Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications are used by increasing numbers of reproductive-aged women. Findings from studies exploring the safety of these medications during pregnancy are mixed, and it is unclear whether associations reflect causal effects or could be partially or fully explained by other factors that differ between exposed and unexposed offspring.

OBJECTIVES:

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the adverse pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes associated with exposure to prescribed ADHD medication during pregnancy, with a focus on how studies to date have handled the influence of confounding.

METHODS:

We searched PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and Web of Science up to July 1st, 2019, without any restrictions on language or date of publication. We included all observational studies (e.g. cohort studies, case control studies, case-crossover studies, cross-sectional studies, and registry-based studies) with pregnant women of any age or from any setting who were prescribed ADHD medications and evaluated any outcome, including both short- and long-term maternal and offspring outcomes. Two independent authors then used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) to rate the quality of the included studies.

RESULTS:

Eight cohort studies that estimated adverse pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes associated with exposure to ADHD medication during pregnancy were included in the qualitative review. There were substantial methodological differences across the included studies regarding data sources, type of medications examined, definitions of studied pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes, types of control groups, and confounding adjustment. There was no convincing evidence for teratogenic effects according to the relative risk of pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes, and the observed differences in absolute risks were overall small in magnitude. Inadequate adjustment for confounding existed in most studies, and none of the included studies adjusted for ADHD severity in the mothers.

CONCLUSION:

The available data are too limited to make an unequivocal recommendation regarding the use of ADHD medication during pregnancy. Therefore, physicians should weigh whether the advantages of using ADHD medication outweigh the potential risks for the developing fetus according to the different situation of each particular woman. Future research should attempt to triangulate research findings based on a combination of different designs that differ in their underlying strengths and limitations and should investigate specific confounding factors, the potential impact of timing of exposure, and potential long-term outcomes in the offspring.

1. Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder affecting 5% of children and adolescents and about 2.5% of adults worldwide, and it is well established that impairing ADHD persists into adolescence and adulthood in many individuals [1, 2]. In particular, girls with ADHD in childhood have a substantial likelihood of continuing to be diagnosed with ADHD also in adulthood [3, 4]. Meta-analytic evidence from double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs) shows that stimulant ADHD medications are highly, and non-stimulants moderately, efficacious in the short term to reduce the core symptoms of ADHD in children, adolescents, and adults [5]. As with all medication and some non-pharmacological approaches, ADHD medications may be associated with adverse events, which in the majority of cases can be managed without stopping the medication when effective [6]. The most recent ADHD treatment guideline was written by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE 2018) in the UK [7]. This guideline recommends methylphenidate as the first-line treatment, lisdexamfetamine or other amphetamines as second line treatment, and atomoxetine or guanfacine (both non-stimulant medications) as third-line treatments for school-aged children and adolescents. In adults, methylphenidate or lisdexamfetamine (or other amphetamines) and atomoxetine are recommended as first- and second- line treatment, respectively. To our knowledge, there are no specific recommendations for adults with ADHD in the US.

Appropriate treatment for ADHD is an important public health issue, as the disorder is associated with high rates of psychiatric [8, 9] and somatic [10, 11] comorbidity, as well as increased risk for poor educational, occupational, and social outcomes [8, 12, 13]. A recent large, population-based study using prescription databases from 13 countries and one Special Administrative Region identified a sharp increase in ADHD medication prescriptions during the last decade, though there was substantial variability across countries [14]. Previous research has also found that the prescribing prevalence of ADHD medication has increased more rapidly among adults than among children and adolescents [15, 16], particularly in women [17]. A growing number of women, therefore, enter their reproductive years treated with medication for ADHD or are diagnosed and start medication during their reproductive years.

Given these trends, there is a need to accurately understand the potential effects of maternal pharmacotherapy during pregnancy on pregnancy-related outcomes and offspring development. This need is particularly salient given the historical context of research on prenatal stimulant exposure. Amidst a period of increased cocaine (an illicit stimulant) use in the 1980’s in the US, preliminary research showing adverse birth outcomes led to dire predictions regarding the medical, behavioral, and social outcomes of the so-called crack babies [18–21]. Subsequent research would, however, show that such predictions were largely unfounded, as infants, children, and adolescents prenatally exposed to cocaine have ultimately demonstrated comparable physical development and cognitive and academic outcomes to similar non-exposed youth [20, 22–24]. Studies that observed differences (e.g., behavioral and cognitive problems) have generally indicated that potential causal effects of stimulant exposure are modest in magnitude [25, 26]. This broader historical context highlights that the current limited research on ADHD pharmacotherapy in pregnancy needs to be carefully reviewed in detail.

Fetal exposure to common ADHD medications in animals has shown limited evidence of adverse effects at or below the equivalent maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) on a mg/m2 basis. In mice, methylphenidate has been shown to pass the placenta with ensuing pharmacologically significant concentrations in the fetal brain [27]. Additionally, mice exposed to 5 mg/kg methylphenidate in utero had decreased anxiety-related behaviors and increased impulsivity and compulsivity [28, 29]. However, gestational exposure to methylphenidate in rats and rabbits at or below the MRHD have not demonstrated significant adverse effects in the exposed fetuses [30–32]. In contrast, pregnant rabbits given methylphenidate at 40 times the MRHD has shown increased incidence of fetal spina bifida [32]. In pregnant rats given 7 times the MRHD of methylphenidate, increased incidences of fetal skeletal variations and maternal toxicity was observed, and rats exposed to 4 times the MRHD had offspring with decreased body weight gain [32]. Additionally, offspring to pregnant rats treated with twice the MRHD during gestation displayed elevated expression of dopamine markers in the brain, and decreased preference and motivation for sucrose [33]. Similar to methylphenidate, amphetamines have also been shown to pass the placenta in mice [34], and exposure to amphetamines in mice during gestation at doses 41 times the MRHD has shown embryotoxic and teratogenic effects [35]. Yet, no embryotoxic or teratogenic effects was observed in rabbits given the drug in doses 7 times the human dose [36], nor in rats given 12.5 times the MRHD [37]. Atomoxetine and its metabolites have been shown to pass the placenta in pregnant rats, although with substantially less exposure in fetal tissue compared to maternal tissue [38]. According to unpublished data, atomoxetine at a dose approximately 23 times the MRHD has been observed to reduce the rate of live births and increase resorption [39]. Thus, the existing animal literature suggests stimulant and nonstimulant ADHD medication well above MRHD is associated with adverse outcomes, but at doses equivalent to MRHD relatively few adverse effects have been documented.

In humans, observational studies have provided some information regarding the safety of ADHD medication use during pregnancy. The pooled estimates from a recent meta-analysis [40] of eight cohort studies demonstrated that exposure to ADHD medication during pregnancy was associated with elevated risk of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission but not for other adverse pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes. However, it is important to consider whether these findings could reflect a causal effect of prenatal ADHD medication exposure or alternatively reflect systematic differences between exposed and unexposed pregnancies. In particular, observational treatment studies need to account for confounding by indication, that is, patients who are medicated are usually more symptomatic and with comorbid conditions than those who are not on medication. Therefore, patients exposed and unexposed to a particular intervention or treatment might not be comparable, limiting the ability to draw causal inference. Providing a clear and comprehensive covariate selection is necessary for a better interpretation of the results from observational studies [41]. As a consequence, it is important to evaluate the extent to which available observation studies have adjusted for the relevant confounders to block confounding by indication.

We could not find any specific clinical guidelines regarding ADHD medication use during pregnancy. The general guidance on the use of psychotropics in pregnancy from the British Association of Psychopharmacology (BAP) [42] highlights that there are limited data on the safety of ADHD medications used in the perinatal period. The BAP recommends that the decision as to whether medication should be continued during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and the choice of medication, should be based on the general principles of the guidance. Therefore, there is a need for high-quality evidence to support guidelines for ADHD medication use during pregnancy.

