Objective:

Small-medium enterprises (SMEs) are under-represented in occupational health research. Owner/managers face mental ill-health risks/exacerbating factors including financial stress and long working hours. This study assessed the effectiveness of a workplace mental health and wellbeing intervention specifically for SME owner/managers.

Methods:

Two hundred ninety seven owner/managers of SMEs were recruited and invited to complete a baseline survey assessing their mental health and wellbeing and were then randomly allocated to one of three intervention groups: (1) self-administered, (2) self-administered plus telephone, or (3) an active control condition. After a four-month intervention period they were followed up with a second survey.

Results:

Intention to treat analyses showed a significant decrease in psychological distress for both the active control and the telephone facilitated intervention groups, with the telephone group demonstrating a greater ratio of change.

Conclusion:

The provision of telephone support for self-administered interventions in this context appears warranted.

Keywords: mental health intervention, randomized control trial, small business, small-medium enterprises

Workplace mental health promotion aims to prevent and manage the social and economic costs of highly prevalent mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety within the working population. In addition to considerable social impact, depression and anxiety also incur significant economic costs related to work performance, workplace safety, absenteeism, and early retirement all of which are very costly for the economy.1 Hence, the early identification of symptoms and the encouragement to seek treatment, are important and cost-effective avenues for employers.2 Interventions focused on reducing employees’ experiences of occupational stress, promoting their mental health, and reducing the associated social and economic costs have received recent attention, although their effectiveness remains mixed.3,4 A recently-published review of 10 studies of manager-specific workplace mental health-related interventions found evidence of an effect on pertinent aspects of knowledge, attitudes, and self-reported behavior.5

However, it remains notable that mental health promotion and occupational stress programs are infrequently adopted by small-medium enterprises (SMEs) even though they are the most common work context globally. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has reported that 99.8% of all enterprises in European Union countries were SMEs (under 250 employees), while the figure is 99% in the United States (under 500 employees), and 99% in Japan (under 300 employees).6 Although workplace regulations and healthcare services differ greatly by jurisdiction, the general issue of mental health in the context of small-medium enterprises is a global priority for occupational health. There is an acknowledged paucity of evidence upon which to base mental health intervention strategies for this specific sector.7–11 While it has been noted that SMEs are difficult to engage in research due to owners/managers’ perceived lack of time to participate and a limited budget to implement programs,12,13 the SME sector, is one that continues to be identified as an area where occupational health research must extend its reach.9,14–16

Extant evidence indicates that the owners/managers of SMEs have a high risk of experiencing occupational stress, burnout, and depression.17 This high risk is commonly attributed to financial pressures, social isolation, long work hours, and the lack of a “safety net” of occupational health and human resource management systems.10 Furthermore, Lai et al18 found that quantitative work overload, job insecurity and poor promotion opportunities, good work relationships, and poor communication are strongly associated with job stress in small and medium-sized enterprises. When owners/managers of SMEs are stressed or mentally unwell, it can also have flow on effects to the psychosocial work environment experienced by their employees.6,19

Notwithstanding a moral imperative to improve their quality of working life, engaging SMEs with mental health promotion interventions also provides an important opportunity to reduce the economic burden of disease. Specifically, in addition to the health care resources required for treatment, depression also impacts workers’ behavioral, cognitive, emotional, interpersonal, and physical functioning, leading to excess disability and sickness absence,20 and impaired work ability.21 Consequently, a large proportion of the cost of depression can be attributed to lost work days due to absence and the reduced productivity of individuals who continue working when ill (presenteeism), with estimates of annual costs reaching 44 billion dollars in the United States,22 15.1 billion pounds in the UK,23 and 12.6 billion dollars in Australia.24,25

This paper reports research directly addressing these financial and social costs of employee depression in a field experiment conducted to evaluate the efficacy of an intervention to promote mental health in SME owner/managers. The intervention employed a format tailored specifically for the SME environment, to deliver evidence-based psychological strategies for mental health promotion.

Psychosocial Stressors Commonly Associated With SME Owner/Managers

Consistently long working hours, especially when these hours are a requirement not a preference, are a major risk factor for mental ill-health and are a commonly reported experience for SME owner/managers. Evidence indicates that SMEs managers/owners commonly recognize the advantages of incorporating work–life balance practices in order to address the issue of long work hours and to encourage employee retention (eg, Malik et al).26 The inherent flexibility of SMEs encourages the adoption of a variety of flexible working options for employees, most commonly including part-time work, time off in lieu, staggered working hours, and shift swapping.6

Similarly, the concept of Psychological Capital (PsyCap), a higher-order construct comprised of hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy related to one's work27 is increasingly included within entrepreneur research.28 Research has demonstrated that PsyCap is positively related to wellbeing and job satisfaction and is a malleable resource that is developable via brief training interventions.29 Similar to social and financial capital, psychological capital is considered to be a useful capacity for business success and to also encourage business owners to view their mental health and wellbeing as a business asset.

