Abstract

Objective:

The extracellular matrix of atherosclerotic arteries contains abundant deposits of cellular fibronectin containing extra domain A (Fn-EDA), suggesting a functional role in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. Fn-EDA is synthesized by several cell types, including endothelial cells (ECs), and smooth muscle cells (SMCs), which are known to contribute to different stages of atherosclerosis. Although previous studies using global Fn-EDA-deficient mice have demonstrated that Fn-EDA is pro-atherogenic, the cell-specific role of EC versus SMC-derived-Fn-EDA in atherosclerosis has not been investigated yet.

Approach and Results:

To determine the relative contribution of different pools of Fn-EDA in atherosclerosis, we generated mutant strains lacking Fn-EDA in the endothelial cells (Fn-EDAEC-KO) or smooth muscle cells (Fn-EDASMC-KO) on apolipoprotein E-deficient (Apoe−/−) background. The extent of atherosclerotic lesion progression was evaluated in whole aortae and cross-sections of the aortic sinus in male and female mice fed a high-fat “Western” diet for either 4 weeks (early atherosclerosis) or 14 weeks (late atherosclerosis). Irrespective of sex, Fn-EDAEC-KO, but not Fn-EDASMC-KO mice, exhibited significantly reduced early atherogenesis concomitant with decrease in inflammatory cells (neutrophil and macrophage) and VCAM-1 expression levels within the plaques. In late atherosclerosis model, irrespective of sex, Fn-EDASMC-KO mice exhibited significantly reduced atherogenesis, but not Fn-EDAEC-KO mice, that was concomitant with decreased macrophage content within plaques. Lesional SMCs, collagen content, and plasma inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β), total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels were comparable among groups.

Conclusion:

Endothelial cell-derived Fn-EDA contributes to early atherosclerosis, whereas smooth muscle cell-derived Fn-EDA contributes to late atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Fn-EDA, atherosclerosis, smooth muscle cell, endothelial cell

Graphical abstract

Introduction:

Atherosclerotic lesion progression is a chronic inflammatory process characterized by fatty streaks, leukocytes, smooth muscle cells (SMCs), calcification, and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling. During chronic inflammation, ECM proteins or their fragments can modulate the migration of several cell types, including endothelial cells (ECs), SMCs, and monocyte/macrophages, all known to contribute to different stages of atherosclerosis.1 In human and murine models, unlike healthy arteries, the ECM of atherosclerotic arteries contains abundant deposits of Fn, suggesting a functional role for Fn in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis.2, 3 Fn is alternatively spliced that results in variable inclusion of Extra Domain A (EDA), Extra Domain B (EDB), and the Type III Homologies Connecting Segment (IIICS). The amino acid sequence and splicing patterns of the EDA and EDB are highly conserved (> 90%) in the vertebrates, with either total inclusion or exclusion, including human, mouse, rat, chicken, and zebrafish.4 Although the predominant form of Fn in plasma of healthy humans contains negligible amounts of EDA or EDB, inclusion of these alternatively spliced domains has been observed in animal models of vascular injuries,5, 6 and patients at risk for diabetes,7 and atherosclerosis.8, 9

Several studies have demonstrated that global deletion of Fn-EDA in apolipoprotein E-deficient (Apoe−/−) or low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R)-deficient mice reduces atherosclerosis suggesting that Fn-EDA is proatherogenic.10–12 Fn-EDB accumulation has also been found in human atherosclerotic plaques;13 however, whether it is pro-atherogenic remains unclear. The Fn present in the atherosclerotic lesions could arise from several sources, including the leak of plasma Fn (pFn) from the circulation, Fn-derived from ECs, and Fn-derived from SMCs. Studies utilizing human aortic endothelial cells showed that EC-derived Fn regulates integrin α5β1-mediated adhesion formation, Fn fibrillogenesis, and inflammation in response to oxidized LDL, suggesting EC-derived Fn may contribute to early atherogenesis.14 Other studies showed that Fn-EDA is expressed in the vicinity of SMCs and was a characteristic feature of synthetic SMCs that are known to contribute to different stages of atherosclerosis.6, 15 Despite these observations, there are no studies that provide conclusive evidence on the role of EC-derived versus SMC-derived Fn-EDA in atherogenesis. Also unclear is whether Fn-EDA derived from these cell types contributes to the early or late atherogenesis. Herein, utilizing mutant mice, we provide evidence that EC-derived Fn-EDA contributes to early atherosclerosis, whereas SMC-derived Fn-EDA contributes to advanced atherosclerosis.

