Abstract

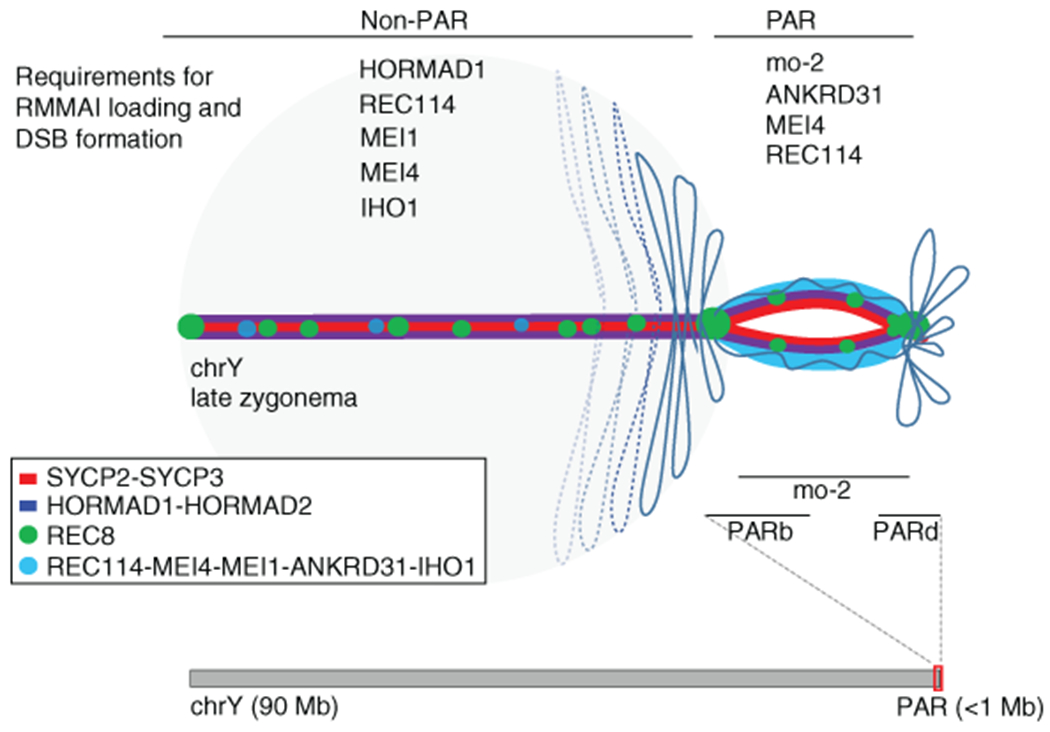

Sex chromosomes in males of most eutherian species share only a diminutive homologous segment, the pseudoautosomal region (PAR), wherein double-strand break (DSB) formation, pairing, and crossing over must occur for correct meiotic segregation1,2. How cells ensure PAR recombination is unknown. Here we delineate an unexpected dynamic ultrastructure of the PAR and identify controlling cis- and trans-acting factors that make this the hottest area of DSB formation in the male mouse genome. Before break formation, multiple DSB-promoting factors hyper-accumulate in the PAR, its chromosome axes elongate, and the sister chromatids separate. These phenomena are linked to heterochromatic mo-2 minisatellite arrays and require MEI4 and ANKRD31 proteins but not axis components REC8 or HORMAD1. We propose that the repetitive PAR sequence confers unique chromatin and higher order structures crucial for recombination. Chromosome synapsis triggers collapse of the elongated PAR structure and, remarkably, oocytes can be reprogrammed to display spermatocyte-like PAR DSB levels simply by delaying or preventing synapsis. Thus, sexually dimorphic behavior of the PAR rests in part on kinetic differences between the sexes for a race between maturation of PAR structure, DSB formation, and completion of pairing and synapsis. Our findings establish a mechanistic paradigm of sex chromosome recombination during meiosis.

During meiotic recombination, DSBs must occur within the tiny (~700 kb3,4) mouse PAR2–6. Since on average one DSB forms per ten megabases, the PAR would risk frequent recombination failure if it behaved like a typical autosomal segment2. Consequently, the PAR has disproportionately frequent DSBs and recombination2,6–8 (Supplementary Discussion). Mechanisms promoting such frequent DSBs are unknown in any species.

DSBs arise concomitantly with linear axial structures that anchor chromatin loops wherein DSBs occur9,10. Axes begin to form during replication and become assembly sites for proteins that promote SPO11 DSBs11–13. PAR chromatin in spermatocytes forms relatively short loops on a long axis2. However, only a low-resolution view of PAR structure was available and the controlling cis- and trans-acting factors were unknown. Moreover, it was unclear how spermatocytes but not oocytes make the PAR so hyperrecombinogenic.

