Abstract

Objective:

A population-level, randomized controlled trial was conducted to test the effectiveness of a parent recruitment package for increasing initial engagement into a school-based parenting program and to identify strategies responsible for effects.

Method:

Participants were caregivers of kindergarten- to third-grade students (N = 1,276) attending one of five schools serving ethnically diverse families living in mostly low-income, urban conditions. First, families were randomly assigned to be recruited for research surveys or not, and then to a parenting program recruitment condition: 1) Engagement-as-usual (EAU) informational flyer; 2) EAU + testimonial booklet; 3) EAU + teacher endorsement; 4) EAU + recruitment call; or 5) all strategies (full package). Caregivers were offered a free parenting program at their child’s school. Primary dependent variables were parenting program enrollment and attending at least one session (initiation). Exploratory analyses were conducted on program completion, attendance across sessions, homework completion, and in-session participation.

Results:

In the population-level sample, enrollment and initiation were higher for the full package compared to all other conditions except the recruitment call condition. Enrollment, initiation, and program completion were higher for the recruitment call and full package conditions compared to the EAU condition. In the subsample of initiators, parents in the full package condition attended fewer parenting sessions than in the EAU condition. Controlling for attendance across sessions, there were no condition effects on homework completion or in-session participation.

Conclusions:

The recruitment call can increase the public health impact of evidence-based parenting programs by improving enrollment, initiation, and program completion.

Keywords: Parenting, Randomized Controlled Trial, Effectiveness Research, Prevention

Children living in low-income, urban neighborhoods are often exposed to multiple risk factors for behavior problems (Lima, Caughy, Nettles, & O’Campo, 2010; Winslow & Shaw, 2007), such as poverty and community violence (Guerra, Huesmann & Spindler, 2003). Behavior problems typically begin in early elementary school, and often escalate into behavioral health problems in adolescence and adulthood (Dodge et al., 2009; Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2009). Evidence-based parenting programs decrease and even prevent behavior problems for children at-risk (e.g., Sandler, Ingram, Wolchik, Tein, & Winslow, 2015). Schools provide a way to reach almost all families, including those who are at risk but not already identified as needing intervention. Therefore, delivering parenting programs universally in elementary schools that serve at-risk students targets a critical developmental window to prevent the onset and escalation of behavior problems.

For parenting programs to have a public health impact, parents must engage in them. Initiation rates (i.e., attending at least one session) have been low (i.e., < 5% - 17%) in community settings (Fagan, Hanson, Hawkins, & Arthur, 2009; Sandler et al., 2019; Spoth, Clair, Greenberg, Redmond, & Shin, 2007). For example, in a community trial of the multi-level Triple P program, only 1% of parents engaged in the full program and less than 10% engaged in any program level (Prinz, Sanders, Shapiro, Whitaker, & Lutzker, 2009). In the Communities that Care trial, initiation rates ranged from 4% - 7% (Fagan et al., 2009).

Over the past 40 years, researchers have identified effective strategies to increase engagement in services and programs to have a greater public health impact (Becker, Boustani, Gellatly, & Chorpita, 2018). Engagement is a broad construct that can be operationalized along multiple dimensions, such as behavioral (e.g., attendance), relational (e.g., therapeutic alliance), and attitudinal (e.g., expectancies, motivation to change) (Becker et al., 2018; Pullmann et al., 2013). Engagement can also be conceptualized as a multiphasic process (Gonzalez, Morawska, & Haslam, 2018; Piotrowska et al., 2017). For example, with respect to the behavioral dimension of attendance, the initial engagement phase can be defined as the process of connecting to an intervention, including expressing interest, enrolling, and initiating (Gonzalez et al., 2018; Winslow et al., 2018). A person’s engagement level might change within and across phases as a result of reciprocal effects among engagement dimensions (e.g., relational -> attitudinal -> behavioral) (Bamberger, Coatsworth, Fosco, & Ram, 2014; Chacko et al., 2016). For example, a parent might initially express high interest in participating in a parenting program but drop out due to negative experiences in the program, such as negative interactions with the provider, group process, or cultural fit.

It is important to identify effective engagement strategies for each dimension and phase. Some engagement strategies are effective for multiple dimensions and phases (e.g., addressing interpersonal and logistical barriers), whereas others are relevant for specific dimensions and phases (e.g., provider monitoring for homework completion) (Becker et al., 2018; Lindsey et al., 2014). In this paper, we focused on testing strategies for increasing the initial phase of behavioral engagement in a group-based parenting program. Though engagement strategies for increasing attendance and treatment completion have been studied frequently, strategies for increasing initial behavioral engagement (i.e., enrollment and initiation) have been examined less often, especially for parenting programs (Chacko et al., 2016; Gonzalez et al., 2018).

Among families referred for child mental health problems, several strategies have been shown to be effective in increasing initiation, including appointment reminders; videos describing treatment and expectations; and brief interventions to clarify treatment goals, address barriers, and build a therapeutic alliance (Ingoldsby, 2010; Lefforge, Donohue, & Strada, 2007). However, engagement studies have rarely tested recruitment strategies for families who have not already been referred for services (Gonzalez et al., 2018). For parenting programs, recruitment is the least understood aspect of the engagement process (Chacko et al., 2016).

There have been only a few experimental studies of parenting program recruitment strategies (Gonzalez et al., 2018). Salarai and Backman (2016) discovered that a promotion-focused advertisement increased enrollment in a universal parenting program compared to a prevention-focused ad. Mian, Eisenhower, and Carter (2015) tested a package to recruit parents into a selective prevention program for children at risk for anxiety disorders. The package included: 1) matching session content and structure to parent needs; 2) a letter from an influential contact; and 3) a personalized phone call. The package significantly increased plans to attend but not attendance. Several researchers have tested the impact of monetary incentives on engagement, with disappointing results in most cases (Dumas, Begle, French, & Pearl, 2010; Gross et al., 2011; Heinrichs, 2006). In another randomized trial, multiple versions of a video to recruit divorcing parents into an evidence-based parenting program were tested (Winslow et al., 2018). Compared to an informational video, a video incorporating social influence principles significantly increased enrollment and initiation. In all conditions, there was a substantial drop off from initial interest to initiation, highlighting the need to develop engagement strategies to target that gap (i.e., the intention-behavior gap; Webb & Sheeran, 2006).

To address the intention-behavior gap, we developed a recruitment package designed to increase initial engagement behaviors (i.e., enrollment and initiation) and tested it in an efficacy trial (Winslow et al., 2016). The package had four strategies: informational brochure, testimonial booklet, teacher endorsement, and group leader recruitment call. The first strategy represented engagement as usual (EAU). The latter three were enhanced with effective practice elements from the engagement literature (e.g., expectation setting, rapport building, goal setting, and barrier problem solving) (Lindsey et al., 2014; Becker et al., 2018).

Multiple theories contributed to the package’s development, but the theory of planned behavior (TPB) was the main framework due to its strong links to engagement in health behaviors (McEachan, Conner, Taylor, & Lawton, 2011). The TPB posits three modifiable constructs that have been shown to predict behavioral engagement: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control. Individuals are likely to engage in a behavior, like participate in an intervention, if their beliefs are consistent with the behavior (attitudes), they perceive social pressure to do it (subjective norms), and think it would be easy to accomplish (perceived control) (Ajzen, 1991). See Winslow and colleagues (2016) for additional details about the package’s development process.