Materials and Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. For details of reagents and murine strains, please see the Major Resources Table in the Data Supplement

Mice

Six weeks old male and female Fn-EDAfl/flApoe−/− mice on the C57BL/6J background were used in the present study.11 Fn-EDAfl/flApoe−/− mice were crossed with the Apoe−/−Tie2Cre+ mice to generate Fn-EDAfl/flTie2Cre+Apoe−/− (Fn-EDAEC-KO, endothelial cell KO of Fn-EDA) as described.16 SM22αCre+ mice (004746, Tg [Tagln-cre]1 Her/J; The Jackson Laboratory) were crossed with Apoe−/− mice to generate SM22αCre+Apoe−/− mice. Fn-EDAfl/flApoe−/− mice were crossed to SM22αCre+Apoe−/− mice to generate Fn-EDAfl/flSM22αCre+Apoe−/− mice (Fn-EDASMC-KO, smooth muscle KO of Fn-EDA) as described.15 Mice were genotyped by PCR according to protocols from The Jackson Laboratory and as described before.15–17 The University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee approved all protocols.

Mice diet feeding and preparation of tissues

Both male and female mice (Fn-EDAfl/flTie2Cre+Apoe−/−, Fn-EDAfl/fl Apoe−/−, EDAfl/flSM22αCre+Apoe−/−) were fed a high-fat “Western” diet (20% milk fat and 0.2% cholesterol, Harlan Teklad) beginning at 6 weeks of age until they were sacrificed at 5 months of age (i.e., 14 weeks on high-fat Western diet to induce late atherosclerosis). Mice were fed a normal laboratory diet (NIH-31 modified mouse diet: 7913) before high-fat Western diet. All mice were fed 4 weeks of high-fat Western diet beginning at 6 weeks of age to study early atherosclerosis. For plasma isolation, blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes by retro-orbital plexus puncture after overnight fasting. Before tissue isolation, mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/Kg ketamine/10 mg/Kg xylazine and perfused via the left ventricle with 10 ml PBS, followed by 10 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde under physiological pressure. After perfusion, aortae were isolated, dehydrated for 5 min in 60% isopropylalcohol and stained with Oil Red O. Hearts containing aortic roots were dissected and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde prior to embedding in paraffin.

Extent and composition of atherosclerotic lesions

The whole aortae were isolated and stained with Oil Red O, and the en face lesion area was measured by morphometry using NIH ImageJ software to measure atherosclerosis lesion progression. Lesion areas in the aortic sinus were quantified by using 5 μm thick serial cross-sections that were cut through the aorta beginning at the origin of the aortic valve leaflets and stained by VerHoeffs/Van Gieson method. The cross-sectional lesion area from each mouse was calculated by taking the mean value of 4 sections (each 80 μm apart, beginning at the aortic valve leaflets and spanning 320 μm) as described previously.18 For quantification, NIH ImageJ software was used.

Bone marrow transplantation (BMT)

BMT of either Fn-EDAfl/flTie2Cre+ Apoe−/− or Fn-EDAfl/flApoe−/− mice were performed on 6 weeks old mice. Mice were irradiated with 2-doses of 6.5-Gy at an interval of 4 hours between the first and second irradiations before BMT as described.18 Under sterile conditions, bone marrow cells (1 × 107) were extracted from excised femurs and tibias of euthanized mice, suspended in sterile PBS and injected into the retro-orbital venous plexus of lethally irradiated recipient mice. Post-transplantation, mice were maintained in sterile cages and fed autoclaved food and water ad libitum. Following BMT experiments were performed: 1) irradiated Fn-EDAfl/flApoe−/− mice reconstituted with BM from Fn-EDAfl/fl Apoe−/−, 2) irradiated Fn-EDAfl/flApoe−/−mice reconstituted with BM from Fn-EDAfl/flTie2Cre+Apoe−/−, 3) irradiated Fn-EDAfl/flTie2Cre+Apoe−/−mice reconstituted with BM from Fn-EDAfl/fl Apoe−/−donors. Successful BMT was confirmed after 4 weeks by PCR to check the presence of the genomic DNA of the respective donor mice in peripheral blood cells. Total blood cell counts were obtained using an automated veterinary hematology analyzer (ADVIA) to ascertain that BMT did not affect the number of BM-derived blood cells.

