Abstract

Background

The “trimorbidity” of substance use disorder and mental and physical illness is associated with living in precarious housing or homelessness. The extent to which substance use increases risk of psychosis and both contribute to mortality needs investigation in longitudinal studies.

Methods and findings

A community-based sample of 437 adults (330 men, mean [SD] age 40.6 [11.2] years) living in Vancouver, Canada, completed baseline assessments between November 2008 and October 2015. Follow-up was monthly for a median 6.3 years (interquartile range 3.1–8.6). Use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, methamphetamine, and opioids was assessed by interview and urine drug screen; severity of psychosis was also assessed. Mortality (up to November 15, 2018) was assessed from coroner’s reports and hospital records. Using data from monthly visits (mean 9.8, SD 3.6) over the first year after study entry, mixed-effects logistic regression analysis examined relationships between risk factors and psychotic features. A past history of psychotic disorder was common (60.9%). Nonprescribed substance use included tobacco (89.0%), alcohol (77.5%), cocaine (73.2%), cannabis (72.8%), opioids (51.0%), and methamphetamine (46.5%). During the same year, 79.3% of participants reported psychotic features at least once. Greater risk was associated with number of days using methamphetamine (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.14, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.05–1.24, p = 0.001), alcohol (aOR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01–1.18, p = 0.04), and cannabis (aOR 1.08, 95% CI 1.02–1.14, p = 0.008), adjusted for demographic factors and history of past psychotic disorder. Greater exposure to concurrent month trauma was associated with increased odds of psychosis (adjusted model aOR 1.54, 95% CI 1.19–2.00, p = 0.001). There was no evidence for interactions or reverse associations between psychotic features and time-varying risk factors. During 2,481 total person years of observation, 79 participants died (18.1%). Causes of death were physical illness (40.5%), accidental overdose (35.4%), trauma (5.1%), suicide (1.3%), and unknown (17.7%). A multivariable Cox proportional hazard model indicated baseline alcohol dependence (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.83, 95% CI 1.09–3.07, p = 0.02), and evidence of hepatic fibrosis (aHR 1.81, 95% CI 1.08–3.03, p = 0.02) were risk factors for mortality. Among those under age 55 years, a history of a psychotic disorder was a risk factor for mortality (aHR 2.38, 95% CI 1.03–5.51, p = 0.04, adjusted for alcohol dependence at baseline, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], and hepatic fibrosis). The primary study limitation concerns generalizability: conclusions from a community-based, diagnostically heterogeneous sample may not apply to specific diagnostic groups in a clinical setting. Because one-third of participants grew up in foster care or were adopted, useful family history information was not obtainable.

Conclusions

In this study, we found methamphetamine, alcohol, and cannabis use were associated with higher risk for psychotic features, as were a past history of psychotic disorder, and experiencing traumatic events. We found that alcohol dependence, hepatic fibrosis, and, only among participants <55 years of age, history of a psychotic disorder were associated with greater risk for mortality. Modifiable risk factors in people living in precarious housing or homelessness can be a focus for interventions.

Andrea Jones and colleagues investigate risk factors for psychosis and mortality in unstably housed people.

Author summary

Why was this study done?

People living in precarious housing conditions or with homelessness are at risk of poor health with complex risk factors, including substance use, mental disorders, and physical illness related to viral infection.

Psychosis is an impairment of brain function that, to a varying extent, disconnects people from reality through hallucinations, delusions, and impaired thought processes and is associated with early mortality.

The relative contributions of different complex risk factors to psychosis in precariously housed people are uncertain and are potentially modifiable, as is psychosis itself.

What did the researchers do and find?

We worked with 437 participants living in a neighborhood in Vancouver, Canada, meeting with each person monthly for on average 6 years, to learn how substance use and infection with HIV or hepatitis C contribute to risk for psychosis and how all these risk factors could contribute to early mortality.

The greatest risk factor for psychosis during the study follow-up was a history of a psychotic disorder (such as schizophrenia) in the past; however, taking this into account, ongoing use of alcohol, methamphetamine, and cannabis, as well as exposure to trauma, contributed additional risk for psychosis.

Alcohol dependence and liver damage contribute risk for early mortality; in participants under age 55, a history of a psychotic disorder contributed additional risk.

What do these findings mean?

The health challenges facing people living in precarious housing or homelessness are likely to require integrated care across substance use and mental and physical domains of health and illness.

Targeting alcohol, methamphetamine, and cannabis use may decrease the risk for psychosis.

Treating psychosis directly and modifying related risk factors comprehensively could contribute to decreasing high rates of early mortality.

Introduction

People living in precarious housing or homelessness experience a “trimorbidity” of substance use disorder and mental and physical illnesses that contributes to a higher than expected mortality [1–5]. Associations between substance use and mental illness have a long history, and recent epidemiological studies support the suggestion that acute episodes of substance-induced psychosis can convert into more chronic psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia [6,7]. Psychosis, defined as a mental state with grossly impaired reality testing, operationally manifests as hallucinations and delusions [8]. Changes over time in the severity of the cardinal symptoms of psychosis (called psychotic features and rated through direct clinical interview) can be used to define a change in mental state from nonpsychotic to psychotic or vice versa [9–13]. Psychosis may be relatively persistent in people with psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, or transient, as is common in substance-related psychosis [14].

Multiple types of risk factors are associated with psychotic disorders, several of which may be present in homeless or marginally housed people. Acute psychosis may be induced by nonprescription substance use such as methamphetamine, cocaine, cannabis, and alcohol [15–18]. Independent, dose-related effects of methamphetamine and cannabis use were identified in 2 studies of individuals with psychostimulant dependence, underscoring the importance of considering their combined effects [19,20]. In addition to considering the effects of substance use, multiple biopsychosocial risk factors appear to accumulate across the life span to increase the likelihood of psychosis and associated psychotic disorders, and several of these are common in socially marginalized populations [21,22]. Adults living in precarious housing endure significant socioeconomic inequities and may have complex histories of early-life trauma and head injury [23–26]. Accumulating evidence indicates that early-life traumatic events increase risk for persistent, clinically relevant psychotic symptoms later in life [27]. Proximal traumatic events may also exacerbate risk, and together, these risk factors may have additive or synergistic effects on expression of psychosis in adulthood [28,29]. Among precariously housed individuals, traumatic brain injury (TBI) is reported in a meta-analysis to have a prevalence of over 50%, with over 20% being of at least moderate severity [25,26,30]. TBI is associated with paranoid delusions and hallucinations, even years after the injury [31].

The presence of psychotic features has relevance for health, as well as diagnosis of psychotic disorders. A study of an urban general medicine practice reported psychotic features were present in 20.9% of patients, with adverse consequences for work and social function [32]. Psychotic features are part of the diagnostic criteria for psychotic disorders, with the latter estimated to be present in 10.2%–47.2% of people living in precarious housing or homelessness [33,34]. Psychotic disorders in the general population increase the risk of mortality, particularly related to the effects of alcohol and other drugs [35–37]. A similar effect of psychotic disorders is reported for mortality of younger and middle-aged persons living in precarious housing or homelessness [38].

Comprehensive, prospective, community-based studies of risk factors for psychotic symptoms over time are scarce, and the present study was designed to create an evidence base to permit analyses of the effects of multimorbidity on health in a homeless or precariously housed sample in Vancouver, Canada [34,35]. The first objective of the present analyses was to investigate how risk exposures collectively contribute to psychotic symptoms among adults in precarious housing. Monthly data from the first year after entering a longitudinal study were analyzed to determine the effects of substance use, early-life and recent traumatic events, and past TBI on the likelihood of psychosis [23,34]. Dose–response relationships for the effects of substances and of trauma were evaluated. Time-lagged effects and possible reverse associations (psychotic features preceding increased substance use or trauma) were tested. The second objective was to examine the role of substance use, selected medical illnesses, and psychotic disorders as potential risk factors for early mortality in homeless or marginally housed persons.

Methods

Participants

The Hotel Study is planned as a 20-year, naturalistic, longitudinal prospective study following an adult, community-based sample [23,34,39]. Briefly, participants were recruited from single-room occupancy (SRO) hotels (n = 372) and a sequential series from the community court (n = 65) in a circumscribed neighborhood of downtown Vancouver, Canada from November 1, 2008 to October 26, 2015. All tenants in a building were potentially eligible to participate; the only criteria were being 18 years of age or older, able to communicate in English, and able to provide informed consent. The neighborhood houses approximately 3,800 residents in SRO hotels; the court processes 2,500 cases per year. Participants were homeless or lived in precarious or marginal housing, defined as being below Canadian standards for adequacy (need for repairs), affordability (rental costs <30% of before-tax income), or suitability (makeup of bedrooms and household) [40]. Rooms in SRO hotels are generally 8–12 m2 in size, with a sink and sometimes a hotplate. Toilet and shower facilities are shared between 10 and 15 tenants on each floor.

