Abstract

Objectives

Trauma predisposes to systemic sterile inflammation (SIRS) as well as infection, but the mechanisms linking injury to infection are poorly understood. Mitochondrial debris (MTD) contains formyl peptides (mtFPs). These bind formyl peptide receptor-1 (FPR1), trafficking neutrophils (PMN) to wounds, initiating SIRS and wound healing. Bacterial FPs (bFPs) however, also attract PMN via FPR1. Thus mtFPs might suppress PMN antimicrobial function. Also, FPR1 blockade used to mitigate SIRS might predispose to sepsis. We examined how mtFPs impact PMN functions contributing to antimicrobial responses, and how FPR1 antagonists affect those functions.

Design

Prospective study of human and murine PMN and clinical cohort analysis.

Setting

University research laboratory and Level 1 trauma center.

Patients

Trauma patients, volunteer controls.

Animal subjects

C57Bl/6, FPR1, and FPR2 knockout mice.

Interventions

Human and murine PMN functions were activated with autologous MTD, mtFPs or bFPs followed by chemokines or leukotrienes. The experiments were repeated using FPR1 antagonist cyclosporin H (CsH), ‘designer’ human FPR1 antagonists (POL7178 and POL7200) or anti-FPR1 antibodies. Mouse injury/lung infection model was used to evaluate effect of FPR1 inhibition.

Measurements and Main Results

Human PMN cytosolic calcium, chemotaxis, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and phagocytosis were studied before and after exposure to MTD, mtFPs and bFPs. mtFP and bFPs had similar effects on PMN. Responses to chemokines and leukotrienes were suppressed by prior exposure to FPs. POL7200 and POL7178 were specific antagonists of human FPR1 and more effective than CsH or anti-FPR1 antibodies. FPs inhibited mouse PMN responses to chemokines only if FPR1 was present. FPR1 blockade did not inhibit PMN bacterial phagocytosis or ROS production. CsH increased bacterial clearance in lungs after injury.

Conclusions

FPs both activate and desensitize PMN. FPR1 blockade prevents desensitization, potentially both diminishing SIRS and protecting the host against secondary infection after tissue trauma or primary infection.

Keywords: trauma, mitochondrial DAMPs, neutrophils, FPR1, receptor desensitization, inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Injury releases endogenous “danger associated molecular patterns” (DAMPs), from damaged tissues. These signaling molecules contain molecular motifs normally located inside cells, where they do not interact with immunocytes. When released into the extracellular space however, DAMPs bind to pattern recognition receptors (PRR) on innate immune cells. PRR respond to these primary threats by signals initiating the two major innate immune functions: 1) phagocytosis of dead and damaged tissues that leads to wound healing, and 2) antimicrobial responses that control pathogens.

The signals elicited by DAMPs interacting with PRRs alter host immunity after injury in highly complex ways we refer to as “inflammation”. And whereas some danger signals initiate immune hyper-activation and clinical organ dysfunction, others may decrease responses to pathogenic inoculation, predisposing to clinical infection. The relationships between cellular injury, wound healing and infection are poorly understood.

Mitochondrial formyl peptides (mtFPs) are important DAMPs. After release from dead or injured cells, mtFPs activate professional phagocytes like neutrophils (PMN) via interactions with formyl-peptide receptors (FPR) such as FPR1. FPR1 interaction with mtFPs is almost exclusively responsible for PMN chemotaxis into dying tissues (1–3). Bacteria also bear FP motifs, thus FPR1 is commonly thought critical for phagocytosis of bacteria (4). These dual sources of FPs however, create the possibility that under some conditions wounds and infections may compete for immune resources. We showed that DAMPs generated in injury models, like long-bone fractures and liver-crush, decrease PMN delivery to the lung, decreasing the bacterial inoculum needed to cause pneumonia (5). We have also shown that such competition exists in that cecal-ligation and puncture decreases white blood cell delivery to contused lungs (6).

Here, we confirmed that mtFPs circulated after human injury and examined how PMN antimicrobial activity was affected by their presence. To do this, we synthesized the N-terminal sequence of NADP-dehydrogenase-6 (ND6). ND6 is the most potent human mtFP, and at 100 nM it acts exclusively at FPR1 (7). We studied how mtFPs altered PMN responses to other chemoattractants like chemokines and leukotrienes. We have also defined the effects of a series of human FPR1 antagonists. Last, we investigated how blocking FPR1 can affect critical PMN responses to bacterial invasion after injury.

We employed our established mouse injury model with lung bacterial infection to mimic nosocomial pneumonia after injury in human. We evaluated effects of FPR1 inhibitor, cyclosporin H that rescued bacterial clearance after injury when applied immediately after injury.

Materials and Methods

Compliance

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and animal use committee (IACUC) of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA as well as the equivalent US Armed Forces review organizations (HRPO and ACURO). Written consent was obtained from human blood donors. The care and handling of animals were in accord with National Institutes of Health guidelines for ethical animal treatment. Human mitochondria were isolated from the margins of liver resection specimens (see below) that were not needed for diagnostic purposes. All samples were de-identified.

Human PMN Preparation

PMN were freshly isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy volunteers. Detailed methods are found elsewhere (8). Briefly, PMN were isolated from heparinized whole blood using a one-step centrifugation in 1-Step Polymorphs (AN221725, Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp) that is mentioned by Quach et al. as a preferable method (9). Detailed method can be found in Supplemental Digital Content 1.

Mouse Bone Marrow-Derived PMN Preparation

Mouse bone marrow PMN were isolated from the femurs and tibias of C57/BL6wt, C57/Bl6fpr1−/−), or C57/Bl6fpr2−/−) mice as needed using the methods described elsewhere (10). Details can be found in Supplemental Digital Content 1.

Preparation of Human Mitochondrial Debris (MTD)

Human mitochondria (MT) were prepared from the livers taken from the unused pathologic margins of liver resections obtained during operative procedures performed at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Whole MT were prepared using Mitochondrial Isolation Kit for tissue (89801, Thermo Fisher Scientific). For certain experiments, mitochondrial debris (MTD) fractions were prepared by sonicating purified MT 5–10x for 30 sec as previously described (2). The final concentration of MTD was 3 mg/mL. MTD contains mitochondrial proteins, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and potentially other DAMPs.