The Current Research

The primary aim of this research was to develop, deliver, and evaluate a workplace mental health promotion intervention targeting SME owner/managers and gather data regarding feasibility, efficacy, and acceptability to the target population. This research also aimed to compare different types of delivery of the intervention (telephone supported vs self-administered). As noted recently by Hofer et al30 self-administered interventions may be an effective and inexpensive, accessible alternative to therapist-administered psychological interventions. A self-administered intervention format was adopted for this study as initial conversations with SME stakeholders suggested program administration via external workshops would be unsuccessful and on-line access for any web-based administration was unreliable. Specifically, we hypothesized that:

H1: Participants in the intervention groups would report improved mental health post intervention compared with participants in the active control group.

H2: Participants in the telephone supported intervention group would report improved mental health post intervention compared with participants in the self-administered intervention group.

METHOD

Research Design

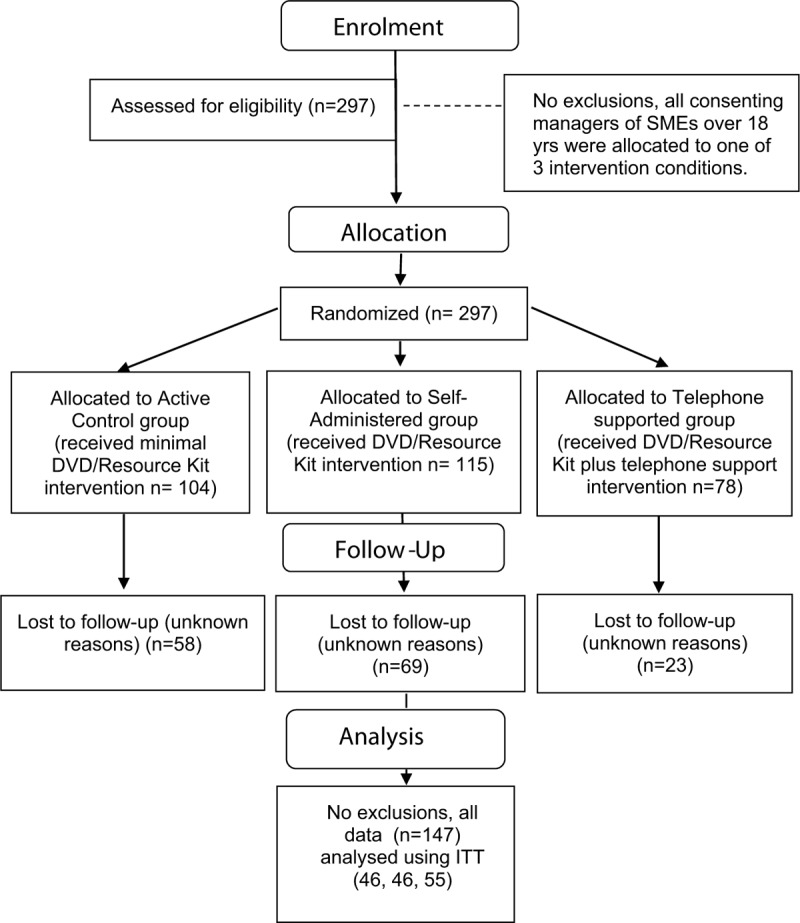

A randomized control research design was employed for the evaluation methodology, with reporting guided by CONSORT and the EHEALTH extension.31 A three-group, pre-post comparison was undertaken with random allocation of participants to the groups. An active control with a wait-list option for full intervention was adopted rather than a “no intervention” control, due to ethical issues and the potential for participant dissatisfaction within any “no intervention” control group to be high. The three groups being compared were: (1) Minimal DVD/Resource Kit (active control group—wait-listed for offer of full intervention after six months); (2) full DVD/Resource Kit (self-administered intervention); and (3) full DVD/Resource Kit + telephone support (self-administered plus telephone-supported intervention).

Recruitment, Sample Size, and Randomization

A target sample size of 250 Australian SME owners/managers was calculated, allowing for three intervention groups, a 20% attrition to follow-up, and sufficient power to detect common effect sizes. Recruitment activities directed potential participants to the project website which contained information about the study (including ethics approved informed consent materials). Participants could register their interest on the website by filling in a registration form that assigned them to our trial management database.

Randomization was by random number generation, and participants were advised via email that they would be mailed the intervention materials, and for the telephone-supported group, that they would be contacted by telephone. Participants were therefore not blind to intervention allocation. Data collection and management activities were co-ordinated through the trial management database, including survey administration and issuing email templates set up for different stages of the trial (welcome e-mails, links to the on-line surveys, or manual processes associated with participants who elected to use hard copy mail surveys).

There were no exclusion criteria and any person who was over 18 years of age and also the owner or manager of a business or non-government organization with less than 250 employees was eligible to participate in the study. A participant incentive was offered at each wave of the survey. If desired, participants could enter an e-mail address at the end of the survey to be entered into a prize draw of a $500 retail voucher.

