Abstract

Korean American women have substantially greater incidence rates of cervical cancer and the lowest rates of cervical cancer screening in the U.S. However, there has been minimal research to promote HPV vaccination among this population. A pilot randomized controlled trial was conducted to evaluate preliminary effectiveness of a storytelling video intervention using mobile, web-based technology. One hundred and four Korean American college women were randomized to the experimental group (storytelling video) or comparison group (information-based written material). The effects of the intervention were assessed immediately post-intervention and at the 2-month follow-up. Both groups improved in knowledge of and attitude toward the HPV vaccine at the post-intervention. At the 2-month follow-up, the experimental group was twice as likely to receive the HPV vaccine compared to the comparison group. This preliminary evidence supports the use of a storytelling video intervention and shows substantial promise for further development and testing in larger-scale studies.

Keywords: Storytelling video intervention, Mobile Web-Based Technology, HPV vaccination, Korean American college women

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most prevalent sexually transmitted infection in the United States (U.S.) and causes nearly all cervical cancers as well as anogenital and oral cancers in both sexes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2015). In spite of a significant decrease in incidences of cervical cancer (by 75%) due to cervical cancer screening (Adegoke, Kulasingam & Virnig, 2012), Korean American women (11.9 per 100,000) are disproportionately affected by cervical cancer compared to the overall population of women (7.2 per 100,000) in the U.S. (Wang, Carreon, Gomez & Devesa, 2010). In addition, Korean American women were consistently identified as the least likely to receive cervical cancer screenings in the U.S. (Fang et al., 2016). However, HPV-related intervention research that focused on this population is limited.

In our previous qualitative study, Korean American college students preferred a narrative video education that was relevant to their culture and generation (Kim et al., 2017). Narrative or storytelling approaches have been used to enhance health communication and health promotion among racial, ethnic, and minority populations (Allison, et al., 2016, Houston, et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2017). However, there is limited comprehensive knowledge regarding the use of culturally and generationally appropriate narrative/storytelling HPV video educational interventions. Therefore, in this pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT), we assessed the preliminary effectiveness of a previously developed storytelling HPV video intervention leveraging mobile, web-based technology to promote HPV vaccination among Korean American college women in order to provide direction for a future full-scale intervention trial.

Methods

Study Design

All aspects of the study, from data collection to experimentation, were implemented in Qualtrics, an online survey tool that allows users to create and analyze surveys on both mobile and desktop (Qualtric.com). Ethical approval for the procedures of this study was obtained from the PI’s Institutional Reviewed Board (IRB) prior to data collection.

Participants and Recruitment

This study utilized network-based sampling and convenience sampling to recruit participants. To facilitate recruitment, a research theme—“I Want to Know More about the HPV Vaccine”—was utilized. Bilingual flyers with emoticons widely used by young Korean Americans were created. Leaders of Korean Student Associations and pastors of Korean churches served as a pipeline to distribute study information. Outreach was also conducted through social media sites such as Facebook, KakaoTalk (a Korean social networking service), and Korean community websites.

Eligibility criteria were: (1) current undergraduate or graduate female students; (2) resided in the Northeast U.S.; (3) identified as Korean or Korean American; (4) 18–26 years old; (5) could speak or read English; and (6) had not yet been vaccinated against HPV. Potential participants entered the study website to take the eligibility screening survey. If eligible, a link was sent containing an online consent, intervention, baseline and post-intervention survey.

