Abstract

Repetitive behaviors are observed in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Clinically, OCD obsessions are thought to drive repetitive or ritualistic behavior designed to neutralize subjective distress, while restricted repetitive behaviors (RRBs) are theorized to be reward- or sensory-driven. Both behaviors are notably heterogeneous and often assessed with parent- or clinician-report, highlighting the need for multi-informant, multi-method approaches. We evaluated the relationship between parent- and child self-reported OCD symptoms with parent-reported and clinician-indexed RRBs among 92 youth with ASD (ages 7–17 years). Regression analyses controlling for the social communication and interaction component of parent-reported ASD symptoms indicated child self-reported, but not parent-reported, symptoms of OCD were associated with clinician-observed RRBs. Although both parent- and child self-reported OCD symptoms were associated with parent-reported RRBs, the overlap between parent reports of OCD symptoms and RRBs were likely driven by their shared method of parent-reported measurement. Results suggest that children experience RRBs in ways that more closely resemble traditional OCD-like compulsions, whereas their parents view such behaviors as symptoms of ASD. These findings provide guidance for better understanding, distinguishing, and ultimately treating OCD behavior in youth with ASD, and introduce new conceptualizations of the phenotypic overlap between these conditions.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, restricted & repetitive behaviors, obsessive compulsive disorder, comorbidity, school-age children

Restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRBs) are a core diagnostic feature of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These behaviors take many forms and can include both physical expressions, such as repetitive body movements, and behaviors such as restricted interests, or insistence on sameness (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Lewis & Bodfish, 1998). The RRBs associated with ASD sometimes appear outwardly similar to the compulsive behaviors that are hallmark symptoms of other psychiatric conditions such as obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD; Jiujias, Kelley, & Hall, 2017; Spiker, Lin, Van Dyke, & Wood, 2012). Clinically, the subjective experience of distress caused by OCD obsessions is thought to drive repetitive or ritualistic behavior designed to neutralize or diminish unpleasant affect. By contrast, RRBs are theorized to be reward- or sensory-driven, such that engagement in these behaviors may feel pleasant and be stress-relieving (Paula-Pérez, 2013). Both sets of behaviors are notably heterogeneous, leaving open the possibility that within and across disorders, they are motivated by different factors (e.g., emotion regulation, escape/avoidance, reward, sensory needs etc). This heterogeneity complicates assessment efforts and underscores the importance of multi-informant, multi-method approaches for classifying repetitive behaviors. Indeed, it is possible that phenotypic overlap between RRBs and OCD rituals could be due in part to a reliance on parent- and clinician-based assessments to classify observable behaviors, without fully considering what motivates them or how they are subjectively experienced (Leekam, Prior, & Uljarevic, 2011). Integrating information from multiple informants (i.e. parent, clinician, and affected youth) on both observable and subjective experiences of OCD symptoms and RRBs is vital for more effectively disentangling the overlap between these symptoms and informing intervention efforts. Thus, there is a need to account for the contributions of both subjective and observed reports in parsing these sets of repetitive behaviors and better understanding their overlap.

ASD-related RRBs are defined by stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, insistence on sameness, rigid thinking patterns, rituals, and/or restricted interests, while OCD is defined by recurrent distressing intrusive thoughts and corresponding compulsive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Symptoms of both OCD and RRBs include the compulsive need to repeat certain behaviors and the tendency to be inflexible with regards to performing tasks, which can seem outwardly similar to an observer. Indeed, parent report suggests that youth with OCD and ASD engage in similar levels of repetitive movement and sameness behavior, while children with OCD perform more repetitive behaviors focused around routines and rituals (Zandt, Prior, & Kyrios, 2007). Nonetheless, assessment of RRBs and OCD severity in ASD generally relies on parent- and observer-report (Leekam et al., 2011; Postorino et al., 2018; van Steensel, Bögels, & Perrin, 2011).

There are, however, some key observable differences between RRBs in ASD and OCD symptoms. In comparison to individuals with ASD, individuals with OCD tend to have more checking and counting behaviors, whereas individuals with ASD present more ordering and touching behaviors (McDougle, Kresch, Goodman, & Naylor, 1995). RRBs focused around sameness behaviors are consistent in individuals with ASD throughout life, whereas sameness behaviors peak in childhood in individuals with OCD (Zandt et al., 2007). Further, parent report suggests that children with OCD perform more repetitive behaviors focused around routines and rituals (Zandt et al., 2007). Indeed, although there are observable differences between RRBs associated with ASD and OCD symptoms, these differences are difficult for parents and clinicians to identify amongst the more salient overlapping symptoms of each group of behavior.

Traditionally repetitive behaviors in OCD and ASD have been viewed as distinct on the basis of their function (e.g., neutralizing the distress of obsessional thinking in OCD). Relatively little is known about the intersection of OCD rituals and ASD-related RRBs despite the relatively high co-occurrence of these two disorders (Postorino et al., 2017). Half of individuals with ASD meet criteria for a co-morbid anxiety disorder, and 30% of individuals with ASD meet criteria for having more than one anxiety disorder (Ezell et al., 2019). It is estimated that comorbid OCD is prevalent in about 10% of youth with ASD (Lai et al., 2019). Likewise, several recent studies indicate that there may be elevated rates of ASD-related symptoms in both youth and adults with OCD (Arildskov et al., 2016; Wikramanayake et al., 2018). Specifically, RRBs, but not social and communication deficits, were related to OCD severity in youth with OCD (Arildskov et al., 2016), with ASD symptoms clustered in a mostly male subgroup. The robust and bidirectional relationship between symptoms of OCD and RRBs suggests considerable phenotypic overlap between symptoms of OCD. Since OCD symptoms and repetitive behaviors may appear externally similar to observers, without seeking further information as to intrinsic motivators, clinicians may either misattribute the behaviors to the individual’s current ASD diagnosis, when in fact they have co-occurring OCD symptoms, or misdiagnose comorbid OCD when their behavior is consistent with ASD (Postorino et al., 2017).

