Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder lacking effective treatments. ALS pathology is linked to mutations in several different genes indicating...

Keywords: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), TDP43, FUS, C9ORF72, phospholipase D (PLD)

Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder lacking effective treatments. ALS pathology is linked to mutations in >20 different genes indicating a complex underlying genetic architecture that is effectively unknown. Here, in an attempt to identify genes and pathways for potential therapeutic intervention and explore the genetic circuitry underlying Drosophila models of ALS, we carry out two independent genome-wide screens for modifiers of degenerative phenotypes associated with the expression of transgenic constructs carrying familial ALS-causing alleles of FUS (hFUSR521C) and TDP-43 (hTDP-43M337V). We uncover a complex array of genes affecting either or both of the two strains, and investigate their activities in additional ALS models. Our studies indicate the pathway that governs phospholipase D activity as a major modifier of ALS-related phenotypes, a notion supported by data we generated in mice and others collected in humans.

AMYOTROPHIC lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder that selectively involves motor neurons (MNs) in the brain and spinal cord, resulting in progressive muscle weakness and atrophy (Rowland 2001). Nearly all patients with ALS eventually succumb to respiratory failure 3–5 years after disease onset (Brown and Al-Chalabi 2017). The ALS association (http://www.alsa.org/) estimates that the incidence of ALS is ∼2 per 100,000 people. Because of disease severity, the rapid course of the disease, and lack of effective treatments, there is a great unmet need to develop novel therapies (Moujalled and White 2016; Abe et al. 2017; Hardiman and van den Berg 2017). ALS pathology has been linked to mutations in >20 different genes indicating a complex underlying genetic architecture (Gros-Louis et al. 2006; Maruyama et al. 2010; Turner et al. 2013). Nevertheless, mutations identified via genome-wide association studies account for only 5–10% of cases (familial ALS; fALS) (Rothstein 2009; Byrne et al. 2011; Bunton-Stasyshyn et al. 2015). The remaining cases are defined as sporadic ALS (sALS) and occur in individuals who lack familial inheritance of known fALS genetic variants. fALS variants have been identified in some individuals within sALS populations (Gibson et al. 2017), reflecting the complex genetic circuitry and the potential occurrence of de novo mutations associated with ALS.

Two dominant mutations in Fused in Sarcoma (FUS) and Transactive Response DNA binding protein 43 kD (TARDBP; encoding the TDP-43 protein), have been shown to cause fALS, and also some rare cases of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (Mackenzie et al. 2010). Both genes encode RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) as, indeed, several ALS-causal genes have been implicated in RNA metabolism, suggesting that this cellular function is closely associated with the disorder (Ito et al. 2017; Ghasemi and Brown 2018). Along with FUS and TARDBP (TDP-43), Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72) and Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) define the most prevalent fALS genes (Lagier-Tourenne et al. 2010; Ling et al. 2013; Turner et al. 2013; Renton et al. 2014). Both FUS and TDP-43 proteins are ubiquitously expressed, predominantly localized to the nucleus where they are implicated in various aspects of RNA metabolism (Crozat et al. 1993; Prasad et al. 1994; Buratti and Baralle 2001; Iko et al. 2004; Andersson et al. 2008; Ayala et al. 2008; Winton et al. 2008; Tan and Manley 2009; Kato et al. 2012; King et al. 2012; Deng et al. 2014). TDP-43- and FUS-associated pathologies are characterized by formation of intracellular protein aggregates in brain and spinal cord neurons and glia, a phenomenon shared by many neurodegenerative diseases (Arai et al. 2006; Neumann et al. 2006; Kwiatkowski et al. 2009b; Vance et al. 2009; Tateishi et al. 2010).

The pioneering work of the Bonini laboratory has demonstrated the utility of Drosophila as an experimental system to investigate neurodegenerative diseases, and ALS in particular (McGurk et al. 2015; Goodman and Bonini 2020). To better understand the involvement of TDP-43 and FUS in ALS and to probe the genetic circuitry that underlies ALS-related pathology, we took advantage of the genetic tools offered by Drosophila to systematically identify modifiers of TDP-43- and FUS-related phenotypes. We assume that the identification of genes capable of modifying ALS-related phenotypes in animal models may point to promising therapeutic targets and potentially novel pathways involved in disease. The Drosophila genome contains orthologs of most of the known ALS-causal genes, including TAR DNA-binding protein-43 homology (TBPH aka dTDP-43) and cabeza (caz aka dFUS), orthologs of TDP-43 and FUS, respectively. The phenotypes associated with mutations in these two genes, or with ectopic expression of human variants, manifest in several tissues known to be affected in patients with ALS.

In Drosophila, loss of dTDP-43 is semilethal (Feiguin et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2011), causing reduced larval motility and disruptions in neuromuscular junction (NMJ) morphology (Feiguin et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2011). Neuronal overexpression of wild-type human TDP-43 (hTDP-43) causes a decrease in NMJ bouton and branch number associated with protein aggregates (Li et al. 2010), indicating that loss or gain of TDP-43 function affects NMJ morphology. Other studies confirmed that overexpression of wild-type or mutant hTDP-43 in Drosophila or mice leads to locomotor defects (Wegorzewska et al. 2009; Li et al. 2010; Ritson et al. 2010; Voigt et al. 2010; Estes et al. 2011; Lin et al. 2011; Miguel et al. 2011). Expression of any of several hTDP-43 transgenic constructs carrying wild-type and disease-associated alleles in the developing Drosophila eye cause roughness, loss of pigmentation and neuronal degeneration (Li et al. 2010; Ritson et al. 2010; Voigt et al. 2010; Estes et al. 2011; Lin et al. 2011; Miguel et al. 2011).

Loss of dFUS causes reduced eclosion rates and life span, as well as locomotion defects (Wang et al. 2011; Xia et al. 2012), phenotypes that are rescued by neuronal expression of Drosophila or human FUS, reflecting a conserved function (Wang et al. 2011). Furthermore, expression of several fALS-linked missense alleles affecting the nuclear localization signal (NLS) in the Drosophila eye cause age- and dosage-dependent degeneration (Lanson et al. 2011). Ectopic expression of hFUS carrying ALS-causing variants (R518K or R521C) in Drosophila causes eye, brain, and MN degeneration (Daigle et al. 2013). Taken together, these observations reinforce the notion of functional conservation across species barriers, and our premise that Drosophila offers a suitable model to probe TDP-43 and FUS function.

Here, we explore the genetic circuitry that underlies Drosophila models of ALS by performing two independent genome-wide screens for enhancers and suppressors of the degenerative phenotypes associated with the expression of transgenic constructs carrying fALS-causing alleles of hFUS (hFUSR521C) and hTDP-43 (hTDP-43M337V). We uncover a complex array of genes that affect either, or both, of the two strains and corroborate these findings in secondary functional genetic assays using additional Drosophila ALS models we developed. Among the many modifying genes we identified, most of which have not been associated previously with ALS, these analyses also identify the pathway that governs phospholipase D (PLD) activity as a major modifier of ALS-related phenotypes. We further assessed the effect of PLD deletion in an SOD1 mouse model of ALS and observed modest functional benefits. Thus, our studies afford novel insights into the genetic architecture that can modulate fALS-causing mutations, and importantly, point to novel genes and pathways that constitute potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks and culture

All Drosophila stocks were maintained on standard Drosophila medium at 25°C. The generation of the GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V screening strains has been previously described (Periz et al. 2015). We generated a GMR-GAL4, UAS-c9orf72(G4C2)30-EGFP (GMR-c9orf7230) recombinant line using the previously described GAL4 inducible UAS-c9orf72(G4C2)30-EGFP transgenic strain (Xu et al. 2013). The full genotype of this strain is w; GMR-GAL4, UAS-c9orf72 (1–8M)/CyO. All three dTDP-43 transgenic constructs were inserted into the pUASg.attB third chromosome site. We subsequently made a GMR-Gal4/CyO; UAS-dTDP-43mNLS/TM6B, Tb, Tub-GAL80 for analyzing dTDP-43 aggregates in third instar larval eye imaginal disc studies. In addition, we generated OK371-GAL4, UAS-CD8-GFP/CyO; UAS-dTDP-43N493D/TM6B, Tb, Tub-GAL80 strain for NMJ analyses. The GMR-GAL4 and TM6B, Tb Hu chromosomes used to generate the screening stock were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center.

The following Drosophila strains were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. GAL4-inducible RNA interference (RNAi) knockdown, overexpression or expression of dominant negative versions of the following genes and associated Bloomington Stock Identifications (BSID): ArfGAP3RNAi: BSID – 27183; ArfGAP3RNAi: BSID – 31156; Ask1RNAi: BSID – 32464; Ask1RNAi: BSID – 35331; futschEP1419: BSID – 10571; GLE1RNAi: BSID – 52888; HDAC6 RNAi: BSID – 31053; lilliRNAi: BSID – 26314; Marf RNAi: BSID – 31157; PldRNAi: BSID – 32839; RalaRNAi: BSID – 34375; RalaDominant Negative: BSID – 32094; RglRNAi: BSID – 28938; SF2RNAi: BSID – 29522; and SF2RNAi: BSID – 32367 .

The UAS-dPld13 (Raghu et al. 2009) was a generous gift of Dr. Raghu Padinjat.

Generation of dTDP-43 transgenic constructs

CLUSTAL online software (Chenna 2003; Larkin et al. 2007) was used to align hTDP-43 and Drosophila TBPH (dTDP-43). Mouse and zebrafish TDP-43 orthologs were also used to improve the alignments (data not shown) (Supplemental Material, Figure S1). To construct the pUASg.attB-derived plasmids for the generation of the transgenic flies harboring the wild type or mutant forms of dTDP43, the wild-type genes were amplified from the pMK33-C-tbph plasmids (Guruharsha et al. 2011; Yu et al. 2011). The genes were initially cloned into the pDONR221 vector and followed by the final cloning into the pUASg.attB vector (Bischof et al. 2013) (a kind gift of Dr Konrad Basler). The mutations were subsequently introduced into the gene sequences using a QuickChange II Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Genetic modifier screens

Individual strains from the Exelixis Collection (Artavanis-Tsakonas 2004; Parks et al. 2004; Thibault et al. 2004) were tested for the ability to genetically modify the GMR-GAL4-induced UAS-hFUSR521C and UAS-hTDP-43M337V eye degeneration phenotypes by mating three to five males of the Exelixis strain to three females of the GMR-GAL4/CyO; UAS-hFUSR521C/TM6B, Tb, Tub-GAL80 and GMR-GAL4, UAS-hTDP-43M337V/CyO, Tub-GAL80 screening stocks. Fifteen days after being initiated, crosses were scored for alterations in the degenerative rough-eye phenotypes and/or restoration of pigmentation. Those inserts that improved the degenerative phenotypes were called suppressors (S), while those that made the phenotypes worse were deemed enhancers (E). The phenotypes were qualitatively scored from one to three; modifiers assigned a score of one are considered weak, a score of two is considered intermediate, and a score of three is considered strong. Those inserts scoring two or above were retested using a similar crossing scheme. Only those that displayed the same modification, independent of strength, were considered to be validated and therefore bona fide modifiers.