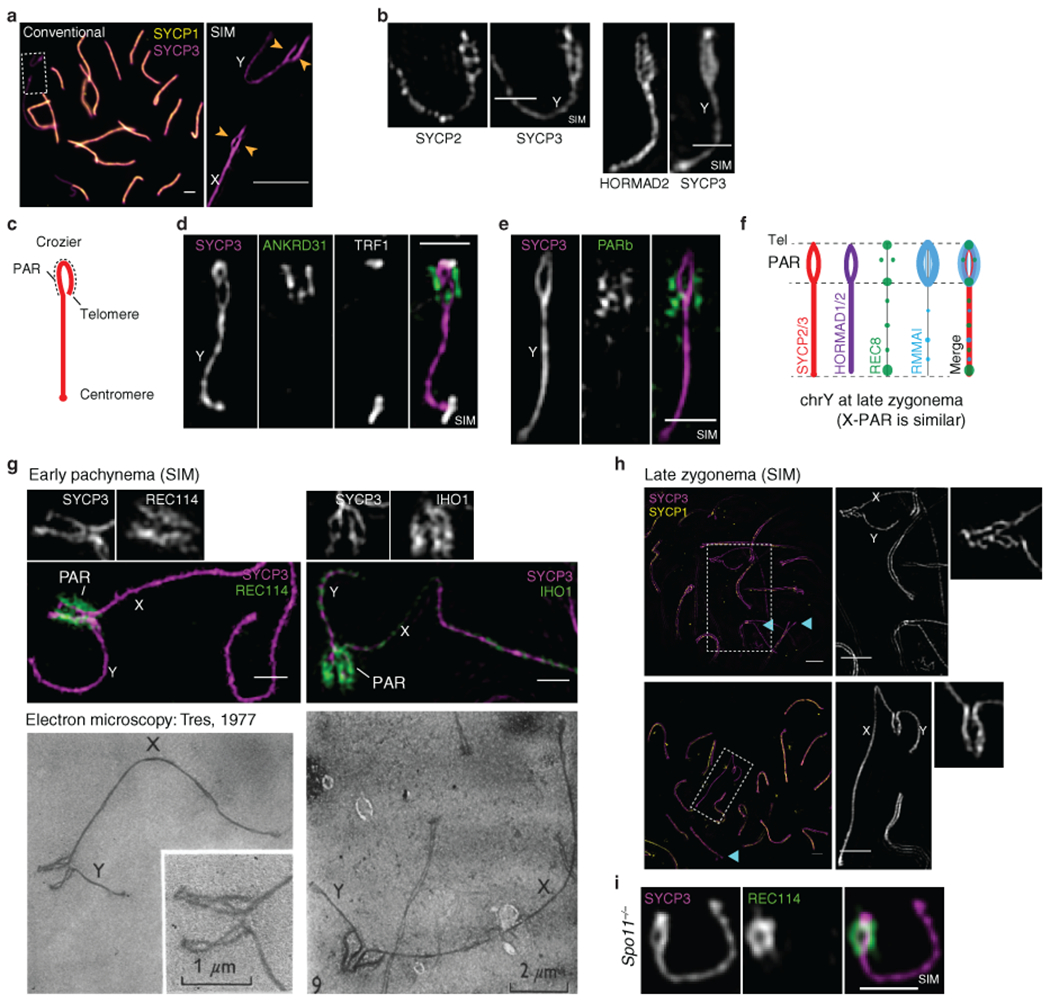

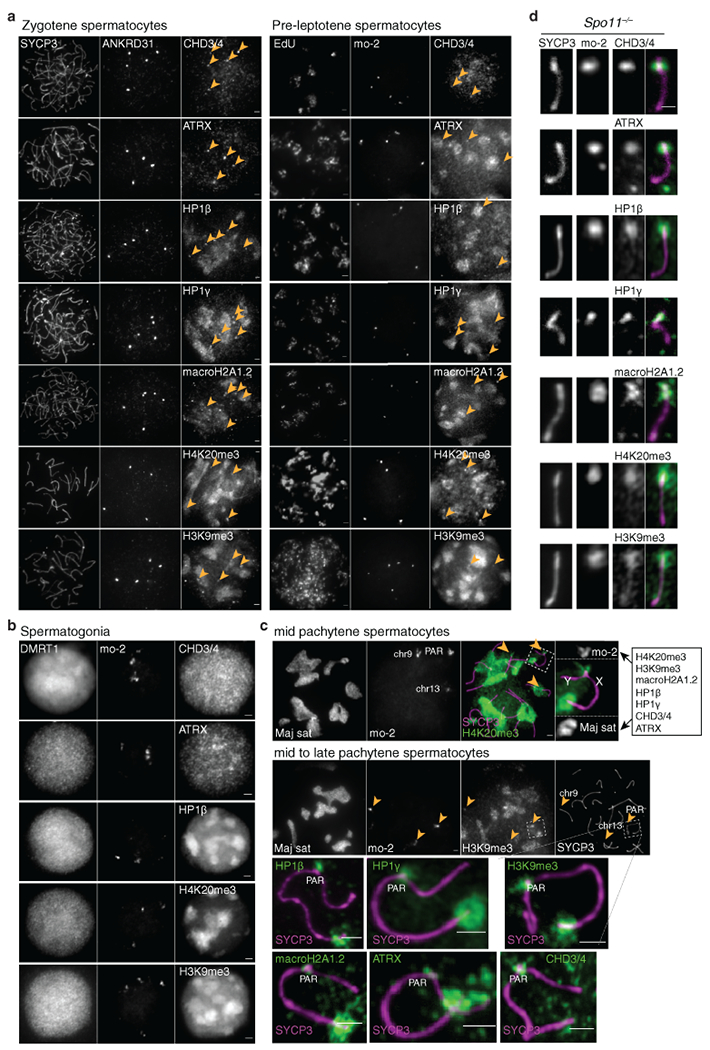

A distinctive PAR ultrastructure

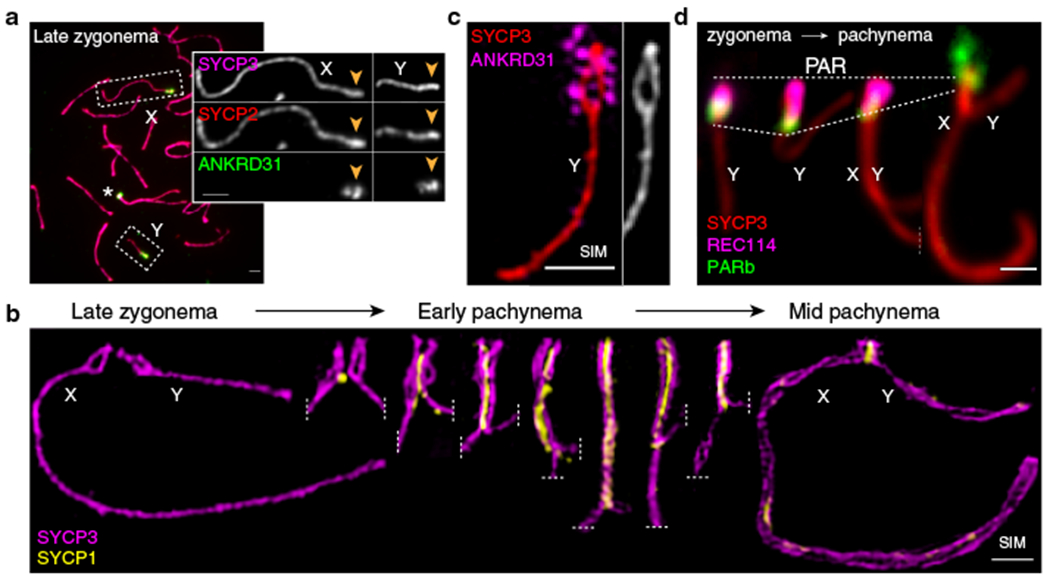

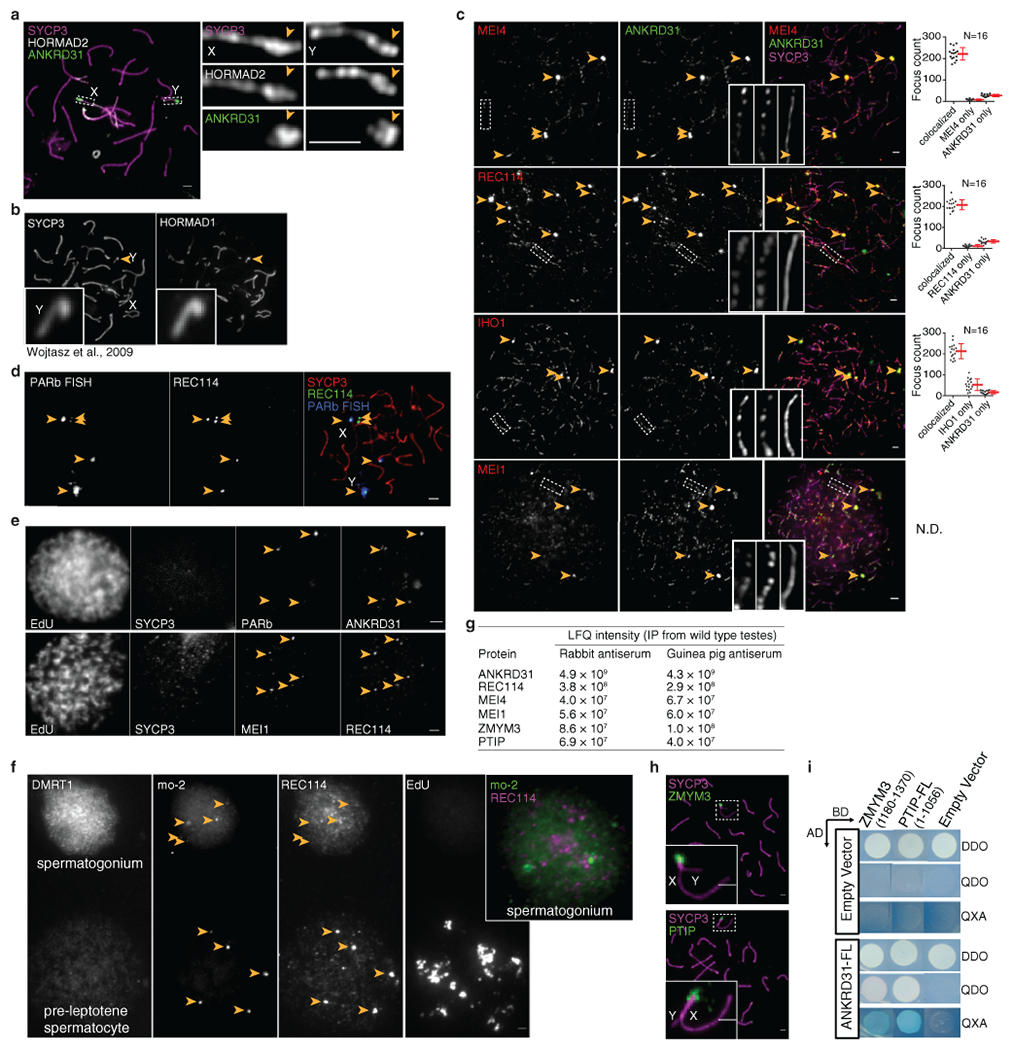

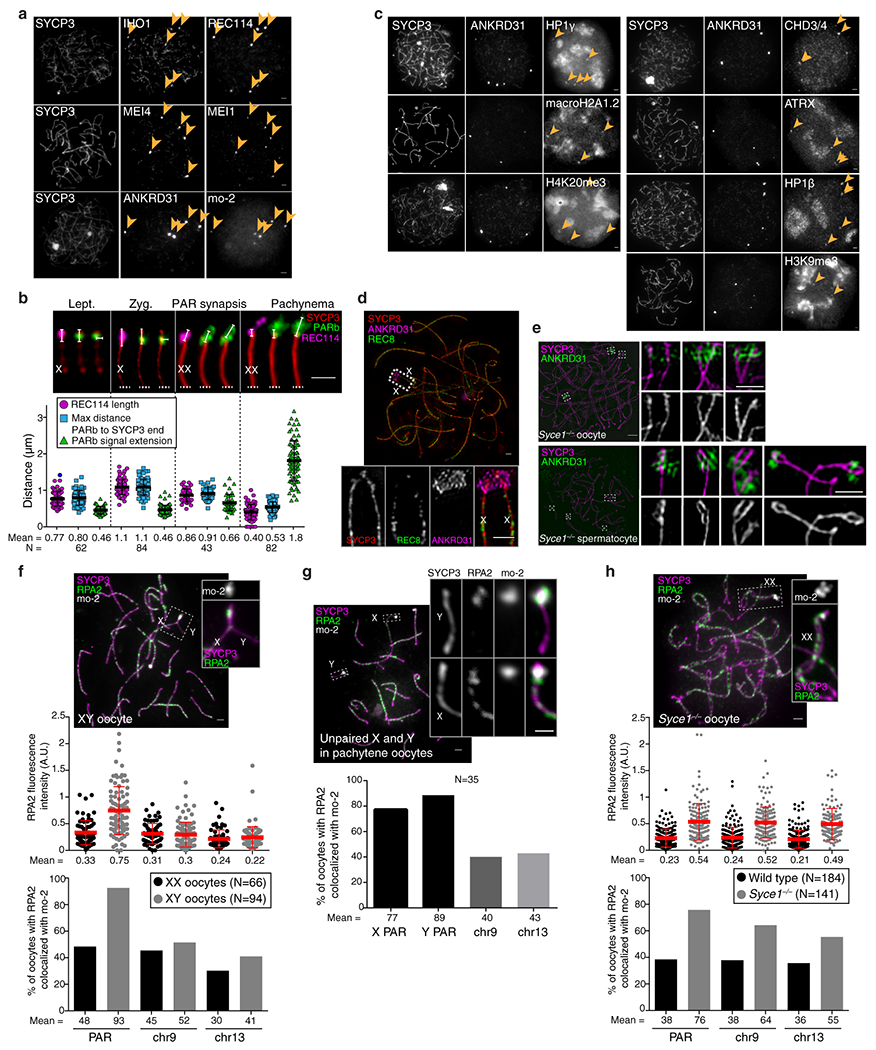

X and Y usually pair late, with PARs paired in less than 20% of spermatocytes at late zygonema when most autosomes are paired2,14. At this stage, unsynapsed PAR axes (SYCP2/3) appeared thickened relative to other unsynapsed axes and had bright HORMAD1/2 staining (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a,b)15. Moreover, the PAR was highly enriched for REC114, MEI4, MEI1, and IHO1—essential for genome-wide DSB formation16–19—plus ANKRD31, a REC114 partner essential for PAR DSBs20,21.

Fig. 1: Ultrastructure of the PAR during male meiosis.

(a) Axis thickening (SYCP2 and SYCP3) and ANKRD31 accumulation on X and Y PARs (arrowheads) in late zygonema. The asterisk shows an autosomal ANKRD31 blob. Scale bar: 2 μm. (b) Ultrastructure of the PAR before and after synapsis (montage of representative SIM images). Dashed lines indicate where chromosomes are cropped. SIM: Structured Illumination Microscopy. Scale bar: 1 μm. (c) RMMAI enrichment along split PAR axes in late zygonema. Scale bar: 1 μm. (d) Schematic showing the dynamic remodeling of the PAR loop–axis ensemble during prophase I. See measurements in Extended Data Fig. 3b. Scale bar: 1 μm.

All five proteins (RMMAI) colocalized in several bright “blobs” for most of prophase I (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1c). Two blobs were on X and Y PARs and others highlighted specific autosome ends (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1d), revisited below. Similar blobs in published micrographs were uncharacterized16,17,19,22. The proteins also colocalized in smaller foci along unsynapsed axes16,17,19–22 (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Enrichment on the PAR was already detectable in pre-leptonema (Extended Data Fig. 1e)17,22 but not in spermatogonia (Extended Data Fig. 1f). Mass spectrometry of testis immunoprecipitates identified ZMYM3 and PTIP as new ANKRD31 interactors also enriched on the PAR (Extended Data Fig. 1g–i).

Structured illumination microscopy (SIM) resolved the thickened PAR as two axial cores (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 2a,b) decorated with RMMAI (Fig. 1c). PAR axes were extended and separated in late zygonema before X and Y synapsis, then collapsed during X–Y synapsis in early pachynema (Fig. 1b). Each axial core is a sister chromatid, with a “bubble” from near the PAR boundary almost to the telomere (Extended Data Fig. 2c–h). This PAR structure is distinct from what is seen at chromosome ends later in prophase I (Supplementary Discussion). Axis splitting and REC114 enrichment occurred independently of DSB formation (Extended Data Fig. 2i).

Dynamic remodeling of PAR structure

We investigated temporal patterns of axis differentiation, RMMAI composition, and chromatin loop configuration on the PAR using SIM or conventional microscopy (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). The SYCP3-defined axis was already long as soon as it was detectable in leptonema, and the PARb FISH signal was compact and remained so while the axis lengthened further through late zygonema, when the sister axes separated. Throughout, abundant ANKRD31 and REC114 signals stretched along the PAR axes, decorating the compact chromatin (Extended Data Fig. 3a chromosomes a-h, and Extended Data Fig. 3b i-ii). After synapsis, the axes shortened and chromatin loops decompacted, with concomitant RMMAI dissociation. A focus of the meiotic cohesin subunit REC8 was juxtaposed to ANKRD31 blobs at pre-leptonema; REC8 was mostly restricted to the borders of the PAR as its axes elongated and split, and remained highly enriched on the short axis after RMMAI proteins disappeared (Extended Data Fig. 3a chromosomes i-o, and Extended Data Fig. 3b iii-iv). Collapse of the loop–axis structure and REC114 dissociation also occurred when the PAR underwent non-homologous synapsis in a Spo11−/− mutant (Extended Data Fig. 3c), so synapsis without recombination is sufficient for PAR reconfiguration. DSB formation without synapsis may also be sufficient (Supplementary Discussion). These findings delineate large-scale reconfiguration of loop–axis structure and establish spatial and temporal correlations between RMMAI proteins and association of a long axis with compact PAR chromatin.

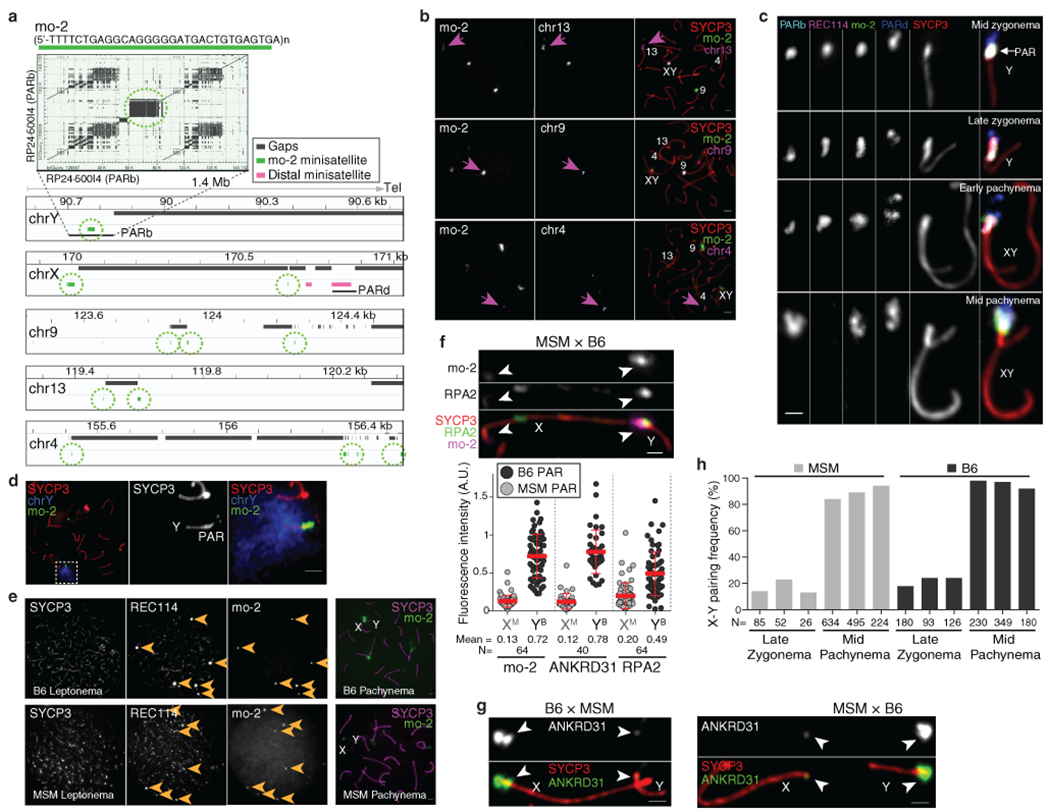

Heterochromatic mo-2 minisatellites

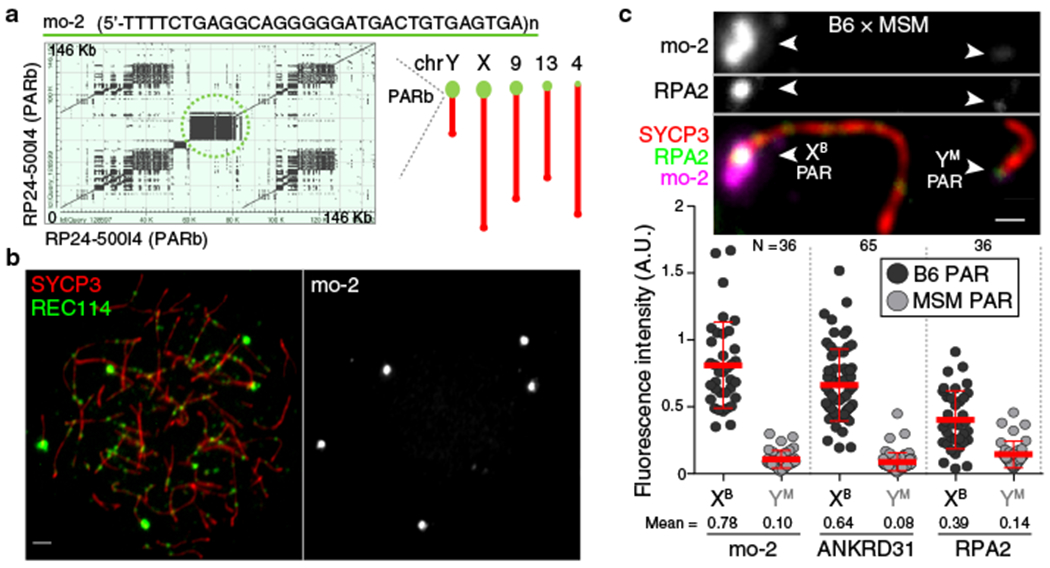

We deduced that specific DNA sequences might recruit RMMAI proteins because autosomal blobs also hybridized to the PARb probe (Extended Data Fig. 1d). This repetitive probe includes a ~20-kb tandem array of a minisatellite called mo-2, with a 31-bp repeat23,24 (Fig. 2a). Clusters of mo-2 are also present at the non-centromeric ends of chr4, chr9, and chr13 (Fig. 2a,b and Extended Data Fig. 4a,b)23,24. FISH with an mo-2 oligonucleotide probe showed that RMMAI blobs colocalize completely with mo-2 arrays (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 4c,d). Mo-2 arrays become enriched at the onset of meiosis for heterochromatic histone modifications (H3K9me3, H4K20me3) and proteins (HP1β, HP1γ, and others), independent of DSB formation (Extended Data Fig. 5).