Immunohistochemistry of murine samples

Tissue preparation and histochemical staining were performed as described.18 Briefly, antigen retrieval was performed before immunohistochemical staining. Slides were rehydrated, and sections were blocked with 5% serum in Tris-buffered saline at room temperature (RT) from the species in which the secondary antibody was raised. For chromogenic detection, endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 0.1% hydrogen peroxide (Fisher Scientific, #H325) in methanol for 15 minutes. Sections were stained for Lys6G.2 (clone, 1A8, Biorad # MCA6077GA) Mac3 (1.5 μg/ml BD Pharmingen #550292) and smooth muscle cell actin (αSMA, Sigma, #A5228), fibronectin EDA (Clone Fn-3E2, Sigma, #F6140), CD31 (ab28364), VCAM-1 (#SC-13160). After overnight incubation at 4°C, slides were washed thrice with PBS for 5 minutes and incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody for 1 hour at RT. For immunofluorescence, goat anti-rat 546 (4 μg/ml, Invitrogen, #A11081), goat anti-rat 488 (4 μg/ml, Invitrogen, # A-11006), goat anti-rabbit IgG 546 (4 μg/ml, Invitrogen # A11035), goat anti-mouse 488 (Catalog # A32723) were used. Nuclei were stained using the Antifade mounting medium with DAPI (Vector laboratories # H:1200). For the chromogenic method, slides were incubated with streptavidin-HRP for 40 minutes RT and washed thrice with PBS for 5 minutes and incubated with DAB substrate (Vector laboratories #SK400) for less than 2 minutes until color develops. Hematoxylin counterstained slides were dehydrated, mounted using permount, and examined using an Olympus fluorescent microscope (BX51). Mean fluorescence intensity was quantified using the ImageJ software as previously described (Jensen, 2013). Protein colocalization was analyzed using Pearson’s colocalization coefficients (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/plugins/track/jacop.html). Colocalization was considered positive for values ranging from 0.5–1. Measurements were obtained from two different fields per murine section, 4–6 different fields for human samples. For negative control, incubation without primary antibodies and with isotype-matched immunoglobulins was used. A mean for each mouse was calculated using the mean value of 4 sections (each 80 μm apart, beginning at the aortic valve leaflets and spanning 320 μm).

Determination of plasma total cholesterol and lipid levels

Overnight fasted blood from each mouse was collected in heparinized tubes by retro-orbital venous plexus puncture. Plasma was separated and analyzed for total cholesterol and triglyceride (both from DiaSys #113009911923, #157109911923) levels by using enzymatic colorimetric assays according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Picrosirius red staining for collagen

Quantification of interstitial collagen content of the aortic sinus was performed as described11. Briefly, serial cross-sections of 5 μm were stained with Weigert’s hematoxylin and washed in running tap water for 10 minutes followed by incubation for 4 hours in a freshly prepared 0.1% solution of Sirius Red F3B (Sigma-Aldrich, #365548) in saturated aqueous picric acid (Sigma-Aldrich, #P-6744). Sections were rinsed twice in acidified (0.01 N HCl) distilled water, dehydrated, and mounted in Permount (Fisher Scientific, #SP15–500). Polarization microscopy was used to analyze picrosirius red staining. Total collagen, thick mature orange-red fibers, and thin immature green fibers were quantified as described19 using NIH ImageJ software with a defined threshold (minimum 100 and maximum 200). A mean for each mouse was calculated using the mean value of 4 sections (each 80 μm apart, beginning at the aortic valve leaflets and spanning 320 μm).

ELISA assay for TNF-α and IL-1β

Overnight fasted plasma samples were used for determination of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) with commercially available mouse ELISA kits (TNF-α, # MTA00B; IL-1β,#MLB00C; R&D Systems) according to the kit manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Results are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). For statistical analysis, the Prism Graph software package was used. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check normality, and Bartlett’s test was used to check equal variance. The statistical significance of the difference between means was assessed using the unpaired Student t-test (for normally distributed data) or Mann Whitney test (for not normally distributed data) and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukeys’s multiple comparisons test. P< 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

EC-derived Fn-EDA contributes to early atherosclerosis but not late atherosclerosis

We generated Fn-EDAfl/flTie2Cre+Apoe−/− mice to determine the role of EC-derived Fn-EDA in atherosclerosis. Because Tie2 is also expressed by hematopoietic cells in addition to endothelial cells, Fn-EDAfl/flTie2Cre+Apoe−/− mice were transplanted with bone marrow from Fn-EDAfl/flApoe−/− mice, which constitutively express Fn-EDA in all cells and tissues. This strategy resulted in mutant mice that are deficient for Fn-EDA in endothelial cells (Fn-EDAEC-KO). Controls were irradiated littermates Fn-EDAfl/flApoe−/− mice that received bone marrow from Fn-EDAfl/flApoe−/− mice or Fn-EDAfl/flTie2Cre+Apoe−/− mice. Male and female mice were examined separately to determine sex-based differences. Mice were fed a normal laboratory diet for 10 weeks until the complete reconstitution of newly transplanted bone marrow, and then a high-fat “Western” diet for 4 or 14 weeks. Genomic PCR confirmed the presence of the Tie2Cre gene in Fn-EDAfl/flTie2Cre+Apoe−/− mice (Figure IA in the Data Supplement). RT-PCR confirmed the absence of Fn-EDA mRNA in the ECs but not in other cells of Fn-EDAfl/flTie2Cre+Apoe−/− mutant mice (Figure IB in the Data Supplement).