Preparation of Human Mitochondrial Formyl Peptides (mtFPs)

N-terminal peptides, whose sequences originate from the 13 human mitochondrial proteins were synthesized by GeneScript (Piscataway, NJ). We have previously investigated the potency of human mtFPs in detail (7) and based on these results in this study we used the most potent peptide, ND6 (fMMYALF).

Measurement of ND6 Levels

To measure levels of ND6 in human plasma, human NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 6 (MT-ND6) ELISA Kit (MBS936598, MyBioSource) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

FPR1 Antagonists

Cyclosporin H (CsH) is a naturally occurring FPR1 antagonist that has activity in humans and mice (2). Sensitivity and specificity of CsH was tested and compared to two novel antagonists, POL7200 and POL7178 that had been designed by Polyphor Ltd. (Allschwil, Switzerland) specifically to block the FP binding site of human FPR1 (Supplemental Figure 2). Anti-human FPR1-specific antibody that inhibits binding site(s) for fMLF and mtDAMPs (5) was also examined (MAB3744, R&D Systems).

PMN Intracellular Calcium Measurements by Spectrofluorometry

Increased concentration of cytosolic calcium ([Ca2+]i) is a critical activator of multiple PMN effector functions. [Ca2+]i was measured by Fura-2 fluorescence (11). Details can be found in Supplemental Digital Content 1.

PMN Chemotaxis

Chemotaxis was studied in transwells [MultiScreen Migration Invasion and Chemotaxis Filter Plates (3.0 μm pore) (Millipore Sigma, MAMIC3S10)] (7). Details can be found in Supplemental Digital Content 1. Primary chemotaxis to each ligand was established and then the effects of antagonists were studied.

Receptor Expression by Flow Cytometry

Membrane expression of FPR1, CXCR2 or BLT1 in human PMN was detected by flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) (12). Details can be found in Supplemental Digital Content 1. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using FlowJo ver. 10 (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR).

Assessment of Phagocytosis

To measure phagocytosis Escherichia coli (E. coli) were labeled using pHrodo phagocytosis particle labeling kits for flow cytometry (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Details can be found in Supplemental Digital Content 1.

Measurement of ROS generation in PMN

We employed two different protocols to measure ROS production by human PMN. 1. Flow cytometry using dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR) staining in experiments with dead Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and fMLF. 2. Luminol-Dependent Chemiluminescence test with live S. aureus (13). Details can be found in Supplemental Digital Content 1.

Effect of CsH on Lung Bacterial Clearance After Injury

We evaluated whether in vivo application of CsH after injury would affect bacterial clearance in lungs by using our established mouse injury model (14). Details can be found in Supplemental Digital Content 1.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were repeated at least five times unless otherwise stated. Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 14 (SAS, Cary, NC). For most experiments, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed followed by Tukey’s post hoc test when the primary ANOVA probability (p) value was <0.05. Student’s t-tests were performed in selected experiments where more appropriate. In all cases a probability p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Clinical injury releases mitochondrial formyl peptides (mtFPs)

Trauma suppresses PMN CXC and BLT receptors in PMN (15). We suspected this phenotypic change reflects exposure to mtFPs. We therefore prospectively sampled plasma from trauma patients with Injury Severity Scores (ISS:21.4 ± 2.9, mean ± SE, n=13) (16) at day 0, 3, 5 after injury and compared with control plasma (n=13) for ND6 levels (Supplemental Figure 1). ND6 is a potent inducer of human PMN Ca2+ release and chemotaxis (7) and reflects the presence of mitochondrial Complex 1, which contains four other chemoattractant mtFPs (7). ND6 concentration was significantly elevated in trauma plasma at 0 day after injury (p=0.0094) compared with volunteers undergoing minor surgery. Exposing PMN to multiple mtFP at plasma concentrations or potentially higher concentrations in injured tissues, or immediately after injury (7) may contribute to changes in PMN phenotype, both by increasing [Ca2+]i and downregulating responses to other agonists.

FPR1 blockade inhibits Ca2+ depletion and chemotaxis in PMN in response to fMLF, MTD and mtFP

The “Gram-negative style” formyl tripeptide, N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl phenylalanine (fMLF) acts exclusively through high-affinity human FPR1 receptors at nanomolar concentrations (17). PMN Ca2+ release from endoplasmic reticulum is a quantitative measure of receptor activation (Supplemental Digital Content 1). We found that several mtFPs are as potent as fMLF and ND6 is even more potent than fMLF (7). We now compared the inhibitory effects of two novel FPR1 antagonists, POL7200 and POL7178 to those of the naturally occurring antagonist CsH (2).

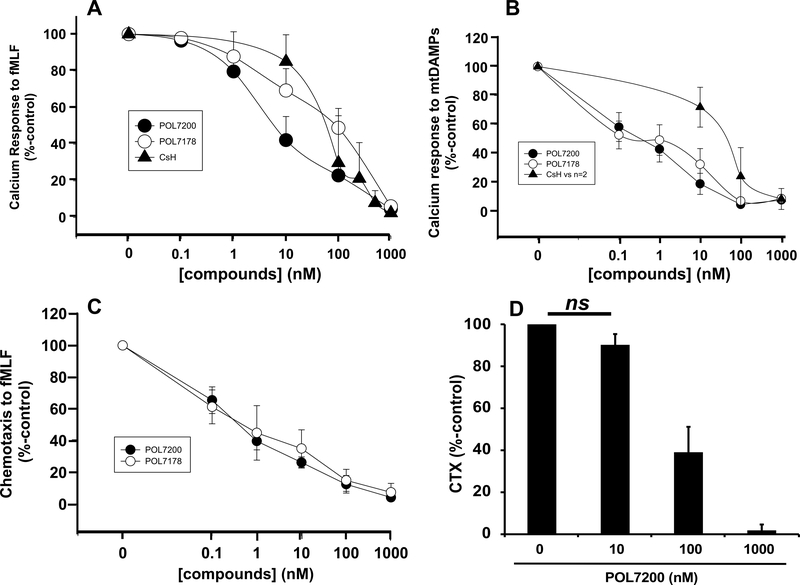

A. Inhibition of fMLF-induced Ca2+ depletion

POL7200 and POL7178 were examined to inhibit 100 nM fMLF-induced human PMN Ca2+ depletion and compared to CsH. Data (Mean ± SE) are presented from six separate experiments in Figure 1A. All three compounds inhibited calcium depletion in a dose-dependent manner. POL7200 was about ten-fold more potent than other compounds. The EC50 values were 8 nM, 80 nM, and 100 nM for POL7200, CsH, and POL7178, respectively.

