As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic endures, the ensuing volume of postponed nonurgent endoscopic procedures is creating a new challenge. The accumulation of patients on waiting lists risks causing new problems related to delays in diagnosis or treatment from reduced endoscopic activities. We must balance our eagerness to resume endoscopic activities with the knowledge that increased patient contact during the receding phase of the pandemic could pose a risk of resurgence of the disease over the next few months. The threat of second waves requires us to proceed with extreme care.

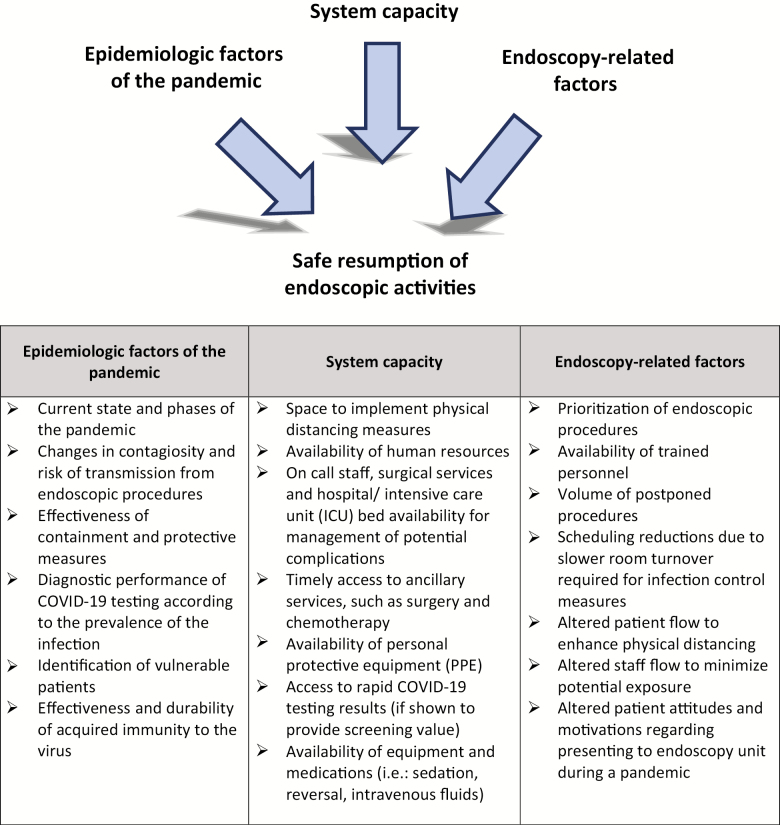

This framework aims to provide guidance to endoscopists and endoscopy unit administrators resuming elective endoscopic activity during the postpeak phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. The World Health Organization suggests the application of physical distancing measures and movement restrictions for at least 2–3 months based on the experience of countries first affected by COVID-19 (1). Decisions on when and how to resume nonurgent endoscopic activities must be based on multiple factors, some internal and some external to the endoscopy unit’s responsibilities. It is proposed that each incremental phase should last a minimum of 2 weeks to allow sufficient time to measure the effect of change and reassess risk. Planning for increases in endoscopic volumes should be a concerted effort with realistic objectives. The following is a nonexhaustive list of factors that need to be taken into account in order to appropriately reintroduce elective endoscopic activity Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Examples of scenarios:

a) In an endoscopy unit with limited availability of PPE but access to timely COVID-19 testing, systematically testing each patient before endoscopy will identify lower-risk patients, mitigate contact risks, help select appropriate PPE and increase the number of nonurgent endoscopies.

b) In a unit well supplied with PPE but with limited access to COVID-19 testing, a systematic pre-endoscopic screening process and structured patient trajectory to adhere to physical distancing guidelines will facilitate the reintroduction of some nonurgent procedures.

c) In a unit with limited availability of PPE and limited access to COVID-19 testing, the unit will need to restrict endoscopic access to only the highest priority indications (priority 1 and 2) and a few selected priority 3 cases until more PPE becomes available. A systematic pre-endoscopic screening process will be required to identify patients who should undergo testing for COVID-19 prior to endoscopy.