Ethics statement

All participants provided written informed consent once procedures were completely described. Consent was reaffirmed at each visit thereafter. Clinically significant laboratory findings were shared with participants and their physicians. The study and the amount of an honorarium for participation were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Boards of the University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University.

Baseline assessment, psychiatric diagnosis, and mortality

Sociodemographic variables were recorded by a research assistant. A psychiatrist performed a semistructured interview, a mental status examination, and a focused neurological exam. A research assistant carried out a Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview [41]. Healthcare records for participants’ reports of past hospitalizations for mental illness were obtained from across Canada (available from >50 years ago in some cases). Baseline psychiatric symptoms were assessed using the 30-item Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [42]; functioning was assessed with the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) and the Role Functioning Scale (RFS) [8,43]. Diagnoses of current and past mental and substance use disorders were made by study psychiatrists (WGH, OL, FVR) using all available information noted above, according to criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-TR Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR) [8]. Coroner’s reports and records from hospitalizations for medical (nonpsychiatric) reasons were obtained for participants who died during the study period.

Screening laboratory tests were carried out at baseline and annually thereafter. These included a complete blood count and differential, liver function tests, and serology for hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) was used as a surrogate measure for hepatic fibrosis (values > 0.7) (42). More detailed descriptions of annual and monthly assessments, with references, appear in open-source publications and associated supplements [23,34].

Assessment of time-invariant risk factors for psychotic features

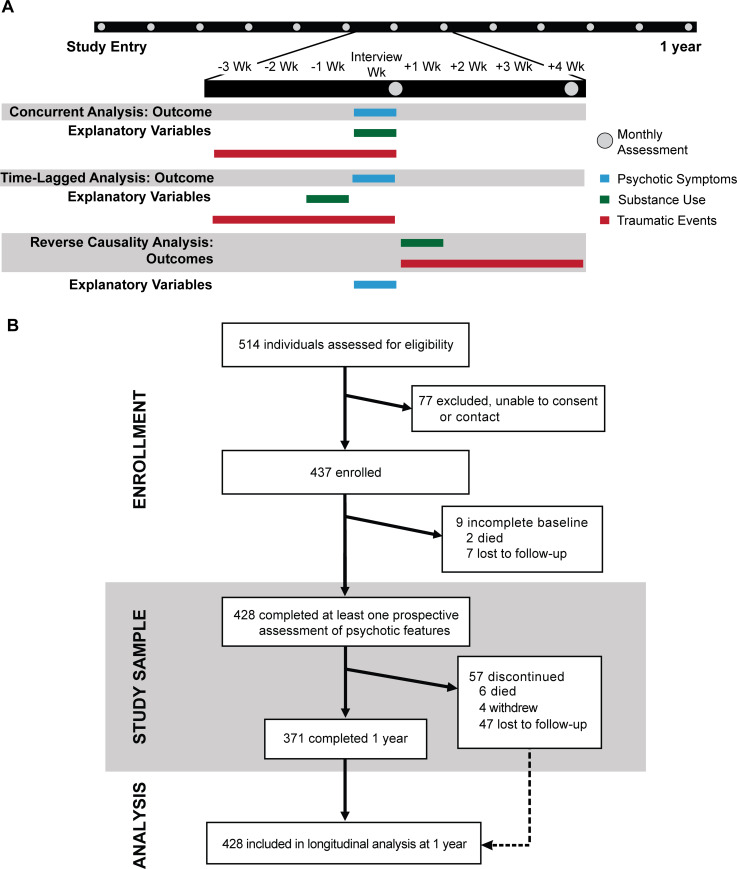

A comprehensive baseline assessment included standardized measures of time-invariant and time-varying risk factors (Fig 1A).

Fig 1.

Schematic of study design (A) and flow chart of participants (B) over the first year after study entry. Panel A depicts the study design to evaluate time-varying factors at monthly assessments over the first year after entering the study. At each monthly assessment visit (gray circle), psychosis in the past 7 days (“Interview week” in the Fig) is evaluated by a 5-item PANSS (blue bars). Substance use is evaluated week by week over the concurrent month using the Drug Timeline Follow-back approach (green bars). Traumatic events in the concurrent month are evaluated by the THQ (red bars). Panel B depicts participant flow in the enrollment, study samples, and data analysis for the psychotic features objective. Data analysis for the mortality objective incorporated outcomes for all participants from the study beginning (November 1, 2008) to the end of the mortality analytic period (November 15, 2018). PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; THQ, Trauma History Questionnaire.

Time-invariant risk factors are those that occurred in the past and/or are not modifiable. These include past psychotic disorder diagnosis (as above), persistent sequelae from past TBI, exposure to early-life traumatic events (any, and number), and homelessness by age 18. A history of TBI was determined by clinical interview and/or high-field (3-Tesla) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings identified by a neuroradiologist. Criteria for the presence of a past TBI were reporting a serious head injury with clinical manifestations (loss of consciousness ≥5 minutes or confusion ≥1 day and persistent sequelae defined as any of seizures in the past year attributable to TBI, need for seizure prophylaxis, or persistent neurological findings attributable to TBI) as used previously [23]. Past traumatic events were assessed using the semistructured Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ) [44]. Events involved objective threat of death or serious injury to which an individual reacted with extreme fear, horror, or helplessness according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria. The THQ is scored as the number of types of traumatic events endorsed to a maximum of 23, including physical, sexual, disaster-related, or crime-related events [45]. The number of types of traumatic events prior to age 18 (THQ18) was also recorded. Homelessness was defined as living on the street, in a shelter, couch surfing, or having no fixed address.

Assessment of substance use and other time-varying risk factors for psychotic features

Monthly follow-up visits were carried out in the neighborhood study office or by outreach to the participants’ dwellings. Exposures to time-varying risk factors occurring over the concurrent and previous 3 weeks (i.e., total 1 month) were assessed, including nonprescribed substance use (types and frequency), experience of traumatic events, homelessness, and the potentially protective effect of prescription drug treatment. Nonprescription substance use and prescribed drug treatment were reported week by week using the Timeline Follow-back method [46]. Nonprescription substance use in the psychosis assessment week (i.e., the 7 days prior to each monthly visit) was examined to capture acute effects of substance exposure on symptom severity; substance use in the week prior to the assessment week was examined for persistent effects of exposure. Methamphetamine, cocaine, cannabis, opioid, alcohol, and tobacco use were reported (and confirmed by urine testing at the visit for methamphetamine, cocaine, cannabis, and opioids, n = 3,267 observations, percent agreement ranging from 83.0% to 87.1%, and kappa ranging from 0.62 to 0.68, p < 0.001). Days of use and route of administration were reported. Tobacco use was dichotomized (nondaily or daily use) because of the high prevalence (89.0%) among participants. Antipsychotic treatment (medication type, dose, route of administration, days of use) was reported week by week. The validity of self-reported antipsychotic use was confirmed using PharmaNet, a province-wide network that links all pharmacy dispensing records to a central database (n = 67 available records for antipsychotic use, kappa = 0.71, p < 0.001). Adequacy of treatment for managing psychosis was determined according to the Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs guidelines [47] and reported adherence (i.e., depot or ≥80% of past 28 days taking oral medication) in consultation with a psychopharmacologist (RMP). Prescribed methadone therapy was reported and considered adequate if taken ≥80% of the past 28 days. Adequate methadone reports exhibited high concordance with urine testing (n = 3,215 observations, kappa = 0.82, p < 0.001).

Recent trauma was assessed at monthly visits (Fig 1A). The number of types of traumatic events that occurred in the concurrent month (rTHQ) was recorded and analyzed as an ordinal variable truncated at 2 or more, since only 3.0% had 3 or more types of events in the concurrent month. Periods of homelessness were also captured each month.