In the current paper, we reviewed observational studies exploring associations of prescribed ADHD medication in pregnancy with pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes. To contribute to such evidence, this systematic review aimed to extend the previous meta-analysis [40] in four important ways. First, the present study appraised and synthesized the available evidence on the safety of ADHD medication use during pregnancy by using qualitative methods, with a focus on methodological considerations. Given the substantial heterogeneity across included studies regarding data sources, types of medications examined, definitions of pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes, and types of control groups, the results from the previous meta-analysis should be interpreted with great caution. Second, although the previous meta-analysis highlighted substantial variation in confounding adjustment across studies, we compared the confounding control strategies across studies and discuss the potential influences of confounding on the pooled estimates (e.g., confounding by indication via maternal ADHD). Third, we report absolute risks of outcomes (e.g., by calculating risk differences), which is important for a better understanding of the real-world population-effects of ADHD medications, instead of solely reporting relative risks. Finally, we highlight and discuss limitations related to control of potential confounders and provide directions for future studies to address these limitations, given the potential that confounding factors (whether measured, unmeasured, or unknown) bias the estimates from observational studies.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection of Studies

We applied the standard methodological guidelines of the PRISMA (the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) statement [43]. We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and Web of Science using a pre-specified search strategy to identify all studies on humans published up to July 1st, 2019, evaluating associations with ADHD medication use during pregnancy. Detailed information on the search terms and syntax for each database are reported in Table S1. We did not impose any restrictions on language or date of publication. Two authors (LL and AS) also searched references of selected papers to retrieve any possible additional pertinent publications that could have been missed with the electronic search.

We included all pertinent observational studies on humans, including cohort studies, case control studies, case-crossover studies, cross-sectional studies, and registry-based studies; studies including pregnant women of any age or from any setting; and studies evaluating any outcome, including both short- and long-term maternal and offspring outcomes. We excluded studies focused on illicit medication use, as well as reviews, books, guidelines, and case reports.

2.2. Data Extraction

The authors LL and AS extracted the data from the studies. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or, when necessary, by a third reviewer (HL). LL and AS extracted the following data from each study for the qualitative synthesis: name of the first author; publication year; study country; data source and sample size; information on the main exposure, including specific ADHD medications, source of information, exposure window; information on exposure to other medications during pregnancy; outcomes assessed; information on confounder adjustment, including specific measured covariates included and the use of methods to adjust for unmeasured confounding; absolute risk difference; and main conclusion. Wang and colleagues [44] identified three types of data sources -- including administrative database/registry, ad hoc disease registry and ad hoc clinical sample.

2.3. Assessment of study quality

The authors LL and AS used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [45] to independently rate the quality of the included studies, and the initial discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The NOS is a validated tool for evaluating the quality of observational studies and includes three categories to evaluate studies – selection (definition/representativeness of exposed subjects, selection of non-exposed subjects), comparability (controls or adjustment for confounding factors), and outcome (assessment of outcome, adequate non-response rate or follow-up time). A higher score on the NOS represents a higher quality study, and the maximum score a study can receive is 9.

3. Results

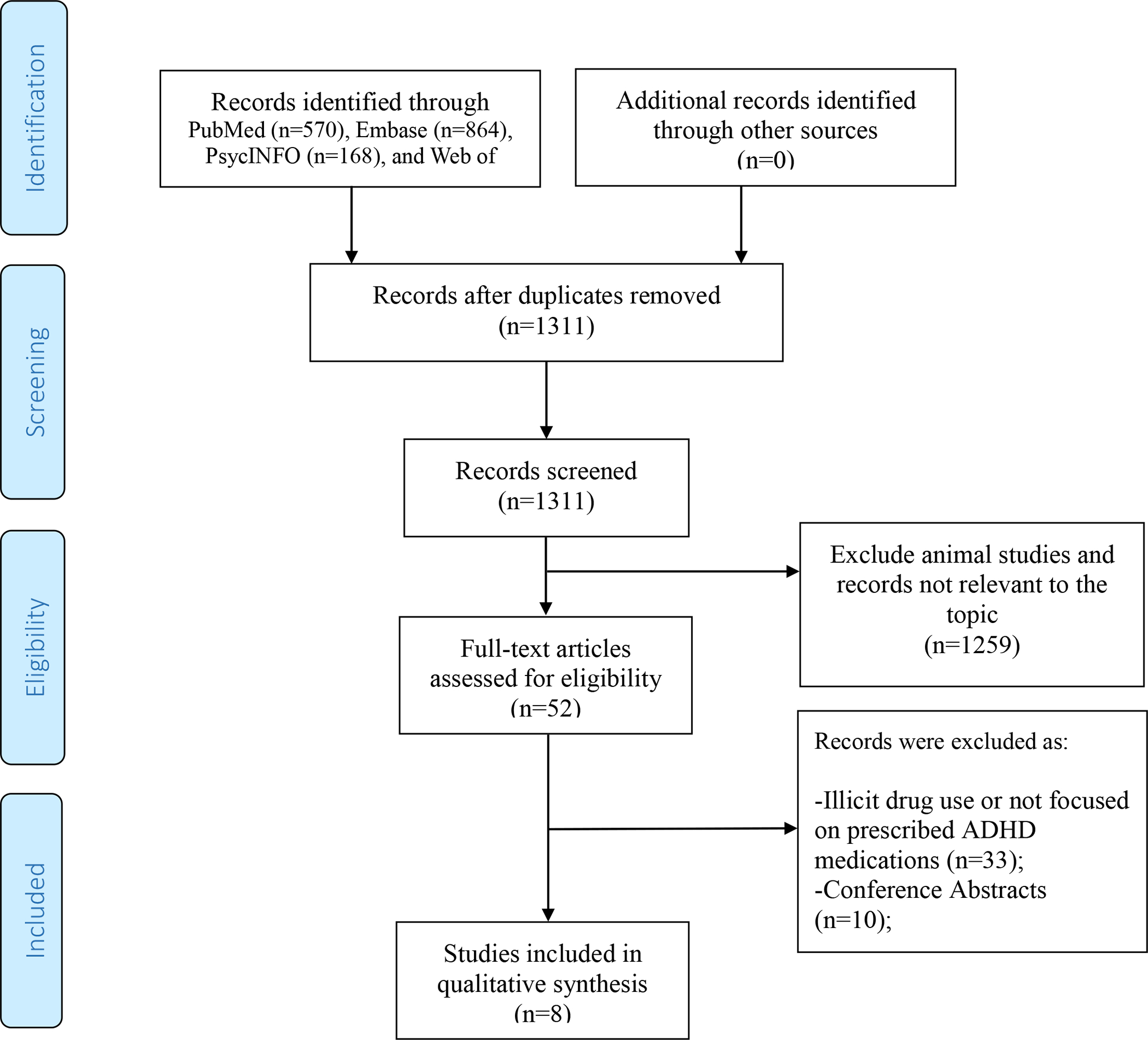

Figure 1 shows the study selection process. Table S2 in the supplement presents a list of all excluded studies with reasons for exclusion. After removing duplicate records, LL and AS screened a total of 1,311 records by reviewing titles and abstracts. LL and AS removed 1,259 because they were not relevant and then evaluated the full-text articles of the remaining 52 records in detail. Ultimately, our qualitative review included eight published research studies based on original data [46–53].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for inclusion of the studies examining the association between ADHD medication use during pregnancy and outcomes in the offspring.

PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses.

