cancer clients at Black Lion Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia, in 2018. We analyzed 513 patients out of 835 women breast cancer patients treated at Black Lion Specialized Hospital. Recurrent-free survival was determined using the Kaplan–Meier method, with comparisons between groups through the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify predictors of recurrence among breast cancer clients. The incidence rate of recurrence among breast cancer was 6.5% per (95% CI = 6.49-12.47) follow-up. The median recurrent-free survival time was 60.33 months (95% CI = 54.46-62.30). Predictors of recurrence were negative estrogen receptor (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.53-7.62), high histologic grade (HR = 2.8, 95% CI = 1.14-10.31), positive lymph node status (HR = 2.6, 95% CI = 1.14-10.31), clinical staging III (HR = 2.5, 95% CI = 1.26-9.42), and involved deep surgical margin (HR = 3.6, 95% CI = 2.14-8.61). This research showed that incidence of recurrence was high. Advanced clinical stage, positive nodal status, high histologic grade, negative estrogen receptor, and involved deep surgical margin were associated with higher recurrence rates. In contrast, hormonal therapy has a great role in decreasing the development of recurrence.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, Predictors, Recurrence, Follow-up, Ethiopia

INTRODUCTION

Globally, breast cancer is the most common type of cancer and the leading cause of cancer-associated mortality among women [1]. Worldwide, breast cancer ranks as the fifth cause of death among all forms of cancers, and is the second most common cancer next to lung cancer [2,3]. Adjuvant systemic therapies, including chemotherapy, hormonal treatment, and immunotherapy have been proven to reduce disease recurrence and prolong survival [4].

In Ethiopia, breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer among women, and constitutes a major public health concern which accounts for about 30% of all cancers [5]. Several studies have previously reported that cases with high grade tumor, large tumor size, axillary nodal involvement, and negative estrogen and progesterone receptors had a higher risk of recurrence [6-10]. Other studies have shown that for contralateral breast cancer, the annual incidence rate of recurrence ranges from 0.2% to 0.7% and for the ipsilateral breast tumor, recurrence was 0.4% to 1.1% [11].

A retrospective observational study indicates that median time to recurrence after primary surgical resection, was 3 years in the clinician detection and 2 years for imaging detection [12]. Similarly the annual hazard of recurrence peaks in the second year after diagnosis, but remains at 2% to 5% in years 5 to 20 and the sites of recurrence depend on the breast cancer molecular subtype [13-15]. Furthermore, the overall annual cumulative incidence of recurrence among breast cancer patients within six years was 3.3% in Australia [9], 6% in Canada [16], and 5.1% in South Korea [17].

Despite the extensive knowledge about the incidence of recurrence among breast cancer in the western world, breast cancer recurrence data is not widely available in Ethiopia. Hence, the current study is important for patients, clinicians and health service planners to know the risk of recurrence after breast cancer surgery. In addition, to our knowledge, there was no study which examined the magnitude of recurrence in the study area. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to determine the incidence of recurrence and to identify predictors of recurrence among breast cancer clients after the primary surgery at Black Lion Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, setting and population

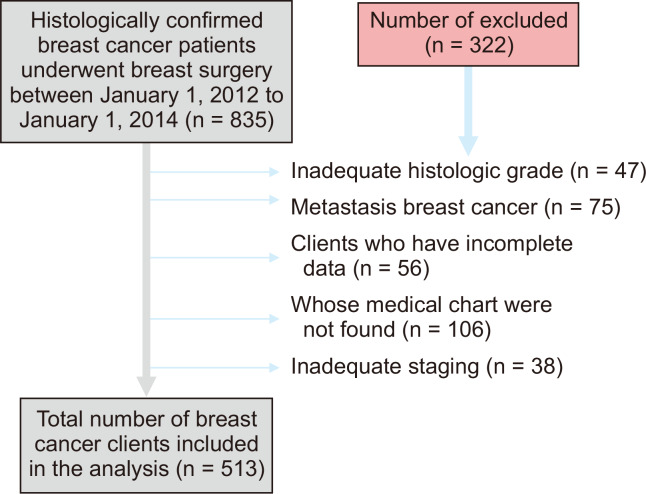

A facility-based retrospective follow-up study with survival analysis was conducted at Black Lion Specialized Hospital from March 1 to April 28, 2018. The study population was all patients with breast cancer who undertook treatment in the Black Lion Specialized Hospital from January 1, 2012 to January 1, 2014 until January 1, 2018 and who fulfilled the inclusion criteria of the study. Women who had not previous diagnosis of breast cancer, patients who had done surgery at other hospitals and subsequently referred to the Black Lion Specialized Hospital for further treatment, and patients who were newly treated and enrolled in the required time (i.e., 1st January 2012 to January 1st 2014) were included. On the other hand, women whose medical charts were not found, and those inadequate assessment of histological grade, incomplete document and with inadequate staging were excluded (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram showing the sampling procedure of breast cancer patients those underwent breast surgery at Black Lion Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018.