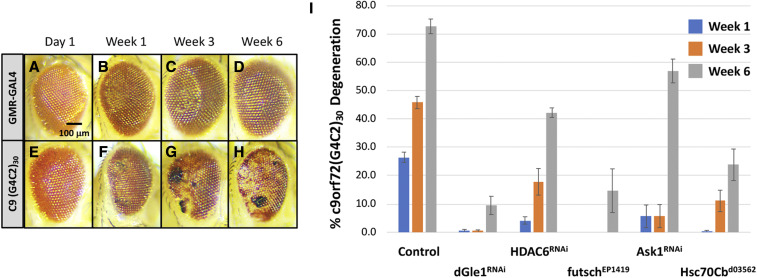

c9orf72 progressive model of neurodegeneration

Newly emerged w; GMR-c9orf7230 animals exhibited weak roughness and slight disruptions to the ommatidial array with associated loss of pigmentation, suggestive of neurodegeneration (Figure 3), a phenotype that is dosage-sensitive as homozygous GMR-c9orf7230 individuals result in a more severe phenotype (data not shown). To determine whether GMR-c9orf7230 was indeed progressive, we aged a population of GMR-c9orf7230 animals for 6 weeks and, at 3 different time points (weeks 1, 3, and 6), calculated the percentage of animals displaying black necrotic tissue, an indicator of c9orf72(G4C2)30 neuronal degeneration (Zhang et al. 2015). Detection of a single black necrotic spot on a single eye within an individual was considered neurodegenerative and scored positive in this assay. Within the population of GMR-c9orf7230/+ control animals, we observed an increase in the penetrance of the black necrotic tissue at weeks 1, 3, and 6 (Figure 3, E–H); this increase in the percentage of the degenerative phenotype was quantified and is displayed as a histogram in Figure 3I.

Figure 3.

C9ORF72 GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat model of progressive neurodegeneration. The GAL4-inducible c9orf72(G4C2)30 transgenic construct was assessed for a progressive neurodegenerative phenotype using the GMR-GAL4 driver over a period of 6 weeks. Neurodegeneration was scored as the presence of black necrotic tissue on the cuticle of the eye. Within a given genotype, the penetrance of neurodegeneration was determined as the fraction of individuals exhibiting black spots within the entire population at multiple time points. Two crosses per genotype were examined and averaged to determine the penetrance of the phenotype. The presence of a single spot on a single eye was considered positive, regardless of the magnitude of the spot(s). (A–D) Representative eye images of aged GMR-GAL4 individuals display no cuticular photoreceptor degeneration as determined by the presence of black necrotic spots over a period of 6 weeks. (E–H) Representative images of aged GMR-GAL4, UAS-c9orf72(G4C2)30/+ (GMR-c9orf7230) individuals. Eyes were photographed at day 1 (shortly after hatching), and after 1, 3, and 6 weeks. We note that the darkening of the eye color is an aging effect and does not reflect degeneration. (I) Histogram representation of percent GMR-c9orf7230/+ individuals (control) displaying the degenerative phenotype at week 1 (blue), week 3 (orange), and week 6 (gray) showing an increase in penetrance of the degenerative phenotype with age. Several genes with established links to ALS are shown to dominantly suppress the GMR-c9orf7230/+ progressive degeneration validating GMR-c9orf7230 as an ALS-related model. Gene symbols and the Bloomington Stock IDs (BSID) are provided. dGLE1RNAi: BSID – 52888, HDAC6RNAi: BSID – 31053, futschEP1419: BSID – 10571, Ask1RNAi: BSID – 35331 and Hsc70Cbd03562 is an Exelixis Hsc70Cb allele. The animals of the resulting genotypes were examined: GMR-c9orf7230/+ (control), GMR-c9orf7230/dGLE152888 (dGLE1RNAi), GMR-c9orf7230/+; HDAC631053/+ (HDAC6RNAi), futschEP1419/+; GMR-c9orf7230/+ (futschEP1419), GMR-c9orf7230/+; Hsc70Cbd03562/+ (Hsc70Cbd03562), and GMR-c9orf7230/+; Ask135331/+ (Ask1RNAi).

Drosophila gene assignments for the Exelixis Collection of transposon insertions

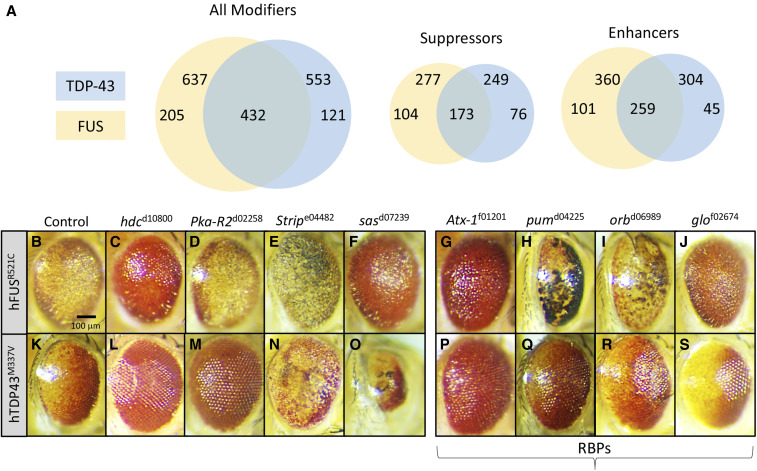

Data for Drosophila genes and Exelixis transposon insertion sites were obtained from FlyBase version 5.39, which was current as of August 2011 and is described elsewhere (Sen et al. 2013). The existing genomic sequence flanking all 15,500 inserts of the Exelixis Collection allowed for identification of affected genes (Sen et al. 2013). Using this analysis, we determined that the modifying insertions isolated by both screens combined correspond to a total of 758 total Exelixis strains, 205 strains unique to GMR-hFUSR521C, 121 strains unique to GMR-hTDP-43M337V and 432 strains recovered in both screens (Figure 2). We also identified 66 insertions (Table S1, column F, “Same modification”) not included in the summary Venn diagrams in Figure 2 that acted as an enhancer for one screening strain and as a suppressor for the other. Modifying inserts for which no gene assignment could be determined failed to land within 1 kb of any gene or were in genomic regions that contain no annotated genes; several of which may have localized to regions near nonprotein coding RNA species that were not annotated at the time of the aforementioned analysis.

Figure 2.

Screen results. (A) Venn diagrams showing the number of validated overlapping inserts with Drosophila gene assignments recovered in the screens. In total, 637 GMR-hFUSR521C and 553 GMR-hTDP-43M337V modifying insertions (enhancers and suppressors) were recovered and validated in each screen, with 432 insertions recovered in both screens. For GMR-hFUSR521C 277 suppressors and 360 enhancers were recovered; for GMR-hTDP-43M337V the totals were 249 and 304 suppressors and enhancers, respectively, which includes 173 overlapping suppressors and 259 overlapping enhancers. We note that genes recovered in both screens resulting in opposite modification phenotypes were not included in the suppressors and enhancers Venn diagrams. We also note that Table S1 includes all inserts recovered, not only those with clear Drosophila gene assignments in the Exelixis Collection. Panels B–S show examples of novel modifiers identified in our screens. Female eyes trans-heterozygous GMR-hFUSR521C (C–O) and with GMR-hTDP-43M337V(H–S) and enhancing or suppressing mutations are shown. Drosophila gene symbols and Exelixis Stock IDs are listed. Controls (B and G) demonstrate the eye degeneration phenotype. (C and H) hdcd10800 suppresses both screening strains, (D) Pka-R2d02258 has no effect on GMR-hFUSR521C, but (I) suppresses GMR-hTDP-43M337V, (E and J) Stripe04482 enhances both screening strains, (F) sasd07239 suppresses GMR-hFUSR521C, and (K) enhances GMR-hTDP-43M337V. (L–S) Mutations in different RBPs affect the GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V eye phenotypes. (L and P) Atx-1f01201 suppresses both screening strains, (M and Q) pumd04225 and (N and R) orbd06989 enhance GMR-hFUSR521C and weakly suppress GMR-hTDP-43M337V, and (O and S) glof02674 suppresses GMR-hFUSR521C and enhances GMR-hTDP-43M337V.

Mapping Drosophila genes to human orthologs

Version 7.1 (March 2018) of the DRSC Integrative Ortholog Prediction Tool (DIOPT) (http://www.flyrnai.org/cgi-bin/DRSC_orthologs.pl#) was used to determine the human orthologs, Human GeneID and the DIOPT ortholog score (Hu et al. 2011). The DIOPT ortholog score uses a 1–15 scale, where the higher the number, the better the orthology. It should be noted that for Drosophila genes for multiple human orthologs were determined, the ortholog with the highest DIOPT ortholog score is listed.

NMJ analyses

Third instar larvae were dissected in cold 1 × PBS and fixed at room temperature (RT) for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. The samples were washed in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (PTX) and incubated overnight at 4° with primary antibody. The primary antibody was washed off with PTX at RT. The samples were incubated at RT with secondary antibody for 90 min. This was followed by a PTX wash, and the tissues were mounted in Vectashield mounting media with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Bouton numbers were counted using a Zeiss 710 microscope, based on the Discs large protein (Dlg) and anti-HRP staining in the A3 segment muscle 6/7 as indicated. At least 10–15 animals of each genotype were dissected for the bouton analysis. The ANOVA multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis of the bouton number/muscle.

Eye imaginal disc preparation and analysis

Third instar larvae were dissected and fixed as described previously (Kankel et al. 2004). Discs were stained at RT with the following primary antibody in PBS Triton X-100:rabbit anti-TDP43 (Proteintech) at 1:500, and discs were mounted in Vectashield with DAPI. The secondary antibodies used for visualization includes Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse (green) and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit (red), both at 1:1000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Microscopy

All confocal images were collected using a Zeiss LSM710 point scanning confocal inverted imaging system using a ×20 and ×40 objective lens. Confocal scanning was performed using the following lasers: 405, 488, and 561 nm. The image acquisition software used was Zeiss Zen (black edition). All samples were mounted and imaged in Vectashield mounting medium supplemented with DAPI (Vector Laboratories) at RT. Adobe Photoshop CS5 was used to further process representative confocal images.

Survival, weight gain, and behavioral testing in mice

Survival data were collected based on either the date of natural death or end stage, which is defined as the age at which mice could no longer right themselves in under 30 S when placed on their back (righting reflex) (Staats et al. 2013). Weight and behavior were measured every 10 days starting from P 100 (post natal day 100). The fore and hind limb grip strength test was recorded using the Bioseb instrument by the same technician throughout the whole experiment, and the average strength value (g) of five tests was used for analysis (https://www.bioseb.com/bioseb/anglais/default/item_id=48_Grip-Test.php). The inverted grip strength test was performed as timing the latency that a mouse can hold the grid upside down and the average time (in s) of three tests were documented (Deacon 2013).