Outcome assessment of psychotic features

The prespecified plan was to focus on 5 key positive symptoms spanning the psychotic features description in the DSM: delusions, hallucinations, conceptual disorganization (thought disorder), suspiciousness (which may be delusional), and unusual thought content (which may be delusional). Individual PANSS items are scored on a 7-point scale, with descriptive anchors for each level of severity over the previous 7 days. Items scored 1 or 2 out of 7 are respectively “within limits of normal experience” or “questionable.” Threshold severity scores were established in advance for the 5 key items to establish the presence of clinically relevant psychotic features and are based on previous work [9–11]. Threshold scores were item-specific, calibrated to the descriptors provided for rating the PANSS as follows: (1) the threshold for the delusions and hallucinations items according to PANSS descriptors is a score of 3 (mild), indicating these symptoms are definitely present, consistent with the psychotic features definition according to the DSM and categorically different from a state of good mental health. (2) The threshold for the items of conceptual disorganization and unusual thought content was set to a score of 4 (moderate). For these items, according to PANSS descriptors, a score of 3 (mild) may or may not be associated with formal thought disorder or bizarre delusions. For this reason, the threshold score was set to a higher level, consistent with the use of similar items as inclusion criteria for clinical trials of antipsychotic medications [48]. (3) The threshold for the suspiciousness item was set to an even higher threshold value of 5 (moderately severe) because only at this level or above is the descriptor provided in the PANSS consistent with a paranoid delusion [42].

We examined the inter-rater reliability of this assessment strategy. Two raters carried out separate interviews of 26 participants on the same day. The reliability for presence or absence of at least 1 of a possible 5 symptoms meeting the threshold for psychotic features was kappa = 0.69 (p < 0.001). This is a more stringent approach than is used in most studies, in which inter-rater reliability for individual PANSS items is reported by having different raters observe the same video of a patient interview or by having 2 raters carry out a joint interview of a patient. Of the few available studies using independent raters, and independent interviews of the same patient, a test–retest reliability intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.65 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.62–0.68) was reported for the crosscutting domain of psychosis (hallucinations or delusions) [49].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of participants’ time-invariant and time-varying risk factors for psychotic features were reported as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and number (proportion) for categorical variables. The associations between a past history of a psychotic disorder diagnosis and current functioning at baseline were assessed using analysis of covariance, controlling for age and sex. Similar analyses were carried out with psychotic features at baseline.

The first objective was to investigate how risk exposures collectively contribute to psychotic features among adults in precarious housing. Using data from monthly visits over the first year following each participant’s study entry, mixed-effects logistic regression models with random intercept and slope for longitudinal binary outcome data were used to assess the relationships between psychotic features (presence or absence during the psychosis assessment week) and exposure to risk factors. Fixed effects estimated the main effects of risk factors on odds of psychotic features. Time-invariant risk factors included past psychotic disorder diagnosis (presence or absence), persistent sequelae from past TBI (presence or absence), homelessness by age 18 (presence or absence), and past exposure to traumatic events (dose–effect estimate). Time-varying risk factors included number of days of nonprescription substance use, exposure to recent traumatic events (dose–effect estimates), and homelessness in the concurrent month (present or absent). Linearity of dose–effect estimates was tested by modeling factors as continuous and ordinal predictors in separate models and testing both linear and quadratic effects. Other covariates included age, sex, time point, antipsychotic treatment, and methadone therapy. Random effects of subject and time were included to account for between-subject variability and within-subject correlation across repeated measures, respectively. Random effect standard deviations were reported. Adjusted models were estimated by a stepwise model fitting process iteratively adding and removing random effects, then time-invariant and time-varying fixed effects variables that were significantly associated with the outcome in bivariate analyses [50]. The best fitting multivariable model was identified by successively comparing nested models using a likelihood ratio test and comparing Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values. Model diagnostic plots were assessed for normality of the distribution of residuals. We tested multiplicative interactions using the Wald test. Predicted probabilities for psychotic features were estimated for combinations of significant risk factors.

Several approaches were employed to test the robustness of results (Fig 1A). Time-lagged substance use during the week prior to the psychosis assessment week was included in the adjusted model to estimate the persistence of substance use effects. Reverse association (sometimes described as “reverse causality,” although causality cannot be determined) was investigated by estimating the effect of psychotic features (presence or absence) on the days of substance use in the week following the psychosis assessment week using linear mixed-effects models and on the likelihood of a traumatic event during the following month using logistic mixed-effects models, adjusting for covariates. Further, the validity of self-reported substance use was tested by substituting urine results from the psychosis assessment visit for self-report in adjusted models. Sensitivity analyses assessed for evidence of systematic bias and the pattern of missingness by comparing participants who had missing or available variables of interest, who remained engaged in the study versus who discontinued, and who were included or excluded from longitudinal analyses using chi-squared and Wilcoxon rank–sum tests. Multiple imputation analysis was performed by imputing values generated from regression models with relevant predictors, including covariates of the main model of interest and variables related to a variable’s missingness. First, we imputed 10 completed data sets with 10 iterations for each imputation analysis. Second, the main model of interest was fitted to each of the completed data sets. Last, the parameter estimates from the second step were pooled to produce final parameter estimates. Pooled parameter estimates from the imputed data sets were compared to those from complete-case analysis to test whether our findings and inferences were affected by missing data.

The second objective was to examine the role of substance use, selected medical illnesses, and psychotic disorders as potential risk factors for early mortality, focusing on previously reported risk factors in the present sample examined over a shorter time period [38,51,52]. These analyses were not prespecified. Left-truncated and right-censored Cox regression models, with age as the timescale, were used to examine the effect of psychosis (a past history of psychotic disorder and/or psychotic features present during the first year after study entry), substance use, and related physical illness (hepatic fibrosis, HIV at baseline) on the risk of mortality for the time period November 1, 2008 to November 15, 2018. Statistical tests and visual plots of the Schoenfeld residuals were used to assess the assumption of proportionality of hazards. Violations of proportionality (i.e., significant Schoenfeld residual global test) were addressed by stratifying the sample using an age change point (threshold age separating a younger and an older group), determined by visual inspection of the Schoenfeld residual-by-age plots and identification of the age corresponding to the inflection point of the smoothing spline fit to the plots. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed to plot the effects of statistically significant predictors. All analyses were performed in R (version 3.4.0; R Core Team) and RStudio (version 1.0.143; R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Significance was set to alpha level of 0.05, and all p-values are 2-sided. Additional details on methodology appear in the S1 STROBE Checklist and the S1 Protocol.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics of participants

Staggered participant enrollment and flow appears in Fig 1B. Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants appear in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants at study entry and during the first year following study entry.

| At Study Entry | N = 437 |

| Age (years) | 40.6 (11.2) |

| Men | 340 (77.8%) |

| Ethnicity/race | |

| —White | 261 (59.7%) |

| —Indigenous | 113 (25.9%) |

| —Other | 63 (14.4%) |

| Completed high school or equivalent | 186/433 (43.0%) |

| Past homelessness | 323/431 (74.9%) |

| Receiving income assistance | 422/433 (97.5%) |

| Past psychotic disorder diagnosis | 266 (60.9%) |

| —Substance-induced psychosis | 110 (25.2%) |

| —Psychosis not otherwise specified | 55 (12.6%) |

| —Schizophrenia | 40 (9.2%) |

| —Schizoaffective disorder | 29 (6.6%) |

| —Depression or bipolar with psychosis | 28 (6.4%) |

| —Other psychotic disorder* | 4 (0.9%) |

| Past substance dependence diagnosis | |

| —Cocaine | 320 (73.2%) |

| —Opioid | 256 (58.6%) |

| —Alcohol | 210 (48.1%) |

| —Cannabis | 194 (44.4%) |

| —Methamphetamine | 159 (36.4%) |

| —Other | 60 (13.7%) |

| SOFAS score† (n = 425) | 39.9 (10.6) |

| PANSS‡ (n = 359) | |

| —Total score | 69.7 (17.5) |

| —Positive subscale | 16.0 (6.0) |

| —Negative subscale | 16.5 (5.8) |

| HIV seropositive | 65/409 (15.9%) |

| Hepatic fibrosis (APRI > 0.7) | 70/395 (17.7%) |

| During First Year after Entering Study (Analysis Data Set) | N = 428 |

| Monthly assessment visits over first year, no. per participant | 9.8 (3.6) |

| Frequency of participants with psychotic features** | |

| —Participants with psychotic features absent in all visits over first year | 93 (21.7%) |

| —Participants with psychotic features present in 1 visit over first year | 51 (11.9%) |

| —Participants with psychotic features present in ≥2 visits over first year | 284 (66.4%) |

| Participants with psychotic features at ≥1 visit, according to symptom type present | N = 335 |

| —Delusions | 302 (90.1%) |

| —Conceptual disorganization | 144 (43.0%) |

| —Hallucinatory behavior | 248 (74.0%) |

| —Suspiciousness/persecution | 131 (39.1%) |

| —Unusual thought content | 157 (46.9%) |

| —Only 1 symptom type above threshold (monosymptomatic) | 64 (19.1%) |

| —≥2 symptom types above threshold (polysymptomatic) | 271 (80.9%) |

Data are n/N (%), mean (SD).