Fig. 2: Arrays of the mo-2 minisatellite are sites of RMMAI protein enrichment in the PAR and on autosomes.

(a) Left panel: Self alignment of the PARb FISH probe. The circled block is a 20-kb mo-2 cluster. Right panel: Schematic showing the non-centromeric chromosome ends identified by BLAST search using the mo-2 consensus sequence. (b) Colocalization of REC114 blobs with mo-2 oligonucleotide FISH signal (zygotene spermatocyte). Scale bar: 2 μm. (c) PAR enrichment for ANKRD31 and RPA2 correlates with mo-2 copy number. Top panels: late zygotene spermatocyte from F1 hybrid from crosses of B6 × MSM. Scale bars: 1 μm. Bottom panels: PAR-associated signals (A.U., arbitrary units) on B6-derived (XB) and MSM-derived chromosomes (YM) from the indicated number of spermatocytes (N). Red lines: means ± SD. Differences between X and Y PAR intensities are significant for both proteins and for mo-2 FISH (p < 10−6, paired t-test; exact two-sided p values are in Data File S1).

To test if mo-2 arrays are cis-acting determinants of RMMAI recruitment, we exploited the fact that the Mus musculus molossinus subspecies has substantially lower mo-2 copy number24. The MSM/MsJ strain (MSM) showed less hybridization signal than B6 with the mo-2 FISH probe and had lower REC114 intensity in blobs (Extended Data Fig. 4e).

To avoid confounding strain effects, we examined spermatocytes of F1 hybrids (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 4f,g). Less ANKRD31 accumulated on MSM PARs: the YMSM PAR had 8-fold less ANKRD31 than the XB6 PAR in offspring from B6 mothers and MSM fathers (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 4g), and the XMSM PAR had 6.5-fold less than the YB6 PAR in the reciprocal cross (Extended Data Fig. 4f,g). Relative ANKRD31 levels matched mo-2 FISH. Nevertheless, MSM PARs support sex chromosome pairing efficiency and timing similar to B6 (Extended Data Fig. 4h), not surprisingly since MSM is fertile. Interestingly, the ssDNA binding protein RPA2 was present at lower intensity on MSM PARs (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 4f), revisited below.

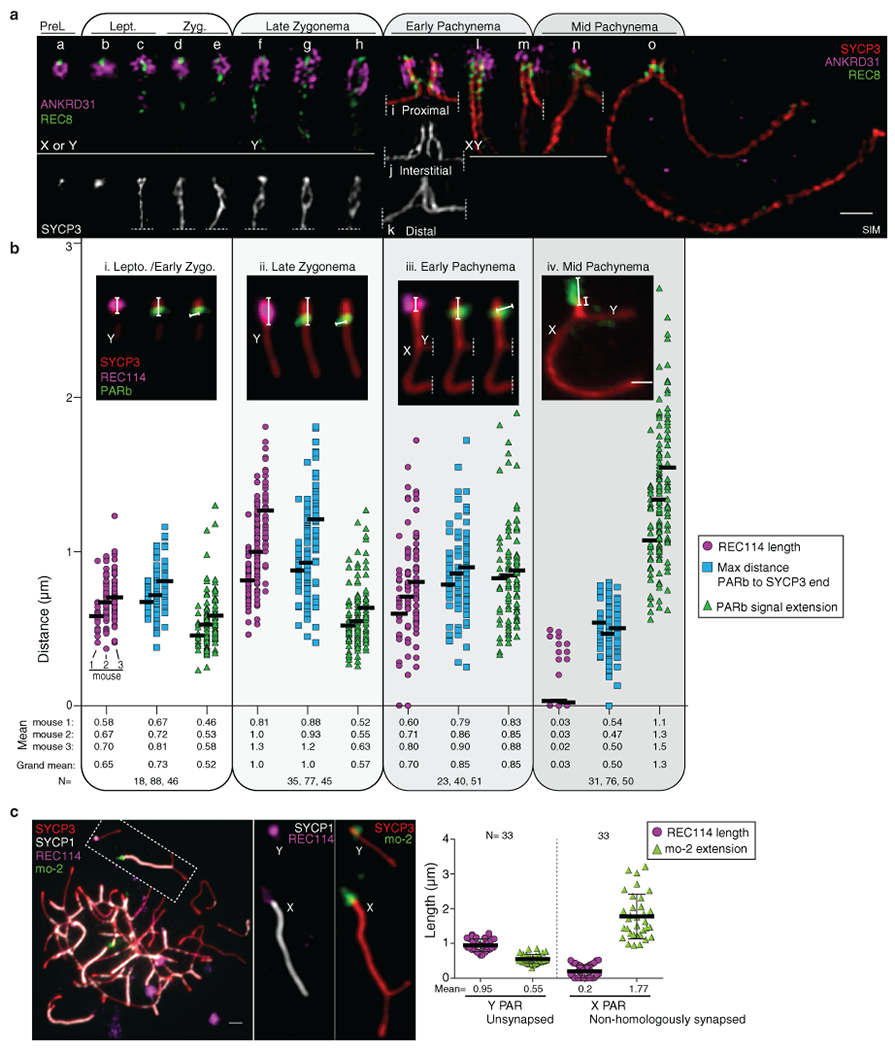

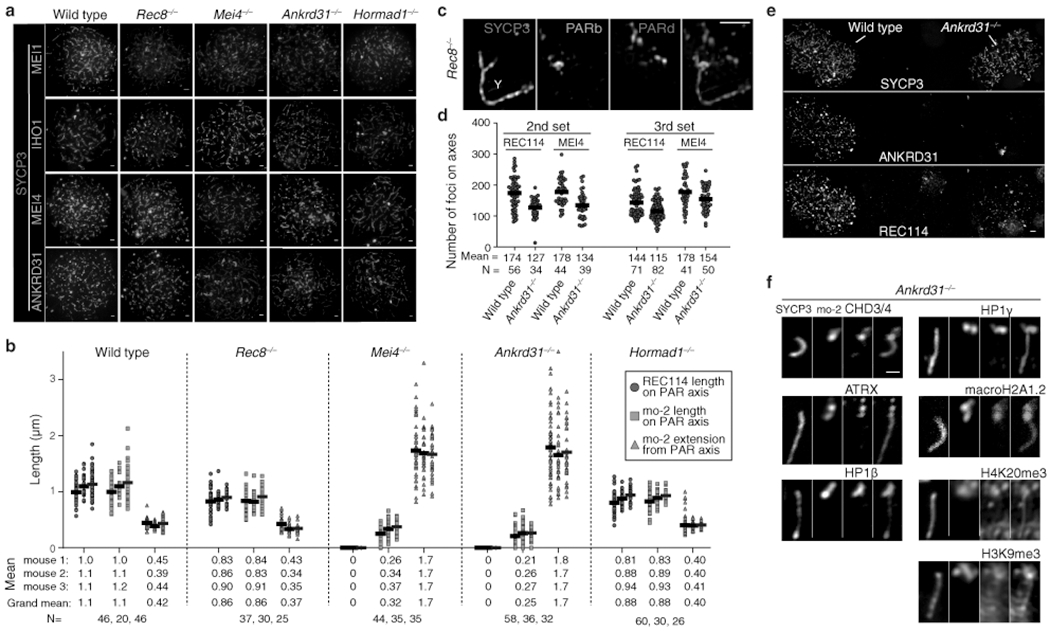

Trans-acting determinants

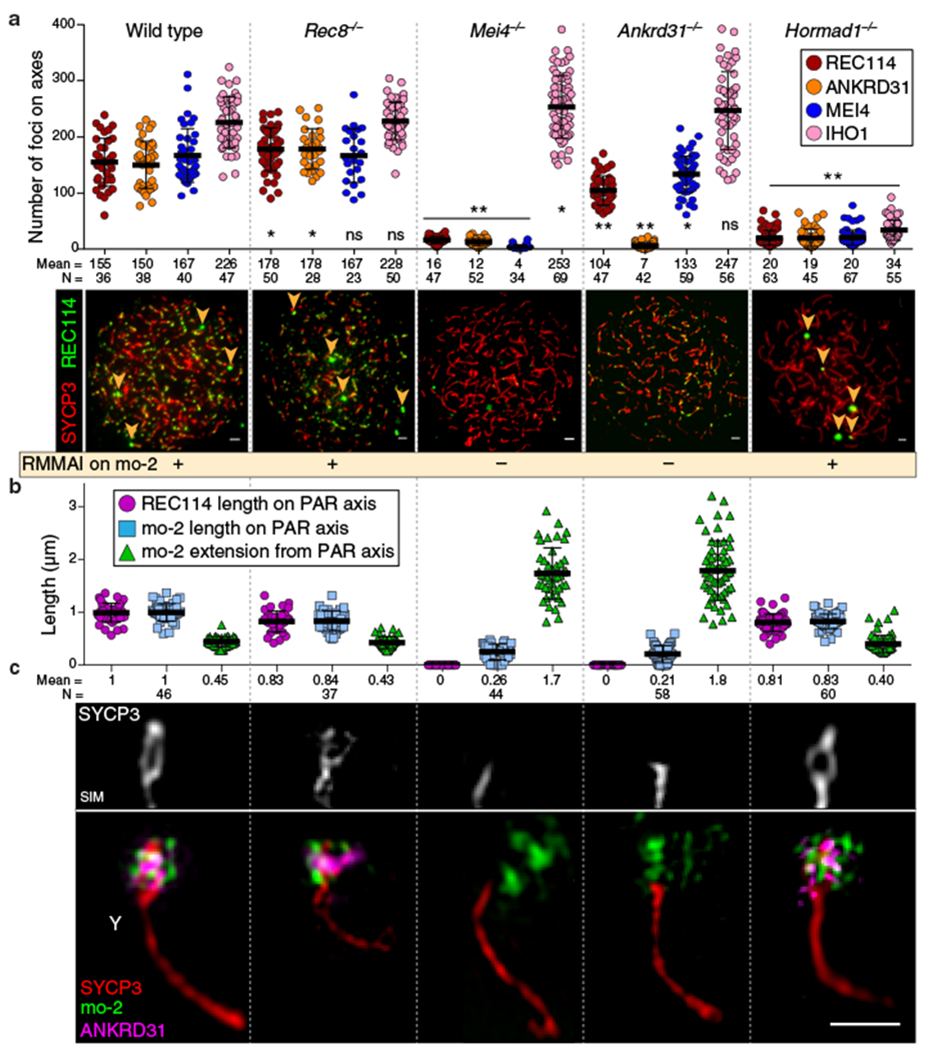

To identify factors important for PAR behavior, we eliminated RMMAI or axis proteins16,20,25,26. Requirements for RMMAI blobs overlap with but are distinct from those for smaller RMMAI foci, for which Hormad1 is important and Mei4 even more so, but Ankrd31 contributes only partially17,20,22 (Fig. 3a). HORMAD1 and REC8 were dispensable for RMMAI assembly on mo-2 regions, PAR axis elongation, splitting of sister axes, and formation of short loops (i.e., compact mo-2 and REC114 signals) (Fig. 3a,b,c and Extended Data Fig. 6a,b). Distal PAR axes were separated in Rec8−/− (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 6c), so REC8 is essential for cohesion at the PAR end.

Fig. 3: Requirements for RMMAI recruitment and PAR axis remodeling.

(a) Quantification of REC114, ANKRD31, MEI4, and IHO1 foci along unsynapsed axes in leptotene/early zygotene spermatocytes. Error bars: means ± SD. Comparisons to wild type are indicated (two-sided Student’s t test): * = p<0.02, ** = p≤10−7, ns = not significant (p>0.05); exact p values are in Data File S2. Representative micrographs of REC114 staining are shown; other proteins are in Extended Data Fig. 6a. Presence of mo-2 associated blobs (arrowheads) is indicated in the bottom panel. Scale bars: 2 μm. (b) Genetic requirements for PAR loop–axis organization (length of REC114 and mo-2 FISH signals along the PAR axis and axis-orthogonal extension of mo-2). Error bars: means ± SD. (c) Representative SIM images of Y-PAR loop–axis structure in each mutant at late zygonema. Scale bar: 1 μm.

The smaller MEI4 and REC114 foci still formed in Ankrd31−/−, but fewer and weaker (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 6a,d,e)20. On mo-2 in contrast, RMMAI proteins did not accumulate detectably in Mei4−/− and Ankrd31−/− (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 6a,b). ANKRD31 was dispensable for enrichment of heterochromatin factors (Extended Data Fig. 6f). REC114, although not IHO1, is similarly essential for RMMAI blobs21. Normal PAR ultrastructure was also absent in Mei4−/− and Ankrd31−/−: axes were short with no sign of splitting and mo-2 was decompacted (Fig. 3b,c and Extended Data Fig. 6b). We conclude that PAR RMMAI blobs share genetic requirements with autosomal mo-2 blobs, and presence of blobs correlates with normal PAR structural differentiation.