Figure 1. Effects of FPR1 antagonists on PMN function.

A. Effects of FPR-1 antagonists on fMLF-induced PMN Ca2+depletion from ER. PMN were prepared from six healthy volunteers and stimulated with 100 nM fMLF. fMLF-induced Ca2+ store depletion was studied using Fura-2AM. Responses were assessed as the area under the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) curve for 60 sec after stimulation (AUC60 – see Supplemental Digital Content 1). Dose-dependent inhibition of fMLF-induced Ca2+ depletion was seen in the presence of all three compounds, POL7200, POL7178, and CsH. Effect size was determined by comparing AUC60 for Ca2+ depletion in the presence of antagonists with vehicle (DMSO) assigned as 100%. Values are shown as mean ± SE.

B. Effects of FPR1 antagonists on mtDAMPs-induced Ca2+ depletion from ER. Experiments done as in panel A except that sonicated human MT (mtDAMPs, 30 μg/mL final) prepared from human liver were used as the stimulant. N=5 PMN preparations were used for POL7200 and POL7178. N=2 PMN samples were used for CsH. Mean ± SE values are shown. EC50 for both POL compounds was 0.001–0.01μM. EC50 for CsH was 0.01–0.1μM.

C. Effects of FPR1 antagonists on fMLF-induced chemotaxis (CTX). PMN isolated from healthy volunteers were pre-treated with POL7200 or POL7178 for 15 min at room temperature. 105 PMN were applied to the upper chamber of transwells. The bottom chamber contained 100 nM fMLF. After 60 min migrated PMN were collected and counted by loading them with CyQUANT dye (Materials and Methods, Supplemental Digital Content 1). Effects of FPR1 antagonists on PMN CTX were calculated by comparison to CTX of vehicle-only treated PMN to fMLF, which was established as 100%. Mean ± SE values are shown. N=5.

D. Effect of POL7200 on ND6-induced CTX. PMN were pre-treated with POL7200 as shown. 100 nM ND6 was used as a chemoattractant. Mean ± SE values are shown for six different PMN donors. For each donor each condition was assayed in quadruplicates. The EC50 was about 50 nM. All pairs except “0” and “10 nM” POL7200-treated PMN (ns, not significant) showed significant difference (p<0.001) by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s test.

B. Inhibition of mtDAMPs-induced Ca2+ depletion

mtDAMPs (MTD) isolated from human livers contain all 13 mtFP and model the FP-rich environment of human injury (2). POL7200 and POL7178 inhibited Ca2+ depletion by this complex physiologic agonist (160 μg/mL) in a dose-dependent manner. They shared the EC50 value of 1 nM where that of CsH was about 80 nM (Figure 1B).

C. Inhibition of FP-induced chemotaxis

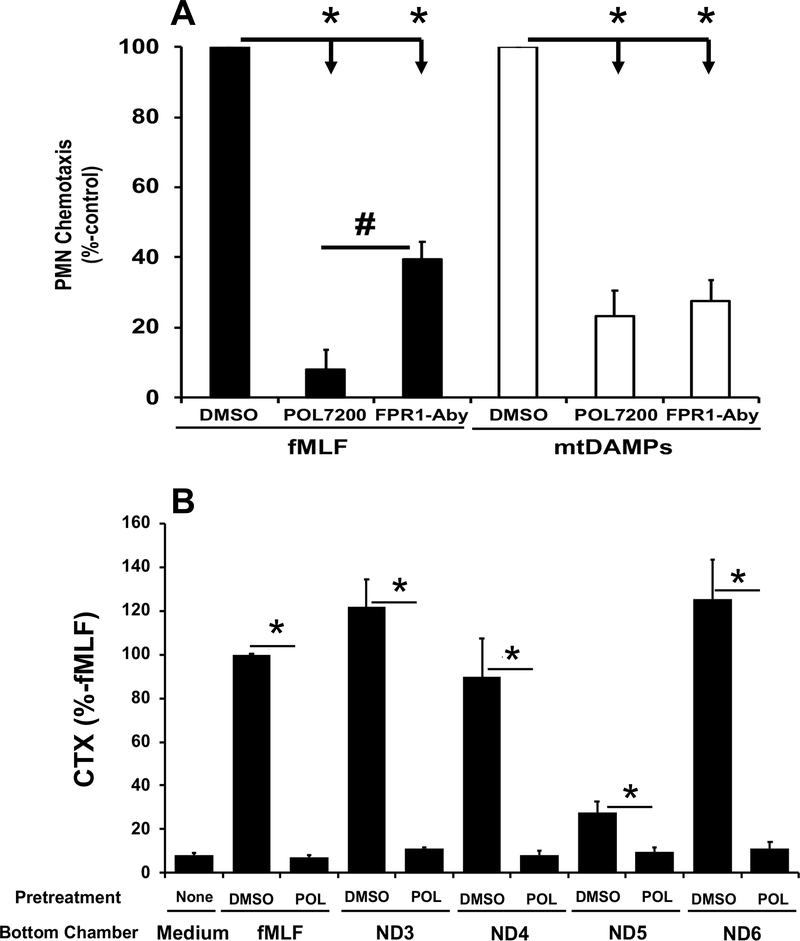

POL7200 and POL7178 inhibition of PMN chemotaxis to fMLF (100 nM) was assessed as percent migration compared to control (DMSO, vehicle-treated) (Figure 1C). FPR1 blockade inhibited chemotaxis to FPR1 agonists at concentrations reflecting inhibition of Ca2+ mobilization. Clinical relevance was shown by the ability of antagonists to block chemotaxis to 100 nM fMLF. Again, inhibition was dose-dependent with complete inhibition at 1 μM POL7200 (Figure 1D). POL7200 inhibition was as effective as anti-FPR1 antibody (MAB3744, R&D Systems) (5) in blocking migration towards sonicated mitochondria (MTD) and was more effective than anti-FPR1 antibody in blocking migration towards fMLF (Figure 2A). POL7200 abolished responses to four active mtFPs, ND3, ND4, ND5, and ND6. (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. POL7200 attenuates mtDAMPs-induced PMN chemotaxis.