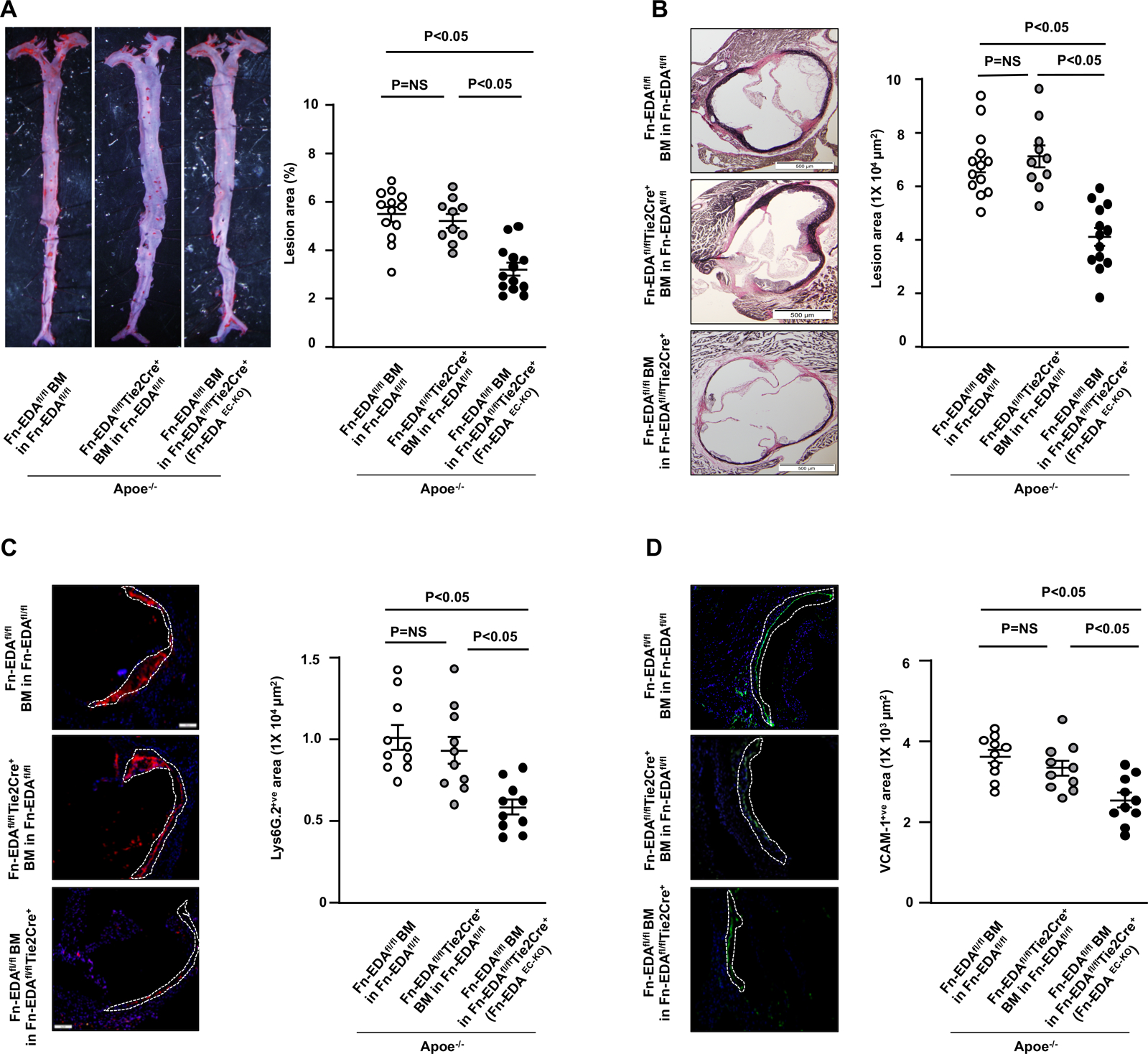

Next, we compared the extent of atherosclerosis in whole aortae (by staining with Oil Red O and quantifying en face lesion area) and aortic sinus (by staining with VerHoeffs/Van Gieson and quantifying the cross-sectional area). In the early atherosclerosis model, irrespective of sex, Fn-EDAEC-KO mice exhibited reduced atherosclerosis lesion progression in aortae and aortic sinus when compared with controls (P<0.05, Figure 1AB and Figure IIAB in the Data Supplement). The decrease in lesion size in the Fn-EDAEC-KO mice was associated with reduced neutrophil (Figure 1C) and macrophage content (Figure III in the Data Supplement) and decreased VCAM-1 expression (Figure 1D) within lesions suggesting reduced endothelial activation. Representative negative controls are shown (Figure IV in the Data Supplement). In late atherosclerosis model, lesion area in the aortae and aortic sinus (Figure 2AB), macrophage content (Figure 2C), total collagen content including both thick mature and thin immature fibers (Figure V in the Data Supplement), and α-SMA (Figure 2D) within aortic lesions were comparable between Fn-EDAEC-KO and control mice. Inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β in plasma (Figure VI in the Data Supplement), total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels (Table I in the Data Supplement) were comparable among groups. Together, these results suggest that EC-derived Fn-EDA contributes to early atherosclerosis, but not advanced atherosclerosis, most likely by promoting neutrophil and macrophage recruitment via VCAM-1.