To test effects of recruitment package strategies on initial behavioral engagement, Winslow and colleagues (2016) conducted a school-based efficacy trial with Mexican origin families. The trial tested whether the full recruitment package increased enrollment and initiation into the Triple P group level 4 program (Sanders, Kirby, Tellegen, & Day, 2014) compared to a condition with an EAU brochure and an attention-control interview. Enrollment was high in both conditions and did not differ significantly. However, parents in the full package condition were more likely to initiate compared to those in the EAU + attention-control condition if their children had high baseline concentration problems (Winslow et al., 2016). Mediation analyses showed that the full package increased initiation through changes in perceived barriers, implementation intentions, and perceived control, providing support for its theory (Winslow, Mauricio, & Tein, 2017).

The purpose of the current study was to: 1) test the effectiveness of this recruitment package to increase initial behavioral engagement in an evidence-based parenting program, Triple P group level 4 (Sanders et al., 2014), when offered universally in a school-based setting and implemented by natural service providers; 2) dismantle the effects of the full package to identify the effective strategies; and 3) examine the effects of the strategies on initial engagement at the population level, controlling for recruitment into a research study. With respect to the first aim, recruitment package implementation was tightly monitored in the efficacy trial (Winslow et al., 2016). Innovations often fail to produce similar results under real-world conditions (Prochaska, Evers, Prochaska, Van Marter, & Johnson, 2007). Therefore, testing the recruitment package under natural service delivery conditions was crucial. In terms of the second aim, we examined which strategies were responsible for effects to guide dissemination efforts. Related to the third aim, participating in research and assessment affect participants’ behavior (Becker et al., 2018; Lindsey et al., 2014; McCambridge, Kypri, & Elbourne, 2014). Therefore, in addition to randomly assigning families to a Triple P recruitment condition, families were also randomly assigned either to be recruited for research surveys, gathering data on participant characteristics and outcomes, or not to be recruited for surveys but still receive the Triple P recruitment strategies to mimic real-world implementation. Intent-to-treat analyses were conducted at the population level. Population-level analyses, controlling for research survey condition, were implemented to enhance external validity so findings would be generalizable to the eligible population, rather than only to the sample of parents who participated in research surveys and recruitment strategies.

The current randomized controlled trial (RCT) used a dismantling design (West, Aiken, & Todd, 1993) to test the effects of the recruitment package. Parents were randomly assigned to one of five conditions: 1) EAU informational flyer; 2) EAU + testimonial booklet; 3) EAU + teacher endorsement; 4) EAU + recruitment call; and 5) full package of all four recruitment strategies. We hypothesized that: 1) the full package would increase enrollment and initiation compared to the other conditions; and 2) the experimental recruitment strategies (conditions 2–4) would be more effective at engaging parents than the EAU flyer strategy. Also, because participating in research and assessment have been linked to engagement outcomes, we hypothesized that being recruited for research surveys would increase initial engagement compared to parents who were not recruited for surveys.

Exploratory analyses were conducted with the whole, population-level sample to examine effects of recruitment strategies on program completion (i.e., attending at least 75% of parenting group sessions). Using the subsample of caregivers who initiated Triple P, we also conducted exploratory analyses on attendance over the course of group sessions, homework completion, and in-session participation. Since the package was developed specifically to impact initial engagement, and after initiation we used the same engagement strategies in all conditions (e.g., reminder calls; accessibility promotion), significant differences across conditions on post-initiation engagement behaviors were not expected. However, differences could occur in either direction. Parents who received experimental recruitment strategies could remain more motivated than those in the EAU flyer condition. On the other hand, if the experimental strategies boosted initiation in parents who otherwise might not have engaged, that effect might fade over time as parents regress to initial motivation levels (Spoth & Redmond, 1994).

Method

The study was conducted through three annual cohorts of data collection, implementation of Triple P recruitment strategies, and Triple P delivery. Data collection occurred in January through April 2015, 2016, and 2017. School program coordinators, group leaders, and teachers enrolled families. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Participants were caregivers of students attending one of five participating elementary schools in a large, urban school district in the southwest United States. Schools serving predominantly low-income families with similar demographics were selected to avoid confounding site with sociocultural factors.

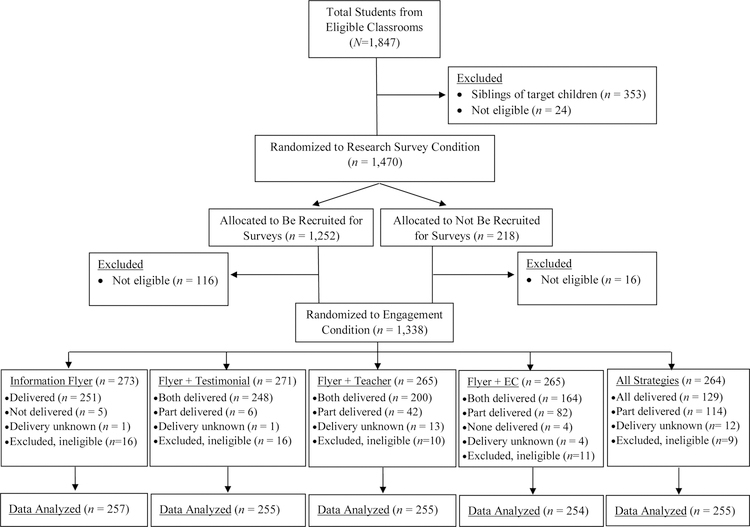

Inclusion criteria were that a family have a student in kindergarten, first, second, or third grade at a participating school. Families were considered ineligible and excluded from analyses if: 1) the caregiver(s) did not speak English or Spanish; 2) the target child was in a special education classroom; 3) a child in the family attended a participating school during a prior cohort; 4) the caregiver was a kindergarten-through-third-grade teacher at a participating school; 5) the caregiver was already enrolled in a parenting program at the participating school; 6) the target child did not have a caregiver (i.e., lived in a group home); or 7) the target child registered at the school after randomization to Triple P recruitment condition occurred or withdrew from the school before the Triple P program began. For families with multiple children in kindergarten through third grade, a target child was randomly chosen. As shown in Figure 1, there were 1,847 students in kindergarten through third grade in participating schools; 1,276 of whom were eligible and included in analyses. The sample size was selected for power greater than .8 to detect small effects for the hypothesized analyses, and small-to-medium effects for the exploratory analyses.

Figure 1.

Participant Flowchart

Note. Testimonial = testimonial booklet; Teacher = teacher endorsement; EC = engagement call.

Demographic information is not available for the whole sample because some caregivers did not participate in research surveys. However, at the aggregate level, the schools’ demographic characteristics were as follows: % free or reduced-price lunch eligibility (M = 84.8%; range = 78.1% - 90.2%), % single-parent households (M = 43.0%; range = 26.9% - 78.3%), % English as primary language (M = 65.2%; range = 58.6% - 75.5%), % Hispanic (M = 55.8%; range = 44.9% - 69.5%), % non-Hispanic White (M = 27.4%; range = 13.3% - 49.2%), % Native American (M = 7.2%; range 1% - 19.5%), and % African American (M = 6.5%; range = 0.8% - 10.6%).