Participants

The baseline sample recruited into the trial represented owner/managers within a variety of industries including health, service industries, retail, building and construction, transport and finance, businesses of various sizes from zero to 200 employees, and a variety of business types including sole traders, family businesses, partnerships, and trusts. The demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1, according to the intervention group to which they were randomly allocated. The characteristics of participants in each group were similar, but there were minor imbalances in sex, age, and education. Most participants were women, indicating an overrepresentation given that approximately 32% of Australian SMEs owners are women.17 Differences were also present in the industries represented by our sample, with an overrepresentation from the health, building and construction, and retail industries, as compared with a nationally representative sample of SMEs. Each participant was from a different business/organization.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Baseline and Post-Intervention Survey Participants

| Active Control | Self-Admin | Self Admin + Telephone | ||||

| T1% | T2% | T1% | T2% | T1% | T2% | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 43 | 35 | 37 | 41 | 29 | 25 |

| Female | 57 | 65 | 63 | 59 | 71 | 75 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18–39 years | 30 | 28 | 19 | 30 | 19 | 23 |

| 40–49 years | 34 | 35 | 32 | 32 | 47 | 55 |

| 50+ years | 37 | 37 | 28 | 38 | 15 | 21 |

| Education | ||||||

| ≤Year 12 | 14 | 11 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 8 |

| Higher school certificate | 4 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 6 |

| Diploma/associate diploma | 27 | 28 | 20 | 14 | 27 | 27 |

| University | 47 | 43 | 55 | 55 | 49 | 50 |

| Other | 9 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 8 | 8 |

| No. of employees organization | ||||||

| 0 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 17 | 21 |

| 1–19 | 57 | 54 | 51 | 52 | 47 | 49 |

| 20–200+ | 32 | 35 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 30 |

| Type of SME | ||||||

| Not for profit | 16 | 22 | 22 | 20 | 30 | 31 |

| For-profit | 84 | 78 | 78 | 80 | 70 | 69 |

| Hours worked/week | ||||||

| <40 hours | 36 | 46 | 36 | 39 | 42 | 44 |

| >40 hours | 64 | 54 | 64 | 61 | 58 | 56 |

| Business confidence | ||||||

| Low | 26 | 24 | 25 | 23 | 20 | 21 |

| High | 74 | 76 | 75 | 77 | 80 | 79 |

| General health status | ||||||

| Excellent/very good | 73 | 74 | 72 | 73 | 65 | 64 |

| Fair/poor | 27 | 26 | 28 | 27 | 35 | 36 |

SME, small-medium enterprises.

The post-intervention survey (Time 2) was administered to all participants approximately 4 months after intervention completion. Two e-mail reminders and a telephone call were employed to encourage completion of the second survey, resulting in a time lag for many participants which is examined in sensitivity analyses. A total of 147 respondents completed the post-intervention survey, producing a response rate of 49.5%.

Intervention Content

The intervention primarily aimed to educate owner/managers to recognize the signs and symptoms of depression and anxiety in themselves and their employees, and to reduce psychological distress and promote psychological wellbeing. Two versions of the intervention (a self-administered version, and self-administered + telephone support version) were compared with a minimal content version as an active control condition in the trial.

Self-Administered Intervention (Full DVD+Resource Kit)

The intervention consisted of a DVD program (60 minutes duration) and accompanying resource kit “Promoting Mental Health in SMEs.” The intervention aimed to promote mental health focused skills development by integrating evidence-based intervention approaches from multiple fields of psychology (including clinical, health, interpersonal/social, positive, and organizational fields), as well as management and public health research. The DVD consisted of five chapters each focused on a key area for enhancing levels of mental health for SMEs: (1) managing mental health; (2) coping with stress; (3) positive relationships; (4) creating balance; and (5) positive growth. The first chapter was psychoeducational and focused on creating awareness around mental health and its relevance to SMEs. Chapters 2–4 were based on cognitive-behavior therapy concepts and techniques (evidence-based approach to promoting mental health applied to three key issues: coping with stress, positive relationships, and creating balance). Chapter 5 embedded a psychological capital development process shown to increase employee wellbeing and performance,32 but focused on managing challenges in small business (Positive Growth).

The DVD featured real-life case studies of SME owner/managers (not actors) sharing their work experiences and tips for addressing mental health issues in business, and demonstrating their use of mental health promotion strategies and skills. Having information presented by those who are perceived as similar to the targets of the intervention was designed to increase credibility and the face validity of the messages being communicated, to promote role modeling for behavior change, and to embed “therapy content” in the resource kit. Brief segments of interviews from a range of subject matter experts (eg, a mental health NGO representative, management educator, business chamber leader, clinical psychologist, and a general medical practitioner) were also included to establish further credibility in specific areas.

The accompanying Resource Kit comprised a 30 page manual organized in the five chapter themes, with a minimal (10 page) manual for the active control condition covering awareness only. The intervention condition resource kit also included fact sheets, booklets, and posters about depression and anxiety from a national mental health NGO and booklets about preventing workplace stress and bullying from a government workplace safety regulator. The Resource Kit for the intervention (full version) condition included structured tasks and handouts to assist participants to apply the ideas presented in the DVD to their own situations. Intervention chapters (videos and associated resource kit) are available online (www.businessinmind.edu.au).

Self-Administered Intervention Plus Telephone Support

In addition to the program described above, the telephone-facilitated intervention group were offered six, 30-minute calls from a trainee psychologist, spread over the intervention period. The calls aimed to review tasks and content presented in the DVD, and to address any concerns or difficulties participants encountered engaging with and carrying out the related activities. The process was guided by a protocol which prompted recall of DVD content, reviewed resource kit self-directed activities, and provided encouragement and assistance with aspects of mental health the participant identified as an objective.