Based on a literature review of available recommendations from major endoscopy-oriented scientific organizations and available evidence related to outcomes associated with delaying endoscopic procedures (2–15), the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) COVID working group suggests a hierarchical set of priorities for various endoscopic procedures (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prioritization of endoscopic procedures according to the indication

| Priority 1—perform always | |

|---|---|

| Upper | Emergent upper GI bleeding (Blatchford score over 1) (16) Foreign body or severe/progressive dysphagia Treatment of perforation/leak/fistula/abscess |

| Lower | Acute obstruction needing decompression |

| ERCP | Obstructive jaundice or symptomatic CBD stone Ascending cholangitis |

| Priority 2—should perform | |

| Upper | Nonemergent upper GI bleeding (Blatchford score over 1) High likelihood of upper GI cancer based on imaging, physical examination or symptoms* Variceal ligation after acute bleeding PEG/PEJ or NG/NJ tube placement Endoscopic resection of histologically proven neoplasm (high-grade dysplasia) |

| Lower | Acute lower GI bleeding Investigation of active colitis/new diagnosis or flare of IBD High likelihood of colon cancer based on imaging, physical examination or symptoms* |

| EUS | EUS-guided drainage of symptomatic or infected pancreatic fluid collections/necrosectomy Staging or biopsy for suspected or confirmed cancer* Suspected CBD stone(s), if MRCP not available |

| Priority 3—could perform | |

| Upper | Endoscopic resection of duodenal polyp/ampullectomy Mild/stable dysphagia Enteroscopy for obscure bleeding |

| Lower | Endoscopic resection of large or complex polyp Positive FIT Repeat procedures for prior inadequate preparation Iron-deficiency anemia Rectal bleeding |

| EUS | EUS for submucosal lesion |

| ERCP | Pancreatico-biliary stent removal/revision/replacement |

| Priority 4—defer | |

| Upper | Assessment of reflux esophagitis/PUD healing Investigation for nonalarm symptoms Screening and surveillance gastroscopy |

| Lower | Investigation for nonalarm symptoms Screening and surveillance |

| EUS | Investigation for nonalarm symptoms |

| ERCP | Asymptomatic biliary stricture/gallstones (normal liver enzymes) |

Every decision to perform endoscopy should take into consideration: (a) risks to the patient and endoscopy staff; (b) the potential to change management and/or to alter the prognosis of the patient and (c) health system capacity. Severity of symptoms/laboratory or imaging findings or time spent on the waiting list may change the priority of a given patient that may need to be reassessed on a case-by-case basis. All procedures that do not fit the definition of priority 1–3 should be considered priority 4. A list of patients and their conditions should be updated regularly to reassess the priority of procedures.

*For oncology cases, priority should be based on access to subsequent treatments and expected time to progression.

CBD; common bile duct; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; NG, nasogastric; NJ, nasojejunal; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; PEJ, percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy; PUD, peptic ulcer disease.

Priority categories:

Emergent/life-threatening conditions for which endoscopy must always be performed.

Conditions that may cause early negative impact on patients’ health, quality of life or functional status. These endoscopic procedures will alter management and/or outcome and should be performed.

Indications for which a delay of several weeks will not likely alter the quality of life or prognosis of the patient. Those procedures could be performed when the unit is up to date and can schedule activities beyond ongoing priority 1 and 2 procedures.

Indications with no impact on prognosis or quality of life over many months or years. Should be deferred until the end of the pandemic or until the local epidemiological factors allow high throughput comparable to prepandemic activities.