Some have suggested that this phenotypic overlap may be due partly to ostensibly similar behavior profiles that complicate diagnosis (Jiujias et al., 2017; Postorino et al., 2018). Clinically, the distinction between RRBs and OCD behaviors is thought to stem from whether the behavior is uniformly hedonic in nature (RRBs) or sometimes hedonic, but often times a source of distress itself (OCD). That is, the subjective experience of OCD symptoms should be especially distinct from RRBs. However, similar to OCD-related behaviors, RRBs in individuals with ASD can lead to significant distress when interrupted (Scahill et al., 2014). This suggests that multiple informants may view the same experience differently, particularly when they are unable to access internal experiences that motivate a given behavior. Indeed, previous research has found that informant effects accounted for a significant amount of the variance in the relationship between aggression and RRBs (Keefer et al., 2014). Although inter-rater reliability between parents and children with ASD regarding anxiety disorders is generally poor, youth with ASD who are non-externalizing report fair agreement with their parents regarding OCD symptoms (Storch et al., 2012). This suggests that using a multi-informant assessment may be particularly valuable when evaluating RRBs and their potential overlap with OCD. Nonetheless, limited research has examined how parents and children view these behaviors in a single model while simultaneously considering observer accounts.

Current Study

The goal of this study was to examine the relationship between parent- and child-report of youth OCD symptoms and both clinician-indexed and parent-reported RRBs in a sample of youth with ASD. In order to better isolate the relationships between RRBs and OCD symptoms specifically, the social communication and interaction component of ASD symptoms were controlled for in all analyses. We hypothesized that when controlling for the social communication and interaction component of ASD symptoms, parent-report of OCD symptoms would positively relate to (1a) clinician-observed and (1b) parent-rated RRBs due to parent-report measures capturing outwardly observable similarities in these behaviors. Conversely, when controlling for the social communication and interaction component of ASD symptoms, the relationship between child self-report of OCD symptoms and (2a) clinician-observed as well as (2b) parent-reported RRBs would be attenuated because child report should index the subjective distress component of OCD and internal feelings and motivations, while the behavioral overlap (ASD symptoms) should be attenuated. We also hypothesized that since parent-report measures were used for both ASD and OCD symptoms and RRBs, they would account for the majority of unique variance in (3a) parent-rated RRBs. Likewise, since parents, like clinicians, must infer mental states from behavioral observations of children, we also hypothesized that they would account for the majority of variance in (3b) clinician-rated RRBs.”. This was hypothesized due to common method variance: the principle that using the same method of measurement for both dependent and independent variables can result in inflated relationships (Lindell & Whitney, 2001).

Methods

Participants

Ninety-two youth ages 7–17 years (see Table 1 for demographic and clinical characteristics) recruited from the greater Long Island, NY community participated in this study. Recruitment included digital and print flyers advertising a study for children with and without ASD examining patterns of social interaction in adolescents, as wells as a separate study for children with ASD examining the effects of a social skills intervention. Respondents whose parents reported them to be verbally fluent via a phone screener were eligible for this study, regardless of their ASD status. The Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test-Second Edition (KBIT-2; Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004) was administered to evaluate participants’ verbal comprehension, and thus their ability to complete self-report measures. Participants with IQ less than 70 were excluded from the study due to anticipated difficulty completing questionnaires. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al., 2012) was administered to all participants. Participants were classified as having ASD based on current ADOS-2 criteria (Lord et al., 2012; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample

| n | Percent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male), n (%) | 68 | 73.9% | ||

| Racial/Ethnic Minority, n (%) | 14 | 15.2% | ||

| CASI-5 Obsessions Screening Cutoff (meet criteria) n (%) | 19 | 20.7% | ||

| CASI-5 Compulsions Screening Cutoff (meet criteria) n (%) | 15 | 16.3% | ||

| M | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Age | 12.30 | 2.36 | 7.75 | 17.33 |

| KBIT-2 Standard IQ Score | 104.28 | 15.29 | 71 | 133 |

| SRS-2 Total Score | 74.18 | 11.13 | 47 | 90 |

| SRS-2 SCI Score | 73.95 | 11.01 | 47 | 90 |

| SRS-2 RRB Score | 72.16 | 12.65 | 45 | 90 |

| Child Self-report MASC-2 OCD Symptoms Standard Score | 58.07 | 12.14 | 40 | 88 |

| Parent-report MASC-2 OCD Symptoms Standard Score | 63.17 | 16.13 | 42 | 90 |

| CASI-5 RRB Raw score | 4.41 | 2.79 | 0.00 | 12.00 |

| ADOS-2 RRB Score | 3.02 | 1.50 | 0.00 | 7.00 |

Note. ADOS-2 = Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition; KBIT-2 = Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition; SRS-2 = Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition; SCI = Social Communication and Interaction; RRB = restricted repetitive behavior; MASC-2 = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; CASI-5 = Child & Adolescent Symptom Inventory, Fifth Edition.

Measures

Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test-Second Edition (KBIT-2; Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004).

The KBIT-2 is a standardized verbal and non-verbal intelligence assessment intended for use with individuals aged 4–90. Standard scores are calculated using age-specific norms. The KBIT-2 is commonly used to measure intelligence in ASD populations in research settings (Chang et al., 2014; Ten Eycke & Müller, 2018; Veness et al., 2012).

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al., 2012).

The ADOS-2 is considered to be the gold standard of standardized diagnostic assessments of ASD. The ADOS-2 module 3 is designed for verbally fluent individuals. It consists of a series of social situations that allow for the observation of social behaviors as well as RRBs. Based on the scoring of the ADOS-2, participants receive a classification of autism, ASD, or non-spectrum, as well as a standardized severity score and a RRBs score. The RRBs score includes items of stereotyped or idiosyncratic use of words or phrases, unusual sensory interests in play material, hand, finger, or other complex mannerisms, and excessive interest in unusual or highly specific topics or objects or repetitive behaviors. All ADOS-2 examiners were certified research-reliable in both administration and scoring.

Social Responsiveness Scale – Second Edition (SRS-2; Constantino & Gruber., 2012).

