Abstract

Objective

The COVID-19 pandemic is rapidly evolving and has led to increased numbers of hospitalizations worldwide. Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 experience a variety of symptoms, including fever, muscle pain, tiredness, cough, and difficulty breathing. Elderly people and those with underlying health conditions are considered to be more at risk of developing severe symptoms and have a higher risk of physical deconditioning during their hospital stay. Physical therapists have an important role in supporting hospitalized patients with COVID-19 but also need to be aware of challenges when treating these patients. In line with international initiatives, this article aims to provide guidance and detailed recommendations for hospital-based physical therapists managing patients hospitalized with COVID-19 through a national approach in the Netherlands.

Methods

A pragmatic approach was used. A working group conducted a purposive scan of the literature and drafted initial recommendations based on the knowledge of symptoms in patients with COVID-19 and current practice for physical therapist management for patients hospitalized with lung disease and patients admitted to the intensive care unit. An expert group of hospital-based physical therapists in the Netherlands provided feedback on the recommendations, which were finalized when consensus was reached among the members of the working group.

Results

The recommendations include safety recommendations, treatment recommendations, discharge recommendations, and staffing recommendations. Treatment recommendations address 2 phases of hospitalization: when patients are critically ill and admitted to the intensive care unit, and when patients are severely ill and admitted to the COVID ward. Physical therapist management for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 comprises elements of respiratory support and active mobilization. Respiratory support includes breathing control, thoracic expansion exercises, airway clearance techniques, and respiratory muscle strength training. Recommendations toward active mobilization include bed mobility activities, active range-of-motion exercises, active (assisted) limb exercises, activities-of-daily-living training, transfer training, cycle ergometer, pre-gait exercises, and ambulation.

As of publication date, the number of patients with respiratory syndrome caused by coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is still increasing rapidly worldwide. Spreading of COVID-19 occurs mainly through respiratory droplets and aerosols produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes.1 To our knowledge, there is currently no consensus on the period the virus is transmissible to other humans; however, the duration and transmissibility seem to differ between patients with differing severity of illness.2 Even after resolution of symptoms, individuals might keep shedding the virus.3 Diagnosis of COVID-19 requires detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA using a combination of nasopharynx and throat sample;4,5 SARS-CoV-2 RNA can also be detected in stool and blood.4 Chest computed tomography images from patients with COVID-19 typically demonstrate bilateral, peripheral ground glass opacities. Unfortunately, this pattern is non-specific and overlaps with other infections; therefore, the diagnostic value of chest computed tomography imaging for COVID-19 may be low.4,5

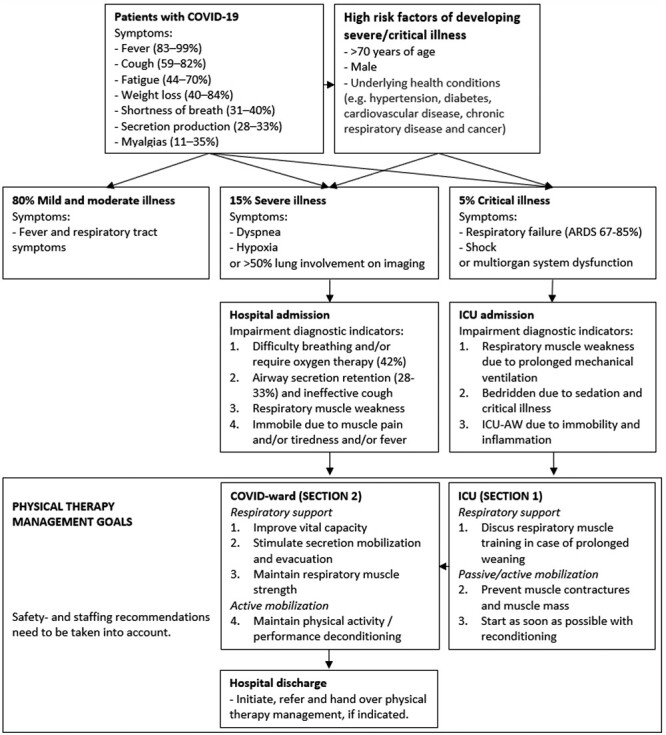

Recent data from China and Italy indicate that in 80% of cases COVID-19 infection causes “mild and moderate illness,” approximately 15% of cases develop “severe illness” leading to hospitalization, and 5% develop “critical illness” requiring ICU treatment.2,4–6 Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 experience a variety of symptoms, including fever, muscle pain, tiredness, cough, and difficulty breathing.7 Elderly people and those with underlying health conditions are considered to be more at risk of developing severe symptoms4 and have a higher risk of physical deconditioning during their hospital stay.8,9 Physical therapists have an important role in supporting hospitalized patients through respiratory support and active mobilization. Physical therapist management should be tailored to the individual patient’s needs concerning frequency, intensity, type, and timing of the interventions, in particular for those with severe/critical illness, older than 70 years of age, obesity, comorbidity, and other complications.10,11 Yet physical therapists need to be aware of potential challenges when treating patients with COVID-19. In a recent study, an international group of authors described the physical therapist management for COVID-19 in an acute hospital setting, including workforce planning, screening, delivery of physical therapist interventions, and personal protective equipment (PPE).12

In line with this international study12 and the consensus statement of Italian respiratory therapists,13 we aim to provide guidance and detailed recommendations for hospital-based physical therapists managing patients hospitalized with COVID-19 through a national approach in the Netherlands.