Procedure

Principals recruited a staff member at each school to serve as the coordinator and enlisted school staff to be trained as Triple P group leaders. Because Triple P training was costly, to conserve resources in cohorts 2 and 3, group leaders included both school staff from newly participating schools and those who were trained as group leaders in prior cohorts. In some cases, there were not enough school staff available to fill all leader positions. In these cases (n = 7, 19% of leaders), the investigators recruited community behavioral health specialists trained as Triple P facilitators. School coordinators and group leaders were paid from the research grant for time spent in training, preparation, and implementation at the school district’s hourly rate for after-school programs. Investigators trained coordinators, teachers, and group leaders to implement Triple P recruitment strategies. The schools’ coordinators did the day-to-day monitoring of implementation. Investigators provided proactive technical assistance to coordinators, which is important for high quality implementation in natural delivery settings (Durlak & DuPre, 2008).

Randomization procedures

Because of concerns that conducting research surveys with caregivers might influence participation in Triple P, families were first randomized to a research survey condition--15% of families were randomized to not be recruited for research surveys and 85% of families were randomized to be recruited for research surveys (see Figure 1). Research survey participants were compensated for their time completing surveys: 1-hour pretest ($50), 30-minute post-recruitment ($25), 40-minute post-Triple P ($35). Second, families were randomly assigned to a Triple P recruitment condition, blocking on research survey condition, school, and classroom (for those assigned to be recruited for surveys) or grade level (for those assigned not to be recruited for surveys). Blocking on grade level for those assigned not be recruited for surveys was conducted because there were not enough cases to block on classroom. The research team used the SAS random number generator for the random allocation sequences.

Investigators and coordinators were not masked to conditions. Parents were aware of the recruitment strategies they received; however, they did not know strategies implemented in other conditions. Group leaders and teachers were not masked to the recruitment strategies they implemented, but they did not know details of other strategies.

Triple P Recruitment Strategies

EAU flyer.

In all conditions, teachers included a 1-page bilingual flyer that described the Triple P program and included an enrollment form in students’ take-home materials. Teachers reported delivering flyers to 98% of target children.

Testimonial booklets.

Testimonial booklets were 4-page bilingual booklets with photos and quotes from parents and children describing Triple P benefits and fun childcare activities along with an enrollment form. The photos and quotes were obtained from families who previously participated in Triple P. Coordinators mailed testimonial booklets in school envelopes to families randomized to receive them. The research grant paid for the costs of printing and mailing booklets. Coordinators reported mailing a testimonial booklet to 100% of families randomized to receive it. The post office returned 14 booklets (2.75%) to the school as undeliverable. These were sent home with students’ take-home materials.

Teacher endorsement.

Teachers recommended Triple P through brief (2–5 minutes), unscripted conversations during parent-teacher conferences (or through emails/notes if personal contacts were unsuccessful). Teachers briefly discussed Triple P and how it could help the target child, and encouraged parents to resolve barriers to attendance (if any were mentioned). Teachers also gave caregivers a Triple P brochure that included an enrollment form, and asked caregivers if they wanted to enroll. Teacher endorsement training involved a 2-hour meeting during which teachers learned about Triple P, its benefits, and procedures for recommending Triple P and reporting conversation details. Teachers practiced implementing endorsements through role plays. After cohort 1, three 15-minute meetings were added prior to the 2-hour training to provide teachers with in-depth knowledge of the Triple P parenting skills to help them better discuss the program. Endorsements were done with the caregiver(s) who attended the parent-teacher conference; in most cases, the target child’s mother (67% mother, 14% mother and father/other caregiver, 13% father, 6% another relation). Teachers reported conducting an endorsement with 84%, and partially conducting an endorsement (e.g., sending email/note/brochure home) with an additional 10%, of the families randomized to receive it. For the 6% of endorsements not completed, teachers reported the following reasons: no parent-teacher conference occurred (unclear why a message was not left) (n = 19, 62%); ran out of time (n = 4, 14%); teacher forgot (n = 3, 10%); teacher did not know to do it with this parent (n = 3, 10%); parent was too upset due to family emergency (n = 1, 3%).

Recruitment call.

Group leaders conducted a manualized, 20-minute call in which the leader provided information about Triple P, elicited the caregiver’s child- and parenting-focused goals, discussed how the goals could be addressed by Triple P, and helped the caregiver problem-solve barriers to attendance and create implementation intention plans for how to attend Triple P if a barrier arose. The group leader then asked if the caregiver wanted to enroll; and if so, completed an enrollment form with the caregiver. Group leaders were teachers, counselors, and teachers’ aides at participating schools; and in a few cases, community behavioral health specialists. Recruitment call training included four parts. First, group leaders completed a 2- to 3-hour, online course to become familiar with the call. Second, the group leaders participated in a 7-hour, group session to learn the call protocol and role-play with feedback. Third, group leaders completed 4 to 6 mock phone calls with parent actors followed by trainer feedback. Fourth, a 1.5-hour meeting occurred to review paperwork and equipment usage and answer remaining questions. Recruitment calls were conducted primarily with the child’s mother (83% mothers, 11% fathers, 6% another relation). Group leaders reported fully completing 65%, and partially completing an additional 12%, of calls to families randomized to receive them. For partially completed cases, the recruitment call started but the parent requested a call back and the group leader was unable to reach the parent again. For not completed cases, the group leader was unable to reach the parent because the parent did not answer or did not have a valid phone number.

Triple P implementation

The Triple P group level 4 program (Sanders et al., 2014) was offered universally to all families with a kindergarten through third grade student at participating schools. The Triple P program included eight weekly sessions with parents. Sessions 1 to 4 were 2-hour, group sessions during which parents learned Triple P skills. Sessions 5 to 7 were optional, individual, 20-minute phone sessions with the group leader to hone skills. Session 8 was a 20-minute phone session to celebrate accomplishments and plan future skill use. The group sessions were delivered at schools. Caregivers were offered a choice of English- or Spanish-speaking groups and two different times (week night or after-school). Group leaders were trained by Triple P America’s 3-day training and a 1-day pre-accreditation workshop conducted by a professional Triple P trainer. Group leaders were also required to pass accreditation requirements at a 1-day follow-up session. Group leaders attended weekly peer supervision meetings, which were led by the schools’ coordinators. Groups were typically led by a single group leader (80%). Groups of 18 or more parents were led by two group leaders.

Triple P retention strategies

The following best practice accessibility promotion strategies were used in all conditions: delivering Triple P at a convenient location (i.e., school); meeting at convenient time(s) (i.e., evenings, after school); matching parents and staff on language; providing free childcare, snacks, and drinks; sending confirmation letters and session reminders; and dispensing appointment calendars at session 1 (Becker et al., 2018). Coordinators mailed confirmation letters to all enrolled caregivers approximately 1–2 weeks prior to the first Triple P session. Automated reminders (calls, texts, and/or emails) about the upcoming session and associated homework were sent using the schools’ existing parent communication system or an equivalent web-based tool. A reminder was sent one week and again one day before the first session. After session one, weekly reminders were sent to enrolled families two days before the session. Reminders ceased for families who told the group leader they would no longer attend. Reminders also ceased for enrollees who did not attend either of the first two sessions, based on Triple P recommendations not to encourage parents who miss initial sessions to start the program late due to missing critical program content and possible disruptions in group cohesion (Turner, Markie-Dadds, & Sanders, 2010). However, parents were not terminated from the study or Triple P, regardless of the number of missed sessions.