Randomization Procedure

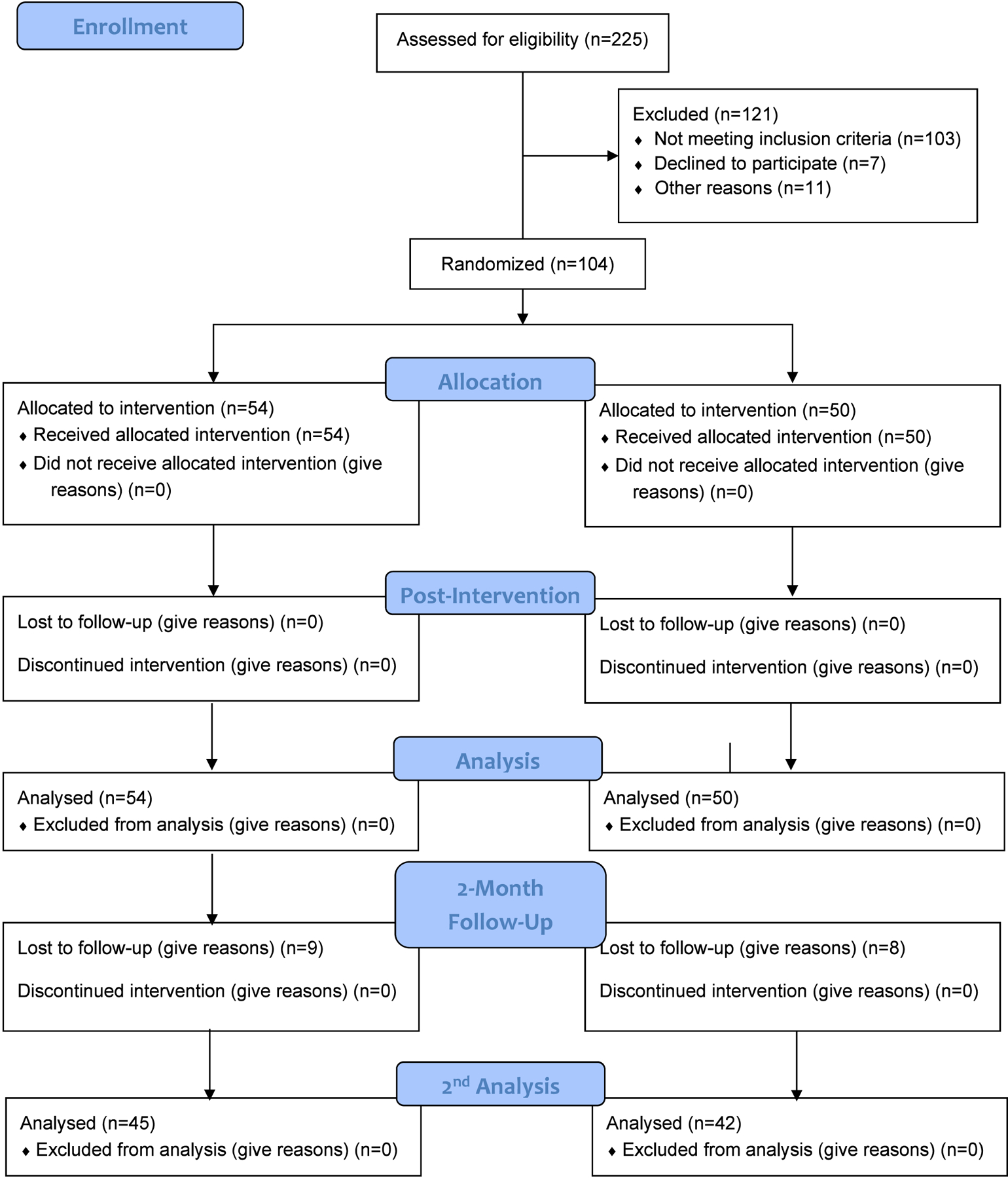

Participants were assigned to either the experimental group (a storytelling video) or comparison group (non-narrative, information-based written material) by simple randomization, using the survey tool (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Experimental Group (Storytelling Intervention)

We developed a storytelling HPV video intervention guided by the situation-specific theoretical framework (Kim et al, 2017) and Storytelling/Narrative Communication (SNC) theory (Lee, Fawcett, & DeMarco, 2016). The situation-specific theoretical framework (Kim et al., 2017) highlights how an individual’s multidimensional attitudes influence their intention and behavior (Kim et al., 2017). SNC theory posits that culturally grounded storytelling affects changes in attitudes and health behaviors through the mechanisms of realism, identification, and transportation (Lee et al., 2016). The storytelling video intervention was about 17 minutes long, featuring three peer-paired cross-cultural and cross-generational (1st, 1.5- and 2nd) stories of Korean American college women’s HPV vaccination experiences and their attitudes toward getting the HPV vaccination. These stories were combined with scientific information—“Learn More”—delivered by a physician to correct Korean American college students’ common misconceptions. (Kim, Lee, Kiang & Allison, 2019).