Scope

This study focuses on adult patients admitted to an (acute) hospital setting due to COVID-19. In general, patients with COVID-19 experience the following signs and symptoms: fever (83%–99%), cough (59%–82%), fatigue (44%–70%), weight loss (40%–84%), shortness of breath (31%–40%), secretion production (28%–33%), and myalgias (11%–35%).4,6 Recent studies showed that illness severity can range from mild to critical:2,4–6

Mild to moderate (mild symptoms up to mild pneumonia): 80%

Severe (dyspnea, hypoxia, or >50% lung involvement on imaging): 15%

Critical (respiratory failure, shock, or multiorgan system dysfunction): 5%

Critical cases, needing ICU treatment, may show symptoms of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) such as lung disease, with widespread inflammation in the lungs.5 Consolidation lesions also remain at long term and can leave fibrotic changes in the lungs.5 Furthermore, patients who are critically ill needing ICU treatment are at risk of developing post-intensive care syndrome (PICS), including ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW).13–15 Mortality among patients admitted to the ICU ranges from 39% to 72%.4

Health care professionals should be aware that the clinical progression of symptoms might occur 1 week after illness onset.5,13,14 Important subgroups are elderly people (≥70 years of age) and those with underlying health conditions (eg, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer), who are considered to be more at risk of developing severe symptoms4 but also at risk of physical deconditioning during hospital stay.8,9

Figure 1 is based on recent literature and shows the flow of patients with COVID-19 with their signs and symptoms before4,6,7 and during hospital admission,4,5,7–9,13,15,16 the severity classification,2,4–6 and the physical therapy goals during hospital stay.10–13,17

Figure 1.

The flow of patients with COVID-19 with their signs and symptoms before4,6,7 and during hospital admission4,5,7,8,13,16; the severity classification,2,4–6 and the physical therapy goals during hospital stay.10–13,17

These recommendations focus on the physical therapist management for adult patients with COVID-19 admitted to the (acute) hospital setting. Recommendations contain specific physical therapy goals concerning respiratory problems and deconditioning, including ICU-AW and PICS. The recommendations are outlined in 2 sections:

Section 1: Patients who are critically ill with COVID-19 admitted to the ICU.

Section 2: Patients who are severely ill with COVID-19 admitted to the COVID ward.

We used existing international recommendations12,13 as the basis for further specification and contextualization. When our recommendations diverge from the international recommendations, we clarified this in the main text and through a separate paragraph with reflections. The recommendations are structured in the following order: safety recommendations, treatment recommendations (specified for different phases of hospitalization), discharge recommendations, and staffing recommendations.

Pragmatic Methodology

Due to the acute and sudden spreading of COVID-19, the evidence base for optimal treatment for this group of patients is evolving rapidly and new insights are emerging at a similar pace. Nevertheless, clear recommendations for hospital-based physical therapist management, either based on evidence or best practices, are crucial to support the recovery of patients and safety of health care professionals. These recommendations will be updated periodically based on new evidence and experience and will be made available through the website of the Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy and the World Confederation for Physical Therapy.

To cope with this rapidly evolving evidence base, we utilized a pragmatic approach, rather than a formal approach (such as Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation [GRADE]),18 to formulate our recommendations. First a working group was installed comprising experts on content (K.F., R.O., E.K., N.K., M.S., E.H.) and experts on guideline methodology (F.D., T.H., P.W.). The working group members conducted a purposive scan of the literature and drafted the initial recommendations based on the knowledge of symptoms in patients with COVID-19 and current practice for physical therapist management in patients hospitalized with lung diseases and in patients admitted to the ICU. Simultaneously, an expert group of hospital-based physical therapists in the Netherlands (see Acknowledgments) was formed based on the formal and informal networks of the working group. This expert group served as a sounding board group. Recommendations drafted by the working group based on available evidence and best practices were discussed with the expert group. Considerations by the expert group were discussed in the working group. Recommendations were finalized when consensus, in terms of no opposing votes, was reached among the members of the working group.

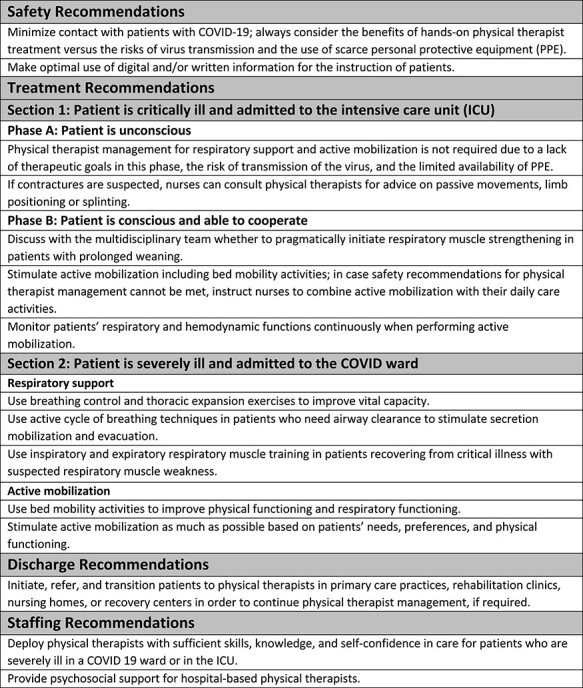

The final recommendations are summarized in Figure 2. We sought and received endorsements for our recommendations from 40 hospital-based physical therapists from over 20 Dutch hospitals, the Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy, the Dutch Association for Hospital-Based Physical Therapists, Association for Cardiovascular and Respiratory Physical Therapists, and the Dutch Society for Intensive Care Medicine. The authors and consulted experts were all based in the Netherlands; therefore, generalizability to hospital-based physical therapy settings in other countries, with different health care organizations, different task profiles, and different scope of practice, could be limited.

Figure 2.

Summary of recommendations for hospital-based physical therapists managing patients with COVID-19.

