Abstract

Background:

Breast conserving surgery (BCS) and mastectomy have equivalent survival for DCIS allowing patients to participate in selecting a personalized surgical option. However this decision making role can increase patient anxiety. Data are limited evaluating patient satisfaction with their decision to undergo BCS vs mastectomy for the treatment of DCIS.

Methods:

Women with DCIS were enrolled in a population-based state-wide cohort from 1997-2006. Participants were surveyed about their satisfaction with their surgical and reconstruction decisions. Quality of life (QoL) evaluations were performed with biennial follow-up surveys though 2016. Multivariable logistic regression modelling examined the relationship between type of surgery and reconstruction with patient satisfaction.

Results:

1,537 women were surveyed on average 2.9 years following DCIS diagnosis. Over 90% reported satisfaction with their treatment decision regardless of surgery type. Women who underwent mastectomy with reconstruction were more likely to report lower levels of satisfaction than women who underwent BCS (OR 2.98, CI 1.18-7.51, p<0.01). However, over 80% of women who underwent mastectomies reported satisfaction with their reconstruction decision. Women without reconstruction had the highest levels of satisfaction while women with implants were more likely to be dissatisfied (Implant + Autologous OR 2.77, CI 1.24-6.24; Implant alone OR 4.02, CI 1.947-8.34, p≤0.01). QoL scores were not associated with differences in surgical or reconstruction satisfaction at 5, 10, and 15 years following DCIS diagnosis.

Conclusions:

Women undergoing surgery for DCIS express satisfaction with their treatment decisions. Following mastectomy most women are satisfied with their reconstruction decision, including women who did not undergo reconstruction.

Introduction

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a noninvasive form of breast cancer accounting for approximately 20% of breast malignancies in the US.1 Current guidelines recommend surgical excision with the option of adjuvant radiation following breast conserving surgery (BCS) and hormonal therapy for appropriate patients.2,3 While there are no randomized controlled trials directly comparing BCS to mastectomy in patients with DCIS, the findings of equivalent survival outcomes for either surgical choice in invasive cancer have been extrapolated to DCIS. Unlike many other cancer diagnoses, most patients with DCIS participate in a shared decision making process with their surgeon regarding which type of surgery they would prefer without concerns for long-term survival differences. These decisions are based on the woman’s personal preferences of ongoing oncologic risk/screening, the need for further radiation/hormonal treatment, and physical appearance.

Because women actively participate in selecting their surgical options for DCIS, understanding how these decisions impact long term patient satisfaction and quality of life (QoL) can aid clinicians in counselling patients. Surgical satisfaction and long-term patient QoL evaluations have been described in patients with invasive breast cancer, but are limited in patients with DCIS. Fosh described high levels of satisfaction with cosmetic outcome in a cohort of 55 women who underwent BCS for their DCIS.4 Sackey examined QoL scores in 162 women treated for DCIS in Sweden, 115 of whom underwent BCS; finding that BCS patients reported higher QoL scores than those who had mastectomies with reconstruction.5 A prior study looking at QoL results in over 1600 women in the Wisconsin in situ Cohort (WISC), found that age at DCIS diagnosis influences satisfaction and quality of life, with younger patients reporting lower QoL scores, especially during the first years following diagnosis.6 However, none of these studies specifically examined DCIS patients’ overall satisfaction with their surgical and reconstruction decisions. Additionally, in the studies that evaluate surgery type, QoL scores were only evaluated at a single time point following surgery ranging from 2-15 years after treatment completion.

Utilizing WISC data, we sought to determine whether women treated for DCIS were satisfied with their surgical decisions including the type of surgery as well as their decision regarding reconstruction and how that satisfaction impacted QoL scores over 15 years following their diagnosis. We hypothesized that satisfaction would be highest in women who underwent BCS or mastectomy with reconstruction and lowest in women who underwent mastectomy without reconstruction.

Methods

Study Population

WISC has been previously described.7 Briefly, adult women with an initial non-invasive breast cancer diagnosis as reported to the Wisconsin Cancer Reporting System from 1997-2006 were eligible for enrollment. The women who were residents of Wisconsin at the time of diagnosis were approached via telephone interview. Exclusion criteria included: unknown diagnosis date, no publicly available phone number, or inability to participate in a phone interview. 78% of eligible patients enrolled in the study.7 The study was approved by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board and participants provided informed consent.