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the eight included studies. All were cohort studies, conducted across several countries: Denmark, Israel, Germany, England, Canada, the United States, Sweden and Australia. Of the eight studies, seven (87.5%) obtained data from an administrative database/registry [46, 47, 49–53] and one (12.5%) obtained data from an ad hoc clinical sample [48]. Therefore, administrative databases/registries comprising large numbers of participants were the most commonly used data source for the studied associations. Of note, no research has studied ADHD medication use during pregnancy in developing countries. All studies analyzed relatively large samples, ranging from approximately 700 to 2 million offspring. The exposure definitions varied across studies, and the prevalence of exposure ranged between 0.004% and 0.58%. The studies examined a variety of ADHD medications, including amphetamine, atomoxetine, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, methylphenidate, and modafinil. Six studies defined exposure using prescription records[46, 47, 49, 50, 52, 53], one study defined expose according to maternal reports of medication use[48], and one study defined exposure according to prescription records or maternal reports [51]. Five studies focused on exposure occurring anytime during pregnancy [46, 48, 49, 51, 53], and three studies focused on exposure occurring early in pregnancy only [47, 50, 52]. None of the identified studies to date thus evaluated exposure later in pregnancy specifically, nor did they consider variation in dosage or duration of exposure.

Table 1.

Overview of cohort studies included in the systematic review

| Study | Country | Data source and sample size | Exposure | Co-medicine in different exposure groups | Adjusted for confounders | Outcomes | Main conclusion | NOS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs(N) | Measurement | Time window | Exposure during pregnancy | Exposure before/after pregnancy | Non-exposure | Measured | Unmeasured | ||||||

| Haervig et al, 2014[49] | Denmark | Administrative Database/Registry; 1,054,494 | MPH:393 (0.04%) Modafinil: 45(0.004%) ATX:42 (0.004%) |

Redeemed prescriptions recorded in the National Prescription Registry | 28 days before the first day of LMP to end of pregnancy | Anxiety medicine: 27 (5.5%) SSRI:104 (21.7%) |

NA | Anxiety medicine: 7,591 (0.7%) SSRI: 21,129 (2.0%) |

Age, region, ethnicity | Compared exposed pregnancies to unexposed pregnancies of the same woman to account for unchanged factors between pregnancies: gene, early-life exposure | Abortion Miscarriage Stillbirth Congenital malformations |

ADHD medication in pregnancy was associated with different indicators of maternal disadvantage and with increased risk of induced abortion and miscarriage | 8 |

| Pottegard et al, 2014[52] | Denmark | Administrative Database/Registry; 2,442 | MPH: 222 (9.09%) | Redeemed prescriptions recorded in the National Prescription Registry | 14 days before the beginning of the first trimester up to the end of the first trimester | Antipsychotics: 20 (9.0%) Antidepressants: 76 (34.2%) Anxiolytics: 6 (2.7%) NSAIDs:14 (6.3%) |

NA | Antipsychotics: 139 (6.3%) Antidepressants: 768 (34.6%) Anxiolytics: 58 (2.6%) NSAIDs: 139 (6.3%) |

Maternal age, smoking status, body mass index, length of education, calendar year of completion of pregnancy, concomitant use of antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and NSAIDs | NA | Major malformations Cardiac malformations |

First-trimester MPH exposure does not appear to be associated with a substantial increased risk of major congenital malformations | 7 |

| Bro et al, 2015[46] | Denmark | Administrative Database/Registry; 989,932 | MPH/ATX:186 (0.02%) | Redeemed prescriptions recorded in the National Prescription Registry | For spontaneous abortion, the exposure window spanned from 30 days before the estimated day

of conception until the day prior to abortion or gestational age. For live births and stillbirths, the exposure window spanned from 30 days before the estimated day of conception until the day prior to birth. |

Anti psychotics: 17 (9.1%) Antidepressants: 57 (30.6%) Antiepileptics: 7 (3.8%) |

NA | Anti psychotics: 25 (9.1%) Antidepressants: 35 (12.7%) Antiepileptics: 10 (3.6%) |

Maternal age, smoking, parity, education, cohabitation, comorbidity and comedication | Compared to women diagnosed with ADHD who did not take MPH/ATX | Spontaneous abortion Birth weight Gestational age Small for gestational age Low birth weight Apgar score < 10 |

MPH/ATX was associated with a higher risk of SA, but results indicated that it may at least partly be explained by confounding by indication. Treatment with MPH/ATX was however associated with low Apgar scores, an association not found among women with ADHD who did not use MPH/ATX. | 9 |

| Diav-Citrin et al, 2016[48] | Israel, Germany, England, Canada | Ad Hoc Clinical Sample; 764 | MPH:382 (50%) | Structured questionnaire administered to women who contacted teratology information services before outcome of pregnancy was known. | Conception to the end of pregnancy | NA | NA | NA | Maternal age, gestational age, year at initial contact | NA | Major congenital anomalies Miscarriages and elective termination of pregnancy Preterm birth |

MPH does not seem to increase the risk for major malformations. Further studies are required to establish its pregnancy safety and possible associations with miscarriages. | 5 |

| Cohen et al, 2017[47] | United States | Administrative Database/Registry; 1,466,792 | Amphetamine/Dextroamphetamine:3331 (0.23%) MPH:1515 (0.10%) ATX: 453(0.03%) |

Medicaid insurance prescription records | LMP to LMP plus 140 days | Atypical antipsychotic: 18,080 (1.2%) Antidepressant: 138,074 (9.5%) Benzodiazepine: 45,483 (3.1%) Opioid: 323,505 (22.1%) Triptan: 16,202 (1.1%) NSAID: 244,501 (16.7%) Acetaminophen: 389,759 (26.7%) Anticonvulsant or lithium: 18,186 (1.2%) |

NA | Atypical antipsychotic: 876 (16.5%) Antidepressant: 2,639 (49.8%) Benzodiazepine: 1,063 (20.1%) Opioid: 2,140 (40.4%) Triptan: 184 (3.5%) NSAID: 1,290 (24.3%) Acetaminophen: 2,240 (42.3%) Anticonvulsant or lithium: 680 (12.8%) |

Demographic characteristics maternal and pregnancy characteristics, certain chronic conditions, indications for stimulants, other psychiatric and pain conditions, proxies for health care utilization intensity, and cotreatment with psychiatric and pain medication. | ATX used as a negative control exposure (ATX is a non-stimulant ADHD medication) | Preeclampsia placental abruption small for gestational age preterm birth | Psychostimulant use during pregnancy was associated with a small increased relative risk of preeclampsia and preterm birth. The absolute increases in risks are small and, thus, women with significant ADHD should not be counseled to suspend their ADHD treatment based on these findings. | 9 |

| Nörby et al, 2017[51] | Sweden | Administrative Database/Registry; 964,734 | MPH/Amphetamine/Dexamphetamine/Lisdexamfetamine/Modafini/ATX: 1591 (0.2%) | Self-reported use recorded in the Medical Birth Register or filled prescription recorded in the Prescribed Drug Register | one month before pregnancy to the end of pregnancy | Opioids: 15.0% Antiepileptics: 9.7% Psycholeptics: 34.9% Antidepressants: 31.8% Alimemazine: 4.1% Promethazine: 28.1% |

Opioids: 12.1% Antiepileptics: 3.2% Psycholeptics: 15.1% Antidepressants: 20.0% Alimemazine: 1.3% Promethazine: 18.6% |

Opioids: 4.4% Antiepileptics: 0.5% Psycholeptics: 2.3% Antidepressants: 3.3% Alimemazine: 0.1% Promethazine: 7.7% |

Year of birth, maternal age, primiparity, BMI, maternal smoking, noncabitating with father, mother born outside the Nordic countries, and maternal use of opioids, antiepileptics, psycholeptics, antidepressants alimemazine, or promethazine during pregnancy | Compared to ADHD medication use before or after pregnancy | Gestational age Small for gestational age Large for gestational age Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes Birth defects Perinatal death NICU admission Respiratory disorders Hyperbilirubinemia Hypoglycemia Feeding difficulties CNS-related disorders Withdrawal symptoms for therapeutic drugs |

Treatment with ADHD medication during pregnancy was associated with a higher risk for neonatal morbidity, especially central nervous system-related disorders such as seizures. Because of large differences in background characteristics between treatment women and controls, it is uncertain to what extend this can be explained by the ADHD medication per se. | 8 |

| Huybrechts et al, 2018[50] | United States, Nordic countries | Administrative Database/Registry; 1,813,894 | MPH:2072 (0.11%) Amphetamine/Dextroamphetamine: 5571 (0.31%) |