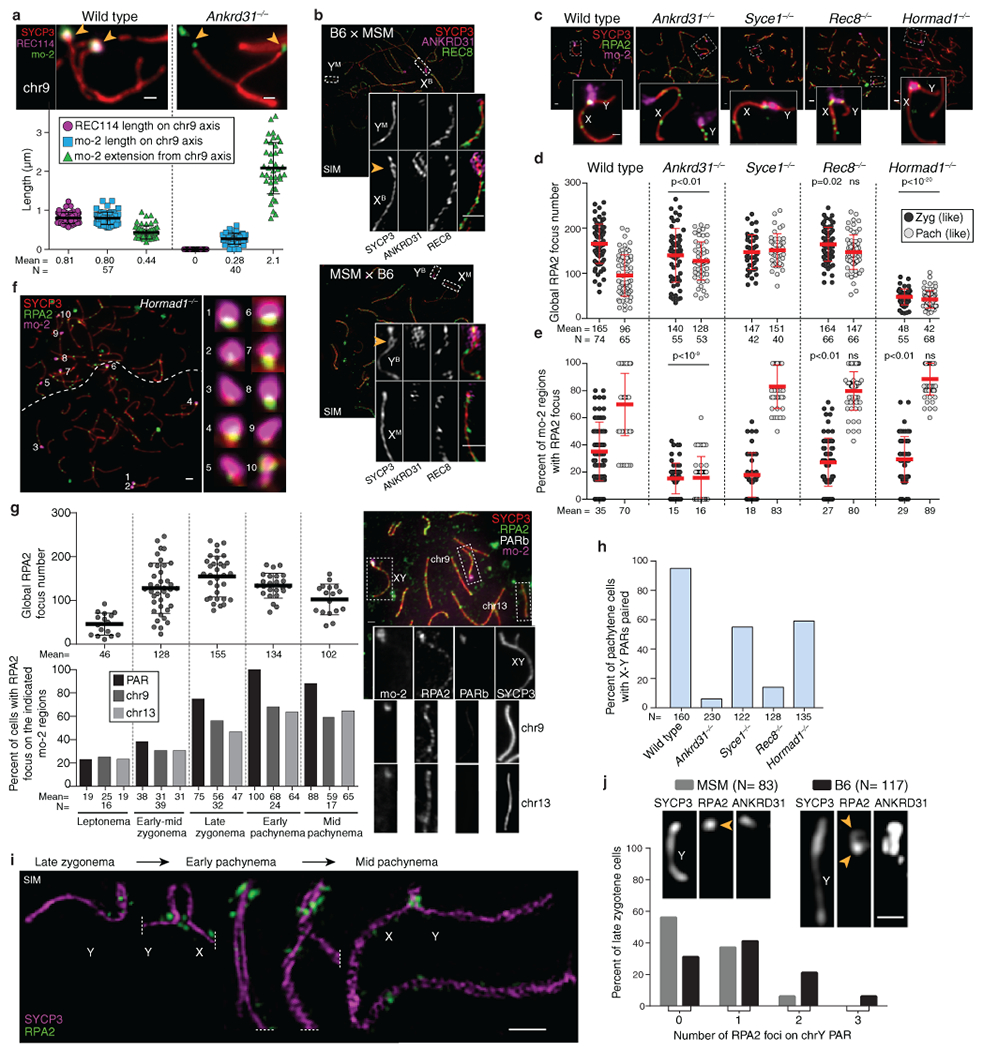

PAR(-like) axis remodeling and mo-2

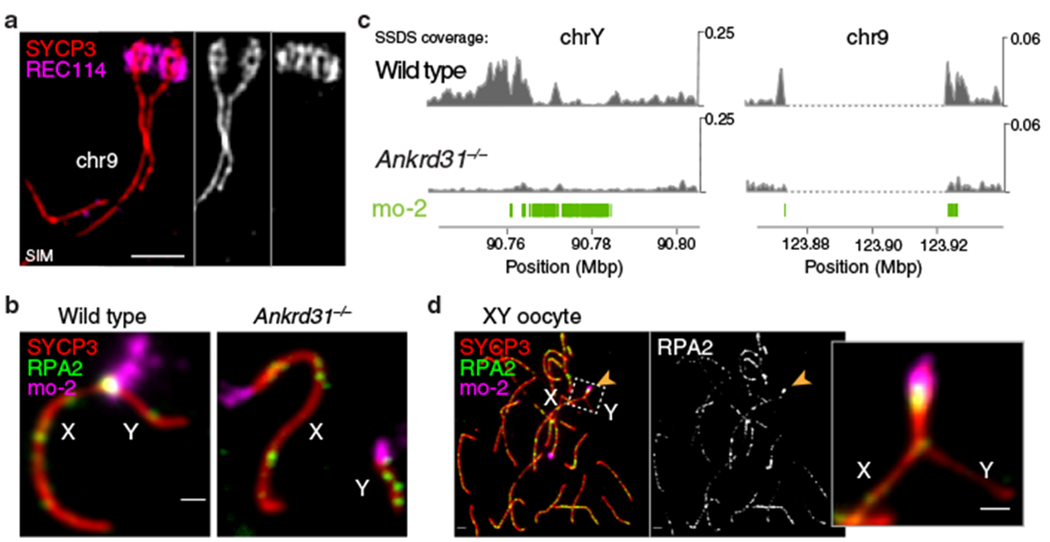

If mo-2 arrays are cis-acting determinants of high-level RMMAI recruitment that in turn governs PAR structural dynamics, then autosomal mo-2 should also form PAR-like structures. Indeed, the distal end of chr9 underwent splitting in spermatocytes where this region was late to synapse (Fig. 4a) and showed a PAR-like pattern of extended axes and compact chromatin dependent on Ankrd31 (Extended Data Fig. 7a). Thus, mo-2 (and/or linked elements) may be sufficient for both RMMAI recruitment and axis remodeling. Less axis remodeling for MSM PARs (Extended Data Fig. 7b) reinforced the correlation between mo-2 copy number, RMMAI levels, and PAR ultrastructure.

Fig. 4: PAR-like structural reorganization and DSB formation on autosomal mo-2 arrays.

(a) The mo-2 region of chr9 undergoes axis elongation and splitting similar to PARs (SIM image of a wild-type zygotene spermatocyte). Scale bar: 1 μm. (b) ANKRD31 is required for high-level DSB formation in mo-2 regions and XY pairing. Immuno-FISH for RPA2 and mo-2 was used to detect DSBs. Illustration from Extended Data Fig. 7c. (c) PAR-like DSB formation near autosomal mo-2 regions. Excerpt from Extended Data Fig. 8a. SSDS coverage7,20 is shown for the Y PAR (left) and the mo-2-adjacent region of chr9 (right). Positions of mo-2 repeats are shown below. (d) Early pachytene XY oocyte showing bright RPA2 focus in the PAR. Scale bar: 2 μm.

DSB formation in spermatocytes

We hypothesized that RMMAI recruitment and axis remodeling create an environment conducive to high-level DSB formation. This idea predicts that mutations should affect all of these processes coordinately and that autosomal mo-2 regions should experience PAR-like DSB formation. We counted axial RPA2 foci as a proxy for global DSB numbers and assessed mo-2 overlap with RPA2 (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 7c–f).

In wild-type zygotene spermatocytes, RPA2 foci overlapped on average 35% of each cell’s mo-2 regions, increasing to 70% at pachynema (Extended Data Fig. 7e). Similar to the PAR2, autosomal mo-2 often acquired DSBs late (Extended Data Fig. 7g). In contrast, Ankrd31−/− mutants had starkly reduced overlap of RPA2 foci with mo-2, so X and Y paired in only 6% of mid-pachytene spermatocytes (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 7e,h). This is distinct from autosomes: global RPA2 foci were only modestly reduced (Extended Data Fig. 7d) and most Ankrd31−/− cells pair and synapse all autosomes20,21. (Ankrd31−/− mutants form fewer RPA2 foci at leptonema and early zygonema, but normal numbers thereafter20,21.)

Rec8 deficiency did not reduce RPA2 focus formation on mo-2 or more globally relative to a synapsis-deficient control (Syce1−/−) (Extended Data Fig. 7c–e). However, X–Y pairing was reduced (Extended Data Fig. 7h), presumably because REC8 promotes interhomolog recombination27. Hormad1−/− spermatocytes had comparable or higher frequencies of mo-2-overlapping RPA2 foci and X–Y pairing as the Syce1−/− control (Extended Data Fig. 7e,h). The high frequency of mo-2 RPA2 foci was striking given the global reduction in RPA2 foci (Extended Data Fig. 7d,f) and DSBs28, but consistent with HORMAD1 dispensability both for RMMAI recruitment to mo-2 and for PAR ultrastructure (Fig. 3a–c).

These findings establish a tight correlation of RMMAI recruitment and axis remodeling with high-frequency DSB formation. Further strengthening this correlation, we noted above that MSM PARs display lower RPA2 intensity (Fig. 2c), perhaps reflecting a lesser tendency to make multiple DSBs. Indeed, multiple PAR RPA2 foci were resolved by SIM more frequently in B6 than MSM (Extended Data Fig. 7i,j).

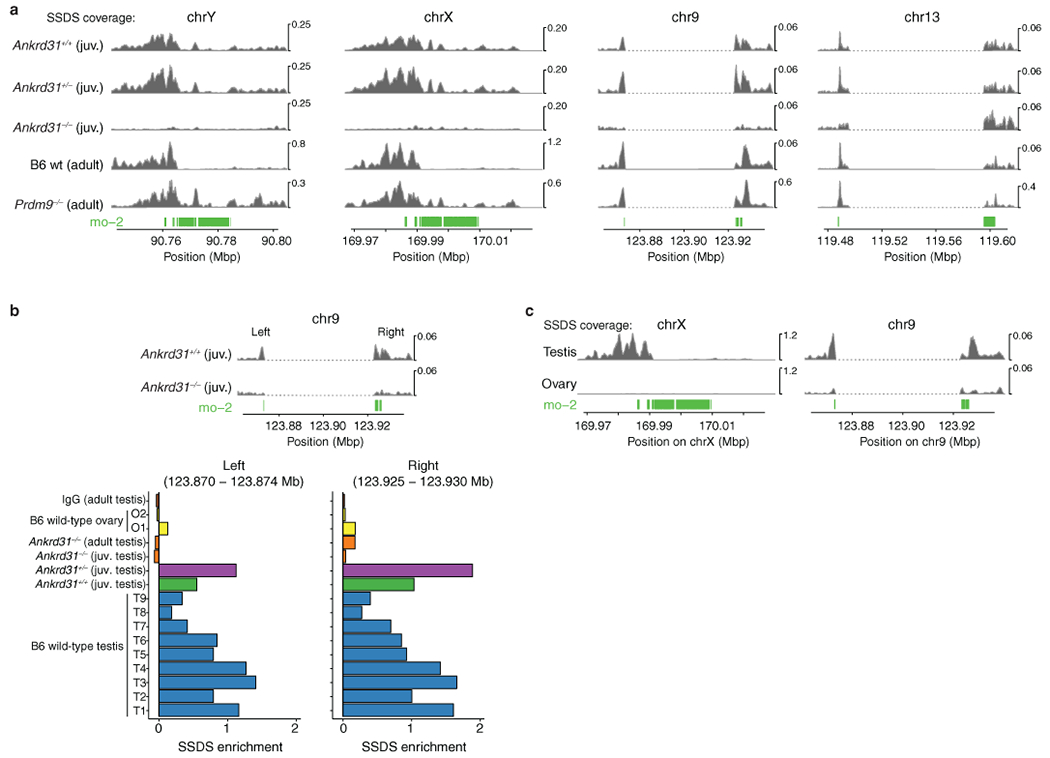

We used maps of ssDNA bound by the strand-exchange protein DMC1 (ssDNA sequencing, or SSDS)7,29,30 to test more directly whether autosomal mo-2 regions experience PAR-like DSB formation, i.e., dependent on ANKRD31 but largely independent of the histone methyltransferase PRDM9 (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 8a)7,20,21. Indeed, the region encompassing the chr9 mo-2 cluster displayed accumulation of SSDS reads that was substantially reduced in Ankrd31−/− but not in Prdm9−/−. A modest ANKRD31-dependent, PRDM9-independent peak was also observed near the mo-2 cluster on chr13 (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Thus, autosomal mo-2 regions not only accumulate PAR-like levels of RMMAI proteins and undergo PAR-like axis remodeling in spermatocytes, they frequently form DSBs in a PAR-like manner.

Mo-2 regions in oocytes

In females, recombination between the two X chromosomes is not restricted to the PAR, so oocytes do not require PAR DSBs like spermatocytes31. We therefore asked whether the PAR undergoes spermatocyte-like structural changes in oocytes. RMMAI proteins robustly accumulated on PAR and autosomal mo-2 regions from leptonema to pachynema (Extended Data Fig. 9a), consistent with studies of MEI4 and ANKRD3116,21. Oocytes also displayed an extended PAR axis and compact PARb FISH signal from leptonema to zygonema and transitioned to a shorter axis and more extended PARb signal in pachynema, with loss of REC114 signal upon synapsis (Extended Data Fig. 9b). Heterochromatin factors were also enriched (Extended Data Fig. 9c). However, we did not detect spermatocyte-like thickening or splitting of the PAR axis or REC8 accumulation (Extended Data Fig. 9d), even in the absence of synapsis in Syce1−/− mutants (Extended Data Fig. 9e). Moreover, similar to the PAR31, autosomal mo-2 regions showed little enrichment for SSDS signal in wild-type ovaries (Extended Data Fig. 8b,c).

Low SSDS signal despite RMMAI enrichment and long axes could indicate that oocytes lack a critical factor(s) that promotes PAR DSBs in spermatocytes. Alternatively, oocyte PARs may not realize their full DSB potential because of negative feedback tied to homolog engagement32,33: perhaps synapsis that initiated elsewhere on X often spreads into the PAR and disrupts the PAR ultrastructure before DSBs can form. To test this idea, we tested effects of delaying or blocking PAR synapsis using sex-reversed XY females34 and Syce1−/− mutants.

XY oocytes pair and synapse their PARs relatively late: only 28% of late zygotene cells had X and Y paired and/or synapsed (25 of 90 cells from two mice), increasing to 66% at pachynema (115 of 174 cells). This late pairing and synapsis is reminiscent of spermatocytes, but appears less efficient. Most pachytene XY oocytes that synapsed their PARs had a PAR-associated RPA2 focus, at twice the frequency and with higher immunofluorescence intensity than in XX oocytes (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 9f). RPA2 foci were also seen on most PARs that failed to synapse (Extended Data Fig. 9g). In contrast, chr9 and chr13 had lower RPA2 frequency and intensity that was comparable to XX PARs and that did not differ between XY and XX (Extended Data Fig. 9f).

These findings suggest that delayed PAR synapsis allows oocytes to more efficiently form DSBs. Supporting this conclusion, absence of synapsis in Syce1−/− oocytes was accompanied by an increase in both the frequency and intensity of RPA2 on PARs and autosomal mo-2 regions alike (Extended Data Fig. 9h). Our results do not exclude the possibility of spermatocyte-oocyte differences in trans-acting factors, but we infer that the ability to manifest high-level DSB formation depends substantially on the result of a race between DSB formation and completion of synapsis (Supplementary Discussion).