A. Inhibition of fMLF/mtDAMPs-induced PMN CTX. PMN isolated from blood of healthy volunteers (n=6) were pretreated with DMSO (vehicle), POL7200 (1 μM) or anti-FPR1-antibody (3 μg/mL) for 15 min at room temperature and 30 min at 37°C, respectively. PMN were applied to the upper chambers and either fMLF (100 nM) or mtDAMPs (150 μg/mL) were placed in the bottom chambers of transwells. PMN migration was evaluated after 60 min as above. Chemotaxis of DMSO-treated PMN was established as 100%. Mean ± SE are shown.

*: p<0.0001, #: p=0.0002 by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s test.

B. Inhibition of mtFP-induced PMN CTX. PMN were pre-treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or POL7200 (1 μM) for 15 min at room temperature and then applied to the upper chambers of transwells. Select mtFP (blockers of FPR1 as described in (7); 100 nM) were applied to the bottom chambers. PMN migration was evaluated after 60 min as above. Data were expressed as migration of treated PMN towards each peptide as a percent of the migration of untreated cells toward that peptide (set as 100%). Data are presented as mean ± SE, n=5–8. Data were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s test. * denotes significant difference, p<0.005.

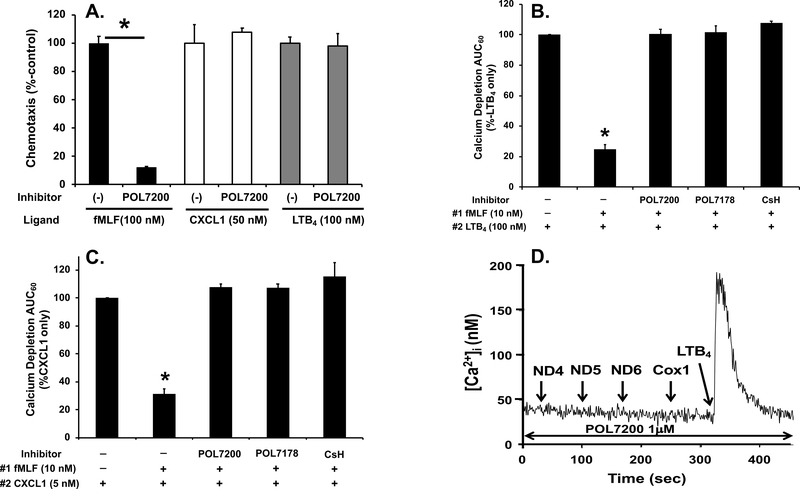

Specificity of FPR1 antagonist, POL7200

To diminish PMN migration towards sterile sites while allowing migration toward infected sites, FPR1 antagonist should be highly specific. To establish specificity of POL7200 we studied their inhibitory effects on other chemoattractant receptors. LTB4 (10 nM) acts through leukotriene B4 receptors 1 and 2 (BLT1/2) (18). At 5 nM, GROα (CXCL1) acts through CXCR2 (19). POL7200 had absolutely no inhibitory effects on GROα- or LTB4-induced PMN migration at those concentrations (Figure 3A). POL7200 was used at 1 μM, a dose that completely inhibits fMLF-induced Ca2+ depletion and migration.

Figure 3. Specific FPR1 inhibition protects function of chemokine receptors.

A. POL7200 specifically inhibits PMN migration to fMLF but not to CXCL1 or LTB4. PMN pre-treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO; presented as (–)) or POL7200 (1 μM) were placed in the upper chambers of transwells and allowed to migrate toward 100 nM fMLF, 50 nM CXCL1 or 100 nM LTB4 placed in the lower chambers for 60 min. Chemotaxis of vehicle-treated PMN toward each chemoattractant was designated as 100%. All experiments were done in quadruplicate. Blank values (spontaneous migration /chemokinesis) were used to correct the results. Data are shown as mean ± SE and are representative of at least three different experiments. POL7200 completely inhibits chemotaxis to fMLF (black bars) but has no effect on chemotaxis toward CXCL1 (white bars) or LTB4 (grey bars).

*: denotes significant difference analyzed by Student’s t-test, p<0.05.

B. Pre-treatment with FPR1 antagonists protects PMN from fMLF-induced heterologous desensitization of BLT1 as analyzed by intracellular calcium depletion. As described in Supplemental Digital Content 1, PMN loaded with Fura-2 were applied to a cuvette and pretreated with 0.1% DMSO (vehicle), 1 μM of POL7200, POL7178, or CsH for 1 min with a constant stirring. Then collection of data was initiated (time 0). At 30 sec, 10 nM fMLF was applied followed by 100 nM LTB4 at 200 sec in the absence of calcium to detect calcium depletion from endoplasmic reticulum. Area under curve for 60 sec (AUC60) after application of LTB4 was calculated and normalized as AUC60 of LTB4-induced depletion from untreated PMN as 100%. Prior treatment with fMLF markedly inhibits Ca2+ flux response to LTB4 but FPR1 blockade by any of the FPR antagonists rescued LTB4 suppression completely. Second column is significantly different from all other columns.

*: denotes significant difference by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s test, p<0.001.