Recommendations: Safety

Respiratory droplets and aerosols may be released from patients during physical therapist interventions and may cause further spread of the virus. Direct contact between physical therapists and patients with COVID-19, therefore, should be minimized to avoid risk of virus transmission and reduce usage of scarce PPE. Therefore, we recommend physical therapists make optimal use of telecommunication and written information material. If direct (face-to-face) contact with patients with COVID-19 is required, physical therapists should use PPE. Recommended PPE include a gown, gloves, eye protection, and a facemask.4 Procedures for the use of PPE vary between hospitals; therefore, the use of PPE should be checked locally with hospital officers for hygiene and infection prevention. Concerning adequate use of PPE, treating physical therapists should be informed that certain treatment modalities can lead to extra viral exposure. The following procedures can induce the release of droplets and aerosols12,13,19:

Noninvasive assisted ventilation or high-flow nasal oxygen therapy;

Manual techniques for respiratory support, including compression, which may lead to coughing and secretion mobilization;

Secretion mobilization devices, such as positive expiratory pressure, Flutter Mucus Clearance Device (Allergan Pharmaceutical Company, Dublin, Ireland); Acapella DM & DH Vibratory PEP Therapy System (Smiths Medical Inc, Carlsbad, CA); and high-frequency chest wall oscillation devices;

Endotracheal suctioning;

Active mobilization, which may lead to coughing and secretion mobilization or disconnection of the mechanical ventilation.

If one of the above procedures is performed, physical therapists are recommended to wear a facemask that filters at least 95% of airborne particles (ie, FFP2 mask, N95 facemasks). Physical therapists should ensure that they are fully competent in the use of PPE.4 Safety recommendations need to be taken into account during all steps in physical therapist management. Benefits of hands-on physical therapist management should always be weighed against the potential risks of virus transmission.

→ Recommendation: Minimize contact with patients with COVID-19; always consider the benefits of hands-on physical therapist treatment vs the risks of virus transmission and the use of scarce PPE.

→ Recommendation: Make optimal use of digital and/or written information for the instruction of patients.

Recommendations: Treatment

Physical therapist management for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 comprises elements of respiratory support and active mobilization.20,21 Recommendations toward respiratory support, defined as the “proactive approach to minimize respiratory symptoms during the acute phase of a pulmonary disease,”22 are presented in detail. In the treatment of patients with COVID-19, respiratory support can consist of breathing control, thoracic expansion exercises, airway clearance techniques, and respiratory muscle strength training. Recommendations toward active mobilization concern the “proactive approach to support any physical activity where patients assist with the activity using their own strength and control: patients may need assistance from staff or equipment, but they are actively participating in the exercise.”21 Examples of active mobilization are bed mobility activities (eg, bridging, rolling, lying to sitting), active range-of-motion exercises, active (assisted) limb exercises, activities of daily living (ADL) training, transfer training, cycle ergometer, pre-gait exercises, and ambulation.23

Section 1: Patient Is Critically Ill and Admitted to ICU

Recommendations for physical therapy during mechanical ventilation in the ICU depend on the level of consciousness and cooperation of the patient.17 Therefore, the recommendations for physical therapist management differ between Phase A, where the “patient is unconscious’” (Richmond Agitation and Sedation Score [RASS] < −2 and Standardized 5 Questions [S5Q] <3); and Phase B, where the “patient is conscious and able to cooperate” (RASS score ≥ −2 and S5Q ≥ 3).17

Phase A: Patient is unconscious: respiratory support

Patients with critical illness due to COVID-19 may develop ARDS-like symptoms, requiring admission to the ICU.24 Initially, the majority of patients are deeply sedated (RASS ≤ −4) and mechanically ventilated in prone position.25 These patients often receive neuromuscular blocking agents to support mechanical ventilation, as this drug application can improve chest wall compliance, eliminate ventilator dyssynchrony, and reduce intraabdominal pressures.26 Given the lack of therapeutic goals in this phase, physical therapist management concerning respiratory support is not recommended. This might be different for physical therapists outside the Netherlands with other scope of practice concerning respiratory support.

Phase A: Patient is unconscious: active mobilization

Patients who are deeply sedated cannot actively participate in mobilization. Physical therapist management in this phase focuses on maintaining joint mobility and preventing (soft tissue) contractures. The administering of neuromuscular blocking agents, however, reduces the risk of contractures.27 Additionally, the evidence base for preventive stretching is limited.28 Based on these considerations, we think that the risk of transmission of the virus and the limited availability of PPE do not outweigh the benefits of regular joint mobility screening by physical therapists. When neuromuscular blocking agents are discontinued, the risk for developing contractures increases. If contractures are suspected, nurses can consult physical therapists for advice on passive movements, limb positioning, or splinting.17

→ Recommendation: Physical therapist management for respiratory support and active mobilization is not required due to a lack of therapeutic goals in this phase, due to the risk of transmission of the virus, and due to the limited availability of PPE.

→ Recommendation: If contractures are suspected, nurses can consult physical therapists for advice on passive movements, limb positioning, or splinting.

Phase B: Patient is conscious and able to cooperate: respiratory support

The moment sedation is reduced (RASS ≥ −2) and the patient is conscious and able to cooperate (S5Q ≥ 3), a new phase starts.25 Normally, this is the phase to start active mobilization and respiratory support; however, in patients with COVID-19, detachment of the closed mechanical ventilation system circuit should always be avoided due to the risk of virus transmission. Even in the case of weaning from mechanical ventilation, where physical therapists typically aim to ensure sufficient inspiratory muscle strength,29,30 the risk of virus transmission via droplets or aerosols in using medical assistive testing devices is too high. Therefore, we recommend not detaching the ventilation system for the purpose of respiratory function testing, respiratory muscle training, or breathing exercises.19 To our knowledge, it remains unclear if both droplets and aerosols are filtered by disposable bacterial filters.31

In case of prolonged weaning, patients who fail more than 3 weaning attempts or require more than 7 days of weaning after the first spontaneous breathing trail,32 respiratory muscle training should be discussed in the multidisciplinary team.30 The team may decide that benefits of respiratory muscle training outweigh the safety risks.

