Abstract

Among 146 nasopharyngeal (NP) and oropharyngeal (OP) swab pairs collected ≤7 days after illness onset, Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction assay for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR) diagnostic results were 95.2% concordant. However, NP swab cycle threshold values were lower (indicating more virus) in 66.7% of concordant-positive pairs, suggesting NP swabs may more accurately detect the amount of SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: coronavirus, nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, testing, SARS-CoV-2

Testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), remains critical for identifying persons with COVID-19 and for implementing clinical and public health interventions to reduce morbidity and mortality and prevent virus transmission. Current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines identify nasopharyngeal (NP) and oropharyngeal (OP) swabs as acceptable upper respiratory specimens to test for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA [1]. Relative to NP swabs, OP swabs may be less challenging to collect, require less healthcare provider training, and, logistically, may be the only option based on available supplies. Some indirect evidence from testing for other respiratory illnesses and coronaviruses suggests OP swabs may be less sensitive than NP swabs [2, 3]. However, to date, limited published data exist about the testing performance of OP swabs compared with NP swabs for SARS-CoV-2 RNA [4].

METHODS

We analyzed data on OP and NP swabs tested for SARS-CoV-2 RNA by the CDC through 3 March 2020. Specimens were tested using the CDC 2019-Novel Coronavirus (nCoV) Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase (RT)-Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Diagnostic Panel designed to detect SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA through 3 genetic markers: N1, N2, and N3 nucleocapsid gene regions [5]. A positive CDC 2019-nCoV RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel test was defined by a cycle threshold (Ct) value of <40 for all 3 gene regions. A negative CDC nCoV RT-PCR Diagnostic Test was defined as failure to detect SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA by 40 cycles for all 3 gene regions. Ct values are inversely correlated with the amount of viral RNA present such that lower Ct values indicate higher amounts of viral RNA in the sample. Although N3 results were analyzed, we do not report them here because their addition to N1 and N2 results produced similar findings and because N3 is no longer included in the CDC 2019-nCoV Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel.

We matched NP and OP swabs collected on the same date from the same person to create NP–OP swab pairs. In our main analysis, we analyzed pairs collected ≤7 days after the reported illness onset date. If more than 1 pair was collected from a person within this time frame, we included the earliest (first) pair in our primary analysis. As a sensitivity analyses, we also examined first pairs collected >7 days after the illness onset date and second follow-up pairs collected >7 days after illness onset (regardless of timing of first pairs).

We examined concordance/discordance in diagnostic results and Ct value distributions between NP and OP swabs within pairs. We also calculated sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for OP swabs compared with NP swabs. NP swabs were selected as the comparator because during the testing time frame, NP swabs were the preferred upper respiratory specimen per CDC guidelines; however, OP swabs were an acceptable alternative specimen for diagnostic testing (independent of NP swab testing/result) [1]. Accordingly, we also calculated absolute sensitivities for OP and NP swabs relative to a positive result on either an OP swab or NP swab. Differences in the proportion testing positive were assessed using the McNemar test, and differences in Ct values were assessed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Data were processed and analyzed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

From 775 OP swabs and 814 NP swabs collected, we matched 736 pairs; of these, 270 (36.7%) had an illness onset date available. These 270 pairs represented 205 unique persons among whom 146 (71.2%) had first pairs collected ≤7 days after illness onset and were included in our main analysis. Specimens were collected from 27 January 2020 through 29 February 2020 at a median of 2 days (interquartile range [IQR], 1–4) after illness onset. The 146 persons who contributed pairs had a median age of 40 years (IQR, 24–56); 55.5% were male.