Medicaid insurance prescription records | First 90 days of pregnancy |

MPH exposed Anticonvulsants: 302 (14.6%) Antidepressants: 1,033 (49.9%) Anxiolytics: 43 (2.1%) Antipsychotics: 375 (18.1%) Barbiturates: 39 (1.9%) Benzodiazepines:336 (16.2%) Other hypnotics: 245 (11.8%) Amphetamine/dextroamphetamine exposed Anticonvulsants: 833 (15.0%) Antidepressants: 2,537 (45.5%) Anxiolytics: 128 (2.3%) Antipsychotics: 749 (13.4%) Barbiturates: 130 (2.3%) Benzodiazepines:1,315 (23.6%) Other hypnotics: 678 (12.2%) |

NA | Anticonvulsants: 35,644 (2.0%) Antidepressants: 155,155 (8.6%) Anxiolytics: 7,187 (0.4%) Antipsychotics: 22,661 (1.3%) Barbiturates: 18,023 (1.0%) Benzodiazepines: 54,893 (3.1%) Other hypnotics: 63,265 (3.5%) |

Demographic characteristics, obstetric characteristics, psychiatric conditions, chronic comorbid medical conditions, markers of general comorbidity, and prescribed medications. | NA | Major congenital malformations Cardiac malformations |

Findings suggest a small increase in the risk of cardiac malformations associated with intrauterine exposure to methylphenidate but not to amphetamines. This information is important when weighing the risks and benefits of alternative treatment strategies for ADHD disorders in women of reproductive age and during early pregnancy. | |

| Poulton et al, 2018[53] | Australia | Administrative Database/Registry; 30,305 | MPH/Dextroamphetamine 175 (0.58% for ADHD medication) | Prescription records recording in the Pharmaceutical Drugs of Addiction System | One year before the expected delivery date | NA | NA | NA | Maternal age, infant year of birth, pre-existing diabetes mellitus, pre-existing hypertension, smoking, parity and multiple pregnancy | Compared to women treated before or after pregnancy | Gestational diabetes Instrumental vaginal delivery Postpartum hemorrhage Birthweight < 2500g Birthweight > 4000 5-min Apgar < 7 Perinatal death Spontaneous labor onset Cesarean delivery Active resuscitation Neonatal admission > 4hours Pre-eclampsia Preterm birth 1-min Apgar < 7 |

Compared with no treatment, ADHD stimulant treatment at any time was associated with small increases in the risk of some adverse pregnancy outcomes; treatment before, or before and during pregnancy, was associated with additional adverse outcomes, even after a treatment-free period of several years. None of these associations can be confidently attributed to stimulant treatment; in all cases ADHD per se or correlates of it could be responsible for the association. | 8 |

MPH: Methylphenidate

ATX: Atomoxetine

LMP: last menstrual period

SSRI: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor

NSAID: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

ADHD: Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

BMI: Body Mass Index

NA: No information

NICU: Neonatal intensive care unit

NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

SA: Spontaneous abortion

All studies accounted for confounding by adjusting for a number of measured characteristics. These characteristics varied widely across studies but included calendar year, pregnancy characteristics (e.g., parity), socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., age, region, ethnicity, educations), proxies for maternal health care utilization, maternal mental and physical health (e.g., psychiatric conditions, body mass index), maternal substance use (e.g., alcohol and nicotine), and maternal co-occurring medication use (see Table 2). Of particular importance, only one measured confounder was considered across all of the included studies (i.e., maternal age), and no study included maternal ADHD severity as a measured covariate.

Table 2.

Confounders and risk factors evaluated in studies of included studies

| Variables | Haervig et al, 2014[49] | Pottegard et al, 2014[52] | Bro et al, 2015[46] | Diav-Citrin et al, 2016[48] | Cohen et al, 2017[47] | Nörby et al, 2017[51] | Huybrechts et al, 2018[50] | Poulton et al, 2018[53] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Region | × | × | × | |||||

| Ethnicity | × | × | × | × | ||||

| Education | × | × | ||||||

| Body Mass Index, BMI | × | × | × | |||||

| Cohabitation | × | × | ||||||

| Year of conception | × | |||||||

| Year of delivery | × | × | × | |||||

| Year at initial contact | × | |||||||

| Gestational age | × | |||||||

| Parity/multiparty | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Multifetal pregnancy | × | × | × | |||||

| Smoking status | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Alcohol use | × | |||||||

| Other drug abuse or dependence | × | × | ||||||

| Psychiatric conditions | × | × | × | |||||

| Chronic comorbid medical conditions | × | × | × | × | ||||

| Marker of general comorbidity | × | × | ||||||

| Prescribed medications/co-medications | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Proxies for health care utilization intensity | × |

Five out of eight studies used alternative comparisons groups in addition to comparing exposed pregnancies to unexposed pregnancies in order to rule out the influence of confounding [46, 47, 49, 51, 53]. Specifically, Haervig et al. compared exposed pregnancies to unexposed pregnancies of the same woman (i.e., sibling comparison) [49]; Bro and colleagues compared mothers who had ADHD and were prescribed ADHD medications to mothers who had ADHD but were not prescribed ADHD medications [46]; Cohen et al. compared pregnancies exposed to stimulant ADHD medications to pregnancies exposed to atomoxetine (a non-stimulant ADHD medication) [47]; and, Nörby and colleagues compared pregnancies with prescribed ADHD medication during pregnancy to those with prescribed ADHD medication before or after pregnancy only[51]; Poulton et al. compared pregnancies with prescribed ADHD medication exposure before, during or after pregnancy to unexposed pregnancies [53].

The retained studies evaluated associations with a wide variety of pregnancy outcomes, including pregnancy losses (miscarriages, stillbirths), pregnancy complications (e.g., preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, postpartum hemorrhage), and birth and neonatal outcomes (e.g., perinatal death, congenital malformations, birth weight, gestational age, Apgar score) (Table 1). No study evaluated associations with long-term outcomes.

The risk differences (RDs) (i.e. difference in risk of an adverse outcome between an exposed group and an unexposed group) of pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes in the ADHD medication-exposed group versus the reference group are described in Table 3. The RDs for pregnancy complications, congenital malformations, and labor and delivery outcomes were overall small in magnitude, with the range of 0.03% for cardiovascular malformation to 9.84% for NICU admission (mean ± standard deviation (sd): 2.07% ± 2.33%). The relative high risk for NICU admission might present a combination of the risk for a variety of pregnancy-related adverse outcomes, including preterm birth, low birth weight, birth defects or have a health condition that needs special care [54, 55]. The RDs were even smaller in the five studies [46, 47, 49, 51, 53] that used alternative comparisons groups order to rule out the influence of unmeasured confounding (e.g., unexposed siblings). In these studies, the range of RDs was 0.01% for major malformation to 3.90% for caesarean delivery (mean±sd: 0.97% ± 1.02%).

Table 3.