*N = 1 delusional disorder, N = 3 psychosis due to a medical condition

†SOFAS is rated 0–100, with higher scores representing better functioning.

‡PANSS is a 30-item scale rated after an interview and mental status examination by a psychiatrist, used to assess the severity of positive and negative symptoms of psychosis and general mental health.

**Five key positive symptom items from the PANSS were rated at each monthly visit by a research assistant and serve as the primary data for presence of psychotic features outcome during the first year after study entry.

Abbreviations: APRI, aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SOFAS, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale.

At baseline, 425 of 437 (97.3%) participants were living in precarious housing, and 12 (2.7%) were homeless. The demographic characteristics of participants were similar to other reports from this Vancouver neighborhood and to reports from Canadian studies of precariously housed or homeless people in other cities (S1 Table, S2 Table).

The majority of participants had experienced past psychotic disorders and substance dependence (Table 1). In 4,285 assessments carried out across all participants over the first year following study entry, with a mean (SD) of 9.8 (3.6) visits per person, 335 of 428 (78.3%) participants endorsed positive symptom severity indicating the presence of 1 or more psychotic features according to the DSM on at least 1 visit (Table 1). Considering all assessments aggregated across participants over the first year after study entry, a single psychotic symptom was recorded in 781 of 4,285 (18.2%) of assessments; 2 or more psychotic symptoms were present in 1,069 of 4,285 (24.9%) of assessments. In assessments with 2 or more psychotic symptoms present, delusions and hallucinations were the most frequent combination, occurring in 709 of 1,069 (66.3%), followed by delusions and unusual thought content in 561 of 1,069 (52.5%).

At baseline, analyses of covariance showed participants’ levels of social and occupational function and of role functioning were associated with both a past history of psychotic disorder and the presence of current psychotic features, adjusting for age and sex (S3 Table, S4 Table). In combined analyses, the associations with current psychotic features predominated (SOFAS: estimate 2.3, standard error [SE] 0.6, p < 0.001; RFS: estimate 0.8, SE 0.2, p < 0.001).

Associations between risk factors and psychotic features

The characteristics of risk factors for psychotic features are described in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive characteristics of time-invariant and time-varying risk factors for the presence of psychotic features in visits over the first year after study entry.

| Risk Factor | N = 428 |

|---|---|

| Time-invariant risk factors | |

| Persistent clinical or MRI evidence of past TBI* | 43/428 (10.0%) |

| Traumatic events by age 18 (THQ score ≥1) | 330/420 (78.6%) |

| THQ items endorsed by age 18, no. (n = 420) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) |

| Homelessness by age 18 | 131/424 (30.9%) |

| Time-varying risk factors over the first year after entering study | |

| Any nonprescribed substance use over first year | |

| —Tobacco (any daily use) | 381/428 (89.0%) |

| —Alcohol | 331/427 (77.5%) |

| —Methamphetamine | 198/426 (46.5%) |

| —Cannabis | 310/426 (72.8%) |

| —Cocaine | 312/426 (73.2%) |

| —Opioids | 221/426 (51.9%) |

| Frequency of substance use over first year (users only) days per week | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) |

| —Alcohol use† | 2.0 (1.0–5.0) |

| —Methamphetamine use | 3.0 (1.0–7.0) |

| —Cannabis use | 7.0 (2.0–7.0) |

| —Cocaine use | 5.0 (2.0–7.0) |

| —Opioid use | 7.0 (2.0–7.0) |

| Participants experiencing any traumatic event(s) over first year (rTHQ score ≥1)‡ | 334/410 (81.5%) |

| Months over first year with traumatic events for participants with rTHQ score ≥1 | |

| —Months with no traumatic events | 7 (4–9) |

| —Months with 1 traumatic event | 1 (0–3) |

| —Months with ≥2 traumatic events | 0 (0–1) |

| Homeless ≥1 time over first year | 42/428 (9.8%) |

| Any prescribed substance use over first year | |

| —Adequate antipsychotic treatment | 101/427 (23.7%) |

| —Adequate methadone maintenance therapy | 166/427 (38.9%) |

Data are n/N (%) or median (interquartile range). Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; rTHQ, recent THQ; TBI, traumatic brain injury; THQ, Trauma History Questionnaire.

*Clinical evidence n = 19 (loss of consciousness ≥5 minutes or confusion ≥1 day AND persistent clinical symptoms such as seizures or cognitive impairment) or MRI/CT evidence (n = 24) of previous TBI.

†For alcohol, users had frequent weeks with no use, so value refers to weeks when using only.

‡rTHQ occurring in the month concurrent with the monthly psychosis assessment visit, carried out by a research assistant.

Persistent sequelae of past TBI indicated the consequences of physical trauma. Multiple types of traumatic life experiences before age 18, with potential implications for the development of mental disorders, were common. During the first year after study entry, participants used nonprescribed substances, in increasing order: methamphetamine, opioids, cannabis, cocaine, alcohol, and tobacco. In users, frequency of substance use over the first year varied from once per week to daily. Most participants experienced traumatic events at least once over the year; periods of homelessness were also noted as potential stressors. Adequate antipsychotic treatment was less common than adequate methadone treatment.

Effects of time-invariant and time-varying risk factors for psychotic features observed in the mixed-effects logistic regression models are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Effects of risk factors on odds of observing psychotic features in visits during the first year after entering the study.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* (n = 409, 3,625 Observations) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n, Observations | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Covariates | |||||

| Time (months) | 428, 4,294 | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.93–1.00) | 0.07 |

| Age | 428, 4,294 | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | 0.002 | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.78 |

| Male | 428, 4,294 | 1.79 (0.94–3.39) | 0.07 | 1.82 (1.03–3.21) | 0.04 |

| Time-invariant risk factors | |||||

| Past psychotic disorder diagnosis | 428, 4,294 | 14.05 (8.96–22.03) | <0.001 | 17.77 (10.83–29.15) | <0.001 |

| THQ score by age 18† | 420, 4,207 | 1.18 (1.07–1.31) | 0.001 | – | – |

| Persistent sequelae of TBI | 428, 4,294 | 1.36 (0.56–3.29) | 0.49 | – | – |

| Homelessness by age 18 | 424, 4,256 | 1.16 (0.65–2.07) | 0.62 | – | – |

| Time-varying risk factors over the first year after entering the study‡ | |||||

| Concurrent week of psychosis assessment | |||||

| Daily tobacco use | 428, 4,193 | 1.49 (0.96–2.31) | 0.07 | – | – |

| Days using alcohol | 427, 4,262 | 1.11 (1.03–1.20) | 0.007 | 1.09 (1.01–1.18) | 0.04 |

| Days using methamphetamine | 426, 4,233 | 1.13 (1.05–1.22) | 0.002 | 1.14 (1.05–1.24) | 0.001 |

| Days using cannabis | 426, 4,235 | 1.08 (1.03–1.13) | 0.002 | 1.08 (1.02–1.14) | 0.008 |

| Days using cocaine | 426, 4,235 | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) | 0.009 | – | – |

| Days using opioid | 426, 4,234 | 1.05 (0.99–1.12) | 0.08 | – | – |

| Concurrent month of psychosis assessment | |||||

| rTHQ score | 410, 3,775 | 1.50 (1.16–1.93) | 0.002 | 1.54 (1.19–2.00) | 0.001 |

| Homelessness | 428, 4,230 | 1.35 (0.65–2.80) | 0.41 | – | – |

| Adequate antipsychotic treatment | 427, 4,158 | 2.78 (1.76–4.40) | <0.001 | 2.04 (1.26–3.30) | 0.004 |

| Adequate methadone therapy | 427, 4,147 | 0.90 (0.62–1.30) | 0.58 | – | – |

Data are OR and 95% CI. Abbreviations: AIC, Akaike Information Criterion; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; rTHQ, recent THQ; TBI, traumatic brain injury; THQ, Trauma History Questionnaire.

*Adjusted model selected for optimal fit by AIC and likelihood ratio test. Fixed effects are adjusted for the included time-invariant, time-varying factors, and covariates. Random effects (standard deviation): subject (1.94), time point (0.22).

†Linear effects of THQ scores for number of traumatic events by age 18. Quadratic effects were not significant (p > 0.10).