Data availability

All reagents and strains described in this study are freely available to the scientific community without any restrictions. The authors affirm that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions of the article are present within the article, figures, and tables. Supplemental material available at figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.12202580.

Results

Genetic screen for modifiers of hFUSR521C and hTDP-43M337V photoreceptor degeneration

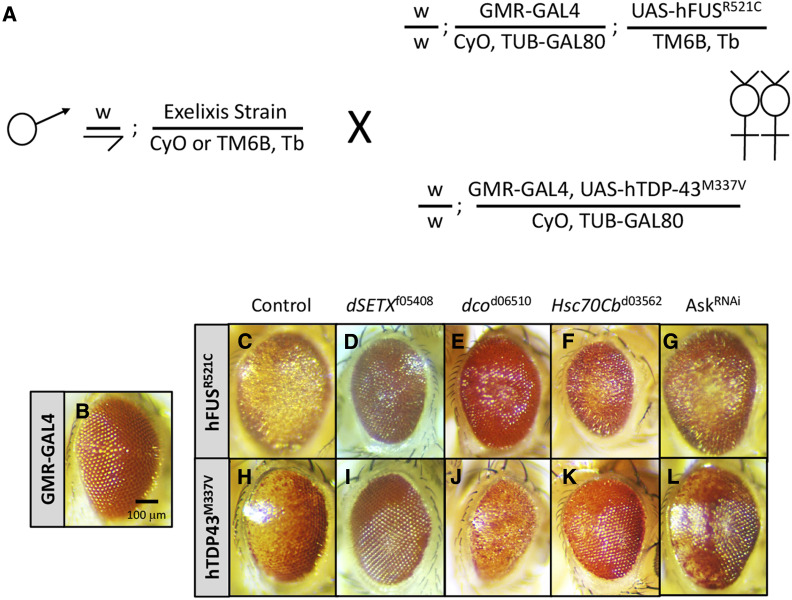

To explore the genetic circuitry underlying FUS- and TDP43-related activities, we carried out genetic screens (Figure 1A) for modifiers of degenerative eye phenotypes associated with the expression of hTDP-43 or hFUS transgenes carrying fALS-causing mutations. We generated two screening strains GMR-GAL4, UAS-hFUSR521C (GMR-hFUSR521C) and GMR-GAL4, UAS-hTDP-43M337 (GMR-hTDP-43M337V) (Figure 1, C and H) and tested their potential to identify bona fide ALS-related modifiers by examining whether the strains interact with genes that have been linked to ALS previously. Each strain displayed genetic interactions with the Drosophila ortholog of Senataxin (SETX), CG7504 or dSETX, (Chen et al. 2004), discs overgrown (dco) (Choksi et al. 2014), Hsc70Cb (Song et al. 2013; Nagy et al. 2016), and Apoptotic signal-regulating kinase 1 (Ask1) (Fujisawa et al. 2016) (Figure 1, D–L). On the basis of these observations we concluded that both strains were suitable to screen for ALS-related modifiers. We note that the Exelixis alleles used throughout the study are in the same genetic background, a genetic background that is distinct from those associated with other publicly available alleles (e.g., Ask1RNAi).

Figure 1.

Screening strategy and primary screen validation. (A) Schematic of primary screens for Exelixis insertions that alter degenerative eye phenotypes associated with w; GMR-GAL4; UAS-hFUSR521C (GMR-hFUSR521C) and w; GMR-GAL4, UAS-hTDP-43M337V (GMR-hTDP-43M337V). These transgenic Drosophila models display photoreceptor degeneration/rough-eye phenotypes that are fully penetrant and dosage-sensitive (Ritson et al. 2010; Lanson et al. 2011; Periz et al. 2015). For the primary screen, we generated F1 individuals carrying an Exelixis insertion in trans with either GMR-hFUSR521C or GMR-hTDP-43M337V, which were scored for enhancement or suppression of the eye degeneration phenotype. All primary screen positive inserts were retested in a validation screen using an identical crossing scheme to confirm the initially observed interaction(s). (B) Control GMR-GAL4 heterozygous individual. The eyes of (C) GMR-hFUSR521C and (H) GMR-hTDP-43M337V heterozygous animals displaying degenerative, pigmentation, and rough-eye phenotypes. (D–G) GMR-hFUSR521C and (I–L) GMR-hTDP-43M337V were modulated by Exelixis inserts disrupting genes with known associations to ALS: (D and I) dSenataxinf05408, (E and J) discs overgrownd06510, (F and K) Hsc70Cbd03562, and an (G and L) GAL4-inducible RNAi allele Ask132464. All eyes shown are representative images from individual females. Exelixis stock IDs and Drosophila gene symbols are listed, Ask1RNAi refers to Bloomington Strain ID (BSID) 32464.

We screened the Exelixis Collection of 15,500 insertional mutation strains, which affects ∼50% of the Drosophila genome (Artavanis-Tsakonas 2004; Parks et al. 2004; Thibault et al. 2004) for dominant modification of the photoreceptor degeneration eye phenotypes associated with either of the GMR-hFUSR521C or GMR-hTDP-43M337V strains (Ritson et al. 2010; Lanson et al. 2011; Periz et al. 2015) (Figure 1A). The Venn diagrams in Figure 2A summarize the results of the screens. We identified 637 and 553 insertions that modified GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V phenotypes, respectively (Figure 2A and Table S1). Examples of the effects modifiers have on the GMR-hFUSR521C (top panels, Figure 2, B–F and Figure 2, L–O) and GMR-hTDP-43M337V (bottom panels, Figure 2, G–K and Figure 2, P–S) screening phenotypes are also shown in Figure 2.

It is important to keep in mind that genetic interactions identified in these screens define hypotheses and thus must be further corroborated. As one focuses on testing hypotheses related to specific modifiers, two caveats of these large-scale screens should be kept in mind. First, it is possible that some of the modifications scored reflect transgene modulation, rather than directly modulate ALS-related phenotype. Second, in some cases the GMR-GAL4 driver may contribute to the modification of the eye phenotypes in an additive or synergistic manner. Determining the specific contribution of the GMR-GAL4 driver to the observed effect for modifiers requires additional testing as there are, surprisingly, inserts that suppress one or both of the screening strains yet enhance the GMR-GAL4 rough-eye phenotype (data not show). However, we note that for the many screens we have carried out using the Exelixis Collection, we found that, in general, if a GAL4 contribution exists, the effects for the overwhelming majority of modifiers is mild, such that suppressors or enhancers can be identified unambiguously (Kankel et al. 2007; Chang et al. 2008; Hori et al. 2011; Pallavi et al. 2012; Sen et al. 2013).

We found that 205 strains specifically modified GMR-hFUSR521C while 121 were specific to GMR-hTDP-43M337V. A total of 432 inserts modified both strains (Figure 2A), suggesting considerable commonalities between functional effects of FUS and TDP-43 toxic mutations. The modifiers were further subdivided into specific and common suppressor and enhancer classes of the two screening strains as depicted in Figure 2A (Figure 2A and Table S1). All common enhancer and suppressor strains did affect the FUS and TDP-43 phenotypes in the same manner. However, we also identified 66 insertions (Table S1, column F, “Same modification”) not included in the summary Venn diagrams in Figure 2 that acted as an enhancer for one screening strain and as a suppressor for the other. While the underlying mechanism(s) of this differential behavior remains to be determined, it is reasonable to assume that differential modifications reflect underlying functional differences between FUS and TDP-43, which do not display identical pathophysiological behavior in the disease contexts (Kwiatkowski et al. 2009a; Vance et al. 2009; Mackenzie et al. 2010). We finally note that the total number of recovered modifiers represents nearly 5% of the screening library, which is similar to the rate of recovery of genes identified in previous modifier screens using this resource (Kankel et al. 2007; Hori et al. 2011; Pallavi et al. 2012; Sen et al. 2013).

Functional classification of modifiers

We used the Gene Ontology (GO) tools at the Panther Classification System (http://www.pantherdb.org/) (Mi et al. 2013) to evaluate the biological space encompassed by the gene networks defined in our screens. Panther identified several functional categories in which the predominant terms recovered included “nucleic acid binding,” “cytoskeletal protein,” “signaling molecule,” and “oxidoreductase activity” (data not shown). Members of the most prevalent class (including 64 different genes) identified were annotated as “nucleic acid binding.” These include DNA binding proteins and nucleases, but the most abundant subclass (37 different genes) were RBPs (Table S2) (examples shown in Figure 2, L–O and Figure 2, P–S), among which were both suppressors (Figure 2, L, O–R) and enhancers (Figure 2, M, N and S). Notably, 34 out of these 37 genes modified both FUSR521C and TDP-43M337V phenotypes. Cpsf160 and RpS2 modified only FUSR521C while larp modified only TDP-43M337V. The largest class of RBPs were messenger RNA (mRNA) processing factors (n = 11, of which 9 are involved in mRNA splicing and 2 are mRNA polyadenylation factors) followed by RRM domain containing proteins (n = 10). A noteworthy subclass includes proteins associated with stress granules, which are thought to play a significant role in ALS (Li et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2016; Markmiller et al. 2018). Markmiller et al., have identified ∼150 previously unknown human stress granule components using APEX proximity labeling, mass spectrometry, and immunofluorescence (Markmiller et al. 2018). Our screens identified the Drosophila orthologs of 72 of these novel stress granule genes (data not shown), including several that effected GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V (Markmiller et al. 2018), as well as a C9ORF72 dipeptide repeat toxicity assay.

A Drosophila c9orf72 ALS model

To further validate the links between a subset of the genes recovered in our screens and ALS-related biology, we developed and utilized secondary assays, based on the premise that modifiers scoring positive in several distinct ALS models more likely point to a common underlying disease mechanism and therefore constitute more promising potential therapeutic targets for sporadic forms of ALS. As the G4C2 hexanucleotide repeat expansion mutations in the c9orf72 gene represent the most common genetic cause of fALS (Renton et al. 2011), we adapted a c9orf72(G4C2)30 hexanucleotide repeat model of progressive degeneration using the previously described GAL4-inducible UAS-c9orf72(G4C2)30-EGFP transgenic strain (Xu et al.) as a secondary assay to corroborate the strongest suppressors identified in the two screens.