Discussion

We demonstrate that the PAR in male mice undergoes a striking rearrangement of loop–axis structure prior to DSB formation involving recruitment of RMMAI proteins, dynamic axis elongation, and splitting of sister chromatid axes (Extended Data Fig. 10). Most of these behaviors also occur in oocytes and can support high-level DSB formation if synapsis is delayed. The mo-2 array may be a key cis-acting determinant and RMMAI proteins are crucial trans-acting determinants. Although the function of sister axis splitting is unclear (Supplementary Discussion), the full suite of PAR behaviors appears essential for pairing, recombination, and segregation of heteromorphic sex chromosomes.

Budding yeast also uses robust recruitment of Rec114 and Mer2 (the IHO1 ortholog) to ensure that its smallest chromosomes incur DSBs35. Thus, such preferential recruitment is an evolutionarily recurrent strategy for mitigating risk of recombination failure when the length of chromosomal homology is limited.

RMMAI hyper-accumulation may reflect binding of one or more of these proteins to an mo-2-associated chromatin structure and/or direct binding to mo-2 repeats or another tightly linked DNA element. We note that the repetitive mo-2 array imposes risks of unequal exchange23,36. Thus, paradoxically, the PAR DNA structure stabilizes the genome by supporting sex chromosome segregation but also promotes the rapid evolution of mammalian PARs4.

METHODS

Mice

Mice were maintained and sacrificed under U.S.A. regulatory standards and experiments were approved by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, protocol number 01–03-007). Animals were fed regular rodent chow with ad libitum access to food and water. The Ankrd31 knockout allele (Ankrd31em1Sky) is a single base insertion mutation (+A) in exon 3; its generation and phenotypic characterization are described elsewhere20. Mice with the Mei4 knockout allele16 were kindly provided by B. de Massy (IGH, Montpellier, France). All other mouse strains were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory: C57BL/6J (stock #00664), MSM/MsJ (stock #003719), B6N(Cg)-Syce1tm1b(KOMP)Wtsi/2J (stock #026719), B6;129S7-Hormad1tm1Rajk/Mmjax (stock #41469-JAX), B6;129S4-Rec8mei8/JcsMmjax (stock #34762-JAX), B6.Cg-Tg(Sry)2Ei Srydl1Rlb/ArnoJ (stock #010905). Mice were genotyped using Direct Tail lysis buffer (Viagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

B6.Cg-Tg(Sry)2Ei Srydl1Rlb/ArnoJ males have a Y chromosome with a deletion of the sex-determining Sry gene and also have an Sry transgene integrated on an autosome. When these males are crossed with C57BL/6J females, those XY and XX animals that do not inherit the Sry transgene develop as females.

Generation of REC8 and REC114 antibodies

To produce antibodies against REC8, a fragment of the mouse Rec8 gene encoding amino acids 36 to 253 (NCBI Reference Sequence: NP_001347318.1) was cloned into pGEX-4T-2 vector. The resulting fusion of the REC8 fragment fused to glutathione S tranferase (GST) was expressed in E. coli, affinity purified on glutathione Sepharose 4B, and cleaved with Precision protease. Antibodies were raised in rabbits by Covance Inc. (Princeton NJ) against the purified recombinant REC8 fragment, and antibodies were affinity purified using GST-REC836-253 that had been immobilized on glutathione sepharose by crosslinking with dimethyl pimelimidate; bound antibodies were eluted with 0.1 M glycine, pH 2.5. Purified antibodies were tested in western blots of testis extracts and specificity was validated by immunostaining of spread meiotic chromosomes from wild type and Rec8−/− mice.

To produce antibodies against REC114, a fragment of the mouse Rec114 gene encoding a truncated polypeptide lacking the N-terminal 110 amino acids (NCBI Reference Sequence: NP_082874.1) was cloned into pET-19b expression vector. The resulting hexahistidine-tagged REC114111-259 fragment was insoluble when expressed in E. coli, so the recombinant protein was solubilized and affinity purified on Ni-NTA resin in the presence of 8 M urea. Eluted protein was dialyzed against 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 6 M urea, pH 7.3 and used to immunize rabbits (Covance Inc.). Antibodies were affinity purified against purified recombinant His6-REC114111-259 protein immobilized on cyanogen bromide-activated sepharose and eluted in 0.2 M glycine pH 2.5. The affinity purified antibodies were previously used by Stanzione et al.17 who reported detection of a band of appropriate molecular weight in western blots of testis extracts. However, subsequent analysis showed that this band is also present in extracts of Rec114−/− testes, and thus is non-specific (C. Brun and B. de Massy, personal communication). Importantly, however, Stanzione et al. also reported detection of immunostaining foci on spread meiotic chromosomes similar to findings reported here and by Boekhout et al.20. This immunostaining signal is absent from chromosome spreads prepared from Rec114−/− mutant mice (C. Brun and B. de Massy, personal communication). Moreover, this immunostaining signal is indistinguishable from that reported using independently generated and validated anti-REC114 antibodies19. We conclude that our anti-REC114 antibodies are highly specific for the cognate antigen when used for immunostaining of meiotic chromosome spreads.

Chromosome spreads

Testes were dissected and deposited after removal of the tunica albuginea in 1× PBS pH 7.4. Seminiferous tubules were minced using forceps to form a cell suspension. The cell suspension was filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer into a 15 ml Falcon tube pre-coated with 3% (w/v) BSA, and was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in 12 ml of 1× PBS for an additional centrifugation step at 1000 rpm for 5 min and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of hypotonic buffer containing 17 mM sodium citrate, 50 mM sucrose, 30 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 5 mM EDTA pH 8, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 μl of 100× Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific), and incubated for 8 min. Next, 9 ml of 1× PBS was added and the cell suspension was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in 100 mM sucrose pH 8 to obtain a slightly turbid cell suspension, and incubated for 10 min. Superfrost glass slides were divided into two squares using an ImmEdge hydrophobic pen (Vector Labs), then 110 μl of 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (freshly dissolved in presence of NaOH at 65°C, 0.15% Triton, pH 9.3, cleared through 0.22 μm filter) and 30 μl of cell suspension was added per square, swirled three times for homogenization, and the slides were placed horizontally in a closed humid chamber for 2 h. The humid chamber was opened for 1 h to allow almost complete drying of the cell suspension. Slides were washed in a Coplin jar 2 × 5 min in 1× PBS on a shaker, and 2 min with 0.4% Photo-Flo 200 solution (Kodak), air dried and stored in aluminum foil at −80°C.

Ovaries were extracted from 14.5–18.5 d post-coitum mice, and collected in 1× PBS pH 7.4. After 15 min incubation in hypotonic buffer, the ovaries were placed on a slide containing 30 μl of 100 mM sucrose pH 8, and dissected with forceps to form a cell suspension. The remaining tissues were removed, 110 μl of 1% paraformaldehyde-0.15% Triton was added, and the slides were gently swirled for homogenization, before incubation in a humid chamber as described above for spermatocyte chromosome spreads.

Immunostaining

Slides of meiotic chromosome spreads were blocked for 30 min at room temperature horizontally in a humid chamber with an excess of blocking buffer containing 1× PBS, pH 7.4 with 0.05% Tween-20, 7.5% (v/v) donkey serum, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, and 0.05% (w/v) sodium azide, and cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min. Slides were incubated with primary antibody overnight in a humid chamber at 4°C, or for at least 3 hours at room temperature. Slides were washed 3 × 5 min in 1× PBS, 0.05% Tween-20, then blocked for 10 min, and incubated with secondary antibody for 1–2 hours at 37°C in a humid chamber. Slides were washed 3 × 5 min in the dark on a shaker with 1× PBS, 0.05% Tween-20, rinsed in H2O, and mounted before air drying with Vectashield (Vector Labs). Antibody dilutions were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for at least 5 min before use. Primary antibodies used were rabbit and guinea pig anti-ANKRD3120 (1:200 dilution), rabbit anti-HORMAD2 (Santa Cruz, sc-82192, 1:50), guinea pig anti-HORMAD2 (1:200) and guinea pig anti-IHO1 (1:200) (gifts from A. Toth (Technical University of Dresden)), goat anti-MEI1 (Santa Cruz, sc-86732, 1:50), rabbit anti-MEI4 (gift from B. de Massy, 1:200), rabbit anti-REC8 (this study, 1:100), rabbit anti-REC114 (this study, 1:200), rabbit anti-RPA2 (Santa Cruz, sc-28709, 1:50), goat anti-SYCP1 (Santa Cruz, sc-20837, 1:50), rabbit anti-SYCP2 (Atlas Antibodies, HPA062401, 1:100), mouse anti-SYCP3 (Santa Cruz, sc-74569, 1:100), goat anti-SYCP3 (Santa Cruz, sc-20845, 1:50), rabbit anti-TRF1 (Alpha Diagnostic, TRF12-S, 1:100), rabbit anti-H4K20me3 (Abcam, ab9053, 1:200), rabbit anti-H3K9me3 (Abcam, ab8898, 1:200), mouse anti-macroH2A1.2 (Active motif, 61428, 1:100), mouse anti-HP-1 gamma (Millipore, MAB3450, 1:100), mouse anti-HP1-beta (Millipore, MAB3448, 1:100), rabbit anti-HP1-beta (Genetex, GTX106418, 1:100), rabbit anti-Mi2 (recognizes CHD3 and CHD4; Santa Cruz, sc-11378, 1:50), rabbit anti-ATRX (Santa Cruz, sc-15408, 1:50), mouse anti-DMRT1 (Santa Cruz, sc-377167, 1:50), rabbit anti-ZMYM3 (Abcam, ab19165, 1:300), rabbit anti-PAXIP1 (EMD Millipore, ABE1877, 1:300). Secondary antibodies used were CF405S anti-guinea pig (Biotium, 20356), CF405S anti-rabbit (Biotium, 20420), CF405S anti-mouse (Biotium, 20080), Alexa Fluor488 donkey anti-mouse (Life technologies, A21202), Alexa Fluor488 donkey anti-rabbit (Life technologies, A21206), Alexa Fluor488 donkey anti-goat (Life technologies, A11055), Alexa Fluor488 donkey anti-guinea pig (Life technologies, A11073), Alexa Fluor568 donkey anti-mouse (Life technologies, A10037), Alexa Fluor568 donkey anti-rabbit (Life technologies, A10042), Alexa Fluor568 goat anti-guinea pig (Life technologies, A11075), Alexa Fluor594 donkey anti-mouse (Life technologies, A21203), Alexa Fluor594 donkey anti-rabbit (Life technologies, A21207), Alexa Fluor594 donkey anti-goat (Life technologies, A11058), Alexa Fluor647 donkey anti-rabbit (Abcam, ab150067), Alexa Fluor647 donkey anti-goat (Abcam, ab150131), all at 1:250 dilution.

ImmunoFISH and DNA probe preparation

All steps were performed in the dark to prevent loss of fluorescence from prior immunostaining. After the last washing step in the immunostaining protocol, slides were placed horizontally in a humid chamber and the chromosome spreads were re-fixed with an excess of 2% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS (pH 9.3) for 10 min at room temperature. Slides were rinsed once in H2O, washed for 4 min in 1× PBS, sequentially dehydrated with 70% (v/v) ethanol for 4 min, 90% ethanol for 4 min, 100% ethanol for 5 min, and air dried vertically for 5–10 min. Next, 15 μl of hybridization mix was applied containing the DNA probe(s) in 70% (v/v) deionized formamide (Amresco), 10% (w/v) dextran sulfate, 2× SSC buffer (saline sodium citrate), 1× Denhardt’s buffer, 10 mM EDTA pH 8 and 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4. Cover glasses (22 x 22 mm) were applied and sealed with rubber cement (Weldwood contact cement), then the slides were denatured on a heat block for 7 min at 80°C, followed by overnight incubation (>14 h) at 37°C. Cover glasses were carefully removed using a razor blade, slides were rinsed in 0.1× SSC buffer, washed in 0.4× SSC, 0.3% NP-40 for 5 min, washed in PBS–0.05% Tween-20 for 3 min, rinsed in H2O, and mounted with Vectashield before air drying.

To generate FISH probes, we used the nick translation kit from Abbott Molecular following the manufacturer’s instructions and using CF dye-conjugated dUTP (Biotium), on BAC DNA from the clones RP24-500I4 (maps to the region of the PAR boundary, PARb probe) CH25-592M6 (maps to the distal PAR, PARd probe), RP23-139J18, RP24-136G21, and CH36-200G6 (centromere-distal ends of chr4, chr9, and chr13, respectively). BAC clones were obtained from the BACPAC Resource Center (CHORI). Labeled DNA (500 ng) was precipitated during 30 min incubation at −20°C after adding 5 μl of mouse Cot-1 DNA (Invitrogen), 0.5 volume of 7.5 M ammonium acetate and 2.5 volumes of cold 100% ethanol. After washing with 70% ethanol and air drying in the dark, the pellet was dissolved in 15 μl of hybridization buffer.

Mo-2 oligonucleotide probes were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, with 6-FAM or TYE™ 665 fluorophores added to both 5′ and 3′ ends of the oligonucleotide. The DNA sequence was designed based on the previously defined consensus sequence24, and the probe was used at a final concentration of 10 pmoll in hybridization buffer without Cot-1 DNA. The Y-chromosome paint probe was purchased from IDLabs and used at 1:30 dilution in hybridization buffer without Cot-1 DNA.

EdU incorporation

Seminiferous tubules were incubated in DMEM with 10% FCS and 10 μM EdU at 37°C for 1 h for in vitro labeling. EdU incorporation was detected using the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 647 imaging kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Image acquisition

Images of spread spermatocytes were acquired on a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 Marianas Workstation, equipped with an ORCA-Flash 4.0 camera and DAPI, CFP, FITC, TEXAS red and Cy5 filter sets, illuminated by an X-Cite 120 PC-Q light source, with either 63×/1.4 NA oil immersion objective or 100×/1.4 NA oil immersion objective. Marianas Slidebook 5.0 (Intelligent Imaging Innovations) software was used for acquisition.