Risk difference (RD) of maternal and neonatal outcomes in the ADHD medication-exposed group versus the reference group

| Study | None exposure (A) | Exposure during pregnancy (B) | Alternative comparison groups (C) | RD (B minus A) | RD (C minus A) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Number with outcome(n,%) | N | Number with outcome(n,%) | N | Number with outcome(n,%) | ||||

| Pregnancy complications | |||||||||

| Preeclampsia | Cohen et al, 2017 [47] | 1461493 | 54467(3.73%) | 4846 | 256(5.28%) | 453 | 22(4.86%)a | 1.55% | 1.13% |

| Poulton et al, 2018 [53] | 25,249 | 1509(5.98%) | 175 | 13(7.43%) | 4881 | 311(6.37%)b | 1.45% | 0.39% | |

| Diabetes | Poulton et al, 2018 [53] | 25,249 | 817(3.24%) | 175 | 4(2.29%) | 4881 | 122(2.50%)b | −0.95% | −0.74% |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | Poulton et al, 2018 [53] | 10749 | 169(1.57%) | 78 | 2(2.56%) | 2073 | 35(1.69%)b | 0.99% | 0.12% |

| Placental abruption | Cohen et al, 2017 [47] | 1461493 | 20676(1.41%) | 4846 | 88(1.82%) | 453 | 11(2.42%)a | 0.41% | 1.01% |

| Labour and delivery outcomes | |||||||||

| Spontaneous abortion | Haervig et al, 2014 [49] | 1054014 | 114389(10.86%) | 480 | 54(11.25%) | 706 | 83 (11.76%)c | 0. 39% | 0.90% |

| Bro et al, 2015 [46] | 989471 | 114672(11.59%) | 186 | 18(9.67%) | 275 | 26(9.45%)d | −1.92% | −2.14% | |

| Diav-Citrin et al, 2016 [48] | 382 | 27(7.07%) | 383 | 54(14.10) | - | - | 7.03% | - | |

| Instrumental vaginal delivery | Poulton et al, 2018 [53] | 25225 | 3677(14.57%) | 175 | 31(17.71%) | 4878 | 692(14.19%)b | 3.14% | −0.38% |

| Caesarean delivery | Poulton et al, 2018 [53] | 25237 | 5564(22.04%) | 175 | 52(29.71%) | 4880 | 1266(25.94%) b | 7.67% | 3.90% |

| Active neonatal resuscitation | Poulton et al, 2018 [53] | 20750 | 1683(8.11%) | 159 | 21(13.21%) | 3992 | 394(9.87%) b | 5.10% | 1.76% |

| Preterm birth/gestational age | Bro et al, 2015 [46] | 989471 | 34211(3.46%) | 186 | 3(1.61%) | 275 | 10(3.64%)d | −1.85% | 0.18% |

| Diav-Citrin et al, 2016 [48] | 343 | 23(6.71%) | 293 | 26(8.87%) | - | - | 2.16% | - | |

| Cohen et al, 2017 [47] | 1461493 | 163772(11.21%) | 4846 | 635(13.10%) | 453 | 56(12.36%)a | 1.89% | 1.15% | |

| Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 52182(5.47%) | 1591 | 144(9.05%) | 9475 | 682(7.20%)e | 3.58% | 1.73% | |

| Poulton et al, 2018 [53] | 25245 | 1832(7.26%) | 175 | 19(10.86%) | 4880 | 403(8.26%)b | 3.60% | 1.00% | |

| Low birth weight | Bro et al, 2015 [46] | 989471 | 23691(2.39%) | 186 | 1 (1.98%) | 275 | 8(2.90%)d | −0.41% | 0.51% |

| Poulton et al, 2018 [53] | 25235 | 1676 (6.64%) | 175 | 20(11.43%) | 4873 | 353(7.24%) b | 4.79% | 0.60% | |

| Small for gestational age | Bro et al, 2015 [46] | 989471 | 65499(6.62%) | 186 | 4(2.15%) | 275 | 18(6.55%)d | −4.47% | −0.07% |

| Cohen et al, 2017 [47] | 1451493 | 42526(2.92%) | 4846 | 178(3.67%) | 453 | 20(4.42%)a | 0.75% | 1.46% | |

| Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 21789(2.28%) | 1591 | 43(2.70%) | 9475 | 222(2.34%)e | 0.42% | 0.06% | |

| Large for gestational age | Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 39273(4.11%) | 1591 | 78(4.90%) | 9475 | 422(4.50%) e | 0.79% | 0.39% |

| High birth weight | Poulton et al, 2018 [53] | 25235 | 2539(10.06%) | 175 | 20(11.43%) | 4873 | 481(9.87%)b | 1.37% | −0.19% |

| Low Apgar scores | Bro et al, 2015 [46] | 989471 | 50184(5.07%) | 186 | 8(4.30%) | 275 | 8(2.91%)d | −0.77% | −2.16% |

| Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 12592(1.32%) | 1591 | 38(2.38%) | 9475 | 177(1.86%)e | 1.06% | 0.54% | |

| Poulton et al, 2018 [53] | 25179 | 640(2.54%) | 174 | 5(2.87%) | 4767 | 133(2.79%) b | 0.33% | 0.25% | |

| Stillbirth/perinatal death | Haervig et al, 2014 [49] | 1054014 | 3677(0.35%) | 480 | 2(0.42%) | 706 | 1(0.14%)c | 0.07% | −0.21% |

| Bro et al, 2015 [46] | 989471 | 3517(0.36%) | 186 | 0 | 275 | 1(0.04%) d | −0.36% | −0.32% | |

| Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 4268(0.45%) | 1591 | 8(0.50%) | 9475 | 38(0.41%) e | 0.05% | −0.04% | |

| Poulton et al, 2018 [53] | 25233 | 233(0.92%) | 175 | 2(1.14%) | 4870 | 47(0.97%) b | 0.22% | 0.05% | |

| NICU admission | Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 79530(8.34%) | 1591 | 259(16.27%) | 9475 | 1105(11.66%) e | 7.93% | 3.32% |

| Poulton et al, 2018 [53] | 25239 | 4305(17.06%) | 175 | 47(26.9%) | 4879 | 1019(20.89%) b | 9.84% | 3.83% | |

| Congential malformations | |||||||||

| Major malformation | Haervig et al, 2014 [49] | 1054014 | 41238(3.91%) | 480 | 3(0.63%) | - | - | −3.28% | - |

| Pottegard et al, 2014 [52] | 2220 | 86(3.87%) | 222 | 7(3.15%) | - | - | −0.72% | - | |

| Bro et al, 2015 [46] | 989471 | 39557(4.00%) | 186 | 2(1.08%) | 275 | 7(2.55%) d | −2.92% | 1.45% | |

| Diav-Citrin et al, 2016 [48] | 358 | 13(3.6%) | 309 | 10(3.23%) | - | - | −0.41% | - | |

| Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 20736(2.17%) | 1591 | 48(3.02%) | 9475 | 205(2.16%) e | 0.85% | −0.01% | |

| Huybrechts et al, 2018 [50] | 1797938 | 62966(3.50%) | 7643 | 348(4.55%) | - | - | 1.05% | - | |

| Cadiovascular malformation | Pottegard et al, 2014 [52] | 2220 | 32(1.44%) | 222 | 3(1.35%) | - | - | −0.09% | - |

| Diav-Citrin et al, 2016 [48] | 358 | 3 (0.84%) | 247 | 2(0.81%) | - | - | −0.03% | - | |

| Huybrechts et al, 2018 [50] | 1797938 | 22910(1.27%) | 7643 | 125(1.63%) | - | - | 0.36% | - | |

| Other perinatal morbidity among infants | |||||||||

| Respiratory disorders | Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 35479(3.72%) | 1591 | 92(5.78%) | 9475 | 511(5.39%) e | 2.06% | 1.67% |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 42948(4.50%) | 1591 | 91(5.71%) | 9475 | 511(5.39%) e | 1.21% | 0.89% |

| Hypoglycemia | Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 23965(2.51%) | 1591 | 66(4.15%) | 9475 | 326(3.44%) e | 1.64% | 0.93% |

| Feeding difficulties | Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 9837(1.03%) | 1591 | 34(2.14%) | 9475 | 130(1.37%) e | 1.11% | 0.34% |

| CNS-related disorders | Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 2885(0.30%) | 1591 | 16(1.01%) | 9475 | 40(0.42%) e | 0.71% | 0.12% |

| Withdrawal symptoms for therapeutic drugs | Nörby et al, 2017 [51] | 953668 | 124(0.01%) | 1591 | 7(0.44%) | 9475 | 10(0.11%) e | 0.43% | 0.10% |

ADHD: Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

NICU: Neonatal intensive care unit

Alternative comparison groups including:

Women exposed to Atomoxetine (a non-stimulant ADHD medication) during pregnancy;

Women who used ADHD medication before or after pregnancy;

Women with discordant exposure to ADHD medication across pregnancies;

Women diagnosed with ADHD who did not take ADHD medications;

Women who used ADHD medication before or after pregnancy only.