The SRS-2 is a 65-item parent-report survey of the severity of their children’s current ASD symptoms. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1–4, with higher scores suggesting greater impairment. It examines both the presence and the severity of ASD symptoms in five subscales: social awareness, social communication, social cognition, social motivation, and restricted interests and repetitive behaviors. The SRS-2 also has two DSM-5 compatible subscales: restricted interests and repetitive behavior (RRB) in addition to social communication and interaction (SRS-2 SCI). The SRS-2 also has a composite score representative of total severity of current ASD symptoms. The SRS-2 SCI score, composed of all subscales except for restricted interests and repetitive behaviors, was used to represent the parent-reported social component of current ASD symptoms in all regression analyses. The SRS-2 displayed excellent internal consistencies (Cronbach’s α=.95) in this study.

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children – Second Edition (MASC-2; March, 2012).

The MASC-2 is an assessment of anxiety symptoms in youth and has both parent- and self-report versions. Past studies indicate that it exhibits adequate psychometric properties for use in ASD populations (Kaat & Lecavalier, 2015; White et al., 2015; White, Schry, & Maddox, 2012). It includes a subscale of symptoms of Obsessions and Compulsions, which is composed of ten Likert-style items, with higher scores indicating greater impairment. In this study, both the parent-report version (Cronbach’s α=.85) and the self-report version (Cronbach’s α= .87) of the Obsessions and Compulsions subscale of the MASC-2 displayed good internal consistencies.

Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory – Fifth Edition (CASI-5; Gadow & Sprafkin, 2012).

The CASI-5 is a parent-report behavior rating scale of children’s symptoms of behavioral disorders that has demonstrated strong psychometrics in ASD populations (e.g., Kim et al., 2018). The symptoms described in each item are directly derived from the DSM-5. The CASI-5 includes an RRB severity score that is composed of four items that respondents rate from 1 (Never) to 4 (Very Often). This RRB severity score was used to represent parent-reported RRB symptoms in this study. The CASI-5 also includes an OCD screening cutoff which is composed of one item on obsessions and one item on compulsions which respondents also rate on the same scale. These cutoffs indicate if participants meet screening criteria for OCD or not, which was used to estimate the percentage of participants who may meet DSM-5-referenced criteria for OCD in this study. The CASI-5 total ASD severity score displayed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=.85) in this study.

Procedures

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Data were obtained from two larger studies (one assessment and one treatment study; treatment study data included baseline assessment only). In the case of participants who participated in both studies, data collected from the first study they participated in, chronologically, were used. No participants participated in both studies simultaneously.

All participants were administered the ADOS-2 and the KBIT-2. Eligible participants then completed the self-report version of the MASC-2. Parents of eligible participants completed the parent-report version of the MASC-2, as well as the SRS-2, and CASI-5.

Data Analytic Plan

First, we examined the bivariate correlations among the following variables: Parent and child report of OCD Symptoms as measured via MASC-2, parent report of the social communication and interaction component of ASD symptoms (SRS-2 SCI), and parent- (CASI-5) and clinician-indexed RRBs (ADOS-2). Next, we ran hierarchical multiple regression models to test the hypotheses that after controlling for the parent-reported social communication and interaction component of ASD symptoms, parent-report OCD symptoms would relate to (hypothesis 1a) clinician-indexed and (hypothesis 1b) parent-reported RRBs due to similarities in observable behaviors, while the relationship between child-report of OCD symptoms and (hypothesis 2a) clinician-indexed as well as (hypothesis 2b) parent-reported RRBs would be attenuated. Parent-reported social communication and interaction score was entered first in all models (Step 1). Next, either parent- or child self-report OCD symptoms was entered as a predictor (Step 2). We ran four total models including both parent and child reported OCD symptoms as an independent variable and both parent- and clinician-indexed RRBs as the dependent variable. Finally, to test the hypothesis that parent-report measures would account for the majority of unique variance in both (hypothesis 3a) parent-rated RRBs and (3b) clinician-rated RRBs, we conducted commonality analysis for each dependent variable including both parent-and child-report of OCD symptoms as predictors (Zientek & Thompson, 2010).

Commonality analysis produces both unique and shared variance estimates for each individual and combination of predictors in the model to better account for multicollinearity and tease apart the unique contributions of each variable from the shared (including pairwise and multivariable) variance among variables. SPSS version 24.0 was used for primary and post hoc analyses, while the Yhat package (Nimon, Lewis, Kane, & Haynes, 2008) in R was used to calculate unique and common coefficients.

Results

All parent-report measures in this study correlated with each other, but not with ADOS-2 indexed RRBs or child self-report OCD symptoms (MASC-2), both of which only correlated with each other (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parent-Report | MASC-2 OCD Symptoms | 1 | .42*** | .43*** | .43*** | .04 | .17 |

| 2 | CASI-5 RRBs | 1 | .46*** | .60*** | .07 | .06 | ||

| 3 | SRS-2 SCI | 1 | .79*** | −.15 | .04 | |||

| 4 | SRS-2 RRBs | 1 | −.07 | .12 | ||||

| 5 | Self-Report | MASC-2 OCD Symptoms | 1 | .25* | ||||

| 6 | Clinician-Observed | ADOS-2 RRBs | 1 | |||||

Note. MASC-2=Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children - Second Edition, OCD=Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, CASI-5=Child & Adolescent Symptom Inventory – Fifth Edition, RRBs=Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors, SRS-2=Social Responsiveness Scale – Second Edition, ASD=Autism Spectrum Disorder, SCI = Social Communication and Interaction, ADOS-2=Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale – Second Edition.

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.001.