Sample size and covariates

In deciding the sample size for this study, all breast cancer patients who attended the oncology unit between January 1, 2012 to January 1, 2014 and fulfilled the inclusion criteria of the study were considered. During the study period, about 835 clients were underwent breast surgery. After extensive evaluation of study participants by data collectors from the hospital charts, about 513 samples were finally included. The incidence of recurrence among breast cancer clients was the outcome variable and estrogen receptor status, and the histological grading was by the Bloom-Richardson grading system that combined scores for nuclear grade, tubule formation and mitotic rate [18]. The tumor size, axillary nodal involvement, treatment types, menopausal status, history of comorbidities [19], body mass index and information on tumor size (T) and nodal status (N) were used to derive stage by the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system AJCC (seventh edition): stage 1 (TxN0); stage 2 (T0N1, T1N1, T2N0, T2N1, or T3N0); and stage 3 (TxN2, T3N1, T4Nx, or TxN3) [20] were the independent variables.

Data collection tool and quality

A data abstraction format develop from different literature was used to collect data and necessary information from patients’ medical files. The starting point for retrospective follow-up was the time from the first date of breast cancer surgery to the date of recurrence, the date of death, the date of lost follow-up (censored), or end of the study (until January 1, 2018), whichever comes first. Their recurrence status was identified from clinical, imaging studies and biopsy detection was confirmed by reviewing medical registration at the hospital. In addition, recurrent-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time between the primary breast cancer surgery to the date of local or distant recurrence. To ensure the quality of the data, training on record review was given to data collectors and supervisors for 1 day before actual data collection and trained guide was prepared to facilitate the training. Pre-test was done on registrations that were not included in the final study for consistency of understanding the review tools and completeness of data items. The collected data were reviewed and checked for completeness every day and before data entry. All completed data collection forms were examined for completeness and consistency during data management, storage, cleaning and analysis. Three oncology nurses, who were working on the oncology unit, collected the data. The principal investigator of the study was controlling the overall activity.

Data analysis and management

Data were coded, cleaned, entered, and edited using EPI-data ver. 4.2 (https://www.epidata.dk/download.php) and exported to STATA ver. 14 statistical software (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) for analysis. Descriptive statistics was used to investigate the characteristics of the cohort. The incidence density rate was calculated for the entire study period. Kaplan–Meier curves were plotted and compared using log rank tests.

Bivariable proportional Cox regression was first fitted and those independent variables, which became significant on the bivariable regression having the P-value ≤ 0.25 level of significance, were included in the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model. Hazard ratios (HRs), with 95% CIs were used as to determine the independent effect of each explanatory variable on time to recurrence after surgery of breast cancer. Cox-proportional hazard model assumption was checked using the schoenfeld residual test and all variables showed a P-value > 0.10, which fulfilled the assumption. Confounding and effect modification was checked by looking at regression coefficient change if greater than or equal to 15% and multi-collinearity was checked using the variance inflation factor and value of < 10 was used as a cutoff point, indicating no colinearity. Lastly, the P-value of less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for our study was obtained from Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of Addis Ababa University College of Health Science (IRB protocol: aau/chs/ahnsg11/2018). Then, permission letter has been obtained from Black Lion Specialized Hospital, adult oncology unit. The study was conducted without individual informed consent as the study relied on retrospective data collected as part of routine patient care. To keep the confidentiality all collected data were coded and locked in a separate room before entered into the computer. After entered to the computer the data were locked by password, names and unique numbers were not included in the data collection format, and the data were not disclosed to any person other than principal investigator.

RESULTS

Description of the study cohort

A total of 513 study participants were included in this study. The mean age at diagnosis was 44.32 ± 15.56 years. Of the 513 patients examined, 362 (70.6%) were married; 363 women (70.8%) were premenopausal (age less than 50 years old); 172 cases (33.5%) had comorbidity at the time of diagnosis. Three hundred one participants (58.7%) were living in urban areas.