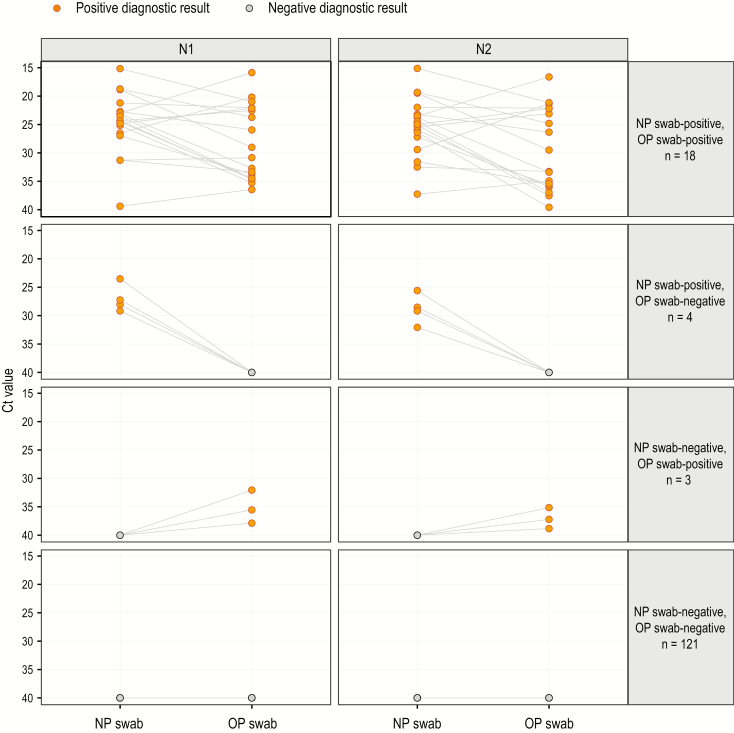

Pair testing results are shown in Figure 1. Among 7 (4.8%) pairs with discordant diagnostic test results, 4 pairs were NP swab-positive and OP swab-negative and 3 pairs had the opposite results. The remaining 139 (95.2%) pairs produced concordant results; 18 (12.3%) pairs were concordantly positive and 121 (82.9%) pairs were concordantly negative. Among the 146 pairs, 14.4% of OP swabs and 15.1% of NP swabs tested positive (P = .71).

Figure 1.

Slope graph of NP–OP swab pair severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) testing Ct values by concordance/discordance of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention DC 2019-Novel Coronavirus Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction Diagnostic Panel diagnostic results (n = 146). The dot on the left of each panel represents the NP swab, and the dot on the right of each panel represents the OP swab. The line drawn between 2 dots indicates an NP–OP swab pair. The negative diagnostic result (gray) Ct value is set to the threshold value of 40. The positive diagnostic result (yellow) is defined as a Ct value <40. N1 and N2 represent separate genetic targets tested for the presence of SARS-COV-2 viral RNA. Abbreviations: Ct, cycle threshold; NP, nasopharyngeal; OP, oropharyngeal.

Among the 18 concordant-positive pairs, the distribution of Ct values was lower (indicating a larger amount of SARS-2-CoV-2 viral RNA) for NP swabs compared with OP swabs. The magnitude and direction of this difference are reflected in the slope of the lines between Ct values for paired NP and OP swabs in Figure 1. The Ct value for NP swabs was lower than for OP swabs in 12 (66.7%) of the 18 concordant-positive pairs for N1 and N2. Median Ct values for NP swabs compared with OP swabs were lower: 24.3 (IQR, 22.7–26.5) vs 29.9 (IQR, 22.1–34.4) for N1 (P = .03) and 25.0 (IQR, 23.2–27.2) vs 31.4 (IQR, 22.2–35.7) for N2 (P = .02).

Using NP swabs as the comparator, OP swabs had specificity of 97.6% (CI, 93.9%–99.5%), sensitivity of 81.8% (CI, 59.7%–94.8%), negative predictive value of 96.8% (92.6%–98.7%), and positive predictive value of 85.7% (CI, 65.9%–94.9%). Absolute sensitivity was 84.0% (CI, 63.9%–95.5%) for OP swabs and 88.0% (CI, 68.8%–97.5%) for NP swabs.