GMR-GAL4-driven UAS-c9orf72(G4C2)30-EGFP transgenic (GMR-c9orf7230) animals displayed progressive degenerative phenotypes over the course of 6 weeks (Figure 3, A–H). Eye degeneration was scored as the presence of one or more black necrotic patches within a single eye; the penetrance of this phenotype increased within the population of GMR-c9orf7230 animals over 6 weeks. Reduced penetrance of the black necrotic tissue at any one of the three time points (weeks 1, 3, or 6) was considered suppression. Figure 3I shows that this progressive degenerative phenotype could indeed be modulated by genes previously linked to ALS, including CG1474952888 (the Drosophila RNA export ortholog of GLE1: dGLE1), HDAC631053, futschEP1419, Ask135331, and Hsc70Cbd03562 (Zhang et al. 2008; Song et al. 2013; Taes et al. 2013; Coyne et al. 2014; Freibaum et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2015; Fujisawa et al. 2016; Nagy et al. 2016). We again note that the RNAi and Exelixis strains are in different genetic backgrounds.

We tested 84 of the strongest overlapping GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V suppressors in the GMR-c9orf7230 model and identified 56 genes as suppressors, 10 genes as enhancers, and 18 genes that had no detectable effect (Table 1). Among the strongest GMR-c9orf7230 suppressors (suppression at all three time points) was an overexpression allele of Hsc70Cbd03562, the Drosophila ortholog of HSPA4L (Figure 3I). This is noteworthy as Hsc70Cb overexpression suppresses several different Drosophila neurodegenerative models (Zhang et al. 2010; Kuo et al. 2013), while mammalian HSPA4L overexpression provides a survival benefit in two different SOD1 mouse models of ALS (Nagy et al. 2016).

Table 1. Effects of strongest GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V suppressors on GMR-c9orf72(G4C2)30-related photoreceptor neurodegeneration.

| Column A | Column B | Column C | Column D | Column E | Column F | Column G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exelixis insert | Fus modification | TDP-43 Modification | C9orf72 Modification | % c9orf72 Degeneration | % c9orf72 Degeneration | % c9orf72 Degeneration |

| Week 1 | Week 3 | Week 6 | ||||

| c00800 | S2 | S3 | S3 | 0 | 0 | 1.7 |

| c01016 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 2.6 | 12.2 | 58.5 |

| c01295 | S1 | S1 | S3 | 6.8 | 17.6 | 53.4 |

| c01399 | S2 | S2 | S1 | 14.2 | 18.4 | 50.5 |

| c02909 | S1 | S2 | S3 | 4.2 | 10.4 | 42.4 |

| c03244 | S2 | S1 | S3 | 8.1 | 12.9 | 34.9 |

| c04205 | S2 | S1 | S3 | 9 | 14.5 | 31.8 |

| c04522 | S1 | S1 | S3 | 0 | 8.9 | 46.5 |

| c04582 | S2 | S2 | S2 | 3.1 | 26.1 | Not done |

| c05668 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 18.2 |

| c06325 | S2 | S1 | S1 | 9.4 | 25.3 | 64.8 |

| c07023 | S2 | S3 | S3 | 4.8 | 9.8 | 46.1 |

| d00123 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 0 | 4.8 | 0 |

| d00147 | S2 | S1 | S1 | 4.4 | 26.1 | Not done |

| d01275 | S3 | S3 | S3 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| d01345 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 1.9 | 9.6 | 36 |

| d02380 | S2 | S1 | S3 | 0 | 3.8 | 39.6 |

| d02712 | S1 | S2 | S2 | 7.4 | 8 | 70 |

| d02769 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 0 | 0 | 8.3 |

| d02833 | S1 | S2 | S2 | 0 | 7.1 | Not done |

| d02874 | S1 | S1 | S1 | 5.7 | 45.7 | 67.6 |

| d03208 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 0 | 8.7 | 6.1 |

| d03562 | S3 | S3 | S3 | 0.7 | 7 | 25.6 |

| d04116 | S1 | S1 | S3 | 10.8 | 24 | 46.2 |

| d04883 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 5.8 | 29.8 | 61.4 |

| d05297 | S2 | S1 | S1 | 6.6 | 26.9 | Not done |

| d05884 | S2 | S1 | S2 | 2.4 | 28.6 | 70.3 |

| d06126 | S3 | S3 | S2 | 8.9 | 53.4 | Not done |

| d07098 | S1 | S1 | S2 | 0 | 16.4 | 23.4 |

| d08551 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| d09937 | S2 | S2 | S2 | 34.5 | 36.9 | 62.5 |

| d10223 | S2 | S3 | S2 | 0 | 18.4 | 60 |

| d10376 | S3 | S2 | S3 | 0 | 1.2 | 18.5 |

| d10800 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| d11666 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 5.6 | 9.4 | 26.5 |

| e00530 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 16.5 |

| e00651 | S2 | S1 | S3 | 7.3 | 11.9 | 44.2 |

| e00985 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 11.1 | 20.6 | 51.6 |

| e01238 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 1.1 | 7.1 | 4 |

| e01976 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 0 | 5.9 | 12.5 |

| e02098 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 3.4 | 15.2 | 43.8 |

| e02166 | S2 | S2 | S1 | 6.9 | 37.9 | 55.2 |

| e02234 | S1 | S2 | S1 | 15.2 | 27.7 | 54.3 |

| e02236 | S2 | S1 | S1 | 8.2 | 34.2 | 59.6 |

| e02284 | S3 | S3 | S3 | 7 | 19.1 | 43.9 |

| e02535 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 13.5 | 19.4 | 67.6 |

| e02684 | S2 | S1 | S2 | 13.5 | 30.8 | 53.9 |

| e02699 | S3 | S1 | S3 | 7.1 | 10 | 29.2 |

| e03409 | S2 | S2 | S1 | 16.9 | 20.4 | Not done |

| e04015 | S2 | S2 | S2 | 0 | 11.9 | 27.7 |

| e04545 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 6.1 | 13.2 | 40.2 |

| f01587 | S1 | S1 | S2 | 10.1 | 16.5 | 12.8 |

| f03242 | S3 | S2 | S3 | 0 | 0 | 16.2 |

| f03756 | S2 | S2 | S3 | 1.3 | 13 | 11.1 |

| f05408 | S2 | S3 | S3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| f06593 | S3 | S3 | S3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| c03600 | S2 | S2 | NE | 12.3 | 26.9 | 60.9 |

| c04473 | S2 | S2 | NE | 18 | 26.5 | 65.9 |

| c04797 | S2 | S2 | NE | 24.4 | 39.3 | 72.9 |

| c05977 | S2 | S1 | NE | 9.2 | 29.4 | Not done |

| c06293 | S2 | S2 | NE | 18.2 | 34.5 | 68.5 |

| c06703 | S1 | S2 | NE | 32.3 | 61.1 | 82.4 |

| c06744 | S2 | S2 | NE | 20.1 | 34.8 | 63.7 |

| c07042 | S1 | S1 | NE | 18.9 | 40.9 | 73.3 |

| c07155 | S2 | S2 | NE | 22.8 | 49.4 | 67.7 |

| d04075 | S2 | S3 | NE | 12.4 | 26.7 | Not done |

| d07488 | S2 | S2 | NE | 35.7 | 30.8 | 76.9 |

| d08578 | S2 | S2 | NE | 26.5 | 51.5 | 77.4 |

| d09179 | S2 | S1 | NE | Not done | 56.1 | 72.2 |

| e00355 | S2 | S2 | NE | 22.5 | 31.7 | 60.3 |

| e00777 | S2 | S2 | NE | 15.5 | 24.9 | 41.7 |

| e00785 | S2 | S2 | NE | 24 | 32.9 | 75.6 |

| e02741 | S2 | S2 | NE | 27.1 | 47.5 | 79 |

| f02738 | S1 | S1 | NE | 18.3 | 22.4 | 76.8 |

| c03467 | S2 | S2 | E2 | 41.5 | 52.5 | Not done |

| c03635 | S2 | S2 | E3 | 23.6 | 73.1 | 95.7 |

| c05849 | S2 | S1 | E1 | 26.7 | 57.5 | Not done |

| d02986 | S2 | S2 | E3 | 13.3 | 60.2 | 82.3 |

| d06616 | S2 | S2 | E3 | 60 | 80 | 87.5 |

| e02580 | S2 | S3 | E3 | 28.4 | 59 | 91.5 |

| e04200 | S2 | S2 | E2 | 66.9 | 85 | Not done |

| f01201 | S2 | S2 | E3 | 58.3 | 78.3 | 98.2 |

| f03408 | S1 | S1 | E1 | 20.4 | 50 | 77.8 |

| f05963 | S1 | S2 | E3 | 12.5 | 68.3 | 80.8 |

Effects of 84 overlapping suppressors of GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V degenerative eye phenotypes in a GMR-c9orf72(G4C2)30 model of progressive neurodegeneration. Insert number is listed in Column A, followed by the observed modification in the GMR-hFUSR521C (Column B) and GMR-hTDP-43M337V (Column C) screening strains. In Columns B and C, S1, S2, and S3 refer to the qualitative strength of suppression, where S1 is weak, S2 is moderate, and S3 is strong suppression. Column D depicts modification effect of the insertion on the GMR-c9orf72(G4C2)30 model, where S is suppression, E is enhancement, and NE is no effect. Columns E, F, and G provide the penetrance of the neurodegenerative phenotype at weeks 1, 3, and 6. S1/E1 is suppression/enhancement at one time point, S2/E2 is suppression/enhancement at two time points, and S3/E3 is suppression/enhancement at all three time points. Crosses were performed in batches and each insert was compared to control crosses (GMR-c9orf72(G4C2)30 crossed to isoA) for that particular batch (data not shown).

Drosophila TDP-43 ALS models

Given that the ALS models used thus far were based on the activities of human transgenes, we decided to corroborate some of our findings using homologous Drosophila constructs. We thus generated three transgenic strains harboring the Drosophila TDP-43 ortholog (dTDP-43): a strain carrying the wild-type gene (dTDP-43WT), a hTDP-43N378D cognate disease-associated strain (dTDP-43N493D), and a strain harboring a mutation in the NLS (dTDP-43mNLS) (Figure S1). Figure 4 shows that GMR-GAL4-directed expression of the dTDP-43WT and dTDP-43mNLS transgenes caused photoreceptor degeneration in adult animals (Figure 4, A–C), whereas dTDP-43N493D expression induced larval lethality (data not shown). We note that, unlike the GMR-hTDP-43M337V screening strain, which displays nuclear and cytoplasmic staining and tends to form few detectable aggregates (Figure S2, D and E, see arrows in E), each of these three Drosophila transgenic strains exhibited dTDP-43 cytoplasmic mislocalization and aggregate formation in third instar larval eye imaginal discs (Figure 4, D–F). Whether exogenous aggregated dTDP-43 causes endogenous dTDP-43 to mislocalize to the cytoplasm remains to be tested, as the antibody used in these studies detected only relatively low levels of endogenous dTDP-43 (Figure S2A). Nevertheless, aggregates are considered pathognomonic for ALS, but the disease-related mechanistic relationships of TDP-43 cytoplasmic aggregates to MN dysfunction and degeneration remain unclear. However, our findings are consistent with previous observations where expression of wild-type human and Drosophila TDP-43 as well as mutant (A315T) human and Drosophila TDP-43 formed cytoplasmic aggregates within the Drosophila neuropil (Estes et al. 2011). Additionally, moderate overexpression of wild-type hTDP-43 in mice also resulted in intranuclear and cytoplasmic aggregates (Xu et al. 2010).