‡Linear effects of number of days of substance use in the week concurrent with the psychosis assessment visit and rTHQ scores for the number of traumatic events (0, 1, or ≥2) in the month concurrent with the assessment visit are reported. Quadratic effects were not significant (p > 0.10).

The most potent risk factor was a past diagnosis of a psychotic disorder (see also Table 1). The final adjusted model (Table 3) indicated independent, linear, dose-dependent effects of days of alcohol, of methamphetamine, and of cannabis use in the concurrent week on odds for the presence of psychotic features. Greater exposure to trauma in the concurrent month was linearly associated with greater odds of psychotic features. The odds of experiencing psychotic features were greatest among males. Additionally, the presence of psychotic features was associated with receiving adequate antipsychotic treatment in the past month (likely indicating at least some of those in need did access treatment, but with incomplete response). These effects did not change over time during the year, and there was no evidence of multiplicative interactions. Other putative risk factors, including homelessness in the concurrent month, were not associated with experiencing psychotic features, nor was time itself associated with risk.

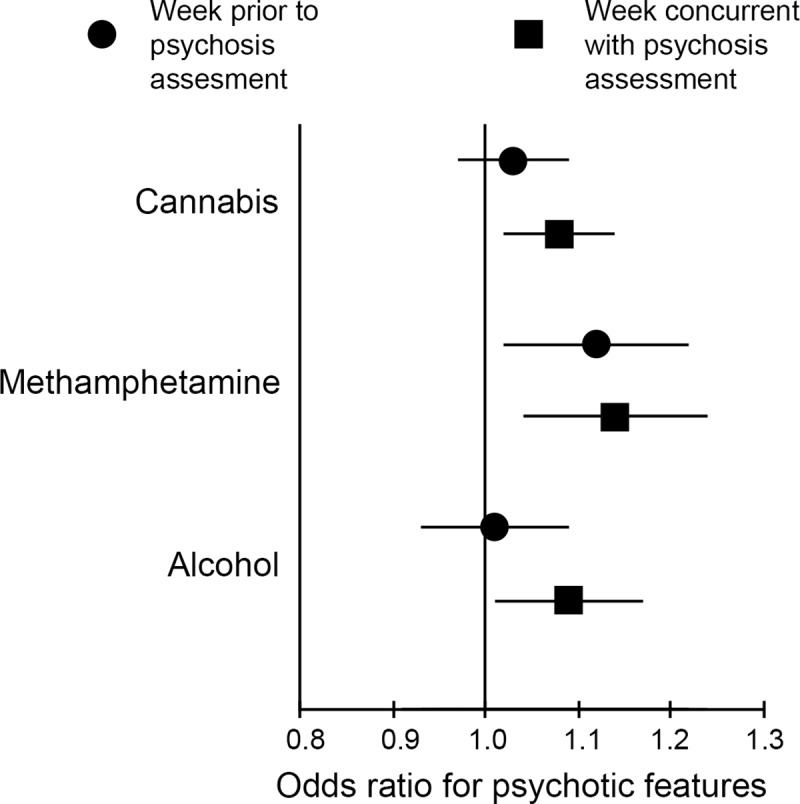

Time-lagged effects of substance use and potential reverse associations

For longer-acting substances, use in the week prior to the psychosis assessment week could contribute to the expression of psychotic features. To study this, a time-lagged analysis was carried out using the same mixed-effects logistic regression models as above, with substance use in the prior week substituted for substance use in the week concurrent with the psychosis assessment (Fig 1B and S5 Table). Time-invariant and concurrent month risk factor effects were unchanged. Use of cannabis or alcohol in the week prior did not contribute to the likelihood of psychotic features being observed in the psychosis assessment week (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Association between psychotic features and days of use of substances in the concurrent or the prior week.

In the concurrent week, use of all 3 substances increased likelihood of expression of psychotic features, suggesting acute effects; in the prior week, only use of methamphetamine was associated with increased likelihood of psychotic features in the assessment (concurrent) week.

Methamphetamine use showed a different pattern, as use in the prior week was associated with psychotic features in the psychosis assessment week (aOR = 1.12, 95% CI 1.03–1.22, p = 0.012). This suggests the effects of methamphetamine as a risk factor for psychotic features may be relatively longer lasting and/or the effects of cannabis and alcohol are more acute and transient. Next, the possibility of reverse association was analyzed using psychotic features as the predictor of substance use in the week following the psychosis assessment week (Fig 1B). No significant associations were observed for alcohol, methamphetamine, cannabis, or cocaine use (all p > 0.05, S6 Table). The presence of psychotic features at assessment was associated with the outcome of new traumatic experiences in the following month (OR = 1.27, 95% CI 1.04–1.55, p = 0.02). A similar relationship was observed when the covariates of time, age, sex, past psychotic disorder diagnosis, days of other nonprescription substance use in the following week, and adequate antipsychotic treatment in the following month were added to the model (OR = 1.30, 95% CI 1.05–1.62, p = 0.02).

Sensitivity analyses

Effects of substance use in the psychosis assessment week on likelihood of psychotic features were similar in mixed-effects logistic regression models, substituting urine drug screen results at the visit for self-reported substance use as risk factors (Table 4).

Table 4. Effects of urine drug screen results rather than self-report of substance use on odds of observing psychotic features in visits during the first year after entering the study.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* (n = 389, 2,816 Observations) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n, Observations | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Covariates | |||||

| Time (months) | 428, 4,294 | 0.94 (0.91–0.98) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.92–1.00) | 0.06 |

| Age | 428, 4,294 | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | 0.002 | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.20 |

| Male | 428, 4,294 | 1.79 (0.94–3.39) | 0.07 | 1.85 (1.05–3.27) | 0.03 |

| Time-invariant risk factors | |||||

| Past psychotic disorder diagnosis | 428, 4,294 | 14.05 (8.96–22.03) | <0.001 | 15.04 (9.18–24.64) | <0.001 |

| THQ score by age 18† | 420, 4,207 | 1.18 (1.07–1.31) | 0.001 | – | – |

| Persistent sequelae of TBI | 428, 4,294 | 1.36 (0.56–3.29) | 0.49 | – | – |

| Homelessness by age 18 | 424, 4,256 | 1.16 (0.65–2.07) | 0.62 | – | – |

| Time-varying risk factors over the first year after entering the study | |||||

| Concurrent week urine drug screen | |||||

| Methamphetamine | 415, 3,276 | 2.05 (1.48–2.83) | <0.001 | 2.44 (1.72–3.44) | <0.001 |

| Cannabis | 415, 3,274 | 1.79 (1.33–2.42) | <0.001 | 1.47 (1.06–2.02) | 0.02 |

| Cocaine | 415, 3,277 | 0.88 (0.64–1.21) | 0.43 | – | – |

| Opioid | 415, 3,273 | 1.27 (0.95–1.71) | 0.11 | – | – |

| Concurrent month | |||||

| rTHQ score‡ | 410, 3,775 | 1.50 (1.16–1.93) | 0.002 | 1.52 (1.14–2.03) | 0.004 |

| Homelessness | 428, 4,230 | 1.35 (0.65–2.80) | 0.41 | – | – |

| Adequate antipsychotic treatment | 427, 4,158 | 2.78 (1.76–4.40) | <0.001 | 1.91 (1.13–3.23) | 0.02 |

| Adequate methadone therapy | 427, 4,147 | 0.90 (0.63–1.30) | 0.58 | – | – |

Data are OR and 95% CI. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; rTHQ, recent THQ; TBI, traumatic brain injury; THQ, Trauma History Questionnaire.

*Adjusted for all time-invariant, time-varying factors, and covariates included. Random effects (standard deviation): subject (1.71), time point (0.22).

†Linear effects of THQ scores for number of traumatic events by age 18. Quadratic effects were not significant (p > 0.10).

‡Linear effects of rTHQ scores for the number of traumatic events (0, 1, or ≥2) in the month concurrent with the assessment visit are reported. Quadratic effects were not significant (p > 0.10).

Sensitivity analyses revealed no evidence of systematic bias in the pattern of missing data. Participants included in longitudinal analyses did not differ from excluded individuals, except they were older (chi-squared [1] = 6.67, p = 0.01). Participants with missing psychosis assessments were younger (estimate = −0.034, SE = 0.013, p = 0.007), and otherwise, missingness was not associated with psychotic features or risk factors. Participants who discontinued (e.g., moving from city, incarceration, living in treatment facility, lost contact) had greater THQ18 scores (Wilcoxon = 16,367, p = 0.039) but were otherwise similar on all factors to those who remained in the study. Altogether, data were determined to be missing at random, with missingness unrelated to psychosis or related factors, and we proceeded with the multiple imputation procedure to test whether missingness impacted the findings. Death, psychosis, and psychosis risk factors were included as potentially relevant predictors of missingness in the imputation procedure. Pooled parameter estimates from imputed data sets were similar to complete-case analysis results (S7 Table), suggesting that the present findings were not affected by missing data.