Baseline clinicopathological and treatment characteristics of study subjects

Two hundred forty six histology cases (48.0%) were moderately differentiated; and 318 cases (62.0%) were AJCC clinical stage III. Invasive ductal carcinoma was the predominant, 359 cases of histology type (70.0%). One hundred thirteen cases (22.0%) had a tumor size less than or equal to 2.5 cm; about 321 cases (62.6%) of the study participants were receiving hormone therapy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline clinic pathological characteristics of breast cancer patients at Black Lion Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | < 18.5 | 8 | 1.6 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 338 | 65.9 | |

| 25.0-29.9 | 147 | 28.7 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 20 | 3.9 | |

| Histology grade | Grade I | 73 | 14.2 |

| Grade II | 246 | 48.0 | |

| Grade III | 194 | 37.8 | |

| Stage of breast cancer | I | 28 | 5.5 |

| II | 167 | 32.6 | |

| III | 318 | 62.0 | |

| Histology type | Lobular | 129 | 25.1 |

| Invasive ductal | 359 | 70.0 | |

| Others | 25 | 4.9 | |

| Surgical margin | Free | 347 | 67.6 |

| Involved | 166 | 32.4 | |

| Axillary nodal involvement | Positive | 363 | 70.8 |

| Negative | 150 | 29.2 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤ 2.5 | 113 | 22.0 |

| 2.5-5.0 | 177 | 34.5 | |

| > 5.0 | 223 | 43.5 | |

| No. of positive node | < 2 | 123 | 33.8 |

| ≥ 2 | 240 | 66.1 | |

| Estrogen receptor | Positive | 271 | 52.8 |

| Negative | 222 | 43.3 | |

| Missing | 20 | 3.9 | |

| Type of surgery | MRM | 447 | 87.1 |

| BCS | 66 | 12.9 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | No | 117 | 22.8 |

| Yes | 396 | 77.2 | |

| Hormone therapy | No | 192 | 37.4 |

| Yes | 321 | 62.6 |

The sum of the percentages does not equal 100% because of rounding. MRM, modified radical mastectomy; BCS, breast conserving surgery.

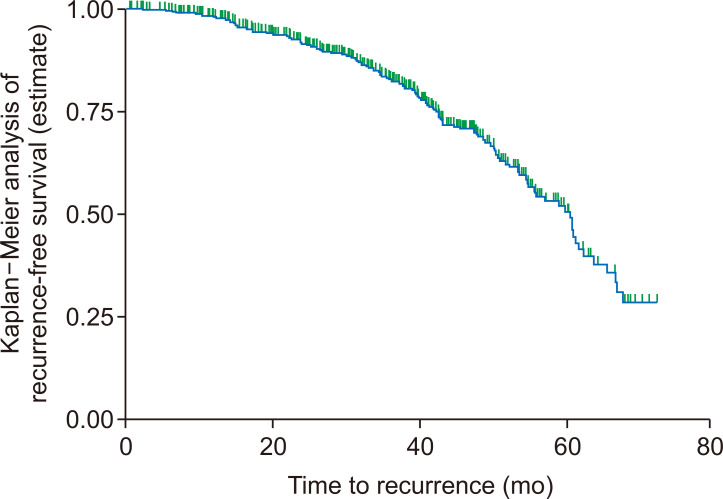

The incidence of recurrence

The overall incidence rate of recurrence in the cohort during the 1,459 person-years of observation was 6.5 per 100 person-years (95% CI = 4.62-11.58) follow-up. In the present study, median RFS time was 60.33 months (95% CI = 54.46-62.30). The estimated recurrence free survival was 98.1%, 91.5%, 82.4%, 68.8%, 50.5% and 28.5% at 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 months, respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Overall Kaplan–Meier analysis of recurrence-free survival of breast cancer patients at Black Lion Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018.