In sensitivity analyses, among 59 first pairs collected >7 days after illness onset (median, 12 days; IQR, 9–19), 14 (23.7%) NP swabs tested positive, while 10 (17.0%) OP swabs tested positive (P = .045). Using NP swabs as the comparator, OP swabs had lower sensitivity (71.4%; CI, 41.9%–91.6%). Absolute sensitivity was 71.4% (CI, 41.9%–91.6%) for OP swabs and 100.0% (CI, 76.8%–100.0%) for NP swabs. Among all first pairs collected (n = 205), we identified 65 follow-up pairs, representing 33 unique persons. Among these 65 pairs, 21 were second pairs collected >7 days after illness onset (median, 15 days; IQR, 10–21). Overall, 4 (19.1%) NP swabs tested positive, while 2 (9.5%) OP swabs tested positive. Given low numbers, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were not calculated among these 21 pairs.

DISCUSSION

Overall, among persons with specimens collected early in the illness course, SARS-CoV-2 RNA diagnostic results were highly concordant between OP and NP swabs. Despite this, among concordant-positive specimens, Ct values were significantly lower among NP swabs. These findings are partially aligned with a study from Germany of persons tested ≤5 days after illness onset that similarly did not find meaningful differences in SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection between NP swabs and OP swabs but, contrastingly, did not find differences in viral loads between NP and OP swabs [6].

In our analysis, using NP swabs as the comparator, specificity and NPV of OP swabs were high and sensitivity and PPV of OP swabs were moderate but had wide CIs that included low values. Absolute sensitivity was only slightly lower for OP swabs compared with NP swabs. Differences in Ct values between NP and OP swabs among concordant-positive pairs did not ultimately impact most diagnostic results in our main analysis where Ct values were relatively low and well under the cutoff value of 40 cycles.

In contrast, in sensitivity analyses of NP–OP swab pairs collected >7 days after illness onset, OP swab sensitivity was comparatively low. Current Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines specifically recommend collection of NP, mid-turbinate, or nasal swabs rather than OP swabs alone for all symptomatic persons. Our findings suggest this recommendation may be particularly relevant for persons who are later in the illness course and who may have a smaller amount of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA [7].

Our findings are subject to at least 4 limitations. First, specimen collection procedures, including type and material of swab used, and specimen handling may impact test performance. Because these data were not available to us, subanalyses, for instance, by type of swab used, were not possible. Second, missing and erroneous personal identification numbers or specimen collection dates limited our ability to match all potential NP and OP swab pairs and account for all specimen pairs for a unique person. If missing data or errors were not at random, this may have biased our results. Third, the number of specimen pairs and the number of positive results were small and precluded our ability to estimate sensitivity and PPV with better precision. Fourth, specimens were tested using the CDC 2019-nCoV Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel, which is currently approved under an emergency use authorization, and our findings, particularly those related to Ct values, may not be generalizable to other nucleic acid tests. Consequently, our findings may not be fully generalizable to current specimen collection and testing circumstances and should thus be interpreted accordingly.

Together, our findings support CDC guidelines that identify NP and OP swabs as acceptable specimens for SARS-CoV-2 RNA testing but suggest that NP swabs may comparatively be a more sensitive specimen type for testing persons who are later in the illness course. Regardless of the type of specimen collected, in persons with a single negative SARS-CoV-2 RNA test, signs and symptoms of COVID-19, epidemiological links, and other risk factors may need to be considered to inform subsequent clinical management and public health interventions to prevent further transmission [5].

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Wendi Kuhnert-Tallman, Barbara Anderson, Charles Rose, and Laurie Barker.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidelines for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens from persons for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html. Accessed 8 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lieberman D, Lieberman D, Shimoni A, Keren-Naus A, Steinberg R, Shemer-Avni Y. Identification of respiratory viruses in adults: nasopharyngeal versus oropharyngeal sampling. J Clin Microbiol 2009; 47:3439–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim C, Ahmed JA, Eidex RB, et al. Comparison of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs for the diagnosis of eight respiratory viruses by real-time reverse transcription-PCR assays. PLoS One 2011; 6:e21610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1177–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC 2019-nCoV Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel instructions for use (effective February 4, 2020). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/rt-pcr-panel-for-detection-instructions.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature 2020; 581:465–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hanson KE, Caliendo AM, Arias CA, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis of COVID-19 Infectious Disease Society of America; Available at: https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-diagnostics/. Accessed 6 June 2020. [Google Scholar]