Parent-report OCD Symptoms as Predictors of Clinician Observed and Parent-report RRBs

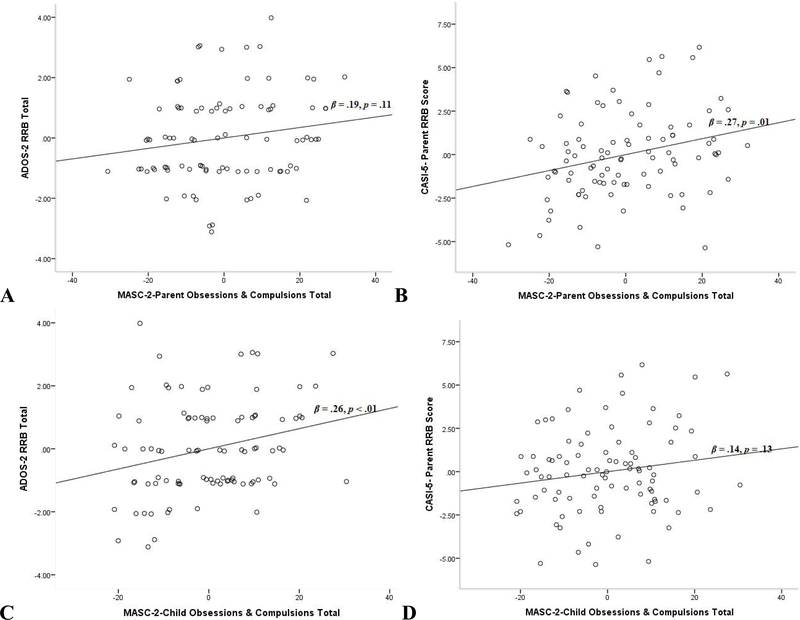

After accounting for the SRS-2 SCI, parent-report of OCD symptoms (MASC-2) did not significantly predict ADOS-2 indexed RRBs on step 2 (see Table 3a; Figure 1A). While controlling for SRS-2 SCI, parent-report OCD symptoms (MASC-2), however, did predict CASI-5 RRBs on step 2 (see Table 3b; Figure 1B) in this model.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Linear Regression of Variables Predicting (a) Clinician-observed and (b) Parent-report RRBs

| B | SE B | β | t | p | R2 | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | |||||||

| P SRS-2 SCI | −.01 | .02 | −.04 | −.33 | .74 | ||

| P MASC-2 OCD | .02 | .01 | .19 | 1.62 | .11 | ||

| .03 | 1.39 | ||||||

| P SRS-2 SCI | .01 | .01 | .08 | .78 | .43 | ||

| C MASC-2 OCD | .03 | .01 | .26 | 2.51 | <.01 | ||

| .07 | 3.24* | ||||||

| (b) | |||||||

| P SRS-2 SCI | .09 | .03 | .35 | 3.49 | <.01 | ||

| P MASC-2 OCD | .05 | .02 | .27 | 2.65 | .01 | ||

| .27 | 16.69*** | ||||||

| P SRS-2 SCI | .12 | .02 | .49 | 5.18 | <.001 | ||

| C MASC-2 OCD | .03 | .02 | .14 | 1.53 | .13 | ||

| .22 | 13.72*** | ||||||

Note: P=Parent-report, C=child self-report, MASC-2=Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children - Second Edition, OCD=Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, RRBs=Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors, SRS-2 =Social Responsiveness Scale – Second Edition, ASD=Autism Spectrum Disorder, SCI = Social Communication and Interaction.

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.001.

Figure 1.

Parent-reported mean-centered OCD symptoms as a predictor of (A) clinician-observed and (B) parent-report RRBs, and self-report mean-centered OCD symptoms as a predictor of (C) clinician-observed and (D) parent-report RRBs

Child Self-report OCD Symptoms as Predictors of Clinician Observed and Parent-report RRBs

When controlling for SRS-2 SCI, child-report of OCD symptoms (MASC-2) significantly predicted ADOS-2 indexed RRBs on step 2 (see Table 3a, Figure 1C. While controlling for SRS-2 SCI, self-report OCD symptoms (MASC-2) also did not predict CASI-5 RRBs on step 2 (see Table 3b, Figure 1D) in this model.

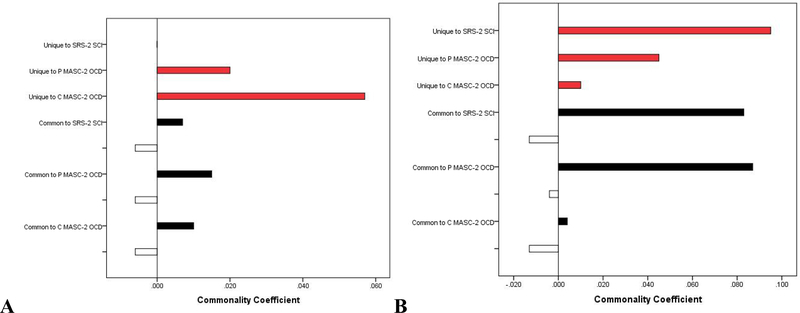

Commonality Analyses

Commonality analyses indicated that child self-reported OCD symptoms (MASC-2) were the largest predictor of ADOS-2 indexed RRBs in this model, uniquely explaining 65.49% of the overall model effect. In this model, 22.69% of the overall model effect was unique to parent-report OCD symptoms (MASC-2), while only 0.10% was unique to SRS-2 SCI (Table 4; Figure 2A).

Table 4.

Commonality Coefficients and Contribution of Predictors and Predictor sets on Clinician-Observed RRBs

| Predictors (x) | P SRS-2 SCI | P MASC-2 OCD | C-MASC-2 OCD | % Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unique to P SRS-2 SCI | <0.001 | 0.10 | ||

| Unique to P MASC-2 OCD | 0.020 | 22.69 | ||

| Unique to C MASC-2 OCD | 0.057 | 65.49 | ||

| Common to P SRS-2 SCI & P MASC-2 OCD | 0.006 | 0.006 | 7.18 | |

| Common to P SRS-2 SCI & C MASC-2 OCD | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.26 | |

| Common to P & C MASC-2 OCD | 0.009 | 0.009 | 9.80 | |

| Common to P SRS-2 SCI & P & C MASC-2 OCD | −0.006 | −0.006 | −0.006 | −6.53 |

| Total | 100 | |||

Note: Values represent commonality coefficients. Commonality coefficients are similar to beta; however they specifically represent the isolated, unique and common variance each individual variable (and combination of variables) contributes to the dependent variable. P=Parent-report, C = child self-report, MASC-2=Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children - Second Edition, OCD=Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, RRBs=Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors, SRS-2 =Social Responsiveness Scale – Second Edition, ASD=Autism Spectrum Disorder, SCI = Social Communication and Interaction, ADOS-2=Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale – Second Edition.