Participants completed an interview at the time of enrollment. Biennial follow-up interviews began in 2003 and are on-going. Enrollees are eligible for re-contact once at least two years have passed since the prior survey. Due to the overlapping nature of enrollment and follow-up periods not all women were contacted for each follow-up cycle. The participation rates for the five follow-up surveys were 79%, 85%, 73%, 73%, and 79% of eligible subjects for each survey respectively. This study includes data from enrollment through up to five follow-ups (through 2016) for each participant.

Surgical Satisfaction Assessment

Questions about patient satisfaction with their decision about surgery and reconstruction were included in enrollment and follow-up surveys administered from 2002-2006. Using a 5 point Likert scale ranging from very satisfied (1) to very dissatisfied (5), participants were asked “How satisfied are you now with the decision about the type of breast surgery?” after reporting their type of breast cancer surgery. Women who underwent a mastectomy were asked “How satisfied are you now with the decision (regarding reconstruction)?” using the same 5 point Likert scale Participants who answered at least one set of satisfaction questions were included in this study (N=1,624). A subset of women answered the satisfaction questions twice (N=430); for these women, only their first response was included in this analysis. Women who experienced recurrence prior to answering the satisfaction questions (N=81) or who did not know their type of surgery (N=6) were excluded from analysis.

Quality of Life Assessment

Quality of Life (QoL) was assessed by the validated SF-36 at the time of enrollment and in every follow-up survey.8 Assessments at five, ten, and fifteen years following diagnosis were included in this study. Survey responses collected between 4-6, 9-11, and 14-16 years following diagnosis were included in the five, ten, and fifteen year groups respectively. Participants answered 36 questions about their physical and mental health. A standard scoring procedure converted the responses into summary scores in eight domains which were summarized into mental component summary (MCS) and physical component summary (PCS) scores. Higher scores represent better QoL. Analysis of SF-36 data used the following standard approach8: scores were normalized to a standard population representative of the US population, and standardized scores were transformed to a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 to allow valid comparisons between scales and US population norms.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were assessed by the Chi-squared method. Multivariable logistical regression modeling examined the relationship between satisfaction with surgery or reconstruction decision and type of surgery. Models were constructed to predict the likelihood of patients being very satisfied (Likert score of 1, referent) vs somewhat satisfied (Likert score of 2) or the combined group of women who were neutral, somewhat dissatisfied or very dissatisfied (Likert scores of 3, 4, and 5 respectively) with their surgery decision. We grouped the women who reported feeling neutral or dissatisfied with their surgeries because lack of satisfaction was considered suboptimal patient treatment. Only women who underwent mastectomy were included in the models evaluating satisfaction with reconstruction decision and reconstruction type. Additional covariates included in models were age at diagnosis, household income, education, and receipt of adjuvant radiation or endocrine therapy. Due to the large range in time between diagnosis and completing the satisfaction survey, time between diagnosis and satisfaction survey administration was included to control for satisfaction differences due to proximity to treatment.9 Income, education level, surgery type, and reconstruction type were considered static from baseline assessments. Missing covariates were imputed using the “mi impute chained” command in Stata software to impute missing values using fully conditional specification10. The variables with missing/imputed values were: surgery type 178, race 22, education 5, income 366, endocrine treatment 31. Satisfaction data were used from the first survey administration to each woman since only 15% of women were asked surgery satisfaction questions more than once and results were not substantively different using a repeated measures approach (data not shown).

QoL assessments at five, ten and fifteen years following DCIS diagnosis were examined. A total of 914 women who had previously answered satisfaction questions completed surveys at five, 731 at ten, and 325 at fifteen years following their diagnosis. The QoL PCS and MCS scores were determined for each woman at these time points. Scores were adjusted for age, time from diagnosis to survey, Charleson Index, and education. Participants were stratified by surgical satisfaction: very satisfied, somewhat satisfied or neutral to dissatisfied. Women who underwent mastectomy were separately stratified by their satisfaction with their reconstruction decision. Least square means and standard errors (SE) were calculated using analysis of variance models.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Results

1,537 patients met our inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Median age was 55 (range 27 to 74), the majority (66%) underwent BCS, and 96% of our study cohort was white (Table 1). Due to the lack of racial diversity race was not included in statistical models. On average, patients answered satisfaction questions 2.8 years following their diagnosis.

