Abstract

Across vertebrates, species with intense male mating competition and high levels of sexual dimorphism in body size generally exhibit dimorphism in age-specific fertility. Compared to females, males show later ages at first reproduction and earlier reproductive senescence because they take longer to attain adult body size and musculature, and maintain peak condition for a limited time. This normally yields a shorter male duration of effective breeding, but this reduction might be attenuated in species that frequently employ coalitionary aggression. Here we present comparative genetic and demographic data on chimpanzees from three long-term study communities (Kanyawara: Kibale National Park, Uganda; Mitumba and Kasekela: Gombe National Park, Tanzania), comprising 585 male risk years and 112 infants, to characterize male age-specific fertility. For comparison we update estimates from female chimpanzees in the same sites, and append a sample of human foragers (the Tanzanian Hadza). Consistent with the idea that aggressive mating competition favors youth, chimpanzee males attained a higher maximum fertility than females, followed by a steeper decline with age. Males did not show a delay in reproduction compared to females, however, as adolescents in both sites successfully reproduced by targeting young, subfecund females, who were less attractive to adults. Gombe males showed earlier reproductive senescence and a shorter duration of effective breeding than Gombe females. By contrast, older males in Kanyawara generally continued to reproduce, apparently by forming coalitions with the alpha. Hadza foragers showed a distinct pattern of sexual dimorphism in age-specific fertility as, compared to women, men gained conceptions later but continued reproducing longer. In sum, both humans and chimpanzees showed sexual dimorphism in age-specific fertility that deviated from predictions drawn from primates with more extreme body-size dimorphism, suggesting altered dynamics of male-male competition in the two lineages. In both species, coalitions appear important for extending male reproductive careers.

Keywords: Chimpanzees, sexual dimorphism, age-specific fertility, effective breeding duration, foragers, Hadza

1.0. Introduction

Comparisons with chimpanzees and other apes show that human life history has diverged from the general hominid pattern in puzzling ways (reviewed in Gurven, 2012; Hawkes and Paine, 2006; Robson and Wood, 2008). Humans grow slowly, have an extended period of juvenile dependency, reproduce at a late age, and live for a long time, all traits that are normally associated with slow reproduction. Yet humans also maintain short birth intervals for a hominid, resulting in high fertility. And although women live longer than other primates, they cease reproduction well before the end of the life span (Blurton Jones et al., 2002; Gurven and Kaplan, 2007; Hawkes, 2003).

Most of the life history literature justifiably focuses on females, as they set the pace of reproduction (Wood, 1994). However, demographers now appreciate that two-sex models are sometimes necessary to fully understand both population dynamics and life history evolution (e.g. Caswell and Weeks, 1986; Chan et al., 2017; Rankin and Kokko, 2007; Schindler et al., 2015). This is particularly true when males and females exhibit divergent mortality rates and age-specific reproductive schedules. For example, Tuljapurkar and colleagues (2007) argued that if a nontrivial portion of men older than 50 have offspring with younger women, selection should favor investment in male life span, potentially explaining women’s post-reproductive longevity as a byproduct (cf. Coxworth et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2012).

Sex differences in patterns of age-specific fertility are widespread in mammals, and hypothesized to be driven by intrasexual mating competition (Clutton-Brock and Isvaran, 2007). Specifically, in species with polygynous mating systems, sexual selection often favors weaponry and large body size in males, because these enhance fighting ability (e.g. Emlen, 2008; Lindenfors et al., 2007; Plavcan, 2004; Weckerly, 1998). Because males in such species take longer to reach adult body size, develop adult musculature, and become effective competitors, they start reproducing later than females (Clutton-Brock, 2016; Georgiadis, 1985; Leigh, 1992). And because males in highly competitive environments maintain peak condition for a limited time, they cease reproducing earlier than females (Clutton-Brock, 2016). The result is a shorter male “duration of effective breeding,” defined as “the length of time during which the average individual of one sex can expect a substantial amount of reproductive success” (Clutton-Brock and Isvaran, 2007). In monogamous species, by contrast, males and females show similar durations of effective breeding, because of less intense mating competition.

Sex differences in age-specific fertility are hypothesized to contribute to sexual dimorphism in senescence and life span. Longevity is reduced in the sex with the shorter duration of effective breeding for at least two reasons (Clutton-Brock, 2016). First, mating competition itself imposes energetic costs, and often leads to injury, directly promoting senescence. Second, decreasing the duration of effective breeding weakens selection for investments in long-term maintenance that favor longevity. Clutton-Brock and Isvaran (2007: 3097) demonstrated that, across a range of vertebrates, “the magnitude of sex differences in life expectancy is consistently related to the magnitude of sex differences in the [duration of effective breeding]”.

Data on male reproduction are rarely available for non-human primates, both because of their slow life histories, and the difficulty of assessing paternity in the wild. Clutton-Brock and Isvaran (2007) included such data from only three species – mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx: Setchell et al., 2005a), yellow baboons (Papio cynocephalus: Altmann et al., 1988), and Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus: Kuester et al., 1995). All three live in multi-male, multi-female groups in which females can mate with more than one male during a single ovarian cycle. However, there are clear differences among these species in the intensity and effectiveness of male mate guarding. These produce differences in male reproductive skew. In mandrills, alpha males account for 94% of periovulatory mate guarding and 69% of paternities (Setchell et al., 2005b). Yellow baboons show lower levels of reproductive skew, with alpha males siring around one-third of offspring (Alberts et al., 2006). Barbary macaques show lower levels still (Kuester and Paul, 1992). Consistent with the hypotheses outlined above, mandrills are the most sexually dimorphic of these species (male body mass/female body mass = 2.45), followed by yellow baboons (2.06) and Barbary macaques (1.44) (Delson et al., 2000; Plavcan, 2004; Smith and Jungers, 1996). Mandrills also show the largest sex difference in duration of effective breeding (male/female = 0.59), followed by the baboons (0.62) and macaques (0.66) (Clutton-Brock and Isvaran, 2007). More primate data are needed, however, to sample a wider taxonomic range (including hominids), and additional mating systems. Particularly interesting are species that frequently employ coalitionary aggression, as coalitions may enable males to extend their duration of effective breeding, despite declining condition with age.

Here we present genetic and demographic data from three long-term study communities (Kanyawara: Kibale National Park, Uganda; Mitumba and Kasekela: Gombe National Park, Tanzania) to characterize age-specific fertility in both male and female chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii). Chimpanzees live in multi-male, multi-female communities in which mating is highly promiscuous (Goodall, 1986; Nishida, 1979). Reproductive conflict is intense, both in the long term, as males fight for status amongst themselves, and in the short term, as males use aggression to guard estrous females (Muller, 2002, 2017; Muller et al., 2007, 2009). These struggles impose costs on males, including elevated levels of stress hormones (Muller and Wrangham, 2004), wounding, and even death (Fawcett and Muhumuza, 2000; Kaburu et al., 2013; Pruetz et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2014). Consequently, chimpanzee males are expected to show a later onset and earlier termination of reproduction compared to females, together with a higher peak reproductive rate.

Despite intense mating competition in chimpanzee communities, however, low-ranking males routinely sire more offspring than predicted by a strict priority of access model (i.e. in which a male’s position in a dominance hierarchy, based on fighting ability, largely determines his reproductive success: Boesch et al., 2006; Newton-Fisher et al., 2010; Surbeck et al., 2017; Wroblewski et al. 2009). In Gombe, low-ranking males were previously reported to father offspring primarily with young females (Wroblewski et al. 2009). A similar pattern was observed in Budongo chimpanzees (Newton-Fisher et al., 2010). Prior work at Kanyawara has shown that adult males prefer older females as mating partners (Muller et al., 2006). Consequently, multiparous females (those who have previously given birth to two or more infants) generally incite more intense competition than nulliparous females (who have not yet given birth) or primiparous females (who have had only one infant). Similar preferences by adult males for older mothers have been reported from Gombe (Tutin and McGinnis, 1981) and Mahale (Hasegawa and Hiraiwa-Hasegawa, 1983; Takasaki, 1985). If low-ranking, adolescent males systematically pursue the young females that are neglected by higher-ranked adults, then they might initiate their reproductive careers earlier, reducing the predicted sex difference in age-specific fertility.

Additionally, coalitions and alliances are important for status striving and reproduction by male chimpanzees (Bray et al., 2016; Duffy et al., 2007; Gilby et al., 2013; Mitani, 2009; Muller and Mitani, 2005; Nishida, 1983; Nishida and Hosaka, 1996; Watts, 1998, 2018). Coalitions could potentially mitigate dimorphism in age-specific fertility by allowing older, politically connected males to extend their reproductive careers (Jaeggi et al., 2017), as they do in humans (Marlowe, 2000). Chimpanzees also show less dimorphism in body mass than mandrills, yellow baboons, and Barbary macaques, with a ratio of male/female body mass around 1.3 (Plavcan, 2004). Consequently, the duration of effective breeding in chimpanzees is expected to be less sexually dimorphic than in these other primates.

Sexual dimorphism in chimpanzee age-specific fertility could be expected to exceed that of human foragers, however (Jaeggi et al., 2017). Humans show less dimorphism in body mass than do chimpanzees, with a forager mean of 1.19 for male/female mass (Marlowe and Berbesque, 2012). This comparison is complicated by the fact that humans show dimorphism in both fat (favoring females) and musculature (favoring males), whereas chimpanzees show little or no fat dimorphism (Dixson, 2009; Pontzer et al., 2016). Autopsy studies that directly assay muscle tissue, however, are consistent with body mass data in classifying humans as less sexually dimorphic than the African apes (though at present only bonobos and a small number of gorillas have been sampled: Muller and Pilbeam, 2017; Zihlman and Bolter, 2015; Zihlman and McFarland, 2000). This lower level of dimorphism is ostensibly consistent with the observation that men’s and women’s reproductive schedules can be closely linked, owing to the existence of long-term pair bonds (Kaplan et al., 2010).

Other aspects of human fertility, however, complicate this view of reduced competition among mostly monogamous males. First, forager men show a consistent delay in age at first reproduction compared to women, as women tend to marry older men (Blurton Jones, 2016; Hill and Hurtado, 1996; Howell, 2000; Tuljapurkar et al., 2007). This delay implies some form of competition that denies reproductive access to young men. Second, menopause ends women’s reproductive careers in the mid to late forties, whereas a significant number of older forager men divorce their post-reproductive wives and have children with younger women (Blurton Jones, 2016; Hill and Hurtado, 1996; Howell, 2000). Consequently, the duration of effective breeding in humans favors men. Estimates for Hadza foragers, for example, are 39 years for men, and 30 years for women (Blurton Jones, 2016: 256). This difference in the duration of effective breeding means that in humans the operational sex ratio (a measure of the number of reproductively active males to fecundable females) is generally skewed towards men. Such skew is expected to promote increased competition (Marlowe and Berbesque, 2012).

To test whether humans have less pronounced sexual dimorphism in age-specific fertility than chimpanzees, we evaluate comparative data from the Hadza, a group of Tanzanian foragers (Blurton Jones, 2016). Hadza patterns of age-specific fertility broadly mirror those found in other small-scale foraging and horticultural societies (reviewed in Tuljapurkar et al., 2007). We focus on Hadza data here because they were not included in the populations considered by Tuljapurkar and colleagues, and because they represent the largest fertility sample from a non-sedentary hunting and gathering population, comprising more than 10,000 risk years and >700 births.

2.0. Materials and methods

Observations of chimpanzees in Gombe National Park, western Tanzania, began in 1960, with the central Kasekela community (Goodall, 1986). Habituation of Gombe’s northern Mitumba community was initiated in 1985 (Wilson, 2012). Chimpanzees in the Kanyawara community, Kibale National Park, southwestern Uganda, were first studied systematically from 1983 to 1985, and have been continuously monitored since 1987 (Isabirye-Basuta, 1988; Muller and Wrangham, 2014). In both Gombe and Kibale, non-invasive sample collection for genetic analyses, including paternity assignment, began in the early 1990s (Goldberg and Wrangham, 1997; Morin et al., 1994). This study includes data from the first to last years in which at least 50% of the offspring born alive had fathers identified, and over 50% of candidate males for paternity were sampled. For Kasekela we included infants born between 1988 and 2012, and for Mitumba 2004 to 2012. For Kanyawara we included infants born between 2000 and the end of September 2016.

Candidate males for paternity were those alive and at least 9 years old at the time of conception (9.3 is the earliest recorded age of a chimpanzee father in the wild: Langergraber et al., 2012). Conception was assumed to occur 228 days prior to birth (Nissen and Yerkes, 1943). Two Kasekela males were excluded from the analyses: Pax was physiologically incapable of siring offspring, owing to an injury, and Spindle was not genetically sampled.