Brief Psychoeducation DVD as Active Control Condition

The first chapter of the DVD focused on managing mental health and functioned as the active control condition. It was packaged as a brief, stand-alone 15 minute DVD/Kit and contained psychoeducation material but contained no therapeutic content. Progression through the study is depicted in the flow chart in Fig. 1.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow chart.

Measures

Psychological Distress

Mental health was assessed with the Kessler 10 (K10) Screening Scale for Psychological Distress. This 10-item measure asks about the level of anxiety and depressive symptoms a person may have experienced in the last 4 weeks. An example question is: “In the past four weeks, how often did you feel tired out for no good reason.” Respondents indicate their answers on a five-point response scale from none of the time (1), to all of the time (5). Scores are summed, yielding a minimum score of 10 and a maximum score of 50. High scores indicate high levels of psychological distress. High to very high levels of psychological distress (scores above 22) are associated with clinical diagnoses of anxiety and affective disorders.33 These cut-off scores have been adopted in the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) 2001 National Health Survey,34 to estimate levels of psychological distress.35

Psychological Capital

The 12-item version of the PsyCap Inventory assessed positive psychological capacities related to work performance. The PCQ-1236 comprises items for each of the four subscales, including efficacy (three items), hope (four items), resilience (three items), and optimism (two items). Items on the PCQ-12 are rated on a six-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Example items include: I feel confident helping to set targets/goals in my work area (efficacy); I can think of many ways to reach my current work goals (hope); I can get through difficult times at work because I’ve experienced difficulty before (resilience); and I am optimistic about what will happen to me in the future as it pertains to work. Permission to use this measure was obtained from Mind Garden (www.mindgarden.com).

Lost Productive Time

Absenteeism days were measured using an item from the World Health Organizations Health and Work Performance Questionnaires (HPQ): “In the past 4 weeks, on how many days did you miss a whole day of work because of problems with your physical or mental health?” HPQ validation studies show good concordance between measures of self-reported absenteeism and pay-roll records over a 30-day recall period. This recall-based question has also demonstrated a relationship with absenteeism rates for mental disorders.2 Presenteeism was measured with two items validated in an Australian workforce context which included SME participants.21 The first item assessed presenteeism days: “How many days in the last 4 weeks did you got to work while suffering from health problems?” The second item requested a self-reported estimate of lost productive time associated with participants’ reported presenteeism days using 0% to 100% estimate: “On these days, when you went to work suffering from health problems, what percentage of you time were you as productive as usual?” Therefore, the measure of presenteeism days was adjusted by a percent rating of perceived productivity to estimate lost productivity from being at work when unwell.

Acceptability

Participants’ experience of the intervention was assessed with 13 items developed specifically for this study (rated on a seven-point strongly disagree to strongly agree scale). The items are presented along with percentage agreement (by adding five, six, and seven responses) in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Intention-to-Treat Mixed Effects Linear Regression Analysis for Mean Levels of Psychological Distress for the Intervention Groups at Baseline (n = 297) and Post-Intervention (n = 147)

| Intervention Group | Baseline Mean (SE)* | Post-Intervention Mean (SE)* | Change Mean (95%CI)† | Ratio (95% CI)† |

| Active control | 18.2 (0.6) | 16.8 (0.7) | −1.5 (−2.7, −0.2)‡ | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Self-admin. | 18.2 (0.7) | 16.9 (0.8) | −1.3 (−2.9, 0.4) | 0.85 (−0.48, 2.19) |

| Self-admin. + telephone | 17.6 (0.7) | 15.1 (0.7) | −2.5 (−4.1, −0.9)‡ | 1.70 (−0.09, 3.49) |

*Mean (SE), mean (standard error).

†95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

‡Significant difference between baseline and post-intervention (P < 0.05) in log-transformed k10 scores, adjusted for sex, age, and education, and weighted for inverse probability of non-response.

Satisfaction

Participant satisfaction with the intervention was assessed with one item “Overall, I was satisfied with the X DVD and Resource Kit” (one to seven strongly disagree to strongly agree) and this was dichotomized for inclusion in sensitivity analyses (satisfied vs neutral/dissatisfied).

Adherence

Participant adherence with the self-administered nature of the intervention was assessed by asking respondents in the post intervention survey which chapters of the DVD and Resource Kit were watched/read. A partial or full adherence score was coded.

Statistical Analysis

All results were analyzed using an intention-to-treat approach based on the random assignment of registrants to the intervention groups. Linear mixed models fitted by maximum likelihood methods were used to estimate change over time in mean levels of psychological distress (k10 scores) and psychological capital and to compare the changes between the intervention groups (active control, self-administered, self-administered plus telephone). This method accounts for the fact that multiple responses from the same person are more similar than responses from other people.

A logarithmic transformation was applied to the k10 scores, which were right-skewed, and ratios of mean change in scores are presented to compare the active intervention groups with the active control group. The psychological capital values were analyzed without transformation. Covariates were included in the models to adjust for imbalances in sex, age, and education that occurred despite random assignment of participants to the intervention groups.