Figure 1: Wisconsin In Situ Cohort (WISC) enrollment, satisfaction question administration, and quality of life evaluation, 1997-2016.

Diagram of WISC enrollment and administration of satisfaction questions (A). Diagram of participants included in quality of life evaluations (B) – women who completed satisfaction surveys and had quality of life assessments at 5, 10, and 15 years.

Table 1:

General characteristics of women with ductal carcinoma in situ and their satisfaction with breast surgery, WISC study, 1996-2006 (N=1,537)

| Characteristics | N (%) | Satisfaction with type of breast surgerya Mean Score (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| ≤50 | 426 (27.7) | 1.27 (0.70) |

| 51-60 | 566 (36.8) | 1.24 (0.70) |

| 61-70 | 410 (26.7) | 1.18 (0.59) |

| >70 | 135 (8.8) | 1.30 (0.76) |

| Surgical treatment | ||

| Breast conserving surgery | 1019 (66.3) | 1.18 (0.59) |

| Mastectomy (all)b | 518 (33.7) | 1.35 (0.83) |

| No reconstruction | 250 (16.3) | 1.30 (0.77) |

| Implant | 71 (4.6) | 1.44 (0.98) |

| Autologous reconstruction | 142 (9.2) | 1.35 (0.80) |

| Implant and autologous reconstruction | 54 (3.5) | 1.46 (0.92) |

| Time from diagnosis to satisfaction surveyc | ||

| <2 years | 994 (64.7) | 1.24 (0.65) |

| ≥2 years | 543 (35.3) | 1.24 (0.74) |

| Race | ||

| White | 1479 (96.2) | 1.23 (0.67) |

| Non-white | 58 (3.8) | 1.40 (0.92) |

| Education | ||

| ≤High school degree | 639 (41.6) | 1.23 (0.69) |

| Some college | 421 (27.4) | 1.25 (0.66) |

| ≥College degree | 477 (31.0) | 1.24 (0.69) |

| Income | ||

| ≤$30,000 | 344 (22.4) | 1.24 (0.74) |

| $30,001-50,000 | 433 (28.2) | 1.25 (0.66) |

| $50,001-100,000 | 555 (36.1) | 1.22 (0.64) |

| >$100,000 | 205 (13.3) | 1.27 (0.73) |

| Radiation | ||

| No | 677 (44.1) | 1.30 (0.70) |

| Yesd | 860 (55.9) | 1.19 (0.60) |

| Endocrine therapy | ||

| No | 915 (59.5) | 1.26 (0.70) |

| Yes | 622 (40.5) | 1.20 (0.66) |

Answer options 1=very satisfied, 2=somewhat satisfied, 3=neither satisfied or dissatisfied, 4=somewhat dissatisfied, and 5=very dissatisfied.

69 women underwent bilateral mastectomies

Mean 2.81 years, range 0.35-9.00 years after diagnosis. Missing values for characteristics are imputed.

