Abstract

Background:

Insomnia is a common sleep disorder with symptoms including difficulty falling asleep and early awakening. Guipi decoction is widely used in clinical treatment of insomnia in China. However, there is a lack of systematic evaluation and analysis of Guipi decoction. Therefore, our study will provide efficacy assessments and adverse events assessments.

Methods:

A comprehensive search for randomized controlled trials of Gupi decoction treatments for insomnia will be carried in MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trial (CENTRAL), CINAHL, AMED and Chinese databases include CBM, CNKI, CQVIP, and Wanfang from their inceptions to May 2020. Relevant reference lists, Baidu Scholar and grey literature will also be checked. Two experienced reviewers will independently search all databases. Primary outcomes include Pittsburgh sleep quality index and clinical effective rate, and secondary outcomes include traditional Chinese medicine syndrome, adverse events, and Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Review Manager 5.3 software will be used analyze all data.

Results:

This article will be dedicated to assessing the efficacy and safety of Guipi decoction for insomnia.

Conclusion:

The conclusion of this systematic review will provide evidence to judge whether Guipi Decoction is an effective therapeutic intervention for patient with insomnia. Maybe these results could potentially be helpful for improving the therapeutic strategy of patients with insomnia.

PROSPERO registration number:

CRD 42020164911.

Keywords: Guipi decoction, insomnia, meta-analysis, protocol, systematic review, traditional Chinese medicine

1. Introduction

Insomnia is defined as a purely subjective complaint of dissatisfaction with sleep quality and quantity in spite of adequate opportunity for sleep, which is the most common sleep disorder among adults, especially affecting individuals of advanced age or with neurodegenerative disease.[1] It is characterized by persistent difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, along with associated daytime impairment.[2] As much as one-third of the population experiences transient insomnia symptoms at any given time.[3] For many people, insomnia is a persistent condition, with 74% reporting symptoms at least over one year.[4] In China, 45.4% of people have experienced insomnia in different degrees in the past month.[5] Long term insomnia not only brings great trouble to people's life and work, but also causes diseases such as depression,[6] anxiety disorders,[7] heart disease,[8] stroke,[9] hypertension,[10] diabetes,[11] dementia.[12] Meanwhile, insomnia is associated with an increased risk of car crashes, as well as injuries at home and at work.[13] Insomnia, and its comorbid problems, leads to high societal costs, mainly due to productivity losses.[14,15]

Generally speaking, the treatments for insomnia are divided into nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies. Cognitive behavioral treatment for insomnia (CBT-I) is an evidence-based non-pharmacologic treatment with large effects on insomnia severity,[16] and is recommended by international guidelines[17] as the first treatment option for insomnia, offering advantages over existing pharmacotherapies with regard to safety and durability of response.[18] Although the efficacy of CBT-I is still undisputed, problems with accessibility and cost effectiveness mean that many people with insomnia cannot benefit from this treatment.[19] Pharmacologic interventions are often prescribed for insomnia, including benzodiazepines and other nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotics. Sedative-hypnotics are categorized as high-risk medications, particularly among older adults, and are associated with preventable harm including falls, hip fractures, delirium, and death.[20,21] Observational studies suggest that most indications for sedative-hypnotic initiation in hospitals are potentially inappropriate.[22,23] Therefore, an increasing number of insomnia sufferers are seeking for complementary and alternative therapy for certain advantages like convenient, cheap, and less side effects.[24]

Chinese herb medicine has been used to manage insomnia for thousands of years. Guipi decoction is one of Chinese herb formulas, and it is widely used in clinical treatment of insomnia in China. However, there is a lack of systematic evaluation and analysis of Guipi decoction. Therefore, our study will provide efficacy assessments and adverse events assessments.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and registration

The protocol of this systematic review and meta-analysis has been registered on PROSPERO platform (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO) with an assigned registration number CRD42020164911, basing on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols statement guidelines.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

2.2.1. Types of study

All randomized controlled trials that investigate the efficacy and safety of Guipi decoction treatments for insomnia will be included. It will be excluded if studies using inappropriate random sequence generation methods such as alternate allocation or birth day. It will be considered a randomized controlled trial and will be included in this review if a study only mentions randomization and does not explain the randomization method.

2.2.2. Types of participants

Male or female patients diagnosed with insomnia are included. The diagnosis of insomnia needs to be consistent with ICSD-3 in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders II or Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia in China. There are no limitations on the age.