Infants that died before their first birthday were excluded from all analyses, because genotypes could not be obtained for them. This included 6 infants that died in their first year at Kanyawara, 19 at Kasekela, and 2 at Mitumba. In Kasekela, one set of twins (GLI and GLD, same sire) was treated as a single conception/offspring. Of the infants included in the study, more than 85% were assigned sires. Table 1 shows the numbers of male risk years and infants from each of the three study communities.

Table 1.

Male demographic sample sizes by study community

| Study site | Unique males | Risk years | Infants (genotyped) | Infants (total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kasekela (Gombe) | 26 | 324.10 | 46 | 56 |

| Mitumba (Gombe) | 9 | 37.57 | 10 | 12 |

| Kanyawara (Kibale) | 25 | 223.55 | 39 | 44 |

| Total | 60 | 585.22 | 95 | 112 |

Life table calculations followed standard methods described in Hill et al. (2001) and Bronikowski et al. (2016). Male age-specific fertility (mx) was calculated by dividing the number of conceptions in an interval by the number of chimpanzees represented in that interval. Genotypes were not available for 17 of 112 infants born in the study period (Table 1). In the life table, these conceptions were distributed across male age categories in the same proportions as infants with known paternities (i.e. if 10% of genotyped infants in a site were born to males of age x, then 10% of the unknown paternities from that site were assigned to age x). Age-specific reproductive rate (the probability of both surviving to a particular age and reproducing at that age) was calculated by multiplying mx by age-specific survivorship (lx). Net reproductive rate (the average lifetime number of offspring) was calculated by summing age-specific reproductive rates from birth through the age at which lx reached 0.

For comparative purposes, female fertility rates were calculated in the same manner as those of males. As described above, this method departs from conventional life-table calculations by (1) considering female age at conception, rather than birth, and (2) excluding infants that did not live to 1 year of age. Female data were chosen to approximately match the male study periods, with Kasekela data from 1988–2012, Mitumba data from 2004–2012, and Kanyawara data from 1998–2016 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Female demographic sample sizes by study community

| Study site | Unique females | Risk years | Infants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kasekela (Gombe) | 49 | 487.01 | 55 |

| Mitumba (Gombe) | 11 | 80.54 | 12 |

| Kanyawara (Kibale) | 47 | 348 | 50 |

| Total | 107 | 915.55 | 117 |

Data on age-specific survivorship came from Muller and Wrangham (2014) for Kanyawara, and Bronikowski et al. (2016) for Gombe. The mortality samples were pooled by combining risk years and deaths from the two sites. Yearly mortality rate (qx) was calculated by dividing the number of deaths in an interval by the number of chimpanzees represented in that interval. Yearly survival rate (px) was calculated by subtracting qx from 1. Probability of survival from birth to age x (lx) was calculated by multiplying all of the yearly survival rates (px) from age 0 to age x-1.

Clutton-Brock and Isvaran (2007) calculated the duration of effective breeding by fitting a quadratic function to data on the mean number of offspring produced by age. The time period (length of the x axis) over which the height of the quadratic curve exceeded one-fourth its maximum value was considered the duration of effective breeding. If the curve predicted values more extreme than the actual minimum and/or maximum ages of observed breeding, then the observed values were used to calculate the duration of effective breeding. For the chimpanzee data, both the maximum and minimum values predicted from the quadratic curve at one-fourth its maximum height were more extreme than the ages of observed breeding, so observed values were used. We also calculated duration of effective breeding from our Bayesian model of age-specific fertility (see below), following the procedure described for the quadratic model.

Individuals who were born before the study began, together with immigrants to the community, were assigned ages by comparing their physical and behavioral characteristics with those of chimpanzees of known ages. Young adult chimpanzees (15–20 years old) exhibit a suite of morphological characteristics that include thick glossy black hair, unbroken teeth, and light facial creasing. Chimpanzees older than 35 years display thinning brown or gray hair with less sheen, worn or broken teeth, and saggy, wrinkled faces. These individuals also move more slowly and deliberately. Female ages were further calibrated based on the apparent ages of their offspring. Hill et al. (2001) provide additional details on estimating the ages of wild chimpanzees in these study sites.

2.1. Inference on age-specific fertility

We developed a Bayesian model for inference on age-specific fertility that facilitates exploration of age trajectories beyond the typical exponential quadratic model. With this approach, we modeled baseline average age-specific fertility for a given age x ≥ α, where α is the age at first reproduction as

| (1) |

where g0(x) is the baseline age-specific fertility function, β0, β3 ⊰ (−∞, ∞) and β1, β2 ≥ 0 are fertility parameters to be estimated. A special case for the average fecundity function in Eq. (1) is the quadratic fecundity model generally used for mammals and birds (McCleery et al. 2008; Brown and Roth 2009; Dugdale et al. 2011), whereby parameter β3 = 0.

Our inference model uses Eq. (1) as a link function within a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) where Yxi is a random variable for the number of offspring produced by individual i at age x, with realizations . Random effects are included as

| (2) |

where zi is 1 × ni identity vector that assigns 1 in the ith position and 0 elsewhere, ni is the number of individuals in the dataset, and ui is a random effect parameter for the ith individual. Thus, the random vector of dimension ni × 1 is u ~ N(0, σ2 I), where σ2 is the random effects variance and I is an ni × ni identity matrix.

Given that females produce at most one offspring per year, we have that Yxi | ui ~ Bern(pxi), where pxi = exp(zi ui) g0(xi), bound such that pxi ⊰ [0, 1]. Males can produce more than one offspring per year, thus we have that Yxi | ui ~ Pois(λxi), where the Poisson parameter is λxi = exp(zi ui) g0(xi). The conditional likelihood function is therefore

| (3) |

where β is the vector of fecundity parameters to be estimated and the Bernoulli and Poisson parameters are calculated from Eq. (2). The posterior for the Bayesian model is then given by

| (4) |

where the first two terms on the right-hand-side of Eq. (4) are the full likelihood with initial term given by the conditional likelihood (3) and the second term is the multivariate normal density for the random effects, while the last two terms are the priors for the fecundity and random effect variance parameters. The matrix Z is a design matrix with row vectors zxi = zi and y is the vector of observed offspring.

We used a MCMC with Metropolis-Hastings (Metropolis et al. 1953; Hastings 1970) algorithm to sample the unknown parameters and random effects and used potential scale reduction factor (Gelman et al. 2013) to assess convergence from different parallel runs with different initial parameters. We tested two different models, namely the model with baseline average fecundity given in Eq. (1), and a null model where the parameter β3 = 0 (a typical quadratic model). For model comparison we used the deviance information criterion (DIC) (Spiegelhalter et al. 2002), where the model with lowest DIC is assumed to have higher support from the data.

All chimpanzee maternities were known; however, there were 17 offspring with unknown paternities, which we incorporated into the estimation procedure. In order to achieve this, we first found all males 9 or older present in the corresponding community during the time of conception of the offspring with unknown paternities. We initiated the model by assigning one father, say i, per offspring from the available pool of adult males. Then, at each step of the model, the model proposed that the paternity belonged to a father j from the available pool and accepted or rejected this new paternity using a Metropolis procedure by means of the likelihood function. This ensured that paternities were assigned with higher probability to those fathers that had higher reproductive output, while accounting for the uncertainty in the unknown paternities.

We ran both models (for each sex and then to compare male fertility between the Kibale and Gombe males) for 55,000 iterations, with a burn-in of 5001. We thinned the sequences after each 10 iterations. To assess convergence, we ran four parallel iterations of the MCMC with different starting parameters.

2.2. Interpretation of the age-specific model

The conventional quadratic model for age-specific fertility is a special case of the model we propose in Eq. (1), namely where parameter β3 = 0. For the quadratic model, the age at maximum average fertility, xm = w + α, can be calculated where

| (5) |

The model we propose in Eq. (1) requires numerical estimation of the age at maximum average fertility, which is reached when the third-degree polynomial

| (6) |

Therefore, to estimate xm = w + α and its 95% credible intervals for each sex or community for the average individual (i.e. ui = 0), we used a Newton approximation at each vector of sampled parameters after burn-in. To obtain the maximum average fecundity and its 95% credible intervals, we calculated the corresponding value as gm = g0(xm - α) for each vector of parameters after burn-in.

In addition, we extracted the posterior densities of the lower and upper bounds of the effective breeding period from the maximum fecundity produced by each set of parameters, gm, as described above, and then found the lower, xl, and upper, xu, ages, such that g(xl - α | xl < xm) = g(xu - α | xl > xm) = 0.25 gm for that set of parameters. We then calculated the duration of effective breeding for each pair (xl, xu) and their 95% credible intervals.

We performed all our analyses in the free-open source software R (R Core Team 2019).

2.3. Behavioral and genetic data

In Kanyawara, male dominance ranks were assigned based on 13,948 dyadic interactions among 27 males, spanning January 1993 through 2017. Wins and losses were assigned based on the directionality of pant-grunts and other signals of subordinance, and submissive responses to received aggression (threats or attacks). An Elo rating method was used to assign relative ranks on each day of the study period for males 9 and older (Albers and de Vries, 2001). Males in 1993 were assigned a starting score of zero, and males that reached adolescence (beginning at age 9) during the study period were assigned a starting score one point below the lowest-ranking male in the hierarchy on the day of their first aggressive interaction with an adult male. The k-constant in the Elo rating equation was set to 20. Elo scores were ultimately transformed into ordinal ranks, which were standardized for the number of males in the community (standardized rank = (n-r)/(n-1), where n is the number of males in the hierarchy and r is a male’s ordinal rank in the hierarchy).

In Gombe, male dominance hierarchies were constructed for each of the two communities based on dyadic pant-grunt interactions among males aged 9 or older. In Kasekela, dominance ranks were assigned based on 7517 pant-grunts among 38 males, spanning February 1978 to December 2015. In Mitumba, ranks were assigned based on 1366 pant-grunts among 15 males, spanning November 1993 to January 2016. Rank scores were calculated for males (beginning at age 9) with the Elo rating method (Albers and de Vries, 2001), using the EloOptimized package in R (Feldblum et al., 2018), with a default k-constant value of 100 and starting values for males at 1000. Ordinal ranks were then generated and standardized to the number of males in the hierarchy, as described for Kanyawara above.

In Gombe, most individuals were typed at 8–11 microsatellite loci. Fathers were identified using the exclusion principle, and confirmed with likelihood methods using the program CERVUS 3.0 (Kalinowski et al., 2007). Walker et al. (2017) provide detailed information on sample collection, DNA extraction, and genotyping at Gombe, including a complete list of paternities for 65 offspring.

The Kanyawara chimpanzees were genotyped at 19 microsatellite loci using a semi-nested multiplex PCR assay as described previously (Langergraber et al., 2007; Arandjelovic et al., 2009). Fecal samples were collected from individually identifiable chimpanzees immediately following defecation and preserved either at −20°C in RNAlater (Scully et al., 2018) or at room temperature using a two-step ethanol-Silica method (Nsubuga et al., 2004). Fecal DNA was extracted using the QIAamp Stool DNA minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). CERVUS 3.0 (Kalinowski et al., 2007) was used to infer paternity via maximum likelihood.

2.4. Human data

Hadza fertility data were collected between 1992 and 2000 by Nicholas Blurton Jones. Paternities were assigned based on women’s self-reports. Although this method could theoretically introduce error not present in the chimpanzee data, Blurton Jones (2016) notes that Hadza women were not reluctant to name men other than the current partner as fathers of their children. Women’s age-specific fertility estimates came from 688 births over 4524 risk years to women with Hadza husbands only, starting at age 10. Men’s estimates came from 771 births over 6149 risk years, starting at age 10. Hadza duration of effective breeding (DEB) was calculated in the same manner described for chimpanzees above (Blurton Jones 2016: 256). Methods for age estimation and details of the reproductive history interviews are provided in Blurton Jones (2016).

3.0. Results

The combined male chimpanzee fertility sample included 585 risk years from 60 unique males, and 112 conceptions, 95 of which were attributed to known sires. Table 3 delineates male risk years and confirmed paternities by age and study community. The female fertility sample included 915 risk years from 107 unique females, and 117 infants. Table 4 delineates female risk years and infants by age and study community. Most of the Gombe risk years came from Kasekela, because the Mitumba community was smaller and more recently habituated.

Table 3.