Measures

Enrollment

Enrollment was a dichotomous dependent variable indicating whether or not anyone in the family signed up for Triple P via any enrollment method. Caregivers enrolled in Triple P by completing a form, which was included with all recruitment strategies. Caregivers returned enrollment forms to teachers through students’ take-home folders, in-person, or by completing one via phone with a group leader or the coordinator. In rare cases, caregivers enrolled at the first Triple P session. Teachers and group leaders gave completed enrollment forms to coordinators who entered them into a software program provided by the investigators.

Attendance variables

Initiation was a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not any caregiver attended at least one group session. Program completion was a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not at least 3 of 4 group sessions were attended by any caregiver in the family. Attendance over the course of the program was the total number of group sessions (0 to 4) attended by any caregiver in the family. Attendance at optional phone sessions was not included.

Homework

Caregivers completed homework completion reports at the beginning of each subsequent session (sessions 2 to 8). The mean number of homework assignments completed for group sessions was used to assess homework completion. When more than one caregiver per family attended Triple P, the homework data for the caregiver who attended the most sessions were used. If multiple caregivers in a family attended equally, data were used for the caregiver who participated in Triple P recruitment strategies, if applicable; or if not applicable, one caregiver’s data was randomly chosen to be used in analyses. Homework completion has predicted positive parent training outcomes, including improvements on parenting skills and child behavior, controlling for attendance (e.g., Clarke et al., 2015).

After each session, group leaders completed ratings of each caregiver’s in-session participation using Dumas, Nissley-Tsiopinis, and Moreland’s (2007) 1-item measure, “Overall, how well did the parent participate during the session?”, which was rated on a 5-point scale. Higher scores on this measure have predicted improvements in child and parenting outcomes pre-post parenting intervention (Begle & Dumas, 2011). When Triple P groups were led by two group leaders (20% of groups), ratings (r = .55, p < .001) were averaged. A mean across group sessions was calculated for each caregiver. When multiple caregivers per family attended, one caregiver’s data were used in analyses as described in the homework paragraph.

Research survey condition

Research survey condition was a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not the family was randomized to be recruited for research surveys in addition to receiving the Triple P recruitment condition to which they were assigned.

Triple P recruitment condition

Dummy coded (0, 1) variables were created for each of the five recruitment conditions indicating whether or not the family was randomized to that condition.

Data Analytic Approach

Chi-square analyses tested for baseline differences on enrollment and initiation rates by the school attended and the target child’s grade level. We also tested interactions between recruitment conditions and school-level variables (i.e., primary student language, percent Hispanic, percent White, percent free/reduced lunch, total students). We did not find any significant differences, so no additional covariates or school-level moderators were included.

There were multiple instances of clustering. Families were clustered within teachers in classrooms for all analyses. The families in the recruitment call and full package conditions were also clustered within the group leader who conducted the call. The families that attended the Triple P sessions were clustered within the group leader who led the parenting group. Because we were interested in individual effects rather than group effects, we accounted for the cluster effects and adjusted standard errors using the sandwich estimator (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). It was not feasible to control for all clustering effects due to software limitations, so we controlled for the cluster variable with the highest intraclass correlation (ICC) for a given dependent variable. ICCs ranged from .003 to .316. For enrollment, initiation, program completion, and attendance across sessions, we controlled for the recruitment call clustering variable, which had ICCs of .157, .147, .107, and .131, respectively. For homework completion, we controlled for the clustering effects of classroom teacher, which had an ICC of .207; and for in-session participation, we controlled for the Triple P group attended, which had an ICC of .316.

We used Mplus (Version 8, Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) for all analyses. Intent-to- treat analyses were used. Specifically, all eligible participants randomized to conditions were included in analyses. There were no missing data for dependent variables. An alpha of .05 based on the one-tail test was used for testing significance of the a priori hypotheses.

To test the hypothesis that being recruited for research surveys would increase behavioral engagement, survey condition was used as a predictor in all models. To test the dismantling hypothesis that the full package would increase enrollment and initiation compared to other conditions, logistic regression analyses were conducted using the full package condition as the reference group. The independent variables were dummy coded (0, 1) variables for each of the other four recruitment conditions. We reported the odds ratios (ORs) associated with the regression coefficients [i.e., OR = exp(b)]. Depending on the reference group, the OR can be > 1 (the reference group has a higher rate of enrollment/initiation than the comparison group) or < 1 (the reference group has a lower rate of enrollment/initiation than the comparison group). To test the hypothesis that experimental recruitment strategies increased enrollment and initiation relative to the EAU flyer, logistic regression analyses were conducted using the EAU flyer condition as the reference group.

Using the EAU flyer condition as the reference group, we also conducted exploratory analyses to examine possible effects of the experimental recruitment conditions at the population level on program completion; and among initiators of Triple P, we examined attendance across sessions, in-session participation, and homework completion. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to test the effects of experimental recruitment strategies on program completion. To explore whether the experimental recruitment strategies had effects beyond initiation, the attendance across sessions analyses included only caregivers who initiated Triple P. Zero-inflated Poisson regression analyses were conducted to account for the large number of zero values of those who never attended. Zero-inflated Poisson regression produces two sets of analyses. One set predicted the effects of condition on non-initiation, and the other set used Poisson regression to predict attendance across sessions among caregivers who initiated. Finally, multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to test the effects of experimental recruitment strategies on homework completion and in-session participation, controlling for attendance.

Results

Table 1 presents enrollment, initiation, and program completion rates for the whole sample by Triple P recruitment and research survey conditions. We used Chen, Cohen and Chen’s (2010) method for calculating effect sizes from ORs: small = 1.52 OR, medium = 2.74 OR, and large = 4.72 OR for analyses with the EAU flyer as the reference group. For analyses with the full package as the reference group, we expected comparison conditions to have lower engagement rates (i.e., ORs < 1) with effect sizes as follows: small = .66 OR, medium = .36 OR, and large = .21 OR.

Table 1.

Engagement rates for the whole sample by Triple P recruitment and research survey conditions.

| Triple P Recruitment Condition | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 257) | 2 (n = 255) | 3 (n = 255) | 4 (n = 254) | 5 (n = 255) | ||||||

| Survey | No Survey | Survey | No Survey | Survey | No Survey | Survey | No Survey | Survey | No Survey | |

| n = 218 | n = 39 | n = 216 | n = 39 | n = 216 | n = 39 | n = 217 | n = 37 | n = 215 | n = 40 | |

| Variables | ||||||||||

| % Enrolled | 12 | 5 | 12 | 10 | 20 | 28 | 42 | 32 | 41 | 30 |

| n | 26 | 2 | 26 | 4 | 44 | 11 | 91 | 12 | 88 | 12 |

| % Initiated | 11 | 3 | 11 | 8 | 13 | 15 | 25 | 22 | 27 | 18 |

| n | 23 | 1 | 23 | 3 | 28 | 6 | 54 | 8 | 58 | 7 |

| % Completed | 9 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 11 | 13 | 19 | 11 | 20 | 5 |

| n | 20 | 1 | 21 | 1 | 23 | 5 | 42 | 4 | 42 | 2 |

Note. 1 = Engagement-as-usual (EAU) flyer condition, 2 = EAU + testimonial booklet condition, 3 = EAU + teacher endorsement condition, 4 = EAU + recruitment call condition, 5 = full package condition.