Structured illumination microscopy (3D-SIM) was performed at the Bio-Imaging Resource Center in Rockefeller University using an OMX Blaze 3D-SIM super-resolution microscope (Applied Precision), equipped with 405 nm, 488nm and 568 nm lasers, and 100×/1.40 NA UPLSAPO oil objective (Olympus). Image stacks of several μm thickness were taken with 0.125 μm z-steps, and were reconstructed in Deltavision softWoRx 6.1.1 software with a Wiener filter of 0.002 using wavelength specific experimentally determined OTF functions. Slides were prepared and stained as described above, except that chromosomes were spread only on the central portion of the slides, and the slides mounted using 18 × 18 mm coverslips (Zeiss).

Image analysis

3D-SIM images are shown either as a z-stack using the sum slices function in Fiji/ImageJ, or as a unique slice. The X and/or Y chromosomes were cropped, rotated and further cropped for best display. For montage display, the X and Y chromosome images were positioned on a black background using Adobe Illustrator 2020 (version 24.1). In the instances where the axes of the X and Y chromosomes were cropped, the area of cropping was labeled with a light gray dotted line. Loop/axis measurements, foci counts, and fluorescence intensity quantification were only performed on images from conventional microscopy using the original, unmodified data.

To measure the colocalization between RMMAI proteins, we costained for SYCP3 and ANKRD31 along with either MEI4, REC114, or IHO1, and manually counted the number of ANKRD31 foci overlapping with SYCP3 and colocalizing or not with MEI4, REC114 or IHO1. These counts were performed in 16 spermatocytes from leptonema to early/mid zygonema.

To quantify the total number of RPA2, MEI4, REC114, ANKRD31, and IHO1 foci, single cells were manually cropped and analyzed with semi-automated scripts in Fiji37 (version 2.0.0-rc-69/1.52p) as described in detail elsewhere20. Briefly, images were auto-thresholded on SYCP3 staining, which was used as a mask to use ‘Find Maxima’ to determine the number of foci. Images were manually inspected to determine that there were no obvious defects in determining SYCP3 axes, that no axes from neighboring cells were counted, that no artifacts were present, and that no foci were missed by the script.

To test for colocalization between RPA2 and mo-2 FISH signals, we manually scored the percentage of mo-2 FISH signals colocalizing at least partly with RPA2. Depending on the progression of synapsis during prophase I, between eight and four discrete mo-2 FISH signals could be detected, corresponding to (with increasing signal intensity) the chr4, chr13, chr9, and the PAR (two signals for each when unpaired, or a single signal for each after homologous pairing/synapsis). Notably, the RPA2 focus was most often found in a slightly more centromere-proximal position compared to the bulk of mo-2 FISH signals, and therefore colocalized partly with mo-2 FISH signals. In the case of the PAR, this position corresponds closely to the region of the PAR boundary (PARb probe). A similar trend was observed on autosomal mo-2 clusters.

For estimates of chromatin extension, we measured the maximal axis-orthogonal distance between the FISH signal and the center of the PAR axis, or the centromere-distal axis for chr9 stained by SYCP3. In mutant mice defective for RMMAI protein recruitment in the mo-2 regions, the PAR axis was defined as the nearest SYCP3 segment adjacent to the telomeric SYCP3 signal.

For quantification of RPA2, ANKRD31, REC8, and mo-2 signal intensity in B6 × MSM and MSM × B6 F1 hybrids, late zygotene spermatocytes with at least one RPA2 focus on X or Y PAR were analyzed. We used the elliptic selection tool in Fiji to define a region of interest around the largest signal in the PAR, and the same selection tool was then positioned on the other PAR axis for comparison. The fluorescence intensity was measured as the integrated density with background substraction.

Prophase I sub-staging and identification of the PAR

Nuclei were staged according to the dynamic behavior of the autosome and sex chromosome axes during prophase I, using SYCP3 staining. Leptonema was defined as having short stretches of SYCP3 but no evidence of synapsis, early/mid-zygonema as having longer stretches of SYCP3 staining and some synapsis, and late zygonema as having fully assembled chromosome axes and substantial (>70%) synapsis. The X and Y chromosomes generally can be identified at this stage, and the PAR axis is distinguishable because it appears thicker than the centromeric end, particularly near the end of zygonema when autosomes are almost fully synapsed. Early pachynema was defined as complete autosomal synapsis, whereas the X and Y chromosomes could display various configuration: i) unsynapsed, with thickened PAR axes, ii) engaged in PAR synapsis, iii) synapsed in the PAR and non-homologously synapsed along the full (or nearly full) Y chromosome axis. Mid pachynema was defined as showing bright signal from autosome axes, desynapsing X and Y axes remaining synapsed only in the PAR, with short PAR axis. During this stage, the autosomes and the non-PAR X and Y axes are initially short and thick, and progressively become longer and thinner. Late pachynema was defined as brighter autosome axes with a characteristic thickening of all autosome ends. The X and Y non-PAR axes are then long and thin and show excrescence of axial elements. Diplonema was defined as brighter axes and desynapsing autosome, associated with prominent thickening of the autosome ends, particularly the centromeric ends. In early diplonema, the non-PAR axes of X and Y chromosomes are still long and thin and progressively condense to form bright axes, associated with bulges. Most experiments were conducted using SYCP3 in combination with a RMMAI protein, which allows easier distinction between synapsing and desynapsing X and Y chromosomes.

By using only SYCP3 staining, the PARs can only be identified unambiguously from the late zygonema-to-early pachynema transition through to diplonema. From pre-leptonema to mid/late-zygonema, the PARs were identified as the two brightest RMMAI signals, the two brightest mo-2 FISH signals, the two brightest PARb FISH signals, or the two FISH signals from the PARd probe. The Y PAR could be distinguished from the X PAR using the PARb probe, as this probe also weakly stains the chromatin of the non-PAR portion of the Y chromosome.

PAR loop/axis measurements in oocytes were performed on two 14.5–15.5 dpc (days post-coitum) (enriched for leptotene and zygotene oocytes) and two 18.5 dpc female fetuses (enriched for pachytene oocytes).

We found significant variability in the X or Y PAR axis length between different animals in our mouse colony maintained in a C57BL/6J congenic background, and even between different C57BL/6J males obtained directly from the Jackson Laboratory. This is in agreement with previous reports about the hypervariable nature of the mo-2 minisatellite and its involvement in unequal crossing over in the mouse6,24,36,38,39 (mo-2 was also named DXYmov15 or Mov15 flanking sequences). However, the RMMAI signal intensity/elongation and the PAR axis length were always correlated with mo-2 FISH signal intensity. Importantly, despite this variability, mo-2 and RMMAI proteins were enriched in the PAR and autosome ends of all mice analyzed.

Analysis of SSDS data

SSDS sequencing data were from previously described studies7,20,31 and are all available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository under accession numbers GSE35498, GSE99921, GSE118913. To define enrichment values presented in Extended Data Fig. 8b, the SSDS coverage was summed across the indicated coordinates adjacent to the mo-2 repeats. A chromosomal mean and standard deviation for chr9 was estimated by dividing the chromosome into 4-kb bins, summing the SSDS coverage in each bin, and calculating the mean and standard deviation after excluding those bins that overlapped a DSB hotspot. The enrichment score was then defined as the difference between the coverage in the mo-2-adjacent region and the chr9 mean coverage, divided by the chr9 standard deviation.

Immunoprecipitation/mass spectrometry

Immunoprecipitations were carried out on samples from wild type and Ankrd31−/− animals using two separate polyclonal anti-ANKRD31 antibodies raised in rabbit and guinea pig20 (four samples total). Two additional immunoprecipitations were performed using an anti-Cyclin B3 antibody on either wild-type or Ccnb3 knockout testes40,41; these samples serve as additional negative controls for the ANKRD31 interaction screen. For each sample, protein extracts were prepared from testes of three 12-dpp mice in 1 ml of RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 units of Benzonase for 1h at 4°C. After centrifugation at 13,000rpm for 20 min at 4°C, the lysate was pre-cleared using 30μl of a slurry of protein A/G Dynabeads for 1h at 4°C. Next, 50μl of protein A/G beads coupled for 30 min with 10μg of anti-ANKRD31 or anti-Cyclin B3 antibody (monoclonal antibody #5 from ref. 43) were added and the solution incubated overnight at 4°C on a rotating rack. Beads were washed 3 times in 1 ml of RIPA buffer and once with 1 ml of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Samples were then digested overnight with 2μg trypsin in 80 μl of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate at 37°C on a thermo mixer (850 rpm). Peptides were desalted using C18 zip tips, and then dried by vacuum centrifugation. Each sample was reconstituted in 10 μl 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid and 4 μl was analyzed by microcapillary liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry using the NanoAcquity (Waters) with an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 Column (Waters) configured with an ACQUITY UPLC M-Class Symmetry C18 trap column (Waters) coupled to a QExactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were eluted with a linear gradient of 0–35% acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid) in water (0.1% formic acid) over 150 min with a flow rate of 300 nl/min. The QE Plus was operated in automatic, data dependent MS/MS acquisition mode with one MS full scan (380–1800 m/z) at 70,000 mass resolution and up to ten concurrent MS/MS scans for the ten most intense peaks selected from each survey scan. Survey scans were acquired in profile mode and MS/MS scans were acquired in centroid mode at 17,500 resolution and isolation window of 1.5 amu and normalized collision energy of 27. AGC was set to 1 × 10 for MS1 and 5×10 and 100 ms IT for MS2. Charge exclusion of unassigned and greater than 6 enabled with dynamic exclusion of 15 s. All MS/MS samples were analyzed using MaxQuant (Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Martinsried, Germany; version 1.5.3.3) at default settings with a few modifications.

Yeast two-hybrid assay

Mouse testis cDNAs for Ptip, Zmym3, and Ankrd31 were amplified and cloned in vectors to generate fusion proteins with the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (Gal4BD) or activation domain (Gal4AD). Assays were conducted according to manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech). Briefly, Y2HGold and Y187 (Clontech) yeast haploid strains were transformed with constructs encoding Gal4BD and Gal4AD fusion proteins. After mating on YPD plates, diploid cells expressing Gal4BD and Gal4AD fusion proteins were selected on double dropout medium (DDO) lacking leucine and tryptophan. Protein interactions were assayed by spotting diploid cell suspensions on selective medium lacking leucine, tryptophan, histidine, and adenine (quadruple dropout, QDO), and QDO containing X-α-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl α-D-galactopyranoside) and aureobasidin A and growing for 3 days at 30°C.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were performed in R (version 3.4.4)42 and RStudio (Version1.1.442). Negative binomial regression was calculated using the glm.nb function from the MASS package (version 7.3–49)43.

Statistics and reproducibility

The pictures shown in this article are representative images that aim to illustrate the findings in the clearest manner. Any conclusion or statement regarding the results that is not associated with explicit quantification is based on the imaging and analysis of at least 20 cells, sometimes hundreds, usually from multiple mice. Details for main figures are as follows.

Fig. 1a: The thickening of the PAR axis (using SYCP3 staining) and the elongation of the RMMAI signal along the PAR axis have been observed in more than three different mice in hundreds of late zygotene spermatocytes using mostly our homemade antibodies against REC114 and ANKRD31. Other antibodies such as anti-SYCP2 and anti-HORMAD2 were used to confirm the PAR axis thickening, and anti-MEI1, anti-MEI4 and anti-IHO1 were used to confirm the elongation of the REC114/ANKRD31 signal along the PAR axis, in more than 20 spermatocytes for each antibody.

Fig. 1b: The PAR axis splitting, the extension of the RMMAI signal and the collapse of the PAR structure during X-Y synapsis have been observed by SIM in more than 60 spermatocytes in more than 3 different mice.

Fig. 2b: The colocalization between REC114 blobs (or RMMAI blobs in general) and mo-2 FISH signals has been observed in all spermatocytes analyzed (N>200), from leptotene to early pachytene in more than three different mice.

Fig. 3c: Axis splitting on the Y PAR has been observed by SIM in more than 100 late zygotene spermatocytes and in more than 20 zygotene-like spermatocytes from Hormad1−/− mice. The fork-shaped PAR structure in Rec8−/− mice has been observed in more than 20 spermatocytes. The absence of PAR differentiation and decompaction of mo-2-containing chromatin was observed in more than 30 Ankrd31−/− spermatocytes and 20 Mei4−/− spermatocytes. This specific pattern has been confirmed in at least three different mice of each genotype using conventional microscopy. The differentiation of the PAR axis becomes hardly detectable in Hormad1−/− at later stage in some pachytene-like spermatocytes as cells enter apoptosis, similar to Spo11−/−.

Fig. 4a: The differentiation of the non-centromeric end of the chr9 was observed in 6 spermatocytes by SIM and was observed in more than 20 late zygotene spermatocytes by conventional microscopy in three different mice.

Data and code availability

Image analysis scripts are available on Github: https://github.com/Boekhout/ImageJScripts. SSDS data are publicly available at GEO under the accession numbers indicated above. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository44 with the dataset identifier PXD017191.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1: PAR axis thickening and accumulation of RMMAI proteins.