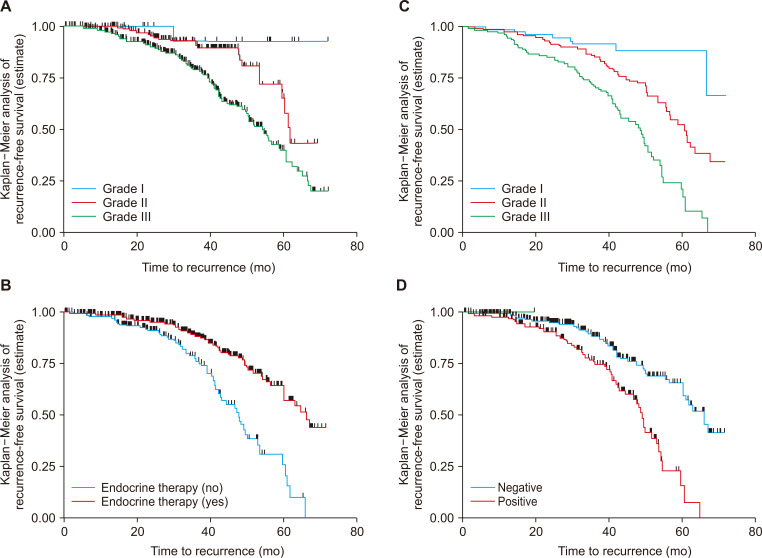

Recurrent free survival among different groups of breast cancer patients

The log-rank test was performed to test equality of RFS curves for the presence of any significant differences in time to recurrence among various levels of the categorical variables considered in the study. In this study, the test statistics showed that there was a significant difference in RFS function for different categorical variables. Accordingly, the Kaplan–Meier analysis indicated significant evidence of differences in time to event. The median recurrence time for those who were in clinical stage I and II at baseline was longer than that for patients with clinical stage (III) (50.9 months, 95% CI = 48.30-55.47). In addition, the median time to recurrence for those who were in histologic grade I and II at baseline was longer than that for those in clinical stage (III) (50.9 months, 95% CI = 48.30-55.47). In addition, the median time to recurrence for those who had histologic grade I and II at baseline had a longer than advanced histologic grade III (51.61 months, 95% CI = 45.96-58.73). This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.02). Similarly, the 6-year recurrence-free survival after breast cancer diagnosis was 53.5% for patients who received hormonal therapy and 34.2% for those who did not (Table 2, Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Recurrent free survival rates and median time to recurrence during 6-year of follow-up (Kaplan–Meier method) of breast cancer patients, Black Lion Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 2018 (n = 588)

| Characteristic | Median time to recurrence and 95% CI | 6-year RFS (%) | P-value with log rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | 0.05 | ||

| Urban | 43.60 (41.40-54.47) | 30.6 | |

| Rural | 45.70 (43.30-53.67) | 14.5 | |

| Menopause status | 0.09 | ||

| Premenopausal | 52.70 (50.47-58.65) | 41.7 | |

| Postmenopausal | 46.50 (44.54-56.72) | 25.3 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.004 | ||

| < 18.5 | 60.60 (58.30-68.60) | 44.0 | |

| 18.5-24.9 | 51.60 (49.20-60.50) | 38.0 | |

| 25.0-29.9 | 43.90 (42.40-52.90) | 33.5 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 37.60 (35.90-44.80) | 26.0 | |

| Comorbidity | 0.05 | ||

| No | 58.67 (53.84-64.00) | 33.6 | |

| Yes | 48.07 (46.60-54.39) | 13.9 | |

| Stage of breast cancer | 0.04 | ||

| I | 68.96 (63.30-74.63) | 89.6 | |

| II | 58.70 (55.25-62.18) | 39.5 | |

| III | 50.90 (48.30-55.47) | 21.2 | |

| Histology grade | 0.02 | ||

| Grade I | - | 57.2 | |

| Grade II | 62.76 (56.76-69.53) | 33.4 | |

| Grade III | 51.61 (45.96-58.73) | 9.2 | |

| Deep surgical margin | 0.07 | ||

| Free | 63.60 (59.70-66.80) | 55.3 | |

| Involved | 44.72 (39.74-52.34) | 8.7 | |

| No. of involved lymph node | 0.03 | ||

| < 2 | 58.40 (53.47-64.50) | 28.2 | |

| ≥ 2 | 52.90 (46.60-57.70) | 15.3 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||