Figure 4.

Drosophila TDP-43 ALS model. (A–F) Eyes from animals expressing GMR-GAL4 control (A) compared to GMR-dTDP-43WT (B) and GMR-dTDP-43mNLS (C). Expression of each construct results in ommatidia loss and a glossy appearance. GMR-GAL4-driven expression of dTDP-43N493D results in larval lethality. (D–F) Cytoplasmic aggregates are observed in eye discs from individuals with GMR-GAL4-driven (D) wild-type dTDP-43WT, (E) dTDP-43N493D, and (F) dTDP-43mNLS and stained with an antibody directed against human TDP-43 (red); nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). We note that in control animals relatively low levels of endogenous dTDP-43 expression was detected using this antibody (Figure S2A). (G–O) OK371-GAL4 drives expression of UAS containing transgenic constructs in larval motor neurons; the OK371-GAL4 driver strain carries UAS-CD8-GFP, which labels the cell membrane of transgene-expressing cells with GFP (green). As above, ectopic dTDP-43 protein is detected with anti-TDP-43 (red) and nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). (G–I) UAS-dTDP-43WT and (J–L) UAS-dTDP-43N493D show large cytoplasmic aggregated forms of dTDP-43, with little evidence of more broadly distributed cytoplasmic distributions, whereas (M–O) UAS-dTDP-43mNLS exhibits dTDP-43 cytoplasmic mislocalization but appears to produce fewer aggregates and a more diffuse cytoplasmic pattern.

We examined the ability of 16 of the identified modifiers (Table S3) to alter the GMR-dTDP-43mNLS eye imaginal disc aggregate formation phenotype. Seven of these modifiers altered the distribution of TDP-43 inclusions (Table S3), resulting in qualitatively fewer aggregates or more diffuse dTDP-43 cytoplasmic staining, whereas the other nine modifiers tested in this assay suppressed the degenerative GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V phenotypes, but had no apparent effect on dTDP-43 aggregate formation. We also examined aggregate formation in larval MNs. OK371-GAL4 larval MN-directed expression of dTDP-43WT (Figure 4, G–I), dTDP-43N493D (Figure 4, J–L) or dTDP-43mNLS (Figure 4, M–O) yielded viable strains, all of which showed various degrees of mislocalized dTDP-43 cytoplasmic aggregates. The formation of cytoplasmic aggregates in Drosophila MNs (and eye imaginal discs) are presumably analogous to the documented TDP-43 cytoplasmic aggregation in postmortem patient tissue observed in nearly all forms of ALS (Neumann et al. 2006; Ederle and Dormann 2017).

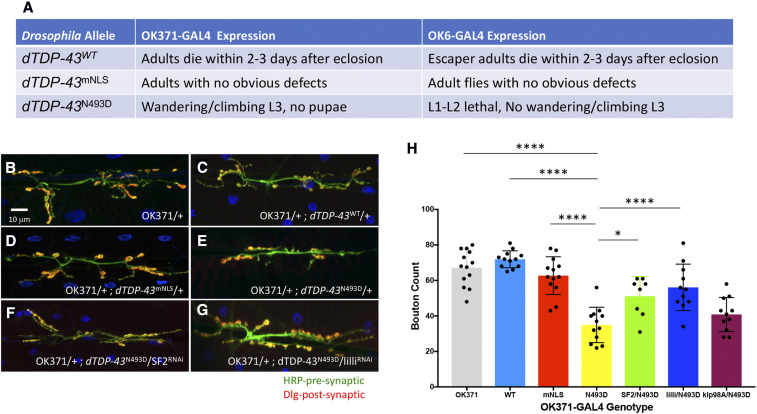

dTDP-43 NMJ morphological defects

Given the relevance of the MN system in ALS, we examined the consequences of MN-directed expression of the dTDP-43WT, dTDP-43mNLS, and dTDP-43N493D transgenic constructs on third larval instar NMJ morphology using two distinct MN drivers: OK371-GAL4 and OK6-GAL4 (Figure 5A). By counting the number of boutons per muscle as a proxy for NMJ defects, we found that OK371-GAL4, UAS-dTDP-43N493D (OK371-dTDP-43N493D) animals displayed significant bouton loss, whereas the dTDP-43WT and dTDP-43mNLS alleles did not display any detectable phenotypes when driven by OK-371-GAL4 (Figure 5, B–E).

Figure 5.

Modifier effects on dTDP-43 transgenic construct expression in the NMJ. (A) Table summarizing the observed phenotypes using two different GAL4 motor neuron drivers (OK371-GAL4 and OK6-GAL4) to direct expression of the following UAS containing transgenic constructs inserted into the ZH-86Fb attB third chromosome insertion site: dTDP-43WT, dTDP-43mNLS, and dTDP-43N493D. (B–G) Qualitative morphological effects on larval NMJs of the following genotypes: (B) OK371-GAL4, (C) OK371-GAL4/+; UAS-dTDP-43WT, (D) OK371-GAL4/+; UAS-dTDP-43mNLS/+, (E) OK371-GAL4/+; UAS-dTDP-43N493D/+, (F) OK371-GAL4/+; UAS-dTDP-43N493D/SF232367, and (G) OK371-GAL4/+; UAS-dTDP-43N493D/lilli26314. (H) Histogram representation of the quantification of the average bouton numbers per muscle in individuals from B–G. All genotypes listed are in an OK371-GAL4/+ background: OK371 are control OK-371-GAL4 heterozygous individuals (gray), WT (light blue), mNLS (red), and N493D (yellow) correspond to the dTDP-43 transgenic constructs, while SF2/N493D (green), lilli/N493D (blue), and klp98A/N493D (magenta) correspond to the SF232367, lilli26314, and klp98Ac05668 alleles in the background OK371-GAL4/+; UAS-dTDP-43N493D. The dTDP-43N493D strain displayed significant differences in NMJ bouton counts when compared to OK371-GAL4 (**** P < 0.001), OK371-GAL4/+; UAS-dTDP-43WT (**** P < 0.001), and OK371-GAL4/+; UAS-dTDP-43mNLS (**** P < 0.001). dTDP-43mNLS and dTDP-43WT bouton numbers were not significantly different from dTDP-43WT. SF2 (* P < 0.0031) and lilli (**** P < 0.001) alleles caused substantial improvement of NMJ morphology in comparison to OK371-dTDP-43N493D, while klp98A did not. Quantifications were done manually at the confocal microscope and statistical significance was determined by using an unpaired parametric t-test with Prism software. NMJ preparations were stained with anti-HRP (green) and anti-discs large (Dlg) (red) to mark pre- and postsynaptic structures, respectively, and muscle nuclei were labeled with DAPI. The asterisks above the lines correspond to the degree of significance between the denoted genotypes. The more asterisks, the smaller the P-value.

To examine whether the NMJ abnormalities associated with dTDP-43N493D expression are suitable for further modifier evaluations, we tested three of the strongest suppressors affecting all three ALS photoreceptor degeneration models (SF2, lilli, and klp98A) for their capacities to modify NMJ mutant phenotypes (Figure 5, F–G). We found that the loss-of-function alleles for SF232367 and lilli26314, but not for klp98Ac05668, significantly suppressed the OK371-dTDP-43N493D NMJ defects as determined by bouton counts (Figure 5H), indicating that the dTDP-43N493D NMJ phenotypes offer yet another way to evaluate ALS related modifiers. SF2 is the Drosophila ortholog of mammalian SRSF1, which is known to protect against the effects of c9orf72 expansion repeat-dependent phenotypes in Drosophila eyes and mammalian cell culture upon its reduction (Hautbergue et al. 2017). Furthermore, loss of lilli function was recently shown to suppress c9orf72-related phenotypes in Drosophila (Yuva-Aydemir et al. 2019). In the same study, the authors decreased expression of AFF2/FMR2 (one of four mammalian lilli orthologs), which rescued the axonal degeneration and TDP-43 pathology phenotypes in cortical neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells of patients with C9ORF72 mutation (Yuva-Aydemir et al. 2019). Consistent with these observations, we determined that reducing SF2 and lilli functions suppressed degeneration induced by GMR-hFUSR521C, GMR-hTDP-43M337V, and GMR-c9orf7230 (Figure S3).

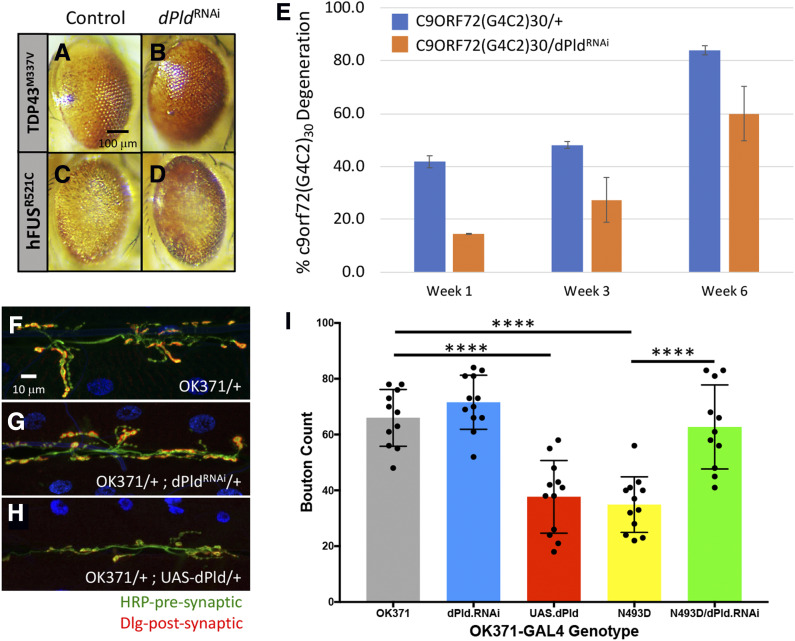

Loss of PLD function improves multiple Drosophila ALS phenotypes

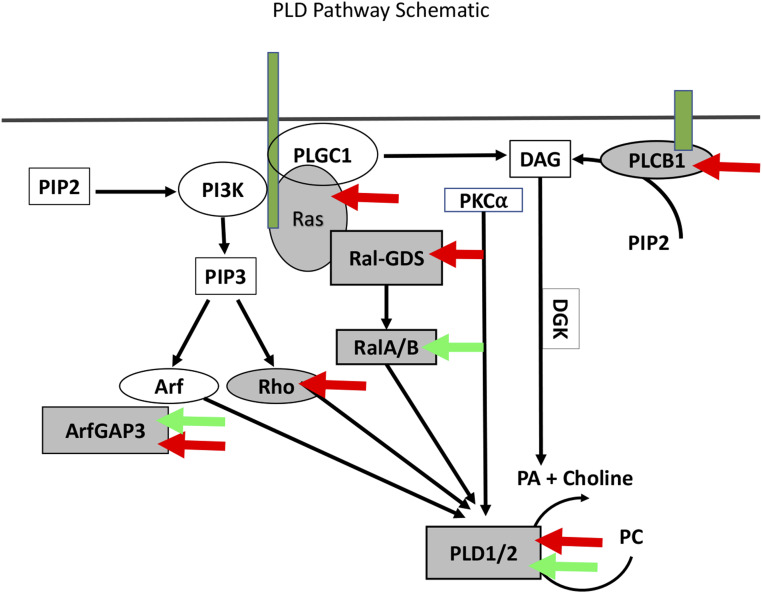

Our goal here is not only to define individual ALS modifier genes but, optimally, to identify pathways that are part of the genetic architecture underlying the pathobiology of ALS. In this regard, we were particularly interested in exploring the PLD biochemical pathway as, remarkably, six distinct components of the pathway were identified in our screens as ALS-related modifiers, indicating that PLD activity, and the potential that phosphatidic acid (PA) may play a significant role in modulating ALS-related pathophysiology.