C. Pre-treatment with FPR1 antagonists protects PMN from fMLF-induced heterologous desensitization of CXCR2 by intracellular calcium depletion. Similar experiments (as described in B) were done using 5 nM CXCL1 (GRO-α) that also induces brisk PMN Ca2+ flux. Pre-treatment with fMLF strongly inhibits that response. Again, treatment with all the FPR1 antagonists rescued the CXCR2 response. Second column is significantly different from all other columns. *: denotes significant difference by On-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s test, p<0.001.

D. Effect of POL7200 on active mtFPs-induced calcium depletion. Similarly to B and C, PMN loaded with Fura-2 in cuvette were pretreated with 1 μM POL7200 for 1 min. Then the four most potent mtFPs, ND4, ND5, ND6, and Cox1 (7) were applied successively at 100 nM concentrations. Pre-treatment of PMN with POL7200 abolished Ca2+ flux responses to all the active mtFPs but subsequent Ca2+ response to 10 nM LTB4 was still well-preserved.

FPR1 antagonists protect other receptors from heterologous desensitization

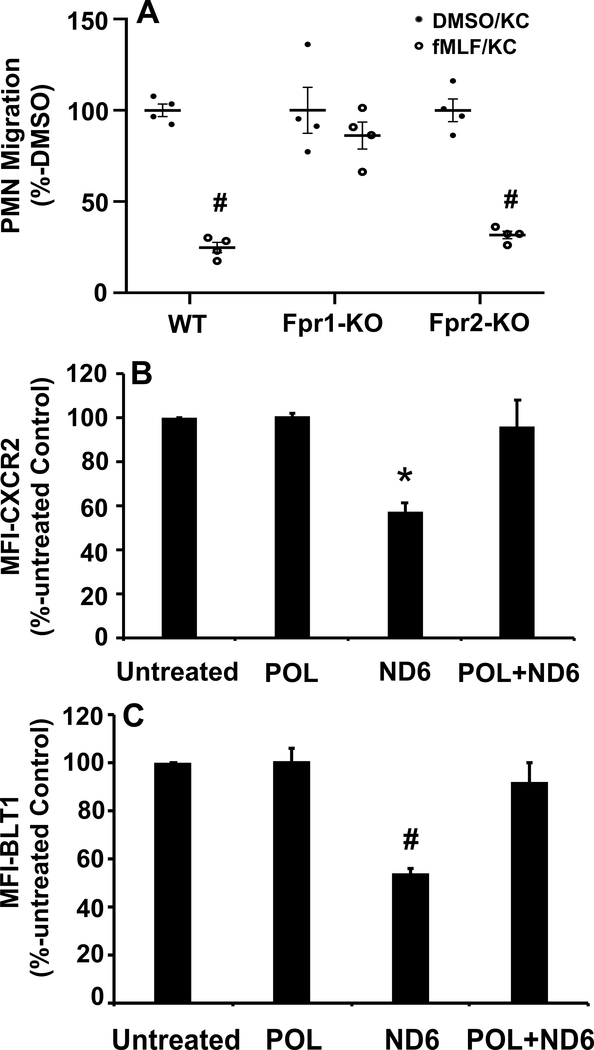

FPR1 ligation causes homologous desensitization of FPR1 and heterologous desensitization of other chemotactic GPCRs (20). We have previously shown that trauma suppresses expression and chemotactic function of CXC and BLT receptors (15). We now examine whether FPR1 antagonists may protect human PMN against heterologous chemotactic receptor desensitization by exposure to fMLF. Pre-exposure of human PMN to 100 nM fMLF significantly reduced calcium depletion by either 100 nM LTB4 (Figure 3B) or 5 nM CXCL1 (Figure 3C). However, inhibition of fMLF binding to FPR1 either by POL7200/POL7178 or by the naturally occurring CsH rescued calcium depletion by LTB4 and CXCL1 (Figures 3B and 3C). Moreover, as seen in Figure 3D, PMN can be serially and repeatedly exposed to active mitochondrial FPs in the presence of POL7200 without losing responses to leukotrienes (here LTB4), like those produced by monocytes in response to bacteria (21–24). Finally, to prove that protection against collateral PMN desensitization by injury-derived mtFPs depends specifically upon FPR1, we performed parallel experiments using PMN from FPR1- and FPR2-knockout mice (KO) and their C57Bl6 wild type background controls. Prior exposure of bone marrow PMN isolated from wild type or fpr2−/− mice (both expressing FPR1) to 100 nM fMLF inhibited migration toward the CXC-chemokine KC while PMN migration to KC persisted in PMN from fpr1−/− (does not express FPR1 but expresses FPR2) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Receptor desensitization by FPs is FPR1-specific.

A. fMLF-induced desensitization is FPR1-specific. Bone marrow-derived neutrophils (BM-PMN) from wild type (WT), Fpr1-KO and Fpr2-KO mice were pre-treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO, black bars) or 1 μM fMLF (gray bars) for 45 min. Cells were then applied to the top chambers of transwells while the bottom chambers contained 100 ng/mL of the mouse CXC-chemokine KC. Experiments were done in quadruplicate. Closed and open circles represent raw data points. PMN were pre-treated with either vehicle (DMSO, closed circle) or with 1 μM fMLF (open circle). PMN migration toward KC for 60 min was compared to migration of vehicle (DMSO)-pretreated cells set as 100%. Mean ± SE values are shown. # denotes significant differences (p<0.05) compared to DMSO-KC by Student’s t-test. Wild type and Fpr2-KO cells (both express FPR1) were desensitized to KC by prior fMLF exposure. On the other hand, Fpr1-KO PMN were protected from chemokine desensitization by exposure to formyl peptides.

B and C. POL7200 rescues ND6-induced heterologous receptor desensitization.

Surface expression of CXCR2 and BLT1 was studied by flow cytometry using specific florescent antibodies and isotype-control antibodies. Human PMN were divided into four groups. 1. Untreated, 2. 1 μM POL7200-treated, 3. 100 nM ND6-treated, and 4. 1 μM POL7200-pretreated, then treated with 100 nM ND6. The mean florescent index (MFI) of unstimulated PMN treated with isotype-control antibody was subtracted from the specific MFI for CXCR2 or BLT1 in all groups. Expression of receptors was normalized to that in untreated PMN, estimated as 100%.