Effects of the full recruitment package

Compared to the full package, enrollment rates were significantly lower for the EAU flyer (OR = .19, 95% CI = .113 to .313), testimonial booklet (OR = .21, 95% CI= .126 to .336), and teacher endorsement conditions (OR = .43, 95% CI = .275 to .651). There was no significant difference in enrollment rates between the package and the recruitment call condition. Initiation rates were also significantly lower in the EAU flyer (OR = .30, 95% CI = 171 to .532), testimonial booklet (OR = .33, 95% CI = .190 to .571), and teacher endorsement conditions (OR = .45, 95% CI = .265 to .763) compared to the full package condition. There was no significant difference in initiation rates between the full package and recruitment call condition. Effect sizes were in the medium-to-large range.

Effects of experimental recruitment strategies compared to EAU flyer

Compared to the EAU flyer, enrollment rates were significantly higher in the teacher endorsement (OR = 2.25, 95% CI = 1.377 to 3.669), recruitment call (OR = 5.58, 95% CI = 3.290 to 9.480), and full package (OR = 5.30, 95% CI = 3.191 to 8.843) conditions. Initiation rates were significantly higher than the EAU flyer only in the recruitment call (OR = 3.14, 95% CI = 1.737 to 5.629) and full package (OR = 3.33, 95% CI = 1.881 to 5.862) conditions. The recruitment call produced significantly higher rates of enrollment (OR = 2.48, 95% CI = 1.552 to 3.961) and initiation (OR = 2.10, 95% CI = 1.226 to 3.590) compared to the teacher endorsement. Effect sizes were in the medium-to-large range.

Exploratory analyses

When the whole, intent-to-treat, population-level sample was utilized, program completion rates were higher for the recruitment call (OR = 2.49, 95% CI = 1.383 to 4.482, B = .91, SE = .31, t = 2.96, standardized coefficient (β) = .19, p = .003) and full package (OR = 2.36, 95% CI = 1.547 to 3.609, B = .86, SE = .30, t = 2.88, β = .18, p = .004) conditions compared to the EAU flyer condition. Effect sizes were medium. Neither the testimonial booklet nor the teacher endorsement conditions increased program completion compared to the EAU flyer.

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics on attendance across sessions, homework completion, and in-session participation for Triple P initiators. When using only the sample of parents who initiated Triple P, those in the full package attended significantly fewer group sessions (B = −.18, SE = .09, t = −2.09, β = −.61, p = .036) compared to initiators in the EAU flyer condition. The effect size was large (Cohen, 1988). There were no significant effects on attendance across sessions among initiators for the other conditions compared to the EAU flyer. Controlling for attendance across sessions, there were no significant differences for any of the recruitment conditions on homework completion or in-session participation.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics on engagement variables among initiators by recruitment condition.

| Triple P Recruitment Condition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | 1 (n = 24) | 2 (n = 26) | 3 (n = 34) | 4 (n = 62) | 5 (n = 65) |

| Attendance M (SD) | 3.50 (.93) | 3.46 (.95) | 3.29 (.97) | 3.23 (.98) | 2.95 (1.11) |

| Homework M (SD) | .67 (.24) | .62 (.20) | .59 (.27) | .59 (.28) | .59 (.29) |

| Participation M (SD) | 4.49 (.43) | 4.41 (.44) | 4.27 (.51) | 4.42 (.63) | 4.36 (.59) |

Note. Participation = in-session participation; 1 = Engagement-as-usual (EAU) flyer condition, 2 = EAU + testimonial booklet condition, 3 = EAU + teacher endorsement condition, 4 = EAU + recruitment call condition, 5 = full package condition.

Research survey condition

Research survey condition was not significantly related to enrollment or initiation. In the condition that was randomized to be recruited for research surveys, 25% enrolled and 17% initiated, compared to 21% and 13%, respectively, in the condition that was randomized not to be recruited. However, there were effects of research survey condition on program completion for the whole sample and attendance across sessions for initiators. Parents assigned to be recruited for research surveys were more likely to complete the program than those assigned not to be recruited (OR = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.217 to 4.071, B = .80, SE = .31, t = 2.60, β = .15, p = .009). Of the sample of parents who initiated Triple P, those who had been assigned to be recruited for research surveys attended more group sessions (M = 3.29, SD = .96) than those assigned not to be recruited (M = 2.64, SD = 1.29; B = .27, SE = .13, t = 2.19, β = .82, p = .029). Being recruited for research surveys had a large effect on attendance among initiators and a small effect on program completion in the whole sample.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to test the effectiveness of experimental recruitment strategies, implemented by natural service providers, for increasing initial behavioral engagement into the Triple P parenting program when offered universally in elementary schools serving at-risk students. We hypothesized that the full package would increase enrollment and initiation compared to the other four conditions, and that the experimental recruitment strategies would be more effective than the EAU flyer. We conducted exploratory analyses on program completion with the whole, population-level sample. With the subsample of parents who initiated Triple P, we conducted exploratory analyses on attendance across sessions, homework completion, and in-session participation. Finally, we assessed whether being recruited for research surveys increased initial engagement.

Effects of the full recruitment package

Results supported our primary hypothesis that the full package would increase initial behavioral engagement compared to the other conditions with one exception. The package did not increase engagement significantly more than the EAU + recruitment call condition, which doubled enrollment and initiation rates. These findings suggest that the recruitment call can provide an efficient, effective way to increase initial behavioral engagement into parenting programs. The recruitment call was effective for a specific engagement phase that has been understudied in the parenting program literature, recruitment of families not already referred for services (Chacko et al., 2016; Gonzalez et al., 2018). Our findings are consistent with other studies that have found that brief, preparatory enhancement strategies, such as pretreatment interviews to set goals and reduce attendance barriers, can increase initial behavioral engagement in child mental health treatment (Ingoldsby, 2010; Nock & Ferriter, 2005).

Comparison of experimental recruitment strategies to the EAU flyer

We expected that experimental recruitment strategies would be more effective than the EAU informational flyer because these strategies contained effective practice elements that have been identified in the engagement literature (e.g., expectation setting, rapport building, goal setting, barrier problem solving) (Lindsey et al., 2014; Becker et al., 2018). We found partial support for this hypothesis. We did not find evidence that the testimonial booklet increased engagement compared to the EAU flyer. However, the teacher endorsement and recruitment call strategies produced higher enrollment than the EAU flyer, and the recruitment call produced higher initiation. Further, the recruitment call produced higher enrollment and initiation rates compared to the teacher endorsement.