We identified several orthologs of components of the mammalian PLD1/2 pathway as modifiers including dPld, ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase activating protein 3 (ArfGAP3), Phospholipase C at 21C (Plc21C), Rho1, Ras oncogene at 85D (Ras85D), and Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator-like (Rgl) (Table S4). RGL, an RalGDS family member, is known to interact with activated Ras as an effector of other Ras family members, such as RalA/B. Upon activation of RalA/B, a number of downstream effectors such as RalBP1 and PLD become activated, leading to a diverse series of biological outcomes (Bodemann and White 2008). We further explored the protective effects of PLD1 downregulation in the context of ALS pathophysiology using an independent GAL4-inducible RNAi dPld allele (dPld32839). This corroborated the finding that the downregulation of dPld suppressed the degenerative phenotypes associated with GMR-hFUSR521C, GMR-hTDP-43M337V, and GMR-c9orf7230 (Figure 6, A–E).

Figure 6.

dPLD effects on GMR-hFUSR521C, GMR-hTDP-43M337V, and GMR-c9orf72(G4C2)30 phenotypes. (A–D) RNAi-induced dPld reduction suppressed GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V phenotypes. Representative eye images of individuals carrying one copy of (A) GMR-hTDP-43M337V in trans with (B) UAS-dPld32839, or (C) GMR-hFUSR521C in trans with (D) UAS-dPld32839. dPld32839 expresses an RNAi directed against dPld. (E) Histogram representation of percentage of GMR-c9orf72(G4C2)30 individuals displaying the degenerative phenotype at week 1 (blue), week 3 (orange), and week 6 (gray). GMR-GAL4-directed expression of UAS-dPld32839 results in suppression of the c9orf72(G4C2)30-dependent neurodegenerative phenotype at all three time points. (F–H) Effects of motoneuron-driven dPLD on third instar larval NMJ morphology. Representative images of third instar larval NMJs from (F) control OK371-GAL4 as well as loss [(G) UAS-dPld32839] and gain [(H) UAS-dPld13] (Raghu et al. 2009) of dPld function in OK371-GAL4/+ background are shown. (I) Histogram representation of quantification of average bouton numbers per muscle in OK371-GAL4 (OK371), OK371-GAL4/+ UAS-dPld32389/+ (dPLD.RNAi, gray), OK371-GAL4/UAS-dPld13 (UAS.dPLD, red), OK371-GAL4, UAS-dTDP-43N493D (N493D, yellow), and OK371-GAL4, UAS-dTDP-43N493D/UAS-dPld32839 (N493D/dPLD.RNAi, green) individuals. Loss of dPld has no effect on OK371-GAL4 bouton number, whereas there is a statistically significant decrease (**** P < 0.0001) in bouton number when dPLD is ectopically expressed. Quantifications were done manually at the confocal microscope and statistical significance was determined by using an unpaired parametric t-test with Prism software. NMJ preparations were stained with anti-HRP (green) and anti-discs large (Dlg) (red) to mark pre- and postsynaptic structures, respectively, and muscle nuclei were labeled with DAPI. The more asterisks, the smaller the P-value.

Our observations were strengthened by the opposing phenotypic effects displayed by loss- and gain-of-function dPld alleles on third instar larval NMJ morphology in OK371-GAL4 and OK371-dTDP-43N493D animals (Figure 6, F–I). In an OK371-GAL4/+ background, loss of dPld function in MNs is without consequence, while MN-directed upregulation of a UAS-dPld wild-type transgenic construct significantly worsened NMJ morphology (Figure 6, F–H). We introduced these same loss- and gain-of-function dPld alleles into the OK371-dTDP-43N493D background to assess whether dPld function also affected larval NMJ defects. Consistent with our observations in the eye, loss-of-function dPld significantly improved the morphology of the OK371-dTDP-43N493D NMJ (Figure 7, G and I), while increasing dPld activity in this context resulted in lethality, with NMJ disorganization so extensive as to preclude bouton quantification.

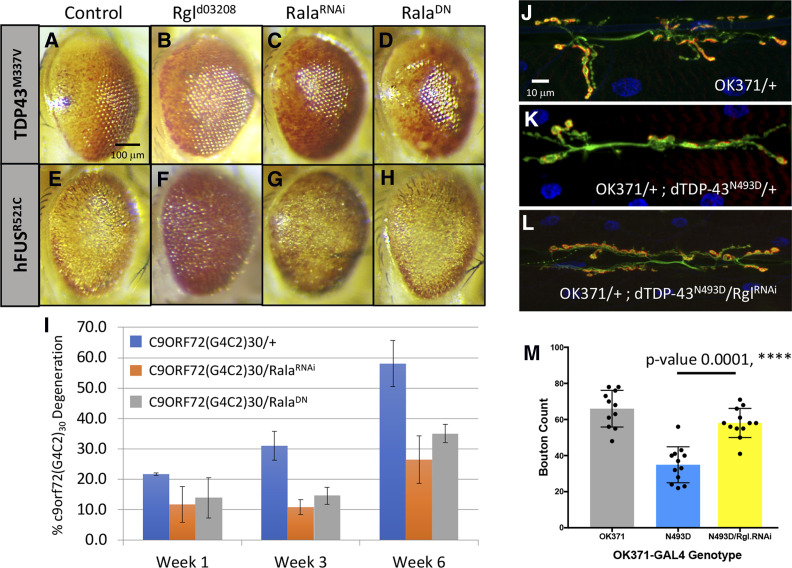

Figure 7.

dPLD1 pathway elements modify Drosophila ALS models. (A–H) Representative eye images of individuals containing carrying the (A) GMR-hTDP-43M337V transgenes in trans with (B) UAS-Rgld03208, (C) UAS-Rala34375 (RalaRNAi), and (D) UAS-Rala32094 (RalaDN) and the (E) GMR-hFUSR521C transgenes in trans with (F) UAS-Rgld03208, (G) UAS-Rala34375 (RalaRNAi), and (H) UAS-Rala32094 (RalaDN). Both FUS and the TDP-43 phenotypes were suppressed by Rgld03208 and Rala34375 (RalaRNAi). (I) Histogram representation of percentage of individuals displaying the degenerative phenotype at week 1, week 3, and week 6 for (I) GMR-c9orf72(G4C2)30/+ control (blue), (J) UAS-Rala34375/+; c9orf72(G4C2)30/+ (RalaRNAi) (orange), and UAS-Rala32094/+; c9orf72(G4C2)30/+ (RalaDN) (gray). Both Rala alleles strongly suppressed the penetrance of the degenerative c9orf72 phenotype. (J–M) Motor-neuron-directed reduction of Rgl affects OK371-GAL4; UAS-dTDP-43N493D/+ third instar larval NMJ morphology: representative images of control NMJs from (J) OK371-GAL4 (OK371/+) and (K) OK371-GAL4; UAS-dTDP-43N493D/+ individuals. (L) The OK371-GAL4; UAS-dTDP-43N493D/+ NMJ phenotype (K) appears to be qualitatively rescued by RNAi-induced reduction of Rgl (UAS-Rgl28938) (L). (M) Quantification of average bouton numbers per muscle in individuals of the OK371-GAL4 (OK371), OK371-GAL4; UAS-dTDP-43N493D/+ (N493D) and OK371-GAL4; UAS-dTDP-43N493D/UAS-Rgl29398 (N493D/Rgl.RNAi) genotypes. RNAi-induced reduction of Rgl results in a statistically significant increase in the number of boutons (**** P < 0.001). Quantifications were done manually at the confocal microscope and statistical significance was determined by using an unpaired parametric t-test with Prism software. NMJ preparations were stained with anti-HRP (green) and anti-discs large (Dlg) (red) to mark pre- and postsynaptic structures, respectively, and muscle nuclei were labeled with DAPI.

We further substantiated the involvement of the PLD1 pathway in the suppression of the ALS related phenotypes by examining the effects of Rgl (human ortholog: hRal-GDS) and Rala modulation (Figure 7, A–I). Rgld03208, which was isolated as a suppressor of the GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V eye phenotypes, also suppressed the GMR-c9orf7230 model of progressive degeneration (Figure S4). We also tested several Rala alleles in our ALS models and found that the Rala34375-inducible RNAi allele suppressed GMR-hFUSR521C, GMR-hTDP-43M337 and GMR-c9orf7230 models, while the dominant-negative Rala32094 allele (RalaDN) suppressed the phenotype in the GMR-c9orf7230 model (Figure 7, C–H and Figure 7I). Finally, we expressed different Rgl and Rala GAL4-inducible RNAi alleles (Rgl28938 and Rala29850) in OK371-dTDP-43N493D animals and showed that Rgl downregulation suppresses the NMJ phenotype associated with this genotype (Figure 7, J–M), in contrast to the Rala29850 RNAi allele, which had no detectable effect. In summary, these data highlight the role of the PLD pathway in ALS pathophysiology in the Drosophila models identifying the pathway as a potential therapeutic target.