Data for those who completed follow-up were weighted by the inverse probability of not completing follow-up to account for the missing data of those who did not complete follow-up. This process increases the weight given to data for completers to help account for the missing data of non-completers who are otherwise similar to them and who would be underrepresented in the final sample otherwise. Factors found to predict missing data were the primary reason for engagement with the intervention study being (a) to view the resource or to obtain it for use in workplace education, (b) longer work hours, (c) allocation to the waist-list intervention group, and (d) having had a recent stressful life event.

To inform dissemination, the potential added benefit of the additional telephone support was explored against the additional cost through a cost consequences analysis. This form of comparison is appropriate for complex interventions with a range of health and non-health benefits where benefits are likely to extend beyond the individual (eg, to coworkers).37 Costs were those directly related to intervention delivery method to reflect costs incurred in any subsequent dissemination where each additional user incurs an additional cost. Unit costs for psychologist time for the telephone support were derived from the Australian Psychological Society recommended consultation rate for trainee psychologists, with supervision time from a more experienced psychologist also included.

RESULTS

The intervention was associated with change in the anticipated directions from baseline to post intervention on the two primary measures of this study in both intervention groups. The weighted mean values of psychological distress (k10 score) at baseline and follow-up, the mean change in k10 scores, and the ratio of the change in k10 scores for each of the self-administered and self-administered plus telephone groups, relative to the active control group, are presented in Table 3. Significant reductions in mean levels of psychological distress at follow-up occurred for the active control group (Change [CH] = –1.5; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) –2.7, –0.2, P = 0.02) and the self-administered plus telephone group (CH = –2.5; 95% CI –4.1, –0.9, P = 0.002). The mean change in k10 scores over time was greater for the self-administered + telephone group than for the Active Control group (ratio = 1.69; 95% CI –0.10, 3.48, P = 0.064).

TABLE 3.

Intention-to-Treat Mixed Effects Linear Regression Analysis for Mean Levels of Psychological Capital for the Intervention Groups at Baseline (n = 297) and Post-Intervention (n = 147)

| Intervention Group | Baseline Mean (SE)* | Post-Intervention Mean (SE)* | Change Mean (95% CI)† | Diff (95% CI)† |

| Active control | 51.8 (0.7) | 50.8 (1.0) | −1.0 (−2.7, 0.7) | 0.0 |

| Self-admin. | 51.4 (0.7) | 50.0 (0.9) | −1.4 (−3.3, 0.5) | −0.4 (−2.9, 2.2) |

| Self-admin. + telephone | 51.2 (1.0) | 53.2 (0.9) | 2.0 (−0.4, 4.4) | 3.0 (0.1, 6.0)‡ |

*Mean (SE), mean (standard error).

†95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

‡Significant absolute difference (P < 0.05) between baseline and post-intervention (P < 0.05) in mean change in psychological capital scores. Results were adjusted for sex, age sex and education and weighted for inverse probability of non-response.

Effect size estimates based on mean comparison for k10 Scores were calculated using STATA. We present Hedges g but note Cohen d estimates are almost identical. This difference in psychological distress represents a moderate effect size (0.35; 95% CI –0.054, 0.763) for the active control condition compared to self-administered plus telephone condition.

The weighted mean values of psychological capital at baseline and follow-up, the mean change in psychological capital scores, and the difference the psychological capital scores for each of the research groups relative to the active control group, are presented in Table 4. No significant increases in mean levels of psychological capital at follow-up occurred for any group. Because of the differences in the directions of change in psychological capital in the groups, it was not meaningful to report a ratio of change for psychological capital. However, the relative difference in the change in psychological capital scores over time was greater for the self-administered plus telephone group relative to the Active Control group (difference = 3.0; 95% CI 0.1, 0.1, 6.0, P < 0.05).

TABLE 4.

Descriptive Results for Acceptability Items by Research Group

| % Agreement | |||

| Research Group | SA+ | SA | AC |

| I felt the DVD and Resource Kit met my expectations | 87 | 81 | 67 |

| I would recommend the DVD and Resource Kit to others in a similar situation | 87 | 93 | 92 |

| The formal of a DVD and self-guided resource kit was appropriate for my needs | 83 | 89 | 96 |

| The DVD and Resource Kit had a positive impact on me | 87 | 81 | 83 |

| The DVD and Resource Kit has been helpful to me | 90 | 85 | 79 |

| I felt motivated to make changes as a result of my involvement with the program | 85 | 59 | 73 |

| I put a lot of effort into applying the information in the DVD and Resource Kit | 72 | 59 | 65 |

| I tried out some of the strategies mentioned in the program resources | 79 | 59 | 58 |

| The program has helped me to feel more confident to manage mental health issues in the workplace | 86 | 82 | 79 |

| The program has helped me to improve how I think about or manage mental health issues | 79 | 82 | 71 |

| The program has helped me to take better care of my physical health | 79 | 75 | 75 |

| The program has helped me to be more aware of further supports and how to access them | 79 | 71 | 83 |

| The program has helped me to improve how I managed stress | 75 | 75 | 75 |

Sensitivity Analysis

Given that the time lag between the T1 and T2 surveys was variable, due to delays in participants’ completion of the intervention and/or the post-intervention survey, the analysis was also conducted with a time to follow-up variable. Sensitivity analyses showed that substantive results were unchanged by time to post-intervention assessment.