Figure 1. Fn-EDAEC-KO mice exhibit reduced early atherosclerosis.

All the mice were females and fed a high-fat Western diet for 4 weeks. A, Representative photomicrographs and quantification of Oil red O -stained en face lesion area in the whole aortae. B, Representative photomicrographs of VerHoeffs/Van Geison-staining and quantification of cross-sectional lesion area in aortic sinuses. C, Representative photomicrographs and quantification of neutrophil-stained (Lys6G.2-positive cells) in aortic sinuses. Scale bar = 100 μm D, Representative photomicrographs and quantification of vascular cell adhesion molecule-stained (VCAM1-positive cells) area in aortic sinuses. Scale bar = 100 μm. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Each dot represents a single mouse (n=10–13/group). Statistical analysis: One way ANOVA followed by Tukeys’s multiple comparisons test.

Figure 2. Endothelial-derived Fn-EDA does not contribute to late atherosclerosis.

All the mice were females and fed a high-fat Western diet for 14 weeks. A, Representative photomicrographs and quantification of Oil red O -stained en face lesion area in the whole aortae. B, Representative photomicrographs of VerHoeffs/Van Geison-staining and quantification of cross-sectional lesion area in aortic sinuses. Scale bar = 500 μm C, Representative photomicrographs and quantification of macrophage (mac3-positive cells) in aortic sinuses. Scale bar = 500 μm D, Representative photomicrographs and quantification of smooth muscle cell-stained (⍺-SMA-positive) area in aortic sinuses. Scale bar = 100 μm Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Each dot represents a single mouse (n=10–13/group). Statistical analysis: One way ANOVA followed by Tukeys’s multiple comparisons test.

SMC-derived Fn-EDA contributes to late atherosclerosis but not early atherosclerosis

We generated Fn-EDAfl/flSM22αCre+Apoe−/− to determine the role of SMC-derived Fn-EDA in atherosclerosis. Genomic PCR confirmed the presence of the SM22αCre gene in Fn-EDAfl/flSM22αCre+Apoe−/− (Figure VIIA in the Data Supplement). RT-PCR confirmed the absence of Fn-EDA mRNA in SMCs but not in other cells of Fn-EDAfl/flSM22αCre+Apoe−/− mutant mice (Figure VIIB in the Data Supplement). Male and female mice were first fed a normal laboratory diet for 6 weeks, and then a high-fat “Western” diet for 4 or 14 weeks. In the early atherosclerosis model, irrespective of sex, we observed that atherosclerosis lesion progression in the aorta and aortic sinus was comparable between Fn-EDASMC-KO and controls (Figure 3AB and Figure VIIIAB in the Data Supplement). Lesion neutrophil (Figure 3C), macrophage influx (Figure IX in the Data Supplement), and VCAM-1 expression (Figure 3D) were comparable among groups. In late atherosclerosis model, irrespective of sex, we found that the mean lesion areas in the aortae and aortic sinus were significantly smaller in Fn-EDASMC-KO mice when compared with controls (P<0.05, Figure 4AB and Figure VIIICD in the Data Supplement). The decrease in lesion size in the Fn-EDASMC-KO mice was associated with reduced macrophage infiltration (Figure 4C) with unaltered collagen (Figure X in the Data Supplement and α-SMA content (Figure 4D). Inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, total cholesterol, and triglycerides levels in the plasma and leukocyte counts were comparable among groups (Figure XI and Table II & III in the Data Supplement).

Figure 3. Smooth muscle cell-derived Fn-EDA does not contribute to early atherosclerosis.

All the mice were females and fed a high-fat Western diet for 4 weeks. A, Representative photomicrographs and quantification of Oil red O-stained en face lesion area in the whole aortae. B, Representative photomicrographs of VerHoeffs/Van Geison-staining and quantification of cross-sectional lesion area in aortic sinuses. Scale bar = 500 μm. Lower panels. C, Representative photomicrographs and quantification of neutrophil-stained (Lys6G.2-positive cells) in aortic sinuses. Scale bar = 100 μm. D, Representative photomicrographs and quantification of vascular cell adhesion molecule-stained (VCAM1-positive cells) in aortic sinuses. Scale bar = 100 μm. Each dot represents a single mouse (n=8–14/group). Statistical analysis: unpaired student t-test.

Figure 4. Fn-EDASMC-KO mice exhibit reduced late atherosclerosis.