In the phase after prolonged (assisted) mechanical ventilation, inspiratory (IMT) and expiratory muscle training can be used to counterbalance the weakness of the respiratory muscles.29,33 Moreover, additional benefits of strengthening are increased exercise tolerance and cough strength. Usually, noninvasive handheld manometers to assess maximal static inspiratory pressure can help quantify respiratory muscle strength and initiate training.34,35 Usually, scores lower than 30 cmH2O may indicate a degree of inspiratory muscle weakness that could impact on weaning and recovery.36 However, the use of these devices is not recommended in patients with COVID-19 due to the increased risk of virus transmission. In this situation, training can be started pragmatically (ie, without respiratory testing results) using a threshold training device with low resistance (<10 cmH2O) and can be increased based on clinical presence, experienced dyspnea, and Borg score for perceived exhaustion.37 For respiratory muscle strengthening, a combination of both IMT and expiratory muscle training is recommended, as this combination is superior to IMT alone in improving respiratory muscle strength.33 As respiratory muscle training devices could carry the virus (prolonged), the use of these devices should be discussed with hospital officers for hygiene and infection prevention.

→ Recommendation: Discuss with the multidisciplinary team whether to pragmatically initiate respiratory muscle strengthening in patients with prolonged weaning.

Phase B: Patient is conscious and able to cooperate: active mobilization

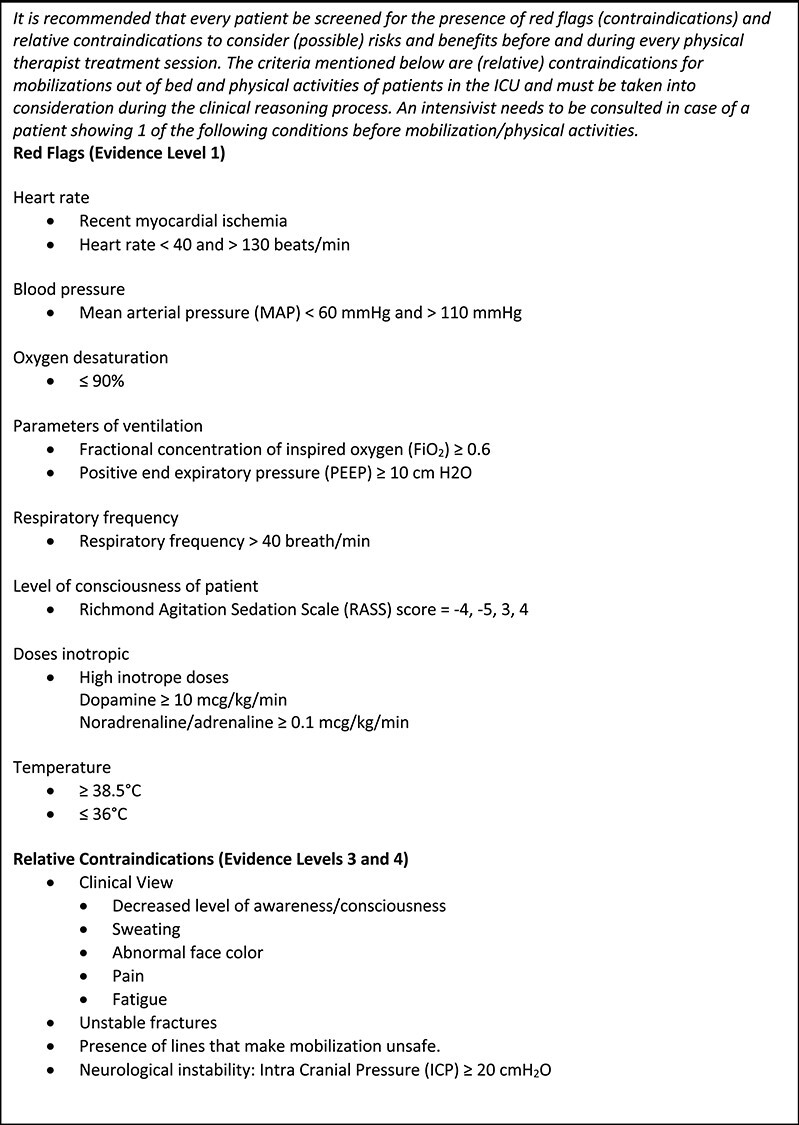

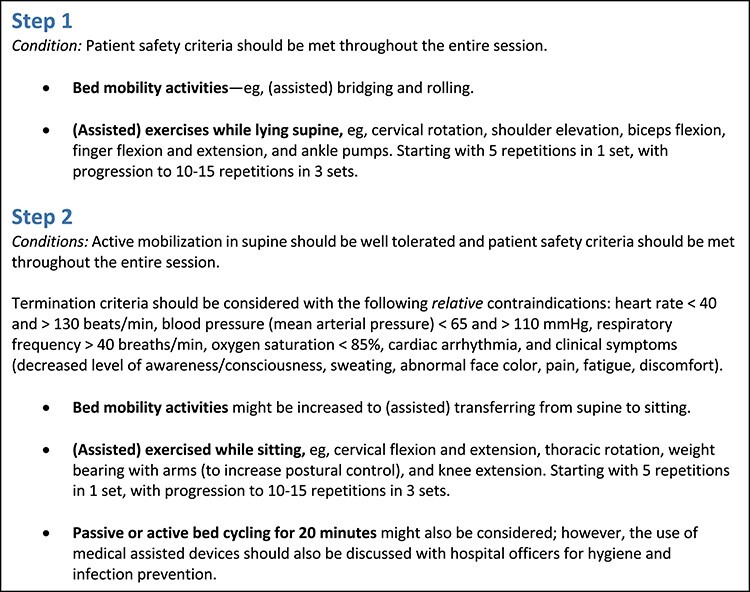

When patients become conscious and cooperative, active mobilization can be considered. Active mobilization should aim to prevent ICU-AW and deconditioning from immobilization and illness. The Medical Research Council Sum-Score is widely used to diagnose ICU-AW, which is defined as an Medical Research Council Sum-Score < 48.38 It is assumed that patients diagnosed with ICU-AW may benefit from active mobilization also following their ICU admission.39 These physical activities for patients who are critically ill should be planned and targeted following the evidence-based statement for physical therapist management in the ICU as much as possible.17 Patient safety criteria according to Sommers et al17 for active mobilization that always need to be considered at the ICU are presented in Figure 3. Close monitoring of respiratory and hemodynamic functions of patients is crucial to ensure patients’ safety.17,21 As a first step, bed mobility activities can be performed by assisting bridging, rolling, and transferring from supine to sitting.23 Medical assistive devices (eg, a bed cycle) might be used to support active mobilization. However, use of these devices should be discussed with hospital officers for hygiene and infection prevention. To evaluate and increase training intensity, frequency, and/or activities, criteria of American College of Sports Medicine guidelines for exercise testing and prescription,40 Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale,37 and/or the evidence-based statement of Sommers et al17 can be used. Figure 4 shows our expert opinion suggestions for active mobilization sessions in patients with COVID-19 at the ICU.