97% underwent BCS

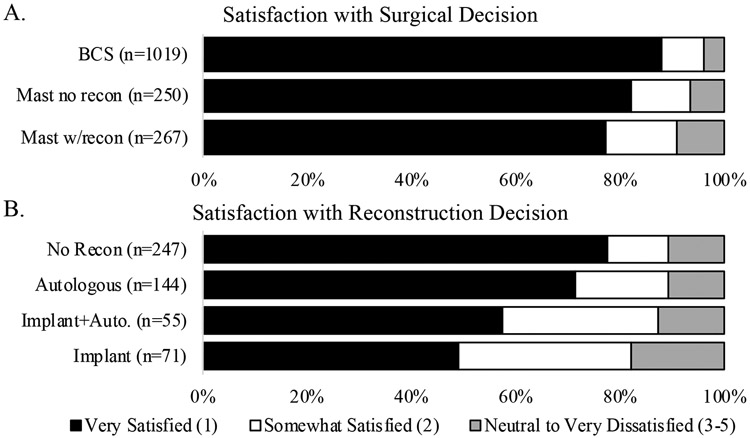

Most patients (95%) reported satisfaction with their surgical decision (Figure 2a). Over 90% of patients reported feeling very or somewhat satisfied regardless of surgery type (96% BCS, 93% mastectomy without reconstruction, 91% mastectomy with reconstruction). In our multivariable analysis surgery type was associated with differences in satisfaction (Table 2). Compared to patients who underwent BCS, patients who underwent mastectomies with reconstruction were less satisfied and more likely to report feeling somewhat satisfied (OR 2.56 CI 1.32-4.97) or neutral/dissatisfied (OR 2.98 CI 1.18-7.51) than very satisfied. Women who underwent mastectomy without reconstruction expressed less satisfaction compared with women who received BCS although confidence intervals around estimates included the null (somewhat satisfied OR 1.98 CI 1.00-3.92 and neutral/dissatisfied OR 2.26 CI 0.89-5.72 vs very satisfied).

Figure 2: Surgical and reconstruction satisfaction scores stratified by surgery type, WISC, 2002-2006.

Respondent surgical satisfaction scores (A) were stratified by type of surgery they received. p<0.001 between different surgery types. Similarly, reconstruction satisfaction scores (B) in women who underwent mastectomies were stratified by type of reconstruction with p<0.0001 between different reconstruction options.

Table 2:

Association between patient dissatisfaction with DCIS breast surgery and reconstruction surgery following mastectomy, WISC study, 1996-2006*

| Surgical Satisfaction | Reconstruction Satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Somewhat vs Very Satisfied, N=1471 |

Neutral/Dissatisfied vs Very satisfied, N=1400 |

Somewhat vs Very Satisfied, N=456 |

Neutral/Dissatisfied vs Very satisfied, N=423 |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Surgery type | ||||

| BCS | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Mastectomy no reconstruction | 1.98 (1.00, 3.92) | 2.26 (0.89, 5.72) | ||

| Mastectomy w/reconstruction | 2.56 (1.32, 4.97) | 2.98 (1.18, 7.51) | ||

| Reconstruction type | ||||

| None | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Autologous reconstruction | 1.40 (0.71, 2.75) | 1.05 (0.49, 2.24) | ||

| Implant and autologous reconstruction | 2.77 (1.24, 6.24) | 1.55 (0.53, 4.52) | ||

| Implant | 4.02 (1.94, 8.34) | 2.5 (1.087, 5.82) | ||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||

| <50 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 50-60 | 0.80 (0.51, 1.25) | 0.92 (0.52, 1.60) | 1.01 (0.57, 1.80) | 1.23 (0.61, 2.46) |

| 60-70 | 0.92 (0.56, 1.53) | 0.44 (0.21, 0.95) | 0.48 (0.21, 1.07) | 0.72 (0.29, 1.79) |

| >70 | 1.40 (0.71, 2.75) | 1.01 (0.41, 2.46) | 0.57 (0.18, 1.74) | 0.33 (0.07, 1.62) |

| Time since diagnosis | ||||

| <2 years | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| ≥2 years | 0.66 (0.45-0.97) | 0.88 (0.54-1.44) | 0.71 (0.42-1.19) | 1.44 (0.79-2.62) |

Missing values for characteristics are imputed. Odds ratios in model adjusted for household income, education, adjuvant radiation and endocrine treatment.

Patients who underwent mastectomies were queried regarding their satisfaction with their decision to undergo or forego breast reconstruction. Of the patients who underwent mastectomies 88% reported being somewhat or very satisfied with their reconstruction decision (Figure 2b). When stratified by reconstruction type most patients reported being somewhat or very satisfied with their decision: 89% for no reconstruction or autologous reconstruction, 87% for implant and autologous, and 82% for implants alone. Patients with implants and autologous reconstruction were more likely to be somewhat satisfied over very satisfied when compared to women who did not undergo reconstruction (Table 2; OR 2.77 CI 1.24-6.24). Women who had implants alone were more likely to report being either somewhat satisfied (OR 4.02 CI 1.94-8.34) or neutral/dissatisfied (OR 2.50 CI 1.09-5.82) over very satisfied.