Psychosis and risk of early mortality

Participants continued with monthly follow-ups after the first year in the study, and as of November 15, 2018, participants were followed for a median of 6.3 years (25th–75th percentiles, 3.1–8.6 years) after study entry. During 2,481 person years of observation, 79 of 437 (18.1%) participants died. Causes of death were physical illness (40.5%), accidental overdose (35.4%), trauma (5.1%), suicide (1.3%), and unknown (17.7%). Unadjusted Cox proportional hazards regression analyses on the full sample indicated associations between mortality risk and evidence of hepatic fibrosis, HIV seropositive status, and baseline (but not past) alcohol dependence (Table 1 and S8 Table). Risks associated with past or baseline dependence on cocaine, methamphetamine, opioids, cannabis, or daily cigarette smoking were not statistically significant, nor was HCV-seropositive or qualitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)-positive status. Adjusted Cox regression analysis indicated statistically significant risks associated with hepatic fibrosis and alcohol dependence at baseline (Table 5).

Table 5. Adjusted survival analysis.

The effect of past history of psychotic disorder on mortality interacted with age; results are presented for 2 age groupings.

| Model: Whole Sample (n = 391) | Model: Age <55 Years (n = 281) | Model: Age ≥55 Years (n = 110) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factor | HR (95% CI) | Log-Rank p-Value | HR (95% CI) | Log-Rank p-Value | HR (95% CI) | Log-Rank p-Value |

| Baseline alcohol dependence | 1.83 (1.09–3.07) | 0.02 | 1.85 (0.89–3.87) | 0.10 | 1.55 (0.72–3.37) | 0.27 |

| Hepatic fibrosis (APRI > 0.7) | 1.81 (1.08–3.03) | 0.02 | 1.76 (0.76–4.08) | 0.19 | 1.55 (0.76–3.17) | 0.23 |

| HIV positive | 1.69 (0.99–2.87) | 0.06 | 0.93 (0.38–2.28) | 0.87 | 1.92 (0.92–4.00) | 0.08 |

| Past history psychosis | 2.38 (1.03–5.51) | 0.04 | 0.76 (0.39–1.48) | 0.43 |

Results are HR and 95% CI. Abbreviations: APRI, aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HR, hazard ratio.

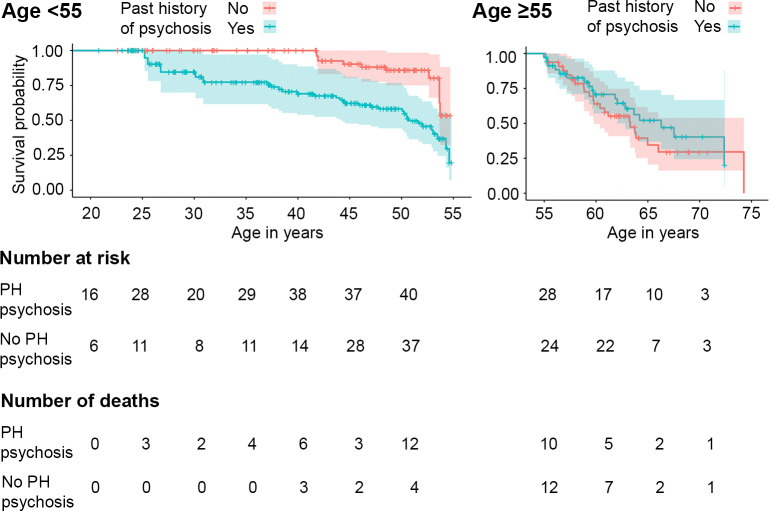

The effects on mortality of both a past history of psychotic disorder and psychotic features occurring during the first year after entering the study interacted with age as determined by a significant Schoenfeld residual global test (past history p = 0.04, first year psychotic features p = 0.02, S8 Table). By visual inspection of Schoenfeld residual plots, the change-point age separating younger and older groups was set at 55 years, consistent with earlier reports [38,52]. Unadjusted Cox proportional hazards regression analyses on the group less than 55 years of age showed an association between past history of psychosis and early mortality; no association was observed for psychotic features in the year following study entry, nor were associations observed in the older group (S8 Table). In those less than 55 years of age, a past history of psychotic disorder was associated with early mortality in a model controlled for baseline alcohol dependence, hepatic fibrosis, and HIV status (Table 5).

There were 39 deaths among 323 (12.1%) in the younger group and 40 among 114 (35.1%) in the older group. The distribution of causes of death did not differ between the younger and older groups or between those with or without a past history of psychotic disorder. As seen in Fig 3, for participants in the younger group, a past history of psychotic disorder (208 of 323, 64.4%) was associated with earlier death (30 of 208, 14.4% versus 9 of 115, 7.8%). In contrast, for participants age 55 or older, a past history of psychotic disorder (58 of 114, 50.9%) did not increase risk for early mortality (18 of 58, 31.0% versus 22 of 56, 39.3%).

Fig 3. Kaplan–Meier curves for the probability of survival by age among residents of precarious housing.

Left panel <55 years old, right panel ≥55 years old, comparing those with and without a history of a psychotic disorder. PH psychosis, past history of a psychotic disorder.

Discussion

In this sample of people living in precarious housing or homelessness in an impoverished neighborhood of Vancouver, Canada, we found that psychotic features were prominent and were associated with functional impairment. Not surprisingly, the most potent risk factor was a diagnosis of past history of a psychotic disorder. In adjusted analyses, methamphetamine, alcohol, and cannabis use also each showed associations with psychotic features; tobacco, cocaine, and opioids did not. Experiencing recent trauma also increased risk. In adjusted analyses, alcohol dependence and hepatic fibrosis both contributed to increased mortality; risk related to HIV was increased, but not statistically significant, in the adjusted analysis. The effects of psychotic disorders and psychotic features on mortality risk differed according to age. For those less than 55 years old, a past psychotic disorder increased mortality risk, adjusting for risks related to alcohol dependence, hepatic fibrosis, and HIV. The effect of past psychotic disorder was not seen for older study participants.

One of the earliest accounts of amphetamine-related psychosis described a group of patients who developed psychosis after a single dose of amphetamine or methamphetamine and another group in which the onset of psychotic features was after periods of days to years of use [53]. We observed effects related to days of use in the concurrent week and in the week prior. This finding is consistent with an earlier Hotel Study report relating the severity of positive symptoms of psychosis to the number of days using during the full month before assessment in a subsample of methamphetamine-dependent participants [20]. Similar dose and duration effects for methamphetamine in dependent users are reported by others [19,54,55].

Descriptions of the role of alcohol as a risk factor or precipitant for psychotic features span 3 centuries [56,57]. An acute onset is described, consistent with the present finding of increased odds of psychotic features in weeks concurrent with alcohol use but, in contrast to methamphetamine, less carry-over effect from use in the week prior. This could relate to the faster metabolism of alcohol compared with methamphetamine but could also represent a difference in the nature of the symptoms. Psychotic features related to methamphetamine may persist longer than 1 month in as many as 25% of users [58]. In recent epidemiological studies, alcohol-induced psychosis was the most frequent type of substance-induced psychosis yet was least likely to be associated with a later diagnosis of schizophrenia [6,7]. However, alcohol-induced psychotic disorder was reported to be associated with an increased risk of mortality [59].

The present findings of an association between recent cannabis use and psychotic features are consistent with reports of cannabis creating an acute toxic psychosis and with short-duration effects in laboratory studies of high doses of intravenous tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in 35%–50% of healthy participants [17,60,61]. The concentration of THC and of the potentially antipsychotic cannabidiol in the cannabis used by Hotel Study participants is unknown. In contrast to alcohol-related psychosis, in epidemiological studies, cannabis- and methamphetamine-induced psychotic disorders were more likely to be associated with progression to schizophrenia or other persistent psychotic disorder [6,7]. Larger samples of more homogenous groups of participants would be needed to address more specific questions related to the mechanism of action of cannabis to increase risk for persistent psychotic features and the potentially moderating effects of psychotic disorders. The present results do suggest that in a relatively large, heterogeneous group of people living in precarious housing, cannabis use is not without risk in contributing to psychotic features, even when concurrent substance use and other risk factors are included in the model. There was no evidence for a temporal association between psychotic features as a risk factor for subsequent increased substance use.