Figure 2.

Unique (red bars) and common regression effects of SRS-2 SCI, parent-report MASC-2 OCD symptoms, and self-report MASC-2 OCD symptoms on (a) clinician-observed ADOS-2 RRBs and (b) parent-report CASI-5 RRBs.

Commonality analyses also indicated the SRS-2 SCI was the best predictor of CASI-5 RRBs in this model, uniquely explaining 42.62% of the overall model effect, while only 20.18% and 4.36% were unique to parent-report OCD symptoms (MASC-2) and self-reported OCD symptoms (MASC-2), respectively (Table 5; Figure 2B).

Table 5.

Commonality Coefficients and Contribution of Predictors and Predictor sets on Parent-Report RRBs

| Predictors (x) | P SRS-2 SCI | P MASC-2 OCD | C-MASC-2 OCD | % Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unique to P SRS-2 SCI | 0.095 | 42.62 | ||

| Unique to P MASC-2 OCD | 0.045 | 20.18 | ||

| Unique to C MASC-2 OCD | 0.010 | 4.36 | ||

| Common to P SRS-2 SCI & P MASC-2 OCD | 0.083 | 0.083 | 37.03 | |

| Common to P SRS-2 SCI & C MASC-2 OCD | −.009 | −.009 | −4.14 | |

| Common to P & S MASC-2 OCD | 0.004 | 0.004 | 1.87 | |

| Common to P SRS-2 SCI & P & C MASC-2 OCD | −0.004 | −0.004 | −0.004 | −1.92 |

| Total | 100 | |||

Note: Values represent commonality coefficients. Commonality coefficients are similar to beta; however they specifically represent the isolated, unique and common variance each individual variable (and combination of variables) contributes to the dependent variable. P=Parent-report, C= child self-report, MASC-2=Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children - Second Edition, OCD=Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, RRBs=Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors, SRS-2 =Social Responsiveness Scale – Second Edition, ASD=Autism Spectrum Disorder, SCI = Social Communication and Interaction, ADOS-2=Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale – Second Edition.

Post-hoc Logistic Regression Models Predicting Individual RRB Items

In order to better understand the relationship between self and parent report OCD symptoms (MASC-2)and RRBs (e.g. were OCD symptoms related to all, or just a subset, of RRB items), post-hoc analyses were run probing which specific types of RRBs drove the aforementioned relationships. Due to the exploratory nature of the post-hoc analyses, we report p values between .05 and .10 as marginally significant. For all significant regression analyses, logistic regression models predicting individual items of CASI-5 and ADOS-2 indexed RRBs, controlling for SRS-2 SCI (on Step 1), and with parent- or self-report OCD symptoms (MASC-2) (on Step 2) as predictors, were run to determine which specific item of the RRB scale contributed to these effects. Due to the ordinal nature of the scoring of the individual items of the RRB subscales of the ADOS-2 and CASI-5, these items were coded as 1 (RRB Present) or 0 (RRB Absent) for the purpose of these analyses. Confidence intervals around odds ratios represent the 95% confidence intervals. Nagelkerke R2 values are provided for significant chi square values.

In terms of the relationship between self-report OCD symptoms (MASC-2) and ADOS-2 indexed RRBs, self-reported OCD symptoms (MASC-2) were marginally significantly associated with the ADOS-2 indexed RRB item “Hand and finger and other complex mannerisms,” χ2(1) = 3.42, p = .064, R2 = .06. Higher self-reported OCD symptoms (MASC-2) were marginally significantly associated with an increased likelihood of exhibiting ADOS-2 indexed complex mannerisms, OR = 1.034 (CI: 0.997, 1.072), p = .070. No other specific RRB items from the ADOS-2 were significant (all ps > .05).

In terms of the relationship between self-report OCD symptoms (MASC-2) and CASI-5 RRBs, self-reported OCD symptoms (MASC-2) were significantly associated with the CASI-5 RRB item “Makes strange repetitive movements (hand flapping, etc),” χ2(1) = 5.93, p = .015, R2= .16. Higher self-reported OCD symptoms (MASC-2)were associated with an increased likelihood of exhibiting CASI-5 indexed complex mannerisms, OR = 1.047 (CI: 1.007, 1.088), p = .020. No other specific RRB items from the CASI-5 were significant (all ps > .05). In terms of the relationship between CASI-5 RRBs and parent-report OCD symptoms (MASC-2), parent-reported OCD symptoms (MASC-2) were significantly associated with the CASI-5 RRB item “Shows excessive preoccupation with one topic,” χ2(1) = 4.73, p = .030, R2 =.21. Higher parent-reported OCD symptoms (MASC-2) were associated with an increased likelihood of exhibiting CASI-5 RRB indexed preoccupation, OR = 1.053 (CI: 1.001, 1.109), p =.047. In addition, OCD symptoms (MASC-2) were significantly associated with the CASI-5 RRB item “Gets very upset over small changes in routine or surroundings,” χ2(1) = 4.65, p =.031, R2 = .274. Higher parent-reported OCD symptoms (MASC-2) were associated with an increased likelihood of exhibiting CASI-5 RRB indexed difficulty with routine change, OR =1.043 (CI: 1.002, 1.086), p = .041. No other specific RRB items from the CASI-5 were significant (all ps > .05).

Discussion

This study was the first to characterize the relationship between parent- and child-reports of youth OCD symptoms and both clinician-observed and parent-reported RRBs in youth with ASD. Results indicated that greater child self-reported, but not parent-reported, symptoms of OCD were associated with greater clinician-observed RRBs. Although both parent- and child self-reported OCD symptoms were associated with parent-reported RRBs, commonality analyses indicated that links between parents’ reports of OCD and their reports of RRBs were mostly driven by common method variance. Overall, this study suggests that children exhibiting objectively-observed RRBs may be experiencing relatively greater levels of subjective distress associated with restricted behavior patterns.