(a) Axis thickening (SYCP3 and HORMAD2 staining) on the PAR (arrowhead) in a late zygotene spermatocyte. Scale bar: 2 μm. HORMAD2 staining in the PAR at late zygonema mimics SYCP3 staining in all late zygonema spermatocytes analyzed (N>20) in three mice. (b) Image adapted under Creative Commons CC-BY license from ref.45 showing enrichment of HORMAD1 on the thick PAR axis of the Y chromosome. (c) Colocalization of ANKRD31 and MEI4, REC114, IHO1, and MEI1. Representative zygotene spermatocytes are shown. Arrowheads indicate densely staining blobs. Areas indicated by dashed boxes are shown at higher magnification. The graphs show the total number of foci colocalized in leptotene/zygotene spermatocytes (error bars are mean ± SD). N.D., not determined: The low immunofluorescence signal for MEI1 did not allow us to quantify the colocalization with ANKRD31, although MEI1 showed clear colocalization with ANKRD31 in the blobs and at least some autosomal foci (insets). Scale bars: 2 μm. Underlying data for all graphs are in Data Files S1–4. Further evidence for extensive colocalization with ANKRD31 is documented in separate studies20,21. (d) PARb FISH probe colocalizes with REC114 blobs. Two blobs are on PAR, as judged by chromosome morphology and bright fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with a PAR boundary probe (PARb) and others highlight specific autosome ends. Scale bar: 2 μm. The colocalization between REC114 blobs and PARb FISH signals has been observed in all spermatocytes analyzed (N>60), from pre-leptonema to early pachynema, in more than three mice. (e) ANKRD31, REC114, and MEI1 immunostaining starts to appear in pre-leptonema. Seminiferous tubules were cultured with 5-ethynyl-3-deoxyuridine (EdU) to label replicating cells, then chromosome spreads were stained for SYCP3 and either MEI1 plus REC114 or ANKRD31 plus PARb FISH. Colocalized foci appear in pre-leptonema (EdU-positive cells that are weakly SYCP3-positive), as previously shown for MEI4 and IHO117,22. Because we can already detect ANKRD31 accumulation at sites of PARb-hybridization, we infer that the stronger sites of accumulation of MEI1 and REC114 also include PARs. Scale bars: 2 μm. PARb colocalized with ANKRD31 blobs (top panel) and MEI1 with REC114 (bottom panel) in all pre-leptotene spermatocytes analyzed (N>20) in one mouse. (f) REC114 is not detected in the mo-2 regions in spermatogonia. Seminiferous tubules were cultured with EdU, and chromosome spreads were stained for DMRT1 (a marker of spermatogonia46) and REC114 plus mo-2 FISH. REC114 blobs colocalized with mo-2 FISH signals in the preleptotene spermatocyte (bottom) but were not apparent in the DMRT1-positive spermatogonium (top). Both cells shown were captured in a single microscopic field. Scale bar: 2 μm. Mo-2 FISH signals do not colocalize with REC114 signal in all the spermatogonia analyzed (N>20) in one mouse. (g) Candidate ANKRD31 interacting proteins. To identify other PAR-associated proteins, ANKRD31 was immunoprecipitated from extracts made from whole testes of 12-dpp-old mice using two different polyclonal antibodies. This table shows a subset of proteins that were identified by mass spectrometry in immunoprecipitates from wild-type testes but not from Ankrd31−/−animals, and not from immunoprecipitates using an irrelevant antibody (anti-Cyclin B3). Full results are in Data File S3. LFQ, label-free quantification. REC114, MEI4, and MEI1 were recovered, confirming specificity. REC114 is known to interact directly with ANKRD3120 and MEI4 is a direct partner of REC11416,47. MEI1 colocalizes with ANKRD31 on chromatin (panel c). We also identified ZMYM3 and PTIP. ZMYM3 (zinc finger, myeloproliferative, and mental retardation-type 3) is a component of LSD1-containing transcription repressor complexes48 and has incompletely understood functions in DNA repair in somatic cells49. Mutation of Zmym3 results in adult male infertility from unknown causes50. However, the spermatocyte metaphase I arrest in this mutant50 may be consistent with presence of achiasmate chromosomes, possibly including X and Y. PTIP (Pax transactivation domain interacting protein; also known as PAXIP1) contains multiple BRCT (BRCA1 C-terminal) domains and regulates gene transcription, class switch recombination, and DNA damage responses in somatic cells51–53. Conditional knockout of Ptip causes spermatogenic arrest, but the function of PTIP during meiosis remains unclear54. Neither ZMYM3 nor PTIP was implicated previously in sex chromosome recombination. (h) Enrichment of ZMYM3 (top) and PTIP (bottom) on the PAR. Sex chromosomes of representative early pachytene spermatocytes are shown. Scale bars: 1 μm. ZMYM3 and PTIP were enriched in the PAR in all spermatocytes analyzed (N>20) in three mice. (i) Yeast two-hybrid assays testing interaction of full-length ANKRD31 fused to the Gal4 activating domain (AD) with either full-length PTIP or the C-terminal 191 amino acids of ZMYM3 fused to the Gal4 DNA binding domain (BD). (Full-length ZMYM3 autoactivates in this assay.) DDO (double dropout) medium selects for presence of both the AD and BD vectors (positive control for growth); QDO (quadruple dropout) and QXA (QDO plus X-α-gal and aureobasidin A) media select for a productive two-hybrid interaction at lower and higher stringency, respectively. Image is representative of two experiments using the same yeast strains.

Extended Data Fig. 2: PAR ultrastructure.

(a) Comparison of conventional microscopy and SIM, showing that the thickened PAR axis in conventional microscopy is resolved as separated axial cores (arrowheads). Scale bars: 2 μm. The thickening of the PAR axis in conventional microscopy and the splitting of the PAR axis in SIM was observed in more than 60 spermatocytes at late zygonema in at least three mice. (b) Ultrastructure of axis proteins SYCP2, SYCP3, and HORMAD2 in the PAR. Scale bars: 1 μm. SYCP2 (left) and HORMAD2 (right) staining mimic SYCP3 staining in late zygonema by conventional microscopy in all cells analyzed (N>30) in at least three mice, and by SIM (N=5, one mouse) (except that HORMAD2 appears rather depleted at the telomeres compared to SYCP3 and SYCP2). (c-d) Ruling out a crozier configuration. In principle, sister chromatid axes could be split apart or the PAR could adopt a crozier configuration in which a single conjoined axis for both sister chromatids is folded back on itself. A crozier (cartooned in c) was ruled out because the telomere binding protein TRF155 decorates the tip of the PAR bubble (d) and FISH signal for the PARb probe is arrayed relatively symmetrically on both axial cores (e), consistent with separated sister chromatid axes (a bubble configuration). Scale bars: 1 μm. We conclude that each axis is a sister chromatid, with a “bubble” from near the PAR boundary almost to the telomere. The presence of TRF1 at the distal tip of the PAR was observed in all spermatocytes analyzed, in one mouse (by conventional microscopy, N>20; by SIM, N=3). PARb FISH signals were relatively symmetrically arranged along the split PAR axes (by conventional microscopy, N>100 in at least three mice, or by SIM, N=9 in three mice). (f) Schematic of PAR ultrastructure and distribution of axis and RMMAI proteins at late zygonema. (g, h) Paired PARs with elongated and split axes occur in late zygonema to early pachynema. Shown are electron micrographs adapted with permission from ref.56 in comparison with SIM immunofluorescence images of spermatocytes at early pachynema (panel g) or late zygonema (panel h; cyan arrowheads indicate examples of incomplete autosomal synapsis). The spermatocytes in the electron micrographs were originally considered to be in mid-to-late pachynema56. However, in our SIM experiments, we can only detect this structure (paired X and Y with elongated and split axes, resembling a crocodile’s jaws) around the zygotene-to-pachytene transition, when RMMAI proteins are still highly abundant on the PAR axes, and when most or all autosomes are completely synapsed. Moreover, other published electron micrographs from mid-to-late pachytene spermatocytes show diagnostic ultrastructural features that are not present in the electron micrographs reproduced here, including a short PAR axis length, multi-stranded stretches of axis on non-PAR portions of the X and Y chromosomes with excrescence of axial elements, and a clear thickening of autosomal telomeres15,57. These observations allow us to conclude definitively that the elongation and splitting of PAR axes are a hallmark of cells from late zygonema into early pachynema. Scale bars in SIM images: 1 μm in panel g, 2 μm in panel h. Extended and split PAR axes were observed by SIM (N>30 spermatocytes) around the zygonema-pachynema transition in more than three mice. (i) REC114 enrichment and axis splitting occurs in the absence of SPO11, thus neither is provoked by DSB formation. Scale bar: 1 μm. PAR axis splitting and extension of the RMMAI signal were observed by SIM in Spo11−/− mice in more than 20 late zygotene-like spermatocytes in more than three mice. The differentiation of the PAR axis became hardly detectable at later stages in some pachytene-like spermatocytes as cells entered apoptosis.

Extended Data Fig. 3: Time course of the spatial organization of the PAR loop–axis ensemble.

(a) Time course of REC8 and ANKRD31 immunostaining along the PAR axis from pre-leptonema (preL, left) to mid pachynema (right). A montage of representative SIM images is shown. Chromosomes a–e are presumptive X or Y, but could be the distal end of chr9. Chromosomes at later stages were unambiguously identified by morphology. Chromosomes i–k show examples where the initial pairing (probably synaptic) contact between X and Y is (i) centromere-proximal (that is, closer to the PAR boundary), (k) distal (closer to the telomere), or (j) interstitial. Scale bar: 1 μm. The preferential enrichment of REC8 at the border of the PAR split axes was observed in more than 30 zygotene spermatocytes by SIM in more than three mice. (b) We collected three measurements of conventional immuno-FISH images from leptonema through mid-pachynema: length of the REC114 signal along the PAR axis; maximal distance from the PARb FISH signal to the distal end of the SYCP3-defined axis; and axis-orthogonal extension of FISH signal for the PARb probe (a proxy for loop sizes). Data were collected on three males. Insets show examples of each type of measurement at each stage. Horizontal black lines indicate means. Means of each measurement for each mouse at each stage are given below, along with the means across all three mice. Means are rounded to two significant figures; the grand means were calculated using unrounded values from individual mice. The number of cells of each stage from each mouse is given (N). Modest variability in the apparent dimensions of the Y chromosome PAR between different mice may be attributable to variation in copy number of mo-2 and other repeats because of unequal exchange during meiosis. Nonetheless, highly similar changes in spatial organization over time in prophase were observed in all mice examined, namely progressive elongation then shortening of axes and concomitant lengthening of loops. Scale bar: 1 μm.

Briefly, panels a and b show the following. At pre-leptonema, ANKRD31 blobs had a closely juxtaposed focus of the meiotic cohesin subunit REC8 (chromosome a). In leptonema and early zygonema, ANKRD31 and REC114 signals stretched along the presumptive PAR axes, with REC8 restricted to the borders (panel a, chromosomes b–e). The SYCP3-defined axis was already long as soon as it was detectable (0.73 μm) and the PARb FISH signal was compact (0.52 μm) (panel bi). At late zygonema, the PAR axis had lengthened still further (1.0 μm), while the PARb signal remained compact (panel bii). The PAR split into separate axes during this stage, each with abundant RMMAI (panel a, chromosomes f–h). The split was a REC8-poor zone bounded by REC8 foci (panel a, chromosomes f–h and Extended Data Fig. 2f). After synapsis, axes shortened and chromatin loops decompacted, with concomitant RMMAI dissociation. As cells transitioned into early pachynema and the X and Y PARs synapsed (panel a, chromosomes i–m), the PAR axes began to shorten slightly (0.85 μm) while the PARb signal expanded (0.85 μm) (panel biii). Meanwhile, the elongated ANKRD31 signals progressively decreased in intensity, collapsed along with the shortening axes, and separated from the axis while remaining nearby (panel a, chromosomes l–m). By mid-pachynema, PAR axes collapsed still further, to about half their zygotene length (0.50 μm) and the PARb chromatin expanded to more than twice the zygotene measurement (1.3 μm). ANKRD31 and REC114 enrichment largely disappeared, leaving behind a bright bolus of REC8 on the short remaining axis (panel a, chromosomes n–o and panel biv).

(c) Non-homologous synapsis appears sufficient to trigger collapse of the PAR loop-axis structure. We measured REC114 signal length along the PAR axis and extension of mo-2 chromatin orthogonal to the axis in Spo11−/− spermatocytes in which the X PAR had non-homologously synapsed with an autosome while the Y PAR remained unsynapsed. Within any given cell, the unsynapsed Y PAR maintained the characteristic late zygotene configuration (long axis, short loops) whereas the synapsed X PAR adopted the configuration characteristic of mid-pachynema (short axis, long loops). Error bars are mean ± SD. Scale bar: 2μm. We do not exclude that DSB formation without synapsis may also be sufficient (Supplementary Discussion).

Extended Data Fig. 4: RMMAI enrichment at mo-2 minisatellite arrays in the PAR and on specific autosomes.