Comparison Group (Non-Narrative, Information-Based Intervention)

Comparison group participants received seven pages of written information about HPV and the HPV vaccine from the American Cancer Society and the CDC websites, which took 10 to 15 minutes to read completely.

Data Collection

Following online informed consent, participants took a 10- to 15-minute baseline survey prior to the assigned intervention. A post-intervention survey was conducted immediately after to provide evidence of participants’ change in knowledge, attitudes, and intention to receive the HPV vaccine. Two reminders were sent via email prior to the two-month follow-up survey. Individuals who participated in the study received a $20 gift certificate after completing the post-intervention survey. Upon completion of the two-month follow-up survey, participants were entered for a chance to win one of the following: (1) one of three $100 gift cards, (2) one of six $50 gift cards, (3) one of ten $20 gift cards, or (4) one of twenty $10 gift cards.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics were assessed at baseline including age, nativity, age moved to the U.S., academic major, religion, and relationship status. The primary outcome was the initiation of HPV vaccination. Secondary outcomes were changes in knowledge and attitudes.

Knowledge.

Thirty-two items assessed knowledge about HPV (16 items; α = 0.91), HPV vaccine HPV vaccine (8 items; α = 0.82), and cervical cancer (8 items; α = 0.81). Possible responses were “yes,” “no,” or “I don’t know.” An overall knowledge score was calculated as the sum of correct answers. The potential score range was 0–32, with a higher score indicating more knowledge.

Attitudes.

Attitudes were measured by participants’ cognitive, affective, and conative responses toward the HPV vaccine. Cognitive items included perceptions about the HPV vaccine (9 items; α = 0.78). Affective items included direct expression of feelings about getting the HPV vaccine (10 items; α = 0.75). Responses were “yes,” “no,” and “I don’t know.” Responses that were positive toward HPV vaccine received one point. given. Negative responses or “I don’t know,” were given zero points. The potential score range was 0–19, with a higher score indicating more positive attitudes. The conative component of attitude refers to motivational factors (e.g., intention) that influence an actual action or behavior measured by the questions: “Do you intend to get vaccinated against HPV?” (Yes/No/I don’t know).

HPV vaccination.

The primary outcome of HPV vaccine uptake was assessed at the two-month follow-up with the question: “Have you received any HPV vaccine?” (Yes/No/I’m waiting to obtain the vaccine or already scheduled for vaccination).

Sample size

Teare et al. (2014), whose work examined appropriate pilot sample size suggest a total of 60 to 100 subjects per group in pilot RCT studies to increase retention rates and improve the validity of study findings. Per this suggestion, the research team aimed to recruit a sample of 120 participants (60 in each group).

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics were compared by randomized treatment assignment. Although the focus of pilot trials should be on descriptive statistics and estimation, we used a Fisher’s exact test to examine the potential effects of the intervention on HPV vaccine uptake between the two groups. The percent change was calculated from baseline to post-intervention for intention to receive HPV vaccine. A paired t-test was applied to assess mean changes in knowledge and cognitive and affective attitudes toward HPV vaccine from baseline to post-intervention. Mean changes of knowledge score and cognitive and affective attitude score were compared between groups by performing independent t-test. Analyses of treatment effects were based on the intention-to-treat principle. All participants who were randomized and completed follow-up were analyzed according to their original assignment, regardless of their adherence to the protocol. All analyses were conducted with SPSS version 21 (IBM).