Figure 3.

Criteria for safety of treatment according to Sommers et al.17 Level of evidence of the literature and clinical expertise: level 1 = recommendation based on evidence of research of level A1 (systematic review) or at least 2 independent studies of level A2 (randomized controlled trial of good quality and size); level 2 = recommendation based on 1 study of level A2 or at least 2 independent studies of level B (randomized controlled trial of moderate or weak quality or insufficient size, or other comparative studies, eg, patient controlled and longitudinal cohort studies); level 3 = recommendation based on 1 study of level B or level C (non-comparative studies); level 4 = recommendation based on expert opinion.

Figure 4.

Expert opinion suggestions for active mobilization sessions in patients who are critically ill with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit (ICU), Phase B.

Ideally, the physical therapist is the leading health care professional to guide active mobilization. However, safety recommendations can also be decisive in initiating physical therapist management. If safety recommendations for health care providers do not warrant direct physical therapy contact, we recommend instructing nurses to combine active mobilization with daily care activities. In this case, the physical therapist has a coaching role.

→ Recommendation: Stimulate active mobilization including bed mobility activities; in case safety recommendations for physical therapist management cannot be met, instruct nurses to combine active mobilization with their daily care activities.

→ Recommendation: Monitor patients’ respiratory and hemodynamic functions continuously when performing active mobilization.

Section 2: Patient Is Severely Ill and Admitted to the COVID Ward

Patients who are severely ill with COVID-19 who require hospitalization can present with complications such as pneumonia, hypoxemic respiratory failure/ARDS, sepsis and septic shock, cardiomyopathy and arrhythmia, acute kidney injury, and complications from prolonged hospitalization, including secondary bacterial infections.4 Because the consequences of the infection impact the respiratory system, one of the goals of physical therapist management is to optimize respiratory function. Therefore, respiratory support aims to improve breathing control, thoracic expansion, and mobilization/evacuation of secretion. Active mobilization aims to increase (or maintain) physical functioning and independence in ADL. These recommendations also apply for patients recovering from critical illness due to COVID-19. Additionally, in patients recovering from critical illness, respiratory muscle strength/endurance training can be continued.

Respiratory support

Respiratory support serves several purposes: to improve vital capacity, to evacuate secretion, and to strengthen respiratory muscle. Techniques and goals are briefly introduced as follows:

Improvement of vital capacity: To relax the airways and relieve the symptoms of wheezing and tightness that normally occur after coughing or breathlessness (respiratory frequency >25 breath/min, Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale >4), breathing control is used. Breathing control can help if patients with COVID-19 are experiencing shortness of breath, fear, or anxiety or are in a panic.41 It stimulates tidal volume breathing, with neck and shoulders relaxed and the diaphragm contracting for inspiration. Patients should be encouraged to breathe in through their nose to humidify, warm, and filter the air and to decrease the turbulence of inspired flow.42 The length of time spent performing breathing control may vary depending on how breathless patients feel.41 Difficulty of breathing can be evaluated using the Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale.37 Thoracic expansion exercises are recommended to improve ventilation also in the lower lung fields. This increases the vital capacity and improves lung function, especially if atelectasis is present.43 Patients should be stimulated to inhale deeply and slowly, combined with chest expansion and shoulder expansion.8 Extra stimuli can be provided through visual feedback using incentive spirometry.43 Thoracic hyperinflation should be prevented using adequate monitoring of performance.

Evacuation of secretion: Early reports indicate that patients with COVID-19 do not show airway mucus hypersecretion;24,44 however, patients with specific comorbidities (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis, neuromuscular disease) might actually need respiratory support due to airway secretion retention or ineffective cough.13 In case of clinical signs for presence of airway secretion (by hearing, feeling, or chest x-ray), different techniques and devices can be applied to mobilization or evacuation. When using these techniques, please keep the safety recommendations in mind. The active cycle of breathing techniques (ACBT) are the preferred procedure. This also includes the breathing control and thoracic expansion exercises, and combines these with huffing and coughing.41,42,45 Huffing and coughing contribute to the formation of respiratory droplets and aerosols and should be avoided in direct contact with health care professionals. Therefore, these maneuvers are only recommended in case of airway obstruction due to excess secretions. The multidisciplinary team should carefully evaluate whether airway obstruction is present through medical history taking (eg, the presence of productive cough), physical examination (eg, the presence of pulmonary rhonchus), and observations. Telecommunication and/or written instruction material can be used to support the use of ACBT. If patients fail to effectively use ACBT, teaching these techniques under direct supervision of a physical therapist can be considered.