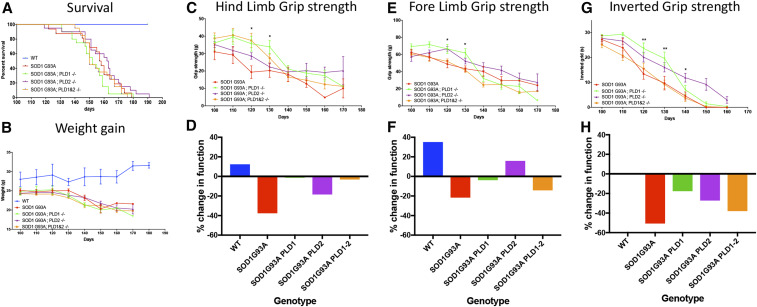

Genetic knockout of PLD1/2 function displays modest motor benefits in an SOD1 ALS mouse model

Prompted by our observations in Drosophila, the effect of Pld1, Pld2, and Pld1/2 ablation was assessed in the widely used, preclinical, SOD1G93A high-copy-number mouse model of ALS (Henriques et al. 2010). To this end, mice of three genotypes were generated and analyzed for functional outcomes [hindlimb grip strength, forelimb grip strength, and inverted grip strength, as well as weight gain and survival in SOD1G93A transgenic animals (SOD1G93A; PLD1−/−, SOD1G93A; PLD2−/− and SOD1G93A; PLD1−/− and PLD2−/−). As depicted in Figure 8, survival (Figure 8A) and weight gain (Figure 8B) were unaffected by elimination of Pld1, Pld2, or the Pld1/2 double knockout (all viable: Figure S5) (Sato et al. 2013). However, we observed a delay in the onset of functional deficits as measured by grip strength between days 100 and 140 (Figure 8, C, E, and G). The percentage grip strength change was measured between days 100 and 120 for all genotypes. The hindlimb and forelimb grip strength for the wild-type control cohort increased by 20%, whereas the SOD1G93A animals showed a loss for both measurements (Figure 8, D and F; see Figure 8 legend for change in grip strength calculations). In contrast, removal of PLD shows a modest benefit in these parameters, especially obvious when only Pld1 is removed, (Figure 8, D and F). Similarly, in inverted grip strength assays we also observe a modest benefit for all three genotypes compared to SOD1G93A animals (Figure 8H). However, these early benefits are not maintained over the course of disease progression. The functional benefits we observed in the mice appear to be consistent with the loss of Drosophila dPld in ALS models that protect NMJ morphology (Figure 6).

Figure 8.

Effects of genetic deletion of PLD in SOD1G93A Mice. Survival, weight, and behavior were measured every 10 days starting from P 100 (post natal day 100). (A) Elimination of PLD1, PLD2, or PLD1/2 combined had no effect on survival of SOD1G93A transgenic animals. (WT (n = 12), SOD1G93A (n = 16), SOD1G93A; PLD1−/− (n = 20), SOD1G93A; PLD2−/− (n = 20) and SOD1G93A; PLD1−/− and PLD2−/− (n = 20) mouse strains). (B) Starting from P 100, mice were weighed every 10 days. PLD1 and/or PLD2 elimination had no effect on the weight loss observed in the SOD1G93A animals. (C and E) Fore limb and hind limb grip strength test measured at P 120 and 130 showed significant improvement of both fore limb and hind limb strength in SOD1G93A; PLD1−/− strains, compared to SOD1G93A controls (* P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). In addition, SOD1G93A; PLD2−/− mice had greater fore limb strength and SOD1G93A; PLD1 and PLD2 greater hind limb strength at P 120, compared to the SOD1G93A mice (* P < 0.05) (n = 10 in SOD1 group and n = 20 in other groups). (D and F) Percentage change in grip strength from P 100 to P 120 (P 100 value − P 120 value)/P 100 value. Consistent with data in C and E, PLD knockout had mild beneficial effects in terms of fore and hind limb strength. (G and H) Inverted grip strength of the SOD1G93A; PLD1−/− and SOD1G93A; PLD2−/− mice is significantly improved at P 120 and P 130, respectively, compared to the SOD1G93A control animals (* P < 0.05 compared to SOD1G93A group, two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) (n = 10 in SOD1G93A group and n = 20 in other groups), meanwhile the percentage change was also analyzed and showed similar results.

We finally note that PLD1 and PLD2 homozygous controls, alone and together, were used as controls for the SOD1+/− mutants with the corresponding PLD1 and/or PLD2 homozygous genotype. The PLD1 and PLD2 littermates were not included as controls since the compound heterozygous SOD1; PLD1 and SOD1; PLD2 animals were not included in our analysis. Our data demonstrate that neither the PLD1 nor PLD2 heterozygous or homozygous knock out animals has a phenotype in terms of MN number, NMJ innervation, and behavior: we observed no difference between wild type, PLD1+/−, PLD2+/−, PLD1−/−, PLD2−/−, and PLD1/2−/− mutants (data not shown). In the absence of a hemizygous PLD1 or PLD2 phenotype, we decided that analysis of the PLD1 and PLD2 heterozygous mutants with or without SOD1 would not contribute further to our study.

Linking Drosophila screens to ALS patient analysis

In an effort to correlate findings from our screens to patient-derived data, we took advantage of a meta-analysis performed by Henderson and colleagues using a published study of postmortem gene expression in MNs from patients with sALS (Rabin et al. 2010; Kaplan et al. 2014). This analysis identified 41 genes for which high RNA expression levels are correlated with early disease onset. Our screen included 17 of these 41 genes as the rest did not have representative alleles in the Exelixis Collection used for the screens. While the functional significance of the increased expression of those genes in ALS is yet to be determined, it is certainly noteworthy that the Drosophila orthologs of 11 of these 17 genes were recovered as modifiers of the GRM-hFUSR521C and/or GMR-hTDP-43M337V models. These genes correspond to the human genes ARFGAP3, CASP3, MFN1, MFSD1, PLD1, RAB7L1, RALB, REL, SLC4A7, ZNF678, and TGFBR1 genes. Moreover, PLD1, RALB, and ArfGAP3, are components of the PLD1 signaling network, consistent with the notion that the PLD1 pathway may be involved in the modulation of ALS phenotypes.

Discussion

Knowledge of the genetic circuitry capable of modulating ALS phenotypes can provide critical insights into ALS-related mechanisms and identify specific gene targets or pathways as potential therapies. Consequently, the generation and validation of experimental tools that allow identification and dissection of genetic interactions underlying ALS-related phenotypes are extremely valuable and important. Given the remarkable conservation of biochemical and developmental pathways across species, our approach is based on the premise that the Drosophila orthologs of both TDP-43 and FUS are embedded in genetic pathways that are similar or identical to those of mammals. Identification of genetic modifiers of ALS model phenotypes not only serves to generate testable hypotheses for further understanding the biology associated with ALS pathogenesis, but may also provide additional value by uncovering targets that affect ALS disease progression. A strength of our current study lies in screening the Drosophila genome in an unbiased manner for modifiers using two independent ALS models (GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V) and validating a subset of the strongest, overlapping suppressors in a third model, GMR-c9orf7230. Validation across multiple genetic models increases the chance of identifying targets that are relevant to all patients with ALS, including those with sporadic forms of the disease that are clinically indistinguishable from the familial forms.

Functionalities of ALS-related genetic circuitry

The modifiers identified in our screens, included genes previously associated with ALS, validating our approach, as well as a large number of genes that have never before been associated with the disease. The most prevalent class of modifiers revealed by GO analyses are involved in RNA biology, corroborating its importance in ALS. GO analysis also identified a subset of genes that function in biological pathways associated with ALS pathophysiology, e.g., autophagy, mitochondrial/oxidative stress, apoptosis, neuroinflammation, cytoskeletal, vesicle trafficking, and protein aggregation. This observation agrees with multiple reports that diseases such as ALS, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) share pathophysiological features and cellular dysfunctions, including mitochondrial abnormalities/oxidative stress (Lin and Beal 2006; Liu et al. 2017), abnormal RNA biology (King et al. 2012; Ramaswami et al. 2013), and toxic protein aggregation (Ross and Poirier 2004), which displays transmissibility (Hasegawa et al. 2017). Further supporting the notion of commonalities across neurodegenerative diseases, several of the modifiers we identify not only affected our ALS models, but have also been associated with mammalian and Drosophila AD-, PD- and Spinal Muscular Atrophy-related models. For instance, the EIF4A1 modifier identified here was also recovered as a modifier in a Drosophila Spinal Muscular Atrophy model (Sen et al. 2013) and was reported to suppress FUS-dependent proteotoxicity in yeast cells and human HEK293T cells (Sun et al. 2011).

Among the many RNA biology-associated genes identified of particular interest are the Drosophila orthologs of SETX (dSETX) and SRSF1, Drosophila SF2. In humans, mutations in the SETX RNA:DNA helicase lead to a juvenile form of fALS (Chen et al. 2004) and ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2 (Moreira et al. 2004). In addition to dSETX, we also identified several other helicases, including DEAD-box helicase 5 (DDX5) and DEAD-box helicase 10 (DDX10). SRSF1, a gene that is involved in multiple aspects of RNA metabolism (Cáceres and Krainer 1993; Zuo and Manley 1993; Huang et al. 2004; Sanford et al. 2004; Zhang and Krainer 2004; Karni et al. 2008; Michlewski et al. 2008; Ben-Hur et al. 2013; Fregoso et al. 2013), modifies c9orf72 repeat expansion-dependent phenotypes through its role in the nuclear cytoplasmic pathway by limiting the nuclear export of c9orf72 transcripts (Hautbergue et al. 2017). Consistent with the potential importance of the nucleocytoplasmic pathway in ALS, seven different genes involved in this pathway—the Drosophila orthologs of nuclear transport proteins XPO5 and XPO1, the mRNA export gene GLE1, as well as core components of the nuclear pore (i.e., Nup88, Nup98, Nup155, and Nup205)—were recovered in our screens. The notion that disruptions to this pathway play a role in disease pathogenesis is consistent with the known cytoplasmic mislocalization of both FUS and TDP-43 proteins associated with ALS pathology, as well as with the finding that TDP-43 pathology disrupts nuclear pore complexes and nucleocytoplasmic transport in ALS/FTD (Freibaum et al. 2015; Jovičić et al. 2015; Chou et al. 2018).

Finally, we note that consistent with several recent studies implicating neuroinflammation in ALS (Chen et al. 2018), GO analysis identified NF-κB signaling as a modifier-enriched term. For example, we isolated a putative overexpression allele of Drosophila IRAK1 (Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1), as a strong enhancer of GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V phenotypes, raising the possibility that activation of NF-κB through increased activity of IRAK1 may contribute to disease. IRAK1 plays an essential role in the Toll-like receptor pathway by activating NF-κB and mitogen-activated kinases. This is of importance here as OPTN (Chen et al. 2018), mutations in which cause fALS, has been shown to bind to IRAK1 and additional data suggested that overexpression of OPTN inhibits IRAK-1-dependent NF-κB activation (Tanishima et al. 2017).

Potential therapeutic targets for ALS

A major motivation of our current study was to identify and probe genetic circuits and identify “druggable” targets for potential therapeutics. One modifier that may constitute a target for clinical development is PLD, an enzyme with broad physiological involvement that catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine into PA and choline. PA acts a second messenger in a broad spectrum of physiological processes (Bruntz et al. 2014). Significantly, our studies identified as modifiers several elements of the PLD pathway (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Multiple elements of the PLD1 pathway modify ALS-related phenotypes. Shown is a schematic depicting biochemical relationships leading to Pld production (Foster and Xu 2003). Red arrows point to pathway components identified as modifiers in our GMR-hFUSR521C and/or GMR-hTDP-43M337V screens. Green arrows point to elements reported to be upregulated in patients with early-onset, but not late-onset, ALS. In both the primary and validation screens six different Drosophila orthologs of components of the PLD1 pathway were recovered as modifiers of GMR-hFUSR521C and GMR-hTDP-43M337V: dPld, ArfGAP3, Rgl, Ras85D, Plc21C, and Rho1, which correspond to the human genes, PLD1, ARFGAP3, RALGDS, KRAS, PLCB1, and RHOA.