The sample of individual male risk years and known paternities by study community

| Kasekela | Mitumba | Kanyawara | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Risk years | Infants | Risk years | Infants | Risk years | Infants |

| 9 | 18.00 | 6.00 | 12.00 | |||

| 10 | 18.04 | 4.96 | 12.57 | 1 | ||

| 11 | 15.00 | 1 | 2.43 | 11.48 | 1 | |

| 12 | 12.63 | 1 | 2.00 | 9.32 | 1 | |

| 13 | 12.00 | 2 | 2.00 | 9.16 | 1 | |

| 14 | 13.00 | 1 | 1.96 | 9.65 | 1 | |

| 15 | 14.42 | 4 | 1.00 | 6.58 | ||

| 16 | 13.00 | 6 | 1.00 | 1 | 6.12 | 3 |

| 17 | 13.85 | 4 | 2.00 | 7.00 | ||

| 18 | 12.40 | 1 | 2.00 | 3 | 6.08 | 1 |

| 19 | 12.75 | 3 | 2.00 | 3 | 6.00 | 4 |

| 20 | 12.00 | 2 | 2.00 | 1 | 5.51 | 1 |

| 21 | 12.00 | 2 | 2.00 | 3.70 | 2 | |

| 22 | 13.00 | 1 | 1.88 | 1 | 3.00 | |

| 23 | 12.02 | 1 | 1.00 | 3.12 | 1 | |

| 24 | 12.00 | 4 | 1.00 | 4.02 | ||

| 25 | 12.00 | 3 | 0.88 | 4.12 | 3 | |

| 26 | 11.24 | 1.00 | 1 | 5.00 | 1 | |

| 27 | 11.00 | 2 | 0.47 | 4.98 | 2 | |

| 28 | 10.25 | 6.00 | 5.00 | 1 | ||

| 29 | 8.26 | 1 | 5.00 | 1 | ||

| 30 | 8.00 | 5.12 | ||||

| 31 | 7.30 | 2 | 6.00 | |||

| 32 | 7.00 | 1 | 5.77 | 2 | ||

| 33 | 5.63 | 5.51 | 2 | |||

| 34 | 5.21 | 1 | 4.12 | 1 | ||

| 35 | 4.88 | 1 | 4.15 | |||

| 36 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 2 | |||

| 37 | 4.00 | 1 | 3.00 | |||

| 38 | 4.00 | 3.12 | ||||

| 39 | 3.54 | 1 | 4.00 | 2 | ||

| 40 | 1.66 | 3.06 | ||||

| 41 | 3.55 | |||||

| 42 | 2.62 | |||||

| 43 | 2.00 | |||||

| 44 | 3.00 | 1 | ||||

| 45 | 3.00 | |||||

| 46 | 3.00 | |||||

| 47 | 3.00 | |||||

| 48 | 3.00 | 1 | ||||

| 49 | 2.62 | 2 | ||||

| 50 | 2.00 | |||||

| 51 | 2.00 | 1 | ||||

| 52 | 2.00 | |||||

| 53 | 1.60 | |||||

| 54 | 1.00 | |||||

| 55 | 1.00 | |||||

| 56 | 1.00 | |||||

| 57 | 0.92 |

Table 4.

The sample of individual female risk years and infants by study community

| Kasekela | Mitumba | Kanyawara | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Risk years | Infants | Risk years | Infants | Risk years | Infants |

| 9 | 18.00 | 1.00 | 16.04 | |||

| 10 | 17.73 | 1 | 1.00 | 14.06 | ||

| 11 | 15.09 | 1 | 1.46 | 10.41 | 1 | |

| 12 | 17.70 | 2 | 1.06 | 8.43 | ||

| 13 | 20.57 | 2 | 2.00 | 16.57 | 1 | |

| 14 | 21.41 | 4 | 2.00 | 16.45 | 3 | |

| 15 | 20.56 | 3 | 2.50 | 14.82 | 6 | |

| 16 | 19.38 | 6 | 2.62 | 1 | 13.30 | 2 |

| 17 | 21.11 | 1 | 2.50 | 13.96 | 2 | |

| 18 | 22.50 | 2 | 3.12 | 14.01 | 2 | |

| 19 | 22.82 | 1 | 4.66 | 2 | 14.00 | 4 |

| 20 | 19.51 | 4 | 5.50 | 12.08 | 1 | |

| 21 | 18.13 | 4 | 4.50 | 1 | 12.26 | 5 |

| 22 | 18.58 | 2 | 4.00 | 1 | 10.46 | |

| 23 | 16.69 | 4.50 | 1 | 9.48 | 1 | |

| 24 | 13.85 | 2 | 4.96 | 1 | 9.04 | 4 |

| 25 | 11.59 | 4.00 | 8.51 | |||

| 26 | 11.04 | 2 | 4.00 | 1 | 7.27 | 1 |

| 27 | 11.00 | 3 | 3.88 | 1 | 8.44 | 3 |

| 28 | 10.50 | 2 | 2.34 | 10.00 | 2 | |

| 29 | 11.36 | 1.00 | 10.00 | 1 | ||

| 30 | 12.50 | 1 | 1.47 | 1 | 9.47 | 1 |

| 31 | 12.26 | 2.00 | 9.00 | |||

| 32 | 11.91 | 4 | 1.50 | 1 | 7.59 | 2 |

| 33 | 12.20 | 1 | 1.00 | 5.15 | 1 | |

| 34 | 10.85 | 1 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1 | |

| 35 | 9.00 | 1.00 | 4.19 | 2 | ||

| 36 | 9.00 | 1.00 | 3.88 | |||

| 37 | 9.00 | 2 | 1.00 | 3.56 | 1 | |

| 38 | 8.25 | 1 | 1.50 | 1 | 3.00 | |

| 39 | 5.88 | 1 | 1.53 | 3.00 | ||

| 40 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 3.17 | |||

| 41 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | |||

| 42 | 3.12 | 1 | 1.00 | 4.07 | 1 | |

| 43 | 3.00 | 1 | 1.00 | 4.55 | ||

| 44 | 2.25 | 0.94 | 3.00 | |||

| 45 | 2.00 | 3.00 | ||||

| 46 | 1.17 | 3.00 | ||||

| 47 | 1.00 | 2.55 | ||||

| 48 | 1.00 | 2.00 | ||||

| 49 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 1 | |||

| 50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 51 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 52 | 1.00 | 1.11 | ||||

| 53 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 54 | 0.50 | 1.46 | 1 | |||

| 55 | 1.96 | |||||

| 56 | 1.00 | |||||

| 57 | 1.00 | |||||

| 58 | 1.00 | |||||

| 59 | 1.00 | |||||

| 60 | 1.00 | |||||

| 61 | 1.00 | |||||

| 62 | 1.00 | |||||

| 63 | 0.57 |

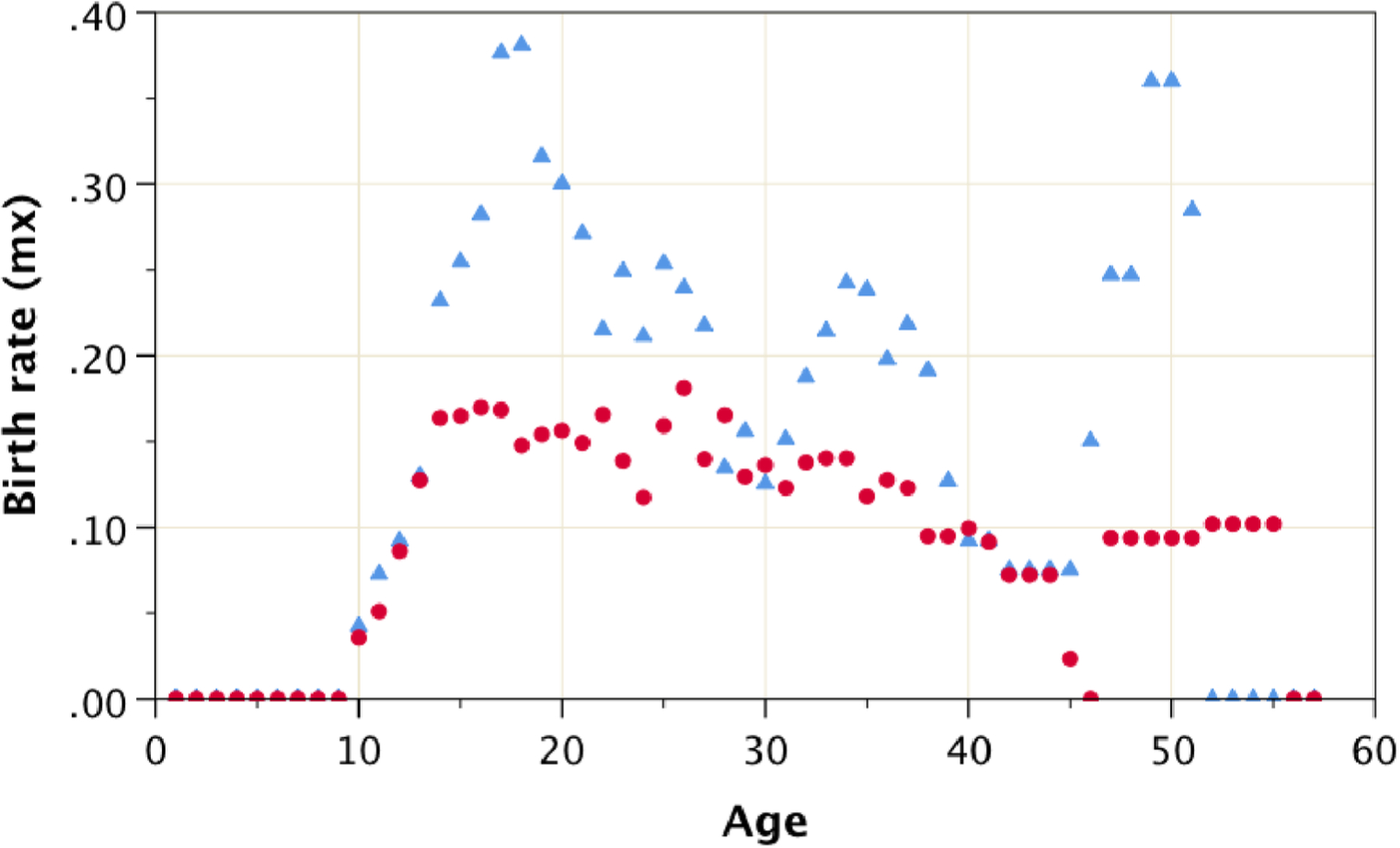

Five-year running averages of male and female age-specific fertility (mx) from the combined, three-community sample are illustrated in Figure 1 (from data in Tables 5 and 6). Contrary to our prediction, male chimpanzees did not start reproducing later than females. Whereas the earliest age of female conception was 11 (at Gombe) or 12 (at Kanyawara), the youngest fathers were 10 (at Kanyawara) or 11 (at Gombe). Initial increases in age-specific fertility appeared similar between the sexes. Males took longer to reach their maximum fertility rate, however, which was higher than that of females.

Figure 1.

Age-specific fertility (mx5yr) from the life table for male (triangles) and female (circles) chimpanzees in the pooled Gombe/Kanyawara sample (5-year running averages). Calculations use parental age at conception, rather than birth, and exclude infants that did not live to 1 year.

Table 5.