Results

The sample ranged in age from 18 to 26 years (M = 21.7, SD = 2.3). The majority of students were in an undergraduate program (73.1%), non-health-related major (61.5%), Christian (75.0%), and currently not in a relationship (65.4%). The majority of participants (77.9%) were born in South Korea, with 67.9% of participants immigrating or migrating to the U.S. before the age of 18 (M= 10.8 years, SD=7.45, Range: 1–26 years) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociocultural Demographic Characteristics of 104 Korean Female College Students

| Experimental (n=54) N(%) or M ± SD | Comparison (n=50) N(%) or M ± SD | Total (n=104) N(%) or M ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (range: 18–26) | 21.5 ± 2.22 | 22.0 ± 2.45 | 21.7 ± 2.34 |

| Nativity (n=102) | |||

| South Korea | 43 (81.1) | 38 (77.6) | 81 (79.4) |

| USA | 10 (18.9) | 11 (22.4) | 21 (20.6) |

| Age Moved to the U.S. (n=81)a | |||

| Under 18 years old | 27 (64.3) | 28 (71.8) | 55 (67.9) |

| 18 years or older | 15 (35.7) | 11 (28.2) | 26 (32.1) |

| Major | |||

| Non-health related | 34 (63.0) | 30 (60.0) | 64 (61.5) |

| Health-related | 20 (37.0) | 20 (40.0) | 40 (38.5) |

| Religion (n=103) | |||

| Buddhist | 3 (5.6) | 1 (2.0) | 4 (3.9) |

| Catholic | 14 (25.9) | 17 (34.7) | 31 (30.1) |

| Protestant | 27 (50.0) | 20 (40.8) | 47 (45.6) |

| None | 10 (18.5) | 11 (22.4) | 21 (20.4) |

| Relationship status | |||

| Not in a relationship | 36 (66.7) | 32 (64.0) | 68 (65.4) |

| In a relationship | 18 (33.3) | 18 (36.0) | 36 (34.6) |

Note: M=mean, SD=Standard Deviation

participants who were born in South Korea

At the two-month follow-up, ten participants (22.2%) reported having received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine or having already scheduled the vaccination. The experimental group was twice as likely to report receiving HPV vaccination, or scheduling an appointment for the HPV vaccine than the comparison group (15.5% vs. 7.1%) (Table 2). After the intervention, the experimental group showed 144 percent increase in intention to receive HPV vaccine while the comparison group increased by 67 percent. Total knowledge scores significantly improved from baseline to post-intervention in both groups (p < 0.001). However, there were significant group differences in mean changes of the total knowledge score [t (102) = 2.11; p < 0.05]. Both groups had more positive cognitive and affective attitudes toward HPV vaccine from baseline to post-intervention (p < 0.001), but there were no group differences in mean changes of cognitive and affective attitudes [t (100) = −1.93, p = 0.06] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Knowledge and Attitudes at Pretest, Immediate Post-Test and HPV Vaccine Uptakes at 2-Month Follow-up between the Experimental Group and the Comparison Group

| Pretest | Posttest | Change over time | 2-Month Follow-up | Mean Change | Percent change | Between Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or N (%) | p-value | N (%) | Mean (SD) | 95% Cl | p-value | ||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||||

| Total Knowledge Scorea | 0.04* | ||||||||

| Experimental (n=54) | 12.6 (6.40) | 24.1 (4.08) | 0.000 | - | 11.5 (6.76) | 9.65 | 13.35 | - | |

| Comparison (n=50) | 14.4 (6.64) | 23.2 (3.93) | 0.000 | - | 8.8 (6.36) | 6.97 | 10.59 | - | |

| Attitudes toward HPV vaccine | |||||||||

| Total Cognitive and Affective Attitudes Scoreb | 0.06 | ||||||||

| Experimental (n=54) | 11.4 (4.46) | 13.9 (4.24) | 0.000 | - | 2.7 (3.72) | 1.65 | 3.70 | - | |

| Comparison (n=50) | 9.6 (4.42) | 14.0 (3.94) | 0.000 | - | 4.2 (4.57) | 2.95 | 5.58 | - | |

| Conative: Intention to Receive | |||||||||

| HPV Vaccination (Yes) | |||||||||

| Experimental (n=54) | 15 (27.8) | 38 (70.4) | 0.000 | - | - | - | - | 144.4% | - |