| ≤ 2.5 | 54.80 (53.20-59.60) | 39.5 | 0.04 |

| 2-5 | 46.00 (42.90-54.20) | 13.4 | |

| > 5 | 45.00 (40.90-52.90) | 6.7 | |

| Hormone therapy | 0.01 | ||

| No | 43.34 (40.80-50.60) | 34.2 | |

| Yes | 67.20 (60.80-73.80) | 53.5 | |

| Lymph node status | 0.001 | ||

| Negative | 56.70 (53.80-63.80) | 35.7 | |

| Positive | 42.30 (38.40-51.20) | 10.1 | |

| Type of surgery | 0.3 | ||

| MRM | 44.40 (40.30-49.50) | 37.0 | |

| Breast-conserving therapy | 50.70 (49.70-61.10) | 22.0 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.06 | ||

| Yes | 55.80 (47.50-62.70) | 32.6 | |

| No | 47.20 (51.30-58.50) | 25.2 | |

| Estrogen receptor | 0.05 | ||

| Positive | 56.30 (53.40-63.80) | 51.0 | |

| Negative | 46.70 (40.00-57.70) | 44.6 | |

RFS, recurrent-free survival; MRM, modified radical mastectomy.

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier disease free survival function among different groups of breast cancer patients by stage at diagnosis (A), endocrine therapy (B), and node status (C), at Black Lion Specialized Hospital, Addia Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018 (n = 513).

Predictor’s of recurrence

In the multivariable Cox regression model, patients with negative estrogen receptor had nearly 2 times higher risk of recurrence than estrogen receptor positive ones. Those clients with histologic grade III were at 2.8 times higher risk of recurrence than histology grade I. Similarly, positive lymph node status (HR = 2.6, 95% CI = 1.14-10.31), clinical staging III (HR = 2.5, 95% CI = 1.26-9.42), and involved deep surgical margin (HR = 3.6, 95% CI = 2.14-8.61) were significantly associated (Table 3).

Table 3.

Proportional cox hazard regression analysis of predictors associated with recurrence among adult breast cancer patients at Black Lion Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa Ethiopia, 2018

| Variable | Recurrence | CHR | AHR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Place of origin | ||||

| Addis Ababa | 60 | 268 | 1 | 1 |

| Non-Addis Ababa | 35 | 150 | 1.04 (1.00-2.45)* | 1.50 (0.80-3.13) |

| Menopause status | ||||

| Premenopausal | 59 | 304 | 1 | 1 |

| Postmenopausal | 36 | 126 | 1.50 (0.65-3.65) | 1.80 (0.72-6.13) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| 18.5-24.9 | 49 | 297 | 1 | 1 |

| 25.0-29.9 | 37 | 110 | 2.03 (0.91-5.08) | 1.20 (0.76-6.89) |

| ≥ 30.0 | 9 | 11 | 4.90 (0.71-7.92) | 2.80 (0.47-4.66) |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Yes | 62 | 110 | 5.30 (1.13-10.40)* | 1.50 (0.73-4.29) |

| No | 33 | 310 | 1 | 1 |

| Stage of breast cancer | ||||

| I | 4 | 24 | 1 | 1 |

| II | 27 | 140 | 1.16 (1.00-3.08)* | 1.30 (0.64-2.08) |

| III | 64 | 254 | 1.51 (1.30-5.92)* | 2.50 (1.26-9.42)* |

| Histology grade | ||||

| Grade I | 10 | 63 | 1 | 1 |

| Grade II | 43 | 203 | 1.34 (1.40-6.09)* | 1.73 (0.67-4.53) |

| Grade III | 42 | 152 | 1.74 (1.28-14.06)* | 2.80 (1.14-10.31)* |

| Deep surgical margin | ||||

| Free | 30 | 317 | 1 | 1 |

| Involved | 65 | 101 | 6.80 (1.25-12.17)* | 3.60 (2.14-8.61)* |

| No. of involved lymph node | ||||

| < 2 | 33 | 90 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥ 2 | 62 | 178 | 0.94 (0.81-4.42) | 0.60 (0.53-3.20) |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||

| ≤ 2.5 | 11 | 102 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.5-5.0 | 31 | 146 | 1.96 (1.19-6.02)* | 1.60 (0.73-5.832) |

| > 5.0 | 53 | 170 | 2.89 (1.17-5.71)* | 1.50 (0.891-4.123) |

| Hormone therapy | ||||

| No | 49 | 143 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 46 | 275 | 0.48 (0.28-0.52)* | 0.63 (0.21-0.89)* |