Male age-specific fertility from the combined, three-site sample

| Male age | Risk years | Infants sired | Ungenotyped infants | mx | mx5yra | lx | lx*mx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 36.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.545 | 0 | |

| 10 | 35.58 | 1 | 0.128 | 0.032 | 0.042 | 0.528 | 0.017 |

| 11 | 28.91 | 2 | 0.346 | 0.081 | 0.073 | 0.502 | 0.041 |

| 12 | 23.95 | 2 | 0.346 | 0.098 | 0.092 | 0.478 | 0.047 |

| 13 | 23.16 | 3 | 0.563 | 0.154 | 0.130 | 0.460 | 0.071 |

| 14 | 24.60 | 2 | 0.346 | 0.095 | 0.232 | 0.432 | 0.041 |

| 15 | 22.00 | 4 | 0.870 | 0.221 | 0.255 | 0.404 | 0.089 |

| 16 | 20.12 | 10 | 1.889 | 0.591 | 0.282 | 0.394 | 0.233 |

| 17 | 22.85 | 4 | 0.870 | 0.213 | 0.377 | 0.394 | 0.084 |

| 18 | 20.48 | 5 | 0.946 | 0.290 | 0.381 | 0.386 | 0.112 |

| 19 | 20.75 | 10 | 1.765 | 0.567 | 0.316 | 0.368 | 0.209 |

| 20 | 19.51 | 4 | 0.763 | 0.244 | 0.300 | 0.368 | 0.090 |

| 21 | 17.70 | 4 | 0.691 | 0.265 | 0.271 | 0.349 | 0.093 |

| 22 | 17.88 | 2 | 0.417 | 0.135 | 0.215 | 0.340 | 0.046 |

| 23 | 16.15 | 2 | 0.346 | 0.145 | 0.249 | 0.340 | 0.049 |

| 24 | 17.02 | 4 | 0.870 | 0.286 | 0.212 | 0.340 | 0.097 |

| 25 | 16.99 | 6 | 1.037 | 0.414 | 0.254 | 0.331 | 0.137 |

| 26 | 17.24 | 1 | 0.328 | 0.077 | 0.239 | 0.315 | 0.024 |

| 27 | 16.45 | 5 | 0.691 | 0.346 | 0.218 | 0.300 | 0.104 |

| 28 | 15.25 | 1 | 0.128 | 0.074 | 0.135 | 0.284 | 0.021 |

| 29 | 13.26 | 2 | 0.346 | 0.177 | 0.156 | 0.252 | 0.045 |

| 30 | 13.12 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.126 | 0.238 | 0.000 |

| 31 | 13.30 | 2 | 0.435 | 0.183 | 0.151 | 0.223 | 0.041 |

| 32 | 12.77 | 2 | 0.474 | 0.194 | 0.188 | 0.200 | 0.039 |

| 33 | 11.15 | 2 | 0.256 | 0.202 | 0.215 | 0.177 | 0.036 |

| 34 | 9.33 | 3 | 0.346 | 0.359 | 0.242 | 0.155 | 0.056 |

| 35 | 9.03 | 1 | 0.217 | 0.135 | 0.238 | 0.134 | 0.018 |

| 36 | 7.00 | 2 | 0.256 | 0.322 | 0.198 | 0.120 | 0.039 |

| 37 | 7.00 | 1 | 0.217 | 0.174 | 0.218 | 0.105 | 0.018 |

| 38 | 7.12 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.191 | 0.098 | 0.000 |

| 39 | 7.54 | 3 | 0.474 | 0.461 | 0.127 | 0.083 | 0.038 |

| 40 | 4.72 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.092 | 0.068 | 0.000 |

| 41 | 3.55 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.092 | 0.048 | 0.000 |

| 42 | 2.62 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.075 | 0.041 | 0.000 |

| 43 | 2.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.075 | 0.041 | 0.000 |

| 44 | 3.00 | 1 | 0.128 | 0.376 | 0.075 | 0.033 | 0.012 |

| 45 | 3.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.075 | 0.033 | 0.000 |

| 46 | 3.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.150 | 0.033 | 0.000 |

| 47 | 3.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.247 | 0.022 | 0.000 |

| 48 | 3.00 | 1 | 0.128 | 0.376 | 0.247 | 0.022 | 0.008 |

| 49 | 2.62 | 2 | 0.256 | 0.860 | 0.360 | 0.022 | 0.019 |

| 50 | 2.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.360 | 0.022 | 0.000 |

| 51 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.128 | 0.564 | 0.285 | 0.022 | 0.012 |

| 52 | 2.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.000 | |

| 53 | 1.60 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.000 |

mx5yr indicates a 5-year running average of age-specific fertility (mx). “Infants sired” includes only infants that survived to 1 year.

Table 6.

Female age-specific fertility from the combined, three-site sample

| Female age | Risk years | Infants | mx | mx5yra | lx | lx*mx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 35.04 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.544 | 0.000 | |

| 10 | 32.79 | 1 | 0.030 | 0.036 | 0.536 | 0.016 |

| 11 | 26.96 | 2 | 0.074 | 0.051 | 0.527 | 0.039 |

| 12 | 27.19 | 2 | 0.074 | 0.086 | 0.519 | 0.038 |

| 13 | 39.14 | 3 | 0.077 | 0.128 | 0.498 | 0.038 |

| 14 | 39.86 | 7 | 0.176 | 0.164 | 0.491 | 0.086 |

| 15 | 37.88 | 9 | 0.238 | 0.165 | 0.485 | 0.115 |

| 16 | 35.30 | 9 | 0.255 | 0.170 | 0.478 | 0.122 |

| 17 | 37.57 | 3 | 0.080 | 0.168 | 0.478 | 0.038 |

| 18 | 39.63 | 4 | 0.101 | 0.148 | 0.472 | 0.048 |

| 19 | 41.48 | 7 | 0.169 | 0.154 | 0.465 | 0.078 |

| 20 | 37.09 | 5 | 0.135 | 0.156 | 0.458 | 0.062 |

| 21 | 34.89 | 10 | 0.287 | 0.149 | 0.444 | 0.127 |

| 22 | 33.04 | 3 | 0.091 | 0.166 | 0.437 | 0.040 |

| 23 | 30.67 | 2 | 0.065 | 0.139 | 0.429 | 0.028 |

| 24 | 27.85 | 7 | 0.251 | 0.117 | 0.429 | 0.108 |

| 25 | 24.10 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.159 | 0.398 | 0.000 |

| 26 | 22.31 | 4 | 0.179 | 0.181 | 0.398 | 0.071 |

| 27 | 23.32 | 7 | 0.300 | 0.140 | 0.390 | 0.117 |

| 28 | 22.84 | 4 | 0.175 | 0.165 | 0.367 | 0.064 |

| 29 | 22.36 | 1 | 0.045 | 0.130 | 0.359 | 0.016 |

| 30 | 23.44 | 3 | 0.128 | 0.136 | 0.343 | 0.044 |

| 31 | 23.26 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.123 | 0.317 | 0.000 |

| 32 | 21.00 | 7 | 0.333 | 0.138 | 0.299 | 0.100 |

| 33 | 18.35 | 2 | 0.109 | 0.140 | 0.266 | 0.029 |

| 34 | 16.85 | 2 | 0.119 | 0.140 | 0.248 | 0.029 |

| 35 | 14.19 | 2 | 0.141 | 0.118 | 0.222 | 0.031 |

| 36 | 13.88 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.128 | 0.213 | 0.000 |

| 37 | 13.56 | 3 | 0.221 | 0.123 | 0.194 | 0.043 |

| 38 | 12.75 | 2 | 0.157 | 0.095 | 0.185 | 0.029 |

| 39 | 10.41 | 1 | 0.096 | 0.095 | 0.168 | 0.016 |

| 40 | 8.17 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.099 | 0.143 | 0.000 |

| 41 | 8.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.091 | 0.143 | 0.000 |

| 42 | 8.19 | 2 | 0.244 | 0.072 | 0.132 | 0.032 |

| 43 | 8.55 | 1 | 0.117 | 0.072 | 0.120 | 0.014 |

| 44 | 6.19 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.072 | 0.109 | 0.000 |

| 45 | 5.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.023 | 0.087 | 0.000 |

| 46 | 4.17 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.076 | 0.000 |

| 47 | 3.55 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.094 | 0.067 | 0.000 |

| 48 | 3.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.094 | 0.057 | 0.000 |

| 49 | 2.13 | 1 | 0.469 | 0.094 | 0.057 | 0.027 |

| 50 | 2.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.094 | 0.048 | 0.000 |

| 51 | 2.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.094 | 0.048 | 0.000 |

| 52 | 2.11 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.102 | 0.048 | 0.000 |

| 53 | 2.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.102 | 0.036 | 0.000 |

| 54 | 1.96 | 1 | 0.510 | 0.102 | 0.024 | 0.012 |

| 55 | 1.96 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.102 | 0.024 | 0.000 |

| 56 | 1.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.024 | 0.000 | |

| 57 | 1.00 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.024 | 0.000 |

mx5yr indicates a 5-year running average of age-specific fertility (mx).

“Infants” includes only infants that survived to 1 year.

Consistent with our predictions, males showed a pronounced peak in age-specific fertility during young adulthood, followed by a substantial decline with age (Fig. 1). Females achieved an earlier, lower peak in fertility than males, followed by a shallower decline with age. Male age-specific fertility appeared to recover in the mid- to late forties. This rise must be interpreted cautiously, because only 1–3 risk years were available for each age over 40, and only 5 of the 95 genotyped infants were sired by males older than 40. However, males in the sample who lived to these advanced ages continued to successfully produce offspring.

Our Bayesian model of age-specific fertility performed considerably better than the common quadratic model for each sex, based on the DIC (Table 7, Supplemental Online Material (SOM) Fig. S1). However, when we divided the dataset by study site, we found that the null model performed almost equally well for the females in Gombe and the males in Kibale (Table 8). Nonetheless, our models still performed better in all cases (and converged appropriately: Rhat values, SOM Table S1).

Table 7.

Deviance information criterion (DIC) calculated from the Bayesian models for inference on age-specific fertility for the pooled samples of females and males.

The null model corresponds to the commonly used quadratic model, while the alternative is the model in Eq. (1). The model with lowest DIC is highlighted with boldface values.

Table 8.

Deviance information criterion (DIC) calculated from the Bayesian models for inference on age-specific fertility between the two communities (i.e. Kibale and Gombe) for females and males.

| Sex | Community | Null mod.a | Model Eq. (1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Kibale | 295.29 | 290.86 |

| Gombe | 423.78 | 422.69 | |

| Males | Kibale | 252.10 | 251.39 |

| Gombe | 375.32 | 367.25 |

The null model corresponds to the commonly used quadratic model, while the alternative is the model in Eq. (1). The model with lowest DIC is highlighted with boldface values.

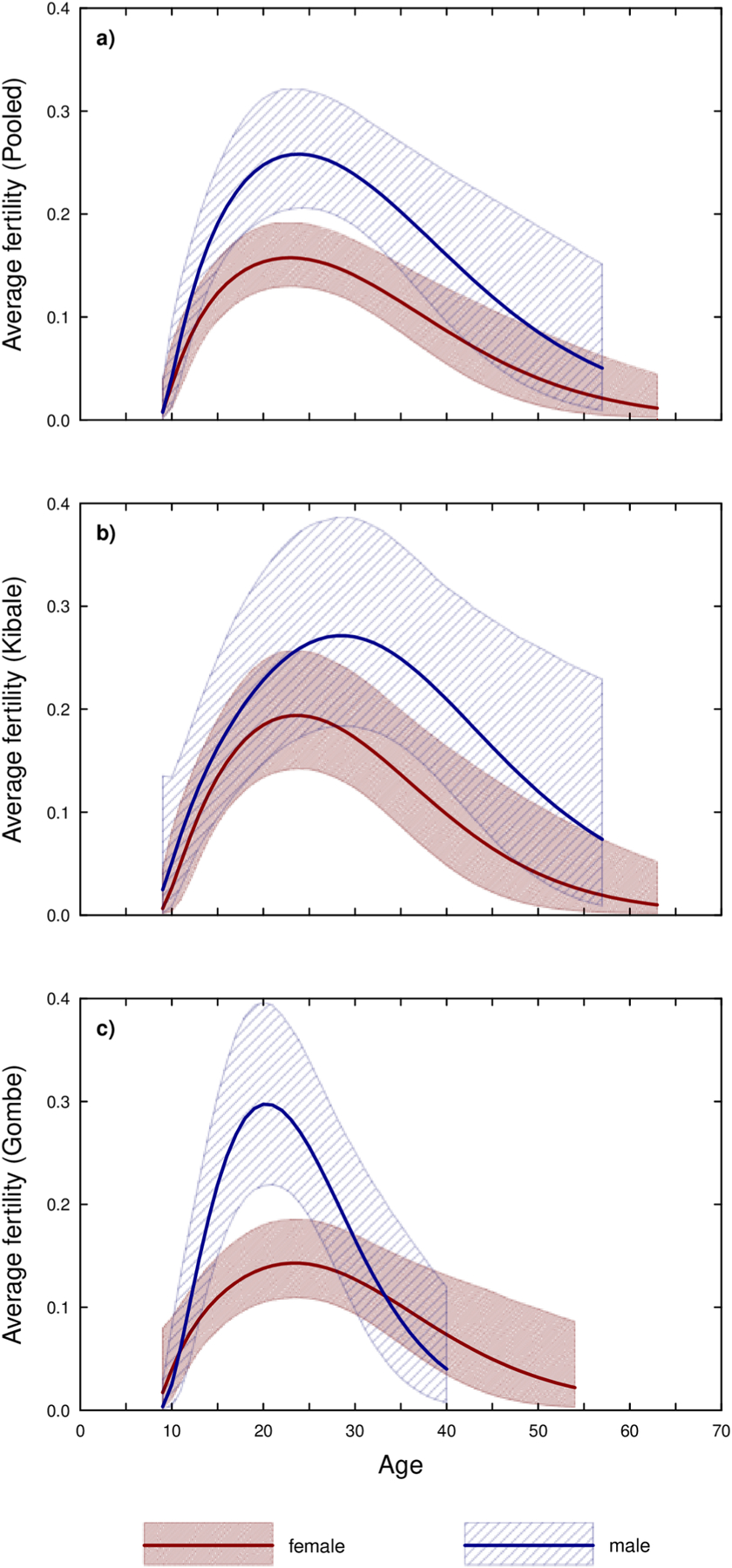

The formal model corroborated the results from the life table calculations discussed previously (Fig. 2). When observations from the three study communities were pooled, females reached their maximum mean fertility at 22.82, one year earlier than males (Table 9 and Fig. 2a). Maximum mean male fertility was 64% higher than maximum mean female fertility, and females showed a shallower decline with age. Uncertainty around the male fertility estimate increased at older ages, as the sample size decreased.