| Comparison (n=50) | 21 (42.0) | 35 (70.0) | 0.000 | - | - | - | - | 66.7% | - |

| Vaccinated or scheduled to receive for HPV vaccine (n=10)c | |||||||||

| Experimental | - | - | 7 (15.6%) | - | - | - | - | 0.317 | |

| Comparison | - | - | 3 (7.1%) | - | - | - | - | ||

Note: SD=Standard Deviation,

p<0.05

(range: 0–32); One point was given for correct answer. If the answer was incorrect or “I don’t know”, a 0 point was given.

(range: 0–19); One point was given for “positive” response. If the answer was negative or “I don’t know”, a 0 point was given.

by Fisher’s exact test

Discussion

This pilot study examined the preliminary effectiveness of a storytelling intervention using mobile, web-based technology to promote HPV vaccination among Korean American college women. This study demonstrated that the storytelling intervention group was twice as likely to receive or schedule an appointment for the HPV vaccine than the comparison group who received information-based non-narrative written health information about HPV and HPV vaccine (15.5% vs. 7.1%; p<0.317). Moreover, both the intervention group and comparison group improved in knowledge, attitudes, and intention to receive HPV vaccination. These findings are consistent with an experimental study comparing written and video education interventions and assessing change in knowledge and intention at post-intervention, which suggest both written and video interventions increase knowledge and intention (Krawczyk et al., 2012). However, for experimental studies that assessed HPV vaccine uptakes, a narrative HPV video intervention group had a greater likelihood of getting the HPV vaccination compared to a control group who received an information-based intervention (Hopfer, 2012, Vanderpool et al., 2013). These collective findings suggest that increasing knowledge alone using traditional information-based interventions is insufficient to change college students’ HPV vaccination behavior. Changing attitudes and knowledge without increasing vaccination rates does not decrease health risks. Unlike information-based interventions, storytelling approaches deliver information while stimulating emotions, activating memories and visual imagination, and facilitating participant identification with storytellers, which may move them to change their attitudes toward an object while encouraging them to take action on a particular health behavior (Houston et al., 2011; McGregor & Holmes, 1999; H. Lee, Fawcett, & DeMarco, 2016). Moreover, our previous study showed significantly greater satisfaction and endorsement for the storytelling intervention that reflected cultural and generational experiences than the information-based written materials (p<0.05) (Kim et al., 2019), which provides additional support for the preliminary effectiveness of the storytelling intervention to increase HPV vaccination compliance among Korean American college women specifically. The findings of this study provide valuable insights into a novel, theory-based, culturally appropriate storytelling intervention that uses connected technologies to provide health education, which may help mitigate the challenges in promoting college students’ HPV vaccination.

Limitations

The limitations of this pilot study have provided valuable insights about the design of future studies. In this study, vaccination status was measured through a self-report questionnaire. However, previous research has indicated that there was substantial agreement (k = 0.67) between self-reported HPV vaccination and electronic recording of HPV vaccination (Rolnick et al., 2013). Previous research findings suggest that a narrative video intervention with a reminder system could increase the completion rates of the HPV vaccine series among college students. In future research, booster interventions or encouraging reminders should be considered with extended follow-up. Future studies should assess the impact of a longer-term intervention, as it may take time for college students to change their health behaviors during the school year.

Conclusions

Our web-based storytelling intervention shows substantial promise for further development and testing for future larger-scale RCT to promote Korean American college women’s HPV vaccination and completion of the series of HPV vaccines. Our storytelling approach with connected technology can be used to develop, expand and replicate similar interventions for other population-based disease prevention programs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of storytellers and Dr. Elisa Choi who provided invaluable information for the storytelling video intervention. We also would like to thank research team members, Deogwoon Kim, Penhsamnang Kan, and Tri Quach for their help in developing the storytelling video intervention.

Funding

This study was funded by the American Cancer Society (Grant Number: DSCN-129572) and supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health at the University of Massachusetts Medical School Worcester (R25 CA172009).