Though PLD1 itself has not been previously linked to ALS, its role in generating PA, which serves as a metabolite for membrane phospholipid biosynthesis, is particularly striking considering the described involvement of lipid metabolic pathways in MN degenerative diseases (Rickman et al. 2019). Moreover, PLD activity has been shown to be particularly important in cells under stress conditions while genetic variation in PLD1 has been linked to cancer as well as diverse neurodegenerative diseases, including AD and PD (Chung et al. 1995; Sung et al. 2001; Yoon et al. 2005; Cai et al. 2006; Brandenburg et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2009; Peng and Frohman 2012; Zhu et al. 2012; Barclay et al. 2013; Bruntz et al. 2014; Ammar et al. 2015; Rao et al. 2015).

The fact that we identified several elements within the entire PLD biochemical cascade as modifiers in our Drosophila ALS models presents a strong argument that the pathway may play an important role in modulating ALS disease pathophysiology. Importantly, we also observed phenotypic benefits upon genetic deletion of either PLD1 or PLD2, or both, in the SOD1G93A mouse ALS model, as well as associated elevation in PLD1 levels that correlate with early-onset ALS in human postmortem tissue. Our data therefore support the notion that PLD modulation may have therapeutic consequences for patients with ALS. In Drosophila, downregulation of PLD ameliorates degenerative phenotypes in all three ALS models: FUS, TDP-43, and C9ORF72. Whether this is also the case in analogous ALS mouse models remains to be determined.

Two PLD inhibitors are currently available; one is halopemide, which was developed as a neuropsychiatric drug (Bruntz et al. 2014; Zhang and Frohman 2014). In limited clinical trials, halopemide had no reported side effects at doses sufficiently high enough to fully block PLD activity (De Cuyper et al. 1984). This indicates that PLD inhibition does not cause major toxicity, even over prolonged periods of time. The second is a halopemide analog, FIPI (Su et al. 2009), which acts as a potent inhibitor of both PLD1 and PLD2, with half-life and bioavailability parameters that permit its use in cell culture and animal studies. Further data indicate that FIPI phenocopies outcomes observed in PLD knockout cell lines and animals, as well as in studies using PLD RNAi approaches (Dall’Armi et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2012; Sanematsu et al. 2013; Sato et al. 2013; Stegner et al. 2013) with no reported off-target effects. Hence, PLD1/2 inhibitors are tolerated in cellular and animal models and apparently satisfy clinical toxicity standards, suggesting that pharmacological inhibition of PLD in patients is likely to be a clinically viable strategy. In this context, it is also noteworthy that the mammalian genome encodes two paralogs, PLD1 and PLD2, and single and double knockouts of both PLD1 and PLD2 paralogs in mice are viable (Sato et al. 2013).

Given the well-documented role of PLD in AD and PD (Chung et al. 1995; Sung et al. 2001; Yoon et al. 2005; Cai et al. 2006; Brandenburg et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2009; Peng and Frohman 2012; Zhu et al. 2012; Barclay et al. 2013; Bruntz et al. 2014; Ammar et al. 2015; Rao et al. 2015), and our implication of PLD activity in ALS pathophysiology, it is conceivable that the PLD pathway plays a more central role in neurodegeneration. It will certainly be worth testing the efficacy of halopemide and FIPI in ALS murine models. Positive results in such experiments, in combination with the human and animal model data described here, could warrant a full-scale clinical development program for halopemide and/or FIPI as ALS therapeutics. However, given the modest benefit in the SOD1G93A mouse model resulting from genetic deletion of the PLD pathway, PLD inhibition alone may not provide significant benefit to patients with ALS. Instead, it is worth considering the possibility that PLD inhibition might be deployed in the context of a combinatorial therapeutic approach in which, for instance, a causative gene is also targeted.

In conclusion, our study highlights the advantages of Drosophila models for the identification of functional circuitries within which individual disease genes are embedded. Drosophila, as well as other invertebrate models, offer unique advantages for the dissection of such circuitries, notwithstanding the fact that observations from these systems must be validated in mammalian/human contexts. Nevertheless, the links we have identified via genetic screens allow us to formulate hypotheses regarding underlying molecular mechanisms that can be tested in preclinical models, offering the possibility to identify novel therapeutic targets or indeed biomarkers of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Angeliki Louvi, Diana M. Ho, and Marc Muskavitch for their valuable comments on the manuscript. We also thank Glenn Doughty, Mark Godek, and Dexter Bidot for providing us with the Exelixis strains and supplying vast amounts of fly food that enabled us to perform the screens. We also appreciate the efforts of Ramiro Massol at the Biogen Imaging Center for his help. The UAS-dPld13 was a generous gift of Dr. Raghu Padinjat. This work was supported by a sponsored research agreement provided to Dr. Artavanis-Tsakonas by Biogen. Dr Artavanis-Tsakonas maintains a visiting scientist role at Biogen and owns Biogen stock.

Footnotes

Supplemental material available at figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.12202580.

Communicating editor: H. Bellen

Literature Cited

- Abe K., Aoki M., Tsuji S., Itoyama Y., Sobue G. et al. , 2017. Safety and efficacy of edaravone in well defined patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 16: 505–512. 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30115-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammar M. R., Thahouly T., Hanauer A., Stegner D., Nieswandt B. et al. , 2015. PLD1 participates in BDNF-induced signalling in cortical neurons. Sci. Rep. 5: 14778 10.1038/srep14778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson M. K., Stahlberg A., Arvidsson Y., Olofsson A., Semb H. et al. , 2008. The multifunctional FUS, EWS and TAF15 proto-oncoproteins show cell type-specific expression patterns and involvement in cell spreading and stress response. BMC Cell Biol. 9: 37 10.1186/1471-2121-9-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai T., Hasegawa M., Akiyama H., Ikeda K., Nonaka T. et al. , 2006. TDP-43 is a component of ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 351: 602–611. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artavanis-Tsakonas S., 2004. Accessing the exelixis collection. Nat. Genet. 36: 207 10.1038/ng1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala Y. M., Zago P., D’Ambrogio A., Xu Y. F., Petrucelli L. et al. , 2008. Structural determinants of the cellular localization and shuttling of TDP-43. J. Cell Sci. 121: 3778–3785. 10.1242/jcs.038950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay Z., Dickson L., Robertson D., Johnson M., Holland P. et al. , 2013. Attenuated PLD1 association and signalling at the H452Y polymorphic form of the 5-HT(2A) receptor. Cell. Signal. 25: 814–821. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Hur V., Denichenko P., Siegfried Z., Maimon A., Krainer A. et al. , 2013. S6K1 alternative splicing modulates its oncogenic activity and regulates mTORC1. Cell Rep. 3: 103–115. 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof J., Bjorklund M., Furger E., Schertel C., Taipale J. et al. , 2013. A versatile platform for creating a comprehensive UAS-ORFeome library in Drosophila. Development 140: 2434–2442. 10.1242/dev.088757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodemann B. O., and White M. A., 2008. Ral GTPases and cancer: linchpin support of the tumorigenic platform. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8: 133–140. 10.1038/nrc2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg L. O., Konrad M., Wruck C., Koch T., Pufe T. et al. , 2008. Involvement of formyl-peptide-receptor-like-1 and phospholipase D in the internalization and signal transduction of amyloid beta 1–42 in glial cells. Neuroscience 156: 266–276. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. H., and Al-Chalabi A., 2017. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 377: 162–172. 10.1056/NEJMra1603471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruntz R. C., Lindsley C. W., and Brown H. A., 2014. Phospholipase D signaling pathways and phosphatidic acid as therapeutic targets in cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 66: 1033–1079. 10.1124/pr.114.009217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunton-Stasyshyn R. K., Saccon R. A., Fratta P., and Fisher E. M., 2015. SOD1 function and its implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis pathology: new and renascent themes. Neuroscientist 21: 519–529. 10.1177/1073858414561795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buratti E., and Baralle F. E., 2001. Characterization and functional implications of the RNA binding properties of nuclear factor TDP-43, a novel splicing regulator of CFTR exon 9. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 36337–36343. 10.1074/jbc.M104236200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne S., Walsh C., Lynch C., Bede P., Elamin M. et al. , 2011. Rate of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 82: 623–627. 10.1136/jnnp.2010.224501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres J. F., and Krainer A. R., 1993. Functional analysis of pre-mRNA splicing factor SF2/ASF structural domains. EMBO J. 12: 4715–4726. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06160.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D., Zhong M., Wang R., Netzer W. J., Shields D. et al. , 2006. Phospholipase D1 corrects impaired betaAPP trafficking and neurite outgrowth in familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked presenilin-1 mutant neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 1936–1940. 10.1073/pnas.0510710103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H. C., Dimlich D. N., Yokokura T., Mukherjee A., Kankel M. W. et al. , 2008. Modeling spinal muscular atrophy in Drosophila. PLoS One 3: e3209 10.1371/journal.pone.0003209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Z., Bennett C. L., Huynh H. M., Blair I. P., Puls I. et al. , 2004. DNA/RNA helicase gene mutations in a form of juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS4). Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74: 1128–1135. 10.1086/421054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Hongu T., Sato T., Zhang Y., Ali W. et al. , 2012. Key roles for the lipid signaling enzyme phospholipase d1 in the tumor microenvironment during tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Sci. Signal. 5: ra79 10.1126/scisignal.2003257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Kankel M. W., Su S. C., Han S. W. S., and Ofengeim D., 2018. Exploring the genetics and non-cell autonomous mechanisms underlying ALS/FTLD. Cell Death Differ. 25: 648–660. 10.1038/s41418-018-0060-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenna R., 2003. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 3497–3500. 10.1093/nar/gkg500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choksi D. K., Roy B., Chatterjee S., Yusuff T., Bakhoum M. F. et al. , 2014. TDP-43 phosphorylation by casein kinase Iε promotes oligomerization and enhances toxicity in vivo. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23: 1025–1035. 10.1093/hmg/ddt498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C. C., Zhang Y., Umoh M. E., Vaughan S. W., Lorenzini I. et al. , 2018. TDP-43 pathology disrupts nuclear pore complexes and nucleocytoplasmic transport in ALS/FTD. Nat. Neurosci. 21: 228–239. 10.1038/s41593-017-0047-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S. Y., Moriyama T., Uezu E., Uezu K., Hirata R. et al. , 1995. Administration of phosphatidylcholine increases brain acetylcholine concentration and improves memory in mice with dementia. J. Nutr. 125: 1484–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]