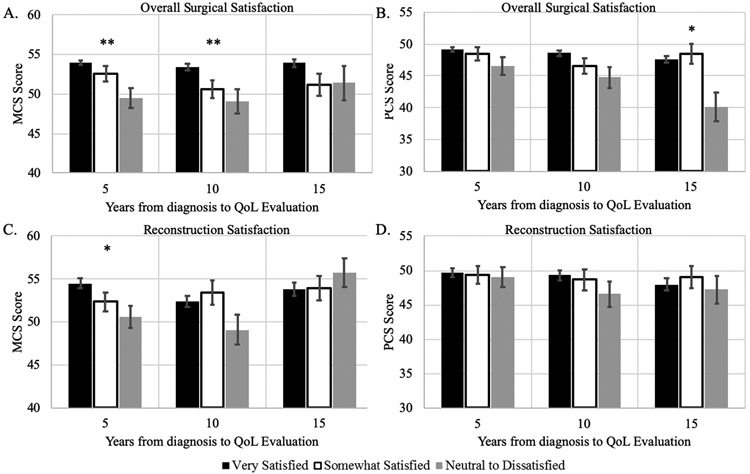

QoL evaluations of women at five, ten and fifteen years following diagnosis were conducted (Figure 3). MCS scores were highest at every time point in women who reported being very satisfied with their surgical decision but the overall score always remained within 5 points across all satisfaction groups (Figure 3a). Similar results were observed in the PCS scores (Figure 3b), although at 15 years women who were neutral to dissatisfied with their surgical decision reported an average PCS score seven to eight points lower than either of the satisfied groups.

Figure 3: Quality of life scores stratified by surgical or reconstruction satisfaction, WISC, 2002-2016.

The least square mean values ± SE among all DCIS cases for (A) mental component summary (MCS) and (B) physical component summary (PCS) were calculated from answers to the SF-36 survey administered at 5 (N=914), 10 (N=731), and 15 years (N=327) following DCIS diagnosis and stratified by patient satisfaction with decision about surgery type. (C) and (D) show similar calculations for reconstruction decision satisfaction scores in women who underwent mastectomies. MCS (C) and PCS (D) scores are shown for N=311 at 5 years, N=221 at 10 years, and N=147 at 15 years. All scores were adjusted for age, time from diagnosis to satisfaction survey, Charleson Index, and education. * p<0.05 and ** p<0.005 between all groups at indicated time point.

QoL scores were obtained from women who had mastectomies and answered the reconstruction satisfaction question at five, ten and fifteen years following diagnosis. At each time point MCS and PCS scores were within five points for each satisfaction group (Figure 3c-d). There was an almost seven point increase in the average MCS score of women who were neutral to dissatisfied with their reconstruction decision between 10 and 15 years after their diagnosis.

Discussion

This is the largest study of surgical satisfaction in DCIS patients. The rate of Wisconsin women who underwent mastectomies without reconstruction (48% of mastectomy patients) seems unusually high today, but is concordant with national rates of reconstruction between 1997 and 2006 when women in this cohort were undergoing treatment.11 Overall, regardless of type of oncologic or reconstructive surgery, women treated for DCIS are quite satisfied with their surgical decisions. This is consistent with studies in invasive breast cancer that identified high levels of satisfaction with surgical decisions.12-14 Women who underwent mastectomies without reconstruction were equally satisfied with their decision as women who underwent reconstruction. Additionally, this work demonstrates that dissatisfaction with surgery or reconstruction is not associated with lower long-term QoL.