There were several differences that may explain why the testimonial booklet was not significantly better than the EAU flyer, and the recruitment call was more effective than the teacher endorsement strategy. Although all testimonial booklets were delivered to caregivers, the amount of exposure caregivers had to the testimonial booklets is unclear--caregivers may or may not have read the booklets thoroughly or at all. The recruitment call targeted multiple constructs (i.e., parent attitudes, obstacles, planning, social influence, efficacy, salience) linked to behavioral engagement in interventions/health behaviors (Becker et al., 2018; Lindsey et al., 2014; McEachan et al., 2011; Winslow et al., 2016), whereas the testimonial booklet and teacher endorsement targeted fewer of these constructs. Attitudes play a central role in engagement behavior (Becker et al., 2015), and caregivers in the recruitment call conditions received more components targeting attitudes.

The recruitment call was also longer than the teacher endorsement. Nock and Ferriter (2005) suggested that engagement strategies might need to be more intensive to be effective with parents who are not seeking services. Compared to the 2- to 5-minute teacher endorsement, the in-depth discussion during the 20-minute call allowed caregivers to receive a higher dose of effective components, such as brainstorming and problem-solving barriers and creating implementation intentions. This format provided more opportunities for the call components to change parent attitudes related to attendance.

In addition, the recruitment call protocol was more structured and the training was more intensive than the teacher endorsement, both of which might have led to higher implementation fidelity for the call compared to the endorsement. Setting and implementer differences could have also impacted effects. The teacher endorsement was typically conducted during a parent-teacher conference. The format aligned with teachers’ schedules, but created competing discussion topics, and teachers may have been less invested because they were not group leaders. In contrast, the sole focus of the recruitment call was helping parents see a match between their values and the program and to problem solve barriers to attendance. Also, group leaders may have been motivated to engage families because they led the Triple P program.

Finally, people are likely to be influenced to engage in a behavior if recommended by someone they like (Cialdini, 2009). Caregivers may have had prior interactions with the teacher and/or group leader that impacted their receptivity to recruitment strategies in either positive or negative ways, depending on the nature of those prior interactions and relationships. In addition, some caregivers may have felt uncomfortable saying “no” to their child’s teacher even though they did not plan to attend, which could have artificially inflated the enrollment rate in the teacher endorsement condition.

Exploratory Findings

In line with the results of the main hypotheses, exploratory analyses using the population-level sample showed that the full package and EAU flyer + recruitment call conditions produced higher completion rates than the EAU flyer condition. This is encouraging given that other studies focused on engagement in universal parenting programs have not reported effects on program completion (Gonzalez et al., 2018).

In contrast to the program completion analyses, which used the whole sample, analyses on attendance across sessions examined effects of experimental recruitment strategies after program initiation using the subsample of parents who initiated. Given that the recruitment call and full package did not increase attendance across sessions compared to the EAU flyer, we conclude that their effects on program completion were due to increasing enrollment and initiation. Substantially more parents enrolled and initiated in the recruitment call and full package conditions compared to the EAU flyer condition, and these increases resulted in more parents completing the program. Thus, the recruitment call and the full package have the potential to increase the public health impact of evidence-based parenting programs by increasing enrollment, initiation, and consequently program completion.

The exploratory findings related to attendance across sessions were unexpected; parents who initiated Triple P in the full package condition attended significantly fewer sessions than those in the EAU flyer condition. Initiators in the full package condition may have had high motivation due to repeated exposure to experimental recruitment strategies compared to the other conditions. Their high motivation may have diminished, especially if they were less motivated at baseline compared to those who initiated after only receiving a flyer (Spoth & Redmond, 1994). Although caregivers in the EAU flyer condition rarely initiated, those who did may have been especially self-motivated to attend.

In contrast to the full package, the recruitment call did not differ significantly from the EAU flyer condition on attendance across sessions. This is encouraging given results suggest disseminating the recruitment call and flyer rather than the full package. Moreover, the full package did increase initiation more than the EAU flyer condition, so although some parents dropped out, the package still resulted in higher numbers of parents completing the program when compared to the flyer. In addition, attendance levels after initiation were relatively high in all conditions, so the decrease in the full package condition may not be clinically meaningful. In all conditions, we used best practice accessibility strategies (e.g., multiple days/times, missed session calls) (Becker et al., 2018) that could account for the good attendance of initiators.

Research Survey Effects

Parents randomly assigned to be recruited for research surveys were more likely to complete Triple P in the whole sample, and had higher attendance across sessions in the initiator subsample, compared to those who were not recruited for surveys. Participating in research impacts participants’ behaviors (McCambridge, Witton, & Elbourne, 2014). Perhaps, parents committed to the program because they knew they would be interviewed at the end and/or because they were being paid for survey participation. Another explanation could be that completing surveys with an interviewer could have impacted engagement behaviors through factors like rapport. Skilled survey interviews can be similar to therapy assessment interviews, which have been positively linked to engagement dimensions (Becker et al., 2018; Lindsey et al., 2014).

Increasing the Impact of Parenting Programs Using the Recruitment Call

One objective of the study was to test whether or not the experimental recruitment strategies would be effective when delivered by trained school staff/community members. We found strong support, with effect sizes in the medium-to-large range, that program enrollment, initiation, and completion rates were increased by the recruitment call. A second objective was to identify the recruitment strategies responsible for the effects of the full package under real-world conditions. Results clearly demonstrated that the recruitment call strategy was responsible for the package’s effectiveness, as it significantly increased enrollment, initiation, and program completion at the population-level significantly better than the other strategies, and there were no significant additive effects of the full package compared to the recruitment call condition. Importantly, after controlling for research survey condition, recruitment call effects on enrollment, initiation, and program completion remained; which suggests that the recruitment call exerted unique effects on engagement behaviors.

Having an effective recruitment strategy that can be disseminated to community providers is an initial step toward increasing the population-level impact of parenting programs. The current findings fill gaps in the engagement literature by identifying strategies useful for recruiting parents into interventions offered universally. Though experimental studies have tested methods to engage parents into child mental health treatment, including parenting interventions (Chacko et al., 2016; Ingoldsby, 2010); RCTs focused on testing recruitment strategies that can be used with all parents, not just those already referred for treatment, have been rare (Gonzalez et al., 2018). The few experimental studies on engagement into universal parenting programs have typically only impacted one engagement stage (e.g., enrollment) (Gonzalez et al., 2018). In contrast, the recruitment call led to higher enrollment, initiation, and program completion rates, providing support for the recruitment call as an effective approach for the initial phase of behavioral engagement.

An advantage of the recruitment call is that it could be adapted for any parenting program from the prenatal period to adolescence and could be used across multiple intervention levels (i.e., universal, selective, indicated, treatment) and settings (e.g., schools, courts) to increase the public health impact of evidence-based parenting interventions. It could also be adapted for other types of interventions. Thus, it is a highly versatile recruitment strategy.

Population-Level Rates

The enrollment, initiation, and program completion rates reported in this study represent population-level engagement rates. Thus, although the initiation rate for the recruitment call condition (24%) seems low, this rate reflects the true population-level initiation rate (i.e., percentage who initiated from the total sampling pool of eligible participants). Higher rates are often reported when only a portion of the sampling pool is considered (i.e., families who participated in a research study relative to the sample of interested/contacted participants) (Spoth et al., 2007). Using the interested/contacted sample overestimates true population participation rates. Self-selected samples may not represent the population, limiting generalizability (Spoth et al., 2007).