Participant satisfaction was generally very high in all groups (see Table 4). Although there were no differences between intervention groups for most of the relevant items, telephone group participants were significantly more likely to report “being motivated to make changes as a result of their involvement with X” (P < 0.05), to “try out some of the strategies mentioned in the X resources” (P < 0.04), and to agree that “X has helped me to reduce or manage unhelpful thoughts” (P > 0.02), as compared with the active control group respondents. Sensitivity analyses showed that substantive results were unchanged by the addition of an overall satisfaction variable.

No significant differences in adherence were observed for the self-administered and self-administered + telephone groups (45% full adherence in both intervention groups). A composite adherence score was dichotomized for inclusion in sensitivity analyses (full vs partial engagement with all materials, 39% and 61%, respectively). Sensitivity analyses showed that substantive results were unchanged by the addition of an adherence variable.

DISCUSSION

This study appears to have been one of the first attempts to conduct an RCT of a mental health promotion intervention designed to specifically target SMEs. The first hypothesis was partially supported as the self-administered plus telephone intervention group showed a significant decrease in symptoms of psychological distress at post-intervention, but the self-administered only group did not report significant change. While a reduction in psychological distress symptoms was also observed for the active control group, the ratio of change in the self-administered + telephone intervention group was greater. No effect was observed for any group in relation to increased levels of PsyCap.

Perhaps the result for decreased psychological distress in the active control group is less unexpected than would be seen for “pure” control groups in clinical settings or usual care conditions. Our results suggest that this “minimal dose” of psychoeducation-based intervention may in fact be beneficial. There is some evidence from meta-analytic research that non-guided psychoeducational materials are effective for reducing symptoms of psychological distress in non-clinical and community populations.38

The present study also shows evidence that psychoeducation is beneficial in small business settings. Although far more extensive than what we delivered in the active control condition, when Mental Health First Aid training (a mental health literacy development program) is delivered in work settings, results have shown not only does it reduce stigma of mental illness and increase confidence in discussing mental health, but also reduces psychological distress in participants.39

The second hypothesis was supported as participants in the telephone supported group reported less psychological distress post intervention than participants in the self-administered intervention group and the ratio of change was higher in the telephone supported group than seen in the active control group.

The telephone support was clearly beneficial. The results are consistent with the broader self-help literature for treatment of anxiety and depression. Results from systematic and meta-analytic review indicate that therapist involvement in self-help programs augments the effects of therapy, depending upon the type of disorder being treated.40,41 Therapist guided self-help is associated with greater effectiveness than self-help only interventions for the treatment of depression, especially clinical levels of depression, and for a variety of anxiety disorders.41

The lack of any results demonstrating increased psychological capital post intervention was contrary to expectations. However, this represented only a small part of the intervention (one of the five chapters focused on this). An examination of predictors of engagement with the intervention using baseline data from this study in another paper8 showed that psychological distress, experience of a recent stressful workplace, and low 12-month business confidence were important predictors of engagement. Hence, this finding is possibly due to the fact that PsyCap, as a positive organizational behavior construct, is more focused on wellbeing promotion than distress reduction.

Policy, Practice, and Economic Considerations

The average difference in cost between the telephone-facilitated and self-administered only/active control interventions was $1091 per person. This was based on an average of 3 hours of therapist time, 0.375 hours of therapist supervisor time, 3 hours of participant time, plus telephone call costs and infrastructure (eg, room hire). For this additional cost per person, compared with self-administration alone, a reduction in psychological distress but not psychological capital or lost productive time was observed.

There have been significant outcomes from the project including the initial development of this intervention, a high quality and well-received multimedia resource. Peak bodies in the SME community, our other funding partners and participants alike have responded very positively to this resource. A redevelopment of the materials in an alternative format using online delivery was undertaken by one of the funding partners of the study. International adaptations of the program have been discussed with the Mental Health Commission of Canada and the Mental Health Foundation in the United Kingdom. The DVD program and Resource kit are now freely available online.

Participant feedback on their experiences of the intervention was very positive with the vast majority of participants finding the resources of high quality and utility. The telephone support was very well received and participants in that group reported significantly higher levels of engagement with the program, as shown by higher levels of active experimentation with strategies to improve mental health. This suggests there is a high likelihood of creating real world impact by providing supported implementation of interventions in this sector.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Although we were unable to test all aspects of our theoretical model outlined in our research protocol42 due to a number of pragmatic issues encountered and detailed elsewhere,43 the primary measures of evaluation were still able to be examined. Given there was such a large attrition rate, further follow up after 6 and 12 months did not produce sufficient data for analysis and is thus not reported. In addition, all groups evidenced improvement over time in reduced psychological distress (though not significantly so for the self-administered group). There was also a highly variable time lag between pre and post assessment, although this did not appear to affect the results. This time effect, in combination with the small follow-up numbers and an active control may have meant there was reduced power to detect significant differential treatment effects between groups. Furthermore, while we estimated the cost of providing telephone support, a full cost-benefit analysis, including financial benefits to the business and more broadly to society, was beyond the scope of the current study.