Women who underwent mastectomy without reconstruction were more satisfied than women who had reconstruction following mastectomy. This differs from data in invasive cancer where women who undergo mastectomy without reconstruction describe lower satisfaction than those with reconstruction.14,15 A possible contributing factor to this finding is the difference in how DCIS and invasive breast cancers are treated. Women with DCIS who undergo a mastectomy without reconstruction frequently complete their initial treatment with surgery alone, aside from the potential use of endocrine therapy. In contrast, women with invasive cancers often require adjuvant treatment and those undergoing reconstruction have follow-up surgery events. It is possible that women with DCIS who have a mastectomy alone are satisfied that their treatment is completed. This contrasts with invasive breast cancer patients whose reconstruction may signal the end of their breast cancer journey, or a connection to their precancer “normal” life. The importance of these psychosocial factors in determining women’s satisfaction following breast cancer treatment is only beginning to be understood.16

Patients who underwent autologous reconstruction following mastectomy for DCIS were more satisfied than women who had reconstruction with implants, a finding consistent with studies in invasive breast cancer.15 This likely reflects the better durability and long-term aesthetics of autologous reconstruction.9,17-19 Although differences in satisfaction may change over time, Alderman found that between the first and second postoperative years the overall satisfaction of women who underwent implant reconstruction increased more than the satisfaction of women with autologous reconstruction.9 Our data did not indicate a difference in satisfaction when women were asked within two years of diagnosis or after two years (Table 2). Given the high survival rate following DCIS treatment, additional long-term studies in this population are recommended to determine whether patient satisfaction changes over time.

Quality of life at 5, 10, or 15 years was not associated with surgical or reconstruction satisfaction. Prior studies using the SF-36 in patients with chronic health conditions20 or women with differing health profiles (including breast cancer)21 have identified a change in 5-10 points to be the minimum clinically relevant difference. We did not observe any ten point differences and three differences greater than five points: women who were neutral or not satisfied with their surgical decision had lower physical QoL 15 years following their diagnosis than the same group at five years (difference of 6.4) or women who were somewhat or very satisfied at 15 years (difference of 8.4 and 7.5 respectively). These small differences are unlikely to be clinically relevant. This data supports other studies that have found high long term quality of life in women with DCIS or early stage invasive breast cancer.5,22-24

This study has limitations. Surgical and reconstruction satisfaction questions were only asked on surveys administered in 2002-2006, with the majority of participants only answering the questions once thus we are unable to look at how satisfaction changed over time or compare to baseline QoL scores . Satisfaction questions were based on a previous study14 but questions were not validated and predate the validated BREAST-Q25 thus comparison to more recent studies4 may be limited. Of the women who underwent mastectomies, we do not know who was ineligible for BCS due to oncologic characteristics and who chose to have a mastectomy, factors that could impact satisfaction. Information regarding surgery and reconstruction type is selfreported and could not be verified. Women who undergo reconstruction often undergo additional procedures leading to increased risk of complications. We do not have data on complications or additional surgeries which could influence satisfaction and QoL. We do not know when women completed their reconstruction surgeries and could not evaluate whether time from reconstruction to survey impacted satisfaction. The lack of difference over time in QoL scores may represent a confirmation bias where women reaffirm their satisfaction so as to not experience decisional regret. Finally, while this cohort represents DCIS patients from Wisconsin, the lack of racial and ethnic diversity may limit external generalizability of these results.

These results have important implications for clinicians counselling women with DCIS. Patients who elect to forego reconstruction following mastectomy often report resistance from their providers and a lack of shared decision making.26 Our data suggests that clinicians should not be hesitant to discuss mastectomy without reconstruction as a viable treatment option, as women who forgo reconstruction after mastectomy were satisfied with their decision. Overall, clinicians should feel confident counselling patients that no matter what surgery they pursue, they will likely be satisfied and that this decision does not appear to have a large impact on their long term quality of life.

Synopsis:

Women with DCIS are generally satisfied with their surgical and reconstruction decisions. Surgical satisfaction is not related to 15-year long-term quality of life following a DCIS diagnosis.

Acknowledgements:

DLR is supported by NIH Surgical Oncology training grant (T32 CA090217) and the American College of Surgeons Resident Research Scholarship. This study was also supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (P30 CA014520, R01 CA067264, P20 GM103644).

Portions of this study were presented at the Clinical Congress in Boston, MA, in October 2018.

The authors would like to thank Drs. Brian Sprague, Andreas Friedl, Hazel Nichols, and Elizabeth Burnside as well as Julie McGregor, Kathy Peck, Hollis Moore, Oyewale Shiyanbola, and Laura Stephenson for their contributions to study design and data collection.