Strengths and Limitations

The current study built on the literature in two key ways. First, the study was the first RCT to dismantle the effects of an efficacious, multi-strategy recruitment package for engaging parents into a parenting program offered universally in schools. Identifying the recruitment call as the active ingredient can provide community settings with information on how to conduct efficient and effective recruitment. Second, it was the first study to compare different recruitment methods at the population-level with families not referred or seeking services, in an ethnically diverse and high-risk population. Our findings showed that population-level, initial engagement rates can be increased through a recruitment call delivered by school staff.

The recruitment call has several important strengths. First, as discussed previously, the recruitment call is a highly versatile, manualized strategy that could be adapted for use with a variety of interventions, intervention levels, and settings. Second, the call could dramatically increase the reach of evidence-based programs like Triple P by increasing enrollment, initiation and consequently program completion. Reach has been a critical barrier to realizing the public health impact of evidence-based interventions (Glasgow, Lichtenstein, & Marcus, 2003). The recruitment call can improve initial engagement as one piece of the answer to this problem.

Though the study has many strengths, it also has limitations. The study design confounded recruitment strategy format with content. For example, the EAU flyer provided basic program information, but there was no condition in which a person delivered basic information in the absence of other recruitment strategies. Similarly, there was no flyer that helped parents set goals for their family and problem solve attendance barriers. The recruitment strategies also differed in resource-intensiveness, and we did not compare their cost effectiveness. The EAU flyer was the easiest to implement. The recruitment call was the most time-consuming and challenging to implement. The teacher endorsement required some training, but was easier to implement than recruitment calls because it was unscripted and integrated into parent-teacher interactions.

Though the recruitment call was the most effective strategy, it does not solve the problem of engaging “hard to reach” families without reliable phone service. Moreover, even though our initiation rate of 24% was higher than rates reported in other population-based studies (Fagan et al., 2009; Prinz et al., 2009; Sandler et al., 2019; Spoth et al., 2007), most parents did not initially engage. Though it is probably unrealistic to expect all parents to engage when interventions are offered to all families, some of whom are functioning well, there is still room for improvement. Also, increasing enrollment, initiation, and program completion does not ensure that families will benefit from parenting interventions, because they must actively participate in meaningful ways (i.e., learn, practice, and feel efficacious with new skills) to improve child outcomes (Berkel et al., 2018).

Future Directions

In future work, we will examine how recruitment strategy implementation impacted initial behavioral engagement. Given that 43% of parents assigned to the full package condition received only part of the strategies (see Figure 1), it will be important to test whether those who received the full package differed compared to those who received part of the package. For the recruitment call strategy, it will be important to examine predictors of call completion to identify ways to improve rates. In addition, we will examine the impact of parent reports of exposure and appeal of each experimental recruitment strategy, as well as implementer and observational ratings of fidelity and quality, on initial behavioral engagement.

We will also examine if the recruitment strategies had differential effects as a function of sociocultural factors and baseline child behavior problems, which have predicted behavioral engagement in prior studies (Chacko et al., 2016; Ingoldsby et al., 2010). In the efficacy trial, the recruitment package increased behavioral engagement of low-SES, highly acculturated, Mexican origin parents, as well as parents of children with high teacher-reported behavior problems (Winslow et al., 2016). The current work did not examine these potential moderators because we do not have these individual-level data for all families. In future work using the survey subsample, we will be able to examine these, as well as other important variables related to behavioral engagement, such as attitudinal (e.g., motivation to change, perceived benefits and barriers) and relational (e.g., parent report of teachers and Triple P leaders as influential referents) factors (Becker et al., 2018; Lindsey et al., 2014).

In addition, future research should compare the cost effectiveness of the recruitment strategies, and whether the call can be delivered in a less expensive manner (e.g., web-based). We will also test whether the effectiveness of the teacher endorsement could be increased by integrating components of the recruitment call into the endorsement, given that the endorsement was more feasible than the call to implement.

Finally, initial behavioral engagement is important because families must enroll and initiate programs to benefit from them. However, attendance alone does not lead to positive child and family outcomes (Berkel et al., 2018). Thus, in our future work, we will test strategies for engagement post-initiation, especially understudied variables such as homework completion and in-session participation (Chacko et al, 2016). Engagement is multidimensional, including attitudinal, relational, and behavioral elements interacting within a social context (Becker et al., 2018). Because attitudinal and relational engagement has been understudied (Becker et al., 2018; Pullmann et al., 2013), we will also identify engagement strategies that target and impact these domains in future work.

Summary

This study was the first to dismantle the effects of a recruitment package on population- level behavioral engagement rates as part of an effectiveness trial in which recruitment strategies were delivered under naturalistic conditions. The call led to higher rates of parent enrollment and initiation and ultimately doubled the program completion rate. Results showed that the recruitment call was an effective, initial step toward increasing the public health impact of evidence-based parenting programs. Next steps are to assess implementation factors predicting initial engagement, test moderators of recruitment strategy effects, and examine attitudinal and relational factors that might explain non-engagement in the recruitment call conditions. In the engagement literature broadly, more research is needed on post-initiation engagement strategies to increase attitudinal, relational, and behavioral (e.g., homework completion, in-session participation) engagement. Purveyors of evidence-based parenting programs would be wise to add training on evidence-based recruitment strategies to their intervention packages to increase population-level engagement rates and consequently the public health impact of their interventions.

Table 3.

Effects of Triple P recruitment condition on enrollment and initiation.

| Enrollment | Initiation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions | b (SE) | t value | p value | b (SE) | t value | p value |

| Full Package (reference) | ||||||

| Research Survey Condition | .26 (.25) | 1.05 | .294 | .35 (.22) | 1.61 | .108 |

| EAU Informational Flyer | −1.67 (.26) | −6.45 | .000 | −1.20 (.29) | −4.20 | .000 |

| EAU + Testimonial Booklet | −1.58 (.25) | −6.22 | .000 | −1.11 (.28) | −3.93 | .000 |

| EAU + Teacher Endorsement | −.86 (.22) | −3.82 | .000 | −.80 (.27) | −3.02 | .003 |

| EAU + Recruitment Call | .05 (.18) | .30 | .763 | −.06 (.17) | −.36 | .720 |

| EAU Flyer (reference) | ||||||

| Research Survey Condition | .26 (.25) | 1.05 | .294 | .35 (.22) | 1.61 | .108 |

| EAU + Testimonial Booklet | .09 (.28) | .31 | .755 | .10 (.30) | .33 | .743 |

| EAU + Teacher Endorsement | .81 (.25) | 3.22 | .001 | .40 (.28) | 1.42 | .155 |

| EAU + Recruitment Call | 1.72 (.27) | 6.33 | .000 | 1.14 (.30) | 3.88 | .000 |

| Full Package | 1.67 (.26) | 6.45 | .000 | 1.20 (.29) | 4.20 | .000 |

Note. EAU = Engagement-as-usual.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse through a research grant to the second author (R01 DA033352), and an institutional training grant supporting the first author (T32DA039772). The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. We thank the principals, staff, and parents in the Mesa Unified School District for partnering with us.