It should also be noted that this trial was not fully blinded and demand characteristics associated with participation in telephone calls could have influenced the results. We used self-reported measures of psychological health rather than diagnostic measures due to the nature of the population of interest (business persons) but these have associated limitations. Finally, the sample with which the intervention was tested was relatively small and not representative on all major characteristics of Australian SMEs, being heavily over-represented by women in both enrollment and retention.

Future studies in this setting may need to consider alternative recruitment/retention strategies and/or methodologies in the investigation of interventions to promote mental health among the working population in SMEs. Larger sample sizes that are more systematically obtained and improved strategies for longitudinal retention may assist in developing this evidence base. A CATI approach to data collection, rather than self-administered online surveys, may better engage and retain participants. Being a pilot study, the project budget did not allow for this but we highly recommend this as an option for future studies with this population.

Although this study suggests there was some benefit to participants in terms of psychological distress reduction, because we have used intention to treat principles in our analysis, we are not able to explicitly state which components of the intervention were more or less effective for those who were more or less distressed at baseline. Future research could be designed to further understand the “what works for whom” question.

Finally, the secondary level evaluation examining relationships between owner/manager mental health and employee psychosocial work environment, and financial benefits to the business, outlined in our trial protocol also remains a research objective to be pursued in future. For example, future research could seek to explore the relationships among mental health promotion interventions and both worker/employee impacts and business outcomes such as job satisfaction, retention and recruitment, absenteeism, presenteeism, safety, and health climates.

CONCLUSION

This study provided initial evidence that symptoms of psychological distress can be reduced through brief and relatively low-cost interventions delivered to SME owner/managers. It represents one of the world's first randomized control trials of a mental health promotion intervention specifically designed for the SME context. Continued investigation of occupational health interventions, such as the one described here, among those working in SMEs is warranted. Such measures have the potential to benefit people and economies worldwide through investment in the health and productivity of the SME workforce.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by an Australian Research Council Linkage Project Grant (LP990010; Industry partners Beyond Blue, Workcover Tasmania, & the Tasmanian Chamber of Commerce and Industry), an Australian Postgraduate Award Industry, a Pro Vice Chancellor Research Strategic Research Scholarship and an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT991524).

The authors also wish to acknowledge the time taken by business owners to participate in this study, organizations that helped with recruitment, and Epix Productions who produced the video content for the DVD. They thank Professor Leigh Blizzard1 for assistance with data analyses.

Footnotes

Registered trial number: ISRCTN 62853520.

Conflict of Interest: No authors have declared a conflict of interest. Authors A.M. and S.D. have declared having undertaken paid consultancy work in 2019 with Workcover Tasmania, one of the funders of the research this paper is based on.