B: Exposure to ND6 significantly reduces expression of CXCR2. However, pretreatment of POL prevented ND6-induced CXCR2 internalization. Mean ± SE values are shown. *: P=0.0046 vs. POL. P=0.005 vs. untreated. P=0.0089 vs. POL+ND6. Statistical analysis was done by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s test.

C: Exposure to ND6 significantly reduces expression of BLT1. Similarly, exposure to ND6 significantly reduced expression of BLT1 that was rescued by pre-exposure to POL7200. (#: p=0.0007 vs. POL, p=0.0008 vs. untreated, p=0.0029 vs. POL+ND6). Mean ± SE is reported for 3 separate experiments. Statistical analysis was done by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s test.

FPR1 surface expression after injury

fMLF causes homologous suppression of FPR1 responses (25) and heterologous suppression of GPCRs like CXCR2 and BLT1/2 (26). In Supplemental Figure 2 we see that POL7200 completely blocks the binding of specific antibody to FPR1, hence lowering fluorescent intensity to that observed for isotype control antibody. We then examined the effect of ND6 (7) on expression of CXCR2 and BLT1 by flow cytometry. ND6 internalized and decreased the surface expression of CXCR2 and BLT1. Prior treatment of PMN with POL7200 however, prevented down regulation of CXCR2 and BLT1 by ND6 (Figures 4B and 4C).

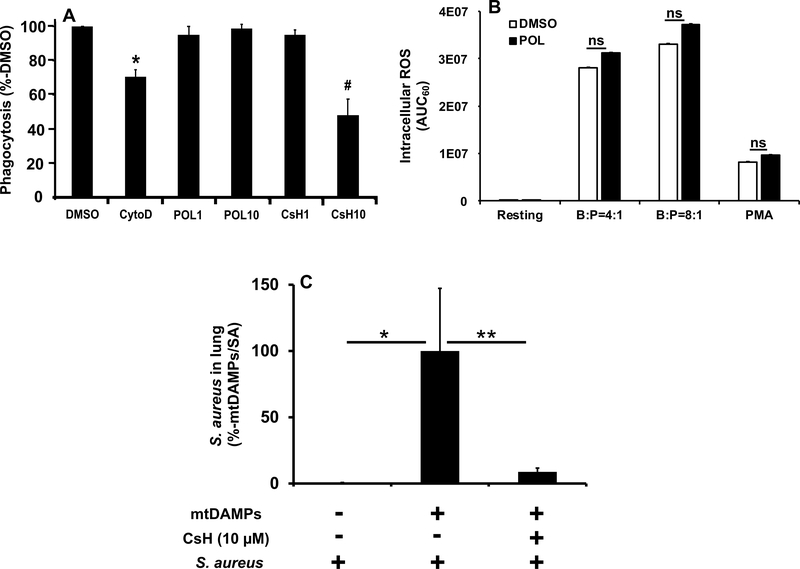

Effect of FPR1 blockade on PMN phagocytosis

Immune cells recognize pathogenic molecules (PAMPs) via PRRs. PMN then engulf bacteria using cytoskeletal contraction. Bacterial peptides are all formylated though, so PMN can also sense bacteria via FPR1. It is unclear however, whether FPR1 is necessary for phagocytosis. If FPR1 is critical for phagocytosis, its blockade after clinical injury might enhance tendencies toward infection and prove deleterious. As shown in Figure 5A however, POL7200 had no measurable effect on PMN bacterial phagocytosis. Conversely, cytochalasin D that disrupts the actin-myosin system (27) and thus served as a positive control here and indeed inhibited PMN phagocytosis. Moreover, CsH was found to inhibit phagocytosis at higher concentrations (10 μM) whereas POL7200 showed no such effects, suggesting that CsH may have off-target effects at a high concentration.

Figure 5. Role of FPR1 in PMN antimicrobial functions.

A: FPR1 role in phagocytosis by PMN. Human PMN were incubated with pHrodo-labeled bacteria (ratio 20:1) for 30 min at 37°C as described in Supplemental Digital Content 1. Control PMN were pretreated with vehicle (1% DMSO). Experimental groups were treated with 10 μg/mL Cytochalasin D, with 1 or 10 μM POL7200, or with 1 or 10 μM CsH. All experiments were repeated using three different PMN preparations. The number of bacteria phagocytosed per PMN was assayed by flow cytometry. Data were normalized to the phagocytosis of bacteria by vehicle-treated PMN (established as 100%). Mean ± SE values are shown. Cytochalasin D was used as a positive control and showed the expected suppression of phagocytosis. FPR1 blocking by POL7200 showed no detectable inhibition of bacterial phagocytosis either at 1 μM (~EC50) or at 10 μM (~EC90)(see Figure 2). 1 μM CsH (~EC20) had no effect on phagocytosis. Unexpectedly, 10 μM CsH (~EC50) significantly decreased phagocytosis. *: p<0.005 vs. all other treatments. #: p<0.0001 vs. all except vs. CytoD (p=0.0412).

B: Effect of POL7200 on S. aureus induced ROS production by human PMN. Details can be found in Supplemental Digital Content 1. PMN were pretreated with 1% DMSO (vehicle) or 10 μM POL7200 for 30 min at 37ºC with rotation. Finally, PMN were loaded with detection reagent mix that contains luminol, superoxide dismutase, and catalase. PMN were then treated with S. aureus at 1:4 and 1:8 ratio, with 500 nM PMA (positive control), or with DPBS+ (vehicle, resting negative control) for 60 min and intracellular ROS production was studied. Area under curve for 60 min was calculated and compared. Mean ± SD values are shown. Data are representative of 3 different experiments. Statistical Analysis was done by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s test.