Footnotes

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Ajzen I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and the Human Decision Process, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger K, Coatsworth JD, Fosco G, & Ram N. (2014). Change in participant engagement during a family-based preventive intervention: Ups and downs with time and tension. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(6), 811–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Boustani MM, Gellatly R, & Chorpita BF. (2018). Forty years of engagement research in children’s mental health services: Multidimensional measurement and practice elements. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47, 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Lee BR, Daleiden EL, Lindsey M, Brandt NE, & Chorpita BF. (2015). The common elements of engagement in children’s mental health services: Which elements for which outcomes?. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44, 30–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begle AM, & Dumas JE. (2011). Child and parental outcomes following involvement in a preventive intervention: Efficacy of the PACE program. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 32, 67–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Brown CH, Gallo CG, Chiapa A, … & Jones S. (2018). “Home Practice Is the Program”: Parents’ practice of program skills as predictors of outcomes in the New Beginnings Program effectiveness trial. Prevention Science, 19, 663–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko A, Jensen SA, Lowry LS, Cornwell M, Chimklis A, Chan E,…& Pulgarin B. (2016). Engagement in behavioral parent training: Review of the literature and implications for practice. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19, 204–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Cohen P, & Chen S. (2010). How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Communications in Statistics—Simulation and Computation®, 39, 860–864. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB. (2009). Influence: Science and practice (5th ed.). New York: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A, Marshall S, Mautone J, Soffer S, Jones H, Costigan T, Patterson A, Jawad A, & Power T. (2015). Parent attendance and homework adherence predict response to a family-school intervention for children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44, 58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analyses for the behavioral sciences. (2nd ed.), New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Malone P, Lansford JE, Miller S, Petit G, & Bates JE. (2009). A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-use onset. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 74, 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Begle AM, French B, & Pearl A. (2010). Effects of monetary incentives on engagement in the PACE parenting program. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39, 302 –313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Nissley-Tsiopinis J, & Moreland AD. (2007). From intent to enrollment, attendance, and participation in preventive parenting groups. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, & DuPre EP. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 327–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA, Hanson K, Hawkins JD, & Arthur MW. (2009). Translational research in action: implementation of the communities that care prevention system in 12 communities. Journal of Community Psychology, 37, 809–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, & Horwood LJ. (2009). Situational and generalised conduct problems and later life outcomes: Evidence from a New Zealand birth cohort. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 1084–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, & Marcus AC. (2003). Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 1261–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Morawska A, & Haslam DM. (2018). Enhancing initial parental engagement in interventions for parents of young children: A systematic review of experimental studies. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21, 415–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Johnson T, Ridge A, Garvey C, Julion W, Treysman A, Breitenstein S, & Fogg L. (2011). Cost-effectiveness of childcare discounts on parent participation in preventive parent training in low-income communities. Journal of Primary Prevention, 32, 283–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Huesmann LR, & Spindler A. (2003). Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children. Child Development, 74, 1561–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs N. (2006). The effects of two different incentives on recruitment rates of families into a prevention program. Journal of Primary Prevention, 27, 345–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby E. (2010). Review of interventions to improve family engagement and retention in parent and child mental health programs. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 629–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefforge NL, Donohue B, & Strada MJ. (2007). Improving session attendance in mental health and substance abuse settings: a review of controlled studies. Behavior Therapy, 38, 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima J, Caughy M, Nettles SM, & O’Campo PJ. (2010). Effects of cumulative risk on behavioral and psychological well-being in first grade: Moderation by neighborhood context. Social Science & Medicine, 71, 1447–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey MA, Brandt NE, Becker KD, Lee BR, Barth RP, Daleiden EL, & Chorpita BF. (2014). Identifying the common elements of treatment engagement interventions in children’s mental health services. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17, 283–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J, Kypri K, & Elbourne D. (2014). Research participation effects: a skeleton in the methodological cupboard. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67, 845–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J, Witton J, & Elbourne DR. (2014). Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: new concepts are needed to study research participation effects. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67, 267–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachan R, Conner M, Taylor N, & Lawton R. (2011). Prospective prediction of health-related behaviors with the Theory of Planned Behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 5, 97–144. [Google Scholar]

- Mian ND, Eisenhower AS, & Carter AS. (2015). Targeted prevention of childhood anxiety: Engaging parents in an underserved community. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55, 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L,& Muthén B. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nock M, & Ferriter C. (2005). Parent management of attendance and adherence in child and adolescent therapy: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8(2), 149–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowska PJ, Tully LA, Lenroot R, Kimonis E, Hawes D, Moul C, et al. (2017). Mothers, fathers, and parental systems: A conceptual model of parental engagement in programmes for child mental health—Connect, Attend, Participate, Enact (CAPE). Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20, 146–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz R, Sanders M, Shapiro C, Whitaker D, & Lutzker J. (2009). Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P System Population Trial. Prevention Science, 10, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Evers KE, Prochaska JM, Van Marter D, & Johnson JL. (2007). Efficacy and effectiveness trials. Journal of Health Psychology, 12, 170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullmann M, Ague S, Johnson T, Lane S, Beaver K, Jetton E, & Rund E. (2013). Defining engagement in adolescent substance abuse treatment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52, 347–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari R, & Backman A. (2016). Direct marketing of parenting programs: Comparing a promotion-focused and a prevention-focused strategy. European Journal of Public Health, 27, 489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR, Kirby JN, Tellegen CL, & Day JJ. (2014). The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A systematic review and meta- analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clinical Psychology Review, 34, 337–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, Ingram A, Wolchik S, Tein JY, & Winslow EB. (2015). Long-term effects of parenting-focused preventive interventions to promote resilience of children and adolescents. Child Development Perspectives, 9, 164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, Wolchik S. Mazza G, Gunn H, Tein JY, Berkel C, Jones S, & Porter M. (2019). Randomized effectiveness trial of the New Beginnings Program for divorced families with children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 00, 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Clair S, Greenberg M, Redmond C, & Shin C. (2007). Toward dissemination of evidence-based family interventions: Maintenance of community-based partnership recruitment results and associated factors. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 137–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, & Redmond C. (1994). Effective recruitment of parents into family-focused prevention research: A comparison of two strategies. Psychology & Health, 9, 353 –370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner K, Markie-Dadds C, & Sanders M. (2010). Facilitator’s Manual for Group Triple P (Ed. III). Milton QLD, Australia: Triple P International Pty Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Webb TL, & Sheeran P. (2006). Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 249–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Aiken LS, & Todd M. (1993). Probing the effects of individual components in multiple component prevention programs. American Journal of Community Psychology, 21, 571–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow EB, Braver S, Cialdini R, Sandler I, Betkowski J, Tein JY, … & Lopez M. (2018). Video-based approach to engaging parents into a preventive parenting intervention for divorcing families: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science, 19, 674–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow EB, Mauricio AM, & Tein JY. (2017, May). Impacting engagement in preventive parenting programs: A multiphasic process. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Winslow EB, Poloskov E, Begay R, Tein JY, Sandler I, & Wolchik S. (2016). A randomized trial of methods to engage Mexican American parents into a school-based parenting intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84, 1094–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow EB, & Shaw DS. (2007). Impact of neighborhood disadvantage on overt behavior problems during early childhood. Aggressive Behavior, 33, 207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]