Clinical significance statement: Common mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety are a priority in occupational health, particularly in small business work settings. The results of this study suggest that minimal non-clinical mental health promotion interventions are feasible and beneficial in this population, and that telephone support provides additional value when using a self-administered delivery method.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martin A, Fisher C. Understanding and improving managers’ responses to employee depression. Ind Organ Psychol 2014; 7:270–274. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilton MF, Scuffham PA, Sheridan JS, Cleary CM, Whiteford HA. Mental ill-health and the differential effect of employee type on absenteeism and presenteeism. J Occup Environ Med 2008; 50:1228–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biggs A, Brough P, Barbour JP. Enhancing occupational health and work engagement through leadership development: a quasi-experimental intervention study. Int J Stress Manag 2014; 21:43–68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaMontagne A, Shann C, Martin A. Developing an integrated approach to workplace mental health: a hypothetical conversation with a small business owner. Ann Work Exposur Health 2018; 62:S93–S100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gayed A, Milligan-Saville JS, Nicholas J, et al. Effectiveness of training workplace managers to understand and support the mental health needs of employees: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med 2018; 75:462–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Driscoll MP, Brough P, Haar J. Kelloway EK, Cooper CL. The work-family nexus and small-medium enterprises: implications for worker well-being. Occupational Health and Safety for Small and Medium Sized Enterprises. Cheltenham, UK:Edward Elgar; 2011. 106–128. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biggs A, Brough P, Barbour J. Strategic alignment with organizational priorities and work engagement: a multi-wave analysis. J Organ Behav 2014; 35:301–317. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawkins S, Martin A, Kilpatrick M, Scott J. Reasons for engagement: SME owner-manager motivations for engaging in a workplace mental health and wellbeing intervention. J Occup Environ Med 2018; 60:917–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaMontagne AD, Clare Shann C, Martin A. Developing an integrated approach to workplace mental health: a hypothetical conversation with a small business owner. Ann Work Exposur Health 2018; 62:S93–S100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin A, Sanderson K, Scott J, Brough P. Promoting mental health in small-medium enterprises: an evaluation of the “Business in Mind” program. BMC Public Health 2009; 9:239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szeto A, Dobson K. Reducing the stigma of mental disorders at work: a review of current workplace anti-stigma intervention programs. Appl Prev Psychol 2010; 14:41–56. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eakin JM, Cava M, Smith TV. From theory to practice: a determinants approach to workplace health promotion in small businesses. Health Promot Pract 2001; 2:172–181. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eakin JM, Champoux D, MacEachen E. Health and safety in small workplaces: refocusing upstream. Can J Public Health 2010; 101:29–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindstrom KJ. Commentary IV – work organization interventions in small and medium sized enterprises in Scandinavia. Soc Prev Med 2004; 49:95–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy KR. Glendon AI, Thompson B, Myors B. Organizational psychology's greatest hits and misses: a personal view. Australian Academic Press, Advances in Organizational Psychology. Brisbane:2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martin AJ, LaMontagne AD. Applying the integrated approach to workplace mental health in SMEs: a matter of the “too hard basket” or picking some easy wins? In: Implementing and Evaluating Organizational Interventions. Taylor & Francis; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cocker FM, Martin A, Scott JL, Venn A, Sanderson K. Psychological distress and related work attendance among small-to-medium enterprise owner/managers: literature review and research agenda. Int J Mental Health Promot 2013; 14:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai Y, Saridakis G, Blackburn R. Job stress in the United Kingdom: are small and medium-sized enterprises and large enterprises different? Stress Health 2015; 31:222–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biggs A, Brough P, Barbou JP. Enhancing work-related attitudes and work engagement: a quasi-experimental study of the impact of an organizational intervention. Int J Stress Manag 2014; 21:43–68. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lerner D, Adler DA, Chang H, et al. Unemployment, job retention, and productivity loss among employees with depression. Psychiatr Serv 2004; 55:1371–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanderson K, Tilse E, Nicholson J, Oldenburg B, Graves N. Which presenteeism measures are more sensitive to depression and anxiety? J Affect Disord 2007; 101:65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goetzel RZ, Long SR, Ozminkowski RJ, Hawkins K, Wang S, Lynch W. Health, absence, disability, and presenteeism cost estimates of certain physical and mental health conditions. J Occup Environ Med 2004; 46:398–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bender A, Farvolden P. Depression and the workplace: a progress report. Curr Psychiatry Reps 2008; 10:73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaMontagne A, Sanderson K, Cocker F. Estimating the Economic Benefits of Eliminating Job Strain as a Risk Factor for Depression. Victorian Health Promotion Melbourne, Australia:Foundation (VicHealth); 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cocker F, Sanderson K, LaMontagne AD. Estimating the economic benefits of eliminating job strain as a risk factor for depression. J Occup Environ Med 2017; 59:12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malik F, McKie L, Beattie RS, Hogg G. A toolkit to support human resource practice. Pers Rev 2010; 39:287–307. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luthans F, Youssef CM, Avolio BJ. Psychological Capital. Oxford:Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baron RA, Franklin RJ, Hmieleski KM. Why entrepreneurs often experience low, not high, levels of stress: the joint effects of selection and Psychological Capital. J Manag 2016; 42:742–768. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luthans F, Avey JB, Avolio BJ, Peterson S. The development and resulting performance impact of positive psychological capital. Hum Resourc Dev Quart 2010; 21:41–66. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofer PD, Waadt M, Aschwanden R, et al. Self-help for stress and burnout without therapist contact: an online randomized controlled trial. Work Stress 2018; 32:189–208. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eysenbach G. CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res 2011; 13:e126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luthans F, Avey J, Avolio B, Norman S, Combs G. Psychological capital development: toward a micro-intervention. J Organ Behav 2006; 27:387–393. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10). Aust N Z J Public Health 2001; 25:494–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sunderland M, Slade T, Stewart G, Andrews G. Estimating the prevalence of DSM-IV mental illness in the Australian general population using the Kessler psychological distress scale. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2011; 45:880–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Australian Bureau of Statistics National Health Survey 2017-2018. 2019; Cat. 4364.0.55.001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Avey JB, Avolio BJ, Luthans F. Experimentally analyzing the impact of leader positivity on follower positivity and performance. Leadership Quart 2011; 21:350–364. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNamee P, Murray E, Kelly MP, et al. Designing and undertaking a health economics study of digital health interventions. Am J Prev Med 2016; 51:852–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donker T, Griffiths KM, Cuijpers P, Christensen H. Psychoeducation for depression, anxiety and psychological distress: a meta-analysis. BMC Med 2009; 7:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitchener BA, Jorm AF. Mental health first aid training in a workplace setting: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN13249129]. BMC Psychiatry 2004; 4:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gellatly J, Bower P, Hennessy S, Richards D, Gilbody S, Lovell K. What makes self-help interventions effective in the management of depressive symptoms? Meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychol Med 2007; 37:1217–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newman MG, Szkodny LE, Llera SJ, Przeworski A. A review of technology-assisted self-help and minimal contact therapies for anxiety and depression: is human contact necessary for therapeutic efficacy? Clin Psychol Rev 2011; 31:89–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin A, Sanderson K, Scott J, Brough P. Promoting mental health in small-medium enterprises: an evaluation of the ’Business in Mind’ program. BMC Public Health 2009; 9:239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin A, Kilpatrick MLF, Cocker FM, Sanderson K, Scott JL, Brough P. Karanika-Murray M, Biron C. Recruitment and retention challenges of a mental health promotion intervention targeting small and medium enterprises. Derailed Organizational Stress and Wellbeing Interventions: Confessions of Failure and Solutions for Success. United Kingdom:Springer; 2015. 191–200. [Google Scholar]