Figure 2.

Estimated average age-specific fertility for males and females, where the polygons outline the 95% credible intervals while the internal lines show the average estimates. Panel a) shows the results for both communities pooled, b) shows only the results for Kanyawara, and c) the results for Gombe.

Table 9:

Age at maximum average fertility, and maximum average fertility per sex, when both communities are pooled together (*) and when each community is analyzed separately.a

| Variable | Sex | Community | Mean | SE | 2.50% | 97.50% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both* | 22.82 | 1.77 | 19.76 | 26.66 | ||

| Age at maximum average fertility | Females | Kibale | 23.57 | 2.16 | 19.81 | 28.34 |

| Gombe | 23.29 | 2.71 | 18.8 | 28.65 | ||

| Both* | 23.96 | 2.18 | 20.47 | 28.97 | ||

| Males | Kibale | 28.49 | 4.19 | 21.80 | 36.61 | |

| Gombe | 20.32 | 1.30 | 18.06 | 23.12 | ||

| Both* | 0.159 | 0.015 | 0.13 | 0.190 | ||

| Maximum average fertility | Females | Kibale | 0.197 | 0.028 | 0.145 | 0.255 |

| Gombe | 0.145 | 0.020 | 0.110 | 0.184 | ||

| Both* | 0.261 | 0.028 | 0.209 | 0.318 | ||

| Males | Kibale | 0.277 | 0.052 | 0.187 | 0.384 | |

| Gombe | 0.301 | 0.043 | 0.225 | 0.392 |

We provide the mean estimate, the standard error (SE) and the lower and upper 95% credible intervals.

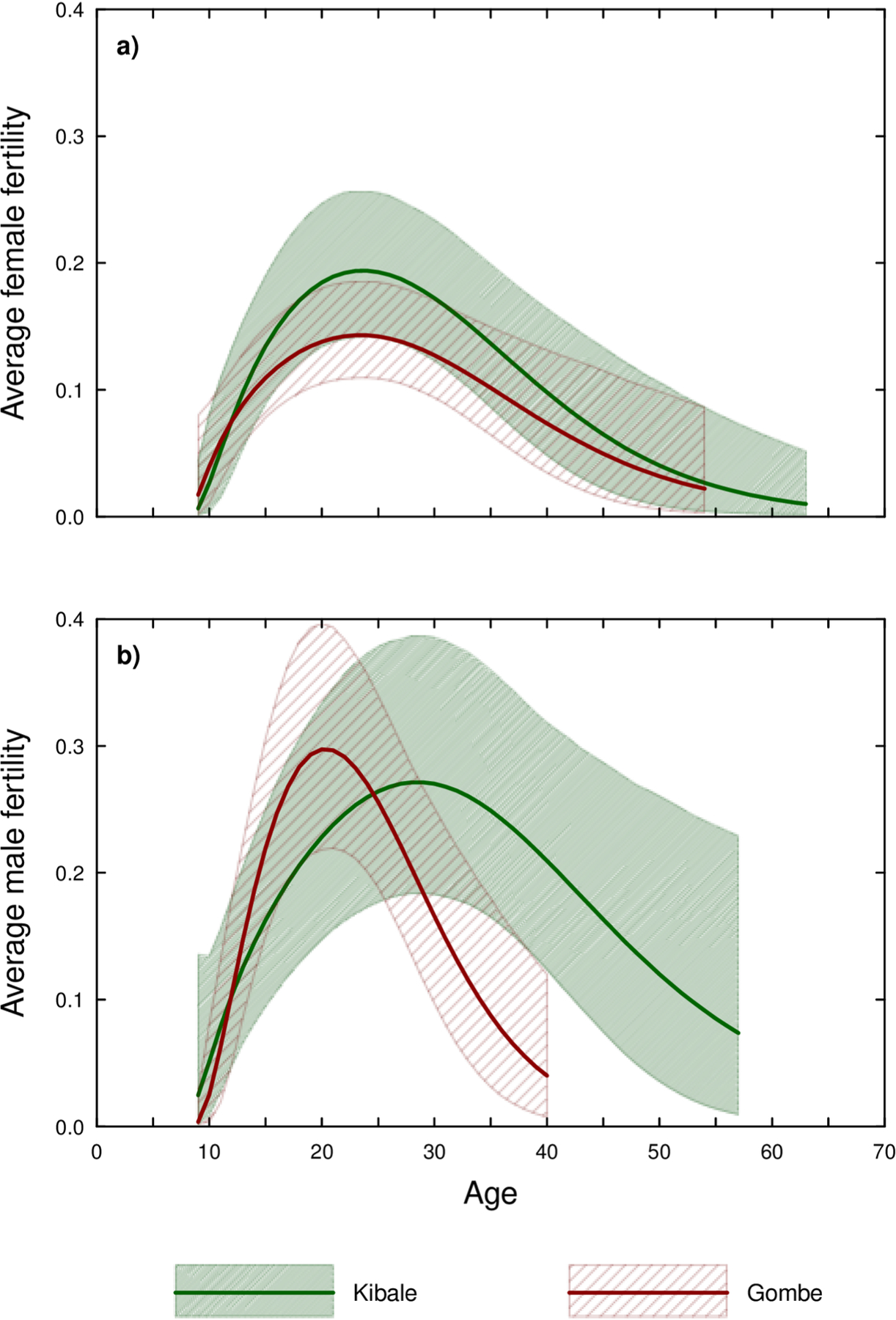

The fact that every father over 40 was from Kanyawara suggested that male age-specific fertility differed between the study sites. Consistent with this idea, the average age of fathers at Kanyawara was 27.5 (SD=11.3, n=39 conceptions), but at Gombe (Mitumba and Kasekela combined) 21.6 (SD= 6.5, n=56 conceptions) (Mann Whitney U, Z=−2.53, p=0.011). When data from the two sites were modeled separately, the age of maximum fertility for males differed markedly: 20.3 years in Gombe versus 28.5 years in Kanyawara (Table 9 and Fig. 2b). Females, by contrast, reached maximum fertility at 23 years in both sites (Fig. 2c). Consequently, Kanyawara females were estimated to attain maximum mean fertility 4.9 years before Kanyawara males, whereas males in Gombe actually attained maximum mean fertility 3 years before females. Maximum mean fertility was estimated to be similar between males at the two study sites, with Gombe just 9% higher than Kanyawara (Fig. 3a). By contrast, maximum mean female fertility was 36% higher in Kanyawara than Gombe (Table 9, Fig. 3b), a difference that can be attributed to higher rates of infant mortality at Gombe during the first year.

Figure 3.

Estimated average age-specific fecundity for Kanyawara and Gombe (3a) males and (3b) females. The polygons outline the 95% credible intervals while the internal lines show the average estimates.

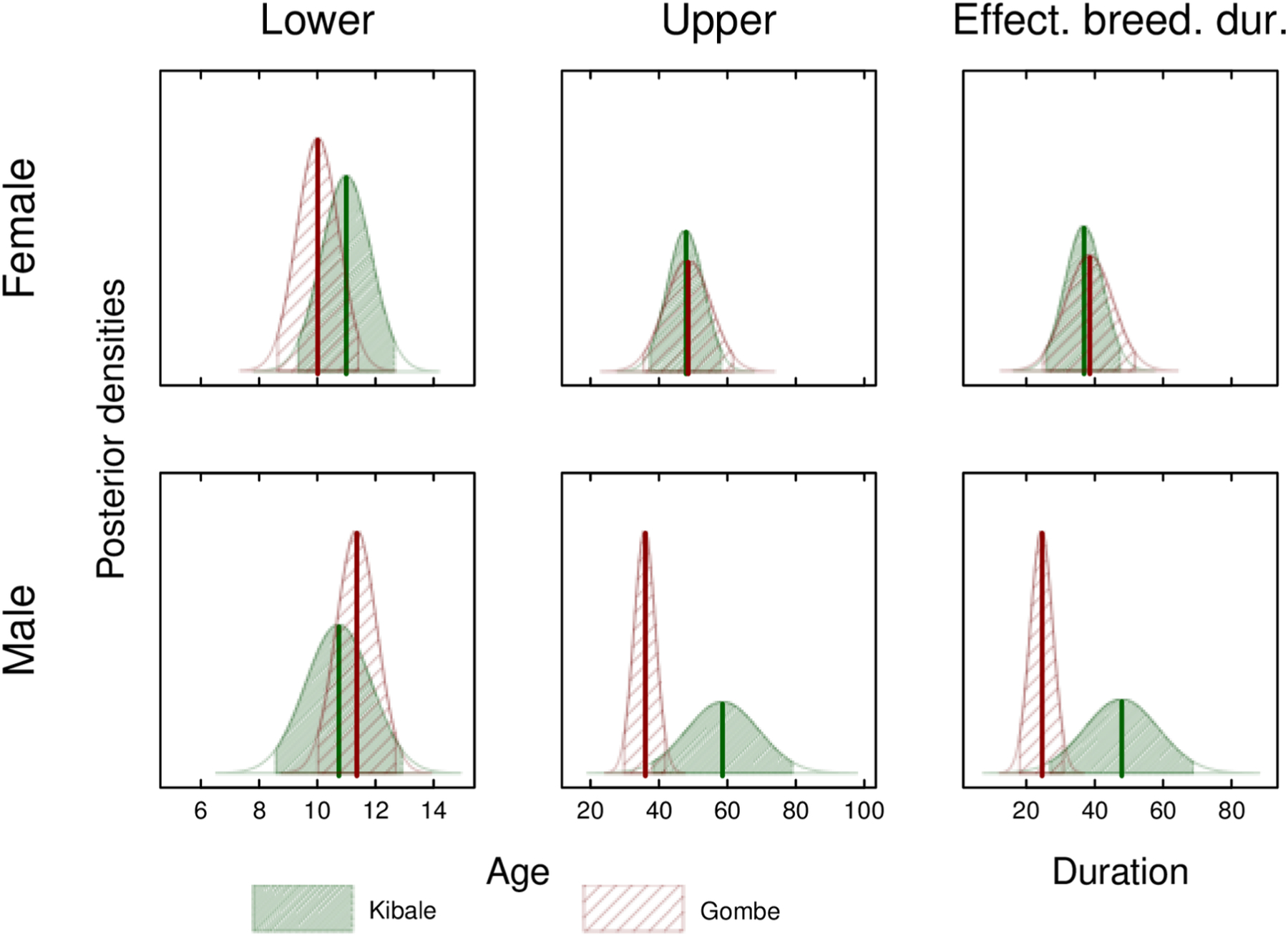

Consistent with our predictions, the sex difference in duration of effective breeding for chimpanzees was less than that seen in primates with higher levels of body mass dimorphism, such as baboons and mandrills. Using Clutton-Brock and Isvaran’s (2007) quadratic method, the male/female duration of effective breeding was 0.94 for the pooled sample. When the two study sites were considered separately, the male/female duration of effective breeding was 0.90 at Gombe and 0.95 at Kanyawara. Our Bayesian model produced estimates of male/female duration of effective breeding of 1.05 for the pooled sample, 0.76 for Gombe, and 1.14 for Kanyawara. Confidence intervals around the Kanyawara estimate are very broad, however, because of uncertainty at the upper end of the male estimate (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Posterior densities of the lower and upper bounds of effective breeding and of the effective breeding duration in Kanyawara and Gombe. The top row shows the results for females and the bottom row for males. The filled polygons show the 95% credible intervals.