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

The study design and protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at University of Massachusetts Boston (protocol number 2016146).

Contributor Information

Minjin Kim, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences.

Haeok Lee, University of Massachusetts Boston, College of Nursing and Health Sciences.

Peter Kiang, School for Global Inclusion and Social Development, University of Massachusetts Boston.

Teri Aronowitz, University of Massachusetts Boston, College of Nursing and Health Sciences.

Lisa Kennedy Sheldon, Oncology Nursing Society.

Ling Shi, University of Massachusetts Boston, College of Nursing and Health Sciences.

Jeroan Allison, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences.

References

- Adegoke O, Kulasingam S, & Virnig B (2012). Cervical cancer trends in the United States: a 35-year population-based analysis. Journal of Women’s Health (15409996), 21(10), 1031–1037. 10.1089/jwh.2011.3385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison JJ, Nguyen HL, Ha DA, Chiriboga G, Ly HN, Tran HT, Phan NT, Vu NC, Kim M & Goldberg RJ (2016). Culturally adaptive storytelling method to improve hypertension control in Vietnam - “We talk about our hypertension”: study protocol for a feasibility cluster-randomized controlled trial. Trials, 17(26). 10.1186/s13063-015-1147-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2015). Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. (13th edition). Washington DC: Public Health Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Fang C, Ma G, Handorf E, Feng Z, Tan Y, & Rhee J (2016). Addressing multilevel barriers to cervical cancer screening in Korean American women: A randomized trial of a community-based intervention. Cancer, 123(6), 1018–1026. 10.1002/cncr.30391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfer S (2012). Effects of a narrative HPV vaccination intervention aimed at reaching college women: A randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science, 13(2), 173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston T, Cherrington A, Coley H, Robinson K, Trobaugh J, Williams J, & … Allison J (2011). The art and science of patient storytelling-harnessing narrative communication for behavioral interventions: The ACCE project. Journal of Health Communication, 16(7), 686–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Lee H, Kiang P, & Allison J (2019). Development and acceptability of a culturally appropriate, peer-paired, cross-generational-based storytelling HPV intervention for Korean American college women. Health Education Research. https://doi:10.1093/her/cyz022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Lee H, Kiang P, & Kim D (2017). Human Papillomavirus: A qualitative study of Korean American female college students’ attitudes toward vaccination. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 21(5), E239–E247. doi: 10.1188/17.CJON.E239-E247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk A, Lau E, Perez S, Delisle V, Amsel R, & Rosberger Z (2012). How to inform: Comparing written and video education interventions to increase human papillomavirus knowledge and vaccination intentions in young adults. Journal of the American College Health, 60(4), 326–322. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2011.615355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Fawcett J, & DeMarco R (2016). Storytelling/narrative theory to address health communication with minority populations. Applied Nursing Research, 30, 58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Kim M, Allison J, & Kiang P (2017). Development of a theory-led storytelling narrative intervention to improve HPV vaccination behavior: Save our daughters from cervical cancer. Applied Nursing Research, 34, 57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolnick SJ, Parker ED, Nordin JD, Hedblom BD, Wei F, Kerby T, & … Euler G (2013). Self-report compared to electronic medical record across eight adult vaccines: do results vary by demographic factors? Vaccine, 31(37), 3928–3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teare MD, Dimairo M, Shephard N, Hayman A, Whitehead A, & Walters SJ (2014). Sample size requirements to estimate key design parameters from external pilot randomised controlled trials: a simulation study. Trials, 15264. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderpool R, Cohen E, Crosby R, Jones M, Bates W, Casey B, & Collins T (2013). “1-2-3 Pap” Intervention Improves HPV Vaccine Series Completion Among Appalachian Women. Journal of Communication, 63(1), 95–115. Retrieved from 10.1111/jcom.12001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS, Carreon JD, Gomez SL, & Devesa SS (2010). Cervical cancer incidence among 6 asian ethnic groups in the United States, 1996 through 2004. Cancer, 116(4), 949–956. 10.1002/cncr.24843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]