In conclusion, it is important to acknowledge that resumption of endoscopy services is not likely to be a linear process. Additional phases of reopening and reclosing of endoscopy units for nonurgent procedures may be necessary based on public health recommendations or on local resources. Thus, a stepwise, flexible and adaptative approach is needed. The CAG recognizes that endoscopy is performed within a wide range of contexts, with important differences that can have implications for operational logistics. It is hoped that this framework provides a useful starting point for endoscopy units planning to resume elective endoscopic activity during the postpeak phase(s) of the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation. COVID-19 strategy update. WHO Web site 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/covid-19-strategy-update---14-april-2020 (Accessed April 14, 2020).

- 2. Joint GI Society. Gastroenterology professional society guidance on endoscopic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic ASGE Web site 2020. https://www.asge.org/home/advanced-education-training/covid-19-asge-updates-for-members/gastroenterology-professional-society-guidance-on-endoscopic-procedures-during-the-covid-19-pandemic (Accessed March 17, 2020).

- 3. APAGE. APAGE IBD Working Group Guidelines on the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. APAGE Web site 2020. http://apage.org/files/APAGE_COVID_and_IBD.pdf (Accessed March 17, 2020).

- 4. British Society of Gastroenterology. Endoscopy activity and COVID-19: BSG and JAG guidance. BSG Web site 2020. https://www.bsg.org.uk/covid-19-advice/endoscopy-activity-and-covid-19-bsg-and-jag-guidance/ (Accessed March 17, 2020).

- 5. Castro Filho EC, Castro R, Fernandes FF, Pereira G, Perazzo H. Gastrointestinal endoscopy during COVID-19 pandemic: an updated review of guidelines and statements from international and national societies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gastroenterological Society of Australia. Guide for triage of endoscopic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. GESA Web site 2020. https://www.gesa.org.au/public/13/files/COVID-19/Triage_Guide_Endoscopic_Procedure_26032020.pdf (Accessed March 16, 2020).

- 7. Gralnek IM, Hassan C, Beilenhoff U, et al. ESGE and ESGENA Position Statement on gastrointestinal endoscopy and the COVID-19 pandemic. Endoscopy. 2020;52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. MSSS. Colonosopy referral. MSSS Web site 2017. http://msssa4.msss.gouv.qc.ca/intra/formres.nsf/961885cb24e4e9fd85256b1e00641a29/2f9c2fbcfc52238a85257a08004ff440/$FILE/AH-702A_DT9251(2017-12)D.pdf (Accessed March 17, 2020).

- 9. New Zealand Society of Gastroenterology. Adapted with permission from a paper produced by the British Society of Gastroenterology on management of IBD during the COVID-19 pandemic. NZSG Web site 2020. https://nzsg.org.nz/news-and-events/article/3485 (Accessed March 17, 2020).

- 10. Paterson WG, Depew WT, Paré P, et al. ; Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Wait Time Consensus Group Canadian consensus on medically acceptable wait times for digestive health care. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20(6):411–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gupta S, Shahidi N, Gilroy N, Rex D, Burgess N, Bourke M. A proposal for the return to routine endoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic short title: endoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chiu PWY, Ng SC, Inoue H, et al. Practice of endoscopy during COVID-19 pandemic: position statements of the Asian Pacific Society for Digestive Endoscopy (APSDE-COVID statements). Gut 2020;69:991-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Joint Indian Societies Guidelines - COVID-19 and The Endoscopy Unit. 2020. (Accessed March 4th, 2020, at http://www.isg.org.in/downloads/COVID.pdf.)

- 14. Question et reponses de la SFED sur endoscopie digestive et COVID-19. 2020. (Accessed March 4th, 2020, at https://www.sfed.org/files/files/covid19endo_qr_condrepris.pdf.)

- 15. Suggestions of infection prevention and control in digestive endoscopy during current2019-nCoV pneumonia outbreak in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. 2020. (Accessed March 4th, 2020 at https://www.spg.pt/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Endoscopy_Suggestions-of-Infection-Prevention-and-Control-in-Digestive-Endoscopy-During-Current-2019-nCoV-Pneumonia-Outbreak-in-Wuhan-Hubei-Province-China.pdf.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 2000;356(9238):1318–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]