The relationship between parent- and child self-reported OCD symptoms and parent-report and clinician-observed RRBs indicated possible overlap in the phenotypic presentation of RRBs and OCD. This finding aligns with past research that identified OCD as a co-occurring disorder linked with ASD (Ivarsson & Melin, 2008). In fact, parent- and child self-reported OCD symptoms, parent- and clinician observed RRBs, and parent report of the social communication and interaction component of ASD symptoms were all positively correlated with each other, with the exception of child-reported OCD symptoms and parent report of the social communication and interaction component of ASD symptoms. The absence of a relationship between child self-reported OCD symptoms and parent report of the social communication and interaction component of ASD symptoms indicates that what children are reporting as OCD symptoms is a different construct than what their parents are reporting as ASD symptoms. Parents are more likely to report on topographical symptoms (Stewart et al., 2016) and therefore they may view RRBs as observable behaviors attributed to ASD as opposed to behaviors attributed to internal distress from OCD. In fact, parents who report higher levels of RRBs in their children also endorse higher levels of OCD and anxiety in general (Rodgers, Riby, Janes, Connolly, & McConachie, 2012). This is interesting when it is considered that what parents report as OCD symptoms do positively correlate with what they report to be ASD symptoms. This relationship between parent report of the social communication and interaction component of ASD symptoms and parent-report OCD symptoms is potentially due to parents viewing all behaviors as symptoms of ASD, while overlooking the possibility of these behaviors stemming from other comorbid disorders like OCD.

Contrary to our hypotheses, results suggest that child self-reported – but not parent-reported – OCD symptoms most strongly index clinician-observed RRBs after controlling for the parent report of the social communication and interaction component of ASD symptoms. Commonality analyses revealed that self-reported OCD symptoms contributed greater unique variance than parent-reported OCD symptoms in predicting clinician-observed RRBs. This is in contrast with both our hypothesis and previous literature (Lecavalier et al., 2006), which predicted parent-reported OCD symptoms would relate to RRBs. This suggests that for children engaging in repetitive behaviors, the distinction that clinicians draw between behavior designed to relieve distress and those designed to be gratifying may be more difficult to disentangle. This is particularly notable when considering the sorts of behaviors that are typically categorized as RRBs by outside observers, but are categorized as OCD symptoms by child self-report measures. Results found that physical behaviors, (i.e., hand flapping), were seen as RRBs by outside observers, but related to symptoms of OCD by child self-report measures. Thus, children exhibiting objectively observed RRBs may be experiencing relatively greater levels of subjective distress. Anxiety is frequently associated with OCD symptoms (Morgado, Freitas, Bessa, Sousa, & Cerqueira, 2013) rather than RRBs which have been implicated in the reduction of anxiety in children with ASD (Stratis & Lecavalier, 2013). This finding indicates that observers may be missing a necessary feature, the affected individual’s subjective experience of and motivation for their behaviors, in differentiating OCD symptoms from RRBs.

Results suggest that both child self-reported subjective and parent-reported observable OCD symptoms do predict parent-reported RRBs after controlling for parent report of the social communication and interaction component of ASD symptoms. However, commonality coefficients revealed that child self-reported OCD symptoms and parent-reported OCD symptoms did not contribute much to this model, as they each uniquely contributed only 2% and 4% of the regression effect, respectively, when predicting parent-reported RRBs. In fact, the variance common to parent report of the social communication and interaction component of ASD symptoms and parent-report OCD symptoms had the largest effect when predicting parent-reported RRBs (42%). This further suggests that parents may be missing a key feature when distinguishing RRBs from OCD symptoms, and may ultimately just categorize all these behaviors as symptoms of ASD. Child-reported OCD symptoms were predictive, specifically, of parent-reported RRBs associated with repetitive movements, whereas parent-report OCD symptoms were predictive of parent-reported RRBs of restricted interests. Thus, children are reporting that at least some of the behaviors observed by parents and clinicians as physical repetitive movements may be more distressing and related to OCD symptoms than previously thought; however, parents report an association only between restricted interests and OCD symptoms.

A potential explanation for the discrepancy between child-reported OCD symptoms and clinician observed RRBs is diagnostic overshadowing. Diagnostic overshadowing occurs when professionals attribute mental health issues to a person’s disability rather than addressing these issues as separate clinical concerns (Kerns et al., 2015). Therefore, clinicians may have been more likely to attribute RRBs to ASD as opposed to OCD when screening for ASD. In addition to the discrepancy found between participants’ self-report OCD symptoms and clinicians-observed RRBs, may be due to parents also associating their child’s behavior to ASD as opposed to OCD, as noted above. Given that individuals with ASD frequently have impairments in their ability to effectively communicate their feelings (Lord, Cook, Leventhal, & Amaral, 2000), parent and self-report measures may be more discrepant in this population, as parents could have less insight into how their child is feeling when they are engaging in RRBs. This is particularly illuminating given the significance of understanding the subjective experience (i.e., stress relieving or stress inducing) underlying these behaviors as a means to better differentiate if a behavior is an RRB or a symptom of OCD.

Limitations

This study bears several limitations that constrain interpretation. First, participants were recruited from larger studies in a research setting rather than a clinical one, and thus may be different from clinic-ascertained samples. Second, this study did not seek to obtain a subsample of “pure” (no ASD) OCD participants; as such, there was no clinical comparison group of children diagnosed with only OCD.

Third, the presumption that the behaviors assessed on one instrument (e.g., child-report OCD) reflect roughly the same behaviors assessed on another instrument (e.g., clinician-reported RRBs) was also a limitation. For example, we do not explicitly ask a child to rate their experience of stress while engaging in the specific RRBs identified by the clinician administering the ADOS-2. Future research should attempt to more carefully assesses the functional role of RRBs and OCD in modulating affective and sensory experiences.

Fourth, the relationship between self-report OCD symptoms and clinician-reported RRBs may have actually resulted from a limitation of measurement. In completing the MASC-2, it is possible that participants did not understand the constructs that were being examined. Future research should employ multiple instruments and methodologies to achieve greater convergent validity around the assessed constructs, particularly self-reported ones.