-

Strengthening of respiratory muscle: Patients with COVID-19 might have suspected respiratory muscle weakness caused by prolonged mechanical ventilation during ICU stay. After transfer to the COVID ward, respiratory muscle strengthening can be continued for patients recovering from critical illness according to the recommendations in Section 1, Phase B. Training protocols typically use resistive loads ranging between 30% and 80% of maximal static inspiratory pressure.46 However, the use of noninvasive handheld manometers is not recommended in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 due to the increased risk of virus transmission. According to Section 1, Phase B, training can be started pragmatically (ie, without respiratory testing results) using a threshold training device with low resistance (<10 cmH2O) and can be increased based on clinical presence, experienced dyspnea, and Borg score for perceived exhaustion.37 One of the unique advantages of respiratory muscle training is that it can be implemented in shorter intervals (30 breaths, 2 times/d). Training effects from respiratory muscle training have been observed for multiple protocols lasting only 4 weeks.46 A telehealth or mobile app–based model would allow for the opportunity for real-time remote monitoring of compliance and assessment. Telehealth and home-based models for respiratory muscle training have been studied with similar effects.47

Recommendation: Use breathing control and thoracic expansion exercises to improve vital capacity.

Recommendation: Use active cycle of breathing techniques in patients who need airway clearance to stimulate secretion mobilization and evacuation.

Recommendation: Use inspiratory and expiratory respiratory muscle training in patients recovering from critical illness with suspected respiratory muscle weakness.

Active mobilization

If patients are bedridden and suffering from COVID-19, pulmonary ventilation can be stimulated by bed mobility activities through bridging, rolling, and sitting.11 If possible, patients might assist with their own strength and control. If needed, staff and equipment can be used to support the activity. A vertical position can be obtained with less support of patients by tilting the bed or using a tilt table.

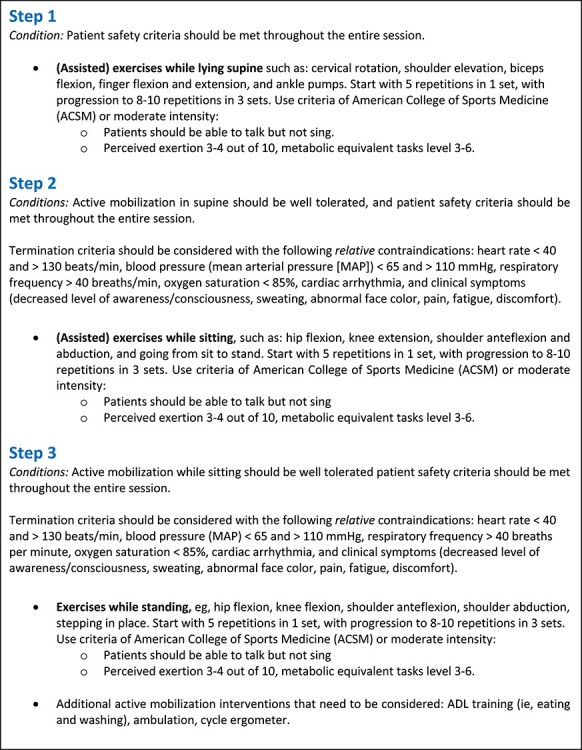

To prevent further deconditioning, patients should be stimulated to be physically active through active mobilization as much as possible through the hospitalization period. Physical therapists can provide specific exercises and training that meet the needs and preferences of patients with COVID-19. Maintaining or improving physical functioning should be executed following common safety recommendations, monitoring, and guidance.17,21 Based on our expert opinion, at least patient’s saturation and heart rate should be monitored before and during active mobilization due to the low and fluctuating vital capacity of patients with COVID-19. Active mobilization interventions that need to be considered are bed mobility activities, active range of motion exercises, active (assisted) limb exercises, ADL training, transfer training, cycle ergometer, pre-gait exercises, and ambulation.23 Sitting and standing are the preferred postures for patients, if possible. To evaluate and increase training intensity, frequency, and/or activities, criteria of American College of Sports Medicine guidelines for exercise testing and prescription,40 Borg score,37 and/or the evidence-based statement of Sommers et al17 can be used. Figure 5 shows our expert opinion suggestions for active mobilization sessions in patients with COVID-19 in the COVID ward.

Figure 5.

Expert opinion suggestions for active mobilization sessions in patients who are severely ill with COVID-19 in the COVID ward.

Instructions can be provided through telecommunication, flyers, and/or videos when patients are physically and cognitively capable to exercise independently. If patients with COVID-19 are unable to exercise independently, for example as the result of ICU-AW, and safety recommendations by physical therapists cannot be met, it is recommended to instruct nurses how to support active mobilization. It is a decision of the interprofessional team of health care professionals to assess benefits of support by a physical therapist vs the risks of viral transmission and limited use of PPE.

Recommendation: Use bed mobility activities to improve physical functioning and respiratory functioning.

Recommendation: Stimulate active mobilization as much as possible based on patients’ needs, preferences, and physical functioning.

Discharge Recommendations

The hospital-based physical therapist should screen patients with severe illness due to COVID-19 on whether physical therapist management should be continued after hospital discharge.48 Patients may experience loss of function and independence due to hospitalization and in severe cases develop a PICS, including physical, cognitive, and mental impairments, as a result of their prolonged stay in the ICU.14,49–51 Based on earlier experiences and knowledge from the SARS epidemic (SARS-CoV),52 substantial increases can be expected in long-term health care need for patients with COVID-19. Continuing care based on patients’ needs after hospital discharge is important. The hospital-based physical therapist has an important role in warranting continuity of physical therapist management. When hospital discharge is forthcoming, sufficient hand-over of patient information to physical therapists working in primary care practices, rehabilitation clinics, nursing homes, or recovery centers is needed. Based on clinical expertise with post-ICU rehabilitation, it is recommended that discharge information should at least contain anamnestic information (medical, psychosocial), patient’s clinical question, goals and provided physical therapy and recovery process, current limitations in functioning and daily life activities, and other involved health care professionals.49–51

Recommendation: Initiate, refer, and transition patients to physical therapists in primary care practices, rehabilitation clinics, nursing homes, or recovery centers to continue physical therapist management, if required.