| Lymph node status | ||||

| Negative | 36 | 327 | 1 | 1 |

| Positive | 59 | 91 | 5.88 (3.39-13.24)* | 2.60 (1.14-10.31)* |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| MRM | 72 | 375 | 1 | 1 |

| BCS | 24 | 42 | 2.97 (0.87-5.98) | 1.43 (0.48-4.62) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 55 | 341 | 0.31 (0.21-0.90)* | 0.87 (0.64-4.81) |

| No | 40 | 77 | 1 | 1 |

| Estrogen receptor | ||||

| Negative | 57 | 165 | 2.12 (1.36-6.27)* | 1.80 (1.53-7.62)* |

| Positive | 38 | 233 | 1 | 1 |

Values are presented as number only or hazard ratio (95% CI). Covariates adjusted in the final model: stage, histological grade, lymph node status, deep surgical margin, hormone therapy, adjuvant chemotherapy, tumor size, and estrogen receptor. CHR, crude hazard ratio AHR, adjusted hazard ratio. *The asterisks indicatethat the variables significantly associated with the outcome at bivariable and multivariable analysis with 95% level of significant (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

According this study, the incidence rate of recurrence was 6.5 per 100 person-years. Similarly, the overall cumulative incidence of recurrence was 18.5%. The current finding is consistent with a study conducted in Iran (20.2%) [21]. On the other hand, the rate is higher those observed in other studies conducted in Western Australia (3.3%) [9], Netherlands (11.6%) [7], Canada (6.4%) [16], Boston USA (13.5%) [22], Egypt (4.2%) [23], and South Korea (5.9%) [17], but lower than those in done in France (27.6%) [24]. Such differences could be due to delay in diagnosis and lack of awareness.

In this retrospective follow-up study, the overall RFS rates at 1, 3, and 6 years were 98.1%, 82.4%, and 28.5%, respectively. These values are lower than those reported in studies conducted in Iran: RFS at 2.5 years and 5 years were 86% (95% CI = 81-91) and 82.5% (95% CI = 77-87), respectively [21]. In Netherlands, 4 year RFS was 88.4% [7]. This difference might be attributed to centralization of care in the referral centers particularly in the study area. Additional factors include low access of care, lack of adequate qualified human power, and inadequate early screening and treatment.

According to the current study, the overall median RFS was 60.33 months (95% CI = 54.46-62.30). This RFS rate was higher than that observed in the previous studies in Canada (3.1 years) [16], in USA (4-years) [22], in Thailand (45.43 months) [10], and in South Korea (57 months) [17], but lower than that in France (7.2 years) [24] and in Iran (7 years) [21]. This difference is most probably due to the shorter duration of our study. It could also be due to different health seeking behavior and treatment adherence among those studies.

Our study demonstrated that lymph node-positive patients were 2.6 times more likely to become recurrent than lymph node-negative ones. This finding is in agreement with that reported in different developing and developed countries [9,23-25]. In the current study, estrogen receptor-negative cancer patients were 1.8 times more likely to become recurrent than estrogen receptor-positive ones. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in different regions of the world [9,24]. In agreement with previous studies [7,10,16,24,25], our study also showed that women with poorly differentiated histological tumor types were 2.8 times more likely to become recurrent than those with well differentiated histology.

As reported in other studies [23,24], the current finding also revealed that women who used hormone therapy were at lower risk of breast cancer recurrence than women who did not use hormone therapy. In addition, our study revealed that advanced breast cancer stage and involved in deep surgical margin were predictors for recurrence. Various studies have described an increased rate of recurrence among patients [7,24,26].

Study limitations

Selection bias is possibly introduced during secondary data collection because patients with incomplete records were excluded. Lack of data on hormone receptors; progesterone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Conclusion and recommendation

Over all the incidence rate of recurrence was relatively high. Advanced clinical stage, nodal status, high histologic grade, negative estrogen receptor, and involved deep surgical margin were associated with higher recurrence rates. In contrast, hormonal therapy has a great role in decreasing the development of recurrence. Therefore, improvement in the awareness of breast cancer prevention, screening and treatment in collaboration with public media is critical. Moreover, improvement in patient education and self-assessment may be important and underexplored factors in post-treatment care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Black Lion Specialized Hospital, data collector, oncology unit staffs, and supervisors for data management support.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. [Accessed October 19, 2017];GLOBOCAN 2012: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012 v1.0. https://www.altmetric.com/details/21798233.