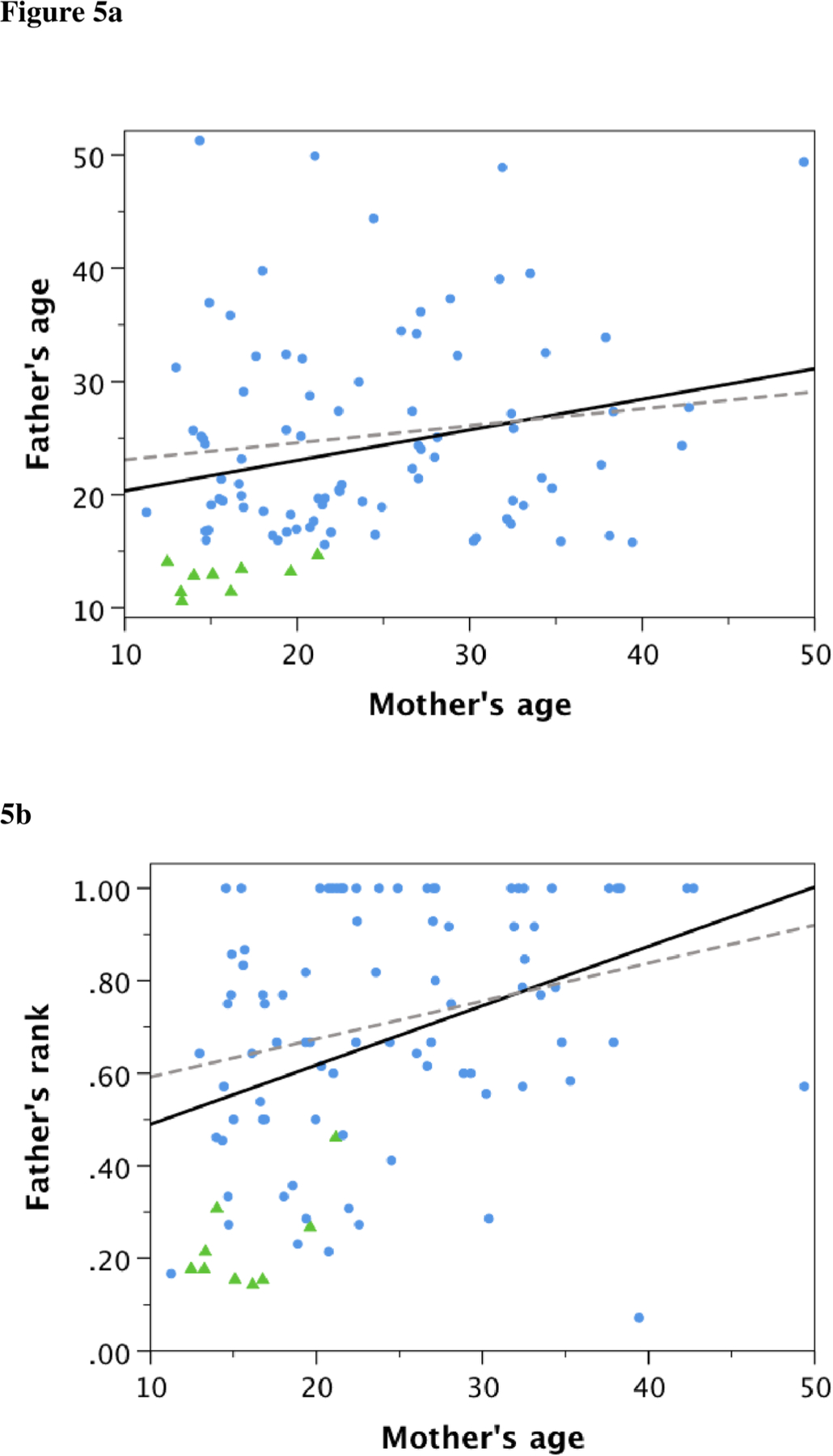

Consistent with the hypothesis that low-ranking, adolescent males focused their mating effort on young females, father’s age was weakly, but positively and significantly, correlated with mother’s age across the entire sample of chimpanzee infants (Spearman rank correlation, rS=0.237, n=95, p=0.021). Figure 5a shows that this relationship was driven by conceptions between adolescent males and young females. When only adult fathers (those 15 and over) were considered, the relationship disappeared (rS=0.075, n=86, p=0.495). As in a previous analysis from Gombe that used some of the same data (Wroblewski et al. 2009), father’s rank was positively correlated with mother’s age, both across the entire sample (Spearman rank correlation, rS =0.421, n=95, p<0.0001), and among adult fathers (rS=0.314, n=86, p=0.003). Figure 5b shows that this relationship was driven by low-ranking males siring infants almost exclusively with younger females. Notably, only 2 males in the bottom half of the dominance hierarchy sired offspring with females 25 or older (6.9% of conceptions by such males), whereas precisely half of conceptions among males in the top half of the hierarchy were with females 25 or older.

Figure 5a.

The relationship between father’s age and mother’s age across all infants (solid line: Spearman rank correlation, rS=0.237, n=95, p=0.021) and infants with adult (≥15 years) fathers (broken line: rS=0.075, n=86, p=0.495). Triangles represent infants with adolescent (<15 years) fathers. 5b. The relationship between father’s rank in the male dominance hierarchy and mother’s age across all infants (solid line: rS=0.421, n=95, p<0.0001) and infants with adult (≥15) fathers (broken line: rS=0.314, n=86, p=0.003).

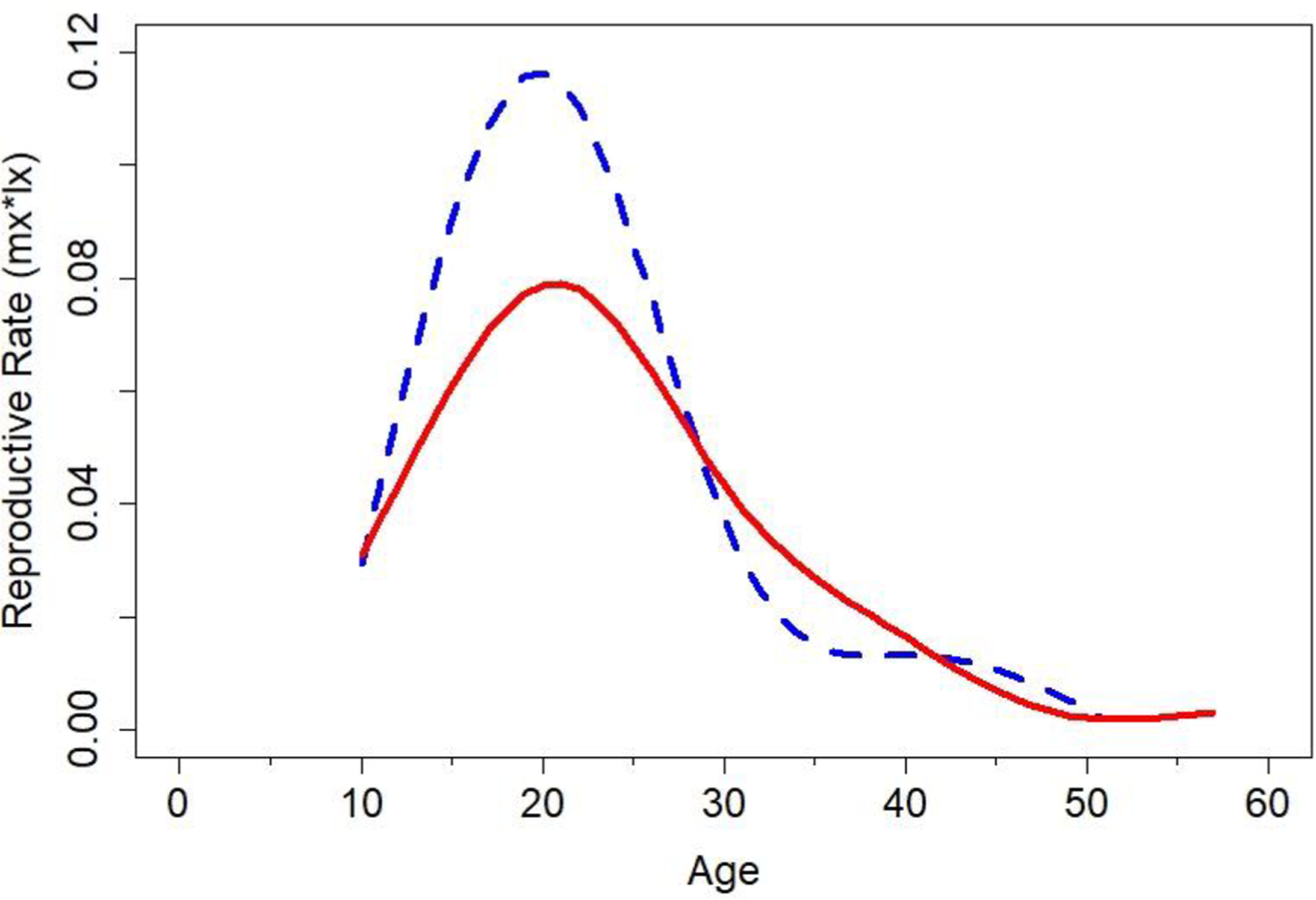

Because few chimpanzee males lived beyond 45, male fertility at older ages had little effect on estimates of lifetime reproduction. This is clear from Figure 6, which plots age-specific reproductive rates (lx*mx: the probability, from birth, of both surviving to a particular age and reproducing at that age) from the life table data for both sexes. Again, males showed an earlier reproductive peak than females, followed by a steeper decline.

Figure 6.

Reproductive rates (mx*lx) for male (broken line) and female (solid line) chimpanzees from the life table data for the combined Gombe/Kanyawara sample. These reflect the probability, from birth, of both living to a particular age and reproducing at that age. Lines were fit with the cubic spline function in R.

Previous studies have demonstrated that age-specific mortality rates are higher in Gombe than Kanyawara (Muller and Wrangham, 2014; Bronikowski et al., 2016). For example, a Kanyawara male who reached age 15 was expected to live for an additional 25 years, whereas a Gombe male at the same age was expected to live for an additional 15 years. Consequently, life table data on male age-specific reproductive rates (lx*mx) suggest that net fertility for males was higher in Kanyawara (2.3) than in Gombe (1.9).