Staffing Recommendations

Professional Expertise

Careful planning is required when physical therapists are deployed in departments where they are not used to work, such as the ICU. Hospital-based physical therapists should have adequate knowledge, skills, and attitude in terms of self-confidence to treat patients in isolation, with complex respiratory problems, low physical functioning and with complex acute care needs. The deployment of physical therapists in a COVID-19 ward or ICU with sufficient skills, knowledge and attitude (self-confidence) and experience in critical care should be optimized.19 Hospital-based physical therapists with these skills and knowledge should be tasked with training of less experienced colleagues to provide them with the necessary skills, knowledge and self-confidence for physical therapist management of patients with COVID-19.

Recommendation: Deploy physical therapists with sufficient skills, knowledge and self-confidence in care for patients who are severely ill at a COVID-19 ward or in the ICU.

Psychosocial Support

The COVID-19 outbreak presents new challenges for health care professionals. Physical therapists will work intensively with patients who are severely ill, which can lead to mental health distress. It is recommended for managers to plan sufficient recovery time between work shifts of physical therapists and to let less experienced colleagues carefully be supervised by experienced peers. In these turbulent times, provision of psychosocial support should be considered.

Recommendation: Provide psychosocial support for hospital-based physical therapists.

Reflections

In this manuscript, we provide detailed recommendations and intervention descriptions for hospital-based physical therapists managing patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the Netherlands. Our recommendations are generally in line with the recent international clinical practice recommendations of Thomas et al12 and the consensus statement of Italian respiratory therapists.13 However, there are a number of differences in physical therapist interventions:

We do not recommend neuromuscular electrical stimulation in bedridden patients with COVID-19 because of the lack of robust evidence of effectiveness, the hygienic aspect, the absence of the equipment in most Dutch hospitals, and our concerns about the feasibility during the hectic care of patients who are severely or critically ill.

We do not recommend providing certain aspects of respiratory therapy care such as endotracheal suctioning or adjusting oxygen therapy, because these procedures are outside the scope of practice of Dutch physical therapists.

In our recommendations, we focused on physical therapists managing hospitalized patients with COVID-19. However, it is important that recommendations will be provided for the multidisciplinary care after hospital discharge given the physical, cognitive, and mental impairments of patients with COVID-19. In addition, COVID-19 is a novel disease and our understanding of the symptomatology, clinical course, recovery, and transmissibility is emerging. Thus, treatment paradigms need to be evaluated and updated as new information becomes available.

Contributor Information

Karin M Felten-Barentsz, Department of Rehabilitation, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center, Geert Grooteplein 21, Nijmegen 6500 HB, the Netherlands.

Roel van Oorsouw, Department of Rehabilitation, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center.

Emily Klooster, Department of Rehabilitation, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center and Department of Rehabilitation, Deventer Ziekenhuis, Deventer, the Netherlands.

Niek Koenders, Department of Rehabilitation, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center.

Femke Driehuis, Department of Guideline Development, Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (KNGF), Amersfoort, the Netherlands.

Erik H J Hulzebos, Child Development and Exercise Centre, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Marike van der Schaaf, Department of Rehabilitation, Amsterdam Movement Sciences, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and Faculty of Health, ACHIEVE-Centre of Applied Research, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Thomas J Hoogeboom, Department of Rehabilitation, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center and IQ Healthcare, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center.

Philip J van der Wees, Department of Rehabilitation, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center and IQ Healthcare, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center.

Author Contributions and Acknowledgments

Concept/idea/research design: K.M. Felten-Barentsz, R. van Oorsouw, E. Klooster, N. Koenders, F. Driehuis, E.H.J. Hulzebos, T.J. Hoogeboom, P.J. van der Wees

Writing: K.M. Felten-Barentsz, R. van Oorsouw, E. Klooster,N. Koenders, F. Driehuis, E.H.J. Hulzebos, M. van der Schaaf, T.J. Hoogeboom, P.J. van der Wees

Data collection: K.M. Felten-Barentsz, M. van der Schaaf

Data analysis: K.M. Felten-Barentsz

Project management: K.M. Felten-Barentsz, T.J. Hoogeboom, P.J. van der Wees

Providing facilities/equipment: T.J. Hoogeboom

Providing institutional liaisons: T.J. Hoogeboom

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): E. Klooster, N. Koenders, M. van der Schaaf, T.J. Hoogeboom,P.J. van der Wees

K.M. Felten-Barentsz, R. van Oorsouw, E. Klooster, and N. Koenders contributed equally to this work.

The recommendations were developed in collaboration with the following hospital-based physical therapists in the Netherlands: Amanda van Bergen, Anne de Vries, Bert Strookappe, Bram van den Buijs, Daniëlle Conijn, Edwin Geleijn, Edwin van Adrichem, Ellen Oosting, Eva Spoor, Geert van der Sluis, Guido Dolleman, Hanneke van Dijk-Huisman, Hans Steijlen, Joost van Wijchen, Jordi Elings, Juultje Sommers, Lieven de Zwart, Linda van Heusden-Scholtalbers, Luc Stalman, Maarten Werkman, Maurice Sillen, Marian de Vries, Mariska Klaassen, Marleen Scholtens, Marlies Wilting, Miranda van Helvoort, Miriam van Lankveld, Nathalie Dammers, Peter Dijkman, Petra Bor, Resi Mulders, Robert van der Stoep, Roland van Peppen, Rudi Steenbruggen, Siebrand Zoethout, Susan Lassche, Sylvia van Dijk, Tom Hendrickx, Ton Lenssen, and Willemieke Driebergen.

Funding

The Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (KNGF) supported the development of the recommendations.

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020;395:1225–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chang MG, Mo G, Yuan X, et al. Time kinetics of viral clearance and resolution of symptoms in novel coronavirus infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1150–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. CDC . Interim clinical guidance for management of patients with confirmed coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. https: //www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html . 2020. Accessed June 9, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liang T. Handbook of COVID-19 Prevention and Treatment. The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. 2020;1–60. https://esge.org/documents/Handbook_of_COVID-19_Prevention_and_Treatment.pdf.