C: Effect of FPR1-blocking on secondary bacterial infection in lungs after injury in a mouse injury model. C57BL6 mice were divided into three groups as described in Supplemental Digital Content 1. Group 1: controls received S. aureus intratracheally at time 0. Group 2: injury model without treatment. mtDAMPs (equivalent of 10% liver) and DMSO (vehicle) were applied intraperitoneally at time “−3 h” followed by S. aureus administered intratracheally at time “0”. Group 3: treatment group. Similar to Group 2 except that mice received CsH (10 μM final) not DMSO at time “−3 h”. At time “16 h” animals were sacrificed and whole lungs were homogenized in 2 mL saline. Aliquots were applied to agar plates to evaluate bacteria number in lungs. S. aureus in lungs were normalized to Group 2 established as 100%. * and ** denote significant difference, p=0.0439 and p=0.0303, respectively. Statistical analysis was done by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey. Mean ± SE values are shown. Group 1: n=17, Group 2: n=17, Group 3: n=19.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and FPR-1 blockade

PMN kill bacteria by secreting ROS into acidified phagolysosomes. To see if FPR1 blockade interferes with ROS production, we evaluated the effect of FPR1 antagonists on ROS induction by fMLF or Phorbol 12-myristate 13-Acetate (PMA). POL7200 and CsH inhibited fMLF-induced ROS production almost completely (Supplemental Figure 3). PMA bypasses cell-surface GPCRs and increases protein kinase C (PKC) sensitivity to ambient Ca2+ (28). Thus FPR1 blockade suppressed fMLF-induced but not PMA-induced ROS generation (Supplemental Figure 3). Intracellular ROS production by PMN was not affected by FPR1-blockade when PMN encountered live bacteria (Figure 5B).

FPR1-inhibition rescues bacteria-infected lungs after injury

We investigated whether blocking of FPR1 in vivo by administration of CsH would increase bacterial clearance in lungs by using our established mouse injury model. We have applied the amount of S. aureus to lungs of C57BL6 mice that could be cleared by healthy animals. The injury (such as intraperitoneal administration of mtDAMPs) significantly decreased bacterial clearance in mouse lungs compared to not-injured animals (Figure 5C). However, when CsH was administered simultaneously with mtDAMPs, bacterial clearance in lungs was significantly improved (Figure 5C).

DISCUSSION

Injury mobilizes DAMPs into the circulation and injured hosts are susceptible to infection. We have published that CXCR2 expression on PMN was suppressed immediately after injury after a few days and PMN migration was also reduced. This suppression correlated with the increased incident of pneumonia after injury, although we were not aware of mitochondrial DAMPs at the time of this study (15). Here, we investigated the mechanisms that may link mtDAMPs mobilization to decreased bacterial surveillance. One potentially important mechanism of suppression of PMN activity may be blocking of collateral chemotactic receptors by mtFPs. Our results demonstrate that mtFPs are released by injury but while mtFPs attract and activate PMN, simultaneously they suppress PMN chemotaxis towards places where resident monocytes have already encountered bacterial PAMPs. Thus, although counter-intuitive, it may well be that the net effect of FPR1 blockade might improve detection and control of pathogens in clinical conditions.

The POL agents seem highly effective and have no as yet detected off-target effects. CsH has similar effects but is less potent and has readily detectable off-target outcomes. We show that PMN exposure to bacterial FPs (fMLF) as well as mtFPs (in the form of mitochondrial slurry [MTD] or synthetic N-terminal formyl-peptides) all cause rapid desensitization of critical collateral receptors, like CXCR2 and BLT1. Using pharmacologic and genetic methods, and specific blocking antibody our data demonstrate that all these events are mediated by FP engagement of FPR1.

These data provide important insight into prior observations that after trauma, PMN chemotaxis is globally suppressed (15). Moreover, our findings suggest that FPR1-specific blockade might be an effective tool in preserving expression and function of innate immune chemotactic receptors that are suppressed by mtFPs. Hypothetically, prevention of innate receptor suppression might limit predisposition towards bacterial infections at systemic sites like the lung or wounds after major trauma.

The obvious concern using such strategies would be that PMN so treated might fail to become activated, find, ingest and kill bacteria via processes requiring signals through FPR1. We saw no evidence of such drawbacks although these studies are not comprehensive.

Finally, our in vivo study using mouse injury model clearly suggested that FPR1-blocking by CsH after injury rescued secondary bacterial infection in lungs likely by preventing heterologous receptor desensitization. Interestingly, Dorward et al. (29) reported that FPR1 plays an important role in migration of PMN to lungs inoculated with fMIT (fMMYALF) or hydrochloric acid (pH 2.0). What will be released from the infected lungs is the key. In our case, secondary lung infection after injury produces many different chemokines where the role of FPR1 is very limited (unpublished data). On the other hand, FPR1 plays a major role in PMN migration to lung injury caused by fMIT and hydrochloric acid.

In summary, we demonstrate that FPR1 specific blockade prevents PMN chemotactic receptor suppression by mtFPs released during and after tissue trauma. This might constitute an effective approach to preserving PMN function after trauma and thus combating bacterial diseases while limiting the use of antibiotics. In general, anti-FPR1 drugs might be used during the week or so after injury in patients who are on a ventilator and hence are at greatest risk for pneumonia. In addition, PMN play an important role in wound healing that involves PMN migration towards injured sites via FPR1, thus blockage of FPR1 will interfere with this process. Therefore, this potential therapy requires tremendous caution. Clearly, further preclinical studies are required, but it should be understood that mtFPs and their receptors are highly species specific. Thus clinically useful agents may only work in human (or humanized) systems. This will hinder traditional pre-clinical studies and other methods of predicting the clinical effects of therapy may be needed.

CONCLUSIONS

Mitochondria released from injured tissues link trauma, sterile SIRS and infection. Mitochondria and bacteria both contain FPs that activate neutrophils via FPR. FPs can attract PMN but downregulate PMN responses to other important chemoattractants. Here we show that human PMN exposed to mtFPs cease responding to other agonists because FPR1-specific activation internalizes their receptors. This loss of function after injury is prevented by a specific blockade of FPR1. If FPR1 were critical for other anti-microbial functions such blockade might be deleterious. We also show that FPR1 is not absolutely required for PMN bacterial detection, phagocytosis or respiratory burst. Thus highly-specific FPR1 blockade may show promise in traumatic SIRS as an intervention to limit infectious complications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of all members of the Harvard-Longwood (HALO) Trauma Research consortium (US Army CDMRP, W81XWH-16-1-0464) and Dr. Kenneth Swanson at BIDMC for excellent suggestions and additional experiments for revision of our manuscript.