The studies varied in quality, with NOS ratings ranging from five to nine. As shown in Table S3, all studies used well-defined exposures and outcomes, with reasonable and strict selection criteria. However, most included studies with one or no star in “Comparability” did not consider maternal ADHD and unmeasured factors (e.g. genetic factors) as potential confounders [48–53].

Regarding the relative risk (i.e. the ratio between the risk of an adverse outcome in exposed and unexposed group), conflicting evidence was found for the association between maternal ADHD medication use during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy and offspring outcomes. Some studies suggested a small increased risk of low Apgar scores [46], preeclampsia [47], preterm birth [47], miscarriage [48, 49], cardiac malformations [50], admission to a NICU [51, 53], and central nervous system (CNS)-related disorder [51], but other available studies [46, 48, 51–53] failed to detect similar associations.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall summary

Large studies from several countries have explored several important pregnancy-related outcomes. There is no conclusive evidence to support that ADHD medication use in pregnancy increases the risk of pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes. For example, the pooled estimates from a recent meta-analysis [40] of these studies only demonstrated a statistically significant association with NICU (Relative Risk, RR:1.88; 95%CI=1.70–2.08), with only two studies contributing to the pooled estimates. The results of the current study demonstrate that the absolute risk differences were overall small in magnitude, in particular for studies using alternative comparisons groups to rule out confounding. Further, because of the few number of studies and limited control for confounding it is currently unclear whether these small associations are due to a causal effect of prenatal exposure to ADHD medication or confounding. Moreover, no study evaluated associations with long-term offspring outcomes. Given the absence of scientific evidence, the physicians should weigh whether the advantages of using ADHD medication outweigh the potential risks for the developing fetus offspring according to the different unique situation of each pregnant woman or woman at childbearing age.

4.2. Methodological considerations

Several non-causal pathways could account for observed associations between maternal ADHD medication use during pregnancy and pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes. Given that RCTs of ADHD medication use during pregnancy are unfeasible, advancing knowledge regarding potential risks and benefits needs to rely on evidence from observational studies. The findings of the current systematic review highlight two methodological considerations that need to be addressed in future observational studies.

First, although all individual studies included in this systematic review accounted for confounding by adjusting for measured characteristics in the regression models, the included confounding factors varied substantially across studies, and few studies provided a clear rationale for their covariate selection. In addition, inadequate adjustment for confounding was found in most studies, and none of the included studies adjusted for ADHD severity, which is known to be related to co-occuring conditions and widely varying courses of treatment [56]. Because of these limitations, it is currently unclear if any of the observed associations reflect a causal effect or confounding. Clearly, more research is needed, and these studies should use well-designed measured confounding selection strategies to identify all relevant confounding, which would be consistent with recent methodological recommendations for observational studies [57].

Second, only five of eight included studies used methods that target unmeasured confounding factors [46, 47, 49, 51, 53]. Sibling comparisons is a widely used family-based quasi-experimental design, especially in studies of associations between prenatal exposures and later health outcomes [58, 59]. Siblings share approximately 50% of their segregating genes and often have similar early-life environments. A contrast of siblings discordant for prenatal ADHD medication use automatically accounts for all genetic and environmental factors shared by siblings [60]. One sibling-comparison study [49] has examined the associations between ADHD medication use during pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage, suggesting that confounding by familial factors could account for the associations observed in the studied population. However, because only a small portion (n=706) of all observed pregnancies (n=1 054 494) contributed with the main information to these analyses (i.e. siblings discordant for both maternal ADHD medication exposure and studied outcomes are most informative in the sibling comparisons), the findings should be interpreted with caution. In addition to the substantial reduction in sample size and statistical power and high attenuation of associations due to random measurement error, sibling comparisons do not by design account for factors that vary across pregnancies, which must be considered, as their confounding influence will be inflated when comparison is restricted to exposure discordant siblings. Sibling-comparison studies also assume no carryover effects [61] from the exposed siblings (ADHD medication use during pregnancy) to unexposed siblings (without ADHD medication during other pregnancies). More sibling comparison studies from different countries, with larger samples, focusing on other perinatal and long-term outcomes, are still needed to replicate and extend the available evidence.

The timing of exposure design compares offspring outcomes following maternal ADHD medication use before or after pregnancy with offspring outcomes following maternal ADHD medication use during pregnancy. This design accounts for confounding factors shared by women who are prescribed ADHD medication around the time of pregnancy. Observing similar risk of outcomes across different exposure time-periods before, during, and after the pregnancy is inconsistent with a causal hypothesis, as treatment before or after pregnancy but not during pregnancy is unlikely to have a specific intrauterine influence [62]. Nörby et al. [51] reported somewhat increased risks for NICU admissions, central nervous system-related disorders, and preterm birth in offspring exposed to maternal ADHD medication during pregnancy compared with both non-exposed infants and those born to mothers who took ADHD medication before or after pregnancy. However, Poulton et al. [53] found that treatment for ADHD at any time (before, before and during, or only after the index pregnancy) was similarly associated with a somewhat increased risk of caesarean delivery, neonatal resuscitation and NICU admission. The study by Poulton et al [53] did not directly compare use during pregnancy to use before or after pregnancy, meaning that the study had a limited ability to assess whether ADHD medication use during pregnancy had an effect over and above indications for ADHD treatment around the time of pregnancy. The main limitations of the timing of exposure design are that preconception exposure is assumed to have no intrauterine influence, and some important confounding factors (e.g. severity of the underlying condition) are not automatically adjusted for by the design. More studies are needed to examine associations with exposure during specific trimesters rather than using a broad measure covering exposure during any time-point across the pregnancy period.

Restricting the analyses to the target patient group with or without treatment is often used as a strategy to evaluate associations between treatments and outcomes; the approach targets confounding by indication by directly accounting for the underlying condition. Bro et al. [46] examined the rate of adverse pregnancy outcomes after exposure to ADHD medication during pregnancy compared to unmedicated women diagnosed with ADHD. This study found a small increased risk of spontaneous abortion in both treated and untreated women, while an increased risk of low Apgar score was only found in those exposed to ADHD medication during pregnancy. It is important to note that the study by Bro et al. [46] did not directly compare exposed pregnancies to those with ADHD diagnosis but without prescribed ADHD medications, indicating that the study had a limited ability to disentangle the effects of the medication from the effects of the underlying disease. A major limitation of this design is that treated and non-treated individuals typically differ on measures of severity and in their comorbidity profiles, meaning that confounding by indication remains a serious threat to validity in the design.

The active comparator design compares the effect of the target medication with another active drug used in clinical practice for the same underlying condition. The purpose of the design is to mitigate confounding by indication and other unmeasured patient characteristics (e.g., healthy initiator, frailty). One study [47] evaluated the safety of psychostimulant (amphetamine, dextroamphetamine) use during pregnancy by using atomoxetine, a non-stimulant ADHD medication, as an active comparator. The study found that psychostimulant use during pregnancy was associated with a small increased risk of preeclampsia and preterm birth compared to atomoxetine use during pregnancy. This finding suggests that previously observed associations between maternal psychostimulant use during pregnancy and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes were not solely due to confounding by factors associated with taking either medication. The main limitation of the design is that the interpretation of results rested on the assumption that there are no unmeasured factors that differentiate the different study drug initiators. For future studies, it is important to note that the baseline characteristics of the two treatment groups should be balanced, by using the same approaches to covariate selection, or choosing an appropriate active comparator group that receives a drug with the same or a similar indication makes the treatment groups similar in terms of treatment indications [63].