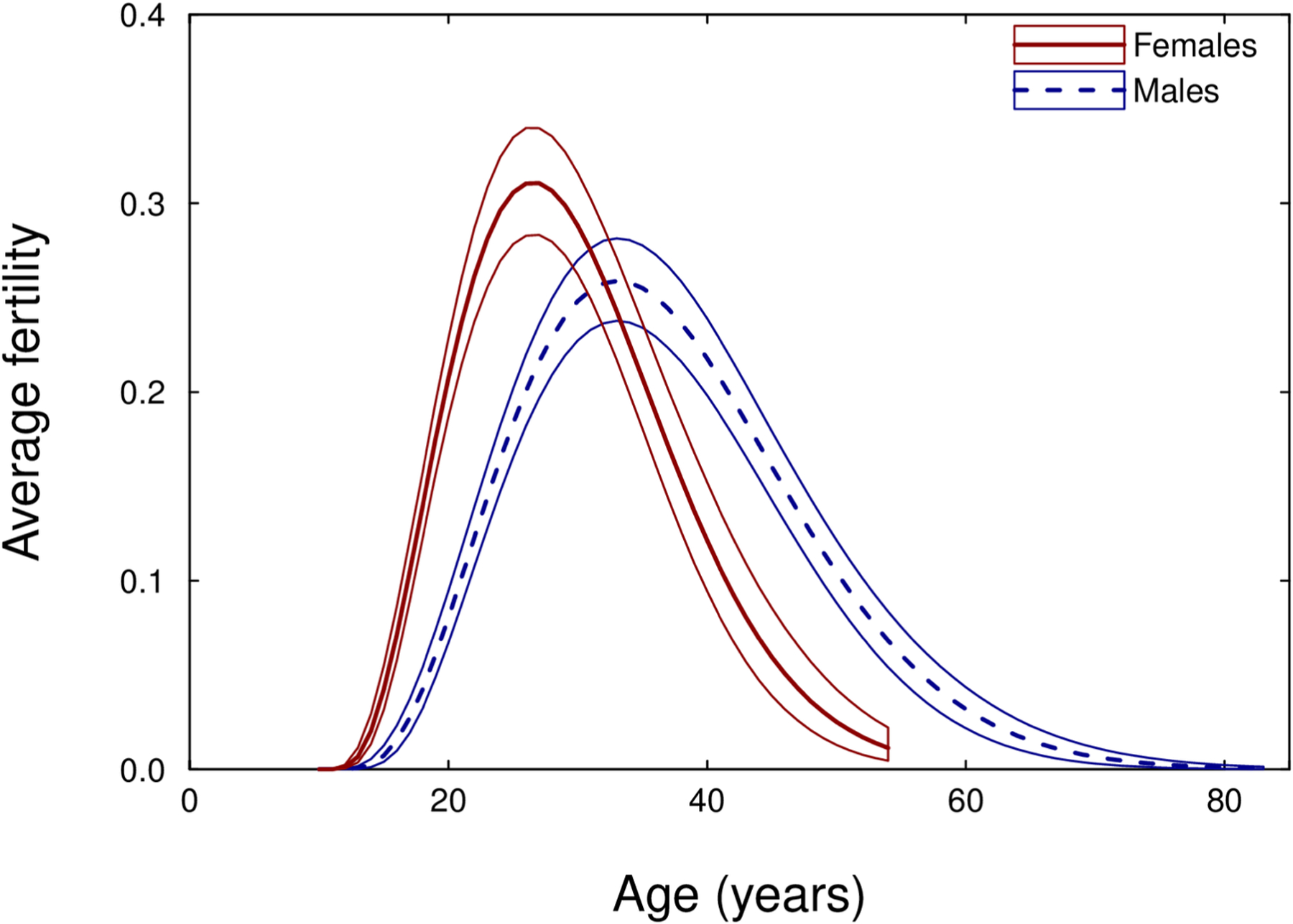

Figure 7 plots sex differences in human age-specific fertility for Hadza foragers. Like the chimpanzee fertility models, the human model converged appropriately (Rhat values, Table S1), and performed better than the common quadratic model based on the DIC (Table 10). Hadza men’s and women’s fertility curves show a different pattern of dimorphism than do those of male and female chimpanzees. As expected, Hadza men showed less of a peak in fertility during young adulthood than did chimpanzee males. However, young Hadza men showed a substantial delay in reproduction compared to Hadza women that was not observed in chimpanzees. Specifically, Hadza men reached average maximum fertility at age 33, 6.5 years later than women, despite women’s maximum average fertility being 20% higher. Men also continued to reproduce into old age, meaning that their fertility curve was shifted several years to the right of the women’s curve, with a longer tail. Because women ceased reproduction in the mid to late forties, they maintained a shorter duration of effective breeding than men. The estimate of male/female duration of effective breeding from our Bayesian model was 1.3, the same as that reported by Blurton Jones (2016) from a quadratic model.

Figure 7.

Estimated average age-specific fertility for Hadza women (solid line) and men (broken line). Polygons outline the 95% credible intervals, while the internal lines show the average estimates.

Table 10.

Deviance information criterion (DIC) calculated from the Bayesian models for inference on Hazda female and male age-specific fertility.

The null model corresponds to the commonly used quadratic model, while the alternative is the model in Eq. (1). The model with lowest DIC is highlighted with boldface values.

4.0. Discussion

As expected, chimpanzees exhibited a sex difference in age-specific fertility, whether the data were pooled or analyzed separately by study site. Males attained a higher maximum fertility than females, followed by a steeper decline with age. This is consistent with the idea that intense, aggressive contest competition favors males in their prime, whereas senescence has weaker effects on female reproduction. This sex difference was stronger in Gombe than in Kanyawara, however, owing to more old Kanyawara males fathering offspring.

Contrary to our prediction, male chimpanzees did not show a delay in first reproduction compared to females. In both Kasekela and Kanyawara, 10–11 year old males fathered offspring. Males in this age range are still growing, so they are not yet physically adults (Pusey et al., 2005). Their relationships with mature individuals of both sexes indicate that they are not yet socially adults (Watts and Pusey, 1993). How did these young, low-ranking males successfully compete for mating opportunities, despite lacking adult body size and musculature?

As suggested by previous studies (Muller et al., 2006; Watts, 2015; Wroblewski et al., 2009), adolescent males appeared to focus their reproductive efforts on young females. In our observations, 9 of 95 genotyped infants were sired by males younger than 15. Tellingly, none was sired with a multiparous mother. By contrast, adult males sired 62% of their infants (53 of 86) with multiparous females. Thus, adolescent males were more likely to conceive with nulliparous or primiparous females, whom adults showed less interest in monopolizing (adolescents sired 56% of their infants (5/9) with nulliparous females, and 44% (4/9) with primiparous females). A similar dynamic has been noted in wild orangutans (Pongo spp.), with subordinate, unflanged males more commonly fathering offspring with nulliparous females, who receive less interest from dominant, flanged males (Banes et al., 2015; Utami Atmoko et al., 2009).

It is not currently clear why males prefer older, multiparous mothers (Muller et al., 2006). However, at Kanyawara older mothers experience fewer cycles per conception than do younger mothers or nulliparous females (Wrangham, 2002; Kibale Chimpanzee Project, unpublished data). Consequently, any single mating opportunity with an older mother should be more valuable (i.e. more likely to result in conception). For adult males, the opportunity costs of monitoring and mate-guarding nulliparous females over multiple cycles may be deterrent.

Although male reproduction peaked in the twenties, the few males who reached their mid- to late forties continued to sire offspring, and primarily with multiparous females (80% of conceptions). Elderly males are usually low ranking, so what accounted for their success?

One possibility is that old males compensated for their declining condition by making more effective use of coalitions. At Mahale, for example, Nishida and Hosaka (1996) observed that old males tended to strongly support the alpha male when he was challenged. This “winner support” strategy appeared to be a low-risk way for old males to ingratiate themselves with a more powerful ally. Evidence from both Kibale and Gombe suggests that, in return, alphas concede mating opportunities to the males who most consistently groom and support them (Bray et al., 2016; Duffy et al., 2007). Alternatively, it is possible that only high-quality males live to advanced ages (Brooks and Kemp, 2001). Such males may either be preferred by females, or more successful at coercing females, even if they are no longer competitive with other males.

In the present study, only three males older than 40 sired offspring that lived to one year. All were from Kanyawara: TU (2 infants), ST (2 infants) and BB (1 infant). Supporting the idea that old males preferentially rely on coalitions for mating access, a detailed study of political alliances in Kanyawara found that these three males showed the highest rates of support for the alpha male when he was challenged, groomed the alpha male at the highest rates, and were the least likely to have their mating attempts interrupted by the alpha male, resulting in comparatively high rates of mating with parous females (Duffy, 2006; Duffy et al., 2007).

By contrast, evidence that these old males were particularly successful in attracting or coercing females is scant. For example, Muller and colleagues (2011) examined which Kanyawara males were preferentially solicited by females for copulation during the fertile (periovulatory) period. In that study, one of these old males, TU, was conspicuous as a target of female approaches. However, both BB and ST fell below the mean for adult males. More generally, researchers in both Mahale (Nishida, 1997) and Taï (Stumpf and Boesch, 2005) have reported that females were most likely to avoid or resist the mating advances of very old males. Detailed work on coalitions and alliances at Kanyawara is currently underway that should better establish whether these are especially important for aging males.

Because both young and old males reproduced, the sex difference in duration of effective breeding for chimpanzees was, as predicted, less pronounced than in more sexually dimorphic primates, such as mandrills and baboons. This sex difference varied between Gombe and Kanyawara, however. In our Bayesian models, Gombe males were estimated to have a duration of effective breeding 76% that of females, whereas the estimate for Kanyawara males was slightly above that of females. As previously noted, this discrepancy is explained by the fact that more old males successfully sired offspring in Kanyawara than in Gombe. The Gombe estimate is much more precise, as the small number of male risk years at later ages in Kanyawara produced wide confidence intervals around the upper limit. Nevertheless, estimates for both the upper limit and the duration of effective breeding at Gombe fall outside of the 95% confidence interval for the estimates at Kanyawara.

Previous studies have shown that mortality rates are higher in Gombe than Kanyawara, partly because Gombe chimpanzees maintain a high prevalence of SIVcpz infection (Keele 2009). High mortality reduces the number of Gombe males in the oldest age categories (Bronikowski et al., 2016; Muller and Wrangham, 2014), which may partly explain their earlier peak in fertility. It is also possible that the elevated mortality risk compels Gombe males to invest more intensely in reproduction at younger ages (Promislow and Harvey, 1990). Combining mortality and fertility rates, Kanyawara males were estimated to have higher average lifetime reproductive success than Gombe males. This finding is consistent with long-term observations showing overall population decline in Gombe, and modest growth in Kanyawara (Bronikowksi et al., 2016; Muller and Wrangham, 2014).

Finally, chimpanzees showed a pattern of sexual dimorphism in age-specific fertility distinct from that of human foragers. The birth rate for male chimpanzees peaked during young adulthood, rising well above the female rate before markedly declining. No such peak was evident for Hadza men, whose maximal fertility rate was actually lower than that of Hadza women. This discrepancy might reflect a tighter link between men’s and women’s reproduction, driven by long-term pair bonds (Jaeggi et al., 2017; Kaplan et al., 2010).

However, other aspects of forager age-specific fertility appear more sexually dimorphic than those of chimpanzees. The male/female duration of effective breeding in chimpanzees, for example, was either skewed toward females (Gombe), or close to even (Kanyawara), whereas the Hadza ratio was skewed toward males, at 1.3. Although durations of effective breeding, calculated in this manner, are not available from other foraging populations, it is clear from the data presented by Tuljapurkar and colleagues (2007: e785) that the Ju/’hoansi and the Ache exhibit a male bias similar to that of the Hadza, as do small-scale horticulturalists like the Yanomamö and the Tsimane. In all of these groups this bias results from women experiencing menopause in their mid to late forties, while some old men continue to father children with younger women (see also Hill and Hurtado, 1996; Howell, 2000). Because chimpanzees rarely reach menopause (Emery Thompson et al. 2007), and maintain an adult sex ratio skewed toward females (Wilson et al. 2014), the ratio of fecund females to reproductively active males is higher than in human foragers. Such a bias in the human operational sex ratio likely generates a significant amount of reproductive competition among men (e.g. Coxworth et al., 2015; Loo et al., 2017; Marlowe and Berbesque, 2012).

How do past-prime forager men successfully compete for reproductive opportunities in ways that most male chimpanzees are less able to? Among many foragers, hunting reputation is a strong predictor of men’s fertility, and older men are better hunters (Gurven and von Rueden, 2006; Smith, 2004). Among the Hadza, for example, men who are rated as better hunters are more likely to leave their menopausal spouses for younger women (Blurton Jones, 2016; Marlowe, 2000). Both female choice and male competition appear to be important in linking men’s fertility and hunting reputation. Women prefer better hunters as husbands, and other men are more likely to acknowledge the claims of a high-status hunter on a wife (Blurton Jones et al., 2000; Hawkes et al., 2001; Smith, 2004). The latter point suggests a similarity between humans and chimpanzees in the importance of male coalitions and alliances for the continuing reproductive success of older males.

Human forager data also reveal significant dimorphism in the age at first reproduction that is not evident in chimpanzees. Hadza men, for example, first marry around 7 years later than Hadza women (Blurton Jones, 2016). Similar gaps exist for the Ju/’hoansi (9.8 years: Howell 2005) and the Ache (5 years: Hill and Hurtado 1996). Why do men show a clear delay in age at first reproduction compared to women? As in other primates, this likely reflects some form of male-male competition. In many pastoralist and agricultural societies, men delay marriage as they accumulate the resources (livestock, land, or other wealth) that women seek for successful reproduction (Kaplan et al., 2009). Although foraging societies lack such wealth accumulation, men are sometimes expected to demonstrate successful hunting ability before they are considered eligible for marriage. Among the Ju/’hoansi, for example, young men are not taken seriously as suitors until they have killed their first large animal (Howell, 2000; Lee, 1979). Young males might compete, then, to develop their reputations as skilled hunters, in order to attract wives.

On the other hand, forager men generally start families long before they reach their full potential as hunters (Blurton Jones, 2016; Kaplan et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2002). First marriage for forager men occurs years prior to the age of peak hunting proficiency, instead corresponding with age at peak strength (Muller and Pilbeam, 2017). Consequently, it is likely that violence, or the threat of violence, plays a more significant role in the initiation (or deferment) of forager men’s reproductive careers than is often recognized (ibid.). This was explicit among the pre-contact Ache, where middle-aged men monopolized reproductive-aged women, and “younger men were afraid of ‘fully grown adult men’ because of their strong alliances and the fact that they sometimes killed younger men in club fights” (Hill and Hurtado, 1996: 280). A similar dynamic was described among the Australian Tiwi, where coalitions of older, married men used the threat of violence to constrain the mating efforts of subordinate bachelors (Hart and Pilling, 1960; Rodseth, 2012). As in many male primates, men may require adult musculature to compete successfully with older, more established males, even when the competition is not as conspicuous as that observed among male chimpanzees.