- 6. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organisation . Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report, 51. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sourdet S, Lafont C, Rolland Y, et al. Preventable iatrogenic disability in elderly patients during hospitalization. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: she was probably able to ambulate, but I'm not sure. JAMA. 2011;306:1782–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ambrosino N, Clini EM. Response to pulmonary rehabilitation: toward personalised programmes? Eur Respir J. 2015;46:1538–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wouters EFM, Wouters B, Augustin IML, et al. Personalised pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27:170125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peter Thomas CB, Bissett B, Boden I, et al. Physiotherapy management for COVID-19 in the acute hospital setting: clinical practice recommendations. J Physiother. 2020;66:73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vitacca M, Carone M, Clini EM, Paneroni M, Lazzeri M, Lanza A, et al. Joint statement on the role of respiratory rehabilitation in the COVID-19 crisis: the Italian position paper. Respiration. 2020;1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders' conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:502–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Appleton RT, Kinsella J, Quasim T. The incidence of intensive care unit-acquired weakness syndromes: a systematic review. J Intensive Care Soc. 2015;16:126–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Connolly B, Salisbury L, O'Neill B, et al. Exercise rehabilitation following intensive care unit discharge for recovery from critical illness: executive summary of a Cochrane collaboration systematic review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7:520–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sommers J, Engelbert RH, Dettling-Ihnenfeldt D, et al. Physiotherapy in the intensive care unit: an evidence-based, expert driven, practical statement and rehabilitation recommendations. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29:1051–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the journal of clinical epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:380–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. NHS . COVID-19: respiratory physiotherapy on call information and guidance. https://www.csp.org.uk/documents/coronavirus-respiratory-physiotherapy-call-guidanceLast update: March 14, 2020, version 2. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- 20. Gosselink R, Bott J, Johnson M, et al. Physiotherapy for adult patients with critical illness: recommendations of the European Respiratory Society and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Task Force on Physiotherapy for Critically Ill Patients. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1188–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hodgson CL, Stiller K, Needham DM, et al. Expert consensus and recommendations on safety criteria for active mobilization of mechanically ventilated critically ill adults. Crit Care. 2014;18:658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nici L, Donner C, Wouters E, et al. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1390–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Doiron KA, Hoffmann TC, Beller EM. Early intervention (mobilization or active exercise) for critically ill adults in the intensive care unit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:Cd010754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xie J, Tong Z, Guan X, et al. Critical care crisis and some recommendations during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:837–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Greenberg SB, Vender J. The use of neuromuscular blocking agents in the ICU: where are we now? Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1332–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Van der Schaaf M. Bewegingsbeperkingen bij patiënten die in buikligging Worden verpleegd. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Intensive Care. 1998;13:88–91. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harvey LA, Katalinic OM, Herbert RD, et al. Stretch for the treatment and prevention of contractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1:Cd007455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vorona S, Sabatini U, Al-Maqbali S, et al. Inspiratory muscle rehabilitation in critically ill adults. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15:735–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Magalhaes PAF, Camillo CA, Langer D, et al. Weaning failure and respiratory muscle function: what has been done and what can be improved? Respir Med. 2018;134:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wilkes AR, Benbough JE, Speight SE, et al. The bacterial and viral filtration performance of breathing system filters. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boles JM, Bion J, Connors A, et al. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:1033–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xu W, Li R, Guan L, et al. Combination of inspiratory and expiratory muscle training in same respiratory cycle versus different cycles in COPD patients: a randomized trial. Respir Res. 2018;19:225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society. Statement on respiratory muscle testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:518–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Laveneziana P, Albuquerque A, Aliverti A, et al. ERS statement on respiratory muscle testing at rest and during exercise. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bissett B, Gosselink R, van Haren FMP. Respiratory muscle rehabilitation in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation: a targeted approach. Crit Care. 2020;24:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:377-381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hermans G, Clerckx B, Vanhullebusch T, et al. Interobserver agreement of Medical Research Council sum-score and handgrip strength in the intensive care unit. Muscle Nerve. 2012;45:18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Connolly B, Thompson A, Moxham J, et al. Relationship of Medical Research Council sum-score with physical function in patients post critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:A3075. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pescatello LS , ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. American College of Sports Medicine 9th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014;1–482. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Underwood F, Active Cycle of Breathing Technique. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Active_Cycle_of_Breathing_Technique#cite_note-ACPRC-7. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- 42. Nicolson C, Lee A. Bronchiectasis toolbox: the active cycle of breathing technique. https://bronchiectasis.com.au/physiotherapy/techniques/the-active-cycle-of-breathing-technique.

- 43. Restrepo RD, Wettstein R, Wittnebel L, et al. Incentive spirometry: 2011. Respir Care. 2011;56:1600–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, et al. Time course of lung changes on chest CT during recovery from 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020:200370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lewis LK, Williams MT, Olds TS. The active cycle of breathing technique: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med. 2012;106:155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Langer D, Charususin N, Jacome C, et al. Efficacy of a novel method for inspiratory muscle training in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Phys Ther. 2015;95:1264–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nikoletou D, Man WD, Mustfa N, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a home-based inspiratory muscle training programme in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using multiple inspiratory muscle tests. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:250–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Falvey JR, Burke RE, Malone D, et al. Role of physical therapists in reducing hospital readmissions: optimizing outcomes for older adults during care transitions from hospital to community. Phys Ther. 2016;96:1125–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Major ME, Kwakman R, Kho ME, et al. Surviving critical illness: what is next? An expert consensus statement on physical rehabilitation after hospital discharge. Crit Care. 2016;20:354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Major ME, van Nes F, Ramaekers S, et al. Survivors of critical illness and their relatives. A qualitative study on hospital discharge experience. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16:1405–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kwakman RCH, Major ME, Dettling-Ihnenfeldt DS, et al. Physiotherapy treatment approaches for survivors of critical illness: a proposal from a Delphi study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2019;1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hui D, Tsang K. SARS: sequelae and implications for rehabilitation. In book: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. 2008: 36–41.