All the mice were females and fed a high-fat Western diet for 14 weeks. A, Representative photomicrographs and quantification of Oil red O-stained en face lesion area in the whole aortae. B, Representative photomicrographs of VerHoeffs/Van Geison-staining and quantification of cross-sectional lesion area in aortic sinuses. Scale bar = 500 μm. C, Representative photomicrographs and quantification of macrophage (mac3-positive cells) area in aortic sinuses. Scale bar = 500 μm. D, Representative photomicrographs and quantification of smooth muscle cell-stained (⍺-SMA-positive) area in aortic sinuses. Scale bar = 100 μm. Each dot represents a single mouse (n=8–14/group). Statistical analysis: unpaired student t-test.

Next, utilizing immunostaining, we determined the percentage of Fn-EDA associated with SMCs (α-SMA-positive) and ECs (CD31-positive) in autopsy samples from patients with coronary artery disease. We found a marked expression of Fn-EDA within advanced lesions from diseased coronary arteries, whereas staining was virtually absent in arteries from healthy controls (Figure XII in the Data Supplement). Double-label immunostaining revealed a three-fold increase in Fn-EDA staining associated with SMCs (Fn-EDA/α-SMA-positive) when compared with ECs (Fn-EDA/CD31-positive; Figure XII in the Data Supplement). Together, these results suggest that SMC-derived Fn-EDA contributes to advanced atherosclerosis, but not early atherosclerosis.

Discussion

Understanding the mechanisms that contribute to the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis is vital in developing novel strategies to limit the lesion progression before reaching the clinical manifestations. Abundant deposits of Fn-EDA have been found in the ECM of both human and murine atherosclerotic plaques. Despite previous evidence suggesting that Fn-EDA is proatherogenic, the role of EC-derived versus SMC-derived Fn-EDA in atherogenesis remains unclear. Utilizing Fn-EDAEC-KO and Fn-EDASMC-KO mice, we provide evidence that EC-derived Fn-EDA contributes to early atherosclerosis, whereas SMC-derived Fn-EDA contributes to late atherosclerosis, suggesting cell and stage-specific role of Fn-EDA during atherosclerosis.

Previous studies have shown that Fn-EDA was associated with endothelial cells during early lesion progression but absent from adjacent uninvolved endothelium.12 A minimal Fn-EDA staining was also found around macrophages or early foam cells during early lesion progression.12 Another study found that cFn deposition by α5β1 integrin promotes early atherosclerosis.14 Although these studies suggest that EC-derived Fn-EDA may contribute to early atherosclerosis,12 there was no definitive evidence that has examined how the lack of Fn-EDA from different specific cell type affects early atherogenesis. Utilizing Fn-EDAEC-KO and Fn-EDASMC-KO mice, we found that Fn-EDA derived from endothelial cells, but not from SMCs, contributes to early atherosclerosis, independent of changes in plasma total cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Despite the fact that the atherogenic process initiates with the deposition of LDL, several studies suggest that chronic inflammation contributes to atherosclerotic lesion progression, and lesion size does not always correlate with an increase in plasma cholesterol and LDL levels.20–22 It is known that ECM within the lesions can trap and retain lipids.23 There could be several possibilities by which EC-derived Fn-EDA may contribute to early atherosclerosis. First, by promoting early atherogenic inflammation via integrin α5β1 as suggested previously.14 Second, by enhancing oxidized LDL-mediated NF-κB p65 activation and VCAM-1 expression.14, 24 In agreement with these studies, we observed significantly decreased VCAM-1 expression in Fn-EDAEC-KO mice. Third, by potentiating neutrophil interactions with the vessel wall. We found that reduced lesion size in Fn-EDAEC-KOmice was associated with decreased neutrophil and macrophage content within lesions. The EDA of Fn contains additional binding sites for integrin α9β1 and α4β1. Integrin α9β1 is highly expressed on activated neutrophils and known to contribute to adhesion, and transmigration.25 Neutrophil depletion has been shown to improve early atherosclerosis in mice.26 Studies suggest that neutrophils contribute to early atherosclerosis via multiple mechanisms including neutrophil extracellular trap formation and interacting with monocytes to prime them for inflammatory response.27, 28 Fourth, by promoting NF-κB p65-mediated inflammation in both neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages via innate immune receptor toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). Fn-EDA is an endogenous ligand for TLR4. Previously, we have shown that cFn potentiates NFκB p65-mediated inflammation in bone-marrow-derived neutrophils and macrophages via TLR4.11 In line with our observations, a recent study found that EC-derived Fn-EDA was increased by disturbed flow and interacted with TLR4 to promote inflammation.29