In summary, both humans and chimpanzees showed sexual dimorphism in age-specific fertility that deviated from predictions drawn from primates with more extreme body-size dimorphism. Both species showed evidence for older males continuing to reproduce, despite being less physically formidable than younger males. Older chimpanzee males relied on coalitions to lengthen their reproductive careers, a tactic that has been described in a range of small-scale human societies (Low, 1992; Marlowe, 2000; Rodseth, 2012). These observations are consistent with the idea that coalition building, rather than physical strength alone, became important for male-male competition early in hominin evolution. Despite such competition, adolescent male chimpanzees initiated their reproductive careers at the same age as females, by targeting less desirable, subfecund mates. As a result, sexual dimorphism in chimpanzee age-specific fertility was lower than expected, given the relatively high rate and intensity of male-male aggression in this species (for similar results with canine dimorphism see Plavcan et al., 1995). By contrast, forager men show a substantial delay in reproduction compared to women, yet still maintain a longer duration of effective breeding, owing to women’s menopause. Consequently, the human adult sex ratio (number of fertile males over the number of fertile females) shows a consistent male bias that is not seen in chimpanzees, nor primates generally. This shift in the duration of effective breeding deserves attention, as it has recently been recognized that a male-biased adult sex ratio should select for male mate guarding, one route to the evolution of human pair bonds (e.g. Coxworth et al., 2015; Loo et al., 2017; Rose et al. 2019; Schacht and Bell 2016).

Supplementary Material

Table 11:

Age at maximum average fertility, and maximum average fertility by sex for the Hadza.a

| Variable | Sex | Mean | SE | 2.50% | 97.50% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at maximum average fertility | Females | 26.52 | 0.415 | 25.74 | 27.37 |

| Males | 33.03 | 0.515 | 32.07 | 34.08 | |

| Maximum average fertility | Females | 0.311 | 0.014 | 0.285 | 0.339 |

| Males | 0.260 | 0.011 | 0.238 | 0.281 |

We provide the mean estimate, the standard error (SE) and the lower and upper 95% credible intervals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kris Sabbi for assistance with figures and Kristen Hawkes for comments on the manuscript.

Work at Gombe was supported by the Jane Goodall Institute, the U.S. National Science Foundation (grants DBS-9021946, SBR-9319909, BCS-0452315, and IOS-LTREB-1052693), and the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 AI 120810 and R00 HD057992). We thank Tanzania National Parks, the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute and the Tanzanian Commission for Science and Technology for granting us permission to work on this project in Gombe National Park, the Gombe Stream Research Center staff for data collection, and Dr. Jane Goodall for allowing us to work with the long-term dataset.

Work at Kanyawara was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (grants BCS-0849380, BCS-1355014, IOS-LTREB 1052693, and DGE-0237002), NIH grants AI058715 and R01AG049395, the Leakey Foundation, the National Geographic Society, and the Wenner-Gren Foundation. The Uganda Wildlife Authority, Uganda National Council of Science and Technology, and Makerere University Biological Field Station granted research permission. We thank Emily Otali and Zarin Machanda for field and data management. Gilbert Isabirye-Basuta, John Kasenene, and the late Jerry Lwanga provided support in the field. Daniel Akaruhanga, Seezi Atwijuze, Fred Baguma, the late John Barwogeza, Richard Karamagi, Christopher Katongole, James Kyomuhendo, Francis Mugurusi, the late Donor Muhangyi, the late Christopher Muruuli, Solomon Musana, Japan Musunguzi, Denis Sebugwawo, John Sunday, Peter Tuhairwe, and Wilberforce Tweheyo collected Kanyawara data, with field data entry by Edgar Mugenyi, Christine Abbe, and Jovia Mahoro. Kim Duffy, Carole Hooven, Alain Houle, Katherine Pieta, and Michael Wilson provided additional research oversight.

References

- Albers P, De Vries H 2001. Elo-rating as a tool in the sequential estimation of dominance strength. Animal Behaviour 61, 489–495. [Google Scholar]

- Alberts SC, Buchan JC, Altmann J 2006. Sexual selection in wild baboons: from mating opportunities to paternity success. Animal Behaviour 72, 1177–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Altmann J, Hausfater J, Altmann SA 1988. Determinants of reproductive success in savannah baboons, Papio cynocephalus In: Clutton-Brock TH (Ed.), Reproductive Success: Studies of Individual Variation in Contrasting Breeding Systems. University of Chicago Press, Chicago: pp. 403–418. [Google Scholar]

- Arandjelovic M, Guschanski K, Schubert G, Harris TR, Thalmann O, Siedel H, Vigilant L 2009. Two-step multiplex polymerase chain reaction improves the speed and accuracy of genotyping using DNA from noninvasive and museum samples. Molecular Ecology Resources 9, 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banes GL, Galdikas BMF, Vigilant L 2015. Male orang-utan bimaturism and reproductive success at Camp Leakey in Tanjung Puting National Park, Indonesia. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 69, 1785–1794. [Google Scholar]

- Blurton Jones N 2016. Demography and Evolutionary Ecology of Hadza Hunter-Gatherers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Blurton Jones NG, Marlowe F, Hawkes K, O’Connell JF 2000. Paternal investment and hunter-gatherer divorce rates In: Cronk L, Chagnon N, Irons W (Eds.), Adaptation and Human Behavior: An Anthropological Perspective. Aldine, New York, pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Blurton Jones NG, Hawkes K, O’Connell JF 2002. Antiquity of postreproductive life: Are there modern impacts on hunter-gatherer postreproductive lifespans? American Journal of Human Biology 14, 184–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesch C, Kohou G, Néné H, Vigilant L 2006. Male competition and paternity in wild chimpanzees of the Taï Forest. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 130, 103–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray J, Pusey AE, Gilby IC 2016. Incomplete control and concessions explain mating skew in male chimpanzees. Proceedings of the Royal Society, B. 283, 20162071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronikowski AM, Cords M, Alberts SC, Altmann J, Brockman DK, Fedigan LM, Pusey A, Stoinski T, Strier KB, Morris WF 2016. Female and male life tables for seven wild primate species. Scientific Data 3, 160006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks R, Kemp DJ 2001. Can older males deliver the good genes? Trends in Ecology and Evolution 16, 308–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WP, Roth RR 2009. Age-specific reproduction and survival of individually marked Wood Thrushes, Hylocichla mustelina. Ecology 90, 218–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caswell H, Weeks DE 1986. Two-sex models: Chaos, extinction, and other dynamic consequences of sex. American Naturalist 128, 707–735. [Google Scholar]

- Chan MH, Hawkes K, Kim PS 2017. Modelling the evolution of traits in a two-sex population, with an application to grandmothering. Journal of Theoretical Biology 393, 145–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock T 2016. Mammal Societies. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, West Sussex, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock TH, Isvaran K 2007. Sex differences in ageing in natural populations of vertebrates. Proceedings of the Royal Society, B. 274, 3097–3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxworth JE, Kim PS, McQueen JS, Hawkes K 2015. Grandmothering life histories and human pair bonding. PNAS 112, 11806–11811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delson E, Terranova CJ, Jungers WL, Sargis EJ, Jablonski NG, Dechow PC 2000. Body mass in Cercopithecidae (Primates, Mammalia): Estimation and scaling in extinct and extant taxa. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 83. [Google Scholar]

- Dixson A 2009. Sexual Selection and the Origin of Human Mating Systems. Oxford University Press; Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy KG 2006. Social dynamics among male chimpanzees: Adaptive significance of male bonds Ph.D. Dissertation. University of California, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy KG, Wrangham RW, Silk JB 2007. Male chimpanzees exchange political support for mating opportunities. Current Biology 17, R586–R587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugdale HL, Pope LC, Newman C, Macdonald DW, Burke T 2011. Age-specific breeding success in a wild mammalian population: selection, constraint, restraint and senescence. Molecular Ecology 20, 3261–3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison PT 2001. On Fertile Ground: A Natural History of Human Reproduction. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Emery Thompson M, Jones JH, Pusey AE, Brewer-Marsden S, Goodall J, Marsden D, Matsuzawa T, Wrangham RW 2007. Aging and fertility patterns in wild chimpanzees provide insights into the evolution of menopause. Current Biology 17, 2150–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emlen DJ 2008. The evolution of animal weapons. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 39, 387–413. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett K, Muhumuza G 2000. Death of a wild chimpanzee community member: Possible outcome of intense sexual competition. American Journal of Primatology 51, 243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldblum JT, Foerster S, Franz M 2018. EloOptimized: Optimized Elo rating method for obtaining dominance ranks. R package version 0.3.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=EloOptimized [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Dunson DB, Vehtari A, Rubin DB 2013. Bayesian Data Analysis, 3rd edition Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadis N 1985. Growth patterns, sexual dimorphism and reproduction in African ruminants. African Journal of Ecology 23, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg TL, Wrangham RW 1997. Genetic correlates of social behaviour in wild chimpanzees: Evidence from mitochondrial DNA. Animal Behaviour 54, 559–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall J 1986. The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Gurven M 2012. Human survival and life history in evolutionary perspective In: Mitani JC, Call J, Kappeler PM, Palombit RA, Silk JB (Eds.), Evolution of Primate Societies. University of Chicago Press, Chicago: pp. 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Gurven M, Kaplan H 2007. Longevity among hunter-gatherers: A cross-cultural examination. Population and Development Review 33, 321–365. [Google Scholar]

- Gurven M, von Rueden C 2006. Hunting, social status and biological fitness. Social Biology 53, 81–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CWM, Pilling AR 1960. The Tiwi of North Australia. Henry Holt, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T, Hiraiwa-Hasegawa M 1983. Opportunistic and restrictive matings among wild chimpanzees in the Mahale Mountains, Tanzania. Journal of Ethology 1, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings WK 1970. Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov chains and their applications. Biometrika 57, 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes K 2003. Grandmothers and the evolution of human longevity. American Journal of Human Biology 15, 380–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes K, O’Connell JF, Blurton Jones NG 2001. Hunting and nuclear families: Some lessons from the Hadza about men’s work. Current Anthropology 42, 681–709. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes K, Paine RR (Eds.) 2006. The Evolution of Human Life History. SAR Press: Santa Fe, NM. [Google Scholar]

- Hill K, Hurtado AM 1996. Ache Life History: The Ecology and Demography of a Foraging People. Aldine de Gruyter, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Hill K, Boesch C, Goodall J, Pusey A, Williams J, Wrangham R 2001. Chimpanzee mortality in the wild. Journal of Human Evolution 40, 437–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell N 2000. Demography of the Dobe !Kung. Aldine de Gruyter, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Isabirye-Basuta G 1988. Food competition among individuals in a free-ranging chimpanzee community in Kibale Forest, Uganda. Behaviour 105, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeggi AV, Hooper PL, Caldwell AE, Gurven MD, Lancaster JB, Kaplan HS 2017. Cooperation between the sexes In: Muller MN, Wrangham RW, Pilbeam DR (Eds.), Chimpanzees and Human Evolution. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: pp. 548–571. [Google Scholar]

- Kaburu SSK, Inoue S, Newton-Fisher NE 2013. Death of the alpha: Within-community lethal violence among chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains National Park. American Journal of Primatology 75, 789–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski ST, Taper ML, Marshall TC 2007. Revising how the computer program CERVUS accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment. Molecular Ecology 16, 1099–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan H, Hooper PL, Gurven M 2009. The evolutionary and ecological roots of human social organization. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 3289–3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan H, Gurven M, Winking J, Hooper PL, Stieglitz J 2010. Learning, menopause, and the human adaptive complex. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1204, 30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keele BF, Jones JH, Terio KA, Estes JD, Rudicell RS, Wilson ML, Li Y, Learn GH, Beasley TM, Schumacher-Stankey J, Wroblewski E, Mosser A, Raphael J, Kamenya S, Lonsdorf EV, Travis DA, Mlengeya T, Kinsel MJ, Else JG, Silvestri G, Goodall J, Sharp PM, Shaw GM, Pusey AE, Hahn BH 2009. Increased mortality and AIDS-like immunopathology in wild chimpanzees infected with SIVcpz. Nature 460, 515–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PS, Coxworth JE, Hawkes K 2012. Increased longevity evolves from grandmothering. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279, 10.1098/rspb.2012.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuester J, Paul A 1992. Influence of male competition and female mate choice on male mating success in Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus). Behaviour 120, 192–217. [Google Scholar]