2.2.3. Types of interventions

The experimental group should be treated with Guipi decoction alone or in combination with western medicine. The control group received single therapy such as benzodiazepines, nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics, placebo, or other basic treatment. Combining therapy which cannot judge the effect of acupuncture will be excluded. The treatment duration is unlimited. Nursing measures should be consistent between the 2 groups.

2.2.4. Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes: The primary outcome includes Pittsburgh sleep quality index and clinical effective rate. Pittsburgh sleep quality index is comprised of 19 self-rated items in 7 factors and the total scores range from 0 to 21.[25] Clinical effective rate is calculated based on the criteria for the therapeutic effects of western medicine and traditional Chinese medicine, according to Guiding Principles for Clinical Research of New Chinese Medicine. Clinical recovery: sleep time has returned to normal or the sleep time at night has been more than 6 hours, deep sleep and energetic after waking up. Markedly effective: sleep has improved significantly, sleep time has increased by more than 3 hours, and sleep depth has increased. Effective: the symptoms have relieved, but the sleep time increases less than 3 hours longer than before. Invalid: no improvement or aggravation of insomnia. The total effective rate = (Clinical recovery + Markedly effective + Effective)/Total number of cases ×100%.[26]

Secondary outcomes: Syndrome according to standards for assessing traditional Chinese medicine. Adverse events caused by Guipi decoction, such as dizziness, nausea, vomiting, weariness, etc. Daytime function measured by standardized sleep-related scales, for example, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.[27]

2.3. Data sources and search strategy

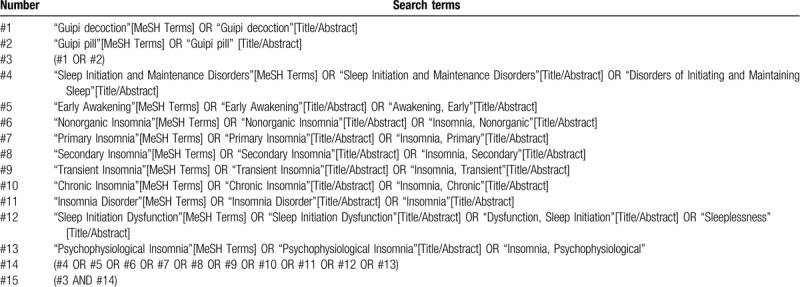

We will search MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trial, CINAHL, AMED, and Chinese databases include CBM, CNKI, CQVIP, and Wanfang from their inceptions to May 2020. The language of publication will be limited to Chinese and English. But it will not limit the race of the participants. We will also check the reference lists of the relevant articles and perform a manual check on Baidu Scholar and grey literature. The searching strategies for PubMed are listed in Appendix Table 1 for details, and will be modified and used similarly for the other databases.

Table 1.

Search strategies for the PubMed.

2.4. Study selection and data extraction

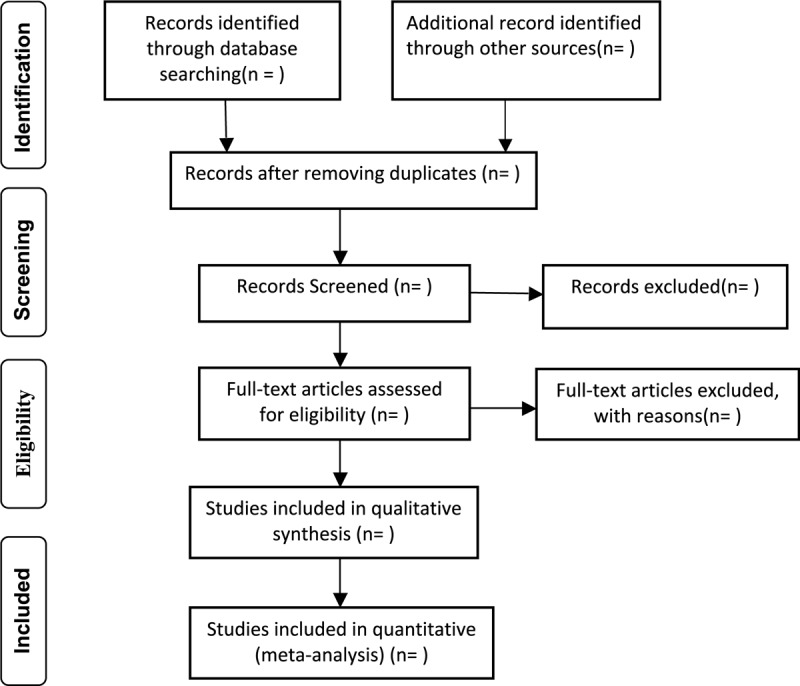

Two experienced reviewers (WY, SKJ) will independently search all databases according to the search strategies, read the titles and abstracts to select potential references, exclude obviously unrelated literature, and delete duplicated relevant research abstracts. Then, they will read the full text to assess eligible studies. If the information is incomplete, the reviewer should contact the author to obtain complete information. If there is a disagreement it will be resolved through discussion or a third reviewer (YDD). The complete selection process will be presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process.