Fifth, the sample consisted only of youth with IQ>70, and thus excluded youth with a co-occurring intellectual disability. Excluding this subset of individuals limits the implications of this study, as youth with ASD and co-occurring intellectual disability may experience RRBs and OCD symptoms differently, and account for a large portion of the ASD population (Matson & Shoemaker, 2009). Future research should include methods of measurement that allow for inclusion of individuals with co-occurring intellectual disability. However, we believe that these results highlight a subset of individuals with ASD who are able to accurately report on their experiences, and who are frequently neglected in RRB research.

Sixth, while previous research has consistently used the ADOS-2 clinical cut-offs to classify ASD even in the presence of co-occurring conditions, the use of the ADOS-2 alone may still impact the ecological validity of this study given that clinicians in the community often do not rely on the ADOS-2 for diagnosis. Future research should incorporate clinically-ascertained diagnostic classification to better understand this overlap in a potentially more representative ASD population.

Finally, participants did not receive a thorough clinical evaluation for anxiety-related disorder or OCD. Therefore, it is unclear to what extent these findings will generalize to samples meeting strict thresholds for these disorders. Future research should utilize gold-standard anxiety measures like the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS; Scahill et al., 1997), which has been used in previous research to evaluate repetitive behaviors in ASD (Anagnostou & Taylor, 2011), alongside a formal anxiety diagnostic procedure to further characterize participants’ anxiety-related symptomatology.

Future Directions

This was among the first studies to utilize self-report OCD symptoms as a predictive measure of parent-reported and clinician-observed RRBs. This further implicates a need for mental health professionals to be conscientious of diagnostic overshadowing as a potential barrier when assessing comorbid disorders in ASD. This is particularly important when assessing RRBs in ASD, as clinicians should be aware of the possibility of a comorbid diagnosis of OCD. Future research should focus on refining the clinical distinction between RRBs and OCD, as well as creating an instrument that can assess the difference between RRBs and OCD symptoms in individuals with ASD, specifically. It would be valuable, for instance, to create an instrument that includes the level of stress associated with these symptoms as this can help better differentiate RRBs and OCD symptoms.

Although some earlier research suggests that self-report measures of youth with ASD should be considered with caution (Mazefsky, Kao, & Oswald, 2011), current literature suggests that youth with ASD are in fact able to validly report on their internal experiences (Keith, Jamieson, & Bennetto, 2019). In fact, youth with ASD have been found to accurately identify their anxious cognitions specifically (Ozsivadjian, Hibberd, & Hollocks, 2014). Future research in this area should employ self-report measures to better characterize the intrinsic motivators of these behaviors without requiring inference by observers.

Additionally, future research should investigate if self-reported measures of OCD are still predictive of RRBs in observer-reported measures in more cognitively-impaired individuals with ASD. However, these individuals may likely have a difficult time completing self-report measures or be unable to complete them at all. Thus, it would be valuable to include procedures that have successfully assessed psychiatric comorbidities in youth with ASD more impaired verbal abilities (Lerner et al., 2018).

Conclusion

This study revealed that observed restricted and repetitive behaviors are associated with self-report, but not parent-report, OCD symptoms in youth with ASD. It opens the door to new conceptualizations of the overlap of OCD symptoms and RRBs in ASD by incorporating both the subjective experiences of individuals engaged in these behaviors as well as the perspectives of outside observers (i.e., parents and clinicians). Overall, these results provide guidance for better understanding, distinguishing, and ultimately treating OCD behavior in youth with ASD.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH110585); the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI# 381283); The Brian Wright Memorial Autism Research Fund; and the Stony Brook University Department of Psychiatry Pilot Grant Program. We would like to thank all the participants who provided not only their time but their information and without whom this study would not have been possible. Finally, we would like to thank the research assistants who tirelessly collected and entered data for this project.

Footnotes

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were approved by the Institutional Review Board and were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration or comparable ethical standards.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association. In DSM. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostou E, & Taylor MJ (2011). Review of neuroimaging in autism spectrum disorders: what have we learned and where we go from here. Molecular Autism, 2(1), 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arildskov TW, Højgaard DRMA, Skarphedinsson Gudmundur, S., Thomsen PH, Ivarsson T, Weidle B, … Hybel KA (2016). Subclinical autism spectrum symptoms in pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(1), 711–723. 10.1007/s00787-015-0782-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YC, Laugeson EA, Gantman A, Ellingsen R, Frankel F, & Dillon AR (2014). Predicting treatment success in social skills training for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: The UCLA Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills. Autism, 18(4), 467–470. 10.1177/1362361313478995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, & Gruber CP (2012). Social responsiveness scale–second edition (SRS-2). Torrance: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Ezell J, Hogan A, Fairchild A, Hills K, Klusek J, Abbeduto L, & Roberts J (2019). Prevalence and predictors of anxiety disorders in adolescent and adult males with autism spectrum disorder and fragile X syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(3), 1131–1141. 10.1007/s10803-018-3804-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, & Sprafkin J (2012). The child & adolescent symptom inventory-5 (CASI-5). Checkmate Plus. [Google Scholar]