This work was supported by Department of Defense Focused Program Award W81XWH-16-1-0464 (CJH, LEO, MBY) and National Institute of Allergy Infectious Diseases grant 1R03AI35346-01 (KI).

Copyright form disclosure: Dr. Itagaki has a grant from NIAID/National Institutes of Health (NIH), 1R03AI135346-01. Drs. Itagaki, Kaczmarek, Gong, Wang, Gao, and Otterbein received support for article research from the NIH. Dr. Yaffe’s institution received funding from Department of Defense (DoD); he received funding from AAAS Science Signaling and Applied Biomath; and he received support for article research from the DoD. Drs. Gong, Wang, and Gao disclosed government work. Dr. Otterbein received funding from HillHurst Biopharmaceuticals (stock options). Dr. Hauser has a grant from Department of Defense, W81XWH-16-1-0464. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure and Conflicts of Interest: None Declared.

All the work was performed at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Reprints will not be ordered

REFERENCES

- 1.McDonald B, Kubes P. Chemokines: sirens of neutrophil recruitment-but is it just one song? Immunity 2010;33(2):148–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raoof M, Zhang Q, Itagaki K, et al. Mitochondrial peptides are potent immune activators that activate human neutrophils via FPR-1. J Trauma 2010;68(6):1328–1332; discussion 1332–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, et al. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature 2010;464(7285):104–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He HQ, Ye RD. The Formyl Peptide Receptors: Diversity of Ligands and Mechanism for Recognition. Molecules 2017;22(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H, Itagaki K, Sandler N, et al. Mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns from fractures suppress pulmonary immune responses via formyl peptide receptors 1 and 2. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;78(2):272–279; discussion 279–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao C, Itagaki K, Gupta A, et al. Mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns released by abdominal trauma suppress pulmonary immune responses. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;76(5):1222–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaczmarek E, Hauser CJ, Kwon WY, et al. A subset of five human mitochondrial formyl peptides mimics bacterial peptides and functionally deactivates human neutrophils. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2018;85(5):936–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itagaki K, Kannan KB, Livingston DH, et al. Store-operated calcium entry in human neutrophils reflects multiple contributions from independently regulated pathways. J Immunol 2002;168(8):4063–4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quach A, Ferrante A. The Application of Dextran Sedimentation as an Initial Step in Neutrophil Purification Promotes Their Stimulation, due to the Presence of Monocytes. J Immunol Res 2017;2017:1254792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swamydas M, Luo Y, Dorf ME, et al. Isolation of Mouse Neutrophils. Curr Protoc Immunol 2015;110:3 20 21–23 20 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 1985;260(6):3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li SQ, Su N, Gong P, et al. The Expression of Formyl Peptide Receptor 1 is Correlated with Tumor Invasion of Human Colorectal Cancer. Sci Rep 2017;7(1):5918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Junger WG. Measurement of oxidative burst in neutrophils. Methods Mol Biol 2012;844:115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itagaki K, Rica I, Zhang J, et al. Intratracheal instillation of neutrophils rescues bacterial overgrowth initiated by trauma damage-associated molecular patterns. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017;82(5):853–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarlowe MH, Kannan KB, Itagaki K, et al. Inflammatory chemoreceptor cross-talk suppresses leukotriene B4 receptor 1-mediated neutrophil calcium mobilization and chemotaxis after trauma. J Immunol 2003;171(4):2066–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W Jr., et al. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma 1974;14(3):187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorward DA, Lucas CD, Chapman GB, et al. The role of formylated peptides and formyl peptide receptor 1 in governing neutrophil function during acute inflammation. Am J Pathol 2015;185(5):1172–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yokomizo T Two distinct leukotriene B4 receptors, BLT1 and BLT2. J Biochem 2015;157(2):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber C, Kraemer S, Drechsler M, et al. Structural determinants of MIF functions in CXCR2-mediated inflammatory and atherogenic leukocyte recruitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105(42):16278–16283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lammermann T, Kastenmuller W. Concepts of GPCR-controlled navigation in the immune system. Immunol Rev 2019;289(1):205–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castro M, Morgenthaler TI, Hoffman OA, et al. Pneumocystis carinii induces the release of arachidonic acid and its metabolites from alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1993;9(1):73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackenzie RK, Coles GA, Williams JD. The response of human peritoneal macrophages to stimulation with bacteria isolated from episodes of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis. J Infect Dis 1991;163(4):837–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serezani CH, Perrela JH, Russo M, et al. Leukotrienes are essential for the control of Leishmania amazonensis infection and contribute to strain variation in susceptibility. J Immunol 2006;177(5):3201–3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solomkin JS. Neutrophil disorders in burn injury: complement, cytokines, and organ injury. J Trauma 1990;30(12 Suppl):S80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prossnitz ER. Desensitization of N-formylpeptide receptor-mediated activation is dependent upon receptor phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 1997;272(24):15213–15219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Capra V, Accomazzo MR, Gardoni F, et al. A role for inflammatory mediators in heterologous desensitization of CysLT1 receptor in human monocytes. J Lipid Res 2010;51(5):1075–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casella JF, Flanagan MD, Lin S. Cytochalasin D inhibits actin polymerization and induces depolymerization of actin filaments formed during platelet shape change. Nature 1981;293(5830):302–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Regazzi R, Li G, Ullrich S, et al. Different requirements for protein kinase C activation and Ca2+-independent insulin secretion in response to guanine nucleotides. Endogenously generated diacylglycerol requires elevated Ca2+ for kinase C insertion into membranes. J Biol Chem 1989;264(17):9939–9944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorward DA, Lucas CD, Doherty MK, et al. Novel role for endogenous mitochondrial formylated peptide-driven formyl peptide receptor 1 signalling in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Thorax 2017;72(10):928–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.