Footnotes

Disclosures: LGW is a founder and minority stock owner of Elucent Medical.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society Cancer Statistics Center. https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- 2.Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B, et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Invasive Ipsilateral Breast Tumor Recurrences After Lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 Randomized Clinical Trials for DCIS. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(6):478–488. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breast Cancer Clinical Guidelines. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6471.855-b. [DOI]

- 4.Fosh B, Hainsworth A, Beumer J, Howes B, McLeay W, Eaton M. Cosmesis outcomes for sector resection for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(4):1271–1275. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sackey H, Sandelin K, Frisell J, Wickman M, Brandberg Y. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Long-term follow-up of health-related quality of life, emotional reactions and body image. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36(8):756–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart V, Sprague BL, Lakoski SG, et al. Trends in health-related quality of life after a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(12):1323–1329. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.7281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Nichols HB, Hampton JM, Newcomb PA. Change in lifestyle behaviors and medication use after a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124(2):487–495. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0869-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M. SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alderman AK, Kuhn LE, Lowery JC, Wilkins EG. Does Patient Satisfaction with Breast Reconstruction Change over Time? Two-Year Results of the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiyanbola OO, Sprague BL, Hampton JM, et al. Emerging trends in surgical and adjuvant radiation therapies among women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer. 2016;122(18):2810–2818. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waljee JF, Hu ES, Newman LA, Alderman AK. Correlates of patient satisfaction and provider trust after breast-conserving surgery. Cancer. 2008;112(8):1679–1687. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lacovara EJ, Arzouman J, Kim JC, Degan AJ, Horner M. Are Patients With Breast Cancer Satisfied With Their Decision Making? Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. doi: 10.1188/11.CJON.320-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lantz PM, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, et al. Satisfaction with surgery outcomes and the decision process in a population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(3):745–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atisha DM, Rushing CN, Samsa GP, et al. A National Snapshot of Satisfaction with Breast Cancer Procedures. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(2):361–369. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews H, Carroll N, Renshaw D, et al. Predictors of satisfaction and quality of life following post-mastectomy breast reconstruction. Psychooncology. 2017;26(11):1860–1865. doi: 10.1002/pon.4397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alderman AK, Wilkins EG, Lowery JC, Kim M, Davis JA. Determinants of patient satisfaction in postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 106(4):769–776. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200009040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juhl AA, Christensen S, Zachariae R, Damsgaard TE. Unilateral breast reconstruction after mastectomy-patient satisfaction, aesthetic outcome and quality of life. Acta Oncol (Madr). 2017;56(2):225–231. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1266087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jagsi R, Li Y, Morrow M, et al. Patient-reported Quality of Life and Satisfaction With Cosmetic Outcomes After Breast Conservation and Mastectomy With and Without Reconstruction. Ann Surg 2015;261(6):1198–1206. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000000908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wyrwich KW, Tierney WM, Babu AN, Kroenke K, Wolinsky FD. Methods A Comparison of Clinically Important Differences in Health-Related Quality of Life for Patients with Chronic Lung Disease, Asthma, or Heart Disease. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361158/pdf/hesr_00373.pdf. Accessed Lebruary 21, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Yost KJ, Haan MN, Levine RA, Gold EB. Comparing SF-36 scores across three groups of women with different health profiles. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(5):1251–1261. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-6673-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeffe DB, Pérez M, Cole EF, Liu Y, Schootman M. The Effects of Surgery Type and Chemotherapy on Early-Stage Breast Cancer Patients’ Quality of Life Over 2-Year Follow-up. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(3):735–743. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4926-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nekhlyudov L, Kroenke CH, Jung I, Holmes MD, Colditz GA. Prospective changes in quality of life after ductal carcinoma-in-situ: Results from the Nurses’ Health Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2822–2827. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aft RL, Schootman M, Liu Y, Jeffe DB, Collins KK, Pérez M. Quality of life over time in women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ, early-stage invasive breast cancer, and age-matched controls. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(1):379–391. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2048-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):345–353. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bare CF, Wakeley ME, Pine R, et al. Going Flat: The impact of shared decision making on patient satisfaction following breast reconstruction In: American Society of Breast Surgeons Annual Meeting. Dallas, Tx; 2019. [Google Scholar]