- Ivarsson T, & Melin K (2008). Autism spectrum traits in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(6), 969–978. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiujias M, Kelley E, & Hall L (2017). Restricted, repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder: A comparative review. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 48(6), 944–959. 10.1007/s10578-017-0717-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaat AJ, & Lecavalier L (2015). Reliability and validity of parent-and child-rated anxiety measures in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 45(10), 3219–3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS, & Kaufman NL (2004). Kaufman brief intelligence test. Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Keefer AJ, Kalb L, Mazurek MO, Kanne SM, Freedman B, & Vasa RA (2014). Methodological considerations when assessing restricted and repetitive behaviors and aggression. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(11), 1527–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith JM, Jamieson JP, & Bennetto L (2019). The importance of adolescent self-report in autism spectrum disorder: Integration of questionnaire and autonomic measures. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(4), 741–754. 10.1007/s10802-018-0455-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Kendall PC, Zickgraf H, Franklin ME, Miller J, & Herrington J (2015). Not to be overshadowed or overlooked: Functional impairments associated with comorbid anxiety disorders in youth with ASD. Behavior Therapy, 46(1), 29–39. 10.1016/j.beth.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Keifer C, Rodriguez-Seijas C, Eaton N, Lerner MD, & Gadow K (2018). Quantifying the optimal structure of the autism phenotype: A comprehensive comparison of dimensional, categorical, and hybrid models. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai MC, Kassee C, Besney R, Bonato S, Hull L, Mandy W, … Ameis SH (2019). Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Available at SSRN: Https://Ssrn.Com/Abstract=3310628. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lecavalier L, Aman MG, Scahill L, McDougle CJ, McCracken JT, & Vitiello B, ... & Cronin P (2006). Validity of the autism diagnostic interview-revised. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 111(3), 199–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leekam SR, Prior MR, & Uljarevic M (2011). Restricted and repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders: A review of research in the last decade. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 562–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner MD, Mazefsky CA, Weber RJ, Transue E, Siegel M, & Gadow KD (2018). Verbal ability and psychiatric symptoms in clinically referred inpatient and outpatient youth with ASD. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 48(11), 3689–3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MH, & Bodfish JW (1998). Repetitive behavior disorders in autism. Mental Retardation & Developmental Disabilities, 89(4), 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lindell MK, & Whitney DJ (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, & Amaral DG (2000). Autism spectrum disorders. Neuron, 28, 355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore P, Risi S, & Gotham K (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule, (ADOS-2) modules 1–4. Los Angeles, California: [Google Scholar]

- March JS (2012). Manual for the nultidimensional anxiety scale for children-(MASC 2). North Tonawanda, NY: MHS. [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, & Shoemaker M (2009). Intellectual disability and its relationship to autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(6), 1107–1114. 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Kao J, & Oswald DP (2011). Preliminary evidence suggesting caution in the use of psychiatric self-report measures with adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 164–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougle CJ, Kresch LE, Goodman WK, & Naylor ST (1995). A case-controlled study of repetitive thoughts and behavior in adults with autistic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(5), 772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgado P, Freitas D, Bessa JM, Sousa N, & Cerqueira JJ (2013). Perceived stress in obsessive-compulsive disorder is related with obsessive but not compulsive symptoms. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 4, 1–6. 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimon K, Lewis M, Kane R, & Haynes RM (2008). An R package to compute commonality coefficients in the multiple regression case: An introduction to the package and a practical example. Behavior Research Methods, 40(2), 457–466. 10.3758/BRM.40.2.457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozsivadjian A, Hibberd C, & Hollocks MJ (2014). Brief report: The use of self-report measures in young people with autism spectrum disorder to access symptoms of anxiety, depression and negative thoughts. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(4), 969–974. 10.1007/s10803-013-1937-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paula-Pérez I (2013). Differential diagnosis between obsessive compulsive disorder and restrictive and repetitive behavioural patterns, activities and interests in autism spectrum disorders. Revista de Psiquiatria y Salud Mental, 6(4), 178–186. 10.1016/j.rpsm.2012.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postorino V, Kerns CM, Vivanti G, Bradshaw J, Siracusano M, & Mazzone L (2017). Anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(12). 10.1007/s11920-017-0846-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postorino V, Kerns CM, Vivanti G, Bradshaw J, Siracusano M, & Mazzone L (2018). Anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 19(12). 10.1007/s11920-017-0846-y.Anxiety [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers J, Riby DM, Janes E, Connolly B, & McConachie H (2012). Anxiety and repetitive behaviours in autism spectrum disorders and Williams syndrome: A cross-syndrome comparison. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(2), 175–180. 10.1007/s10803-011-1225-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Dimitropoulos A, McDougle CJ, Aman MG, Feurer ID, McCracken JT, … Vitiello B (2014). Children’s Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale in autism spectrum disorder: Component structure and correlates of symptom checklist. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 53(1), 97–107. 10.1371/journal.pone.0178059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, & Goodman WK ... Leckman JF (1997). Children’s Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale: reliability and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(6), 844– 852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiker MA, Lin CE, Van Dyke M, & Wood JJ (2012). Restricted interests and anxiety in children with autism. Autism, 16(3), 306–320. 10.1177/1362361311401763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Ehrenreich May J, Wood JJ, Jones AM, De Nadai AS, Lewin AB, …Murphy TK (2012). Multiple informant agreement on the anxiety disorders interview schedule in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 22(4), 292–299. 10.1089/cap.2011.0114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratis EA, & Lecavalier L (2013). Restricted and repetitive behaviors and psychiatric symptoms in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(6), 757–766. 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.02.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ten Eycke KD, & Müller U (2018). Drawing links between the autism cognitive profile and imagination: Executive function and processing bias in imaginative drawings by children with and without autism. Autism, 22(2), 149–160. 10.1177/1362361316668293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steensel FJA, Bögels SM, & Perrin S (2011). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(1), 302–317. 10.1007/s10567-011-0097-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veness C, Prior M, Bavin E, Eadie P, Cini E, & Reilly S (2012). Early indicators of autism spectrum disorders at 12 and 24 months of age: A prospective, longitudinal comparative study. Autism, 16(2), 163–177. 10.1177/1362361311399936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Lerner MD, McLeod BD, Wood JJ, Ginsburg GS, Kerns C, … Compton SC (2015). Anxiety in youth with and without autism spectrum disorder: Examination of factorial equivalence. Behavior Therapy, 46(1), 40–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Schry AR, & Maddox BB (2012). Brief report: The assessment of anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 42(6), 1138–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikramanayake WNM, Mandy W, Shahper S, Kaur S, Kolli S, & Osman S, ... & Fineberg NA (2018). Autism spectrum disorders in adult outpatients with obsessive compulsive disorder in the UK. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 22(1), 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandt F, Prior M, & Kyrios M (2007). Repetitive behaviour in children with high functioning autism and obsessive compulsive disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(2), 251–259. 10.1007/s10803-006-0158-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zientek LR, & Thompson B (2010). Using commonality analysis to quantify contributions that self-efficacy and motivational factors make in mathematics performance. Research in the Schools, 17(1), 1–11. Retrieved from http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=55435493&site=eds-live&scope=site [Google Scholar]