Data extraction will be performed by 2 reviewers (WY, SKJ) independently. Information extracted from included studies will include: literature characteristics (the first author's name, journal, year of publication, country, aim, funding sources); participant information (age, gender, diagnose criteria, exclusion criteria, disease duration or stage, sample size, assessment of compliance, and withdrawals); intervention information (details of intervention and control, treatment duration); and outcome (results, adverse events, duration of follow-up, subgroup analysis).

2.5. Data analysis

2.5.1. Risk of bias assessment

Two review authors (WY, SKJ) will independently assess the risk of bias in included studies using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool by considering the following characteristics:

-

1.

Randomization sequence generation,

-

2.

Allocation concealment,

-

3.

Blinding of outcome assessment,

-

4.

Incomplete outcome data,

-

5.

Selective outcome reporting,

-

6.

Other sources of bias.

Each domain will be divided into 3 categories: low risk of bias, high risk of bias, and unclear risk of bias. Any discrepancy in the assessment of risk of bias will be resolved by discussion and a third review author will be consulted if necessary.

2.5.2. Date synthesis

Data will be analyzed using Rev Man software (Version 5.3) provided by the Cochrane Collaboration (www.cochrane.org). A meta-analysis using random or fixed effects models will be conducted to pool the data. Dichotomous data will be adopted and expressed as risk ratio. Continuous data will be pooled and presented as mean difference or standardized mean difference. The confidence interval is established at 95%.

2.5.3. Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity will be examined using the I2 test (α = 0.1) according to the Cochrane Handbook (0%–40%, might not be important, 30%–60%, may represent moderate heterogeneity, 50%–90%, may represent substantial heterogeneity, and 75%–100% may represent considerable heterogeneity). If the I2 value is higher than 50%, the random effects model will be used. Otherwise the fixed effect model is involved.

2.5.4. Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis

If heterogeneity is evaluated as significant, we will perform a subgroup analysis to explore the possible causes of heterogeneity according to the difference in participant characteristics, interventions, controls, and outcome measures. We will use sensitivity analysis to enhance the credibility of the results by eliminating studies with high risk of bias, missing data studies, and outliers.

2.5.5. Assessment of reporting bias

Funnel plots will be used to evaluate the reporting biases when more than 10 trials are included. A symmetrical distribution of funnel plot data indicates that there is no reporting bias. On the contrary, an asymmetry distribution of funnel plot data implies reporting bias, and we will attempt to explain possible reasons.

2.5.6. Grading the quality of evidence

We will evaluate the quality of evidence through guidelines of the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE).[28] The evidence quality will be ranked by 4 levels: high quality, moderate quality, low quality, and very low quality.

2.5.7. Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval will be unnecessary because the data included in this systematic review come from published literature and there will be no concerns regarding privacy. Findings of this research will be disseminated in a peer-reviewed journal or conference presentations.

3. Discussion

Insomnia is a common sleep disorder with symptoms including difficulty falling asleep and early awakening. With the increasingly fast pace of our life, the incidence of insomnia is also increasing. Because of time consumption and lack of adequately trained providers, and economic issues, CBT is rarely used in routine clinical practice, and pharmacotherapies for insomnia can cause serious adverse effects. Given the limitations of both CBT and pharmacological therapy, it is necessary to search for complementary and alternative therapy with higher effective rate and less side effects for insomnia. Guipi decoction originated in Song Dynasty, and has been used for more than 700 years in the treatment of insomnia. However, there is no systematic review to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Guipi Decoction for insomnia. Therefore, it is necessary to perform a high-quality systematic review and meta-analysis of it. Maybe these results could potentially be helpful for improving the therapeutic strategy of patients with insomnia.

Author contributions

Mao Li, Rui Lan, and Dongdong Yang contributed to the conception of the study. The manuscript protocol was drafted by Mao Li and was revised by Dongdong Yang and Rui Lan. The search strategy was developed by all the authors and performed by Yong Wen and Kejin Shi, who also independently screened the potential studies, extracted data from the included studies, assessed the risk of bias, and completed the data synthesis. Dongdong Yang arbitrated in cases of disagreement and ensured the absence of errors. All authors approved the publication of the protocol.