Herein, we found that in human diseased coronary lesions, a majority of Fn-EDA staining was colocalized with SMCs, whereas Fn-EDA staining colocalized with ECs was less when compared to SMCs. Our results are in agreement with the previous study, where less Fn-EDA staining was associated with endothelial cells in the advanced lesions.12 Consistent with these studies, we provide evidence that SMC-derived Fn-EDA, but not EC-derived Fn-EDA, contributes to late atherosclerosis by recruitment of monocytes/macrophages without altering SMCs and collagen content. It is possible that the leak of circulating Fn-EDA into the vessel wall over time may mask the effectiveness of Fn-EDA deletion in Fn-EDAEC-KO mice on late atherogenesis. Such a possibility is minimal because lack of Fn-EDA, specifically, in the plasma does not affect atherogenesis, suggesting that the Fn-EDA produced by cells present in atherosclerotic plaque contributes to atherogenesis.10 There could be several possibilities by which SMC-derived Fn-EDA may contribute to late atherosclerosis. First, by modulating SMCs from contractile to synthetic phenotype via integrins.6, 15 SMC-derived Fn-EDA contributes to synthetic phenotype via Akt1/mTOR signaling.15 In addition to ECM components, synthetic SMC produces many cytokines such as PDGF, transforming growth factor-β, IFNγ, and MCP-1 that may promote monocyte/macrophage recruitment.30 Second, by potentiating TLR4 signaling in monocytes/macrophages. In addition to integrins including α5β1, α3β1, αvβ1, αvβ3, Fn-EDA is an endogenous ligand for TLR4. Previously, using double-deficient mice, we have shown that TLR4 partially contributes to Fn-EDA-mediated advanced atherosclerosis, most likely by potentiating NFκB p65-mediated inflammation.11

In conclusion, our results provide novel insights into the role of different pools of Fn-EDA at different stages of atherogenesis. This study further supports the notion that therapeutically targeting Fn-EDA may have the potential for the prevention and treatment of atherosclerosis in patients at high risk for coronary heart disease.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The extracellular matrix of atherosclerotic arteries contains abundant deposits of Fn-EDA, suggesting a functional role in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis.

Endothelial cell-derived Fn-EDA, but not smooth muscle cell-derived Fn-EDA, contributes to early atherosclerosis in mice.

Smooth muscle cell-derived Fn-EDA, but not endothelial cell-derived Fn-EDA, is the primary determinant that contributes to late atherosclerosis.

Sources of funding

The AKC lab is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health grants (R35HL139926, R01NS109910 & U01NS113388) and by Established Investigator Award 18EIA33900009 from American Heart Association. PD is supported by a postdoctoral grant from American Heart Association (18POST33960179), and ND is supported by the American Society of Hematology Scholar award.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Fn-EDA

Fibronectin containing extra domain A

- EC-Fn-EDA

Endothelial cell-derived Fn-EDA

- SMC-Fn-EDA

Smooth muscle dell-derived Fn-EDA

- BMT

Bone marrow transplantation

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

Reference:

- 1.Raines EW. The extracellular matrix can regulate vascular cell migration, proliferation, and survival: Relationships to vascular disease. Int J Exp Pathol. 2000;81:173–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shekhonin BV, Domogatsky SP, Idelson GL, Koteliansky VE, Rukosuev VS. Relative distribution of fibronectin and type i, iii, iv, v collagens in normal and atherosclerotic intima of human arteries. Atherosclerosis. 1987;67:9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pedretti M, Rancic Z, Soltermann A, Herzog BA, Schliemann C, Lachat M, Neri D, Kaufmann PA. Comparative immunohistochemical staining of atherosclerotic plaques using f16, f8 and l19: Three clinical-grade fully human antibodies. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208:382–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hynes RO. The evolution of metazoan extracellular matrix. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;196:671–679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubin D, Peters JH, Brown LF, Logan B, Kent KC, Berse B, Berven S, Cercek B, Sharifi BG, Pratt RE, et al. Balloon catheterization induced arterial expression of embryonic fibronectins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:1958–1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glukhova MA, Frid MG, Shekhonin BV, Vasilevskaya TD, Grunwald J, Saginati M, Koteliansky VE. Expression of extra domain a fibronectin sequence in vascular smooth muscle cells is phenotype dependent. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:357–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanters SD, Banga JD, Algra A, Frijns RC, Beutler JJ, Fijnheer R. Plasma levels of cellular fibronectin in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:323–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemanska-Perek A, Krzyzanowska-Golab D, Pupek M, Klimeczek P, Witkiewicz W, Katnik-Prastowska I. Analysis of soluble molecular fibronectin-fibrin complexes and eda-fibronectin concentration in plasma of patients with atherosclerosis. Inflammation. 2016;39:1059–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiechter M, Frey K, Fugmann T, Kaufmann PA, Neri D. Comparative in vivo analysis of the atherosclerotic plaque targeting properties of eight human monoclonal antibodies. Atherosclerosis. 2011;214:325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pulakazhi Venu VK, Uboldi P, Dhyani A, Patrini A, Baetta R, Ferri N, Corsini A, Muro AF, Catapano AL, Norata GD. Fibronectin extra domain a stabilises atherosclerotic plaques in apolipoprotein e and in ldl-receptor-deficient mice. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114:186–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doddapattar P, Gandhi C, Prakash P, Dhanesha N, Grumbach IM, Dailey ME, Lentz SR, Chauhan AK. Fibronectin splicing variants containing extra domain a promote atherosclerosis in mice through toll-like receptor 4. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:2391–2400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan MH, Sun Z, Opitz SL, Schmidt TE, Peters JH, George EL. Deletion of the alternatively spliced fibronectin eiiia domain in mice reduces atherosclerosis. Blood. 2004;104:11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu M, Ortega CA, Si K, Molinaro R, Schoen FJ, Leitao RFC, Xu X, Mahmoudi M, Ahn S, Liu J, Saw PE, Lee IH, Brayner MMB, Lotfi A, Shi J, Libby P, Jon S, Farokhzad OC. Nanoparticles targeting extra domain b of fibronectin-specific to the atherosclerotic lesion types iii, iv, and v-enhance plaque detection and cargo delivery. Theranostics. 2018;8:6008–6024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Yafeai Z, Yurdagul A Jr., Peretik JM, Alfaidi M, Murphy PA, Orr AW. Endothelial fn (fibronectin) deposition by alpha5beta1 integrins drives atherogenic inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:2601–2614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain M, Dhanesha N, Doddapattar P, Chorawala MR, Nayak MK, Cornelissen A, Guo L, Finn AV, Lentz SR, Chauhan AK. Smooth muscle cell-specific fibronectin-eda mediates phenotypic switching and neointimal hyperplasia. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:295–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhanesha N, Chorawala MR, Jain M, Bhalla A, Thedens D, Nayak M, Doddapattar P, Chauhan AK. Fn-eda (fibronectin containing extra domain a) in the plasma, but not endothelial cells, exacerbates stroke outcome by promoting thrombo-inflammation. Stroke. 2019;50:1201–1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muro AF, Chauhan AK, Gajovic S, Iaconcig A, Porro F, Stanta G, Baralle FE. Regulated splicing of the fibronectin eda exon is essential for proper skin wound healing and normal lifespan. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:149–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doddapattar P, Dhanesha N, Chorawala MR, Tinsman C, Jain M, Nayak MK, Staber JM, Chauhan AK. Endothelial cell-derived von willebrand factor, but not platelet-derived, promotes atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:520–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ovchinnikova O, Robertson AK, Wagsater D, Folco EJ, Hyry M, Myllyharju J, Eriksson P, Libby P, Hansson GK. T-cell activation leads to reduced collagen maturation in atherosclerotic plaques of apoe(−/−) mice. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:693–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gandhi C, Khan MM, Lentz SR, Chauhan AK. Adamts13 reduces vascular inflammation and the development of early atherosclerosis in mice. Blood. 2012;119:2385–2391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boring L, Gosling J, Cleary M, Charo IF. Decreased lesion formation in ccr2−/− mice reveals a role for chemokines in the initiation of atherosclerosis. Nature. 1998;394:894–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharrett AR. Serum cholesterol levels and atherosclerosis. Coron Artery Dis. 1993;4:867–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chait A, Wight TN. Interaction of native and modified low-density lipoproteins with extracellular matrix. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2000;11:457–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yurdagul A, Jr., Sulzmaier FJ, Chen XL, Pattillo CB, Schlaepfer DD, Orr AW. Oxidized ldl induces fak-dependent rsk signaling to drive nf-kappab activation and vcam-1 expression. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:1580–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mambole A, Bigot S, Baruch D, Lesavre P, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L. Human neutrophil integrin alpha9beta1: Up-regulation by cell activation and synergy with beta2 integrins during adhesion to endothelium under flow. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drechsler M, Megens RT, van Zandvoort M, Weber C, Soehnlein O. Hyperlipidemia-triggered neutrophilia promotes early atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2010;122:1837–1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soehnlein O Multiple roles for neutrophils in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2012;110:875–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warnatsch A, Ioannou M, Wang Q, Papayannopoulos V. Inflammation. Neutrophil extracellular traps license macrophages for cytokine production in atherosclerosis. Science. 2015;349:316–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qu D, Wang L, Huo M, Song W, Lau CW, Xu J, Xu A, Yao X, Chiu JJ, Tian XY, Huang Y. Focal tlr4 activation mediates disturbed flow-induced endothelial inflammation. Cardiovasc Res. 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raines EW, Ferri N. Thematic review series: The immune system and atherogenesis. Cytokines affecting endothelial and smooth muscle cells in vascular disease. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1081–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.