No previous study has used paternal ADHD medication use as a negative control to explore the role of unmeasured confounding. The negative control design examines the impact of unmeasured confounding by comparing the associations with outcomes separately for maternal ADHD medication using during pregnancy and paternal ADHD medication use during the same pregnancy period. It is based on the assumptions that there is no direct association between the father’s exposure during the pregnancy period and the child’s outcome and that the shared confounders are equally associated with the mother and the father’s exposures [64]. Any observed association between paternal medication use and offspring outcomes could be taken to suggest that an observed association between maternal medication use and offspring outcome is influenced by confounding to some extent. Several paternal comparison studies [65–67] have examined the associations between paternal antidepressant use during the pregnancy period and risk of ASD or ADHD in offspring. Most of these studies, including a meta-analysis [67], have reported positive associations, which indicates that the observed associations between maternal antidepressant use during pregnancy and risk of Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or ADHD in offspring are at least in part due to familial confounding.

Obviously, because the above-mentioned study designs are reliant upon varying assumptions, each has the potential to address differing sources of confounding to differing extents. Given that none of them is likely to completely eliminate bias from confounding, future efforts should attempt to triangulate research findings based on a combination of different designs that differ in their underlying assumptions and limitations [68].

4.3. Current knowledge gaps

There are a number of significant research questions related to the risks and benefits of maternal ADHD medication use during pregnancy that need to be addressed in future research. First, rodent studies suggested dose-dependent associations between fetal exposure to common ADHD medications and adverse outcomes of offspring. Future human studies should also explore whether the associations observed in human depend on dose. Second, the available studies used administrative data or register-based data from Europe and US. Similar data is also available in Asian countries [e.g. 69, 70], and these data should be used in future research to test for generalizability of findings regarding the safety of ADHD medication use during pregnancy. Third, several studies have used methods that help account for unmeasured confounding in combination with measured covariates to study ADHD medication use during pregnancy and pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes, but whether observed associations in these studies are causal remains unclear, which requires studies that more rigorously account for confounding. Fourth, future research is needed to further elucidate the long-term impact of ADHD medication use during pregnancy on offspring, including neurodevelopmental delays and children’s long-term psychosocial health. The fetal origins hypothesis [71] proposes that the period of gestation has significant impacts on the developmental health and wellbeing outcomes for an individual ranging from infancy to adulthood, but there are no studies of the long-term associations with ADHD medication exposure during pregnancy. Fifth, more studies need to assess if there are particularly sensitive periods during pregnancy. Currently, most studies have used measures of ADHD medication exposures that do not tap in to specific periods during pregnancy, which potentially is problematic given that some research indicates that exposure during early pregnancy (first trimester or first 90 days of pregnancy) may be more harmful due to the immaturity of the blood-brain barrier [72]. Exposure during the second and third trimester may also be important to consider given that these are sensitive periods for fetal growth and brain development [73]. Clearly, more studies evaluating the implications of ADHD medication use during specific pregnancy periods are still needed.

4.4. Clinical Implications

The current systematic review extends the findings from previous studies by documenting relatively small absolute risks associated with ADHD medication during pregnancy for pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes, along with considerable heterogeneity in the quality (e.g., adjustment for confounding) of the extant literature. Women with ADHD appear to be at a slightly higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes regardless of current medication status, highlighting a need for increased obstetric surveillance in this group. There is no solid evidence that ceasing medication during pregnancy reduces the risk of adverse outcomes. More research is needed to provide clear recommendations for updated guidelines regarding the use of ADHD medication in pregnancy. The decision of whether to continue medication in pregnancy should be made on a case-by-case basis, weighing the need of medication for daily life functioning against the slightly increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcome.

4.5. Conclusions

This systematic review suggests that there is no convincing evidence to indicate that prenatal exposure to ADHD medication results in clinically-significant adverse effects. However, more research is needed before solid clinical recommendations can be made. In particular, research needs to seek converging evidence from studies using a variety of samples and designs that with different strengths and limitations. Moreover, future research needs to assess the potential impact of timing of exposure and potential long-term outcomes in the offspring.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications are used by increasing numbers of reproductive-age women, but the safety of these medications during pregnancy remains unclear.

At present, the limited number of existing studies indicate that the absolute risks of pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes associated with ADHD medication use during pregnancy are low. The studies, particularly the most methodologically rigorous studies, also suggests that there is no clear evidence to indicate that prenatal exposure to ADHD medication results in clinically-significant adverse effects.

More studies, with various study designs to adjust for confounding, evaluating the consequences of ADHD medication use during different specific pregnancy periods, as well as longer-term outcomes in the offspring, are still needed.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Swedish Research Council (No.2018-02599 to Larsson and No.2018-02679 to D’Onofrio), the Swedish Brain Foundation (Viktorin and No. FO2018-0273 to Larsson) and the National Institute On Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R00DA040727 (Quinn), and R01DA048042 (D’Onofrio, Quinn, Oberg). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest H.L. has served as a speaker for Evolan Pharma and Shire and has received research grants from Shire; all outside the submitted work. S.C. declares honoraria and reimbursement for travel and accommodation expenses for lectures from the following non-profit associations: Association for Child and Adolescent Central Health (ACAMH), Canadian ADHD Alliance Resource (CADDRA), British Association of Pharmacology (BAP), and from Healthcare Convention for educational activity on ADHD. B.D. declares reimbursement for travel and accommodation expenses for CADDRA and Children and Adults with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Faraone SV, Biederman J, and Mick E, The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychological medicine, 2006. 36(2): p. 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caye A, et al. , Life span studies of ADHD—conceptual challenges and predictors of persistence and outcome. Current psychiatry reports, 2016. 18(12): p. 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robison RJ, et al. , Gender differences in 2 clinical trials of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a retrospective data analysis. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 2008. 69(2): p. 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quinn PO, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and its comorbidities in women and girls: an evolving picture. Current Psychiatry Reports, 2008. 10(5): p. 419–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortese S, et al. , Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2018. 5(9): p. 727–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortese S, et al. , Practitioner review: current best practice in the management of adverse events during treatment with ADHD medications in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 2013. 54(3): p. 227–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. 2018; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87.

- 8.Faraone SV, et al. , Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2015. 1(1): p. 15020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franke B, et al. , Live fast, die young? A review on the developmental trajectories of ADHD across the lifespan. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 2018. 28(10): p. 1059–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Instanes JT, et al. , Adult ADHD and comorbid somatic disease: a systematic literature review. Journal of Attention Disorders, 2018. 22(3): p. 203–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Q, et al. , Common psychiatric and metabolic comorbidity of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A population-based cross-sectional study. PloS one, 2018. 13(9): p. e0204516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adamou M, et al. , Occupational issues of adults with ADHD. BMC Psychiatry, 2013. 13(1): p. 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du Rietz E, et al. , Predictive validity of parent- and self-rated ADHD symptoms in adolescence on adverse socioeconomic and health outcomes. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2017. 26(7): p. 857–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raman SR, et al. , Trends in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medication use: a retrospective observational study using population-based databases. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2018. 5(10): p. 824–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy S, et al. , The epidemiology of pharmacologically treated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children, adolescents and adults in UK primary care. BMC pediatrics, 2012. 12(1): p. 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castle L, et al. , Trends in medication treatment for ADHD. Journal of attention disorders, 2007. 10(4): p. 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zetterqvist J, et al. , Stimulant and non‐stimulant attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder drug use: total population study of trends and discontinuation patterns 2006–2009. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 2013. 128(1): p. 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulenberg J, et al. , Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2018: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19–60. 2019.