(a) Top panel: Self alignment of the PARb FISH probe (reproduced from Fig. 2a). The circled block is a 20-kb mo-2 cluster. Bottom panel: Schematic depicting the last 1.4 Mb of the non-centromeric ends of the indicated chromosomes, showing the positions of mo-2 repeats (green) adjacent to assembly gaps (mm10); mo-2 repeats were identified by BLAST search using the mo-2 consensus sequence. Mo-2 repeats also appear at the distal end of chr4 in the Celera assembly (Mm_Celera, 2009/03/04). PARb and PARd BAC clones are indicated. (b) Confirmation that autosomal mo-2 FISH signals match the chromosomal locations indicated by mm10 or Celera genome assemblies. FISH was performed using an oligonucleotide probe containing the mo-2 consensus sequence in combination with BAC probes for adjacent segments of chromosomes 13, 9 and 4, as indicated. Magenta arrows point to concordant FISH signals. The chr9 BAC probe also hybridizes to the PAR. Scale bars: 2μm. The colocalization of mo-2 and the three autosomal FISH signals was observed in two mice (N>20 spermatocytes). (c) Comparison of mo-2 FISH with REC114 localization relative to the PAR boundary (PARb FISH probe) and the distal PAR (PARd probe). In mid zygonema, the mo-2 FISH signal colocalizes well with REC114 staining in between the PARb and PARd FISH signals. In late zygonema, mo-2 and REC114 are similar to one another and are elongated along the thickened SYCP3 staining of the PAR axis. From early to mid pachynema, REC114 progressively disappears, whereas the mo-2 FISH signal becomes largely extended away from the PAR axes. Note that the relative positions of the PARb and PARd probes reinforce the conclusion that the PAR does not adopt a crozier configuration. Scale bar: 1 μm. The different positioning of PARb and PARd FISH signals compared to mo-2 or REC114 signals was observed in more than 30 spermatocytes in at least three mice. (d) Illustration of the compact organization of the PAR chromatin (mo-2 FISH signal) compared to a whole-Y-chromosome paint probe. Scale bar: 2 μm. The costaining of mo-2 and full chrY probe was evaluated in one mouse (N>20 spermatocytes). (e) Lower mo-2 copy number in the M. m. molossinus subspecies correlates with lower REC114 staining in mo-2 regions. The left panels compare MSM and B6 mice for the colocalization between REC114 immunostaining and mo-2 FISH in leptotene spermatocytes. The REC114 and SYCP3 channels are shown at equivalent exposure for the two strains, whereas a longer exposure is shown for the mo-2 FISH signal in the MSM spermatocyte. Note that the mo-2-associated REC114 blobs are much brighter relative to the smaller dispersed REC114 foci in the B6 spermatocyte than in MSM. The right panel shows representative pachytene spermatocytes to confirm the locations of mo-2 clusters at autosome ends and the PAR in the MSM background. Scale bars: 2 μm. The lower intensity of REC114 blobs in MSM compared to B6 was observed in N>30 spermatocytes in three different pairs of mice. (f) PAR enrichment for ANKRD31 and RPA2 correlates with mo-2 copy number. Top panel: late zygotene spermatocytes from MSM x B6 F1 hybrid. Scale bar: 1 μm. Bottom panel: PAR-associated signals (A.U., arbitrary units) on B6-derived (YB) and MSM-derived chromosomes (XM) from the indicated number of spermatocytes (N). Red lines: means ± SD. Differences between X and Y PAR intensities are significant for both proteins and for mo-2 FISH in both F1 hybrids (p < 10−13, paired t-test; exact two-sided p values are in Data File S5). (g) Representative micrographs of late zygotene spermatocytes from reciprocal F1 hybrid males from crosses of B6 (high mo-2 copy number) and MSM (low mo-2 copy number) parents. Scale bar: 1 μm. (h) Frequency of paired X and Y at late zygonema and mid pachynema analyzed in three MSM and three B6 males. Differences between strains were not statistically significant at either stage (p = 0.241 for late zygonema and p = 0.136 for mid pachynema; two-sided Student’s t test). Note also that MSM X and Y are late-pairing chromosomes, as in the B6 background. The similar pairing kinetics indicates that the lower intensity of RMMAI staining on the MSM PAR is not attributable to earlier PAR pairing and synapsis in this strain. The number of spermatocytes analyzed is indicated (N).

Extended Data Fig. 5: Mo-2 regions accumulate heterochromatin factors.

(a) Costaining of ANKRD31 or mo-2 with the indicated proteins and histone marks known to localize at the pericentromeric heterochromatin (mouse major satellite), in zygotene spermatocytes (left) and pre-leptotene spermatocytes (right). Each of the heterochromatin factors shows locally enriched signal coincident with mo-2 regions (arrowheads), in addition to broader staining of other sub-nuclear regions. Scale bars: 2 μm. The CHD3/4 antibody recognizes both proteins58. The colocalization of ANKRD31 blobs with heterochromatin blobs was observed in all zygotene spermatocytes analyzed (N>20) in at least three mice for each antibody (left panel) and in one mouse for pre-leptotene spermatocytes (N>10) for each antibody (right panel). (b) CHD3/4, ATRX, HP1β, H4K20me3, H3K9me3 and macroH2A1.2 are not detectably enriched at mo-2 regions in spermatogonia (small, DMRT1-positive cells). These factors may be present at mo-2 regions in these cells, but do not appear to accumulate to elevated levels. Scale bars: 2 μm. The absence of colocalization between mo-2 FISH signals and heterochromatin factors was noted in all spermatogonia analyzed (N>30) from one mouse. (c) Heterochromatin factors can be detected in the PAR up to late pachynema. Each of the assayed proteins and histone marks showed staining on the autosomal and X-specific pericentromeric heterochromatin, the sex body, and euchromatin, albeit with variations between sites in the timing and level of accumulation. Importantly, however, they also showed enriched staining at all mo-2 regions up to early/mid-pachynema, as shown for H4K20me3 (top panel). By mid-to-late pachynema, as shown for H3K9me3 here, the signal persisted in the PAR but was usually barely detectable on chr9 or chr13 mo-2 regions. This observation indicates that, at least for the PAR, the heterochromatin factors can continue to be enriched on mo-2 chromatin after RMMAI proteins have dissociated. These results substantially extend previous observations about CHD3/4 colocalizing with PAR FISH signals; H4K20me3 being localized in the PAR and other chromosome ends; and H3K9me3, HP1β and macroH2A1.2 detection in the PAR in late pachynema58–61. Scale bars: 2 μm. The colocalization between Maj sat and H4K20me3 and H3K9me3 was observed in all spermatocytes analyzed (N>20) in one mouse. The colocalization between H4K20me3 and mo-2 FISH signals was observed in all spermatocytes analyzed (N>60), from preleptotene to mid pachytene in more than three mice. (d) Enrichment of the heterochromatin factors is independent of SPO11. Representative images of Y chromosomes from a Spo11−/− mouse are shown. Scale bar: 1 μm. The colocalization between PAR mo-2 FISH signals and heterochromatin factors was observed in all Spo11−/− spermatocytes analyzed (N>30) in more than three mice for CHD3/4 and at least one mouse each for ATRX, HP1β, HP1γ, macroH2A1.2, H3K9me3, and H4K20me3.

Extended Data Fig. 6: Genetic requirements for RMMAI assembly on chromosomes and for PAR loop–axis organization.

(a) Representative micrographs of ANKRD31, MEI4, IHO1 and MEI1 staining in wild type and the indicated mutants (quantification is in Fig. 3a). Scale bars: 2 μm. (b) Measurements of PAR loop–axis organization, as in Fig. 3b, on two additional males. Data from mouse 1 are reproduced from Fig. 3b to facilitate comparison. Means of each measurement for each mouse at each stage are given below, along with the means across all three mice. Means are rounded to two significant figures; the grand means were calculated using unrounded values from individual mice. The number of cells of each stage from each mouse is given (N). (c) REC8 is dispensable for splitting apart of PAR sister chromatid axes, but is required to maintain the connection between sisters at the distal tip of the chromosome. A representative SIM image is shown of a Y chromosome from a late zygotene Rec8−/− spermatocyte. The SYCP3-labeled axes adopt an open-fork configuration. Note that the distal FISH probe (PARd) shows that there are clearly disjoined sisters whereas the PAR boundary (PARb) shows only a single compact signal comparable to wild type. The disposition of the probes and SYCP3 further rules out the crozier configuration as an explanation for split PAR axes. Scale bar: 1 μm. The Y or X PAR structure was resolved by SIM as “fork-shaped” in all spermatocytes analyzed (N>20) from three mice. (d) Quantification of REC114 and MEI4 foci in two additional pairs of wild-type and Ankrd31−/− mice. Horizontal lines indicate means. Fewer foci were observed in the Ankrd31−/− mutant (two-sided Student’s t tests for each comparison of mutant to wild type: p = 5.6 × 10−6 (2nd set, REC114); p = 1.1 × 10−5 (2nd set, MEI4); p = 2.1 × 10−6 (3rd set, REC114); p = 0.017 (3rd, MEI4)). (e) Reduced REC114-staining intensity of axis-associated foci in Ankrd31−/− mutants. To rigorously control for slide-to-slide and within-slide variation in immunostaining, we mixed together wild-type and Ankrd31−/− testis cell suspensions before preparing chromosome spreads. A representative image is shown of a region from a single microscopic field containing two wild-type zygotene spermatocytes (left) and two Ankrd31−/− spermatocytes of equivalent stage (right). Note the diminished intensity of REC114 foci in the Ankrd31−/− spermatocytes. Scale bar: 2 μm. REC114 (non-blob) foci showed lower fluorescence intensity in Ankrd31−/− compared to wild type in all pairs of spermatocytes captured in the same imaging field (N=8 pairs), from one pair of mice. (f) PAR enrichment of heterochromatin-associated factors is independent of ANKRD31. Representative images of the Y chromosome at late zygonema/early pachynema showing colocalization between the decompacted mo-2 chromatin and the indicated proteins. Note that both the FISH and immunofluorescence signals are localized mostly off the axis. Compare with the same signals in absence of SPO11 (Extended Data Fig. 5d). Scale bar: 1 μm. Mo-2 FISH signal colocalized off the axis with the heterochromatin factors in Ankrd31−/− mice in all spermatocytes analyzed (N>30) in more than three mice for CHD3/4 and at least one mouse for ATRX, HP1β, HP1γ, macroH2A1.2, H3K9me3, and H4K20me3.

Extended Data Fig. 7: PAR-associated RPA2 foci.

(a) Loop-axis organization of the mo-2 region of chr9 in late zygonema. Compare with the PAR (Fig. 3b). Scale bars: 1 μm. Error bars: means ± SD. (b) Low mo-2 copy number correlates with less loop–axis reorganization (SIM images of late-zygotene F1-hybrid spermatocytes). Scale bars: 1 μm. The differentiation of the B6 PAR was observed in both hybrids B6 × MSM and MSM × B6 in 3 and 4 spermatocytes, respectively by SIM (1 mouse for each) and in more than 20 spermatocytes by conventional microscopy in two mice of each genotype. (c,d,e) Immuno-FISH for RPA2 and mo-2 was used to detect DSBs cytologically in wild type and the indicated mutants. To analyze Rec8 and Hormad1 mutations, we compared to mutants lacking SYCE1 (a synaptonemal complex central element component62) because Syce1−/− mutants show similar meiotic progression defects without defective RMMAI recruitment. Panel c shows representative images. Scale bars: 2 μm, inset 1 μm. Panel d shows the global counts of RPA2 foci for zygotene (zyg) or zygotene-like cells and for pachytene (pach) or pachytene-like cells. Panel e shows, for each cell, the fraction of mo-2 regions that had a colocalized RPA2 focus. Red lines: means ± SD. Statistical significance is indicated in panels c and d for comparisons (two-sided Student’s t tests) of wild type to Ankrd31−/− or of Syce1−/− to either Rec8−/− or Hormad1−/− for matched stages. Exact p values are in Data File S7. Note that the number of discretely scorable mo-2 regions in panel e varied from cell to cell depending on pairing status. (f) Frequent DSB formation at mo-2 regions in the PARs and on autosomes does not require HORMAD1. Micrograph at left shows two adjacent spermatocytes (boundary indicated by dashed line). Scale bar: 2 μm. Insets at right show higher magnification views of the numbered mo-2 regions, all of which are associated with RPA2 immunostaining of varying intensity. This picture illustrates the preferential RPA2 focus formation in mo-2 regions in a Hormad1−/− mouse; quantification is in panel e. (g) Autosomal mo-2 regions often form DSBs late. Immuno-FISH for RPA2, mo-2, and PARb was used to detect DSBs cytologically in wild type from leptonema to mid-pachynema, and to distinguish the X or Y PAR from chromosomes 9 and 13. Chr4 was not assayed because the mo-2 FISH signal was often barely detectable. The top panel shows the global number of RPA2 foci per cell. Black lines are means ± SD. The bottom panel shows the percentage of spermatocytes with an RPA2 focus overlapping the PAR (X, Y, or both) or overlapping chr9 or chr13. A representative image of an early pachytene spermatocyte is shown. Note that, as previously shown for the PAR2, autosomal mo-2 regions continue to accumulate RPA2 foci beyond the time when global RPA2 foci have largely or completely ceased accumulating. Scale bar: 2 μm. (h) X–Y pairing status, quantified by immuno-FISH for SYCP3 and the PARd probe. (i) Montage of SIM images from a B6 male showing that multiple, distinct RPA2 foci can be detected from late zygonema to mid pachynema, suggesting that multiple PAR DSBs can be formed during one meiosis (see also ref. 2 for further discussion). Scale bar: 1μm. The presence of multiple RPA2 foci in the PAR was observed by SIM in more than 20 spermatocytes from late zygonema to mid pachynema in one mouse. (j) Percentage of spermatocytes at the zygotene-pachytene transition with no (0), 1, 2 or 3 distinguishable RPA2 foci on the unsynapsed Y chromosome PAR of MSM and B6 mice. The difference between the strains is statistically significant (negative binomial regression, p = 7.2 × 10−5). N indicates the number of spermatocytes analyzed. A representative picture is shown for each genotype, with one RPA2 focus on the MSM PAR and two apparent sites of RPA2 accumulation on the B6 PAR. The detection of multiple foci is consistent with reported double crossovers6. Scale bar: 1 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 8: DSB maps on the PAR and autosomal mo-2 regions.

(a) SSDS sequence coverage (data from refs. 7,20) is shown for the X PAR (shown previously in different form in ref. 20), the Y PAR, and the mo-2-adjacent regions of chr9 and chr13. The dashed segments indicate gaps in the mm10 genome assembly. We did not assess chr4 because available assemblies are too incomplete. (b) Regions adjacent to the mo-2 region on chr9 show SSDS signal that is reproducibly elevated relative to chr9 average in wild-type testis samples but not in maps from Ankrd31−/− testes or wild-type ovaries. Two of the SSDS browser tracks are reproduced from panel a. The bar graph shows enrichment values from individual SSDS maps (T1–T9 are maps from wild-type testes; O1 and O2 are from wild-type ovaries31). Enrichment values are defined as coverage across the indicated coordinates relative to mean coverage for chr9 (see Methods for details). Note that ovary sample O1 and the Ankrd31−/− adult sample are known to have poorer signal:noise ratios than the other samples20,31. For all SSDS coverage tracks, reads mapping to multiple locations are included after random assignment to one of their mapped positions. However, the same conclusions are reached about ANKRD31-dependence and PRDM9-independence of signal on chr9 and chr13 if only uniquely mapped reads are used. (c) Oocytes incur substantially less DSB formation than spermatocytes near the mo-2 region on chr9. SSDS signal is from ref. 31 (samples T1 and O2). The X-PAR is shown for comparison (previously shown to be essentially devoid of DSBs in ovary samples31). See panel b for quantification.

Extended Data Fig. 9: RMMAI accumulation and low-level DSB formation on mo-2 regions in oocytes.