- 3.World Health Organization, author. [Accessed December 31, 2017];Cancer facts & figures 2016-2017. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer.

- 4.American Cancer Society, author. Breast cancer facts & figures 2017-2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.African Cancer Registry Network, author. [Accessed February 16, 2018];Addis Ababa city cancer registry. http://afcrn.org/membership/members/100-addisababa.

- 6.Soerjomataram I, Louwman MW, Ribot JG, Roukema JA, Coebergh JW. An overview of prognostic factors for long-term survivors of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107:309–30. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9556-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franken B, de Groot MR, Mastboom WJ, Vermes I, van der Palen J, Tibbe AG, et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease recurrence and survival in newly diagnosed breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R133. doi: 10.1186/bcr3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Maaren MC, Strobbe LJA, Smidt ML, Moossdorff M, Poortmans PMP, Siesling S. Ten-year conditional recurrence risks and overall and relative survival for breast cancer patients in the Netherlands: taking account of event-free years. Eur J Cancer. 2018;102:82–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.07.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preen D, Kemp-Casey A, Roughead E, Lopez D, Bulsara M, Boyle F, et al. Determining breast cancer recurrence following completion of active treatment: a novel approach using linked administrative health data. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2017;1:190. doi: 10.23889/ijpds.v1i1.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wangchinda P, Ithimakin S. Factors that predict recurrence later than 5 years after initial treatment in operable breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:223. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0988-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spronk I, Schellevis FG, Burgers JS, de Bock GH, Korevaar JC. Incidence of isolated local breast cancer recurrence and contralateral breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast. 2018;39:70–9. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapoor T, Wrenn S, Callas P, James TA. Analysis of patient-detected breast cancer recurrence. Breast Dis. 2017;37:77–82. doi: 10.3233/BD-170288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cossetti RJ, Tyldesley SK, Speers CH, Zheng Y, Gelmon KA. Comparison of breast cancer recurrence and outcome patterns between patients treated from 1986 to 1992 and from 2004 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:65–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park S, Koo JS, Kim MS, Park HS, Lee JS, Lee JS, et al. Characteristics and outcomes according to molecular subtypes of breast cancer as classified by a panel of four biomarkers using immunohistochemistry. Breast. 2012;21:50–7. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metzger-Filho O, Sun Z, Viale G, Price KN, Crivellari D, Snyder RD, et al. Patterns of recurrence and outcome according to breast cancer subtypes in lymph node-negative disease: results from international breast cancer study group trials VIII and IX. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3083–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nottage MK, Kopciuk KA, Tzontcheva A, Andrulis IL, Bull SB, Blackstein ME. Analysis of incidence and prognostic factors for ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence and its impact on disease-specific survival of women with node-negative breast cancer: a prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R44. doi: 10.1186/bcr1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi YJ, Shin YD, Song YJ. Comparison of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence after breast-conserving surgery between ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:126. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0885-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bloom HJ, Richardson WW. Histological grading and prognosis in breast cancer; a study of 1409 cases of which 359 have been followed for 15 years. Br J Cancer. 1957;11:359–77. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1957.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compten CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. Springer; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kheradmand AA, Ranjbarnovin N, Khazaeipour Z. Postmastectomy locoregional recurrence and recurrence-free survival in breast cancer patients. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:30. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaz-Luis I, Ottesen RA, Hughes ME, Marcom PK, Moy B, Rugo HS, et al. Impact of hormone receptor status on patterns of recurrence and clinical outcomes among patients with human epidermal growth factor-2-positive breast cancer in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: a prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R129. doi: 10.1186/bcr3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elsayed M, Alhussini M, Basha A, Awad AT. Analysis of loco-regional and distant recurrences in breast cancer after conservative surgery. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:144. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0881-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lafourcade A, His M, Baglietto L, Boutron-Ruault MC, Dossus L, Rondeau V. Factors associated with breast cancer recurrences or mortality and dynamic prediction of death using history of cancer recurrences: the French E3N cohort. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:171. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4076-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee ES, Han W, Kim MK, Kim J, Yoo TK, Lee MH, et al. Factors associated with late recurrence after completion of 5-year adjuvant tamoxifen in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:430. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2423-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu L, Liu Z, Qu S, Zheng Z, Liu Y, Xie X, et al. Small breast epithelial mucin tumor tissue expression is associated with increased risk of recurrence and death in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:71. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]