- 19.dos Santos JF, et al. , Maternal, fetal and neonatal consequences associated with the use of crack cocaine during the gestational period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics, 2018. 298(3): p. 487–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank DA, et al. , Growth, development, and behavior in early childhood following prenatal cocaine exposure: a systematic review. Jama, 2001. 285(12): p. 1613–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chavkin W, Cocaine and pregnancy—time to look at the evidence. Jama, 2001. 285(12): p. 1626–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Betancourt LM, et al. , Adolescents with and without gestational cocaine exposure: longitudinal analysis of inhibitory control, memory and receptive language. Neurotoxicology and teratology, 2011. 33(1): p. 36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Messinger DS, et al. , The maternal lifestyle study: cognitive, motor, and behavioral outcomes of cocaine-exposed and opiate-exposed infants through three years of age. Pediatrics, 2004. 113(6): p. 1677–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurt H, et al. , School performance of children with gestational cocaine exposure. Neurotoxicology and teratology, 2005. 27(2): p. 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bada HS, et al. , Preadolescent behavior problems after prenatal cocaine exposure: relationship between teacher and caretaker ratings (Maternal Lifestyle Study). Neurotoxicology and teratology, 2011. 33(1): p. 78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lester BM, LaGasse LL, and Seifer R, Cocaine exposure and children: the meaning of subtle effects. 1998, American Association for the Advancement of Science. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peters HT, et al. , The pharmacokinetic profile of methylphenidate use in pregnancy: A study in mice. Neurotoxicol Teratol, 2016. 54: p. 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McFadyen-Leussis MP, et al. , Prenatal exposure to methylphenidate hydrochloride decreases anxiety and increases exploration in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 2004. 77(3): p. 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lloyd SA, et al. , Prenatal exposure to psychostimulants increases impulsivity, compulsivity, and motivation for rewards in adult mice. Physiol Behav, 2013. 119: p. 43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teo SK, et al. , The perinatal and postnatal toxicity of D-methylphenidate and D,L-methylphenidate in rats. Reprod Toxicol, 2002. 16(4): p. 353–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teo SK, et al. , D-methylphenidate and D,L-methylphenidate are not developmental toxicants in rats and rabbits. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol, 2003. 68(2): p. 162–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beckman DA, et al. , Developmental toxicity assessment of d, l-methylphenidate and d-methylphenidate in rats and rabbits. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol, 2008. 83(5): p. 489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lepelletier FX, et al. , Prenatal exposure to methylphenidate affects the dopamine system and the reactivity to natural reward in adulthood in rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol, 2014. 18(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah NS and Yates JD, Placental transfer and tissue distribution of dextro-amphetamine in the mouse. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther, 1978. 233(2): p. 200–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nora JJ, Trasler DG, and Fraser FC, Malformations in mice induced by dexamphetamine sulphate. Lancet, 1965. 2(7420): p. 1021–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasirsky G, Teratogenic effects of methamphetamine in mice and rabbits. J Am Osteopath Assoc, 1971. 70(10): p. 1119–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto Y, et al. , Effects of amphetamine on rat embryos developing in vitro. Reprod Toxicol, 1998. 12(2): p. 133–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sauer JM, Ring BJ, and Witcher JW, Clinical pharmacokinetics of atomoxetine. Clin Pharmacokinet, 2005. 44(6): p. 571–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lilly Eli, Company. Strattera (atomoxetine) package insert. Indianapolis, IN, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang H.y., et al. , Maternal and neonatal outcomes after exposure to ADHD medication during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety, 2019. 28(3): p. 288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Von Elm E, et al. , The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Annals of internal medicine, 2007. 147(8): p. 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McAllister-Williams RH, et al. , British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum 2017. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 2017. 31(5): p. 519–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liberati A, et al. , The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLOS Medicine, 2009. 6(7): p. e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Z, et al. , Advances in Epidemiological Methods and Utilisation of Large Databases: A Methodological Review of Observational Studies on Central Nervous System Drug Use in Pregnancy and Central Nervous System Outcomes in Children. Drug Saf, 2019. 42(4): p. 499–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wells G, et al. , The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses.

- 46.Bro SP, et al. , Adverse pregnancy outcomes after exposure to methylphenidate or atomoxetine during pregnancy. Clinical Epidemiology, 2015. 7: p. 139–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen JM, et al. , Placental complications associated with psychostimulant use in pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2017. 130(6): p. 1192–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diav-Citrin O, et al. , Methylphenidate in pregnancy: A multicenter, prospective, comparative, observational study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 2016. 77(9): p. 1176–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hærvig KB, et al. , Use of ADHD medication during pregnancy from 1999 to 2010: A Danish register-based study. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 2014. 23(5): p. 526–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huybrechts KF, et al. , Association between methylphenidate and amphetamine use in pregnancy and risk of congenital malformations: A cohort study from the international pregnancy safety study consortium. JAMA Psychiatry, 2018. 75(2): p. 167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nörby U, Winbladh B, and Källén K, Perinatal outcomes after treatment with ADHD medication during pregnancy. Pediatrics, 2017. 140(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pottegard A, et al. , First-trimester exposure to methylphenidate: A population-based cohort study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 2014. 75(1): p. e88–e93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poulton AS, Armstrong B, and Nanan RK, Perinatal Outcomes of Women Diagnosed with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: An Australian Population-Based Cohort Study. CNS Drugs, 2018. 32(4): p. 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clapp MA, et al. , Unexpected term NICU admissions: a marker of obstetrical care quality? American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2019. 220(4): p. 395.e1–395.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Al-Wassia H and Saber M, Admission of term infants to the neonatal intensive care unit in a Saudi tertiary teaching hospital: cumulative incidence and risk factors. Annals of Saudi medicine, 2017. 37(6): p. 420–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nigg JT, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and adverse health outcomes. Clinical psychology review, 2013. 33(2): p. 215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.VanderWeele TJ, Principles of confounder selection. European journal of epidemiology, 2019. 34(3): p. 211–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.D’onofrio BM, et al. , Critical need for family-based, quasi-experimental designs in integrating genetic and social science research. American journal of public health, 2013. 103(S1): p. S46–S55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lahey BB and D’Onofrio BM, All in the family: Comparing siblings to test causal hypotheses regarding environmental influences on behavior. Current directions in psychological science, 2010. 19(5): p. 319–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sujan AC, et al. , Annual Research Review: Maternal antidepressant use during pregnancy and offspring neurodevelopmental problems–a critical review and recommendations for future research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 2019. 60(4): p. 356–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sjölander A, et al. , Carryover effects in sibling comparison designs. Epidemiology, 2016. 27(6): p. 852–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith GD, Assessing intrauterine influences on offspring health outcomes: can epidemiological studies yield robust findings? Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology, 2008. 102(2): p. 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoshida K, Solomon DH, and Kim SC, Active-comparator design and new-user design in observational studies. Nature reviews. Rheumatology, 2015. 11(7): p. 437–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lipsitch M, Tchetgen ET, and Cohen T, Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 2010. 21(3): p. 383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sørensen MJ, et al. , Antidepressant exposure in pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorders. Clinical epidemiology, 2013. 5: p. 449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sujan AC, et al. , Associations of maternal antidepressant use during the first trimester of pregnancy with preterm birth, small for gestational age, autism spectrum disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring. Jama, 2017. 317(15): p. 1553–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morales DR, et al. , Antidepressant use during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: systematic review of observational studies and methodological considerations. BMC medicine, 2018. 16(1): p. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lawlor DA, Tilling K, and Davey Smith G, Triangulation in aetiological epidemiology. International journal of epidemiology, 2016. 45(6): p. 1866–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chang WS, et al. , Maternal pregnancy-induced hypertension increases the subsequent risk of transient tachypnea of the newborn: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol, 2018. 57(4): p. 546–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Man KKC, et al. , Prenatal antidepressant use and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: population based cohort study. Bmj, 2017. 357: p. j2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barker DJ, Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. Bmj, 1995. 311(6998): p. 171–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thorpe PG, et al. , Medications in the first trimester of pregnancy: most common exposures and critical gaps in understanding fetal risk. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety, 2013. 22(9): p. 1013–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ross EJ, et al. , Developmental consequences of fetal exposure to drugs: what we know and what we still must learn. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 2015. 40(1): p. 61–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.