Conceptualization: Mao Li, Rui Lan, Dongdong Yang.

Data curation: Mao Li, Kejin Shi.

Formal analysis: Yong Wen, Kejin Shi.

Funding acquisition: Rui Lan, Dongdong Yang.

Methodology: Yong Wen, Kejin Shi.

Software: Mao Li, Yong Wen, Kejin Shi.

Supervision: Rui Lan, Dongdong Yang.

Writing – original draft: Mao Li.

Writing – review & editing: Mao Li.

Footnotes

Abbreviation: CBT-I = Cognitive behavioral treatment for insomnia.

How to cite this article: Li M, Lan R, Wen Y, Shi K, Yang D. Guipi decoction for insomnia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2020;99:27(e21031).

This project is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81973618). The sponsors are not involved in design, execution, or writing the study.

The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

- [1].Belfer SJ, Bashaw AG, Perlis ML, et al. A Drosophila model of sleep restriction therapy for insomnia. Mol Psychiatry 2019;doi:10.1038/s41380-019-0376-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and con-sequences. J Clin Sleep Med 2007;3:S7–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Morin CM. Insomnia disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015;1:15037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ohayon MM, Reynolds CF. Epidemiological and clinical relevance of insomnia diagnosis algorithms according to the DSM-IV and the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD). Sleep Med 2009;10:952–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Soldatos CR, Allaert FA, Ohta T, et al. How do individuals sleep around the world? Results from a single-day survey in ten countries. Sleep Med 2005;6:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Vargas I, Perlis ML. Insomnia and depression: clinical associations and possible mechanistic links. Curr Opin Psychol 2019;34:95–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Blank M, Zhang J, Lamers F, et al. Health correlates of insomnia symptoms and comorbid mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. Sleep 2015;38:197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zheng B, Yu C, Lv J, et al. Insomnia symptoms and risk of cardiovascular diseases among 0.5 million adults: a 10-year cohort. Neurology 2019;93:e2110–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wu MP, Lin HJ, Weng SF, et al. Insomnia subtypes and the subsequent risks of stroke: report from a nationally representative cohort. Stroke 2014;45:1349–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kawada T. Risk factors of insomnia in the elderly with special reference to depression and hypertension. Psychogeriatrics 2020;20:360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].McWhorter KL, Park YM, Gaston SA, et al. Multiple sleep dimensions and type 2 diabetes risk among women in the Sister Study: differences by race/ethnicity. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2019;7:e000652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jee HJ, Shin W, Jung HJ, et al. Impact of sleep disorder as a risk factor for dementia in men and women. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2020;28:58–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Léger D, Bayon V, Ohayon MM, et al. Insomnia and accidents: cross-sectional study (EQUINOX) on sleep-related home, work and car accidents in 5293 subjects with insomnia from 10 countries. J Sleep Res 2014;23:143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, et al. The economic burden of insomnia: direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia syndrome, insomnia symptoms, and good sleepers. Sleep 2009;32:55–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, et al. Insomnia and its relationship to health-care utilization, work absenteeism, productivity and accidents. Sleep Med 2009;10:427–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].van Straten A, van der Zweerde T, Kleiboer A, et al. Cognitive and behavioral therapies in the treatment of insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2018;38:3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res 2017;26:675–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Riemann D, Perlis ML. The treatments of chronic insomnia: a review of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and psychological and behavioral therapies. Sleep Med Rev 2009;13:205–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kay-Stacey M, Attarian H. Advances in the management of chronic insomnia. BMJ 2016;354:i2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lyons PG, Snyder A, Sokol S, et al. Association between opioid and benzodiazepine use and clinical deterioration in ward patients. J Hosp Med 2017;12:428–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].By the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:2227–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pek EA, Remfry A, Pendrith C, et al. High prevalence of inappropriate benzodiazepine and sedative hypnotic prescriptions among hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med 2017;12:310–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Garrido MM, Prigerson HG, Penrod JD, et al. Benzodiazepine and sedative-hypnotic use among older seriously Ill veterans: choosing wisely. Clin Ther 2014;36:1547–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bertisch SM, Wells RE, Smith MT, et al. Use of relaxation techniques and complementary and alternative medicine by American adults with insomnia symptoms: results from a national survey. J Clin Sleep Med 2012;8:681–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chung KF, Kan KK, Yeung WF. Assessing insomnia in adolescents: comparison of Insomnia Severity Index, Athens Insomnia Scale and Sleep Quality Index. Sleep Med 2011;12:463–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991;14:540–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]