Cocaine use in the present sample was not associated with increased risk for psychotic features. A clinical account at the time of a widespread increase in use of crack cocaine reported prominent psychotic features, and a laboratory study administering intravenous cocaine in a binge-like schedule observed symptoms of paranoia [62,63]. In a previous report from the Hotel Study, psychotic features were less prominent in cocaine-dependent than in methamphetamine-dependent participants [64]. Differences in patterns of use may contribute to these findings, as may differences in the mechanism of action of cocaine and methamphetamine [54].

The present analysis did not demonstrate a direct role for childhood trauma in the occurrence of psychotic features when adjusting for more proximal risk factors and past history of psychotic disorder. A meta-analysis of studies of the effects of childhood adversity on persistent psychotic symptoms indicated high heterogeneity, complicating interpretation (34). Recent trauma was associated with psychotic features, and the reverse was also seen—the presence of psychotic features increased the vulnerability to subsequent traumatic events.

Mental disorders, including an important role for psychotic disorders, are increasingly appreciated as adding to mortality risk [35–37]. The present findings extend previous reports from the Hotel Study that in younger (<55 years old) participants, psychotic disorders contribute to mortality risk [23,34,38]. Psychotic disorders are additive with other risk factors observed here, including hepatic fibrosis and alcohol dependence, complementing findings related to HIV and HCV in another study from this neighborhood [51]. Comprehensive, integrated interventions are needed to address the trimorbidity of substance use and mental and physical illnesses that burden socially marginalized people worldwide [1–5].

Among the strengths of the study are the relatively large numbers of participants from a community-based sample with frequent longitudinal follow-up assessments. There are also limitations. The community sample was recruited in a Canadian neighborhood where nonprescribed substance use is widespread and universal healthcare is available. While the demographics of study participants were similar to those in other studies carried out in this and similar neighborhoods across Canada [65–68], in other contexts, drivers for psychosis, including migration, may differ and affect generalizability. Since the likelihood of psychosis was similar during periods of precarious housing or homelessness, these results may also apply to people at risk of homelessness. Similar to other longitudinal studies, missed visits may affect precision of the results, and unidentified factors may contribute to missingness, though no evidence of systematic bias was identified on sensitivity or multiple imputation analyses. The analyses here were not designed to assess the possible differences in patterns of psychotic features between participants who were substance users compared with substance dependence, substance-induced psychotic disorders, or other forms of psychotic disorders [69,70]. The focus was on the occurrence of psychotic features; the likelihood of transition or progression from one form of psychotic disorder to another over a 1-year or longer period deserves additional attention [6,7,71,72]. As well, our assessment approach focused on identifying the presence of psychotic features in a heterogeneous, community-based sample of participants living in precarious housing or homelessness. The same symptom severity thresholds were applied in other studies to identifying relapse from being asymptomatic to having recurrence of psychosis requiring clinical intervention [9,10]. This approach differs from severity thresholds used to assess improvement in treatment responsive patients with schizophrenia or in defining treatment-resistant schizophrenia [73,74]. A final limitation was the lack of useful family history information. One-third of the study participants grew up in foster care or with adoptive parents, and others experienced considerable adversity during childhood, limiting the feasibility of obtaining the necessary details.

In summary, this study of a community-based sample of people living in precarious housing or homelessness demonstrated multiple risk factors for psychotic features. A history of psychotic disorder increased the risk of early mortality in people under the age of 55 years. Ongoing substance use including methamphetamine, alcohol, and cannabis are modifiable risk factors that could be a focus for intervention.

Supporting information

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Abbreviations

- aHR

adjusted hazard ratio

- AIC

Akaike Information Criterion

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- APRI

aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index

- CI

confidence interval

- CT

computed tomography

- DSM-IV-TR

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-TR Fourth Edition

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- OR

odds ratio

- PANSS

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

- qPCR

qualitative polymerase chain reaction

- RFS

Role Functioning Scale

- rTHQ

recent THQ

- SE

standard error

- SOFAS

Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale

- SRO

single-room occupancy

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- THC

tetrahydrocannabinol

- THQ

Trauma History Questionnaire

Data Availability

Data cannot be made publicly available due to possible privacy breaches and other ethical and legal obligations to the study participants. These restrictions are outlined by the University of British Columbia’s Clinical Research Ethics Board and Simon Fraser University’s Research Ethics Board. Inquiries regarding data can be made to the Clinical Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia (ethics.research.ubc.ca).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants to WGH from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research [CBG-101827; MOP-137103] and BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services and to AET from the William and Ada Isabelle Steel Fund. WGH was supported by the Jack Bell Chair in Schizophrenia. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hwang SW, Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, O'Campo PJ, Dunn JR. Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses, and hotels in Canada: 11 year follow-up study. Brit Med J. 2009;339:1068–70. 10.1136/bmj.b4036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen SF, Hjorthøj CR, Erlangsen A, Nordentoft M. Psychiatric disorders and mortality among people in homeless shelters in Denmark: a nationwide register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2011;377:2205–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60747-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW, Nordentoft M, Luchenski SA, Hartwell G, et al. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391:241–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31869-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luchenski S, Maguire N, Aldridge RW, Hayward A, Story A, Perri P, et al. What works in inclusion health: overview of effective interventions for marginalised and excluded populations. Lancet. 2018;391:266–80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31959-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starzer MSK, Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C. Rates and predictors of conversion to schizophrenia or bipolar disorder following substance-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:343–50. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17020223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Prediction of onset of substance-induced psychotic disorder and its progression to schizophrenia in a Swedish national sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:711–719. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18101217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui CLM, Honer WG, Chang WC, Chen ESM, Lui SSY, Jones PB, et al. Long-term effects of discontinuation from antipsychotic maintenance following first-episode schizophrenia and related disorders: a 10 year follow-up of a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:432–42. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30090-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen EYH, Hui CLM, Lam MML, Chiu CPY, Law CW, Chung DWS, et al. Maintenance treatment with quetiapine versus discontinuation after one year of treatment in patients with remitted first episode psychosis: randomised controlled trial. Brit Med J. 2010;341:c4024–4. 10.1136/bmj.c4024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaughn CE, Snyder KS, Jones S, Freeman WB, Falloon IR. Family factors in schizophrenic relapse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:1169–77. 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790230055009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landin-Romero R, McKenna PJ, Romaguera A, Álvarez-Moya E, Sarró S, Aguirre C, et al. Examining the continuum of psychosis: Frequency and characteristics of psychotic-like symptoms in relatives and non-relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;178:6–11. 10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendler KS, Gallagher TJ, Abelson JM, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, demographic risk factors, and diagnostic validity of nonaffective psychosis as assessed in a US community sample—The National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1022–31. 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110060007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieberman JA, First MB. Psychotic disorders. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:270–80. 10.1056/NEJMra1801490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glasner-Edwards S, Mooney LJ. Methamphetamine psychosis: epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2014;28:1115–26. 10.1007/s40263-014-0209-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vorspan F, Brousse G, Bloch V, Bellais L, Romo L, Guillem E, et al. Cocaine-induced psychotic symptoms in French cocaine addicts. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:1074–6. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray RM, Englund A, Abi-Dargham A, Lewis DA, Di Forti M, Davies C, et al. Cannabis-associated psychosis: neural substrate and clinical impact. Neuropharmacol. 2017;124:89–104. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordaan GP, Emsley R. Alcohol-induced psychotic disorder: a review. Metab Brain Dis. 2014;29:231–43. 10.1007/s11011-013-9457-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKetin R, Lubman DI, Baker AL, Dawe S, Ali RL. Dose-related psychotic symptoms in chronic methamphetamine users: evidence from a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:319–24. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willi TS, Honer WG, Thornton AE, Gicas K, Procyshyn RM, Vila-Rodriguez F, et al. Factors affecting severity of positive and negative symptoms of psychosis in a polysubstance using population with psychostimulant dependence. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:336–42. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howes OD, Murray RM. Schizophrenia: an integrated sociodevelopmental-cognitive model. Lancet. 2014;383:1677–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62036-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zammit S, Lewis G, Dalman C, Allebeck P. Examining interactions between risk factors for psychosis. Brit J Psychiatry. 2010;197:207–11. 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.070904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vila-Rodriguez F, Panenka WJ, Lang DJ, Thornton AE, Vertinsky AT, Wong H, et al. The Hotel study: multimorbidity in a community sample living in marginal housing. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1413–22. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12111439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knight KR, Lopez AM, Comfort M, Shumway M, Cohen J, Riley ED. Single room occupancy (SRO) hotels as mental health risk environments among impoverished women: the intersection of policy, drug use, trauma, and urban space. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25:556–61. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang SW, Colantonio A, Chiu S, Tolomiczenko G, Kiss A, Cowan L, et al. The effect of traumatic brain injury on the health of homeless people. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;179:779–84. 10.1503/cmaj.080341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmitt T, Thornton AE, Rawtaer I, Barr AM, Gicas KM, Lang DJ, et al. Traumatic brain injury in a community-based cohort of homeless and vulnerably housed individuals. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:3301–10. 10.1089/neu.2017.5076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trotta A, Murray RM, Fisher HL. The impact of childhood adversity on the persistence of psychotic symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2015;45:2481–98. 10.1017/S0033291715000574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mansueto G, Faravelli C. Recent life events and psychosis: the role of childhood adversities. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:111–7. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lataster J, Myin-Germeys I, Lieb R, Wittchen HU, van Os J. Adversity and psychosis: a 10-year prospective study investigating synergism between early and recent adversity in psychosis. Acta Psychiat Scand. 2012;125:388–99. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01805.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stubbs JL, Thornton AE, Sevick JM, Silverberg ND, Barr AM, Honer WG, et al. Traumatic brain injury in homeless and marginally housed individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e19–e32. 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30188-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sachdev P, Smith JS, Cathcart S. Schizophrenia-like psychosis following traumatic brain injury: a chart-based descriptive and case-control study. Psychol Med. 2001;31:231–9. 10.1017/s0033291701003336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olfson M, Lewis-Fernandez R, Weissman MM, Feder A, Gameroff MJ, Pilowsky D, et al. Psychotic symptoms in an urban general medicine practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1412–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fazel S, Khosla V, Khosla V, Doll H, Doll H, Geddes J, et al. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e225 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Honer WG, Cervantes-Larios A, Jones AA, Vila-Rodriguez F, Montaner JS, Tran H, et al. The Hotel study-clinical and health service effectiveness in a cohort of homeless or marginally housed persons. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62:482–92. 10.1177/0706743717693781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:334–41. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1575–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, Crystal S, Stroup TS. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1172–81. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones AA, Vila-Rodriguez F, Leonova O, Langheimer V, Lang DJ, Barr AM, et al. Mortality from treatable illnesses in marginally housed adults: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5: e008876 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barbic SP, Jones AA, Woodward M, Piercy M, Mathias S, Vila-Rodriguez F, et al. Clinical and functional characteristics of young adults living in single room occupancy housing: preliminary findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Can J Pub Health. 2018;109: 204–214. 10.17269/s41997-018-0087-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaetz S, Barr C, Friesen A, Harris B, Hill C, Kovacs-Burns K, et al. Canadian definition of homelessness. Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, Toronto [Internet]. 2012. [cited 2019 May 24]. Available from: https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/COHhomelessdefinition.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amorim P, Lecrubier Y, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Sheehan D. DSM-III-R Psychotic Disorders: procedural validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). Eur Psychiatry. 1998;13:26–34. 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)86748-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 1987;13:261–76. 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodman SH, Sewell DR, Cooley EL, Leavitt N. Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: the Role Functioning Scale. Comm Ment Health J. 1993;29:119–31. 10.1007/BF00756338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Rosenberg SD, Ford JD, Fox L, Carty P. Psychometric evaluation of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder assessments in persons with severe mental illness. Psychol Assess. 2001;13:110–7. 10.1037//1040-3590.13.1.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hooper LM, Stockton P, Krupnick JL, Green BL. Development, use, and psychometric properties of the Trauma History Questionnaire. J Loss Trauma. 2011;16:258–83. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sacks JAY, Drake RE, Williams VF, Banks SM, Herrell JM. Utility of the Time-Line Follow-Back to assess substance use among homeless adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191:145–53. 10.1097/01.NMD.0000054930.03048.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Procyshyn RM, Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ. Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs. Boston, MA: Hogrefe Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:789–96. 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800330013001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Narrow WE, Clarke DE, Kuramoto SJ, Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ, Greiner L, et al. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part III: development and reliability testing of a cross-cutting symptom assessment for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:71–82. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12071000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolker BM, Brooks ME, Clark CJ, Geange SW, Poulsen JR, Stevens MHH, et al. Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009;24:127–35. 10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deans GD, Raffa JD, Lai C, Fischer B, Krajden M, Amin J, et al. Mortality in a large community-based cohort of inner-city residents in Vancouver, Canada. Can Med J Open. 2013;1:E68–76. 10.9778/cmajo.20130002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gicas KM, Jones AA, Thornton AE, Petersson A, Livingston E, Waclawik K, et al. Cognitive decline and mortality in a community-based sample of homeless and precariously housed adults: 9-year prospective study. Br J Psychiatry Open. 2020;6: e21 10.1192/bjo.2020.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Connell PH. Amphetamine Psychosis. Maudsley Monograph. London: Chapman & Hall; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Panenka WJ, Procyshyn RM, Lecomte T, MacEwan GW, Flynn SW, Honer WG, et al. Methamphetamine use: a comprehensive review of molecular, preclinical and clinical findings. Drug Alc Depend. 2013;129:167–79. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arunogiri S, Foulds JA, McKetin R, Lubman DI. A systematic review of risk factors for methamphetamine-associated psychosis. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2018;52:514–29. 10.1177/0004867417748750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glass IB. Alcoholic hallucinosis: a psychiatric enigma –1. The development of an idea. Br J Addict. 1989;84: 29–41. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00549.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Glass IB. Alcoholic hallucinosis: a psychiatric enigma– 2. Follow-up studies. Br J Addict. 1989;84: 151–164. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00564.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voce A, Calabria B, Burns R, Castle D, McKetin R. A systematic review of the symptom profile and course of methamphetamine-associated psychosis. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54:549–59. 10.1080/10826084.2018.1521430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perälä J, Kuoppasalmi K, Pirkola S, Härkänen T, Saarni S, Tuulio-Henriksson A, et al. Alcohol-induced psychotic disorder and delirium in the general population. Brit J Psychiatry. 2010;197:200–6. 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.070797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vallersnes OM, Dines AM, Wood DM, Yates C, Heyerdahl F, Hovda KE, et al. Psychosis associated with acute recreational drug toxicity: a European case series. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:293 10.1186/s12888-016-1002-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Solomons K, Neppe VM, Kuyl JM. Toxic cannabis psychosis is a valid entity. S Afr Med J. 1990;78:476–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Honer WG, Gewirtz G, Turey M. Psychosis and violence in cocaine smokers. Lancet. 1987;2: 451 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90982-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalayasiri R, Sughondhabirom A, Gueorguieva R, Coric V, Lynch WJ, Morgan PT, et al. Self-reported paranoia during laboratory “binge” cocaine self-administration in humans. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;83:249–56. 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alexander PD, Gicas KM, Willi TS, Kim CN, Boyeva V, Procyshyn RM, et al. A comparison of psychotic symptoms in subjects with methamphetamine versus cocaine dependence. Psychopharmacol. 2017;234:1535–47. 10.1007/s00213-017-4551-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hwang SW, Aubry T, Palepu A, Farrell S, Nisenbaum R, Hubley AM, et al. The health and housing in transition study: a longitudinal study of the health of homeless and vulnerably housed adults in three Canadian cities. Int J Public Health. 2011;56: 609–623. 10.1007/s00038-011-0283-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lewis M, Boyes K, McClanahan D, Copas J. Downtown Eastside demographic study of SRO and social housing tenants. Vancouver: City of Vancouver [Internet]; 2008. June [cited 2016 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.vancouveragreement.ca/wp-content/uploads/080600_DTES-Demographic-Study-Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shannon K, Ishida T, Lai C, Tyndall MW. The impact of unregulated single room occupancy hotels on the health status of illicit drug users in Vancouver. Int J Drug Policy. 2006;17:107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Palepu A, Gadermann A, Hubley AM, Farrell S, Gogosis E, Aubry T, et al. Substance use and access to health care and addiction treatment among homeless and vulnerably housed persons in three Canadian cities. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: e75133 10.1371/journal.pone.0075133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bousman CA, McKetin R, Burns R, Woods SP, Morgan EE, Atkinson JH, et al. Typologies of positive psychotic symptoms in methamphetamine dependence. Am J Addict. 2015;24:94–7. 10.1111/ajad.12160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McKetin R, Baker AL, Dawe S, Voce A, Lubman DI. Differences in the symptom profile of methamphetamine-related psychosis and primary psychotic disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:349–54. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]